Abstract

Autophagy is an essential intracellular process that mediates degradation of intracellular proteins and organelles in lysosomes. Autophagy was initially identified for its role as alternative source of energy when nutrients are scarce but, in recent years, a previously unknown role for this degradative pathway in the cellular response to stress has gained considerable attention. In this review, we focus on the novel findings linking autophagic function with metabolic stress resulting either from proteins or lipids. Proper autophagic activity is required in the cellular defense against proteotoxicity arising in the cytosol and also in the endoplasmic reticulum, where a vast amount of proteins are synthesized and folded. In addition, autophagy contributes to mobilization of intracellular lipid stores and may be central to lipid metabolism in certain cellular conditions. In this review, we focus on the interrelation between autophagy and different types of metabolic stress, specifically the stress resulting from the presence of misbehaving proteins within the cytosol or in the endoplasmic reticulum and the stress following a lipogenic challenge. We also comment on the consequences that chronic exposure to these metabolic stressors could have on autophagic function and on how this effect may underlie the basis of some common metabolic disorders.

Keywords: chaperones, ER stress, lipid metabolism, lysosomes, protein degradation

Introduction to Autophagy and Autophagic Pathways

Autophagy or self-eating is a conserved cellular process that mediates degradation of intracellular components of all types – proteins, organelles, particulate structures and even pathogens – in lysosomes [1]. Distinct autophagic variants coexist in most cells at a given time, although the fraction of intracellular degradation mediated by each of them varies depending on the cell type and on the cellular conditions [2]. Independent of the type of autophagic pathway, there are a series of common functions essential to the autophagic process. The best-characterized functions are the role of autophagy as an alternative source of nutrients [3], the first function identified for this process, the involvement of autophagy in cellular quality control [1] and its contribution to cellular defense as part of both the innate and acquired immunity program [4].

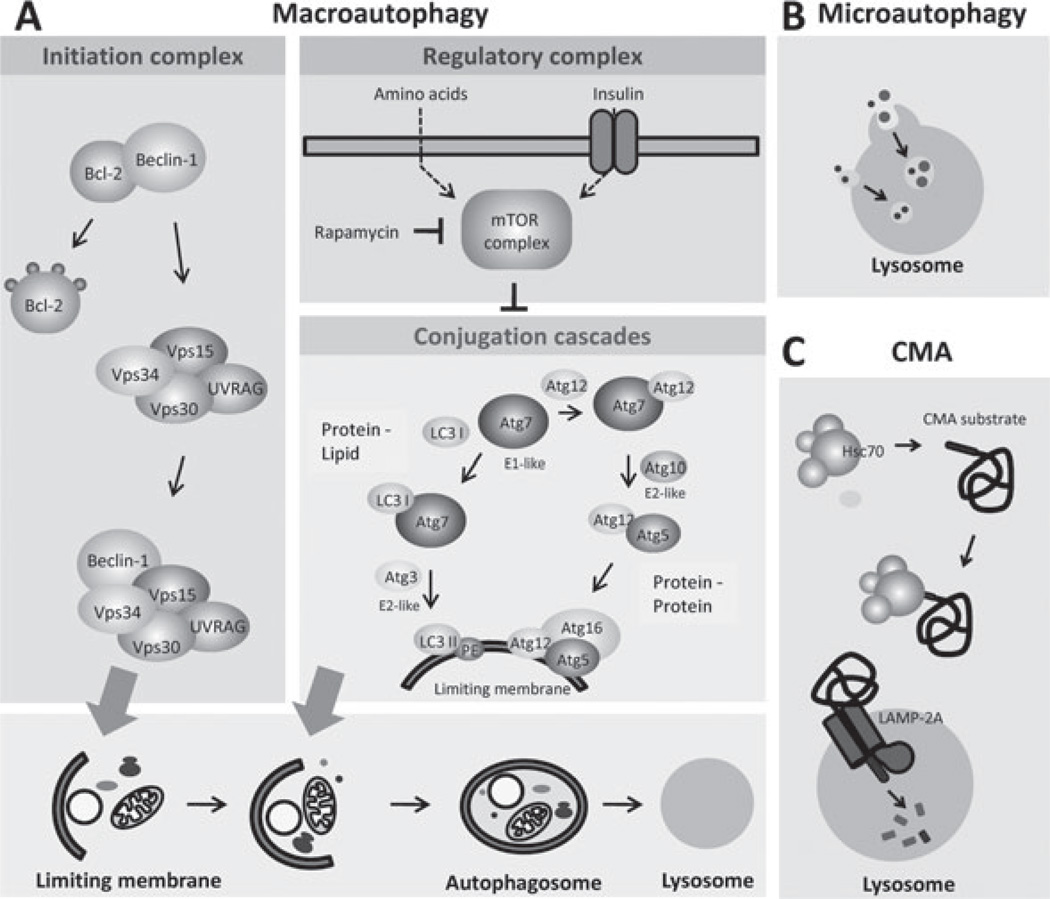

The autophagic variants differ in the mechanisms that mediate the delivery of cargo to lysosomes, their regulation and the subset of genes and proteins that act as effectors and modulators in each of them (figure 1). The three most common forms of autophagy are macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Variations of these autophagic pathways have been described according to the type of cytosolic component preferentially degraded. For example, selective degradation of mitochondria by macroautophagy is now termed mitophagy, of lipids lipophagy or of regions of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) ER-phagy [5,6].

Figure 1.

Autophagic pathways in mammalian cells. Three different types of autophagy co-exist in most types of mammalian cells. The major molecular components that participate in the execution and regulation of each of these autophagic pathways are depicted here. (A) Macroautophagy involves the sequestration of cytosolic regions by a de novo formed membrane that seals into a double membrane vesicle or autophagosome. Fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes is required for cargo degradation. Induction ofmacroautophagy leads to the mobilization of a protein kinase type III complex (the initiation complex) towards the sites of autophagosome formation. Lipid phosphorylation of this kinase complex is essential for the recruitment in these regions of the components of two conjugation cascades that mediate formation and elongation of the autophagosome membrane. The major negative regulator of macroautophagy, the mTOR protein kinase complex, is also depicted. (B) Microautophagy mediates the internalization of cytosolic cargo – proteins and organelles – through invaginations of the lysosomal membrane. The molecular components that participate in this autophagic process in mammals remain unknown. (C) Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) differs from the other autophagic pathways on the fact that substrates – only soluble cytosolic proteins – are selectively targeted to the lysosomal membrane by a cytosolic chaperone and they require unfolding before reaching the lysosomal lumen. Internalization of substrate proteins by this pathway is attained through the coordinated function of chaperones at both sides of the lysosomal membrane and a membrane protein (the lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A or LAMP-2A) that acts both as a receptor and as an essential component of the translocation complex.

Macroautophagy

In macroautophagy, a membrane forms de novo in the cytosol and as it elongates it seals and sequesters entire cytosolic regions (figure 1A) [7]. The double membrane vesicle resulting from this process (the autophagosome) is then mobilized towards the lysosomes and upon membrane fusion, the enzymes within the lysosomes gain access to the autophagosome cargo and degrade it [6]. Macroautophagy was first identified and characterized in mammals, specifically in rodent liver, using morphological approaches that quantified changes in the number and size of autophagosomes and lysosomes [8]. However, we owe the recent advances in the molecular dissection of this process to yeast screening studies that have helped to identify more than 30 different genes generically known as autophagy-related genes or ATG, which encode for protein products involved in the execution and regulation of macroautophagy [9]. Interested readers are referred to recent reviews that have described the function and interplay of each of the ATG in detail [1,6]. Briefly, Atg proteins organize in functional complexes that mediate each of the steps of macroautophagy: induction/initiation, nucleation, membrane elongation, cargo recognition, sealing and fusion with lysosomes. The essential components of the induction complex are Beclin-1 (Atg6 in yeast), vps15 and vps34 (figure 1A) [10,11]. The involvement of this complex in autophagy induction or in other cellular functions is modulated by the interacting partners such as Atg14L, UVRAG or rubicon [12]. Mobilization of the initiation complex to the site of autophagosome formation induces nucleation and generation of the limiting membrane, which is mediated by two protein conjugation cascades (figure 1A) [7]. These conjugation events resemble ubiquitin conjugation because they involve a subset of ligases that activate substrate and ligand and which enzymatically catalyse their conjugation. Two different conjugates result from these events; the Atg5-12 protein complex, in which both proteins are covalently linked, and the LC3–phosphatidylethanolamine complex, in which the lipid and the protein are also covalently linked [7]. These conjugation events occur on the surface of the forming membrane and mediate its elongation. Other Atgs have been shown to act in later steps where they mediate membrane sealing and fusion. Although the specific players in these steps are still poorly defined, studies in yeast support involvement of specific SNARE and rab proteins and the cytoskeleton [7,13,14]. In addition, the presence of negative regulators of macroautophagy prevents activation of this degradative process by sequestering some of the effector proteins in an inactive state. The best-known macroautophagy inhibitory complex is the TOR complex (TORC), which results from the association of the mammalian target of rapamicin (mTOR), a nutrient and energy-sensing kinase, with raptor and other modulatory proteins (figure 1A) [11,15]. TORC1 interacts with autophagy effectors (ULK-1, FIP200) [16], thereby preventing the activation of macroautophagy. When TORC1 activity decreases, such as under decreased nutrient conditions, the effectors of autophagy are released from this complex and recruited to the site of autophagosome formation, recently identified in the mammalian cells as discrete regions of the ER known as omegasomes [17]. Although maximal activation of macroautophagy is attained during stress conditions, such as nutritional deprivation, oxidative stress or organelle stress, basal activity of this pathway can also be detected in almost all cell types. Studies in mouse models with tissue-specific conditional knockout of essential autophagy genes have shown that basal macroautophagy is necessary for maintenance of cellular homeostasis in many tissues.

Microautophagy

Similar sequestration of a region of the cytosol occurs in microautophagy, but in this case the lysosomal membrane invaginates to surround the cargo, which is then internalized into the lysosomal lumen in single membrane vesicles (figure 1B) [18]. These cargo-containing vesicles then pinch off from the lysosomal membrane into the lumen where they are rapidly degraded. Degradation of both soluble proteins and organelles through microautophagy has been described in yeast, where a subset of proteins, some shared with macroautophagy and some unique for this process, have been identified. These proteinsmediate cargo recognition, sequestration by the vacuolar membrane (equivalent of lysosomes in yeast), internalization and degradation in the vacuolar lumen [19]. In contrast to the ATG genes that are conserved from yeast to humans, the mammalian homologues of the yeast genes unique for microautophagy have not been identified. The poor molecular characterization of the microautophagy components in mammals explains the limited understanding of this process in higher organisms.

Chaperone-mediated Autophagy

Better characterized within mammals is a third type of autophagy, CMA that mediates translocation of single proteins from the cytosol into the lysosomal lumen for their degradation (figure 1C) [2]. Unique to this form of autophagy is the selectivity in substrate targeting and the fact that substrate proteins cross the lysosomal membrane through a translocon-like complex [20]. Protein substrates for this pathway are identified in the cytosol by the constitutive member of the hsp70 chaperone family that recognizes a targeting motif in the amino acid sequence of the substrate [21]. The chaperone–substrate complex binds to a receptor protein at the lysosomal membrane that moves the substrate into the translocation complex. With assistance from a luminal-resident chaperone and after complete unfolding, the substrate protein crosses the lysosomal membrane into the lumen where it is rapidly degraded (figure 1C) [2,21]. Similar to macroautophagy, CMA is maximally activated under stress, such as prolonged nutritional deprivation, when it contributes to the removal of selective proteins that can be used as an internal source of amino acids. Activation of CMA during other types of stress also mediates the elimination of proteins damaged by the stressor [2]. In addition, basal CMA activity has also been described in most mammalian cells that contributes to the maintenance of cellular homeostasis [22].

Protein Homeostasis and Autophagy

Proteins are continuously synthesized and degraded inside cells at rates depending on the specific protein and on the cellular conditions. De novo protein synthesis requires their spontaneous or assisted folding to acquire a stable conformation, whereas degradation often requires complete protein unfolding that allows proteases to gain access to the peptide bonds [23]. In addition, proteins unfold and refold when crossing membranes to access the lumen of different organelles and when proteins organize in functional multiprotein complexes. These frequent protein folding and unfolding events occur both in the cytosol and in the lumen of particular organelles, and often require chaperones to prevent non-specific interactions between proteins that are undergoing conformational changes and the surrounding ones [23]. Coordinated function between the chaperones and the proteolytic systems guarantees removal of proteins that are unsuccessful in attaining a stable conformation inside the cells. Failure to remove these proteins leads to their accumulation either in the cytosol or inside organelles with the subsequent cytotoxic effects [24].

Cytosolic Proteotoxicity: Protein Conformational Disorders and Aggregopathies

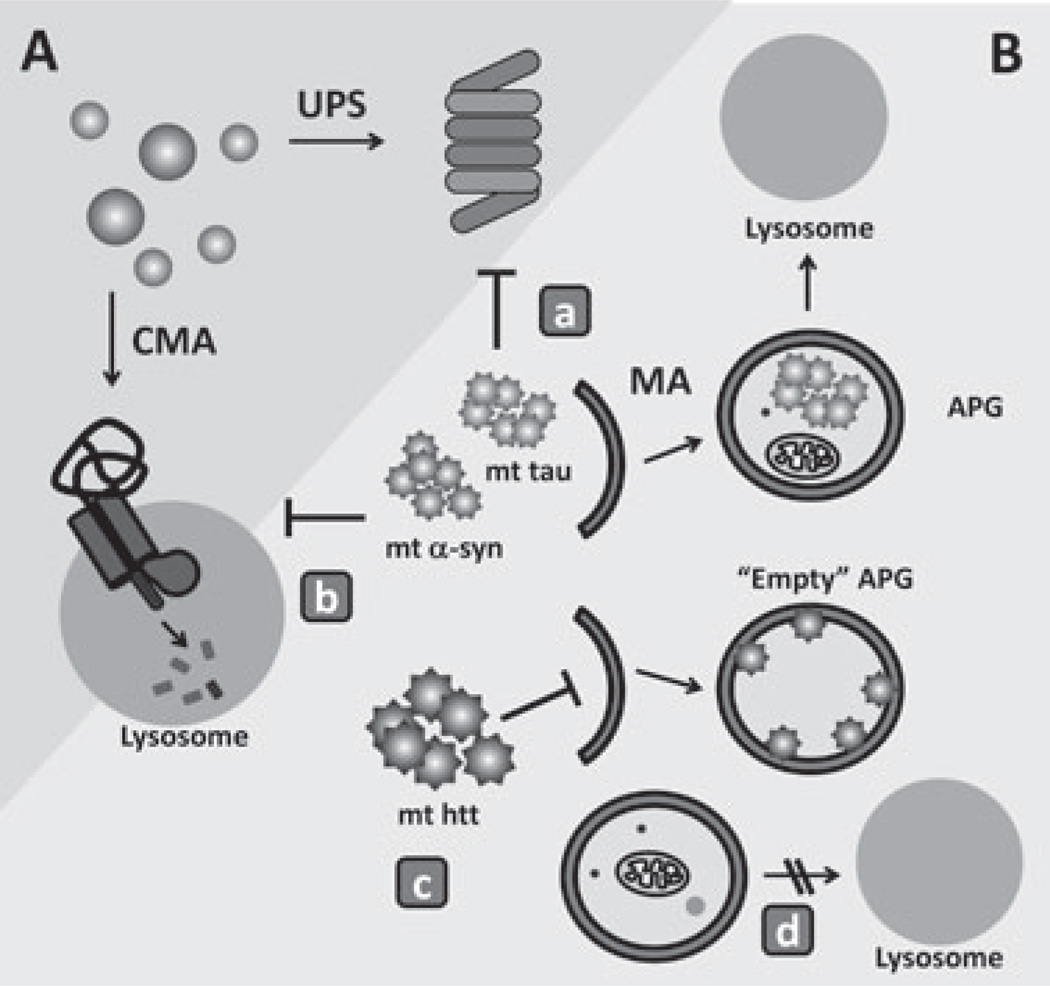

All proteins undergo a continuous process of synthesis and degradation that guarantees proper maintenance of the cellular proteome through renewal. Autophagy and the ubiquitin proteasome system contribute to this physiological protein degradation. In addition, these proteolytic systems also participate in the removal of altered proteins. Most cytosolic proteins fold spontaneously as they come out of the ribosome or reach a stable conformation with the assistance of cytosolic chaperones and chaperonins. However, a subset of newly synthesized proteins never fold and are eliminated to prevent their organization into oligomers or aggregates that are often toxic to cells [23].Both the ubiquitin proteasome system andautophagy contribute to the degradation of misfolded cytosolic proteins (figure 2) [25]. Active removal through these degradative systems is particularly critical in pathological conditions that result from mutations or post-translational changes in a specific protein that make it prone to aggregation (i.e. huntingtin in Huntington’s disease or α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease).

Figure 2.

Autophagy in the defense against cellular proteotoxicity. (A) Soluble cytosolic proteins can normally undergo selective degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) or in the lysosome via chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). (B) Once proteins organize into abnormal protein complexes (protein oligomers or aggregates), they are no longer amenable for degradation through the above-mentioned pathways,which require complete unfolding of the protein substrate before degradation. Aggregated pathogenic proteins [mutant tau, α-synuclein and huntingtin (htt) are depicted here] can only be removed from the cytosol by macroautophagy. The presence of these pathogenic proteins can affect functioning of the different proteolytic systems. Mutant forms of α-synuclein and tau, for example, have been shown to directly inhibit the proteolytic activity of the UPS (a). In addition, the inability of these mutant proteins to cross the lysosomal membrane when targeted to lysosomes via CMA results in blockage of this autophagic pathway (b). Pathogenic forms of htt have been shown to diminish normal macroautophagy activity by directly interfering with the recognition of cargo by the limiting autophagosome membrane, giving instead rise to ‘empty’ autophagosomes (APGs) (c). Later steps in macroautophagy, for example, APG trafficking or autophagosome–lysosome fusion (d), are also susceptible to the effect of pathogenic proteins.

Selective Autophagic Removal of Pathogenic Proteins

When selective removal of the damaged or modified protein occurs in the proteasome, targeting is often attained through ubiquitinization of the protein (figure 2A) [26]. In contrast, if the pathogenic protein contains within its amino acid sequence the CMA-targeting motif, the protein can be recognized by hsc70 in the cytosol and then targeted for degradation within lysosomes (figure 2A) [27]. Numerous oxidized proteins can, in fact, be degraded by this autophagic pathway. CMA substrates aremore readily degraded by CMA when they become oxidized, maybe in part because of better recognition by the chaperone or because of the partial unfolding, which often occurs in oxidized substrates, and that will reduce the time required for unfolding/ translocation across the lysosomal membrane [28]. Activation of CMA upon mild oxidative stress has been observed in many different types of cells in culture and in different tissues of rodents [28]. Upregulation of this autophagic system under these conditions is attained through transcriptional increase in the CMA receptor at the lysosomal membrane. Cultured cells experimentally impaired for CMA display reduced cellular viability when exposed to oxidants and pro-oxidants, confirming that upregulation of CMA is part of the cellular defense against oxidative stress [22]. Recent studies from our group have shown that the previously described decline of CMA activity in aging is, in part, responsible for the accumulation of oxidized proteins in tissues of old organisms. CMA activity decreases with age mainly because of a decrease in the levels of the lysosomal receptor for this pathway in old organisms. Using genetic manipulations, we have generated a transgenic mouse model in which CMA activity is preserved until late in life in the liver. Comparative analysis of the livers of these transgenic mice at 22–26 months of age with wild-type littermates has shown a marked reduction in the content of oxidized and aggregated proteins and lower levels of lipofuscin, the autofluorescent material that accumulates in old cells because of poor digestion of the lysosomal content. The livers of these animals are better prepared to respond to cytotoxic insults, reflected by the lower levels of apoptosis observed in the old transgenic mice when subjected to different stressors. Furthermore, livers from mice with preserved CMA function until late in life show lower functional decline of the whole organ than their wild-type littermates. All these findings support the importance of functional CMA in maintaining proper cellular protein homeostasis [29].

Conversely, malfunctioning of CMA has been associated with the pathogenesis of different protein conformational disorders. For example, a portion of intracellular α-synuclein, the protein that when mutated or post-translationally modified accumulates in the affected neurons in Parkinson’s disease, has been shown to undergo degradation through CMA both in vitro and in vivo (figure 2B) [30]. In contrast, pathogenic mutant forms of this protein are also targeted to lysosomes by the cytosolic chaperone associated with CMA and bind to the lysosomal receptor for this pathway, but fail to translocate across the lysosomal membrane [30]. The unusual high affinity of binding of mutant forms of α-synuclein to the CMA translocation complex interferes with the normal activity of this complex and results in diminished CMA in the affected cells [30]. Similar effects have been observed when α-synuclein undergoes specific pathogenic post-translational modifications such as the formation of intracellular adducts with dopamine [31]. Consequently, in addition to the cytotoxicity resulting from the accumulation of pathogenic α-synuclein in the cytosol, the partial blockage of CMA may also contribute to the vulnerability to stress, characteristic of the affected neurons. This inhibitory effect on CMA has also been recently observed for other pathogenic proteins. For example, mutant forms of the ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1), another protein associated to Parkinson’s pathogenesis, abnormally interact with the CMA receptor at the lysosomal membrane, although the functional consequences of this interaction remain unknown [32]. Likewise, mutant forms of tau, the cytoskeleton-associated proteins that accumulate in the form of neuronal toxic filaments in certain tauopathies, are also targeted for degradation via CMA (figure 2B). Similar to mutant α-synuclein, pathogenic tau proteins are also targeted to the lysosomal membrane but fail to reach the lysosomal lumen through CMA [33]. In this case, added to the blockage on CMA, the incomplete lysosomal translocation of mutant tau favours its cleavage into a highly amyloidogenic peptide. Part of this peptide falls into the cytosol where it acts as seeding material for aggregation. Formation of amyloid-like structures also occurs on the surface of lysosomes leading to destabilization of their membranes, lysosomal enzyme leakage and further cellular toxicity. Recent studies have also established a connection between CMA and pathogenic huntingtin, the protein that accumulates both in the cytosol and the nucleus in Huntington’s disease. In contrast to α-synuclein, wild-type huntingtin does not seem to normally undergo degradation through CMA, despite the CMA-targeting motifs identified in its amino acid sequence [34].However, somepost-translational modifications, such as acetylation, induce degradation of the mutant protein through CMA. In fact, upregulation of CMA under these conditions reduces the toxicity associated to mutant huntingtin [34].

Removal of Protein Aggregates by Macroautophagy

Part of the toxicity associated with protein damage or intracellular accumulation of pathogenic proteins results from the harmful effect of these proteins on the proteolytic systems. Pathogenic α-synuclein and tau have been shown to contribute to proteasome dysfunction [33,35] and as described in the previous section, both exert an inhibitory effect on CMA. Part of their toxic effect originates once these proteins lose their solubility and organize into complex multiprotein structures (oligomers, aggregates, etc.) in the cytosol. Once in these conformations, the pathogenic proteins are no longer amenable for degradation by the proteasome or CMA, which can only degrade single unfolded proteins. Macroautophagy has been shown as the only proteolytic pathway able to degrade pathogenic proteins when organized into these non-degradable structures (figure 2B). In fact, upregulation of macroautophagy has been found in many different protein conformational disorders [36]. Furthermore, chemical and genetic upregulation of macroautophagy has been shown to reduce cellular toxicity and slow down progression of disease in animal models of Huntington’s disease [15]. It is likely that part of the beneficial effect of these interventions results from the direct removal of protein aggregates by macroautophagy, but in part can also originate from the in-bulk degradation of still soluble forms of the pathogenic proteins that are usually in balance with the aggregated products.

One of the topics of intensive research nowadays regarding macroautophagy of protein aggregates is the mechanism(s) that leads to their recognition as autophagic cargo. In fact, recent studies have shown that not all protein aggregates are amenable for degradation through macroautophagy [37]. This failure to degrade some intracellular protein inclusions does not originate from their resistance to degradation by the lysosomal enzymes, but from a defect that occurs at an early step that prevents the recognition of the protein aggregate by the lysosomal system. Thus, even in cells with intact macroautophagy activity, some protein aggregates escape the surveillance of the autophagic system. A group of cargo recognition molecules for macroautophagy has recently emerged, with p62 being the first member identified from this protein family [38]. A common characteristic of these cargo-recognizing proteins is that they all bear two distinctive domains, one that interacts with components of the autophagic machinery – often LC3 – and a second domain that binds a specific component in the intracellular structure – organelle, protein aggregate or even pathogen – that will become the autophagic cargo. In the case of protein aggregates, cargo-recognizing molecules, such as p62 or NBR1, recognize specific linkages of ubiquitin in the aggregated proteins [39].Unexpectedly, protein inclusions that escape macroautophagy surveillance do contain p62 on their surface, suggesting that although p62 is necessary for protein aggregate removal it is not sufficient, and that yet unidentified components are also needed for their clearance [37].

Macroautophagy is however vulnerable to the effects of different pathogenic proteins and, indeed, malfunctioning of this pathway underlies the pathogenesis of some severe protein conformational disorders. We have recently described a failure of macroautophagy to recognize cargo in different cellular and animal models of Huntington’s disease as well as in cells from patients with Huntington’s disease [40]. The formation of autophagosomes, sealing and clearance of the autophagic vesicles by the lysosomal system occur normally in these cells. However, most of the autophagosomes in the affected cells have the appearance of ‘empty’ vesicles as they fail to sequester organelles such as lipid droplets or mitochondria (figure 2B). Abnormally enhanced interaction between p62 and pathogenic huntingtin on the luminal side of the forming autophagosome-limiting membrane could be the reason for the failure to selectively recognize particulate cargo. Impairment in macroautophagic activity has also been described in Alzheimer’s disease, although in this case the primary defect occurs at a later step in macroautophagy [41]. Autophagosome formation and cargo recognition occur normally, but autophagosome content cannot be degraded by the lysosomes. This degradation failure is partly because of problems with fusion between both compartments, but mainly to problems with proteolytic breakdown once fusion has taken place (figure 2B). Identifying the macroautophagic step or steps affected in different pathologies is essential to device future therapeutic strategies. Thus, a defect in macroautophagy induction or autophagosome formation should benefit from interventions aimed at stimulating autophagy. In contrast, problems in autophagosome clearance, as the ones described in Alzheimer’s disease, may be better resolved if lysosomal breakdown is stimulated, or if this is not possible, reducing rather than enhancing autophagosome formation should provide cells with a relief from the abnormal accumulation of autophagic vacuoles observed in the affected cells.

Organelle Proteotoxicity

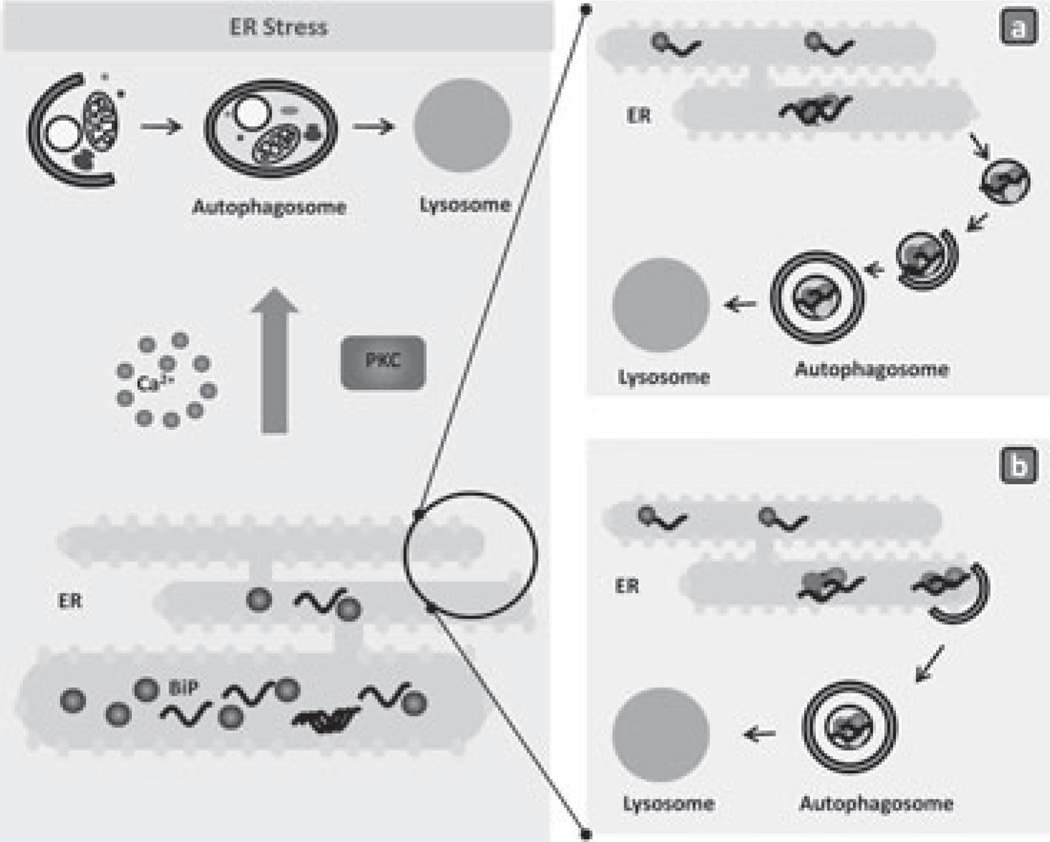

Protein folding and maintenance of a stable protein conformation could become a real challenge in certain organelles under particular cellular conditions. Proteotoxicity has been well studied in the ER, an organelle responsible for the bulk of synthesis of secretory proteins [42]. Difficulty in the folding of de novo synthesized proteins once inside the ER lumen and their subsequent accumulation in this compartment elicits a cellular stress response known as unfolding protein response (UPR), which is described in detail in other parts of this focused issue [43]. Immediate consequences of the UPR are the attenuation of protein translation to reduce the amount of newly synthesized proteins reaching this compartment and transcriptional upregulation of ER chaperones to assist folding of the unfolded proteins. A successful UPR resolves the folding issues and allows the refolded proteins to continue their course through the secretory pathway. However, if the UPR does not return ER homeostasis to normal conditions, mechanisms that mediate the degradation of the unfolded proteins are activated to prevent ER proteotoxicity [24]. Until very recently, this was a task attributed solely to the ubiquitin proteasome system through what is known as ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Unfolded ER proteins are retrotranslocated out of this compartment by still poorly understood mechanisms, and once in the cytosol the unfolded proteins undergo trimming of the sugar groups followed by ubiquitinization that targets them to degradation through the 26S proteasome [44]. In recent years, the participation of macroautophagy in ER quality control has also been shown (figure 3). Two early studies in yeast showed that ER stress induces activation of macroautophagy and that this activation is required for cellular survival, indicating the cytoprotective role of macroautophagy under those conditions [45,46]. Removal of whole ER regions by macroautophagy, visible as ER stacks packed inside autophagosomes, was observed, leading to the proposal that macroautophagy helps in recovering normal ER size after stress [45]. The important role of autophagy in cell survival after ER stress has been confirmed in different types of cells (neuroblastoma, hepatocytes, kidney tubular cells, etc.) [47–50].

Figure 3.

Autophagy and proteotoxic stress in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).Accumulation of misfolded de novo synthesized proteins in the lumen of the ER activates a cellular response that facilitates protein folding by increasing the luminal content of assisting chaperones. However, in certain conditions, failure of this stress response leads to the formation of protein aggregates in the ER lumen that can only be removed through activation of macroautophagy. Calcium and specific cytosolic kinases, such as protein kinase C depicted here, have been proposed as molecular links between ER stress and activation of macroautophagy. The mechanistic aspects of the degradation of the ER by macroautophagy are still poorly understood. It is possible that regions of the ER containing the aggregated proteins bud off into cytosolic vesicles that are then sequestered by autophagosomes (a). Taking into account that autophagosome formation occurs from specialized regions of the ER membrane, it is also possible that when aggregated proteins accumulate in the ER lumen, the autophagosome-limiting membrane elongates around the ER periphery and gives rise to autophagosomes through combined sequestration and pinching-off processes (b).

The specific mechanisms leading to macroautophagy activation during ER stress remain poorly understood. Components of the ER upregulated during UPR, such as GRP78/BiP (binding immunoglobulin protein) or the UPR arm depending on IRE1-TRAF2 (Inositol-requiring 1-TNF receptor-associated factor 2), have been shown to be required for activation of macroautophagy in response to ER stress [48,51]. Conversely, autophagy also seems to exert a regulatory role in the UPR, because both knockdown of essential autophagic genes or chemical inhibition of macroautophagy suppresses UPR activation [51].Different kinases act as mediators of the signal from the ER to the autophagic machinery, such as JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) [48], calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase B, AMP-activated protein kinase [52] and protein kinase C (figure 3) [50]. Interestingly, some of these kinases are not required when macroautophagy is induced by a different stimulus, such as starvation [50], suggesting that there is a dedicated signalling mechanism for the activation of ER stress-induced autophagy. Recent studies have proposed eukaryotic elongation factor-2 (eEF-2) as a possible integrator of various stressors for autophagy signalling, and connections with ER stress have also been established, although the contribution of eEF-2 to the ER-induced autophagic response seems to be very context dependent [53]. It is also possible that depending on the conditions that induce ER stress, the mechanism of macroautophagy induction could be different. For example, the cytosolic release of calcium from the ER that occurs during ER stress induced by thapsigargin inhibits mTOR, the negative regulator of macroautophagy, through a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase [52]. This mechanism is thus unique to ER stress induced by calcium-mobilizing agents only. The mechanisms that contribute to ER sequestration by autophagosome remain still unknown, but different theoretical possibilities are depicted in figure 3.

Remarkably, maintained ER stress-induced autophagy, against all the logical predictions, can be beneficial at the cellular level, at least under pathological conditions. Thus, a mouse model with an impairment in one of the arms of the UPR (XBP-1-deficient mice) and consequently displaying augmented basal ER stress has been shown to be protected against neurodegeneration induced by protein aggregation [54]. This protective effect depended on having a functional autophagic system, supporting that maintained upregulation of macroautophagy in response to ER stress has a protective effect against conditions altering protein homeostasis.

Although recent studies have shown a connection between mitochondrial UPR and specific components of the ubiquitin proteasome system, the role of autophagy in mitochondrial stress and in response to proteotoxicity in other organelles is still unknown [55,56].

Autophagic Pathways and Lipid Metabolism

Until very recently, autophagic activity was linked to protein and organelle turnover, but there were no clear connections between this degradative pathway and lipid metabolism. However, during the last 2 years, several studies have unveiled previously unknown reciprocal interactions between autophagic pathways and intracellular lipids, heralding a new area of research.

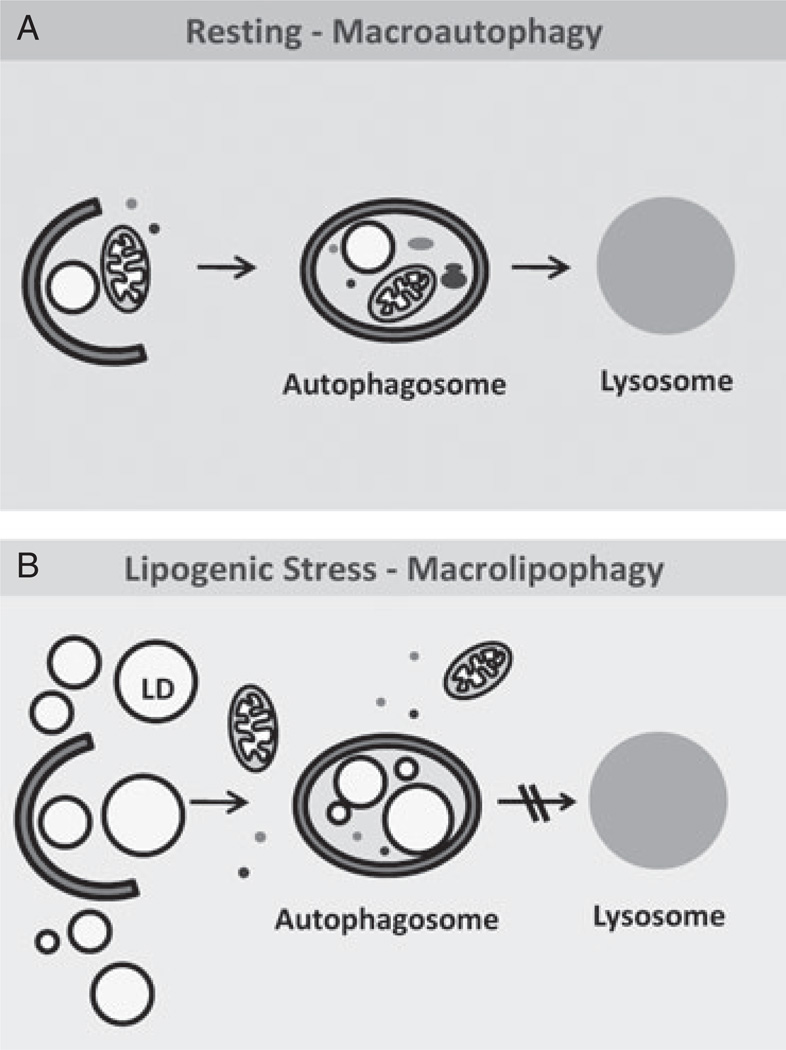

Macroautophagy in the Control of Intracellular Lipid Stores

Lysosomes contain potent lipases that, until recently, were considered to contribute only to the degradation of lipids reaching the lysosome through the endocytic pathway. However, recent studies have shown that lysosomal lipases can contribute actively to intracellular lipolysis resulting from degradation of lipid droplets delivered to this compartment via macroautophagy. Morphometric studies have shown that blockade of macroautophagy, through chemical inhibitors or by genetic manipulation, led to a marked increase in the number and size of intracellular lipid droplets in cultured cells [57]. This increase was not because of changes in lipid droplet biogenesis or alterations in lipid secretion in these cells, but directly because of reduced lipolysis of these lipid stores. Although the initial studies were performed in hepatocytes in culture, similar accumulation of lipids upon autophagic compromise has been now described in many other cell types, including even neuronal cells [40], supporting the view that this could be a generalized mechanism for the regulation of number and size of lipid stores in cells. The contribution to lipid metabolism of this process, now termed macrolipophagy, was also confirmed in vivo using a genetic mouse model with impaired hepatic macroautophagy (figure 4). The livers of these animals displayed higher intracellular levels of both cholesterol and triglycerides, the main components of the lipid droplets [57]. The differences in lipid content between control and macroautophagy-incompetent animals became even more evident upon a lipogenic stimulus such as a high-fat diet. The specific mechanisms that contribute to the delivery of lipid droplets to lysosomes through macroautophagy are not completely elucidated. However, both global sequestration of the whole lipid droplet by autophagosomes and partial trapping of portions of the droplet by the limiting membrane of the autophagosome seem to occur, probably depending on the size of the lipid droplet (figure 4) [57]. Interestingly, LC3, the protein that upon conjugation with lipids becomes an essential component of the autophagosomes, can be detected normally on the surface of lipid droplets as the unconjugated protein (LC3-I). Under conditions that favour lipolysis (i.e. prolonged starvation), conjugation of LC3 occurs on the surface of the droplets and is likely what drives the formation of the limiting membrane of the autophagosome directly on the droplet.

Figure 4.

Autophagy and lipid metabolism. (A) Basal macroautophagy contributes to continuous mobilization of small amounts of lipids stored in the cell in the form of lipid droplets (LDs). Portions of an LD or whole LDs are often detected along with other cytosolic components inside autophagosomes. (B) Upon lipogenic stress, macroautophagy can be maximally activated to prevent massive accumulation of lipids intracellularly. Under these conditions, degradation of LDs is favoured while other intracellular components are excluded from the autophagosome. Based on this selectivity towards lipid stores, this type of macroautophagy has been termed macrolipophagy.

Lipid droplets are thus part of the common cargo of autophagosomes, but in particular conditions, for example, prolonged starvation or a lipogenic stimulus, there is a switch that favours the sequestration and degradation of lipid droplets over other intracellular components (figure 4) [57]. One direct implication of these findings is that in situations with compromised macroautophagy, as for example in neurodegenerative disorders or in aging, added to the problems in cellular quality control, there could be problems in the mobilization of lipid stores that could contribute to energetic imbalance. The extent to which macrolipophagy failure contributes to pathogenesis in these disorders will require further investigation.

In contrast to the increase in autophagy observed in response to an acute lipogenic stimulus, maintained chronic lipogenic stimulus or abnormally high levels of lipids, even upon acute exposure, lead to macroautophagy dysfunction. Rodents on a high-fat diet for 4 months or longer show a reduced ability to mobilize lipid droplets by macroautophagy [57]. Interestingly, the autophagic defect is not limited to degradation of lipids, but it affects degradation of any type of autophagic cargo, pointing rather to a primary defect in the macroautophagic machinery [58]. A systematic analysis of the different steps involved in macroautophagy – induction, autophagosome formation, autophagosome–lysosome fusion and degradation – has shown that the inhibitory effect of high intracellular lipid content is exerted at the level of autophagosome–lysosome fusion [58].Changes in the lipid composition of the membranes involved in this fusion event have shown to have amarked effect on the fusiogenic ability of these compartments. In fact, membrane cholesterol seems to play an important role in these fusion events, because experimental treatments that modify the concentration of cholesterol in the membrane of autophagosomes or of lysosomes in vitro are enough to reproduce deficiencies in vesicular fusion [58]. Failure to fuse with lysosomes is partially compensated through fusion of autophagosomes with late endosomes to form amphisomes. However, degradation through this mechanism is considerably more inefficient and results in a decrease in net degradation rates. This novel inhibitory effect of intracellular lipids on macroautophagy could contribute to perpetuate conditions, such as the metabolic syndrome of aging, in which problems in lipid metabolism associate with reduced rates of macroautophagy.

Macroautophagy in Adipose Tissue

As indicated in the previous section, macrolipophagy seems to be one of the mechanisms that contribute to mobilization of lipid stores in many types of cells. However, recent studies have shown a novel, yet paradoxical function of macroautophagy in the regulation of adipose tissue differentiation and fat storage [59,60]. Inhibition of macroautophagy in cultured preadipocytes blocked triglyceride accumulation and reduced the expression of critical adipogenic transcription factors such as CEBP-α (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha) and PPAR-γ, as well as the terminal differentiation markers such as fatty acid-binding protein-4 (FABP-4/aP-2), fatty acid synthase and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4). Interestingly, white adipose tissue (WAT)-specific inhibition of macroautophagy in vivo through knockout of an essential macroautophagy gene in this tissue not only decreased adipose mass and differentiation but also imparted a brown adipose tissue-like phenotype to the macroautophagy-deficient adipocytes. This was reflected by increased levels of the brown adipogenic factors PPAR-γ transcriptional co-activator (PGC-1 α) and uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1), a higher mitochondrial content and higher β-oxidation rates in the adipose tissue of the knockout animals when compared with control littermates [59,60].

The physiological consequences of this remarkable alteration in WAT morphology and function were reduced body weight and protection against insulin resistance, despite a high-fat diet feeding [59,60]. The mechanism by which macroautophagy mediates the switch from WAT to brown fat-like characteristics is still unknown. It is possible that macroautophagy actively regulates the complex interplay of transcription factors that govern adipogenesis and differentiation by modulating their intracellular levels through degradation. Another possibility is that macroautophagy alters the local metabolic milieu that favours adipogenesis. Nevertheless, these exciting findings present macroautophagy as a novel therapeutic target that could be potentially manipulated to regulate adipose tissue mass, obesity and peripheral insulin sensitivity.

Lipids as Regulators of Macroautophagy

A growing body of evidence now supports an important regulatory role of intracellular lipids in different autophagic pathways. Added to the above-described function of cholesterol in vesicular fusion, functional lipids such as phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P) have been described to be associated with different autophagic compartments where they exert specific functions. During macroautophagy, there is a massive transport of PI3P to the vacuole – the equivalent of the lysosome in yeast [61]. This delivery is not as cargo but as a component of the inner membrane of the autophagosome membrane, thereby supporting an involvement of PI3P in autophagosome formation. In fact, the first link between PI3P and autophagy came from studies in yeast, which showed that this lipid is required for the formation of the preautophagosomal structure [62]. This structure is shared in yeast between macroautophagy and the cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway, a biogenic pathway that mediates delivery of hydrolases to the vacuole. The recruitment of different Atg proteins to these preautophagosomal structures in a PI3P-dependent manner is mediated by the yeast Atg18 or Atg21 that binds directly to PI3P [63]. In fact, the loss of Atg21 [64] or Atg18 [65] results in the absence in the preautophagosomal of the two final products of the conjugation cascades (Atg5/12 and Atg8). The major source of PI3P required in this process is the lipid kinase vps34, the only PI3K in yeast [61]. Similarly, the kinase activity of the mammalian vps34, the main component of theBeclin-1nucleation complex, is also essential for the formation of autophagosomes [12,66]. In mammals, a PI3P-enriched compartment in the ER, which forms near vps34-containing vesicles, has been shown to provide a membrane platform for accumulation of autophagosomal proteins required for expansion of the limiting membrane of the autophagosome [67]. These particular regions of the ER, named omegasomes, can be identified by their enrichment in a PI3P-binding protein present on ER and Golgi (double FYVE domain-containing protein 1 or DFCP-1) [67]. DFCP-1 translocates to the omegasome areas in response to starvation in a vps34- and Beclin-1-dependent manner.

The regulatory role of PI3P and its association with autophagy components is not limited to the autophagosome formation step. The autophagy-linked FYVE protein (Alfy), a PI3P-binding protein, has been proposed to target cytosolic protein aggregates for autophagic degradation [68]. Although the requirements for PI3P binding in this process are not clear, the fact that Alfy can be localized at the autophagosome membrane, in these conditions, suggests that this protein acts as a direct link between aggregated proteins and the limiting membrane. Recently, another PI3P-binding protein, FYCO1 (FYVE and coiled-coil domain-containing protein), has been identified as a Rab7 effector that binds to LC3 and PI3P to mediate microtubule plus end-directed transport of the autophagosomes [69]. Lastly, PpAtg24, a sorting nexin with a PI3P-binding module, has been shown to be essential to mediate fusion between the vacuole and autophagosomes carrying peroxisomes in yeast (macropexophagy) [70].

Intracellular levels of PI3P result from a balance between kinase and phosphatase activities. Although there is a considerable progress in understanding the role of specific kinases in the regulation of the levels of PI3P required for macroautophagy, the analysis of the function of specific phosphatases in the same process has just begun. One of the first PI3P phosphatases shown to have a negative regulatory role on macroautophagy is Jumpy [71]. This phosphatase modulates the recruitment of WIPI-1 (WD repeat domain, phosphoinositide interacting 1; the mammalian homologue of the yeast Atg18) to the isolation membrane of the autophagosome. A catalytically inactive Jumpy, found in the congenital disease centronuclear myopathy, lost the ability to negatively regulate autophagy [71].

Intracellular Lipids and CMA

The interplay between lipids and autophagy is not limited to macroautophagy, but a connection between the organization of structural lipids at the lysosomal membrane and CMA has also been identified [72]. Lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP-2A), the receptor for this autophagic pathway, has been found to associate in a dynamic manner to lipid microdomains at the lysosomal membrane. Recruitment of LAMP-2A to these cholesterol-enriched domains occurs mainly in conditions of low CMA activity, whereas the protein is excluded from the microdomains when CMA is maximally activated [72]. Further analysis has shown that LAMP-2A undergoes a regulated degradation in these regions mediated by two proteases, the serine protease cathepsin A and a yet unidentified metalloprotease, that also localize in these regions [72]. Consequently, the changes in the lipid composition of the lysosomal membrane have a marked effect on CMA activity. Disruption of the lysosomal membrane microdomains with cholesterol-extracting agents results in enhanced CMA activity by preserving LAMP-2A from degradation, whereas experimental increase in the lysosomal membrane cholesterol content exerts an inhibitory effect on CMA [72]. Changes in the lipid composition of the lysosomal membrane could thus be behind CMA malfunctioning in particular conditions. For example, the age-dependent decline in levels of LAMP-2A, mainly responsible for the reduced activity of this pathway in aging, seems to originate from increased instability of this receptor at the lysosomal membrane [73]. Changes in the lipid composition of the lysosomal membrane with age have been shown to be behind the inability of LAMP-2A to incorporate in specific membrane microdomains and to undergo regulated cleavage. As a consequence, this protein is massively degraded in the lysosomal lumen, likely through its internalization in membrane invaginations [73].

Concluding Remarks and Unsettled Questions

In recent years, we have gained a better understanding of the connections between autophagy and different types of metabolic stress. The field has evolved to the realization that the involvement of autophagy in cellular metabolism goes beyond the somehow limited original perception of autophagy merely as an internal source of amino acids during nutrient starvation. The contribution of autophagy to cellular homeostasis by preventing proteotoxicity has now been illustrated by the protective role of this degradative pathway in different protein conformational disorders. Furthermore, autophagy has also been shown to be essential in the defense against cellular lipotoxicity, by actively participating in the control of the abundance of intracellular lipid deposits.

There is still a long list of mechanistic details that need further clarification. Probably very close to the top of this list is the need for a better understanding of the mechanism that mediates cargo recognition during specialized macroautophagy. Although some cargo-recognizing molecules have already been identified, their interplay with the components of the macroautophagic pathway is still obscure, and similar molecules are still lacking for the identification of cargo of high relevance from the metabolic point of view, such as lipid droplets. Also puzzling is the dual role that macroautophagy exerts in biogenesis and degradation of these lipid droplets in the adipose tissue. The complexity of the regulatory mechanisms and effector molecules that can lead to the formation of autophagosomes has given rise to the tantalizing idea that maybe there are different ways to ‘make’ an autophagosome depending on the stimulus that initiates the need for their formation. For example, activation of macroautophagy for removal of misbehaving proteins could follow very different rules to its activation in response to nutrient deprivation or to a lipogenic stimulus. The future challenge will be to mix and match the different autophagy stimuli with distinctive autophagy effectors and regulators.

Lastly, a better understanding of the molecular mediators of the cross-talk between autophagic and non-autophagic proteolytic systems could provide new therapeutic targets for the modulation of the cellular defense against metabolic stress.

Acknowledgements

Work in our laboratory is supported by NIH grants from NIA (AG021904, AG031782), NIDDK (DK041918), NINDS (NS038370), a Glenn Foundation Award and a Hirsch/Weill-Caulier Career Scientist Award. S. K. and R. S. are supported by NIA T32AG023475 and NIDDK K01 (DK087776-01) awards, respectively.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

The authors do not declare any conflict of interest relevant to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: selectivity pays off. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizushima N. The pleiotropic role of autophagy: from protein metabolism to bactericide. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1535–1541. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deretic V. Links between autophagy, innate immunity, inflammation and Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis. 2009;27:246–251. doi: 10.1159/000228557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuervo AM. Autophagy: many paths to the same end. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;263:55–72. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000041848.57020.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, et al. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature. 1998;395:395–398. doi: 10.1038/26506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seglen P, Bohley P. Autophagy and other vacuolar protein degradation mechanisms. Experientia. 1992;48:58–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01923509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klionsky DJ, Cregg JM, Dunn WA, Jr, et al. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy-related genes. Dev Cell. 2003;5:539–545. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang X, Jackson S, Seaman M, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by Beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pattingre S, Espert L, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Codogno P. Regulation of macroautophagy by mTOR and Beclin 1 complexes. Biochimie. 2008;90:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kochl R, Hu X, Chan E, Tooze S. Microtubules facilitate autophagosome formation and fusion of autophagosomes with endosomes. Traffic. 2006;7:129–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishihara N, Hamasaki M, Yokota S, et al. Autophagosome requires specific early Sec proteins for its formation and NSF/SNARE for vacuolar fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3690–3702. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:585–595. doi: 10.1038/ng1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1981–1991. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker S, Chandra P, Manifava M, Axe E, Ktistakis NT. Making autophagosomes: localized synthesis of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate holds the clue. Autophagy. 2008;4:1093–1096. doi: 10.4161/auto.7141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahlberg J, Glaumann H. Uptake—microautophagy—and degradation of exogenous proteins by isolated rat liver lysosomes. Effects of pH, ATP, and inhibitors of proteolysis. Exp Mol Pathol. 1985;42:78–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(85)90020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan W, Tuttle DL, Shi YJ, Ralph GS, Dunn WA., Jr Glucose-induced microautophagy in Pichia pastoris requires the alpha-subunit of phosphofructokinase. Journal Cell Sci. 1997;110:1935–1945. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.16.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandyopadhyay U, Kaushik S, Vartikovsky L, Cuervo AM. Dynamic organization of the receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5747–5763. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02070-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dice J. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;3:295–299. doi: 10.4161/auto.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Massey AC, Kaushik S, Sovak G, Kiffin R, Cuervo AM. Consequences of the selective blockage of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5905–5910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507436103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Large AT, Goldberg MD, Lund PA. Chaperones and protein folding in the archaea. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:46–51. doi: 10.1042/BST0370046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Douglas PM, Summers DW, Cyr DM. Molecular chaperones antagonize proteotoxicity by differentially modulating protein aggregation pathways. Prion. 2009;3:51–58. doi: 10.4161/pri.3.2.8587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morimoto RI. Proteotoxic stress and inducible chaperone networks in neurodegenerative disease and aging. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1427–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1657108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciechanover A, Brundin P. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurode-generative diseases. Sometimes the chicken, sometimes the egg. Neuron. 2003;40:427–446. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiang H, Terlecky S, Plant C, Dice JF. A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science. 1989;246:382–385. doi: 10.1126/science.2799391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiffin R, Christian C, Knecht E, Cuervo A. Activation of chaperone-mediated autophagy during oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4829–4840. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C, Cuervo AM. Restoration of chaperone-mediated autophagy in aging liver improves cellular maintenance and hepatic function. Nat Med. 2008;14:959–965. doi: 10.1038/nm.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PTJ, Sulzer D. Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science. 2004;305:1292–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1101738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Vicente M, Talloczy Z, Kaushik S, et al. Dopamine-modified alpha-synuclein blocks chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:777–788. doi: 10.1172/JCI32806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabuta T, Wada K. Aberrant interaction between Parkinson disease-associated mutant UCH-L1 and the lysosomal receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23731–22373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801918200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Martinez-Vicente M, Kruger U, et al. Tau fragmentation, aggregation and clearance: the dual role of lysosomal processing. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4153–4170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson LM, Aiken CT, Kaltenbach LS, et al. IKK phosphorylates Huntingtin and targets it for degradation by the proteasome and lysosome. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1083–1099. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Betarbet R, Sherer TB, Greenamyre JT. Ubiquitin-proteasome system and Parkinson’s diseases. Exp Neurol. 2005;191(Suppl. 1):S17–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarkar S, Ravikumar B, Floto RA, Rubinsztein DC. Rapamycin and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers ameliorate toxicity of polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin and related proteinopathies. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:46–56. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong ES, Tan JM, Soong WE, et al. Autophagy-mediated clearance of aggresomes is not a universal phenomenon. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2570–2582. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Brech A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamark T, Kirkin V, Dikic I, Johansen T. NBR1 and p62 as cargo receptors for selective autophagy of ubiquitinated targets. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1986–1990. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez-Vicente M, Talloczy Z, Wong E, et al. Cargo recognition failure is responsible for inefficient autophagy in Huntington’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:567–576. doi: 10.1038/nn.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu WH, Kumar A, Peterhoff C, et al. Autophagic vacuoles are enriched in amyloid precursor protein-secretase activities: implications for beta-amyloid peptide over-production and localization in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2531–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huibregtse JM. UPS shipping and handling. Cell. 2005;120:2–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henderson B, Henderson S. Unfolding the relationship between secreted molecular chaperones and macrophage activation states. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:329–341. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navon A, Ciechanover A. The 26 S proteasome: from basic mechanisms to drug targeting. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33713–33718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.018481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernales S, McDonald K, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1542–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawakami T, Inagi R, Takano H, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces autophagy in renal proximal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2665–2672. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, et al. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9220–9231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pallet N, Bouvier N, Legendre C, et al. Autophagy protects renal tubular cells against cyclosporine toxicity. Autophagy. 2008;4:783–791. doi: 10.4161/auto.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakaki K, Wu J, Kaufman RJ. Protein kinase Ctheta is required for autophagy in response to stress in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15370–15380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710209200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J, Ni M, Lee B, Barron E, Hinton DR, Lee AS. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP is required for endoplasmic reticulum integrity and stress-induced autophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1460–1471. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell. 2007;25:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Py BF, Boyce M, Yuan J. A critical role of eEF-2K in mediating autophagy in response to multiple cellular stresses. Autophagy. 2009;5:393–396. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hetz C, Thielen P, Matus S, et al. XBP-1 deficiency in the nervous system protects against amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by increasing autophagy. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2294–2306. doi: 10.1101/gad.1830709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benedetti C, Haynes CM, Yang Y, Harding HP, Ron D. Ubiquitin-like protein 5 positively regulates chaperone gene expression in the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Genetics. 2006;174:229–239. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haynes CM, Petrova K, Benedetti C, Yang Y, Ron D. ClpP mediates activation of a mitochondrial unfolded protein response in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2007;13:467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koga H, Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Altered lipid content inhibits autophagic vesicular fusion. FASEB J. 2010;24:3052–3065. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh R, Xiang Y, Wang Y, et al. Autophagy regulates adipose mass and differentiation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3329–3339. doi: 10.1172/JCI39228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y, Goldman S, Baerga R, Zhao Y, Komatsu M, Jin S. Adipose-specific deletion of autophagy-related gene 7 (atg7) in mice reveals a role in adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19860–19865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906048106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Obara K, Noda T, Niimi K, Ohsumi Y. Transport of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate into the vacuole via autophagic membranes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells. 2008;13:537–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nice DC, Sato TK, Stromhaug PE, Emr SD, Klionsky DJ. Cooperative binding of the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway proteins, Cvt13 and Cvt20, to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate at the pre-autophagosomal structure is required for selective autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30198–30207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204736200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nair U, Cao Y, Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. The roles of the lipid-binding motifs of Atg18 and Atg21 in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway and autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11476–11488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stromhaug PE, Reggiori F, Guan J, Wang CW, Klionsky DJ. Atg21 is a phosphoinositide binding protein required for efficient lipidation and localization of Atg8 during uptake of aminopeptidase I by selective autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3553–3566. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Obara K, Sekito T, Niimi K, Ohsumi Y. The Atg18-Atg2 complex is recruited to autophagic membranes via phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and exerts an essential function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23972–23980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803180200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y. Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simonsen A, Birkeland HC, Gillooly DJ, et al. Alfy, a novel FYVE-domain-containing protein associated with protein granules and autophagic membranes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4239–4251. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pankiv S, Alemu EA, Brech A, et al. FYCO1 is a Rab7 effector that binds to LC3 and PI3P to mediate microtubule plus end-directed vesicle transport. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:253–269. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ano Y, Hattori T, Oku M, et al. A sorting nexin PpAtg24 regulates vacuolar membrane dynamics during pexophagy via binding to phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:446–457. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vergne I, Roberts E, Elmaoued RA, et al. Control of autophagy initiation by phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase jumpy. EMBO J. 2009;28:2244–2258. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaushik S, Massey AC, Cuervo AM. Lysosome membrane lipid microdomains: novel regulators of chaperone-mediated autophagy. EMBO J. 2006;25:3921–3933. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kiffin R, Kaushik S, Zeng M, et al. Altered dynamics of the lysosomal receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy with age. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:782–791. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]