ABSTRACT

Bordetella pertussis causes pertussis, a respiratory disease that is most severe for infants. Vaccination was introduced in the 1950s, and in recent years, a resurgence of disease was observed worldwide, with significant mortality in infants. Possible causes for this include the switch from whole-cell vaccines (WCVs) to less effective acellular vaccines (ACVs), waning immunity, and pathogen adaptation. Pathogen adaptation is suggested by antigenic divergence between vaccine strains and circulating strains and by the emergence of strains with increased pertussis toxin production. We applied comparative genomics to a worldwide collection of 343 B. pertussis strains isolated between 1920 and 2010. The global phylogeny showed two deep branches; the largest of these contained 98% of all strains, and its expansion correlated temporally with the first descriptions of pertussis outbreaks in Europe in the 16th century. We found little evidence of recent geographical clustering of the strains within this lineage, suggesting rapid strain flow between countries. We observed that changes in genes encoding proteins implicated in protective immunity that are included in ACVs occurred after the introduction of WCVs but before the switch to ACVs. Furthermore, our analyses consistently suggested that virulence-associated genes and genes coding for surface-exposed proteins were involved in adaptation. However, many of the putative adaptive loci identified have a physiological role, and further studies of these loci may reveal less obvious ways in which B. pertussis and the host interact. This work provides insight into ways in which pathogens may adapt to vaccination and suggests ways to improve pertussis vaccines.

IMPORTANCE

Whooping cough is mainly caused by Bordetella pertussis, and current vaccines are targeted against this organism. Recently, there have been increasing outbreaks of whooping cough, even where vaccine coverage is high. Analysis of the genomes of 343 B. pertussis isolates from around the world over the last 100 years suggests that the organism has emerged within the last 500 years, consistent with historical records. We show that global transmission of new strains is very rapid and that the worldwide population of B. pertussis is evolving in response to vaccine introduction, potentially enabling vaccine escape.

INTRODUCTION

Bordetella pertussis is the primary causative agent of pertussis (whooping cough), a respiratory disease which is particularly severe for unvaccinated infants. Indeed, pertussis was a major cause of infant deaths before the introduction of vaccination. Even today, pertussis is a significant cause of child mortality, and estimates from the WHO suggest that, in 2008, about 16 million cases of pertussis occurred worldwide, 95% of which were in developing countries, and that about 195,000 children died from this disease (1).

There has been much speculation about the origin of pertussis. Although the disease has very characteristic symptoms and high mortality in unvaccinated children, references to pertussislike symptoms have not been found in the ancient European literature. The first documented pertussis epidemic occurred in Paris in 1578 (2). In the 16th and 17th centuries, descriptions of pertussis epidemics in Europe were documented more frequently in the literature, possibly suggesting an expansion of the disease (3). The apparent emergence of pertussis in Europe over the last 600 years may be due to import, as symptoms similar to pertussis were described in a classical Korean medical textbook from the 15th century (4).

The introduction of vaccination has significantly reduced the pertussis burden; however, in the 1990s, a resurgence of pertussis was observed in many highly vaccinated populations (5). The years 2010 to 2012 have seen particularly large outbreaks in Australia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States, with significant mortality in infants (6–10). The possible causes for the pertussis resurgence are still under debate and include waning vaccine-induced immunity, the switch from whole-cell vaccines (WCVs) to less effective acellular vaccines (ACVs), and pathogen adaptation (5, 11–13). The contributions of these causes probably differ from country to country. The importance of pathogen adaptation is suggested by the antigenic divergence of circulating strains from vaccine strains and the emergence of strains which produce more toxin (reviewed in reference 5). Antigenic divergence initially involved relatively few mutations, affecting up to 12 amino acids in the five B. pertussis proteins included in ACVs, i.e., filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin (Prn), the Ptx A subunit (PtxA), serotype 2 fimbriae (Fim2), and serotype 3 fimbriae (Fim3). In the 1980s, strains emerged with a novel allele for the Ptx promoter, designated ptxP3. Strains carrying the ptxP3 allele have been shown to produce more Ptx in vitro (14). Significantly, mutations in these six loci have been associated with clonal sweeps (15). The emergence of the ptxP3 lineage is particularly remarkable because ptxP3 strains have risen to predominance, replacing the resident ptxP1 strains in many European countries, the United States, and Australia (14, 16–21). Furthermore, the emergence of ptxP3 strains is associated with increases in pertussis notifications in at least two countries (14, 20). However, another study found that the resurgence of pertussis in the United States was correlated with the fim3-2 allele and not with ptxP3 (22). More recently, strains have emerged that do not express one or more components of pertussis vaccines, in particular, Prn and FHA (17, 23–25).

Together with at least 425 other genes, the genes for the five B. pertussis proteins used in ACVs belong to the so-called Bordetella virulence gene (Bvg) regulon, consisting of a sensory transduction system which translates environmental cues into changes in gene expression (26, 27). Low temperatures and high sulfate and nicotinic acid concentrations are signals known to suppress genes in the Bvg regulon (28). As essentially all known virulence-associated proteins require Bvg for their expression, Bvg activation is used to identify genes that play a role in the interaction with the host, even if the function of that gene is not known.

Key questions concerning pertussis are the origin of the disease, the forces that have driven the shifts in B. pertussis populations, and the role of these shifts in the resurgence of pertussis. To address these questions, we have determined the global population structure of B. pertussis by whole-genome sequencing of 343 strains from 19 countries isolated between 1920 and 2010. Phylogenetic analysis revealed a deep divergence between two lineages of B. pertussis, possibly suggesting two independent introductions of the organism from an unknown reservoir. Bayesian methods showed that the date of the common ancestor of one of these lineages correlates with the first descriptions of pertussis in Europe and that this lineage has increased in diversity subsequent to the introduction of vaccination. Our analyses revealed that many (putative) adaptive mutations occurred in the period in which the WCV was used, suggesting that vaccination was the major force driving changes in B. pertussis populations. Furthermore, we extend our previous observation that the mutation leading to the ptxP3 allele occurred once and that the ptxP3 strains have spread and diversified worldwide (29). Finally, we identified novel putative adaptive loci, the analysis of which may cast new light on the persistence and resurgence of pertussis and point to ways to increase the effectiveness of vaccination.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Phylogeny and phylogeography of B. pertussis.

We explored the evolutionary relationships among 343 B. pertussis strains collected from 19 countries representing six continents. Strains were isolated between 1920 and 2010 (Table 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Illumina reads were aligned to the reference genome B. pertussis Tohama I (30), and 5,414 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified (Table S2), corresponding to a mean SNP density of 0.0013 SNPs/bp and an estimated mutation rate of 2.24 × 10−7 per site per year. We generated a maximum likelihood phylogeny representing the B. pertussis global population structure (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). This phylogeny revealed two deep branches separated by 1,711 SNPs. Branch I contained only a small number of strains (1.7%), which were isolated between 1954 and 2000 and harbor ptxA5 and ptxP4 alleles (coding for the Ptx A subunit and the Ptx promoter, respectively), which are infrequently isolated nowadays. This branch includes the type strain 18323. Branch II contained strains isolated between 1920 and 2010 which fall into the more common ptxA2 ptxP1, ptxA1 ptxP1, and ptxA1 ptxP3 types (Fig. 1B). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis estimated that these two lineages diverged around 2,000 years ago (median, 2,296 years; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1,428 to 3,340), which may reflect the loss of intermediate lineages over time or may represent two independent introductions of B. pertussis into the global human population from an unknown reservoir. The adaptation of B. pertussis to the human population has been postulated to have involved a significant evolutionary bottleneck and was associated with considerable gene loss and gene inactivation due to insertion sequence (IS) element expansion and mutations (30), a process commonly seen in host-restricted bacteria (31). In the analysis of the Tohama I genome sequence, it was estimated that up to 25% of genes were lost relative to those present in the common ancestor with Bordetella parapertussis (30), and 9.5% of those remaining were inactivated and were only present as pseudogenes. A manual comparison of 50% of the pseudogenes in Tohama I and strain 18323 (representing the two deep branches) showed that 72% of the pseudogenes were shared, and of those, all had identical inactivating mutations (Table S3). This indicates that the host restriction of B. pertussis and the associated bottleneck occurred before the divergence of these two lineages and long before the first description of the disease. The most parsimonious explanation would suggest that this process involved adaptation to the human host, and this would indicate that pertussis was introduced into the global population twice from a reservoir in an unsampled human population or that the intermediate diversity has been lost. The alternative explanation, that the adaption was to another host, would require both an unknown reservoir species and two separate introductions into the human population.

TABLE 1 .

Geographic origin and period of isolation of B. pertussis strains used in this study

| Continent | Country | No. of strains | Isolation period | Introduction of vaccination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Kenya | 17 | 1975 | 1980s |

| Senegal | 4 | 1990-1993 | 1980s | |

| Asia | China | 2 | 1957 | Early 1960s |

| Hong Kong | 5 | 2002-2006 | 1950s | |

| Japan | 17 | 1988-2007 | 1950s | |

| Taiwan | 23 | 1992-2007 | 1954 | |

| Australia | Australia | 37 | 1974-2007 | 1953 |

| Europe | Denmark | 9 | 1962-2007 | 1961 |

| Finland | 16 | 1953-2006 | 1952 | |

| France | 11 | 1993-2007 | 1959 | |

| Italy | 15 | 1994-1995 | 1995 | |

| Netherlands | 60 | 1949-2010 | 1953 | |

| Poland | 16 | 1963-2000 | 1960 | |

| Russia | 2 | 2001-2002 | 1956-1959 | |

| Sweden | 23 | 1956-2006 | 1953 | |

| United Kingdom | 20 | 1920-2008 | 1957 | |

| North America | Canada | 17 | 1994-2005 | 1943 |

| USA | 36 | 1935-2005 | 1940s | |

| South America | Argentina | 13 | 1969-2008 | 1970s |

| Total | 343 | 1920-2010 |

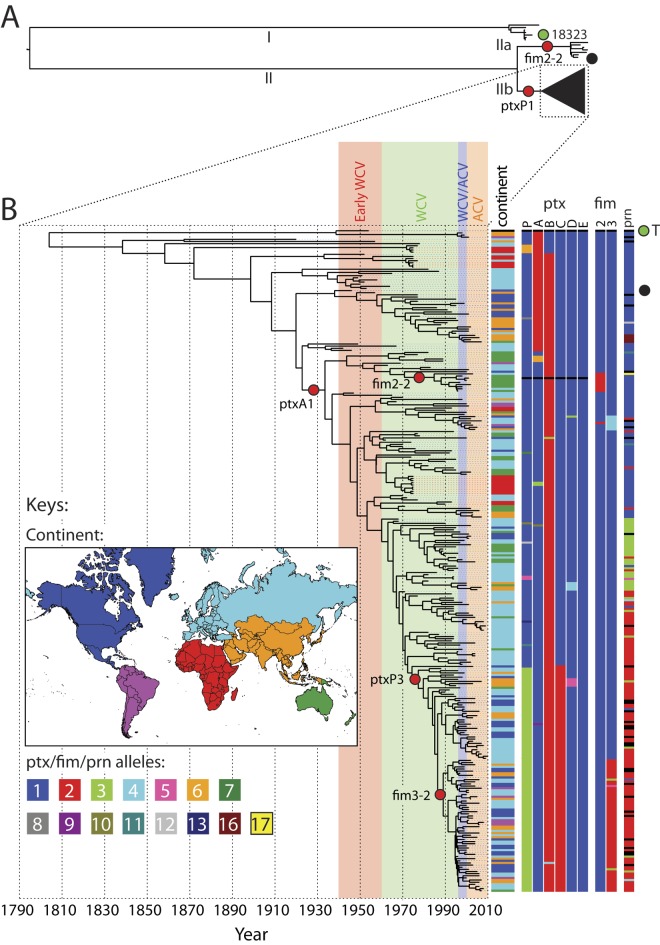

FIG 1 .

Global phylogeny of B. pertussis. (A) Outline of the maximum likelihood phylogeny of all B. pertussis samples sequenced, showing the deep divergence between lineages I and II. The complete tree is shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. (B) Bayesian phylogeny of samples for which date information was available within the most common clade of B. pertussis. The position of a node along the x axis of the tree represents the median date reconstructed for that node across all sampled trees. Dates of whole-cell vaccine (WCV) and acellular vaccine (ACV) periods are shown as background colors behind the tree. To the right of the tree, the continent of origin of isolates is indicated by the first column of horizontal bars, colored according to the inset key. The remaining nine columns represent loci within the ptx operon, the fim2 and fim3 loci, and the prn locus, with assigned numerical alleles colored according to the key. The positions of reference strains 18323 and Tohama I (T) are indicated in panels A and B with green filled circles. Black filled circles represent the American vaccine strains B308 (A) and B310 (B) (Table S1). Red circles indicate the major changes in antigen gene alleles in proteins used in current ACVs (from ptxA2 to ptxA1, fim2-1 to fim2-2, ptxP1 to ptxP3, and fim3-1 to fim3-2).

Three vaccine strains were included in this study, Tohama I and two American strains (strains B308 and B310) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which were placed in branch II. The vaccine strains and the reference genome, Tohama I, both represent lineages and antigenic genotypes for which recent isolations are rare. Most recent B. pertussis isolates stem from a lineage (lineage IIb) within branch II, which appeared before the introduction of vaccination but has expanded since. A Bayesian phylogenetic and skyline analysis of isolates from lineage IIb for which isolation date information was available (Fig. 1B; Fig. S2) reveals that there was no evidence of loss of diversity (represented by the effective population size) after the introduction of vaccination. This was unexpected, as one would assume that the introduction of vaccination would lead to a decrease in population diversity, as the selective pressure may lead to a population bottleneck whereby only those lineages that escape the vaccine may survive. Indeed, some previous studies have observed such a decrease in population diversity following the introduction of vaccination. However, these studies were based on geographically more restricted pathogen populations (32–34). Our results suggest that, despite whole-cell vaccines reducing the prevalence of many of the older lineages, they have not been eradicated completely, so the diversity of these lineages is still present in the B. pertussis population. The explanation for this may be that such lineages have persisted in geographical regions where vaccination has not become routine. In fact, there is some evidence from the skyline analysis that population diversity increased in lineage IIb after vaccine introduction. Although the effect of sampling density before and after vaccine introduction is unclear, the shape of the phylogenetic tree suggests that this increase was primarily the result of the expansion of the ptxA1 lineage, which may represent some level of vaccine escape in countries where vaccination had been introduced.

A second increase in effective population size (diversity) coincides with the emergence and expansion of a lineage carrying the ptxP3 allele. In the mid-1990s, there appears to be a drop in diversity, correlating with the loss of a number of early ptxA1 lineages, and perhaps corresponding with the introduction of the ACV in the mid-1990s. However, diversity very quickly increased again with the expansion of a sublineage of the ptxP3 group that acquired a fim3-2 allele, again suggesting the selection and diversification of vaccine escape lineages.

There is little evidence of geographical structure in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1B). The sampling of the older branch I lineages is sparse in space and time, making inference difficult. However, the ptxA1 lineage is clearly dispersed globally, and the ptxP3 and fim3-2 lineages show no geographical clustering at all, indicating that there has been very rapid global spread of these recently evolved lineages.

Temporal trends in frequencies of alleles coding for vaccine components.

To explore the influence of vaccination on the B. pertussis population, we focused on genes coding for antigens known to induce protection and included in modern ACVs, including serotype 2 fimbriae (fim2), serotype 3 fimbriae (fim3), pertactin (prn), and the A subunit of Ptx (ptxA) (5, 35). Although it is used in ACVs, filamentous hemagglutinin was not included, as accurate assembly and assignment of SNPs was not possible due to the presence of repeats and paralogs. As previous studies suggest that variation in the Ptx promoter, ptxP, was linked to clonal sweeps (15, 21, 33), we also included ptxP alleles in our analyses. With the exception of ptxA10, prn16, and prn17, all alleles have been described before, and references and accession numbers are given in Text S1 in the supplemental material. The major changes in antigen gene alleles (from ptxA2 to ptxA1, fim2-1 to fim2-2, ptxP1 to ptxP3, and fim3-1 to fim3-2) are marked on the nodes in the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1B. In most countries, vaccination was introduced between 1940 and 1960 (Table 1), and worldwide, many different B. pertussis strains have been used to produce vaccines. A compilation of 23 vaccine strains revealed that the most prevalent alleles found in vaccine strains were fim2-1 (82%), fim3-1 (100%), and prn1 (74%) or prn7 (22%) (Table S4). If one Dutch, one Swedish, and one acellular vaccine strain were omitted, all other vaccine strains carried the fim2-1, fim3-1, and prn1/7 alleles. More diversity in vaccine strains was observed with respect to ptxA, for which four alleles, ptxA1, ptxA2, ptxA3, and ptxA4, were observed at frequencies of 13%, 52%, 4%, and 31%, respectively. For twelve vaccine strains, the ptxP allele has been determined. The ptxP1 allele and ptxP2 allele were found in 67% and 33%, respectively. Most ACVs are derived from two strains, Tohama I and 10536, which carry the alleles fim2-1, fim3-1, prn1, ptxA2, and ptxP1 and fim2-1, fim3-1, prn7, ptxA4, and ptxP2, respectively.

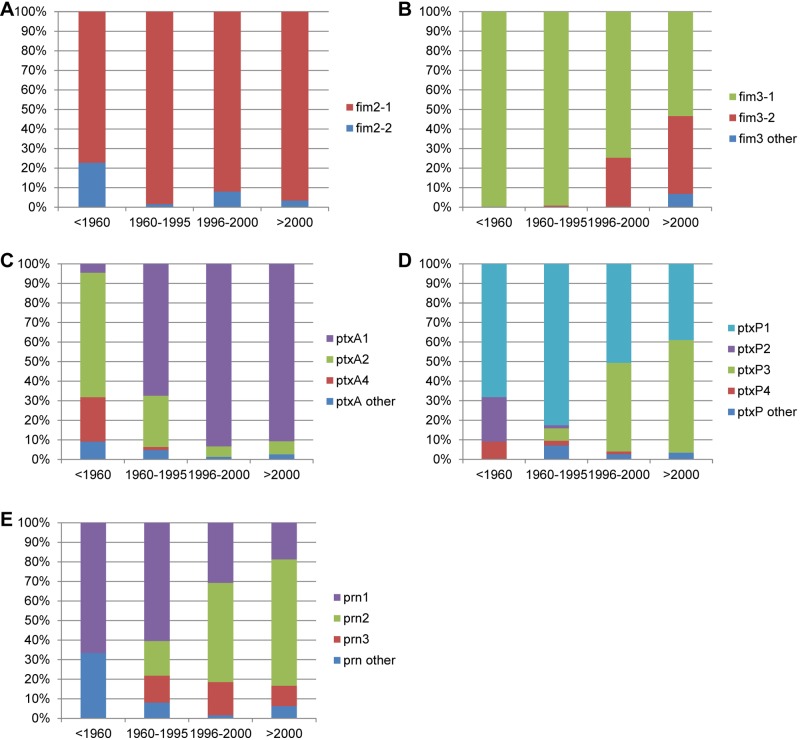

To investigate temporal trends in allele frequencies, we defined four periods to reflect the worldwide changes in pertussis vaccination (Fig. 2): the early WCV period (earlier than 1960; n = 22), the period in which mainly WCVs were used (WCV period, 1960 to 1995; n = 126), the period in which both WCVs and ACVs were used (WCV/ACV period, 1996 to 2000; n = 75), and finally, a period in which mainly ACVs were used (ACV period, later than 2000; n = 118). We presumed that the effect of vaccination on the B. pertussis population was small in the early WCV period (15, 33). Obviously, the relationship between the periods and the vaccination history can only be approximate.

FIG 2 .

Temporal trends in strain frequencies for the fim2 (A), fim3 (B), ptxA (C), ptxP (D), and prn (E) alleles. Four periods were defined to reflect the worldwide changes in pertussis vaccination, the early WCV period (earlier than 1960), the period in which mainly WCVs were used (WCV period, 1960 to 1995), the period in which both WCVs and ACVs were used (WCV/ACV period, 1996 to 2000), and a period in which mainly ACVs were used (ACV period, later than 2000).

Two fim2 alleles were observed in the worldwide collection of strains, fim2-1 (the vaccine type) and fim2-2, the products of which differed in a single amino acid. The fim2-1 allele predominated in all four periods (frequencies 77% to 98%), whereas the fim2-2 allele was found at low frequencies (2% to 23%) in all four periods (Fig. 2A). Phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1B) indicated that the mutation leading to the fim2-2 allele arose twice within lineage IIb but also occurred on the branch leading to lineage IIa. Bayesian analysis suggested that, within lineage IIb, the mutation occurred between 1970 and 1984 (95% CI, 1956 to 1992) on the first occasion and between 1996 and 2002 (95% CI, 1995 to 2002) on the second. Thus, the first mutation arose in the WCV period and the most recent mutation occurred in the WCV/ACV period.

More variation was found in fim3, for which five alleles were identified. As one allele contains a silent mutation, the five alleles code for four distinct proteins: Fim3-1, Fim3-2, Fim3-3, and Fim3-6. The fim3-1 (the vaccine type) and fim3-2 alleles were predominant (Fig. 2B). The polymorphic amino acid residue in fim3-2 relative to the sequence of fim3-1 is located in a surface epitope that has been shown to interact with human serum (36). The fim3-1 allele has always predominated, but the fim3-2 allele, which was first detected in the WCV period (frequency 1%), increased in frequency to 37% in the ACV period. Our analyses agreed with this observation, with the mutation resulting in the fim3-2 allele predicted to have occurred between 1986 and 1989 (95% CI, 1982 to 1992).

Eight ptxA alleles were found worldwide, two of which contained silent mutations. Thus, the eight alleles resulted in six protein variants (PtxA1, PtxA3, PtxA4, PtxA5, PtxA9, and PtxA10), mostly differing by one or two amino acids. Three alleles were predominant, ptxA1, ptxA2, and ptxA4 (respective frequencies, 78%, 18%, and 2%). The ptxA2 and ptxA4 alleles predominated in the early WCV period (respective frequencies, 64% and 23%). Our analyses show that the ptxA1 allele arose between 1921 and 1932 (95% CI, 1905 to 1942), before the introduction of vaccination. It increased in frequency from only 5% in the early WCV period to 68%, 92%, and 90% in subsequent periods (Fig. 2C). Although most (46%) of the vaccine strains harbor ptxA2, 17% do contain ptxA1.

Fourteen ptxP alleles were observed, of which ptxP1 and ptxP3 predominated (total frequencies of 60% and 32%, respectively). Strains with ptxP1 were most common in the early WCV and WCV periods (respective frequencies, 68% and 83%) but were replaced by ptxP3 strains in the last two periods (the ptxP3 frequencies in the WCV/ACV and ACV periods were 48% and 57%, respectively) (Fig. 2D). Bayesian analysis suggested that the mutation resulting in the ptxP3 allele arose between 1974 and 1977 (95% CI, 1970 to 1981), i.e., in the WCV period.

Twelve prn alleles were identified, of which 11 led to protein variants (Prn1 to -7, Prn10 to -12, and Prn16). Prn-deficient strains were not detected, presumably because these strains reached significant frequencies in a later period than analyzed in this study. Three alleles predominated in our worldwide collection, prn1 (42%), prn2 (38%), and prn3 (12%). In the early WCV period, 67% of the strains harbored prn1 (the vaccine type), with prn2 and prn3 alleles emerging in the WCV period. While the frequency of the prn3 allele remained more or less constant (10% to 17%), prn2 increased in frequency from 18% in the WCV period to 65% in the ACV period (Fig. 2E). Variation in prn mainly occurs by variation in numbers of repeats, a reversible process which is relatively frequent compared to point mutations. Therefore, many prn variants were homoplasic in our tree due to convergent evolution.

In conclusion, based on these five genes, it appears that the worldwide B. pertussis population has changed significantly in the last 60 years, consistent with other studies using temporally and geographically less diverse collections (15, 17–19, 21, 22, 32, 34, 37–40). Most changes resulted in genetic divergence from vaccine strains, consistent with vaccine-driven immune selection. Indeed, Bayesian analyses suggested that the non-vaccine-type alleles ptxP3 and fim3-2 arose in the period in which the WCV was used widely. Recently, strains have been identified which do not express Prn and/or FHA (17, 23, 24), and the emergence of these strains may be associated with the introduction of ACVs. In this and previous work, the largest number of alleles were observed for ptxP (n = 14), prn (n = 12), and ptxA (n = 8). The number of alleles may be related to the degree of diversifying selection caused, e.g., by the immune status of the host population or other (frequent) changes in the ecology of B. pertussis.

Previous studies have shown that changes in fim3, ptxA, prn, and ptxP are associated with selective sweeps (15, 19, 22, 32), implying a significant effect on strain fitness. Furthermore, variation in ptxA, ptxP, and prn has been shown to affect bacterial colonization of naive and vaccinated mice (40–45), underlining the biological significance of these changes. However, in one study, the effects were not observed (46).

Identification of additional loci potentially involved in adaptation.

In addition to focusing on genes coding for vaccine components, we used a more comprehensive approach to identify putative adaptive loci. To detect genes important for adaptation, dN/dS ratios (ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates) are widely used. This method was originally developed for the analysis of divergent species and needs a large number of substitutions for a statistically reliable analysis (47–49). However, B. pertussis strains are highly related and differ by less than 0.1% in their genomic sequences. Recent studies have shown that the primary driver of dN/dS ratios in such closely related strains is time, not selection (48). Furthermore, the approach using dN/dS ratios assumes that silent mutations are neutral. However, silent mutations in genes can significantly affect gene expression (50). Finally, dN/dS ratios are not useful to detect diversifying selection in intergenic regions. Therefore, we chose to assess diversifying selection by focusing on SNP densities and homoplasy.

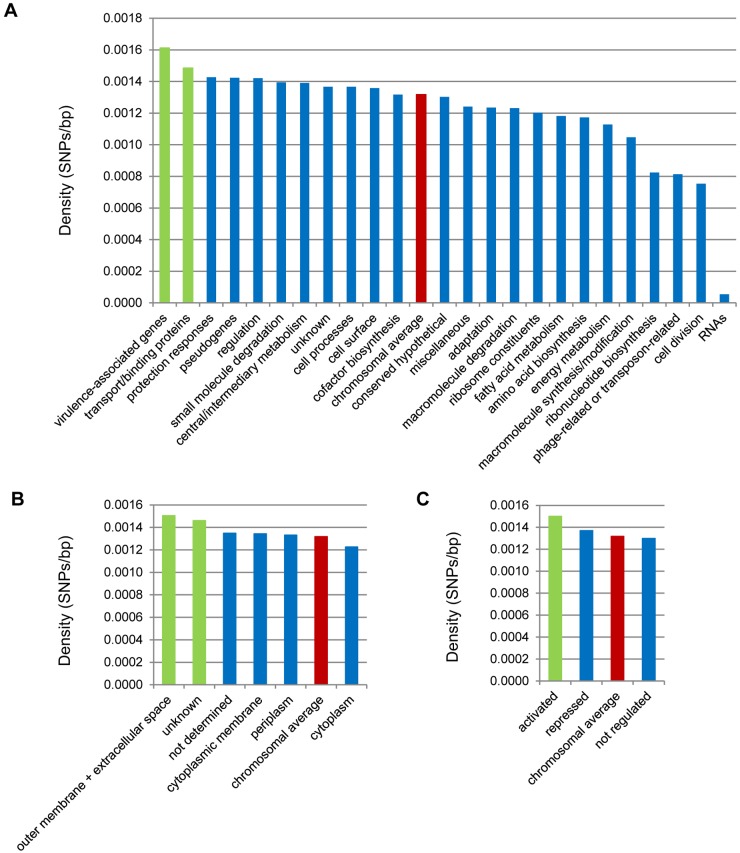

SNP densities. We explored whether particular gene categories had a significantly higher SNP density than the overall SNP density of the whole genome, 0.0013 SNPs/bp. The gene categories used were defined by Parkhill et al. (30), with modifications, i.e., pseudogenes and genes known or assumed to be associated with virulence were placed in separate categories. In all, 24 gene categories were defined (Fig. 3A; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). As expected, gene categories involved in housekeeping functions, which are generally conserved, showed the lowest SNP densities (0.0007 to 0.00012 SNPs/bp). The four categories with the highest SNP density were virulence associated (0.0016 SNPs/bp), transport/binding (0.0015 SNPs/bp), protection responses (0.0014 SNPs/bp), and pseudogenes (0.0014 SNPs/bp), which are likely to be evolving neutrally since their inactivation. Only for the virulence-associated and transport/binding categories did the SNP density difference reach statistical significance, however (P = 0.02 and P = 0.03, respectively). The high SNP density in the transport/binding category was surprising, as this category mostly codes for housekeeping functions, including transport of molecules such as amino acids, small ions, and carbohydrates. The high SNP density may reflect changes in the physiology of B. pertussis or the surface exposure of membrane and periplasmic components of these systems.

FIG 3 .

SNP densities per functional category (A), subcellular localization (B), and Bvg regulation (C). Red bars indicate the chromosomal average. Green bars refer to categories with an SNP density significantly higher than the chromosomal average (P < 0.05).

To investigate this further, we tested whether the subcellular location of proteins would result in significantly different degrees of SNP density, as surface-exposed proteins are expected to be subject to a higher degree of immune selection than intracellular proteins. In line with this, we found that if categories were based on subcellular location prediction, genes coding for proteins exposed to the host environment (extracellular and outer membrane proteins) had the highest SNP density (0.0015 SNPs/bp; P = 0.05), whereas genes coding for cytoplasmic proteins showed the lowest SNP density (0.0012 SNPs/bp; P = 1.0) (Fig. 3B; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). In addition to the exposed category, only the category “unknown,” which comprises proteins for which we could not predict a location, showed an SNP density which was significantly higher than the genomic average (0.0015 SNPs/bp; P = 0.007). For example, Ptx subunits 2 to 5 are included in the unknown category, although it is known that they are secreted (51). Possibly this category compromises more genes that encode surface-exposed proteins but for which the location could not be predicted.

We also assessed the SNP density in gene categories based on Bvg regulation (26, 27). For this, three categories were defined: genes activated, repressed, or unaffected by Bvg (Fig. 3C; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). The SNP density in these three categories decreased in the order Bvg activated, Bvg repressed, and not regulated by Bvg (SNP densities, 0.0015, 0.0014, and 0.0013 SNPs/bp, respectively; P = 0.013, P = 0.40, and P = 1.0, respectively). The relatively high SNP density in Bvg-activated genes was not unexpected, as genes encoding virulence-associated proteins and extracellular proteins are included in this category.

Focusing on gene categories increased the power of the statistical analyses but only gave a general picture and did not reveal individual loci that might be under selection. Therefore, we also identified particular loci which were highly polymorphic. For this, we calculated whether there was an overrepresentation of SNPs in a locus given its length (Table 2; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). Two genes showed a significantly higher SNP density than the chromosomal average of 0.0013 SNPs/bp in genes. One gene encodes Ptx subunit A (ptxA) (0.011 SNPs/bp; P = 0.0033). The other gene, cysB (0.011 SNPs/bp; P = 0.0029), encodes a LysR-like transcriptional regulator that acts as an activator of the cys genes and plays a role in sulfur metabolism (52, 53).

TABLE 2 .

Genes and promoters with SNP densities significantly higher than the chromosomal average

| Locus tag(s) | Gene(s) | Density (SNPs/bp) | P value | Product | Categorya | Localization(s)b | Bvgc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3783BP | ptxA | 0.01111 | 3.3E-03 | Pertussis toxin subunit A precursor | Vir | E | + |

| 2416BP | cysB | 0.01053 | 2.9E-03 | LysR family transcriptional regulator | Reg | C | |

| BP3783P | ptxP | 0.07143 | 4.7E-18 | Pertussis toxin promoter | Vir | E | + |

| BP2936P | 0.03623 | 2.0E-02 | Putative methylase promoter | Exp | CM | + | |

| BP1878P, BP1879P |

bvgP, fhaBP |

0.02582 | 3.4E-05 | Virulence factor transcription regulator promoter, filamentous hemagglutinin | Vir | C, OM | +, + |

| BP3723P, BP3724P |

0.02047 | 1.8E-02 | Hypothetical protein promoter | Hyp | U, C |

Functional category: Vir, virulence-associated genes; Reg, regulation; Exp, exported proteins; Hyp, hypothetical proteins.

Subcellular localization: E, extracellular; C, cytoplasmic; CM, cytoplasmic membrane; OM, outer membrane; U, unknown.

Regulation by Bvg: +, activated; blank cells, not activated or repressed.

We also investigated SNP densities in intergenic regions, as these may be involved in transcription of downstream genes. We found four putative promoter regions with a significantly higher SNP density than the chromosomal average of 0.0026 SNPs/bp in intergenic regions (Table 2; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). Two promoter regions were located upstream from virulence-associated genes. One was upstream from the ptx operon (0.071 SNPs/bp; P = 4.7 × 10−18), and one was between the filamentous hemagglutinin gene (fhaB) and the bvg operon (0.026 SNPs/bp; P = 3.4 × 10−5). The extensive polymorphism in the Ptx promoter has been described previously (14, 16). Eleven SNPs were located in the intergenic region between the bvg operon and fhaB, which has been studied extensively (54–58). Seven and four SNPs were located in regions assumed to affect the transcription of fhaB and bvgA, respectively (Text S2). While the SNPs in the fhaB promoter may affect the expression of both fha and fim genes, which are part of a single operon (59), the SNPs in the bvgA promoter region may have a significant effect on the expression of many virulence factors. A high SNP density was also observed in the region upstream from a putative methylase possibly involved in ubiquinone/menaquinone biosynthesis (0.036 SNPs/bp; P = 0.020) and in the promoter region of two hypothetical proteins (0.020 SNPs/bp; P = 0.018).

In conclusion, we identified significantly higher SNP densities in virulence-associated genes, genes encoding surface-exposed proteins, and genes activated by Bvg. High SNP densities were also observed in the promoter regions for ptx and bvg/fha. The finding of a high SNP density in cysB was interesting, as a number of associations have been observed between sulfur metabolism and virulence (60). Indeed, in B. pertussis, the expression of virulence-associated genes is affected by the sulfate concentration (28). The identification of putative adaptive loci allows focused studies that may reveal novel strategies for pathogen adaptation.

Homoplasic SNPs.

In a second approach to find loci possibly involved in adaptation, we identified homoplasic SNPs, that is, SNPs which arose independently on different branches of the tree. In our data set, 15 SNPs were homoplasic (Table 3). Thirty-three percent of the homoplasic SNPs were located in Bvg-activated genes, while this category only comprises 6% of the genome. The 5 SNPs found in Bvg-activated genes were located in genes for the serotype 2 and 3 fimbrial subunits (fim2 and fim3), a type III secretion protein (bscI), a Ptx transport protein (ptlB), and a periplasmic solute-binding protein (smoM) involved in transport of mannitol. Of the remaining 10 homoplasic SNPs, 6 and 4 were located in genes and intergenic regions, respectively. Remarkably, one homoplasic SNP found in cysM was observed in five branches. The cysM gene codes for cysteine synthase, which is involved in cysteine biosynthesis and sulfate assimilation. All other homoplasic SNPs occurred in two branches.

TABLE 3 .

Homoplasic SNPs

| Positiona | Locus tag(s) | Gene | Branchesb | Bootstrapc | Changed | Product (distance to ATG in bp) |

Functional category | Localizatione | Bvgf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 612075 | BP0607 | gpm | 2 (1, 3) | 99 | Silent | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 |

Energy metabolism | Cytoplasmic | |

| 667028 | BP0658 | 2 (1, 19) | 55 | Q30 | Putative dehydrogenase | Miscellaneous | Cytoplasmic | ||

| 925864 | BP0888 | 2 (7, 1) | 100 | Silent | GntR family transcriptional regulator |

Regulation | Cytoplasmic | ||

| 997017 | BP0958 | cysM | 5 (1, 1, 4, 2, 1) | 100 | G247E | Cysteine synthase B | Amino acid biosynthesis |

Cytoplasmic | |

| 1109310 | 1064BP | maeB | 2 (6, 1) | 100 | Silent | NADP-dependent malic enzyme |

Central/intermediary metabolism |

Cytoplasmic | |

| 1109312 | 1064BP | maeB | 2 (6, 1) | 100 | Q28P | NADP-dependent malic enzyme |

Central/intermediary metabolism |

Cytoplasmic | |

| 1175956 | 1119BP | fim2 | 2 (7, 9) | 100 | R177K | Serotype 2 fimbrial subunit precursor |

Virulence- associated genes |

Extracellular | + |

| 1565529 | 1487BP | smoM | 2 (1, 4) | 100 | R176K | Putative periplasmic solute-binding protein |

Transport/binding proteins |

Unknown | + |

| 1647989 | 1568BP | fim3 | 2 (1, 1) | 98 | T130A | Serotype 3 fimbrial subunit precursor |

Virulence- associated genes |

Extracellular | + |

| 2018882 | BP1914P | 2 (1, 2) | 100 | Intergenic | Transposase for IS1663 (321) |

Phage or transposon related |

Unknown | ||

| BP1915P | 2 (1, 2) | 100 | Intergenic | Conserved hypothetical protein (23) |

Conserved hypothetical |

Unknown | |||

| 2213448 | BP2090P | 2 (8, 1) | 100 | Intergenic | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein (306) |

Transport/binding proteins |

Periplasmic | − | |

| BP2091P | 2 (8, 1) | 100 | Intergenic | Dioxygenase hydroxylase component (53) |

Small molecule degradation |

Cytoplasmic | − | ||

| 2374322 | 2249BP | bscI | 2 (1, 97) | 60 | Y114C | Type III secretion protein | Virulence- associated genes |

Unknown | + |

| 3041105 | BP2862P | 2 (6, 1) | 100 | Intergenic | Conserved hypothetical protein (174) |

Unknown | Unknown | ||

| BP2863P | 2 (6, 1) | 100 | Intergenic | Conserved hypothetical protein (148) |

Unknown | Cytoplasmic | |||

| 3251279 | BP3052P | 2 (6, 2) | 100 | Intergenic | Putative gamma- glutamyl transpeptidase (242) |

Miscellaneous | Periplasmic | ||

| 3992064 | 3789BP | ptlB | 2 (1, 1) | 69 | Silent | Pertussis toxin transport protein |

Virulence- associated genes |

CM | + |

Position in reference genome B. pertussis Tohama I.

Number of branches in which the homoplasic SNP occurred (number of strains/branch).

Number of trees in which SNP is homoplasic (100 trees tested).

Change in amino acid.

Subcellular localization: CM, cytoplasmic membrane.

Regulation by Bvg: + activated; − repressed; blank cells, not activated or repressed.

Convergent evolution is extremely rare in monomorphic bacteria like B. pertussis. In other monomorphic bacteria, homoplasy is usually only found in a few genes involved in antibiotic resistance (61). This suggests that the homoplasic SNPs we have identified may play an important role in the adaptation of B. pertussis.

Gene loss.

Several studies have shown that some B. pertussis isolates contain DNA that is not in Tohama but is present in Bordetella bronchiseptica and Bordetella parapertussis (62–66). In this work, we performed a de novo assembly of all of the genomes and compared each assembly back against the reference Tohama I in order to identify any genomic DNA that may have been acquired since the origin of B. pertussis. This analysis showed no evidence of gene gain at any point in the phylogeny. All regions identified in the sample data set that were not in Tohama are present in other Bordetella pertussis genomes, such as 18323, consistent with gene loss in Tohama. Placing these regions onto the tree showed that progressive gene loss within multiple lineages can be observed (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

Summary.

With the determination of the global population structure of B. pertussis using whole-genome sequencing, we addressed key questions concerning the origin of pertussis, such as the forces that have driven the shifts in B. pertussis populations and the role of these shifts in the resurgence of pertussis. Despite a structure suggesting two relatively recent introductions of B. pertussis from an unknown reservoir, phylogenetic analysis did not reveal the ancient geographic origin of B. pertussis, possibly because rapid worldwide spread and selective sweeps have eliminated geographic signatures. Indeed, our results showed that the mutation that resulted in the ptxP3 allele, which is associated with an increase in pertussis notifications in at least two countries (14, 20), occurred once and strains carrying this new allele spread worldwide in 25 to 30 years.

We confirmed and extended the observation that the worldwide B. pertussis population has changed significantly in the last 60 years, consistent with other studies using temporally and geographically less diverse collections (15, 17–19, 21, 32, 34, 37–40). We used several approaches to identify gene categories under selection, including SNP density and homoplasy. These approaches consistently suggested that Bvg-activated genes and genes coding for surface-exposed proteins were important for adaptation. At the individual gene level, four of the five genes for the components of current ACVs were found to be particularly variable, underlining their role in inducing protective immunity and consistent with vaccine-driven immune selection.

We identified other, less obvious genes which contained potentially adaptive mutations, such as two genes involved in cysteine and sulfate metabolism (cysB and cysM). Sulfate can be used to regulate virulence-associated genes in vitro (67), and our results suggest that sulfate may also be an important cue during natural infection. This result suggests that host-pathogen signaling and/or the physiology of B. pertussis has changed over time.

Temporal analyses showed that most mutations in genes encoding acellular vaccine components arose in the period in which the WCV was used. It should be noted, however, that the period in which the WCV was used (30 to 40 years) is much longer than the ACV period (7 to 15 years). These results are consistent with a significant effect of vaccination on the B. pertussis population, as suggested by previous studies (5, 20, 32, 39, 68). It seems plausible that the changes in the B. pertussis populations have reduced vaccine efficacy.

Pathogen adaptations may reveal weak spots in the bacterial defense, and hence, the loci under selective pressure may point to ways to improve pertussis vaccines. Furthermore, many of the putative adaptive loci we identified have a physiological role, and future studies of these loci may reveal less obvious ways in which the pathogen and host interact.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and sequencing.

The clinical isolates used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. DNA was isolated by the participants and sequenced using Illumina technology (69). Nineteen isolates were sequenced using the Genome Analyzer II and resulting in single reads of 37 bp (sequencing method 1). Thirty-eight isolates were sequenced using the Genome Analyzer II and resulting in paired-end reads of 50 bp (sequencing method 2). The remaining isolates were sequenced using 12 multiplexed tags on the Genome Analyzer II, producing paired-end reads of 54 bp (sequencing method 3). The accession numbers of the raw sequence data are listed in Table S1.

SNP detection.

Reads for all sequenced samples were mapped against the complete Tohama I reference genome sequence (accession number BX470248) using SMALT (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/smalt/). Reads mapping with identical matches to two regions of the reference genome were left unmapped. The alignment of reads around insertions and deletions (indels) was improved using a combination of pindel (70) to identify short indels and dindel (71) to realign the reads. SNPs were identified using samtools mpileup (http://samtools.sourceforge.net) and filtered as described previously (72)

Information about promoters, genes, and proteins was retrieved from the sequenced genome of B. pertussis Tohama I. The annotation was updated using BLAST (73), and domain information was recovered from SMART (74) and Conserved Domain Database (75).

Homoplasic SNPs were identified by reconstructing base changes for each variable site onto the phylogenetic tree under the parsimony criterion. Any site for which the observed number of base changes for the maximum parsimony reconstruction on the tree was greater than the minimum possible number of changes for that site is homoplasic.

Phylogeny.

The phylogenetic relationships of the entire data set were inferred under a maximum likelihood framework using PHYML (76) with an HKY85 model of evolution. The global phylogeny was rooted using B. bronchiseptica MO149 (sequence type 15 [ST15]), which was previously shown to be most closely related to B. pertussis (77, 78).

Mutation rates and ancestral node dates for lineage IIb were estimated using Bayesian analysis in the BEAST version 1.6.2 package (79). Analyses using the variable sites within lineage IIb isolates with isolation dates available were run under a general time reversible (GTR) model of evolution, with all combinations of constant, expansion, logistic and skyline population size models, and strict, relaxed exponential, and relaxed log-normal clock models. For each combination, three independent Markov chains were run for 100 million generations each, with parameter values sampled every 1,000 generations. Chains were manually checked for reasonable ESS values and for convergence between the three replicate chains using Tracer. Tracer was also used to identify a suitable burn-in period to remove from the beginning of each chain, as well as to assess the model with the best fit to the data using Bayes factors. A skyline population model with a relaxed exponential clock model was identified as the most appropriate, so this combination of models was used for all further analyses. It was found that, in each case, a burn-in of 10 million generations was clearly past the point where chains appeared to have converged, so this was chosen as the burn-in for all chains. The burn-in was removed and chains combined and down-sampled to every 10,000 generations using LogCombiner. A Bayesian skyline plot was calculated in Tracer using the default parameters, and a maximum clade credibility tree computed with TreeAnnotator.

SNP densities.

The functional categories used were defined by Parkhill et al. (30), with modifications, i.e., pseudogenes and genes known or assumed to be associated with virulence were placed in separate categories. Subcellular localization was predicted by PSORTb version 3.0 (80). Bvg categories were defined based on the results of Streefland et al. (27) and Cummings et al. (26). For the length of a specific category or locus repeat, regions were excluded because SNPs in these regions are not reliable. To determine the number of bases in a specific category, the lengths of the included loci were added, excluding repeat regions. To determine whether the SNP density of a particular group or locus was significantly higher than the chromosomal average, Fisher’s exact test was used. P values were corrected according to the method of Benjamini and Hochberg (81).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Characteristics of 343 B. pertussis strains used in this study.

List of SNPs identified in this study.

Pseudogenes shared by Tohama and 18323.

Overview of strains used for production of pertussis vaccines.

SNP densities per functional category, subcellular location, Bvg regulation, gene, and intergenic region.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of all isolates included in this study (see Table S1). (A) The complete tree of all isolates rooted on a ST15 B. bronchiseptica isolate, strain MO149. The branch leading to MO149 has been shortened to allow the relationships within B. pertussis to be seen. (B) A zoomed view of the maximum likelihood tree of lineage II to allow the relationships in this lineage to be more clearly seen. Scale bars indicate numbers of SNPs. Download

Bayesian skyline plot of B. pertussis illustrating variation in effective population size of lineage IIb over time. Download

Gene loss in B. pertussis isolates compared to Tohama I (A) and the distribution of accessory contigs not present in Tohama I (B). Download

Overview of alleles coding for antigens known to induce protection and included in modern acellular pertussis vaccines. Download

Polymorphisms in the bvgA and fhaB promoter region. Download

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This effort was initiated during the Bordetella Workshop in Cambridge on 22 to 24 July 2008. Therefore, we are very grateful to the attendees and especially to Olivier Restif, who organized this meeting. We thank Gwendolyn L. Gilbert (Westmead Hospital, Australia) and Margaret Ip (the Chinese University of Hong Kong) for supplying strains.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 098051), the RIVM (SOR project S/230446/01/BV), and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Citation Bart MJ, Harris SR, Advani A, Arakawa Y, Bottero D, Bouchez V, Cassiday PK, Chiang C-S, Dalby T, Fry NK, Gaillard ME, van Gent M, Guiso N, Hallander HO, Harvill ET, He Q, van der Heide HGJ, Heuvelman K, Hozbor DF, Kamachi K, Karataev GI, Lan R, Lutyńska A, Maharjan RP, Mertsola J, Miyamura T, Octavia S, Preston A, Quail MA, Sintchenko V, Stefanelli P, Tondella ML, Tsang RSW, Xu Y, Yao S-M, Zhang S, Parkhill J, Mooi FR. 2014. Global population structure and evolution of Bordetella pertussis and their relationship with vaccination. mBio 5(2):e01074-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01074-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, Jha P, Campbell H, Walker CF, Cibulskis R, Eisele T, Liu L, Mathers C, Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF 2010. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 375:1969–1987. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Still GF. 1965. The history of paediatrics. Oxford University Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lapin JH. 1943. Whooping cough. Charles C. Thomas Publisher Ltd., Springfield, IL [Google Scholar]

- 4. Magner LN. 1993. Diseases of the premodern period in Korea, p 392–400 In Kiple KF, The Cambridge world history of human disease. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mooi FR. 2010. Bordetella pertussis and vaccination: the persistence of a genetically monomorphic pathogen. Infect. Genet. Evol. 10:36–49. 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spokes PJ, Quinn HE, McAnulty JM. 2010. Review of the 2008-2009 pertussis epidemic in NSW: notifications and hospitalisations. N. S. W. Public Health Bull. 21:167–173. 10.1071/NB10031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Health Protection Agency 25 October 2012. Health protection report. Vol 6 No 43. Health Protection Agency, London England: http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2012/hpr4312.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conyn van Spaendock M, Van der Maas N, Mooi F. 2013. Control of whooping cough in the Netherlands: optimisation of the vaccination policy. RIVM letter report 215121002. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, The Netherlands. http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/215121002.pdf

- 9. Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Schechter R, Talarico J, Watt J, Chavez G. 2012. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J. Pediatr. 161:1091–1096. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeBolt C, Tasslimi A, Bardi J, Leader B, Hiatt B, Quin X, Patel M, Martin S, Tondella ML, Cassiday P, Faulkner A, Messonnier NE, Clark TA, Meyer S. 2012. Pertussis epidemic—Washington, 2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 61:517–522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klein NP, Bartlett J, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Fireman B, Baxter R. 2012. Waning protection after fifth dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 367:1012–1019. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sheridan SL, Ware RS, Grimwood K, Lambert SB. 2012. Number and order of whole cell pertussis vaccines in infancy and disease protection. JAMA 308:454–456. 10.1001/jama.2012.6364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Misegades LK, Winter K, Harriman K, Talarico J, Messonnier NE, Clark TA, Martin SW. 2012. Association of childhood pertussis with receipt of 5 doses of pertussis vaccine by time since last vaccine dose, California, 2010. JAMA 308:2126–2132. 10.1001/jama.2012.14939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mooi FR, van Loo IH, van Gent M, He Q, Bart MJ, Heuvelman KJ, de Greeff SC, Diavatopoulos D, Teunis P, Nagelkerke N, Mertsola J. 2009. Bordetella pertussis strains with increased toxin production associated with pertussis resurgence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1206–1213. 10.3201/eid1508.081511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Gent M, Bart MJ, van der Heide HG, Heuvelman KJ, Mooi FR. 2012. Small mutations in Bordetella pertussis are associated with selective sweeps. PLoS One 7:e46407. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Advani A, Gustafsson L, Ahrén C, Mooi FR, Hallander HO. 2011. Appearance of Fim3 and ptxP3-Bordetella pertussis strains, in two regions of Sweden with different vaccination programs. Vaccine 29:3438–3442. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hegerle N, Paris AS, Brun D, Dore G, Njamkepo E, Guillot S, Guiso N. 2012. Evolution of French Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis isolates: increase of bordetellae not expressing pertactin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:E340–E346. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03925.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kallonen T, Mertsola J, Mooi FR, He Q. 2012. Rapid detection of the recently emerged Bordetella pertussis strains with the ptxP3 pertussis toxin promoter allele by real-time PCR. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:E377–E379. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.04000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lam C, Octavia S, Bahrame Z, Sintchenko V, Gilbert GL, Lan R. 2012. Selection and emergence of pertussis toxin promoter ptxP3 allele in the evolution of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 12:492–495. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Octavia S, Sintchenko V, Gilbert GL, Lawrence A, Keil AD, Hogg G, Lan R. 2012. Newly emerging clones of Bordetella pertussis carrying prn2 and ptxP3 alleles implicated in Australian pertussis epidemic in 2008-2010. J. Infect. Dis. 205:1220–1224. 10.1093/infdis/jis178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petersen RF, Dalby T, Dragsted DM, Mooi F, Lambertsen L. 2012. Temporal trends in Bordetella pertussis populations, Denmark, 1949-2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:767–774. 10.3201/eid1805.110812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmidtke AJ, Boney KO, Martin SW, Skoff TH, Tondella ML, Tatti KM. 2012. Population diversity among Bordetella pertussis isolates, United States, 1935-2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:1248–1255. 10.3201/eid1808.120082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barkoff AM, Mertsola J, Guillot S, Guiso N, Berbers G, He Q. 2012. Appearance of Bordetella pertussis strains not expressing the vaccine antigen pertactin in Finland. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 19:1703–1704. 10.1128/CVI.00367-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Otsuka N, Han HJ, Toyoizumi-Ajisaka H, Nakamura Y, Arakawa Y, Shibayama K, Kamachi K. 2012. Prevalence and genetic characterization of pertactin-deficient Bordetella pertussis in Japan. PLoS One 7:e31985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Queenan AM, Cassiday PK, Evangelista A. 2013. Pertactin-negative variants of Bordetella pertussis in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 368:583-584. 10.1056/NEJMc1209369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cummings CA, Bootsma HJ, Relman DA, Miller JF. 2006. Species- and strain-specific control of a complex, flexible regulon by Bordetella BvgAS. J. Bacteriol. 188:1775–1785. 10.1128/JB.188.5.1775-1785.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Streefland M, van de Waterbeemd B, Happé H, van der Pol LA, Beuvery EC, Tramper J, Martens DE. 2007. PAT for vaccines: the first stage of PAT implementation for development of a well-defined whole-cell vaccine against whooping cough disease. Vaccine 25:2994–3000. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stibitz S. 2007. The bvg regulon, p 47–67 In Locht C, Bordetella molecular microbiology. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Gent M, Bart MJ, van der Heide HG, Heuvelman KJ, Kallonen T, He Q, Mertsola J, Advani A, Hallander HO, Janssens K, Hermans PW, Mooi FR. 2011. SNP-based typing: a useful tool to study Bordetella pertussis populations. PLoS One 6:e20340. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parkhill J, Sebaihia M, Preston A, Murphy LD, Thomson N, Harris DE, Holden MT, Churcher CM, Bentley SD, Mungall KL, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Temple L, James K, Harris B, Quail MA, Achtman M, Atkin R, Baker S, Basham D, Bason N, Cherevach I, Chillingworth T, Collins M, Cronin A, Davis P, Doggett J, Feltwell T, Goble A, Hamlin N, Hauser H, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Leather S, Moule S, Norberczak H, O’Neil S, Ormond D, Price C, Rabbinowitsch E, Rutter S, Sanders M, Saunders D, Seeger K, Sharp S, Simmonds M, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Stevens K, Unwin L, Whitehead S, Barrell BG, Maskell DJ. 2003. Comparative analysis of the genome sequences of Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Nat. Genet. 35:32–40. 10.1038/ng1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moran NA, Plague GR. 2004. Genomic changes following host restriction in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14:627–633. 10.1016/j.gde.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Litt DJ, Neal SE, Fry NK. 2009. Changes in genetic diversity of the Bordetella pertussis population in the United Kingdom between 1920 and 2006 reflect vaccination coverage and emergence of a single dominant clonal type. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:680–688. 10.1128/JCM.01838-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van Loo IH, Mooi FR. 2002. Changes in the Dutch Bordetella pertussis population in the first 20 years after the introduction of whole-cell vaccines. Microbiology 148:2011–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weber C, Boursaux-Eude C, Coralie G, Caro V, Guiso N. 2001. Polymorphism of Bordetella pertussis isolates circulating for the last 10 years in France, where a single effective whole-cell vaccine has been used for more than 30 years. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4396–4403. 10.1128/JCM.39.12.4396-4403.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berbers GA, de Greeff SC, Mooi FR. 2009. Improving pertussis vaccination. Hum. Vaccine 5:497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Williamson P, Matthews R. 1996. Epitope mapping the Fim2 and Fim3 proteins of Bordetella pertussis with sera from patients infected with or vaccinated against whooping cough. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 13:169–178. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Packard ER, Parton R, Coote JG, Fry NK. 2004. Sequence variation and conservation in virulence-related genes of Bordetella pertussis isolates from the UK. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:355–365. 10.1099/jmm.0.05515-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Octavia S, Maharjan RP, Sintchenko V, Stevenson G, Reeves PR, Gilbert GL, Lan R. 2011. Insight into evolution of Bordetella pertussis from comparative genomic analysis: evidence of vaccine-driven selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:707–715. 10.1093/molbev/msq245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mooi FR, van Oirschot H, Heuvelman K, van der Heide HG, Gaastra W, Willems RJ. 1998. Polymorphism in the Bordetella pertussis virulence factors, p 69/pertactin and pertussis toxin in The Netherlands: temporal trends and evidence for vaccine-driven evolution. Infect. Immun. 66:670–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bottero D, Gaillard ME, Fingermann M, Weltman G, Fernández J, Sisti F, Graieb A, Roberts R, Rico O, Ríos G, Regueira M, Binsztein N, Hozbor D. 2007. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, pertactin, pertussis toxin S1 subunit polymorphisms, and surfaceome analysis of vaccine and clinical Bordetella pertussis strains. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:1490–1498. 10.1128/CVI.00177-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. King AJ, Berbers G, van Oirschot HF, Hoogerhout P, Knipping K, Mooi FR. 2001. Role of the polymorphic region 1 of the Bordetella pertussis protein pertactin in immunity. Microbiology 147:2885–2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Watanabe M, Nagai M. 2002. Effect of acellular pertussis vaccine against various strains of Bordetella pertussis in a murine model of respiratory infection. J. Health Sci. 48:560. 10.1248/jhs.48.560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gzyl A, Augustynowicz E, Gniadek G, Rabczenko D, Dulny G, Slusarczyk J. 2004. Sequence variation in pertussis S1 subunit toxin and pertussis genes in Bordetella pertussis strains used for the whole-cell pertussis vaccine produced in Poland since 1960: efficiency of the DTwP vaccine-induced immunity against currently circulating B. pertussis isolates. Vaccine 22:2122–2128. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Komatsu E, Yamaguchi F, Abe A, Weiss AA, Watanabe M. 2010. Synergic effect of genotype changes in pertussis toxin and pertactin on adaptation to an acellular pertussis vaccine in the murine intranasal challenge model. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:807–812. 10.1128/CVI.00449-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van Gent M, van Loo IH, Heuvelman KJ, de Neeling AJ, Teunis P, Mooi FR. 2011. Studies on Prn variation in the mouse model and comparison with epidemiological data. PLoS One 6:e18014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Denoël P, Godfroid F, Guiso N, Hallander H, Poolman J. 2005. Comparison of acellular pertussis vaccines-induced immunity against infection due to Bordetella pertussis variant isolates in a mouse model. Vaccine 23:5333–5341. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Novichkov PS, Wolf YI, Dubchak I, Koonin EV. 2009. Trends in prokaryotic evolution revealed by comparison of closely related bacterial and archaeal genomes. J. Bacteriol. 191:65–73. 10.1128/JB.01237-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rocha EP, Smith JM, Hurst LD, Holden MT, Cooper JE, Smith NH, Feil EJ. 2006. Comparisons of dN/dS are time dependent for closely related bacterial genomes. J. Theor. Biol. 239:226–235. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang Z, Bielawski JP. 2000. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15:496–503. 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01994-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kudla G, Murray AW, Tollervey D, Plotkin JB. 2009. Coding-sequence determinants of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Science 324:255–258. 10.1126/science.1170160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Locht C, Coutte L, Mielcarek N. 2011. The ins and outs of pertussis toxin. FEBS J. 278:4668–4682. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Imperi F, Tiburzi F, Fimia GM, Visca P. 2010. Transcriptional control of the pvdS iron starvation sigma factor gene by the master regulator of sulfur metabolism CysB in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1630–1642. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kredich NM. 1992. The molecular basis for positive regulation of cys promoters in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2747–2753. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01453.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boucher PE, Maris AE, Yang MS, Stibitz S. 2003. The response regulator BvgA and RNA polymerase alpha subunit C-terminal domain bind simultaneously to different faces of the same segment of promoter DNA. Mol. Cell 11:163–173. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Boucher PE, Murakami K, Ishihama A, Stibitz S. 1997. Nature of DNA binding and RNA polymerase interaction of the Bordetella pertussis BvgA transcriptional activator at the fha promoter. J. Bacteriol. 179:1755–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Boucher PE, Yang MS, Schmidt DM, Stibitz S. 2001. Genetic and biochemical analyses of BvgA interaction with the secondary binding region of the fha promoter of Bordetella pertussis. J. Bacteriol. 183:536–544. 10.1128/JB.183.2.536-544.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boucher PE, Yang MS, Stibitz S. 2001. Mutational analysis of the high-affinity BvgA binding site in the fha promoter of Bordetella pertussis. Mol. Microbiol. 40:991–999. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Decker KB, Chen Q, Hsieh ML, Boucher P, Stibitz S, Hinton DM. 2011. Different requirements for σ region 4 in BvgA activation of the Bordetella pertussis promoters P(fim3) and P(fhaB). J. Mol. Biol. 409:692–709. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mattoo S, Miller JF, Cotter PA. 2000. Role of Bordetella bronchiseptica fimbriae in tracheal colonization and development of a humoral immune response. Infect. Immun. 68:2024–2033. 10.1128/IAI.68.4.2024-2033.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Łochowska A, Iwanicka-Nowicka R, Zielak A, Modelewska A, Thomas MS, Hryniewicz MM. 2011. Regulation of sulfur assimilation pathways in Burkholderia cenocepacia through control of genes by the SsuR transcription factor. J. Bacteriol. 193:1843–1853. 10.1128/JB.00483-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Achtman M. 2012. Insights from genomic comparisons of genetically monomorphic bacterial pathogens. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367:860–867. 10.1098/rstb.2011.0303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brinig MM, Cummings CA, Sanden GN, Stefanelli P, Lawrence A, Relman DA. 2006. Significant gene order and expression differences in Bordetella pertussis despite limited gene content variation. J. Bacteriol. 188:2375–2382. 10.1128/JB.188.7.2375-2382.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Caro V, Bouchez V, Guiso N. 2008. Is the sequenced Bordetella pertussis strain Tohama I representative of the species? J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2125–2128. 10.1128/JCM.02484-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bouchez V, Caro V, Levillain E, Guigon G, Guiso N. 2008. Genomic content of Bordetella pertussis clinical isolates circulating in areas of intensive children vaccination. PLoS One 3:e2437. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. King AJ, van Gorkom T, van der Heide HG, Advani A, van der Lee S. 2010. Changes in the genomic content of circulating Bordetella pertussis strains isolated from the Netherlands, Sweden, Japan and Australia: adaptive evolution or drift? BMC Genomics 11:64. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bart MJ, van Gent M, van der Heide HG, Boekhorst J, Hermans P, Parkhill J, Mooi FR. 2010. Comparative genomics of prevaccination and modern Bordetella pertussis strains. BMC Genomics 11:627. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bogdan JA, Nazario-Larrieu J, Sarwar J, Alexander P, Blake MS. 2001. Bordetella pertussis autoregulates pertussis toxin production through the metabolism of cysteine. Infect. Immun. 69:6823–6830. 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6823-6830.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Njamkepo E, Cantinelli T, Guigon G, Guiso N. 2008. Genomic analysis and comparison of Bordetella pertussis isolates circulating in low and high vaccine coverage areas. Microbes Infect. 10:1582–1586. 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, Hall KP, Evers DJ, Barnes CL, Bignell HR, Boutell JM, Bryant J, Carter RJ, Keira Cheetham R, Cox AJ, Ellis DJ, Flatbush MR, Gormley NA, Humphray SJ, Irving LJ, Karbelashvili MS, Kirk SM, Li H, Liu X, Maisinger KS, Murray LJ, Obradovic B, Ost T, Parkinson ML, Pratt MR, Rasolonjatovo IM, Reed MT, Rigatti R, Rodighiero C, Ross MT, Sabot A, Sankar SV, Scally A, Schroth GP, Smith ME, Smith VP, Spiridou A, Torrance PE, Tzonev SS, Vermaas EH, Walter K, Wu X, Zhang L, Alam MD, Anastasi C, et al. 2008. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 456:53–59. 10.1038/nature07517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z. 2009. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect breakpoints of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 25:2865–2871. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Albers CA, Lunter G, MacArthur DG, McVean G, Ouwehand WH, Durbin R. 2011. Dindel: accurate indel calls from short-read data. Genome Res. 21:961–973. 10.1101/gr.112326.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Harris SR, Feil EJ, Holden MT, Quail MA, Nickerson EK, Chantratita N, Gardete S, Tavares A, Day N, Lindsay JA, Edgeworth JD, de Lencastre H, Parkhill J, Peacock SJ, Bentley SD. 2010. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science 327:469–474. 10.1126/science.1182395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP. 1998. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:5857–5864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marchler-Bauer A, Zheng C, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Bryant SH. 2013. CDD: conserved domains and protein three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D348–D352. 10.1093/nar/gks1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52:696–704. 10.1080/10635150390235520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Diavatopoulos DA, Cummings CA, Schouls LM, Brinig MM, Relman DA, Mooi FR. 2005. Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, evolved from a distinct, human-associated lineage of B. bronchiseptica. PLoS Pathog. 1:e45. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Park J, Zhang Y, Buboltz AM, Zhang X, Schuster SC, Ahuja U, Liu M, Miller JF, Sebaihia M, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Harvill ET. 2012. Comparative genomics of the classical Bordetella subspecies: the evolution and exchange of virulence-associated diversity amongst closely related pathogens. BMC Genomics 13:545. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. 2012. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29:1969–1973. 10.1093/molbev/mss075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yu NY, Laird MR, Spencer C, Brinkman FS. 2011. PSORTdb—an expanded, auto-updated, user-friendly protein subcellular localization database for Bacteria and Archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D241–D244. 10.1093/nar/gkq1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B Stat. Methodol. 57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characteristics of 343 B. pertussis strains used in this study.

List of SNPs identified in this study.

Pseudogenes shared by Tohama and 18323.

Overview of strains used for production of pertussis vaccines.

SNP densities per functional category, subcellular location, Bvg regulation, gene, and intergenic region.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of all isolates included in this study (see Table S1). (A) The complete tree of all isolates rooted on a ST15 B. bronchiseptica isolate, strain MO149. The branch leading to MO149 has been shortened to allow the relationships within B. pertussis to be seen. (B) A zoomed view of the maximum likelihood tree of lineage II to allow the relationships in this lineage to be more clearly seen. Scale bars indicate numbers of SNPs. Download

Bayesian skyline plot of B. pertussis illustrating variation in effective population size of lineage IIb over time. Download

Gene loss in B. pertussis isolates compared to Tohama I (A) and the distribution of accessory contigs not present in Tohama I (B). Download

Overview of alleles coding for antigens known to induce protection and included in modern acellular pertussis vaccines. Download

Polymorphisms in the bvgA and fhaB promoter region. Download