Abstract

The validity of an accelerometric system (Myotest©) for assessing vertical jump height, vertical force and power, leg stiffness and reactivity index was examined. 20 healthy males performed 3ד5 hops in place”, 3ד1 squat jump” and 3× “1 countermovement jump” during 2 test-retest sessions. The variables were simultaneously assessed using an accelerometer and a force platform at a frequency of 0.5 and 1 kHz, respectively. Both reliability and validity of the accelerometric system were studied. No significant differences between test and retest data were found (p < 0.05), showing a high level of reliability. Besides, moderate to high intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) (from 0.74 to 0.96) were obtained for all variables whereas weak to moderate ICCs (from 0.29 to 0.79) were obtained for force and power during the countermovement jump. With regards to validity, the difference between the two devices was not significant for 5 hops in place height (1.8 cm), force during squat (-1.4 N · kg−1) and countermovement (0.1 N · kg−1) jumps, leg stiffness (7.8 kN · m−1) and reactivity index (0.4). So, the measurements of these variables with this accelerometer are valid, which is not the case for the other variables. The main causes of non-validity for velocity, power and contact time assessment are temporal biases of the takeoff and touchdown moments detection.

Keywords: measurement, biomechanics, precision, leg stiffness, in-situ

INTRODUCTION

Accurate assessment of biomechanical properties of the human lower limb in field conditions interests not only sport scientists, but also coaches and practitioners since it reflects, for instance, the efficiency of training programmes. For that aim, sport experts typically use valid laboratory-based instruments such as the different types of force platforms (PF) [1, 9, 14, 19, 22–24, 26, 32], photoelectric cells [6, 10, 21] and contact mats [5, 16, 34]. Nowadays, ever-expanding devices make it possible to assess lower limb properties in field conditions. One of these measurement tools is the Myotest® (Myotest SA, Switzerland), which consists of a transportable and autonomous 3D accelerometric system (AS). AS is more involved than just acquiring and recording signals. It is a data logger allowing one to instantaneously evaluate the following variables from acceleration data:

jumping height (H),

vertical force (Fv) and power (P),

leg stiffness (kleg) and reactivity index (RI).

Accuracy of AS has been recently studied in the literature, showing comparison with photoelectric cells for jump height assessment [10, 33], and with a force plate for assessing the force and power during squat and bench press [15]. However, comparison of AS and PF has never been done to demonstrate the quality level of the AS measurements compared to PF. For that aim, sport experts typically use valid laboratory-based instruments such as the different types of force platforms [1, 9, 12, 17, 20–22, 24, 32]. Moreover, the reliability and validity of AS for assessing leg stiffness and reactivity need to be investigated.

Basically, vertical jump performance corresponds to the difference between the centre of mass position at the standing posture and its position at the peak of the jump, which could be estimated using the flight time (FT) method [5, 20, 29]. Fv corresponds to product of body mass (m) and vertical acceleration (av) according to Newton's Second Law. Besides, power is equal to the product of force and velocity, which are both measurable from acceleration data. As regards leg stiffness, it corresponds to the ratio of Fv to the displacement (▵CoM) of the centre of mass (CoM) according to the widely used spring-mass model of McMahon et al. [30]. The latter considers the human lower limb as a linear vertical spring supporting the whole body mass (i.e. m) and that the actions of the lower limb segments are integrated once. Thus, the whole lower limb behaves like a linear mechanical spring, that is, the spring constant (k) represents the lower limb stiffness (i.e. kleg).

Before using the AS for scientific purposes, it would be essential to verify its ability to reflect what it is designed to measure [4]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the reliability and validity of the accelerometric system for assessing H, F and P as well as kleg and RI. Three types of standard vertical jump tasks were proposed for examining the device: 5 maximal hopping in place (5H), 1 single countermovement jump (CMJ), and 1 single squat jump (SJ). In this perspective, the different measurements obtained by the AS were compared to those obtained by the PF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Twenty males took part in this study. The participants were physical education students and physiotherapists (age: 27 ± 6 years, body mass: 74.52 ± 7.16 kg and height: 1.78 ± 0.06 m). They were all amateur sportsman who train once or twice per week. None of them was involved in a jump-based activity. Subjects refrained from drinking alcohol or caffeine-containing beverages for 24 hours before testing, to avoid any interference in the experiment. Each subject completed all trials in the same time period of test days to eliminate any influence of circadian variation. The temperature of the room was the same at each session (22°C). The experimental protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Université Paris-Sud and according to the ethical principles laid out in the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave their written consent to the experiment after having been informed of the aims and the risks of testing procedures. In addition, they kindly accepted to wear the same clothes and shoes for both test and retest sessions.

Procedures

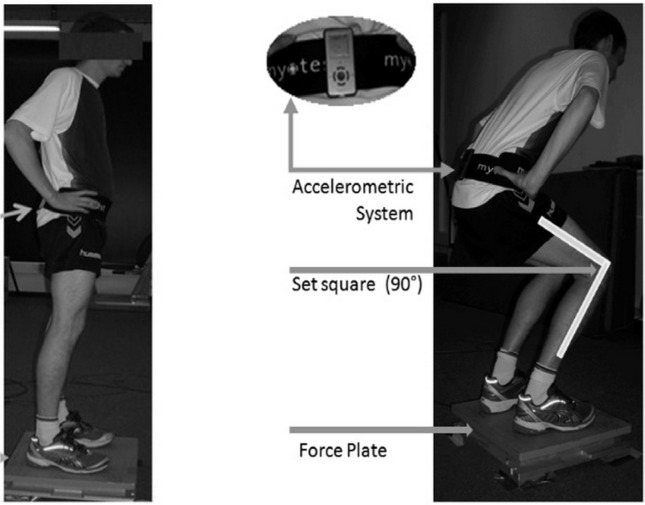

The experiment consists of two identical test and retest sessions separated by 2-3 days. For both sessions, the participants were tested by the same experimenters and at the same hour of the day in order to control the circadian fluctuation [3]. Each session consists of three repetitions of each of the following tasks: 5H, a single SJ and a single CMJ. Participants were equipped with a Myotest® device (length × width × depth: 9.5 × 5 × 1 cm, mass: 60 g). The device was attached to a belt and vertically fixed on the middle of the lower back (Figure 1). The trials were simultaneously recorded by the accelerometric system at a sampling frequency of 500 Hz and by a 0.4×0.4 m force plate (AMTI OR 6-5, Watertown, MA, USA) at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz (Figure 1). Before each trial, they were asked to stand over the PF assuming a vertical posture, as well as to keep hands placed on their waist during the three jumping conditions in order to avoid upper-body interference caused by arm swing [27]. After the touch-down of each of the tasks, the participants were instructed to reassume a vertical standing posture and to wait for the final acoustic signal.

FIG. 1.

STANDING POSITION AT THE BEGINNING OF ALL JUMP TASKS (LEFT SIDE) AND SEMI-SQUAT POSITION REACHED AND HELD DURING SQUAT JUMP TEST (RIGHT SIDE).

Note: The figure shows the set square used to control the knee angle during SJ and the attachment of the accelerometric system to the lower back

The rest between two consecutive jump trials of the same set was approximately 30 seconds and the rest between sets (5H, SJ, or CMJ) was 3 minutes. After performing their standardized warm-up and prior testing, the subjects completed familiarization trials for 5H, SJ and CMJ by following instructions and feedback given by the experimenters. Only successful trials were taken into account. The participants were kindly asked to respect the protocol and to repeat the trial if a jump was incorrectly performed. This validation protocol respected the recommendations of Atkinson and Nevill [4].

Tasks

5H protocol: For the 5H test, the participants were asked to hop in place 6 times as high as possible while reducing the ground contact time [16]. The first hop served as a CMJ (impetus) and was consequently excluded from analysis. The remaining 5 effective jumps were retained and averaged for analysis (mean of the 5 hops). The instructions given before the 5H test were as follows: “Upon the acoustic signal, perform an initial countermovement jump (impetus), after which perform 6 hops in place, with minimal knee flexion and a maximal jumping height. After the 6th jump, reassume a vertical standing posture and wait for final acoustic signal.” Multiple trials were performed under researcher supervision in order to familiarize the participants with this kind of hopping task and to optimize the leg stiffness by reducing the effect of technique. The recording of data began only if the technique of bouncing was acquired.

CMJ protocol: In order to perform a countermovement jump, the participants were instructed to freely flex the knees and to jump once as high as possible. This procedure corresponds to the instructions advised by the manufacturer.

SJ protocol: For the squat jump test, the participants were asked to reach and hold a semi-squat position [∼ 90° knee flexion controlled by a 0.4×0.4 m set square (maintained by the experimenter) as biofeedback] (Figure 1) until an acoustic signal was given, and to jump once as high as possible without performing any countermovement before jumping.

Jump height assessment

The vertical jump height was assessed using the FT data [5, 20, 29], as follows:

| 1 |

where g = acceleration due to gravity.

For PF measurements, FT corresponds to the lapse of time when the vertical ground reaction force is equal to zero. However, AS considers the FT as time duration that elapses between the moment of maximal vertical velocity (before take-off) and the moment of minimal velocity after touch-down (tvmin afterpeak). Then the vertical jump height is estimated by AS as follows:

| 2 |

Vertical force and power assessment

Vertical force (Equation 3) and power (Equation 4) were assessed using the following equations:

| 3 |

| 4 |

The vertical velocity (vv) was calculated from the integration of av data as proposed by Cavagna for the force platform [11] and as proposed by the device's manufacturer for the accelerometer as follows:

For PF measurements:

| 5 |

For AS: vv = ∫av dt in cm · s−1

To reduce the error due to the integration process, the frequency of acquisition for both devices was calibrated on the highest possible value: 1000 Hz for the force platform and 500 Hz for the accelerometer.

Leg stiffness and reactivity index

For PF measurements, leg stiffness (kN · m-1) was calculated as the ratio of maximal Fv (in kN) to ▵CoM [30]. However, for AS, leg stiffness was calculated as the ratio of concentric force (when vv is equal to zero) to ▵CoM, as proposed by Dalleau et al. [16]. ▵CoM was calculated by integrating vv during the grounding phase from its minimal position (i.e. tvmin afterpeak) to its zero position (v0). In order to check the linearity of the lower limb movements and its accordance with theoretical linear spring behaviour, the linearity of the curve of Fv in function of ▵CoM was verified (Figure 2). An r2>.80 was chosen as a threshold to consider the bouncing behaviour as a linear spring oscillation. All the retained jumps met this criterion.

FIG. 2.

TYPICAL SHAPE OF EXPERIMENTAL VERTICAL FORCE TO CENTRE OF MASS DISPLACEMENT CURVE, REPRESENTING A TYPICAL LOWER LIMB FLEXION-EXTENSION DURING THE HOPPING IN PLACE TEST.

Note: The dotted line represents the leg stiffness.

Reactivity index corresponds to the ratio of FT to contact time (CT). CT corresponds to the time of presence of a ground reaction force signal over a jump (oscillation period) for PF measurement, whereas it corresponds to the time that elapses from the position of the maximal velocity (tvmax) to tvminafterpeak (see Equation 2).

Statistical analysis

All descriptive statistics were used to verify whether the basic assumption of normality of all studied variables was met. Shapiro-Wilk tests revealed no abnormal data pattern. The statistical tests were processed via SPSS® (version 16.0, Chicago, IL). In addition, statistical power and effect sizes were calculated using G*Power 3. Statistical power was 1 for all jump modalities with a sample size inferior to 20 subjects and large effect sizes.

The test-retest reliability of the accelerometric system was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (2, 1) (relative reliability) [8] in order to describe how strongly individual scores in the same session and throughout test and retest sessions resembled each other. An ICC of r=0.8 represents good agreement, and a value r>0.9 is considered to indicate excellent agreement [18]. Coefficients of variation (CV%) were also calculated to measure the dispersion of the scores of the test and retest. A coefficient of variation CV ≤ 10% was interpreted as an insignificant difference between test and retest sessions [4]. Besides, the method of Bland and Altman (absolute reliability) [7] allowed determination of test-retest systematic bias ± random error as well as lower and upper limits of agreement (LoA). According to Atkinson and Nevill, systematic bias refers to the general trend for the measurements to be different in a particular direction (either positive: upper LoA or negative: lower LoA) whereas the random error refers to the degree to which the repeated measurements vary for the individuals [4]. Paired Student T-tests were used to detect any significant systematic bias between the scores of the two sessions (test and retest).

The concurrent validity was assessed using ICCs (2, 1) [8] in order to describe how strongly individual scores obtained by the two methods resembled each other. The Bland-Altman method allowed determination of systematic bias between the accelerometric system and the force platform (± random error) and the lower and upper LoA [7]. Besides, coefficients of correlation (R2) of the between-device differences were plotted. The level of heteroscedasticity was set at R2 = 0.1; thus, a coefficient of correlation less than 0.1 (R2 <0.1) means that the variables are homoscedastic [4]. Additionally, independent-samples Student T-tests were used in order to detect any significant systematic bias between AS and PF data at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

The results are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

TABLE 1.

TEST-RETEST RELIABILITY OF ACCELEROMETRIC SYSTEM

| CV% | ICC (95% CI) | Systematic Bias | Random Error | Student T test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jump Height | |||||

| 5H-H (cm) | 6.42 | 0.74 -0.85 | 1.1 | 4.4 | NS |

| SJ-H (cm) | 4.25 | 0.82 -0.84 | -1 | 6.2 | NS |

| CMJ-H (cm) | 4.31 | 0.80 -0.89 | -0.2 | 4.8 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Force, Velocity & Power | |||||

| Fsj (N · kg−1) | 3.30 | 0.85 -0.92 | -0.5 | 1.7 | NS |

| Vsj (cm · s−1) | 6.41 | 0.85 -0.92 | -7.8 | 29.7 | NS |

| Psj (W · kg−1) | 6.03 | 0.74 -0.83 | -1.8 | 6.4 | NS |

| Fcmj (N · kg−1) | 4.24 | 0.66 -0.79 | -0.6 | 2.3 | NS |

| Vcmj (cm · s−1) | 11.09 | 0.66 -0.42 | 3.8 | 22.1 | NS |

| Pcmj (W · kg−1) | 13.36 | 0.29 -0.45 | 2.8 | 6.9 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Contact Time, Leg Stiffness & Reactivity Index | |||||

| CT (ms) | 5.70 | 0.88 -0.93 | + 3.9 | 19.4 | NS |

| IR | 7.86 | 0.94 -0.96 | -0.2 | 0.3 | NS |

| kleg (kN · m−1) | 6.03 | 0.86 -0.92 | + 2.8 | 8 | NS |

Note: NS: no significant difference between test and retest mean values (p < .05)

TABLE 2.

CONCURRENT VALIDITY OF ACCELEROMETRIC SYSTEM VS FORCE PLATFORM

| ICC (95% CI) | Systematic Bias (cm) | Random Error (cm) | Lower LoA (cm) | Upper LoA (cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jump Height | |||||

| 5H-H (cm) | 0.9 -0.94 | + 1.8 | ± 15.3 | -13.4 | 17.1 |

| SJ-H (cm) | 0.71 -0.79 | + 5.6 * | ± 11.7 | -6.1 | 17.4 |

| CMJ-H (cm) | 0.79 -0.86 | + 3.6 * | ± 13.1 | -10.7 | 17.4 |

|

| |||||

| Force, Velocity & Power | |||||

| Fsj (N · kg−1) | 0.63 -0.78 | -1.4 | ± 2.4 | -6.6 | 3.8 |

| Vsj (cm · s−1) | 0.32 -0.35 | + 11.1 * | ± 4.4 | -12.9 | 35.1 |

| Psj (W · kg−1) | 0.18 -0.31 | + 11.7 * | ± 16.9 | -22.4 | 46 |

| Fcmj (N · kg−1) | 0.68 -0.79 | + 0.1 | ± 3 | -6.3 | 6.6 |

| Vcmj (cm · s−1) | 0.37 -0.47 | + 15.8 * | ± 14.4 | -19.7 | 51.4 |

| Pcmj (W · kg−1) | 0.19 -0.46 | + 16.7 * | ± 21.6 | -38 | 71.6 |

| Contact Time, Leg Stiffness & Reactivity Index | |||||

| CT (ms) | 0.73 -0.91 | -69 * | ± 21 | 7 | 131 |

| IR | 0.74 -0.80 | + 0.4 | ± 0.9 | -1.5 | 2.4 |

| kleg (kN · m−1) | 0.76 -0.87 | + 7.8 | ± 12.7 | -23.6 | 39.3 |

Note: the signes (+) and (-) respectively refer to a higher and a lower values of AS compared to the reference value obtained by PF.

Statistically significant systematic bias between both systems at p < .05

Test-retest reliability

No significant differences between the test and retest were reported for all studied variables (p > 0.05) (Table 1). All CVs were lower than 10% for all studied variables except for Vcmj and Pcmj, which were 11.09% and 13.36%, respectively. Besides, the ICC values were between 0.74 and 0.89 for jumping heights, and 0.86 and 0.96 for reactivity index and leg stiffness, which was not the case for force and power during the countermovement jump (0.29 < ICCs < 0.79).

Concurrent validity

Regardless of significance level, the mean values of AS were higher than those of PF for all studied variables except force during SJ and CT during hopping in place, as shown in Table 2. The Student T-test showed significant differences between AS and PF for jump height during SJ (SJ-H) and CMJ (CMJ-H), and for vertical velocity and power during SJ and CMJ. The difference between both devices was also significant for CT assessment with lower values when using AS (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this validation study was to investigate the reliability of an autonomous and transportable accelerometric system, and its validity compared to the force platform for estimating (a) vertical jump height, (b) vertical force and power, and (c) leg stiffness and reactivity index during vertical jump tasks.

AS showed high test-retest reliability (Table 1) for assessing (a), (b) and (c). In addition, the results showed good CVs (< 10%) for all studied variables, except for velocity and power during the countermovement jump. The ICCs showed moderate to high values for (a) [from 0.74 to 0.89], (c) [from 0.86 to 0.96] and force, velocity and power during SJ [from 0.74 to 0.92], by following the criterion of the literature regarding the magnitude of the group-level correlation [18]. Our results are in accordance with the literature regarding the jumping height recorded during hopping in place (ICC: 0.86-0.96, CV: 5.1%), SJ (ICC: 0.86-0.96, CV: 4.93%) and CMJ (ICC: 0.93–0.98, CV: 3.62%) [10].

The results showed that AS is able to reproduce the same measurement precisions at different moments for the above-mentioned variables. Considering validity, PF and AS showed good accuracy as demonstrated by good ICC (>0.73) and low bias (<1%) for 5H height, and leg stiffness and reactivity index, moderate ICC (>0.63) for force during SJ and CMJ, and insignificant T-test, which shows a strong association with the reference method. What are the possible explanations of the lack of validity for the other parameters, i.e. (a) SJ and CMJ height, (b) velocity and power during both SJ and CMJ, and (c) CT during 5H?

AS validity for vertical jump height assessment

As regards jumping heights measurement, the systematic biases of SJ height (5.63 cm) and CMJ height (3.66 cm) were significant (p < 0.05), with weak to moderate ICC values (0.71 < ICC < 0.86). These biases seem to be related to FT estimation, which was different according to each assessment device. In the flight time method (Equation 1) [5, 20], it is assumed that the CoM position at takeoff is the same as the CoM position at landing. So, the vertical jump height corresponds to the CoM elevation between the instant of landing and the instant of takeoff—namely, the flight time.

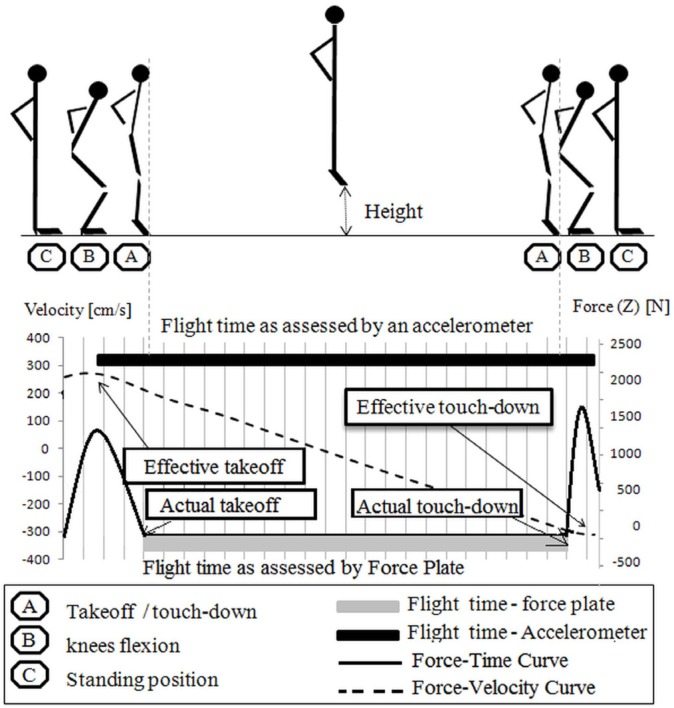

When using the force platform, FT is measured as the difference between the two instants of “actual” take off and “actual” landing (Figure 3); that is, when force is equal to zero [29]. This is not the case for AS, which considers FT as the lapse of time between the maximum value of positive velocity and the minimum value of negative velocity, which are both accessible from the velocity-time curve (Figure 3), thus estimating the “effective” takeoff and landing, respectively. This method could induce bias of flight time measurement between AS and PF. According to our data, a maximal velocity could be achieved at the end of the concentric phase shortly before the actual takeoff (Figure 3). This could be considered as the beginning of flight time, which induces a slight underestimation at the start of the takeoff. That was also the case of the effective landing, which occurs shortly after the actual landing, inducing a slight overestimation at the start of the touchdown (Figure 3). This has also been reported by Casartelli et al., who compared the jumping heights obtained by AS to those obtained by photoelectric cells [10]. Both of these approximations involve an FT overestimation which reflects the difference of measurements between AS and PF.

FIG. 3.

A COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP AS RECORDED BY THE AS AND PF.

Note: The upper curve represents the force (Fz) and its corresponding instants of takeoff and touchdown. The lower curve shows the velocity (which results from the double integration of force) and its corresponding takeoff and touchdown. The flight time is slightly overestimated when using velocity data.

Differences of AS validity level between the three jumping modalities are mainly dependent on the prior jumping concentric phase (propulsive phase of the jump), which is specific to each type of jump. As shown in the method section, the jumping height was measured using the flight time data (Equation 2).

The sources of error could be the detection of the minimum value of negative velocity (vminafterpeak), which is considered as the “effective touchdown” while calculating FT, and the detection of the maximum value of positive velocity (vmax), which is considered as the “effective takeoff ”. A maximal velocity could be achieved at the end of the concentric phase shortly before the actual takeoff. This could be considered as the beginning of the flight time, which induces a slight underestimation of the instant of the takeoff. That was also the case of the effective landing, which is considered to occur shortly after the actual landing, inducing a slight overestimation of the instant of touchdown, as previously reported by Casartelli et al., who compared AS jumping scores to those obtained by photoelectric cells. Both of these approximations involve an overestimation of flight time, which could explain the countermovement jump height difference (3.6 cm). It is important to mention that the mean value of CMJ height measured in this study was lower than the values obtained in university students (45-46 cm) [31] and was close to the jumping height of male rhythmic gymnasts (36 cm) [17], and 14-year-old boys (36.9 cm) using the Ergojump Bosco System [34], showing that our participants achieved moderate CMJ heights. Based on our results, we suggest that a similar overestimation would be observed in participants within the range of values from 22.6 to 51.1 cm, close to our study. Additionally to its high reproducibility for assessing the countermovement jump height, the validity of AS is deemed acceptable by taking into account the amount of systematic bias (3-4 cm) recorded in this study, the variability of the jumping behaviours and the practical purposes of this jumping test.

Therefore, the flight time is more likely to be the major source of bias since it is dependent on the jumping modalities. Hopping in place particularly required a very short contact time (about 90 ms in this study), which is why AS encountered low probability to make errors while detecting vmax. That is why the difference of the hopping in place heights between the two devices was very low (1.8 cm), showing that “effective takeoff” was close to “actual takeoff”. Therefore, the hopping in place height could be estimated using an accelerometer system with the insurance that the flight time is as near as possible from the lapse of time between actual takeoff and touchdown.

That was not the case of squat and countermovement jump heights estimation, which showed high and significant systematic biases (Table 2). The protocol of squat and countermovement jumps could be the reason for flight time overestimations. Indeed, knee angle has to be 90° prior to jumping during SJ and was freely chosen during CMJ. Mechanical variations due to these modalities seem to increase the probability of error while detecting vmax, probably because of longer contact time due to knee flexion compared to hopping in place. In spite of the stabilization moment at the end of lowering during a squat jump trial, the accelerometric system showed error while estimating FT. The static nature of the squat jump does not seem to reduce mechanical variability compared to the countermovement jump as one might imagine. Both modalities affected the moment of vmax.

AS validity for force and power assessment

The difference of velocity and power estimations between AS and PF was significant (p < 0.05) with higher values coming from the AS during the SJ task (11.1 cm and 11.7 cm, respectively) as well as CMJ (15.8 and 16.7 cm, respectively), and weak ICCs (from 0.18 to 0.47). The main reason seems to be related to the heteroscedasticity of the data and the specificity of the task. The data of velocity were homoscedastic (R2 = 0.01) for Vsj and slightly heteroscedastic (R2 = 0.11) for Vcmj. The difference between AS and PF was significantly high (Table 2), showing poor validity of AS for assessing velocity during squat and countermovement jumps (p < 0.05).

The heteroscedasticity of velocity scores during the countermovement jump could be explained by the specificity of the countermovement jump technique. Moreover, this could be caused by the constraint of the task, which consisted in jumping with hands over the waist over a force platform. The previous literature showed that, without arm motion, the eccentric phase is used in order to maintain the balance of the system rather than shortening this phase. Consequently, it is difficult for AS to find the real beginning of the concentric phase, which affects the initial value of velocity [2, 25]. The poor validity of AS for assessing power during squat and countermovement jumps seems to be the direct consequence of biases in velocity assessment since it corresponds to the product of force, which is estimated at its just value, times the velocity which is overestimated when assessed by AS.

AS validity for leg stiffness and reactivity assessment

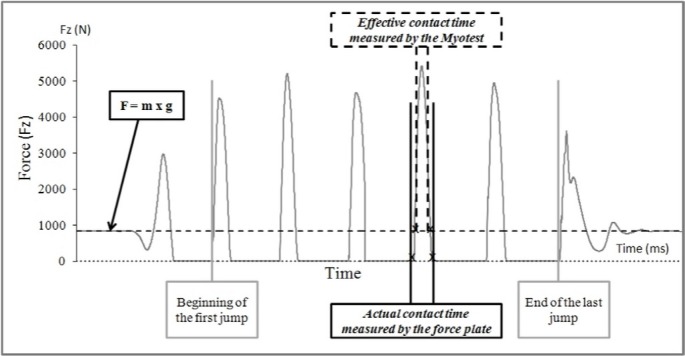

AS was deemed valid for assessing kleg, as shown in Table 2. However, its validity for assessing CT remains critical because it systematically underestimated the “actual” values of CT by 69 ms. This was due to the CT calculation protocol applied by AS. In this method, CT was considered as the lapse of time between the minimal position of velocity after touchdown and its maximal value during the successive takeoff, i.e., when force is equal to body weight (F = m × g). This was not the case for PF, which determines the “actual” CT, i.e. the time between actual touch-down and take-off from the GRF-time curve, irrespective of the magnitude of reaction force exerted on the ground [12, 13]. In contrast, AS measures the “effective” CT, which is considered as the period of time during which vertical force is equal to or greater than body weight (F ≥ m × g) (Figure 4). Obviously, these biases have a knock-on effect on the reactivity index since its calculation uses the contact time data. To conclude, AS could be used for assessing contact time by taking into account this systematic underestimation.

FIG. 4.

COMPARISON BETWEEN THE ACTUAL AND EFFECTIVE CONTACT TIME AS MEASURED BY THE FORCE PLATE AND THE ACCELEROMETRIC SYSTEM, RESPECTIVELY.

Note: The dashed line represents the criteria of determination of touch-down and take-off according to the “m × g” line as assumed by AS. The figure shows that the accelerometric system underestimates the contact time (effective) compared to the force platform (actual contact time).

CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this study was to evaluate the reliability of an accelerometric system and its validity compared to a force platform for assessing vertical jump performance. The results showed a high level of reliability for assessing jumping height, leg stiffness, reactivity index, velocity and power during squat jump and force measurements using the accelerometric system. However, force and power measurements were weakly reliable. The accelerometric system was deemed valid for assessing hopping in place height, force during squat and countermovement jumps as well as leg stiffness and reactivity index. However, the evaluation of jumping height, velocity and power during both squat and countermovement jump was not valid. The main causes of non-validity for velocity and power as well as contact time assessment are due to biases occurring while detecting the takeoff and touchdown moments. That being said, the accelerometric system remains highly reliable for assessing the studied variables. Thus, it could be useful notably to follow up rehabilitation programmes or for long-term athletic monitoring.

Funding

This work has not received any funding resources

Conflicts of interest

none

REFERENCES

- 1.Arampatzis A, Schade F, Walsh M, Bruggemann G.P. Influence of leg stiffness and its effect on myodynamic jumping performance. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2001;11:355–364. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashby B.M, Heegaard J.H. Role of arm motion in the standing long jump. J. Biomech. 2002;35:1631–1637. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson G, Reilly T. Circadian variation in sports performance. Sports Med. 1996;21:292–312. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199621040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson G, Nevill A.M. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217–238. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199826040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosco C, Luhtanen P, Komi P.V. A simple method for measurement of mechanical power in jumping. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occupat. Physiol. 1983;50:273–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00422166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosquet L, Berryman N, Dupuy O. A comparison of 2 optical timing systems designed to measure flight time and contact time during jumping and hopping. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2009;23:2660–2665. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b1f4ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bland J.M, Altman D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bland J.M, Altman D.G. A note on the use of the intraclass correlation-coefficient in the evaluation of agreement between 2 methods of measurement. Comput. Biol. Med. 1990;20:337–340. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(90)90013-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busko K, Madej A, Mastalerz A. Effect of the cycloergometer exercises on power and jumping ability measured during jumps performed on a dynamometric platform. Biol. Sport. 2010;27:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casartelli N, Müller R, Mafiuletti N. Validity and reliability of the Myotest accelerometric system for the assessment of vertical jump height. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010;24:3186–3193. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d8595c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavagna G.A. Force plateforms as ergometers. J. Appl. Physiol. 1975;39:174–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavagna G.A. Symmetry and asymmetry in bouncing gaits. Symmetry. 2012;2:1270–1321. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavagna G.A, Franzetti P, Heglund N.C, Willems P. The determinants of the step frequency in running, trotting and hopping in man and other vertebrates. J. Physiol. (London) 1988;399:81–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chelly M.S, Denis C. Leg power and hopping stiffness: relationship with sprint running performance. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 2001;33:326–333. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200102000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comstock B.A, Solomon-Hill G, Flanagan S.D, Earp J.E, Luk H.Y, Dobbins K.A, et al. Validity of the Myotest® in measuring force and power production in the squat and bench press. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2011;25:2293–2297. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318200b78c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalleau G, Belli A, Viale F, Lacour J.R, Bourdin M. A simple method for field measurements of leg stiffness in hopping. Int. J. Sports. Med. 2004;25:170–176. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Cagno A, Baldari C, Battaglia C, Monteiro M.D, Pappalardo A, Piazza M. Factors influencing performance of competitive and amateur rhythmic gymnastics--gender differences. J. Science. Med. Sport. 2009;12:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donner A, Eliasziw M. Sample size requirements for reliability studies. Stat. Meth. 1987;6:441–448. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farley C.T, Morgenroth D.C. Leg stiffness primarily depends on ankle stiffness during human hopping. J. Biomech. 1999;32:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frick U. Comparison of biomechanical measuring procedures for the determination of height achieved in vertical jumps. Leistungsport. 1991;21:448–453. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glatthorn J.F, Gouge S, Nussbaumer S, Stauffacher S, Impellizzeri F.M, Maffiuletti N.A. Validity and reliability of Optojump photoelectric cells for estimating vertical jump height. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011;25:556–560. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181ccb18d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobara H, Inoue K, Muraoka T, Omuro K, Sakamoto M, Kanosue K. Leg stiffness adjustment for a range of hopping frequencies in humans. J. Biomech. 2010;43:506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobara H, Muraoka T, Omuro K, Gomi K, Sakamoto M, Inoue K, Kanosue K. Knee stiffness is a major determinant of leg stiffness during maximal hopping. J. Biomech. 2009;42:1768–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laffaye G, Taiar R, Bardy B.G. The effect of instruction on leg stiffness regulation in drop jump. Sci. Sports. 2005;20:136–143. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laffaye G, Bardy B, Taiar R. Upper-limb motion and drop jump: effect of expertise. J. Sports Med. Phy. Fit. 2006;46:238–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laffaye G, Choukou M.A. Gender bias in the effect of dropping height on jumping performance in volleyball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010;24:2143–2148. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181aeb140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lees A, Vanrenterghem J, de Clercq D. Understanding how an arm swing enhances performance in the vertical jump. J. Biomech. 2004;37:1929–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Llyod R.S, Oliver J.L, Hughes M.G, Williams C.A. Reliability and validity of field-based measures of leg stiffness and reactive strength index in youths. J. Sports Sci. 2009;27:1565–73. doi: 10.1080/02640410903311572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linthorne N.P. Analysis of standing vertical jumps using a force platform. Am. J. Phys. 2001;69:1198–1204. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMahon T.A, Valiant G, Frederick E.C. Groucho running. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987;62:2326–2337. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.6.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nuzzo J.L, Anning J.H, Scharfenberg J.M. The reliability of three devices used for measuring vertical jump height. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011;25:2580–2590. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181fee650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]