Abstract

In the adult Drosophila midgut the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway is required to specify and maintain the acid-secreting region of the midgut known as the copper cell region (CCR). BMP signaling is also involved in the modulation of intestinal stem cell (ISC) proliferation in response to injury. How ISCs are able to respond to the same signaling pathway in a regionally different manner is currently unknown. Here, we show that dual use of the BMP signaling pathway in the midgut is possible because BMP signals are only capable of transforming ISC and enterocyte identity during a defined window of metamorphosis. ISC heterogeneity is established prior to adulthood and then maintained in cooperation with regional signals from surrounding tissue. Our data provide a conceptual framework for how other tissues maintained by regional stem cells might be patterned and establishes the pupal and adult midgut as a novel genetic platform for identifying genes necessary for regional stem cell specification and maintenance.

Keywords: Drosophila, Copper cells, Heterogeneity, Intestine, Stem cells

INTRODUCTION

Developmental signals that control cell identity and differentiation have been elucidated for many adult tissues (McCracken and Wells, 2012; Rowitch and Kriegstein, 2010; Van Vliet et al., 2012). After differentiation, mechanisms that establish and maintain heterogeneity within that tissue are important for ensuring proper function. In adult tissues, the role of stem cells is unique as, unlike embryonic stem cells, their identity must be stable for the lifetime of the organism (Clarke and Fuller, 2006). Additionally, adult stem cells must constantly make cell fate decisions in response to varied environmental conditions. Failure to regulate cell fate could lead to inappropriate responses to local signals and cell identity changes that could initiate tumorigenesis (Hu and Rosenfeld, 2012). Uncovering mechanisms that regulate tissue diversity is important for understanding how heterogeneous organs, such as the gut, skin and brain, maintain function as new cells are created over a lifetime.

The Drosophila melanogaster intestine contains multiple distinct regions (Buchon et al., 2013; Hartenstein et al., 1992; Marianes and Spradling, 2013; Takashima et al., 2013) that are each maintained by ISCs (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006), making it well suited to investigating how stem cell heterogeneity is established and maintained in a complex tissue. All intestinal adult epithelial cells, including ISCs, arise from adult midgut precursors (AMPs) present in late L3 larvae (Jiang and Edgar, 2009; Mathur et al., 2010; Micchelli et al., 2011; Takashima et al., 2011a). From 0-10 h after pupal formation (APF), larval enterocytes (ECs) are histolyzed, move into the interior of the intestine (Jiang and Edgar, 2009; Mathur et al., 2010), and then are surrounded by dying peripheral cells (PCs) (Takashima et al., 2011b). Initially, AMPs can be identified using esgGal4 UAS-GFP, a marker of ISCs and early diploid daughters (enteroblasts or EBs) in the adult. During pupation, esg-Gal4 becomes progressively restricted to a subset of cells that have or will become adult ISCs (Jiang and Edgar, 2009; Takashima et al., 2011).

One well-studied region of the Drosophila midgut is the copper cell region (CCR). Copper cells function as acid-secreting cells and are located in a discrete region of the middle midgut (Dubreuil, 2004; Strand and Micchelli, 2011) (Fig. 1A). The CCR (Filshie et al., 1971) has been characterized throughout development (Hoppler and Bienz, 1995; Tanaka et al., 2007) and can be identified by nuclear localization of the Hox gene labial (Fig. 1B) (Dubreuil et al., 2001; Hoppler and Bienz, 1994; Strand and Micchelli, 2011) and the cytoskeleton membrane protein α-Spectrin (Fig. 1B′) (Dubreuil et al., 1998), making it an amenable model in which to study heterogeneity in cell identity. Copper cells originate during embryonic development, downstream of Ultrabithorax and Abdominal A expression in neighboring parasegments (Immerglück et al., 1990). The genes encoding the secreted ligands Decapentaplegic (Dpp) and Wingless (Wg) are expressed at the junction of these parasegments and lead to the expression of labial in a subset of midgut epithelial cells (Bilder et al., 1998; Hoppler and Bienz, 1995; Immerglück et al., 1990; Mann and Abu-Shaar, 1996). In the adult midgut, BMP (Guo et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013) and Wnt (Strand and Micchelli, 2011) signals are necessary for labial expression and copper cell formation. Yet members of both the BMP (Guo et al., 2013) and Wnt (Lin et al., 2008) signaling pathways are widely expressed. How labial expression and copper cell identity remain restricted to a small section of the midgut in the adult when the signals necessary for induction are widely expressed remains unknown.

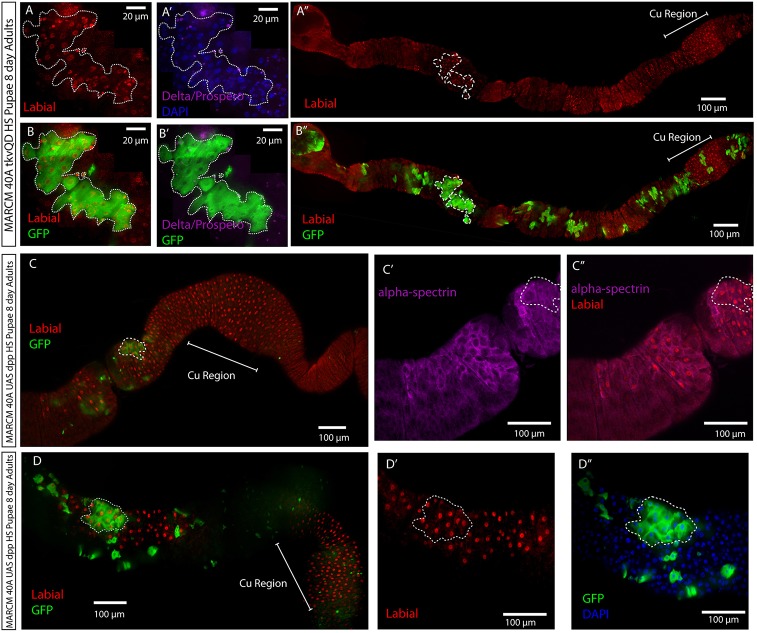

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of the BMP pathway in the adult midgut. (A) Midguts from wild-type flies fed Bromophenol Blue and assayed for acidification. The CCR (Cu Region) is yellow, indicating acidification (pH<2.3). The anterior and posterior midgut is blue, indicating lack of acidification (pH>4). (B,B′) Copper cells are immunopositive for nuclear Labial (red) and high levels of α-Spectrin (green). (C) Using the muscle/trachea driver howts to express dpp muscle for 10 days in the adult does not result in nuclear Labial (red) expression outside the CCR. (D) Constitutively active tkv (tkvQD) was expressed in ECs using Myots for 10 days. Ectopic nuclear Labial (red)-positive cells were not observed outside the CCR. (E) tkvQD was expressed in ISC/EBs using the temperature-inducible ISC/EB driver esgts. Yellow squares indicate location of images in E′-E‴. (E′-E‴) Labial (red) outside of the CCR is diffusely cytoplasmic. DAPI (blue) marks nuclei (E′-E‴). For each image, anterior is to the left.

Here, we identified a period during pupation beginning at 20 h APF when a subset of pupal AMPs receive BMP signals and are specified as copper cells and copper cell ISCs. ISCs that do not receive BMP signals during this window of plasticity are resistant to re-specification in the adult. As such, the BMP signaling pathway can be used in the adult for other purposes, including antagonizing ISC response to injury (Guo et al., 2013).

RESULTS

BMP signaling in the adult intestine is not sufficient for copper cell formation

Recently, we and others have shown that BMP signaling is necessary for the formation of new copper cells by ISCs located in the middle midgut (Guo et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013). Additionally, injury-induced BMP signaling acts autonomously in ISCs in the anterior and posterior midgut to limit their proliferative response to enterocyte damage (Guo et al., 2013). Because injury-induced BMP signaling in the anterior and posterior midgut does not result in new copper cells outside of the CCR (Guo et al., 2013), we explored whether any level of BMP signaling was sufficient to induce copper cell formation along the intestine.

In the adult midgut, circular visceral muscle is the source of the BMP ligand that regulates copper cell differentiation (Guo et al., 2013). We therefore used the temperature-inducible driver how-Gal4 tubulin-Gal80ts (howts) (Guo et al., 2013; Jiang and Edgar, 2009) to drive expression of the BMP signaling ligand dpp in muscle and trachea. At 18°C, Gal80ts is active and represses Gal4 function. At 30°C, Gal80ts is inactivated, thereby allowing for temperature-inducible control of Gal4 activity. Following 10 days of dpp overexpression in muscle and trachea, phospho-Mad (p-Mad) was detectable in all cells (supplementary material Fig. S1A,A′), demonstrating efficient activation of the BMP signaling pathway in the midgut. Despite BMP pathway activation, strong nuclear Labial was never detected in epithelial cells outside the CCR (Fig. 1C) (n=20 intestines).

To assess whether autonomous activation of BMP signaling in ISCs, EBs or ECs could alter cell identity, we expressed a constitutively active form of the type I BMP receptor thickveins Q253D (tkvQD) (Wiersdorff et al., 1996) using two different temperature-inducible Gal4 lines: an EC-specific driver called Myo-Gal4 tubulin gal80ts (Myots) (Jiang et al., 2009) and an ISC/EB driver called esg-Gal4 tubulin gal80ts (esgts) (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006). Flies were reared at 18°C and moved to 30°C immediately after eclosion. Ten days of tkvQD expression using either driver resulted in BMP pathway activation as confirmed by p-Mad staining (supplementary material Fig. S1B-C′). As was the case with dpp overexpression, strong nuclear Labial-positive cells were never found outside of the CCR (Fig. 1D,E) (n=20 intestines for each genotype). Although we could occasionally detect Labial protein in epithelial cells outside the CCR expressing ectopic tkvQD using esgts, it was present diffusely in their cytoplasm (Fig. 1E-E‴). These data, in conjunction with previous results (Guo et al., 2013), argue that BMP signaling is not sufficient for the cell fate transformation of non-CCR cells in the adult.

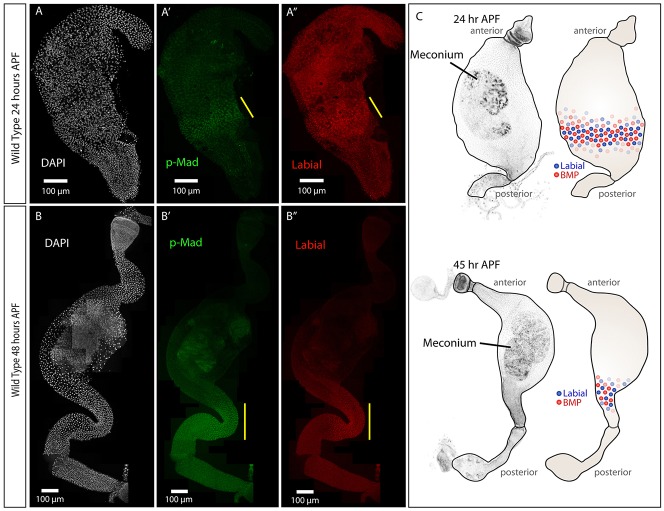

BMP signaling and Labial expression are observed in a subset of cells beginning at 24 h APF

Because adult cells are resistant to transformation by BMP pathway signaling, we hypothesized that cells might have more plasticity earlier in development. The adult gut epithelium is derived from AMPs during pupation (Jiang and Edgar, 2009; Mathur et al., 2010; Micchelli et al., 2011; Takashima et al., 2011a), implicating metamorphosis as a likely time for adult cell specification. To investigate the timing of copper cell formation, we stained pupal midguts with anti-p-Mad and anti-Labial antibodies to characterize the timing of BMP signaling activation and Labial expression. Timed pupae were collected in one-hour windows and dissected every 3-4 h from 0 h APF until eclosion (∼100 h APF at 25°C). p-Mad was first detectable at 20-24 h APF in the posterior half of the pupal midgut (Fig. 2A,A′). Labial was first observed at 24 h APF in the same region (Fig. 2A,A″). As pupal development proceeds, the gut begins to expand to its adult size (Takashima et al., 2011b). During this period, at 48 h APF, p-Mad and Labial remained confined to a band of cells in the posterior midgut (Fig. 2B-B″). The location of active BMP signaling and Labial during early metamorphosis is illustrated in Fig. 2C. The timing and location of BMP signaling and Labial suggests that ∼24 h APF is when regional adult cell identity establishment begins.

Fig. 2.

BMP signaling and Labial are present at the same time and location during pupation. (A-A″) Pupal guts at 24 h APF. (A′) p-Mad staining (green) is present in a band in the posterior (yellow bar) and in a gradient extending anterior. (A″) Labial (red) is strongest in a band in the posterior at the same position as strong p-Mad staining (yellow bar). (B) At 45 h APF, the pupal gut has extended posteriorly and anteriorly. (B′) p-Mad staining (green) is strongest in a band in the posterior pupal midgut (yellow bar). (B″) Labial staining (red) is present in the same location as p-Mad staining (yellow bar) with a sharper posterior border. DAPI (white) marks nuclei in A,B. (C) Diagram depicting Labial and p-Mad (active BMP signaling) localization during pupation. p-Mad and Labial are expressed in a band of cells in the posterior of the pupal midgut just after 24 h APF. These cells continue to express p-Mad and Labial as the gut grows. The meconium represents the remnant of the larval midgut. A-B″ show maximum projections between 2 and 4 µm.

BMP signaling activation during metamorphosis can alter adult cell identity

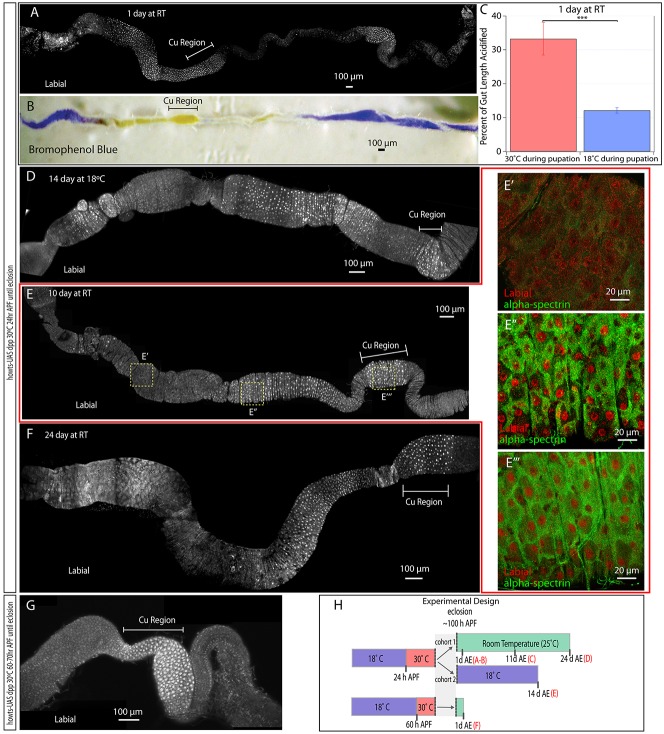

To gain insight into the relevance of the restricted pattern of BMP pathway activation present early in pupation, we used howts to induce expression of dpp in visceral muscle at various times during pupation (supplementary material Fig. S2A) and then determined the effect on pupal AMP differentiation into copper cells (Fig. 3H). dpp expression starting at 24 h APF resulted in p-Mad staining throughout the pupal gut 1 day later, demonstrating efficient BMP pathway activation (supplementary material Fig. S2A′). Upon eclosion, midguts were stained for Labial to determine if any transformation towards copper cell fate had occurred. Cells with strong nuclear Labial staining were present in a majority of the anterior midgut, regions of the posterior midgut, as well as the CCR (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Dpp expressed during pupation results in transformation of the midgut to copper cells. (A) howts UAS-dpp flies moved from 18°C to 30°C at 24 h APF and upon eclosion were stained for Labial (white). Nuclear Labial is present in the CCR (Cu Region), most of the anterior and in a small portion of the posterior midgut. (B) howts UAS-dpp flies moved from 18°C to 30°C at 24 h APF and one day after eclosion fed Bromophenol Blue. Acidified regions (yellow) are present in the CCR, more than half of the anterior and in a small portion of the posterior. (C) howts UAS-dpp flies were fed Bromophenol Blue after being moved to 30°C or maintained at 18°C and the percentage of gut length acidified was determined. The total length of both populations was not significantly different. ***P<0.005. (D) howts UAS-dpp flies kept at 30°C between 24 h APF and eclosion and moved to 18°C for 14 days. Nuclear Labial staining (white) is seen in two patches in the anterior midgut. (E-E‴) howts UAS-dpp flies kept at 30°C between 24 h APF and eclosion and then at room temperature (RT) for 10 days. Nuclear Labial staining (white) extends into the anterior midgut. A higher magnification view of the anterior midgut lacking nuclear Labial (E′), anterior cells expressing nuclear Labial (E″), or the CCR (E‴) shows that α-Spectrin staining (green) is similar in endogenous and ectopic cells expressing nuclear Labial (red). (F) howts UAS-dpp flies kept at 30°C between 24 h APF and eclosion and then at room temperature for 24 days. Nuclear Labial staining (white) is present in much of the anterior midgut. (G) howts UAS-dpp flies moved from 18°C to 30°C at 60 h APF. Upon eclosion, dissected midguts were stained for Labial (white). Nuclear Labial staining (white) is present in the CCR. Labial was observed outside of the CCR only in visceral muscle. (H) A depiction of the experimental design. Letters in red brackets refer to the relevant panels in this figure. For each image, anterior is to the left.

Because copper cells secret acid (Dubreuil, 2004), they can be identified by feeding flies food mixed with Bromophenol Blue and looking for a color shift from blue (pH>4) to yellow (pH<2.3) (Fig. 1A). In midguts from control flies fed yeast mixed with Bromophenol Blue, yellow (pH<2.3) was observed only in the CCR region (Fig. 1A). In midguts from adult flies that received expanded BMP signaling during pupation, the acidified region of the gut expanded to most of the anterior and part of the posterior midgut (Fig. 3B,C). Significantly, the expanded acidification of the midgut correlated with regions of expanded Labial expression (Fig. 3A), suggesting that ectopic cells created by pupal dpp overexpression are functional copper cells.

To determine the effect of continued dpp expression on maintenance of ectopic copper cells, transgenic flies were reared at 30°C, which should result in continued expression of UAS-dpp, at 18°C, which should abolish UAS-dpp expression (Fig. 3D), or at 25°C, in which gal80ts is partially active and therefore should result in intermediate expression of UAS-dpp (Fig. 3E,F). Intestines from flies moved to 18°C after eclosion, for two weeks, had ectopic copper cells in patches, indicating that copper cells are not consistently maintained (Fig. 3D). This suggests that new copper cells are unable to be created in the absence of a consistent source of dpp. Flies reared at 30°C consistently maintained ectopic copper cells, but died in large numbers after one week (data not shown). Flies kept at 25°C, by contrast, had ectopic copper cells present in the anterior of the gut for at least 3 weeks (Fig. 3E,F). Most Labial-positive cells expressed α-Spectrin (Fig. 3E‴) at levels similar to copper cells in the CCR (Fig. 3E″), but unlike non-Labial-expressing regions (Fig. 3E′). In the Drosophila midgut, the turnover of differentiated cells is continuous and the entire gut is renewed every ∼7-10 days (Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006); consequently, the presence of ectopic copper cells for >3 weeks suggests that the turnover of these cells was delayed or that they were newly generated from ISCs outside the CCR.

To determine if pupal AMPs were permissive to transformation at other times during development, flies were shifted to 30°C at various times throughout pupation (Fig. 3G). howts UAS-dpp flies moved to 30°C between 24 and 48 h APF eclosed with similar results as described for Fig. 3A (n=10 intestines). howts UAS-dpp flies moved to 30°C 50-60 h APF also eclosed with ectopic copper cells, albeit with reduced effectiveness (n=10 intestines). However, in intestines from howts UAS-dpp flies moved to 30°C at 60 h APF (n=10 intestines), no cells with copper cell morphology or strong nuclear Labial were observed outside the CCR (Fig. 3G,H). These data suggest that the period of pupation during which ectopic BMP signaling can result in ectopic copper cells ends at ∼60 h APF.

Activation of the BMP pathway in pupal ISCs is sufficient to transform adult stem cell identity

Overexpression of dpp by howts in the pupal midgut results in BMP activation in all pupal AMPs (supplementary material Fig. S2A,A′). To determine whether BMP-induced transformation creates ISCs that give rise to and maintain ectopic copper cells and/or whether transformed copper cells can persist on their own, we used cell-specific Gal4 drivers to activate BMP signaling in subsets of cells during metamorphosis. Myots-Gal4 UAS-GFP, which marks ECs in the adult gut (Jiang et al., 2009), was observed to be expressed in a subset of pupal cells and then at later times in all polyploid cells (supplementary material Fig. S2B), suggesting that it is specific to pupal AMPs fated to become adult ECs. esgts-Gal4 UAS GFP is expressed in a subset of cells starting at 20 h APF that become ISCs and EBs in the adult (Jiang and Edgar, 2009; Micchelli et al., 2011; Takashima et al., 2011a) (supplementary material Fig. S2C).

To confirm that esgts and Myots are specific to the pupal ISCs/EB and EC populations, respectively, each Gal4 line was crossed to UAS RNAi against tkv or labial. Flies were reared at 18°C until 24 h APF and then moved to 30°C until eclosion to allow for RNAi expression during pupation. Upon eclosion, midguts were stained for Labial or fed Bromophenol Blue to assess for copper cell differentiation and function. esgts flies driving expression of tkv or labial RNAi eclosed with a normal number of nuclear Labial-positive cells in the CCR (supplementary material Fig. S2A,A′) and normal acidification (supplementary material Fig. S2C,E). In Myots intestines, however, nuclear Labial-positive cells were absent and there was no evidence of acidification (supplementary material Fig. S3B,B′,D,F). These data confirm that these two drivers are expressed in non-overlapping populations of cells during pupation: Myots is expressed in pupal cells that will become ECs and copper cells and esgts is expressed in pupal cells that will become ISCs.

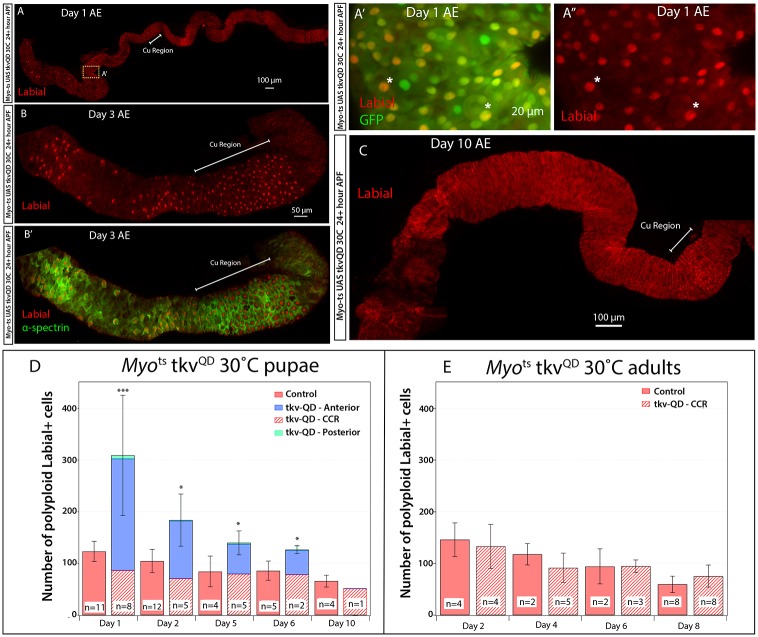

To determine whether Myots could transform pupal AMPs into copper cells, Myots was crossed to UAS-tkvQD (supplementary material Fig. S2D,D′) and reared at 30°C from 24 h APF until eclosion. tkvQD expression starting at 24 h APF resulted in p-Mad staining in the pupal gut one day later, demonstrating efficient BMP pathway activation (supplementary material Fig. S2D,D′). Intestines from Myots UAS-tkvQD flies eclosed with strong nuclear Labial-expressing cells in the anterior and posterior midgut (Fig. 4A-B′). Flies were fed yeast mixed with Bromophenol Blue to assess acidity; however, upon dissection, guts were observed with ruptures in the anterior portion of the gut just below the cardia and very little food was present in the midgut. As a result, tests for acidity could not be performed. Nonetheless, ectopic nuclear Labial-expressing cells exhibited the crescent-shaped morphology characteristic of copper cells (Hoppler and Bienz, 1994) (Fig. 4A′,A″, asterisks). Furthermore, they were strongly positive for α-Spectrin (Fig. 4B′), a membrane-associated protein highly expressed in copper cells and required for their function (Dubreuil et al., 1998, 1997). Together, these data suggest that ectopic BMP signaling pathway activation in AMPs during pupation was sufficient to specify their identity. To determine if ectopic copper cells were maintained, animals were followed post-eclosion. Ectopic nuclear Labial-expressing cells present upon eclosion in Myots-tkvQD flies decreased in number and were replaced by ECs by day 10 (Fig. 4C), indicating that ISCs were not re-specified. To confirm this result, quantification of nuclear Labial-expressing polyploid cells by region was performed on Myots-tkvQD intestines from flies moved to 30°C at 24 h APF (Fig. 4D) or moved to 30°C after eclosion (Fig. 4E). Flies with activated BMP signaling during pupation eclosed with large numbers of nuclear Labial-expressing polyploid cells outside of the CCR (Fig. 4D). Consistent with results described for Fig. 4C, the number of nuclear Labial-expressing polyploid cells decreased over time. As expected, Myots only flies (control) moved to 30°C at 24 h APF did not have any nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cells outside of the CCR (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, consistent with results presented in Fig. 1, Myots only or Myots-tkvQD flies moved to 30°C for 8 days post-eclosion lacked any nuclear Labial-positive ployploid cells outside of the CCR (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Enterocytes can be transformed during pupation but do not persist. (A) Myots UAS-tkvQD flies kept at 30°C between 24 h APF and eclosion. One day after eclosion (AE), flies were dissected and stained with Labial antibody. Nuclear Labial was detectable in most of the anterior and parts of the posterior midgut. (A′,A″) Higher magnification of the cells (yellow box in A) in the anterior midgut shows that many cells possess the crescent-shaped morphology characteristic of copper cells and nuclear Labial localization (asterisks). The cup-shaped morphology is observed as a double membrane ring around the cell when captured as a confocal section through the portion of the cell above the ‘base’ of the cup. (B) Myots UAS-tkvQD flies kept at 30°C between 24 h APF and the remainder of the experiment. Adult midgut, three days after eclosion. Nuclear Labial is present in cells in the anterior and the CCR (Cu Region). (B′) α-Spectrin is present in all nuclear Labial-positive cells. The morphology of ectopic labial-positive cells resembles that of endogenous copper cells. (C) At 10 days AE, nuclear Labial staining is no longer present outside of the CCR. (D) Counts of nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cells in the guts of Myots UAS-tkvQD and control Myots flies kept at 30°C between 24 h APF and the time points indicated (days after eclosion). *P<0.05. (E) Counts of nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cells in the guts of Myots UAS-tkvQD and control Myots flies kept at 30°C after eclosion until time points indicated (days after eclosion). There are no significant differences between Myots UAS-tkvQD and control Myots flies (P>0.1). For each image, anterior is to the left.

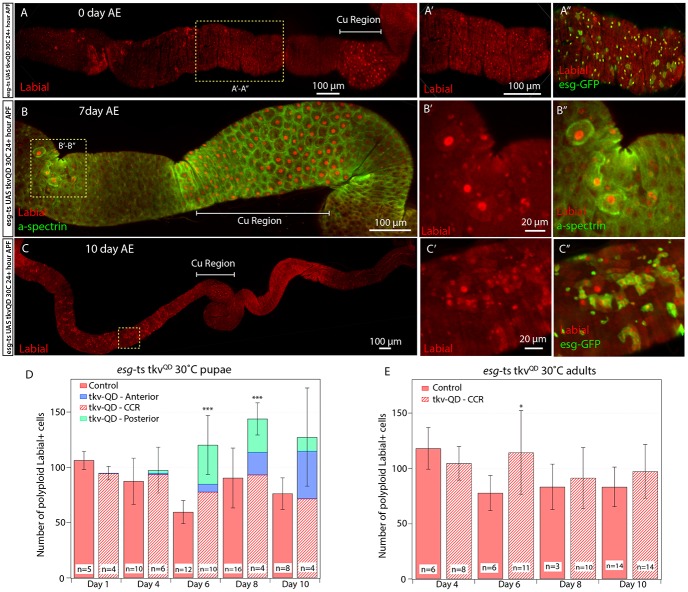

To determine whether esgts could specify pupal ISCs into copper cell stem cells, esgts was crossed to UAS-tkvQD (supplementary material Fig. S2E) and reared at 30°C from 24 h APF until eclosion. Expression of tkvQD starting at 24 h APF resulted in p-Mad staining in the pupal gut one day later, demonstrating efficient activation of the BMP signaling pathway (supplementary material Fig. S2E′). By contrast, esgts-tkvQD flies eclosed with no evidence of ectopic copper cells (Fig. 5A). However, most esg-Gal4-positive ISCs and EBs outside of the CCR expressed nuclear Labial (Fig. 5A-A″). In esgts-tkvQD flies, ectopic nuclear Labial-expressing polyploid cells were first seen in the anterior and posterior midgut starting at 4-5 days after eclosion (Fig. 5B). These cells also expressed high levels of cell membrane-associated α-Spectrin and exhibited the cup-shaped morphology characteristic of copper cells (Fig. 5B-B″). Nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cell number outside of the CCR increased from day 4 to day 10 (Fig. 5C,D). By contrast, consistent with results presented in Fig. 1E, esgts-tkvQD flies moved to 30°C after eclosion failed to produce any nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cells outside of the CCR (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

Esg+ cells are transformed during pupation by BMP signaling activation. (A-A″) esgts UAS-tkvQD were flies kept at 30°C from 24 hours APF and for the remainder of the experiment. Intestine from one day after eclosion (AE) flies. Nuclear Labial is present in the CCR (Cu Region; A) and in esg+ cells (A″). (B-B″) At 7 days AE, multiple polyploid Labial-positive cells are observed. They stain strongly for α-Spectrin and possess copper cell-like morphology. (C-C″) At 10 days AE, polyploid nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cells are present outside the CCR. (D) Counts of nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cells from esgts UAS-tkvQD and esgts control flies kept at 30°C from 24 hours APF until the time indicated (days after eclosion). Starting at day 4 AE, the number of Labial-positive cells in esgts UAS-tkvQD midguts increases in the posterior and anterior midgut. At days 6 and 8 after eclosion, there is a significant difference in number of nuclear Labial-positive cells. ***P<0.005. (E) Counts of Labial-positive polyploid cells in the guts of esgts UAS-tkvQD and control esgts flies kept at 30°C after eclosion until the time points indicated (days after eclosion). Nuclear Labial-positive polyploid cells are present only in the CCR. The number of nuclear Labial-positive cells in the CCR between tkvQD and control flies are similar on all days except for day 6 after eclosion. *P=0.014. For each image, anterior is to the left.

Activation of the BMP signaling pathway in ISCs outside of the CCR during pupation results in the production of cells that exhibit features of copper cell differentiation, suggesting that ISCs have become specified during pupation as copper cell stem cells. To obtain further evidence this was the case, we induced GFP-marked mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) stem cell clones (Wu and Luo, 2006) expressing activators of BMP signaling in pupae or in adults and examined the progeny of marked ISCs for signs of copper cell differentiation.

GFP-marked ISC clones expressing UAS-tkvQD were induced at 24 h APF in pupal ISCs and examined at two later time points: (1) in intestines from adults within 24 h post-eclosion or (2) in intestines from adults 8 days post-eclosion. ISC clones in newly eclosed intestines consisted of one to two GFP cells positive for the ISC marker Delta (supplementary material Fig. S4A-A″), suggesting that in the time between early pupation and eclosion pupal ISCs had undergone one or two divisions. Similar results were obtained with GFP-marked ISC clones expressing only GFP (supplementary material Fig. S4B-B″). In the adult midgut, ISCs are thought to be the only dividing cell in the intestine (Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006). Thus, because ISC clones induced during pupation are one to two cells at eclosion, ISC clones that contain more than two cells at later times must be made up in part of cells that have arisen from ISC divisions during adulthood.

ISC clones from adults, 8 days post-eclosion, contained ISCs, enteroendocrine cells and polyploid cells, all of which were nuclear Labial positive (Fig. 6A-B″). By contrast, when ISC clones expressing UAS-GFP and UAS-tkvQD were induced in 3-day-old adults and examined 8 days later, nuclear Labial was found only in enteroendocrine cells (supplementary material Fig. S5A,A′,B,B′) or in copper cells in the endogenous CCR (supplementary material Fig. S5A″,B″), demonstrating that nuclear Labial localization was dependent on activation of the BMP signaling pathway in pupal ISCs. However, in neither case did stem clones express high levels of α-Spectrin or demonstrate any evidence of copper cell morphology. Thus, BMP pathway activation in pupal ISC clones using an activated form of the tkv receptor results in a partial specification of ISC identity.

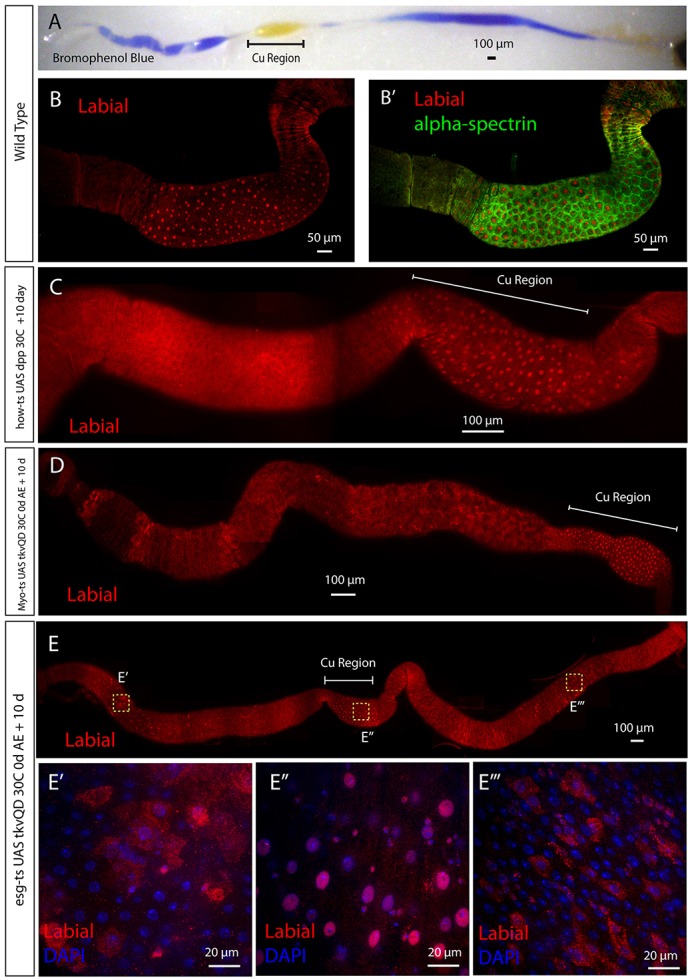

Fig. 6.

Activated BMP signaling clones made during pupation are nuclear Labial positive. (A-B″) MARCM 40A UAS-tkvQD, UAS-GFP 24-48 h APF pupae were heat shocked for 1 hour and allowed to develop to adulthood. Eight days after eclosion, GFP-marked clones (green) within and outside of the CCR contain polyploid, Prospero-positive enteroendocrine (magenta), and Delta-positive (magenta) ISCs (A′,B′) that are nuclear Labial positive (A,B) (red). (A,A′,B,B′) Low magnification views demonstrating that GFP-marked clones (green) within the CCR contain nuclear Labial (red)-positive cells. Clone shown in A,A′,B,B′ is highlighted by a white dotted line. (C-C″) MARCM 40A UAS-dpp, UAS-GFP 24-48 h APF pupae were heat shocked for 1 hour and allowed to develop to adulthood. Eight days after eclosion, polyploid nuclear Labial-positive cells (red) are present in the anterior midgut, both inside (C) and outside of GFP (green) marked clones. (C′,C″) High magnification view of the clone in C demonstrates that high levels of α-Spectrin (magenta) and nuclear Labial (red) are present in cells inside and outside of the clone. (D-D″) MARCM 40A UAS-dpp, UAS-GFP 24-48 h APF pupae were heat shocked for 1 h and their intestines examined 8 days after eclosion. Cells in the outlined clone (D) are nuclear Labial positive (D′) and possess the cup-shaped morphology of copper cells as evident by the increased GFP staining at the cell edges (D″).

ISC clones expressing UAS-GFP and UAS-dpp were also induced at 24 h APF and examined in intestines from adults within 24 h of eclosion or from adults 8 days post-eclosion. As was the case with UAS-tkvQD (Fig. 4A-A″), ISC clones from newly eclosed intestines were also made of one to two GFP cells (supplementary material Fig. S4C,C′). GFP-marked cells outside the CCR were nuclear Labial positive, suggesting that dpp expression had altered their fate (supplementary material Fig. S4C-C″). At 8 days post-eclosion, clones both in and outside of the copper cell region consisted of cells that were nuclear Labial positive (Fig. 6C,C″,D,D′). Furthermore, clones expressed high levels of α-Spectrin (Fig. 6C′,C″) and displayed signs of copper cell morphology (Fig. 6D″). By contrast, when ISC clones expressing UAS-GFP and UAS-dpp were induced in 3-day-old adults and examined 8 days later, clones outside the CCR did not express Labial (supplementary material Fig. S5C,C″) or high levels of α-Spectrin (supplementary material Fig. S5C′). Together, these data argue that BMP signaling pathway activation in pupal ISCs can specify ISCs as copper cell stem cells.

We also noticed that in newly eclosed animals containing ISC clones expressing UAS-GFP and UAS-dpp, unmarked diploid cells near marked clones were also nuclear Labial positive (supplementary material Fig. S4C-C″). In animals containing 8-day-old ISC clones, nearby polyploid cells were present that were immunopositive for nuclear Labial (Fig. 6C,C″,D,D′), expressed high levels of α-Spectrin (Fig. 6C′,C″) and displayed signs of copper cell morphology (Fig. 6D″). Because ectopic expression of dpp in adult ISC clones adults does not result in any evidence of copper cell differentiation (supplementary material Fig. S5C-C″), the presence of unmarked copper cells in these intestines strongly suggests that dpp made by GFP-marked cells can diffuse to neighboring pupal AMPs and ISCs and direct their fate into copper cells and copper cell stem cells.

Injury-induced BMP signaling enhances copper cell fate choice in esgts-tkvQD flies

In esgts-tkvQD flies incubated at 30°C during pupation, the emergence of ectopic copper cells is patchy and more Labial-positive cells arise in the posterior than in the anterior (Fig. 5D). The posterior of the midgut is generally exposed to more damage than the anterior as a consequence of being the main region for nutrient adsorption (Buchon et al., 2009; Marianes and Spradling, 2013). Because BMP signaling antagonizes ISC proliferation (Guo et al., 2013) expression of tkvQD by esgts ISCs might limit the production of new cells by transformed ISCs. Furthermore, if BMP pathway activation is required in non-esg-expressing cells to produce copper cells then injury-induced BMP signals could be rate limiting in regulating the production of new copper cells. To determine whether esgts-tkvQD-transformed stem cells give rise to more ectopic copper cells after injury, we fed 2-day-old flies bleomycin or mock control food for one day and then let them recover for 4 days. The intestines of flies fed bleomycin were filled with large patches of nuclear Labial-expressing cells (Fig. 7A). Many of these cells were polyploid and expressed high levels of α-Spectrin (Fig. 7A′-A‴), consistent with copper cell differentiation. By contrast, mock control-fed flies had small patches of transformed ectopic copper cells (Fig. 7B,B′) similar to that seen in Fig. 5. In addition, bleomycin-fed flies reared at 18°C throughout pupariation and moved to 30°C as adults, showed no evidence of transformation (Fig. 7C,C′), demonstrating that, as previously reported (Guo et al., 2013), bleomycin injury by itself does not result in ectopic production of copper cells. Thus, although stem cells in the adult midgut are resistant to re-specification by injury-induced BMP signaling, ISCs that have received a BMP signal during pupation can respond to the injury-induced BMP signal and produce ectopic copper cells along the entire length of the midgut.

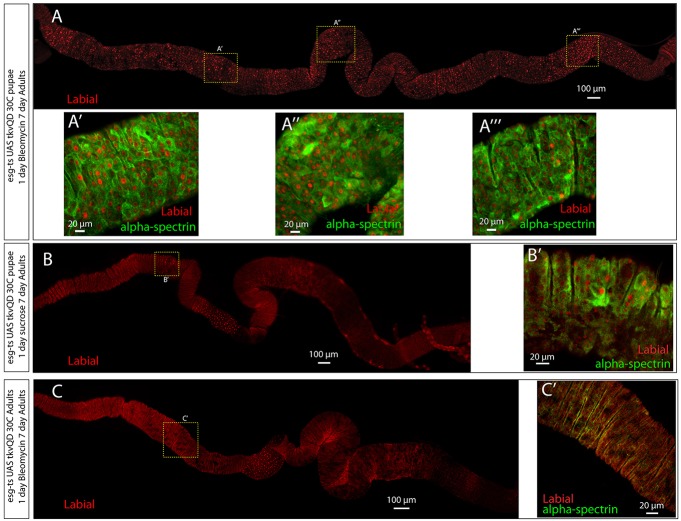

Fig. 7.

Injury induces production of copper cells from pupally transformed ISCs. (A-A‴) esgts UAS-tkvQD flies were kept at 30°C from 24 h APF onwards. One day after eclosion, they were fed bleomycin in sucrose solution for 24 h and then kept on cornmeal food until day 7. The entire midgut is filled with nuclear Labial cells. Some are small and not fully differentiated whereas others are polyploid, possess copper cell morphology, and are strongly positive for α-Spectrin (A′,A″) similar to cells in the CCR (A″). (B,B′) esgts UAS-tkvQD flies kept at 30°C from 24 h APF onwards. One day after eclosion, they were fed sucrose solution for 24 h and kept on normal food until dissection at day 7. A cluster of cells, outside of the CCR, is nuclear Labial positive and strongly positive for α-Spectrin. (C,C′) esgts UAS-tkvQD flies moved from 18°C to 30°C at the start of eclosion. One day after eclosion, they were fed bleomycin in sucrose solution for 24 h and transferred to cornmeal food until dissection at day 7. Cells outside of the CCR are nuclear Labial negative and weakly positive for α-Spectrin. For each image, anterior is to the left.

DISCUSSION

Recently, two research groups have shown that the Drosophila adult midgut is made up of 10-14 regions, each of which are maintained by ISCs that give rise to differentiated cells with unique morphological and physiological properties (Buchon et al., 2013; Marianes and Spradling, 2013). The presence of multiple regions with sharp boundaries suggests that each region is supported by a set of ISCs that are intrinsically specific for that region. However, it is equally possible that ISCs along the length of the midgut are not intrinsically different and that regional variation in the midgut is encoded in signals differentially expressed in the surrounding muscle, trachea and/or nerves. Indeed, recent work by Li et al. suggests that BMP signaling in the adult is sufficient to specify copper cell identity (Li et al., 2013) and that the boundaries of the CCR are strictly dependent on the domain of BMP signaling ligand expression. Using a set of more stringent criteria (nuclear Labial, α-Spectrin levels, copper cell morphology), we find that this is not the case. Rather, our work demonstrates that in the Drosophila intestine, a mixture of intrinsic specification and response to local signals is required for normal tissue homeostasis. Copper cell ISCs are specified during pupation and this specification restricts the ability of copper cell ISCs and their daughters to respond to local signals in the adult (supplementary material Fig. S6). This allows for the iterative refinement of identity and for the use of the same signals in the adult for different purposes (Guo et al., 2013). Furthermore, we have previously shown that under conditions of injury in the adult Dpp is released from the muscle and that BMP signaling can be activated locally throughout the midgut to antagonize ISC proliferation (Guo et al., 2013). It is clear that the activity of BMP signaling in the adult does not result in transformation of cells outside the CCR into copper cells as they are maintained solely in that region (Guo et al., 2013; Strand and Micchelli, 2011). The same Dpp signal that is insufficient for transformation during adulthood is sufficient during a defined time during metamorphosis. Although our data support the model that copper stem cells are a unique type of ISC, it is still unclear whether this is the case for ISCs that maintain the midgut outside the CCR. Future identification of signals required for regional daughter differentiation should help to resolve this issue.

Ectopic induction of BMP signaling during pupation fails to transform parts of the anterior and the posterior midgut. The presence of regions that cannot be altered implies that there are one or more other signals working in conjunction with BMP signaling to allow or repress transformation. Given that the dpp and wg signaling pathways cooperatively regulate labial expression during development (Bilder et al., 1998; Hoppler and Bienz, 1995; Tanaka et al., 2007) and that wg signaling is required for adult copper cell maintenance (Strand and Micchelli, 2011), wg signaling is a likely candidate. In addition the regions of active Wnt (Wg) signaling shown by Buchon et al. (Buchon et al. 2013) match well with the regions of labial induction under conditions of pupal dpp induction. Further work is needed to explore whether Wnt signaling cooperates with dpp to specify copper cell identity during pupation or possibly promotes direct transformation in the adult.

During their characterization of the adult midgut, Marianes and Spradling found that although epithelial gene expression correlated well with regional boundaries, expression of genes in muscle did not (Marianes and Spradling, 2013). Even though the sample set examined was small (n=8), given our results this is not surprising. Signals mediating ISC identity need only be precisely expressed during the crucial period of ISC specification. After such time the expression pattern of these signals might remain stable or dramatically change to reflect the evolving developmental and physiological needs of the tissue. Thus, our study illustrates that a complete understanding of how tissue heterogeneity is established and maintained depends also on identifying and characterizing signals in both adult and early development.

The vertebrate intestine, like the Drosophila midgut, is highly regionalized in form and function (Yasugi and Mizuno, 2008). Mammalian intestines are maintained by multiple cell types all of which arise from stem cells located in the base of the crypt (van der Flier and Clevers, 2009). Although not currently feasible with Drosophila ISCs, it is possible to culture single vertebrate ISCs and grow out mini crypts that contain all of the differentiated cells of the intestine (Sato and Clevers, 2013). Based on our results, we would speculate that ISCs isolated from adult intestines will give rise to organoid crypts made up of cells that reflect their region of origin. Our work also suggests that there might exist a time in development when vertebrate ISCs are plastic. In such an event, it should be possible to combine the knowledge gleaned from the Drosophila and vertebrate systems to improve our understanding of and even control stem cell plasticity for use in regenerative therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly genetics

All Drosophila experimental stocks and crosses were cultured with daily changes of standard cornmeal with molasses food with live yeast at 23-25°C unless otherwise noted in the text.

Fly stocks

esg-Gal4 UAS-GFP; esg-Gal4 UAS-GFP tub-Gal80ts/CyO (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006); tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/CyO, Myo1A-Gal4 (Jiang et al., 2009); UAS-tkv RNAi (V#3059); y w hs-flp UAS-GFP, tub-Gal80 FRT40A, tub-Gal4/TM6B, Tb; UAS-tkvQD (Wiersdorff et al., 1996); FRT40A/CyO, UAS-tkvQD/TM6B (Wu and Luo, 2006); UAS-dpp::GFP (Crickmore and Mann, 2006).

Immunohistochemistry and microscopy

All samples were dissected in 2× gut buffer (200 mM glutamic acid, 50 mM KCl, 40 mM MgSO4, 4 mM sodium phosphate monobasic, 4 mM sodium phosphate dibasic, 2 mM MgCl2) (Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006) and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 1 h. Subsequent washes and antibody stains were carried out in PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% Triton X-100. Primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-β-gal at 1:10,000 (55978, Cappel); guinea pig anti-pMAD at 1:1000 (Guo et al., 2013); guinea pig anti-Labial at 1:5000 (Guo et al., 2013); chicken anti-GFP at 1:10,000 (13970, Abcam); mouse anti-Prospero at 1:100 [MR1A, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)]; mouse anti-Delta at 1:100 (C594.9B, DSHB); mouse anti-α-Spectrin at 1:100 (3A9, DSHB). Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were used at 1:4000 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). Guts were stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) (Sigma), mounted in 70% glycerol, imaged with a spinning disc confocal microscope (Olympus DSU) and analyzed using Slidebook software (version 4.2).

Bromophenol Blue dye feeding

A 1 ml solution of 0.15% Bromophenol Blue (Dubreuil et al., 1998) was added to 0.5 g of dry yeast resulting in a yeast paste. Animals were fed this paste for 5-8 h, midguts were dissected, and analyzed as described in the text.

Bleomycin feeding

Chromatography paper (Fisherbrand; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was cut into 3.7×5.8 cm strips and saturated with 25 µg/ml bleomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 5% sucrose. Flies were kept in otherwise empty vials with bleomycin or sucrose only for the time indicated.

Pupae collections on temperature shifts

For Gal80ts and MARCM experiments, crosses were carried out at 18°C and pupae were collected every 24 h by clearing all pupae and transferring them to a new vial. The pupae were kept at 18°C until they were exposed to heat shock (MARCM) or moved to 30°C (Gal80ts).

Cell counting and statistics

Images were exported from Slidebook (version 4.2) and stitched together in Fiji, using the stitching plugin develop by Preibisch et al. (Preibisch et al., 2009). Whole-gut images were used to manually count all non-diploid cells with strong nuclear Labial staining in Metamorph (Molecular Devices Version 7.6.2). Error bars represent one standard deviation. n represents the number of whole guts counted. P-values were computed using Student's t-test with two-tailed distribution and two-sample unequal variance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ed Laufer, Richard Mann and Gary Struhl for reagents; and members of the Ohlstein Lab for helpful comments during the course of the project.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

I.D. carried out experiments. I.D. and B.O. carried out data analysis, conceived the study, designed and coordinated experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

I.D. was supported in part by a Columbia University Medical Training grant [5-T32-HD055165-01]. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant [R01 DK082456-01 to B.O.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.104018/-/DC1

References

- Bilder D., Graba Y., Scott M. (1998). Wnt and TGFbeta signals subdivide the AbdA Hox domain during Drosophila mesoderm patterning. Development 125, 1781-1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N., Broderick N. A., Poidevin M., Pradervand S., Lemaitre B. (2009). Drosophila intestinal response to bacterial infection: activation of host defense and stem cell proliferation. Cell Host Microbe 5, 200-211 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N., Osman D., David F. P. A., Yu Fang H. Y., Boquete J.-P., Deplancke B., Lemaitre B. (2013). Morphological and molecular characterization of adult midgut compartmentalization in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 3, 1725-1738 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M. F., Fuller M. (2006). Stem cells and cancer: two faces of eve. Cell 124, 1111-1115 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crickmore M. A., Mann R. (2006). Hox control of organ size by regulation of morphogen production and mobility. Science 313, 63-68 10.1126/science.1128650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil R. R. (2004). Copper cells and stomach acid secretion in the Drosophila midgut. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36, 742-752 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil R. R., Maddux P. B., Grushko T. A., Macvicar G. (1997). Segregation of two spectrin isoforms: polarized membrane-binding sites direct polarized membrane skeleton assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1933-1942 10.1091/mbc.8.10.1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil R. R., Frankel J., Wang P., Howrylak J., Kappil M., Grushko T. A. (1998). Mutations of alpha spectrin and labial block cuprophilic cell differentiation and acid secretion in the middle midgut of Drosophila larvae. Dev. Biol. 194, 1-11 10.1006/dbio.1997.8821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil R., Grushko T., Baumann O. (2001). Differential effects of a labial mutation on the development, structure, and function of stomach acid-secreting cells in Drosophila melanogaster larvae and adults. Cell Tissue Res. 306, 167-178 10.1007/s004410100422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filshie B. K., Poulson D. F., Waterhouse D. F. (1971). Ultrastructure of the copper-accumulating region of the Drosophila larval midgut. Tissue Cell 3, 77-102 10.1016/S0040-8166(71)80033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier L. G., Clevers H. (2009). Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 241-260 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Driver I., Ohlstein B. (2013). Injury-induced BMP signaling negatively regulates Drosophila midgut homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 201, 945-961 10.1083/jcb.201302049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein A., Rugendorff A., Tepass U., Hartenstein V. (1992). The function of the neurogenic genes during epithelial development in the Drosophila embryo. Development 116, 1203-1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppler S., Bienz M. (1994). Specification of a single cell type by a Drosophila homeotic gene. Cell 76, 689-702 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppler S., Bienz M. (1995). Two different thresholds of wingless signalling with distinct developmental consequences in the Drosophila midgut. EMBO J. 14, 5016-5026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Rosenfeld M. G. (2012). Epigenetic regulation of human embryonic stem cells. Front. Genet. 3, 238 10.3389/fgene.2012.00238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immerglück K., Lawrence P. A., Bienz M. (1990). Induction across germ layers in Drosophila mediated by a genetic cascade. Cell 62, 261-268 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90364-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Edgar B. A. (2009). EGFR signaling regulates the proliferation of Drosophila adult midgut progenitors. Development 136, 483-493 10.1242/dev.026955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Patel P. H., Kohlmaier A., Grenley M. O., McEwen D. G., Edgar B. A. (2009). Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell 137, 1343-1355 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Qi Y., Jasper H. (2013). Dpp signaling determines regional stem cell identity in the regenerating adult drosophila gastrointestinal tract. 4, 10-18 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.040 Cell Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G., Xu N., Xi R. (2008). Paracrine Wingless signalling controls self-renewal of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. Nature 455, 1119-1123 10.1038/nature07329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann R. S., Abu-Shaar M. (1996). Nuclear import of the homeodomain protein extradenticle in response to Wg and Dpp signalling. Nature 383, 630-633 10.1038/383630a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marianes A., Spradling A. C. (2013). Physiological and stem cell compartmentalization within the Drosophila midgut. eLife 2, e00886 10.7554/eLife.00886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur D., Bost A.,, Driver I., Ohlstein B. (2010). A transient niche regulates the specification of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. Science 327, 210-213 10.1126/science.1181958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken K. W., Wells J. M. (2012). Molecular pathways controlling pancreas induction. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 656-662 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli C. A., Perrimon N. (2006). Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature 439, 475-479 10.1038/nature04371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli C. A., Sudmeier L., Perrimon N., Tang S., Beehler-Evans R. (2011). Identification of adult midgut precursors in Drosophila. Gene Expr. Patterns 11, 12-21 10.1016/j.gep.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein B., Spradling A. (2006). The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature 439, 470-474 10.1038/nature04333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preibisch S., Saalfeld S., Tomancak P. (2009). Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics 25, 1463-1465 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowitch D. H., Kriegstein A. R. (2010). Developmental genetics of vertebrate glial-cell specification. Nature 468, 214-222 10.1038/nature09611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Clevers H. (2013). Growing self-organizing mini-guts from a single intestinal stem cell: mechanism and applications. Science 340, 1190-1194 10.1126/science.1234852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand M., Micchelli C. A. (2011). Quiescent gastric stem cells maintain the adult Drosophila stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17696-17701 10.1073/pnas.1109794108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima S., Adams K. L., Ortiz P. A., Ying C. T., Moridzadeh R., Younossi-Hartenstein A., Hartenstein V. (2011a). Development of the Drosophila entero-endocrine lineage and its specification by the Notch signaling pathway. Dev. Biol. 353, 161-172 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima S., Younossi-Hartenstein A., Ortiz P. A., Hartenstein V. (2011b). A novel tissue in an established model system: the Drosophila pupal midgut. Dev. Genes Evol. 221, 69-81 10.1007/s00427-011-0360-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima S., Paul M., Aghajanian P., Younossi-Hartenstein A., Hartenstein V. (2013). Migration of Drosophila intestinal stem cells across organ boundaries. Development 140, 1903-1911 10.1242/dev.082933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka R., Takase Y., Kanachi M., Enomoto-Katayama R., Shirai T., Nakagoshi H. (2007). Notch-, Wingless-, and Dpp-mediated signaling pathways are required for functional specification of Drosophila midgut cells. Dev. Biol. 304, 53-61 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet P., Wu S. M., Zaffran S., Pucéat M. (2012). Early cardiac development: a view from stem cells to embryos. Cardiovasc. Res. 96, 352-362 10.1093/cvr/cvs270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersdorff V., Lecuit T., Cohen S. M., Mlodzik M. (1996). Mad acts downstream of Dpp receptors, revealing a differential requirement for dpp signaling in initiation and propagation of morphogenesis in the Drosophila eye. Development 122, 2153-2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. S., Luo L. (2006). A protocol for mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) in Drosophila. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2583-2589 10.1038/nprot.2006.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasugi S., Mizuno T. (2008). Molecular analysis of endoderm regionalization. Dev. Growth Differ. 50 Suppl. 1, S79-S96 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.00984.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.