Abstract

Objective

To describe and to determine the feasibility of a patient-specific academic detailing (PAD) smoking cessation (SC) program in a primary care setting.

Design

Descriptive cohort feasibility study.

Setting

Hamilton, Ont.

Participants

Pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and their patients.

Interventions

Integrated pharmacists received basic academic detailing training and education on SC and then delivered PAD to prescribers using structured verbal education and written materials. Data were collected using structured forms.

Main outcome measures

Five main feasibility criteria were generated based on Canadian academic detailing programs: PAD coordinator time to train pharmacists less than 40 hours; median time of SC education per pharmacist less than 20 hours; median time per PAD session less than 60 minutes for initial visit; percentage of prescribers receiving PAD within 3 months greater than 50%; and number of new SC referrals to pharmacists at 6 months more than 10 patients per 1.0 full-time equivalent (FTE) pharmacist (total of approximately 30 patients).

Results

Eight pharmacists (5.8 FTE) received basic academic detailing training and education on SC PAD. Forty-eight physicians and 9 nurse practitioners consented to participate in the study. The mean PAD coordinator training time was 29.1 hours. The median time for SC education was 3.1 hours. The median times for PAD sessions were 15 and 25 minutes for an initial visit and follow-up visit, respectively. The numbers of prescribers who had received PAD at 3 and 6 months were 50 of 64 (78.1%) and 57 of 64 (89.1%), respectively. The numbers of new SC referrals at 3 and 6 months were 11 patients per FTE pharmacist (total of 66 patients) and 34 patients per FTE pharmacist (total of 200 patients), respectively.

Conclusion

This study met the predetermined feasibility criteria with respect to the management, resources, process, and scientific components. Further study is warranted to determine whether PAD is more effective than conventional academic detailing.

Résumé

Objectif

Décrire un programme de formation continue en pharmacothérapie spécifique au patient (FPSP) pour la cessation du tabagisme (CT) et en déterminer la faisabilité dans un milieu de soins primaires.

Type d’étude

Étude de cohorte descriptive sur la faisabilité.

Contexte

Hamilton, en Ontario.

Participants

Des pharmaciens, des médecins, des infirmières praticiennes et leurs patients.

Interventions

Un groupe intégré de pharmaciens a suivi une formation de base en pharmacothérapie et un programme d’éducation en CT, puis a présenté cette même formation aux prescripteurs sous forme verbale structurée et à l’aide de matériel écrit. Les données ont été recueillies au moyen de formulaires structurés.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

On a élaboré cinq principaux critères de faisabilité en se fondant sur les programmes de formation continue en pharmacothérapie canadiens: moins de 40 heures consacrées par le coordonnateur du programme de FPSP pour former les pharmaciens; moins de 20 heures en moyenne par pharmacien pour la formation en CT; moins de 60 minutes en moyenne par séance de FPSP pour la visite initiale; plus de 50 % des prescripteurs suivant un programme de FPSP dans un délai de 3 mois; et un nombre supérieur à 10 nouveaux patients par 1,0 pharmacien équivalent temps plein (ETP) envoyés en consultation pour CT (total d’environ 30 patients).

Résultats

Huit pharmaciens (5,8 ETP) ont reçu une formation en pharmacothérapie continue de base et ont suivi un programme d’éducation en CT. Quarante-huit médecins et 9 infirmières praticiennes ont consenti à participer à l’étude. Le coordonnateur du programme de FPSP a consacré en moyenne 29,1 heures pour la formation. La durée moyenne pour la formation en CT était de 3,1 heures. La visite initiale et celle de suivi pour les séances du FPSP duraient respectivement 15 et 25 minutes. Les nombres de prescripteurs ayant suivi la FPSP à 3 et à 6 mois se situaient à 50 sur 64 (78,1 %) et à 57 sur 64 (89,1 %) respectivement. Les nombres de nouvelles demandes de consultation en CT à 3 et à 6 mois s’élevaient respectivement à 11 patients par pharmacien ETP (total de 66 patients) et à 34 patients par pharmacien ETP (total de 200 patients) respectivement.

Conclusion

Cette étude a satisfait aux critères de faisabilité prédéterminés en ce qui concerne la gestion, les ressources, le processus et les composantes scientifiques. Des études plus approfondies s’imposent pour déterminer si la FPSP est plus efficace que la formation continue en pharmacothérapie conventionnelle.

Patient-specific academic detailing (PAD) is a new model developed in Hamilton, Ont, that combines 2 professional services: academic detailing and pharmacist clinical services in a family practice setting. Academic detailing is a method of continuing medical education in which knowledgeable, trained health professionals meet with prescribers in their practice settings to provide one-on-one evidence-based information.1 One of the main goals of academic detailing programs is to provide well-balanced, objective medication information without influence from pharmaceutical companies. Thus, pharmacists are often chosen as academic detailers given their expertise in drug therapy. Academic detailing has been shown to be one of the most effective methods to improve how medications are prescribed and used2,3; studies have examined academic detailing for prescribing antibiotics,4–7 antidepressants,8 benzodiazepines,9–12 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,13,14 and diuretics for hypertension.15 Academic detailing has also been used to target behaviour related to the provision of smoking cessation (SC) advice.16–22

Despite the proven benefits of academic detailing in optimizing prescribing practices, there are a number of limitations and barriers that might prevent physicians from participating in academic detailing services.23,24 These include difficulty in scheduling office time, physician preference for accessing continuing medical education in other ways, and the perception that a considerable amount of time is required for academic detailing sessions.23,24 In addition, as academic detailers might only see prescribers intermittently, the relationship between prescribers and academic detailers might take some time to develop.

Patient-specific academic detailing was developed to offset some of the limitations of academic detailing and promote pharmacists’ services in family health teams (FHTs) in Hamilton. In primary care, pharmacists are integrated within practices as consultants to review patients’ medications, identify drug-related issues, and review cases or make recommendations to family physicians. The strong collaborative working relationship between physicians and pharmacists was already established before the PAD sessions through their shared clinical experiences.

In PAD, a trained pharmacist integrated within the primary care team provides the general messages used in conventional academic detailing encounters and situates these messages within case examples to promote better prescribing. The term patient-specific is used because the academic detailing message is tailored for the prescribers by using real case examples from their practices. Physicians and pharmacists can discuss the application of new information to their patients.

Although PAD has theoretical advantages, it has not been formally evaluated. As separate components, both academic detailing and integration of pharmacists in primary care have demonstrated improvements in medication prescribing.2,25–27 The objective of this project was to determine the feasibility of PAD in a primary care setting.

METHODS

The main outcome measures to determine if PAD by primary care pharmacists to prescribers was feasible were number and percentage of prescribers detailed within 3 and 6 months; time for pharmacists to be trained in SC academic detailing; time for a PAD session; time for the PAD coordinator to train the pharmacists; and number of new patient referrals by the prescribers for SC at 3 and 6 months. This was a descriptive cohort feasibility study in 2 primary care–based FHTs consisting of approximately 139 physicians, 10 nurse practitioners (NPs), 250 000 patients, and 5.8 full-time equivalent (FTE) pharmacists. One FHT is a community FHT with more than 40 different clinical sites and the other is an academic FHT with 2 different sites. In the community FHT, approximately 20 of the sites have pharmacists integrated within the offices. At these sites, pharmacists see patients for 30 to 60 minutes to review medications and discuss drug-related issues with the prescribers. On average, pharmacists work in the clinics for at least half a day per week per family physician. In the academic FHT, there are approximately 15 family physicians per 1.0 FTE pharmacist. Pharmacists are responsible for teaching residents, and provide group and individual patient education. On average, pharmacists work 2 days per week per site.

Pharmacists integrated within the FHTs who were willing to be trained in academic detailing and FHT family physicians and NPs who were already working collaboratively with integrated pharmacists and who were willing to receive academic detailing services were included in this study.

The intervention included 3 components: a training workshop on basic academic detailing, education on SC content, and PAD sessions with the FHT prescribers.

Academic detailing basic training workshop

All pharmacists participated in a 3.5-day basic academic detailing workshop led by a world expert in academic detailing and facilitated by members of the Canadian Academic Detailing Collaboration. Two weeks before the workshop, readings28–37 were sent to the participants. The workshop included didactic lectures and role playing to teach the basic skills and knowledge required for effective academic detailing sessions. The program content included an overview of academic detailing, structure for academic detailing visits, introductions to academic detailing visits, physicians speaking about the pressures of current practice, discussion of trust and credibility, getting clear objectives and preparing key messages, management and use of detailing aids, challenging responses, closing the communication loop, preparing for a complete academic detailing visit, and a “live” visit. At the end of the workshop, each participant performed a detailing visit for management of sore throat that was videorecorded for self-assessment.

Pharmacist SC training

Smoking cessation reading materials38–41 were provided to the pharmacists 2 weeks before the SC training session. At the training session, the pharmacists were provided with a summary of the reading materials via PowerPoint presentation and handouts. The academic detailing–trained pharmacists reviewed an evidence-based, 2-page SC handout (created by the RxFiles program) that was to be given to the prescribers.42 Five key messages were emphasized: that caution should be used when prescribing varenicline for patients with psychiatric disorders; that combination therapy of bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy might be considered; that nicotine inhalers and lozenges are available in Canada; that nortriptyline can be used for SC; and that patients should be referred to pharmacists for SC therapy. Each pharmacist practised academic detailing of SC with his or her colleagues.

The SC training was conducted by the academic detailing coordinator (M.J.)—a pharmacist with a doctorate in pharmacy and previous experience and training in academic detailing from the RxFiles program in Saskatoon, Sask. The academic detailing coordinator organized the basic academic detailing workshop, selected the topic, provided the SC training session materials, identified the key messages, and provided the SC education.

Patient-specific academic detailing session with prescribers

Pharmacists were encouraged to book 20-minute one-on-one sessions with each prescriber in their practices to review the 5 key SC messages and discuss the messages in relation to an actual patient in the prescriber’s practice. Patients were identified by chart audits or specific cases that prescribers or pharmacists recalled during the academic detailing discussion.

Patients were referred to pharmacists for SC counseling after being identified through chart audits, during regular appointments (that were not necessarily for SC), or after calling to book appointments for SC. Smoking cessation counseling comprised a 30- to 60-minute appointment between the pharmacist and the patient, during which the pharmacist provided the risks and benefits of each SC product and helped the patient choose a product. Pharmacists also consulted the prescriber regarding therapeutic recommendations for SC, and followed up with each patient and prescriber as required. Pharmacists noted patients’ progress in their medical charts during each visit.

Pharmacists documented how many patients were referred to them for SC counseling by each physician by counting the number of patients referred using the clinic appointment schedule. The total number of referrals per pharmacist was collected by the coordinator at 3 and 6 months.

The main outcomes of the study were based on 4 recognized categories deemed useful to examine when planning feasibility or large-scale studies: processes employed, resources used, management considerations, and scientific metrics.43 The main outcomes were the number and percentage of prescribers who received PAD within 3 and 6 months (processes); average time for pharmacists to be trained in SC detailing (resources); average time for a PAD session (resources); time for the academic detailing coordinator to train the pharmacists (management); and number of new patient referrals by prescribers for SC counseling at 3 and 6 months after the PAD session (scientific). The feasibility criteria were based on an overview of Canadian academic detailing programs.44

Secondary outcomes were the comparison of new patient referrals to pharmacists for SC counseling 6 months before and 6 months after the PAD session; administrative time; location and type of PAD encounter; and tools used (eg, RxFiles handout, PowerPoint presentation, e-mail updates).

This feasibility study aimed for a sample of approximately 20 prescribers; it was expected that this sample size would provide a reasonable opportunity to assess success of the main outcomes. Formal samplesize calculations for prescribers and patients were not carried out.43

Data were collected prospectively by the pharmacists and the academic detailing coordinator using structured data collection forms as part of a quality assurance program. Retrospective data collection was conducted to obtain data required to measure the main outcomes. The coordinator also met with each pharmacist to collect any missing data. Data were analyzed using appropriate descriptive statistics: means and SDs or medians and minimum and maximum values for continuous variables, and counts (percentages) for categorical variables.

This study was approved by the McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

Characteristics of participants

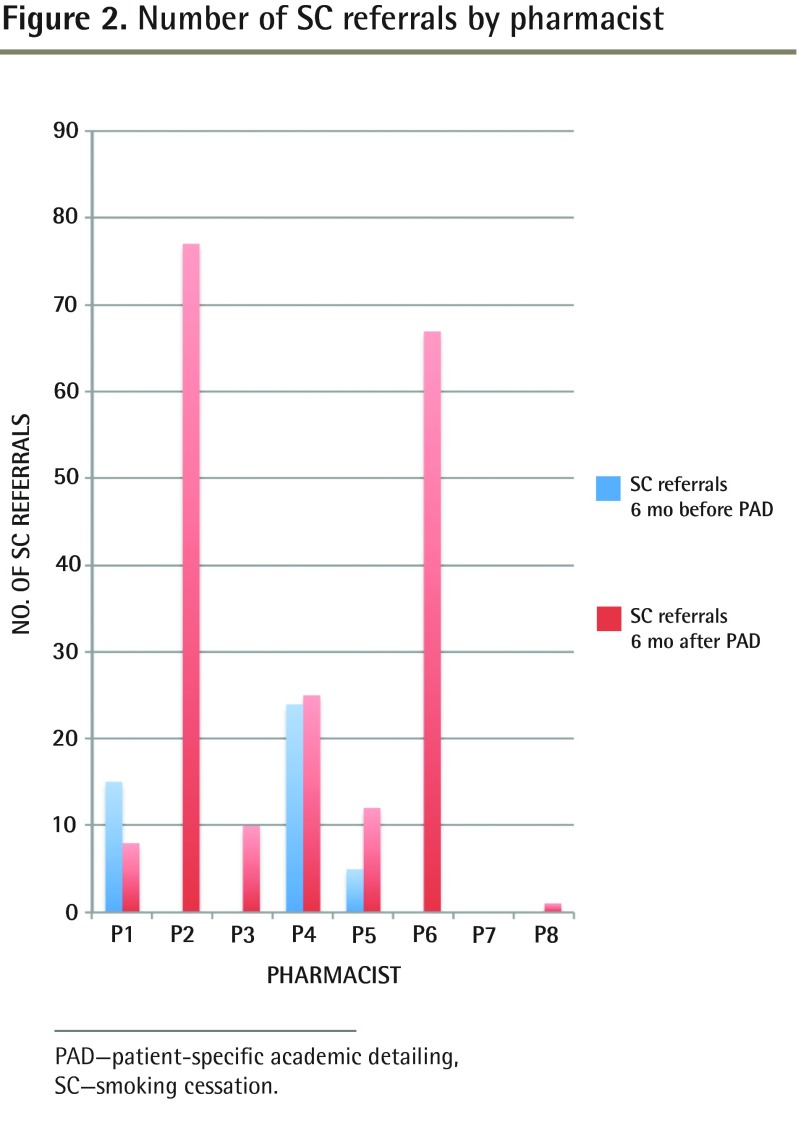

All pharmacists (n = 8; 5.8 FTE) and 57 of 64 eligible prescribers consented to participate in the study (Figure 1, Table 1, and Table 2). Within 4 months of attending the basic academic detailing workshop, all pharmacists were trained in SC education and PAD.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant inclusion

FHT—family health team, NP—nurse practitioner.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pharmacists

| CHARACTERISTIC | VALUE |

|---|---|

| No. of pharmacists | 8 |

| Total FTE (minimum, maximum) | 5.8 (0.2, 1.0) |

| Highest level of education completed | |

| • No. with a doctorate of pharmacy | 3 |

| • No. with a bachelor of science in pharmacy | 5 |

| Sex | |

| • No. of men | 1 |

| • No. of women | 7 |

| Years practising as a pharmacist, median (minimum, maximum) | 19 (6, 35) |

| Years practising in an FHT, median (minimum, maximum) | 1.0 (0.4, 2.5) |

| No. of physicians per pharmacist, median (minimum, maximum) | 7 (3, 11) |

| No. of NPs per pharmacist, median (minimum, maximum) | 1.5 (0, 2) |

FHT—family health team, FTE—full-time equivalent, NP—nurse practitioner.

Table 2.

Characteristics of prescribers

| CHARACTERISTICS | FPs | NPs |

|---|---|---|

| No. of prescribers | 48 | 9 |

| Years since graduation, mean (minimum, maximum; SD) | 25 (6, 46; 9.5) | 7 (1, 13; 4.4) |

| Sex | ||

| • Male | 25 | 1 |

| • Female | 23 | 8 |

NA—not available, NP—nurse practitioners.

Data represent FPs and NPs who gave consent.

Table 3 summarizes the results and analysis of the main outcomes.

Table 3.

Results and analysis of main feasibility outcomes

| MAIN FEASIBILITY OUTCOMES | RESULTS | CRITERIA FOR SUCCESS | WERE CRITERIA FOR SUCCESS MET? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescribers had PAD sessions within 3 and 6 mo | 3 mo: 50 of 64 (78.1%) 6 mo: 57 of 64 (89.1%) |

3 mo: > 50% 6 mo: > 70% |

Yes |

| Median time for education | Total: 3.1 h (minimum 1.7, maximum 6.2) | < 20 h | Yes |

| Median time for PAD sessions | Initial visit: 15 min (minimum 5, maximum 60) | Initial visit: < 60 min Follow-up visit: < 30 min | Yes |

| Follow-up visit: 25 min (only 1 follow-up visit recorded) | |||

| Total time for the PAD coordinator to train pharmacists | 29.1 h | < 40 h | Yes |

| No. of new patient referrals by prescribers for SC counseling at 3 and 6 mo after initial PAD sessions | 3 mo: 11 patients per 1.0 FTE pharmacist (total 66 patients) 6 mo: 34 patients per 1.0 FTE pharmacist (total 200 patients) Minimum 0, maximum 77 | 3 mo: 5 patients per 1.0 FTE pharmacist (total 29 patients) 6 mo: 10 patients per 1.0 FTE pharmacist (total 58 patients) | Yes |

FTE—full-time equivalent, PAD—patient-specific academic detailing, SC—smoking cessation.

Processes employed

Pharmacists held their first PAD sessions during a 6-month period. At 3 and 6 months after the first PAD session, 42 of 54 (77.8%) physicians and 8 of 10 (80.0%) NPs, and 48 of 54 (88.9%) physicians and 9 of 10 (90.0%) NPs, respectively, had received PAD on SC.

Resources used

The median time for pharmacists to read the SC education package was 1 hour (n = 7 pharmacists; minimum 1 hour, maximum 3 hours). The PAD training session included a PowerPoint presentation (1 hour) and observing a mock PAD session (30 minutes). One pharmacist was unable to attend and received training via e-mail and telephone. Two of 7 pharmacists reported completing additional research to supplement the provided SC educational materials (1 and 2 hours of additional readings, respectively).

Management considerations

The PAD coordinator prepared the reading package38–41 (1 hour), handouts (1 hour), and key messages (6 hours); updated the RxFiles handout (2 hours); reviewed additional research (eg, attended local continuing education events; reviewed MEDLINE, Health Canada, and US Food and Drug Administration resources) (6 hours); provided SC PAD training (3 hours); updated the pharmacists via e-mail (5 minutes); and completed 10 hours of PAD training to the pharmacists for a total workload of 29.1 hours.

Scientific metrics

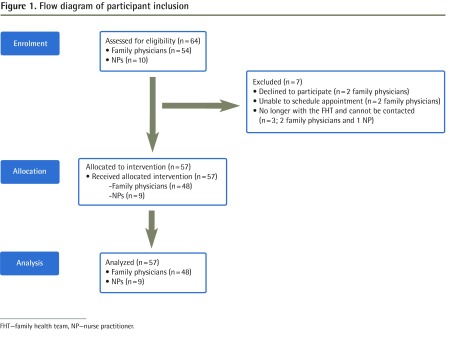

Overall, 6 months after the SC PAD sessions, there were 200 referrals to pharmacists for SC: the number of referrals per pharmacists ranged from 0 to 77 (Figure 2). One pharmacist did not receive any referrals, as the clinic decided to refer the patients to the NP for SC counseling (n = 3 patients referred).

Figure 2.

Number of SC referrals by pharmacist

PAD—patient-specific academic detailing, SC—smoking cessation.

Secondary outcomes

Six months before the PAD sessions, 5 of 8 pharmacists (62.5%) had no SC referrals (Figure 2). Most of the PAD encounters occurred in the physicians’ offices (42 of 57, 73.7%), most were one-on-one (46 of 57, 80.7%), and all used the RxFiles handout. The median times for discussion with each prescriber and for administrative tasks were 15 minutes (minimum 5, maximum 60) and 25 minutes (minimum 5, maximum 60), respectively.

DISCUSSION

The results from the study demonstrate that PAD is feasible with respect to the process, resources, management, and scientific components considered to implement and evaluate the intervention. Compared with other existing Canadian academic detailing programs, there was a higher participation rate among prescribers and similar administration times for the PAD coordinator and pharmacists.44 The high number of referrals to the pharmacists for SC after the provision of PAD shows that PAD might be a promising approach that moves beyond knowledge transmission to use existing clinical relationships and changes to processes within the practice setting to stimulate substantial behaviour changes. In PAD, pharmacists in primary care might also require less administrative time compared with conventional academic detailers, as there is less travel to offices and no waiting time in offices.

Although the clinical effect of SC counseling is not examined in this study, more referrals for specific SC activities increase the potential for more patients to quit smoking. Patients who receive brief advice on SC from their physicians are more likely to quit smoking compared with those who receive usual care (relative risk 1.66, 95% CI 1.42 to 1.94).45 More intensive interventions by physicians produced a higher quit rate in patients than usual care did (relative risk 1.84, 95% CI 1.60 to 2.13).45 Patient-specific academic detailing might enhance SC rates, as both prescribers and pharmacists are actively assisting patients with SC. Ideally, at all visits prescribers would ask patients whether they smoked and whether they wanted to quit. If patients indicated they wanted to quit, then prescribers would refer patients to pharmacists for initial SC counseling visits. Pharmacists would consult the prescribers regarding SC medication prescriptions and follow up with patients and prescribers as required.

Limitations

Some limitations of this study include recall and selection bias. While most of the data were collected prospectively as part of a quality assurance program, some of the training times for pharmacist and physician encounters were collected retrospectively. Selection bias might be present, as this feasibility study was completed within 2 FHTs; the results might not reflect other FHTs or primary care sites. Also, prescribers volunteered to receive academic detailing and the results of this feasibility study might not reflect those participants who declined. Given that this was a feasibility study, another limitation includes the lack of data on actual quit rates of patients following the introduction of the PAD program.

Conclusion

The results of this study can be used to plan a larger PAD study on SC in an environment where policies would encourage such a program. As of August 2010, there were 200 FHTs in Ontario, in which 90 different FHTs had approximately 132 pharmacists integrated within the practices.46 A large, multisite, prospective randomized study of PAD on SC would be optimal to better understand how this approach can improve medication prescribing, its effectiveness on quit rates, and related patient health outcomes.

This study shows that PAD is feasible in a primary care setting. Further study is warranted to determine the effectiveness of PAD and whether PAD is more effective than conventional academic detailing.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

This study shows that patient-specific academic detailing (PAD) is feasible in a primary care setting. The high number of referrals to the pharmacists for smoking cessation (SC) after the provision of PAD shows that it might be a promising approach that moves beyond knowledge transmission to use existing clinical relationships and changes to processes within the practice setting to stimulate substantial behaviour changes.

The results of this study can be used to plan a larger PAD study on SC in an environment where policies would encourage such a program. A large, multisite, prospective randomized study of PAD on SC would be optimal to better understand how this approach can improve medication prescribing, its effectiveness on quit rates, and related patient health outcomes.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Cette étude démontre que la formation continue en pharmacothérapie spécifique au patient (FPSP) est faisable en milieu de soins primaires. Le nombre élevé de demandes de consultation auprès des pharmaciens pour cessation du tabagisme (CT) après la présentation du programme de FPSP démontre que ce pourrait être une approche prometteuse qui va au-delà de la transmission du savoir pour utiliser les relations cliniques existantes, changer les processus au sein des milieux de pratique et provoquer de considérables changements comportementaux.

On peut se servir de ces résultats pour planifier une étude de plus grande envergure sur la FPSP pour la CT dans un environnement où les politiques encourageraient un tel programme. Une grande étude randomisée multicentrique prospective serait optimale pour mieux comprendre comment cette approche peut améliorer la prescription de médicaments, ses effets positifs sur les taux de cessation et les résultats connexes en matière de santé des patients.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Dr Jin contributed to the concept and design of the study; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the article; and final approval of the version to be published. Dr Gagnon contributed to acquisition of data, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. Dr Levine contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of data, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. Dr Thabane contributed to analysis, reporting, and interpretation of the results; critical revision of the article for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. Ms Rodriguez contributed to the concept and design of the study, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. Dr Dolovich contributed to the concept and design of the study; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; critical revision of the article for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest

References

- 1.KT knowledge base. Glossary. Ottawa, ON: KT Clearinghouse; 2006. Knowledge Translation Program. Available from: http://ktclearinghouse.ca/knowledgebase/glossary. Accessed 2013 Dec 13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):II2–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coenen S, Van Royen P, Michiels B, Denekens J. Optimizing antibiotic prescribing for acute cough in general practice: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54(3):661–72. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh374. Epub 2004 Jul 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seager JM, Howell-Jones RS, Dunstan FD, Lewis MA, Richmond S, Thomas DW. A randomised controlled trial of clinical outreach education to rationalise antibiotic prescribing for acute dental pain in the primary care setting. Br Dent J. 2006;201(4):217–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon DH, Van Houten L, Glynn RJ, Baden L, Curtis K, Schrager H, et al. Academic detailing to improve use of broad-spectrum antibiotics at an academic medical center. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1897–902. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilett KF, Johnson S, Greenhill G, Mullen L, Brockis J, Golledge CL, et al. Modification of general practitioner prescribing of antibiotics by use of a therapeutics adviser (academic detailer) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(2):168–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Eijk ME, Avorn J, Porsius AJ, de Boer A. Reducing prescribing of highly anticholinergic antidepressants for elderly people: randomized trial of group versus individual academic detailing. BMJ. 2001;322(7287):654–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7287.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berings D, Blondeel L, Habraken H. The effect of industry-independent drug information on the prescribing of benzodiazepines in general practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46(6):501–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00196105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Burgh S, Mant A, Mattick RP, Donnelly N, Hall W, Bridges-Webb C. A controlled trial of educational visiting to improve benzodiazepine prescribing in general practice. Aust J Public Health. 1995;19(2):142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1995.tb00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt I, Claesson CB, Westerholm B, Nilsson LG, Svarstad BL. The impact of regular multidisciplinary team interventions on psychotropic prescribing in Swedish nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(1):77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Midlöv P, Bondesson A, Eriksson T, Nerbrand C, Höglund P. Effects of educational outreach visits on prescribing of benzodiazepines and antipsychotic drugs to elderly patients in primary health care in southern Sweden. Fam Pract. 2006;23(1):60–4. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi105. Epub 2005 Dec 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newton-Syms FA, Dawson PH, Cooke J, Feely M, Booth TG, Jerwood D. The influence of an academic representative on prescribing by general practitioners. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;33(1):69–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb04002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pit SW, Byles JE, Henry DA, Holt L, Hansen V, Bowman DA. A Quality Use of Medicines program for general practitioners and older people: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2007;187(1):23–30. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stafford RS, Bartholomew LK, Cushman WC, Cutler JA, Davis BR, Dawson G, et al. Impact of the ALLHAT/JNC7 Dissemination Project on thiazide-type diuretic use. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(10):851–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young JM, D’Este C, Ward JE. Improving family physicians’ use of evidence-based smoking cessation strategies: a cluster randomization trial. Prev Med. 2002;35(6):572–83. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schauer GL, Thompson JR, Zbikowski SM. Results from an outreach program for health systems change in tobacco cessation. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(5):657–65. doi: 10.1177/1524839911432931. Epub 2012 Apr 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheffer MA, Baker TB, Fraser DL, Adsit RT, McAfee TA, Fiore MC. Fax referrals, academic detailing, and tobacco quitline use: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adsit R, Fraser D, Redmond L, Smith S, Fiore M. Changing clinical practice, helping people quit: the Wisconsin Cessation Outreach Model. WMJ. 2005;104(4):32–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swartz SH, Cowan TM, DePue J, Goldstein MG. Academic profiling of tobacco-related performance measure in primary care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(Suppl 1):S38–44. doi: 10.1080/14622200210128018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein MG, Niaura R, Willey C, Kazura A, Rakowski W, DePue J, et al. An academic detailing intervention to disseminate physician-delivered smoking cessation counseling: smoking cessation outcomes of the Physicians Counseling Smokers Project. Prev Med. 2003;36(2):185–96. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daly MB, Balshem M, Sands C, James J, Workman S, Engstrom PF. Academic detailing: a model for in-office CME. J Cancer Educ. 1993;8(4):273–80. doi: 10.1080/08858199309528243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen M, Ferrier S, O’Connor N, Fleming I. Family physicians’ perception of academic detailing: a quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssens I, De Meyere M, Habraken H, Soenen K, van Driel M, Christiaens T, et al. Barriers to academic detailers: a qualitative study in general practice. Eur J Gen Pract. 2005;11(2):59–63. doi: 10.3109/13814780509178239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nkansah N, Mostovetsky O, Yu C, Chheng T, Beney J, Bond CM, et al. Effect of outpatient pharmacists’ non-dispensing roles on patient outcomes and prescribing patterns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD000336. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000336.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005182. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005182.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J, Farrell B, Austin Z, Rodriguez C, et al. Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primary care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(6):913–7. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.29. Epub 2008 Mar 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4):CD000409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avorn J, Soumerai SB. Improving drug-therapy decisions through educational outreach. A randomized controlled trial of academically based “detailing.”. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(24):1457–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.May FW, Rowett DS, Gilbert AL, McNeece JI, Hurley E. Outcomes of an educational-outreach service for community medical practitioners: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Med J Aust. 1999;170(10):471–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freemantle N, Nazareth I, Eccles M, Wood J, Haines A, Evidence-based Outreach Trialists A randomised controlled trial of the effect of educational outreach on prescribing in UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(477):290–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centor RM, Cohen SJ. Pharyngitis management: focusing on where we agree. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(13):1345–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney MJ, Jr, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH, Infectious Diseases Society of America Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(2):113–25. doi: 10.1086/340949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, Vanjaka A, Low DE. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1587–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh S, Dolan JG, Centor RM. Optimal management of adults with pharyngitis—a multi-criteria decision analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2006;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzales R, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, Cooper RJ, Hickner JM, Hoffman JR, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for treatment of acute respiratory tract infections in adults: background, specific aims, and methods. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):479–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linder JA, Chan JC, Bates DW. Evaluation and treatment of pharyngitis in primary care practice. The difference between guidelines is largely academic. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(13):1374–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smoking cessation guidelines. How to treat your patient’s tobacco addiction. Moorebank, Aust: Pegasus Healthcare International; 2000. Optimal Therapy Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong W, Papoushek C. Smoking cessation. Health Knowledge Central; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stack NM. Smoking cessation: an overview of treatment options with a focus on varenicline. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(11):1550–7. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.11.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crane R. The most addictive drug, the most deadly substance: smoking cessation tactics for the busy clinician. Prim Care. 2007;34(1):117–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Regier L, Jensen B, Chan W. Tobacco/smoking cessation pharmacotherapy. 7th ed. Saskatoon, SK: RxFiles; 2008. pp. 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, Cheng J, Ismaila A, Rios LP, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin M, Naumann T, Regier L, Bugden S, Allen M, Salach L, et al. A brief overview of academic detailing in Canada: another role for pharmacists. Can Pharm J. 2012;145(3):142–6.e2. doi: 10.3821/145.3.cpj142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care . Family health teams. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2012. Available from: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/fht/. Accessed 2012 Oct 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]