Abstract

Objective

To identify and prioritize innovative strategies to address the health concerns of vulnerable migrant populations.

Design

Modified Delphi consensus process.

Setting

Canada.

Participants

Forty-one primary care practitioners, including family physicians and nurse practitioners, who provided care for migrant populations.

Methods

We used a modified Delphi consensus process to identify and prioritize innovative strategies that could potentially improve the delivery of primary health care for vulnerable migrants. Forty-one primary care practitioners from various centres across Canada who cared for migrant populations proposed strategies and participated in the consensus process.

Main findings

The response rate was 93% for the first round. The 3 most highly ranked practice strategies to address delivery challenges for migrants were language interpretation, comprehensive interdisciplinary care, and evidence-based guidelines. Training and mentorship for practitioners, intersectoral collaboration, and immigrant community engagement ranked fourth, fifth, and sixth, respectively, as strategies to address delivery challenges. These strategies aligned with strategies coming out of the United States, Europe, and Australia, with the exception of the proposed evidence-based guidelines.

Conclusion

Primary health care practices across Canada now need to evolve to address the challenges inherent in caring for vulnerable migrants. The selected strategies provide guidance for practices and health systems interested in improving health care delivery for migrant populations.

Résumé

Objectif

Cerner des stratégies novatrices pour aborder les préoccupations de santé des populations de migrants vulnérables et en établir la priorité.

Type d’étude

Processus consensuel selon une méthode Delphi modifiée.

Contexte

Canada.

Participants

Un groupe de 41 professionnels des soins primaires, y compris des médecins de famille et des infirmières praticiennes qui dispensaient des soins à des populations de migrants.

Méthodes

Nous avons utilisé un processus consensuel selon une méthode Delphi modifiée pour identifier des stratégies novatrices susceptibles d’améliorer la prestation des soins de santé primaires à des migrants vulnérables et en établir la priorité. Un groupe de 41 professionnels des soins primaires de divers centres au Canada ont proposé des stratégies et ont participé au processus consensuel.

Principales observations

Le taux de réponse était de 93 % pour la première ronde. Les trois stratégies de pratique qui ont reçu les plus hautes cotes pour répondre aux problèmes des migrants étaient l’interprétation des langues, des soins interdisciplinaires complets et des lignes directrices fondées sur des données probantes. La formation et le mentorat pour les professionnels, la collaboration intersectorielle et la mobilisation de la communauté des migrants sont arrivés respectivement aux quatrième, cinquième et sixième rangs à titre de stratégies pour répondre aux problèmes dans la prestation. Ces stratégies concordaient avec celles proposées aux États-Unis, en Europe et en Australie, à l’exception de la proposition de lignes directrices fondées sur des données probantes.

Conclusion

Les pratiques de soins de santé primaires au Canada doivent maintenant évoluer dans le but d’éliminer les difficultés inhérentes à la prestation de soins aux migrants vulnérables. Les stratégies choisies offrent des conseils aux pratiques et aux systèmes de santé intéressés à améliorer la prestation des soins de santé aux populations de migrants.

More than 500 000 international migrants arrive in Canada each year.1 In recent decades, migrant source countries have shifted dramatically from Anglo-Saxon European countries to Asian, African, and Latin American countries.2 While migration is most noticeable in large urban centres, immigrants are also settling in rural and suburban regions.3 Vulnerable migrants including refugees and those with language, cultural, and financial barriers often face persistent challenges with comprehensive and continuous primary health care.4,5 Neighbourhood primary health care services are often poorly adapted to meeting migrant needs, resulting in further marginalization of these already-vulnerable groups.6 Recent Canadian government cuts to refugee health coverage have further increased the pool of vulnerable migrants in Canada.7

A recommendation from the Canadian Immigrant Health Guidelines8 identified the need to improve the delivery of primary health care services for vulnerable migrants. Barriers to primary health care include gaps in migrants’ knowledge about local services5; gaps in conceptualization of problems, beliefs, and practices between migrants and practitioners9; the inability to use services owing to language barriers; and not wanting to use existing services because of fear, distrust, negative experiences, or transportation barriers.10,11 Innovative practice strategies and system interventions can potentially address or at least help mitigate some of the barriers migrants face in relation to obtaining comprehensive primary health care.12,13 Recent research in Canada,14,15 Europe,16,17 Australia,18,19 and the United States20–22 has identified promising strategies for health systems relevant for migrant populations. The aim of this project was to identify and prioritize strategies that potentially could strengthen Canadian primary health care and meet the needs of vulnerable migrant populations.23

METHODS

We used a modified Delphi technique24,25 to generate, prioritize, and achieve consensus on the most critical practice strategies needed to improve primary health care for vulnerable migrant populations. Before starting the consensus process, we conducted a scoping literature review and consulted key informants from the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH) to identify promising practice strategies. The CCIRH is a national collaboration of more than 150 primary care practitioners, immigrant community champions, researchers, and program and policy planners dedicated to improving the health of immigrants and refugees (www.ccirhken.ca). This initial literature review and consultation process identified 13 practice strategies relevant for primary health care.

We developed priority-setting criteria aimed at addressing inequities in primary health care delivery using a multi-criteria decision-analysis approach.26 The criteria sought to identify effective interventions in primary care settings and organizations, evidence-based practices that considered sociocultural factors, and equitable access and use of primary care services, as well as practices that might influence future comprehensive health system policies.

We purposively selected 41 primary care practitioners, including family physicians and nurse practitioners working with migrants in various centres across Canada, aiming to select practitioners with in-depth experience with various migrant populations. Participants were primarily recruited from the CCIRH Health Knowledge Exchange Network. In the first round of the Delphi ranking, we asked participants to rank the identified practice strategies from 1 (highest priority) to 13 (lowest priority). To ensure our list of strategies was comprehensive, we invited participants to propose additional practice strategies. We chose a priori a rank average of 5 or less to acclaim the top 3 strategies. In the second round, we included an additional 5 items that were frequently suggested by practitioners as potentially effective strategies together with previously ranked items in order to select 3 more strategies. After the second round, we reviewed our ranked priority strategies from round 2 with 3 international migration health experts in an effort to confirm the consistency of our results with findings from other regions. We also used these consultations to help craft our definitions and to remain aware of variations in nomenclature in relation to innovative strategies. For the third round, which prioritized the most highly ranked strategies thus far, we included detailed definitions for each item and had participants rank the list of items, including the top 3 strategies that had already reached consensus.

We used an average score for each item to rank the strategies in each round of the consensus survey. A cutoff score of 3 was used for acclamation. Each round consisted of e-mailing participants an explanation of the process to date, the priority-setting criteria, instructions for filling out the survey, and a link to the online survey (www.surveymonkey.com). We used Microsoft Excel for the analysis of the results. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ottawa Hospital Ethics Board and the University of British Columbia’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

FINDINGS

Participants represented 8 of the 10 Canadian provinces, but half of them came from Ontario. Most described their clinical settings as urban or inner city (Table 1). In this group, most respondents were women and more than two-thirds had more than a decade of clinical experience. All had academic expertise or local leadership roles and all of them demonstrated ongoing clinical commitment to migrant populations.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the Delphi panel: N = 41.

| VARIABLE | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group, y | |

| • 25–39 | 8 (19.5) |

| • 40–49 | 16 (39.0) |

| • 50–59 | 13 (31.7) |

| • Unknown* | 4 (9.8) |

| Sex | |

| • Male | 13 (31.7) |

| • Female | 23 (56.1) |

| • Unknown* | 5 (12.2) |

| Province or territory | |

| • Alberta | 2 (4.9) |

| • British Columbia | 7 (17.1) |

| • Manitoba | 4 (9.8) |

| • Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 (2.4) |

| • Nova Scotia | 1 (2.4) |

| • Ontario | 20 (48.8) |

| • Quebec | 2 (4.9) |

| • Unknown* | 4 (9.8) |

| Area of work | |

| • Inner city | 15 (36.6) |

| • Urban area | 18 (43.9) |

| • Suburban area | 3 (7.3) |

| • Unknown* | 5 (12.2) |

| Type of practice or service† | |

| • Community health centre | 16 (39.0) |

| • Family practice team | 12 (29.3) |

| • Other group practice | 7 (17.1) |

| • Private solo practice and other | 7 (17.1) |

| • Unknown* | 5 (12.2) |

| Professional role | |

| • Family physician | 30 (73.2) |

| • Nurse practitioner or clinical nurse | 7 (17.1) |

| • Unknown* | 4 (9.8) |

| Time practising as health professional, y | |

| • < 1 | 0 (0.0) |

| • 1–3 | 4 (9.8) |

| • 4–5 | 1 (2.4) |

| • 6–10 | 7 (17.1) |

| • > 10 | 25 (61.0) |

| • Unknown* | 4 (9.8) |

| Length of time providing care to immigrants and refugees, y | |

| • 1–3 | 7 (17.1) |

| • 4–5 | 3 (7.3) |

| • 6–10 | 12 (29.3) |

| • > 10 | 15 (36.6) |

| • Unknown* | 4 (9.8) |

| Method of payment | |

| • Fee for service | 5 (12.2) |

| • Other (eg, salaried, capitation) | 14 (34.1) |

| • Unknown* | 22 (53.7) |

Demographic information was not available for all participants.

Panel participants could practise in more than 1 setting.

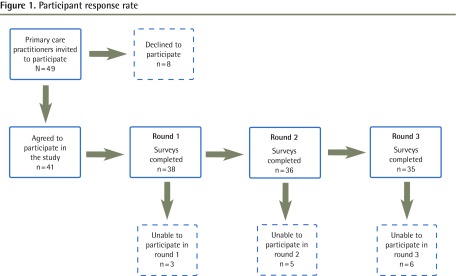

During the first round (Table 2), participants were asked to rank the practice strategies they thought would lead to the greatest improvements in the health care of immigrants and refugees and to add any additional strategies that had not been listed (Box 1n). The response rate for the first round was 93% (Figure 1). The following were the 3 most highly ranked items:

language interpretation or communication supports;

comprehensive health care (interdisciplinary, collaborative, or team-based health care delivery and continuity of care); and

evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice.

Table 2.

First-round ranking results of the initial list of innovative practices that was developed based on literature review: Options were rated from 1 (highest priority) to 13 (lowest priority).

| ANSWER OPTIONS | RESPONSE AVERAGE |

|---|---|

| Language interpretative services, just-in-time services to enhance patient–health care provider communication | 1.47 |

| Comprehensive health care: interdisciplinary care, collaborative or team-based health care delivery, and continuity of care | 4.69 |

| Evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice | 4.80 |

| Intersectoral collaboration: promote and support more collaborative approach between government institutions (eg, CIC), immigrant organizations, and settlement and health services (regular meetings, seminars, workshops, etc) to strengthen coordination and interaction | 6.49 |

| Lower-cost health care services: access to care, generic and essential drugs | 7.23 |

| Clinical information systems for decision support, continuity of care, and appropriate follow-up | 7.52 |

| Improve health literacy: implement participatory educational programs (using qualitative methodologies, collective engagement, and participatory strategies) | 7.63 |

| Culturally sensitive health services: trained clinicians and organizations to develop effective leadership skills, improve cultural competency, and enhance system responsiveness | 7.68 |

| Implement collaborative, community-oriented mental health services with participatory components that involve family members in treatment options or involve community organizations and community resources (eg, housing places, social support grounds, ESL programs and courses) | 8.06 |

| Patient education: provide self-management support to patients and families to learn and acquire skills to manage their conditions | 8.17 |

| Simplification of treatment approaches for high-priority diseases (eg, diabetes, disabilities) | 8.73 |

| Networking and collaboration: engagement of civil society and community actors such as health brokers (eg, Multicultural Health Broker Cooperative), health workers, and other social networks | 9.38 |

| Outreach services or mobile services: organize services to reach marginalized groups with promotion, prevention, and health services | 9.53 |

CIC—Citizenship and Immigration Canada, ESL—English as a second language.

Box 1. First-round suggestions from participants for other strategies.

Participants suggested the following additional strategies in the first round:

Comprehensive best-practice checklists and algorithms to facilitate initial contact with unfamiliar primary care

Regular learning and knowledge transfer

Group models (peer support or educator models, group medical appointments)

Make sure learners (nursing, medicine, social work, etc) have educational experiences related to this field in their clinical experiences, then they are more likely to be involved when in practice

Satellite office in the greater Toronto area with expertise and mentoring from local experts

Peer support or mentors

Clearly established migrant health care–specific systems-navigation programs and services for providers and consumers

Mutual support groups for survivors of torture

Links with leaders of migrant communities are essential

Group visits for topics requiring lots of education (eg, diabetes, cardiac health, women’s health)

Rapid-access telephone consultation service for GP to a provincial or national immigrant and refugee specialist

More support from telehealth and telemedicine

Referral facilitators for second step “prise en charge” by clinicians in sector

Continually updated “menu” of services in communities, regions, provinces, and nationally (Web based and easily accessible)

Primary care psychotherapy

Culturally sensitive brochures or information provided by provincial agencies such as public health

Free language services in fee-for-service physicians’ offices

Better integration of various evidence-based guidelines

Consultation services for cases with important cultural or language barriers

Timely access for care providers to a clinical “help desk” with expert support

Develop peer support within migrant communities

System for medical office assistants to effectively communicate with patients whose first language is not English over the telephone for booking, results, etc

Immigrant health education integrated in medical and nursing school curriculum

Engage migrant communities to have facilitators to help migrants navigate the system

Figure 1.

Participant response rate

For the second round (Tables 3 and 4),22,27 we prepared a list including the items rated fourth and fifth in the first round and the additional strategies suggested (Box 1). The response rate for the second round was 88%. The second round identified 3 key priority strategies:

training and mentorship for health care providers;

intersectoral collaboration; and

community engagement and support.

Table 3.

Top ranked items from second-round ranking, including additional list of innovative practices: Options were rated from 1 (highest priority) to 15 (lowest priority).

| ANSWER OPTIONS | RESPONSE AVERAGE |

|---|---|

| Training and mentorship for health care providers | 2.11 |

| Intersectoral collaboration | 2.19 |

| Community engagement and support | 2.83 |

| Lower-cost health care services | 3.89 |

| Telemedicine support (eg, eHealth) | 3.92 |

Table 4.

Definition and description of practice strategy

| PRACTICE STRATEGY | DEFINITION AND DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Language interpretative services, just-in-time communication | Services provided to address language barriers in accessing health care services by implementing mechanisms to facilitate or enhance communication between clients and health care providers. The most common approach to respond to this need is the use of interpreter services. In order to ensure just-in-time interpretation, those services should be provided promptly, essentially right through oral interpretation, by using bilingual providers and staff, hiring staff interpreters, contracting with qualified interpreters, and creating interpreter pools22 |

| Comprehensive health care | Comprises an integral approach to providing health care considering

several key aspects:

|

| Evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice | Introduction in clinical practice of a compilation of standardized recommendations for clinicians aimed at providing effective care to patients with specific conditions. These recommendations are based on the best available scientific and academic evidence and practical experience |

| Training and mentorship for health care providers | This refers to a well-designed results-oriented strategy. As stated by the CFPC, “While graduation from an accredited Canadian family medicine residency program provides the knowledge and skills necessary to enter the profession, this is by no means the final step of the educational process for family physicians in Canada.”27 As health professionals, family physicians and other primary care practitioners need to remain up to date on advances and trends in medicine and health care delivery. This is achieved through participation in various academic activities that constitute continuing professional development. The CFPC encourages and supports family physicians in meeting their CPD goals through various programs and services, including Mainpro credit reporting, Self Learning, Linking Learning to Practice, Pearls, and other educational strategies27 |

| Intersectoral collaboration | A strategy consisting of coordinated actions between the health sector and health services, as well as other stakeholders and sectors of society (education, industry, sanitation, environment, etc), working together to achieve specific health goals for the population |

| Community engagement and support | Community participation is an educational and empowering process in which the people, in partnership with those who are able to assist them, identify the problems and the needs and increasingly assume responsibilities themselves to plan, manage, control, and assess the collective actions that are proved necessary to address these problems and needs. This strategy should be built on a genuine community– health sector partnership looking to develop effective health services for the communities |

CFPC—College of Family Physicians of Canada, CPD—continuing professional development.

A third round was then conducted (Table 5); the response rate was 85%. The final ranking of the most critical strategies was as follows:

language interpretive services and communication support;

comprehensive interdisciplinary health care;

evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice;

training and mentorship for health care providers;

intersectoral collaboration; and

community engagement and support.

Table 5.

Third-round, final ranking: Options were rated from 1 (highest priority) to 6 (lowest priority).

| ANSWER OPTIONS | RESPONSE AVERAGE |

|---|---|

| Language interpretative services, just-in-time communication | 1.43 |

| Comprehensive health care | 3.35 |

| Evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice | 3.57 |

| Training and mentorship for health care providers | 3.59 |

| Intersectoral collaboration | 3.95 |

| Community engagement and support | 5.11 |

DISCUSSION

This Delphi consensus identified language interpretive services, comprehensive interdisciplinary care, and evidence-based guidelines as the priority practice strategies needed to improve delivery of primary health care to vulnerable migrants. Many of these selected strategies were consistent with recommended strategies from the United States and Australia, most notably language and communication support and hiring and promoting minorities in the health care work force. The one main difference in our recommended strategies, compared with those of other countries, was the explicit inclusion of evidence-based guidelines. Europe recommended improved quality of care fourth on their list, and one might consider evidence-based guidelines to be under the umbrella of improved quality of care (Table 6).16,18,20

Table 6.

Comparison of supportive health care strategies for migrants

| CANADIAN DELPHI STUDY | EUROPE16* | AUSTRALIA18 | UNITED STATES20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language interpretative services | Access to health care | Migration system and entitlements | Hiring and promoting minorities in the health care work force |

| Comprehensive health care | Empowerment of immigrants | Addressing specific health problems of refugees | Involving representatives from the community in planning and quality improvement efforts |

| Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines | Culturally sensitive health services | Health professional training | Providing on-site interpreters in settings with large numbers of patients with limited proficiency in English |

| Training and mentorship for health care providers | General quality of health care | Free multilingual materials available | Ensuring that health information is at an appropriate literacy level and targeted to the language and culture of patients |

| Intersectoral collaboration | Patient–health care provider communication | Help with issues related to asylum seekers | Collecting racial, ethnic, and language preference data for patients in order to monitor disparities in care |

| Community engagement and support | Respect toward immigrants | Ethnic-specific services available | Integrating cross-cultural training into professional development and training activities for health care providers |

| Networking in and outside health services | Information available to assist with health service planning | Incorporating cultural and language-appropriate survey methods into quality improvement efforts |

The EUGATE project was funded by the General Directorate of Health and Consumer Protection of the European Union.16

In our work there was a clear consensus on the need for interpretive services for community-based primary health care. Language barriers can negatively affect access to primary health services and can lead to serious health consequences.26,28 In Europe, the top recommendation was improving access to care, the United States recommended hiring and promoting minorities in the health care work force, and Australia, which has a national telephone interpretation program, recommended migration entitlements (Table 6).16,18,20 Two basic approaches have been suggested to address barriers caused by the lack of a shared language between patient and practitioner. The first is to match patients with practitioners who share the same language. The second is to provide some form of interpretation.29 Different models of interpretation services include untrained (family) interpreters, professional interpreter services (community or hospital based), and third-party telephone interpreter services.30 The cost of interpretive services varies considerably from in-person interpretation to telephone interpretation.30 Some of the Canadian experts noted their hospitals had recently received funded access to interpretation services, and the decisive ranking suggested that it was a priority to scale up access to such services across Canada.

The National Health Law Program, with funding from The Commonwealth Fund,22 undertook an assessment of programs that aimed to improve access to interpreter services in primary health care settings. It examined several different methods of providing oral interpretation, including using bilingual providers and staff, hiring staff interpreters, contracting with qualified interpreters, and creating interpreter pools. The results suggest the need for a range of approaches (programs and training elements) tailored to the needs of specific communities and patient populations, and they show that such approaches have been successful.31

Our second highest ranked practice strategy was comprehensive interdisciplinary care with continuity of care. Europe put forward the idea of empowerment second, and the United States suggested involving representatives from the communities in planning and quality improvement efforts (Table 6).16,18,20 Comprehensive interdisciplinary care appears in many definitions of primary care and generalist care.32 It is clearly linked: a practitioner is more likely to provide continuous care if the care provided is comprehensive enough to encompass the many different conditions that a patient might develop in his or her lifetime, such as the expanded scope of practice evident in rural Canadian primary care. In Ontario, models of care such as fee-for-service care have been associated with less continuity and more emergency department use.33 Indeed, the degree of comprehensiveness in primary health care (ie, the extent to which a broader range of services is provided within primary health care rather than through referrals to specialists) is one of the defining features of countries with high-performing primary care systems.34

The third highest ranked strategy was clinical practice guidelines. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines aim to improve the quality and appropriateness of care, treatment outcomes, and the efficiency of care.35 Improving quality of care was also recommended in Europe (Table 6).16,18,20 Historically, evidence-based guidelines have not existed to support the primary health care of migrant populations. In 2011, a comprehensive set of evidence-based clinical guidelines was published in Canada.8 Currently these guidelines are available online (www.ccirhken.ca) along with decision-support and training strategies using e-learning tools and region-specific electronic checklists. High-quality guidelines for vulnerable populations, combined with practitioner mentorship and training, can potentially help practitioners refine their clinical approach and avoid the harms and opportunity costs that are associated with overdiagnosis.36

Other prioritized strategies included intersectoral collaboration, and community engagement and support. These 2 strategies have been widely recognized as essential to addressing the social determinants of health.37,38 Abundant research has pointed out the prominence of social determinants in immigrants’ health transitions, emphasizing the role of living conditions and individual behavioural factors that affect peoples’ lives, while minimizing the value of appropriate health care. These priorities reflect an important and integral perspective of the panel on the notion of how to act in improving the health of vulnerable immigrants.

Few primary care practices have implemented any of these strategies; consequently, the prioritized list represents a recommendation to improve the health system across Canada through implementation of these strategies into primary care practices.

Limitations

Using practitioners to select strategies ensured both that the needs of opinion leaders were heard and that the strategies they viewed as most needed were prioritized. But in working with perceived needs of practitioners, we risked a reporting bias: overemphasizing strategies that were needed for specific refugee populations, or strategies that were needed for specific regional health systems. To mitigate this bias we used a panel of international migrant health leaders. The inclusion of migrant health experts who might have been involved in or at least aware of the evidence-based guidelines for immigrants and refugees8 might have biased the results toward selecting guidelines as a practice strategy in Canada. Comparisons of recommended practice strategies across countries might be limited because of differences in local contexts, differences in the perspectives of the authors or respondents, or differences in the breadth, definition, and scope of the interventions described. The implementation of effective practice interventions and strategies continues to require greater conceptual clarity and consistency of language. We hope our work contributes to the international consensus building around strategies for migrant health and builds on the evidence-based efforts of groups such as the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization Care Group.

Conclusion

Canadian primary health care needs to evolve to address the challenges of vulnerable migrant populations. Our selected strategies provide guidance for practices and policy makers interested in improving care delivery for migrant populations. As migrants continue to originate from around the globe, and as migrants begin to move to smaller cities and towns, the primary health system must find ways to implement interpretation services, support comprehensive care and continuity of care, provide evidence-based guidelines, develop training for practitioners, and enable new ways to promote intersectoral care and community engagement.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Immigration continues to increase diversity in many Canadian regions. The most vulnerable migrants will encounter cultural and linguistic barriers that impede trust in, navigation of, and access to primary health care.

This study used a Delphi consensus process to determine what strategies to address the health needs of migrants were considered priorities by a group of primary care practitioners who provided care to this vulnerable population.

Participants indicated that in order to improve migrant health care, the primary health system must find ways to implement interpretation services, support comprehensive care and continuity of care, provide evidence-based guidelines, develop training for practitioners, and enable new ways to promote intersectoral care and community engagement.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

L’immigration continue d’accroître la diversité dans de nombreuses régions au Canada. Les migrants les plus vulnérables seront confrontés à des obstacles culturels et linguistiques qui les empêchent de faire confiance aux soins de santé primaires, de naviguer à l’intérieur de ce système de soins et d’y accéder.

Dans cette étude, on s’est servi d’un processus consensuel Delphi pour déterminer quelles étaient les stratégies visant à répondre aux besoins des migrants en matière de santé étaient jugées prioritaires par un groupe de professionnels des soins primaires prodiguant des soins à cette population vulnérable.

Les participants ont indiqué que pour améliorer les soins de santé aux migrants, le système des soins primaires doit trouver des façons d’offrir des services d’interprétation, de soutenir des soins complets, globaux et continus, de fournir des lignes directrices fondées sur des données probantes, d’élaborer de la formation à l’intention des professionnels et de mettre en œuvre de nouveaux moyens pour promouvoir les soins intersectoriels et la mobilisation de la communauté.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Health Canada Migration health: embracing a determinants of health approach. Health Can Res Bull. 2010;17:1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Hatcher Roberts J, Torres S, DesMeules M, Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E952–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagnon AJ. Responsiveness of the Canadian health care system towards newcomers. Ottawa, ON: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. Discussion paper no. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newbold B. Health status and health care of immigrants in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(2):77–83. doi: 10.1258/1355819053559074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Setia MS, Quesnel-Vallee A, Abrahamowicz M, Tousiqnant P, Lynch J. Access to health-care in Canadian immigrants: a longitudinal study of the National Population Health Survey. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19(1):70–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swinkels H, Pottie K, Tugwell P, Rashid M, Narasiah L, Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health Development of guidelines for recently arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada: Delphi consensus on selecting preventable and treatable conditions. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E928–32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arya N, McMurray J, Rashid M. Enter at your own risk: government changes to comprehensive care for newly arrived Canadian refugees. CMAJ. 2012;184(17):1875–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, Rashid M, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson K, Rosenberg MW. Accessibility and the Canadian health care system: squaring perceptions and realities. Health Policy. 2004;67(2):137–48. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(03)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rootman I, Ronson B. Literacy and health research in Canada: where have we been and where should we go? Can J Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 2):S62–77. doi: 10.1007/BF03403703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe RR. Working (in) the gap: a critical examination of the race/culture divide in human services. Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta; 2010. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10048/1256. Accessed 2013 Dec 11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caulford P, Vali Y. Providing health care to medically uninsured immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2006;174(9):1253–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasanathan K, Montesinos EV, Matheson D, Etienne C, Evans T. Primary health care and the social determinants of health: essential and complementary approaches for reducing inequities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(8):656–60. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.093914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson B, Cook CH. Innovative practices in immigrant and refugee health care in Canada; Paper presented at: 12th National Metropolis Conference; March 2010; Montreal, QC. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newbold B, Pottie K, Dam H, Ratnayake A. Welcoming Communities Initiative: evidence review for promising practices to address local immigrant partnership immigrant health priorities. Welcoming Communities Initiative e-Bulletin. 2011. Apr. Available from: www.welcomingcommunities.ca. Accessed 2013 Dec 11.

- 16.European best practices in access, quality and appropriateness of health services for immigrants in Europe. Project report on Delphi process on best practice of health care for immigrants. Utrecht, Neth: Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research; 2011. EUGATE Project. Work Package No. 7. Available from: http://lubis.lbg.ac.at/webfm_send/99. Accessed 2012 Jun 3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanciole AE, Huber M. Access to health care for migrants, ethnic minorities, and asylum seekers in Europe. Policy brief. Vienna, Aus: European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research; 2009. Available from: www.euro.centre.org/data/1254748286_82982.pdf. Accessed 2013 Dec 11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray SB, Skull SA. Hurdles to health: immigrant and refugee health care in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2005;29(1):25–9. doi: 10.1071/ah050025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Refugee Health Services Project . Best practice in refugee health care. Refugee health kit. Darebin, Aust: North Central Metropolitan Primary Care Partnership, Northern Division of General Practice; Available from: www.foundationhouse.org.au/LiteratureRetrieve.aspx?ID=25035. Accessed 2014 Jan 2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE. Cultural competence in health care: emerging frameworks and practical approaches. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2002. Available from: www.commonwealthfund.org/News/News-Releases/2002/Oct/Health-Care-Organizations-Break-New-Ground-In-The-Quest-To-Improve-Care-For-Immigrant-And-Minority-A.aspx. Accessed 2013 Dec 11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montoya ID. Health services considerations amongst immigrant populations. J Immigr Refug Serv. 2005;3(3–4):15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Youdelman M, Perkins J. Providing language interpretation services in health care settings: examples from the field. National Health Law Program. Field report. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pottie K, Srinivasan V, Tunis D, Kirmayer LJ, Mayhew M, Shakya Y, et al. Justin-Time/Juste-à-Temps communication and decision support for vulnerable migrant populations. Ottawa, ON: CIHR Team Grant Research proposal; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(6):1221–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeney S, Hassona F, McKenna HP. A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baltussen R, Louis Niessen L. Priority setting of health interventions: the need for multi-criteria decision analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2006;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.College of Family Physicians of Canada [website] Continuing professional development (CPD) Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2013. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/CPD. Accessed 2013 Dec 16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dean JA, Wilson K. “My health has improved because I always have everything I need here…”: a qualitative exploration of health improvement and decline among immigrants”. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(8):1219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowen S. Language barriers in access to health care. Report prepared for Health Canada. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobs EA, Shepard DS, Suaya JA, Stone EL. Overcoming language barriers in health care: costs and benefits of interpreter services. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):866–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahsiah S, Grégoire H. Health care interpreter services: strengthening access to primary health care. Literature review: examining language barriers and interpreter services in Canada’s health care sector. Report supported by the Primary Health Care Transition Fund. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan BT. The declining comprehensiveness of primary care. CMAJ. 2002;166(4):429–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howard M, Goertzen J, Kaczorowski J, Hutchison B, Morris K, Thabane L, et al. Emergency department and walk-in clinic use in models of primary care practice with different after-hours accessibility in Ontario. Healthc Policy. 2008;4(1):73–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starfield B, Shi L. Policy relevant determinants of health: an international perspective. Healthc Policy. 2002;60(3):201–18. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manchikanti L. Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management, part I: introduction and general considerations. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2):161–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welch HG, Schwartz L, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosed: making people sick in the pursuit of health. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adeleye OA, Ofili AN. Strengthening intersectoral collaboration for primary health care in developing countries: can the health sector play broader roles? J Environ Public Health. 2010:272896. doi: 10.1155/2010/272896. Epub 2010 April 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham ID. Citizen engagement in health casebook. Knowledge translation and public outreach. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2012. Available from: www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/ce_health_casebooks_eng.pdf. Accessed 2013 Dec 11. [Google Scholar]