Abstract

Background and objective

Physician awareness of the results of tests pending at discharge (TPADs) is poor. We developed an automated system that notifies responsible physicians of TPAD results via secure, network email. We sought to evaluate the impact of this system on self-reported awareness of TPAD results by responsible physicians, a necessary intermediary step to improve management of TPAD results.

Methods

We conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial at a major hospital affiliated with an integrated healthcare delivery network in Boston, Massachusetts. Adult patients with TPADs who were discharged from inpatient general medicine and cardiology services were assigned to the intervention or usual care arm if their inpatient attending physician and primary care physician (PCP) were both randomized to the same study arm. Patients of physicians randomized to discordant study arms were excluded. We surveyed these physicians 72 h after all TPAD results were finalized. The primary outcome was awareness of TPAD results by attending physicians. Secondary outcomes included awareness of TPAD results by PCPs, awareness of actionable TPAD results, and provider satisfaction.

Results

We analyzed data on 441 patients. We sent 441 surveys to attending physicians and 353 surveys to PCPs and received 275 and 152 responses from 83 different attending physicians and 112 different PCPs, respectively (attending physician survey response rate of 63%). Intervention attending physicians and PCPs were significantly more aware of TPAD results (76% vs 38%, adjusted/clustered OR 6.30 (95% CI 3.02 to 13.16), p<0.001; 57% vs 33%, adjusted/clustered OR 3.08 (95% CI 1.43 to 6.66), p=0.004, respectively). Intervention attending physicians tended to be more aware of actionable TPAD results (59% vs 29%, adjusted/clustered OR 4.25 (0.65, 27.85), p=0.13). One hundred and eighteen (85%) and 43 (63%) intervention attending physician and PCP survey respondents, respectively, were satisfied with this intervention.

Conclusions

Automated email notification represents a promising strategy for managing TPAD results, potentially mitigating an unresolved patient safety concern.

Clinical Trial Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01153451)

Keywords: Tests pending at discharge, care transitions, automated email notification

Background

The transition period after hospitalization is a vulnerable time for patients. More than half of preventable adverse events during this period are related to poor communication.1 2 For instance, physician awareness of the results of tests pending at discharge (TPADs) is poor. We previously determined that 41% of patients left the hospital before all test results were reported, and 9.4% of these results were considered potentially actionable.3 Although the physicians caring for these patients had access to a shared clinical data repository via an integrated, electronic medical record (EMR), they were aware of only 38% of TPAD results. Failure to follow-up TPAD results can lead to delays in diagnosis, missed treatment opportunities, redundant ordering of tests, malpractice litigation, and patient harm.4 5

Good communication between responsible inpatient and ambulatory physicians regarding TPAD results is critical to patient safety, but does not always occur.1 2 6 7 Most hospitals do not have a reliable system for managing TPADs. Currently, physicians rely on documentation in the discharge summary, direct communication, or other individual approaches. Discharge documentation often contains inaccurate or incomplete information on TPADs, variably conveys the rationale explaining why the test was ordered and what to do about the result, and often does not get to the primary care physician (PCP) in a timely manner.7 Thus, these systems are faulty for a variety of reasons, but primarily because they do not reliably provide timely information to the responsible provider who must then act.

Few institutions have successfully implemented and rigorously evaluated health information technology (HIT) strategies for managing TPADs. On the basis of a previous unsuccessful attempt at implementing a results manager application in the inpatient setting, we developed an automated system that notifies the responsible physicians of TPAD results via secure, network email.8 9 Our system assigns responsibility for TPAD results to the inpatient attending physician, is configured to minimize alert fatigue, and facilitates timely communication with the PCP. To achieve this, the system coordinates a series of electronic events triggered by the patient's discharge time stamp, suppresses certain TPADs based on configurable rules, updates the status of the TPADs on a daily basis, and automatically sends an email notifying the patient's attending physician and PCP of TPAD results on the day these results are finalized.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of our automated email notification system on physician awareness of TPAD results and assess overall satisfaction with this strategy. We chose awareness as our main outcome measure, as it is most sensitive to change and a necessary intermediary step in improving test result follow-up rates.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial at the Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), a 750-bed tertiary care hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, affiliated with Partners HealthCare, Inc, an integrated healthcare delivery network, from October 2010 through May 2011. Patients discharged from the general medicine and cardiology services were eligible if they had one or more TPADs. Patients were assigned to the intervention or usual care arm according to the randomization status of their responsible physicians (see below).

Participants and enrollment

The Partners Human Research Committee (PHRC) approved the study. We requested and were granted a waiver of patient consent. The PHRC requested an opt-out mechanism for physicians who explicitly declined to participate. Before initiation, we announced the study to all BWH clinical staff and Partners PCPs admitting patients to BWH. We enrolled any eligible patient (defined above) if their attending physician and PCP were willing to participate. Patients assigned to the intervention and usual care arms were excluded if either of these physicians explicitly opted out before or during the study period as required by the PHRC.

Our study population consisted of all eligible adult general medicine and cardiology patients who had at least one TPAD and whose physicians agreed to participate. Physicians caring for these patients included hospitalists, traditional internists, cardiologists, and other subspecialists who attended on general medicine services, network PCPs (ie, Partners affiliated), and non-network PCPs. All Partners physicians shared a common clinical data and notes repository accessible via the Partners EMR, and were able to access network email from any workstation, personal computer, or encrypted mobile device connected to a secure Microsoft Exchange Server. Non-network physicians did not have access to Partners clinical information systems, but discharge summaries were routinely faxed or mailed to them within 48 h of discharge.

Intervention

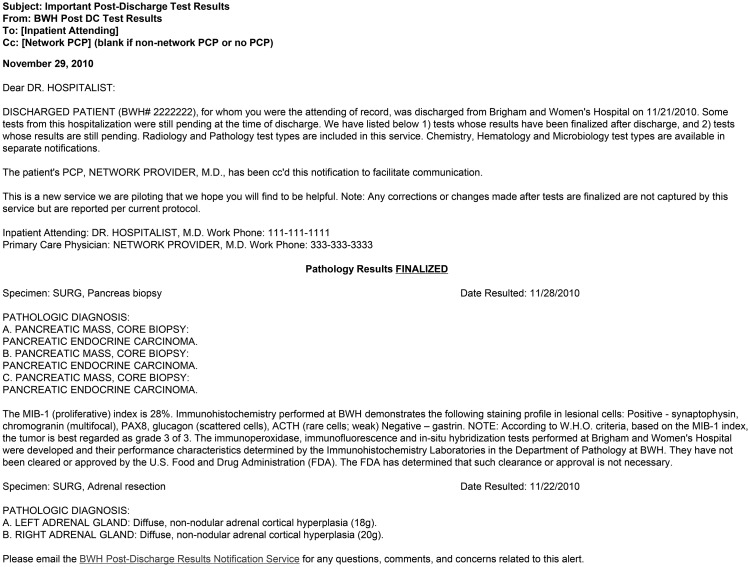

We previously reported the design of the automated email notification system, and validated its performance with regard to accurate identification of patients with TPADs, as well as the attending physician and PCP.9 Briefly, once a patient's TPAD results were finalized, the system automatically emailed the attending physician and sent a carbon copy of that email to the network PCP. There were separate notification emails for chemistry/hematology, radiology/pathology, and microbiology test result types. The system was configured to minimize alert fatigue: physicians received no more than one email per notification type per patient in a 24 h period, and certain tests with short turnaround times routinely checked by inpatient providers were excluded (eg, arterial blood gas). Based on this configuration, an attending physician would typically receive 1.6 notifications per patient with TPADs, and 60% of these notifications would be for microbiology results. If the patient had a non-network PCP (∼40% of BWH patients), or if no PCP was listed in administrative databases (see below), the attending physician alone received the email. We did not provide training. A typical email is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of an automated email notification received by intervention physicians. A typical radiology/pathology email generated by the system. There were three notification types: one for chemistry/hematology, radiology/pathology, and microbiology results. In this example, there were no pending radiology results at discharge; therefore, only pathology results were detected and reported by the system. This patient may have had other types of tests pending at discharge (TPADs) (eg, microbiology or chemistry/hematology), which would have triggered separate emails to the responsible physicians. All emails included standard information (eg, subject heading, patient name, medical record number, discharge date, contact information for the inpatient attending physician and primary care physician (PCP)), and results of TPADs. Non-network PCPs did not receive emails, but their contact information was included in emails sent to inpatient attending physician physicians. Therefore, the discharging attending physician could contact non-network PCPs after reviewing TPAD results.

Each physician was assigned a unique internal identification (ID) number within our administrative database. Our admissions staff routinely updated this database to ensure accuracy of the attending physician. Because the identity and contact information of the patient's PCP was updated during admission, we were able to include the name and telephone number of both network and non-network PCPs in emails to the attending physician if the PCP's name was entered correctly (ie, could be matched to the internal ID).

Randomization and patient enrollment

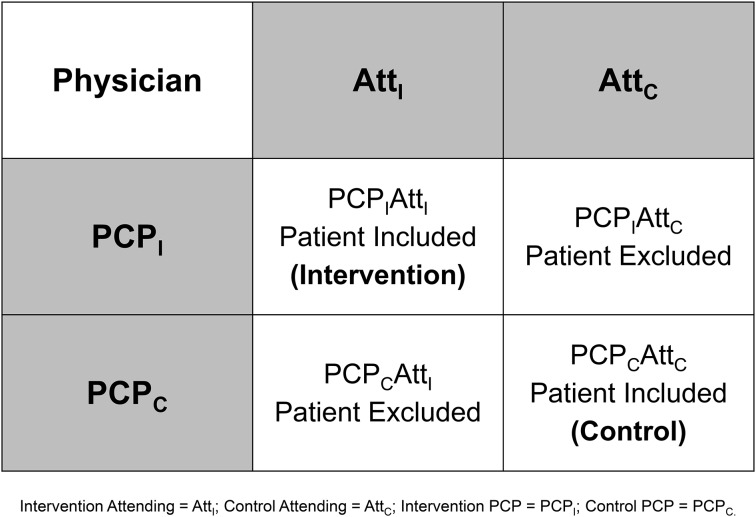

The attending physician and PCP were independently randomized once during the study period. Patients were assigned to intervention or usual care if both the attending physician and PCP were in the same study arm. Although physicians may have cared for one or more patients at different times during the study period, their randomization status did not change. We chose this approach to minimize the effects of contamination from the intervention on our study results. Specifically, if we randomized patients by the attending physician (or PCP) alone, then the PCP (or attending physician) could care for patients in both study arms. By excluding patients with discordantly randomized physician pairs, we were able to evaluate attending physician awareness while allowing for an unbiased analysis of PCP awareness. See figure 2 for an illustration and description of this randomization scheme.

Figure 2.

Randomization scheme. If we randomized by attending physician alone, then a primary care physician (PCP) of a patient in the usual care arm may also care for a patient in the intervention arm (ie, cared for by a different inpatient attending physician). Upon receiving notification of a test pending at discharge (TPAD) result of the intervention patient, the PCP could look up TPAD results of the usual care patient. Conversely, if we randomized by PCP alone, then an attending physician of a usual care patient may also care for a patient in the intervention arm (ie, cared for by a different PCP). Upon receiving notification of a TPAD result of the intervention patient, the attending physician could look up TPAD results of the usual care patient. Although the proposed schema reduced our sample size by 50%, it provided adequate statistical power to evaluate inpatient provider awareness while allowing for an unbiased analysis of PCP awareness.

Although all attending physicians were randomized before study initiation, it was not possible to determine the identities of all PCPs (mostly non-network PCPs) caring for patients during the study period a priori. Therefore, we manually assigned unrandomized network and all non-network PCPs to intervention or usual care arms at discharge on the basis of their internal ID (pseudo-randomization based on the last digit of this number). We automated this process midway during the study to enhance enrollment.

We excluded patients whose PCP was also assigned as attending physician (a small number of BWH PCPs attended on their own patients). This was to minimize bias from physicians who care for the same patient in the hospital and ambulatory setting. Because many discharged patients have only microbiology TPADs (ie, pending culture data), we partially sampled these patients. Specifically, in each arm every other patient discharged with microbiology TPADs was excluded. We justified this partial sampling on the basis of the potential for attending physicians (who typically see a high volume of patients over a 2-week service block) to receive a large volume of surveys by email within a short period of time. This could lead to survey fatigue, reduction in our response rate, and further bias.

Post hoc, we excluded patients if their physicians were involved in the study design or opted out, if their test results were cancelled, if the system was not functioning properly, or if surveys were generated incorrectly (ie, sent to the wrong physician).

All patients with TPADs identified by the system were tracked until their TPAD results were finalized. Research staff monitored the identity, study arm assignment, and whether emails were appropriately sent or suppressed (ie, carbon copies of emails were sent to an account accessible only by research staff). Research staff were also able to monitor any subsequent email correspondence between the attending physician and network PCP (ie, if either responded by clicking ‘reply all’ to the automated email).

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was self-reported awareness of TPAD results by attending physician. Secondary outcomes included self-reported awareness of TPAD results by PCP (network and non-network), self-reported awareness of actionable TPAD results by attending physician and PCP, and provider satisfaction.

We surveyed the attending physician and PCP ∼72 h after all TPAD results were finalized for each enrolled patient (eg, for a patient with three TPADs, a survey was sent after all three TPAD results were finalized). The attending physician and PCP were sent an email containing all finalized TPAD results and a hyperlink to a web-based survey. Non-network PCPs were faxed a paper copy of the TPAD results and survey. The survey asked about the physician's awareness of any finalized TPAD result contained in the email or fax (dichotomous variable), whether review of any TPAD result prompted or would prompt action (dichotomous variable), and satisfaction (rated on a 5-point Likert scale) with either their current method of managing TPADs (usual care) or with our system (intervention). Physicians were asked to specify which actions were or would be taken for TPAD results that they determined to be actionable. Survey instruments are included in the online supplementary appendix.

To improve response rates, physicians were given a US$20 Amazon.com gift card for all surveys completed within a calendar month (ie, an individual physician could receive no more than one gift card per month). We sent up to two reminders ∼3–5 days apart if the initial survey was not completed. The second reminder survey was faxed to both Partners and non-Partners physicians to reduce response bias (ie, physicians more likely to read a TPAD notification email would be likely to respond to an emailed survey). Individual survey responses were tracked by requiring participants to enter a randomly generated identifier supplied in the survey request email.

Sample size

Using the t test method,10 we estimated that we would need to enroll 450 patients to improve awareness by attending physician from 40% (awareness rate of potentially actionable TPAD results as described by Roy et al3) to 60%. This calculation took into account clustering by attending physician (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.03 based on prior work11 and a cluster size of 10 patients with TPADs per attending physician), and a 50% reduction in sample size due to exclusion of patients cared for by physicians randomized to discordant study arms. This provided 80% statistical power. Sample size calculations were conducted using NCSS PASS, V.12 (Kaysville, Utah, USA).

Statistical analysis

We collected patient and physician demographic information from administrative databases. We chose certain physician and patient variables for our multivariable regression model a priori: physician specialty and experience; patient Elixhauser score, number of TPADs, and average length of stay.

Patient and physician characteristics were described using means with SDs, medians with interquartile ranges, and proportions with 95% CIs as appropriate. We analyzed the primary outcome as the proportion of patients discharged with TPADs for whom attending physicians were aware of any TPAD result. We used multivariable regression to adjust for a priori selected covariates (see table 2), and general estimating equations to adjust for clustering by attending physician. We analyzed PCP awareness and awareness of actionable TPAD results similarly. Satisfaction was collapsed into three categories (satisfied, neutral, dissatisfied) and reported as proportions. Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS V.9.2.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes

| Outcome | Intervention | Usual care | Crude OR (95% CI) p value |

Clustered OR (95% CI) p value |

Adjusted* and clustered OR (95% CI) p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome: awareness of TPAD results by inpatient attending physician | |||||

| Inpatient attending physicians aware† | 76% (106/139) | 38% (52/136) | 5.19 (3.08 to 8.74) p<0.001 |

5.19 (2.25 to 11.99) p<0.001 |

6.30 (3.02 to 13.16) p<0.001 |

| Hospitalist | 80% (76/95) | 36% (32/89) | 7.13 (3.74 to 13.83) p<0.001 |

7.13 (2.09 to 24.27) p=0.002 |

13.63 (4.47 to 41.60) p<0.001 |

| Non-hospitalists‡ | 68% (30/44) | 43% (20/47) | 2.89 (1.23 to 6.83) p=0.01 |

2.89 (1.22 to 6.87) p=0.02 |

5.48 (1.90 to 15.81) p=0.002 |

| Secondary outcome: awareness of TPAD results by PCP | |||||

| PCPs aware† | 57% (39/69) | 33% (27/83) | 2.70 (1.39 to 5.22) p=0.003 |

2.70 (1.27 to 5.70) p=0.01 |

3.08 (1.43 to 6.66) p=0.004 |

| Network PCP | 64% (36/56) | 32% (24/74) | 3.75 (1.80 to 7.80) p<0.001 |

3.75 (1.59 to 8.87) p=0.003 |

6.00 (2.27 to 15.91) p<0.001 |

| Non-network PCP | 23% (3/13) | 33% (3/9) | 0.60 (0.09 to 3.99) p=0.66 |

0.60 (0.09 to 4.07) p=0.60 |

Small sample |

| Secondary outcome: awareness of actionable§ TPAD results by physician | |||||

| Inpatient attending physicians aware† | 59% (16/27) | 29% (8/28) | 3.64 (1.18 to 11.18) p=0.02 |

3.64 (0.78 to 17.05) p=0.10 |

4.25 (0.65 to 27.85) p=0.13 |

| PCPs aware† | 65% (13/20) | 48% (13/27) | 2.00 (0.61 to 6.57) p=0.25 |

2.00 (0.62 to 6.47) p=0.25 |

2.15 (0.54 to 8.60) p=0.28 |

*Adjusted for the following covariates from table 1: physician specialty (hospitalist, non-hospitalist; p=0.41, OR 1.22 (95% CI 0.76 to 2.18)); attending physician experience (<10, ≥10; p<0.001, OR 0.37 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.57)); Elixhauser score (≤0, ≥1; p=0.32, OR 0.76 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.14)); number of TPADs per patient (≤2, ≥3, p=0.04; OR 1.49 (95% CI 1.02 to 2.18)); and average length of stay (≤2, ≥3; p=0.93, OR 1.02 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.49)).

†A ‘yes’ response was recorded if the participant responded ‘yes’ when asked if s/he was aware of any TPAD result, or if s/he recalled reviewing a previous email notification including the TPAD result(s).

‡Traditional internists, cardiologists, or other subspecialists.

§TPAD(s) were determined to be actionable by the surveyed physician. Physicians responding to surveys were first asked if at least one TPAD result was actionable and then to list the actionable test result.

PCP, primary care physician; TPAD, test pending at discharge.

Results

Of 1693 patients identified by the system during the study period, 624 were excluded because of discordantly randomized physician pairs (figure 3). One hundred and seventy one patients with concordantly randomized physician pairs were excluded: 103 because of partial random sampling of patients with only microbiology TPAD results, 26 because of the PCP serving as attending physician, and 42 because of surveys not being generated (ie, research staff unavailable). An additional 398 patients (23.5%) were excluded because the PCP was not randomized: the internal ID was in uncoded format for 109 (6.4%), and research staff were unavailable to manually randomize PCPs for 289 (17.1%). Of the latter group, most had a non-network PCP or were discharged before automation of the randomization scheme described above.

Figure 3.

Patient enrollment. Flow of patients identified by the automated email notification system during the study period. Patients with tests pending at discharge (TPADs) discharged from the general medicine and cardiology services were identified by the system. The system was configured to automatically exclude patients with discordant physician pairs and patients for whom the attending physician and primary care physician (PCP) were the same individual. Additionally, it automatically excluded every other patient with only microbiology TPADs. Finally, it excluded patients with TPADs whose PCP could not be identified (ie, missing the internal ID), or whose responsible physicians were not previously randomized (ie, when research staff were unavailable to manually randomize the PCP at time of discharge before the randomization process was automated).

Of the remaining 500 patients, 267 were assigned to intervention, and 233 were assigned to usual care. A total of 267 intervention and 233 usual care surveys were generated for the physicians caring for these patients, respectively. In the intervention arm, 26 patients were excluded: two because of post-discharge test result cancelation, 17 because of a system error, and seven because of incorrectly generated surveys. In the usual care arm, 33 patients were excluded: six because the patient's physician opted out, 10 because a physician was involved in the study design, 15 because of a system error, and two because of incorrectly generated surveys.

Two hundred and forty one surveys were sent to 59 attending physicians caring for the 241 intervention patients (cluster size of 4.08 patients per attending physician). Two hundred surveys were sent to 58 attending physicians caring for the 200 usual care patients (cluster size of 3.45 patients per attending physician). Fifty-five intervention patients and 33 usual care patients had no PCP identified in administrative databases; therefore, these PCPs were not surveyed (ie, randomization was by attending physician alone). Of 241 intervention surveys, 102 (42%) were not completed by 38 attending physicians. Of 200 usual care surveys, 64 (32%) were not completed by 30 attending physicians. Of these 38 and 30 attending physician non-responders, 20 (53%) and 14 (47%) completed a survey on at least one other patient enrolled in the intervention and usual care arm, respectively (ie, these attending physicians completed a survey on one enrolled patient but not another). Overall, of the 59 intervention and 58 usual care attending physicians surveyed, 18 (31%) and 16 (28%) did not complete a single survey on any enrolled patient, respectively. Overall, we sent a total of 441 surveys to attending physicians and received 275 completed responses (attending physician survey response rate 63%). We sent a total of 353 surveys to PCPs and received 152 completed responses (PCP survey response rate 43%; survey response rates for network and non-network PCPs were 52% (131/254) and 21% (21/99), respectively).

Characteristics of intervention and usual care attending physicians were similar across the two arms (table 1). Intervention attending physicians were more experienced and tended to be hospitalists. Characteristics of study patients appeared similar across the two arms. Intervention patients tended to have two TPADs. Characteristics of physicians who did and did not respond to surveys are provided in the online supplementary appendix. Non-respondents were slightly older, more experienced, and more likely to be cardiologists.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of randomized inpatient attending physicians and patients

| Characteristic | Intervention | Usual care |

|---|---|---|

| Inpatient attending physicians | N=59 | N=58 |

| Age (years)—mean (SD) | 46.3 (10.7) | 44.2 (11.0) |

| Male sex—no (%) | 39 (66) | 37 (64) |

| Experience—no (%) | ||

| 5 years or less | 23 (39) | 34 (59) |

| 6–10 years | 19 (32) | 11 (19) |

| 11 years or more | 17 (29) | 13 (22) |

| Specialty—no (%) | ||

| Hospitalist | 20 (34) | 17 (29) |

| Traditional internist | 8 (13) | 5 (9) |

| Cardiologist | 24 (41) | 28 (48) |

| Other subspecialist | 7 (12) | 8 (14) |

| Years employed—mean (SD) | 11.78 (9.60) | 10.74 (8.98) |

| Discharged patients* | N=241 | N=200 |

| Age (years)—median (IQR) | 61.0 (44.0–75) | 59.5 (45.5–73.0) |

| Male sex—no (%) | 114 (47) | 97 (49) |

| Race—no (%) | ||

| White | 149 (62) | 121 (61) |

| Black | 52 (22) | 42 (21) |

| American Indian | 1 (<1) | – |

| Hispanic | 32 (13) | 27 (13) |

| Other | 7 (3) | 10 (5) |

| Socioeconomic status (median income by zip code)—no (%) | ||

| US$39 000 or less | 80 (33) | 60 (30) |

| US$39 001–47 000 | 51 (21) | 47 (24) |

| US$47 001–63 000 | 52 (22) | 43 (21) |

| US$63 001 or more | 53 (22) | 46 (23) |

| Missing data | 5 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Insurance status—no (%) | ||

| Private | 70 (29) | 66 (33) |

| Medicaid | 34 (14) | 26 (13) |

| Medicare | 125 (52) | 96 (48) |

| Self pay | 3 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Other | 9 (4) | 8 (4) |

| Case–severity mix | ||

| DRG weight—median (IQR) | 1.10 (0.80–1.75) | 1.03 (0.80–1.62) |

| No with missing data | 27 | 28 |

| Elixhauser score—no (%) | ||

| −6 or less | 11 (5) | 9 (4) |

| −5 to −1 | 28 (12) | 22 (11) |

| 0 | 31 (13) | 39 (20) |

| 1 to 5 | 56 (23) | 38 (19) |

| 6 to 10 | 41 (17) | 30 (15) |

| 11 to 20 | 44 (18) | 28 (14) |

| 21 or more | 30 (12) | 34 (17) |

| Average Charlson comorbidity score—mean (SD) | 2.06 (2.18) | 2.06 (2.38) |

| Average length of stay (days)—mean (SD) | 5.02 (15.62) | 4.59 (4.96) |

| No of tests pending per patient discharge—no (%) | ||

| 1 | 82 (34) | 71 (36) |

| 2 | 68 (28) | 34 (17) |

| 3–5 | 65 (27) | 54 (27) |

| 6–20 | 23 (10) | 36 (18) |

| 21 or more | 3 (1) | 5 (3) |

| PCP type—no (%) | ||

| Network | 125 (52) | 108 (54) |

| Non-network | 61 (25) | 59 (29) |

| Unidentified | 55 (23) | 33 (17) |

*Of the 441 patient discharges, there were 422 distinct patients; 19 patients were admitted two or more times during the study period.

DRG, diagnosis-related group; PCP, primary care physician.

Outcomes

We observed a statistically significant increase in the rate of awareness of TPAD results by attending physician for patients assigned to the intervention compared with usual care (76% vs 38%, adjusted/clustered OR 6.30, 95% CI 3.02 to 13.16, p<0.001) in the crude, clustered, and adjusted/clustered analyses (table 2). This effect was similar for both hospitalists and non-hospitalists and was consistent throughout the study period (results not shown).

We observed a statistically significant increase in the rate of awareness of TPAD results by PCP for patients assigned to the intervention compared with usual care (57% vs 33%, adjusted/clustered OR 3.08, 95% CI 1.43 to 6.66, p=0.004) in the crude, clustered, and adjusted/clustered analyses (table 2). This effect was observed exclusively for patients with network PCPs; however, the total number of patients with non-network PCPs included in the study was small. There was a significantly increased rate of awareness of actionable TPAD results by attending physicians in unadjusted analyses (59% vs 29%, p=0.02), which was not significant in adjusted/clustered analyses, and showed a trend towards an increased rate of awareness by PCPs (65% vs 48%, p=0.25) for patients assigned to the intervention compared with usual care, respectively. Types of actions taken by attending physicians and PCPs are listed in table 3.

Table 3.

Actions taken by inpatient attending physician or PCP after asked if TPAD result was actionable in surveys

| Type of action taken | TPAD result reviewed by: | |

|---|---|---|

| Inpatient attending physician (n=55) | PCP (n=47) | |

| Patient notified | 9 | 27 |

| Ambulatory (or inpatient) team member contacted* | 34 | 3 |

| Subspecialist contacted | 15 | 5 |

| Further testing/modified treatment | 6 | 15 |

| Referred to ambulatory clinic or emergency room | 1 | 5 |

| Documentation | 3 | 7 |

| Total no of actions taken | 68 | 62 |

*This may have included email correspondence. For example, email messages between intervention attending physicians and network PCPs were occasionally observed in an email inbox monitored by research staff when one party selected ‘reply all’ to the initial automated email notification. Examples of types of correspondence observed between these providers include ordering appropriate antimicrobial therapy for positive Helicocbacter pylori stain on a final gastric biopsy pathology specimen and referring a patient with a suspected systemic lupus erythematosus flare to a subspecialist for a highly positive antinuclear antibody.

PCP, primary care physician; TPAD, test pending at discharge.

For patients assigned to usual care, 15 (11%) attending physician and 14 (17%) PCP survey respondents reported that they were satisfied with their current method of managing TPADs. Ninety-five (70%) attending physician and 54 (65%) PCP survey respondents reported dissatisfaction with their current method of managing TPADs. In contrast, for patients assigned to the intervention, 118 (85%) attending physician and 43 (63%) PCP survey respondents reported that they were satisfied with the method of receiving automated email notifications of TPAD results.

Discussion and conclusions

In this clustered randomized-controlled trial, we observed that the rate of self-reported awareness of TPAD results by physicians caring for patients under usual care is poor, but that this rate significantly increased for attending physicians and PCPs receiving automated email notifications; our strategy nearly doubled the rate of awareness of TPAD results by physicians. For PCPs, this finding was observed for network PCPs (ie, those receiving a carbon copy of the email). Despite providing contact information for non-network PCPs in emails to attending physicians, we did not observe an improvement in awareness in this subgroup; however, the number of patients with non-network PCPs enrolled in our study was small despite our attempt to enhance enrollment by automating randomization and sending faxed surveys. We also observed a trend towards increased awareness of actionable TPAD results by intervention attending physicians and PCPs. Attending physicians and PCPs in both arms stated that they took specific actions after becoming aware of TPAD results. Finally, we observed a low rate of satisfaction with the current system of managing TPADs, but a high rate of satisfaction with our system.

All network physicians in both study arms had access to patients’ TPAD results within the clinical data repository, yet awareness of TPAD results under usual care is clearly poor. Our prior experience underscores the importance of considering workflow integration and mitigating alert fatigue when considering HIT solutions.8 Moreover, TPAD results need to be highlighted during care transitions, and clearly delineated policies for communication and transfer of responsibility between responsible physicians must be in place.8 9 12 13 We attribute our findings largely to the design of our system, which automates an otherwise manual process by facilitating timely delivery of TPAD results to responsible physicians within the accepted workflow.9 Specifically, our strategy leverages our institutional culture of using secure, network email to communicate about patient care, highlights (via the subject line) and communicates TPAD results (via a detailed transcript) to the responsible attending physician in compliance with our institutional policies (thereby mitigating the diffusion of responsibility that could occur when multiple physicians care for a patient14), and provides a method of initiating communication with the patient's PCP to facilitate transfer of responsibility (eg, by carbon copying and including contact information).

Our findings build on prior work in this area. Studies conducted at our institution by Roy et al3 and El-Kareh et al15 show similar rates of awareness of TPAD results under usual care (35–40%). El-Kareh et al demonstrated a nearly twofold increase in documentation of follow-up actions after receipt of automated email notifications of microbiology culture results,15 suggesting that awareness of TPAD results by attending physicians doubled under this strategy, similar to the effect found in our study. Our intervention, which incorporates functionality from the microbiology notification system of El-Kareh et al, expands this strategy to all test types. Additionally, it provides an opportunity for electronic dialog between the attending physician and network PCP, with the intent of facilitating acknowledgement and communication of context (eg, reason for testing, implications of the result). This was corroborated by our review of actionable TPAD survey data and observation of occasional messages between intervention attending physicians and network PCPs in the study email inbox monitored by research staff (table 3).

This study has several limitations. We have previously acknowledged the limitations of the intervention itself.9 In this study, we assumed that every patient had an attending physician and PCP. While the system reliably identified the attending physician for all patients with TPADs (ie, patients cannot be admitted without an assigned attending physician and this information was rigorously updated by admissions staff), a non-trivial proportion of patients had a PCP without a coded ID. These patients were excluded from the study because they could not be randomized. Because these patients’ PCPs would not have received automated emails (which also required a coded ID), we have probably overestimated the effect of the intervention on PCP awareness under current conditions. Specifically, if we included these 109 patients and assumed half had been assigned to the intervention arm but had a PCP awareness of TPADs as in the usual care arm, then our PCP awareness rate would have been 46% vs 38% as opposed to 57% vs 38%. Second, this study was designed neither to detect whether appropriate downstream actions were taken in response to actionable TPAD results as determined by independent physician review, nor to detect decreases in post-discharge adverse events. We acknowledge that self-reported awareness by physicians does not necessarily translate into reduction of patient harm, but awareness is nonetheless a necessary intermediary step in improving test result follow-up rates. Furthermore, to determine the rate of awareness by physicians, we included the patient's TPAD results in the survey instrument in both study arms; thus, we would not be able to attribute any differential impact on downstream actions to our intervention alone. Nevertheless, in secondary analyses, we observed a trend towards improved awareness of TPAD results by physicians, who then took specific actions (table 3). Third, we could not determine if the effect of our intervention would persist beyond the study period, but an analysis of survey responses over time suggests that the effect was sustained over the course of the 8-month trial. Our efforts at minimizing alert fatigue may have contributed to this sustained effect. Fourth, we did not study our intervention for other services (eg, surgery) that may vary with regard to types of TPAD results, workflow, and expectations for follow-up. Fifth, we were potentially biased by emailing surveys to network physicians (ie, the same modality used to send TPAD results in the intervention arm). To reduce this bias, we sent surveys to network physicians via fax if they did not respond by email; in practice, few responded in this way (most tended to complete the web-based survey after receiving the fax). However, even if all attending physician survey non-respondents in the intervention arm had the same TPAD awareness rate as those in the usual care arm, there still would have been a significantly improved awareness rate in the intervention versus usual care arm (60% vs 38%, p<0.001 in unadjusted analyses). Sixth, the rate of response to surveys faxed to non-network PCPs was low, which limited our power to detect an effect on this subgroup and may have led to response bias. Lastly, there were differences between physicians who responded to the survey and those who did not (eg, specialty, experience), but we adjusted for potential confounding in our analyses.

Future studies should assess the impact of this strategy on downstream actions taken after discharge, and compare the relative effect of this intervention on network versus non-network PCPs, readmission rates, and post-discharge resource utilization (ie, test ordering). Further work is required to design a system to notify non-network physicians reliably (eg, providing access to selected portions of the network EMR or notifying them via secure messaging) and to ‘close the loop’ on these results (eg, acknowledging results and ensuring follow-up). Finally, future research should assess the feasibility of this strategy for other clinical services, hospitals, healthcare networks, and EMR platforms. Although we developed our notification system within a proprietary EMR, the strategy of highlighting and automatically notifying responsible physicians of TPAD results via external messaging (eg, network email, alphanumeric pagers, or push-notifications to a mobile application) is practical and could be leveraged by most vendor-based EMR systems.

In conclusion, automated email notification is an effective strategy for improving awareness of TPAD results by responsible physicians. It is practical for any healthcare network that uses secure external messaging for clinical communication, assuming accurate identification of physicians involved in a patient's transition. In theory, this strategy could facilitate electronic acknowledgement, transfer of responsibility, and subsequent actions, thereby improving patient safety during care transitions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed meaningfully to the conception of the intervention, design and conduct of the study, and/or data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafting, editing, and revising the manuscript;, and approving the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), grant number R21 HS018229-01.

Competing interests None.

Ethics approval: Partners Institutional Review Board (Partners Human Research Council).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:161–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ 2004;170:345–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:121–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandhi TK. Fumbled handoffs: one dropped ball after another. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:352–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Thomas EJ, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:488–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, et al. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:646–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007;297:831–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalal AK, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Lessons learned from implementation of a computerized application for pending tests at hospital discharge. J Hosp Med 2011;6:16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalal AK, Schnipper JL, Poon EG, et al. Design and implementation of an automated email notification system for results of tests pending at discharge. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:523–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:771–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callen JL, Westbrook JI, Georgiou A, et al. Failure to follow-up test results for ambulatory patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1334–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sittig DF, Singh H. Improving test result follow-up through electronic health records requires more than just an alert. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1235–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Mani S, et al. Timely follow-up of abnormal diagnostic imaging test results in an outpatient setting: are electronic medical records achieving their potential? Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1578–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-1986-8. El-Kareh R, Roy C, Williams DF, et al. Impact of automated alerts on follow-up of post-discharge microbiology results: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.