Abstract

Objective

We conducted a systematic review identifying users groups’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic prescription (e-prescribing) in primary care.

Methods

We included studies following these criteria: presence of an empirical design, focus on the users’ experience of e-prescribing implementation, conducted in primary care, and providing data on barriers and facilitators to e-prescribing implementation. We used the Donabedian logical model of healthcare quality (adapted by Barber et al) to analyze our findings.

Results

We found 34 publications (related to 28 individual studies) eligible to be included in this review. These studies identified a total of 594 elements as barriers or facilitators to e-prescribing implementation. Most user groups perceived that e-prescribing was facilitated by design and technical concerns, interoperability, content appropriate for the users, attitude towards e-prescribing, productivity, and available resources.

Discussion

This review highlights the importance of technical and organizational support for the successful implementation of e-prescribing systems. It also shows that the same factor can be seen as a barrier or a facilitator depending on the project's own circumstances. Moreover, a factor can change in nature, from a barrier to a facilitator and vice versa, in the process of e-prescribing implementation.

Conclusions

This review summarizes current knowledge on factors related to e-prescribing implementation in primary care that could support decision makers in their design of effective implementation strategies. Finally, future studies should emphasize on the perceptions of other user groups, such as pharmacists, managers, vendors, and patients, who remain neglected in the literature.

Keywords: Electronic Prescribing, Systematic Review, Implementation Factors, Users' Perceptions, Primary Care

Introduction

Prescription and renewal of patient drugs are among the most commonly used treatments in primary care.1 The prescription process is a major concern for public health policies and efforts are required to promote the continuous improvement of optimal and adequate prescription in primary healthcare. Studies have shown that errors related to drug prescription are common and avoidable2; they are also the cause of a high level of morbidity and mortality recorded among populations.3–5 Taking into account the increased complexity of health conditions caused by an aging population and multi-morbidity, patients’ exposure to iatrogenic damage caused by drug misuse and interactions is likely to grow in proportion to these changes. It is therefore essential to improve the quality and safety of prescribing, as well as optimize the use of medicines, making it a priority for current health policies.2

In this context, the computerization of prescriptions based on modern information and communication technologies (ICT) is supported in many developed countries.6 Electronic prescription (e-prescribing) is intended to be an inter-operational platform which facilitates the exchange of patients’ drug therapy information between health professionals and organizations in primary care and community pharmacies.7 E-prescribing can improve the drug prescription process by responding to specific user needs as well as reducing inconsistencies.2 E-prescribing is a promising technology that has the potential to improve the quality of drug use especially in ambulatory and primary care, where treatments for chronic diseases are used for extended periods.8

Motulsky et al9 indicate that stakeholders in many countries have made considerable efforts in order to promote the widespread use of e-prescribing by health professionals. However, despite major investments and widespread availability of e-prescribing systems, health providers do not always make use of this technology for prescribing and renewal of treatments.10–13

Cresswell et al2 assert that e-prescribing management computer systems implemented in medical clinics vary considerably in terms of functionality, level of interoperability, cost, and involvement of stakeholders in the strategic choices related to the implementation of these technologies. Problems such as a predetermined deficit in norms governing the attribution of public contracts, a lack of functional specifications for choices that stakeholders have adopted, and a lack of harmonization in the systems implementation strategies may also accentuate the degree of implementation of e-prescribing.14 15

As main users of e-prescribing systems, healthcare professionals are best positioned to identify the barriers and facilitators they face in their work environment that could affect the success of these systems. However, most studies related to e-prescribing implementation in primary care are fairly recent and few have addressed end-users’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators in the implementation process.7 Considering users’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to the implementation of e-prescribing systems could help reveal which implementation strategy could be successful.

In order to expose these barriers and facilitators, we conducted an exploratory systematic review on the implementation of e-prescribing in the daily work setting of primary healthcare providers. This review sought to answer this question: What are users’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to e-prescribing implementation in primary care?

Methods

Search strategy

An information specialist developed the literature search strategy from the research question. We searched PubMed to identify applicable articles published within a period of 10 years (from January 1, 2002 to December 11, 2012), in order to focus on more contemporary systems. See online supplementary appendix 1 for search parameters used.

Selection criteria

We included studies with an empirical design, either qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods. These studies should present a clearly stated data collection process as well as research methods and measurement tools used. As such, editorials, comments, position papers, and unstructured observations were excluded from this review.

Included studies focused on the users’ experience of e-prescribing implementation. User groups considered included: physicians, clinical staff (including nurses), pharmacists, pharmacy staff, and others (patients, IT staff, and managers). We included studies that took place in primary care (including ambulatory or community healthcare settings). However, studies involving secondary and tertiary care levels could also be included, as long as there was a linkage of the e-prescribing system with primary care settings.

Also, studies had to provide data on barriers and facilitators to e-prescribing implementation in their results or discussion sections to be included. These barriers or facilitators had to be based on empirical evidence.

If a study was reported in more than one publication and presented the same data, we only included the most recent publication. However, if new data were presented in multiple publications describing the same study, all were included. Publications were not excluded based on language used.

Screening, data extraction, and presentation

Two authors (ENS and SG) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts and reached consensus on included studies. A third author (MPG) confirmed included and excluded studies. Full text review of the selected studies was done by three authors (JPG, ENS, and SG).

We used a validated data extraction grid from previous research on the classification of barriers and facilitators to ICT implementation in healthcare settings.16 The data extraction grid developed used both inductive and deductive methods, following established theoretical concepts,17–19 particularly the technology acceptance model20 and the diffusion of innovations theory.21

We developed the data extraction grid in Microsoft Excel 2010. We took all included publications, and three reviewers (ENS, JPG, and SG) independently read and identified sections of the publications that presented a relevant barrier or facilitator to the implementation of e-prescribing from the users’ perspective. ENS and JPG coded these selected sections in the program. We also extracted data regarding: year of publication, country, study design (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods), theoretical framework (present or absent), type of participants, care setting, technology used, objectives of the study, data collection methods, and main findings.

We used the logical model of healthcare quality proposed by Donabedian, coupled to the themes proposed by Barber et al,22 as the analytical framework for summarizing our findings.23 24 We transposed extracted data into this framework using thematic analysis. This framework highlights e-prescribing users’ perceptions under the dimensions of system functionality, human perspectives, and organizational factors defined by Barber et al,22 23 which are classified according to the structure, process, and outcomes categories from the Donabedian's model, thus providing a 3×3 thematic classification matrix.

Study quality assessment

We used the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT)—a scoring system which presents evaluation criteria for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies—proposed by Pluye et al,25 for appraising the quality of included studies. Two authors (ENS and JPG) independently screened each study and gave it a quality score. No studies were excluded based on their scores (results for quality assessment available on request).

Results

Included studies

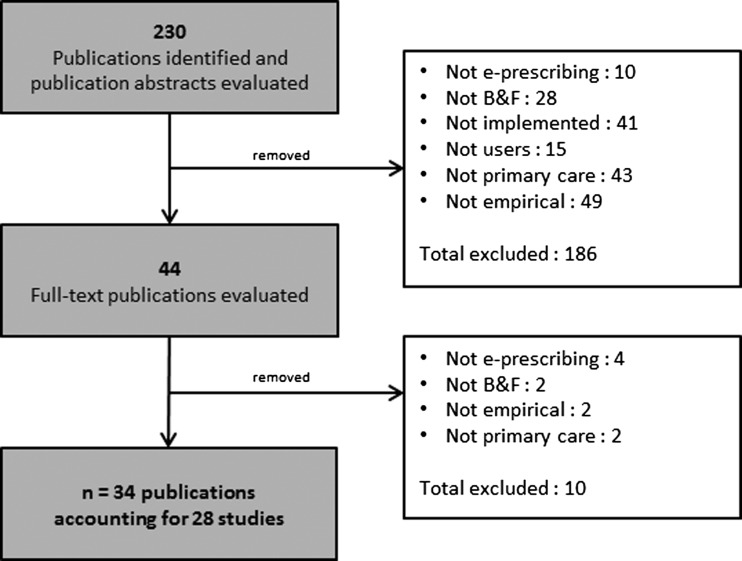

In total, we identified 230 references from bibliographic databases, of which we retained 44 publications for full-text review. After applying the inclusion criteria, we excluded 10 of these publications: four were not about e-prescribing, two did not mention barriers or facilitators, two did not possess an empirical design, and two did not concern primary care. The review therefore included 34 publications,1 7 9 12 13 26–54 corresponding to 28 individual studies, because paired publications by Abramson,28 34 Crosson,30 50 Grossman,7 33 Lapane and Goldman,38 42 Weingart,44 47 and Tamblyn49 53 were considered as one study. The number of studies included at various stages of the review process is described in a study selection flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of included studies are summarized in online supplementary appendix 2. The most frequent types of technology covered were: e-prescribing system (n=20 studies),9 13 26 27 29–32 35 38–44 46–51 53 54 electronic health records (EHR) with e-prescribing system (n=4),28 34 37 45 52 both of these systems (n=3),1 7 12 33 and the personal digital assistant (PDA)36 with prescribing software and drug information. Computerized physician (or prescription, or provider) order entry systems (CPOE) were considered in the search, but not included since they are traditionally used in secondary and tertiary care and are confined within hospital settings,55–58 which are not the focus of this review.

The majority of studies took place in North America (n=22, 78.6%). Of those, 20 are from the USA1 7 12 13 26–31 33–39 41 42 44 47 48 50 51 54 and two are from Canada.9 49 53 A smaller number of studies (n=5, 17.9%) were conducted in European countries: Sweden (n=3)40 43 45 and the UK (n=2).32 52 We also included one study from Singapore.46 All studies were published since 2005 and more than half of the included articles were published since 2010 (n=20, 58.8%).

Twelve studies (42.9%) exclusively involved physicians,1 12 13 27 28 34 36 37 43–45 47 49 53 54 while another two studies targeted exclusively pharmacists (7.1%).35 40 Six studies included physicians and their staff (21.4%),30 31 38 39 41 42 50 52 three studies involved pharmacists and their staff (10.7%),26 32 48 and five studies (17.9%) include more than one of these groups and/or other types of users.7 9 29 33 46 51

Twelve of the studies (42.9%) were quantitative, primarily using surveys.13 27 31 35 36 40 43 45 46 48 49 53 54 Eleven studies (39.3%) had a qualitative research approach, using one or more of the following data collection methods: interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, observations, and document analysis.1 7 9 12 26 30 32 33 39 41 50–52 Five studies (17.9%) used a mix of both approaches.28 29 34 37 38 42 44 47 More than one third of the studies (35.7%) included a theoretical framework.9 26 31 32 35 36 39 40 53 54

Results presentation

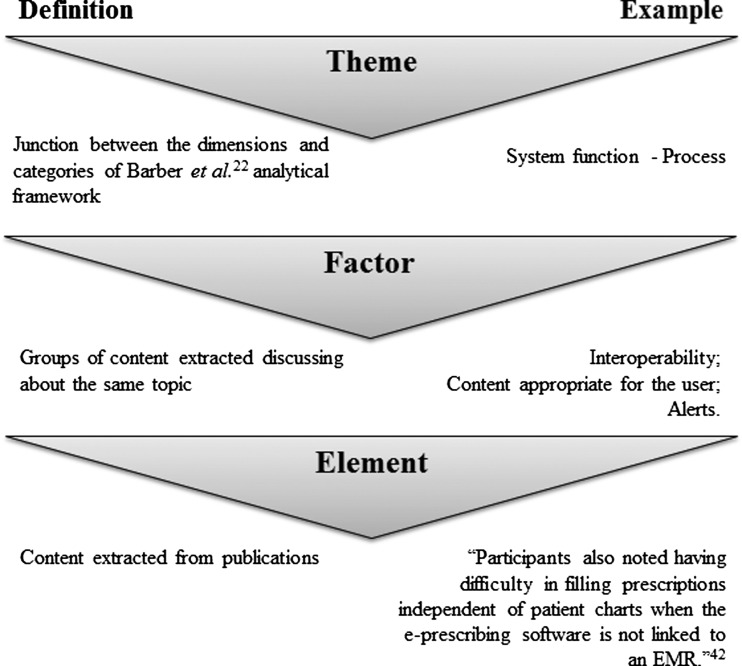

We grouped factors representing barriers and facilitators to e-prescribing implementation into the nine broad themes of the analytical framework. Each theme is divided into factors representing the content extracted from the publications (explanation for each term used can be found in figure 2). Nearly all factors were perceived both as a facilitator and as a barrier, depending on the context. It is worthwhile to mention that overall more facilitators (332) than barriers (264) were mentioned. The majority of factors were common to all user groups. A summary of extracted data is presented in table 1 (see online supplementary appendix 3 for full classification). Results regarding each of the nine themes from our analytical framework are presented below.

Figure 2.

Definition of the terms used in the review.

Table 1.

Users’ perception in relation to the principal factors raised in the studies

| Themes | System function | Factor raised by: | Human perspectives | Factor raised by: | Organizational factors | Factor raised by: | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | CS | Ph | PhS | O | P | CS | Ph | PhS | O | P | CS | Ph | PhS | O | ||||

| Structure | Design and technical concerns | X | X | X | X | X | Welcoming/resistance to e-prescribing | X | X | X | X | X | Resources | X | X | X | X | |

| Familiarity and ability with IT | X | X | X | Implementation strategies | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Perceived ease of use | X | X | X | X | Macro organization | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Perceived usefulness | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Process | Interoperability | X | X | X | X | Perception of risk-benefit equation | X | Professional interaction | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Content appropriate for user | X | X | X | Productivity (efficiency) | X | X | X | X | Work process | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Alerts | X | Patient/clinician interaction | X | Organizational support | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Outcome | Patient's security | X | X | X | X | Times issues | X | X | X | Change in task | X | X | X | |||||

| Satisfaction about content available | X | X | X | X | Observability | X | X | X | Cost issues | X | X | |||||||

| Data accuracy and legibility | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

CS, clinical staff (nurses, practice staff); O, others (managers, patients, IT staff); P, physicians; Ph, pharmacists; PhS, pharmacy staff.

System functions

Structure

Design and technical concern aspects of e-prescribing implementation was the most frequently mentioned factor, extracted 82 times over the 90 elements of that theme. This factor was mostly considered as a barrier to e-prescribing implementation by all user groups. The most frequently mentioned barriers were the limitations related to software or hardware, and system problems (ie, prescriber had to manually replace data, complexity of the commercial system, or inadequacies of current e-prescribing product).1 7 9 13 26–31 33 34 38 40–42 44 46–48 50 51 53 54 Other factors belonging to this theme were reported by physicians and pharmacists who had concerns about the system reliability or dependability (7)7 30 31 45 51 as well as quality standard (1).38

Process

Interoperability (43 elements), involving more than one organization and/or setting of care, was cited three times more frequently as a barrier (32 times)7 13 26–28 37 38 42 45–48 51 54 than as a facilitator (11 times)7 28 29 39 42 44 46 48 54 for e-prescribing implementation. Generally, inadequate interfacing with other IT systems was considered as a barrier by users and was mainly related to the uncertainty about which local pharmacies accept electronic prescriptions. Content appropriate for the user (27) was perceived as a barrier when prescribing history was not updated,31 33 and did not present clinically relevant data allowing an overview of patient adherence to their prescriptions.33 49 51 An overwhelming number of different forms and strand medications available in a search query or a low level of confidence in formularies were also mentioned as barriers.1 7 26 42 52 Otherwise, the possibility to have an overview of patient drugs,33 45 47 a follow-up of patient adherence to their prescriptions,42 as well as access to lab results51 were mentioned as facilitators to e-prescribing implementation. Moreover, reminders for patient with chronic disease52 and electronic medication renewal38 47 were appreciated by physicians.

Alerts (17) were reported as barriers due to their frequency and their lack of relevance,27 28 39 47 51 52 but were considered useful when prescribing an unfamiliar medication to avoid harmful interactions, to look something up in a drug or medical reference, or to change the way they monitored a patient.28 34 44 46 47 51 Lack of generic substitution options (5) or lack of its flexible options was also reported as a barrier.9 27 33 53

Outcome

Overall, the perception that e-prescribing would improve patient security (21 elements) was a facilitator to its implementation.7 13 28 34 35 37 40 41 43–48 51 54 Moreover, physicians reported that e-prescribing would increase the quality of care.7 13 41 43–45 Satisfaction about content available (21)1 7 9 13 26 28 30 33 36 39 44 45 51 54 and data accuracy and legibility (22)7 13 26 36 37 39 40 44 46–48 were also reported as important outcomes of the system function. Physicians reported privacy and security concerns (7) as barriers at pre-implementation, but the system is reported to be safe post-implementation.9 39 40 43 54

Human perspective

Structure

Agreement with e-prescribing was the most cited factor of this theme (31 elements). Resistance to change was observed among physicians, particularly when they did not see an added value of e-prescribing9 13 36 or when they perceived inadequate decision support.49 52 Also, they did not want to solve implementation problems and believed this should be done by clinical staff.41 50 51 Practice using both prescribing systems (traditional and electronic) at the same time generally discontinued the implementation process of e-prescribing until the expected final adoption.1 7 50 51 However, physicians and pharmacists who were voluntarily enrolled in the program had more favorable opinions and positive attitudes about the technology.7 30 37 45–47 50 53 54 Clinical staff considering the e-prescribing benefits welcomed the opportunity to expand their job responsibilities.1 39 51 Pharmacy owners were resistant to e-prescribing implementation when it involved a top down decision from pharmacy chains and preferred to trust their own systems regarding prescriber and practice contact information.1 9

Factors specific to the e-prescribing structure also included perceived usefulness (12),33 36 37 40 41 47 51 ease of use (13),13 26 28 33 36 39–41 44 45 47 familiarity with technology in general or with e-prescribing (14),7 9 13 36 45 46 48–50 53 patients’ attitudes and preferences towards e-prescribing (7),7 37 43 44 47 51 54 and self-efficacy (belief in one's competence to use the e-prescribing) (4),38 39 46 standing for half of the elements of this theme.

We found eight other factors related to human perspective linked to the structure (representing a total of 38 elements), but these were less cited in the studies (eg, socio-demographic characteristics like age, gender, and experience, and support and promotion of e-prescribing by colleagues).

Process

Productivity (efficiency) represented 25 of the 45 elements for that theme and was perceived more frequently as a facilitator7 9 13 34 36 38 39 41 44–46 48 51 52 54 than a barrier.1 27 28 47 The other factors were patient/clinician interaction (6),29 38 39 41 42 54 autonomy (4),1 51 perceptions of other professionals’ performance (3),1 9 38 confidence in e-prescribing developer and vendor (3),42 47 50 impact on clinical uncertainty (2),7 29 and risk–benefit equation (2).38 49

Outcomes

Time issues represented 16 of the 35 extracted elements for that theme. Physicians and pharmacists have reported gains in time at post-implementation stage,29 35 37 38 43 45 54 but this was not the case at the pre-implementation or transition phases, where they believe that it was not the best use of their time.27 41 50 However as an outcome expectancy (8), physicians and clinical staff expected the system to be useful to improve patient care with multiple, complex problems.35 39 50 Observability (8)29 37 39 42 46 54 was seen as a facilitator since physicians were able to view the medication traceability compliance of patients. Finally, impact on professional security was also mentioned.9 43

Organizational context

Structure

The resources factor, including information technology support, training, as well as material and human resources, accounted for 29 of the elements of that theme.1 7 9 12 28 29 35 37–39 42 46 47 50 51 54 Factors related to implementation strategies—such as a strategic plan to implement e-prescribing, the participation of end-users in the implementation, organizational readiness, as well as incentive and innovation structures—stood for 17 of the extracted elements.27 29 32 39 41 42 50 51 53 54 Characteristics of the health structure factors, referring to setting of care,35 54 practice size,12 status,12 54 physician salary structure,9 and workforce shortage9 accounted for seven elements extracted. Staff skills such as the influence of leadership were mentioned three times. Fifteen macro organizational elements were extracted and are mainly related to financial support29 47 51 and healthcare policies.27 33 35 37 51 53 54

Organizational context

Process

Work process was the most important factor of this theme (24 elements). When e-prescribing was integrated, work process was facilitated and workflow was improved.1 13 33 37–42 53 However, these are reported as barriers in the transition phase.7 9 13 26 27 32 34 54 The organizational aspect of professional interaction, including team spirit,39 relation between different health professionals,7 9 47 48 and collaboration effort47 50 accounted for 10 of the extracted elements. The other factors in that theme were barriers related to the lack of organizational support to provide a central, up-to-date source of data, drug code, and formularies.27 30 38 51 54

Outcomes

Again, the outcomes at the post-implementation stage were reported as improvements, but were seen as barriers during the implementation process mainly for the time saving factor (23 elements). Time was saved, among others, by reducing staff time spent processing prescriptions38–40 42 43 46 47 51 52 and their renewal.7 53 The pattern of improvement perceived after implementation is observed for cost issues (11)7 13 27 35 38 43 51 53 54 and change in task (15),7 9 26–28 37 42 46 48 53 54 including additional tasks, work flexibility, and impact on business practices.

Discussion

With this exploratory systematic review, we wanted to identify users’ perception of barriers and facilitators to implementing e-prescribing. From the 28 included studies, users’ perceptions mostly relate to these factors: design and technical concerns, interoperability, content appropriate for the users (relevance), agreement with e-prescribing (welcoming/resistant), productivity (efficiency), and resources. These factors reveal that users want a functional, accessible, and supported e-prescribing system that responds to their professional needs.33 34 39 46 51 Also, the implemented system needs to possess features that enable facilitated exchange between organizations,37 38 but also allows a more coordinated and effective care.39 Furthermore, the organization should put emphasis on education and training at the pre-implementation stage to ensure a better transition.46 50 54

Users’ perception of productivity is prevalent in terms of facilitators. For 80% of the elements found under that factor, e-prescribing seems to improve productivity, allowing overall accessibility to the medication history as well as improving efficiency and quality of care. The same observation can be made about the availability of resources, where 62% of the elements are perceived as facilitators when users receive good support and training in addition to an adequate access to material resources.

On the other hand, users perceive more barriers than facilitators regarding interoperability (74.4%). Users believe that the time taken to transmit a prescription to the pharmacy can be longer, the compatibility of pharmacists’ and physicians’ systems can be problematic, the connectivity with EHR is lacking, and they perceive a gap in communication. The unavailability of a way to externally purchase patient treatments that are not available at the pharmacy and the obligation to make a phone call to obtain prior authorization to deliver a treatment afterwards are also seen as important barriers to interoperability. Moreover, design and technical concerns are also perceived more often as barriers (65.9%). The elements that emerge from that are mainly related to updating data, functional disorders of the system, irrelevant alerts, the uncertainty on the real doses to prescribe, and the impossibility to validate a prescription electronically.

Moreover, some factors that can be seen as barriers in the early stages or before the implementation may become facilitators later on in the process of implementation. The opposite is also true. Some barriers that may arise during the first steps of implementation have a solution in the next steps of the process, such as initial transmission problems solved7 and pharmacies accepting more and more e-prescriptions.28 Also, time and efficiency can be gained with e-prescribing in the later stages, whereas the opposite is observed during the beginning of implementation.7 26 28 39 47 On the other hand, some features may seem interesting to the users at first glance but can cause some serious problems when used: errors may arise using default settings,28 42 and some information may be unreliable,1 51 inconsistent,26 33 51 54 or even superfluous.7 26–28 39 47 51 52 Furthermore, the feature may not work.7 13 28

Studies on e-prescribing implementation are quite recent. Indeed, the majority of studies were published since 2010. This technology gained interest recently due to its promises for improving patient care in a context of increased healthcare complexification.11 27 29 33 34 Moreover, one third of the studies include a theoretical framework, which is superior to the 21% reported in a systematic review on EHR implementation by McGinn et al.59

It is worth mentioning that there is a change in users’ perceptions between the different phases of e-prescribing implementation. This is most apparent between the pre-implementation phase, where non-users and future users have a less favorable opinion of e-prescribing, and the transition and post-implementation phases, where the opinion on e-prescribing becomes more favorable with more frequent use of the technology.13 39 43 45 48 50 51 54 More importantly, attitudes also have an important influence on the adoption of e-prescribing. Indeed, a positive attitude towards e-prescribing contributes to its successful adoption. Conversely, users who believe that e-prescribing has no value are less inclined to use the technology when it is implemented. This attitude can also change during the transition process, depending on the evolution of users’ perceptions regarding e-prescribing.53 The transition process is decisive in the full adoption of e-prescribing by an organization: a negative attitude can potentially lead to the abandonment of the technology,1 7 9 36 41 50–52 whereas a positive attitude is more likely to lead to a favorable adoption of e-prescribing.1 7 30 39 45–47 50 53 54 These findings can be addressed using Azjen's theory of planned behavior.39 60

Even though the importance of health managers and public involvement in innovative technology implementation and diffusion is recognized, their perceptions remain under-studied.61–63 In this review, physicians’ perceptions were addressed in 75% of included studies (21.4% for clinical staff), whereas those of pharmacists (and their staff) appeared in 28.6% of studies.

Perceptions from other user groups (managers, IT staff, and patients) are almost absent from the reviewed literature, accounting for 7% of studies, making it difficult to consider their perspectives, even if they could influence the success of e-prescribing implementation.54

Limitations

Our results must be interpreted with some caution due to the limitations of this review. First, we only used one bibliographic database (PubMed) in the literature search. Thus, it is possible that relevant studies published in journals that are not indexed in PubMed are not included, but due to the explorative nature of our review and the percentage of duplicates reported between multiple databases,64 65 we think that we retrieved most current work related to e-prescribing implementation. Second, since we based the analysis of our findings on a predetermined framework, the use of other theoretical or analytical frameworks could reveal different perspectives. Nonetheless, we deem that the chosen framework answers adequately the question of our systematic review and provides a logical and useful model of factors affecting e-prescribing implementation. Finally, the findings that are presented only relate to the content that has been published. We did not contact authors of included studies for supplementary information. We think that the editing policies applied in the scientific press ensure that we had access to sufficient content to meet our objectives. In the end, we were able to conduct this exploratory review following the standards of mixed-methods systematic reviews.25

Conclusion

The findings reported in this review provide evidence that design and technical concerns, interoperability, relevance of the data, attitude towards e-prescribing, productivity, and available resources are important factors to the implementation of e-prescribing for the users. Implementation strategies should focus on these factors in order to facilitate the adoption of this technology. It is interesting to note that some factors can be perceived as barriers or as facilitators depending on the implementation phase of e-prescribing, and can change in nature (changing to a barrier or a facilitator) during the process of implementation. Moreover, attitudes users and future users have in relation to e-prescribing and its implementation may have an influence on the success of the adoption of the technology. Finally, future studies should put the emphasis on the perceptions of other user groups, such as pharmacists, managers, vendors, and patients, whose perspectives remain overlooked in the literature.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CS and MPG conceived the study. SG searched the database. ENS and SG reviewed all titles and abstracts. MPG confirmed included studies. ENS, JPG, and SG completed the full text review of selected studies. ENS, JPG, and SG extracted and analyzed the data. ENS, JPG, and SG drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This study is supported by a service contract from Canada Health Infoway (No. 2284-002-R1). The funding source had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Crosson JC, Etz RS, Wu S, et al. Meaningful use of electronic prescribing in 5 exemplar primary care practices. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:392–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cresswell K, Coleman J, Slee A, et al. Investigating and learning lessons from early experiences of implementing ePrescribing systems into NHS hospitals: a questionnaire study. PLoS One 2013;8:e53369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roughead EE, Gilbert AL, Primrose JG, et al. Drug-related hospital admissions: a review of Australian studies published 1988–1996. Med J Aust 1998;168:405–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneeweiss S, Gottler M, Hasford J, et al. First results from an intensified monitoring system to estimate drug related hospital admissions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:196–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell DS, Friedman MA. E-prescribing and the Medicare modernization act of 2003. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1159–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman JM, Cross DA, Boukus ER, et al. Transmitting and processing electronic prescriptions: experiences of physician practices and pharmacies. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:353–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eslami S, Abu-Hanna A, de Keizer NF. Evaluation of outpatient computerized physician medication order entry systems: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:400–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motulsky A, Sicotte C, Lamothe L, et al. Electronic prescriptions and disruptions to the jurisdiction of community pharmacists. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:121–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desroches CM, Agarwal R, Angst CM, et al. Differences between integrated and stand-alone E-prescribing systems have implications for future use. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:2268–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surescripts, LLC. Advancing healthcare in America: 2009 national progress report on E-prescribing. Surescripts LLC, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman JM. Even when physicians adopt e-prescribing, use of advanced features lags. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change 2010;133:1–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CJ, Patel MH, Schueth AJ, et al. Perceptions of standards-based electronic prescribing systems as implemented in outpatient primary care: a physician survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:493–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenhalgh T, Stramer K, Bratan T, et al. Adoption and non-adoption of a shared electronic summary record in England: a mixed-method case study. BMJ 2010;340:c3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crowe S, Cresswell K, Avery AJ, et al. Planned implementations of ePrescribing systems in NHS hospitals in England: a questionnaire study. JRSM Short Rep 2010;1:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagnon MP, Desmartis M, Labrecque M, et al. Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. J Med Syst 2012;36:241–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson JG. Social, ethical and legal barriers to e-health. Int J Med Inform 2007;76:480–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yarbrough AK, Smith TB. Technology acceptance among physicians: a new take on TAM. Med Care Res Rev 2007;64:650–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 1989;13:319–40 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers EM. The Diffusion of Innovations. New York: The Free Press, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber N, Cornford T, Klecun E. Qualitative evaluation of an electronic prescribing and administration system. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:271–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q 1966;44:166–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donabedian A. The quality of medical care. Science 1978;200:856–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pluye P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, et al. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:529–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odukoya O, Chui MA. Retail pharmacy staff perceptions of design strengths and weaknesses of electronic prescribing. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:1059–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jariwala KS, Holmes ER, Banahan BF, 3rd, et al. 3rd. Adoption of and experience with e-prescribing by primary care physicians. Res Social Adm Pharm 2013;9:120–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abramson EL, Patel V, Malhotra S, et al. Physician experiences transitioning between an older versus newer electronic health record for electronic prescribing. Int J Med Inform 2012;81:539–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothbard AB, Noll E, Kuno E, et al. Implementing an e-prescribing system in outpatient mental health programs. Adm Policy Ment Health 2013;40:168–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crosson JC, Schueth AJ, Isaacson N, et al. Early adopters of electronic prescribing struggle to make meaningful use of formulary checks and medication history documentation. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas CP, Kim M, McDonald A, et al. Prescribers’ expectations and barriers to electronic prescribing of controlled substances. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:375–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey J, Avery A, Waring J, et al. A constructivist approach? using formative evaluation to inform the electronic prescription service implementation in primary care, England. Stud Health Technol Inform 2011;169:374–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grossman JM, Boukus ER, Cross DA, et al. Physician practices, e-prescribing and accessing information to improve prescribing decisions. Res Brief 2011;20:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abramson EL, Malhotra S, Fischer K, et al. Transitioning between electronic health records: effects on ambulatory prescribing safety. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:868–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clauson KA, Alkhateeb FM, Lugo KD, et al. E-prescribing: attitudes and perceptions of community pharmacists in Puerto Rico. Int J Electron Healthc 2011;6:34–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galt KA, Siracuse MV, Rule AM, Physician use of hand-held computers for drug information and prescribing. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al., eds. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 4: Programs, Tools, and Products). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2005:93–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amirfar S, Anane S, Buck M, et al. Study of electronic prescribing rates and barriers identified among providers using electronic health records in New York City. Inform Prim Care 2011;19:91–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lapane KL, Rosen RK, Dubé C. Perceptions of e-prescribing efficiencies and inefficiencies in ambulatory care. Int J Med Inform 2011;80:39–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devine EB, Williams EC, Martin DP, et al. Prescriber and staff perceptions of an electronic prescribing system in primary care: a qualitative assessment. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahimi B, Timpka T. Pharmacists’ views on integrated electronic prescribing systems: associations between usefulness, pharmacological safety, and barriers to technology use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011;67:179–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agarwal R, Angst CM, DesRoches CM, et al. Technological viewpoints (frames) about electronic prescribing in physician practices. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:425–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldman RE, Dubé C, Lapane KL. Beyond the basics: refills by electronic prescribing. Int J Med Inform 2010;79:507–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinschaden T, Petersson G, Astrand B. Physicians’ attitudes towards eprescribing: a comparative web survey in Austria and Sweden. Inform Prim Care 2009;17:241–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weingart SN, Simchowitz B, Shiman L, et al. Clinicians’ assessments of electronic medication safety alerts in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1627–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hellström L, Waern K, Montelius E, et al. Physicians’ attitudes towards ePrescribing—evaluation of a Swedish full-scale implementation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2009;9:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan WS, Phang JS, Tan LK. Evaluating user satisfaction with an electronic prescription system in a primary care group. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2009;38:494–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weingart SN, Massagli M, Cyrulik A, et al. Assessing the value of electronic prescribing in ambulatory care: a focus group study. Int J Med Inform 2009;78:571–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rupp MT, Warholak TL. Evaluation of e-prescribing in chain community pharmacy: best-practice recommendations. J Am Pharm Assoc 2008;48:364–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamblyn R, Huang A, Taylor L, et al. A randomized trial of the effectiveness of on-demand versus computer-triggered drug decision support in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008;15:430–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crosson JC, Isaacson N, Lancaster D, et al. Variation in electronic prescribing implementation among twelve ambulatory practices. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:364–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grossman JM, Gerland A, Reed MC, et al. Physicians’ experiences using commercial e-prescribing systems. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:w393–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schade CP, Sullivan FM, de Lusignan S, et al. e-Prescribing, efficiency, quality: lessons from the computerization of UK family practice. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:470–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamblyn R, Huang A, Kawasumi Y, et al. The development and evaluation of an integrated electronic prescribing and drug management system for primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:148–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pizzi LT, Suh DC, Barone J, et al. Factors related to physicians’ adoption of electronic prescribing: results from a national survey. Am J Med Qual 2005;20:22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devine EB, Hansen RN, Wilson-Norton JL, et al. The impact of computerized provider order entry on medication errors in a multispecialty group practice. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:78–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reckmann MH, Westbrook JI, Koh Y, et al. Does computerized provider order entry reduce prescribing errors for hospital inpatients? A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:613–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hug BL, Witkowski DJ, Sox CM, et al. Adverse drug event rates in six community hospitals and the potential impact of computerized physician order entry for prevention. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:31–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jung M, Hoerbst A, Hackl WO, et al. Attitude of physicians towards automatic alerting in computerized physician order entry systems. A comparative international survey. Methods Inf Med 2013;52:99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGinn C, Grenier S, Duplantie J, et al. Comparison of user groups’ perspectives of barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic health records: a systematic review. BMC Medicine 2011;9:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Azjen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Processes 1991;50:179–211 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:228–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bahaadinbeigy K, Yogesan K, Wootton R. MEDLINE versus EMBASE and CINAHL for telemedicine searches. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:916–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qi X, Yang M, Ren W, et al. Find duplicates among the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases in systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e71838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.