Abstract

Objective

To identify the genetic cause of chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome (CINCA syndrome) using whole-exome sequencing in a child who had typical clinical features but who was NLRP3 mutation negative based on conventional Sanger sequencing.

Methods

We performed whole-exome sequencing on DNA from peripheral blood, using Illumina TruSeq Exome capture and the HiSeq sequencing platform. Exome data were analyzed in the Galaxy Web-based suite. Whole-exome sequencing findings were confirmed by massively parallel sequencing.

Results

Analysis of variants in known autoinflammatory genes led to the identification of the pathogenic p.F556L NLRP3 missense mutation in 17.7% of Illumina reads (25 of 141). No new candidate genes were identified. Massively parallel sequencing of DNA from peripheral blood (performed in duplicate) unequivocally confirmed the presence of this mutation in 14.5% of alleles. Reexamination of the original Sanger chromatograms revealed a small peak at nucleotide position c.1698 corresponding to the mutated allele. This had initially been regarded as background noise, but in retrospect is completely consistent with somatic mosaicism for the p.F556L NLRP3 mutation in this child with CINCA syndrome.

Conclusion

This is the first description of somatic NLRP3 mosaicism detected using whole-exome sequencing in a “mutation-negative” patient with CINCA syndrome. Our findings suggest that whole-exome sequencing could be an important diagnostic tool for detecting somatic mosaicism, as well as for the discovery of novel causative gene mutations, in patients with clinical features of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes who are NLRP3 mutation negative by conventional sequencing. This approach could also be applicable to patients with other autosomal-dominant autoinflammatory diseases characterized by gain-of-function mutations who are mutation negative by conventional Sanger sequencing.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) comprise a spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases with 3 overlapping clinical entities of increasing disease severity: familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, and chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome (CINCA syndrome). CINCA syndrome represents the most severe form, with continuous inflammatory disease activity from birth associated with a generalized urticaria-like skin rash, dysmorphic features, deforming arthropathy, chronic aseptic meningitis, increased intracranial pressure, variable neurologic deficits, papilledema, sensorineural hearing loss, and poor growth (1).

The only genetic cause of CAPS that has been identified to date is the occurrence of heterozygous germline mutations in NLRP3. More than 80 different disease-causing mutations have been identified, mostly clustered in exon 3 but also found in exons 4 and 6, either arising de novo or transmitted in an autosomal-dominant manner (1,2). The NLRP3 variants detected in CAPS are gain-of-function mutations that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and provoke uncontrolled overproduction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β).

Up to 50% of patients with clinically diagnosed CINCA syndrome (with identical clinical features and response to anti–IL-1 treatment) show no NLRP3 mutation when tested using conventional Sanger DNA sequencing (2). While it is possible that such patients harbor mutations in as-yet-unidentified genes, recent studies suggest that somatic NLRP3 mosaicism may account for up to 70% of the cases of apparently “mutation-negative” CINCA syndrome (3). Since CAPS, and particularly CINCA syndrome, is a serious genetic illness requiring lifelong anti–IL-1 therapy with considerable cost implications, securing a molecular diagnosis remains an important issue for both affected families and their health care providers. Strategies have therefore been developed to reliably detect low-level somatic NLRP3 mosaicism in patients with clinical features of CAPS who are mutation negative by conventional genetic screening (4). In this study we hypothesized that whole-exome sequencing, an increasingly available and potentially important diagnostic genetic tool (5), might reveal somatic NLRP3 mosaicism and/or identify novel candidate genes in a pediatric CINCA syndrome patient who was NLRP3 mutation negative by standard genetic testing.

PATIENT AND METHODS

Case description

The patient, an 8-year-old boy who had typical clinical features of CINCA syndrome and had been found on earlier testing to be NLRP3 mutation negative, was referred for specialist consultation at the national CAPS clinical service at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. He was the first child of nonconsanguineous parents of Scottish ancestry. He was born prematurely at 27 weeks' gestation, requiring early ventilatory support. At birth he was noted to have frontal skull bossing and midfacial hypoplasia, and he developed an intermittent urticarial skin rash over his face and limbs. During his first year of life he was frequently hospitalized due to fever, urticarial skin rash (Figure 1A), and elevated acute-phase reactant levels, without an infectious cause. An extensive evaluation for primary immunodeficiency and autoimmunity yielded negative results; karyotype was normal (46XY). At age 18 months he was diagnosed as having CINCA syndrome based on the above-mentioned clinical features and the additional presence of synovitis of both knees with fixed flexion deformity and bony overgrowth of the left patella and tibia (Figure 1C). He had severe failure to thrive and motor developmental delay. Molecular genetic screening for NLRP3 mutations revealed the wild type for exons 3, 4, and 6.

Figure 1.

Clinical features of chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome in the patient. A, Persistent urticaria-like skin rash despite canakinumab treatment (4 mg/kg every 8 weeks). At the time this photograph was taken (when the patient was 7 years old), the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes Disease Activity Score (DAS) was 11 of 20, and the serum amyloid A (SAA) level was elevated at 154 mg/liter (normal <10). B, Improvement of the skin rash 8 weeks after the dosage of canakinumab was increased to 8 mg/kg every 8 weeks. At the time this photograph was taken, the DAS had declined to 1 of 20, but the SAA level was still elevated at 118 mg/liter. C, Patellar and tibial bony overgrowth, seen on a radiograph obtained when the patient was 7 years old.

Initial treatment with oral prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day) partially improved the rash and the patient's general well-being; anakinra (2 mg/kg/day) elicited a partial clinical response and modest steroid-sparing effect, but his clinical symptoms and serum amyloid A (SAA) levels were never well controlled. At age 5 years, he had an epileptic seizure. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed focal cortical dysplasia of the right middle frontal gyrus. Audiography revealed mild (30-db) conductive hearing loss, but no sensorineural loss. Regular and frequent screening had excluded inflammatory eye disease. Anakinra was switched to canakinumab (4 mg/kg subcutaneously every 8 weeks) when the patient was age 7 years, because of ongoing disease activity (CAPS disease activity score [DAS] [6] 11 of 20) and an SAA level of 154 mg/liter (normal <10) despite treatment with prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. Although there was an initial good clinical response to canakinumab at this starting dosage, the symptoms quickly returned. The dosage was therefore increased by 2 mg/kg every 8 weeks. The CAPS DAS remained unchanged until the canakinumab dosage reached 8 mg/kg every 8 weeks, at which point the DAS declined to 1 of 20 (with notable improvement of the skin rash, fevers, arthralgia, myalgia, headaches, and energy levels) (Figure 1B), and the prednisolone was tapered and then discontinued completely. The SAA level remained elevated (118 mg/liter) despite this marked clinical improvement, and increasing the frequency of canakinumab to once every 4 weeks is currently being considered.

Ethics compliance

This study had the full approval of the medical ethics committee of Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Fully informed written consent was obtained from the patient's parents in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Qiagen).

Whole-exome sequencing

Libraries were generated from DNA extracted from whole blood, using an Illumina TruSeq sample preparation kit. Whole exomes were captured using an Illumina TruSeq Exome enrichment kit and then sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq next-generation sequencer. Exome data were analyzed using the Galaxy Web-based suite (http://galaxyproject.org/) (7–9). The 100-bp paired-end reads were mapped to the reference human genome (hg_g1k_v37) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner alignment option for Illumina. Variant calling was performed using Genome Analysis ToolKit in Galaxy. We used wANNOVAR (10,11), a Web server package, to annotate all of the variants identified with Genome Analysis ToolKit. The annotated file was used to retrieve the reference single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) identifier numbers for variants from the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP), version 135 and the allele frequencies in 2 publicly available databases: the 1000 Genomes Project, containing genetic variations from 1,092 human genomes, and the Exome Sequencing Project (ESP 5400; https://esp.gs.washington.edu/drupal/), which has screened the exomes of >6,500 individuals.

Massively parallel sequencing of NLRP3

Massively parallel DNA sequencing of all exons of the NLRP3 gene was performed by amplification of 14 different specific pair primers, as previously described (4). All sequencing runs were performed on a GS Junior 454 Sequencer using GS Junior Titanium Sequencing kits (Roche). The sequences obtained were analyzed with Amplicon Variant Analyzer software (Roche).

Sanger sequencing

Exons 3, 4, and 6 of NLRP3/CIAS1 (NCBI RefSeqGene NC_000001.10) and exon 3 of NLRP12 (NCBI RefSeqGene NC_000019.9) were amplified using previously described primers and conditions (12). Negative and positive controls were included in each run. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) findings were validated by gel electrophoresis, and PCR products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit according to the protocol described by the manufacturer (Qiagen). Sequencing reaction was performed with a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Ready Reaction Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). The electrophoretic profiles of NLRP3 sequences were analyzed on an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer using Sequencing Analysis Software, version 5.4.

RESULTS

Findings of whole-exome sequencing

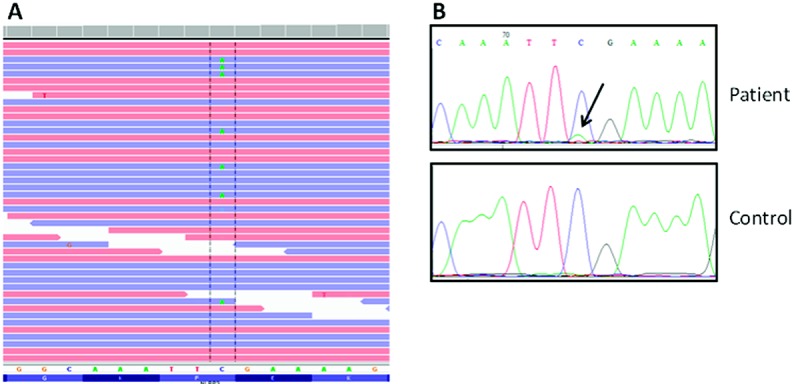

Whole-exome sequencing was performed on DNA extracted from whole blood to identify the genetic defect in this patient with CINCA syndrome. After synonymous variants were filtered out, there were 11,428 variants (including 239 variants not reported in the dbSNP135) to be examined for candidate mutations. We first examined variants in known autoinflammatory genes (IL10, IL10RA, IL10RB, IL1RN, IL36RN, LPIN2, MEFV, MVK, NLRP12, NLRP3, NLRP7, NOD2, PLCG2, PSMB8, PSTPIP1, SH3BP2, and TNFRSF1A), which resulted in the identification of 9 nonsynonymous variants in 6 different genes (Table1). Given the clinical presentation of the patient, the NLRP3 p.F566L mutation was the most plausible candidate variant because it was not present in general population databases (ESP, 1000G, or dbSNP), and it was previously reported as being the causative mutation in 2 unrelated patients with CINCA syndrome (2). The Integrative Genomics Viewer of the alignment file revealed the presence of this mutation in 25 of 141 Illumina reads mapping to this region (17.7%) (Figure 2A). No new candidate genes were identified, and there was no evidence of mosaicism in any of the above-mentioned known autoinflammatory genes. No other tissue (other than blood) was available for this study.

Table 1.

Identified variants in genes associated with monogenic autoinflammatory diseases, and known frequencies in the general healthy population*

| Gene | Sequence variant | Protein variant | ESP6500 | 1000g2012feb | 1000G European population | dbSNP135 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL10RA | 1051A>G | R351G | 0.728 | 0.81 | 0.68 | rs2229113 |

| MEFV | 1306G>A | G436R | 0.424 | 0.38 | 0.44 | rs1231122 |

| MEFV | 1272T>A | D424E | 0.406 | 0.66 | 0.56 | rs1231123 |

| MVK | 155G>A | S52N | 0.116 | 0.09 | 0.15 | rs7957619 |

| NLRP3 | 1698C>A | F566L | – | – | – | – |

| NLRP3 | 2107C>A | Q703K | 0.035 | 0.02 | 0.04 | rs35829419 |

| NOD2 | 802C>T | P268S | 0.198 | 0.12 | 0.24 | rs2066842 |

| NOD2 | 2863G>A | V955I | 0.069 | 0.05 | 0.10 | rs5743291 |

| SH3BP2 | 464C>T | A155V | 0.006 | 0.01 | 0.02 | rs35313240 |

EPS6500 = the Exome Sequencing Project; 1000g2012feb = February 2012 version of the 1000 Genomes Project (1000G); dbSNP135 = Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database, version 135.

Figure 2.

A, Illumina data from the mapped reads as visualized in Integrative Genomics Viewer, providing evidence of the presence of c.1698C>A transversion. B, Sanger chromatograms showing the subtle peak for the mutated A allele at the c.1698 position in the patient sample (arrow), but absent in a healthy control sample.

Findings of massively parallel sequencing

Massively parallel DNA sequencing confirmed the C-to-A transversion at the c.1698 position of the NLRP3 gene (GenBank RefSeq NM_001243133.1) resulting in p.F566L mutation in the patient, with a mean allelic frequency of the mutated allele in peripheral blood of 14.5% (mean coverage 1,151×; analyses performed in duplicate).

Findings of Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing of NLRP3 and NLRP12 genes had been previously performed as part of routine clinical care of the patient, and no pathogenic variants were identified in the analyzed exons, although the nonpathogenic variant NLRP3 Q703K was detected. There was a very small peak corresponding to the alternate allele at the c.1698 position of the NLRP3 gene (Figure 2B), which was associated with a decrease of the signal intensity of the wild-type allele. The small peak was previously considered background noise, but in retrospect it was compatible with somatic mosaicism for the p.F566L mutation.

DISCUSSION

A puzzling aspect of CINCA syndrome is that up to 50% of patients may have a typical clinical phenotype, including response to IL-1 blockade treatment, but with no detectable NLRP3 mutation demonstrated by Sanger sequencing, which is currently the mainstay of routine genetic diagnostic testing. The “mutation-negative” finding in 10–69% of these CINCA syndrome patients may be accounted for by somatic NLRP3 mosaicism, with markedly variable reported frequencies of the mutated allele, ranging from 4.2% to 35.8% (3). The remaining patients may harbor mutations in novel gene(s). Whole-exome sequencing is a powerful new genetic technique that was previously used for gene discovery in novel Mendelian diseases and is being increasingly recognized as a potent diagnostic tool (5), including for the detection of somatic gene mutations (13–15). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of somatic NLRP3 mosaicism detected by whole-exome sequencing in a CINCA syndrome patient who had been found to be mutation negative with other techniques.

The p.F566L mutation detected using whole-exome sequencing in our patient was subsequently confirmed by massively parallel DNA sequencing, a technique that has been previously validated for the detection of somatic mosaicism in CAPS and is regarded by many as a gold standard (2). Although many patients with somatic NLRP3 mutations may have milder clinical phenotypes or later-onset disease (2,3), the clinical severity of our patient's phenotype is consistent with the known severe clinical impact of the p.F566L mutation. Somatic NLRP3 mosaicism for the p.F566L mutation has been previously reported in 2 unrelated patients with CINCA syndrome, with estimated allelic mosaicism of 11.5% and 14.6%, respectively (3). The pathologic effects of this mutation have been demonstrated through induction of necrosis-like programmed cell death in the human monocytic line THP-1 and ASC-dependent NF-κB activation (3). Those studies combined with the increasing number of clinical reports confirm that somatic mosaicism for the p.F566L mutation can result in the most severe CAPS phenotype, the CINCA syndrome.

When considering the most practical methodologies for screening for somatic mosaicism in CAPS in the routine clinical setting, factors such as sensitivity, reliability, and expense come into play. Customized techniques such as massively parallel DNA sequencing undoubtedly have the advantage of high sensitivity (2) but are laborious and costly, currently target only NLRP3, and are not widely available in nonspecialized laboratories. Whole-exome sequencing is increasingly being utilized in a diagnostic capacity at relatively low cost (5), and we propose that it could be a valid alternative. Our approach of using whole-exome sequencing to rapidly screen several known autoinflammatory genes is one that has been used successfully in other clinical settings. This strategy is particularly useful when mutations on several different genes can be associated with similar clinical phenotypes, as occurs in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and the various syndromes of defective glycoprotein synthesis. In these cases, conventional DNA sequencing of tens of genes becomes impractical as it is expensive and time-consuming (5). Furthermore, in contrast to novel gene discovery, use of whole-exome sequencing to detect known pathogenic mutations does not require overly specialized data analyses or further in vitro experimental procedures to confirm their pathogenicity.

The depth of coverage by whole-exome sequencing may not be enough to detect somatic mosaicism of <10%, so a negative test result does not completely rule out NLRP3 somatic mosaicism in CAPS patients. In retrospect, the small peak observed on the chromatogram obtained from Sanger sequencing associated with the decrease of signal intensity of the wild-type allele suggested the presence of this particular mutation in our patient. However, the intensity of the small peak corresponding to the NLRP3 mutated allele was extremely low, falling within the baseline noise level, and was the main reason for the false-negative call in the original screen. Thus, whole-exome sequencing offers at least 3 powerful diagnostic advantages over other sequencing methods in this context: 1) superior sensitivity over Sanger sequencing for the detection of somatic gene mosaicism, 2) rapid screening for other genes responsible for different monogenic autoinflammatory diseases with overlapping clinical phenotypes, and 3) the potential to identify novel causal genes for CAPS-like phenotypes, since genetic heterogeneity is highly likely in CAPS.

In conclusion, we describe for the first time the diagnostic use of whole-exome sequencing for the detection of somatic NLRP3 mosaicism in a patient with CINCA syndrome. This observation highlights the diagnostic utility of whole-exome sequencing in patients with CAPS. Securing a molecular diagnosis provides justification for use of the clinically effective but expensive lifelong therapies required to treat this condition.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Omoyinmi had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Omoyinmi, Melo Gomes, Standing, Klein, Hawkins, Brogan.

Acquisition of data. Omoyinmi, Melo Gomes, Standing, Rowczenio, Eleftheriou, Aróstegui, Lachmann, Brogan.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Omoyinmi, Melo Gomes, Standing, Rowczenio, Eleftheriou, Klein, Aróstegui, Brogan.

References

- 1.Aksentijevich I, Putnam CD, Remmers EF, Mueller JL, Le J, Kolodner RD, et al. The clinical continuum of cryopyrinopathies: novel CIAS1 mutations in North American patients and a new cryopyrin model. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1273–85. doi: 10.1002/art.22491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arostegui JI, Lopez Saldana MD, Pascal M, Clemente D, Aymerich M, Balaguer F, et al. A somatic NLRP3 mutation as a cause of a sporadic case of chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome/neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease: novel evidence of the role of low-level mosaicism as the pathophysiologic mechanism underlying Mendelian inherited diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1158–66. doi: 10.1002/art.27342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka N, Izawa K, Saito MK, Sakuma M, Oshima K, Ohara O, et al. High incidence of NLRP3 somatic mosaicism in patients with chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome: results of an international multicenter collaborative study. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3625–32. doi: 10.1002/art.30512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izawa K, Hijikata A, Tanaka N, Kawai T, Saito MK, Goldbach-Mansky R, et al. Detection of base substitution-type somatic mosaicism of the NLRP3 gene with >99.9% statistical confidence by massively parallel sequencing. DNA Res. 2012;19:143–52. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ku CS, Cooper DN, Polychronakos C, Naidoo N, Wu M, Soong R. Exome sequencing: dual role as a discovery and diagnostic tool. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:5–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.22647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kummerle-Deschner JB, Tyrrell PN, Reese F, Kotter I, Lohse P, Girschick H, et al. Risk factors for severe Muckle-Wells syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3783–91. doi: 10.1002/art.27696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blankenberg D, von Kuster G, Coraor N, Ananda G, Lazarus R, Mangan M, et al. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2010;19:19.10.1–21. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1910s89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giardine B, Riemer C, Hardison RC, Burhans R, Elnitski L, Shah P, et al. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 2005;15:1451–5. doi: 10.1101/gr.4086505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang X, Wang K. wANNOVAR: annotating genetic variants for personal genomes via the web. J Med Genet. 2012;49:433–6. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:301–5. doi: 10.1038/ng756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Huynh M, Silhavy JL, Kim S, Dixon-Salazar T, Heiberg A, et al. De novo somatic mutations in components of the PI3K-AKT3-mTOR pathway cause hemimegalencephaly. Nat Genet. 2012;44:941–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pagnamenta AT, Lise S, Harrison V, Stewart H, Jayawant S, Quaghebeur G, et al. Exome sequencing can detect pathogenic mosaic mutations present at low allele frequencies. J Hum Genet. 2012;57:70–2. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vissers LE, Fano V, Martinelli D, Campos-Xavier B, Barbuti D, Cho TJ, et al. Whole-exome sequencing detects somatic mutations of IDH1 in metaphyseal chondromatosis with D-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (MC-HGA) Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:2609–16. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]