Abstract

The neuropeptide galanin has not been localized previously in the primate uvea, and the neuropeptide somatostatin has not been localized in the uvea of any mammal. Here, the distribution of galanin-like and somatostatin-like immunoreactive axons in the iris, ciliary body and choroid of macaques and baboons using double and triple immunofluorescence labeling techniques and confocal microscopy was reported. In the ciliary body, galanin-like immunoreactive axons innervated blood vessels and the ciliary processes, particularly at their bases. In the iris, the majority of these axons was associated with the loose connective tissue in the stroma. Somatostatin-like immunoreactive axons were found in many of the same areas of the uvea supplied by cholinergic nerves. In the ciliary body, there were labelled axons within the ciliary processes and ciliary muscle. They were also found alongside blood vessels in the ciliary stroma. In the iris, somatostatin-like immunoreactive axons were abundant in the sphincter muscle and less so in the dilator muscle. A unilateral sympathectomy had no effect on the distribution of somatostatin-like or galanin-like immunoreactive axons, and these axons did not contain the sympathetic marker tyrosine hydroxylase. They did not contain the parasympathetic marker choline acetyltransferase, either. The galanin-like immunoreactive axons contained other neuropeptides found in sensory nerves, including calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P and cholecystokinin. Somatostatin-like immunoreactive axons did not contain any of these sensory neuropeptides or galanin-like immunoreactivity, and they were neither labelled with an antibody to 200 kDa neurofilament protein, nor did they bind isolectin-IB4. Nevertheless, they are likely to be of sensory origin because somatostatin-like immunoreactive perikarya have previously been localized in the trigeminal ganglion of primates. Taken together, these findings indicate galanin and somatostatin are present in two different subsets of sensory axons in primate uvea.

Keywords: neuropeptide, iris, ciliary body, choroids, sensory, primate, monkey, confocal microscopy, adrenergic, cholinergic, cholecystokinin, substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide

1. Introduction

The neuropeptide galanin has been localized to axons in the uvea of three species of mammals, but there are species differences in the origins of these axons. In cats, sensory, parasympathetic and sympathetic axons contain galanin-like immunoreactivity (Grimes et al, 1994). In the uvea of rats and pigs, galanin-like immunoreactivity has been localized only to sensory axons (Stromberg et al., 1987; Stone et al., 1988). Somatostatin has not been localized in the uvea of any mammal, but there is good evidence for its presence in nerves there. The peptide has been detected in extracts of iris/ciliary body and choroid of cows, sheep, rabbit and rats using a radio-immunoassay (Elbadri et al., 1991). The results in other mammals suggest that somatostatin may be of sensory or sympathetic origin. In rats, some of the somatostatin-like immunoreactive (−IR) neurons in the superior cervical ganglion project to the eye (Luebke and Wright, 1992). Somatostatin has also been localized to cell bodies in the trigeminal ganglion in rats (Ositelu et al., 1987; Alvarez and Priestley, 1990; Ambalavanar and Morris, 1992), guinea pigs (Kummer and Heym, 1986), cats (Lazarov, 1994) and humans (Del Fiacco and Quartu, 1994). Some somatostatin-IR axons in the cat ciliary ganglion do not contact the ganglion cells and may, therefore, be of sensory or sympathetic origin (Kondo et al., 1982; Grimes et al., 1990).

Because of these species differences in the distribution of somatostatin-IR and galanin-IR axons in the uvea of various mammals, studies of nonhuman primates are essential to predict the distribution of these types of axons in human eyes. To determine whether these peptides are present in uveal nerves of primates, macaques and baboons were studied using immunofluorescence labeling. To identify the origins of these axons, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody was used to label sympathetic and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) antibody was used to label parasympathetic axons. Because either peptide might be localized to sympathetic axons, eyes from one macaque after a unilateral sympathectomy were also examined. There is no single marker of all sensory axons. Therefore, several markers of sensory axons were used, including: substance P (Miller et al., 1981; Stone et al, 1982), calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP, Terenghi et al., 1985; Matsuyama et al., 1986), cholecystokinin (CCK, Kuwayama and Stone, 1986), isolectin-IB4 from Griffonia simplicifolia (Ambalavanar and Morris, 1992) and the 200 kDa neurofilament protein (Bergman et al., 1999).

2. Materials and Methods

Animals and Tissue Fixation

Macaque eyes (Macaca mulatta, from eight animals) were obtained from Covance Research Products (Alice, TX, U.S.A.) or from Dr J. Bachevalier (University of Texas-Houston Medical School), and baboon eyes (Papio anubis, from five animals) were obtained from Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research (San Antonio, TX, U.S.A.). One macaque (Macaca fascicu-laris) was killed following an overdose of pentobarbital 4 years after a unilateral superior cervical gang-lionectomy (Robinson and Kaufman, 1992). The sympathetic denervation remained clinically, as the sympathectomized pupil showed supersensitivity to topical phenylephrine. Each eye was hemisected and the anterior segment was immersion fixed in 2–4% paraformaldehyde with 0–1% picric acid in 0–1 m phosphate buffer overnight at 4°C (pH 7·4). The macaque and baboon tissue used for labeling with the gastrin-CCK (gCCK) antibody, was fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0–1 m phosphate buffer for 1 hr.

Tissue Processing

The tissue was rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7·4), and then the choroid was dissected free from the sclera and processed as a whole mount. The picric acid fixed tissue was then treated with 1 % sodium borohydride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) in PBS for an hour and again rinsed in PBS for several hours. The choroid was bleached using several changes of 2 % hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 1–2 weeks prior to the immunolabelling. All other tissues were cryoprotected in 10 % sucrose in PBS for 1–4 hr, followed by 30% sucrose in PBS for at least 12 hr. This tissue was frozen in Tissue-Tek and cryostat sections (32 µm) of the anterior segment were cut in a meridional orientation, thaw mounted onto gelatin-coated slides and dried for at least 2 hr at 4°C.

Immunolabelling

For lectin-binding studies, sections were pre-incu-bated overnight with G simplicifolia isolectin-1B4 (10 µg ml−1, L-1104, Vector Laboratories, Burlin-game, CA, U.S.A.) at 4°C prior to the immuno-fluorescence procedures. This lectin binds the galactosyl end groups on a subset of sensory axons (Silverman and Kruger, 1990).

Sections were preincubated in 1–2 % normal donkey serum with 0·3% Triton X-100 for 1 hr at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibody for 12–48 hr at 4°C. Primary antibodies included: rabbit anti-porcine galanin 1:2000 (IHC7153, Peninsula Laboratories, Belmont, CA, U.S.A.), rabbit anti-somatostatin 281–12 1:1000 (S298, donated by Dr R. Benoit, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), anti-somato-statin 281–12 1:200 raised in goat against synthetic peptide (Peninsula, Belmont, CA, U.S.A.) conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Carbiochem, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) using glutaraldehyde, monoclonal mouse and rabbit anti-rat αCGRP 1:1000 (MAB317 or AB1971, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, U.S.A.), monoclonal mouse anti-rat TH 1:10 000 (clone TH16, T2928, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), monoclonal mouse anti-200 kDa neurofilament protein 1:500 (clone RT97, Boeringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.), mouse monoclonal anti-human gCCK (9303, donated by H. Wong, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, U.S.A.), rat monoclonal anti-substance P 1:200 (MAS035, Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY, U.S.A.), affinity purified goat anti-ChAT 1:200 (AB144, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, U.S.A.) and affinity purified goat anti-G. simplicifolia α-lectin 1:500 (AS2104, Vector, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.). Following several rinses with PBS, the sections were incubated in the affinity purified biotinylated donkey secondary antibody (1:100, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Westgrove, PA, U.S.A.) in PBS for 1–2 hr at room temperature. This secondary antibody was then labelled with 1:100 indocarbocyanine (Cy-3)-streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Westgrove, PA, U.S.A.) or 1:2000 Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) in PBS after an incubation of 1 hr at room temperature. For double labeling, the second primary antibodies (raised in different species) were incubated as before. This antibody was then labelled directly with the affinity purified secondary antibody conjugated to indodicarbocyanine (Cy-5, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Westgrove, PA, U.S.A.) for 1 hr at room temperature. The sections were then rinsed in PBS and mounted in 3:1 glycerol to PBS with 0–1% sodium azide and 0–1% n-propyl gallate or Vector Shield (Vector, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.). For choroid whole mounts, a similar procedure was used. However, incubation periods were longer; the tissue was incubated in primary antibody for 5–8 days and incubated in the secondary antibodies overnight.

No labelling of the tissue was seen when the primary antibodies were omitted. Controls also included a preincubation for at least 2 hr with synthetic peptides. The galanin antibody was incubated with porcine galanin (0·1–1 µm, 7153, Peninsula, Belmont, CA, U.S.A.), the somatostatin antibody was incubated with somatostatin 28 (either 1–12 or 1–14 at 10 µm, Peninsula, Belmont, CA, U.S.A.) and the gCCK antibody was incubated with CCK-8 (nonsul-fated 26–33, 10 µm, H-2085, Bachem, Torrance, CA, U.S.A.). The labelling of the uveal axons by each antibody was blocked by the peptide against which it was raised. The galanin peptide did not block labelling with antibodies to gCCK or substance P, and the gastrin-CCK peptide did not block labelling with antibodies to galanin or substance P.

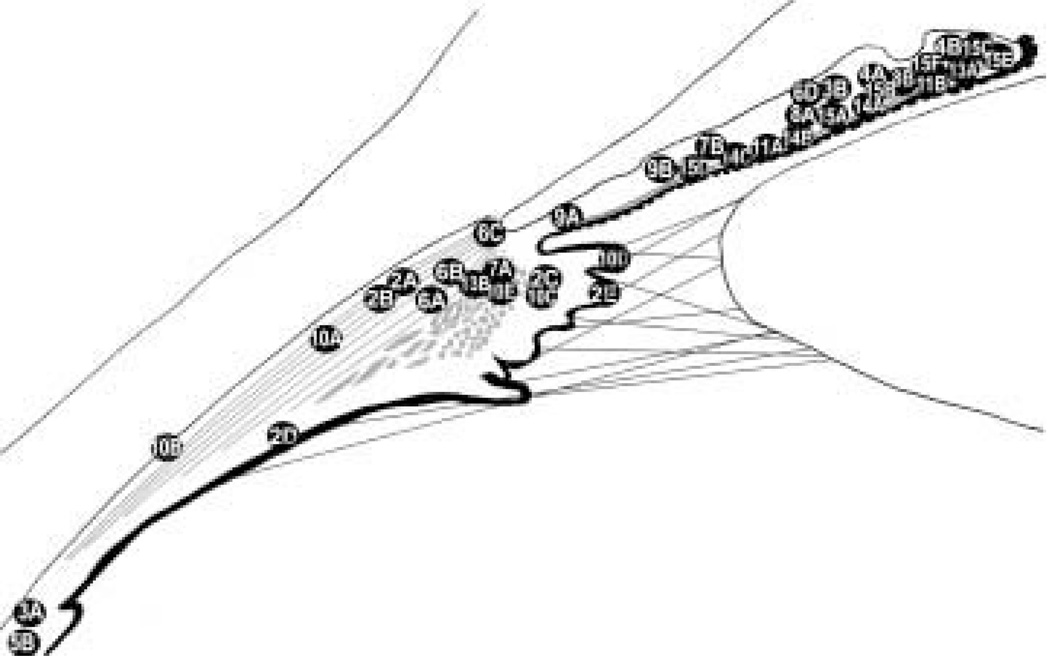

Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM410, Thornwood, NY, U.S.A.) with a krypton-argon laser using an oil immersion lens (× 63, numerical aperture 1·4 unless otherwise stated in the figure caption). Excitation was at 568 nm for Cy-3, 647 nm for Cy-5, and 488 nm for FITC or Alexa 488 with emission filters of 590–610, 670–810 and 515–540 nm, respectively. For double-or triple-labelled tissue, single optical sections (0·5 µm) were analyzed. However, stacks (10–15 × 0·5 µm) are shown where superposition does not create ambiguity. A diagram of the anterior segment has been included to show the approximate locations of the areas selected for the illustrations (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

A schematic representation of the anterior segment in meridional section shows the approximate locations of the other figures.

3. Results

There were no apparent differences in the distributions of galanin-IR and somatostatin-IR axons in the uvea of macaques and baboons. Therefore, the results from both species are considered together. No labelled perikarya were detected in the uvea.

Distribution of Galanin-IR Axons

Sparse, varicose galanin-IR axons were found throughout the ciliary body (Fig. 2). Between the bundles of meridional fibres, galanin-IR axons ran parallel with the muscle fibres. Galanin-IR axons were also seen among the radial and circular muscle fibres. Large blood vessels were surrounded by galanin-IR axons, and based on their positions, these blood vessels are likely to be part of the major arterial circle. The bases of the ciliary processes contained galanin-IR axons. Small varicose axons were also seen within the ciliary processes near blood vessels and in the stroma beneath the ciliary pigmented epithelium. Galanin-IR axons were also present in large nerve bundles of 50–100 µm in diameter found within the choroid (Fig. 3(A)) and ciliary body. These nerves ran within the pars plana near the border with the sclera and almost parallel to it. Then, within the pars plicata, these ciliary nerves turned towards the root of the iris.

FIG. 2.

Sparse galanin-IR axons were detected throughout the ciliary body. (A) Galanin-IR axon is running in the stroma between meridional muscle bundles in the pars plicata region (arrowhead). Axons are also seen within a large ciliary nerve (arrow). (B) At a higher magnification, a galanin-IR axon is seen among the meridional fibres in the pars plana region. (C) Denser galanin-IR axons are seen at the bases of the ciliary processes. At the arrow, there is a labelled axon within a ciliary process. (D) A labelled axon is seen in the vicinity of the epithelial layers of the ciliary body. (E) At a higher magnification, galanin-IR axons are seen in the stroma of a ciliary process. Scale bar is 100 µm in (A) and (C) (×40 oil immersion lens, numerical aperture 1·3) and 10 µm in (B), (D) and (E).

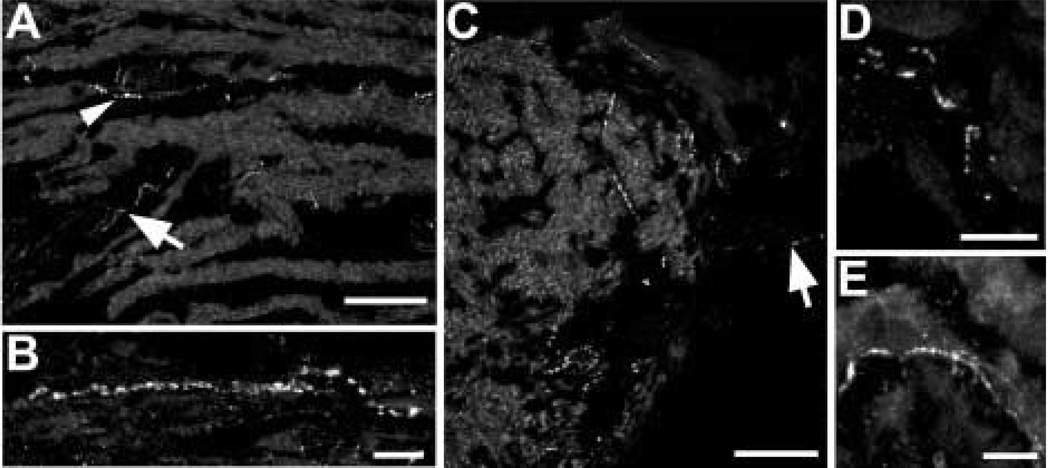

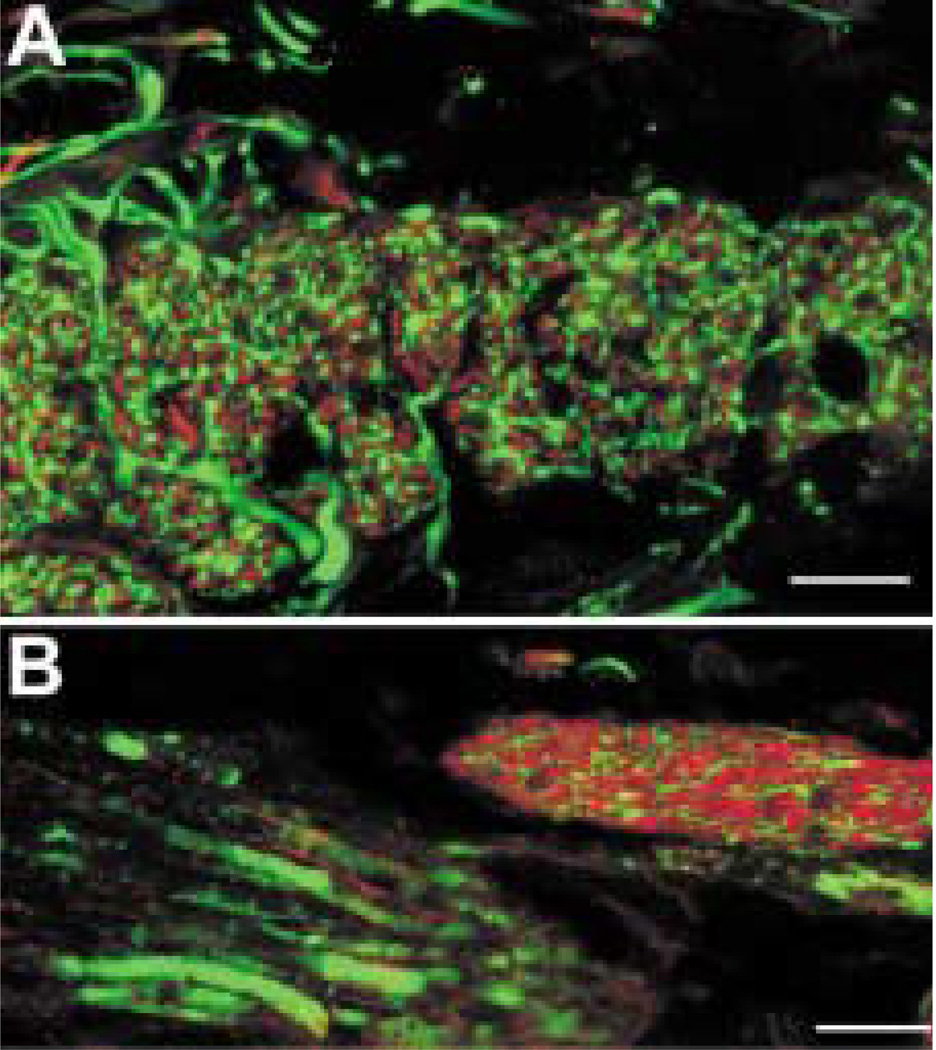

FIG. 3.

(A) Several galanin-IR (GAL, red) axons are seen within a ciliary nerve running in the choroid close to the ora serrata. Many axons within this nerve contain calcitonin gene-related peptide-like immunoreactivity (CGRP, green) including the galanin-IR axons (arrows). Scale bar = 25 µm. (B) At higher magnification, the GAL-IR (red) axons are shown running with the loose connective tissue of the iris stroma. These galanin-IR axons (arrows) contain CGRP-like immunoreactivity (green). The two channels are combined on the right. Scale bar =10 µm.

Galanin-IR axons were seen throughout the stroma of the iris, and they often ran parallel with the numerous loose connective tissue fibres (Fig. 4). Galanin-IR axons were not generally observed near the dilator muscle. Single axons were only rarely found near the sphincter muscle. No galanin-IR axons were seen in the trabecular meshwork after an extensive search. However, on a single section, a galanin-IR axon was detected in the sclera anterior to the trabecular meshwork, at the anterior border of Schlemm's canal. Galanin-IR axons were also observed in flat mounts of the choroid (Fig. 5 (A)) and only rarely in vertical sections (Fig. 5(B)). These axons were seen within the ciliary nerves running through the choroid, and short lengths of mostly unbranched axons were also seen in the choroidal stroma near melanocytes.

FIG. 4.

(A) The pupillary margin of the iris is shown at a low magnification. Most of the galanin-IR axons are seen in the stroma of the iris (arrowheads); axons are only occasionally labelled within the iris sphincter muscle (arrow). Scale bar = 100 µm (×40 oil immersion lens, numerical aperture 1·3). (B) At a higher magnification, galanin-IR axons are shown anterior to the iris sphincter muscle. Scale bar = 25 µm.

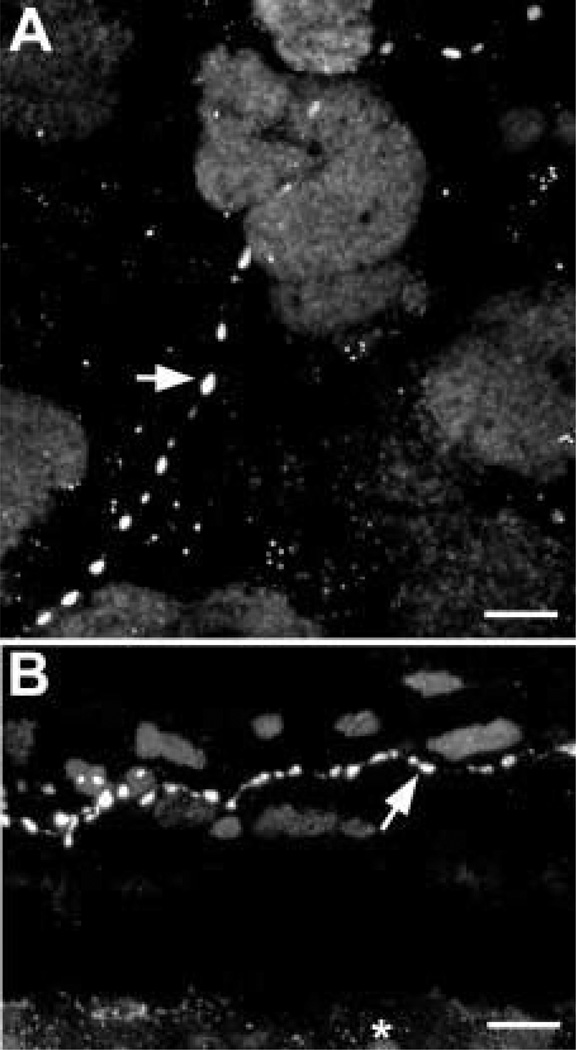

FIG. 5.

In the choroid, galanin-IR axons have relatively large varicosities of approximately 1–2 µm in diameter (arrows). (A) The galanin-IR axons were best seen in the choroid fiat mounts. (B) Galanin-IR axons were only rarely seen in vertical sections of the choroid such as this one. This axon runs through the middle of the choroid between many melanocytes in the anterior half of the eye. The retinal pigment epithelium is indicated with an asterisk. Scale bar =10 µm.

The Origin of the Galanin-IR Axons

After a unilateral superior cervical ganglionectomy, the TH-like immunoreactivity in the ipsilateral ciliary body and iris was markedly reduced (Fig. 6(B)) compared to the contralateral control eye (Fig. 6(A)). In the control ciliary body, long, varicose TH-IR axons were common among the meridional fibers, and these were greatly reduced in the sympathectomized eye. However, some varicose TH-IR axons remained in the iris of the sympathectomized eye. In contrast, the distribution and density of the galanin-IR axons were not altered by sympathectomy. In addition, these galanin-IR axons did not contain TH-like immunoreactivity. Taken together, these findings suggest that the galanin-IR axons are not sympathetic in origin.

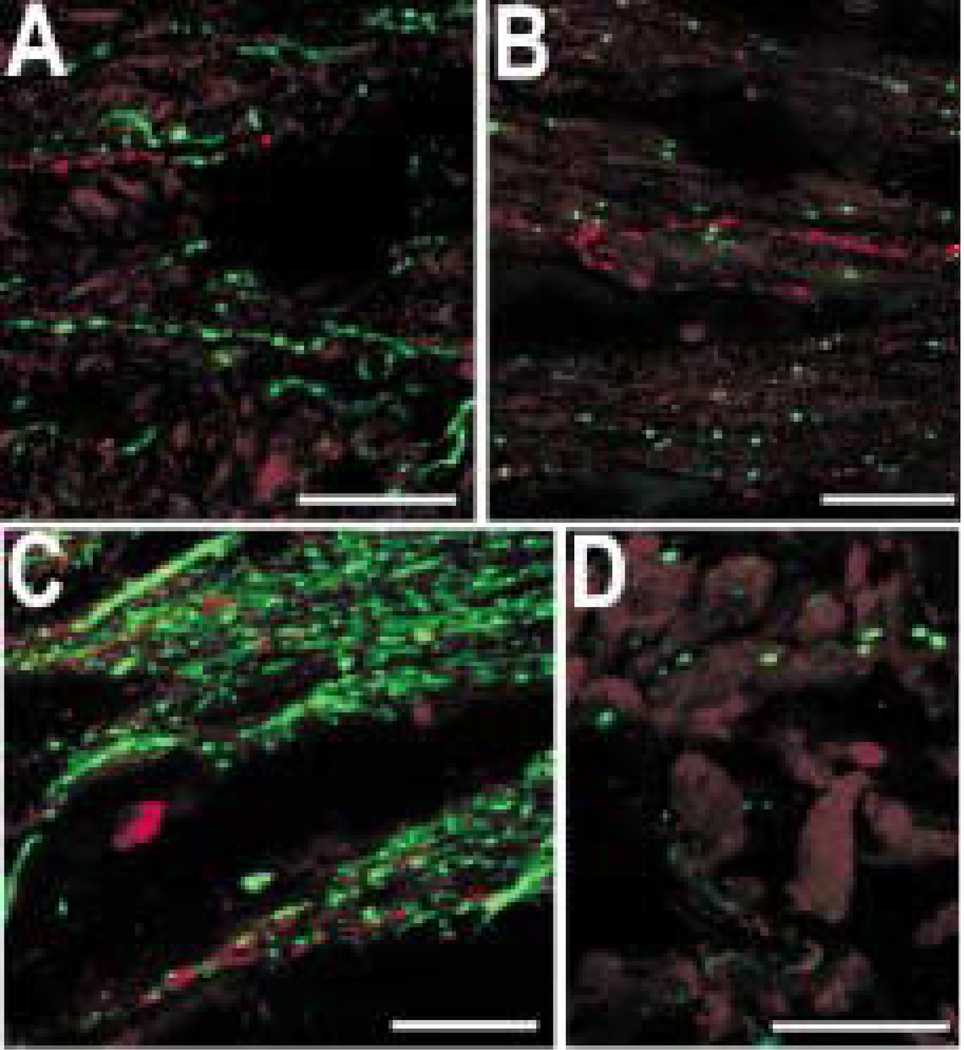

FIG. 6.

Galanin-IR (red) axons do not contain TH-like immunoreactivity (green) in either the ipsilateral control eye (A) or the sympathectomized eye (B). TH-like immunoreactivity was greatly reduced in the sympathectomized eye, and the galanin-like immunoreactivity remained unchanged. In addition, galanin-IR axons (red) did not contain ChAT-like immunoreactivity (green), which is shown in the ciliary body at the origin of the meridional fibres (C) and in the iris (D). Scale bar = 25 µm.

Galanin-IR axons were only occasionally observed in the vicinity of the sphincter and dilator muscle fibres of the iris. In the ciliary body, galanin-IR axons were sometimes detected in the same bundles of muscle fibres as cholinergic axons. However, the galanin-IR axons did not contain ChAT-like immunoreactivity in either ciliary body (Fig. 6(C)) or the iris (Fig. 6(D)). This finding suggests galanin-IR axons are not parasympathetic in origin.

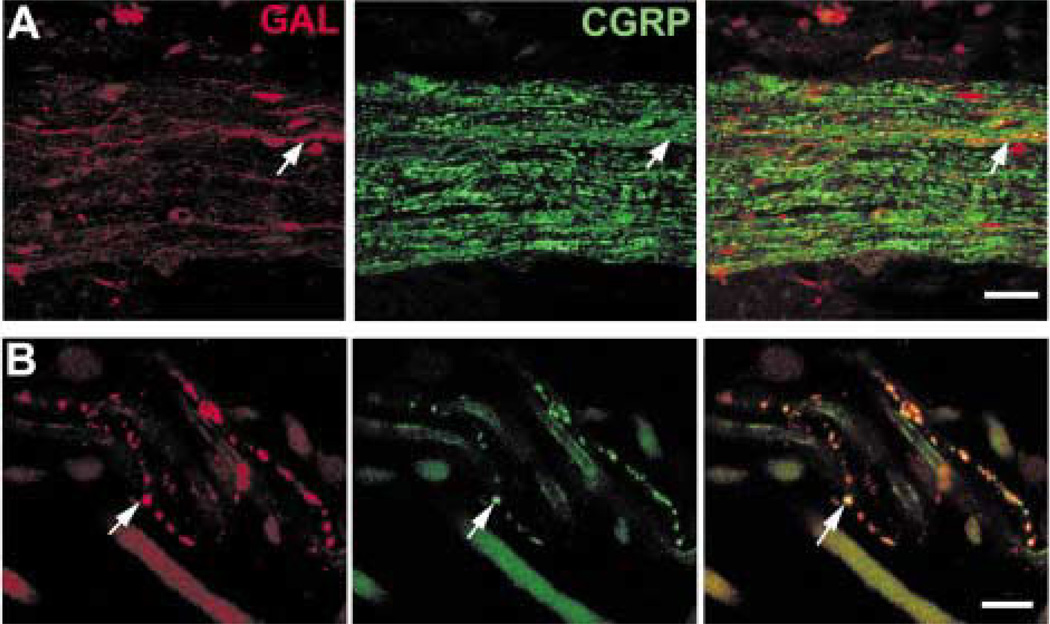

The nerves running through the choroid and ciliary body included many CGRP-IR axons (Fig. 3(A)). Some of these axons were faintly labelled, and others were more intensely labelled. A subpopulation of the faintly labelled CGRP-IR axons also contained galanin-like immunoreactivity (Fig. 3(A) and (B)). Substance P-like immunoreactivity was also seen in a subpopulation of CGRP-IR axons (results not shown). Virtually all the galanin-IR axons contained substance P-like immunoreactivity in both ciliary body (Fig. 7(A)) and iris (Fig. 7(B)). There were, however, many substance P-IR axons that did not contain galanin-like immunoreactivity.

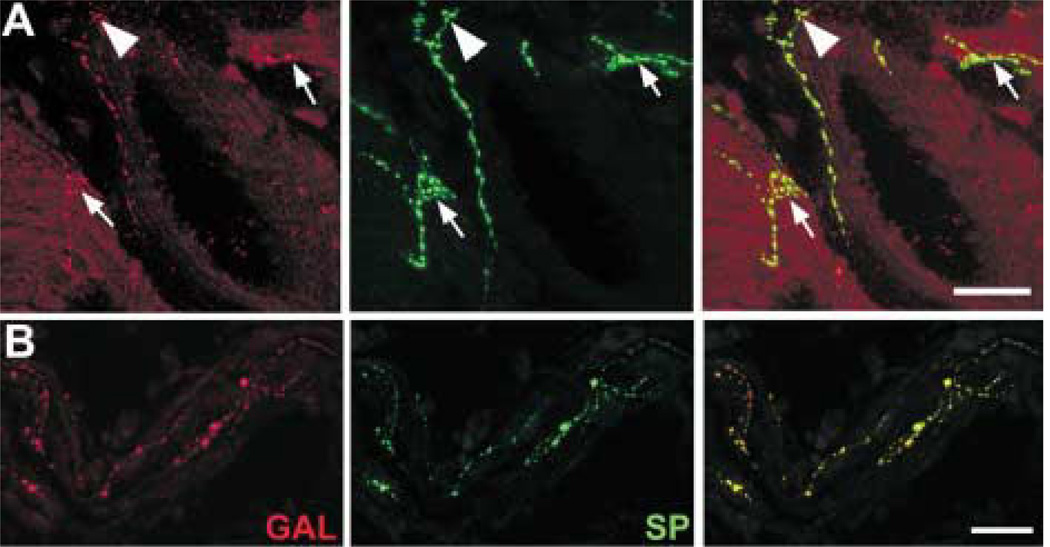

FIG. 7.

Galanin-IR (red) axons contain substance P-like (green) immunoreactivity. The two channels are combined on the right. (A) The galanin-IR axons contact an arterial circle blood vessel (arrowhead) and also contact ciliary muscles (arrows). (B) Galanin-IR axons run with the loose connective tissue in the stroma of the iris. Scale bar = 25 µm.

Colocalization of Gastrin-Cholecystokinin-like Immunoreactivity in a Subset of Galanin-IR Axons

Varicose gCCK-IR axons were commonly found running alongside small blood vessels and loose connective tissue in the stroma of the iris (Fig. 8). Axons were less frequently seen near the dilator and sphincter muscles. Occasionally, gCCK-IR axons were detected in nerves within the ciliary body and, very rarely, within the ciliary processes. In the iris, galanin and gCCK-IR axons were distributed similarly. Therefore, it was not surprising that many gCCK-IR axons in the iris contained galanin-like immunoreactivity (Fig. 9(A)). There were galanin-IR axons that did not contain gCCK-like immunoreactivity. Most of the gCCK-IR axons also contained substance P-like immunoreactivity. A triple-label experiment demonstrated that a subpopulation of the galanin-IR axons in the iris contained both gCCK-like and substance P-like immunoreactivity (Fig. 9(B)).

FIG. 8.

Gastrin-CCK-IR axons run alongside the blood vessels (arrow) and loose connective tissue in the iris stroma in the ciliary zone (A) and in the pupillary zone (B). Most gCCK-IR axons are found anterior to the sphincter muscle (SM), but gCCK-IR axons are also seen within the muscle. Scale bar = 25 µm.

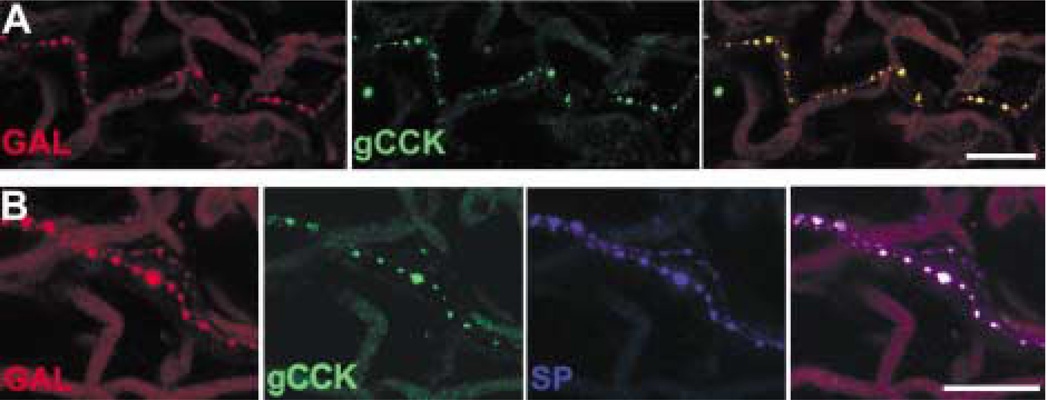

FIG. 9.

(A) A galanin-IR (red) axon near the iris root also contains gCCK-like immunoreactivity (green). The two channels are combined on the right. (B) A galanin-IR axon (red) within the iris stroma contains both gCCK-like (green) and substance P-like immunoreactivity (blue). All three channels are combined on the right. Scale bar = 25 µm.

Distribution of Somatostatin-IR Axons

In the ciliary body, the majority of the somato-statin-IR axons was associated with a subset of muscle bundles. This was most clearly seen in the meridional fibres of the ciliary body (Fig. 10(A)). Some labelled axons also contacted large blood vessels in the major arterial circle (Fig. 10(E)). There was a high density of somatostatin-IR axons at the bases of the ciliary processes (Fig. 10(C)), and varicose somatostatin-IR axons were seen in the centers of the ciliary processes (Fig. 10(D)). Labelled axons were also common at the root of the iris, extending towards the scleral spur. Single somatostatin-IR axons were regularly observed within the supraciliary layer, between the ciliary body and sclera (Fig. 10(B)).

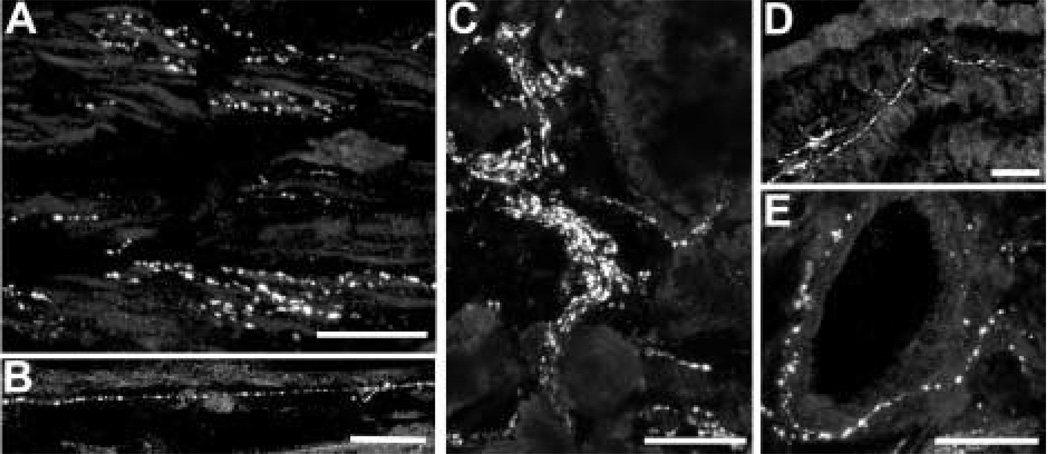

FIG. 10.

Somatostatin-IR axons are abundant and widely distributed in the ciliary body. (A) A subset of meridional muscle bundles contains numerous somatostatin-IR axons. (B) This small, varicose axon runs along the border between the sclera (above) and the meridional muscle (below). (C) There are numerous somatostatin-IR axons at the bases of the ciliary processes. (D) They are also found in the centers of ciliary processes. (E) Somatostatin-IR axons also contact the large blood vessels in the arterial circle. Scale bar = 25 µm.

The iris was densely innervated with somatostatin-IR axons, and most of the somatostatin-IR axons were associated with muscle fibres. Somatostatin-IR axons were numerous within the pupillary sphincter muscle (Fig. 11 (A)) and less common around the pupillary dilator muscle (Fig. 11(B)). Somatostatin-IR axons were occasionally seen in the anterior stroma of the iris. Somatostatin-IR axons that branched in the inner half of the choroidal stroma were also observed in flat mounts of the choroid (Fig. 12).

FIG. 11.

Somatostatin-IR axons are occasionally detected in the stroma of the iris (arrowhead). The somatostatin-IR axons are most numerous in the vicinity of the dilator (A, arrow) and sphincter muscles (B, arrow). Scale bar = 25 µm.

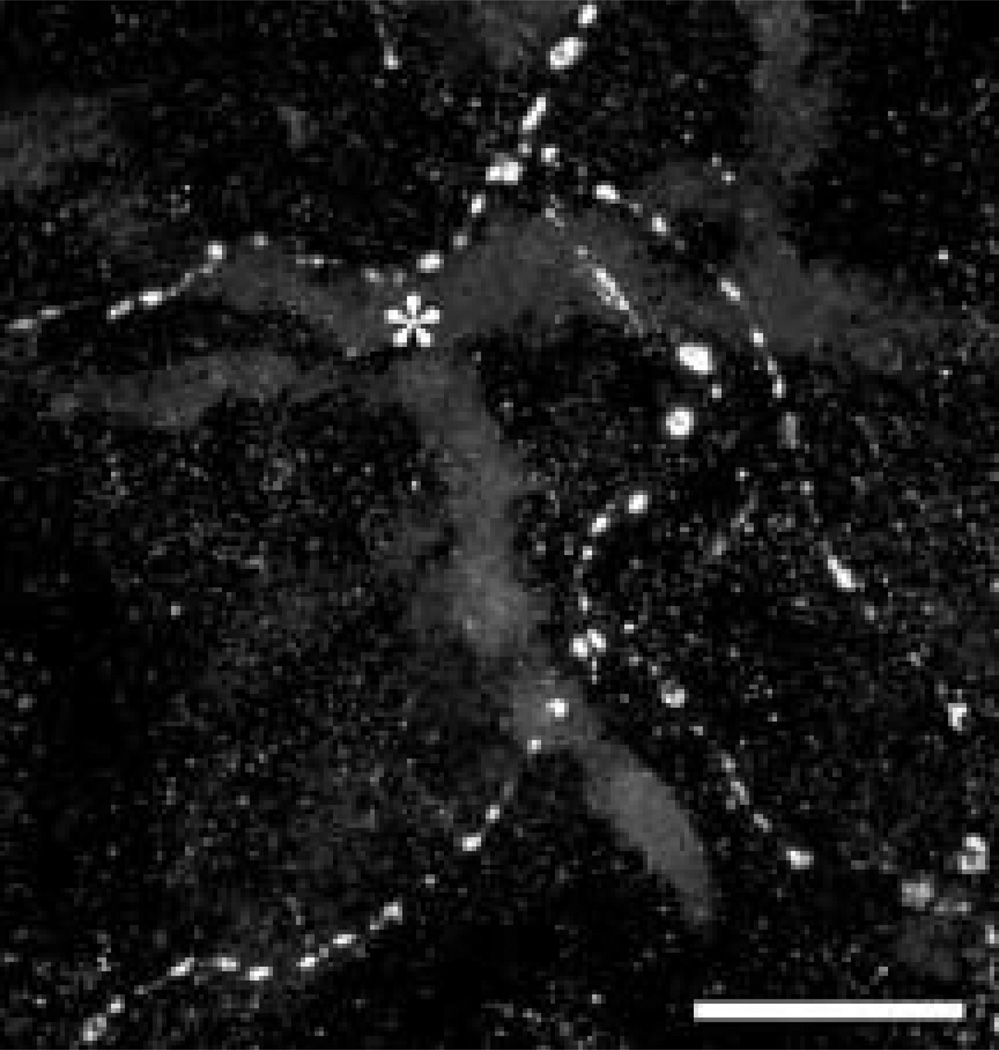

FIG. 12.

Varicose somatostatin-IR axons are found near medium-sized blood vessels (*) in a whole mount preparation of choroid. Scale bar = 25 µm.

The Origin of the Somatostatin-IR Axons

In the iris and ciliary body, somatostatin-IR axons ran alongside the ChAT-IR axons in many of the muscle bundles (Fig. 13). The somatostatin-IR and ChAT-IR axons were intertwined in the pupillary constrictor and dilator muscles and also in muscle bundles of the ciliary body. However, the somatostatin-IR axons did not contain ChAT-like immuno-reactivity, a finding suggesting that they are not parasympathetic.

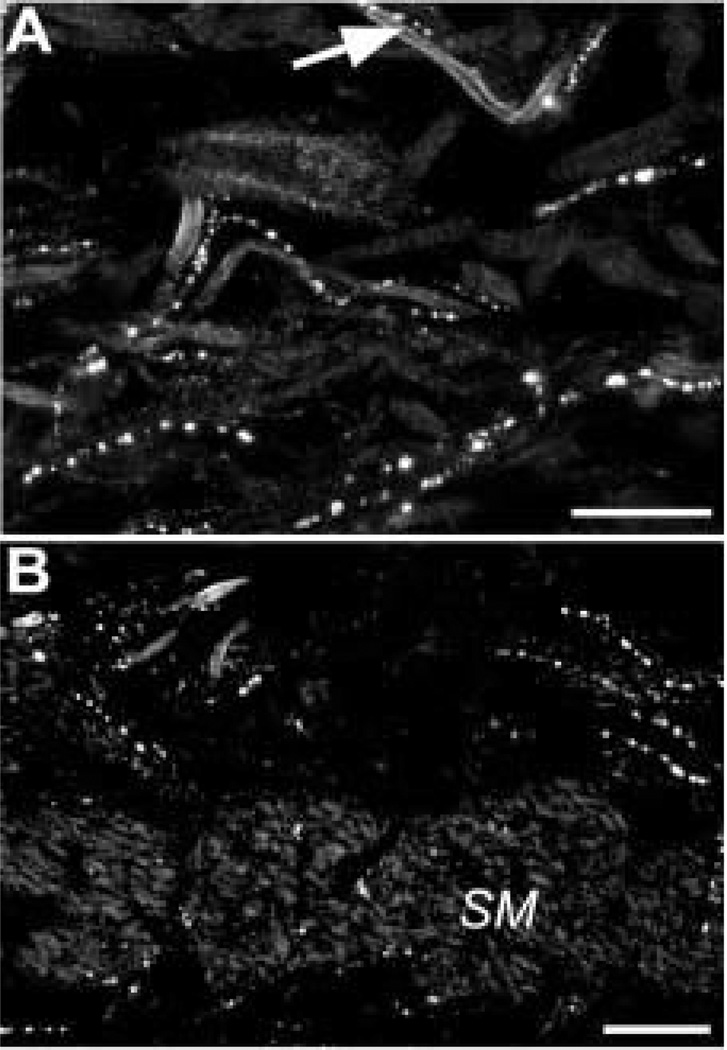

FIG. 13.

Somatostatin-IR (red) and ChAT-IR axons (green) are found together in the iris sphincter muscle (A) and radial muscle bundles in the ciliary body (B). However, somato-statin-IR axons do not contain ChAT-like immunoreactivity. Scale bar = 25 µm.

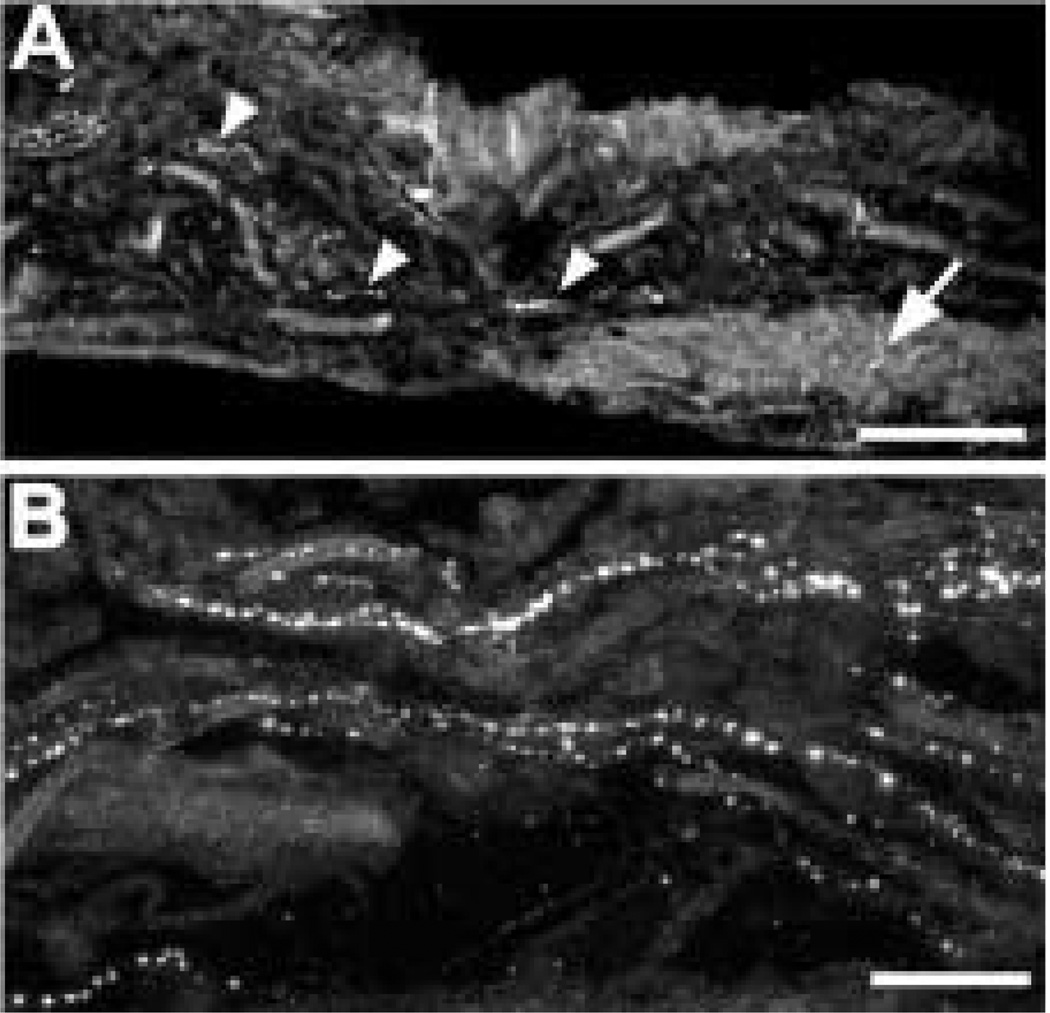

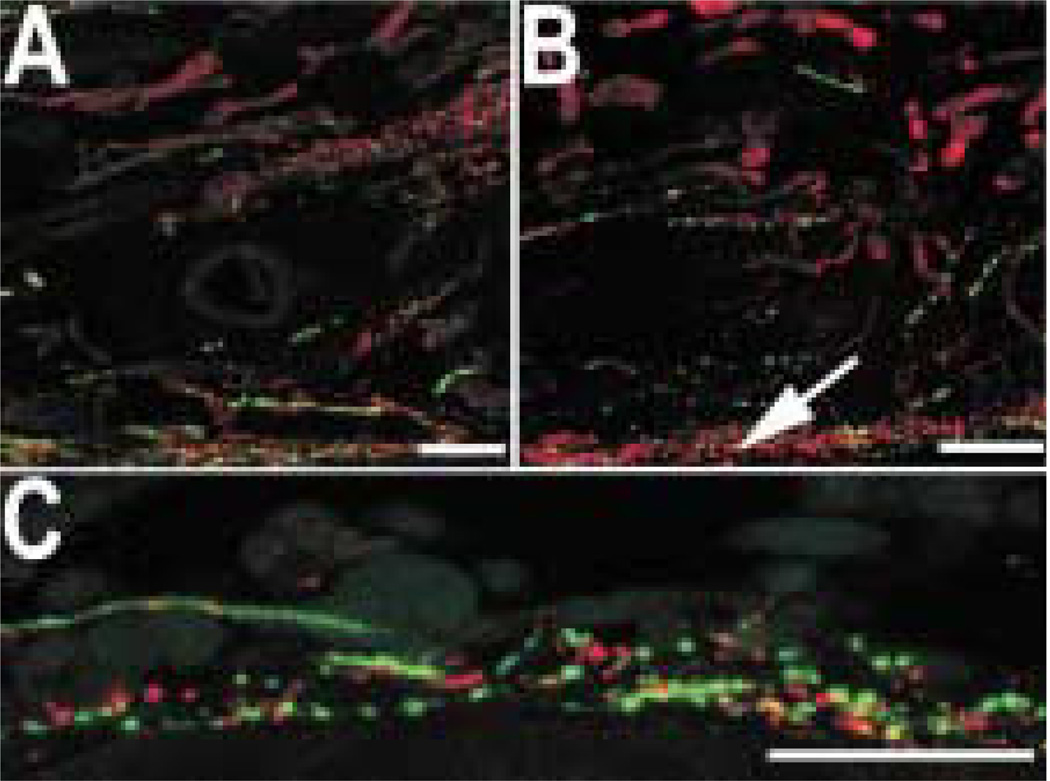

There was no consistent difference in the distribution of somatostatin-IR axons between the contral-ateral control eye, and the lesioned eye in the choroid, ciliary body or iris after the unilateral sympathectomy (Fig. 14(A) and (B)). The somatostatin-IR axons did not contain TH-like immunoreactivity, either (Fig. 14(C)). Taken together, these findings suggest that the somatostatin-IR axons are not sympathetic.

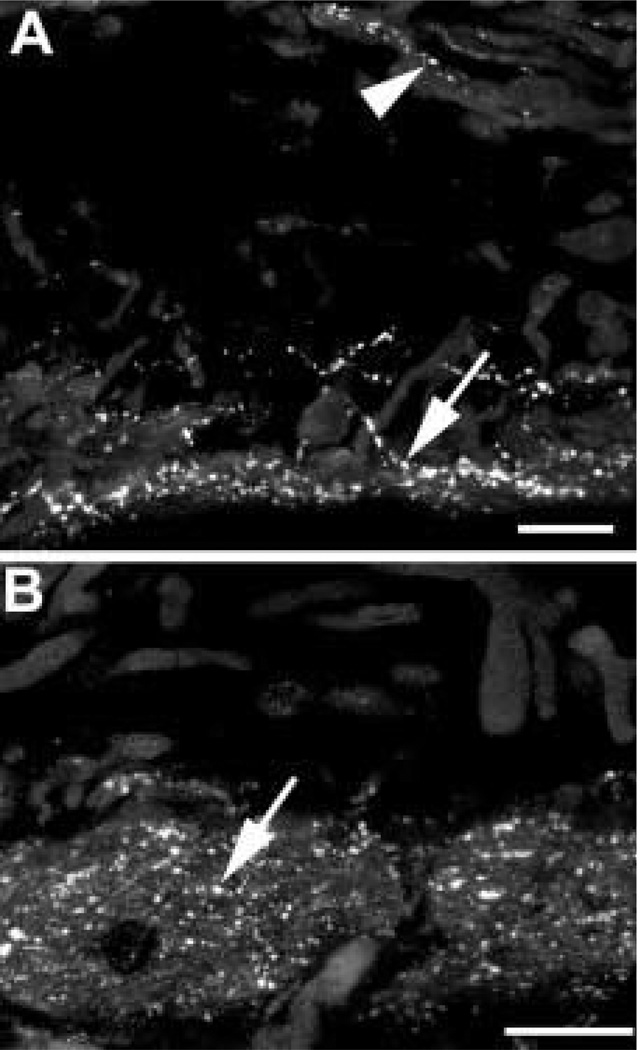

FIG. 14.

Somatostatin-IR (red) and TH-IR (green) axons are both found in the iris near the dilator muscle. Compared to the control eye (A), TH-like immunoreactivity is reduced in the sympathectomized eye (B), particularly near the dilator muscle (arrow). Axons in the vicinity of the dilator muscle from a normal animal are shown at a higher magnification (C). The somatostatin-IR axons do not contain TH-like immunoreactivity. Scale bar = 25 µm.

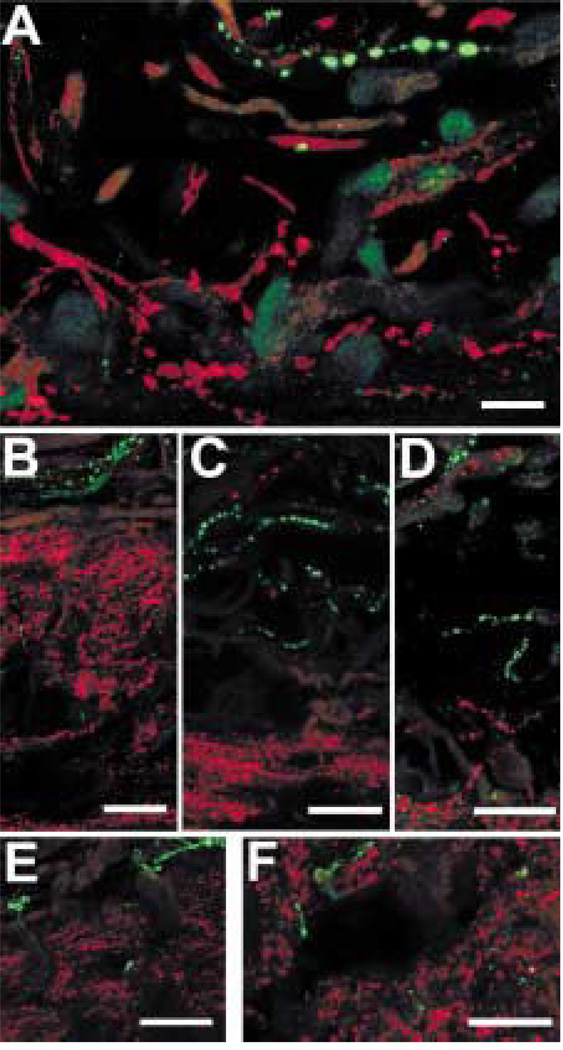

The somatostatin-IR axons are likely to be sensory because they did not contain ChAT-like or TH-like immunoreactivity. The somatostatin-IR and galanin-IR axons in the iris were clearly different in their distribution, and the somatostatin-IR axons did not contain galanin-like immunoreactivity (Fig. 15(A)). The somatostatin-IR axons also did not contain CGRP-like (Fig. 15(B)), substance P-like (Fig. 15(C)), gCCK-like (Fig. 15(D)) or 200 kDa neurofilament protein-like immunoreactivity (Fig. 15(E)), and they did not bind isolectin-IB4 (Fig. 15(F)).

FIG. 15.

In the iris, somatostatin-IR (red) axons do not contain galanin-like immunoreactivity (A, green). Scale bar =10 µm. Somatostatin-IR (red) axons did not contain other sensory markers (all green), either. These included CGRP (B), substance P (C), gCCK (D), a 200 kDa neurofilament protein (E). They also did not bind isolectin-IB4 (F). Scale bar = 25 µm.

4. Discussion

The neuropeptides galanin and somatostatin are found in two different subsets of sensory axons in the uvea. Neither the galanin-IR nor the somatostatin-IR axons contained markers of sympathetic or cholin-ergic nerves. As in previous studies, TH-IR axons were markedly reduced in the sympathectomized eye (Tamm et al., 1997), but there was no change in either the galanin-IR or somatostatin-IR axons. The distribution of these axons is generally consistent with previous anatomical descriptions of sensory axons in the monkey uvea. Ciliary nerves run anteriorly in the suprachoroid, making fine branches that innervate the choroidal stroma. These nerves enter the pars plana and then proceed in the lamina fusca or outermost layers of ciliary muscle at the interface of the ciliary muscle and sclera. Small branches occur in the pars plicata. Then some fibres proceed to the iris; only a few fibres innervate the rest of the ciliary muscle. The majority of the iris fibres run radially towards the pupil through the middle of the iris stroma (Bergmanson, 1977; Ruskell, 1994). In this study, sensory axons in the ciliary processes were seen, as well.

Galanin

The galanin-IR axons were sparse in the choroid and the ciliary body and more numerous in the iris. Galanin-IR axons were generally associated with the loose connective tissue in the iris stroma. The galanin-IR axons were not observed in the trabecular mesh-work or scleral spur, and this is consistent with a previous study in primates (Selbach et al., 2000). However, galanin-IR axons were observed in the limbal region, anterior to the canal of Schlemm. Galanin-IR axons had a similar distribution in the iris and ciliary body of rats (Stromberg et al., 1987) and pigs (Stone et al., 1988). In cats, the majority of the galanin-IR axons in the iris and ciliary body is of sympathetic origin, and they disappear after superior cervical ganglionectomy. A subset of the remaining galanin-IR axons also contained substance P-like immunoreactivity, and these sensory galanin-IR axons were distributed similarly (Grimes et al., 1994). Thus, all mammals studied to date have a population of galanin-IR sensory axons in the uvea.

In the human trigeminal ganglia, galanin-IR perikarya frequently contain substance P-like immunoreactivity (Del Fiacco and Quartu, 1994). Virtually all the galanin-IR axons in monkey also contained substance P-like immunoreactivity and CGRP-like immunoreactivity. In the iris, many of the galanin-IR axons also contain gCCK-like immunoreactivity. The presence of these peptides in galanin-IR axons strongly suggests that they are sensory in origin.

Galanin-IR axons in the iris also contained gCCK-like immunoreactivity. This is consistent with the finding that 10 % of the trigeminal neurons in monkeys express mRNA for CCK (Verge et al., 1993). CCK-IR sensory axons have also been described in the uvea of rats (Bjorklund et al., 1985) and guinea pigs (Stone et al., 1984; Kuwayama and Stone, 1986). But in these species, the CCK-IR axons were distributed more widely than in primates. Consistent with the finding that gCCK-IR axons were very rare in the ciliary body, CCK had no effect on blood flow to the ciliary body in monkeys (Almegard and Andersson, 1993). However, the presence of CCK in sensory axons in the iris of primates may be of interest clinically because non-cholinergic miosis is seen after ocular trauma or surgery. In the presence of a muscarinic cholinergic blocker, nanomolar concentrations of CCK-8 cause contraction of the isolated iris sphincter in primates, and CCKa receptor antagonists blocked this response (Bill et al., 1990; Almegard, Sternschantz and Bill, 1992).

The galanin-IR axons were found in the ciliary body near the ciliary epithelium. Receptors for galanin, the GalR-1 subtype, are expressed in human ciliary epithelium and in a cell line derived from that tissue (Ortego and Coca-Prados, 1998). Therefore, galanin released from sensory axons in the ciliary processes may influence the secretion of aqueous humor. The mRNA for preprogalanin is also expressed in human ciliary epithelium (Ortego and Coca-Prados, 1998). In this study, the ciliary epithelium was not labelled, but this technique is much less sensitive.

Sparse galanin-IR axons were found near the iris sphincter muscle. However, when galanin is applied alone, it has no effect on the primate iris (Almegard et al., 1992). However, galanin may modulate cholinergic transmission in the primate iris, as it does in rabbits. Galanin inhibits the acetylcholine-stimulated contraction of the rabbit iris sphincter, acting by a presynaptic mechanism (Ekblad et al., 1985).

Intrinsic neurons are present in human choroid (Flugel et al., 1994). In the duck choroid, many of these intrinsic choroidal perikarya contain galanin-like immunoreactivity (Schrodl et al., 2000). However, no galanin-IR perikarya were detected in the baboon or macaque uvea.

Somatostatin

Somatostatin-IR axons innervate a subset of muscle bundles and are closely associated with the para-sympathetic axons in both the ciliary body and iris. Somatostatin-IR axons are present in the iris stroma and ciliary processes, as well. Somatostatin-IR axons did not contain immunoreactive ChAT or TH, and therefore, they are likely to be of sensory origin. Somatostatin-IR perikarya have been reported previously in the human trigeminal ganglion (Del Fiacco and Quartu, 1994), and the same is true in macaques (unpublished observations). These perikarya rarely contain substance P-like immunoreactivity, a finding consistent with the observations that somatostatin-like and substance P-like immunoreactivity were not colocalized in the iris of monkeys (Del Fiacco and Quartu, 1994). Single varicose axons were commonly observed in the lamina fusca at the interface between the sclera and ciliary muscle. This is typical of sensory axons described previously by electron microscopy (Ruskell, 1994). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the somatostatin-IR axons in primates are sensory in origin.

In the iris and ciliary body, somatostatin-IR axons cofasiculate with ChAT-IR axons. Somatostatin and acetylcholine have synergistic effects on intracellular calcium levels in ciliary epithelium from rabbits. Somatostatin-14 and acetylcholine applied separately induced small, transient changes in intracellular calcium levels. When added together, however, somatostatin and acetylcholine increased intracellular calcium levels far more than predicted by the sum of the two (Xia et al., 1997). Somatostatin also inhibits forskolin-stimulated cAMP production in a preparation of isolated ciliary processes (Bausher and Horio, 1990) or isolated iris and ciliary body (Wax and Barrett, 1993). However, somatostatin-2 8 applied into the anterior chamber caused no change in pupil diameter (Almegard and Bill, 1993).

The somatostatin-IR axons, but not perikarya, were also found in the inner half of the choroid. In mice, a somatostatin analog reduces retinal neovascularization when given systemically. This effect may be mediated by a reduction in growth hormone secretion (Smith et al., 1997). Somatostatin may cause direct changes in the choroid as well because somatostatin receptors (SSTR2A) have been localized to thick-walled blood vessels and to a lesser extent to the chorioca-pillaris of the human choroid (Lambooij et al., 2000). Pathological neovascularization in monkey choroid can develop secondary to age-related macular degeneration or diabetes (Smith et al., 1997; Lambooij et al., 2000), and it is possible that the role of somatostatin in the normal choroid is to control this process.

Somatostatin receptors have also been localized in the anterior uvea. Using reverse transcriptase-poly-merase chain reaction, all five somatostatin receptor subtypes were detected in rat iris/ciliary body, and the predominant subtype was SSTR4. In situ hybridization demonstrated diffuse expression of SSTR4 throughout the ciliary body. In the iris, SSTR4 is expressed in posterior epithelium and dilator muscle of the iris (Mori et al., 1997). Based on the extensive plexus of somatostatin-IR axons detected in the monkey sphincter muscle, somatostatin receptors might be expected in this area of the primate iris as well. SSTR4 was the only subtype studied by in situ hybridization, and the somatostatin receptors expressed in the sphincter region may be one of the other subtypes.

5. Conclusion

The distribution of two peptides, galanin and somatostatin, in different populations of sensory axons in the monkey uvea was described. In addition to conveying sensory information, these axons probably release these peptides when they are injured or intensely stimulated. On the basis of results in other sensory systems, these peptides might decrease excitability of the sensory axons and limit damage to the uvea (Heppelmann et al., 2000; Carlton et al., 2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lillemor Krosby for her technical assistance. Grant support was from the Robert J. Kleberg Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation and EY06472, EY02698 from the National Eye Institute.

References

- Almegard B, Andersson SE. Vascular effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and chole-cystokinin (CCK) in the monkey eye. J. Ocular Pharmacol. 1993;9:77–84. doi: 10.1089/jop.1993.9.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almegard B, Sternschantz J, Bill A. Cholecystokinin contracts isolated human and monkey iris sphincters: a study with CCK receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;211:183–187. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90527-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almegard B, Bill A. C-terminal calcitonin gene-related peptide fragments and vasopressin but not somatostatin-28 induce miosis in monkeys. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;250:31–35. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90617-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez FJ, Priestley JV. Anatomy of somatostatin-immunoreactive fibres and cell bodies in the rat trigeminal subnucleus caudalis. Neuroscience. 1990;38:343–357. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambalavanar R, Morris R. The distribution of binding by isoIectin-I-B4 from Giffonia simplicifolia in the trigeminal ganglion and brainstem trigeminal nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1992;47:421–429. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausher LP, Horio B. Neuropeptide Y and somatostatin inhibit stimulated cyclic AMP production in rabbit ciliary processes. Curr. Eye Res. 1990;9:371–376. doi: 10.3109/02713689008999625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman E, Carlsson K, Liljeborg A, Manders E, Hokfelt T, Ulfhake B. Neuropeptides, nitric oxide synthase and GAP-43 in B4-binding and RT97 immunoreactive primary sensory neurons: normal distribution pattern and changes after peripheral nerve transection and aging. Brain Res. 1999;832:63–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmanson JPG. The ophthalmic innervation of the uvea in monkeys. Exp. Eye Res. 1977;24:225–240. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(77)90160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A, Andersson SE, Almegard B. Cholecystokinin causes contraction of the pupillary sphincter in monkeys but not cats, rabbits, rats and guinea-pigs: antagonism by lorglumide. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1990;138:479–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1990.tb08875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund H, Fahrenkrug J, Seiger A, Vanderhaeghen J, Olsen L. On the origin and distribution of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-, peptide HI-, and cholecystokinin-like-immunoreactive nerve fibers in the rat iris. Cell Tiss. Res. 1985;242:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00225556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton SM, Du J, Davidson E, Zhou S, Coggeshall RE. Somatostatin receptors on peripheral primary afferent terminals: inhibition of sensitized nociceptors. Pain. 2001;90:233–244. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Fiacco M, Quartu M. Somatostatin, galanin and peptide histidine isoleucine in the newborn and adult human trigeminal ganglion and spinal nucleus: immunohistochemistry, neuronal morphome-try and colocalization with substance. P. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1994;7:171–184. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekblad E, Hakanson R, Sundler F, Wahlestedt C. Galanin: neuromodulatory and direct contractile effects on smooth muscle preparations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;86:241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb09455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbadri AA, Shaw C, Johnson CF, Archer DB, Buchanan KD. The distribution of neuropeptides in ocular tissues of several mammals: a comparative study. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. 1991;100:625–627. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(91)90051-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flugel C, Tamm ER, Mayer B, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Species differences in choroidal vasodilative innervation: evidence for specific intrinsic nitrergic and VIP-positive neurons in the human eye. Invest. Ophthal-mol. Vis. Sci. 1994;35:592–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes PA, McGlinn AM, Koeberlein B, Stone RA. Galanin immunoreactivity in autonomic innervation of the cat eye. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;348:234–243. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes PA, McGlinn AM, Stone RA. An immunohistochemically distinct population of ciliary ganglion cells. Brain Res. 1990;535:323–326. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91617-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppelmann B, Just S, Pawlak M. Galanin influences the mechanosensitivity of sensory endings in the rat knee joint. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:1567–1572. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Katayama Y, Yui R. On the occurrence and physiological effect of somatostatin in the ciliary ganglion of cats. Brain Res. 1982;247:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer W, Heym C. Correlation of neuronal size and peptide immunoreactivity in guinea-pig trigeminal ganglion. Cell Tiss. Res. 1986;245:657–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00218569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama Y, Stone RA. Cholecystokinin-like immunoreactivity occurs in ocular sensory neurons and partially co-localizes with substance P. Brain Res. 1986;381:266–274. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambooij AC, Kuijpers RWAM, van Lichtenauer-Kaligis EGR, Kliffen M, Baarsma GS, van Hagen PM, Mooy CM. Somatostatin receptor 2A expression in choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:2329–2335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov N. Primary trigeminal afferent neuron of the cat: II. Neuropeptide- and serotonin-like immunoreactivity. J. Hirnforsch. 1994;35:3 73–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luebke JI, Wright LL. Characterization of superior cervical ganglion neurons that project to the submandibular glands, the eyes and the pineal gland. Brain Res. 1992;589:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama T, Wanaka A, Yoneda S, Kimura K, Kamada T, Girgis S, MacIntyre I, Emson PC, Tohyama M. Two distinct calcitonin gene-related peptide-containing peripheral nervous systems: distribution and quantitative differences between the iris and cerebral artery with special reference to substance P. Brain Res. 1986;373:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Costa M, Furness JB, Chubb IW. Substance P immunoreactive sensory nerves supply the rat iris and cornea. Neurosci. Lett. 1981;23:243–249. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Aihara M, Shimizu T. Differential expression of somatostatin receptors in the rat eye: SSTR4 is intensely expressed in the iris/ciliary body. Neurosci. Lett. 1997;223:185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortego J, Coca-Prados M. Molecular identification and coexpression of galanin and GaIR-1 galanin receptor in the human ocular epithelium: differential modulation of their expression by activation of α2 and β2-adrenergic receptors in cultured ciliary epithelial cells. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:2260–2270. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71062260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ositelu DO, Morris R, Vaillant C. Innervation of facial skin but not masticatory muscles or the tongue by trigeminal primary afferents containing somatostatin in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1987;78:271–276. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JC, Kaufman PL. Superior cervical ganglionectomy in monkeys: surgical technique. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1992;33:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskell GL. Trigeminal innervation of the sceral spur in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Anat. 1994;184:511–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodl F, Brehmer A, Neuhuber WL. Intrinsic choroidal neurons in the duck eye express galanin. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;425:24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach JM, Gottanka J, Wittmann M, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Efferent and afferent innervation of primate trabecular meshwork and scleral spur. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:2184–2191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JD, Kruger L. Selective neuronal glycoconjugate expression in sensory and autonomic ganglia: relation of lectin reactivity to peptide and enzyme markers. J. Neurocytol. 1990;19:789–801. doi: 10.1007/BF01188046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LEH, Kopchick JJ, Chen W, Knapp J, Kinose F, Daley D, Foley E, Smith RG, Schaeffer JM. Essential role of growth hormone in ischaemia-induced retinal neovascularization. Science. 1997;276:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RA, Kuwayama Y, Laties AM, McGIinn AM, Schmidt ML. Guinea-pig ocular nerves contain a peptide of the cholecystokinin/gastrin family. Exp. Eye Res. 1984;39:387–391. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(84)90026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RA, Laties AM, Brecha NC. Substance P-immunoreactive nerves in the anterior segment of the rabbit, cat and monkey eye. Neuroscience. 1982;7:2459–2468. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RA, McGIinn AM, Kuwayama Y. Galanin-like immunoreactive nerves in the porcine eye. Exp. Eye Res. 1988;46:457–461. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(88)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg I, Bjorklund H, Melander T, Rokaeus A, Holkfelt T, Olson L. Galanin-immuno-reactive nerves in the rat iris: alterations induced by denervations. Cell Tiss. Res. 1987;250:267–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00219071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Rohen JW, Schmidt K, Robinson JC, Wallow IHL, Kaufman PL. Superior cervical ganglionectomy in monkeys: light and electron microscopy of the anterior eye segment. Exp. Eye Res. 1997;65:31–43. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terenghi G, Polak JM, Ghatei MA, Mulderry PK, Butler JM, Unger WG, Bloom SR. Distribution and origin of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) immunoreactivity in the sensory innervation of the mammalian eye. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;233:506–516. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verge VMK, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Hokfelt T. Cholecystokinin in mammalian primary sensory neurons and spinal cord: in situ hybridization studies in rat and monkey. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1993;5:240–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wax MB, Barrett DA. Regulation of adenylate cyclase in rabbit iris ciliary body. Curr. Eye Res. 1993;12:507–520. doi: 10.3109/02713689309001829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S-L, Fain GL, Farahbakhsh NA. Synergistic rise in Ca2+ produced by somatostatin and acetylcholine in ciliary body epithelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 1997;64:627–635. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]