Abstract

Background

Chronic ankle instability (CAI) is a disabling condition often encountered after ankle injury. Three main components of CAI exist; perceived instability; mechanical instability (increased ankle ligament laxity); and recurrent sprain. Literature evaluating CAI has been heavily focused on adults, with little attention to CAI in children. Hence, the objective of this study was to systematically review the prevalence of CAI in children.

Methods

Studies were retrieved from major databases from earliest records to March 2013. References from identified articles were also examined. Studies involving participants with CAI, classified by authors as children, were considered for inclusion. Papers investigating traumatic instability or instability arising from fractures were excluded. Two independent examiners undertook all stages of screening, data extraction and methodological quality assessments. Screening discrepancies were resolved by reaching consensus.

Results

Following the removal of duplicates, 14,263 papers were screened for eligibility against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Nine full papers were included in the review. Symptoms of CAI evaluated included perceived and mechanical ankle instability along with recurrent ankle sprain. In children with a history of ankle sprain, perceived instability was reported in 23-71% whilst mechanical instability was found in 18-47% of children. A history of recurrent ankle sprain was found in 22% of children.

Conclusion

Due to the long-lasting impacts of CAI, future research into the measurement and incidence of ankle instability in children is recommended.

Keywords: Ankle, pediatrics, joint instability, sprains and strains

Background

Chronic ankle instability (CAI) is a debilitating condition commonly encountered after ankle injury [1]. Three main components of CAI exist; perceived instability, mechanical instability and recurrent sprain [2]. People may experience one, two or all of these components. Perceived instability often involves the feeling that the ankle gives way and/or is unsteady during activity, weaker or less functional when compared to a steadier ankle, or prior to injury [1,3]. The perception that the ankle joint is unsteady is thought to be associated with impairments in neuromuscular and postural control, making the ankle vulnerable to repeated sprain [4,5].

CAI is common, with many adults enduring negative impacts long into the future. Following ankle sprain, up to 32% of people will develop CAI [6]. Of these, 72% will have their function impaired [6]. Activity is often impacted by the symptom of recurrent sprain, causing 18% of people to report a decreased ability to play sport, and 11% to be unable to walk long distances [7]. CAI leads to changes in, or the cessation of, sporting and occupational activities [6,8].

Research to date has been heavily focused on adults and there appears to be little attention on the prevalence of CAI specific to the pediatric population. The limited body of research on CAI in children reports that it is commonly suffered by children following sporting injuries [9], hypermobility [10] and in those with inherited neuropathies such as Charcot Marie Tooth disease (CMT). CMT is a peripheral nerve disease which commonly inflicts symptoms of a cavus foot deformity, muscle atrophy, decreased sensation, and peripheral weakness [11,12]. This results in ankle unsteadiness, causing trips, falls and ankle sprain injuries [13].

Due to the long lasting impacts CAI inflicts on the quality of life and activity of adults, it is important to investigate CAI in children [6-8]. With deeper understanding of CAI in children, targeted early intervention strategies may be developed to prevent prolonged suffering of symptoms [6-8]. Therefore the objective of this paper was to systematically review the prevalence of CAI in children.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion studies must have focused on CAI, commonly defined as experiencing perceived instability, mechanical instability or recurrent sprain [4,14], although papers reporting any long-term problems following ankle sprain were included. All study types were included, with the exception of single case studies and narrative and systematic reviews. There were no language restrictions. Participants aged up to 18 years old were included along with studies including participants classified by the author(s) as children.

Exclusion criteria

Studies investigating ankle instability following fractures to bones of the ankle joint were excluded from the review. Papers including a mixed sample of children and adult participants were excluded if authors could not provide original, separated data sets.

Search strategy

Studies were retrieved from electronic databases, from inception until March 2013 including: Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane, SCOPUS, PubMed, SPORTDiscus, CINAHL and Embase. Additionally, reference lists of included studies were examined for any additional studies that met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 illustrates the search strategy utilised for the Medline database, which was modified for each database.

Table 1.

Medline search strategy

| #1: Terms combined with ‘OR’ | #2: Terms combined with ‘OR’ | #3: Terms combined with ‘OR’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The ankle |

Instability |

Injury |

Diagnosis and measurement |

Children |

| Ankle |

Ankle instability |

Sprains and strains |

Instability measurement |

Child |

| Ankle joint |

Chronic instability |

Inversion sprain |

Measurement |

Paediatric |

| Talocrural |

|

Inversion injury |

Instability diagnosis |

Pediatric |

| Talocalcaneal |

Chronic |

Repeated sprain |

Diagnosis |

Boy |

| Tibiotalar |

Joint instability |

Repeated injury |

Laxity |

Girl |

| Talofibular |

Mechanical instability |

Recurrent sprain |

|

Adolescent |

| High ankle |

Functional instability |

Recurrent injury |

|

Teen |

| |

Perceived instability |

Wounds and injury |

|

Teenager |

| |

Unstable |

Syndesmosis |

|

Youth |

| |

|

Lateral ligament, ankle |

|

Young |

| |

|

Collateral ligament |

|

|

| |

|

Talofibular ligament |

|

|

| |

|

Calcaneofibular ligament |

|

|

| Combined search: [#1 AND #2] AND #3 | ||||

Three authors [15-17] were contacted to provide original data sets for analysis. Authors were contacted to obtain additional data for a variety of reasons including; combined scores for foot and ankle problems were reported [15], data for children and adults were reported together [16] or additional baseline data for ankle instability was not provided [17]. One author responded, providing original datasets for the study by Hiller et al.[17] regarding the laxity and sprain history of participants.

Assessment for study inclusion

Two independent examiners (MM and either AS or FP) screened titles, abstracts and full texts of papers according to eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were settled by a consensus, or if necessary, an additional examiner (CH).

Methodological quality assessment

Methodological quality was assessed using a modified Downs and Black’s [18] checklist for randomized and non-randomized studies of health care interventions. Criteria assessed included: clear descriptions of the aims, outcome measures and participants, correct reporting and statistical analysis of results, the representativeness and groupings of participants, and reporting of dropouts [18]. The assessment tool provided a score out of 14. Some criteria such as participant blinding were irrelevant to some studies, hence scores were represented as a percentage for comparisons to be made. Two independent examiners assessed and rated studies (MM and either AS or FP). After independent review, discrepancies were settled by consensus. When consensus could not be reached, an additional examiner evaluated the quality to reach a final decision.

Results

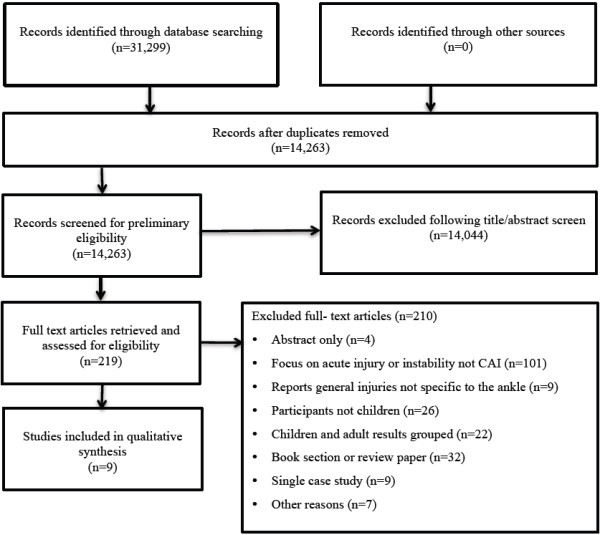

Initial searching resulted in 31,299 papers. Following the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 14,263 papers were screened for potential eligibility. After initial screening, 219 articles were identified as potentially eligible and full texts were sought. Succeeding full text review and the translation of a German paper [19], nine full papers were included in the review (Figure 1) [17,19-26]. Papers were grouped according to the components of CAI investigated including: 1. Perceived instability, reporting data on patient’s perceptions of the ankle joint as being less functional, weak or painful; 2. Mechanical instability, involving measures of ligamentous laxity of the ankle; and 3. Recurrent sprain. Symptoms of CAI including perceived and mechanical ankle instability were explored in five studies [17,19,20,22,24] and prevalence of recurrent sprain in four studies [17,21,23-26] (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Table 2.

Included studies in qualitative synthesis

| Author, year | Study type | Participants | Follow up | Sample size | Measurement of CAI | Epidemiology of CAI- prevalence/distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hiller

et al. 2008

[17] |

Prospective cohort |

Adolescent dancers 14.2 ± 1.8 yrs |

13 months |

116 |

Ankle instability (CAIT) |

36% of all dancers unstable |

| 71% of sprainers unstable | ||||||

| Ankle joint laxity (mod ant draw) |

37% right, 47% left ankles moderate to very lax |

|||||

| Self report |

50% of total had history of sprain |

|||||

| 22% of total had history of ≥2 sprains | ||||||

| 38 sprains were sustained by 33 participants | ||||||

| Incidence of sprains 0.21/1000 hours of dancing | ||||||

|

Hollwarth

et al. 1985

[19] |

Retrospective |

Patients with high ankle sprain, severe trauma for inclusion |

6 yrs |

96 |

Subjective complaints; rolling over, pain, swelling, meterosensitivity |

31.3% subjective complaints |

| 16 (range: 9–21) yrs |

X-ray (AP and lateral) injured side, talar tilt stress x-ray both sides |

17.7% ligament avulsions |

||||

| Ligament stiffness, pain during supination or palpation of, fibular ligaments or syndesmosis |

38.5% “pathologic clinical findings” |

|||||

| Abnormal talar tilt (> 5 deg) |

42% abnormal |

|||||

|

Marchi

et al. 1999

[20] |

Prospective cohort |

Patients with moderate to severe ankle injury 6–15 yrs. 26 female (48%) |

3 yrs |

220 |

Medical report of objective (limited joint mobility, pain on pressure, axial deviations, weakness, or shortening of a limb) and subjective (pain at rest or during exercise, sense of unsteadiness, or paraesthesia) symptoms |

42% had objective or subjective symptoms (3 yrs follow up) |

| 12 yrs |

54 |

23% had permanent symptoms (Risk ratio: 1.79, p = 0.10) (12 yrs follow up) |

||||

|

Soderman

et al. 2001

[21] |

Prospective cohort |

Adolescent female soccer players 15.9 ± 2.1 (range: 14–19) yrs |

1 season |

153 |

Medical report of re-injuries |

56% of sprainers had recurrent sprain |

|

Steffen

et al. 2008

[22] |

Prospective cohort |

Female soccer players 15.4 ± 0.8 (range: 14–16) yrs |

- |

1430 |

Self report of sprain history |

Players with previous ankle injury (PI) more likely to sustain new ankle injury than those without (NH) (Rate ratio = 1.2 [1.1; 1.3] p < .001). |

| FAOS |

92.0 ± 11.3 (PI), 97.3 ± 6.0 (NH) mean difference: −5.3 (95% CI = −6.0 to −4.5) |

|||||

| Pain |

62.8 ± 11.1 (PI), 68.2 ± 9.7 (NH) mean difference: −5.4 (95% CI = −6.3 to −4.5) |

|||||

| Symptoms |

96.3 ± 7.5 (PI), 98.7 ± 4.2 (NH) mean difference: −2.3 (95% CI = −2.9 to −1.8) |

|||||

| Activities of daily living |

89.0 ± 16.2 (PI), 96.3 ± 8.4 (NH) mean difference: −7.3 (95%CI = −8.4 to −6.2) |

|||||

| Sport and recreation function |

71.3 ± 12.4 (PI), 76.3 ± 10.0 (NH) mean difference: −5.0 (95% CI = −5.9 to −4.0) |

|||||

| Ankle-related quality of life |

411.5 ± 46.8 (PI), and 436.7 ± 26.8 (NH) mean difference: −25.2 |

|||||

| (95% CI = −28.5 to −21.9) | ||||||

|

Swenson

et al. 2009

[23] |

Descriptive epidemiology study |

High school students |

- |

100 high schools 13755 injuries |

Medical report of re-injury |

Ankle most frequently diagnosed site for recurrent injury in basketball (boys: 58.4%, girls: 43.6%), volleyball (42.7%), soccer (boys: 34.8%, girls: 37.2%), football (29.8%), softball (26.3%), and wrestling (20.1%) |

| 28% of all recurrent injuries were ankle injuries | ||||||

| More recurrent (28%) than new ankle injuries (19%) (Injury Proportion Ratio = 1.47; 95% CI, 1.31-1.65) | ||||||

|

Timm

et al. 2005

[24] |

Prospective cohort |

Emergency department patients with ankle injury |

6 weeks |

199 |

Medical report of: |

|

| Pain with activity |

24 (34%) OW, 14 (15%) NW, RR = 2.25 (95% CI = 1.25-4.02) |

|||||

| Range: 8–18 yrs |

Persistent swelling and/or weakness |

22 (31%) OW, 12 (13%) NW, RR = 2.40 (95% CI = 1.28-4.52) |

||||

| Re-injury |

17 (24%) OW, 14 (15%) NW, RR = 1.60 (95% CI = 0.84-3.01) |

|||||

| OW mean age = 13.9 yrs |

6 months |

171 |

Pain with activity |

19 (41%) OW, 19 (16%) NW, RR = 2.57 (95% CI = 1.50-4.39) |

||

| NW mean age = 13.5 years. |

Persistent swelling and/or weakness |

16 (34%) OW, 18 (15%) NW, RR = 2.28 (95% CI = 1.28-4.08) |

||||

| Re-injury |

12 (26%) OW, 19 (16%) NW, RR = 1.62 (95% CI = 0.86-3.06) |

|||||

| 31 (44%) of OW had persistent ankle symptoms at 6 months compared with 24 (26%) NW (RR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.10-2.61) | ||||||

|

Tyler

et al. 2006

[25] |

Cohort study |

Male high school football players |

3 seasons |

152 |

Medical report of sprain history |

50 (33%) had history of previous ankle sprain 15 non-contact ankle sprains were incurred. Of the 11 players who had a previous ankle sprain and sustained a noncontact sprain in this study, 9 (82%) injured the same ankle (incidence 2.1) |

|

Weir & Watson 1996[26] |

Prospective cohort |

Physical education students |

1 yr |

266 |

Self report of injuries |

230 injuries were incurred. The most common injuries were ankle sprains. |

| Males (56%): 14.3 ± 0.85 (range: 12–15) yrs |

7 overuse injuries of the ankle were incurred. 100% of overuse injuries of the ankle were re-injuries. |

|||||

| Females: 14.1 ± 0.90 (range: 12–15) yrs |

KEY: CAI = Chronic Ankle Instability, CAIT = Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool, FAOS = Foot and Ankle Outcome Score, Mod ant drawer = modified anterior drawer test, OW = Children who are Overweight (≥85th BMI percentile), NW = children who are of Normal Weight (<BMI 85th percentile).

Table 3.

Overview of included studies regarding components of chronic ankle instability investigated

| Component of CAI investigated | Author | Participant number | Participant characteristics | Measurement | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived instability |

Hiller et al.[17] |

116 |

Adolescent dancers |

CAIT |

71% of sprainers unstable |

| Hollwarth et al.[19] |

96 |

Severe ankle trauma |

Self report |

31% had complaints |

|

| Marchi et al.[20] |

220 |

Moderate-severe ankle injury |

Medical report |

42% had complaints 3 yrs post injury |

|

| 54 |

23% had complaints 12 yrs post injury |

||||

| Steffen et al.[22] |

1430 |

Adolescent soccer players |

FAOS |

Lower function in previously injured than with no previous injury at baseline (mean diff = −25 (95% CI = −28.5 to -21.9) |

|

| Timm et al.[24] |

99 |

Patients with ankle injury |

Medical report |

34% had complaints |

|

| 44% of overweight children (BMI > 85th percentile) | |||||

| Mechanical instability |

Hiller et al.[17] |

116 |

Adolescent dancers |

Mod ant drawer |

37% Right, 47% Left of all ankles moderate to very lax |

| Hollwarth et al.[19] |

96 |

Severe ankle trauma |

X-ray |

18% had ligament avulsion |

|

| Clinical tests |

39% had pathologic clinical findings (as defined by authors) |

||||

| Talar tilt >5° |

42% of total had abnormal talar tilt |

||||

| Recurrent sprain |

Hiller et al.[17] |

116 |

Adolescent dancers |

Self report |

22% had ≥2 sprains |

| Soderman et al.[21] |

153 |

Adolescent soccer players |

Medical report |

56% of sprainers had recurrent sprain |

|

| Swenson et al.[23] |

13755 injuries |

High school students |

Medical report |

25% of all recurrent injuries were ankle injuries |

|

| Timm et al.[24] |

199 |

Patients with ankle injury |

Self report |

26% of overweight (BMI > 85th percentile) and16% normal weight reinjured |

|

| Tyler et al.[25] |

152 |

High school footballers |

Medical report |

15 non-contact ankle sprains incurred and 9 (60%) were re-sprains of the same ankle |

|

| Weir & Watson [26] | 266 | Physical education students | Self report | 100% overuse ankle injuries were re-injuries |

KEY: BMI = Body Mass Index, CAI = Chronic Ankle Instability, CAIT = Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool, CI = Confidence Interval, FAOS = Foot and Ankle Outcome Score, Mean Diff = Mean Difference.

Quality

The average quality of the papers was high, meeting 80.4% of the criteria (range: 38-100%, Table 4). Six papers [20-23,25,26] did not blind assessors as this was inappropriate to the study design. Other criterion commonly unfulfilled was the reporting of exact p values [19,21,23,25,26] and the number of participants lost to follow up [22,25,26].

Table 4.

Results of modified Downs and Black’s quality assessment tool

|

Study |

Criteria |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | 1 Hypotheses/objectives | 2 Outcomes | 3 Participants | 4 Findings | 5 Data distribution | 6 p value | 7 Participant Selection | 8 Represent-activeness | 9 Blinding | 10 Statistics | 11 Outcome measures | 12 Intervention groups | 13 Time period | 14 Follow up | Total | Percentage (%) |

| Hiller et al. |

2008 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

N/A |

N/A |

1 |

12/12 |

100 |

| Hollwarth et al. |

1985 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0* |

0* |

0* |

0* |

0* |

1 |

1 |

N/A |

5/13 |

38 |

| Marchi et al. |

1999 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

N/A |

N/A |

1 |

10/12 |

83 |

| Soderman et al. |

2001 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

N/A |

N/A |

1 |

11/12 |

92 |

| Steffen et al. |

2008 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

N/A |

N/A |

0* |

10/12 |

83 |

| Swenson et al. |

2009 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

9/11 |

82 |

| Timm et al. |

2005 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

14/14 |

100 |

| Tyler et al. |

2006 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0* |

10/14 |

71 |

| Weir & Watson | 1996 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 0* | 9/12 | 75 |

KEY:

1 Criteria met.

0 Criteria not met.

*Unable to determine, scored 0.

N/A Criteria did not apply to study type.

Perceived instability

Five papers investigated perceived instability including pain and impaired ankle function [17,19,20,22,24]. Symptoms of ankle instability were investigated in specific populations including dancers [17], soccer players [22], children who were overweight [24], or who had experienced “severe ankle trauma” (undefined by authors) [19,20]. Symptoms of perceived instability, pain, weakness, swelling or paraesthesia were investigated in dancers [17] and in children following ankle injuries [20,24]. Ankle injuries were self-reported via recall or diagnosed by a medical practitioner. Perceived instability was measured using tools including the Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool (CAIT) [14] and the Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS) [22], and through medical [20,24] and self reports [19].

Perceived instability and impaired ankle function during activity was common. Prevalence of perceived instability ranged from 31% in children with severe ankle injuries [19] to 71% of children who were dancers [14] (Table 3). The risk of perceived ankle instability was greatest for children who were overweight (≥ 85th percentile for Body Mass Index [BMI]) [24] of a younger age [20] and in those with abnormal talar tilt [19]. For every unit increase of BMI, the risk of having long term symptoms of instability increased 0.66% (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12; p = 0.01) [24]. Of note, “permanent symptoms” of instability (lasting up to 12 years) were more frequent for injuries sustained by children under 10 years, compared to children aged over 10 years who were prone to more temporary symptoms (lasting 3 years, p < 0.05) [20]. Subjective complaints of poor ankle functioning were most notable in those who had a history of ankle injury [23] and in children following severe ankle trauma with abnormal talar tilt (>5°) [19].

Mechanical instability

Mechanical instability following ankle sprain was investigated in two studies using four measures. Prevalence of mechanical instability was between 18% of children following severe ankle trauma [19] and 47% children who were dancers [17] (Table 2). A modified anterior drawer test identified increased laxity in adolescent dancers to be associated with lower CAIT scores, indicative of higher ankle instability (r = −0.484, p < 0.01) [17]. Stress x-ray and talar tilt revealed a high prevalence of abnormal talar tilting (>5°) in 42% of children six years after severe ankle trauma [19].

Recurrent sprain

Six studies investigated recurrent sprain or re-injury rates using self or medical reports (Table 3) [17,21,23-26] using self [17,24,26] or medical reports [21,23,25]. A history of sprain ranged from 22% in football players [25] to 50% in dancers [17]. Only one study reported results of recurrent ankle sprain across a population, finding 22% of dancers had a history of recurrent sprain [17] (Table 2). The prevalence of recurrent sprain in children who had previously sprained their ankle ranged from 16% of normal weight children presenting to an emergency department for an ankle injury and 100% of ankle injuries sustained by physical education students [26]. Overweight children experienced a higher incidence of re-injuries to the ankle than those of normal weight (Table 2) [24].

Discussion

CAI is a problem in the pediatric population as illustrated by the high prevalence of perceived instability, mechanical instability and recurrent sprain in specific groups of children with: past ankle injuries [19,20,23,26], dancers [17], soccer players [21,22], and those with a high BMI [24,25].

The prevalence of perceived instability was as high as 71% in children following ankle injury across the specific populations studied, with many participants reporting symptoms lasting up to 12 years [20]. Characteristics of perceived ankle instability via self-reporting of symptoms were noted in dancers [17], soccer players [22] and children who were overweight [24]. A systematic review of ankle sprains in adults reports a prevalence of perceived instability following acute ankle sprain ranging between 7% and 53% [27]. Perceived ankle instability in particular has been shown to have a large impact in adults, leading to changes in sporting and occupational activities [8]. The prevalence found in children is higher than the reported prevalence in adults. This may not be reflective of a true difference due to different testing methodologies employed. Perceived instability was measured with adult questionnaires including the CAIT and the FAOS, or the recording of subjective complaints. No pediatric-specific tool was available to measure this construct in children, which may account for the higher rate as items may have been misunderstood. Improving the measurement of perceived ankle instability in children would allow for any discrepancies due to questionnaire misinterpretation to be eliminated.

Alternatively, the experiences of adults compared to children with CAI may differ depending on the age of the first ankle sprain encountered and the onset of CAI. The age of the first ankle sprain endured by adults is rarely reported in the literature. Hence, it is unknown if adults with long-term symptoms of perceived instability incurred their first sprain as a child or as an adult. The lower prevalence of perceived instability observed in adults might be unique to this older age group if their first ankle sprain leading to CAI was recent, during adulthood.

The prevalence of mechanical instability was reported to be as high as 47% in children who were dancers using the anterior drawer test [17] and in 42% of children using stress x-ray [19]. In previous reports, 25% of adults who had experienced lateral ankle sprain within six months prior to the study were found to be ‘moderately lax’ with an anterior drawer test [28]. The higher occurrence of mechanical instability in dancers may be due to the increased general joint laxity in this population [29].

Prevalence of recurrent sprain was high across most groups of children and adolescents studied. Medical and self-reports highlighted that in up to 100% of participants who experienced an ankle injury, it was a re-injury to the joint [26]. This is higher than reports in adult research, where the incidence of re-sprain following an acute ankle sprain was as high as 34% [27]. Increased prevalence in children may be reflective of the specific active populations studied in the review, such as dancers and soccer players. Ankle sprain is commonly experienced, accounting for up to 37% of injuries in children’s soccer [23]. Therefore, this high prevalence in children of specific sporting groups may not reflect the true prevalence across all children and activity levels, perhaps making the prevalence rate more comparable to that of adults.

It was observed in the literature that like adults, children with a previous ankle injury such as ankle sprain are more likely to injure their ankles compared to those with no history of injury [17,21-23]. Up to 52% of adults with recurrent sprain have problems lasting longer than 10 years [7]. As a result of recurrent injury, up to 73% of adults with recurrent sprain injuries suffer from symptoms of pain, with 77% experiencing weakness [7]. The high prevalence of recurrent ankle sprain in children is therefore of particular concern. Following moderate to severe ankle injury, such as ankle sprain, children under the age of 10 years have been shown to be more likely to develop long-term symptoms than children over 10 years of age [20]. With such symptoms induced so early in life, and the impact of these symptoms on activity levels and quality of life, recurrent sprain poses a threat to the health and wellbeing of children as they grow and develop.

The review demonstrated that children commonly show signs and symptoms of the multiple components of CAI. An analysis of additional, unpublished data collected as part of a study by Hiller et al.[17] showed that an increased number of ankle sprains and increased laxity were found to be significantly associated with decreased CAIT scores (indicating greater instability). This finding highlights a relationship between perceived and mechanical aspects of ankle instability in addition to recurrent sprain [30]. However, while mechanical and perceived ankle instability, along with recurrent sprain may be linked, it is not necessary to experience symptoms across all of these domains. Hollwarth et al. [19] found that the absence of mechanical instability did not necessarily prevent the experience of perceived instability. These findings may be attributed to the initial trauma to the ankle in participants causing deficits in balance, strength, proprioception and joint position sense; leading to the experience of perceived instability without showing signs of mechanical instability [2].

To measure components of CAI, adult tools were often utilised including the CAIT and FAOS. No tool was found that had been developed or validated specifically for pediatric use to measure domains of CAI. Whilst adult tools may be appropriate to measure mechanical instability and recurrent sprain, they might be inappropriate to measure perceived instability. Due to the reflective nature of the construct, measurement is by self-report of complaints. Hence, questionnaires must be carefully developed and tested for their readability and comprehension by children to gain true insight into the perception of their ankle functioning. The Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool was recently modified to create the CAIT-Youth (CAITY) for use with a pediatric population [31]. The CAITY was developed and validated in children aged eight to sixteen years to measure perceived ankle instability. We recommend the use of this tool in future studies as a measurement tool for ankle instability in children [31].

A limitation of this review was that many papers that did investigate CAI were excluded due to the grouping of the results of children and adults together. Therefore, more information on CAI in children may be available than could be extracted for review due to the inclusion criteria of utilised for the present study.

Future research with a focus on CAI in the general pediatric community is recommended, in addition to specific sporting, clinical or post-injury populations. This may reveal the true incidence of CAI in children irrespective of physical activity, BMI and history of severe injury.

Conclusion

The prevalence of CAI was high in specific groups of children and adolescents studied, comparable and often higher to that of adult populations. However, this systematic review found a limited volume of research about CAI in children. As no tool of high quality existed to measure perceptual components of CAI in children, the prevalence, distribution and impact of CAI on children was difficult to determine. Future research into CAI in children is recommended to bridge this gap between clinical knowledge and evidence in the literature.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MM participated in the conception and design of the study, the collection, selection and review of papers and drafted the final manuscript. FP and AS were involved in the screening, selection and review of papers. JB was involved in the conception and design of the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. CH was involved in the conception and design of the study, reviewing the papers and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Melissa Mandarakas, Email: Melissa.Mandarakas@sydney.edu.au.

Fereshteh Pourkazemi, Email: fpou5046@uni.sydney.edu.au.

Amy Sman, Email: Amy.Sman@sydney.edu.au.

Joshua Burns, Email: Joshua.Burns@health.nsw.gov.au.

Claire E Hiller, Email: Claire.Hiller@sydney.edu.au.

Acknowledgements

MM was supported by an Honours Fellowship from the Faculty of Health Sciences, The University of Sydney. FP is supported by International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (IPRS) and an International Postgraduate Award (IPA) from University of Sydney. JB is supported by grants from the NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Fellowship #1007569 and Centre of Research Excellence #1031893), NIH (National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Office of Rare Diseases, #U54NS065712), Muscular Dystrophy Association, CMT Association of Australia, Australian Podiatry Education and Research Foundation.

We thank Dr. Markus Huebscher for his time and assistance in the translation of a paper included in our systematic review.

References

- Hiller CE, Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM. Chronic ankle instability: evolution of the model. J Athl Train. 2011;46:133–141. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahunt E. Neuromuscular contributions to functional instability of the ankle joint. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2007;11:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2007.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp H. Commentary: functional ankle instability revisited. J Athl Train. 2002;37:512–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel J. Functional anatomy, pathomechanics, and pathophysiology of lateral ankle instability. J Athl Train. 2002;37:364–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems T, Witvrouw E, Verstuyft J, Clercq DD. Proprioception and muscle strength in subjects with a history of ankle sprains and chronic instability. J Athl Train. 2002;37:487–493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konradsen L, Bech L, Ehrenbjerg M, Nickelsen T. Seven years follow-up after ankle inversion trauma. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002;12:129–135. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2002.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller CE, Nightingale EJ, Raymond J, Kilbreath SL, Burns J, Black DA, Refshauge KM. Prevalence and impact of chronic musculoskeletal ankle disorders in the community. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;20:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen RAW, Keizer G, Dijk CN. Long-term follow-up of inversion trauma of the ankle. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1995;114:92–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00422833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerin F, Delahunt E. Physiotherapists’ understanding of functional and mechanical insufficiencies contributing to chronic ankle instability. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2011;3:125–130. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20101029-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf JM, Cameron KL, Owens BD. Impact of joint laxity and hypermobility onthe musculoskeletal system. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:463–471. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201108000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Ryan MM, Ouvrier RA. Quality of life in children with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Child Neurol. 2010;25:343–347. doi: 10.1177/0883073809339877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinci P, Perelli SL. Footdrop, foot rotation, and plantarflexor failure in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:513–516. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.31174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Raymond J, Ouvrier R. Feasibility of foot and ankle strength training in childhood Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19:818–821. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller CE, Refshauge KM, Bundy AC, Herbert RD, Kilbreath SL. The Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool: a report of validity and reliability testing. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C, Doll H, Davies N, Wainwright A, Theologis T, Willett K, Fitzpatrick R. The Oxford Ankle Foot Questionnaire for children: responsiveness and longitudincal validity. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(10):1367–1376. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krips R, van Dijk CN, Halasi T, Lehtonen H, Moyen B, Lanzetta A, Farkas T, Karlsson J. Anatomical reconstruction versus tenodesis for the treatment of chronic anterolateral instability of the ankle joint: a 2- to 10-year follow-up, multicenter study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(3):173–179. doi: 10.1007/s001670050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller CE, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Kilbreath SL. Intrinsic predictors of lateral ankle sprain in adolescent dancers: a prospective cohort study. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18:44–48. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31815f2b35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollwarth M, Linhart WE, Wildburger R, Schimpl G. Spätfolgen nach supinationstrauma des kindlichen sprunggelenkes [Instability after distortion of the ankle joint in children] Unfallchirurg. 1985;88:231–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi AG, Di Bello D, Messi G, Gazzola G. Permanent sequelae in sports injuries: a population based study. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:324–328. doi: 10.1136/adc.81.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderman K, Adolphson J, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Injuries in adolescent female players in European football: a prospective study over one outdoor soccer season. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;11:299–304. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2001.110508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen K, Myklebust G, Andersen TE, Holme I, Bahr R. Self-reported injury history and lower limb function as risk factors for injuries in female youth soccer. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:700–708. doi: 10.1177/0363546507311598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson DM, Yard EE, Fields SK, Comstock RD. Patterns of recurrent injuries among US high school athletes, 2005–2008. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1586–1593. doi: 10.1177/0363546509332500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timm NL, Grupp-Phelan J, Ho ML. Chronic ankle morbidity in obese children following an acute ankle injury. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:33–36. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TF, McHugh MP, Mirabella MR, Mullaney MJ, Nicholas SJ. Risk factors for noncontact ankle sprains in high school football players: the role of previous ankle sprains and body mass index. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:471–475. doi: 10.1177/0363546505280429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir MA, Watson AWS. A twelve month study of sports injuries in one Irish school. Ir J Med Sci. 1996;165:165–169. doi: 10.1007/BF02940243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijn RM, Os AG, Bernsen RMD, Luijsterburg PA, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. What is the clinical course of acute ankle sprains? A systematic literature review. Am J Med. 2008;121:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denegar CR, Hertel J, Fonseca J. The effect of lateral ankle sprain on dorsiflexion range of motion, posterior talar glide, and joint laxity. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32:166–173. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2002.32.4.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon LM, Bird HA. The quantification of joint laxity in dancers and gymnasts. J Sport Sci. 2010;17(9):743–750. doi: 10.1080/026404199365605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard TJ, Cordova M. Mechanical instability after an acute lateral ankle sprain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1142–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandarakas M, Hiller CE, Rose KJ, Burns J. Measuring ankle instability in pediatric Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:1456–1462. doi: 10.1177/0883073813488676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]