Abstract

Objectives

This study compared the thermal, physiological and perceptual responses associated with match-play tennis in HOT (∼34°C wet-bulb-globe temperature (WBGT)) and COOL (∼19°C WBGT) conditions, along with the accompanying alterations in match characteristics.

Methods

12 male tennis players undertook two matches for an effective playing time (ie, ball in play) of 20 min, corresponding to ∼119 and ∼102 min of play in HOT and COOL conditions, respectively. Rectal and skin temperatures, heart rate, subjective ratings of thermal comfort, thermal sensation and perceived exertion were recorded, along with match characteristics.

Results

End-match rectal temperature increased to a greater extent in the HOT (∼39.4°C) compared with the COOL (∼38.7°C) condition (p<0.05). Thigh skin temperature was higher throughout the HOT match (p<0.001). Heart rate, thermal comfort, thermal sensation and perceived exertion were also higher during the HOT match (p<0.001). Total playing time was longer in the HOT compared with the COOL match (p<0.05). Point duration (∼7.1 s) was similar between conditions, while the time between points was ∼10 s longer in the HOT relative to the COOL match (p<0.05). This led to a ∼3.4% lower effective playing percentage in the heat (p<0.05). Although several thermal, physiological and perceptual variables were individually correlated to the adjustments in time between points and effective playing percentage, thermal sensation was the only predictor variable associated with both adjustments (p<0.005).

Conclusions

These adjustments in match-play tennis characteristics under severe heat stress appear to represent a behavioural strategy adopted to minimise or offset the sensation of environmental conditions being rated as difficult.

Keywords: Fatigue, Thermoregulation

Introduction

The development of hyperthermia during exercise in the heat, a state in which body core temperature (Tc) exceeds 38.5°C, is directly related to relative exercise intensity1 and the prevailing environmental conditions.2 Such increases in Tc under heat stress have been shown to impair prolonged continuous3 4 and intermittent exercise performance.5 6 The rise in thermal strain in hot conditions is also associated with elevated physiological and perceptual strain compared with exercise performed in cooler conditions,3 7 and can lead to heat-related illnesses (eg, heat exhaustion and heat stroke).8

Owing to the nature of the game, tennis is characterised as high-intensity intermittent exercise; however, its overall metabolic response is similar to prolonged moderate-intensity exercise (eg, running and cycling).9 This stems from work periods performed at 60–75% of maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), interspersed with periods of light activity or rest (ie, work-to-rest ratios of 1:2 to 1:5).10–14 Consequently, the mean relative exercise intensity for a match is ∼55% VO2max11 15 16 and duration is from 1 to 6 h.10–13 The overall energetic demands of match-play tennis and the rate of rise in Tc are therefore strongly influenced by point duration, as longer rallies result in greater metabolic loads.11 17

The development of hyperthermia during tennis is of particular concern when tournaments are played in hot environments, such as the Australian and US Opens when air temperature can exceed 40°C and the wet-bulb-globe temperature (WBGT) surpass 30°C.18 The WBGT is an index that provides an estimate of the thermal load an environment imposes based on ambient temperature, humidity, wind speed and solar radiation.19 A WBGT >28°C is considered as an extreme risk for thermal injury.20 Interestingly, several studies have observed that mean Tc increases safely to ∼38.5°C during tennis matches undertaken within a wide range of WBGTs (13.5–29.2°C).17 21–25 Under these circumstances, it appears that the intermittent nature of tennis allows for autonomic and behavioural thermoregulatory responses to successfully regulate Tc. Indeed, it has been postulated that a hyperthermia-induced increase in perceptual strain leads to a reduction in point duration and effective playing percentage (ie, the time spent with the ball in play relative to total time), which decreases overall workload and metabolic heat production.25 However, Tc ≥39.5°C have been reported in certain individuals,16 17 24 25 likely during play in particularly hot conditions. The attainment of this level of hyperthermia has been identified as a common challenge to sustained performance proficiency during competitive match-play tennis26 and may bring about health consequences. As such, understanding the degree to which hyperthermia develops during match-play tennis in the heat and how behavioural responses influence its development, as well as match characteristics, has the potential to impact on playing guidelines to ensure player safety (eg, duration of time between points, games and sets) at the professional level27 as well as with amateurs. This may not only contribute to minimise exertional heat illness risk, but also enhance the strategies used to manage recovery between matches in a tournament format.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct a direct comparison of matches undertaken in HOT (WBGT>30°C) and COOL (WBGT<20°C) conditions to determine whether autonomic (ie, sweat rate) and behavioural (ie, match characteristics) thermoregulatory responses successfully regulate Tc. It was hypothesised that the development of hyperthermia during play in the heat would reduce point duration and effective playing percentage as part of a behavioural response to regulate the increase in thermal, physiological and perceptual strain.

Methods

Subjects

Twelve male players, unacclimatised to heat, with an International Tennis Federation (ITF) number of 1–3 participated in the study. Mean age, height, body mass, weekly training volume and years of practice were 22±4 years, 183.5±7.7 cm, 80.8±9.5 kg, 13±6 h/week and 16±4 years, respectively. They played an average of 17±10 tournaments and 65±23 matches/year. Participants were informed of the study aims, requirements and risks before providing written informed consent.

Study design

The participants played two counter-balanced simulated matches on hard-court surfaces separated by 72 or 144 h. They were paired according to the level of play and competed against the same opponent in both matches. One match was played indoors in temperate conditions (COOL: 21.8±0.1°C, 72.3±3.2% relative humidity, 19.4±0.3°C WBGT) and the other outside in hot conditions (HOT: 36.8±1.5°C, 36.1±11.3% relative humidity, 33.6±0.9°C WBGT). Wind velocity during the HOT matches was 0.7±0.2 m/s. The matches were of typical length (COOL: 102.1±19.0 min and HOT: 119.2±9.6 min); however, data were analysed as a function of effective playing time. More specifically, matches were separated in 2×10 min segments of effective play. To calculate the effective playing time, each rally duration was measured from the start (ie, ball leaving the hand of the serving player) to the end (ie, ball passing the player or bouncing twice) of the rally and summed until the total duration reached 10 min. This approach was chosen to ensure that outcome measures were compared after an equivalent effective playing time (eg, 2.5 min) in both conditions. Each 10 min of effective play was separated by ∼25 min to conduct body mass, blood lactate (see below) and physical performance measurements.28

Experimental protocol

On arrival on match days (9:00), participants provided a urine sample for the measurement of urine-specific gravity (USG; Pal-10-S, Vitech Scientific Ltd, West Sussex, UK) and inserted a telemetric temperature pill in the rectum for measuring Tc. Their height and body mass (Seca 769, Hamburg, Germany) were then taken before being instrumented in a temperate environment (∼22°C). Participants then performed a 5 min standardised warm-up (running at 9 km/h from baseline to baseline for 5 min) on an indoor court and a 10 min tennis-specific warm-up (rallies and serves) in the condition of play (ie, either remained indoors or proceeded to the outdoor court). After the warm-up, prematch body mass and perceptual measures were recorded, and a finger prick blood lactate (Lactate Pro, Arkray Global Business Inc, Kyoto, Japan) measurement was taken. An absorbent pad with protective dressing (Tegaderm + Pad, 3M Health Care, Borken, Germany) was placed at the level of the right scapula (after cleaning the skin with deionised water) to determine sweat sodium concentration (Dimension Xpand Plus, Siemens, Munich, Germany). After the first 10 min of effective play and at match completion, body mass and blood lactate were again measured. On the days when the participants did not play they followed a standardised training programme led by a tennis coach (∼60 min).

Thermal, physiological and perceptual measurements

The telemetric temperature pill (VitalSense, Mini Mitter, Respironics, Herrsching, Germany) used to monitor Tc was inserted the length of a gloved index finger beyond the anal sphincter. Owing to logistical issues, skin temperature (Tsk) was only monitored over the left thigh with a wireless dermal adhesive temperature patch (VitalSense, Mini Mitter, Respironics, Herrsching, Germany). Although thigh Tsk is not reflective of mean Tsk using multiple sites across the body, it is typically given a weighting of 9.5–32% in various mean Tsk formulas.29 As such, it was chosen to represent the heat stress imposed by the ambient conditions on the skin. Heart rate was monitored with the Polar Team system (Polar Electro, Lake Success, New York, USA). Temperatures, heart rate and perceptual measures (ie, thermal comfort,30 thermal sensation31 and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE)32) were recorded at 2.5 min intervals of effective playing time. The WBGT (QUESTemp°36, Quest Technologies, Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, USA) was recorded prematch, midmatch and postmatch. During both matches, participants consumed water and a commercially available sport drink (Gatorade, Chicago, Illinois, USA) ad libitum. They were also provided with bananas and granola bars (Nature Valley, General Mills, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). All participants kept a food diary to record the amount of food consumed at each meal, which were prepared for them, in order to replicate their diet before the second match. Participants were instructed to eat and drink as they normally would during tournament play. All body mass (wearing only shorts) and sweat loss calculations (eg, sweat rate) were corrected for fluid consumption. Although the sweat rate calculation did not account for respiratory and gastrointestinal fluid losses, or the metabolic water produced during exercise, it does provide an indication of the autonomic thermoregulatory responses (ie, vasomotion and sweating) associated with maintaining thermal equilibrium.25

Match-play characteristics

The scoring and timing characteristics of the matches complied with the 2012 ITF Rules of Tennis.33 To ensure a continuous play, participants had the opportunity to rest for 20 s between points, 90 s between changeovers and 120 s between sets. A stopwatch was used to measure the duration of each point, starting with the ball toss of the serve and ending when the ball had bounced twice or passed the player. In case of a double fault, start time for the point was recorded from the beginning of the second serve. Aces and double faults were recorded and normalised to the number of points. Total playing time, point duration, between-point duration and effective playing percentage were also calculated. Three new tennis balls were used for each 10 min of effective play, with the players retrieving balls between points.

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using PASW software V.18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Repeated-measures analysis of variances were performed to test the significance between and within treatments. In case of a significant effect of time or interaction (time × condition), pairwise differences were identified using the Bonferroni post hoc analysis procedure adjusted for multiple comparisons. A linear mixed-model regression analysis was used to determine the factors (mean and peak rectal temperature, thermal comfort and sensation, RPE and heart rate) associated with the changes in match-play characteristics. This model was used to control for the fact that repeated observations are more likely to be correlated. The significance level was set at p<0.05. All values are expressed as means±SD.

Results

Temperature and physiological responses

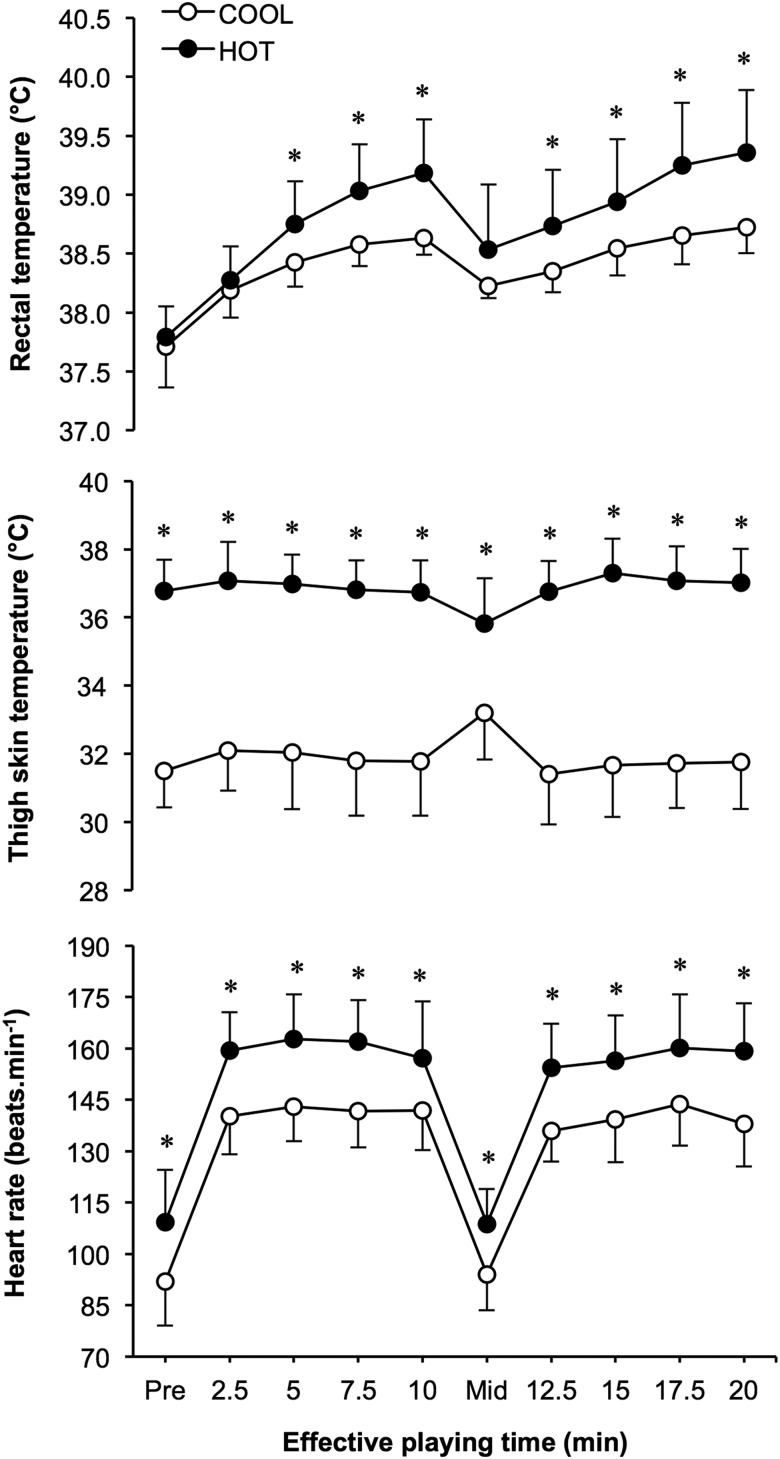

Tc increased significantly during each 10 min of effective play in the HOT and COOL matches (figure 1). The increase in Tc was greater in the HOT match peaking at 39.4±0.5°C compared with 38.7±0.2°C in the COOL match (p<0.05). Tsk was higher throughout the match in the HOT versus COOL conditions (p<0.001). In both conditions, heart rate increased during play compared with prematch and midmatch resting values (p<0.01). Heart rate was 18.5±11.3 bpm higher throughout play in the HOT condition, relative to the COOL condition (p<0.01). Blood lactate concentration was higher throughout the HOT condition (2.1±0.6, 2.9±0.8 and 2.6±0.6 mmol/L) compared with the COOL condition (1.8±0.6, 2.3±1.3 and 1.9±0.6 mmol/L; prematch, midmatch and postmatch, respectively; p<0.05). A significant increase in blood lactate concentration was observed from prematch to midmatch in both conditions (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Rectal temperature, thigh skin temperature and heart rate during 20 min of effective match-play tennis (2×10 min) in COOL and HOT conditions. *Significantly different from COOL, p<0.05.

Perceptual responses

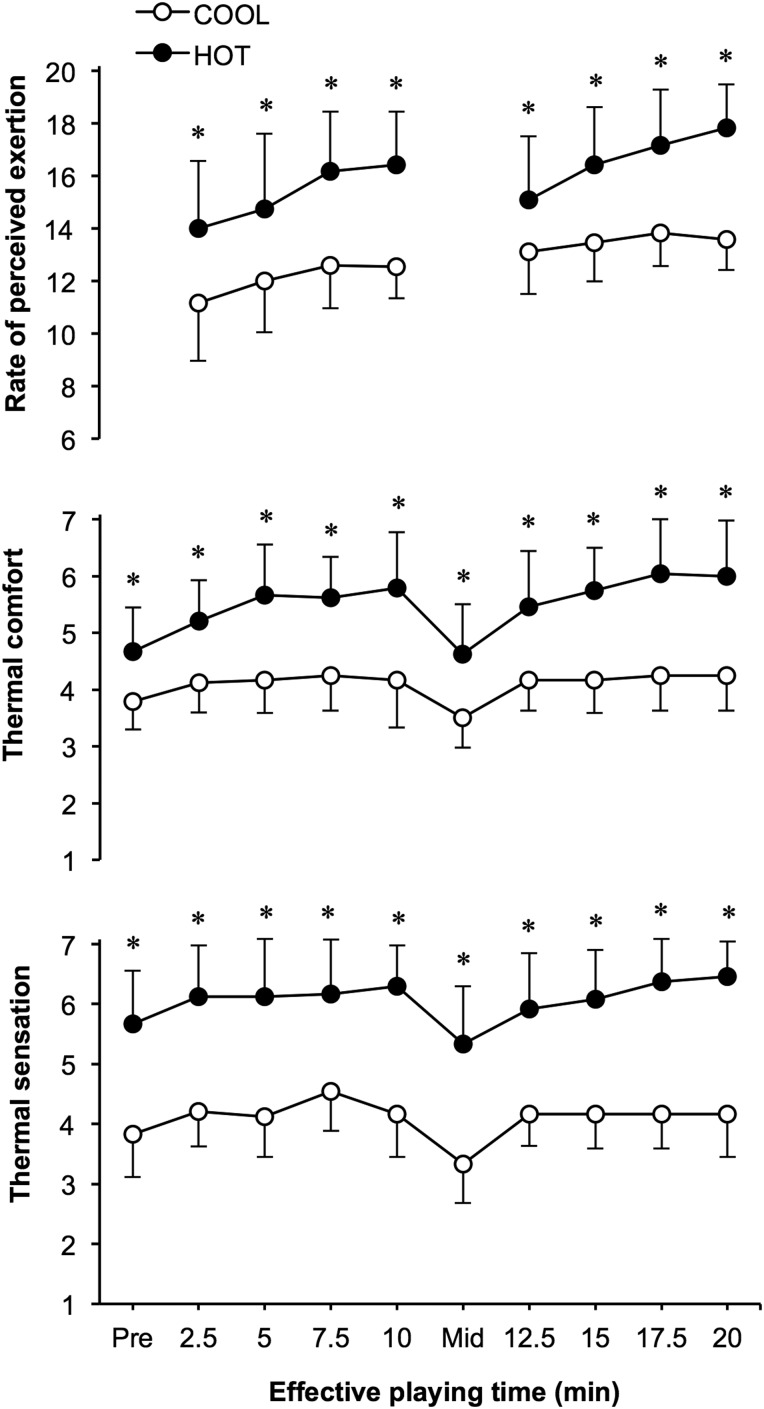

RPE increased during each 10 min of effective play in both conditions; however, it was higher in the heat (figure 2; p<0.01). Thermal comfort and thermal sensation ratings were also higher in the HOT compared with the COOL match (p<0.001). During the HOT match, thermal comfort rose throughout each 10 min of effective play (p<0.01), whereas it remained stable in the COOL.

Figure 2.

Ratings of perceived exertion (arbitrary units: 6–20), thermal comfort (arbitrary units: 1–7) and thermal sensation (arbitrary units: 1–7) during 20 min of effective match-play tennis (2×10 min) in COOL and HOT conditions. *Significantly different from the COOL condition, p<0.01.

Hydration responses

Prematch USG was similar between the HOT (1.020±0.009 g/mL) and COOL (1.021±0.008 g/mL) conditions. Sweat rate was greater in the HOT (1.6±0.4 L/h) compared with the COOL (0.9±0.2 L/h) condition (p<0.001); however, percentage body mass losses were similar during each match (HOT: −0.7±1.5% vs COOL: −0.4±0.4%). This is attributable to the additional fluids consumed by the participants in the HOT (2.0±0.6 L/h) compared with the COOL (1.2±0.4 L/h) condition (p<0.001). More specifically, the volume of water (2.6±0.9 vs 1.2±0.7 L) and Gatorade (1.6±0.7 vs 0.9±0.4 L) consumed was greater during the HOT compared with the COOL match (p<0.01), whereas the number of bananas (0.8±0.7 vs 0.6±0.8) and granola bars (0.9±1.2 vs 0.7±0.7) ingested was similar between conditions (HOT vs COOL, respectively). Accordingly, no differences in body mass were noted between or within conditions (table 1). Sweat sodium losses during the HOT (3005.1±925.9 mg/h) match were greater than in the COOL (1243.1±639.3 mg/h; p<0.001).

Table 1.

Body mass variations on match days

| Match | Measurement time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Morning | Prematch | Midmatch | Postmatch | |

| Body mass (kg) | COOL | 80.9±9.4 | 81.2±9.6 | 81.0±9.6 | 80.9±9.8 |

| HOT | 80.5±9.7 | 80.7±9.6 | 80.3±9.8 | 80.2±10.3 | |

No significant differences were observed, p>0.05.

Match-play characteristics

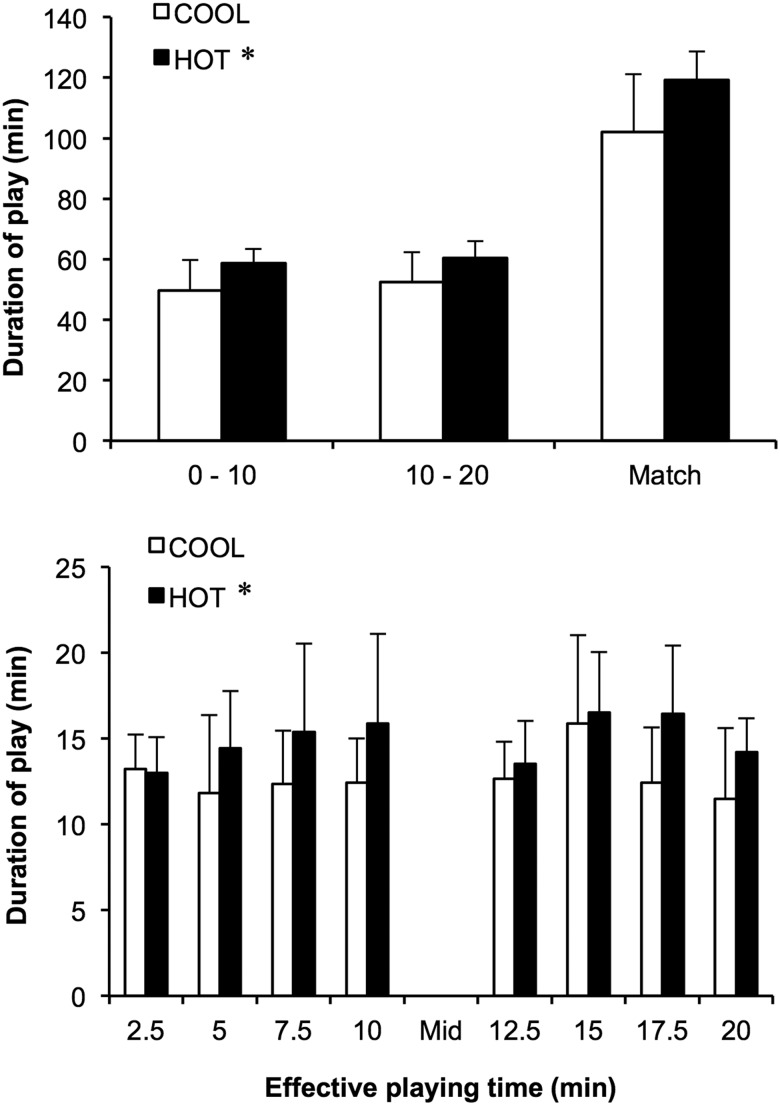

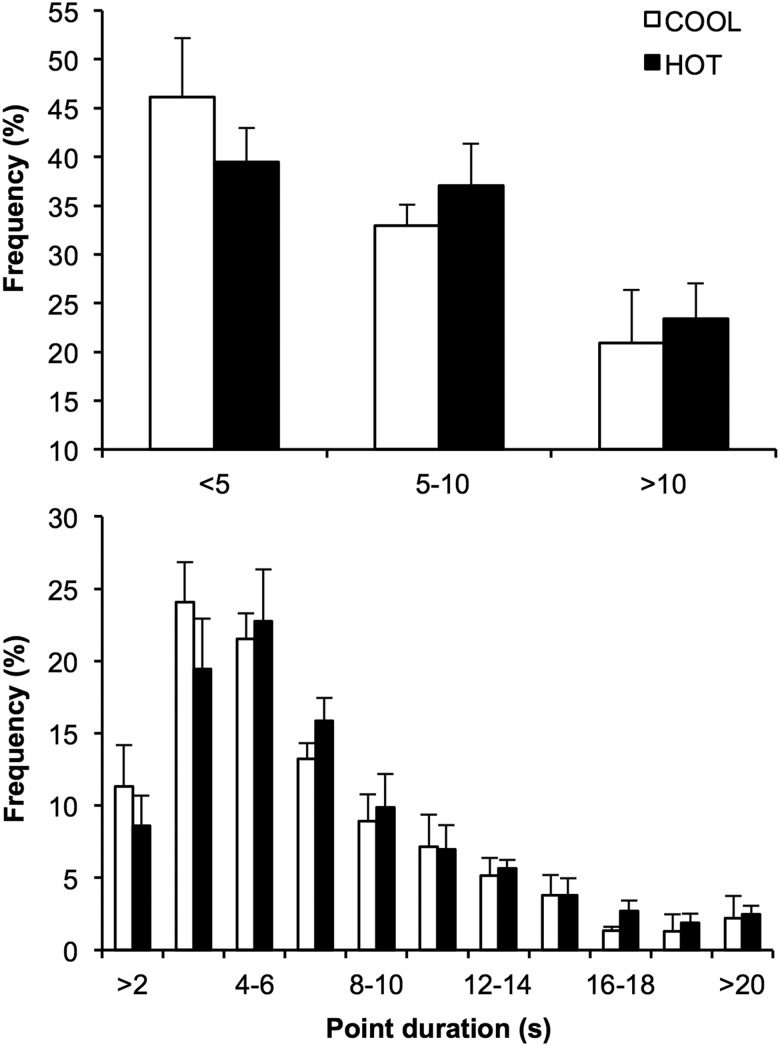

A longer mean time to complete the 2.5 and 10 min segments of effective play was observed in the HOT compared with the COOL condition (figure 3, p<0.05). As a result, total duration for the HOT match was 17.1±12.6 min longer than the COOL (p<0.05). Point duration was similar between matches (table 2). However, the time between points was significantly longer (9.6±3.6 s) in the HOT compared with the COOL match (p<0.01). This led to a 3.4±2.9% lower effective playing percentage in the HOT, relative to the COOL match (p<0.05). The number of games and points played did not differ between conditions, nor did the percentage of aces and double faults (table 3). Likewise, the frequency distribution of point duration did not differ between conditions (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Duration of playing time required to complete 20 min of effective match-play tennis (2×10 min) in COOL and HOT conditions. *Significant difference between play in the HOT and COOL conditions, p<0.05.

Table 2.

Point duration, time between points and effective playing percentage during 20 min of effective match-play tennis (2×10 min) in COOL and HOT conditions

| Match | Match | Effective playing time (min) | Match | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Condition | 0–10 | 10–20 | Mean |

| Point duration (s) | COOL | 7.1±1.7 | 6.6±1.2 | 6.8±1.4 |

| HOT | 7.4±0.8 | 7.5±1.1 | 7.4±0.5 | |

| Between point duration (s) | COOL | 17.3±4.0 | 18.6±5.0 | 18.0±4.2 |

| HOT | 27.2±4.2* | 27.9±4.0* | 27.6±2.8* | |

| Effective playing (%) | COOL | 20.9±4.7 | 19.6±3.5 | 20.3±4.0 |

| HOT | 17.1±1.4* | 16.7±1.5* | 16.9±1.4* | |

*Significantly different from COOL, p<0.05.

Table 3.

Match characteristics during 20 min of effective match-play tennis (2×10 min) in COOL and HOT conditions

| Match | Match | Effective playing time (min) | Match | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Condition | 0–10 | 10–20 | Total/mean |

| Number of points played | COOL | 91.0±23.0 | 94.7±17.0 | 185.7±38.7 |

| HOT | 83.7±10.6 | 82.8±11.0 | 166.5±10.5 | |

| Number of games played | COOL | 14.2±3.5 | 14.3±3.5 | 28.4±6.9 |

| HOT | 12.0±2.3 | 12.4±1.4 | 24.4±1.9 | |

| Aces (% of points) | COOL | 2.2±2.7 | 3.1±3.1 | 2.7±2.5 |

| HOT | 1.6±1.7 | 2.2±2.1 | 1.9±1.6 | |

| Double faults (% of points) | COOL | 2.6±1.8 | 2.1±1.2 | 2.4±1.3 |

| HOT | 2.8±2.4 | 1.8±1.8 | 2.3±1.5 | |

No significant differences were observed, p>0.05.

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution in percentage (%) of points within a 5 and 2 s range during 20 min of effective match-play tennis in COOL and HOT conditions.

Relationships between variables

Time between points was significantly correlated with mean Tc (r=0.327, p<0.012), peak Tc (r=0.340, p<0.009), as well as thermal comfort (r=0.638, p<0.001), thermal sensation (r=0.741, p<0.001), RPE (r=0.665, p<0.001) and HR (r=0.524, p<0.001) measures taken at the end of each 10 min of effective play. Effective playing percentage was correlated with peak Tc (r=−0.244, p<0.001), thermal comfort (r=−0.356, p<0.001), thermal sensation (r=−0.410, p<0.001) and RPE (r=−0.371, p<0.001). However, the linear mixed-model regression analysis revealed that thermal sensation was the only predictor variable associated with the increase in time between points (β=3.9±0.5, p<0.001) and the reduction in effective playing percentage (β=−0.9±0.2, p<0.001).

Discussion

This study provides the first direct comparison of the thermal, physiological and perceptual responses associated with match-play tennis in HOT and COOL conditions. It also highlights the adjustments in match characteristics that occur during the development of hyperthermia in high-level players under severe heat stress (WBGT ∼34°C). The major finding of the study is that a longer time between points, rather than a change in point duration, leads to a reduction in effective playing percentage during match-play tennis in the heat. This appears to represent a behavioural strategy adopted to minimise or offset increases in thermal, physiological and perceptual strain, in particular the sensation of environmental conditions being rated as difficult.

Thermoregulatory, physiological and perceptual responses

Our results indicate that mean Tc during play in the COOL condition was ∼38.5°C (figure 1). This observation is in agreement with previous studies examining the thermoregulatory responses of match-play tennis in various environmental conditions21 22 24 34 and during tournament play within an air temperature range of 14.5–43.1°C.16 17 25 However, we noted a much greater increase in mean Tc in the HOT condition, especially during the second 10 min of effective play (∼39.1°C). Interestingly, this Tc profile is similar to that of simulated soccer matches (2×45 min, 15 min half-time) conducted in HOT and COOL conditions.6 Of note, Tippet et al35 showed a Tc decrease of ∼0.25°C during a 10 min break in match-play tennis under severe heat stress (WBGT: 30.3°C). In the current study, Tc decreased by 0.4±0.1°C (COOL) and 0.7±0.1°C (HOT) during the 25 min rest/testing period between effective play segments. This suggests that greater increases in Tc could have occurred, had the break been shorter, despite 6 of 12 players reaching a final Tc >39.5°C.

The ∼0.6°C higher mean Tc noted in the HOT condition was accompanied by a significant elevation in Tsk relative to COOL conditions. As air temperature is the primary determinant of Tsk and of the thermal gradient for convective heat transfer, it strongly influences heat dissipation and thermal comfort/sensation. During match-play in the heat, air temperature was similar to that of the skin. As a result, heat dissipation via convection was reduced and sweat evaporation became the primary avenue for cooling. The increased reliance on evaporative heat loss afforded hydration a significant role in maintaining thermal homeostasis, as excessive dehydration is known to exacerbate hyperthermia.8 However, hydration behaviour during play in both conditions allowed for body mass losses to remain <1% (table 1), which is similar to values (0.5–1.5%) reported in the literature16 17 23–25 35 although not always the case (∼2.3%).36 In the HOT match, this response was likely associated with the acuteness and severity of the heat stress, as well as the increase in sweat rate, which triggered the reflex to drink (ie, >600 mL/h in the HOT than in the COOL condition). Thus, while high-intensity work-to-rest ratios can elicit large increments in core body temperature, they also allow the opportunity to replace fluid losses.37

Although the level of body mass loss incurred in the current study is unlikely to impair match-related performance, hyperthermia and fatigue may be exacerbated when play is undertaken in a hypohydrated state (USG >1.020).8 Emphasis should, therefore, be placed on the importance of prematch hydration.38 In the current study, prematch USG measures were similar in the HOT and COOL conditions (ie, borderline euhydrated), reflecting the typically poor hydration practices of tennis players.17 23 Given the increased sodium losses observed in the HOT match and the reported emphasis on glycolysis and glycogenolysis during match-play tennis15, specific hydration recommendations and strategies should also be provided to optimise the consumption of appropriate fluids during play. Notwithstanding, the physiological responses and adjustments in play observed in the current study do not appear to have originated from variations in hydration status, but rather from the level of heat stress imposed.

The progressive increase in Tc and sustained elevation in Tsk observed during play in the HOT match was accompanied by an elevated heart rate, which is characteristic of prolonged self-paced aerobic exercise in the heat.3 The higher heart rate in the heat is suggested to occur in response to a reflex rise in skin blood flow4 and an increase in relative exercise intensity, mediated by a hyperthermia-induced reduction in VO2max.3 4 As match-play tennis becomes protracted and thermal strain develops, a reduction in VO2max may result in the progressive increase of relative exercise intensity during long rallies, requiring lengthier recovery periods between points. This may partly explain the extended time between points, as well as the elevated heart rate, RPE and higher blood lactate concentrations observed in the heat, although the blood lactate values recorded in both conditions were within the range observed for prolonged match-play tennis.11 14 15 Moreover, absolute and relative (COOL: ∼71% and HOT: ∼80% of predicted maximum) heart rate, as well as RPE, were typical of those observed during singles match-play tennis,14 which indicates that the matches were competitively disputed, regardless of climatic conditions.

Correspondingly, subjective ratings of thermal comfort and sensation were higher during the match in the heat (figure 2). This is a well-documented response, which is associated with the overall rise in thermal strain.3 25 From a behavioural perspective, a subjective increase in the rating of thermal comfort and sensation during match-play is purported to modulate adjustments in work rate to minimise discomfort and maintain Tc within safe levels.25 However, in the present ambient conditions, we observed a continuous rise in Tc, well above 39.5°C in certain participants. Although trained individuals can tolerate large increases in Tc,39 40 careful monitoring is warranted during prolonged matches undertaken under extreme heat to ensure player safety.

Match-play characteristics

Typically, match duration (80–120 min), point duration (6–10 s) and between-point duration (17–25 s), as well as effective playing percentage (17–28%) and work-to-rest ratios (1:2 to 1:5), fall within a certain range during actual and simulated three set matches14 17 26 41; although a variety of factors can influence the extent of those responses.14 In the current study, these responses were similar to those reported in the literature, although total match duration was increased during play in the HOT compared with the COOL condition (figure 3). In addition, effective playing percentage was reduced in the HOT match, due to a significant increase in the duration of time between points (table 2). As a result, the work-to-rest ratio increased from 1:3 (COOL) to 1:4 (HOT). These adjustments occurred in response to the rise in thermal, physiological and perceptual strain, as indicated by individual correlations. However, the only predictor variable associated with changes in match characteristics to emerge from the linear mixed-model regression analysis was thermal sensation. Thus, it appears that in conjunction with the development of fatigue,34 42 43 afferent feedback regarding the thermal environment contributed to increase the duration of time between points (eg, greater ball retrieval and service preparation time), leading to reductions in effective playing percentage.

Morante and Brotherhood25 first suggested that behavioural thermoregulation occurs during match-play tennis when the environmental conditions are rated as uncomfortably hot (ie, high rating of thermal sensation), whereby effective playing percentage is reduced. However, they proposed that a decrease in point duration, rather than an increase in the rest interval between points, achieved this reduction. Although point duration was unaffected in the current study, both these strategies (ie, reducing point duration and increasing the time between points) appear to represent mechanisms by which players behaviourally decrease their workload and concomitantly the production of metabolic heat. Interestingly, it is proposed that behavioural thermoregulation is driven by thermal discomfort and that thermal sensation initiates autonomic thermoregulatory responses.44 However, our data provide support for Morante and Brotherhood25 in that dissatisfaction with the environmental conditions appears to have instigated the behavioural adjustments. Accordingly, behavioural thermoregulation appears to represent a primary mechanism triggering conscious decisions to preserve thermal homeostasis.45

Pespectives

As per the rules and regulations of the ITF,32 participants were encouraged to rest for 20 s between each point throughout both matches. However, the combination of having to retrieve their own balls and the development of hyperthermia during the HOT match appears to have increased the duration of time between points to ∼27.5 s. While it may be argued that this result does not accurately reflect competitive tournament play at the international level13 where balls are retrieved by designated individuals and time between points is more strictly regulated, such extended recovery durations between points when competing in the heat is not novel. Indeed, Hornery et al17 demonstrated that during an international tournament, the time between points during matches undertaken in ∼40°C was ∼25 s. The authors also reported similar match (119 min) and point (6.7 s) durations, peak Tc (38.9°C), sweat rates (2.0 L/min), body mass deficits (1.1%) and average heart rates (152 bpm) to those measured in the current study. In combination with our findings, these observations highlight the importance of allowing players the opportunity to self-regulate their effort through slightly protracted rest intervals between points, without affecting the continuity of play, to ensure their safety and avoid heat-related injuries. Moreover, enforcing the Extreme Weather Condition rule whereby a 10 min break is allowed between the second and third sets in tournament play, not only at the professional level27 but for amateurs as well, may further reduce the risk of heat injury and encourage optimal performance. Future research should examine match characteristics more closely to determine whether increasing point duration and/or increasing between-point duration during play in the heat are behavioural strategies regularly adopted by players of all levels, age groups and gender.

Conclusions

In contrast to match-play tennis in cool conditions, mean body Tc increases progressively more during play in the heat, while Tsk remains elevated. This rise in thermal strain results in a sustained elevation in heart rate and exacerbated perception of effort, thermal comfort and thermal sensation. Consequently, effective playing percentage is reduced as the duration of time between points increases. These adjustments appear to represent a behavioural strategy adopted to minimise or offset the sensation of environmental conditions being rated as difficult.

What are the new findings?

Whole-body hyperthermia is exacerbated during match-play tennis in hot compared with cool conditions, which increases heart rate, perceived exertion, thermal comfort and thermal sensation.

The increase in thermal, physiological and perceptual strain results in a reduction of effective playing percentage, due to an increase in the duration of time between points.

Adjustments in match-play characteristics appear to represent a behavioural strategy adopted to minimise or offset the sensation of environmental conditions being rated as difficult.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the near future?

The development of hyperthermia during exercise in hot climatic conditions can lead to heat-related illnesses such as heat exhaustion and heat stroke.

Allowing tennis players the opportunity to self-regulate their effort through slightly protracted rest intervals between points and games, without affecting the continuity of play, may help ensure their health and safety by preventing heat-related injuries.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their participation in this study. They also thank the coaches, Tim Colijn and Samuel Rota, for conducting the practises during the days between matches.

Footnotes

Contributors: JDP, OG, SR, CPH, WLK and RJC contributed to the development of the project. JDP, SR and OG collected and analysed the data. JDP, OG, SR, CPH, WLK and RJC had intellectual input in drafting the manuscript. All authors gave the final approval for submitting the manuscript.

Funding: This project was funded by the Aspire Zone Foundation Research Grant.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Shafallah Medical Genetics Center Ethical Research Committee and conformed to the current Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Saltin B, Hermansen L. Esophageal, rectal, and muscle temperature during exercise. J Appl Physiol 1966;21:1757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lind AR. A physiological criterion for setting thermal environmental limits for everyday work. J Appl Physiol 1964;18:51–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Périard JD, Cramer MN, Chapman PG, et al. Cardiovascular strain impairs prolonged self-paced exercise in the heat. Exp Physiol 2011;96:134–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowell LB. Human cardiovascular adjustments to exercise and thermal stress. Physiol Rev 1974;54:75–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozgünen KT, Kurdak SS, Maughan RJ, et al. Effect of hot environmental conditions on physical activity patterns and temperature response of football players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20:140–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohr M, Nybo L, Grantham J, et al. Physiological responses and physical performance during football in the heat. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e39202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nybo L, Nielsen B. Perceived exertion is associated with an altered brain activity during exercise with progressive hyperthermia. J Appl Physiol 2001;91:2017–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:377–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergeron MF, Maresh CM, Kraemer WJ, et al. Tennis: a physiological profile during match play. Int J Sports Med 1991;12:474–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christmass MA, Richmond SE, Cable NT, et al. Exercise intensity and metabolic response in singles tennis. J Sports Sci 1998;16:739–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smekal G, Duvillard von SP, Rihacek C, et al. A physiological profile of tennis match play. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33:999–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacs MS. A comparison of work/rest intervals in men's professional tennis. Med Sci Tennis 2004;9:10–11 [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Donoghue P, Ingram B. A notational analysis of elite tennis strategy. J Sport Sci 2001:19:107–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez J, Mendez-Villanueva A, Pluim BM. Intensity of tennis match play. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:387–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrauti A, Bergeron MF, Pluim BM, et al. Physiological responses in tennis and running with similar oxygen uptake. Eur J Appl Physiol 2001;85:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morante SM, Brotherhood JR. Air temperature and physiological and subjective responses during competitive singles tennis. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:773–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornery DJ, Farrow D, Mujika I, et al. An integrated physiological and performance profile of professional tennis. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:531–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mountjoy M, Alonso JM, Bergeron MF, et al. Hyperthermic-related challenges in aquatics, athletics, football, tennis and triathlon. Br J Sports Med 2012; 46:800–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergeron MF, Bahr R, Bärtsch P, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on thermoregulatory and altitude challenges for the high-level athlete. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:770–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binkley HM, Beckett J, Casa DJ, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: exertional heat illnesses. J Athl Train 2002; 37:329–43 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott B, Dawson B, Pyke F. The energetics of singles tennis. J Hum Mov Stud 1985;11:11–20 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therminarias A, Dansou P, Chirpaz-Oddou MF, et al. Hormonal and metabolic changes during a strenuous tennis match. Effect of ageing. Int J Sports Med 1991;12:10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergeron MF, Waller JL, Marinik EL. Voluntary fluid intake and core temperature responses in adolescent tennis players: sports beverage versus water. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:406–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergeron MF, McLeod KS, Coyle JF. Core body temperature during competition in the heat: national boys’ 14s junior tennis championships. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:779–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morante SM, Brotherhood JR. Autonomic and behavioural thermoregulation in tennis. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:679–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornery DJ, Farrow D, Mujika I, et al. Fatigue in tennis: mechanisms of fatigue and effect on performance. Sports Med 2007;37:199–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Tennis Federation. ITF L. ITF pro circuit regulations. 2012:1–148 http://www.itftennis.com [Google Scholar]

- 28.Girard O, Christian RJ, Racinais S, et al. Heat stress does not exacerbate tennis-induced alterations in athletic performance. Br J Sports Med 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons KC. Human thermal environments: the effect of hot, moderate and cold environments on human health, comfort and performance. 2nd edn New York: Taylor & Francis, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bedford T. The warmth factor in comfort at work: a physiological study of heating and ventilation. Industrial Health Research Board; 1936, Report No. 76 [Google Scholar]

- 31.ASHRAE. Thermal comfort conditions. New York: ASHRAE standard, 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982;14:377–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.International Tennis Federation. International Tennis Federation Rules of Tennis 2012. 2012. http://www.itftennis.com, http://www.itftennis.com/media/107013/107013.pdf (accessed 9 Jul 2013).

- 34.Dawson B, Elliott B, Pyke F, et al. Physiological and performance responses to playing tennis in a cool environment and similar intervalized treadmill running in a hot climate. J Hum Mov Stud 1985;11:21–34 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tippet ML, Stofan JR, Lacambra M, et al. Core temperature and sweat responses in professional women's tennis players during tournament play in the heat. J Athl Train 2011;46:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarthy PR, Thorpe RD, Williams C. Body fluid loss during competitive tennis match-play. In: Lees A, Maynard I, Hughes M, et al. eds Science and racket sports II. London: E & FN Spon, 1998:52–5 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovacs MS. Hydration and temperature in tennis—a practical review. J Sports Sci Med 2006;5:1–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovacs MS. A review of fluid and hydration in competitive tennis. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2008;3:413–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheung SS, McLellan TM. Heat acclimation, aerobic fitness, and hydration effects on tolerance during uncompensable heat stress. J Appl Physiol 1998; 84:1731–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Périard JD, Caillaud C, Thompson MW. The role of aerobic fitness and exercise intensity on endurance performance in uncompensable heat stress conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol 2012;112:1989–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torres-Luque G, Sánchez-Pay A, Bazaco MJ, et al. Functional aspects of competitive tennis. J Hum Sport Exerc 2011;6:528–39 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Girard O, Lattier G, Micallef JP, et al. Changes in exercise characteristics, maximal voluntary contraction, and explosive strength during prolonged tennis playing. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:521–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Girard O, Lattier G, Maffiuletti NA, et al. Neuromuscular fatigue during a prolonged intermittent exercise: application to tennis. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2008;18:1038–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gagge AP, Stolwijk JA, Hardy JD. Comfort and thermal sensations and associated physiological responses at various ambient temperatures. Environ Res 1967;1:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Attia M. Thermal pleasantness and temperature regulation in man. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1984;8:335–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]