Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a commonly reported cause of death and associated with smoking. However, COPD mortality is high in poor countries with low smoking rates. Spirometric restriction predicts mortality better than airflow obstruction, suggesting that the prevalence of restriction could explain mortality rates attributed to COPD. We have studied associations between mortality from COPD and low lung function, and between both lung function and death rates and cigarette consumption and gross national income per capita (GNI).

Methods

National COPD mortality rates were regressed against the prevalence of airflow obstruction and spirometric restriction in 22 Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study sites and against GNI, and national smoking prevalence. The prevalence of airflow obstruction and spirometric restriction in the BOLD sites were regressed against GNI and mean pack years smoked.

Results

National COPD mortality rates were more strongly associated with spirometric restriction in the BOLD sites (<60 years: men rs=0.73, p=0.0001; women rs=0.90, p<0.0001; 60+ years: men rs=0.63, p=0.0022; women rs=0.37, p=0.1) than obstruction (<60 years: men rs=0.28, p=0.20; women rs=0.17, p<0.46; 60+ years: men rs=0.28, p=0.23; women rs=0.22, p=0.33). Obstruction increased with mean pack years smoked, but COPD mortality fell with increased cigarette consumption and rose rapidly as GNI fell below US$15 000. Prevalence of restriction was not associated with smoking but also increased rapidly as GNI fell below US$15 000.

Conclusions

Smoking remains the single most important cause of obstruction but a high prevalence of restriction associated with poverty could explain the high ‘COPD’ mortality in poor countries.

Keywords: COPD epidemiology, Tobacco and the lung, Lung Physiology

Key messages.

What is the key question?

What is the relation between the global distribution of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) mortality, the prevalence of abnormal lung function, smoking and poverty?

What is the bottom line?

Smoking prevalence correlates with airflow obstruction, but not with mortality from COPD; COPD mortality is associated with low vital capacity; COPD mortality and low vital capacity are associated with poverty.

Why read on?

Between 1990 and 2010, COPD rose from the fourth to the third most common cause of death globally. Adequate understanding of the distribution of COPD mortality is the key to finding an adequate response.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is now the third most common cause of death in the world.1 COPD is defined in terms of airflow obstruction and operationalised as a low ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC).2 By far the strongest risk factors for airflow obstruction are smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke,3but many areas of the world with high mortality rates from ‘COPD’ still have low consumption of tobacco.4 The distribution of death from COPD in the UK is not the same as that of lung cancer, the disease most strongly associated with tobacco consumption, but is more closely associated with low social status5 and poverty.6

A low FEV1 is associated with increased mortality, including a high mortality from cardiovascular disease,7 but there is also evidence of an association with a low FVC, a measure correlated with the FEV1.8 9 When these two measures are analysed together, the high mortality is associated with the spirometric restriction and not with airflow obstruction.10

We examined the relation of national mortality rates from COPD, as recorded by the global health observatory, with the prevalence of airflow obstruction and spirometric restriction in 22 Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study sites, and with the prevalence of smoking and poverty. We also used the BOLD data from 22 sites to describe the distribution of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC less than the lower limit of normal (<LLN)) and spirometric restriction (FVC<LLN) across these sites and their relation with smoking prevalence and poverty stratified by sex.

Methods

The design and rationale for the BOLD study, the characteristics of samples and the prevalence of COPD in 14 sites have been reported elsewhere.3 11–13 Data collection from an additional eight sites has been completed since these earlier publications and added to the dataset for these analyses. The study population comprised non-institutionalised people aged 40 years and older stratified by sex.

BOLD sites are selected to represent the Global Burden of Disease regions, giving greater weight to larger regions but still ensuring at least two sites in most regions. Within regions, selection of sites is largely dependent on the availability of suitable collaborators, but sites are asked to sample from substantial populations of over 250 000 from predefined administrative areas to avoid highly exceptional populations.

Response rates were defined as the number of responders (those who completed the core questionnaire and post-bronchodilator spirometry) divided by the total number of individuals contacted. Cooperation rates were defined as the number of responders divided by the total number of responders plus active refusers.

Lung function, including FEV1 and FVC, was measured using the ndd EasyOne Spirometer (ndd Medizintechnik AG, Zurich, Switzerland), before and 15 min after inhaling salbutamol (200 μg) from a metered dose inhaler through a spacer. Spirograms were reviewed by the BOLD Pulmonary Function Reading Centre, and assigned a quality score based on acceptability and reproducibility criteria from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS).14 Spirometry technicians at BOLD sites were certified before data collection, received regular feedback on quality and were required to maintain a prespecified quality standard.

Outcome measures were airflow obstruction, defined as a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio below the LLN for age and sex,15 based on reference equations for Caucasians derived from the third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,16 and spirometric restriction defined as a post-bronchodilator FVC below the LLN for height, age and sex, based on the same reference population.

Information on respiratory symptoms, health status and exposure to risk factors was obtained from face-to-face interviews conducted in the subject's native language by trained and certified staff. Questions were derived from the 1978 ATS Epidemiology Standardisation Project,17 the European Community Respiratory Health Survey,18 the Consilio Nazionale Ricerche study,19 and the Obstructive Lung Disease in North Sweden study.20

National mortality data for 193 countries were obtained from the World Health Organization21 for two age groups, 15–59 and 60+ years, and expressed as rates/100 000 population. For each site we estimated for the age groups 40–59 years and 60+ years the prevalence of airflow obstruction and the prevalence of spirometric restriction using sampling weights to account for the sampling strategies in each site.

We compared the national COPD mortality rates against the prevalence of airflow obstruction and of spirometric restriction in the BOLD centres using Spearman rank correlation. We then regressed the same mortality rates against the gross national income (GNI) per person for the country using data from the World Bank and expressed as US dollars ($US) adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP)22 and the age-standardised national prevalence of cigarette smoking obtained from the Tobacco Atlas.23

We finally regressed the prevalence of airflow obstruction and spirometric restriction against the mean pack years smoked in the site and against the GNI22 and plotted the results.

We do not expect the variance of the regression errors to be equal across observations (homoscedasticity) because the outcome and predictor variables in the regression models reflect ‘means’ of variables (rather than individual observations) from populations that vary in size. Therefore we used weighted least squares regression for which the weight is the population.24 The bigger the population the smaller the variance of the regression errors. In the models for national mortality data, the weight is the total number of men and women in the relevant age group in each country. In the regression models for prevalence of airflow obstruction and spirometric restriction, the weight is the total number of people with acceptable spirometry data in each site. For each model fitted residuals were plotted against the predicted values to investigate linearity of associations. When associations were not linear we transformed the predictor variable. When looking at the relationships between national mortality levels from COPD and GNI we used log GNI as the predictor variable whereas when looking at the relationship between spirometric restriction and GNI, we used 1/GNI.

To test the robustness of our findings to missing data, we reran the analyses involving data from the BOLD sites after excluding those sites that had a cooperation rate of less than 60%.

All analyses were done using Stata V.12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). The correlation coefficients quoted are Spearman's rank correlation coefficients (rs). If appropriate, robust SEs were computed to take account of any clustering within countries. Ethical approval was obtained by each site from the local ethical committee and written informed consent was obtained from every participant.

Results

The sampling design used at each BOLD site is presented in online supplementary table E1 together with information on response and cooperation rates at each site. A third of the sites had cooperation rates above 80%, a third between 60% and 79% and a third below 60%. Low and middle income countries and Nordic countries had the highest cooperation rates.

The estimated prevalence of airflow obstruction aged 40 years and over ranged among men from 5.7% (Pune, India) to 23.0% (Cape Town, South Africa), and among women from 4.2% (Nampicuan, The Philippines) to 20.7% (Uppsala, Sweden) (table 1). The prevalence of spirometric restriction was much more variable, ranging among men from 8.4% (Bergen, Norway) to 67.7% (Mumbai, India) and among women from 6.7% (Bergen, Norway) to 70.5% (Srinegar, India).

Table 1.

Number of participants included, prevalence of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC<LLN) and low FVC (<LLN) and mean pack years smoked from the BOLD sites for men and women separately, and GNI/capita ($US PPP) and national smoking rates for men and women for countries containing BOLD sites

| Site (dates of fieldwork) | N | Prevalence of airflow obstruction (% FEV1/FVC<LLN): men | Prevalence of low FVC (% FVC<LLN): men | Smoking (mean pack years): men | Prevalence of airflow obstruction (% FEV1/FVC<LLN): women | Prevalence of low FVC (% FVC<LLN): women | Smoking (mean pack years): women | National GNI/capita($US PPP) | National cigarette consumption (current prevalence %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult men | Adult women | |||||||||

| Guangzhou, China (2003) | 473 | 9.3 | 30.0 | 21.5 | 6.3 | 30.5 | 1.0 | 6230 | 59.5 | 3.7 |

| Mumbai, India (2006/8) | 440 | 6.0 | 67.7 | 2.0 | 7.6 | 68.7 | 0.0 | 3000 | 27.6 | 1 |

| Pune, India (2008/9) | 849 | 5.7 | 63.1 | 1.2 | 6.8 | 70.5 | 0.1 | 3000 | 27.6 | 1 |

| Srinagar, India (2010/11) | 763 | 17.3 | 25.3 | 24.2 | 14.8 | 31.2 | 1.3 | 3000 | 27.6 | 1 |

| Manila, The Philippines (2005/6) | 893 | 15.1 | 62.4 | 18.7 | 4.2 | 62.9 | 2.7 | 3680 | 38.9 | 8.5 |

| Nampicuan-Talugtug, The Philippines (2008/9) | 722 | 16.9 | 52.7 | 20.6 | 13.5 | 61.0 | 3.3 | 3680 | 38.9 | 8.5 |

| Sydney, Australia (2006/7) | 541 | 7.6 | 16.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 9.4 | 9.9 | 35610 | – | – |

| Krakow, Poland (2005) | 526 | 14.9 | 10.7 | 23.7 | 12.2 | 9.6 | 7.5 | 17690 | 43.9 | 27.2 |

| Tartu, Estonia (2008/10) | 615 | 7.9 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 4.9 | 6.7 | 2.8 | 20630 | 49.9 | 27.5 |

| Bergen, Norway (2005/6) | 658 | 13.8 | 8.4 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 60220 | 33.6 | 30.4 |

| Hannover, Germany (2005) | 683 | 9.9 | 10.8 | 19.7 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 11.1 | 37540 | – | – |

| Lisbon, Portugal (2008) | 714 | 9.3 | 12.0 | 21.4 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 3.4 | 24060 | 40.6 | 31 |

| London, UK (2006/7) | 677 | 19.5 | 22.1 | 19.6 | 16.0 | 14.2 | 11.9 | 37490 | – | – |

| Maastricht, The Netherlands (2007/9) | 590 | 19.7 | 11.0 | 15.3 | 17.9 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 41840 | 38.3 | 30.3 |

| Reykjavik, Iceland (2004/5) | 757 | 9.2 | 14.9 | 13.9 | 13.5 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 30900 | 26.1 | 26.6 |

| Salzburg, Austria (2004/5) | 1258 | 13.4 | 11.0 | 17.1 | 20.7 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 39720 | 46.4 | 40.1 |

| Uppsala, Sweden (2006/7) | 547 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 12.2 | 8.7 | 10.0 | 8.0 | 40850 | 19.6 | 24.5 |

| Adana, Turkey (2003/4) | 806 | 19.8 | 13.1 | 27.0 | 9.1 | 15.7 | 4.3 | 14820 | 51.6 | 19.2 |

| Lexington, USA (2005/6) | 508 | 12.3 | 25.7 | 30.1 | 16.2 | 26.1 | 19.0 | 47280 | – | – |

| Vancouver, Canada (2005/6) | 827 | 14.5 | 8.4 | 15.0 | 12.5 | 8.4 | 9.2 | 38500 | 19 | 17.5 |

| Cape Town, South Africa (2005) | 847 | 23.0 | 47.6 | 16.1 | 16.9 | 46.1 | 8.7 | 10090 | 25 | 7.8 |

| Sousse, Tunisia (2010/12) | 661 | 8.6 | 25.1 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 27.2 | 0.0 | 8390 | 46.5 | 1 |

BOLD, Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GNI, gross national income; LLN, lower limit of normal; PPP, purchasing power parity.

The national mortality rates attributed to COPD in those aged 15–59 years were strongly correlated with the local prevalence of spirometric restriction in the BOLD sites in those aged 40–59 (men: rs=+0.73, p=0.0001; women rs=+0.90, p≤0.0001) but not with the prevalence of airway obstruction (men: rs=+0.28, p=0.2; women: rs=+0.17, p=0.46). Similarly the national mortality rates attributed to COPD in those aged 60+ years were strongly correlated with the local prevalence of spirometric restriction in the BOLD sites in those over 60 years old (men: rs=+0.63, p=0.0022; women: rs=+0.37, p=0.1) but not with the prevalence of airflow obstruction (men: rs=+0.28; p=0.23; women: rs=+0.22, p=0.33).

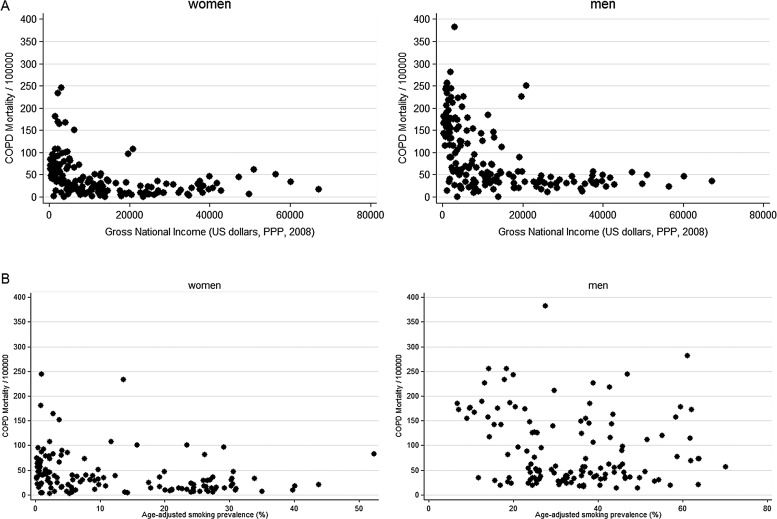

Plots of COPD mortality rates for the 179 countries with available data showed a strong inverse association with GNI, with rates rising rapidly as GNI fell below US$15 000 per capita per annum (figure 1A) and showed no clear positive association with the age standardised prevalence of cigarette smoking in the 135 countries with available data (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Age standardised national chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) mortality (age 15+ years) by sex and (A) annual per capita gross national income and (B) age-standardised national smoking prevalence. PPP, purchasing power parity.

Regression of national mortality rates from COPD against the logarithm of the GNI showed a strong negative association for both sexes and for both age groups (15–59 years and 60+ years) (p<0.001 in all cases) (table 2). For the 19 countries with BOLD data this association was qualitatively similar, though the regression coefficients were stronger (table 2).

Table 2.

Association of national mortality levels from COPD with logarithm of GNI/capita ($US PPP) for all 179 countries with information and for the 19 countries with BOLD sites, and age-adjusted national smoking prevalence for 135 available countries and with mean pack years smoked for 22 BOLD sites

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p Value | β | 95% CI | p Value | |

| GNI | ||||||

| Age 15–59 years | ||||||

| Log GNI (N=179) | −4.64 | −5.58 to −3.69 | <0.001 | −2.87 | −3.55 to −2.20 | <0.001 |

| Log GNI (BOLD countries: N=19) | −7.90 | −11.24 to −4.55 | <0.001 | −4.91 | −7.04 to −2.78 | <0.001 |

| Age >60 years | ||||||

| Log GNI (N=179) | −196 | −235 to −158 | <0.001 | −144 | −179 to −109 | <0.001 |

| Log GNI (BOLD countries: N=19) | −329 | −388 to −270 | <0.001 | −259 | −326 to −192 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Age 15–59 years | ||||||

| Age-adjusted smoking prevalence (%) (N=135) | −0.31 | −0.41 to −0.22 | <0.001 | −0.51 | −0.63 to −0.39 | <0.001 |

| Mean pack years (BOLD sites: N=22) | −0.52 | −0.98 to −0.07 | 0.027 | −0.74 | −1.34 to −0.14 | 0.019 |

| Age >60 years | ||||||

| Age-adjusted smoking prevalence (%) (N=135) | −5.57 | −9.987 to −1.164 | 0.014 | −24.47 | −28.59 to −20.36 | <0.001 |

| Mean pack years (BOLD sites: N=22) | −18.5 | −31.4 to −5.5 | 0.008 | −39.0 | −58.0 to −19.9 | <0.001 |

BOLD, Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GNI, gross national income; PPP, purchasing power parity.

Table 2 also shows the results of regressing mortality rates from COPD against national smoking rates. Coefficients are significantly negative for both age groups and both sexes. When this analysis was repeated using the local estimates of mean cumulative pack years smoked by the whole population in the 22 BOLD sites there was also a significant negative association in all groups with more smoking being associated with a lower national mortality rate for COPD (table 2).

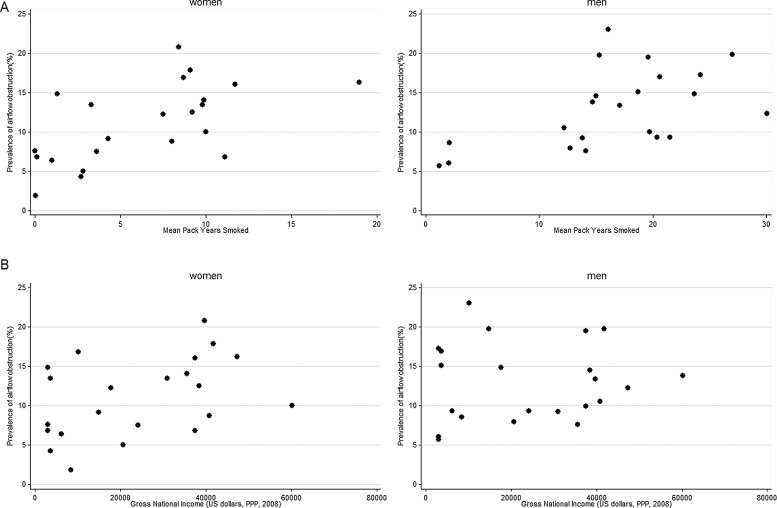

Although mortality from COPD was negatively associated with smoking, whether measured as the national age-standardised prevalence or as the local mean cumulative pack years smoked, there was a clear positive association between the prevalence of airflow obstruction and the mean pack years smoked in the 22 BOLD sites (figure 2A) accounting for 37% of the variance in men (p=0.003) and 35% of the variance in women (p=0.004) (table 3). The prevalence of airflow obstruction increased by 4.0% per 10 pack years smoked in men and by 6.7% per 10 pack years in women. The association between prevalence of airflow obstruction and GNI was weakly positive but not significant (men: p=0.78; women p=0.06) (figure 2B; table 3).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC<LLN) by sex and (A) mean pack years smoked and (B) annual per capita gross national income. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal; PPP, purchasing power parity.

Table 3.

Association of prevalence of airflow obstruction (%FEV1/FVC<LLN), spirometric restriction (% FVC <LLN) with mean pack years smoked and GNI/capita ($US PPP) in 22 BOLD sites

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p Value | β | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Airflow obstruction | ||||||

| Mean pack years | 0.40 | 0.15 to 0.64 | 0.003 | 0.67 | 0.24 to 1.10 | 0.004 |

| GNI (per US$1000 PPP) | 0.02 | −0.10 to 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.12 | −0.01 to 0.25 | 0.063 |

| Spirometric restriction | ||||||

| Mean pack years | −1.07 | −2.24 to 0.10 | 0.071 | −2.32 | −4.25 to −0.40 | 0.021 |

| 1/GNI (per US$1000 PPP) | 140 | 101 to 179 | <0.001 | 168 | 115 to 221 | <0.001 |

BOLD, Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GNI, gross national income; LLN, lower limit of normal; PPP, purchasing power parity.

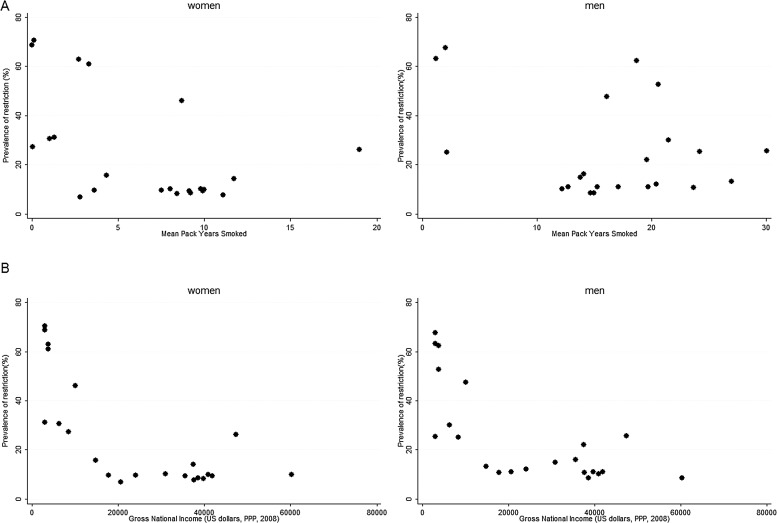

Table 3 also shows that spirometric restriction was slightly more common when smoking rates were higher, an association that was statistically significant for women (p=0.021) but not for men (p=0.071) (figure 3A; table 3). There was, however, a strong association between the prevalence of spirometric restriction and a lower GNI (men p<0001; women p<0.001) with rates rising rapidly as GNI fell below US$15 000/capita/annum (table 3; figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of a spirometric restriction (FVC<LLN) by (A) mean pack years smoked and (B) annual per capita gross national income. FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal; PPP, purchasing power parity.

When we reran the analyses reported in tables 2 and 3 after excluding the BOLD sites that had a cooperation rate of less than 60% the associations that we found were qualitatively similar to those using all the sites (see online supplementary tables E2 and E3).

Discussion

The poor correlation between mortality rates from COPD and the prevalence of smoking has been remarked on before at the national6 and international level,4 25 but the findings from BOLD go further in showing that smoking is a good predictor of the prevalence of airflow obstruction. Other causes of airflow obstruction, such as biomass exposure, are not therefore required to explain any discrepancy between the prevalence of obstruction and the prevalence of smoking.4

The strong relation of COPD mortality with poverty has also been described at a national level,6 and in England and Wales the social class gradient for COPD mortality is steeper than for either lung cancer or even tuberculosis.5 The implications for global health, however, have not been widely understood. Nor has the similarity of the global distributions of COPD mortality and the prevalence of spirometric restriction or their relation to the per capita GNI.

The prevalence of airflow obstruction correlates well with the mean pack years smoked in the BOLD sites and with national estimates of the prevalence of smoking. However, the national mortality rates from ‘COPD’ do not correlate with either the national prevalence of smoking or with the local prevalence of airflow obstruction. However, they do correlate well with the prevalence of spirometric restriction. Both ‘COPD’ mortality rates and the prevalence of spirometric restriction are strongly associated with the GNI per head of population, each rising steeply as GNI/capita falls below US$15 000 PPP.

Although we do not yet have direct evidence from the BOLD study, evidence from the USA shows that the FVC is a much stronger determinant of survival than the FEV1/FVC ratio.10 In population surveys it is unlikely that spirometric restriction represents severe obstruction, as it may do in clinics in which gas trapping due to obstruction may reduce the FVC. First, we found no association between the prevalence of airflow obstruction and spirometric restriction; second, in younger adults the FVC relates well to the total lung capacity;26 third, there is evidence among older people that the total lung capacity is also a good predictor of mortality and use of services;27 and finally, the BOLD sites with spirometric restriction are not those with a high prevalence of obstruction.

‘COPD’ is defined in terms of chronic airflow limitation2 but this definition has its limitations28 and in surveys the association between self-reported ‘COPD’ and airflow obstruction is weak.29 Given that very few people will have had spirometry, this discrepancy is unsurprising. In addition, given the difficulty in ante-mortem diagnosis, it is understandable if those with spirometric restriction and without airflow obstruction are certified as having died of ‘COPD’.

The BOLD project is the largest and most ambitious attempt to date to quantify the global variation in ventilatory function with associated symptoms and risk factors. The quality of lung function data from the BOLD study is controlled at a high level. All technicians were trained according to a common protocol and all the spirometric tracings were checked centrally for quality during the fieldwork and errors fed back to the technicians. When readings were inadequate, technicians were suspended until they had been retrained. Spirometry that did not reach ATS/ERS standards was rejected. Estimates of deaths by cause were taken from the Global Health Observatory of the World Health Organization21 and were calculated using methods summarised elsewhere.30

In some BOLD sites the estimates of prevalence are based on studies with relatively low response rates, but when we omitted all sites with a cooperation rate below 60%, the results did not materially change. There are very few data missing from national sources and those that are missing are generally from small countries. The main exceptions are a small number of large countries, such as the USA, Germany and Australia with missing smoking data. This small number of missing units is unlikely to make any difference to the results.

In comparing data from the BOLD sites with national data on smoking, income or mortality we are making an assumption that the sites are representative of their country. Formally this is not the case, but the assumption is nevertheless not unreasonable. First, although the sites were not randomly selected from all possible sites, we took care to sample from well defined and relatively large populations to avoid very special groups. Second, when we compare the BOLD data and the national data for smoking prevalence, we get very similar results. Third we know that the within-country variation in mortality is much less than the between-country variation, even in relatively homogeneous regions such as Europe.31 Finally, although in principle a misclassification arising from this assumption could explain a lack of association, it is unlikely to explain a strong association such as that between the prevalence of spirometric restriction and GNI.

The lack of association between smoking prevalence and mortality from ‘COPD’ is explained by the inverse association between poverty and smoking prevalence. At an individual level there is strong evidence from the BOLD study for an association between airflow obstruction and smoking,12 an association also reflected in the BOLD study at an ecological level (figure 2A). At an ecological level, however, there is no association between smoking and mortality from ‘COPD’.

We can only speculate about the reasons that FVC is low in poor countries. In some countries different norms are recommended for different ethnic groups16 32 and there is a common belief that FVC is racially determined, though the evidence for this is weak.33 In the UK BOLD study, African Caribbean and Asian, mostly South Asian, participants had similarly reduced FVC,34 and in the current analysis the associations with poverty are even stronger when the predominantly white European populations are excluded. The strongest association is seen in countries where the GNI is less than US$15 000 per annum and contains an ethnically very diverse group of communities, including populations in India, the Philippines, China, Tunisia and Turkey, and a Cape coloured community in South Africa which has a mixed Xhosa, Khoi, European and Malay ancestry. It is unlikely that genetics could explain away the strong association between spirometric restriction and poverty in this population. The observed coincidence of the high prevalence of spirometric restriction and the high mortality rate from ‘COPD’ is consistent with the earlier finding that the prognostic significance of a given FVC is independent of ethnicity and supports our decision not to adjust the lower limits of normal for ethnicity.35

The high prevalence of spirometric restriction in low-income countries is likely to be largely due to unknown environmental causes. There is a strong association with poverty but it is important to understand how this is mediated. Low birth weight is associated with spirometric restriction in many studies,26 36–39 and low birth weight is more common in developing countries (16%) and in the least developed countries (17%) when compared with industrialised countries (7%).40 Specific exposures also associated with spirometric restriction include exposure to indoor air pollution41 and a poor diet.42 More speculative risk factors include early infections43 and early exposure to biomass fuel.44

The mechanism by which spirometric restriction leads to death is also unclear, but it is unlikely that the spirometric restriction represents a high prevalence of classical restrictive lung diseases as these conditions are rare. Low ventilatory function is associated with other comorbidities and the excess deaths among those with low ventilatory function are often ascribed to cardiovascular causes.7 Comorbidities could explain some of the association between low lung volumes, measured as spirometric restriction or FEV1, and increased mortality.7 Nevertheless the fact that the deaths are ascribed to ‘COPD’ suggests that they are associated with substantial respiratory symptoms.

Tobacco is the highest ranked risk factor for disease burden in high-income North America and Western Europe and second only to high blood pressure globally according to the most recent estimates.45 Nevertheless, in low-income countries other factors associated with poverty dominate the risk of mortality attributed to ‘COPD’, even though spirometrically measured chronic airflow obstruction remains overwhelmingly a condition associated with smoking in all regions. There is a serious danger that an epidemic of smoking, if ever it were to become established in these vulnerable regions, would have even more devastating effects than we have seen so far in the more affluent countries.

It is unlikely that the high mortality attributed to ‘COPD’, particularly in low-income countries, is associated with chronic airflow obstruction. It is much more likely to be associated with spirometric restriction. These analyses challenge us to rethink our notions and beliefs about the origins and significance of chronic lung disease and its prominent role as a major cause of death in low-income countries. This by no means reduces the importance of tobacco control as the most important approach to the prevention of chronic airflow obstruction and other morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators : Research teams at centres: NanShan Zhong (PI), Shengming Liu, Jiachun Lu, Pixin Ran, Dali Wang, Jingping Zheng, Yumin Zhou (Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases, Guangzhou Medical College, Guangzhou, China); Ali Kocabaş (PI), Attila Hancioglu, Ismail Hanta, Sedat Kuleci, Ahmet Sinan Turkyilmaz, Sema Umut, Turgay Unalan (Cukurova University School of Medicine, Department of Chest Diseases, Adana, Turkey); Michael Studnicka (PI), Torkil Dawes, Bernd Lamprecht, Lea Schirhofer (Paracelsus Medical University, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Salzburg Austria); Eric Bateman (PI), Anamika Jithoo (PI), Desiree Adams, Edward Barnes, Jasper Freeman, Anton Hayes, Sipho Hlengwa, Christine Johannisen, Mariana Koopman, Innocentia Louw, Ina Ludick, Alta Olckers, Johanna Ryck, Janita Storbeck, (University of Cape Town Lung Institute, Cape Town, South Africa); Thorarinn Gislason (PI), Bryndis Benedikdtsdottir, Kristin Jörundsdottir, Lovisa Gudmundsdottir, Sigrun Gudmundsdottir, Gunnar Gundmundsson (Landspitali University Hospital, Department of Allergy, Respiratory Medicine and Sleep, Reykjavik, Iceland); Ewa Nizankowska-Mogilnicka (PI), Jakub Frey, Rafal Harat, Filip Mejza, Pawel Nastalek, Andrzej Pajak, Wojciech Skucha, Andrzej Szczeklik,Magda Twardowska (Division of Pulmonary Diseases, Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University School of Medicine, Cracow, Poland); Tobias Welte (PI), Isabelle Bodemann, Henning Geldmacher, Alexandra Schweda-Linow (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany); Amund Gulsvik (PI), Tina Endresen, Lene Svendsen (Department of Thoracic Medicine, Institute of Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway); Wan C Tan (PI), Wen Wang (iCapture Center for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada); David M Mannino (PI), John Cain, Rebecca Copeland, Dana Hazen, Jennifer Methvin (University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA); Renato B Dantes (PI), Lourdes Amarillo, Lakan U Berratio, Lenora C Fernandez, Norberto A Francisco, Gerard S Garcia, Teresita S de Guia, Luisito F Idolor, Sullian S Naval, Thessa Reyes, Camilo C Roa, Jr, Ma Flordeliza Sanchez, Leander P Simpao (Philippine College of Chest Physicians, Manila, The Philippines); Christine Jenkins (PI), Guy Marks (PI), Tessa Bird, Paola Espinel, Kate Hardaker, Brett Toelle (Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia); Peter G J Burney (PI), Caron Amor, James Potts, Michael Tumilty, Fiona McLean (National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London); E F M Wouters, G J Wesseling (Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands); Cristina Bárbara (PI), Fátima Rodrigues, Hermínia Dias, João Cardoso, João Almeida, Maria João Matos, Paula Simão, Moutinho Santos, Reis Ferreira (The Portuguese Society of Pneumology, Lisbon, Portugal); Christer Janson (PI), Inga Sif Olafsdottir, Katarina Nisser, Ulrike Spetz-Nyström, Gunilla Hägg and Gun-Marie Lund (Department of Medical Sciences: Respiratory Medicine & Allergology, Uppsala University, Sweden); Rain Jõgi (PI), Hendrik Laja, Katrin Ulst, Vappu Zobel, Toomas-Julius Lill (Lung Clinic, Tartu University Hospital); Parvaiz A Koul (PI), Sajjad Malik, Nissar A Hakim, Umar Hafiz Khan (Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, J&K, India); Rohini Chowgule (PI) Vasant Shetye, Jonelle Raphael, Rosel Almeda, Mahesh Tawde, Rafiq Tadvi, Sunil Katkar, Milind Kadam, Rupesh Dhanawade, Umesh Ghurup (Indian Institute of Environmental Medicine, Mumbai, India); Imed Harrabi (PI), Myriam Denguezli, Zouhair Tabka, Hager Daldoul, Zaki Boukheroufa, Firas Chouikha, Wahbi Belhaj Khalifa (Faculté de Médecine,Sousse, Tunisia); Luisito F Idolor (PI), Teresita S de Guia, Norberto A Francisco, Camilo C Roa, Fernando G Ayuyao, Cecil Z Tady, Daniel T Tan, Sylvia Banal-Yang, Vincent M Balanag, Jr, Maria Teresita N Reyes, Renato B Dantes (Lung Centre of The Philippines, Philippine General Hospital, Nampicuan&Talugtug, The Philippines); Sundeep Salvi (PI), Sundeep Salvi (PI), Siddhi Hirve, Bill Brashier, Jyoti Londhe, Sapna Madas, Somnath Sambhudas, Bharat Chaidhary, Meera Tambe, Savita Pingale, Arati Umap, Archana Umap, Nitin Shelar, Sampada Devchakke, Sharda Chaudhary, Suvarna Bondre, Savita Walke, Ashleshsa Gawhane, Anil Sapkal, Rupali Argade, Vijay Gaikwad (Vadu HDSS, KEM Hospital Research Centre Pune, Chest Research Foundation (CRF), Pune India). In the first phase of the study, Dr R O Crapo and Dr R L Jensen (LDS Hospital, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) were responsible for quality assurance of lung function; they and Dr Paul Enright (University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA) and Georg Harnoncourt (ndd Medizintechnik AG, Zurich, Switzerland) assisted with training lung function technicians.

Contributors: SB, WMV, PB were engaged in the initial design of the study. BK analysed the data. LG coordinated the later part of the study and AJ quality assured the lung function data for the second part of the study. All the other authors, including AJ, managed centres that collected data. PB drafted the initial manuscript and all authors contributed to its development and approved the final version.

Funding: The BOLD Study is funded by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (085790/Z/08/Z). The initial BOLD programme was funded in part by unrestricted educational grants to the Operations Center in Portland, Oregon from ALTANA, Aventis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, and the University of Kentucky. Additional local support for BOLD sites was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim China (GuangZhou, China); Turkish Thoracic Society, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Pfizer (Adana, Turkey); Altana, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis, Salzburger Gebietskrankenkasse and Salzburg Local Government (Salzburg, Austria); Research for International Tobacco Control, the International Development Research Centre, the South African Medical Research Council, the South African Thoracic Society GlaxoSmithKline Pulmonary Research Fellowship, and the University of Cape Town Lung Institute (Cape Town, South Africa); and Landspítali-University Hospital-Scientific Fund, GlaxoSmithKline Iceland, and AstraZeneca Iceland (Reykjavik, Iceland); GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, Polpharma, Ivax Pharma Poland, AstraZeneca Pharma Poland, ZF Altana Pharma, Pliva Kraków, Adamed, Novartis Poland, Linde Gaz Polska, Lek Polska, Tarchomińskie Zakłady Farmaceutyczne Polfa, Starostwo Proszowice, Skanska, Zasada, Agencja Mienia Wojskowego w Krakowie, Telekomunikacja Polska, Biernacki, Biogran, Amplus Bucki, Skrzydlewski, Sotwin, and Agroplon (Cracow, Poland); Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Pfizer Germany (Hannover, Germany); the Norwegian Ministry of Health's Foundation for Clinical Research, and Haukeland University Hospital's Medical Research Foundation for Thoracic Medicine (Bergen, Norway); AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline (Vancouver, Canada); Marty Driesler Cancer Project (Lexington, Kentucky, USA); Altana, Boehringer Ingelheim (Phil), GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Philippine College of Chest Physicians, Philippine College of Physicians, and United Laboratories (Phil) (Manila, The Philippines); Air Liquide Healthcare P/L, AstraZeneca P/L, Boehringer Ingelheim P/L, GlaxoSmithKline Australia P/L, Pfizer Australia P/L (Sydney, Australia); Department of Health Policy Research Programme, Clement Clarke International (London, UK); Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer (Lisbon, Portugal); Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, The Swedish Association Against Heart and Lung Diseases, Glaxo Smith Kline (Uppsala, Sweden); GlaxoSmithKline, Astra Zeneca, Eesti Teadusfond (Estonian Science Foundation) (Tartu, Estonia); AstraZeneca, CIRO HORN (Maastricht, The Netherlands); Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, J&K (Srinagar, India); Foundation for Environmental Medicine, Kasturba Hospital, Volkart Foundation (Mumbai, India); Boehringer Ingelheim (Sousse, Tunisia); Philippines College of Physicians, Philippines College of Chest Physicians, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Orient Euro Pharma, Otsuka Pharma, United laboratories Philippines (Nampicuan&Talugtug, The Philippines); National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London (Pune, India).

Disclaimer : The sponsors of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Competing interests: PB reports grants from Wellcome Trust and the UK Department of Health during the conduct of the study; other support from GSK, outside the submitted work. WMV reports grants from Merck, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Altana GSK, AstraZeneca, Novartis and Chiesi, during the conduct of the study. DM received honoraria/consulting fees and research funding from GSK, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Inc, Boehringer-Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Forest Laboratories Inc, Merck, and Creative Educational Concepts. Furthermore, he received royalties from Up-to-Date. WT reports grants from Joint sponsorship by GSK, AZ, BI, Altana, Norvatis, Pfizer, outside the submitted work. MS reports grants from Altana, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GSK, Merck Sharpe & Dome, Novartis, Salzburger Gebietskrankenkasse, and Salzburg Local Government during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Altana-Nycomed, Chiesi and Astra-Zeneca, grants and non-financial support from Air-Liquide, and personal fees from Menarini, and GSK outside the submitted work. GM reports grants from GSK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Air Liquide, Australian Lung Foundation, National Health and Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study; other from Novartis, outside the submitted work. AJ reports funding from South African Thoracic Society GlaxoSmithKline Pulmonary Research Fellowship; AK, IH, TG, BK, CJ, EB, PAK, SB, EN-M and LG have nothing to disclose.

Ethics approval: Each study required local ethical approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data from the BOLD Study are not generally available, but we do share data, with the agreement of the contributors, to achieve specific objectives.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: NanShan Zhong, Shengming Liu, Jiachun Lu, Pixin Ran, Dali Wang, Jingping Zheng, Yumin Zhou, Ali Kocabaş, Attila Hancioglu, Ismail Hanta, Sedat Kuleci, Ahmet Sinan Turkyilmaz, Sema Umut, Turgay Unalan, Michael Studnicka, Torkil Dawes, Bernd Lamprecht, Lea Schirhofer, Eric Bateman, Anamika Jithoo, Desiree Adams, Edward Barnes, Jasper Freeman, Anton Hayes, Sipho Hlengwa, Christine Johannisen, Mariana Koopman, Innocentia Louw, Ina Ludick, Alta Olckers, Johanna Ryck, Janita Storbeck, Thorarinn Gislason, Bryndis Benedikdtsdottir, Kristin Jörundsdottir, Lovisa Gudmundsdottir, Sigrun Gudmundsdottir, Gunnar Gundmundsson, Ewa Nizankowska-Mogilnicka, Jakub Frey, Rafal Harat, Filip Mejza, Pawel Nastalek, Andrzej Pajak, Wojciech Skucha, Andrzej Szczeklik, Magda Twardowska, Tobias Welte, Isabelle Bodemann, Henning Geldmacher, Alexandra Schweda-Linow, Amund Gulsvik, Tina Endresen, Lene Svendsen, Wan C Tan, Wen Wang, David M Mannino, John Cain, Rebecca Copeland, Dana Hazen, Jennifer Methvin, Renato B Dantes, Lourdes Amarillo, Lakan U Berratio, Lenora C Fernandez, Norberto A Francisco, Gerard S Garcia, Teresita S de Guia, Luisito F Idolor, Sullian S Naval, Thessa Reyes, Camilo C Roa, Ma Flordeliza Sanchez, Leander P Simpao, Christine Jenkins, Guy Marks, Tessa Bird, Paola Espinel, Kate Hardaker, Brett Toelle, Peter G J Burney, Caron Amor, James Potts, Michael Tumilty, Fiona McLean, E F M Wouters, G J Wesseling, Cristina Bárbara, Fátima Rodrigues, Hermínia Dias, João Cardoso, João Almeida, Maria João Matos, Paula Simão, Moutinho Santos, Reis Ferreira, Christer Janson, Inga Sif Olafsdottir, Katarina Nisser, Ulrike Spetz-Nyström, Gunilla Hägg, Gun-Marie Lund, Rain Jõgi, Hendrik Laja, Katrin Ulst, Vappu Zobel, Toomas-Julius Lill, Parvaiz A Koul, Sajjad Malik, Nissar A Hakim, Umar Hafiz Khan, Rohini Chowgule, Vasant Shetye, Jonelle Raphael, Rosel Almeda, Mahesh Tawde, Rafiq Tadvi, Sunil Katkar, Milind Kadam, Rupesh Dhanawade, Umesh Ghurup, Imed Harrabi, Myriam Denguezli, Zouhair Tabka, Hager Daldoul, Zaki Boukheroufa, Firas Chouikha, Wahbi Belhaj Khalifa, Luisito F Idolor, Teresita S de Guia, Norberto A Francisco, Camilo C Roa, Fernando G Ayuyao, Cecil Z Tady, Daniel T Tan, Sylvia Banal-Yang, Vincent M Balanag, Maria Teresita N Reyes, Renato B Dantes, Sundeep Salvi, Siddhi Hirve, Bill Brashier, Jyoti Londhe, Sapna Madas, Somnath Sambhudas, Bharat Chaidhary, Meera Tambe, Savita Pingale, Arati Umap, Archana Umap, Nitin Shelar, Sampada Devchakke, Sharda Chaudhary, Suvarna Bondre, Savita Walke, Ashleshsa Gawhane, Anil Sapkal, Rupali Argade, Vijay Gaikwad, R O Crapo, R L Jensen, Paul Enright, and Georg Harnoncourt

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;380:2095–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:347–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooper R, Burney P, Vollmer WM, et al. Risk factors for COPD spirometrically defined from the lower limit of normal in the BOLD project. Eur Respir J 2012;39:1343–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvi S, Barnes P. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet 2009;374:733–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Occupational mortality: the Registrar General's decennial supplement for Great Britain, 1979–80, 1982–83, Great Britain. Office of Population Censuses and Surveys London: H M Stationery Office, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker DJP, Osmond C. Childhood respiratory infection and adult chronic bronchitis in England and Wales. BMJ 1986;293:1271–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sin DD, Anthonisen NR, Soriano JB, et al. Mortality in COPD: role of comorbidities. Eur Respir J 2006;28:1245–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannel WB, Hubert H, Lew EA. Vital capacity as a predictor of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J 1983;105:311–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, et al. Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA 1998;279:585–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burney PGJ, Hooper R. Forced vital capacity, airway obstruction and survival in a general population sample from the USA. Thorax 2011;66:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Sullivan SD, et al. The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Initiative (BOLD): rationale and design. COPD 2005;2:277–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007;370:741–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer WM, Gíslason T, Burney P, et al. Comparison of spirometry criteria for the diagnosis of COPD: results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J 2009;34:588–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:153–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL, et al. Using the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstruction. Thorax 2008;63:1046–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:179–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferris BG. Epidemiology standardization project (American Thoracic Society). Am Rev Respir Dis 1978. 12;118:t-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burney P, Luczynska C, Chinn S, et al. The European Community respiratory health survey. Eur Respir J 1994;7:954–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazzi P, Viegi G, Paoletti P, et al. Comparison between two standardized questionnaires and pulmonary function tests in a group of workers. Eur J Respir Dis 1982;63:168–9 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundbäck B, Nyström L, Rosenhall L, et al. Obstructive lung disease in northern Sweden: respiratory symptoms assessed in a postal survey. Eur Respir J 1991;4:257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Mortality and burden of disease: disease and injury country estimates, 2008, by sex and age. http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disese/global_burden_disease_death_estimates_sex_age_2008.xls (accessed 3 Jun 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Bank. Open data: indicators: gross national income per capita, PPP (current international $). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD (accessed 3 Jun 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shafey O, Eriksen M, Ross H, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. 3rd edn http://www.tobaccoatlas.org/downloads/TobaccoAtlas_sm.pdf (accessed 3 Jun 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson R, MacKinnon JG. Economic theory and methods. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown CA, Crombie AK, Tunstall-Pedoe H. Failure of cigarette smoking to explain international differences in mortality from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:134–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hancox RJ, Poulton R, Greene JM, et al. Associations between birth weight, early childhood weight gain and adult lung function. Thorax 2009;64:228–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedone C, Scarlata S, Chiurco D, et al. Association of reduced total lung capacity with mortality and use of health services. Chest 2012;141:1025–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postma DS, Brusselle G, Bush A, et al. I have taken my umbrella, so of course it does not rain. Thorax 2012;67:88–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindberg A, Jonsson A, Ronmark E, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to BTS, ERS, GOLD and ATS criteria in relation to doctor's diagnosis, symptoms, age, gender, and smoking habits. Respiration 2005;72:471–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL. Chapter 3: The burden of disease and mortality by condition: data, methods and results for 2001. In: Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL, eds. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006:45–240 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holland WW, ed. European Community Atlas of ‘Avoidable Death’ . 2nd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellamy D. Spirometry in Practice: A Practical Guide to Using Spirometry in General Practice. 2nd ed London: British Thoracic Society COPD Consortium, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundy Braun L, Wolfgang M, Dickersin K. Defining race/ethnicity and explaining difference in research studies on lung function. Eur Respir J 2013;41:1362–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hooper R, Burney P. Cross-sectional relation of ethnicity to ventilatory function in a West London population. Int J Tuberc Resp Dis 2013;17:400–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burney PGJ, Hooper RJ. The use of ethnically specific norms for ventilatory function in African-American and white populations. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:782–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein C, Kumaran K, Hall CH, et al. Relation of fetal growth to adult lung function in south India. Thorax 1997;52:895–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards CA, Osman LM, Godden DJ, et al. Relationship between birth weight and adult lung function: controlling for maternal factors. Thorax 2003;58:1061–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canoy D, Pekkanen J, Elliott P, et al. Early growth and adult respiratory function in men and women followed from the fetal period to adulthood. Thorax 2007;62:396–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pei L, Chen G, Mi J, et al. Low birth weight and lung function in adulthood: retrospective cohort study in China, 1948–1996. Pediatrics 2010;125:e899–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.United Nations Children's Fund. The State of the World's Children, 2008. http://www.unicef.org/sowc/ (accessed 5 Dec 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misra P, Srivastava R, Krishnan A, et al. Indoor air pollution-related acute lower respiratory infections and low birthweight: a systematic review. J Trop Pediatr 2012;58:457–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Checkley W, West JKP, Wise RA, et al. Maternal vitamin A supplementation and lung function in offspring. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1784–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaheen SO, Barker DJ, Holgate ST. Do lower respiratory tract infections in early childhood cause chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995. 02;151:1649–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulkarni N, Pierse N, Rushton L, et al. Carbon in airway macrophages and lung function in children. N Engl J Med 2006;355:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.