Abstract

Objective

To identify factors associated with triptan discontinuation among migraine patients.

Background

It is unclear why many migraine patients who are prescribed triptans discontinue this treatment. This study investigated correlates of triptan discontinuation with a focus on potentially modifiable factors to improve compliance.

Methods

This multi-center cross-sectional survey (n=276) was performed at U.S. tertiary care headache clinics. Headache fellows who were members of the American Headache Society Headache Fellows Research Consortium recruited episodic and chronic migraine patients who were current triptan users (use within prior 3 months and for ≥ 1 year) or past triptan users (no use within 6 months; prior use within 2 years). Univariate analyses were first completed to compare current triptan users to past users for: migraine characteristics, other migraine treatments, triptan education, triptan efficacy, triptan side effects, type of prescribing provider, Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scores and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores. Then, a multivariable logistic regression model was selected from all possible combinations of predictor variables to determine the factors that best correlated with triptan discontinuation.

Results

Compared to those still using triptans (n=207), those who had discontinued use (n=69) had higher rates of medication overuse (30 vs. 18%, p=0.04), were more likely to have ever used opioids for migraine treatment (57 vs. 38%, p=0.006) as well as higher MIDAS (mean 63 vs. 37, p=0.001) and BDI scores (mean 10.4 vs. 7.4, p=0.009). Compared to discontinued users, current triptan users were more likely to have had their triptan prescribed by a specialist (neurologist, headache specialist, or pain specialist) (74 vs. 54%, p=0.002) and were more likely to report headache resolution (53 vs. 14%, p<0.001) or a reduction in pain intensity (71 vs. 28%, p<0.001) most of the time from their triptan. On a 1-5 scale (1=disagree, 5=agree), triptan users felt they had more: control over their migraine attacks (2.9 vs. 2.1), confidence in their prescribing provider (4.5 vs. 4.0), and were more educated about triptan use (4.2 vs. 3.7) compared to triptan discontinuers (p<0.001 for all comparisons). Although both current and prior users reported similar rates of side effects (48 vs. 43%, p=0.44), of those who discontinued use, the main reasons were for lack of effect (44%) and side effects (29%). Our multivariable modeling revealed that the strongest correlate of triptan discontinuation was lack of efficacy (OR=17, 95% CI [8.8, 33.0]). Other factors associated with discontinuation included MIDAS>24 (2.6, [1.5, 4.6]), BDI >4 (2.5, [1.4, 4.5]), and a history of ever using opioids for migraine therapy (2.2, [1.3, 3.8]). Having a triptan prescribed by a specialist and using at least one other abortive medication with the triptan were associated with a decreased likelihood of triptan discontinuation (0.41, [0.2-0.7] and 0.44 [0.3, 0.8], respectively).

Conclusions

As expected, discontinuation was most correlated with lack of efficacy, but other important factors associated with those who had discontinued use included greater migraine related disability, depression, and the use of opioids for migraine attacks. Compared to patients who had discontinued triptans, current triptan users felt more: educated about their triptan, control over their migraine attacks, and confidence in their prescribing provider. Current triptan users also had their triptan prescribed by a specialist more often and used other abortive medications with their triptan compared to patients who had discontinued triptans. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot determine if these factors contributed to triptan discontinuation or reflect the impact of such discontinuation. Interventions that address modifiable risk factors for triptan discontinuation may decrease the likelihood of triptan discontinuation and thus improve overall migraine control.

Since lack of efficacy was most strongly associated with triptan discontinuation, future research should determine why triptans are effective for some patients but not others.

Keywords: Triptan, Discontinuation, Adherence, Migraine, Treatment

Introduction

Migraine specific medications, particularly triptans, have revolutionized the acute treatment of migraine and have thus become a standard of care.(1) Since the FDA's approval of sumatriptan in 1992, seven triptans, some available in multiple formulations, have been approved in the United States. Despite their availability as well as their established safety and efficacy profile, less than 1/5 of migraine sufferers in the US are prescribed triptans.(2) Of those who do receive a triptan, at least 1/3 discontinue use within a year(3). The American Migraine Studies have demonstrated that migraine continues to be as disabling and under-treated today as it was two decades ago.(4) It is therefore important to identify and address factors that contribute to the discontinuation of triptans.

Although there is extensive literature regarding medication adherence in chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, there have only been a few studies examining adherence in the migraine population. Studies of prophylactic migraine medications have suggested a high rate of non-adherence (approximately 35% to 50%) (5-7). The main reasons for prophylactic medication discontinuation are lack of efficacy and side effects.(8) There are very limited data regarding adherence to or discontinuation of migraine abortive medications. Bigal and colleagues examined risk factors for switching triptan medications in a group of episodic migraineurs (n=386).(9) Factors related to switching triptans included efficacy, consistency, recurrence, curiosity, and formulation. Side effects and lack of efficacy were important predictors.

Lipton and colleagues examined reasons for triptan discontinuation compared to reasons for opioid discontinuation in adults who completed surveys as part of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study in 2008 and 2009. Investigators found that in the two groups combined (n=493), the most common reasons for discontinuation were failure to relieve pain, reoccurrence of pain after initial relief, concern over medication side effects, and loss of initial efficacy.(10) The only significant predictor of triptan discontinuation was age, as older individuals were more likely to discontinue triptans (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00-1.04, p=0.023).

A study by Cady and colleagues compared triptan sustained users (n=586) to lapsed users (n=199).(11) Migraine patients recruited through primary care physician offices and an HMO pharmacy database completed migraine surveys. Survey responses were categorized as those who were sustained users (filled a triptan prescription in the prior year) vs. lapsed users (did not fill a triptan script in the prior year). Compared to lapsed users, sustained users: switched triptans less often during the prior year, had greater belief in control over their migraine attacks, had greater belief that their medications were important for treatment outcomes, were less likely to be using opioid analgesics, reported following their health care professional's instructions to a greater degree, and had a higher level of satisfaction with their current triptan.

Cady's study was instrumental in helping to identify factors associated with triptan discontinuation in the primary care population, and Lipton's study was valuable in distinguishing those who discontinued triptans versus opioids. The specific predictors of triptan discontinuation in migraine patients presenting to tertiary care headache centers remain unclear. In this context, we conducted a survey to determine factors associated with discontinuation of triptans among episodic and chronic migraine patients initially presenting to a tertiary care specialty headache clinic. Our study builds on prior research since it enrolled a different patient population (adults from specialty headache clinics), queried specifically about reasons for triptan discontinuation, examined possible predictors of triptan discontinuation that have not previously been evaluated, and focused on potentially modifiable risk factors such as subject education and knowledge regarding triptan use. In order to appropriately target education and interventions to prevent unnecessary triptan discontinuation, the reasons why patients with migraine are discontinuing triptans needs to be determined. Examining predictors of triptan discontinuation with a focus on potentially modifiable risk factors could lead to interventions that may decrease the rate of unnecessary triptan discontinuation and improve patient outcomes.

Methods

This was a multi-center cross-sectional survey study performed at tertiary care headache specialty clinics in the United States Twenty-five Headache Fellows at seven different headache centers (see Acknowledgements for details) who were participating in their headache training between July 2009 and June 2012 and members of the American Headache Society Headache Fellows Research Consortium and their Fellowship Directors served as investigators. IRB approvals were obtained by each participating center and all subjects completed the informed consent process prior to study participation.

New patients to the Headache Center who had episodic or chronic migraine according to International Classification of Headache Disorders-II diagnostic criteria and were either current or past triptan users were recruited to complete surveys. “Current use” was defined as having used a triptan within the prior 3 months and having used triptans for at least 1 year. “Discontinued use” was defined as having used a triptan within the prior 2 years but not having used a triptan within the prior 6 months. There were no exclusions for the duration or extent of use prior to discontinuation. Patients with medication overuse were not excluded. Headache diagnoses were assigned following a semi-structured interview performed by the Headache Fellow using study questionnaires and with typical oversight from Headache Center faculty. Each participant signed written informed consent. Physicians asked the survey questions for the first half of the survey (completed in approximately 10 minutes); subjects were able to complete the remaining questions on their own (in approximately 10-20 minutes).

Data were collected to determine risk factors for triptan discontinuation and self-reported reasons for discontinuation. The ‘discontinued triptan’ referred to the last triptan medication that the subject discontinued while ‘current triptan’ referred to the most recent triptan that the subject had used. The surveys collected data from all participants on: demographics, headache characteristics, current and prior acute and prophylactic medications use for migraine, and number and type of providers seen for migraines. Details collected about current/prior triptan use included perceived efficacy, side effects, education received and desired at time of triptan prescribing, knowledge about triptans, expectations from triptans, and satisfaction with therapy. Participants also completed the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. (See Appendices for Surveys). Further analyses regarding triptan knowledge, education, and expectations are reported in separate papers.

Additional data collected from subjects who discontinued triptans addressed the importance of different factors in deciding to discontinue the triptan including: cost, lack of effect, equivalent efficacy of non-triptan medications, side effects, safety concerns, development of a triptan contraindication, decrease in migraine severity, migraines ceased, and inability to obtain refills.

All de-identified data were submitted to the principal investigator at the coordinating site where data were then entered into a secure database. All data entry was double-checked for accuracy. Surveys were reviewed to confirm inclusion/exclusion criteria and appropriate categorization of “current” and “discontinued” triptan use. Of the 296 migraineurs who completed the surveys, 20 participants who completed the survey were excluded from the analyses because they did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria (16 discontinued triptan users, 4 continued triptan users). Statistical analyses were performed at the coordinating center using SAS, v 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Statistical Analyses

First, we conducted univariate analyses: differences in proportions between the Discontinued and Current Use groups were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test, and means were compared by using the two-sample t test. The Fisher exact test was used instead of the Pearson chi-square test if the minimum expected cell count was less than 5. Distributions of ordered categories were assessed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Then, a multivariable logistic regression model was selected from all possible combinations of predictor variables by maximizing the likelihood score statistic. Cutoff values for prediction were selected by maximizing the Youden index.

Results

Of the 276 subjects who completed this survey, 69 had discontinued triptans and 207 were current triptan users. Most (83%) of the triptans used by the participants in this study were the pill (oral) formulation; both discontinued and continued users also reported some use (3-10% each) of other formulations including dissolving tablets, nasal spray, and injections. Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of current triptan users vs. discontinued users. Of those that discontinued use, most had episodic migraines without aura (49%) and/or with aura (25%), many had chronic migraine (46%) and 30% had medication overuse (percentages do not add up to 100 as patients may have both migraine with and without aura and may have chronic migraine with or without medication overuse). Similar rates were found in those that continued to use triptans, such that 56% had episodic migraines without aura and/or 25% with aura, 41% with chronic migraine, and 18% with medication overuse (Table 1). Most patients in this study were white (87%) and female (88%). In general, those who discontinued triptans were younger with less formal education and a lower income than those still using triptans. The prevalences of the different headache types were similar across the two groups, except that more of those who had discontinued triptans had medication overuse headache (30 vs. 18%, p=0.04). While both groups had similar number of migraine days per month (10), those who had discontinued triptans had more headaches days per month than continued users (16 vs. 13, p=0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Discontinued and Continued Triptan Users.

| BASELINE CHARACTERISTIC | Discontinued Use, n=69 | Continued Use, n=207a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 39 (12) | 43 (12) | 0.02 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.19 | ||

| Female | 58 (84) | 186 (90) | |

| Male | 11 (16) | 21 (10) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.11 | ||

| White | 55 (80) | 185 (89) | |

| Black | 6 (9) | 8 (4) | |

| American Indian, Asian, Pacific Islander, Other | 8 (12) | 14 (7) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.01 | ||

| ≤High School | 24 (35) | 52 (25) | |

| Undergraduate Degree | 33 (48) | 83 (40) | |

| Graduate Degree | 12 (17) | 72 (35) | |

| Income, n (%) | 0.006 | ||

| ≤30,000 | 15 (22) | 23 (11) | |

| $30,001-$50,000 | 8 (12) | 26 (13) | |

| $50,001-$75,000 | 17 (25) | 40 (29) | |

| $75,001-$100,000 | 17 (25) | 45 (22) | |

| >$100,000 | 12 (17) | 72 (35) | |

| Headache Features | |||

| Episodic Migraine with Aura, n (%) | 17 (25) | 51 (25) | >0.99 |

| Episodic Migraine without Aura, n (%) | 34 (49) | 115 (56) | 0.36 |

| Chronic Migraine, n (%) | 32 (46) | 84 (41) | 0.40 |

| Years with Migraine, mean (SD) | 20 (12) | 24 (13) | 0.03 |

| Medication Overuse Headache, n (%) | 21 (30) | 37 (18) | 0.04 |

| Migraines (days/month); mean (SD) | 10 (9) | 10 (8) | 0.68 |

n=206 for income; n=201 for medication overuse headache

Univariate comparisons between triptan users and subjects who discontinued triptans yielded many factors that differed between the two groups (Table 2). While those still using triptans have used triptans more often and for more years, those who discontinued triptans demonstrated considerable experience with triptans, using triptans on average for 2.3 years for the treatment of 75 migraines, and had tried almost 3 different triptans. Current triptan users took other abortive medications with triptans more than discontinued users (57 vs. 36%, p = 0.003). The two groups did not differ on use of prophylactic agents or days per month of abortive medication use. Subjects who had discontinued triptans had used opioids at some point in their lives for migraine treatment more than current users (57 vs. 38%, p = .006), although current use of opioids for migraines or for any reason was not statistically different between the two groups (15 vs. 8%, p=0.12; 19 vs. 13%, p=0.24, respectively). Discontinued users had higher MIDAS (mean 63 vs. 37, p=0.001) and BDI scores (mean 10.4 vs. 7.4, p=0.009) compared to current triptan users.

Table 2.

Medication Usage and Headache Disability Scores of Discontinued Users vs. Continued Triptan Users.

| CHARACTERISTIC | Discontinued Use, n=69a | Continued Use, n=207b | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Use | |||

| Number of triptans ever used; mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.9) | 3.2 (2.2) | 0.132 |

| Number of migraines treated with triptan; mean (SD) | 75 (330) | 273 (500) | <0.001 |

| Duration of triptan use, years; mean (SD) | 2.3 (3.9) | 4.9 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Other medication used with triptan, n (%) | 25 (36) | 117 (57) | 0.003 |

| Abortive medication use (days/month); mean (SD) | 12 (10) | 10 (8) | 0.14 |

| Current prophylactic medication, n (%) | 42 (61) | 148 (71) | 0.10 |

| Ever used opioids for migraine, n (%) | 39 (57) | 79 (38) | 0.006 |

| Current use of opioids for migraine, n (%) | 10 (15) | 17 (8) | 0.12 |

| Current opioid use for any reason, n (%) | 13 (19) | 27 (13) | 0.24 |

| Headache Disability Scores | |||

| Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scores, mean (SD) | 63 (59) | 37 (48) | 0.001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory scores, mean (SD) | 10.4 (9.6) | 7.4 (7.3) | 0.009 |

n=68 for all opioid use questions; number of triptans ever used; abortive medication use; n=67 for number of migraines treated with triptan

n=206 for abortive medication use and number of triptans ever used

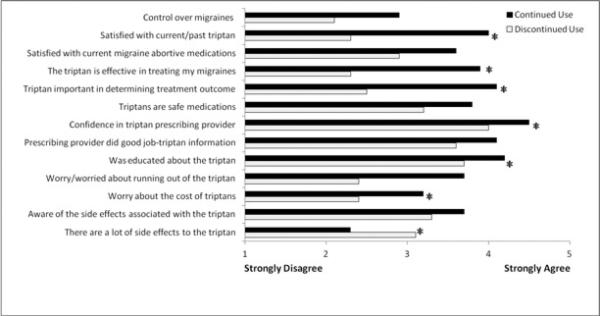

Triptan users had more positive perceptions regarding triptans and migraine control than discontinued users (Figure 1). On a scale of 1-5 (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), triptan users felt they had more: control over their migraines (2.9 vs. 2.1), triptan satisfaction (4.0 vs. 2.3), confidence in their prescribing provider (4.5 vs. 4.0), and were more educated about triptan use (4.2 vs. 3.7) compared to triptan discontinuers (p<0.001 for all comparisons). While being treated with triptans, current users more often worried about running out of the medicine (3.7 vs. 2.4) and about the cost of triptans (3.2 vs. 2.4) than prior users (p<0.001 for all comparisons). Although current users were more aware of the side effects associated with triptans (3.7 vs. 3.3, p=0.002), triptan users did not feel there were as many triptan side effects compared to non-users (2.3 vs. 3.1) (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Perceptions about Migraines and Triptans in Continued vs. Discontinued Triptan Users

At the time the triptan was prescribed, triptan users reported being given specific instructions about triptan use more often compared to discontinued users. Specifically, on the same 1-5 scale as above, compared to triptan discontinuers, triptan users agreed that they were educated about: how to decide if they should take the triptan (4.0 vs. 3.6), when to take the triptan in the course of a headache (4.1 vs. 3.8), how much relief to expect from the triptan (3.7 vs. 3.4), possible side effects from the triptan (3.7 vs. 3.4), and what to do/take if the triptan did not work (3.6 vs. 3.3, p<0.05 for all comparisons). Triptan users reported more time spent being educated about triptan use by the prescribing provider than those who had discontinued triptans (10.8 minutes +/− 13.2 vs. 7.3 +/− 7.2, p<0.05), although those who had discontinued triptans reported more time spent being educated about triptan use from educational materials provided by the prescriber (5.0 minutes +/− 13.1 vs. 1.5 +/− 4.6, p=0.001).

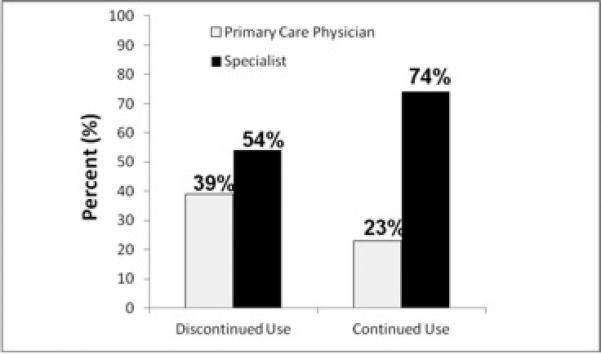

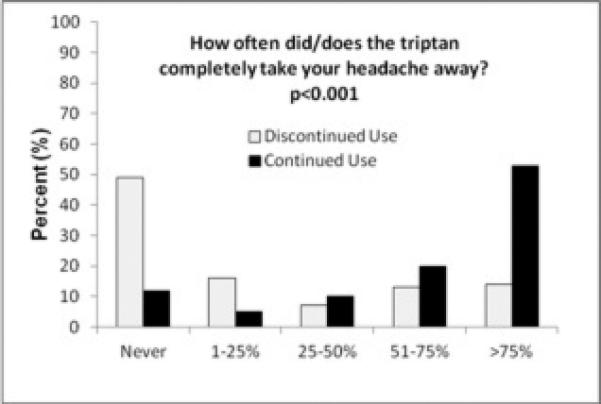

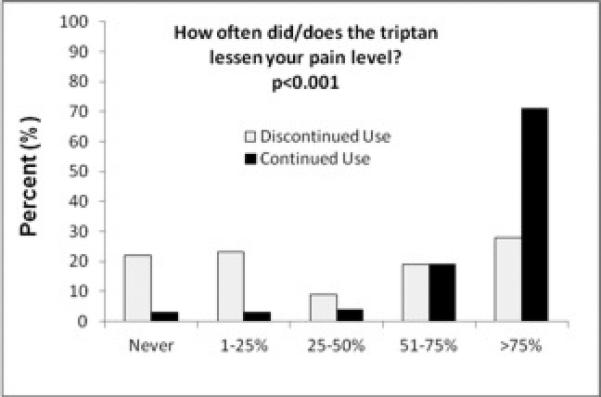

More triptan users had their current triptan prescribed by a specialist (neurologist, headache specialist, or pain doctor) than triptan discontinuers (74% vs. 54%, p=0.002) (Figure 2). Triptan users reported more headache resolution (53 vs. 14%, p<0.001) (Figure 3A) or reduction in pain intensity (71 vs. 28%, p<0.001) (Figure 3B) most of the time from their triptan compared to those who discontinued triptans (p<0.001 for all analyses). About half of triptan users felt triptans completely abolished their headaches more than 75% of the time and three-quarters of triptan users felt it lessened their pain level more than 75% of the time.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of Who Prescribed Triptans for Continued vs. Discontinued Triptan Users*

Figure 3.

Reported Headache Relief from Triptans in those that Discontinued vs. Continued Triptan Use

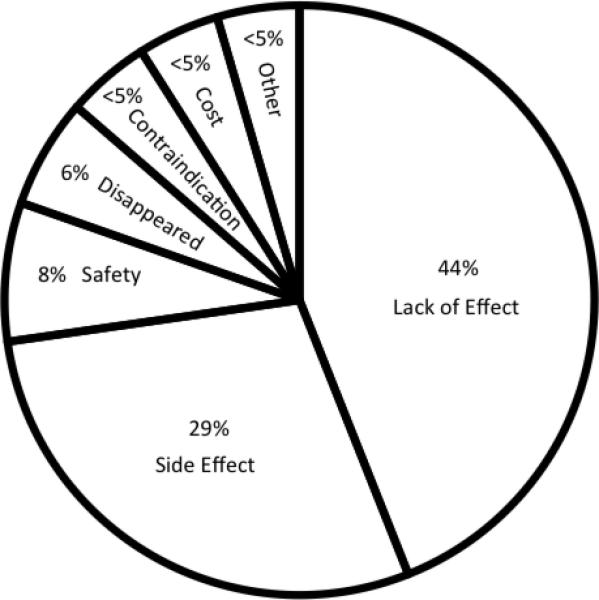

Although triptan users and those who had discontinued triptans reported similar rates of having experienced side effects (48% vs. 43%, p=0.44) and similar frequencies of side effects (0.7 +/− 1.1 vs. 1.0 +/− 1.3, p=0.12), of those who discontinued triptan use (n=69), the main reasons chosen as most important for discontinuation were lack of effect (44%), and side effects (29%) (Figure 4). Adults who discontinued triptans reported more severe side effects compared to current triptan users (26 vs. 9%, p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Top Reason Chosen for Triptan Discontinuation among those that Discontinued Triptans (n=69)

Our multivariable modeling revealed that while having a triptan prescribed by a specialist and using at least one other abortive medication with a triptan were associated with a decreased likelihood of triptan discontinuation, using opioids for migraines ever, having a BDI score >4 or MIDAS score >24 were associated with a higher likelihood of triptan discontinuation (Table 3). Individuals who felt they did not have control over their migraines and those who did not worry about running out of their triptan were more likely to have discontinued triptan use. In addition, individuals who felt the triptan did not provide much headache relief, were not satisfied with their triptan, and did not feel the triptan was effective in treating migraines had the greatest likelihood of triptan discontinuation. Specifically, disagreement to the statement that “the triptan was/is effective in treating my migraines” had the largest OR of triptan discontinuation (17 [8.8-33.0]). No multivariable model was substantially better than this model.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Triptan Discontinuation

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | Sensitivitya % | Specificityb % | PPV % | NPV % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triptan prescribed by specialist | 0.41 | 0.2-0.7 | 54 | 26 | 19 | 63 |

| At least one other medication taken with triptan | 0.44 | 0.3 -0.8 | 36 | 43 | 18 | 67 |

| Ever used opioids for treatment of migraines | 2.2 | 1.3-3.8 | 57 | 62 | 33 | 82 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) >4 | 2.5 | 1.4-4.5 | 72 | 48 | 32 | 84 |

| Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) >24 | 2.6 | 1.5-4.6 | 64 | 60 | 35 | 83 |

| Did not feel had control over migrainesc | 3.5 | 2.0-6.3 | 71 | 59 | 37 | 86 |

| Did not worry about running out of triptand | 6.9 | 3.7-13.0 | 77 | 67 | 44 | 90 |

| <25% of the time triptan completely took headache away | 9.2 | 5.0-17.0 | 65 | 83 | 56 | 88 |

| ≤50% of the time triptan lessened pain level | 10 | 5.3-20.0 | 54 | 90 | 64 | 85 |

| Did not feel satisfied with current/prior triptane | 13 | 6.6-24.0 | 77 | 79 | 55 | 91 |

| Did not feel the triptan was effective in treating migrainef | 17 | 8.8-33.0 | 68 | 89 | 67 | 89 |

A multivariable logistic regression model was selected from all possible combinations of predictor variables by maximizing the likelihood score statistic.

OR=Odds Ratio; the odds of triptan discontinuation

CI=Confidence Interval

PPV=positive predictive value

NPV=negative predictive value

Sensitivity of Triptan Users, n=69 except n=68 for Opioid for Migraine Ever

Specificity of Triptan Discontinued Users, n=207 except n=205 for MIDAS>24

Answered ‘Disagree or Strongly Disagree’ to statement, “I have control over my migraines”

Answered ‘Neutral, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree’ to statement “I worried/worry about running out of my triptan”

Answered ‘Neutral, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree’ to statement, “I was/am satisfied with my previously used/current triptan”

Answered ‘Disagree or Strongly Disagree’ to statement, “The triptan was/is effective in treating my migraines”

Discussion

We found that adults presenting to academic tertiary care centers often discontinue triptans due to lack of effect or side effects. The results also demonstrate that having a triptan prescribed by a specialist and using at least one other acute medication with a triptan decreased the likelihood of triptan discontinuation. In addition, the likelihood of discontinuation was higher in patients who had a prior history of using opioids for migraines as well as in those with higher depression and migraine-related disability scores. Continued triptan users reported receiving specific detailed instructions on triptan use more often and viewed the impact/efficacy of triptans more favorably than discontinued triptan users. Overall, those who had discontinued triptan use had less formal education and lower income than continued users.

Our study is consistent with prior research that has demonstrated the importance of efficacy and side effects in determining the discontinuation of migraine medications (8-11) We also showed, similar to Cady's study, that compared to those no longer using triptans, those still using triptans were less likely to have ever used opioids for migraines and felt: they had more control over their migraine attacks, their medications were important in treatment outcomes, and felt satisfied with their triptans.(11) We have extended prior research by demonstrating that those who continued triptans more often received triptan education and were more likely to have been prescribed the triptan by a specialist (neurologist, headache or pain specialist). In addition, although those who discontinued triptans listed side effects as one of the most common reasons for discontinuation, the side effect rates and frequencies were similar between those who discontinued and continued triptan use, with current triptan users even reporting more awareness of the presence of triptan side effects. Although the side effect rates were similar, the frequency of more severe side effects was much higher among those who discontinued, suggesting that the severity, rather than the presence, of side effects may be a determining factor in triptan discontinuation. It is also possible that those who have been educated about the side effect profile of triptans were less concerned when side effects did occur and therefore less likely to discontinue their triptan.

The greatest predictor of triptan discontinuation (OR of 17) was triptan inefficacy. Understanding why triptans are effective in some but not others is critical for future research. The participants in our study who discontinued triptans had considerable experience with triptan use prior to discontinuation, using triptans on average for 2.3 years for the treatment of 75 migraines, and had tried almost 3 different triptans. This is a very different population from those who may have tried a triptan once or twice and never found it effective. Presumably, subjects who discontinued triptans because of inefficacy after frequent and prolonged use initially derived benefit from the triptans before they were discontinued. Thus, further research to understand why triptans become ineffective in those who previously had a response is also very clinically valuable. However, even though triptan discontinuers had considerable experience with triptans, as figure 3 demonstrates, when they did use them they were not as effective in lessening or resolving their pain compared to those who continued using them. Further, those who were continuing to use triptans reported more satisfaction with their triptan, felt triptans were more effective in treating their migraines, and reported more control over their migraine attacks than those who had stopped using triptans (Figure 1). While migraineurs sometimes respond to one triptan but not others, further research may help clarify how many different triptans (of the 7 currently FDA approved) migraineurs should try before determining that they are not-responsive to triptans.Discontinued triptan subjects had a higher rate of ever using opioids in the past for migraines compared to current users. Although the current use of opioids was nearly double in those that discontinued use compared to those who continued triptan use (15% vs. 8%), given the small sample size this difference was not significant. The prevalence of medication overuse headache (MOH) was significantly higher in those who discontinued use compared to current triptan users.

While having MOH might be an indication for discontinuing a triptan, MOH was defined at the time of the survey and the discontinued triptan had been discontinued at least 6 months prior. Thus it is uncertain if MOH was present at the time of triptan discontinuation. Although the source of the MOH was not clearly delineated in this study, it is possible that the opioid-induced MOH could have rendered patients less responsive and/or more vulnerable to adverse effects from triptans, and therefore more likely to discontinue the triptan.(12) While triptans can contribute to MOH, given that those with current triptan use had less MOH, triptans were not likely the major contributor to MOH for the patients in this study. Further, although many patients often report in clinical practice not being able to refill their triptan medications frequently enough to treat all their migraines (which could contribute to MOH), less than 5% in this study reported that inability to obtain triptan refills was the top reason for triptan discontinuation (and that 5% is included in the ‘other’ category that also includes other medications work just as well and migraines became less severe.) Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, it is difficult to know if discontinuing triptans led to MOH or if patients with MOH were less likely to benefit from triptans and thus more likely to stop using them. Another possibility is that these patients are biologically predisposed to be triptan non-responders. In our study, those who discontinued triptans had higher depression and headache disability scores than those who continued use. Again, as causation is difficult to determine, it is uncertain as to whether triptan discontinuation leads to more depression and disability or if depression and disability increase the risk of triptan discontinuation. Similarly, adults who discontinued triptans had lower baseline income. Although it is feasible that the worsened impact of sub-optimal pain relief could be playing a role in one's income, the direction of causality is unknown. Furthermore, adults who discontinued triptans had lower baseline formal education than those who continued triptan use, and those who discontinued use reported receiving less formal education than those who continued to use triptans. It is difficult to assess, but interesting to consider, if one's background educational level affects the level of education a physician provides to a patient or if baseline education affects how much information a patient is receptive to receiving or comprehending.

Adding a second medication, such as an NSAID (which may increase the triptans’ efficacy) or anti-nausea medication can lead to increased headache relief, so it is interesting that those who continue to use triptans used other abortive medications with their triptans more than those who had discontinued triptan use. It is possible that the addition of a second medication increases triptan efficacy or decreases its side effects, decreasing the likelihood of triptan discontinuation. It is also possible that the recommendation of adding a second medication to the triptan could have been given with more extensive triptan education provided by a specialist. In addition to providing more detailed instructions on triptan use, another factor that may relate to the impact of specialists on triptan use is that specialists may have more time during the appointment to educate their patients. In addition, increased confidence in a specialist compared to a primary care provider who does not specialize in headache may play a role, as those who continue triptan use reported more confidence in the prescribing provider, as well as the likelihood that a specialist would use maximal triptan dosing and alternative formulations compared to other providers. While a drug that is efficacious is more likely to be continued, it is also interesting to speculate about the influence of belief, expectation, and placebo for those who find benefit from their triptans.

The results of this study indicate that appropriate triptan education may be critical for reducing triptan discontinuation: as triptans are more efficacious if taken earlier in the course of a headache, appropriate education on when to take triptans may increase the likelihood of triptan efficacy. This study showed that only half of triptan users felt triptans completely abolished their headaches more than 75% of the time and less than three quarters of triptan users felt it lessened their pain level more than seventy-five percent of the time. Thus, consistent with triptan trials and clinical observations, triptans do not have 100% consistency. If taken early in the course of a headache in conjunction with other medications, triptans can provide significant relief. Delivering this information to patients when triptans are prescribed may lead to improved medication adherence and decreased patient suffering. Conversely, once patients have tried triptans and not found them effective, it is important to look for other treatment options since the likelihood of discontinuation is high.

This study has several important limitations. It is a cross-sectional study and thus, as described, causality cannot be determined. This survey was conducted at tertiary headache centers and is reflective of such populations, with participants having an average of 10 migraine attacks/month and >40% prevalence of chronic migraine. The results may not be generalizable to headache patients in other settings. Given that patients are often referred to tertiary headache centers when they are not doing well clinically and are refractory to typical medications, the setting of this study may bias towards triptan inefficacy. As such, the findings of this study are applicable to the population we studied; future studies conducted in primary care settings are needed. This survey did not assess where participants were first evaluated for treatment of their migraine (PCP or specialist). Recall bias could differentially affect the responses from our two groups, as current triptan users were actively using their medications, but discontinued users were required to recall their use from at least 6 months prior. Additionally, the halo effect may have been present, such that migraine patients satisfied with their triptan report higher satisfaction with their provider, more education, etc. Recruiting discontinued triptan users from tertiary headache centers was difficult, likely reflecting the heavy burden of migraine in this setting. The small sample size of discontinued triptan users (69) limits the interpretation of results. The time period defining discontinued triptan users was arbitrarily set (as having used a triptan within the prior 2 years but not having used a triptan within the prior 6 months) with the intent of capturing patients who had clearly discontinued use of the triptan but who had used triptans in the recent past, therefore limiting recall bias. Nearly 1/5th of the data from respondents who completed the survey as a ‘discontinued’ triptan user was excluded because they did not meet study criteria for the time period of discontinuation. Further, given that there were no exclusions for the duration or extent of use prior to discontinuation, the participants in our study who were considered “discontinued users” did have considerable experience with triptans, making them very different from migraine patients who tried a triptan once or twice and triptans were never effective.

Conclusions

Many patients who are prescribed triptans do not continue treatment. Triptan discontinuation may result in an unnecessary burden to the migraine sufferer. In order to appropriately design educational and other interventions to prevent unnecessary triptan discontinuation, we need to understand why patients with migraines are discontinuing their use. In this study, discontinuation was highly correlated with lack of efficacy, but other important factors associated with discontinuation included higher migraine-related disability, depression, and the use of opioids for migraine attacks. Current triptan users reported receiving more education about their triptans and having better control over their migraines. Having the triptan prescribed by a specialist and taking at least one other medication with the triptan decreased the likelihood of triptan discontinuation. The results of this study suggest that rates of triptan discontinuation may be lower if patients avoid opioids and if clinicians educate their patients about the appropriate use of triptans and recommend additional abortive medications to be taken in conjunction with triptans. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot determine if these factors contributed to discontinuation or reflect the impact of such discontinuation, but targeting these factors may decrease the likelihood of triptan discontinuation and thus improve overall migraine control. Future longitudinal prospective studies in both specialty and primary care settings randomizing patients to robust or minimal education arms may delineate which factor(s) most strongly correlate with medication adherence. Determining why triptans are effective in some but not others, and why triptans become ineffective in those that previously had a response, are important questions for future research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all of the fellows of the American Headache Society Headache Fellows Research Consortium who participated in this project:

Brigham and Women's Hospital: Rebecca Erwin Wells, Rebecca Burch

Mayo Clinic Arizona: Eric Hastriter, Rashmi Halker

Mayo Clinic Minnesota: Paul G. Mathew, Beth Robertson, Hossein Ansari

Montefiore Headache Center: Alyssa Lettich, Shira Markowitz, Shiran Issa, Kate Mullin, Jelena Pavlovic

Cleveland Clinic Foundation: Eric Baron, Nancy Kelley, Brian Jenkins

Thomas Jefferson University: Brigitte Lovell, Alan Cole, Larry Charleston IV, Dolores Santamaria, Shatabdi Patel, Christina Szperka, Laura McGowan, Vitaliy Koss

University of South Florida: Kavita Kalidas, Nina Tsakadze

We would like to acknowledge all of the Program Directors of the American Headache Society Headache Fellows Research Consortium for taking on the role of Principal Investigator at their respective institutions, for overseeing the project, and for allowing their fellows to participate in this project:

Brigham and Women's Hospital: Paul Rizzoli and Elizabeth Loder

Mayo Clinic Arizona: David Dodick

Mayo Clinic Minnesota: Michael Cutrer

Montefiore Headache Center: Brian Grosberg

Cleveland Clinic Foundation: Jennifer Kriegler and Stewart Tepper

Thomas Jefferson University: Stephanie Nahas

University of South Florida: Maria Carmen Wilson

Financial Support: American Headache Society. Supported in part by a research grant from the Investigator Initiated Studies Program of Merck & Co., Inc. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck & Co., Inc

Abbreviations

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT00890357

Conflicts of Interest:

Todd Schwedt has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Headache Foundation, American Headache Society, and Merck Inc. He has participated as an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Allergan, GSK, AGA Medical, ATI, Optinose US Inc, and Arteaus Therapeutics. He has consulted for Allergan, Merck, Pfizer, Zogenix and MAP.

Joe Hentz has received research funding from Caridian BCT, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the NIH.

Kavita Kalidas:

-Nautilus neurosciences: speaker bureau

-Allergan: speaker bureau

Dr. Dodick— CONSULTING FEES/HONORARIA:

Within the past 4 years, Dr David W. Dodick serves on advisory boards, has consulted for, and received travel reimbursement from Allergan, Alder, Amgen, Pfizer, Merck, Coherex, Ferring, Neurocore, Neuralieve, Neuraxon, NuPathe Inc., MAP, SmithKlineBeecham, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Inc., Nautilus, Eli Lilly & Company, Novartis, Colucid, GlaxoSmithKline, Autonomic Technologies Inc., MAP Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Zogenix, Inc., Impax Laboratories, Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb, Nevro Corporation, Arteaus, Ethicon – Johnson & Johnson.

Dr. Halker has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Wells has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Markowitz has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Mathew has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Baron has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000 Sep 26;55(6):754–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacGregor EA, Brandes J, Eikermann A. Migraine prevalence and treatment patterns: the global Migraine and Zolmitriptan Evaluation survey. Headache. 2003 Jan;43(1):19–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland S, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Buse DC, Reed ML, Lipton RB. Rates and reasons for discontinuation of triptans and opioids in episodic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2013 Mar 15;326(1-2):10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, Diamond ML, Stewart WF. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001 Jul-Aug;41(7):638–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linde M, Jonsson P, Hedenrud T. Influence of disease features on adherence to prophylactic migraine medication. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 2008 Dec;118(6):367–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulleners WM, Whitmarsh TE, Steiner TJ. Noncompliance may render migraine prophylaxis useless, but once-daily regimens are better. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 1998 Jan;18(1):52–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1801052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Packar RC, O'Connell P. Medication compliance among headache patients. Headache. 1986 Sep;26(8):416–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1986.hed2608416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, Buse DC, Varon SF, Maglinte GA, et al. Patterns of Use and Reasons for Discontinuation of Prophylactic Medications for Episodic Migraine and Chronic Migraine: Results From the Second International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013 Apr;53(4):644–55. doi: 10.1111/head.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheftell FD, Feleppa M, Tepper SJ, Volcy M, Rapoport AM, Bigal ME. Patterns of use of triptans and reasons for switching them in a tertiary care migraine population. Headache. 2004 Jul-Aug;44(7):661–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland S, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Buse DC, Reed ML, Lipton RB. Rates and reasons for discontinuation of triptans and opioids in episodic migraine: Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2013 Feb 7; doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cady RK, Maizels M, Reeves DL, Levinson DM, Evans JK. Predictors of adherence to triptans: factors of sustained vs lapsed users. Headache. 2009 Mar;49(3):386–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho TW, Rodgers A, Bigal ME. Impact of recent prior opioid use on rizatriptan efficacy. A post hoc pooled analysis. Headache. 2009 Mar;49(3):395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]