Abstract

Rotavirus (RV) and norovirus (NoV) are the two most important causes of viral gastroenteritis. While vaccine remains an effective prophylactic strategy, development of other approaches, such as passive immunization to control and treat clinical infection and illness of the two pathogens, is necessary. Previously we demonstrated that high titers of NoV-specific IgY were readily developed by immunization of chickens with the NoV P particles. In this study, we developed a dual IgY against both RV and NoV through immunization of chickens with a divalent vaccine comprising neutralizing antigens of both RV and NoV. This divalent vaccine, named P-VP8* particle, is made of the NoV P particle as a carrier with the RV spike protein VP8* as a surface insertion. Approximately 45 mg of IgY were readily obtained from each yolk with high titers of anti-P particle and anti-VP8* antibodies detected by ELISA, Western blot, HBGA blocking (NoV and RV) and neutralization (RV) assays. Reductions of RV replication were observed with viruses treated with the IgY before and after inoculation into cells, suggesting an application of the IgY as both prophylactic and a therapeutic treatment. Collectively, our data suggested that the P-VP8* based IgY could serve as a practical approach against both NoV and RV.

Keywords: rotavirus, norovirus, diarrhea, immunoglobulin Y (IgY), passive immunization

1. Introduction

Acute gastroenteritis is an important disease with high morbidity and mortality in children and the elderly. Each year approximately 1.76 million children die from gastroenteritis in the developing countries (Glass et al., 2001). In developed countries, while deaths from diarrhea are less common, severe illness often leads to hospitalization or doctor visits. Among different bacterial and viral pathogens causing acute gastroenteritis, rotaviruses (RVs) and noroviruses (NoVs) are the two most important ones. RVs cause severe diarrhea in infants and young children under five years of age leading to ~453,000 deaths every year (Parashar et al., 2003; Tate et al., 2012). On the other hand, NoVs usually lead to large outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis in all age groups in both developing and developed countries (Glass et al., 2009).

Currently there is no antiviral or vaccine available for NoVs. While the two recently introduced RV vaccines (RotaTeq® Merck & Co., Inc. and Rotarix® GSK Biologicals) are effective, low protection efficacy to children in the African and Asian counties were reported (Patel et al., 2009; Widdowson et al., 2009). In addition, both RVs and NoVs cause severe illnesses in children and/or the elderly and infect persistently immune compromised patients (Patel et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2011). Thus, additional strategies to control and prevent clinical infection of the two viruses are highly demanded.

Antibody-based passive immunization is effective in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases (Keller and Stiehm, 2000), in which the availability of large amount of specific antibodies is the key. Immunoglobulin Y (IgY), the egg yolk antibodies generated as a passive immunity to embryos and baby chicks(Patterson et al., 1962), can be a good source of such antibody. IgY can be easily produced and purified with high yields from egg yolks of immunized hens by variable methods, which has been used as a safe and inexpensive strategy to control and prevent bacterial and viral infections in domestic farm animals (Chalghoumi et al., 2009b; Vega et al., 2011). However, the possibility of using IgY to fight against RV and NoV infection in humans has not yet been studied.

We started to explore this option by producing a large amount of NoV specific IgY using the NoV P particles as the antigens (Dai et al., 2012). This approach takes advantage of the high immunogenicity and high efficient and low cost production of the P particles (Tan et al., 2008), which resulted in production of high titers of IgY against NoVs (Dai et al., 2012). In this study, we further produced IgY with dual effects against both RVs and NoVs using the novel NoV/RV P-VP8* chimeric particle (Tan et al., 2011) as antigens. We were successful in demonstrating high titers of specific IgY in egg yolks of immunized chickens and showing neutralization on RVs and NoVs. Our results laid a solid foundation for future prophylactic and therapeutic treatments against both NoVs and RVs.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Antigen preparation

Recombinant chimeric P-VP8* particles (Tan et al., 2011), VP8* (BM13851 core VP8*) (Huang et al., 2012) and the P particle of VA387 were expressed in E. coli (BL21, DE3) with an induction of 0.6 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at room temperature (22°C) overnight as described previously (Huang et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2011). Purification of the recombinant GST fusion proteins was carried out by using resin of Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare life Sciences, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. GST was removed from the target proteins by thrombin (GE Healthcare life Sciences, NJ, USA) cleavage on bead at room temperature overnight.

2.2 Chickens and immunization

Six-week old specific pathogen free white leghorn chicks were purchased from Charles River Vendor, Wilmington, MA, USA. Chicks were housed in separate cages in the pathogen free animal facilities at the Veterinary service department of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center under a regimen of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness, at room temperature (23 ± 2°C) and humidity of 75 ± 5%. Water and commercial food were offered daily. The chickens were immunized with three different viral antigens (P-VP8*, VP8* and P particle) at 21 weeks old with 2 animals per antigen group. For the first dose of immunization, 300 µg of purified P-VP8* particles with Imject Alum Adjuvant (Invitrogen Life Technologies Carlsbad, CA) (3:1, volume: volume) were administered intramuscularly on multiple locations of pectoral muscles. Estimated equal molar amounts of 100 µg of VP8* and 200 µg of P particles were used as controls. The 2nd and 3rd immunizations used half amounts of antigens as that of the first doses for each antigen at a two-week interval. Animals were bled from the wing vein before and after each immunization to determine antibody responses to the viral antigens. Eggs were collected daily and stored at 4 °C before being processed for IgY. Chickens were euthanized at 31 weeks-old, 11 weeks after the first immunization. This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation (Animal Welfare Assurance No. 1D06055).

2.3 Concentration of IgY from chicken eggs

Egg yolks were processed to concentrate IgY using polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000, Sigma, St. Louis, USA) precipitation method (Pauly et al., 2011) with modifications. Briefly, egg yolks were mixed with three volumes of PBS (pH 7.4) before adding PEG 8000 to a final concentration of 3.5%. After vortex and 20 min of rolling on a rolling mixer, the sample mixtures were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to remove the precipitated debris. The supernatant was then adjusted to 8.5% PEG 8000 and centrifuged again after incubation for 15 min at room temperature. The precipitated pellets that contained IgY were dissolved in 10 ml PBS and then precipitated again with 12% of PEG 8000 and pelleted using the same procedures described above. The final precipitated pellets was dissolved in 2.0 ml PBS and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter and stored at −20°C. The purity of the IgY preps was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Coomassie blue staining. Total IgY in each yolk were calculated based on a procedure described in our previous study (Dai et al., 2012).

2.4 Detection of NoV and RV specific IgY in sera and yolks by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA was used to determine antibody titers against P particle and VP8* in sera and yolks of the chickens after immunization with individual antigens described above. Purified VA387 P particle and free VP8* were used as the capture antigens in the assays (Tan et al., 2011). In brief, ninety-six well microtiter plates (Dynex Immulon; Dynatech, Franklin, MA, USA) were coated with 100 µl antigens (1 µg/ml) at 4°C overnight. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in PBS (pH 7.4), serial dilutions of chicken serum samples and concentrated IgY samples were added to the plates. The bound antibody was then detected by goat anti-chicken IgY-HRP (1:5000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The signal intensity was measured at 450 nm using a micro-plate reader (DTX 880 Multimode Reader, Beckman Coulter, GmbH, Krefeld, Germany) after adding substrate reagent (BD OptEIA TMB Substrate Reagent Set, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Pre-immunized chicken sera and yolk IgY were used as negative controls. Antigen-specific antibody titers were defined as the endpoint dilution with a cut off signal intensity of OD450 value at 0.2.

2.5 Characterization of IgY by Western-blot analysis

Specific reactions of the chicken IgY with NoV capsid protein and RV VP8* protein were examined by Western-blot analysis. Following SDS-PAGE, VA387 NoV virus-like particles (VLPs) and RV VP8* in the gels were transferred onto a nitrocellulose before being detected by IgY from different chickens immunized with P-VP8*, VP8* and P particle respectively (2000-fold dilution in 1% nonfat dry milk in PBS). The bound IgY antibodies were then detected by a peroxidase-conjugate goat anti-chicken IgY (5000-fold dilution in 1% nonfat dry milk in PBS) followed by detection with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, England). The ECL signals were captured by Hyper film ECL (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, England).

2.6 Blocking of binding of NoV P particles to type A and type B saliva

The saliva-based binding and blocking assays were performed as described previously (Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012). Briefly, boiled human type A or type B saliva were diluted 1000-fold and coated on 96-well microtiter plates. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in PBS, P particle (125 ng/ml) of the VA387 NoV was added. For the blocking effects of IgY, a pre-incubation of P particle with IgY in serial dilution for 1 hour at 37°C was performed before the P particle was added to the saliva coated plates. Bound P particles were then detected by a guinea pig anti-VA387 antiserum (1:3333) followed by the addition of HRP-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (1:5000). The blocking rates were calculated by comparing the optical densities (ODs) measured with and without blocking by chicken IgYs.

2.7 Blocking of binding of RV VP8* to saliva Leb and oligosaccharide H type 1

The blocking assay on RV VP8* binding to HBGA was performed based on procedures described in previous studies (Huang et al., 2012). In brief, boiled saliva from Leb positive donors were diluted 1,000-fold and coated onto 96-well plates at 4°C overnight. The testing IgY were pre-incubated with BM 13851 full-VP8* at 37°C for 1 h before being transferred to the coated plates. The bound VP8* proteins were then detected using a guinea pig anti-BM151 VP8* antibody at 1:3,000, followed by addition of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG at 1:5000 (ICN, Aurora, OH). The blocking rate (%) was calculated by comparing the OD450 values between wells with or without incubation with IgY.

The blocking of RV VP8* binding to H type 1 oligosaccharides by IgY antibodies were performed using the same protocol described above except a H type 1-PAA-biotin conjugate (2 µg/ml, GlycoTech, Rockville, MD) with streptavidin (5 µg/ml) was used as the capture antigens (Huang et al., 2012).

2.8 Inhibition of RV replication in cell culture by IgY antibodies

The abilities of IgY in inhibition of RV replication in MA104 cells were studied by incubation of RV with IgY before (prophylactic) or after (therapeutic) inoculation of the viruses to the host cells. For prophylactic treatment, trypsin treated RVs (MOI 0.01) were pre-incubated with IgY at variable dilutions for 1 h before being inoculated to the cells. For therapeutic treatment, IgY was added to the culture after two hours of incubation with RV at a 0.01 MOI on 80–90% confluent MA104 cells. Viral replications in the IgY treated and untreated cells were then monitored by immunofluorescent staining, plaque assay and CPE.

MA104 cells were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. A cell culture-adapted P [8] Wa RV was used as the testing virus.

For immunofluorescent staining, the cells were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4), and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min and incubated in PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin for 30 min. Then cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with guinea pig antibody against rotavirus VP8* protein diluted at 1:300. Then, cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with FITC-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG antibody (Santa Cruz) diluted at 1:300 in PBS. Between each step, Cells were washed three times with PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Tween). Finally, nuclei were counter stained with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI. The fluorescent signals were visualized under a fluorescence microscope.

For plaque assay, the plates were washed and then overlaid with DMEM containing 0.75% Seaplaque® agarose with 5 µg/ml trypsin. After 4 days incubation at 37°C, the plaques in each well were stained with crystal violet and counted. IgY induced by P particles was set as control. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of IgY induced by P-VP8* or free VP8* against rotavirus was calculated by using probit regression analysis by using SPSS statistical software version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

For detection of CPE, the cells were observed by light microscopy and scored at 96 h post infection. We also performed Western-blot analysis on cells with typical CPE. Briefly, total cell proteins were extracted (Gauthier et al., 2011), separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking overnight with 5% non-fat milk, the membranes were incubated with guinea pig anti-BM13851 antibody (1:2000) or rabbit anti-β-actin antibody (1:2000) as internal control for 1 h at RT. Then the membranes were washed and incubated with corresponding HRP-labeled secondary antibody (1:5000) for 1 h. The bound HRP was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagents and were captured by Hyper film ECL.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Graphs were made using Microsoft Office Excel 2010 and the p-values were determined by student t test among data groups and the difference is considered as significant as a p-value <0.05, using SPSS software 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

3. Results

3.1 Production and purification of chicken IgY against P-VP8*

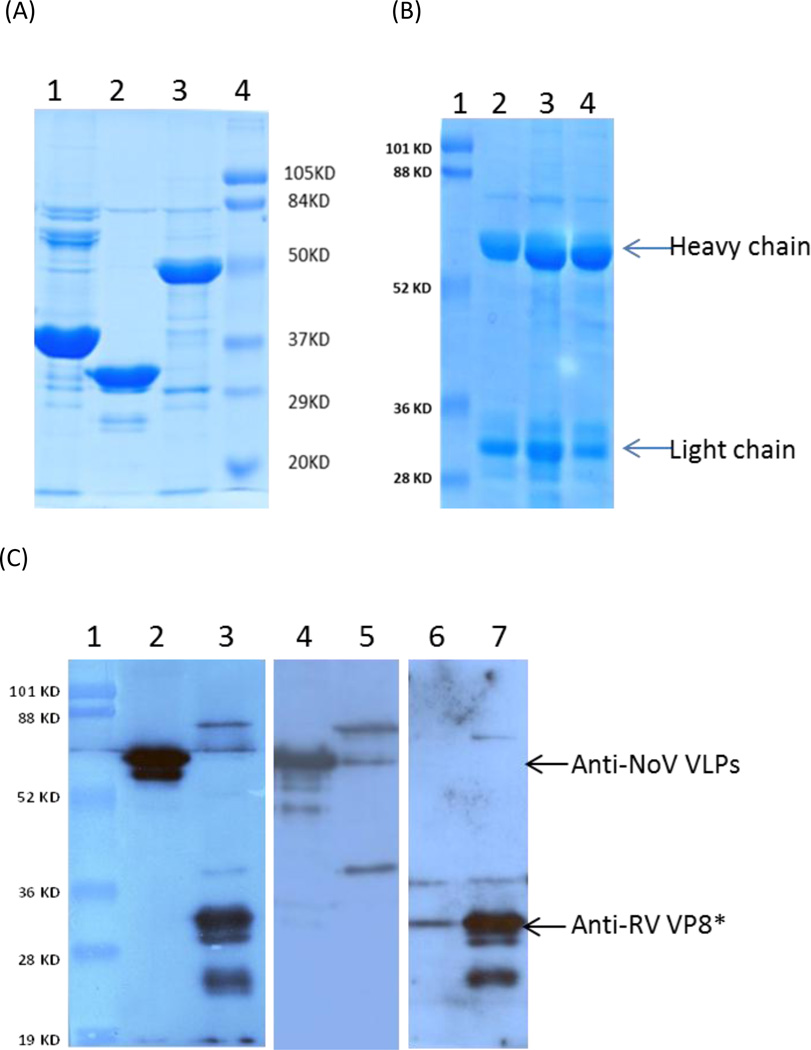

Recombinant NoV P particles (Tan et al., 2008), RV VP8* (Huang et al., 2012) as well as the chimeric P-VP8* particles (Tan et al., 2011) were expressed in E. coli at yield >5 mg/liter bacteria (Fig. 1A). The three purified antigens were immunized to Leghorn chickens. Eggs collected at variable time points post immunization were examined for total as well as NoV- and RV-specific IgY antibodies following a three-step IgY purification. IgY from each egg yolk (~15 ml) was concentrated to ~2 ml by PEG precipitation with an estimated yield of 21–27 mg IgY/ml yolk. This means that 40–50 mg of total IgY can be obtained from a single egg. The concentrated IgY revealed a major band of ~68 kDa (heavy chain) and a minor band of ~28 kDa (light chain) of immunoglobulins in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Production and analysis of IgY induced by chimeric NoV P particle containing RV VP8* (P-VP8*), P particle and free VP8*. (A) SDS-PAGE gel of antigens used for IgY production. Recombinant proteins were expressed and purified from E. coli. Lane 1: P particles of NoV (VA387 strain); lane 2: core VP8* of RV BM13851 strain; lane 3: P particle containing RV VP8* (P-VP8*); lane 4: molecular marker. (B) SDS-PAGE gel of purified IgY from egg yolks. IgY was concentrated from egg yolks using a 3-step PEG precipitation followed with filtered through a 0.45 µM filter. Two major protein bands with molecular weights of 68kDa and 27KDa, respectively, were detected which represent the heavy and light chains of IgY (arrows). Lane 1: moleculare weight marker; lane 2: IgY induced by P particle; lane 3: IgY induced by free VP8*; lane 4: IgY induced by P-VP8*. (C) Specificity of IgY by Western-blot analysis. NoV VLPs and RV VP8* were electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions before transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane in triplicates. The proteins on the membrane were probed with IgYs induced by P-VP8* (lane 2, 3), P particle (lane 4, 5), and free VP8* (lane 6, 7). All IgYs were diluted at 1:2000.

3.2 Dynamics of anti-RV and anti-NoV IgY antibodies in the sera of chickens and egg yolks

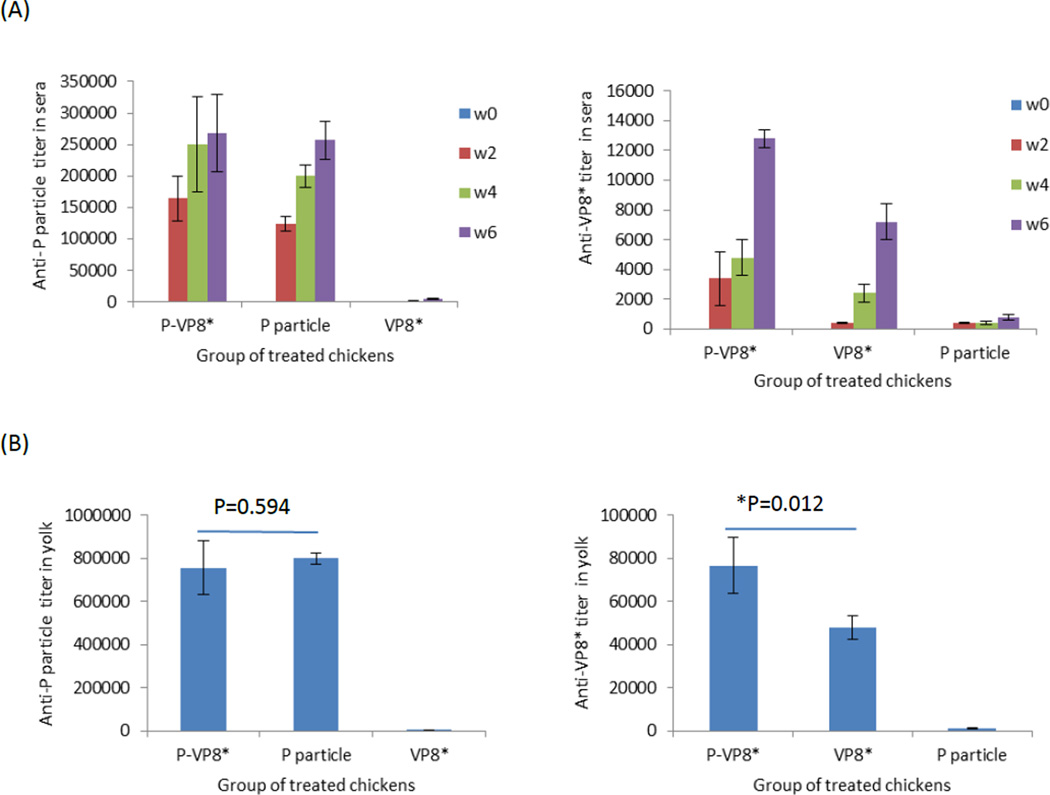

Steady increases of anti-NoV antibodies were observed in the sera of chickens from weeks 2 to 6 after the first immunization, with peak titers of ~250,000 in both chicken groups immunized with the P-VP8* and P particles, respectively. No anti-NoV antibody was detected in chickens immunized with the free VP8* antigen. Similar dynamics of RV VP8*-specific IgY titers were also observed, with peak titers of 12,800 in the P-VP8* immunization group and 7,200 in the free VP8* immunization group. No VP8* antibody was seen in the P particle immunization group (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Antibody responses of chickens in sera and egg yolks after immunization with different NoV and RV antigens. Three groups of chicken (n = 2 in each group) were immunized with P-VP8*, P particle and free VP8*, respectively, with Alum adjuvant (3:1). NoV VA387 P particle and RV free VP8* were used as the capture antigens for detection of specific antibodies by EIA. (A) Antibody responses in sera at different times (weeks 0 to 6) following immunization of the three antigens. w0: before the first dose of immunization; w2, 4, and 6: two, four, six weeks after the 1st dose of immunization. (B) Antibody titers of PEG concentrated IgY. Egg yolks harvested in 6th – 11th weeks after the first dose of immunization were pooled and concentrated for IgY by the three-step PEG precipitation method. The titers of IgY against P particle or VP8* were determined. * P < 0.05.

The P domain- and VP8*-specific antibodies in the egg yolks also increased steadily starting at week 3 after the first immunization, and maintained at a high level toward 11th week (data not shown), which is in accordance with our previous study (Dai et al., 2012). Similar high titers of anti-P domain IgY antibodies (750,000–800,000) were observed in the egg yolks of both P-VP8*- and P particle-immunization groups. However, the anti-VP8* antibody titers (~ 80,000) in egg yolks of P-VP8*-immunized chickens were significantly higher than those of egg yolks of chickens receiving the free VP8* (~ 48,000) (Fig. 2B). Hence, the chimeric P-VP8* particle is capable of inducing high titers of IgY against both NoVs and RVs.

The specificities of anti-NoV and anti-RV IgY antibodies were also confirmed by Western blotting analysis. The IgY induced by the P-VP8* chimera reacted to both NoV VLP and RV VP8*, while IgY induced by P particles reacted to NoV VLP only and IgY induced by VP8* reacted to RV VP8* only (Fig. 1C).

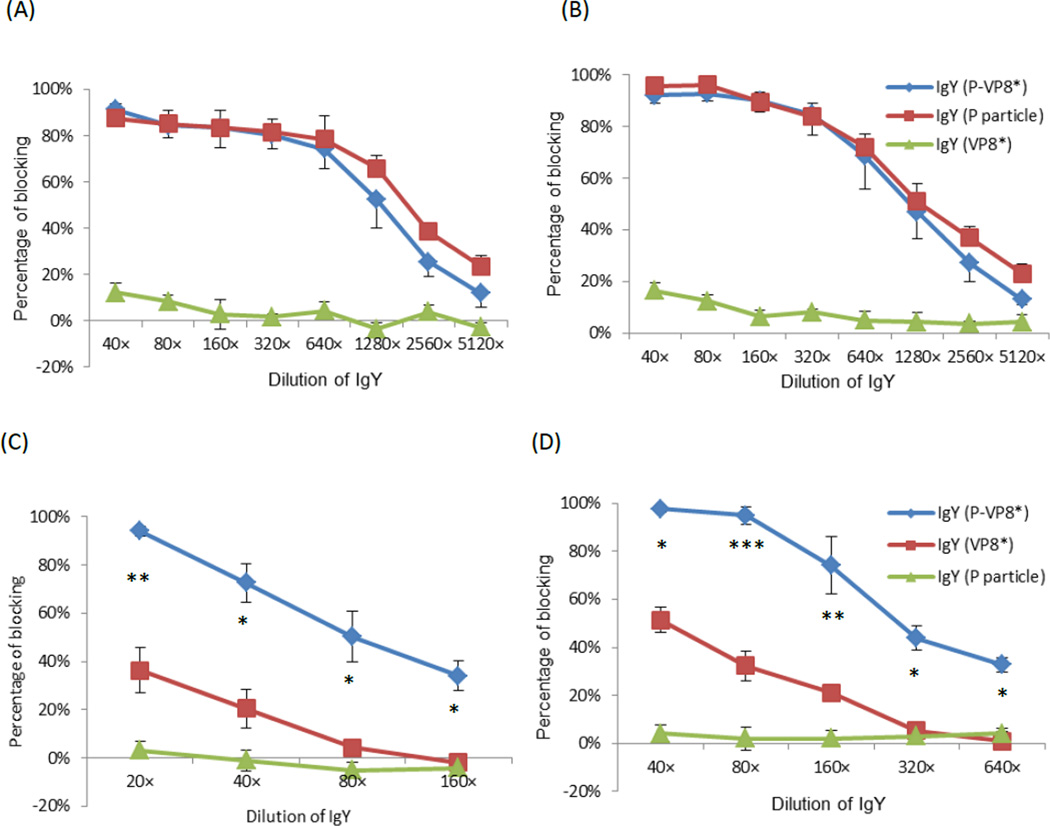

3.3 IgY induced by chimeric P-VP8* particle blocked NoVs and RVs binding to HBGAs

To evaluate the usefulness of the chicken IgY as a potential therapeutic and/or prophylactic treatments against NoV and RV diseases, we performed neutralization assays against NoVs and RVs. Since NoVs still cannot be cultivated in vitro, we performed a HBGA blocking assay as a surrogate neutralization test. As demonstrated in Fig. 3A and 3B, the P-VP8*-induced IgY strongly blocked the VA387 P particles binding to the type A saliva with a BT50 of 1:1,300 and a BT50 of 1:1,200 to type B saliva. These blockages were similar to that of the P particle-induced IgY. As expected, no detectable blockage was found from the VP8* induced IgY.

Fig. 3.

Blocking of IgY against NoV P particle and RV VP8* binding to specific HBGAs. The abilities of IgY blocking NoV P particle binding to the types A (A) and type B (B) saliva and RV VP8* binding to the Leb saliva (C) and H type 1 oligosaccharide (D) were measured. IgY induced by P-VP8* or P particle blocked binding of NoV P particle to types A and B saliva, while IgY induced by free VP8* did not show this blockade. IgY induced by P-VP8* or free VP8* blocked binding of RV VP8* to Leb saliva and H type 1 oligosaccharide, while IgY induced by P particle did not show this blockade. Asterisks indicate statistical P values between blocking levels of IgY induced by the two forms of VP8* (P-VP8* vs. free VP8*), * P< 0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

We recently discovered that human RVs also recognize human HBGAs like the human NoVs (Huang et al., 2012). RV VP8*-HBGA blocking assay showed that the P-VP8* induced IgY blocked the RV VP8* binding to Leb positive saliva with a BT50 of ~1:80 and to H type 1 oligosaccharide with a BT50 of ~1:240. This was significantly higher than that of the free VP8*-induced IgY (P<0.05). No detectable blockage was found from IgY induced by P particles (Fig. 3C and 3D). These results suggested that the anti-P-VP8* IgY could influence RV attaching to host cells by blocking RV binding to its HBGA ligands.

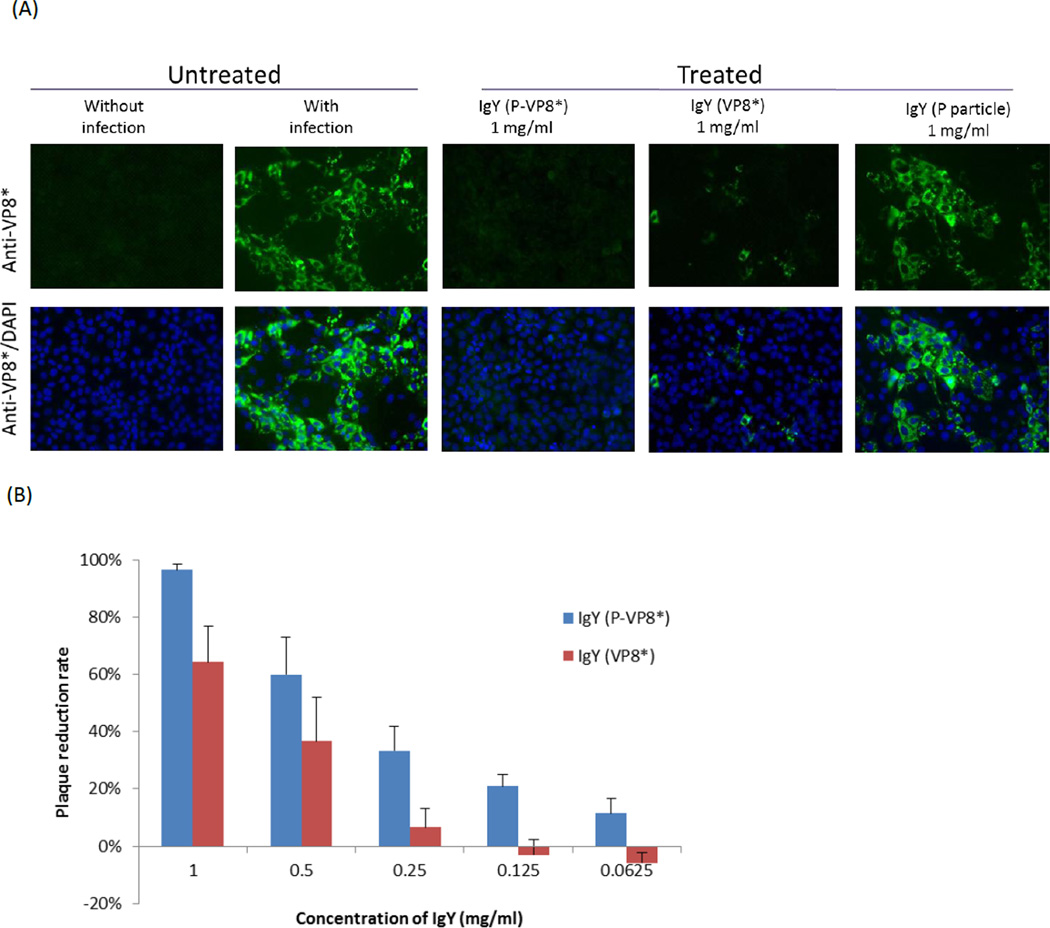

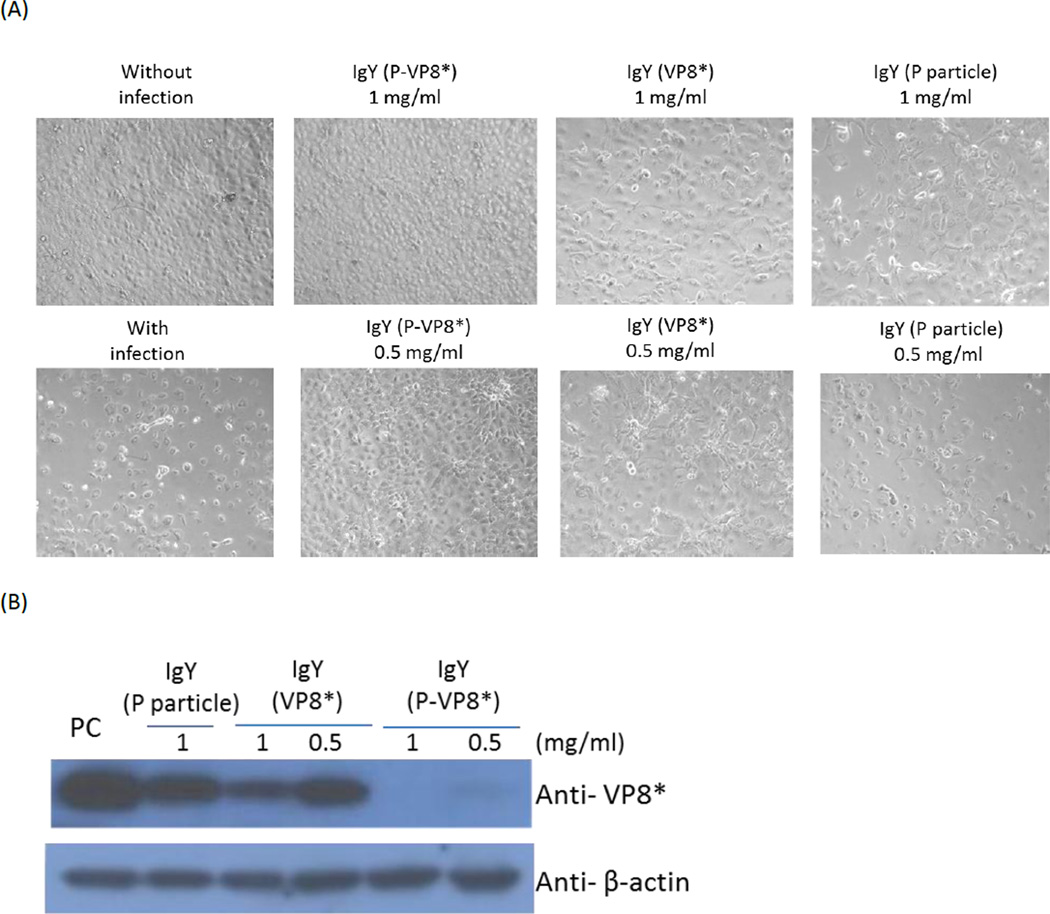

3.4 Neutralization of RV replication by IgY

The usefulness of IgYs was further evaluated by RV neutralization assays mimicking pre- and post-infection treatments of RV by IgY. A treatment of RVs with P-VP8*-induced IgY (1 mg/ml) before inoculating the cells blocked RV replication in MA104 cells completely. In contrast, a treatment of IgY induced by the free VP8* resulted in only partial block of RV replication, while IgY induced by P particles did not show neutralization effect (Fig. 4A). These results were confirmed by plaque reduction assay, in which the IgY induced by P-VP8* and VP8* inhibited Wa replication in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). The inhibition effects of IgY induced by P-VP8* were significantly stronger (with an IC50 of 0.304 mg/ml) than that of IgY induced by the free VP8* (with an IC50 of 0.734 mg/ml) (P<0.05). Interestingly, a post inoculation treatment of RV by the P-VP8*-induced IgY (1 or 0.5 mg/ml) also inhibited CPE completely (Fig. 5A). As expected the neutralization effect by the free VP8* induced IgY was slightly weaker, while ≥80% CPE was seen in Wa infected cultures without IgY treatment or treated with IgY induced by NoV P particles.

Fig. 4.

Neutralization of RV replication by pre-incubation with specific IgY as a prophylactic treatment. (A) Neutralization measured by immunofluorescence assay. MA104 cells 80–90% confluence on 4-well chamber slides were used. RV at 0.01 MOI were incubated with IgY at 1 mg/ml at RT for 1 h before inoculated to the MA104 culture. The cell monolayers were stained with an anti-VP8* antibody followed by a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Significant reductions of RV replication were observed in RV treated with IgY induced by P-VP8*, medium reduction withIgY induced by free VP8*, but no reduction with IgY induced P particle. (B) Neutralization measured by plaque reduction. MA104 cells were cultivated in 6-well plates and infected with RV at 50–100 PFU/well with a preincubation with IgY for 1h. The IgY induced by NoV P particle was used as negative control. The plaque reduction results were calculated from three independent experiments.

Fig. 5.

Neutralization of RV replication by post-incubation with IgY as a therapeutic treatment. MA104 cells infected with RV at 0.01 MOI at 80–90% confluence in 6-well plates. After 2 hours of incubation, the virus inoculation was replaced with a medium containing 0.5 – 1 mg/ml IgY. CPEs were examined at 96 h (A) and the infected cell culture was harvested for Western-blot assay (PC: with Wa infection but without IgY treatment) (B).

The viral neutralization results were also confirmed by Western blot analysis. Viral proteins were detected in group treated with P-VP8* specific IgY at 1 and 0.5 mg/ml, while less viral proteins were detected in group treated with VP8* induced IgY at 1 mg/ml (Fig. 5B), confirming the observation of the CPE experiments.

4. Discussion

In recent years, pathogen-specific IgY has drawn a special attention in passive immunization of humans against infectious diseases due to a number of advantages. Firstly, IgY derived from egg yolks of immunized chickens has shown to be beneficial to animal welfare, safe and no drug resistance issues. Secondly, different methods are suitable to isolate IgY from egg yolks in large scale. In this study, we used a new procedure to concentrate IgY from egg yolks through a three-step PEG precipitation. This improved procedure is simple, efficient and suitable for large-scale production although the yield may be slightly lower compared with the water dilution extraction methods. An average of 45 mg of IgY/yolk was readily obtained in the NoV/RV antibody production period starting at the 6th week following the first immunization. An adult leghorn chicken produce normally 280 eggs a year with a total 13,000 mg IgY for an egg production year with continuous antigen boost every 3–4 months.

Thirdly, IgY is stable at a wide ranges of pHs and temperatures and resistant to pepsin digestion (Chalghoumi et al., 2009a; Dai et al., 2012), making IgY an ideal treatment to control infections of intestinal pathogens. Promising examples of IgY treatment of infectious diseases have be demonstrated by orally delivering microcapsule protected IgY (Kovacs-Nolan and Mine, 2005; Li et al., 2009). While the usefulness of IgY is still underestimated, several studies showed promising results on the possible prophylactic and therapeutic treatment against different viral infections, including EV71 (Liou et al., 2010), influenza A and B (Nguyen et al., 2010; Wallach et al., 2011; Wen et al., 2012), HAV (de Paula et al., 2011) and RV infection (Kovacs-Nolan et al., 2003). Importantly, these studies provided evidence on the effectiveness of chicken IgY against mucosal pathogens, particularly those causing infection in the intestine.

The NoV P particle spontaneously forms when the protruding (P) domain of the NoV capsid protein, the surface antigen of NoV, is expressed in E. coli. The NoV P particle retains the authentic receptor binding property, is stable and easily purified (Tan and Jiang, 2005; Tan and Jiang, 2012). Because of these properties, NoV P particle has been proposed as a candidate vaccine against NoVs. Our previous study also produced a large amount of NoV specific IgY by using NoV P particles as the antigens (Dai et al., 2012). Recently the NoV P particle has been developed as an excellent vaccine platform (Tan and Jiang, 2012; Xia et al., 2011). By inserting the RV surface spike protein VP8* on to a surface loop of the NoV P particle, we previously showed that the chimeric particle P-VP8* is a promising dual vaccine against both NoVs and RVs due to its high immunogenicity, high yield and high stability in comparison with free VP8* (Tan et al., 2011). Free VP8* was unstable for long-term storage (data not shown).

In this study, we successfully produced a large amount of specific IgY against human NoVs and RVs by immunizing juvenile chickens with the chimeric P-VP8* particles (Tan et al., 2011). To examine the dual immunity against NoVs and RVs, we also used viral antigens of RV (VP8*) and NoV (P particle) as controls. The P-VP8* specific antibody was detected at the second week in sera and 4th week in yolks after the first immunization, which is similar to that observed in our previous study using the NoV P particles as antigen (Dai et al., 2012). In chickens immunized with the P-VP8* particles, the antibody titers specific to the NoV P domain, the backbone of the P-VP8* particle, were comparable to that of chickens received the NoV P particle alone; but the antibody titers against the RV VP8* were significantly higher than that of chickens received the free VP8* antigen alone. These data also supported the notion that the P-VP8* particle is an effective dual vaccine against both NoVs and RVs (Tan et al., 2011).

NoVs encode a major capsid protein that is important for host interaction and immune response. Due to the lack of a cell culture and an efficient small animal model, a surrogate neutralization assay to measure the ability of antibody blocking NoV binding to HBGA receptors is used (Nurminen et al., 2011; Reeck et al., 2010). In this study, we demonstrated that the IgY induced by the P-VP8* particle is able to block NoV binding to HBGA receptors, suggesting that this IgY may be useful in control of NoV infection.

RVs contain two major surface structural proteins, VP4 and VP7, which are involved in RV neutralization. The VP4 is cleaved into two domains by the viral protease, the VP5* and VP8*. Recently, we and others have demonstrated that the spike protein VP8* recognize the human HBGAs as receptors or attachment ligands, similar to that of the P domain of NoVs (Hu et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012). In this study, the IgY induced by the P-VP8* particles was able to block RV binding to specific HBGAs (Leb or H type 1) as well as neutralize RV replication in cell cultures, supporting the notion that RVs may recognize human HBGAs. We also confirmed the neutralization by both pre- and post-infection treatments, providing further evidence that the P-VP8* induced IgY could be used as an effective prophylactic and therapeutic treatment against NoV and RV infections.

A potential usefulness of the P-VP8* based IgY is to control clinical infection of RV and NV in children during the peak seasons as both RVs and NoVs have a similar spring-fall season. Thus, a readily available treatment such as oral administration of the dual IgY antibody could be practical to control the clinical infection of both NoVs and RVs. In addition, it would be useful for prophylactic treatment of children and other high-risk populations during the peak seasons, such as the elderly and immunocompromised patients, whose immunity may be weakened (Patel et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2011). A passive immunization would be particularly important to control persistent infections with NoVs or RVs in severely immunocompromised patients. Thus, because of the value of dual functions against both NoVs and RVs, future study for further development of the approach is warrant.

Highlights.

IgY against both RV and NoV were produced by immunizing chickens with a dual vaccine candidate P-VP8*.

The resulting IgY blocked RV and NoV binding to their HBGA receptors.

The IgY is also able to neutralize RV replication in cell culture condition.

The P-VP8* based IgY is a promising approach for passive immunization against both RV and NoV.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health of the United States (R01 AI 055649, R01 AI 37093, R01 AI089634 and P01 HD 13021) and the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program of the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, NIFA Award No: 2011-68003-30005; Guangdong Province ‘211 Project’ and Grant from School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine (GW201233) of Southern Medical University and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30901992).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chalghoumi R, Beckers Y, Portetelle D, Thewis A. Hen egg yolk antibodies (IgY), production and use for passive immunization against bacterial enteric infections in chicken: a review. Biotechnol Agron Soc. 2009a;13:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Chalghoumi R, Marcq C, Thewis A, Portetelle D, Beckers Y. Effects of feed supplementation with specific hen egg yolk antibody (immunoglobin Y) on Salmonella species cecal colonization and growth performances of challenged broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 2009b;88:2081–2092. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai YC, Wang YY, Zhang XF, Tan M, Xia M, Wu XB, Jiang X, Nie J. Evaluation of anti-norovirus IgY from egg yolk of chickens immunized with norovirus P particles. J Virol Methods. 2012;186:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paula VS, da Silva Ados S, de Vasconcelos GA, Iff ET, Silva ME, Kappel LA, Cruz PB, Pinto MA. Applied biotechnology for production of immunoglobulin Y specific to hepatitis A virus. J Virol Methods. 2011;171:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier MS, O'Brien EL, Bigornia S, Mott M, Cacicedo JM, Xu XJ, Gokce N, Apovian C, Ruderman N. Decreased AMP-activated protein kinase activity is associated with increased inflammation in visceral adipose tissue and with whole-body insulin resistance in morbidly obese humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass RI, Bresee J, Jiang B, Gentsch J, Ando T, Fankhauser R, Noel J, Parashar U, Rosen B, Monroe SS. Gastroenteritis viruses: an overview. Novartis Found Symp. 2001;238:5–19. doi: 10.1002/0470846534.ch2. discussion 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1776–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Crawford SE, Czako R, Cortes-Penfield NW, Smith DF, Le Pendu J, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Cell attachment protein VP8* of a human rotavirus specifically interacts with A-type histo-blood group antigen. Nature. 2012;485:256–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Farkas T, Marionneau S, Zhong W, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Morrow AL, Altaye M, Pickering LK, Newburg DS, LePendu J, Jiang X. Noroviruses bind to human ABO, Lewis, and secretor histo-blood group antigens: identification of 4 distinct strain-specific patterns. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:19–31. doi: 10.1086/375742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Farkas T, Zhong W, Tan M, Thornton S, Morrow AL, Jiang X. Norovirus and histo-blood group antigens: demonstration of a wide spectrum of strain specificities and classification of two major binding groups among multiple binding patterns. J Virol. 2005;79:6714–6722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6714-6722.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Xia M, Tan M, Zhong W, Wei C, Wang L, Morrow A, Jiang X. Spike Protein VP8* of Human Rotavirus Recognizes Histo-Blood Group Antigens in a Type-Specific Manner. J Virol. 2012;86:4833–4843. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05507-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MA, Stiehm ER. Passive immunity in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:602–614. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.602-614.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Nolan J, Mine Y. Microencapsulation for the gastric passage and controlled intestinal release of immunoglobulin Y. J Immunol Methods. 2005;296:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Nolan J, Yoo D, Mine Y. Fine mapping of sequential neutralization epitopes on the subunit protein VP8 of human rotavirus. Biochem J. 2003;376:269–275. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XY, Jin LJ, Uzonna JE, Li SY, Liu JJ, Li HQ, Lu YN, Zhen YH, Xu YP. Chitosan-alginate microcapsules for oral delivery of egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY): in vivo evaluation in a pig model of enteric colibacillosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;129:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou JF, Chang CW, Tailiu JJ, Yu CK, Lei HY, Chen LR, Tai C. Passive protection effect of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins on enterovirus 71 infected mice. Vaccine. 2010;28:8189–8196. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, Tumpey TM, Park HJ, Byun YH, Tran LD, Nguyen VD, Kilgore PE, Czerkinsky C, Katz JM, Seong BL, Song JM, Kim YB, Do HT, Nguyen T, Nguyen CV. Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of avian antibodies against influenza virus H5N1 and H1N1 in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurminen K, Blazevic V, Huhti L, Rasanen S, Koho T, Hytonen VP, Vesikari T. Prevalence of norovirus GII-4 antibodies in Finnish children. J Med Virol. 2011;83:525–531. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, Miller MA, Glass RI. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:565–572. doi: 10.3201/eid0905.020562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Shane AL, Parashar UD, Jiang B, Gentsch JR, Glass RI. Oral rotavirus vaccines: how well will they work where they are needed most? J Infect Dis. 2009;200(Suppl 1):S39–S48. doi: 10.1086/605035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NC, Hertel PM, Estes MK, de la Morena M, Petru AM, Noroski LM, Revell PA, Hanson IC, Paul ME, Rosenblatt HM, Abramson SL. Vaccine-acquired rotavirus in infants with severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:314–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson R, Youngner JS, Weigle WO, Dixon FJ. Antibody production and transfer to egg yolk in chickens. J Immunol. 1962;89:272–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly D, Chacana PA, Calzado EG, Brembs B, Schade R. IgY technology: extraction of chicken antibodies from egg yolk by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation. J Vis Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeck A, Kavanagh O, Estes MK, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Graham DY, Atmar RL. Serological correlate of protection against norovirus-induced gastroenteritis. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1212–1218. doi: 10.1086/656364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Vergoulidou M, Schreier E, Loddenkemper C, Reinwald M, Schmidt-Hieber M, Flegel WA, Thiel E, Schneider T. Norovirus gastroenteritis causes severe and lethal complications after chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:5850–5856. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Fang P, Chachiyo T, Xia M, Huang P, Fang Z, Jiang W, Jiang X. Noroviral P particle: structure, function and applications in virus-host interaction. Virology. 2008;382:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Huang P, Xia M, Fang PA, Zhong W, McNeal M, Wei C, Jiang W, Jiang X. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. J Virol. 2011;85:753–764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01835-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:14017–14030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14017-14030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Jiang X. Norovirus P particle, a subviral nanoparticle for vaccine development against norovirus, rotavirus and influenza virus. Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1–9. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:136–141. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega C, Bok M, Chacana P, Saif L, Fernandez F, Parreno V. Egg yolk IgY: protection against rotavirus induced diarrhea and modulatory effect on the systemic and mucosal antibody responses in newborn calves. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2011;142:156–169. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach MG, Webby RJ, Islam F, Walkden-Brown S, Emmoth E, Feinstein R, Gronvik KO. Cross-protection of chicken immunoglobulin Y antibodies against H5N1 and H1N1 viruses passively administered in mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1083–1090. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05075-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Zhao S, He D, Yang Y, Li Y, Zhu S. Preparation and characterization of egg yolk immunoglobulin Y specific to influenza B virus. Antiviral Res. 2012;93:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson MA, Steele D, Vojdani J, Wecker J, Parashar U. Global rotavirus surveillance: determining the need and measuring the impact of rotavirus vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(Suppl 1):S1–S8. doi: 10.1086/605061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M, Tan M, Wei C, Zhong W, Wang L, McNeal M, Jiang X. A candidate dual vaccine against influenza and noroviruses. Vaccine. 2011;29:7670–7677. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XF, Dai YC, Zhong W, Tan M, Lv ZP, Zhou YC, Jiang X. Tannic acid inhibited norovirus binding to HBGA receptors, a study of 50 Chinese medicinal herbs. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:1616–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]