Abstract

Purpose

Both the PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK signal transduction pathways mediate 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, releasing 4E-BP1 from the mRNA cap and permitting translation initiation. Given the prevalence of PTEN and B-RAF mutations in melanoma, we first examined translation initiation, as measured by phosphorylated 4E-BP1, in metastatic melanoma tissues and cell lines. We then tested the association between amounts of total and phosphorylated 4E-BP1 and patient survival.

Experimental Design

Seven human metastatic melanoma cells lines and 72 metastatic melanoma patients with accessible metastatic tumor tissues and extended follow up information were studied. Expression of 4E-BP1 transcript, total 4E-BP1 protein, and phosphorylated 4E-BP1 were examined. The relationship between 4E-BP1 transcript and protein expression was assessed in a subset of patient tumors (n=41). The association between total and phospho-4E-BP1 levels and survival was examined in the larger cohort of patients (n=72).

Results

4E-BP1 was hyperphosphorylated in 4/7 melanoma cell lines harboring BRAF and PTEN mutations as compared to untransformed melanocytes or RAS/RAF/PTEN wild type melanoma cells. 4E-BP1 transcript correlated with 4E-BP1 total protein levels as measured by the semi-quantitative reverse phase protein array (p=0.012). High levels of phosphorylated 4E-BP1 were associated with worse overall and post-recurrence survival (p=0.02, 0.0003 respectively).

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that translation initiation is a common event in human metastatic melanoma and correlates with worse prognosis. Therefore, effective inhibition of the pathways responsible for 4E-BP1 phosphorylation should be considered to improve the treatment outcome of metastatic melanoma patients.

Keywords: 4E-BP1, translation, metastatic melanoma

Introduction

Over the last few years, our understanding of the molecular alterations underlying melanoma development and progression has rapidly advanced, with several independent signaling pathways having been implicated in melanoma pathogenesis, including the RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways (1–3). These recent discoveries have translated into the development of new molecularly-targeted therapies, such as specific B-RAF, MEK, and mTOR inhibitors. However, these therapeutic agents have shown only modest activity against melanoma in phase II clinical testing (4,5). Alternative strategies based on a better understanding of the complex molecular pathogenesis of melanoma are needed before improvement in treatment outcomes for metastatic melanoma patients can be appreciated.

The PI3K/AKT pathway canonically regulates translation via activation of mTOR kinase and subsequent phosphorylation of its substrates, 4E-BP1 and S6K, which leads to formation of the eIF4F translation initiation complex (6–8). Sustained activation of this translation machinery is essential for the transformation of human cells in culture and the maintenance of the malignant phenotype (9,10). In this regard, 4E-BP1 phosphorylation has recently been shown to correlate with worse pathologic grade and prognosis in human breast cancer (11). The RAS/MAPK pathway also contributes to the formation of eIF4F and activation of translation through ERK-mediated phosphorylation of both S6K and 4E-BP1 and MNK-mediated phosphorylation of eIF4E. Thus, both RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling mediate phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, thereby disengaging the protein from the mRNA cap and disinhibiting translation (12,13).

In this study, we assessed eIF4F complex formation by measuring total and phosphorylated 4E-BP1 in both cell lines and in metastatic melanoma tumors. We first assessed the levels of 4E-BP1 phosphorylated at different sites (T37/46, T70, S65), as well as total and phosphorylated levels of the translation initiation factors eIF4G and eIF4E in a panel of 7 human melanoma cell lines. We found that levels of phosphorylated 4E-BP1 varied widely among the 7 melanoma cell lines and were higher in the BRAF and PTEN mutated cells. As p-4E-BP1 was differentially regulated among melanoma cell lines, we then employed a combination of assays to study the expression of total and phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (p-4E-BP1) in the tumors of metastatic melanoma patients and studied the association of both protein expression and phosphorylation with survival.

Our data demonstrate that translation initiation, as measured by p-4E-BP1, is a common event in human metastatic melanoma and correlates with worse prognosis. Given the convergence of RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling that mediates phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, dephosphorylation of 4E-BP1 may prove to be an effective strategy to improve treatment outcome in patients with metastatic melanoma.

Materials and Methods

Tissue culture and Western blot analysis

Seven human metastatic melanoma cell lines, including SkMel-31, SkMel-2, SkMel-11, SkMel-37, SkMel-39, SkMel-28, and SkMel-5 (kindly provided by Dr. Alan Houghton at MSKCC), as well as the PI3K mutant human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were studied. Cells were maintained in either RPMI or a 1:1 mixture of DMEM:F-12 medium supplemented with 2mM glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 U/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum, incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. HeMnLP cells were maintained in Medium 254 (Gibco, Portland, OR) supplemented with Human Melanocyte Growth Supplement-2 (Gibco, Portland, OR). Cells were harvested and lysed in mRIPA buffer. Protein concentration was determined with the BCA method (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk and probed with 4E-BP1, p-4E-BP1 (T37/46), p-4E-BP1 (T70), p-4E-BP1 (S65), eIF4G, p-eIF4G (S1108), eIF4e, p-eIF4e (S209), PTEN (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) as well as β-actin antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Proteins were detected using the ECL kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and densitometry was performed with MultiGuage Software (FujiFilm Life Sciences, Stamford, CT).

Patient Characteristics

The study cohort consisted of 72 metastatic melanoma patients identified through the Interdisciplinary Melanoma Cooperative Group database at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine (male= 48, female=24, median age 60.0). Of the 77 specimens from 72 patients, 34 were lymph node metastases, 28 were skin metastases, and 15 were visceral metastases. Seventy-seven specimens from 72 patients were used for immunohistochemistry (IHC), and 41 specimens from 36 patients were used for transcript expression analysis and RPPA. Of the 77 specimens, 39 were analyzed by IHC, microarray analysis, and reverse phase protein array (RPPA) for total and p-4E-BP1 based on corresponding paraffin tissue availability. Serum LDH was measured in 47 of the 72 patients. BRAF mutation status was determined by DNA sequencing in tissue specimens from 29 of the 72 patients. The median follow-up time for the cohort from the time of primary diagnosis to last follow-up date was 44.32 months. The study was approved by the NYU Institutional Review Board, and all patients signed informed consent before enrollment. Relevant clinicopathologic, demographic, and survival data were recorded for all patients.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed on 77 formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissues using rabbit anti-human T70-p4E-BP1 and total-4E-BP1 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). In brief, sections were deparaffinized in xylene (3 changes), rehydrated through graded alcohols (3 changes 100% ethanol, 3 changes 95% ethanol), and rinsed in distilled water. Heat induced epitope retrieval was performed in 10mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 minutes (both antibodies) in a 1200-Watt microwave oven at 90% power. Sections were allowed to cool for 30 minutes and then rinsed in distilled water. Antibody incubations and detection were carried out at 37°C on a NEXes instrument (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, Arizona) using Ventana’s reagent buffer and detection kits, unless otherwise noted. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with hydrogen peroxide. Antibodies against T70-p4E-BP1 and total-4E-BP1 were diluted 1:50 and 1:40, respectively, in PBS and incubated overnight at room temperature. Primary antibodies were detected with Ventana’s biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary followed by streptavidin-horseradish-peroxidase conjugate. The complex was visualized with Naphthol-AS-MX phosphatase and Fast Red complex. Slides were washed in distilled water, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted with permanent media. Appropriate positive and negative controls were included with the study sections. The levels of 4E-BP1 and p-4E-BP1 expression were based on the proportion of melanoma cells with positive cytoplasmic and/or nuclear staining and were scored on a continuous scale from 0% (undetectable) to 100% (homogeneous staining) by an attending pathologist (H.Y.) who was blinded to the clinical data. Several fields were scanned before an estimate of the percent tumor cells expressing either 4E-BP1 or p-4E-BP1 was recorded as a continuous variable from 0 to 100%. The intensity of the signal (0, 1+, 2+, or 3+) was also recorded.

Reverse Phase Protein Array

For detailed protocol, see reference 14. One to two 5 micron thick fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were harvested from glass slides and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube in 40–50ul of 1%SDS lysis buffer. The lysate was then sonicated in a water bath for 20 minutes, boiled at 100°C for 20 minutes, and incubated in a heat block at 60°C for 20 minutes. The lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 RPM for 10 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and protein quantitation was carried out with the BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). B-mercaptoethanol was then added to samples to 2.5% by volume. The samples were boiled again before printing of the lysate on nitrocellulose-coated glass slides with an automated robotic arrayer. Before exposure to primary antibody, array slides were blocked for endogenous peroxidase, avidin, and biotin protein activity. Primary antibody signal was amplified by the 3,3;-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride DAKO signal amplification system (Copenhagen, Denmark). Signal intensity was measured by scanning the slides with ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and quantified using the MicroVigene automated RPPA module (VigeneTech, Inc., North Billerica, MA). Using MicroVigene software, the intensity of each spot was calculated and an intensity concentration curve was calculated with a slope and intercept. For comparison to mRNA results, differences in loading were assessed and corrected for by normalizing the expression intensities of 4E-BP1 and p-4E-BP1 to ERK2.

Affymetrix Gene Expression

Data mining of Affymetrix U133Plus2.0 GeneChip array results for 4E-BP1 transcript levels was performed for all available fresh tumor tissue specimens, which included 42 metastatic melanoma specimens from 37 patients (included were 3 patients who had two metastases and 1 patient who had three metastases). Tissue collection, whole RNA extraction, preparation of cRNA, and raw data analysis were performed as previously described (15).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics. Cox proportional hazard model was used to examine the association between total 4E-BP1 and p-4E-BP1 transcript levels and protein expression with overall survival (time from initial diagnosis of melanoma to death) and post-recurrence survival (time from first recurrence to death). 4E-BP1 and p-4E-BP1 levels were analyzed as continuous variables and as positive/negative expression, using 40% as a cut-off point as values occurred in a bimodal distribution with no values occurring between 40 and 80%. As the intensity of staining was uniformly strong (2–3+), the intensity of staining was not incorporated into the analysis. Serum LDH was analyzed as a dichotomous variable. High LDH was defined as greater than the upper limit of normal at NYU Medical Center (>618 U/L). Multivariate survival analysis of LDH, site of metastasis, and p-4E-BP1 as a continuous variable was performed using the multivariable Cox proportional hazard model in a subset of patients (n=47). Multivariate analysis of LDH, site of metastasis, and p-4E-BP1 as a dichotomous variable was performed with the stratified log-rank test. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to examine the relationship between transcript levels and protein expression. To examine the agreement between positive/negative expression of the markers, Kappa statistic and its approximate standard error were calculated. All p-values were two-sided with statistical significance at the 0.05 alpha level. All analyses were performed in statistical programming and software package R.1

Results

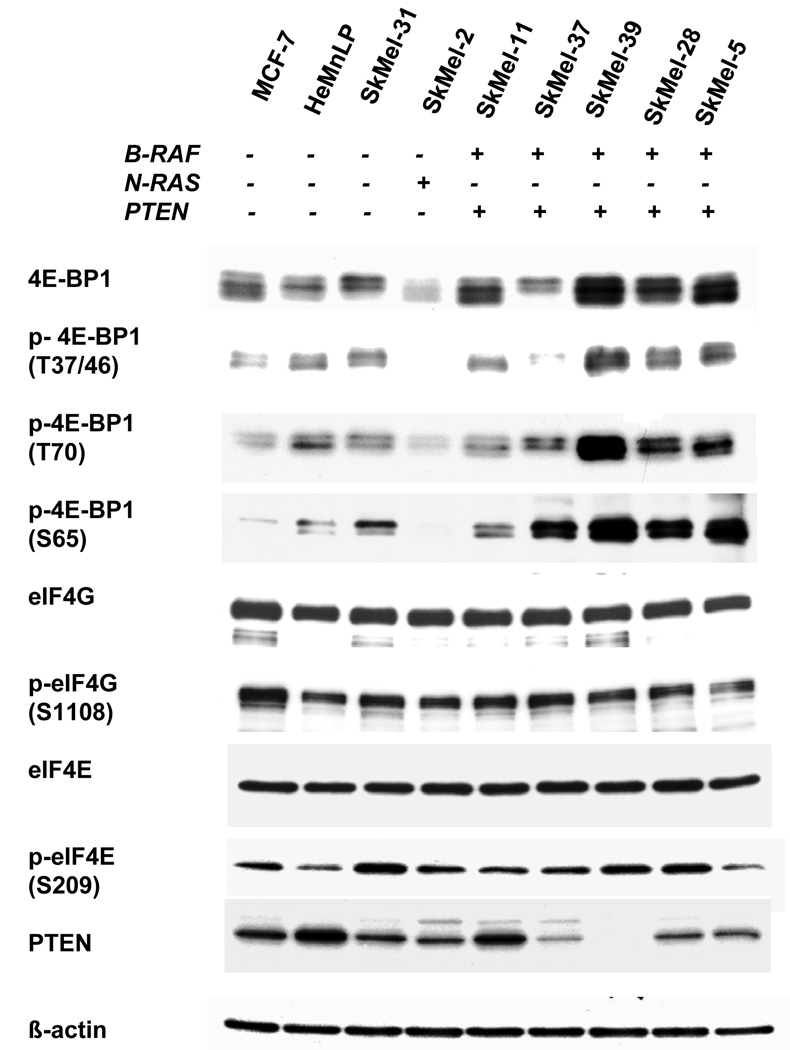

4E-BP1 is hyperphosphorylated in melanoma cell lines

Expression levels of the translation repressor protein 4E-BP1 were measured by Western blot in a panel of 9 cell lines including the PI3K mutant breast cancer cell line MCF-7, the melanocyte cell line HeMnLP, and seven melanoma cell lines characterized for N-RAS, BRAF, and PTEN mutation status. 4E-BP1 was detected in each of the 9 cell lines (Figure 1). 4E-BP1 was strongly expressed in 4 of the 7 melanoma cell lines (SkMel-39, 28, 5, 11) and was also hyperphosphorylated in 4 of the 7 melanoma cell lines (SkMel-39, 28, 5, 37). B-Raf/PTEN mutants SkMel-11, SkMel-39, SkMel-28, and SkMel-5, were found to have 2–3 fold higher expression of 4E-BP1 compared to melanocytes or the wild type N-RAS/B-Raf SkMel-31. 4E-BP1 in SkMel-39, 28, and 5 was also strongly hyperphosphorylated at sites crucial for disengagement from the mRNA cap (T37/46, T70, and S65). These lines expressed 4- to 7-fold higher p-4E-BP1 T37/46 levels, 4- to 5-fold higher p-4E-BP1 (T70) levels, and 6- to 8-fold higher p-4E-BP1 S65 levels than melanocytes or SkMel-31. Although SkMel-37 did not overexpress 4E-BP1 as compared to melanocytes, these cells expressed 6-fold higher p-4E-BP1 (S65) levels compared to HeMnLP. Expression and phosphorylation of the translation initiation factors eIF4G and eIF4E were also measured. There was minimal variability in either total or phosphorylated eIF4G or eIF4E among all 9 cell lines. PTEN expression was also measured in the panel. The PTEN mutant lines SkMel-37, SkMel-39, SkMel-28, and SkMel-5 expressed less PTEN than melanocytes or SkMel-31.

Figure 1. 4E-BP1 is expressed and phosphorylated in melanoma cell lines.

A The breast cancer cell line MCF-7, melanocytes, and seven melanoma cell lines were grown in 10 cm dishes in their respective maintenance media for 24 hours before harvesting. Expression levels of total and phosphorylated forms of 4E-BP1, eIF4G, and eIF4e were measured by western blot. PTEN expression was also measured by western blot. B- actin was used as a loading control.

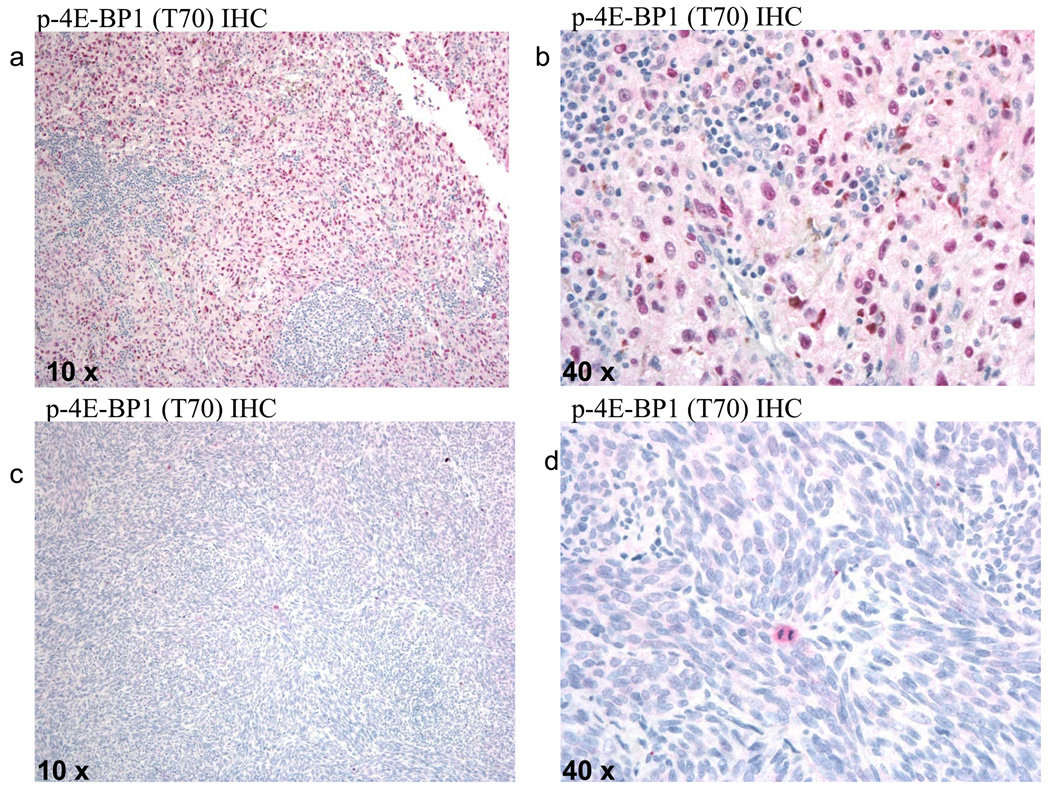

p-4E-BP1 (T70) is associated with poor survival in human metastatic melanoma

Total and p-4E-BP1 (T70) expression were assessed in 77 specimens from 72 metastatic melanoma patients using IHC. Ninety-seven percent of the specimens stained positively (>0%) for 4E-BP1 and 74% stained positively (>0%) for p-4E-BP1 (T70) (Figure 2a,b). IHC staining for 4E-BP1 yielded values ranging from 0%–100%, with a mean of 95%. IHC staining for p-4E-BP1 (T70) yielded a range of values from 0%–100% with a mean of 53%. Total and p-4E-BP1 staining was found in the nucleus and cytoplasm of melanoma cells, while tumor lymphocytes did not stain positively for either 4E-BP1 or p-4E-BP1. p-4E-BP1 was particularly enriched in the nucleus, while 4E-BP1 staining was more evenly distributed between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Cells displaying mitotic figures strongly expressed p-4E-BP1 (T70) (Figure 2c,d).

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical detection of p-4E-BP1 in metastatic melanoma patients.

Metastatic melanoma specimen showing diffuse cytoplasmic and nuclear p-4E-BP1 staining of melanoma cells with sparing of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes at A, 10x and B, 40x magnification. Metastatic melanoma specimen staining negative for p-4E-BP1, with expression of p-4E-BP1 in an actively dividing cell (red staining with Naphthol-AS-MX phosphatase and Fast Red complex) at C, 10x and D, 40x magnification.

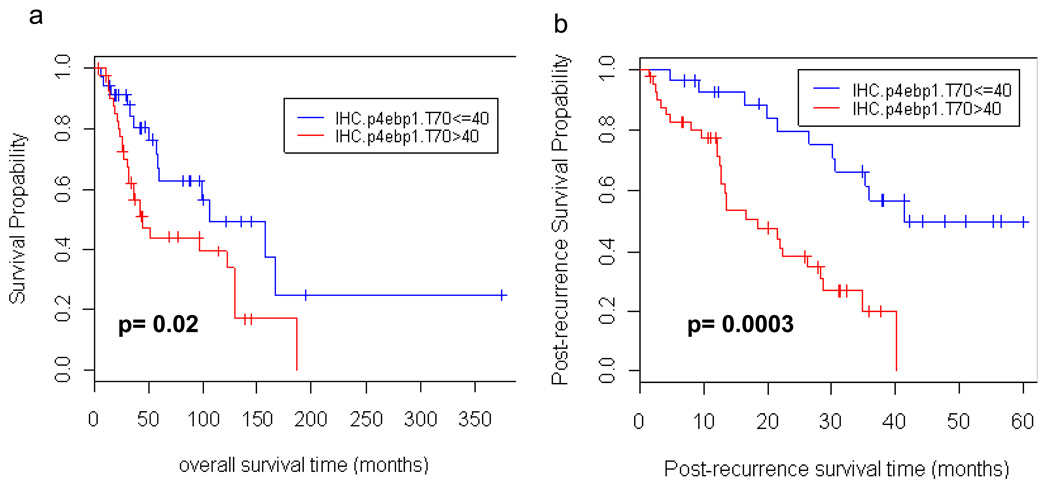

A statistically significant association between p-4E-BP1 (T70) expression and worse overall and post-recurrence survival was detected (HR=1.01, 1.01, p=0.033, 0.002, respectively) which suggests that every 1% increase in p-4E-BP1 staining increases the hazard by 1%. A review of the IHC demonstrated a dichotomous distribution of p-4EBP1 staining, as 35 samples had ≤ 40% positivity, and 42 samples had ≥ 80% positivity. Patients with > 40% p-4E-BP1 staining had worse overall five year survival than those with less than or equal to 40% p-4E-BP1 staining (HR=2.12, p-value=0.02 using log-rank test). Patients with higher p-4E-BP1 staining had a 5 year survival of 44.3% (95% CI= (30.6%, 64.2%)) as compared to 62.8% (95%CI = (46.5%, 84.9%)) for those with less than or equal to 40% staining (Figure 3a). In addition to poor overall survival in the high p-4E-BP1 cohort as compared to the low p-4E-BP1 cohort, there was a significant difference in post-recurrence survival between these two groups (HR=3.75, p-value=0.0003 using log-rank test) (Figure 3b). Two year post-recurrence survival probabilities were 79.5% (95%CI = (64.9%, 97.4%)) for subjects with low IHC p-4E-BP1 T70 values and 38.0% (95% CI= (24.7%, 58.5%)) for subjects with high IHC p-4E-BP1 T70 values.

Figure 3. High p-4E-BP1 levels are associated with poor overall and post-recurrence survival.

A. Kaplan-Meier curves for patients with low/high IHC.p4ebp1.T70 values (based on data for 77 specimens without missing values). 5yr overall survival probabilities for the two groups are: 62.8% (95%CI = (46.5%, 84.9%)) and 44.3% (95% CI= (30.6%, 64.0%)), respectively. The difference in the two groups is significant at the 0.05 significance level (HR=2.12, p=0.02 using log-rank test). B. Kaplan-Meier post-recurrence curves for patients with low/high IHC.p4ebp1.T70 values (based on data for 77 specimens without missing values). There was a significant difference in post-recurrence survival between these two groups (HR=3.75, p-value=0.0003 using log-rank test). Two year post-recurrence survival probabilities are: 79.5% (95%CI = (64.9%, 97.4%)) for subjects with low IHC.p4ebp1.T70 values and 38.0% (95% CI= (24.7%, 58.5%)) for subjects with high IHC.p4ebp1.T70 values.

As metastatic melanoma patients with visceral metastases have a worse prognosis compared to those with only lymph node or skin metastates, the distribution of metastatic sites in the high and low IHC p-4EBP1 categories was examined. The proportion of visceral metastases was slightly higher among those with low IHC p-4EBP1 compared to those with high IHC p-4E-BP1 (25.7% (9/35) vs. 14.3% (6/42), respectively), but the difference was not significant statistically (p-value=0.25 using Fisher's exact test). The time from primary diagnosis to resection of metastasis was also assessed in the high and low IHC p-4E-BP1 cohorts. The median time to metastasis (in months) for the low and high groups was 38.4 months (95% CI= (15.3, 75.1) and 18.1 months (95%CI=(12.9, 36.5)), respectively. The difference was not, however, statistically significant (p-value=0.24 using log-rank test).

As four patients had multiple specimens (3 subjects had 2 specimens each and 1 subject had 3 specimens), frailty models with several commonly used frailty distributions (gamma, Gaussian and t distribution of various degrees of freedom) were further employed to examine the impact of accounting for clustering on the association between overall and post recurrence survivals and IHC p-4E-BP1. For overall survival, the p-values remained significant and ranged from 0.023–0.038 using frailty models. For post-recurrence survival, the p-values remained significant and ranged from 0.002–0.004.

p-4E-BP1 (T70) is associated with worse survival in melanoma patients independent of known prognostic factors

LDH serum values were measured at the time of first metastasis in a subset of our patient cohort (n=47). In this subset, we found that high LDH was associated with worse survival. The association between high LDH and overall survival was not statistically significant (HR=1.55, p=0.24). However, significantly greater hazard of post-recurrence survival was observed for patients with high LDH levels (HR=2.26, p=0.03, log-rank test). Multivariate survival analysis in a subset of patients (n=47) demonstrated that p-4E-BP1 (T70) was associated with worse survival in melanoma patients independent of established prognostic indicators, specifically site of metastasis and serum LDH. The association between IHC p-4e-bp1 and overall and post-recurrence survival remained significant (HR =1.01 and 1.03, p=0.03 and <0.001, respectively) after adjusting for LDH level and site of metastasis using multivariable Cox proportional hazard model. When p-4E-BP1 (T70) was treated as a dichotomous variable, after adjusting for LDH level and site of metastasis using stratified log-rank test, patients with higher p-4E-BP1 staining had significantly worse overall and post recurrence survival compared to those with low p-4E-BP1 (HR=2.29, and 5.26, p=0.04 and <0.001, respectively). There was no statistically significant association between level of p-4E-BP1 and site of metastasis or between p-4E-BP1 and LDH levels.

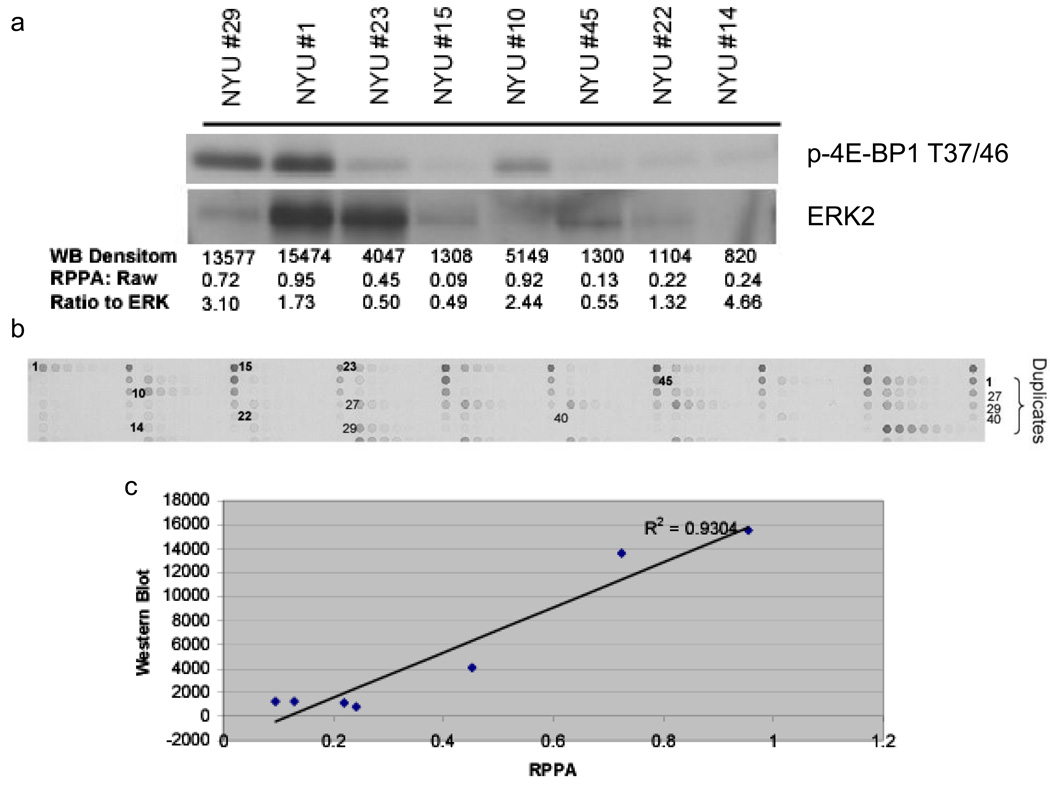

4E-BP1 and p-4E-BP1 (T37/46, T70) can be detected in paraffin embedded tumor specimens with reverse phase protein array

In an effort to quantify levels of total and phospho-4E-BP1 in paraffin-embedded tissue samples and to correlate total protein amounts with transcript levels, we employed the semi-quantitative reverse phase protein array technology (RPPA). Tumor lysates were derived from 41 formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded metastatic melanoma sections. One to two sections were harvested per specimen. These lysates were printed onto nitrocellulose-coated glass slides and RPPA was conducted with antibodies to 4E-BP1 and p-4E-BP1 (T37/46). To determine whether signals detected with RPPA correlate with levels detected by western blotting, a subset of the samples with sufficient protein available for both techniques were analyzed (Figure 4a,b). Western blotting analysis of total 4E-BP1 demonstrated minimal protein degradation, indicating that the technique for protein isolation from the paraffin-embedded samples maintained the integrity of the protein (Supplementary Figure 1). A comparison of the densitometry results of Western blotting with RPPA results demonstrated a high degree of correlation for both the total (r2= 0.81) and p-4EBP1 (r2 = 0.93) levels for these samples (Figure 4c). In addition to both 4E-BP1 and p-4E-BP1 (T37/46), p-4E-BP1 (T70), AKT and ERK2 were also detected in these samples. Thus, 5 protein targets were detected in 41 human tumors using <1ug of tumor protein per sample.

Figure 4. RPPA detection of p-4E-BP1 in paraffin-embedded metastatic melanoma sections.

A. Lysates derived from 5 micron thick paraffin embedded metastatic melanoma sections were subjected to immunoblotting for p-4E-BP1 (T37/46) and signals were quantitated by densitometry. For comparison with microarray data, all total and p-4E-BP1 RPPA data was normalized to total ERK protein for each sample. B, Serial dilutions of lysates from 49 paraffin-embedded metastatic melanoma specimens were arrayed onto glass slides and incubated with primary p-4E-BP1 antibody. The brown signal amplification was achieved by horseradish peroxidase-mediated cleavage of 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride. C. p-4E-BP1 RPPA signal correlates strongly with p-4E-BP1 western signal (R2=0.93).

4E-BP1 transcript correlates with 4E-BP1 RPPA expression

Given the prevalence of total 4E-BP1 in melanoma cell lines, we profiled 42 metastatic melanoma specimens from 37 patients for 4E-BP1 mRNA using Affymetrix GeneChip microarray. Normalized 4E-BP1 microarray values ranged from 8.47 to 11.87, with a mean of 10.36. To determine whether higher transcript levels associated with increased total 4E-BP1 protein expression, we employed Spearman's method to examine the correlation between the semi-quantitative RPPA results and microarray values. There was a positive correlation between 4E-BP1 transcript levels and 4E-BP1 RPPA expression (rs=0.39, p=0.012). A weak correlation between 4E-BP1 transcript levels and 4E-BP1 IHC expression was also found (rs=0.27), but this association was not statistically significant (p=0.12).

Discussion

Our study reveals several important findings. We found that 4E-BP1 is strongly expressed and hyperphosphorylated in melanoma cell lines with BRAF and PTEN mutations, illustrating the convergence of hyperactivated MAPK and PI3K signaling on 4E-BP1. We also showed that accumulation of total 4E-BP1 is associated with increased transcript expression. Moreover, we demonstrated that phosphorylated 4E-BP1 in melanoma metastases is associated with poor survival. The association between p-4E-BP1 and overall survival is largely due to the increased post-recurrence hazard associated with higher levels of p-4E-BP1.

The association between p-4E-BP1 in melanoma and worse survival is in concordance with data in breast (11) and ovarian (16) cancer that showed a significant correlation between p-4E-BP1 and both poor prognosis and high pathologic grade. Our observation of 4E-BP1 localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm corroborates previous reports of nuclear and cytoplasmic expression in breast cancer cells and mouse embryo fibroblasts (11, 17). The specificity of nuclear immunostaining was demonstrated using a blocking experiment with 4E-BP1 antibody preadsorbed with purified recombinant 4E-BP1 protein. Both nuclear and cytoplasmic reactivity were abolished in the melanoma cells, thereby confirming the specificity of the 4E-BP1 antibody (data not shown).

In this study, we also employed a novel high throughput protein array technology, which allowed detection of protein targets in as little as 10ng of tumor protein extracted from paraffin-embedded melanoma sections. This proved to be a useful approach for quantitative analysis of hyperactivated signaling networks in melanoma. 4E-BP1 transcript levels were found to correlate with 4E-BP1 expression as measured by RPPA, suggesting 4E-BP1 accumulation occurs secondary to an increase in message expression. The fact that the weak correlation of 4E-BP1 transcript with IHC protein expression did not reach statistical significance may be explained by the heterogeneity of different sections of tumor used to harvest mRNA and protein.

Our study reveals that p-4E-BP1 is significantly associated with worse survival, independent of LDH and metastatic site. A limitation of this multivariate analysis is that the majority of metastases were derived from surgical resection of accessible tissues such as skin and lymph node. This predominance of readily accessible metastases in our cohort may therefore limit the validity of independent association with outcome.

Future studies are needed to determine whether PTEN and B-RAF mutations are enriched in the tumors of patients that harbor high p-4E-BP1. Preliminary analyses of tissue from 29 patients from our cohort did not reveal a statistically significant association between p-4E-BP1 levels and B-RAF mutation (DNS). However, sequencing for B-RAF and PTEN mutations in a larger number of metastatic melanoma specimens is currently under way.

Although p-4E-BP1 was associated with poor overall and post-recurrence survival, a statistically significant association between total 4E-BP1 protein expression and overall or post-recurrence survival was not observed. The lack of correlation with poor survival might be a reflection of the translation suppressor function of 4E-BP1. Given that un-phosphorylated 4E-BP1 binds to the mRNA cap and prevents translation of oncogenic proteins, one would expect that some survival advantage is imparted to patients whose tumor cells robustly express 4E-BP1. In fact, inducing 4E-BP1 expression so as to overwhelm the ability of upstream signaling pathways to phosphorylate and inactivate 4E-BP1 might prove an effective anticancer strategy.

Given the prevalence of p-4E-BP1 in the most aggressive subset of metastatic melanomas, strategies to upregulate and/or dephosphorylate 4E-BP1 may be powerful therapeutic options in this disease. Combined suppression of the upstream signaling pathways that activate 4E-BP1, namely PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK, may also effectively restrain deregulated translation. Recently, combined mTOR and MEK inhibition has been reported to effectively inhibit 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, polysome formation, and cell growth in non-small cell lung cancer (18). Targeting both mTOR and MEK may therefore be a useful strategy to dephosphorylate 4E-BP1 and inhibit translation. Alternatively, directly modifying the translation machinery may be effective. Small molecules, such as phenethyl isothiocyanate, which induce 4E-BP1 expression and prevent 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, are in development (19). Also, small molecule inhibitors of the elongation initiation factor 4E (eIF4e) and inhibitors of the eIF4e-eIF4G interaction are being developed to prevent eIF4F complex assembly and inhibit translation in cancer cells (20).

In sum, the eIF4F complex receives signaling input from many mitogenic signal transduction pathways. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 is emerging as a common theme in the cancer cell’s strategy to evade physiologic restraints on protein biosynthesis. Further study of the signaling pathways that regulate 4E-BP1 expression and phosphorylation in melanoma may reveal additional therapeutic strategies to attenuate unrestrained protein biosynthesis in this malignancy.

Supplementary Material

Two to three 5 micron thick paraffin-embedded human metastatic melanoma sections from five different tissue blocks were sonicated/boiled in RPPA lysis buffer/4x SDS buffer (3:1). The respective lysates were boiled and run on SDS-PAGE and probed for total 4E-BP1.

Acknowledgments

Financial support K.E.O was supported by the American Skin Association and the NIH MSTP grant GM07739. I.O. supported by NYU Cancer Center Core Grant (5 P30 CA 016087-27) and Chemotherapy Foundation Grant. M. A. D. was supported by grant P50 CA093459 from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center SPORE in Melanoma, and The ASCO Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award.

Footnotes

R Development Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2007.

References

- 1.Miller AJ, Mihm MC., Jr Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:51–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haluska FG, Tsao H, Wu H, Haluska FS, Lazar A, Goel V. Genetic alterations in signaling pathways in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2301s–2307s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel VK, Lazar AJ, Warneke CL, Redston MS, Haluska FG. Examination of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and PTEN in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:154–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haass NK, Sproesser K, Nguyen TK, et al. The mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) induces growth arrest in melanoma cells and tumor regression when combined with docetaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:230–239. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escudier B, Lassau N, Angevin E, et al. Phase I trial of sorafenib in combination with IFN alpha-2a in patients with unresectable and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma or malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1801–1809. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–6422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avdulov S, Li S, Michalek V, et al. Activation of translation complex eIF4F is essential for the genesis and maintenance of the malignant phenotype in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wendel HG, De Stanchina E, Fridman JS, et al. Survival signalling by Akt and eIF4E in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nature. 2004;428:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature02369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rojo F, Najera L, Lirola J, et al. 4E-binding protein 1, a cell signaling hallmark in breast cancer that correlates with pathologic grade and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:81–89. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland EC, Sonenberg N, Pandolfi PP, Thomas G. Signaling control of mRNA translation in cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:3138–3144. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roux PP, Shahbazian D, Vu H, et al. RAS/ERK signaling promotes site-specific ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation via RSK and stimulates cap-dependent translation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14056–14064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tibes R, Qiu Y, Lu Y, et al. Reverse phase protein array: validation of a novel proteomic technology and utility for analysis of primary leukemia specimens and hematopoietic stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2512–2521. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velazquez EF, Yancovitz M, Pavlick A, et al. Clinical relevance of neutral endopeptidase (NEP/CD10) in melanoma. J Transl Med. 2007;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castellvi J, Garcia A, Rojo F, et al. Phosphorylated 4E binding protein 1: a hallmark of cell signaling that correlates with survival in ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:1801–1811. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rong L, Livingstone M, Sukarieh R, et al. Control of eIF4E cellular localization by eIF4E-binding proteins, 4E-BPs. RNA. 2008;14:1318–1327. doi: 10.1261/rna.950608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legrier ME, Yang CP, Yan HG, et al. Targeting protein translation in human non small cell lung cancer via combined MEK and mammalian target of rapamycin suppression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11300–11308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Straub J, Xiao D, et al. Phenethyl isothiocyanate, a cancer chemopreventive constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits cap-dependent translation by regulating the level and phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3569–3573. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graff JR, Konicek BW, Carter JH, Marcusson EG. Targeting the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:631–634. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Two to three 5 micron thick paraffin-embedded human metastatic melanoma sections from five different tissue blocks were sonicated/boiled in RPPA lysis buffer/4x SDS buffer (3:1). The respective lysates were boiled and run on SDS-PAGE and probed for total 4E-BP1.