Abstract

Dolichols, polyisoprene alcohols derived from the mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis, serve as carriers of glycan precursors for the formation of oligosaccharides important in protein glycosylation. Seven autosomal-recessively inherited disorders in the metabolism (synthesis, utilization, recycling) of the dolichols have recently been described, and all are associated with decreased lipid-linked oligosaccharides leading to underglycosylated proteins or lipids which facilitate their detection in the diagnostic laboratory. Multisystem pathology encompasses developmental delays and eye, heart, skin and muscle abnormalities; outcomes range from death in infancy to mild, late-onset disease.

Keywords: ichthyosis, retinitis pigmentosa, muscular dystrophy, dolichol, glycosylation, mannosylation, isoprene, isoprenoids, cholesterol

INTRODUCTION

With pleiotropic roles in cell structure, embryo development, and signaling it is not surprising that the inherited disorders of cholesterol biosynthesis feature a prominent component of malformation [Porter and Herman, 2011; Schaaf et al., 2011; Shackleton, 2012]. The majority of these disorders reside in the distal portion of the pathway (e.g., beyond farnesyl diphosphate; Fig. 1), and include Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, desmosterolosis, lathosterolosis, hydrops–ectopic calcification–motheaten skeletal dysplasia, X-linked dominant chondro-dysplasia punctata, congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects syndrome and sterol-C4-methyloxidase deficiency [He et al., 2011; Porter and Herman, 2011]. The sole disorder of sterol metabolism in the proximal pathway is represented by mevalonate kinase deficiency, a rare disorder manifesting as two distinct syndromes: mevalonic aciduria and hyper-IgD syndrome (HIDS) [Marcuzzi et al., 2012]. Mutations in the human MVK gene underlie both diseases, and the neuropathology associated with mevalonic aciduria is generally absent in patients with HIDS who manifest cyclic fever.

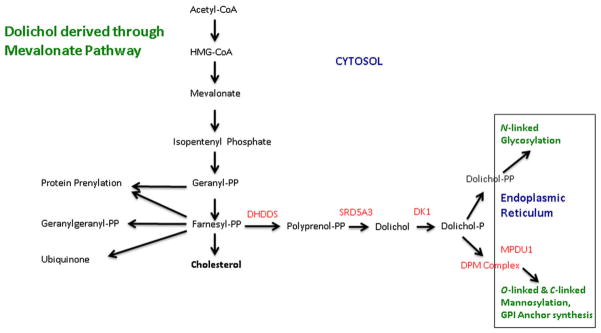

Figure 1.

Interrelationships between cholesterol biosynthesis and molecular glycosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum that is bridged via the dolichols. The sites of the defects reported in this review are shown in red, including: dehydrodolichyl diphosphate synthase (DHDDS) deficiency; steroid 5-α-reductase (SRD5A3) deficiency; dolichol kinase (DK1) deficiency; dolichyl-phosphate mannosyl-transferase (DMP) complex deficiency (including defects in subunits DMP 1, 2, and 3); and mannose-P-dolichol utilization defect 1 (MPDU1) protein deficiency. Additional abbreviations: CoA, coenzyme A; PP, pyrophosphate, or diphosphate; GPI, glycophosphati-dylinositol. Not all steps in each pathway are shown.

The cholesterol pathway also generates a number of non-sterol isoprene compounds, the most prominent represented by ubiquinone and the dolichols (Fig. 1). Isoprene (2-methyl-1,3-butadiene), one of the most abundant molecular building blocks in nature, is represented in the proximal pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis in the form of isopentenyl phosphate (IPP; Fig. 1). Condensation of IPP with an additional activated isoprene, dimethylallyl diphosphate, yields geranyl diphosphate (Fig. 1), which is further metabolized to farnesyl diphosphate and eventually ubiquinone and the dolichols. The latter are structurally similar, yet diverse, long-chain unsaturated intermediates that culminate in a free alcohol moiety. This alcohol may undergo biological activation to produce both mono-and di-phosphate species, the latter conjugating with various carbohydrates (glucose, galactose, and mannose). Activated dolichol sugars serve as the carbohydrate donor to growing oligosaccharide chains of post-translation-ally modified proteins (glycoproteins) and lipids (glycolipids). These post-translational modifications encompass N-linked glycosylation (N = the nitrogen side-group of the amino acids asparagine or arginine), O-linked glycosylation (O = the oxygen in the alcohol side groups of serine, threonine or tyrosine) and C-linked glycosylation (C = a carbon in the side chain of tryptophan). Once the sugar is donated, the dolichol carrier is recycled for further intracellular reactions [Eklund and Freeze, 2006; Freeze, 2007].

In the last decade, seven autosomal-recessively inherited disorders in the metabolism of the dolichols have been described. All lead to hypoglycosylated target proteins, which allows for the identification of these disorders in the diagnostic laboratory. Based upon this finding, these disorders have been identified as congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) [Freeze, 2002; Freeze and Aebi, 2005; Denecke and Kranz, 2009]. In the current overview, we highlight the common clinical features of and the approach to the diagnosis of these disorders, which are unique in bridging the pathways of sterol biosynthesis with the processes of molecular glycosylation (Table I).

TABLE I.

Inherited Defects in the Synthesis and Recycling of the Dolichols

| Disorder | CDG nomenclature | Chromosome localization | Major organs involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHDDS deficiency | DHDDS-CDG | 1p36.11 | Eye, skin, bone |

| SRD5A3 deficiency | CDG-Iq | 4q12 | Brain, eye, heart, blood, GI, skin, bone |

| DK1 deficiency | CDG-Im | 9q34.11 | Brain, muscle, heart, blood, GI, skin, bone |

| DPM1 deficiency | CDG-Ie | 20q13.13 | Eye, brain, muscle, blood |

| DPM2 deficiency | DPM2-CDG | 9q34.13 | Brain, muscle, GI |

| DPM3 deficiency | CDG-Io | 1q22 | Brain, muscle, heart |

| MPDU1 deficiency | CDG-If | 17p13.1-p12 | Brain, muscle, eye, GI, skin, bone |

See text for disorder abbreviations. Additional abbreviations: CDG, congenital disorder of glycosylation; GI, gastrointestinal.

DISORDERS IN THE SYNTHESIS OF DOLICHOLS

Dehydrodolichyl Diphosphate Synthase (DHDDS) Deficiency

DHDDS catalyzes the initial step in the synthesis of the dolichols and promotes chain elongation to generate the poly-prenyl backbone. DHDDS is highly expressed in the photoreceptor layer of the eye, highlighting the cardinal phenotypic feature of ocular abnormalities associated with this disorder. For most patients, ocular symptoms reportedly commence in the second decade of life with compromised night-vision followed by progressive loss of peripheral vision with preservation of a central reading zone. DHDDS gene mutations associate with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) type 59, which has only been reported in the Ashkenazi Jewish population comprising 20 patients from 15 unrelated families [Zelinger et al., 2011]. Three affected siblings in a single family manifested loss of night and peripheral vision in their teens. Electroretinography, evaluating retinal cell responses in these three patients, showed a complete absence of cellular response with standard stimuli.

Homozygosity mapping identified a DHDDS gene variant on chromosome 1 (c.124A > G; Lys42Glu). The variant was not identified in 109 additional Ashkenazi Jewish patients with RP, 20 Ashkenazi Jewish patients with other retinal disorders, or 70 Caucasian patients (non-Ashkenazi Jewish) with retinal degeneration. The altered amino acid resides proximally to the farnesyl-diphosphate binding site of the DHDDS protein (Fig. 1), which is predicted to result in significant reduction of the dolichol phosphate pool required for glycosylation of rod photoreceptor proteins. The same mutation was also identified in an Ashkenazi Jewish family with an affected sibship employing whole exome sequencing [Züchner et al., 2011]. These authors documented the pathogenicity of this variant employing gene inactivation with morpholinos in the zebra fish homologue, replicating the ocular anomalies observed in patients.

Steroid 5-α-Reductase 3 (SRD5A3) Deficiency

SRD5A3 encodes a protein belonging to both the steroid 5-α reductase and the polyprenol reductase protein families that generate dolichols from polyprenols and is highly expressed in brain tissue, retina, and heart. SRD5A3 deficiency was originally described in 12 patients from nine families, predominantly consanguineous, presenting between 6 months and 12 years of age with comparable features. Ocular features in the predominantly female patients included nystagmus, colobomas (retinal, iris, or chorioretinal), optic nerve hypoplasia or atrophy, cataracts, glaucoma, and/or micro-ophthalmia (Fig. 2). Three patients had congenital heart defects including an atrial septal defect, transposition of the great vessels and a pulmonary valve defect. The differential diagnosis of coloboma, heart anomaly, choanal atresia, retardation, genital and ear anomalies syndrome was ruled out by molecular studies. Additional features in affected probands included severe intellectual disability, cerebellar vermis atrophy, ataxia, transient microcytic anemia, liver dysfunction with coagulopathy, feeding problems, ichthyosis, spasticity, movement disorders and stereotypic movements [Morava et al., 2010]. Subsequently, a single affected male from a non-consanguineous family was reported with the same disorder [Kasapkara et al., 2012]. Extended laboratory studies in these patients revealed an elevation of plasma polyprenols detected on mass spectrometry. Homozygosity mapping identified seven mutations, primarily missense, in the original 12 patients [Morava et al., 2010]. SRD5A3 deficiency was previously described as Kahrizi syndrome in a large cohort of German patients, all of whom manifested a homozygous mutation, but without confirmation of the underlying plasma polyprenol accumulation [Kahrizi et al., 2011]. Thus, Kahrizi syndrome and SRD5A3 deficiency are considered allelic disorders.

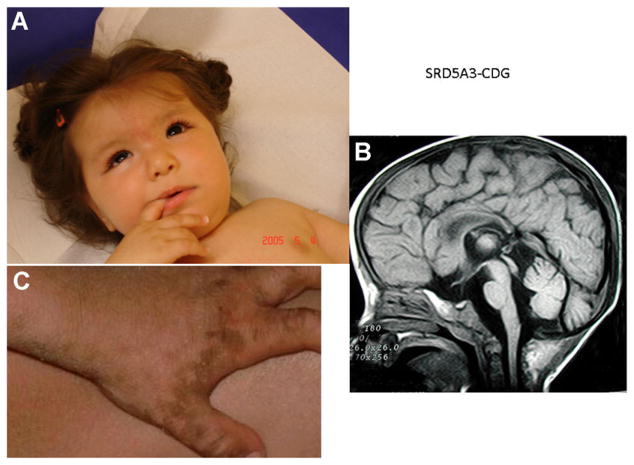

Figure 2.

(with permission from family). A: Facial features of SRD5A3-deficient patient at age 4 months. Note midfacial hypoplasia, strabismus, and epicanthal folds. Absence of fixation was associated with glaucoma (and severely decreased visual function). B: Sagittal MRI revealing generalized cerebral atrophy and vermis atrophy at the age of 2 years. C: Ichthyosis of the medial and lateral borders of the palm and fingers, associated with extremely dry, thick skin with minimal scaling.

Dolichol Kinase (DK1) Deficiency

DK1 encodes a protein involved in the formation of dolichol mannose, essential for C-linked mannosylation, N- and O-linked glycosylation, and the biosynthesis of glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors in subcellular organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [Chen et al., 1998]. The fatty acids within the phosphatidylinositol moiety function to anchor the protein undergoing post-translational modification to the cell membrane [Puoti and Conzelmann, 1992]. As expected, DK1 deficiency results in disruption of multiple glycosylation pathways and manifests severe pathology [Denecke and Kranz, 2009; Cantagrel and Lefeber, 2011].

DK1 deficiency was initially reported in four children from two consanguineous families [Kranz et al., 2007]. Clinical manifestations included microcephaly, “parchment-like” ichthyosis with loss of hair, eyebrows and eyelashes, intractable seizures, severe hypotonia with elevated Creatine Kinase (CK), severe liver dysfunction, and progressive dilated cardiomyopathy resulting in death within 1 year. Dolichol kinase activity measured in skin fibroblasts was 5% or less of parallel controls [Kranz et al., 2007]. Subsequently, Lefeber reported 11 patients (5–13 years of age) with progressive dilated cardiomyopathy, mild hypotonia with elevated CK levels and persistent elevations of transaminases, and mild coagulopathy [Lefeber et al., 2011]. Half of the probands had variable ichthyosis, and mild intellectual disability was noted in three. None showed overt seizure activity. Three novel DK1 missense mutations were identified, which resulted in an O-linked mannosylation abnormality of the heart-specific α-dystroglycan subunit.

Kapusta et al. [2012] recently provided a 5-year follow-up of nine surviving DK1-deficient patients. All pro-bands were reported to have a primary cardiac presentation without seizures, dysmorphic features, ichthyosis or intellectual disability. All had a dilated cardiomyopathy that led to life-threatening dysrhythmias, persistent transaminase elevations with decreased Factors XI and ATIII, and microcytic anemia, and the ensuing neutropenia and overwhelming infections resulted in two deaths. A homozygous missense mutation (His408Asp) in the DK1 gene was detected in two families, and a homozygous Trp304Cys mutation in a third family. Four children with mild dilated cardiomyopathy were treated with digoxin, diuretics, beta-blockers, and ACE-inhibitors. Three underwent heart transplant, one of whom died unexpectedly at 16 years of age, and two of whom were 1 and 5 years post-transplant. Skin abnormalities in this cohort were reported as sporadic, mild dry skin [Kapusta et al., 2012].

DISORDERS IN THE UTILIZATION AND RECYCLING OF DOLICHOLS

The dolichyl-phosphate mannosyltransferase (DPM; dolichyl-phosphate-D-mannose: protein O-D-mannosyltransferase) is a three-subunit (DPM 1–3) enzyme that donates D-mannose during glycosylation reactions on the luminal side of the ER (Fig. 1). Under regulation by DPM2, DPM1 lacks a carboxy-terminal transmembrane domain and a signal sequence. DPM2 is multifunctional and is also found in the GPI complex. Enzymatically active DPM1 is cytosolic and anchored to subunits 2 and 3 in the ER membrane via a C-terminal peptide of DPM3 [Kim et al., 2000; Maeda et al., 2000]. Because multiple glycosylation pathways are interrupted, it is predicted that an absence of any DPM subunit would lead to multisystem pathology.

DPM 1–3 Deficiencies

Four patients with DPM1 deficiency have been reported. The phenotype encompassed acquired microcephaly, dysmorphic facial features, visual loss with optic atrophy, frontal cortical atrophy and delayed myelination, intractable seizures, hypotonia with elevated CK, and low ATIII (antithrombin) [Imbach et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2000; Ashida et al., 2006].

Three patients from two Italian families were recently reported with DPM2 mutations. One of the families was consanguineous. The phenotype included acquired microcephaly, severe hypotonia associated with elevated CK, difficulty swallowing, and early-onset myoclonic epilepsy and cerebellar hypoplasia [Barone et al., 2012]. One female patient also manifested hepatomegaly with elevated transaminases and low ATIII. All probands had cortical visual impairment without structural eye abnormalities, and one male was diagnosed with optic atrophy. All succumbed to lethal infections by 3 years of age. A homozygous missense mutation c.68A>G; p.Tyr23Cys was found in one family, while the remaining family revealed compound heterozygosity for the same missense mutation and a splice site mutation [Barone et al., 2012]. A single adult patient with DPM3 deficiency developed acquired short stature, mild intellectual disability, and a phenotype suggestive of mild muscular dystrophy. Despite persistently elevated CK levels, muscle biopsy at age 11 years was non-diagnostic. At age 20 years, she developed a dilated cardiomyopathy, and 1 year later she experienced a stroke-like event with normal coagulation studies, normal radiologic and unremarkable ophthalmology evaluations. A repeat muscle biopsy performed at this time demonstrated an α-dystroglycan O-linked mannosylation defect. DPM activity measured in muscle was 30% of controls. Sequencing of the DPM subunit genes revealed a DPM3 mutation resulting in a Leu85Ser substitution in a highly conserved position of a hydrophobic domain. Molecular modeling indicated that this mutation would negatively impact DPM1 and DPM3 interactions, presumably destabilizing the DPM complex [Lefeber et al., 2009].

Mannose-P-Dolichol Utilization Defect 1 (MPDU1) Protein Deficiency

MPDU1 encodes an ER membrane protein required for utilization of dolichol mannose in the synthesis of lipid-linked oligosaccharides and GPI anchors. MPDU1 appears to function as a chaperone for trafficking of dolichol mannose and dolichol glucosamine within the ER membrane [Schenk et al., 2001; Denecke et al., 2009; Surmacz and Swiezewska, 2011]. MPDU1 deficiency was initially reported in three unrelated patients, two from consanguineous families featuring early onset nystagmus and optic atrophy. Early visual loss was confirmed by electroretinography. The phenotype included early-onset seizures (~5 months of age), ichthyosis, hypotonia with elevated CK, global developmental delay, failure to thrive and recurrent vomiting. Brain MRI revealed generalized atrophy. One patient died from presumed seizure-related apnea [Schenk et al., 2001]. Several missense mutations were identified that appear to reduce mannosylation to some degree.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Although regarded as rare, disorders altering the synthesis and/or utilization of the dolichols may be underdiagnosed since routine characterization of transferrin glycosylation by isoelectric focusing (IEF) or liquid chromatography methods may lack the sensitivity and specificity required for their detection [Jaeken et al., 1994]. IEF of transferrin takes advantage of the negatively charged sialic acid residues residing on the end of oligosaccharide chains modifying glycosylated proteins. A type I pattern features significantly increased disialo-transferrin and asialotransferrin species and concomitant depletion of tetrasialo-transferrin, the predominant species in normal individuals, while less sialiated forms, including asialotransferrin (zero sialic acids present), accumulate in patients diagnosed with the so-called type II pattern, which is not seen in normal controls [Jaeken et al., 1994]. IEF of serum transferrin remains a prominent screening approach in the clinical biochemical genetics laboratory. DHDDS, SRD5A3, DPM1, DPM2, DPM3, and DK1 defects demonstrate Type I patterns. One should note, however, that IEF analysis of serum transferrin can be non-diagnostic for SRD5A3 deficiency in older individuals [Morava et al., 2010; Cantagrel and Lefeber, 2011; Zelinger et al., 2011]. DPM1 and two deficiencies were associated with an abnormal type I pattern, and abnormal lipid-linked oligosaccharides were detected in fibroblasts. In DPM2 deficiency, due to the combined N- and O-linked glycosylation defect, abnormal O-mannosylation in skeletal muscle was also confirmed [Kim et al., 2000; Ashida et al., 2006]. Only subtle type I abnormalities were detected in DPM3 deficiency, and a type I pattern was inconsistently present in MPDU1 deficiency [Denecke et al., 2009; Lefeber et al., 2009; Surmacz and Swiezewska, 2011].

Based upon the preceding observations, specific plasma evaluations for N- and O-linked glycans using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) or proteomic methodology, in addition to molecular characterization, may ultimately be required to identify all disorders involving the synthesis and utilization of the dolichols [He et al., 2012]. The use of cultured skin fibroblasts for assessment of lipid-linked oligosaccharides may also be beneficial, and for the disorders of O-mannosylation, specific immune-histochemical tests on biopsied muscle may be required [He et al., 2012]. Because the DMP complex affects multiple glycosylation/mannosylation pathways dependent upon dolichol mannose availability, IEF analysis of serum trans-ferrin alone may be insufficient for absolute identification [Ashida et al., 2006], and specific analyses of glycosylation in muscle may be required.

SUMMARY

Based upon the clinical phenotypes described, we consider it prudent that patients presenting with isolated RP, dilated cardiomyopathy, early onset seizure disorders not otherwise explained, ichthyosis and/or a muscular dystrophy phenotype be evaluated for disorders involving the synthesis and utilization of the dolichols, in addition to other disorders of glycosylation. The multisystem pathology of these disorders, and the diverse pathways of glycosylation that are interrupted, may require more sophisticated diagnostic protocols for their identification, and thus we recommend referral of appropriate samples to specialist laboratories with expertise in their identification to insure the most rapid and accurate diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Drs. F. D. Porter and W. A. Gahl for their assistance in manuscript preparation. Partial support from the Sterol and Isoprenoid Diseases (STAIR) consortium (U54HD61939), a component of the NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), and the NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR) is gratefully acknowledged (MH, JV, and KMG). The views expressed in written materials or publications do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention by trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Biographies

Lynne A. Wolfe is a Nurse Practitioner who cares for children and families affected with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) including inherited disorders of glycosylation. She is a co-investigator in the NIH Undiagnosed Diseases program targeting the discovery of new IEMs and the further characterization of rare presentations of previously identified disorders. She is a member of the faculty for the North American Metabolic Academy (NAMA) established by the Society of Inherited Metabolic Disorders and instructs in the areas of glycosylation disorders among others.

Eva Morava is a Professor of Pediatrics and a clinical biochemical geneticist at the Hayward Genetics Center at Tulane University, New Orleans, and also affiliated with the Nijmegen Center for Disorders of Glycosylation, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, IGMD, the Netherlands. Dr. Morava is an editor of the Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease (JIMD). She has played a lead role in the identification of multiple disorders of glycosylation.

Miao He is a biochemical geneticist whose major research interests include genetic disorders in protein glycosylation, cholesterol biosynthesis and fatty acid oxidation. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Genetics and the Director of the Emory Biochemical Genetics Laboratory at Emory University.

Jerry Vockley is a Professor of Pediatrics in the School of Medicine and a Professor of Human Genetics in the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh and serves as Chief of Medical Genetics at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. A particular area of clinical and laboratory expertise resides in the area of disorders of fatty acid oxidation. He is a principal investigator in the Sterol and Isoprenoid Diseases (STAIR) consortium of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network. Dr. Vockley is the co-founder of NAMA.

K. Michael Gibson is Section Head of Clinical Pharmacology in the College of Pharmacy at Washington State University. Board-certified in Clinical Biochemical Genetics, he is the past director of the Biochemical Genetics Laboratories at Oregon Health and Science University and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. He is Co-Editor-in-Chief of the JIMD, the official publication of the Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (SSIEM), and a Part-Editor of the Online Metabolic & Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (OMMBID).

References

- Ashida H, Maeda Y, Kinoshita T. DPM1, the catalytic subunit of dolichol-phosphate mannose synthase is tethered to and stabilized on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane by DPM3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:896–904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone R, Aiello C, Race V, Morava E, Foulquier F, Riemersma M, Passarelli C, Concolino D, Carella M, Santorelli F, Vleugels W, Mercuri E, Garozzo D, Sturiale L, Messina S, Jaeken J, Fiumara A, Wevers RA, Bertini E, Matthijis G, Lefeber D. DPM2-CDG: A muscular dystrophy-dystroglycanopathy syndrome with severe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ana.23632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantagrel V, Lefeber DJ. From glycosylation disorders to dolichol biosynthesis defects: A new class of metabolic diseases. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:859–867. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9301-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Walter EI, Parker G, Lapurga JP, Millan JL, Ikehara Y, Udenfriend S, Medof ME. Mammalian glycophosphatidylinositol anchor transfer to proteins and posttransfer deacylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9512–9517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denecke J, Kranz C. Hypoglycosylation due to dolichol metabolism defects. BBA Mol Basis Dis. 2009;1792:888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund EA, Freeze HH. The congenital disorders of glycosylation: A multifaceted group of syndromes. NeuroRx. 2006;3:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze HH. Human disorders in N-glycosylation and animal models. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1573:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze HH. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: CDG-1, CDG-II, and beyond. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:389–396. doi: 10.2174/156652407780831548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze HH, Aebi M. Altered glycan structures: The molecular basis of congenital disorders of glycosylation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Kratz LE, Michel JJ, Vellejo AN, Ferris L, Kelley RI, Hoover JJ, Jukic D, Gibson KM, Wolfe LA, Ramachandrian D, Zwick ME, Vockley J. Mutations in the human SC4MOL gene encoding a methyl sterol oxidase cause psoriasiform dermatitis, microcephaly, and developmental delay. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:976–984. doi: 10.1172/JCI42650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Matern D, Raymond KM, Wolfe LA. The congenital disorders of glycosylation. In: Garg U, Smith LD, Heese BA, editors. Laboratory diagnosis of inherited metabolic diseases. Washington, DC: AACC Press; 2012. pp. 179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Imbach T, Schenk B, Schollen E, Burda P, Stutz A, Grunewald S, Bailie NM, King MD, Jaeken J, Matthijs G. Deficiency of dolichol-phosphate-mannose synthase-1 causes congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ie. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:233–239. doi: 10.1172/JCI8691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeken J, Schachter H, Carchon H, De Cook P, Coddeville B, Spik G. Carbohydrate deficient glycoprotein syndrome typeII; a deficiency in golgi localized N-acetyl-glucosaminyltransferase II. Arch Dis Child. 1994;7:123–127. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahrizi K, Hu CH, Garshasbi M, Abedini SS, Ghdami S, Kariminejad R, Ullman R, Chen W, Ropers HH, Kuss AW, Najmabadi H, Tzschach A. Next generation sequencing in a family with autosomal recessive Kahrizi syndrome (OMIM 612713) reveals a homozygous frameshift mutation in SRD5A3. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:115–117. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapusta L, Zucker N, Frenckel G, Medalion B, Gal TB, Birk E, Mandel H, Nasser N, Morgenstern S, Zuckermann A, Lefeber DJ, Brouwer A, Wevers RA, Lorber A, Morava E. From discrete dilated cardiomyopathy to successful cardiac transplantation in congenital disorders of glycosylation due to dolichol kinase deficiency (DK1-CDG) Heart Fail Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9302-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasapkara CS, Tümer L, Ezgü FS, Hasanoğlu A, Race V, Matthijs G, Jaeken J. SRD5A3-CDG: A patient with a novel mutation. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2012;16:554–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Westphal V, Srikrishna G, Mehta DP, Peterson S, Filiano J, Karnes PS, Patterson MC, Freeze HH. Dolichol phosphate mannose synthase (DPM1) mutations define congenital disorder of glycosylation Ie (CDG-Ie) J Clin Invest. 2000;105:191–198. doi: 10.1172/JCI7302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz C, Jungeblut C, Denecke J, Erlekotte A, Sohlbach C, Debus V, Kehl HG, Harms E, Reith A, Reichel S, Gröbe H, Hammersen G, Schwarzer U, Marquardt T. A defect in dolichol phosphate biosynthesis causes a new inherited disorder with death in early infancy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:433–440. doi: 10.1086/512130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeber DJ, Schönberger J, Morava E, Guillard M, Huyben KM, Verrijp K, Grafakou O, Evangeliou A, Preijers FW, Manta P, Yildiz J, GrUnewald S, Spilioti M, van den Elzen C, Klein D, Hess D, Ashida H, Hofsteenge J, Maeda Y, van den Heuvel L, Lammens M, Lehle L, Wevers RA. Deficiency of Dol-P-Man synthase subunit DPM3 bridges the congenital disorders of glycosylation with the dystroglycanopathies. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeber DJ, de Brouwer APM, Morava E, Riemersma M, Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JHM, Absmanner B, Verrijp K, van den Akker WMR, Huijben K, Steenbergen G, van Reeuwijk J, Jozwiak A, Zucker N, Lorber A, Lammens M, Knopf C, van Bokhoven H, GrUnewald S, Lehle L, Kapusta L, Mandel H, Wevers RA. Autosomal recessive dilated cardiomyopathy due to DOLK mutations results from abnormal dystroglycan O-mannosylation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Tanaka S, Hino J, Kangawa K, Kinoshita T. Human dolichol-phosphate-mannose synthase consists of three subunits, DPM1, DPM2 and DPM3. EMBO. 2000;19:2475–2482. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcuzzi A, Crovella S, Monasta L, Vecchi Brumatti L, Gattorno M, Frenkel J. Mevalonate kinase deficiency: Disclosing the role of mevalonate pathway modulation in inflammation. Curr Pharm Des. 2012 doi: 10.2174/138161212803530835. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morava E, Wevers RA, Cantagrel V, Hoefsloot LH, Al-Gazali L, Schoots J, van Rooij A, Huijben K, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CMA, Jongmans MCJ, Sykut-Cegielska J, Hoffmann GF, Bluemel P, Adamowicz M, van Reeuwijk J, Ng BG, Bergman JEH, van Bokhoven H, Korner C, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Willemsen MA, Gleeson JG, Lehle L, de Brouwer APM, Lefeber DJ. A novel cerebello-ocular syndrome with abnormal glycosylation due to abnormalities in dolichol metabolism. Brain. 2010;133:3210–3220. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter FD, Herman GE. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:6–34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R009548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puoti A, Conzelmann A. Structural characterization of free glycolipids which are potential precursors for glycophosphati-dylinositol anchors in mouse thyoma cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22673–22680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf CP, Koster J, Katsonis P, Kratz L, Shchelochkov OA, Scaglia F, Kelley RI, Lichtarge O, Waterham HR, Shinawi M. Desmosterolosis-phenotypic and molecular characterization of a third case and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1597–1604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk B, Imbach T, Frank CG, Grubenmann CE, Raymond GV, Hurvtz H, Raas-Rothchild A, Luder AS, Jaeken J, Berger EG, Matthijs G, Hennett T, Aebi M. MPDU1 mutations underlie a novel human congenital disorder of glycosylation, designated type If. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1687–1695. doi: 10.1172/JCI13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton CH. Role of a disordered steroid metabolome in the elucidation of sterol and steroid biosynthesis. Lipids. 2012;47:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3605-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmacz L, Swiezewska E. Polyisoprenoids-secondary metabolites or physically important superlipids? Biomed Biophys Res Commun. 2011;407:627–632. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinger L, Banin E, Obolensky A, Mizrahi-Meissonnier L, Beryozkin A, Bandah-Rozenfeld D, Frenkel S, Ben-Yosef T, Merin S, Schwartz SB, Cideciyan AV, Jacobson SG, Sharon D. A missense mutation in DHDDS, encoding dehydrodolichyl diphosphate synthase, is associated with autosomal-recessive retinitis pigmentosa in Ashkenazi Jews. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Züchner S, Dallman J, Wen R, Beecham G, Naj A, Farooq A, Kohli MA, Whitehead PL, Hulme W, Konidari I, Edwards YJK, Cai G, Peter I, Seo D, Buxbaum JD, Haines JL, Blanton S, Young J, Alfonso E, Vance JM, Lam BL, Peric ak-Vance MA. Whole-exome sequencing links a variant in DHDDS to retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]