Abstract

Background & Aims

Vitamin D deficiency is common among patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis). The effects of low plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25[OH]D) on outcomes other than bone health are understudied in patients with IBD. We examined the association between plasma level of 25(OH)D and risk of cancers in patients with IBD.

Methods

From a multi-institutional cohort of patients with IBD, we identified those with at least 1 measurement of plasma 25(OH)D. The primary outcome was development of any cancer. We examined the association between plasma 25(OH)D and risk of specific subtypes of cancer, adjusting for potential confounders in a multivariate regression model.

Results

We analyzed data from 2809 patients with IBD and a median plasma level of 25(OH)D of 26 ng/mL. Nearly one-third had deficient levels of vitamin D (<20 ng/mL). During a median follow-up period of 11 y, 196 patients (7%) developed cancer, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (41 cases of colorectal cancer). Patients with vitamin D deficiency had an increased risk of cancer (adjusted odds ratio=1.82; 95% CI, 1.25–2.65) compared to those with sufficient levels. Each 1 ng/mL increase in plasma 25(OH)D was associated with an 8% reduction in risk of colorectal cancer (odds ratio=0.92; 95% CI, 0.88–0.96). A weaker inverse association was also identified for lung cancer.

Conclusion

In a study of from 2809 patients with IBD, low plasma level of 25(OH)D was associated with an increased risk of cancer—especially colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, risk factor, colorectal cancer, vitamin D, malignancy

INTRODUCTION

The effects of vitamin D on bone metabolism are well recognized1, 2. However, there is increasing recognition of the pleotropic effect of vitamin D on a spectrum of diseases including autoimmunity, cardiovascular health, and cancer3–5. Epidemiologic studies suggest an increased risk of and mortality from cancer in residents of higher latitudes with lower ultraviolet light (UV) exposure, an association that may be mediated in part through vitamin D1, 3, 6. Furthermore, prospective cohorts have demonstrated an inverse association between plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D], the most stable measure of vitamin D status, and cancers of the colon, breast, and prostate7–12. The strongest evidence of an anti-carcinogenic effect of vitamin D comes from a randomized controlled trial of over a thousand women where supplementation with calcium and vitamin D reduced the risk of cancer by nearly 60%13.

Deficiency of vitamin D is common in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD; Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), and may even precede the diagnosis of IBD14–16. However, there has been only limited study of the longitudinal consequences of low vitamin D in patients with IBD, particularly outside its effect on bone metabolism. Cross-sectional studies suggested an association between vitamin D status and disease activity17, 18, a finding that was confirmed in a study from our group demonstrating an inverse association with IBD-related hospitalizations and surgery19. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that normalization of plasma 25(OH)D is associated with a reduction in this risk of IBD-related surgery19. No prior studies have examined the effect of vitamin D status on risk of cancers in patients with IBD.

Using a well-characterized multi-institutional IBD cohort, we examined the association between plasma 25(OH)D and risk of cancer. We then examined the association with specific types of cancers to see if the anti-carcinogenic effect of vitamin D is specific to certain cancer sub-types in the IBD population.

METHODS

Study cohort

The development of our study cohort has been described in detail in previous publications19, 20. In brief, we first identified all potential IBD patients by the presence of one or more International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for CD (555.x) or UC (556.x) in our electronic medical record (EMR). The EMR, initiated in 1986, covers two major teaching hospitals and affiliated community hospitals in the Greater Boston area and serves a population of over 4 million patients. From this cohort, we developed a classification algorithm incorporating codified data (ICD-9-CM codes for disease complications), use of IBD-related medications identified through the electronic prescriptions, as well as free-text concepts (such as the term “Crohn’s disease”) identified using natural language processing. Our classification algorithm had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 97% that was confirmed by medical record review of an independent sample. Our final IBD cohort consisted of 5,506 patients with CD and 5,522 with UC.

Measurement of plasma 25(OH)D

The present study included all patients who had at least one available plasma 25(OH)D measured as part of routine clinical care. Prior studies have demonstrated good intra-class correlation and stability of measures of plasma vitamin D with intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) of 0.72 and 0.52 at 3 and 10 years respectively, comparable to the ICC for plasma cholesterol, an accepted marker of long-term cardiovascular risk21. Patients who had their vitamin D status assessed only after the diagnosis of cancer were excluded. Plasma 25(OH)D was measured using radioimmunoassay prior to 2008 and high performance liquid chromatography since. The lowest plasma 25(OH)D value was used to classify patients as deficient (< 20ng/mL), insufficient (20–29.9ng/mL), and sufficient (≥ 30ng/mL) according to current guidelines. IBD patients who had at least one measured 25(OH)D were similar in age but more likely to be female, require immunomodulator or biologic therapy, and undergo an IBD-related surgery or hospitalization compared to the rest of the patients in our IBD cohort.

Variables and Outcomes

We extracted information on patient age, gender, race (white, black, or other) as well as age at first diagnosis code of IBD. We ascertained use of IBD-related medications including 5-aminosalicylates, systemic corticosteroids, immunomodulators (6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, and methotrexate) and anti-TNF biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol), and dates of IBD-related hospitalization and surgery.

Our primary outcome was diagnosis code in the EMR of any malignancy excluding non-melanoma skin cancers. This was further subdivided into solid organ tumors (ICD-9-CM 140–172.9, 174–195.8), hematologic malignancies including leukemia and lymphoma (ICD-9-CM 200–208.9), and metastatic cancers (ICD-9-CM 196–199.1). We then stratified by type of cancer for the most common malignancies including breast cancer (174.x), colorectal cancer (153.x–154.x), lung cancer (162.x), prostate cancer (185.x), melanoma (172.x), and pancreatic cancer (157.x). Chart review of random sets of 50 patients with each cancer type revealed a PPV of 80–90%.

Statistical Analysis

All data analysis was performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Continuous variables were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR); categorical variables were expressed as proportions. The t-test was used to compare continuous variables while the chi-square test (with Fisher’s exact modification when appropriate) was used to compare categorical variables. Univariate logistic regression was used to examine the association between vitamin D status and diagnosis of cancer. Vitamin D levels were modeled both as a continuous variable in increments of 1ng/mL as well as an ordinal variable stratified as described above. Planned subgroup analyses were performed by type of cancer. We also examined if the association with vitamin D status differed by gender, IBD type, or immunosuppressant use. To examine if the difference in cancer diagnoses was due to greater intensity of healthcare utilization in those with low vitamin D levels (and consequently, richer follow-up in our medical system), we adjusted for a variable termed “fact density”. Each outpatient visit, inpatient stay, laboratory test, radiology exam, inpatient or outpatient procedure constitutes a ‘fact’. Dividing this by duration of follow-up in our system yields a “fact density” that is a measure of intensity of healthcare utilization per unit time of follow-up within our healthcare system. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 in the multivariate model indicated independent statistical significance. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Partners Healthcare.

RESULTS

Study cohort

Our cohort included 2,809 IBD patients with a median age of 46 years (IQR 32 – 60 years) (Table 1). Over half the cohort were women (61%) and a majority were white (87%). The median age at first diagnosis code for IBD was 38 years. Nearly half the patients required immunomodulators while one-quarter were exposed to anti-TNF biologic therapy. The median plasma 25(OH)D level in our cohort was 26ng/mL (IQR 17 – 35ng/mL). Nearly one-third of the cohort were deficient in vitamin D (< 20ng/mL), and a similar proportion had insufficient (20–29.9ng/mL) levels. During a median follow-up of 11 years, 196 patients (7%) developed cancer excluding non-melanoma skin cancer. Seventy-two patients (3%) developed metastatic cancer. The median interval between measurement of 25(OH)D and first diagnosis code for cancer was 627 days (IQR 268 – 1,380 days).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Characteristic | N = 2,809 (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) (in years) | 46 (32 – 60) |

| Female | 1,712 (61%) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1,244 (44%) |

| Median age at first IBD diagnosis code (IQR) (in years) | 38 (27 – 52) |

| Ever biologic use | 629 (22%) |

| Immunomodulator use | 1,129 (40%) |

| IBD-related hospitalizations | 1,135 (40%) |

| Bowel resection | 453 (16%) |

| Race | |

| White | 2,444 (87%) |

| Black | 213 (8%) |

| Other | 152 (5%) |

| Median duration of follow-up (IQR) | 11 (5 – 18) |

| Median plasma 25(OH)D level | 26 (17 – 35) |

| Vitamin D status | |

| Deficient | 885 (32%) |

| Insufficient | 807 (29%) |

| Normal | 1,117 (40%) |

| Any cancer | 196 (7%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 72 (3%) |

IQR – interquartile range;

Plasma vitamin D and risk of cancer

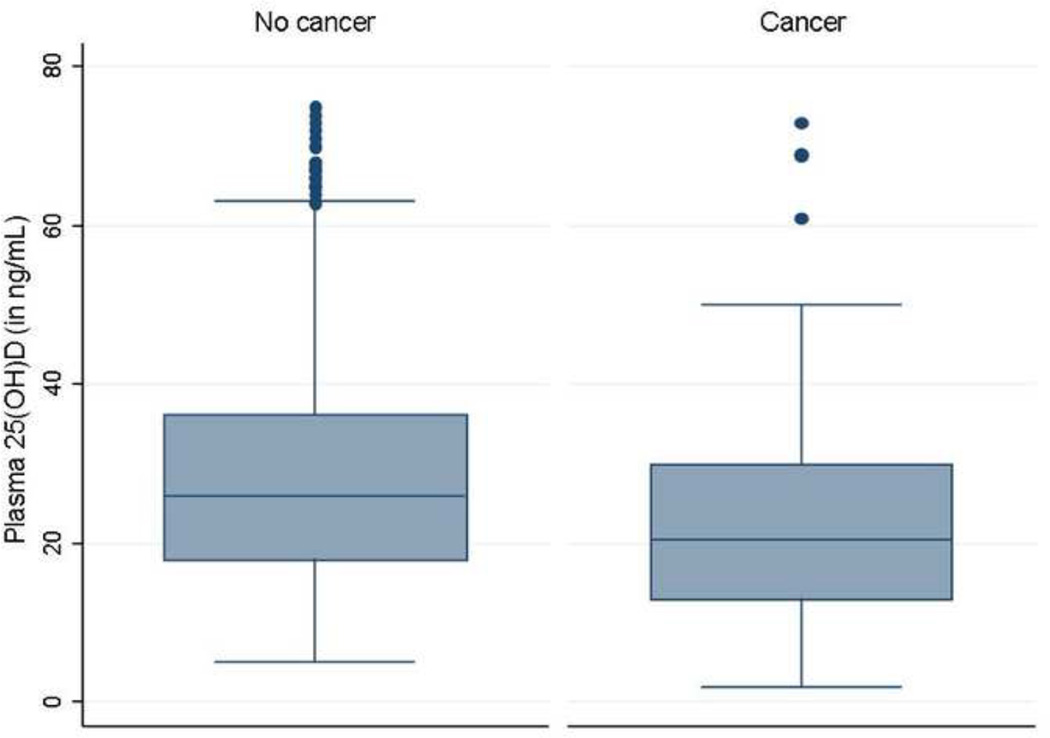

The mean plasma 25(OH)D in patients who subsequently developed cancer was 5ng/mL lower than in those who did not develop cancer (22.8 ng/mL vs. 27.5 ng/mL, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Among the 881 patients who had deficient levels of vitamin D, 88 (10%) developed any cancer compared to 4% of patients with normal levels of plasma 25(OH)D (p < 0.001), yielding an odds ratio (OR) of 2.38 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.67 – 3.39) (Table 2). This difference remained independently significant on multivariate analysis adjusting for age, gender, race, season of measurement, duration of follow-up, use of immunosuppression, and type of IBD (adjusted OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.25 – 2.65). Patients with insufficient levels of plasma 25(OH)D had an intermediate cancer risk.

Figure 1.

Plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D] levels in patients, stratified by subsequent diagnosis of cancer

Table 2.

Plasma 25(OH)D and risk of all malignancy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases

| Vitamin D stratum | No cancer [N(%)] |

Cancer [N(%)] |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1,065 (95%) | 52 (5%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 20 – 29.9 ng/mL | 741 (92%) | 66 (8%) | 1.82 (1.25 – 2.66) | 1.69 (1.15 – 2.51) |

| < 20 ng/mL | 793 (90%) | 92 (10%) | 2.38 (1.67 – 3.38) | 1.82 (1.25 – 2.65) |

OR – odds ratio, CI – confidence interval

Adjusted for age, gender, race, season of measurement, duration of follow up, immunosuppression use, and IBD type

Each 1ng/mL increase in plasma 25(OH)D was associated with a similar reduction in risk of non-metastatic (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.95 – 1.00) and metastatic cancer (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96 – 1.00, p < 0.05 for both) (Table 3). The magnitude of reduction in risk was similar across IBD types and gender. Adjusting for intensity of healthcare utilization did not result in significant changes to our final estimates (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.24 – 2.69).

Table 3.

Plasma 25(OH)D and risk of malignancy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, stratified by subgroups

| Subgroup | Adjusted odds ratio║‡ | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| By metastatic status | |||

| Non-metastatic | 0.97 | 0.95 – 1.00 | 0.02 |

| Metastatic cancer | 0.98 | 0.96 – 1.00 | 0.01 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0.97 | 0.95 – 0.99 | 0.01 |

| Female | 0.98 | 0.97 – 1.00 | 0.03 |

| IBD type | |||

| Crohn’s disease | 0.98 | 0.96 – 1.00 | 0.02 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 0.98 | 0.96 – 1.00 | 0.02 |

For each 1ng/mL increase in plasma 25(OH)D

Adjusted for age, gender, race, season of measurement, duration of follow up, immunosuppression use, and IBD type

Vitamin D and incidence of specific cancers

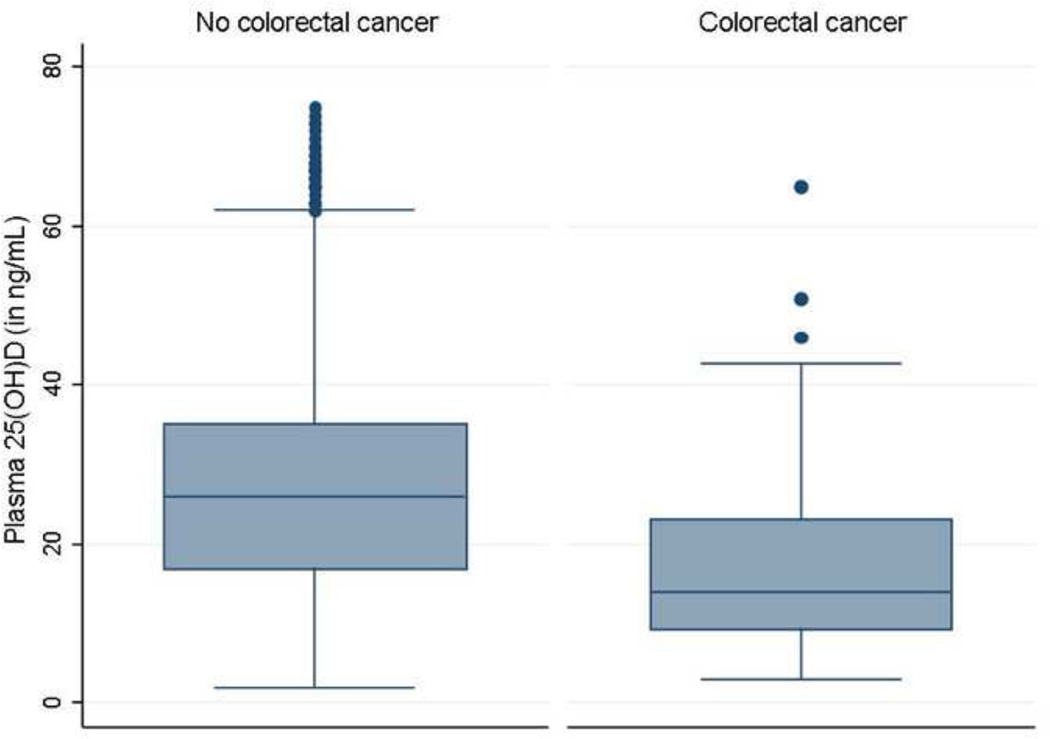

We then examined if the association with plasma 25(OH)D was confined to specific cancers. The strongest inverse association was identified for colorectal cancer with an 6% reduction in risk for each 1ng/mL increase in plasma 25(OH)D (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.91 – 0.97) (Table 4, Figure 2). A statistically significant inverse association was also identified for lung cancer (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90 – 0.99). None of the other common cancers demonstrated a significant association.

Table 4.

Plasma 25(OH)D and risk of individual cancers in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases

| Type of cancer | Number of cases | Adjusted OR (95% CI) ║‡ |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colon cancer† | 41 | 0.94 (0.91 – 0.97) | 0.01 |

| Breast cancer | 31 | 0.99 (0.96 – 1.02) | 0.47 |

| Prostate cancer | 19 | 1.00 (0.97 – 1.05) | 0.82 |

| Hematologic | 45 | 0.98 (0.95 – 1.00) | 0.10 |

| Lung cancer | 19 | 0.95 (0.90 – 0.99) | 0.02 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 13 | 0.97 (0.92 – 1.02) | 0.26 |

| Melanoma | 19 | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.05) | 0.50 |

For each 1ng/mL increase in plasma 25(OH)D

Adjusted for age, gender, race, season of measurement, duration of follow up, immunosuppression use, and IBD type

Additionally adjusted for presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis

Figure 2.

Plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D] levels in patients, stratified by subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer

DISCUSSION

Vitamin D has pleiotropic effects on the immune system4, 16, 22–24 and has been with risk of autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, and cancer4, 5, 23–25. However, no prior studies have examined the association between vitamin D and cancer in chronic immune-mediated diseases where mechanisms of cancer may be distinct and other competing factors may influence both vitamin D status and risk of cancer. In a multi-institutional IBD cohort, we demonstrate an inverse association between plasma 25(OH)D and risk of malignancy, with statistically significant inverse associations with colorectal cancer and lung cancer.

Vitamin D deficiency is common in patients with IBD with most studies reporting up to a third of patients being deficient, and an equal proportion with insufficient levels14, 16–18. Such deficiency does not appear to be solely a consequence of the disease17, 18 as similar levels of deficiency have been reported in those with newly diagnosed IBD14, and may even precede the diagnosis of IBD15. There has been limited examination of the longitudinal implications of vitamin D deficiency in an IBD population. Low plasma 25(OH)D is associated with increased risk of IBD-related hospitalizations and surgery; normalization of plasma 25(OH)D is associated with a reduction in this risk19. The main findings from our study suggest that, in addition to its association with disease activity, low vitamin D levels in patients with IBD may also contribute to increased risk of malignancy, in particular that of colorectal cancer. This provides further evidence supporting incorporation of routine assessment of vitamin D status in the care of IBD patients and appropriate treatment to prevent long-term complications.

Few studies have examined the association between vitamin D status and overall risk of cancer. A large cohort study of 9,949 men and women followed for a median of 8 years found no association between vitamin D and overall cancer or site-specific cancer incidence26. However, in another prospective study from Germany, vitamin D deficiency was associated with an increased risk for overall mortality, cardiovascular and cancer mortality27. A randomized controlled trial of 1,179 postmenopausal women randomized to calcium and vitamin D (1000mg/1100 units) supplementation demonstrated a 60% reduction in cancer risk with vitamin D supplementation and an even stronger effect excluding cancers diagnosed within the first year13. While the Women’s Health Initiative trials of calcium and vitamin D supplementation did not identify a similar benefit, this could potentially be explained by the lower dose of vitamin D (400 IU daily) used in the trials28. A statistically significant reduction in CRC risk was identified in the WHI trial in patients who were noted to have a significant increase in their plasma 25(OH)D29. Considerable biological plausibility suggests an anti-cancer effect of vitamin D. The local production of 1,25-dihydroxy D [1,25 (OH)2D3] inhibits cancer cells through pathways involving cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor synthesis, Wnt/β-catenin, mitogen activated protein(MAP)-kinase, and nuclear factor-κB3. In addition, 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes pro-apoptotic mechanisms and induction of autophagy leading to death of cancer cells3, 30–33.

There is particularly strong evidence supporting a role of vitamin D in the development of sporadic colon cancer7, 11. In large epidemiologic studies, low plasma 25(OH)D was associated with an increased risk of CRC in men and women7, 9, 11. Expression of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) is downregulated in colitis-associated dysplasia and may be involved in progression to CRC34. The Wnt/β-catenin pathways also plays a role in the pathogenesis of CRC; 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits signaling through this pathway35, 36. Finally, vitamin D could enhance differentiation of colon cancer cells through induction of adhesion molecules such as E-cadherin3. However, there are significant differences in the molecular pathology of colitis-associated cancer compared to sporadic CRC. Mutation in the tumor suppressor gene p53 occurs earlier and more frequently in colitis-associated cancer than sporadic CRC37. In contrast, mutation at the APC gene occurs early in sporadic colon cancer. Furthermore, epigenetic differences may exist between sporadic and colitis-associated cancer. Our findings suggest that the role of vitamin D in the development of CRC may be through pathways that are common to both sporadic and colitis-associated cancers.

There is less biologic data to explain the association between the vitamin D and lung cancer33. First, this result could potentially be confounded by smoking status which is the strongest risk factor for lung cancer. However, smoking has not been shown to be consistently associated with vitamin D status and is thus unlikely to be differentially distributed to explain the association. In a study by Afzal et al. from the Copenhagen heart study, lower plasma 25(OH)D was associated with an increased risk of all tobacco related cancers including lung cancer (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.09 – 1.31)38. In a Norwegian cohort, early mortality within 18 months of diagnosis was higher in patients diagnosed with lung cancer during the winter/spring months when compared to those diagnosed during summer39.

There are a few implications to our findings. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to demonstrate an association between plasma 25(OH)D and risk of malignancy, particularly CRC in an IBD cohort. Prior observational studies have demonstrated that normalization of vitamin D status can be associated with a reduction in risk of surgeries and hospitalizations, particularly in patients with CD19. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial by Jorgensen et al. demonstrate a trend towards reduced rates of relapse in patients supplemented with vitamin D compared to placebo40. Our findings suggest that reduction in colorectal cancer risk may also be achievable through supplementation with vitamin D though a prospective clinical trial to examine this hypothesis would likely be prohibitively large and require considerable length of follow-up.

There are several limitations to our study. First, because our cohort is based primarily at two referral centers, the population may be skewed towards greater severity of underlying IBD. Second, we did not have information on body mass index or smoking status, both of which have been associated with overall risk of malignancy, and colorectal cancer. However, an effect of BMI and smoking on IBD-related cancers has not been noted previously. Third, we did not have information on medications such as aspirin and NSAID both of which have been inversely associated with development of CRC. However, long-term use of such medications is uncommon in patients with IBD due to their potential to trigger disease relapses. Fourth, we were not able to perform fine adjustments for disease duration and activity, which may have relevance with regards to colorectal cancer risk. However, it is also unclear if disease activity is a confounder, or could plausibly be within the causal pathway given the association between low vitamin D and disease severity, and impact of normalization of vitamin D on prevention of relapse and reducing IBD related surgeries and hospitalization. Fifth, for inclusion in our study, patients had to have their vitamin D level measured within our healthcare system. For a cancer diagnosis to be captured, the patient should have had at least one ICD-9 code for the relevant cancer within our system (at diagnosis or subsequently on referral for surgical or oncologic management). Finally, measurement of vitamin D was as part of routine clinical care and not systematically performed across all patients; fewer than half our IBD cohort had a measured plasma 25(OH)D. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this remains the largest cohort containing information on vitamin D status of patients with IBD. The diagnosis of cancer was made based on codes within our EMR and not using systematic links to regional or national cancer registries. However, one would expect such misclassification to bias the results toward the null, making ours a conservative estimate.

In conclusion, using a large multi-institutional IBD cohort, we demonstrated that low plasma 25(OH)D is associated with increased risk of metastatic and non-metastatic cancers. In particular, the association was strongest for colorectal cancer. Assessment of vitamin D status should routinely be part of comprehensive care of patients with IBD.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The study was supported by NIH U54-LM008748. A.N.A is supported by funding from the American Gastroenterological Association and from the US National Institutes of Health (K23 DK097142). K.P.L. is supported by NIH K08 AR060257 and the Katherine Swan Ginsburg Fund. E.W.K is supported by grants from the NIH (K24 AR052403, P60 AR047782, R01 AR049880).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial conflicts of interest: None

Specific author contributions:

An author may list more than one contribution, and more than one author may have contributed to the same element of the work

Study concept – Ananthakrishnan

Study design – Ananthakrishnan

Data Collection – Ananthakrishnan, Gainer, Cagan, Cai, Cheng, Churchill, Kohane, Shaw, Liao, Szolovits, Murphy

Analysis – Ananthakrishnan, Cai, Cheng,

Preliminary draft of the manuscript – Ananthakrishnan

Approval of final version of the manuscript – Ananthakrishnan, Gainer, Cagan, Cai, Cheng, Churchill, Kohane, Shaw, Liao, Szolovits, Murphy

REFERENCES

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen CJ. Clinical practice. Vitamin D insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:248–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1009570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wacker M, Holick MF. Vitamin D - effects on skeletal and extraskeletal health and the need for supplementation. Nutrients. 2013;5:111–148. doi: 10.3390/nu5010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantorna MT, Zhu Y, Froicu M, Wittke A. Vitamin D status, 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3, and the immune system. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1717S–1720S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1717S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1678S–1688S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1678S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant WB. Ecological studies of the UVB-vitamin D-cancer hypothesis. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:223–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feskanich D, Ma J, Fuchs CS, Kirkner GJ, Hankinson SE, Hollis BW, Giovannucci EL. Plasma vitamin D metabolites and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1502–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giovannucci E. Strengths and limitations of current epidemiologic studies: vitamin D as a modifier of colon and prostate cancer risk. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S77–S79. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovannucci E. Vitamin D and cancer incidence in the Harvard cohorts. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, Hollis BW, Fuchs CS, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:451–459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu K, Feskanich D, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Hollis BW, Giovannucci EL. A nested case control study of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and risk of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1120–1129. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer SR, Hankinson SE, Bertone-Johnson ER, Ding EL. Plasma vitamin D levels, menopause, and risk of breast cancer: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2013;92:123–131. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182943bc2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leslie WD, Miller N, Rogala L, Bernstein CN. Vitamin D status and bone density in recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease: the Manitoba IBD Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1451–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Bao Y, Korzenik JR, Giovannucci EL, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, Chan AT. Higher predicted vitamin d status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:482–489. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narula N, Marshall JK. Management of inflammatory bowel disease with vitamin D: beyond bone health. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph AJ, George B, Pulimood AB, Seshadri MS, Chacko A. 25 (OH) vitamin D level in Crohn's disease: association with sun exposure & disease activity. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulitsky A, Ananthakrishnan AN, Naik A, Skaros S, Zadvornova Y, Binion DG, Issa M. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: association with disease activity and quality of life. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:308–316. doi: 10.1177/0148607110381267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ananthakrishnan AN, Cagan A, Gainer VS, Cai T, Cheng SC, Savova G, Chen P, Szolovits P, Xia Z, De Jager PL, Shaw SY, Churchill S, Karlson EW, Kohane I, Plenge RM, Murphy SN, Liao KP. Normalization of Plasma 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D Is Associated with Reduced Risk of Surgery in Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182902ad9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ananthakrishnan AN, Cai T, Savova G, Cheng SC, Chen P, Perez RG, Gainer VS, Murphy SN, Szolovits P, Xia Z, Shaw S, Churchill S, Karlson EW, Kohane I, Plenge RM, Liao KP. Improving Case Definition of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Electronic Medical Records Using Natural Language Processing: A Novel Informatics Approach. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1411–1420. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828133fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotsopoulos J, Tworoger SS, Campos H, Chung FL, Clevenger CV, Franke AA, Mantzoros CS, Ricchiuti V, Willett WC, Hankinson SE, Eliassen AH. Reproducibility of plasma and urine biomarkers among premenopausal and postmenopausal women from the Nurses' Health Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:938–946. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. D-hormone and the immune system. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2005;76:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting evidence for vitamin D as an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1136–1142. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim WC, Hanauer SB, Li YC. Mechanisms of disease: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:308–315. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantorna MT. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis: an update. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:S135–S138. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ordonez-Mena JM, Schottker B, Haug U, Muller H, Kohrle J, Schomburg L, Holleczek B, Brenner H. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and cancer risk in older adults: results from a large German prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:905–916. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schottker B, Haug U, Schomburg L, Kohrle J, Perna L, Muller H, Holleczek B, Brenner H. Strong associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer, and respiratory disease mortality in a large cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:782–793. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.047712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunner RL, Wactawski-Wende J, Caan BJ, Cochrane BB, Chlebowski RT, Gass ML, Jacobs ET, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Larson J, Margolis KL, Millen AE, Sarto GE, Vitolins MZ, Wallace RB. The effect of calcium plus vitamin D on risk for invasive cancer: results of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) calcium plus vitamin D randomized clinical trial. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:827–841. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.594208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Brunner RL, O'Sullivan MJ, Margolis KL, Ockene JK, Phillips L, Pottern L, Prentice RL, Robbins J, Rohan TE, Sarto GE, Sharma S, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wallace RB, Whitlock E, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black HR, Bonds DE, Brzyski RG, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, Cochrane B, Garland C, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell FA, Jackson RD, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kooperberg CL, Kuller LH, LaCroix AZ, Lane DS, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Lewis CE, Limacher MC, Manson JE. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:684–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:684–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan AV, Feldman D. Mechanisms of the anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory actions of vitamin D. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:311–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nemazannikova N, Antonas K, Dass CR. Vitamin D: Metabolism, molecular mechanisms, and mutations to malignancies. Mol Carcinog. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mc.21999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton R, O'Connell MA. Vitamin D: potential in the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu R, Wu S, Xia Y, Sun J. The Vitamin D Receptor, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, and Colon Cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2013;8:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s11888-011-0114-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larriba MJ, Ordonez-Moran P, Chicote I, Martin-Fernandez G, Puig I, Munoz A, Palmer HG. Vitamin D receptor deficiency enhances Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and tumor burden in colon cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pendas-Franco N, Aguilera O, Pereira F, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Munoz A. Vitamin D and Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in colon cancer: role and regulation of DICKKOPF genes. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2613–2623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sebastian S, Hernandez V, Myrelid P, Kariv R, Tsianos E, Toruner M, Marti-Gallostra M, Spinelli A, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Yuksel ES, Gasche C, Ardizzone S, Danese S. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: Results of the 3rd ECCO pathogenesis scientific workshop (I) J Crohns Colitis. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afzal S, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Low plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of tobacco-related cancer. Clin Chem. 2013;59:771–780. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.201939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porojnicu AC, Robsahm TE, Dahlback A, Berg JP, Christiani D, Bruland OS, Moan J. Seasonal and geographical variations in lung cancer prognosis in Norway. Does Vitamin D from the sun play a role? Lung Cancer. 2007;55:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorgensen SP, Agnholt J, Glerup H, Lyhne S, Villadsen GE, Hvas CL, Bartels LE, Kelsen J, Christensen LA, Dahlerup JF. Clinical trial: vitamin D3 treatment in Crohn's disease - a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:377–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]