Abstract

Microbial species participate in the genesis of a substantial number of malignancies—in conservative estimates, at least 15% of all cancer cases are attributable to infectious agents. Little is known about the contribution of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiome to the development of malignancies. Resident microbes can promote carcinogenesis by inducing inflammation, increasing cell proliferation, altering stem cell dynamics, and producing metabolites such as butyrate, which affect DNA integrity and immune regulation. Studies in humans and rodent models of cancer have identified effector species and relationships among members of the microbial community in the stomach and colon that increase the risk for malignancy. Strategies to manipulate the microbiome, or the immune response to such bacteria, could be developed to prevent or treat certain GI cancers.

Keywords: cancer, inflammation, bacteria

Introduction

Humans are colonized by a myriad of microbes including bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses, although bacteria are the most abundant and well-studied component. The composition of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiome is shaped by a variety of factors including diet, additional environmental elements, and the genetic background of the host. The GI microbiota is a complex ecosystem that contains >3 million genes, encoding enzymes that generate metabolites that can influence health as well as disease1, 2.

Cancer of the GI tract is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Genetic factors have been identified that clearly increase cancer risk, including Apc mutations that cause familial adenomatous polyposis and E-cadherin mutations that lead to hereditary diffuse-type gastric cancer. However, non-genetic factors more broadly affect most GI cancers. Microbial species participate in the genesis of a substantial number of malignancies worldwide; in conservative estimates, more than 15% of all cancer cases can be attributed to infectious agents, for a neoplastic burden of 1.2 million cases/year3. Residential microbes in the GI tract can alter cancer risk by inducing oxidative and nitrosative DNA damage in response to chronic inflammation, increasing cell proliferation, altering stem cell dynamics, and producing mutagenic metabolites such as butyrate. The GI microbiota can also constrain or facilitate tumor growth by altering immune surveillance mechanisms and affecting the metabolism of chemotherapeutic agents1, 2. In this review, we discuss emerging concepts and provide specific examples for the role of the GI microbiome in the development of malignancies that arise within this niche. We will focus on gastric and colonic malignancies, since these have been most thoroughly investigated, and will also briefly discuss esophageal cancers.

Gastric Cancer

Gastric adenocarcinoma is the second-leading cause of cancer-related death in the world4,5. Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterial species that selectively colonizes gastric epithelium; chronic infection with this organism is the strongest identified risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma, prompting the World Health Organization to designate H pylori as a class I carcinogen. Approximately 660,000 new cases of gastric cancer/year are attributable to H pylori, making this pathogen the most common infectious agent linked to any malignancy3. However, only a percentage of colonized persons develop neoplasia. Risk is associated with H pylori strain, variations in host responses governed by genetic diversity, and/or specific interactions between host, microbial, and environmental determinants.

One H pylori determinant that influences cancer risk is the cag pathogenicity island (PAI). Genes within the cag PAI encode an antigenic effector protein (CagA) as well as proteins that form a type IV bacterial secretion system (T4SS) that exports CagA from adherent H pylori into host cells6–9. H pylori strains that harbor the cag PAI (cag+ strains) are associated with a significantly increased risk of distal gastric cancer compared to cag− strains10. Following translocation, CagA undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation by Src and Abl kinases; phospho-CagA subsequently interacts with and activates several host cell proteins, including a phosphatase (SHP2), leading to morphological alterations such as cell scattering and elongation6, 11, 12. Non-phosphorylated CagA also exerts effects within host cells that affect oncogenesis. Unmodified CagA directly binds PAR1b, which regulates cell polarity, and inhibits its kinase activity—an interaction that promotes loss of polarity13. Non-phosphorylated CagA associates with the epithelial tight-junction scaffolding protein ZO1 and the transmembrane protein junction adhesion molecule-A (JAMA) to cause ineffective assembly of tight junctions at sites of bacterial attachment14. Unmodified CagA also activates β-catenin, leading to transcriptional upregulation of genes implicated in cancer15–17. The CagA protein of certain H pylori strains can stimulate expression of IL8 by activating the transcription factor NFκB18, thereby contributing to neutrophil infiltration within the gastric mucosa. CagA also induces DNA damage in vitro and in rodent models of infection—results that have been validated in human subjects colonized with H pylori cag+ strains19. Contact between cag+ strains and host cells therefore activates multiple signaling pathways that may increase the risk for malignant transformation during prolonged colonization.

Another H pylori constituent linked to the development of gastric cancer is the secreted VacA toxin20. VacA causes a wide assortment of alterations in gastric epithelial cells, including vacuolation, altered plasma and mitochondrial membrane permeability, autophagy, and apoptotic cell death20. All H pylori strains possess vacA, but there is marked variation in vacA sequences among strains. The regions of greatest diversity are localized to the 5' region of the gene, which encodes the signal sequence and amino-terminus of the secreted toxin (allele types s1a, s1b, s1c, or s2), an intermediate region (allele types i1 or i2), and a mid-region (allele types m1 or m2)21, 22. Strains that contain type s1, i1 and m1 forms of vacA are associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer than strains that contain type s2, i2 and m2 forms22.

VacA and CagA can also counter-regulate each other to affect host cell responses. Specifically, CagA antagonizes VacA-induced apoptosis and activates a cell survival pathway mediated by the MAPK ERK and the anti-apoptotic protein MCL123. CagA also activates NFAT and EGFR signaling—processes that are inhibited by VacA23.

Recently, exciting data have shown that the opposing effects of CagA and VacA may be cell-lineage specific. The Wnt target gene Lgr5 encodes an orphan G protein-coupled receptor and marks a self-renewing, multipotent stem cell population responsible for long-term renewal of gastric epithelium24. Lgr5+ epithelial cells have higher levels of oxidative DNA damage than Lgr5-negative cells in H pylori-infected persons with gastric cancer25, indicating that H pylori specifically target Lgr5+ epithelial cells. In transgenic mice that over-express Leb, H pylori adhere directly to gastric epithelial cells26. Genetic ablation of parietal cells in Leb-expressing transgenic mice permits the gastric epithelial stem cell population to expand, which is accompanied by increased H pylori colonization and inflammation within glandular epithelium27,28. Delineation of this stem cell transcriptome has identified several pathways that are over-represented and of particular importance for carcinogenesis, including Wnt activation of β-catenin29 which is, in turn, activated by CagA-mediated signaling15, 16. In differentiated gastric epithelial cells, binding of VacA to LRP1, a specific receptor on the epithelial cell surface, leads to autophagic elimination of CagA30. Importantly, gastric epithelial cells that express a stem cell marker, CD44 variant9, fail to degrade CagA; these findings have been verified in vivo30. A subpopulation of host cells with progenitor-like features therefore appear to be uniquely susceptible to the effects of a microbial oncoprotein, which may lower the threshold for carcinogenesis.

Host genetic factors also influence the risk of gastric cancer among H pylori-infected persons. IL1β is an inflammatory cytokine that inhibits gastric acid secretion, and production of IL1β is increased in the gastric mucosa of infected vs uninfected persons31. Polymorphisms within the IL1β gene cluster that increase IL1β production are associated with significant increases in risk for hypochlorhydria, gastric atrophy, and distal gastric adenocarcinoma compared with low-expression IL1b genotypes32–34. The presence of a virulent strain of H pylori in a genetically susceptible person further augments the risk for gastric cancer. Persons harboring high-expression IL1β alleles who are infected with H pyloricagA+ or vacA s1-type strains have 25-fold or 87-fold increases in risk, respectively, for gastric cancer compared to uninfected persons33. A recent genome-wide association study has identified new targets for studies of gastric carcinogenesis, demonstrating that TLR1 and FCGR2A loci are associated with H pylori sero-prevalence. However, the relationship between these genetic loci and disease was not determined35. Dietary factors have recently been shown to accelerate gastric carcinogenesis in rodent models of H pylori infection; specifically iron depletion accelerates the development of gastric dysplasia and cancer by promoting assembly and function of the H pylori cag PAI36.

Although H pylori infection is the strongest identified risk factor for gastric cancer, recent human trials have indicated that other residents of the gastric microbiota may influence malignant transformation. A clinical study examining the effects of anti-microbial therapy against H pylori reported that treatment was associated with a significant reduction in gastric cancer incidence rates 15 years after therapy. However, only 47% of treated persons remained free of H pylori at this time point37, leading to the tantalizing possibility that antibiotic therapy alters other microbial species that affect the development of gastric cancer. Another study evaluated the presence and frequency of bacteria-to-human somatic cell lateral gene transfer in human cancer specimens38. Of all malignancies examined, gastric adenocarcinomas harbored the second highest number of bacterial DNA integrations. However, the most frequent integrations were derived from Pseudomonas-like DNA, and not Helicobacter DNA38, supporting the premise that the non-H pylori gastric microbial ecosystem influences the development of cancer in the stomach.

The Human Gastric Microbiota

The human stomach is a relatively austere microbial niche, with colonization densities from 101 to 103 CFU/g39. Cutting-edge molecular techniques have provided insights into potential pathogenic roles of the gastric microbial community. H pylori-negative individuals have highly diverse gastric microbiota; their most abundant phyla are Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria1, 40. Common phylotypes present in H pylori-uninfected persons include Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Gemella41. Several studies have demonstrated that, among H pylori-colonized persons, H pylori accounts for >90% of all sequence reads41, so it greatly reduces the overall diversity of the gastric microbiota. The most abundant phyla in H pylori-colonized human stomachs are Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria42, 43. One study reported that H pylori infection of the stomach increased the relative abundance of Proteobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Acidobacteria while decreasing the relative abundance of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, compared to uninfected stomach42.

In contrast to studies comparing the composition of the gastric microbiota between H pylori-infected and -uninfected subjects, few studies have examined differences in microbial composition and outcomes from diseases such as gastric cancer39. One of the key steps in the histologic progression to intestinal-type gastric cancer is atrophy, which is accompanied by an increase in gastric pH due to loss of parietal cells4. Within the context of atrophic gastritis, non-molecular analyses have shown that, in the absence of H pylori, urease-producing members of the gastric microbiota, such as Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus capitis, and Micrococcus species can bloom to levels that cause false positive results in H pylori urea breath tests43. A terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism study found no significant differences between the microbiota of patients with and without gastric cancer44. Specifically, the microbiota of patients with gastric cancer was dominated by species of Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Veillonella, and Prevotella; among Streptococcus, S mitis and S parasanguinis predominated44. However, detailed molecular studies defining the composition of the gastric microbiota in well-characterized human populations, with and without gastric cancer, are clearly lacking39. Studies of rodent model systems will help identify important drivers and modifiers of diseases related to the microbiome.

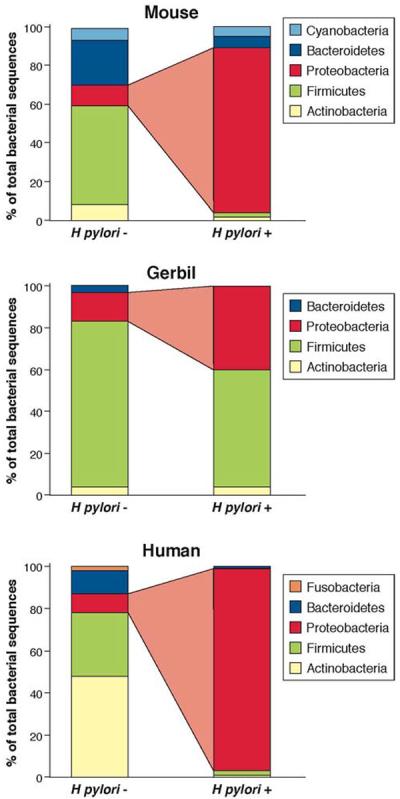

H pylori infection of Mongolian gerbils can lead to gastric adenocarcinoma, without the co-administration of carcinogens15, 45–47; gastric cancer in this model develops in the distal stomach, as in humans. Various H pylori wild-type and mutant strains colonize gerbils well48–50, allowing an examination of the role of virulence determinants on parameters of gastric injury. However, Mongolian gerbils are outbred, which increases the variability of responses to any stimulus. Studies of inbred mice with defined genotypes, as well as transgenic lines, would allow for more detailed analyses of host susceptibility. However, standard models of inbred mice are frequently limited by their uncontrolled microbial diversity. Gnotobiotic mice obviate this obstacle, but they are expensive and specialized facilities and expertise are required, limiting their widespread use. There are opportunities to conventionalize gnotobiotic mice available from commercial sources. Several studies have used molecular techniques to define the composition of gastric microbial communities in rodents with H pylori-induced gastric cancer (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Differences in the composition of human and rodent gastric microbiome, based on H pylori status.

There are substantial variations in the gastric microbiota of humans, mice, and gerbils. Nonetheless, the presence of H pylori alters the constituents of these ecosystems. This diagram shows the relative abundance of phyla, determined by high-throughput sequencing, in the stomach of humans, gerbils, and mice1,2,39,43. The risk of cancer increases with the presence of H pylori.

Rodent Models of H pylori-induced Gastric Cancer

Mongolian gerbils develop gastric cancer when colonized with certain strains of H pylori. Little is known about the composition of the gerbil gastric microbiota, but most commonly represented phyla include Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes39, 43. Similar to mice, the genus Lactobacillus dominates the gastric microbiome of uninfected gerbils39, 43.

Only one study used molecular techniques to comprehensively compare differences in the gerbil gastric microbiome before and after H pylori infection51. Using temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis and next-generation sequencing, Sun et al. observed reduced diversity of Lactobacillus following H pylori infection51. Another group utilized quantitative PCR to track the relative abundance of 15 species of microbes in gerbil stomach52. In uninfected gerbils, the most abundant genera were Lactobacillus and Enterococcus, followed by equivalent levels of Atopobium and Clostridium. In gerbils that were challenged and successfully infected with H pylori, the relative abundance of Clostridium coccoides increased, compared to gerbils not infected with H pylori. In gerbils that were challenged with H pylori but were not successfully colonized, the proportion of C coccoides, C leptum, and Bifidobacterium was reduced. Of interest, gerbils that were challenged with H pylori but unsuccessfully colonized represented the only group that harbored members of the Eubacterium cylindroides and Prevotella species52. The importance of differences in microbial composition and the development of gastric cancer has not been determined in this model.

Mice are another commonly used model of gastric carcinogenesis. Bacteria other than Helicobacter species have been found to induce gastritis in mice—Acinetobacter lowffi can induce gastric inflammation in the absence of H pylori53. Lactobacillus is the predominant genus in mouse stomach39, 43. However, despite identical genetic backgrounds of mice, their commercial source can affect the composition of the gastric microbiome. Rolig et al. reported that C57BL/6 mice from 2 independent vendors had different levels of Lactobacillus species and developed disparate inflammation and injury responses when challenged with H pylori54.

Infection of mice with H pylori can alter their gastric microbiota, which appears to depend on strain of mouse and duration of infection. In SPF Balb/c mice, H pylori infection reduced the number of Lactobacillus species and increased bacterial diversity55. However, studies of C57BL/6 mice have produced conflicting results. In one study, acute infection of C57BL/6 mice with H pylori did not cause significant shifts in the bacterial composition of the gastric microbiota56. However, administration of antibiotics to mice before H pylori infection altered the composition of the gastric microbiota and reduced the severity of gastric inflammation; these changes were reversed when the gastric microbiota from antibiotic-naïve mice was transferred to mice given antibiotics54.

Other studies with mice that are genetically susceptible to gastric cancer, such as hypergastrinemic INS-GAS mice, have shown that chronic interactions between H pylori and the gastric microbiota influence malignancy. Lofgren et al. demonstrated that germ-free INS-GAS mice mono-colonized with H pylori progress more slowly to gastric intraepithelial neoplasia than H pylori-infected specific pathogen-free (SPF) INS-GAS mice57. When the composition of the gastric microbiota was characterized in SPF INS-GAS mice, the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes accounted for >80% of the bacterial population. Infection with H pylori led to a bloom in the proportion of Firmicutes and decreased numbers of Bacteroidetes57. Of interest, there were no significant shifts in the colonic microbiota following infection with H pylori. Another study demonstrated that progression to gastric neoplasia was similar in SPF INS-GAS mice infected with H pylori and germ-free INS-GAS mice first infected with a restricted Altered Schaedler's Flora (ASF): [ASF 356 (contains Clostridium species), ASF 361 (contains Lactobacillus murinus), and ASF 519 (contains Bacteroides species)], and then challenged with H pylori58. These results indicate that these 3 bacterial constituents of ASF could cooperate with H pylori to increase the risk of gastric cancer.

Studies in mice have also suggested that extra-gastric constituents of the microbiota can influence gastric carcinogenesis. Colonization of C57BL/6 mice with the enterohepatic Helicobacter species H bilis or H muridarum before challenge with H pylori significantly reduced H pylori-induced injury of the stomach59, 60. In contrast, pre-colonization with H hepaticus increased H pylori-induced gastric damage60. The mechanism may involve reductions in the intensity of T helper 1-type cell responses against H pylori, which are mediated by T regulatory cells that have been sensitized to shared Helicobacter antigens59.

Despite the mechanistic information that has emerged from these studies, there are important caveats to consider when comparing the effects of the rodent microbiome on malignancy with cancers that develop in humans. The phyla present in H pylori-infected human stomachs are not the same as those that predominate in an H pylori-infected rodent gastric niche. The density and topography of H pylori colonization in rodent stomachs does not precisely reflect that of humans. For example, acute H pylori infection of mice tends to primarily affect the gastric corpus, compared to the antral-predominant colonization that is typical of human infections. Finally, the presence of a squamous forestomach in rodents can alter the composition of the rodent gastric microbiome, in contrast to what is present in the human stomach39. An exciting recent study in rhesus monkeys reported that, although Helicobacter species dominate the gastric community when present, infection with H pylori does not significantly alter the relative abundance of other taxa, except for H suis, which is reduced in proportion. These findings indicate that rhesus macaques represent another model for studying interactions between H pylori and constituents of the gastric microbiota61.

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the strongest known risk factor for Barrett's esophagus, a metaplasia associated with an increased risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Among white males, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is increasing rapidly62 and the decreasing incidences of H pylori carriage and gastric cancer in developed countries over the past century have been diametrically opposed by this rapidly increasing incidence of GERD and its sequelae4. Carriage of H pylori is associated with a significantly reduced risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma62.

How can the ability of H pylori strains to increase risk for distal gastric cancer be reconciled with reciprocal effects against GERD, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma? The location of inflammation within the gastric niche likely contributes to this dichotomy. By inhibiting parietal cell function and/or inducing the development of atrophic gastritis, inflammation in the acid-secreting gastric body induced by H pylori (especially in persons with polymorphisms that increase expression of IL1b) blunts the high-level acid secretion necessary for the development of GERD and its sequelae. Other potential mechanisms include changes in gastric hormone interactions and in T-cell populations induced by the loss of H pylori. Another possibility is that alterations in the gastric microbiome resulting from the loss of H pylori contribute to an increase in reflux-mediated esophageal adenocarcinoma. As noted above, there are distinct differences in the gastric microbial ecosystem among H pylori-infected and -uninfected subjects; it is plausible that the microbiota in one niche alter cancer risk at an adjacent site.

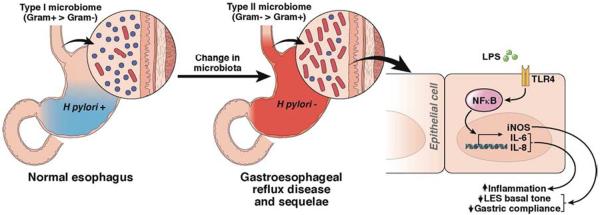

However, a recent single study demonstrated that the human distal esophagus has its own microbiota, which is perturbed during inflammation and metaplasia63. This study defined esophageal bacterial communities using a 16S rRNA gene survey and identified 2 distinct microbiome clusters, termed type I and type II63. The type I microbiome was dominated by Gram-positive bacteria, primarily Firmicutes. The type II microbiome was composed of a higher percentage of Gram-negative bacteria (53% vs 15% in type I), with the phyla Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Spirochaetes being the most highly represented63. The prevalence of Streptococcus was higher in type I vs type II microbiomes, while the prevalence of Gram-negative anaerobes or microaerophiles was increased in type II vs type I populations. Importantly, a type I microbiome was significantly associated with the presence of an endoscopically intact esophagus whereas a type II microbiome was strongly linked to esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus63.

Although cause and effect are difficult to establish conclusively in these types of studies, there are putative mechanisms by which different microbiome populations can affect esophageal disease (Figure 2). Gram-negative organisms, which predominate in reflux-associated type II esophageal microbiomes, produce specific immune-activating constituents such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which can activate innate immune responses that lead to disease64. LPS engages the innate immune system Toll-like receptor (TLR)4, leading to NFκB activation; levels of activated NFκB are increased in esophageal specimens from patients with reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma64. Increased activation of NFκB is associated with increased levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL1β, IL6, IL8, and TNFα64. Another effect of LPS-induced signaling is activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Activation of iNOS decreases the basal tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, which, over prolonged periods of time, increases the risk for reflux and its sequelae65. Further, LPS has been shown in rodents to delay gastric emptying, which increases the amount of gastric content refluxed into the esophagus66. Although further studies are needed, these results are exciting—the esophageal microbiome might be manipulated with antibiotics, probiotics, or inhibitors of specific host cell pathways (e.g. NFκB) to prevent disorders at this site.

Figure 2. Potential effects of the gastroesophageal microbiome on complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The healthy esophagus has a type I microbiome, dominated by Gram-positive bacteria. In contrast, patients with GERD or Barrett's esophagus have a different population of esophageal microbes (a type II microbiome), comprised primarily of Gram-negative bacteria. There are several mechanisms through which these different microbial populations might affect gastroesophageal reflux. Gram-negative organisms produce immune-activating molecules such as LPS, which induces innate immune responses that lead to disease64. LPS binds to and activates TLR4, leading to activation of NFκB; levels of activated NFκB are increased in esophageal samples from patients with reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma64. Increased activation of NFκB leads to increased production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL1β, IL6, IL8, and TNFα64. In this manner, the type II esophageal microbiome contributes to esophagitis. LPS signaling also increases levels of iNOS, which reduces the basal tone of the lower esophageal sphincter. Over prolonged periods, this increases risk for reflux and its sequelae65. LPS has also been shown to delay gastric emptying in rodents, which increases the amount of gastric contents refluxed into the esophagus66. Production of iNOS can therefore lower the threshold for reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus.

Gastric and Esophageal Cancer Summary

The explosion of data enumerating and cataloguing non-H pylori members of the gastric microbial ecosystem, combined with animal studies highlighting the importance of collaboration between H pylori and the gastric microbiome, has challenged dogma about the pathogenesis of gastric cancer. In contrast to a model that focused on interactions between different strains of H pylori and genetic features of the host, researchers must now consider an alternative model, in which early interactions between H pylori and human tissues alter the structure of the gastric microbiome, by promoting gastric atrophy. Microbial blooms that develop in response to less-acidic conditions lead to new microbiome populations that might promote carcinogenesis.

Although less information is available about the effects of the microbiome on esophageal cancer, it is plausible that alterations of the gastric microbiome contribute to the increased incidence of esophageal adenocarcinomas—particularly those that arise within the gastroesophageal junction. However, there is an endogenous esophageal microbiome that differs between persons with healthy esophageal mucosa and those with Barrett's esophagus. Delineation of the fundamental relationships between members of the gastric and esophageal microbial communities is an important step in developing strategies to deliver beneficial effector species to a desired location, or engineering microbial species that can colonize these sites.

Colon Cancer

Colon cancer is an age-related disease; its incidence is predicted to increase by 52% in the next 17 years.67 A culmination of multiple genetic and epigenetic events contributes to pathogenesis of colon cancer. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is initiated by mutations in tumor suppressor genes (APC, CTNNB1, p53) and oncogenes (KRAS), which transform healthy mucosa to adenoma and cancer.68, 69 Although mutations in these genes have clear roles in development of CRC, the events that lead to acquisition of these mutations and epigenetic changes are less clear. Arguably, understanding these earlier events offers a greater possibility for preventing CRC. Recent studies have identified microbial and environmental factors, such as diet and lifestyle, that can promote colon cancer.70, 71 Advances in sequencing and computational technology have facilitated determination of the role of the intestinal microbiota in CRC. We discuss human studies that have linked bacteria with colon cancer and findings from animal models.

The Microbiome in Patients with Polyps or Colon Cancer

In the colon, mammalian cells coexist with microorganisms, comprising bacteria, Archaea, viruses, and unicellular eukaryotes. Bacteria alone constitute about 90% of the total cell population in the colon.72 The colonic microbiota is primarily composed of Gram-negative Bacteroidetes and Gram-positive Firmicutes whereas Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria form minor components.73 Intestinal microbes help maintain homeostasis, contributing to immune development, preventing pathogen colonization, processing drug metabolites, and releasing key nutrients and energy from the diet. This complex community develops within the first 2 years after birth and remains stable throughout the lifetime, but varies among individuals.74, 75 The intestinal microbiota also has spatial variation, with differences between lumen- and mucosa-associated bacteria.76

In spite of the beneficial effects of the microbiome, a small percentage of people develop colon cancer. The incidence of colon cancer is approximately 12-fold higher than cancer in the small intestine77, which harbors approximately 1010 fewer bacteria than the colon. Chronic colon inflammation, which may be caused by alterations in the intestinal microbiota, promotes colon carcinogenesis; cancers associated with inflammatory bowel diseases are prime examples of this concept.78 Initially colon cancer was associated with single pathogenic bacterial species, such as Streptococcus gallolyticus, H pylori, or adherent invasive E coli.37, 79, 80 However, studies from the last decade support the concept that multiple bacterial species contribute to CRC (Table 1). Disturbances in the composition, distribution, or metabolism of the colon microbiota might shift the homeostatic environment of the colon towards inflammation, dysplasia, and cancer.

Table 1.

Microbiota Changes Associated with Colon Cancer

| Patients | Changes in the Microbiota | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 29 patients with colon adenomas, 31 with CRC, 34 patients with symptoms but normal colonoscopy results, 31 asymptomatic patients (controls) | Increased presence of intracellular E coli in patients with adenoma and CRC | 141 |

| Biopsies from 21 patients with adenomas and 23 without (controls) | Patients with adenomas had increased proportions of Proteobacteria, Faecalibacterium, and Dorea and decreased levels of Coprococcus and Bacteroides | 81 |

| Fecal samples from 60 patients with CRC and 119 healthy subjects (controls) | Pyrosequencing on a small subset of samples indicated microbiota differences in CRC patients vs controls. Higher Bacteroides/Prevetolla in patients with CRC, determined by quantitative PCR. | 82 |

| 6 patients with colon adenocarcinomas; matched tumor and healthy tissues (5–10 cm from tumor) biopsies | Microbial communities differed between tumor and healthy tissues. Tumors had more Bacteroidetes and Coriobacteridae, and less Firmicutes and Enterobacteriaceae | 90 |

| Fecal samples from 46 healthy individuals and 46 patients with CRC | Patients with CRC had higher proportions of pathogenic bacteria including Enterococcus, Escherichia/Shigella, B fragilis, and Klebsiella and reduced proportions of butyrate-producing bacteria, including Roseburia and members of family Lachnospiraceae | 123 |

| 46 patients with CRC: 21 stool samples, 32 rectal swab samples, 27 tumors tissues and matched normal surrounding tissues (2–5 cm and 10–20 cm away from tumor) 22 stool and 34 rectal swab samples from healthy volunteers (controls) |

Microbiota were similar between matched samples from cancerous and non-cancerous tissues; cancer tissues had lower bacterial diversity. Microbiota differed between cancerous tissue and stool with over-representation of 6 and under-representation of 2 bacterial families in cancerous tissue compared to stool. Stool and mucosal-associated microbiota differed between CRC patients and controls. | 76 |

| 88 CRC patients and matched normal tissues | Increased Fusobacterium and Streptococcaceae in tumor tissues | 86 |

| CRC and non-tumor colon tissues from 95 patients | Increased F nucleatum in tumor tissues | 85 |

| Stool samples from 10 patients with colon cancer and 11 healthy individuals (controls) | No significant differences in microbial composition and diversity between patients and controls; relatively low levels of Bacteroides and Prevotella and higher percentages of Akkermansia muciniphila in patients | 84 |

| Fecal samples 344 patients with advanced CRC and 344 healthy individuals (controls) | Increased abundance of Enterococcus and Streptococcus spp. in the patients and increased prevalence of butyrate producing bacterial groups (Roseburia, Clostridium) in controls. | 89 |

In efforts to understand how the microbiome participates in CRC development, studies have been performed on either mucosa-associated bacteria or the stool microbiome in patients with CRC. Bacteria that adhere to the mucosa in patients with adenomas have increased diversity, compared to those of patients without adenomas.81 Studies of the stool microbiome have found an increase in Bacteroides species72, 82, 83, a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria72, 83, 84, and an increase in potentially pathogenic bacteria such as Fusobacterium species.83, 85, 86, 87 The finding of increased Bacteroides is interesting, because toxin production could contribute to inflammation and cancer.88 In studies of mucosa-associated bacteria that compared cancer and surrounding tissues, cancer tissues had overrepresentation of Coriobacteridae.89, 90 It is likely that local changes in the microbiome of cancer tissues are related to changes in the availability of nutrients and other conditions created by the cancer cells themselves.84, 91 Studies of the composition of the stool may someday be helpful, especially if paired with PCR-based studies of host DNA mutations in oncogenes, to screen patients for CRC or adenomas. Ideally, prospective studies would investigate whether changes in the microbiome precede the development of adenomas or cancer.

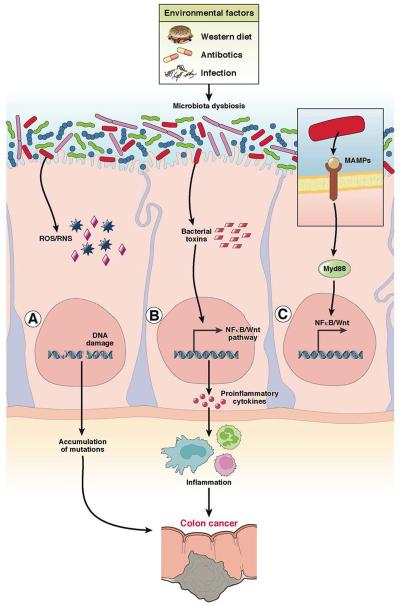

Diet, antibiotics, and stress are extrinsic and intrinsic factors that contribute to microbiome dysbiosis.73, 74 High-throughput 16S sequencing studies have led to models of mechanisms by which bacteria could contribute to CRC development. In one model, called the driver-passenger model, certain populations of bacteria (drivers) initiate CRC by damaging DNA in the intestinal epithelium.92 Initiation of tumorigenesis alters the intestinal environment, resulting in overgrowth of opportunistic bacteria (passengers), and possible depletion of driver bacteria.92 This model contrasts the α bug model, wherein bacteria with virulent properties (α bugs) initiate tumorigenesis and create helper bugs by modulating the gut microbiota. Together, these bugs take over commensal bacterial populations93 (see models in Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bacteria associated colon cancer.

In a homeostatic colonic environment, bacteria are separated from the colonic epithelial layer by mucus, anti-microbial peptides, and secreted immunoglobulin A (IgA). Certain environmental factors induce microbial dysbiosis, leading to interactions between microbes and intestinal epithelial cells. Dysbiotic microbiota induces colon carcinogenesis by (A) releasing reactive oxygen species or reactive nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) and causing DNA damage133, 134, 135, 136 (B) releasing toxins that directly damage DNA or induce cell proliferation genes88 (C) generating MAMPs, which activate the innate immune response, recruit immune cells, and induce inflammation87.

Viruses

Various studies, over the past decades, have demonstrated roles for viruses in CRC. John Cunningham (JC) virus, human papilloma viruses (HPV), and BK virus are some common viruses associated with CRC. However not all strains of every virus have equal oncogenic potential. Although studies have correlated viral DNA with CRC, it is not clear if viruses are sufficient for carcinogenesis. Several studies have reported the presence of JC virus in CRC patients.94, 95 T-antigen, an oncogenic early protein encoded by JC virus, interacts with β-catenin to activate genes that regulate proliferation and transformation.96 In vitro and patient-based studies have correlated the presence of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) with cancer progression and CRC.97, 98 In one study, HCMV was detected in 42% of cancer tissues and 5.6% of matched non-cancerous tissue. However, increased local inflammation might activate CMV. Also, in patients with CRC, disease severity correlated with HPV infection. HPV DNA was more commonly detected in early-stage than late-stage cancers. However, no association between viruses and CRC has been reported in other studies.99

It is not clear if particular viruses are not detected in cancer patients because the viruses have similar functions to driver bacteria—they are involved in only early stages of cancer development, and are not required for tumor progression. Compared to the quantity of studies on the microbiota, few studies have focused on the virome as a factor in onset or progression of CRC. It is likely that a longer list of potentially pathogenic enteric viruses will eventually be associated with CRC.

Diet and Microbe Metabolites

Diet is an important environmental factor associated with CRC. Epidemiology studies have indicated that the Western diet, rich in meat and fat, is a risk factor for CRC, whereas diets rich in fiber protect against CRC.100, 101 Colonic bacteria have many genes that regulate metabolism; they metabolize dietary components that pass through the small intestine undigested. A fiber-rich diet results in saccharolytic fermentation of carbohydrates that leads to production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, butyrate, and propionate.102 Butyrate has anti-tumorigenic properties and is associated with decreased incidence of CRC.103, 104 Bacterial species such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii from Clostridium cluster IV and Eubacterium/Roseburia species from cluster XIVa are some of the major butyrate producers found in human colon.105

Proteolytic fermentation during consumption of diets rich in meat prompts generation of inflammatory and carcinogenic metabolites—notably phenols, ammonia, branched-chain SCFAs, and other nitrogen-rich metabolites.106 Diets high in protein and fat content also promote growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria, such as Desulfovibrio vulgaris, and generate excess genotoxic hydrogen sulfide. High-fat diets generate bile acids, which are excellent substrates for bacteria that express 7α-dehydroxylating enzymes. These bacteria convert primary bile acids to potentially carcinogenic secondary bile acids such as lithocholic acid and deoxycholic acid.107

Recent studies have focused on deciphering the link between diet, the microbiota, and CRC.89, 108 These studies reported lower levels of health-promoting butyrate-producing bacteria and increased metabolites (SCFA and butyrate) in meat-eating African-Americans (who are at high risk for CRC), and patients with low-fiber diets and advanced colorectal adenoma. Secondary bile acids and microbial genes that control their generation were increased in fecal samples from meat-eating African-Americans, compared to native Africans with high-fiber diets.108 The gut microbiota also differed between subjects and controls in these studies. These differences in the microbiota might be attributed to differences in genetic and environmental factors between Africans and African Americans. However, they indicate the importance of using integrated approaches, including metabolomics analyses, in studies of the microbiome, to fully assess how dysbiotic microbiota contribute to cancer development.

Host Immune Recognition of Bacteria

The innate immune component of the host immune system recognizes microbial molecules such as LPS, flagellin, peptidoglycans, and other microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are a well-studied component of the innate immune system; these include Nod-like receptors (NLRs), TLRs, and retinoic acid inducible gene I-like receptors.109, 110 Activation of PRRs regulates proliferation, barrier function, and inflammatory pathways in multiple cell types.111, 112 Several studies have associated colon neoplasias with genetic polymorphisms in, or changes in expression of, genes that control PRR pathways. For example, CRC tissues have increased levels of TLR2, 4, 7, 8, and 9 mRNAs, compared to healthy surrounding tissue (for review see113). A number of studies have investigated expression patterns of TLRs in cancer tissues, compared to healthy tissues and adenomas. Cancer tissues had increased expression of epithelial TLR4, compared to adenomas and healthy mucosa.114 In a meta-analysis of cDNA microarray studies, expression of genes in the NLR signaling pathways was significantly altered in CRC tissues, compared with non-tumor tissues.115

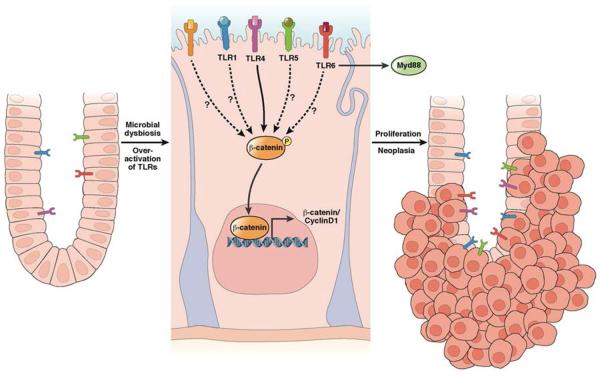

Although human studies have linked variants in bacterial recognition genes with CRC, there is no clear mechanism by which they alter colon cancer susceptibility. Animal studies fill this knowledge gap. Most of these studies have involved mice with disruptions of PRR pathway genes. From these studies it is evident that innate immune pathways mediate chronic inflammation in the presence of bacterial infection or chemical epithelial injury. Chronic inflammation is a major risk factor for CRC and results in immune cell recruitment and release of inflammatory mediators such as TNFα, IL6, IL1b and other cytokines.116 These inflammatory mediators activate NF-κB to initiate a cascade of events that culminate in colon carcinogenesis (Figure 4). In mice, TLR4 deletion protects against CRC, whereas overexpression of TLR4 results in β-catenin activation and increased colitis-associated cancer development following administration of azoxymethane (AOM, a mutagen) and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS, induces colitis).114, 117, 118

Figure 4. Bacteria activate TLR signaling to promote colon carcinogenesis.

Microbial dysbiosis or mutations can activate TLR signaling, leading to phosphorylation of β–catenin, cell proliferation, and tumor progression114. It is not clear whether other TLRs promote colon carcinogenesis via activation of β-catenin.

However, TLR2−/− mice develop more tumors than wild-type mice.119 Loss of Myd88, an adapter that transduces most TLR signals, reduces tumor development in mice following administration of only AOM, but increases colitis-associated cancer in mice given AOM and DSS.120 This finding has been attributed to loss of IL-18 production by myeloid cells. APCmin/+Myd88−/− mice develop fewer colon tumors than APCmin/+ mice, indicating that bacterial signaling contributes to tumorigenesis in the context of APC mutations.121 A subsequent study found that MyD88-dependent activation of ERK stabilizes β-catenin; in this way, the absence of MyD88 protects against APC-dependent tumors.122 Thus depending on the model used, MyD88 deficiency either protects or increases tumorigenesis.

The different outcomes of mice lacking MyD88 likely reflect nuances of the animal models and the relative dependence on inflammation and bacterial signaling. Moreover, because these models often involve total knockouts, it is difficult to know which cell type in the intestine (epithelial, myeloid, or other) responds to bacterial signals to contribute to carcinogenesis. Similar to humans, ApcF/wt mice with a Cdx2-Cre transgene (also known as CPC-APC mice) develop tumors in the distal colon, due to allelic loss of Apc. In these mice, expression of IL23 and IL17 are upregulated in tumor tissues. Levels of IL23 and IL17 and tumor growth decrease after antibiotic treatment and deletion of Myd88.123 These observations support the notion that bacterial activation of PRRs results in inflammation, immune activation, or proliferation that modifies the growth of colonic tumors.

Animal Models and Luminal Bacteria

Genetically engineered models of CRC, raised under germ-free conditions, are invaluable for studying links between colon neoplasia and gut microbes. APCmin/+ mice are commonly used to study the role of environmental factors, such as diet and intestinal bacteria, on CRC. APCmin/+ mice carry a heterozygous mutation in the APC gene and develop spontaneous tumors, mostly in the small intestine.124 This is in contrast to humans, in which APC mutations cause colonic tumors. Germ-free APCmin/+ mice develop fewer small intestinal and colon polyps than their conventionally raised counterparts.125

Mice with disruptions in specific genes (Il10−/−, Tcrb/p53−/−, Gpx1/Gpx2−/−, and Tgfb1/Rag2−/−) develop fewer tumors under GF than conventional conditions, as do mice exposed to AOM and DSS.126 Studies of mice that develop colitis that promotes neoplasia support the involvement of microbes in tumor development. Infection of Rag2−/− or Il10−/− mice with H hepaticus leads to colitis-associated cancer.127, 128 However mono-association with Bacteroides vulgatus reduced colorectal tumorigenesis in Il10−/− mice, compared to conventional Il10−/− mice.129 Therefore, in the same genetic background, different microbial species can have different effects on colon carcinogenesis.

The incidence and severity of colitis-associated cancer are reduced in mice given antibiotics.130, 131 Moreover co-housing and microbiota transplant experiments have shown that development of colitis-associated cancer can be maternally transmitted, through the microbiota in genetically susceptible mice.38, 130Nod2−/− mice have an altered microbiota, compared to wild-type mice and develop more tumors after AOM-DSS treatment.130 The susceptibility to tumors in Nod2−/− appears to track with its microbiota since it can be diminished by treatment of mice with antibiotics or stool transplants from wild-type mice; conversely, wild-type mice can have increased numbers of tumors when colonized with dysbiotic Nod2−/− microbiota. These data suggest that manipulation of the microbiota can be used to prevent development of CRC if we could identify the principal agents driving the neoplasia risk.

Infectious Agents That Promote Colonic Neoplasia

Studies in animal models have shown that bacteria can promote tumorigenesis by releasing genotoxic compounds. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis secretes a 20 kDa zinc-dependent metalloprotease, B fragilis toxin, which stimulates cleavage of E-cadherin and activates β-catenin. Infection of APCmin/+ mice with Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis increases tumorigenesis in the large intestine by activating STAT3, which leads to production of IL17 by T helper 17 cells; by contrast, uninfected APCmin/+ mice usually develop only small intestinal tumors.88 Furthermore, data from epidemiologic studies indicate a higher prevalence of Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis infection among patients with CRC.

Fusobacterium has also been consistently associated with CRC.85, 86 Greater proportions of this bacterium have been detected in colorectal tumor and adenoma samples compared with normal tissue. In APCmin/+ mice, Fusobacterium was found to contribute to colorectal tumorigenesis by attracting myeloid immune cells to adenomas.87 Fusobacterium adhesin A (FadA) is a surface molecule expressed by Fusobacterium. In addition to helping Fusobacterium attach to and invade cancer cells, FadA was recently shown to modulate E-cadherin signaling to β-catenin.132

Some bacterial infections cause generation of reactive oxygen and nitric oxide species that damage DNA to transform cells. Arthur et al. demonstrated that an E coli strain carrying a polyketide synthase pathogenicity island that encodes colibactin increases the invasiveness of adenocarcinomas that develop in Il10−/− mice following administration of AOM.79 Colibactin has been shown to induce genetic instability by causing DNA double strand breaks.133 Deletion of the pathogenicity island reduced the rate of invasive tumors but did not change the level of inflammation caused by this E coli strain. These data suggest that it is the synthesis by the bacteria of colibactin, rather than only the degree of inflammation, that increased the neoplasia risk. They also detected this particular strain in approximately 65% of CRC tissue specimens, compared with 20% of tissue from healthy individuals. Enterococcus faecalis has been shown to produce extracellular superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, which damage DNA in colonic epithelial cells.134, 135, 136 On the other hand, bacteria can express superoxide dismutase to decrease reactive oxygen damage.137 These latter species may be beneficial for patients at risk for CRC.

Probiotics in Colon Cancer

A number of in vitro and animal studies provide evidence that consuming probiotics suppresses CRC. These studies have also proposed multiple pathways by which probiotics could inhibit colon cancer—notably by influencing innate immune pathways and apoptosis, reducing oxidative stress, and modulating intestinal bacteria and their metabolism.138 Despite these laboratory-based studies, only a limited number of clinical trials have evaluated the potential of probiotics in suppressing CRC. Lactobacillus species are the most commonly used probiotics in clinical trials. Lactobacillus johnsonii reduced the concentration of Enterobacters and modulated intestinal immune response in CRC patients, whereas Bifidobacterium longum did not have any effect.139 In another study, Lactobacillus casei suppressed colorectal tumor growth in patients, after 2–4 years of treatment. However these clinical trials are limited by the small number of subjects and their short duration.140

Colon Cancer Summary

Development of CRC involves a combination of inherited and acquired mutations in colonic epithelial cells, along with environmental factors including the intestinal microbiota. It is not clear whether there are specific microbes that are particularly pathogenic and directly cause colorectal carcinogenesis, or the process requires specific interactions between host tissues and microbes; a variety of mechanisms are likely to be involved. It would be a challenge to identify a single type of microbe, among myriad of microbes present in the human colon, that cause cancer. Even identifying a microbial signature associated with CRC is a challenge, because the intestinal microbiota change during disease development and progression. High-throughput sequencing technologies have facilitated whole-microbiome and metagenome studies, but the absence of proper controls poses certain limitations. Moreover, it is difficult to control for genetic variation among individuals—the contribution of the microbiota to CRC is influenced by host genotype. Blood or stool samples can be screened to monitor microbes and their metabolites, and profiles of microbial metabolites may correlate with CRC development. This could be a valuable screening tool as bacterial species share an exceptional number of metabolic genes. However an in-depth profiling of bacterial metabolites is needed to identify microbial metabolites that could affect CRC development. Antibiotics and probiotics might affect CRC development, by manipulating the composition and function of the microbiota. A carefully designed standardized approach, with proper dietary and other controls, as well as follow-up markers, is needed to evaluate cancer treatment or prevention strategies.

Future Directions

Detailed analyses of the GI microbiome have associated diseases such as cancer with specific patterns of microbes. Researchers now need to investigate causes vs effects of these relationships. This could be accomplished in prospective trials in which specific microbes are altered or eliminated, and effects on disease incidence or progression are assessed. Animals with human microbiota can also be used to study the effects of different microbial populations on disease development. These studies are important, as manipulation of microbial communities has vast therapeutic potential. Microbes engineered to express specific genes or produce specific metabolites might be delivered to particular niches within the GI tract to treat or prevent disease. The GI microbiome also has the capacity to alter the metabolism of chemotherapeutic agents. Certain drugs, doses, or regimens might be selected for patients based on the composition of their microbiome, or the microbiota might be monitored to evaluate response to therapy. The microbiome is an exciting new frontier for the prevention and management of malignancies of the GI tract.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants CA 137869, Bankhead Coley XX, and CCFA Senior Investigator Award (to MTA), and CA 77955, DK 58587, and CA 116087 (to RMP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions:

Maria T. Abreu: analysis and interpretation of previous data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content

Richard Peek: analysis and interpretation of previous data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content

Disclosures/Conflict of interest: The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Cho I, Blaser MJ. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nature Rev Genetics. 2012;13:260–70. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plottel CS, Blaser MJ. Microbiome and malignancy. Cell Host & Microbe. 2011;10:324–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:607–15. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polk DB, Peek RM., Jr. Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:403–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wroblewski LE, Peek RM. H. pylori in gastric carcinogenesis: mechanisms. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2013;42:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odenbreit S, Puls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer W, Puls J, Buhrdorf R, Gebert B, Odenbreit S, Haas R. Systematic mutagenesis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island: essential genes for CagA translocation in host cells and induction of interleukin-8. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:1337–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwok T, Zabler D, Urman S, Rohde M, Hartig R, Wessler S, Misselwitz R, Berger J, Sewald N, Konig W, Backert S. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature. 2007;449:862–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer CL, Gaddy JA, Loh JT, Johnson EM, Hill S, Hennig EE, McClain MS, McDonald WH, Cover TL. Helicobacter pylori exploits a unique repertoire of type IV secretion system components for pilus assembly at the bacteria-host cell interface. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7:e1002237. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, Cover TL, Peek RM, Chyou PH, Stemmermann GN, Nomura A. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller D, Tegtmeyer N, Brandt S, Yamaoka Y, De Poire E, Sgouras D, Wessler S, Torres J, Smolka A, Backert S. c-Src and c-Abl kinases control hierarchic phosphorylation and function of the CagA effector protein in Western and East Asian Helicobacter pylori strains. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122:1553–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI61143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Muto S, Sugiyama T, Azuma T, Asaka M, Hatakeyama M. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science. 2002;295:683–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1067147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saadat I, Higashi H, Obuse C, Umeda M, Murata-Kamiya N, Saito Y, Lu H, Ohnishi N, Azuma T, Suzuki A, Ohno S, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA targets PAR1/MARK kinase to disrupt epithelial cell polarity. Nature. 2007;447:330–3. doi: 10.1038/nature05765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amieva MR, Vogelmann R, Covacci A, Tompkins LS, Nelson WJ, Falkow S. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science. 2003;300:1430–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1081919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franco AT, Israel DA, Washington MK, Krishna U, Fox JG, Rogers AB, Neish AS, Collier-Hyams L, Perez-Perez GI, Hatakeyama M, Whitehead R, Gaus K, O'Brien DP, Romero-Gallo J, Peek RM., Jr. Activation of ß-catenin by carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10646–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murata-Kamiya N, Kurashima Y, Teishikata Y, Yamahashi Y, Saito Y, Higashi H, Aburatani H, Akiyama T, Peek RM, Jr., Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA interacts with E-cadherin and deregulates the beta-catenin signal that promotes intestinal transdifferentiation in gastric epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:4617–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagy TA, Wroblewski LE, Wang D, Piazuelo MB, Delgado A, Romero-Gallo J, Noto J, Israel DA, Ogden SR, Correa P, Cover TL, Peek RM., Jr. ß-Catenin and p120 mediate PPARdelta-dependent proliferation induced by Helicobacter pylori in human and rodent epithelia. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:553–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt S, Kwok T, Hartig R, Konig W, Backert S. NF-kB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9300–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Romero-Gallo J, Barry DP, Hoge S, de Sablet T, Delgado AG, Wroblewski LE, Piazuelo MB, Yan F, Israel DA, Casero RA, Jr., Correa P, Gobert AP, Polk DB, Peek RM, Jr., Wilson KT. Spermine oxidase mediates the gastric cancer risk associated with Helicobacter pylori CagA. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1696–708. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cover TL, Blanke SR. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:320–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atherton JC, Cao P, Peek RM, Jr., Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ, Cover TL. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17771–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhead JL, Letley DP, Mohammadi M, Hussein N, Mohagheghi MA, Eshagh Hosseini M, Atherton JC. A new Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin determinant, the intermediate region, is associated with gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:926–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Backert S, Tegtmeyer N. The versatility of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin VacA in signal transduction and molecular crosstalk. Toxins. 2010;2:69–92. doi: 10.3390/toxins2010069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, Sato T, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, van den Brink S, Korving J, Abo A, Peters PJ, Wright N, Poulsom R, Clevers H. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uehara T, Ma D, Yao Y, Lynch JP, Morales K, Ziober A, Feldman M, Ota H, Sepulveda AR. H. pylori infection is associated with DNA damage of Lgr5-positive epithelial stem cells in the stomach of patients with gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:140–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guruge JL, Falk PG, Lorenz RG, Dans M, Wirth HP, Blaser MJ, Berg DE, Gordon JI. Epithelial attachment alters the outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syder AJ, Guruge JL, Li Q, Hu Y, Oleksiewicz CM, Lorenz RG, Karam SM, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Helicobacter pylori attaches to NeuAc alpha 2,3Gal beta 1,4 glycoconjugates produced in the stomach of transgenic mice lacking parietal cells. Mol Cell. 1999;3:263–74. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syder AJ, Oh JD, Guruge JL, O'Donnell D, Karlsson M, Mills JC, Bjorkholm BM, Gordon JI. The impact of parietal cells on Helicobacter pylori tropism and host pathology: an analysis using gnotobiotic normal and transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3467–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230380100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh JD, Kling-Backhed H, Giannakis M, Xu J, Fulton RS, Fulton LA, Cordum HS, Wang C, Elliott G, Edwards J, Mardis ER, Engstrand LG, Gordon JI. The complete genome sequence of a chronic atrophic gastritis Helicobacter pylori strain: evolution during disease progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9999–10004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603784103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsugawa H, Suzuki H, Saya H, Hatakeyama M, Hirayama T, Hirata K, Nagano O, Matsuzaki J, Hibi T. Reactive oxygen species-induced autophagic degradation of Helicobacter pylori CagA is specifically suppressed in cancer stem-like cells. Cell Host & Microbe. 2012;12:764–77. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noach LA, Bosma NB, Jansen J, Hoek FJ, van Deventer SJ, Tytgat GN. Mucosal tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-8 production in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:425–9. doi: 10.3109/00365529409096833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N, Lanyon G, Martin M, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Rabkin CS. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398–402. doi: 10.1038/35006081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Figueiredo C, Machado JC, Pharoah P, Seruca R, Sousa S, Carvalho R, Capelinha AF, Quint W, Caldas C, van Doorn LJ, Carneiro F, Sobrinho-Simoes M. Helicobacter pylori and interleukin 1 genotyping: an opportunity to identify high-risk individuals for gastric carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1680–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.22.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garza-Gonzalez E, Bosques-Padilla FJ, El-Omar E, Hold G, Tijerina-Menchaca R, Maldonado-Garza HJ, Perez-Perez GI. Role of the polymorphic IL-1B, IL-1RN, and TNF-a genes in distal gastric cancer in Mexico. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:237–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayerle J, den Hoed CM, Schurmann C, Stolk L, Homuth G, Peters MJ, Capelle LG, Zimmermann K, Rivadeneira F, Gruska S, Volzke H, de Vries AC, Volker U, Teumer A, van Meurs JB, Steinmetz I, Nauck M, Ernst F, Weiss FU, Hofman A, Zenker M, Kroemer HK, Prokisch H, Uitterlinden AG, Lerch MM, Kuipers EJ. Identification of genetic loci associated with Helicobacter pylori serologic status. JAMA. 2013;309:1912–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noto JM, Gaddy JA, Lee JY, Piazuelo MB, Friedman DB, Colvin DC, Romero-Gallo J, Suarez G, Loh J, Slaughter JC, Tan S, Morgan DR, Wilson KT, Bravo LE, Correa P, Cover TL, Amieva MR, Peek RM., Jr Iron deficiency accelerates Helicobacter pylori-induced carcinogenesis in rodents and humans. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123:479–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI64373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma JL, Zhang L, Brown LM, Li JY, Shen L, Pan KF, Liu WD, Hu Y, Han ZX, Crystal-Mansour S, Pee D, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr, You WC, Gail MH. Fifteen-year effects of Helicobacter pylori, garlic, and vitamin treatments on gastric cancer incidence and mortality. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2012;104:488–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley DR, Sieber KB, Robinson KM, White JR, Ganesan A, Nourbakhsh S, Dunning Hotopp JC. Bacteria-human somatic cell lateral gene transfer is enriched in cancer samples. PLoS Computational Biology. 2013;9:e1003107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fox J, Sheh A. The role of the gastrointestinal microbiome in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:30–55. doi: 10.4161/gmic.26205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bik EM, Eckburg PB, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Purdom EA, Francois F, Perez-Perez G, Blaser MJ, Relman DA. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:732–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Backhed F, Nyren P, Engstrand L. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maldonado-Contreras A, Goldfarb KC, Godoy-Vitorino F, Karaoz U, Contreras M, Blaser MJ, Brodie EL, Dominguez-Bello MG. Structure of the human gastric bacterial community in relation to Helicobacter pylori status. ISME. 2011;5:574–9. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang I, Nell S, Suerbaum S. Survival in hostile territory: the microbiota of the stomach. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2013;37:736–61. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dicksved J, Lindberg M, Rosenquist M, Enroth H, Jansson JK, Engstrand L. Molecular characterization of the stomach microbiota in patients with gastric cancer and in controls. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58:509–16. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:642–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Honda S, Fujioka T, Tokieda M, Satoh R, Nishizono A, Nasu M. Development of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinoma in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4255–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogura K, Maeda S, Nakao M, Watanabe T, Tada M, Kyutoku T, Yoshida H, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori responsible for gastric diseases in Mongolian gerbil. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1601–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peek RM, Wirth HP, Moss SF, Yang M, Abdalla AM, Tham KT, Zhang T, Tang LH, Modlin IM, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori alters gastric epithelial cell cycle events and gastrin secretion in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:48–59. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Israel DA, Salama N, Arnold CN, Moss SF, Ando T, Wirth HP, Tham KT, Camorlinga M, Blaser MJ, Falkow S, Peek RM., Jr Helicobacter pylori strain-specific differences in genetic content, identified by microarray, influence host inflammatory responses. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107:611–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Franco AT, Johnston E, Krishna U, Yamaoka Y, Israel DA, Nagy TA, Wroblewski LE, Piazuelo MB, Correa P, Peek RM., Jr Regulation of gastric carcinogenesis by Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:379–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun YQ, Monstein HJ, Nilsson LE, Petersson F, Borch K. Profiling and identification of eubacteria in the stomach of Mongolian gerbils with and without Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2003;8:149–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osaki T, Matsuki T, Asahara T, Zaman C, Hanawa T, Yonezawa H, Kurata S, Woo TD, Nomoto K, Kamiya S. Comparative analysis of gastric bacterial microbiota in Mongolian gerbils after long-term infection with Helicobacter pylori. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2012;53:12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zavros Y, Rieder G, Ferguson A, Merchant JL. Gastritis and hypergastrinemia due to Acinetobacter lwoffii in mice. Infection and Immunity. 2002;70:2630–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2630-2639.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rolig AS, Cech C, Ahler E, Carter JE, Ottemann KM. The degree of Helicobacter pylori-triggered inflammation is manipulated by preinfection host microbiota. Infection and Immunity. 2013;81:1382–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00044-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aebischer T, Fischer A, Walduck A, Schlotelburg C, Lindig M, Schreiber S, Meyer TF, Bereswill S, Gobel UB. Vaccination prevents Helicobacter pylori-induced alterations of the gastric flora in mice. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2006;46:221–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan MP, Kaparakis M, Galic M, Pedersen J, Pearse M, Wijburg OL, Janssen PH, Strugnell RA. Chronic Helicobacter pylori infection does not significantly alter the microbiota of the murine stomach. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73:1010–3. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01675-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lofgren JL, Whary MT, Ge Z, Muthupalani S, Taylor NS, Mobley M, Potter A, Varro A, Eibach D, Suerbaum S, Wang TC, Fox JG. Lack of commensal flora in Helicobacter pylori-infected INS-GAS mice reduces gastritis and delays intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:210–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lertpiriyapong K, Whary MT, Muthupalani S, Lofgren JL, Gamazon ER, Feng Y, Ge Z, Wang TC, Fox JG. Gastric colonisation with a restricted commensal microbiota replicates the promotion of neoplastic lesions by diverse intestinal microbiota in the Helicobacter pylori INS-GAS mouse model of gastric carcinogenesis. Gut. 2013 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305178. Epub June 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lemke LB, Ge Z, Whary MT, Feng Y, Rogers AB, Muthupalani S, Fox JG. Concurrent Helicobacter bilis infection in C57BL/6 mice attenuates proinflammatory H. pylori-induced gastric pathology. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77:2147–58. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01395-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ge Z, Feng Y, Muthupalani S, Eurell LL, Taylor NS, Whary MT, Fox JG. Coinfection with Enterohepatic Helicobacter species can ameliorate or promote Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric pathology in C57BL/6 mice. Infection and Immunity. 2011;79:3861–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05357-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin ME, Bhatnagar S, George MD, Paster BJ, Canfield DR, Eisen JA, Solnick JV. The impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on the gastric microbiota of the Rhesus Macaque. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lagergren J, Lagergren P. Recent developments in esophageal adenocarcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:232–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang L, Lu X, Nossa CW, Francois F, Peek RM, Pei Z. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the distal esophagus are associated with alterations in the microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:588–97. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang L, Francois F, Pei Z. Molecular pathways: pathogenesis and clinical implications of microbiome alteration in esophagitis and Barrett esophagus. Clinical Cancer Research. 2012;18:2138–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fan YP, Chakder S, Gao F, Rattan S. Inducible and neuronal nitric oxide synthase involvement in lipopolysaccharide-induced sphincteric dysfunction. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2001;280:G32–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.1.G32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Calatayud S, Garcia-Zaragoza E, Hernandez C, Quintana E, Felipo V, Esplugues JV, Barrachina MD. Downregulation of nNOS and synthesis of PGs associated with endotoxin-induced delay in gastric emptying. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2002;283:G1360–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00168.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. The multistep nature of cancer. Trends Genet. 1993;9:138–41. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dejea C, Wick E, Sears CL. Bacterial oncogenesis in the colon. Future Microbiol. 2013;8:445–60. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slattery ML, Curtin K, Sweeney C, et al. Diet and lifestyle factor associations with CpG island methylator phenotype and BRAF mutations in colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:656–63. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walter J, Ley R. The human gut microbiome: ecology and recent evolutionary changes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:411–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, et al. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–30. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, et al. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen W, Liu F, Ling Z, et al. Human intestinal lumen and mucosa-associated microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099–105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Muhlbauer M, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boleij A, van Gelder MM, Swinkels DW, et al. Clinical Importance of Streptococcus gallolyticus infection among colorectal cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:870–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shen XJ, Rawls JF, Randall T, Burcal L, Mpande CN, Jenkins N, Jovov B, Abdo Z, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Molecular characterization of mucosal adherent bacteria and associations with colorectal adenomas. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:138–47. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]