Abstract

Purpose

To compare a balanced steady-state free-precession sequence with a radial k-space trajectory and alternating repetition time fat-suppression (Radial-ATR) with other currently used fat-suppressed three-dimensional sequences for evaluating the articular cartilage of the knee joint at 3.0T.

Methods

Radial-ATR, FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR sequences with similar voxel volumes and identical scan times were performed at 3.0T on both knee joints of 5 volunteers. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) measurements were performed for all sequences using a double acquisition method and compared using Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon tests. Radial-ATR sequences with 0.3 mm and 0.4 mm isotropic resolution were also performed on the knee joints of 7 volunteers and 3 patients with osteoarthritis.

Results

Average SNR values for cartilage, synovial fluid, and bone marrow were 54.7, 153.3, and 12.9 respectively for Radial-ATR, 30.8, 44.1, and 1.9 respectively for FSE-Cube, 13.3, 46.9, and 3.3 respectively for GRASS, and 19.1, 8.1, and 2.1 respectively for SPGR. Average CNR values between cartilage and synovial fluid and between cartilage and bone marrow were 98.6 and 41.8 respectively for VIPR-ATR, 13.4 and 28.8 respectively for FSE-Cube, 33.6 and 10.0 respectively for GRASS, and 11.0 and 16.9 respectively for SPGR. Radial-ATR had significantly higher (p<0.001) cartilage, synovial fluid, and bone marrow SNR and significantly higher (p<0.01) CNR between cartilage and synovial fluid and between cartilage and bone marrow than FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR. Radial-ATR provided excellent visualization of articular cartilage at high isotropic resolution with no image degradation due to off-resonance banding artifacts.

Conclusion

Radial-ATR had superior SNR efficiency to other fat-suppressed three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences and produced high isotropic resolution images of the knee joint which could be used for evaluating articular cartilage at 3.0T.

Keywords: MRI, Cartilage, Three-Dimensional, Isotropic Resolution, Knee

Introduction

High resolution magnetic resonance (MR) imaging techniques play an important role in evaluating the articular cartilage of the knee joint. High resolution images allow for early detection of cartilage lesions in symptomatic patients (1) and provide more accurate cartilage volume analysis in osteoarthritis research studies (2). Three-dimensional sequences are superior to two-dimensional sequences for high resolution cartilage imaging due their improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) efficiency and ability to acquire thin continuous slices through joints (3–5). Various three-dimensional sequences have been used to evaluate articular cartilage including gradient-echo sequences with dark synovial fluid (6) and bright synovial fluid (7), dual-echo in the steady-state (DESS) (8), driven equilibrium fourier transform (DEFT) (9), fast spin-echo sequences (10), and balanced steady-state free-precession (bSSFP) sequences (11, 12). Fat suppression is typically added to these sequences to optimize the dynamic contrast range of the image, reduce chemical shift artifact, and improve the detection of subchondral bone marrow edema which is an important secondary sign of cartilage degeneration. The fact that so many fat-suppressed three-dimensional cartilage imaging techniques exist illustrates the inherent limitations of each imaging strategy.

bSSFP sequences in particular offer many advantages for evaluating articular cartilage. The sequences have high SNR efficiency and produce images with bright synovial fluid and excellent tissue contrast (3, 12, 13). Various methods have been used to suppress fat signal on bSSFP images, but all currently used techniques have limitations. Frequency selective fat-suppressed bSSFP periodically interrupts the steady-state to saturate fat spins, but the fat signal is partially restored during each imaging interval (14). Water excitation bSSFP effectively suppresses fat signal but requires long repetition times (TR) which lead to off-resonance banding artifacts in areas of magnetic field inhomogeneity (15). Fluctuating equilibrium magnetic resonance (FEMR) (16) and linear combination (LC) bSSFP (17) separate fat and water signal without a loss in SNR efficiency, but the optimal TR needed for successful implementation at 3.0T allows little time for spatial encoding and thereby limits spatial resolution. Moreover, LC-SSFP spectral response shows a pass-band width of 1/2TR as compared to 1/TR for conventional SSFP.

Alternating repetition time (ATR) methods have been developed for bSSFP imaging to create more time for spatial encoding while minimizing off-resonance banding artifacts. Wideband bSSFP utilizes ATR to create a steady-state with a pass-band approximately 1.5 times wider than the pass-band of conventional bSSFP which reduces banding artifacts but provides no fat-suppression (18). Leupold and associates described a method which combines radiofrequency (RF) phase cycling with ATR to provide fat-suppression for bSSFP imaging at 3.0T. The technique suppresses fat signal by using one broad stop-band centered at 440 Hz and three pass-bands at a TR1:TR2 ratio of 1:3 with a 3.6 ms TR1 for spatial encoding and an effective TR of 4.6 ms (19). However, most applications of the ATR method of fat-suppression have been demonstrated with spatial resolution at or just below 1mm as their use of Cartesian k-space trajectories require spatial pre-encoding and rewinding pulses which reduces data acquisition time.

A new bSSFP technique called Radial-ATR has been recently developed which combines the ATR method of fat-suppression with a three-dimensional radial k-space trajectory and addresses many of the challenges associated with high resolution fat-suppressed bSSFP imaging (20). The out-and-back radial k-space trajectory requires no phase encoding, slice encoding, or dephasing gradients which allows data acquisition to occur throughout the entire TR1 interval during which spatial encoding is performed. The radial k-space trajectory allows fat-suppressed bSSFP images to be created using the ATR method with significantly higher spatial resolution than a Cartesian k-space trajectory. This study was performed to compare the SNR efficiency of Radial-ATR with other fat-suppressed three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences and to determine the feasibility of using Radial-ATR for high resolution cartilage imaging of the knee joint at 3.0T.

Materials and Methods

Description of Radial–ATR Sequence

Radial–ATR is a bSSFP sequence which produces fat suppressed three-dimensional images of the knee joint with T1/T2 tissue contrast and high isotropic resolution (20). The sequence utilizes a three-dimensional out-and-back radial k-space trajectory which allows for almost continuous acquisition of image data (21). Fat-suppression is achieved using an ATR method in which two different alternating length TRs and RF phase cycling is utilized to shape the spectral frequency response to place a stop-band over the fat resonance. The longer TR1 is used for data acquisition, while the shorter TR2 is used to modify the frequency response function (19).

Radial-ATR uses a thick slab-select excitation to reduce slab refocusing time and a three-dimensional dual half-echo radial k-space trajectory (21). The radial trajectory requires no phase encoding or slice encoding since data acquisition begins and ends at the k-space origin. The thick slab selection, short slab refocusing time, and absence of phase encoding, slice encoding, or dephasing gradients allows data acquisition to occur throughout the entire TR1 interval during which spatial encoding is performed. For the TR1 and TR2 of 3.45ms and 1.15ms respectively needed for optimal fat-suppression using the ATR method (19), the maximum achievable isotropic resolution with a radial trajectory is 0.3 mm as compared to 0.5 mm with a Cartesian trajectory. Corrections are made for deviations of the radial k-space trajectory due to eddy current effects and anisotropic gradient delays by spatially encoding a thin test slice with a bipolar gradient pulse and analyzing the resulting phase (22).

The location and widths of the stop-band in the ATR method of fat-suppression is designed through selection of TR1, TR2, and the RF phase cycling scheme. To provide a sufficiently wide stop-band for fat centered at the 3.0T fat resonance, TR1 and TR2 are chosen to be 3.45ms and 1.15ms respectively which results in an effective TR of 4.6 ms. The phase of the second RF pulse is shifted 180° with respect to the first RF pulse, to match the phase evolution of fat spins during theTR1 interval. When combined with conventional 0°–180° bSSFP phase cycling, a 0°–180°–180°–0° cycle is generated that repeats every four RF pulses (19). Radial–ATR uses a 15° flip angle, 0.3 ms and 1.8 ms echo times (TE) for the first and second half-echo respectively, ±125 kHz bandwidth, and one signal average. With a 15 cm field of view (FOV) and either a 256 × 256, 384 × 384, or 512 × 512 matrix, Radial–ATR produces fat-suppressed three-dimensional images of the knee joint with 0.6 mm and 0.4 mm isotropic resolution in 5 minutes and 0.3 mm isotropic resolution in 8 minutes.

Study Group

The study was performed in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations and with approval from our institutional review board. All subjects signed written informed consent prior to participation in the study. All subjects underwent an MR examination of the knee using the same 3.0T scanner (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI; maximum gradient strength of 50 mT/m and maximum slew rate of 200 mT·m−1·sec−1) and an 8-channel phased-array extremity coil (Precision Eight TX/TR High Resolution Knee Array; In Vivo, Orlando, FL).

A study group consisting of 5 asymptomatic volunteers (4 males and 1 female with an age range between 23 years and 28 years and an average age of 26.6 years) was used to compare the SNR performance of Radial-ATR with other fat-suppressed three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences. All subjects underwent an MR examination of both knees consisting of double acquisition sagittal Radial-ATR, three-dimensional fast spin-echo (FSE-Cube), three-dimensional gradient recall-echo acquired in the steady-state (GRASS), and three-dimensional spoiled gradient recall-echo (SPGR) sequences with the double acquisition of each sequence performed one immediately following the other. The sequences used the imaging parameters summarized in Table 1 and were optimized to produce 0.6 mm isotropic resolution images of the knee joint, or as close as possible, in a 5 minute scan time (7, 23). FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR utilized autocalibrating reconstruction for cartesian sampling (ARC) for parallel imaging. FSE-Cube used a spectral inversion recovery pulse for fat-suppression, while GRASS and SPGR used a chemical shift fat-water separation method called iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least-squares estimation (IDEAL) (7, 23, 24). To compare tissue contrast of bSSFP sequences with and without fat-suppression, double acquisition Radial-ATR and non-fat-suppressed conventional bSSFP (Radial-bSSFP) sequences were also performed one immediately following the other on the knee joint of a single 27 year male asymptomatic volunteer. Radial-bSSFP used the same radial k-space trajectory as Radial-ATR and was acquired with a TR of 2.9 ms, TE of 0.5 ms, 15° flip angle, 125 kHz bandwidth, 15 cm field of view, 256 × 256 matrix, 0.6mm slice thickness, 256 slices, and 5 minute scan time.

Table 1.

Acquisition parameters for the three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences

| Imaging Parameter | Radial-ATR | FSE-Cube | GRASS | SPGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR (ms) | 4.6 | 2217 | 12.4 | 12.4 |

| TE (ms) | 0.3/1.8 | 23.6 | 3.4/4.2/5.0 | 3.4/4.2/5.0 |

| Flip Angle (deg) | 15 | 90 | 50 | 14 |

| Bandwidth (kHz) | 125 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 31.2 |

| Field of View (cm) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Matrix | 256 × 256 | 256 × 256 | 384 × 224 | 384 × 224 |

| Slice Thickness (mm) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| In-Plane Resolution (mm) | 0.6 × 0.6 | 0.6 × 0.6 | 0.4 × 0.7 | 0.4 × 0.7 |

| Voxel Volume (mm3) | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Number of Slices | 256 | 392 | 84 | 84 |

| Scan Time (min) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

A second study group consisting of 7 asymptomatic volunteers (3 males and 4 females with an age range between 23 years and 28 years and an average age of 25.4 years) and 3 patients with Kellgren-Lawrence grades 1 or 2 knee osteoarthritis (2 males and one female with an age range between 46 years and 52 years and an average age of 48.0 years) was used to determine the feasibility of Radial-ATR for performing high resolution cartilage imaging of the knee joint. All subjects underwent an MR examination of the knee consisting of sagittal 0.4 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR, 0.3 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR, FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR sequences. The imaging parameters of all sequences were identical to those summarized in Table 1 except that 0.4 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR used a 384 × 384 matrix, 0.4 mm × 0.4 mm in-plane resolution, 0.4 mm slice thickness, and 5 minute scan time and 0.3 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR used a 512 × 512 matrix, 0.3 mm × 0.3 mm in-plane resolution, 0.3 mm slice thickness, and 8 minute scan time.

Image Analysis

The MR examinations of subjects in the first study group were used to compare SNR performance of the three-dimensional sequences. All images were up-sampled by SINC interpolation to get the same display matrix. Addition and subtraction images for each sequence were created using Image J software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2012). The SNR of cartilage, synovial fluid, and bone marrow and the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) between cartilage and synovial fluid and between cartilage and bone marrow were calculated using a double acquisition method previously described for parallel imaging techniques (25). Regions of interests (ROIs) containing 20 pixels for cartilage and synovial fluid, 50 pixels for bone marrow, and 200 pixels for muscle were placed at identical locations on the addition and subtraction images for all sequences. Signal was defined as the average signal within the ROI in cartilage, synovial fluid, and bone marrow on the addition images, while noise was defined as the standard deviation of the signal within the ROI in muscle on the subtraction images. The ROI in muscle was placed at a location where motion, pulsation, or aliasing artifact would not influence the stochastic noise measurement. SNR and CNR values were calculated using the following equations:

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

No attempt was made to normalize SNR to voxel volume to account for the SNR advantage of GRASS and SPGR which had more than 25% larger voxel volume than Radial-ATR and FSE-Cube. Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon tests were used to compare SNR and CNR between sequences with differences considered statistically significant for p-values less than 0.05.

The MR examinations of subjects in the second study group were evaluated independently by two fellowship-trained musculoskeletal radiologists (authors H.G.R. and K.S.L.) with 4 and 6 years of clinical experience to determine whether Radial-ATR could be used for high resolution cartilage imaging. The radiologists assessed the 0.3 mm and 0.4 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR sequences based upon the following four qualitative measures of image quality: tissue contrast, clarity of articular surface, cartilage lesion conspicuity, and artifacts. A four-level scale was used for qualitative assessment in which a score of 4 indicated excellent image quality, a score of 3 indicated good image quality, a score of 2 indicated acceptable image quality, and a score of 1 indicated poor image quality (26).

Results

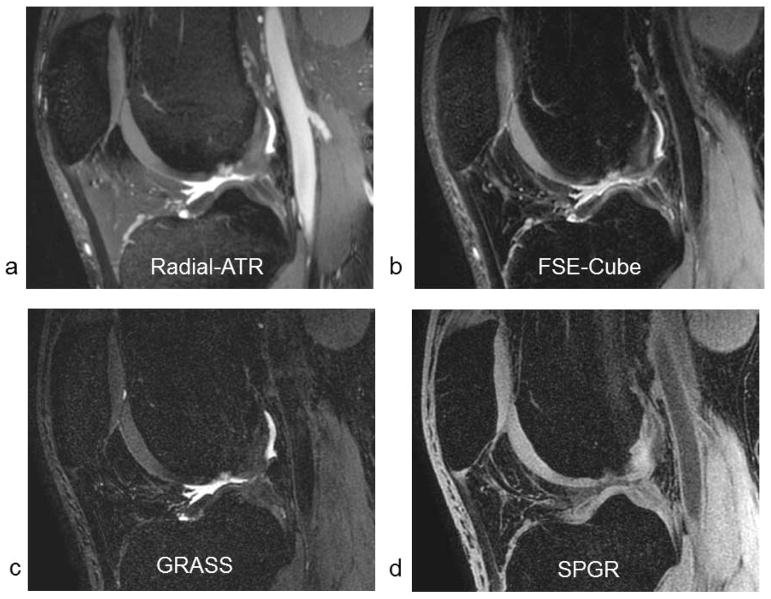

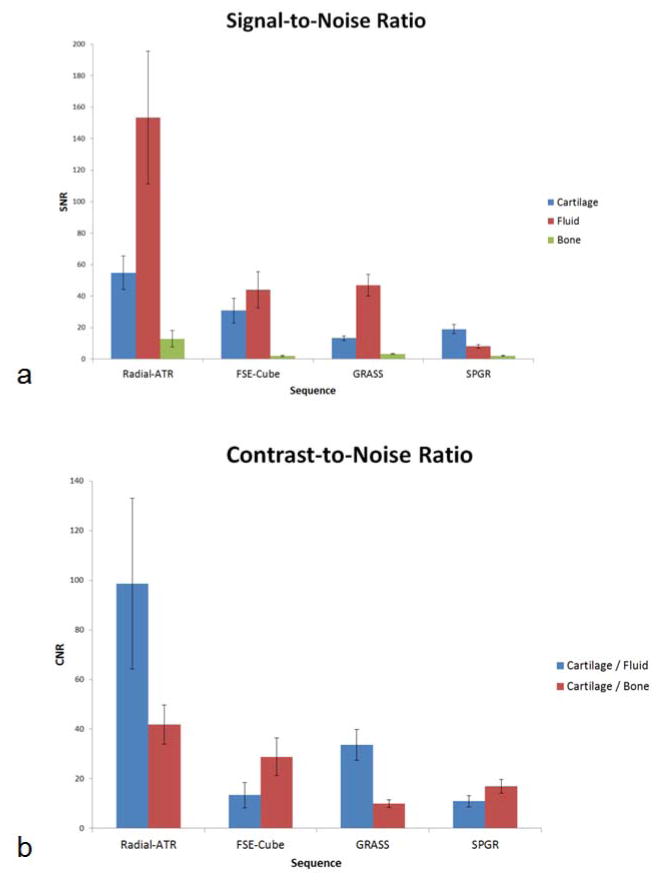

Comparison Radial-ATR, FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR images of the knee joint with similar voxel volumes and identical scan times are shown in Figure 1. Average SNR values for cartilage, synovial fluid, and bone marrow were 54.7, 153.3, and 12.9 respectively for Radial-ATR, 30.8, 44.1, and 1.9 respectively for FSE-Cube, 13.3, 46.9, and 3.3 respectively for GRASS, and 19.1, 8.1, and 2.1 respectively for SPGR. Average CNR values between cartilage and synovial fluid and between cartilage and bone marrow were 98.6 and 41.8 respectively for VIPR-ATR, 13.4 and 28.8 respectively for FSE-Cube, 33.6 and 10.0 respectively for GRASS, and 11.0 and 16.9 respectively for SPGR. Radial-ATR had significantly higher (p<0.001) SNR of cartilage and synovial fluid than FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR. However, Radial-ATR also had significantly higher (p<0.001) SNR of bone marrow than the other sequences indicating decreased ability to suppress fat signal (Figure 2a). Radial-ATR had significantly higher (p<0.001) CNR between cartilage and synovial fluid and significantly higher (p<0.01) CNR between cartilage and bone marrow than FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR (Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

Sagittal (a) Radial-ATR, (b) FSE-Cube, (c) GRASS, and (d) SPGR images of the knee joint with similar voxel volumes and identical scan times in a 25 year old male asymptomatic volunteer.

Figure 2.

Comparison of (a) SNR and (b) CNR for the fat-suppressed three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences.

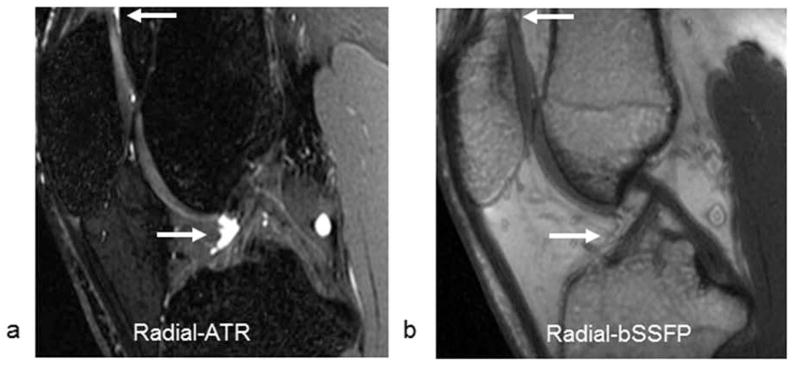

Comparison Radial-ATR and Radial-bSSFP images of the knee joint with identical voxel volumes and scan times are shown in Figure 3. SNR values for cartilage, synovial fluid, and bone marrow were 51.2, 146.5, and 14.7 respectively for Radial-ATR and 70.4, 95.7, and 97.5 respectively for Radial-bSSFP. CNR values between cartilage and synovial fluid and between cartilage and bone marrow were 95.3 and 36.5 respectively for Radial-ATR and 25.3 and 27.1 respectively for Radial-bSSFP.

Figure 3.

Sagittal (a) Radial-ATR and (b) Radial-bSSFP images of the knee joint with similar voxel volumes and identical scan times in a 27 year old male asymptomatic volunteer. Note the high contrast between synovial fluid (arrows) and adjacent cartilage and fat on the Radial-ATR image. The synovial fluid (arrows) on the Radial-bSSFP image cannot even be visualized since its signal intensity is almost identical to the signal intensity of adjacent fat.

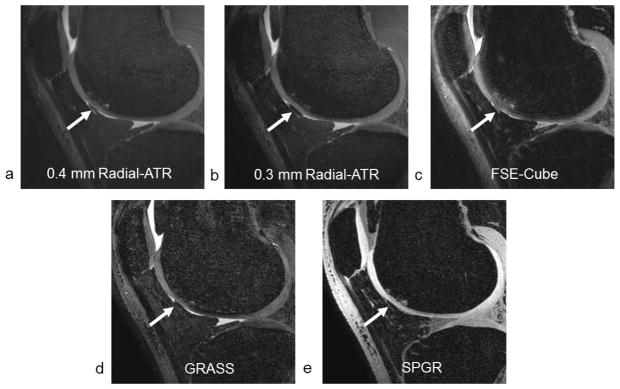

The 0.3 mm and 0.4 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR sequences received high scores from both radiologists for all four qualitative measures of image quality. The average score for tissue contrast, clarity of articular surface, cartilage lesion conspicuity, and artifacts were 4.0, 3.8, 3.8, and 4.0 respectively for 0.4 mm isotropic resolution VIPR-ATR and 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, and 4.0 respectively for 0.3 mm isotropic resolution VIPR-ATR. The high in-plane spatial resolution, thin slices, excellent tissue contrast, and absence of blurring on Radial-ATR images resulted in increased clarity and sharpness of the articular surface and excellent visualization of cartilage lesions (Figure 4). Radial-ATR was also able to detect other joint pathology in patients with knee osteoarthritis including meniscal and ligament tears, tendinopathy, and subchondral cysts (Figure 5). No degradation of image quality due to off-resonance banding artifacts was noted.

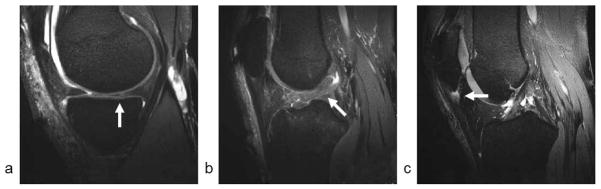

Figure 4.

Sagittal (a) 0.4 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR, (b) 0.3 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR, (c) FSE-Cube, (d) GRASS, and (e) SPGR images of the knee joint in a 51 year old male patient with osteoarthritis show a partial-thickness cartilage lesion on the femoral trochlea (arrows).

Figure 5.

(a and b) Sagittal 0.3 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR images of the knee joint in a 51 year old male patient with osteoarthritis show a posterior horn medial meniscus tear (arrow in a) and anterior cruciate ligament tear (arrow in b). (c) Sagittal 0.3 mm isotropic resolution Radial-ATR image of the knee joint in a 46 year old male patient with osteoarthritis shows patellar tendinopathy (arrow).

Discussion

Radial-ATR acquired fat-suppressed three-dimensional images of the knee joint at 3.0T with 0.4 mm to 0.6 mm isotropic resolution in 5 minutes and 0.3 mm isotropic resolution in 8 minutes. The isotropic source data could be used to create multi-planar reformat images which allowed articular cartilage to be evaluated in any orientation following a single acquisition. Radial-ATR compared favorably with other fat-suppressed three-dimensional sequences for evaluating the articular cartilage of the knee joint at 3.0T.

Radial-ATR had significantly higher cartilage and synovial fluid SNR than FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR sequences with similar voxel volumes and identical scan times. The higher SNR of Radial-ATR was likely due to the greater signal generated by the bSSFP technique. When compared to a non-fat-suppressed conventional bSSFP sequence using a similar radial k-space trajectory, Radial-ATR showed an expected modest reduction in cartilage SNR while providing improved tissue contrast by reducing unwanted fat signal. Radial-ATR images were not degraded by off-resonance banding artifacts, which commonly occur when using other fat-suppressed bSSFP sequences, due to its ability to maintain a wide pass-band at high isotropic resolutions. The radial k-space trajectory allowed fat-suppressed bSSFP images to acquired using the ATR method with significantly higher resolution than a Cartesian trajectory. Radial-ATR acquired higher isotropic resolution images of the knee joint at 3.0T in identical or shorter periods of time than Cartesian-based fat-suppressed three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences currently available on both GE Healthcare (23) and Siemens (27) MR platforms.

One limitation of Radial-ATR for evaluating articular cartilage is its suboptimal fat-suppression. Radial-ATR had significantly higher bone marrow SNR than FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR sequences indicating a decreased ability to suppress fat signal. The frequency selective stop-band placed over the fat resonance on Radial-ATR has a significant ripple which may not remove all fat signal from the image (19). Thus, it is not surprising that Radial-ATR had higher bone marrow SNR than FSE-Cube which used a spectral inversion recovery pulse and GRASS and SPGR which used a chemical shift fat-water separation method. Despite its decreased ability to suppress fat signal, Radial-ATR had greater CNR between cartilage and bone marrow than the other sequences which can be attributed to its much higher cartilage SNR. Nevertheless, the reduced fat-suppression of Radial-ATR may decrease its sensitivity for detecting bone marrow edema lesions and subchondral cysts in patients with osteoarthritis. We are currently investigating modifications in design parameters of Radial-ATR such as changes in the TR1:TR2 ratio and the order in which TR1 and TR2 are interleaved which may reduce the ripple in the fat stop-band and thereby improve fat-suppression. Additional modifications of the ATR technique have also been described to provide improved fat-suppression for bSSFP imaging. Cukur and associates described a multiple acquisition ATR method for fat-water separation using in-phase and out-of-phase bSSFP images (28). Lee and associates used a single acquisition multiple TR method to create a wider stop-band over the fat frequency which provided improved fat-suppression at the cost of reduced SNR efficiency and increased scan time (29).

Vastly undersampled isotropic steady-state free-precession (VIPR-SSFP) is another bSSFP sequence which uses a radial k-space trajectory to produce fat-suppressed three-dimensional images of the knee joint with 0.4 mm isotropic resolution in 5 minutes (22). Previous studies have shown favorable comparisons between VIPR-SSFP and other two-dimensional and three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences at 3.0T (22, 23). However, VIPR-SSFP utilizes a linear combination fat-water separation method which requires two k-space acquisitions and places the center frequency halfway between fat and water resonances (17). VIPR-SSFP also uses a point- by-point phase correction to avoid blurring as water accrues a phase shift over the out and back trajectory. The need for VIPR-SSFP to image off-resonance ultimately results in image blurring and suboptimal fat-suppression at isotropic resolutions higher than 0.4 mm. Since Radial-ATR is acquired on the water resonance, there are no resolution dependent effects on imaging blurring or fat-suppression and no need for point-by-point phase correction. In addition, Radial-ATR requires only a single k-space acquisition which allows more unique radial projects to be obtained in the same scan time which reduces undersampling artifact.

Our study had several limitations. One limitation was that Radial-ATR was not compared to all currently used three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences including DESS, true fast imaging with steady-state precession (true-FISP), and sampling perfection with application oriented contrasts using different flip angle evolutions (SPACE) (27). However, many of the sequences used in cartilage comparison studies are available only on certain MR vendor platforms, and thus it would be difficult to directly compare all three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences in a single study. Another limitation of our study was that the Radial-ATR was only used to evaluate a small number of patients with osteoarthritis. However, the objective of this study was merely to compare the SNR performance of Radial-ATR with other fat-suppressed three-dimensional sequences and to document the feasibility of using Radial-ATR for high resolution cartilage imaging. Larger clinical studies with surgical correlation are needed to better assess the ability of Radial-ATR to detect cartilage lesions and other joint pathology in patients with osteoarthritis. A final limitation of our study was that the SNR of cartilage, synovial fluid, and bone marrow could not be calculated using noise measurements obtained separately in each individual tissue. Measuring noise in small ROIs placed in cartilage and synovial fluid utilizing the double acquisition method is prone to error due to the small number of pixels used for noise measurements and imperfect co-registration of subtraction images (23). Thus, we felt that using the standard deviation of signal on the subtraction images in a large ROI placed at identical locations in muscle, which appears homogenous on all sequences, would provide the most accurate assessment of image noise.

In conclusion, Radial-ATR produced multi-planar fat-suppressed three-dimensional images of the knee joint with high isotropic resolution at 3.0T which provided excellent visualization of the articular cartilage of the knee joint. Radial-ATR had higher cartilage and synovial fluid SNR than FSE-Cube, GRASS, and SPGR sequences with similar voxel volumes and identical scan times. The improved SNR efficiency allowed Radial-ATR to acquire higher isotropic resolution images of the knee joint than other currently available fat-suppressed three-dimensional cartilage imaging sequences with no image degradation due to off-resonance banding artifacts. Due to its highly versatile bSSFP tissue contrast (11, 30), Radial-ATR may also be useful for evaluating the menisci, ligaments, bone marrow, and other joint structures which can be sources of pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Additional studies are needed to determine whether Radial-ATR can be used to detect early cartilage degeneration in clinical practice and to provide rapid “whole-organ” joint assessment and cartilage volume analysis in osteoarthritis research studies.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Coulter Translational Research Partnership, NIAMS U01 AR059514-01, and GE Healthcare.

References

- 1.Rubenstein JD, Li JG, Majumdar S, Henkelman RM. Image resolution and signal-to-noise ratio requirements for MR imaging of degenerative cartilage. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1997;169(4):1089–96. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardya PA, Newmark R, Liu YM, et al. The influence of the resolution and contrast on measuring the articular cartilage volume in magnetic resonance images. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2000;18(8):965–72. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kijowski R, Lu A, Block W, Grist T. Evaluation of the articular cartilage of the knee joint with vastly undersampled isotropic projection reconstruction steady-state free precession imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2006;24(1):168–75. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold GE, Hargreaves BA, Vasanawala SS, et al. Articular cartilage of the knee: evaluation with fluctuating equilibrium MR imaging--initial experience in healthy volunteers. Radiology. 2006;238(2):712–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2381042183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hargreaves BA, Gold GE, Beaulieu CF, Vasanawala SS, Nishimura DG, Pauly JM. Comparison of new sequences for high-resolution cartilage imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;49(4):700–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Disler DG, McCauley TR, Kelman CG, et al. Fat-suppressed three-dimensional spoiled gradient-echo MR imaging of hyaline cartilage defects in the knee: comparison with standard MR imaging and arthroscopy. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1996;167(1):127–32. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.1.8659356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kijowski R, Tuite M, Passov L, Shimakawa A, Yu H, Reeder SB. Cartilage imaging at 3.0T with gradient refocused acquisition in the steady-state (GRASS) and IDEAL fat-water separation. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2008;28(1):167–74. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy PA, Recht MP, Piraino D, Thomasson D. Optimization of a dual echo in the steady state (DESS) free-precession sequence for imaging cartilage. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 1996;6(2):329–35. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880060212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold GE, Fuller SE, Hargreaves BA, Stevens KJ, Beaulieu CF. Driven equilibrium magnetic resonance imaging of articular cartilage: initial clinical experience. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2005;21(4):476–81. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kijowski R, Davis KW, Woods MA, et al. Knee joint: comprehensive assessment with 3D isotropic resolution fast spin-echo MR imaging--diagnostic performance compared with that of conventional MR imaging at 3.0 T. Radiology. 2009;252(2):486–95. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2523090028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kijowski R, Blankenbaker DG, Klaers JL, Shinki K, De Smet AA, Block WF. Vastly undersampled isotropic projection steady-state free precession imaging of the knee: diagnostic performance compared with conventional MR. Radiology. 2009;251(1):185–94. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511081133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duc SR, Koch P, Schmid MR, Horger W, Hodler J, Pfirrmann CW. Diagnosis of articular cartilage abnormalities of the knee: prospective clinical evaluation of a 3D water-excitation true FISP sequence. Radiology. 2007;243(2):475–82. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2432060274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold GE, Reeder SB, Yu H, et al. Articular cartilage of the knee: rapid three-dimensional MR imaging at 3.0 T with IDEAL balanced steady-state free precession--initial experience. Radiology. 2006;240(2):546–51. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheffler K, Heid O, Hennig J. Magnetization preparation during the steady state: Fat-saturated 3D TrueFISP. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;45(6):1075–80. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kornaat PR, Doornbos J, van der Molen AJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of knee cartilage using a water selective balanced steady-state free precession sequence. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2004;20(5):850–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasanawala SS, Pauly JM, Nishimura DG. Fluctuating equilibrium MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;42(5):876–83. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199911)42:5<876::aid-mrm6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasanawala SS, Pauly JM, Nishimura DG. Linear combination steady-state free precession MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2000;43(1):82–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200001)43:1<82::aid-mrm10>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nayak KS, Lee HL, Hargreaves BA, Hu BS. Wideband SSFP: alternating repetition time balanced steady state free precession with increased band spacing. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;58(5):931–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leupold J, Hennig J, Scheffler K. Alternating repetition time balanced steady state free precession. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;55(3):557–65. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klaers K, Brodsky E, Block W, Kijowski R. High resolution cartilage and whole-organ knee joint assessment: 3D radial fat-suppressed alternating repetition time steady-state free-precession. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Stockholm. 2010. (abstract 657) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu A, Brodsky E, Grist TM, Block WF. Rapid fat-suppressed isotropic steady-state free precession imaging using true 3D multiple-half-echo projection reconstruction. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;53(3):692–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klaers J, Jashnani Y, Jung Y, et al. Dual half-echo phase correction for implementation of 3D radial SSFP at 3.0 T. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(2):282–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CA, Kijowski R, Shapiro LM, et al. Cartilage morphology at 3.0T: assessment of three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging techniques. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2010;32(1):173–83. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeder SB, McKenzie CA, Pineda AR, et al. Water-fat separation with IDEAL gradient-echo imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2007;25(3):644–52. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dietrich O, Raya JG, Reeder SB, Reiser MF, Schoenberg SO. Measurement of signal-to-noise ratios in MR images: influence of multichannel coils, parallel imaging, and reconstruction filters. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2007;26(2):375–85. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsch GH, Juras V, Szomolanyi P, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee at 3 and 7 tesla: a comparison using dedicated multi-channel coils and optimised 2D and 3D protocols. European radiology. 2012;22(9):1852–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedrich KM, Reiter G, Kaiser B, et al. High-resolution cartilage imaging of the knee at 3T: basic evaluation of modern isotropic 3D MR-sequences. European journal of radiology. 2011;78(3):398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cukur T, Nishimura DG. Fat-water separation with alternating repetition time balanced SSFP. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60(2):479–84. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KJ, Lee HL, Hennig J, Leupold J. Use of simulated annealing for the design of multiple repetition time balanced steady-state free precession imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;68(1):220–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duc SR, Pfirrmann CW, Koch PP, Zanetti M, Hodler J. Internal knee derangement assessed with 3-minute three-dimensional isovoxel true FISP MR sequence: preliminary study. Radiology. 2008;246(2):526–35. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462062092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]