Abstract

The cyclic di-nucleotide bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric adenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP) is a candidate mucosal adjuvant with proven efficacy in preclinical models. It was shown to promote specific humoral and cellular immune responses following mucosal administration. To date, there is only fragmentary knowledge on the cellular and molecular mode of action of c-di-AMP. Here, we report on the identification of dendritic cells and macrophages as target cells of c-di-AMP. We show that c-di-AMP induces the cell surface up-regulation of T cell co-stimulatory molecules as well as the production of interferon-β. Those responses were characterized by in vitro experiments with murine and human immune cells and in vivo studies in mice. Analyses of dendritic cell subsets revealed conventional dendritic cells as principal responders to stimulation by c-di-AMP. We discuss the impact of the reported antigen presenting cell activation on the previously observed adjuvant effects of c-di-AMP in mouse immunization studies.

Introduction

To better manage health risks and costs, modern vaccines are no longer made from whole pathogens. Rather, they contain antigenic subunits that mainly provide the immune target to elicit memory responses against a broad spectrum of the pathogen's strains and clades. For efficacy, most subunit vaccines require additional factors, so-called adjuvants; among them are pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Vaccine adjuvants can compensate for the lack of danger signals in subunit-based formulations, thereby improving the activation of innate and adaptive immune responses. Cyclic di-nucleotides are one such group of promising candidate adjuvants [1]. They are signaling molecules which are involved in critical processes such as attachment and biofilm formation in prokaryotes and they control cell motility and proliferation states in the protozoon dictyostelium [2]–[5]. Recently, an additional cyclic di-nucleotide, cyclic [G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] (cGAMP), was reported to activate the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and to be synthesized by the mammalian enzyme cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) upon stimulation with foreign DNA [6]–[9]. Cyclic di-nucleotides such as bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric adenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP), bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP), and bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric inosine monophosphate (c-di-IMP) proved to have immune modulatory activity in mice and humans [10]–[17]. We and others have previously shown that c-di-AMP, c-di-GMP, and c-di-IMP act as potent adjuvants in immunization experiments with mice [12], [16], [18], [19]. We demonstrated that c-di-AMP promotes humoral as well as cellular immune responses to model and vaccine antigens in mice immunized via the mucosal route. Immune modulation by c-di-AMP was observed to contribute to a balanced TH1/TH2/TH17 response [18]. Splenocytes from immunized mice re-stimulated in vitro with antigen in the presence of c-di-AMP showed enhanced proliferation activity. Furthermore, we demonstrated that in vitro antigen presentation by murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) results in increased T cell proliferation in the presence of c-di-AMP [18]. This last observation suggests a stimulatory effect of c-di-AMP on dendritic cells (DCs) leading to T cell activation. Additional studies demonstrated the capacity of cyclic di-nucleotides to induce the expression of type I interferons (IFNs) via activation of the axis: stimulator of IFN genes/TANK-binding kinase 1/IFN response factor 3 (STING/TBK1/IRF3) [13], [15], [20]–[22]. However, it is still unknown to which extent type I IFNs are responsible for adjuvanticity, as well as in which cell subtype(s) their production is specifically induced.

Pathogen-evoked immune stimulation and subsequent antigen processing and presentation is usually accompanied by PAMP signaling leading to activation and surface expression of T cell co-stimulatory molecules on antigen presenting cells (APCs). Only then do APCs become effective in priming T cells, an important step toward adaptive immunity and, eventually, memory. There is limited knowledge on the effector functions of c-di-AMP on immune cells, such as DCs. By and large, previous studies have been restricted to the murine system, they have addressed neither all APCs nor specific cell subsets, and they were generally limited to in vitro models. Here we asked which APCs are targeted by the putative PAMP mimicking effects of c-di-AMP that caused the observed T cell expansion [18]. To this end, we analyzed the effects of c-di-AMP application on different immune cells. We characterized the surface expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of type I IFN as hallmarks of innate immune activation and signaling leading to adaptive immune responses. The observed c-di-AMP effects were also confirmed for human immune cells. Our studies show that DCs and macrophages (MΦs) respond to c-di-AMP by exhibiting enhanced surface expression of T cell co-stimulatory molecules and IFN-β production. We further demonstrate the preferential activation of conventional DCs, known as principal stimulators of antigen-specific T cell responses.

Results

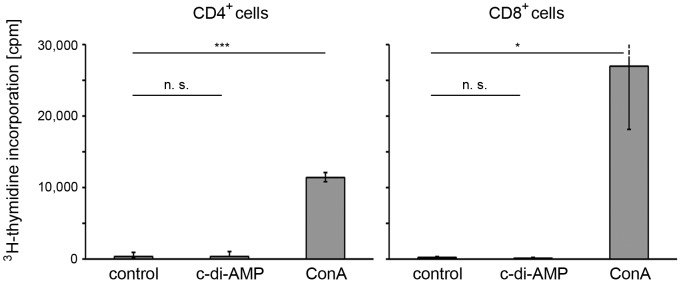

The c-di-AMP effect on T cell proliferation is not direct

First, we asked if the c-di-AMP-induced T cell proliferation that we reported previously [18] is an effect of the direct action of c-di-AMP on T cells, for example as a super antigen, in the absence of potential mediator cells. Murine CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from splenocyte preparations and incubated for 4 days with c-di-AMP. Significantly enhanced T cell proliferation, as assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation, was found after stimulation with concanavalin A (positive control) but not after c-di-AMP treatment (Figure 1). Based on this finding, further experiments focused on the identification of cells mediating the effect of c-di-AMP on T cell proliferation.

Figure 1. C-di-AMP does not directly affect murine T cell proliferation in vitro.

Murine splenocytes were sorted for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh, CD44low, CD25−) and treated with either 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP, 5 µg/ml concanavalin A (ConA; positive control), or left untreated (control) in the presence of 3H-thymidine. As a measure for proliferation, 3H-thymidine incorporation in T cells was determined by scintillation. The error bars show SEM for n = 3. Differences were statistically significant at p<0.001 (***), p<0.05 (*) or non-significant (n. s.) with respect to the control.

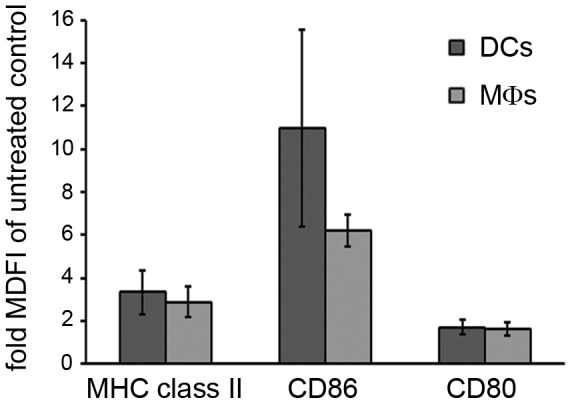

C-di-AMP affects surface expression of T cell receptor co-stimulatory molecules on murine DCs and MΦs in vitro

Activated APCs are characterized by up-regulated surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. To test if c-di-AMP directly up-regulates these molecules, murine BMDCs and bone marrow-derived MΦs were exposed for 24 h to c-di-AMP in vitro. Cell surface CD80, CD86, and MHC class II (I-A) were detected with fluorescently labeled antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. C-di-AMP treatment induced an up-regulation of surface MHC class II, CD80, and CD86 on DCs and MΦs when compared to cells grown in medium without additive (Figures 2 and S1).

Figure 2. C-di-AMP activates murine immune cells in vitro.

Murine bone marrow derived model dendritic cells (DCs, CD11c+) and model macrophages (MΦs, CD11b+) were incubated for 24 h with 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP or medium without additives (control). Cells were decorated with fluorescently labeled antibodies against MHC class II and the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. The diagram shows the normalized median fluorescence intensity (fold increase as compared to the control) analyzed by flow cytometry. Error bars are SEM for n = 3.

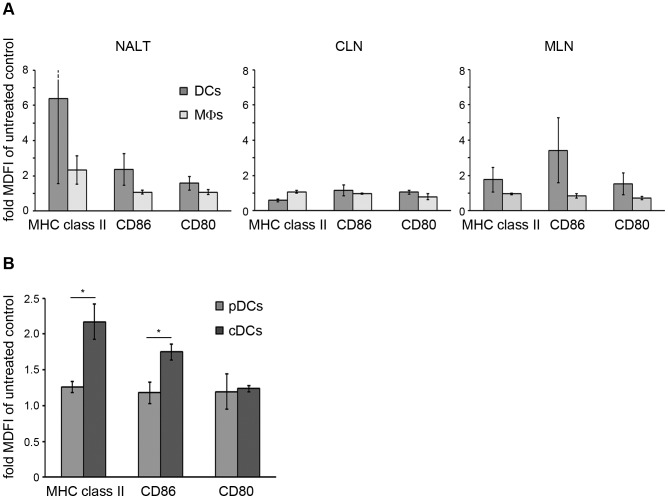

C-di-AMP application activates preferentially DCs of the murine nose-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) and the mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) in vivo

Our experiments demonstrated that c-di-AMP can directly activate DCs and MΦs in vitro. However, the experimental conditions would not necessarily match the architectural complexity of an inductive site or in terms of pharmacokinetics the in situ active concentration of c-di-AMP. Thus, we investigated if c-di-AMP is able to activate those APCs in vivo under the same conditions in which it exerts its adjuvant properties. To this end, c-di-AMP was intra-nasally (i. n.) administered to mice. After 24 h, DCs and MΦs from the NALT, the MLN and the cervical lymph nodes (CLN) were prepared and the surface expression of CD80, CD86 and MHC class II was analyzed by flow cytometry. Upon i. n. administration of c-di-AMP, the expression of MHC class II, CD80 and CD86 was clearly up-regulated in DCs of the NALT and the MLN (Figures 3A and S2A).

Figure 3. C-di-AMP up-regulates T cell co-stimulatory molecules preferentially on conventional murine dendritic cells (DCs).

(A) In vivo effects of c-di-AMP on mouse APCs. Flow cytometric analysis of DCs (CD11c+) and MΦs (CD11c−, CD11b+) from the nose-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT), the cervical lymph nodes (CLN) or the mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) 24 h after i. n. administration of c-di-AMP in mice. (B) In vitro effects of c-di-AMP on mouse DCs. Murine bone marrow derived model conventional (cDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) were generated by culturing in the presence of Flt3l and incubated for 24 h with 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP or without additives (control). Cells were decorated with fluorescently labeled antibodies against identification markers CD11c (DCs), CD11b (cDCs), B220 (pDCs), and MHC class II, CD80 and CD86. The diagrams show the normalized median fluorescence intensity (fold increase as compared to the control) analyzed by flow cytometry. Error bars are SEM for n = 3. Differences are statistically significant at p<0.01 (**) or p<0.05 (*).

Murine conventional DCs are the principal c-di-AMP responder DC subset in vitro

Since it is known that DCs occur in functionally distinct subsets, we tested the response of murine DC subsets to c-di-AMP application in vitro. BMDCs were cultured in the presence of FMS (Feline McDonough Sarcoma Virus) like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3l) to give rise to plasmacytoid and conventional DC subsets. Treatment with c-di-AMP for 24 h led to up-regulation of MHC class II and the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 preferentially in conventional DCs (Figures 3B and S2B).

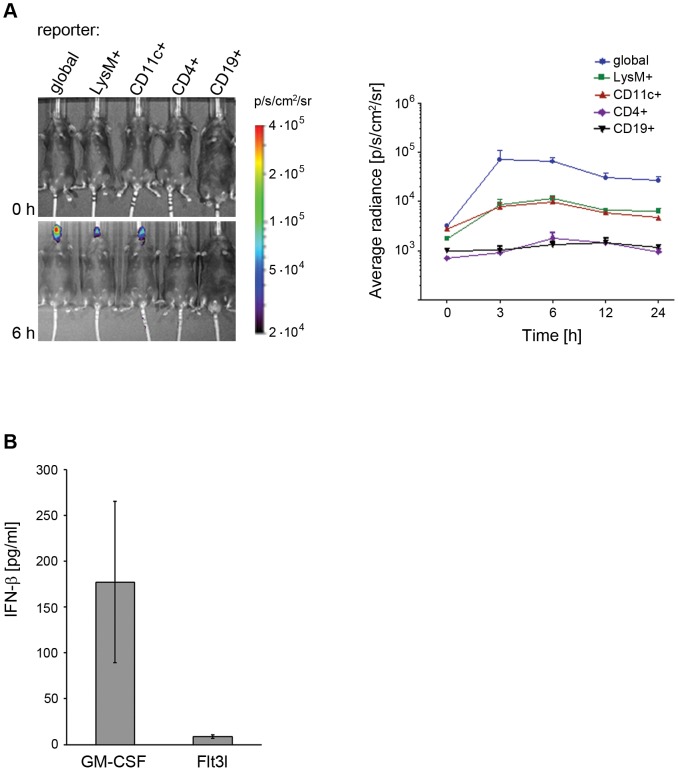

C-di-AMP application in mice leads to IFN-β reporter gene activation in DCs and the MΦ/monocyte/granulocyte population, but not in T and B cells

Activation of different immune cell types was further investigated in vivo by employing conditional IFN-β reporter mice. These transgenic mice provide the option to position a luciferase reporter under the control of the IFNB promoter by crossing them with mice expressing Cre recombinase under tissue or cell specific promoters. In this study we used mice with an activated reporter function in CD19+ B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD11c+ DCs, and LysM+ MΦs/monocytes/granulocytes. The tissue/cell specific luciferase expression was measured in vivo at different time points after i. n. administration of c-di-AMP in mice. Luciferase activity was detected as early as 3 h post administration of c-di-AMP, peaked after 6 h and was strongly reduced after 24 h in both DCs and the MΦ/monocyte/granulocyte population (Figure 4A). The kinetics observed in the cell subset specific reporter mice closely matched the one of the global reporter animal. Furthermore, studies performed using IFN receptor knockout mice carrying the reporter gene showed that reporter activation was independent of a paracrine activation loop (data not shown). Interestingly, the detected IFN-β reporter responses were strictly localized in the nasal tissue region. Since IFN-β production is a known hallmark of immune cell activation, these results strongly support DCs and MΦs as the main early responders to c-di-AMP in vivo. There are no reporter mice which allow us to dissect IFN-β activation in different DC subsets. Thus, in vitro studies were performed to further analyze the c-di-AMP induced IFN-β response of different DC subsets. To this end, bone marrow derived monocytes were cultured i) in the presence of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) resulting in an exclusively conventional DC population or ii) in the presence of Flt3l resulting in a mixed population of conventional and plasmacytoid DCs. After treatment with c-di-AMP, IFN-β was readily detected in the medium of DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF, whereas lower concentrations were observed in supernatant fluids of DCs cultured in the presence of Flt3l (Figure 4B). Hence, conventional DCs seem to be the major IFN-β producers upon stimulation with c-di-AMP.

Figure 4. C-di-AMP induces IFN-β production in murine dendritic cells (DCs).

(A) C-di-AMP targets the IFNB promoter in DCs and monocytes/macrophages/granulocytes in vivo. Mice of indicated phenotypes were i. n. treated with c-di-AMP: “CD4+” indicates T cell specific, “CD19+” B cell specifc, “LysM+” monocyte/macrophage/granulocyte specific, and “CD11c+” DC specific control of luciferase expression by the IFN-β promoter. Quantification of in vivo imaging signals derived from luciferase activity at different time points is shown for n = 5. Results are expressed as average of radiance (in photons/s/cm2/steridian). Error bars are SEM. (B) C-di-AMP induces IFN-β production in DCs in vitro. BMDCs were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF or Flt3l, as indicated on the x axis. IFN-β secretion was determined in the culture medium by ELISA. Error bars are SEM, n = 3.

C-di-AMP induces up-regulation of T cell co-stimulatory molecules and IFN-β production in human DCs

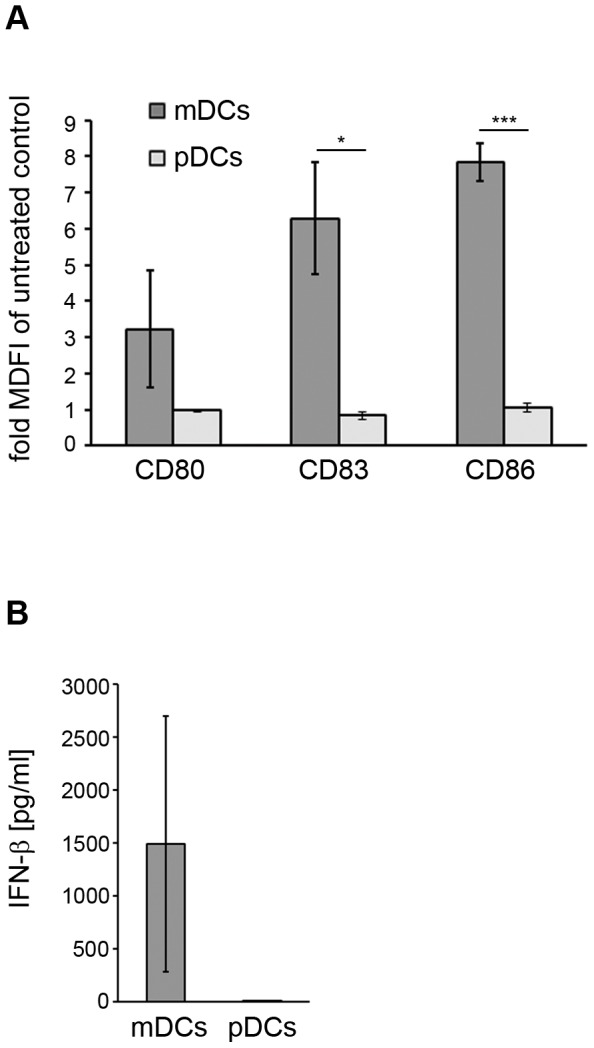

We next investigated if human DCs exhibit a similar response to c-di-AMP. To this end cultured human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC)-derived myeloid and plasmacytoid DCs were treated for 24 h with c-di-AMP or left untreated (control). Then, the expression of surface receptors critical for cross talk with T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry, and IFN-β secretion was evaluated by ELISA. Flow cytometry revealed that CD80, CD83 and CD86 expression was preferentially up-regulated in myeloid DCs but was virtually absent on plasmacytoid DCs after stimulation by c-di-AMP (Figures 5A and S3). Similarly to what was observed for murine cells, myeloid DCs were the major contributors to IFN-β secretion following c-di-AMP treatment (Figure 5B). Taken together, the myeloid DC subset (representing the conventional DC subset in human PBMCs) is the preferential responder to c-di-AMP (Figure 5).

Figure 5. C-di-AMP preferentially activates human myeloid dendritic cells (DCs) in vitro.

PBMC-derived human plasmacytoid DCs (pDC) or myeloid (conventional) DCs (mDC) were incubated for 24 h in the presence of 60 µg/ml c-di-AMP or without additive (control). (A) Cells were decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for the identification markers CD11c (mDC), CD303 (pDC) CD80, CD83 and CD86, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Normalized median fluorescence intensity (MDFI) is shown as fold increase compared to the control. Error bars show SEM for n = 3. (B) The medium from the cultured mDC or pDC was analyzed for IFN-β secretion by ELISA. Error bars show SEM for n = 3. Differences are statistically significant at p<0.001 (***) or p<0.05 (*).

Discussion

Adjuvants can modulate different steps involved in the elicitation of an adaptive immune response to an antigen. However, there is only fragmentary knowledge on the underlying molecular mechanisms of action of most adjuvants. The discovery of the role of PRRs (pattern recognition receptors) in PAMP binding and signaling revealed more details about the functional mode of action of PAMP-like adjuvant molecules, preferentially in cells of the innate immune system. Numerous PRRs and their ligands are described and their importance for adjuvant efficacy was investigated [23], [24]. For example, various PRR signaling pathways induce the expression of type I IFNs, which are important immune modulators [25], [26]. However, the current state of knowledge on mechanisms of adjuvant activity is far from explaining their observed immunological effector functions. Such information would accelerate the development of vaccines that promote immune responses able to efficiently clear specific pathogens [27]. A better understanding of the molecular basis of adjuvanticity could also promote the rational design of successful vaccines by supplementing them with the appropriate adjuvants or combinations thereof [27].

Here, we studied the effector functions of the candidate adjuvant c-di-AMP on different immune cells in vitro as well as in vivo. We asked which cell types undergo activation and which cellular processes and molecules are involved. We previously reported that c-di-AMP promotes antigen specific T cell proliferation [18]. C-di-AMP does not seem to directly exert this effect on T cells (Figure 1), thus we concluded that the observed T cell activation is mediated by other immune cell types. This was also suggested by previous in vitro studies showing that DCs which were antigen-loaded in the presence of c-di-AMP were more efficient at promoting the activation of antigen-specific T cells from TCR transgenic mice [18]. Accordingly, we examined the response of different types of APCs to c-di-AMP. We showed that treatment with c-di-AMP induces the up-regulation of the expression of MHC class II as well as T cell co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of both murine and human DCs and MΦs in vitro (Figures 2, 3B and 5A). These in vitro findings were further confirmed by ex vivo studies in which murine DCs and MΦs were analyzed after i. n. c-di-AMP application (Figure 3A). 24 h after i. n. administration especially DCs and not so much MΦs were activated by c-di-AMP in the lymphoid compartments. Although early DC antigen presenting activity in the draining CLN was described for i. n. immunization experiments with viral antigens [28], our adjuvant candidate c-di-AMP alone did not notably induce T cell stimulatory molecules on APCs of the CLN after 24 h. The more pronounced DC activation was observed in the NALT, the lymphoid tissue directly associated with the site of administration, and also in the MLN. The early DC response in the MLN is in line with several studies reporting a similar observation upon i. n. immunization with model antigens and adjuvants [29]–[31] as well as upon i. n. infection with influenza virus [32]. We also demonstrated that murine DCs and MΦs/monocytes/granulocytes respond to in vivo administration of c-di-AMP by the up-regulation of IFN-β expression (Figure 4A).

Taken together, we observed the effects of c-di-AMP on its target cells on two different aspects of immune regulation. First, we found up-regulation of CD80 and CD86 on the surface of mouse and human DC subsets treated with c-di-AMP (Figures 3B and 5A). These molecules are known to interact with CD28 on the T cell surface to deliver co-stimulatory signals after TCR engagement with the antigen presenting MHC molecule. This co-stimulation represents an important regulator of T cell immune tolerance toward activation in response to pathogenic invasion, for example by promoting T cell proliferation and differentiation. Nevertheless, both CD80 and CD86 are also ligands for the T cell surface molecule CTLA-4 which facilitates negative T cell activation signaling. As opposed to the constitutively surface-expressed CD28, CTLA-4 is only transported to the surface upon TCR-mediated activation. It is believed to have a role in the prevention of an overshooting T cell proliferation to control antigen-specific T cell-mediated immune responses. In an effort to find the major c-di-AMP target DC subset we identified conventional DCs as the principal responders (Figures 3B and 5A). This points to an adjuvant mechanism in which c-di-AMP facilitates T cell activation by CD80 and CD86-mediated co-stimulation through the classical APC type that mainly functions in naïve T cell activation. In conjunction with an antigen in a subunit vaccine, c-di-AMP would provide the means to overcome cellular immune tolerance as a first step to an adaptive response that eventually leads to the establishment of specific memory cells.

Second, we showed that IFN-β production, a downstream indicator of PRR signaling pathway activation, was induced in vivo in DCs as well as in the MΦ/monocyte/granulocyte population but not in B or T cells (Figure 4). It has been reported that murine MΦs respond to c-di-AMP secreted by Listeria monocytogenes with the production of IFN-β [17], [33]. Our data generated with a reporter mouse system confirm MΦs as candidate c-di-AMP responders and extend these findings to DCs as major contributors to the IFN-β response to c-di-AMP in vivo. Our results would also fit in line with the Tip-DC IFN-β response reported for murine listeriosis, if the reported IFN-β gene induction were mediated by Listeria-released c-di-AMP [34], [35]. The observed IFN-β reporter response was locally restricted to nasal tissue regions (Figure 4A). This largely excludes CD11c-positive MΦs as contributors to the response of the CD11c specific reporter signal, because such MΦs are lung (alveolae)-associated [36]. This is in contrast to what was observed with other immune stimulators (e.g. poly I:C) for which the luciferase signal also occurred in the liver or the spleen [37]. The locally restricted effect of i. n. applied c-di-AMP could be of advantage in order to reduce the potential risk for toxic side effects at the systemic level.

Our results suggest that c-di-AMP acts on the level of PRR signaling pathways in innate immune cells. This is supported by reports describing c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP as activators of IFN-β production via a pathway that involves the adaptor/sensor STING, TBK-1 and IRF3 [13], [15], [20]–[22]. In addition it was reported that c-di-GMP induces the production of TNF-α via a STING-dependent but IFN type I independent pathway [38]. Several immune effects of IFN-β are described [25], [39]. The up-regulation of cytokines, chemokines and intermediate signaling molecules can modulate immune cell activity. The specific effect of IFN-β correlates with cell state, timing, amount and the molecular context of its encounter. IFN-β can differentially modulate signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling in monocytes, T cells, and B cells to affect their transcriptional, differentiation, proliferative, apoptotic, and pro-inflammatory activity. It is known that type I IFNs can regulate effector T cell function and differentiation of TH1, TH2, TH17 and Treg cells [25], [26], [39]. Hence, it is conceivable that the IFN-β-inducing effect of c-di-AMP contributes, at least in part, to the reported proliferation of antigen-specific T cell types and the evolvement of the proposed balanced TH1/TH2/TH17 cell response [18]. DC subset targeting was investigated also with regard to the c-di-AMP-induced IFN-β production. Conventional DCs showed a much more pronounced IFN-β production than plasmacytoid DCs (Figures 4B and 5B). This finding was somewhat surprising because plasmacytoid DCs are known to be specialized in IFN type I production and usually produce these IFNs in much higher amounts than conventional DCs, which are specialized in antigen presentation. By targeting conventional DCs, c-di-AMP evokes the secretion of a rather limited amount of IFN-β which may be important to fine tune immune responses. Interestingly, also the IFN-β response to L. monocytogenes was reported not to be mediated by plasmacytoid DCs either [34], [35]. Since it is known that the bacterium secretes c-di-AMP in the course of infection [17], [33], our results further strengthen the suggestion that c-di-AMP is indeed the mediator of the L. monocytogenes-induced IFN-β.

The modes of action described here do not exclude additional, not yet identified mechanisms of c-di-AMP-mediated immune response modulation. For example, other co-stimulatory molecules or secreted immune signaling molecules could be regulated in a c-di-AMP-dependent manner to enhance or modulate antigen-induced immune responses by acting on either effector or bystander cells. However, our results further elucidate intermediate steps of the immune response cascade leading to the immune modulatory activity of c-di-AMP observed in immunization studies on mice [18]. They advance the knowledge on modes of adjuvant action toward the regulation of effective immunization responses.

Materials and Methods

Mice/Ethics statement

Female BALB/c (H-2d) or C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice 6–8 weeks old were purchased from Harlan (Rossdorf, Germany). The generation of the global and tissue specific IFN-β reporter mice has been previously described [34], [40]. They were bred at the animal facilities of the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research under specific pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments in this study have been performed in agreement with the local government of Lower Saxony, Germany (No. 33.11.42502-04-017/08). Animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups.

Synthesis of c-di-AMP

C-di AMP was prepared as previously described [18]. Briefly, c-di-AMP was synthesized by cyclization and purified by Reversed Phase HPLC. The chemical structure was confirmed by 1H- and 13P-nuclear magnetic resonance and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. For the use in experiments, lyophilized c-di-AMP was dissolved in water. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contamination was ruled out by employing the HEK-Blue LPS Detection Kit (InvivoGen, San Diego, California, USA).

Preparation of murine bone marrow-derived cells

The femur and tibia from two 6-8 week old C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice (Harlan, Rossdorf, Germany) per experiment were flushed with medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 µg/ml gentamycin; Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA) to collect bone marrow cells. Erythrocytes were lysed in 150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), pH 7.2. The remaining bone marrow cells were seeded at 106 cells/ml in medium supplemented with either 5 ng/ml murine GM-CSF (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) and cultured for 7 days or with 100 ng/ml murine Flt3l (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) and cultured for 9 days or with 10 ng/ml murine M-CSF (eBioscience Inc., San Diego, California, USA) and cultured for 7 days at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. The bone marrow-derived cells cultured in the presence of GM-CSF give rise to non-adherent in vitro conventional DC model populations, positive for the marker CD11c. Flt3l promotes the differentiation into a mixed population of in vitro model conventional DCs and plasmacytoid DCs, both positive for CD11c with the plasmacytoid DCs being additionally positive for B220, while the in vitro model MΦs cultured in the presence of M-CSF are positive for CD11b [41]-[43].

Preparation of cells from the murine NALT, CLN and MLN

To isolate APCs from the NALT, cells were scratched from the nasal cavity of five animals per group. The combined cells were transferred to medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 µg/ml gentamycin; Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA), pressed through a 100 µm pore nylon mesh, and erythrocytes were lysed in 150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), pH 7.2. To isolate APCs from the CLN or the MLN, lymph nodes were also transferred to medium (see above), pressed through a 100 µm pore nylon mesh and washed.

In vitro stimulation of cells

The culture medium of cells was supplemented with 1, 5 or 60 µg/ml c-di-AMP or 0.1 or 1 µg/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) or 10 µg/ml CpG (InvivoGen, San Diego, California, USA) or left without additive. Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere and were then analyzed.

T cell proliferation assay

Spleens were isolated from mice, transferred to medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 µg/ml gentamycin; Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA), and gently pressed through a 100 µm cell mesh. Erythrocytes were lysed in 150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.2) and cells were washed. T cells were decorated with fluorescently labeled antibodies against CD44, CD62L, CD25, CD4, and CD8 (see below) and sorted for CD44low, CD62Lhigh, CD25−, CD4+ or CD44low, CD62Lhigh, CD25−, CD8+ cell populations, respectively. Cells were incubated at 37°C and with 5% CO2 for 4 days in the presence of either 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP, 5 µg/ml concanavalin A (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) or left untreated. Cells were then incubated for another 16 h in the presence of 10 µCi/ml 3H-thymidine. Incorporated 3H-thymidine was measured by a γ scintillation counter (1450 Microbeta Trilux, Wallach Sverige, Upplands Vasby, Sweden).

In vivo stimulation in mice (i. n. c-di-AMP application)

Female 6–8 week old C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice (Harlan, Rossdorf, Germany) were anesthetized with Isoflurane (Abbott Animal Health, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) and treated i. n. (10 µl per nostril) with 5 µg per dose of c-di-AMP in Ampuwa (Serumwerk, Bernburg, Germany) or with Ampuwa alone in the control group. 24 h after the i. n. application mice were sacrificed and tissue/cells were collected from five animals per group.

Preparation of human DCs from PBMCs

Human DCs were prepared from the blood of healthy human donors who provided informed consent. The blood donors' health is rigorously checked before being admitted for blood donation. This process includes a national standardized questionnaire with health questions, an interview with a medical doctor and standardized laboratory tests for HIV1/2, HBV, HCV and syphilis infections and hematological cell counts. The blood donations were obtained from the Institute for Clinical Transfusion Medicine, Klinikum Braunschweig, Germany, in accordance with the rules of the regional Ethics Committee of Lower Saxony, Germany, and the declaration of Helsinki and were analyzed anonymously. PBMCs were isolated by centrifugation over a Ficoll (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) cushion and myeloid and plasmacytoid DCs were prepared by negative selection using the Myeloid DC Isolation Kit, human, and the Plasmacytoid DC Isolation Kit II, human, (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), respectively. Isolated cells were recovered overnight in medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin; Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA) at 37°C and with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

Flow cytometric analysis of immune cell markers

After stimulation cells were pre-incubated with Fc receptor blocking anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (clone 93) or human Fc receptor binding inhibitor (eBioscience Inc., San Diego, California, USA), and decorated with select fluorophore-conjugated antibodies out of the following: CD80 (clone 16-10A1, APC-conjugated), CD11b (clone M1/70, eFluor450-conjugated), CD8 (clone 53-6.7, APC-conjugated), CD44 (clone IM7, Pacific Blue-conjugated), CD4 (clone RM4-5, PE-Cy7-conjugated) (eBioscience Inc., San Diego, California, USA) or anti-mouse CD86 (clone GL1, Brilliant Violet 605-conjugated), CD11c (clone N418, PE-Cy7-conjugated), anti-human CD80 (clone 2D10, Brilliant Violet 650-conjugated), CD83 (clone HB15e, PE-conjugated), CD86 (clone IT2.2, Brilliant Violet 605-conjugated) (BioLegend, San Diego, California, USA) or anti-mouse CD86 (clone GL1, PE-conjugated), I-Ab (clone AF6-120.1, FITC-conjugated), B220 (clone RA3-6B2, PE-conjugated), CD62L (clone MEL-14, FITC-conjugated), CD25 (clone PC61, PE-conjugated) (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). Human plasmacytoid DCs were identified by the marker CD303 (using PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-human CD303a, clone 201A; eBioscience Inc., San Diego, California, USA), myeloid DCs by the marker CD11c (using Brilliant Violet 711-conjugated anti-human CD11c, clone 3.9; BioLegend, San Diego, California, USA) [44], [45]. A blue fluorescent amine-reactive dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California,USA; L23105) was routinely used as live/dead cell marker in flow cytometric analyses. FACS analysis was performed using an LSR-II and with FACSDiva software (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) and the evaluation software FlowJo Mac v9.6 (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, Oregon, USA).

IFN-β reporter mouse assay

To study the effect of c-di-AMP on the induction of IFN-β genes C57BL/6 IFN-ββ-luc reporter mice (see also paragraph “Mice”, above) were used. The conditional reporter mice received c-di-AMP by the i. n. route at a concentration of 5 µg per mouse. IFN-β gene induction was analyzed by measuring luciferase activity as a reporter by in vivo imaging. To this end, mice were injected intravenously with 150 mg/kg of D-luciferin firefly (Synchem, Felsberg/Altenburg, Germany) dissolved in PBS at time points 0, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h after administration of c-di-AMP. Mice were anesthetized with Isofluran (Curamed, Karlsruhe, Germany) and monitored using the IVIS 200 imaging system (CaliperLS, Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Photon flux was quantified with the LivingImage 3.2 Software (CaliperLS, Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and is expressed in photons/s/cm2/steradian.

IFN-β detection in cell culture medium

Murine IFN-β was analyzed using the Legend Max Mouse IFN-β ELISA kit with pre-coated plates (BioLegend, San Diego, California, USA); human IFN-β was analyzed using the VeriKine human IFN-β ELISA kit (PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). Detection was performed by light absorbance measurement at a wavelength of 450 nm using a Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont, USA).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by applying the unpaired t-test; n.s. indicates not significant; *** indicates p<0.001; ** indicates p<0.01; and * indicates p<0.05.

Supporting Information

C-di AMP-stimulated murine DCs and MΦs respond with the up-regulation of CD80, CD86 and MHC class II. BMDCs or MΦs were incubated for 24 h in the presence of 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP or without additive (untreated control). Cells were decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for CD80, CD86 and MHC class II, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The TLR ligand LPS was used as control stimulator to assess if the cells were generally activatable. Histograms of flow cytometry measurements represent a single experiment. The data collected from multiple experiments are summarized in figure 2. The x axis displays fluorescence intensity (at a logarithmic scale) that was recorded with fluorescent antibodies against the indicated molecules CD80, CD86 or MHC class II. The signals derive from living singlet cells and are selected by gating based on forward/sideward scatter (for singlet cell identification) and fluorescent live/dead marker (low intensity on live cells) and fluorescent antibody (high intensity) analysis.

(TIF)

C-di-AMP up-regulates T cell co-stimulatory molecules preferentially on conventional murine dendritic cells (DCs). (A) 24 h after i. n. application of c-di-AMP in mice DCs and macrophages (MΦs) were isolated from nose-associated tissue (NALT), cervical lymph nodes (CLN) or mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) and decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for the identification markers of DCs (CD11c+) or MΦs (CD11b+, CD11c−), and for CD80, CD86, MHC class II and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Bone marrow derived in vitro model DCs were grown in the presence of Flt3l and stimulated for 24 h in the presence of 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP. They were decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for the identification markers CD11c (DCs), CD11b (conventional DCs, cDCs), B220 (plasmacytoid DCs, pDCs), CD80 and CD86, then analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms of flow cytometry measurements represent a single experiment. The data collected from multiple experiments are summarized in figure 3. The x axis displays fluorescence intensity (on a logarithmic scale) that was recorded with fluorescent antibodies against the indicated molecules CD80, CD86 or MHC class II. The signals are derived from living singlet cells positive for the indicated identification marker and are selected by gating based on forward/sideward scatter (for singlet cell identification) and fluorescent live/dead marker (low intensity on live cells) and fluorescent antibody (high intensity) analysis.

(TIF)

C-di-AMP stimulated human myeloid (conventional) DCs (mDCs) but not plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) respond with the up-regulation of surface CD80, CD83 and CD86. PBMC-derived human pDCs or mDCs were incubated for 24 h in the presence of 60 µg/ml c-di-AMP or without additive (untreated control). Cells were decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for the identification markers CD11c (mDC), CD303 (pDC) and CD80, CD83, CD86 and analyzed by flow cytometry. The TLR ligands LPS (for mDCs) and CpG (for pDCs) were used as control stimulators to if the cells were generally activatable. Histograms of flow cytometry measurements represent a single experiment with the DC subsets originating from one and the same donor. The data collected from multiple donors are summarized in figure 5a. The x axis displays fluorescence intensity (at a logarithmic scale) that was recorded with fluorescent antibodies against the indicated molecules CD80, CD83 or CD86. The signals derive from living singlet cells positive for the DC subset identification marker and are selected by gating based on forward/sideward scatter (for singlet cell identification) and fluorescent live/dead marker (low intensity on live cells) and fluorescent antibody (high intensity) analysis.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Sebastian Weissmann and Dr. Blair Prochnow for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by grants from the EU (PANFLUVAC); BMBF in the context of the programs Gerontosys 2 (Gerontoshield), EuroNanoMed (HCVAX) and ERANetRUS (HCRUS), and the Helmholtz Association (IG-SCID). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Libanova R, Becker PD, Guzman CA (2012) Cyclic di-nucleotides: new era for small molecules as adjuvants. Microb Biotechnol 5: 168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen ZH, Schaap P (2012) The prokaryote messenger c-di-GMP triggers stalk cell differentiation in Dictyostelium. Nature 488: 680–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corrigan RM, Abbott JC, Burhenne H, Kaever V, Grundling A (2011) c-di-AMP is a new second messenger in Staphylococcus aureus with a role in controlling cell size and envelope stress. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meissner A, Wild V, Simm R, Rohde M, Erck C, et al. (2007) Pseudomonas aeruginosa cupA-encoded fimbriae expression is regulated by a GGDEF and EAL domain-dependent modulation of the intracellular level of cyclic diguanylate. Environ Microbiol 9: 2475–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Wexselblatt E, Katzhendler J, Yavin E, Ben-Yehuda S (2011) c-di-AMP reports DNA integrity during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO Rep 12: 594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ablasser A, Goldeck M, Cavlar T, Deimling T, Witte G, et al. (2013) cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 498: 380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diner EJ, Burdette DL, Wilson SC, Monroe KM, Kellenberger CA, et al. (2013) The innate immune DNA sensor cGAS produces a noncanonical cyclic dinucleotide that activates human STING. Cell Rep 3: 1355–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ (2013) Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 339: 786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu J, Sun L, Chen X, Du F, Shi H, et al. (2013) Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science 339: 826–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hu DL, Narita K, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Nakane A, et al. (2009) c-di-GMP as a vaccine adjuvant enhances protection against systemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. Vaccine 27: 4867–4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karaolis DK, Means TK, Yang D, Takahashi M, Yoshimura T, et al. (2007) Bacterial c-di-GMP is an immunostimulatory molecule. J Immunol 178: 2171–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karaolis DK, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, et al. (2007) Cyclic di-GMP stimulates protective innate immunity in bacterial pneumonia. Infect Immun 75: 4942–4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McWhirter SM, Barbalat R, Monroe KM, Fontana MF, Hyodo M, et al. (2009) A host type I interferon response is induced by cytosolic sensing of the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP. J Exp Med 206: 1899–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ogunniyi AD, Paton JC, Kirby AC, McCullers JA, Cook J, et al. (2008) c-di-GMP is an effective immunomodulator and vaccine adjuvant against pneumococcal infection. Vaccine 26: 4676–4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sauer JD, Sotelo-Troha K, von Moltke J, Monroe KM, Rae CS, et al. (2011) The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect Immun 79: 688–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vremec D, Pooley J, Hochrein H, Wu L, Shortman K (2000) CD4 and CD8 expression by dendritic cell subtypes in mouse thymus and spleen. J Immunol 164: 2978–2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA (2010) c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science 328: 1703–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ebensen T, Libanova R, Schulze K, Yevsa T, Morr M, et al. (2011) Bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric adenosine monophosphate: strong Th1/Th2/Th17 promoting mucosal adjuvant. Vaccine 29: 5210–5220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Libanova R, Ebensen T, Schulze K, Bruhn D, Norder M, et al. (2010) The member of the cyclic di-nucleotide family bis-(3′, 5′)-cyclic dimeric inosine monophosphate exerts potent activity as mucosal adjuvant. Vaccine 28: 2249–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, et al. (2011) STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature 478: 515–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ouyang S, Song X, Wang Y, Ru H, Shaw N, et al. (2012) Structural analysis of the STING adaptor protein reveals a hydrophobic dimer interface and mode of cyclic di-GMP binding. Immunity 36: 1073–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parvatiyar K, Zhang Z, Teles RM, Ouyang S, Jiang Y, et al. (2012) The helicase DDX41 recognizes the bacterial secondary messengers cyclic di-GMP and cyclic di-AMP to activate a type I interferon immune response. Nat Immunol 13: 1155–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Olive C (2012) Pattern recognition receptors: sentinels in innate immunity and targets of new vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines 11: 237–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schenten D, Medzhitov R (2011) The control of adaptive immune responses by the innate immune system. Adv Immunol 109: 87–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tough DF (2012) Modulation of T-cell function by type I interferon. Immunol Cell Biol 90: 492–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rueckert C, Guzman CA (2012) Vaccines: from empirical development to rational design. PLoS Pathog 8: e1003001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wegmann F, Gartlan KH, Harandi AM, Brinckmann SA, Coccia M, et al. (2012) Polyethyleneimine is a potent mucosal adjuvant for viral glycoprotein antigens. Nat Biotechnol 30: 883–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ciabattini A, Pettini E, Fiorino F, Prota G, Pozzi G, et al. (2011) Distribution of primed T cells and antigen-loaded antigen presenting cells following intranasal immunization in mice. PLoS One 6: e19346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ko SY, Lee KA, Youn HJ, Kim YJ, Ko HJ, et al. (2007) Mediastinal lymph node CD8alpha- DC initiate antigen presentation following intranasal coadministration of alpha-GalCer. Eur J Immunol 37: 2127–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vendetti S, Riccomi A, Negri DR, Veglia F, Sciaraffia E, et al. (2009) Development of antigen-specific T cells in mediastinal lymph nodes after intranasal immunization. Methods 49: 334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. GeurtsvanKessel CH, Willart MA, van Rijt LS, Muskens F, Kool M, et al. (2008) Clearance of influenza virus from the lung depends on migratory langerin+CD11b- but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med 205: 1621–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamamoto T, Hara H, Tsuchiya K, Sakai S, Fang R, et al. (2012) Listeria monocytogenes strain-specific impairment of the TetR regulator underlies the drastic increase in cyclic di-AMP secretion and beta interferon-inducing ability. Infect Immun 80: 2323–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Solodova E, Jablonska J, Weiss S, Lienenklaus S (2011) Production of IFN-beta during Listeria monocytogenes infection is restricted to monocyte/macrophage lineage. PLoS One 6: e18543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dresing P, Borkens S, Kocur M, Kropp S, Scheu S (2010) A fluorescence reporter model defines “Tip-DCs” as the cellular source of interferon beta in murine listeriosis. PLoS One 5: e15567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guth AM, Janssen WJ, Bosio CM, Crouch EC, Henson PM, et al. (2009) Lung environment determines unique phenotype of alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L936–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pulverer JE, Rand U, Lienenklaus S, Kugel D, Zietara N, et al. (2010) Temporal and spatial resolution of type I and III interferon responses in vivo. J Virol 84: 8626–8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blaauboer SM, Gabrielle VD, Jin L (2014) MPYS/STING-mediated TNF-alpha, not type I IFN, is essential for the mucosal adjuvant activity of (3′-5′)-cyclic-di-guanosine-monophosphate in vivo. J Immunol 192: 492–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Levy DE, Marie IJ, Durbin JE (2011) Induction and function of type I and III interferon in response to viral infection. Curr Opin Virol 1: 476–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lienenklaus S, Cornitescu M, Zietara N, Lyszkiewicz M, Gekara N, et al. (2009) Novel reporter mouse reveals constitutive and inflammatory expression of IFN-beta in vivo. J Immunol 183: 3229–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, et al. (1999) An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods 223: 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Naik SH, Proietto AI, Wilson NS, Dakic A, Schnorrer P, et al. (2005) Cutting edge: generation of splenic CD8+ and CD8- dendritic cell equivalents in Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand bone marrow cultures. J Immunol 174: 6592–6597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weischenfeldt J, Porse B (2008) Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMM): Isolation and Applications. CSH Protoc 2008: pdb prot5080. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44. Kassianos AJ, Jongbloed SL, Hart DN, Radford KJ (2010) Isolation of human blood DC subtypes. Methods Mol Biol 595: 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. MacDonald KP, Munster DJ, Clark GJ, Dzionek A, Schmitz J, et al. (2002) Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood 100: 4512–4520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

C-di AMP-stimulated murine DCs and MΦs respond with the up-regulation of CD80, CD86 and MHC class II. BMDCs or MΦs were incubated for 24 h in the presence of 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP or without additive (untreated control). Cells were decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for CD80, CD86 and MHC class II, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The TLR ligand LPS was used as control stimulator to assess if the cells were generally activatable. Histograms of flow cytometry measurements represent a single experiment. The data collected from multiple experiments are summarized in figure 2. The x axis displays fluorescence intensity (at a logarithmic scale) that was recorded with fluorescent antibodies against the indicated molecules CD80, CD86 or MHC class II. The signals derive from living singlet cells and are selected by gating based on forward/sideward scatter (for singlet cell identification) and fluorescent live/dead marker (low intensity on live cells) and fluorescent antibody (high intensity) analysis.

(TIF)

C-di-AMP up-regulates T cell co-stimulatory molecules preferentially on conventional murine dendritic cells (DCs). (A) 24 h after i. n. application of c-di-AMP in mice DCs and macrophages (MΦs) were isolated from nose-associated tissue (NALT), cervical lymph nodes (CLN) or mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) and decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for the identification markers of DCs (CD11c+) or MΦs (CD11b+, CD11c−), and for CD80, CD86, MHC class II and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Bone marrow derived in vitro model DCs were grown in the presence of Flt3l and stimulated for 24 h in the presence of 5 µg/ml c-di-AMP. They were decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for the identification markers CD11c (DCs), CD11b (conventional DCs, cDCs), B220 (plasmacytoid DCs, pDCs), CD80 and CD86, then analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms of flow cytometry measurements represent a single experiment. The data collected from multiple experiments are summarized in figure 3. The x axis displays fluorescence intensity (on a logarithmic scale) that was recorded with fluorescent antibodies against the indicated molecules CD80, CD86 or MHC class II. The signals are derived from living singlet cells positive for the indicated identification marker and are selected by gating based on forward/sideward scatter (for singlet cell identification) and fluorescent live/dead marker (low intensity on live cells) and fluorescent antibody (high intensity) analysis.

(TIF)

C-di-AMP stimulated human myeloid (conventional) DCs (mDCs) but not plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) respond with the up-regulation of surface CD80, CD83 and CD86. PBMC-derived human pDCs or mDCs were incubated for 24 h in the presence of 60 µg/ml c-di-AMP or without additive (untreated control). Cells were decorated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for the identification markers CD11c (mDC), CD303 (pDC) and CD80, CD83, CD86 and analyzed by flow cytometry. The TLR ligands LPS (for mDCs) and CpG (for pDCs) were used as control stimulators to if the cells were generally activatable. Histograms of flow cytometry measurements represent a single experiment with the DC subsets originating from one and the same donor. The data collected from multiple donors are summarized in figure 5a. The x axis displays fluorescence intensity (at a logarithmic scale) that was recorded with fluorescent antibodies against the indicated molecules CD80, CD83 or CD86. The signals derive from living singlet cells positive for the DC subset identification marker and are selected by gating based on forward/sideward scatter (for singlet cell identification) and fluorescent live/dead marker (low intensity on live cells) and fluorescent antibody (high intensity) analysis.

(TIF)