Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is an adult onset neurodegenerative disease that causes progressive paralysis and death due to degeneration of motoneurons in spinal cord, brainstem and motor cortex. Nowadays, there is no effective therapy and patients die 2–5 years after diagnosis. Resveratrol (trans-3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene) is a natural polyphenol found in grapes, with promising neuroprotective effects since it induces expression and activation of several neuroprotective pathways involving Sirtuin1 and AMPK. The objective of this work was to assess the effect of resveratrol administration on SOD1G93A ALS mice. We determined the onset of symptoms by rotarod test and evaluated upper and lower motoneuron function using electrophysiological tests. We assessed the survival of the animals and determined the number of spinal motoneurons. Finally, we further investigated resveratrol mechanism of action by means of western blot and immunohistochemical analysis. Resveratrol treatment from 8 weeks of age significantly delayed disease onset and preserved lower and upper motoneuron function in female and male animals. Moreover, resveratrol significantly extended SOD1G93A mice lifespan and promoted survival of spinal motoneurons. Delayed resveratrol administration from 12 weeks of age also improved spinal motoneuron function preservation and survival. Further experiments revealed that resveratrol protective effects were associated with increased expression and activation of Sirtuin 1 and AMPK in the ventral spinal cord. Both mediators promoted normalization of the autophagic flux and, more importantly, increased mitochondrial biogenesis in the SOD1G93A spinal cord. Taken together, our findings suggest that resveratrol may represent a promising therapy for ALS.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13311-013-0253-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Motoneuron disease, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Resveratrol, Sirtuin 1, AMPK, SOD1G93A mice

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by the death of upper and lower motoneurons (MN) that clinically manifests by progressive muscle atrophy and paralysis [1]. Although the majority of ALS cases are sporadic with unknown etiology, 10 % of them are inherited forms, caused by genetic mutations. Among these, mutations in the gene encoding for the enzyme Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) are observed in about 20 % of the patients [2]. The study of these genetic mutations led to the development of several transgenic animal models of ALS. The most widely used is a transgenic mouse that over-expresses the human mutated form of the SOD1 gene with a glycine to alanine conversion at the 93rd codon [3]. This model recapitulates most relevant clinical and histopathological features of both familial and sporadic forms of the human disease [3]. It is also of relevance that alterations of the SOD1 protein have been reported in sporadic ALS patients [4], increasing the interest of this murine model. Several mechanisms have been implicated as contributors to MN death in ALS, such as glutamate excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, protein misfolding, mitochondrial defects, impaired axonal transport, and inflammation [5, 6]. Nevertheless, positive experimental results targeting some of these abnormalities have failed to translate into successful human trials [7, 8].

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene), a polyphenol found in grapes and red wine, has been reported to exert age-delaying and neuroprotective effects [9, 10]. Despite these well-documented beneficial effects, the mechanisms of action of resveratrol remain controversial. However, it has been recently described that resveratrol can trigger a cascade of intracellular events that converge on Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and PGC-1α, as important energy-sensing regulators [11, 12]. Sirt1 is a NAD+-dependent deacetylase that has emerged as an important element of the cellular metabolic network. Its activation has been shown to protect against neurodegeneration in several neurodegenerative disorders [13]. In fact, Sirt1 may promote neuroprotection by the modulation of several cellular pathways, such as autophagy [14, 15] and mitochondrial biogenesis [16]. On the other hand, it is also accepted that resveratrol benefits may be mediated through AMPK activation [16, 17]. It has been proposed that resveratrol works primarily by activating AMPK, which then activates Sirt1 indirectly by elevating intracellular levels of its cosubstrate NAD+[18, 19]. Alternatively, resveratrol may first activate Sirt1, leading to AMPK activation via deacetylation and activation of the AMPK kinase LKB1 [20, 21].

Resveratrol administration has been shown to provide beneficial effects on several neurodegenerative disease models, such as Alzheimer’s disease [10] and Parkinson’s disease [22] and in traumatic [23] and ischemic injuries to the central nervous system [24]. Since previous studies showed that resveratrol administration protects MN on in vitro ALS models [25, 26], the main goal of the present work was to assess the potential therapeutic effect of a resveratrol-enriched diet in the SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS.

Material and Methods

Transgenic Mice and Drug Administration

Transgenic mice with the G93A human SOD1 mutation (B6SJL-Tg[SOD1-G93A]1Gur) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained at the Animal Service of the Universidad de Zaragoza. Hemizygotes B6SJL SOD1G93A males were obtained by crossing with B6SJL females from the CBATEG (Bellaterra, Spain). The offspring was identified by PCR amplification of DNA extracted from the tail tissue. Mice were kept in standard conditions of temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and a 12:12 light:dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, where the animal experiments were performed.

Animals were evaluated at 8 weeks (prior to starting resveratrol administration) by rotarod and electrophysiological tests to obtain baseline values. Animals were distributed, according to their progenitors, weight and electrophysiological baseline values, in balanced experimental groups. All functional and survival assessments were performed by researchers blinded with respect to the group treatment. A resveratrol-enriched diet [10] was given to the groups of treated mice from 8 weeks of age and from 12 weeks of age for the delayed treatment group. Assuming a normal food intake of 4 g/animal/day, resveratrol was given at a daily dose of 160 mg/kg. The control groups received a standard diet, with no differences in manipulations during the study. The experimental groups included in the study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental groups included in the study.

| Experimental group | Gender | n | Treatment onset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Females | 10 | – |

| SOD1 untreated | Females | 20 | – |

| SOD1 + Resveratrol | Females | 23 | 8 weeks |

| Wild type | Males | 10 | – |

| SOD1 untreated | Males | 16 | – |

| SOD1 + Resveratrol | Males | 22 | 8 weeks |

| SOD1 untreated | Females | 8 | – |

| SOD1 + Resveratrol | Females | 8 | 12 weeks |

| SOD1 untreated | Males | 8 | – |

| SOD1 + Resveratrol | Males | 8 | 12 weeks |

Nerve Conduction Tests

Motor nerve conduction tests were performed at 8 weeks of age and then every two weeks until 16 weeks in all the animals used in the study. The sciatic nerve was stimulated percutaneously by means of single pulses of 0.02 ms duration (Grass S88) delivered through a pair of needle electrodes placed at the sciatic notch. The compound muscle action potential (CMAP, M wave) was recorded from the tibialis anterior (TA) and the plantar (interossei) muscles with microneedle electrodes [27, 28]. For evaluation of the motor central pathways, motor evoked potentials (MEP) were recorded from the TA and plantar muscles in response to transcranial electrical stimulation of the motor cortex by single rectangular pulses of 0.1 ms duration, delivered through needle electrodes inserted subcutaneously, the cathode over the skull overlaying the sensorimotor cortex and the anode at the nose [27, 29]. All potentials were amplified and displayed on a digital oscilloscope (Tektronix 450S) at settings appropriate to measure the amplitude from baseline to the maximal negative peak. To ensure reproducibility, the recording needles were placed under microscope to secure the same placement on all animals guided by anatomical landmarks. During the tests, the mice body temperature was kept constant by means of a thermostated heating pad.

Locomotion Tests

The rotarod test was performed to evaluate motor coordination, strength and balance [30, 31] in all the animals used in the study (Table 1). Mice were trained three times a week on the rod rotating at 14 rpm, and then tested from 8 to 16 weeks of age, with an arbitrary maximum time of maintenance in the rotating rod of 180 seconds. Clinical disease onset was defined as the first day when an animal was not able to complete the 180 seconds on the rotating rod.

The DigiGait system (Mouse Specifics, Boston, MA) was used to assess the locomotor performance of the animals at the end stage of the disease (16 weeks of age). The animals were placed over the treadmill belt and their capacity to run with increasing treadmill velocity was recorded. Treadmill speeds used were 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 cm/s, based on previous studies performed in our laboratory [32, 33].

Survival

For survival assessment, 23 female (10 untreated and 13 resveratrol administered) and 20 male (10 untreated and 10 resveratrol administered) SOD1G93A mice were used. It was considered that animals reached the end point of the disease when they were unable to right themselves in 30s when placed on their side.

Histology

At 16 weeks of age, 4–5 mice from each group were transcardially perfused with 4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS and the lumbar segment of the spinal cord was harvested, post-fixed for 24 h, and cryopreserved in 30 % sucrose. Transverse 40-μm thick sections were serially cut with a cryotome (Leica) between L2–L5 segmental levels. For each segment, each section of a series of ten was collected sequentially on separate gelatin-coated slides or free-floating in Olmos medium.

One slide of each animal was rehydrated for 1 min and stained for 2 h with an acidified solution of 3.1 mM cresyl violet. Then, the slides were washed in distilled water for 1 min, dehydrated and mounted with DPX (Fluka). MNs were identified by their localization in the ventral horn of the spinal cord sections and counted following strict size and morphological criteria; only MNs with diameters larger than 20 μm, polygonal shape and prominent nucleoli were counted. The number of MNs present in both ventral horns was counted in four serial sections of each L4 and L5 segments [27, 34].

Another series of sections was blocked with PBS-Triton-FBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies anti-glial fibrilary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:1000, Dako), rabbit anti-ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1, 1:1000, Wako), or anti-sirtuin 1 (Sirt1, 1:200, Abcam). After several washes, sections were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with Alexa 488 or Alexa 594-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Life Science), or, for anti-Sirt antibody, with biotinilated secondary antibody (1:200, Vector) and then for 1 hour with Alexa 594-conjugated streptavidin (1:1000, Vector). For co-localizations, spinal MNs were labeled with 435/455-Neurotrace fluorescent Nissl staining (1:200, Life Science). To quantify astroglial and microglial immunoreactivity, microphotographs of the ventral horn grey matter were taken at×400 and, after defining the threshold for background correction, the integrated density of GFAP or Iba1 labeling was measured using ImageJ software [33]. The integrated density represents the area above the threshold for the mean density minus the background.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot

For protein extraction, another subset of mice (4–5 from each experimental group) were anesthetized and decapitated at 16 weeks of age. The lumbar spinal cord was removed and divided into quarters to isolate the ventral quadrants. One of them was prepared for protein extraction and homogenized in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 % Triton X-100, 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate, 0.2 % SDS, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) adding 10 μl/ml of Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and PhosphoSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After clearance, protein concentration was measured by Lowry assay (Bio-Rad Dc protein assay).

To perform western blots, 20 μg of protein of each sample were loaded in SDS-poliacrylamide gels. The transfer buffer was 25 mM trizma-base, 192 mM glycine, 20 % (v/v) methanol, pH 8.4. The membranes were blocked with 5 % BSA in PBS plus 0.1 % Tween-20 for 1 hour, and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibodies used were: anti-b-actin (Sigma; 1:10000), anti-GAPDH (Millipore, 1:20000), anti-Sirt1 (Abcam, 1:1000), anti-p53 (Abcam, 1:500), anti-acetyl p53 (L382) (Millipore, 1:500), anti-AMPK (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), anti-pAMPK (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), anti-LC3b (Abcam, 1:200), anti-Beclin 1 (Cell signaling, 1:1000), anti-Fis-1 (ThermoScientific, 1:1000), anti mitofusin 2 (Sigma, 1:1000), anti-porin, (Abcam, 1:1000), anti-complex I subunit 39 kDa (Invitrogen, 1:1000), anti-complex II Fp subunit (Invitrogen, 1:1000), anti-complex III subunit Core 2 (Invitrogen, 1:1000), anti-complex IV subunit I (Invitrogen, 1:1000), and anti-complex V subunit α (Molecular Probes, 1:1000). Horseradish peroxidase–coupled secondary antibody (1:5000, Vector) incubation was performed for 60 min at room temperature. The membranes were visualized using enhanced chemiluminiscence method and the images were collected and analyzed with Gene Genome apparatus and Gene Snap and Gene Tolls software (Syngene, Cambridge, UK), respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Electrophysiological and locomotion test results were statistically analyzed using repeated measurements and one-way ANOVA, applying Turkey post-hoc test when necessary. Histological data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. Onset and survival data were analyzed using the Mantel-Cox test.

Results

Resveratrol Treatment Delays the Onset of Symptoms and Improves Locomotion Impairment in SODG93A Mice

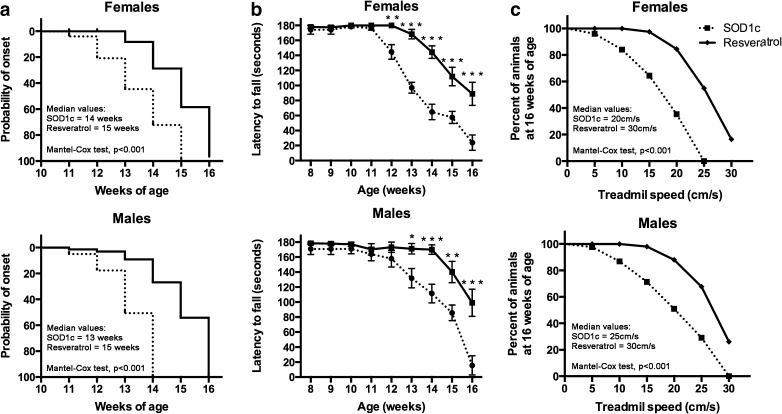

The beginning of symptoms for each animal was considered when it showed the first deficits in locomotor performance in the rotarod test [35]. Results revealed a significant delay of symptoms onset (Mantel-Cox test, p < 0.05) in both female and male treated SOD1G93A mice of 1 and 2 weeks, respectively, compared to untreated mice (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Resveratrol administration delays disease onset and improves locomotor performance in SOD1G93A mice. Continuous lines represent resveratrol SOD1G93A treated animals (n = 23 females; 22 males) while dashed lines represent SOD1G93A untreated mice (n = 20 females; 16 males). a Disease onset assessed by means of rotarod test revealed a significant delay of symptoms appearance of 1 and 2 weeks for male and female SOD1G93A mice, respectively. b Locomotor performance evaluated with rotarod test showed significant improvement with resveratrol administration. Values are expressed as mean±SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. SOD1G93A untreated mice. c Locomotor performance evaluated by the Digigait test and expressed as the proportion of 16-week-old SOD1G93A mice that were able to run at increasing treadmill velocities. Results revealed significantly increased locomotor capacity in animals treated with resveratrol (p < 0.05, Mantel-Cox test)

Locomotor performance was assessed with rotarod and DigiGait tests [27, 32]. Rotarod performance was significantly higher in both female and male resveratrol treated mice than in control SOD1G93A mice (Fig. 1b). Moreover, we explored the ability of animals to run on a treadmill that induced forced locomotion. The proportion of 16-week-old mice that were able to run at increasing velocities revealed a significant improvement of locomotor performance (Mantel-Cox test, p < 0.001) in resveratrol treated mice (Fig. 1c).

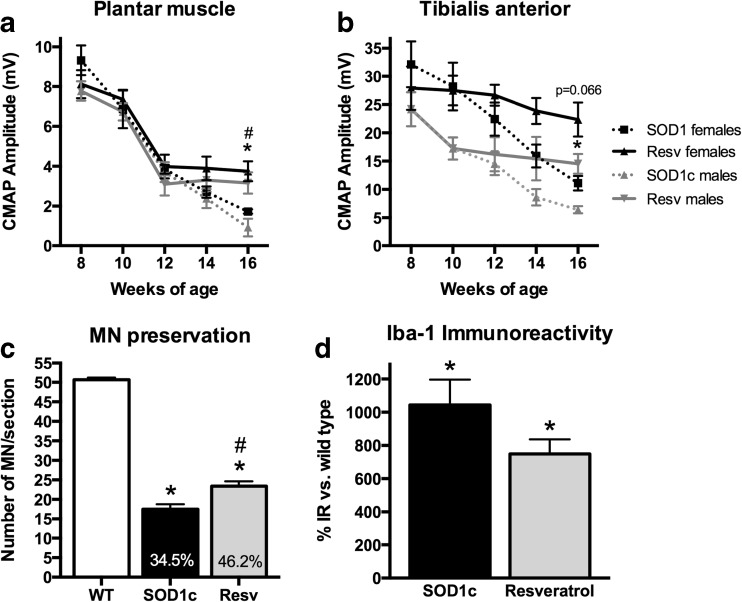

Resveratrol Administration Preserves Lower and Upper Motoneuron Function in SOD1G93A Mice

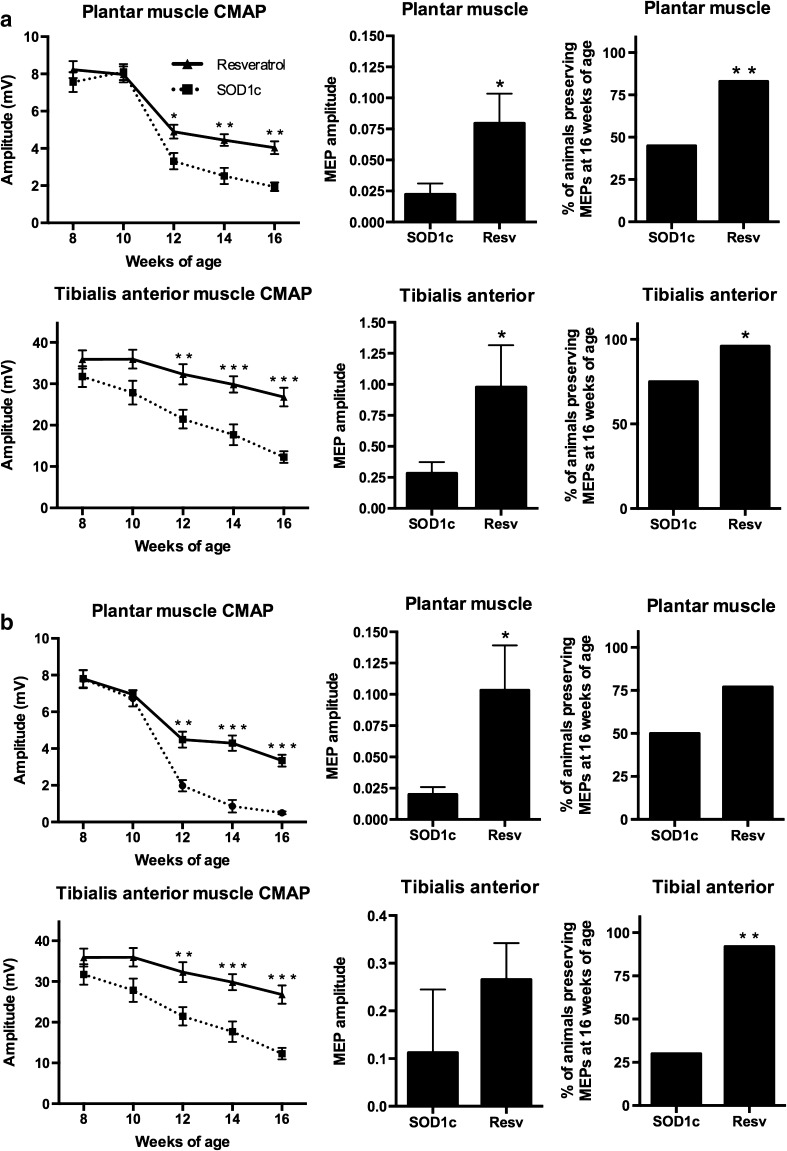

Upper and lower MN function impairment is the main feature of ALS pathology both in human patients [1] and animal models [27, 36, 37]. We analyzed the amplitude of plantar and TA CMAP and MEP as a measure of lower and upper MN functional state, respectively. The CMAP amplitude ranged between 49 and 51 mV for TA muscle and between 6 and 9 mV for plantar muscles in wild type mice, and remained unaltered during all the follow-up. In contrast, there was a progressive decline in CMAP amplitude of SOD1G93A mice from 8 to 16 weeks of age in TA and plantar muscles, as previously reported [27]. The results revealed a significant preservation of plantar and TA CMAP amplitude in resveratrol treated mice of both sexes (Fig. 2). Central motor pathways were also protected by the treatment, since the amplitude of MEP was also significantly preserved at the end of the follow-up. Central motor conduction preservation was also evidenced by an increased proportion of animals with recorded MEP responses in resveratrol treated groups at the end stage of the disease (16 weeks of age) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Resveratrol treatment preserves upper and lower motoneuron function. a Electrophysiological tests performed in female mice (n = 20 untreated vs. 23 resveratrol treated SOD1G93A mice). b Electrophysiological tests performed in male mice (n = 16 untreated vs. 22 resveratrol treated SOD1G93A mice). Results in both sexes revealed significant preservation of compound muscle action potentials (CMAP) and motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes, and an increased proportion of animals maintaining MEPs at 16 weeks of age. Values are mean±SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. SOD1G93A untreated mice

Resveratrol Administration Reduces Spinal Motoneuron Degeneration of SOD1G93A Mice

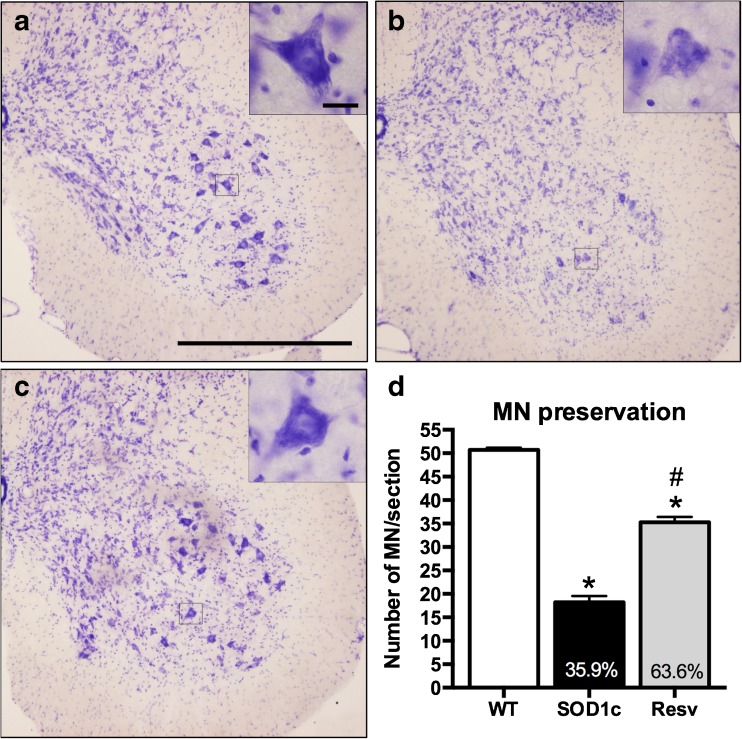

The survival of spinal MNs was assessed by evaluating the number of stained MN cell bodies in the anterior horns of the lumbar spinal cord in 16-week-old mice. We focused the analysis on L4–L5 segments where the motor nuclei of TA and plantar muscles are represented [38]. MN counts were restricted to the lateral part of the lamina IX, since this population of MN innervates the hindlimb muscles. Neurons smaller than 20 μm in diameter were excluded from counting, even if they could be atrophic MNs because they were unlikely to be functional. MN counts of female and male animals were pooled since there were no significant differences between genders. Resveratrol administration significantly reduced MN degeneration in SOD1G93A mice. While SOD1G93A untreated animals had 18.2 ± 1.3 (35.9 % vs. wild type) MNs per section, resveratrol treated mice had 35.2 ± 1.1 (63.6 % vs. wild type), representing an increase of almost two-fold in surviving MNs (Fig. 3). Figure 3 also shows representative images of ventral horns of wild type, untreated and resveratrol treated SOD1G93A mice illustrating the neuroprotective effect.

Fig. 3.

Resveratrol administration significantly preserves spinal motoneurons from degeneration. Representative images of L4 spinal cord at x200 of (a) wild type, (b) SOD1G93A untreated and (c) resveratrol SOD1G93A treated mice (n = 5 animals per each gender and treatment). Scale bar, 500 μm. Inset boxes show detail of single motoneurons at×1000. Scale bar, 20 μm (d) L4–L5 spinal cord motoneurons quantification revealed significant neuroprotection exerted by resveratrol administration (n = 5 per group). Values are mean±SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. wild type, # p < 0.05 vs. untreated SOD1G93A mice

Resveratrol Administration Reduces Microglial Immunoreactivity in the SOD1G93A Mice Spinal Cord

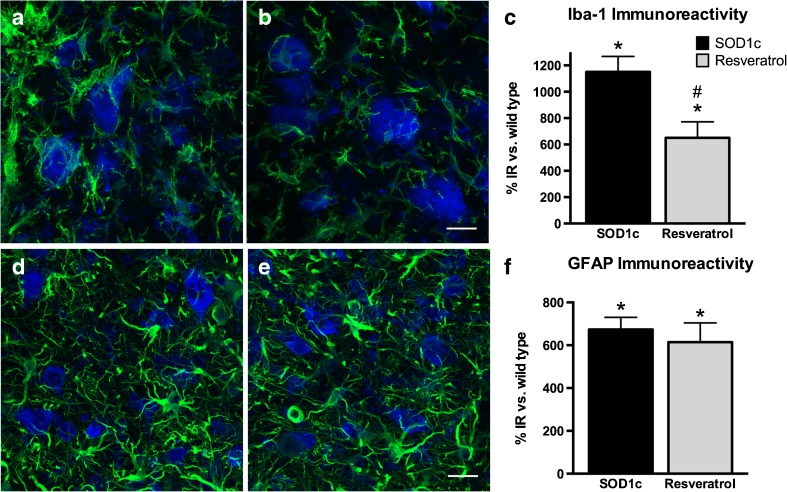

It has been extensively reported that glial cells contribute to MN degeneration both in ALS patients [39] and animal models [40–42]. We evaluated astroglial (GFAP labeled cells) and microglial (Iba-1 labeled cells) immunoreactivity in the anterior horns of lumbar spinal cord sections in order to assess whether resveratrol treatment influenced the response of glial cells. As in the MN counts, female and male animals were pooled due to the lack of differences between them. Results revealed that resveratrol administration significantly reduced microglial but not astroglial immunoreactivity in the anterior horn of SOD1G93A mice. Whereas in untreated SOD1G93A mice Iba-1 immunoreactivity was increased over 1152 % compared to wild type mice, resveratrol treatment reduced it to 649 %. GFAP immunoreactivity remained unchanged after the treatment, since untreated and resveratrol treated animals showed similar values of 673 % and 614 % over wild type levels, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Resveratrol treatment reduces microglial reactivity. Representative confocal images of microglial cells (Iba-1, green) and motoneurons (fluoronissl staining, blue) in (a) untreated SOD1G93A and (b) resveratrol treated SOD1G93A mice (n = 5 animals per gender and treatment). (c) Quantification of Iba-1 immunoreactivity revealed a significant reduction after resveratrol administration. Representative confocal images of astroglial cells (GFAP, green) and motoneurons (fluoronissl staining, blue) in (a) untreated SOD1G93A and (b) resveratrol treated SOD1G93A mice. (c) Quantification of GFAP immunoreactivity did not show differences between groups. Scale bars, 20 μm. *p < 0.05 vs. wild type, #p < 0.05 vs. untreated SOD1G93A mice. IR immunoreactivity

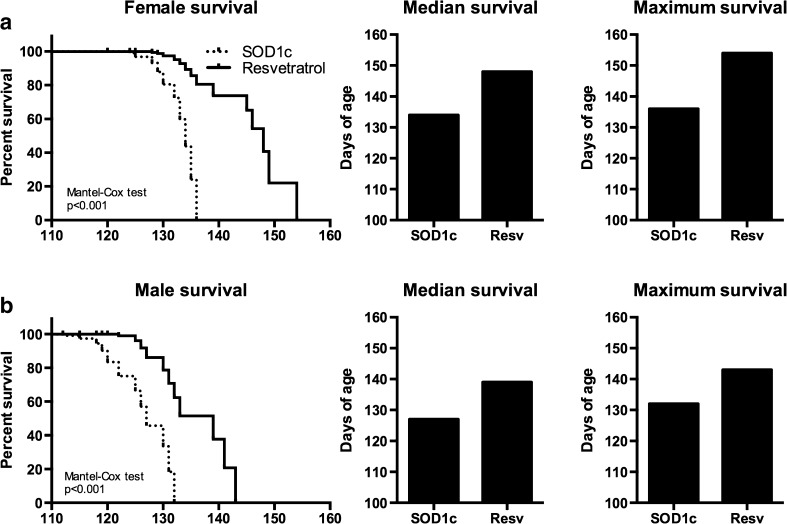

Resveratrol Treatment Significantly Extends Survival of SOD1G93A Mice

The administration of resveratrol from 8 weeks of age significantly prolonged survival of both female and male SOD1G93A mice (Mantel-Cox test, p < 0.001). While untreated female and male SOD1G93A mice lived a median of 134 (mean±SEM=130.7 ± 1.32) and 127 (121.6 ± 2.07) days, treated animals survived for 148 (142 ± 2.76) and 139 (131 ± 2.37) days, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Resveratrol administration significantly extended SOD1G93A mice survival. Resveratrol treatment prolonged SOD1G93A animals median and maximum life span in (a) female (n = 13 treated, 10 untreated) and (b) male (n = 11 treated, 10 untreated) SOD1G93A mice

Resveratrol Treatment from 12 Weeks of Age also Produces Motor Functional Improvement and Neuroprotection in SOD1G93A Mice

Considering the important effect achieved by resveratrol administered from 8 weeks of age, a pre-symptomatic stage of SOD1G93A mice, we wondered if a delayed treatment from the 12th week, when signs of the disease are clearly present, could also ameliorate the animals’ condition. Electrophysiological analysis revealed that resveratrol treatment led to preservation of spinal MN function, evidenced by increased TA and plantar muscle CMAP amplitudes that became statistically significant at 16 weeks of age with respect to values of untreated mice (Fig. 6a,b). This functional effect was accompanied by significant preservation of the number of surviving MNs in L4–L5 spinal cord segments (Fig. 6c), along with a mild reduction of microglial reactivity (p = 0.15, Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

(a–b) Delayed resveratrol administration from 12 weeks of age significantly preserved lower motoneuron function. Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude of plantar and tibialis anterior muscles in female and male SOD1G93A mice (n = 8 treated and 8 untreated for each sex). Resveratrol administration from 12 weeks of age (c) significantly protects spinal motoneurons in L4–L5 spinal cord segments and (d) slightly reduces microglial reactivity (p = 0.15). Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. wild type, #p < 0.05 vs. corresponding untreated SOD1G93A mice

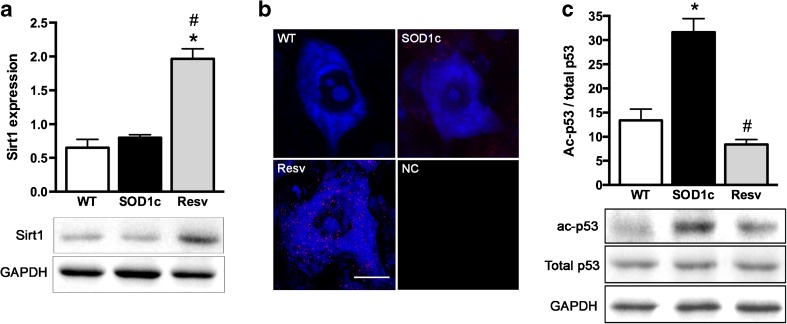

Resveratrol Administration Induces Sirtuin1 Expression and Activation

It has been extensively described that, among other effects, resveratrol promotes neuroprotection by increasing Sirt1 activity [9, 43]. To assess whether Sirt1 was overexpressed, we analyzed Sirt1 levels in the lumbar spinal cord by western blot analysis. Results showed a marked increase in Sirt1 expression in resveratrol treated animals (Fig. 7a). Moreover, immunohistochemistry of the ventral spinal cord revealed that Sirt1 expression was localized in the MNs (Fig. 7b). To check the activity state of Sirt1 we evaluated the acetylation degree of one of its most important downstream targets, p53. Indeed, we found a significant reduction in the acetylation of p53, indicating increased Sirt1 activation in the resveratrol treated group (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Increased sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) expression and activation in SOD1G93A spinal motoneurons after resveratrol treatment. a Sirt1 expression was significantly increased in the ventral part of the lumbar spinal cord of resveratrol treated animals. b Confocal microphotoghraps of L4 spinal cord confirmed that this expression was localized inside spinal motoneurons. Scale bar, 20 μm. WT wild type, SOD1c untreated SOD1G93A mice, Resv resveratrol treated mice, NC negative control without Sirtuin 1 primary antibody or Fluoronissl staining. c Evaluation of Sirt1 activity by measuring the acetylation levels of p53 revealed significant deacetylation and thus, an increased activity of Sirt1 in SOD1G93A mice treated with resveratrol. *p < 0.05 vs. wild type, #p < 0.05 vs. untreated SOD1G93A mice

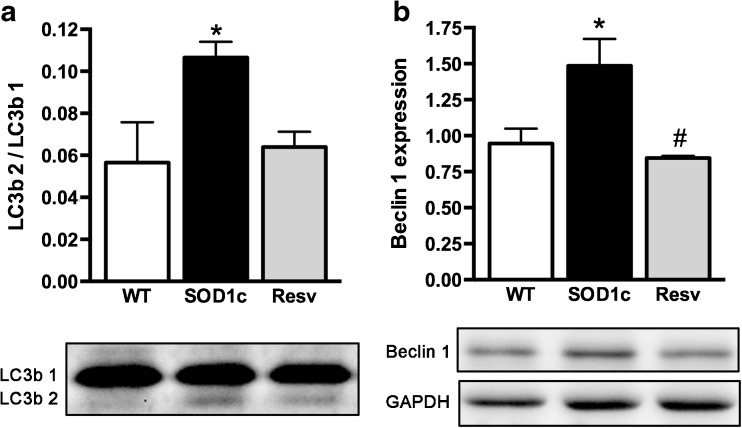

Resveratrol Treatment Restores Autophagic Flux

Increasing evidence suggests that autophagic abnormalities may contribute to ALS physiopathology [44] and resveratrol has been reported as a modulator of autophagia through Sirt1 activation [45]. Thus, we examined the autophagic state of the animals after resveratrol treatment. The results showed normalization of the early markers of autophagy LC3II and Beclin 1 after resveratrol administration (Fig. 8), suggesting that resveratrol treatment normalizes autophagic flux in the SOD1G93A mouse spinal cord.

Fig. 8.

Recovery of normal autophagic flux after resveratrol treatment. a LC3b2 / LC3b1 ratio. b Beclin 1 expression were normalized by resveratrol administration to SOD1G93A mice. *p < 0.05 vs. wild type, #p < 0.05 vs. untreated SOD1G93A mice

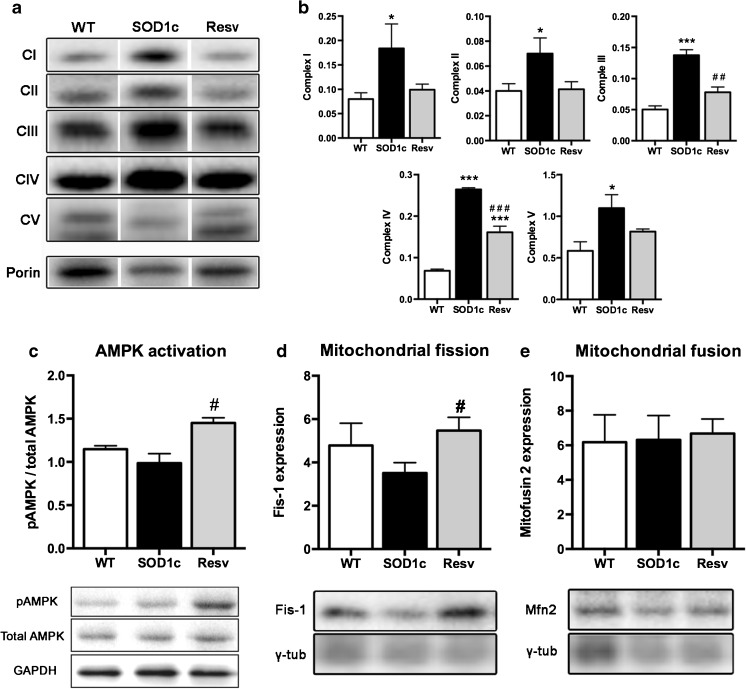

Resveratrol Restores Mitochondrial Function and Promotes Mitochondrial Biogenesis through AMPK Pathway

Recent evidence has demonstrated that resveratrol promotes mitochondrial biogenesis through the activation of AMPK [16]. Thus, we first assessed the expression and activation of AMPK by analyzing the active phospho-AMPK and total AMPK forms. Results revealed a significant increase of the pAMPK/AMPK ratio (p < 0.01) in the ventral part of the lumbar spinal cord in SOD1G93A mice treated with resveratrol (Fig. 9c). Next, we analyzed whether resveratrol treatment led to changes of mitochondrial behavior. We found that SOD1G93A untreated mice had an increased expression of the respiratory chain mitochondrial complexes compared to wild-type mice. In contrast, resveratrol treatment reduced the expression of these mitochondrial complexes, with levels similar to wild type mice (Fig. 9a, b). Finally, we evaluated mitochondrial fission and fusion in the ventral spinal cord. Results revealed a significant increase of Fis-1 expression, a marker of mitochondrial fission without alterations of mitofusin 2, an indicator of mitochondrial fusion. Taken together, these results suggest that the activation of AMPK by resveratrol likely leads to a switch of the mitochondrial response to energetic stress from the upregulation of respiratory chain complexes to a more adaptive increase of mitochondrial biogenesis.

Fig. 9.

Resveratrol administration normalized mitochondrial function and increased mitochondrial biogenesis. a Representative western blot of the five different mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes. b Quantification revealed significant increase of all complexes expression in control SOD1G93A mice, whereas in resveratrol administered SOD1G93A mice the levels were close to normal. c Enhanced AMPK activation after resveratrol treatment, evidenced by an increased pAMPK/AMPK ratio. d Increased mitochondrial biogenesis in resveratrol administered SOD1G93A animals. e Mitochondrial fusion was not altered by the treatment. Values are mean±SEM. *p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 vs. wild type; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 vs. untreated SOD1G93A mice

Discussion

The physiopathological complexity that characterizes ALS [5, 6] is one of the most limiting factors for the development of successful therapies. Several works have been conducted targeting one or more of the physiopathological mechanisms linked to the disease, but even if they achieved positive experimental results they have failed to translate into successful human therapies [7, 8]. It is conceivable that successful treatments should not only fight pathogenic elements of the disease but also promote cellular neuroprotective pathways providing surviving tools to the MNs. The main goal of the present study was to assess the potential therapeutic effect of resveratrol in the SOD1G93A model of ALS, since it has been reported to produce beneficial neuroprotective effects on other neuropathologies through the modulation of several cellular pathways [9]. Our results reveal that resveratrol significantly delayed disease symptoms onset by 1–2 weeks and importantly improved the locomotor performance of the SOD1G93A animals. Moreover, electrophysiological tests showed maintenance of spinal MN function and, by the first time, a significant improvement of upper MN function. These effects were accompanied by an increased preservation of lower MNs cell bodies in the lumbar spinal cord. Resveratrol administration was also able to significantly extend both female and male SOD1G93A lifespan. Furthermore, delayed resveratrol administration from the beginning of evident locomotor impairments (12 weeks of age) still produced a significant preservation of spinal MN function and cell bodies in the spinal cord. Further experiments revealed that these therapeutic effects were mediated by the increased expression and activation of Sirt1 and AMPK in the spinal cord, both well-known effectors of resveratrol. Moreover, we observed significant restoration of the autophagic flux normal values and, more importantly, increased mitochondrial biogenesis in the spinal cord of resveratrol treated animals.

It has been previously shown that resveratrol and its downstream effectors Sirt1 and AMPK promote protective effects both in neurodegenerative and traumatic injury models. Indeed, potent therapeutic effects of resveratrol administration were reported in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and accelerated ageing [10, 26, 46], multiple sclerosis [47, 48], Huntington’s disease [9, 49], Parkinson’s disease [22, 50], and even reducing peripheral axonal degeneration [51] or promoting functional recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury [23]. In this sense, resveratrol has been also reported to exert neuroprotection on in vitro models of ALS. Thus, Kim et al. [26] showed that resveratrol reduces cell death on primary cultures of neurons overexpressing the SOD1G93A mutant protein, and Yáñez et al. [52] demonstrated that this compound protects from neuronal death triggered by CSF of ALS patients. There is some controversy about the in vivo effect of resveratrol administration in SOD1G93A mice. Markert et al. [53] reported that dietary resveratrol given at 25 mg/kg did not produce functional effects, whereas Han et al. [54] showed that intraperitoneal administration of resveratrol at 20 mg/kg led to improved functional outcome although less important than found in our study. A likely explanation of such discrepancies would be the differences in the dose and the route of administration. Resveratrol pharmacokinetics have been extensively studied, revealing that enteric absorption is up to 80 % after oral administration, while up to 98 % of the compound is excreted 7–15 h after administration [55]. Accordingly, resveratrol treatment should be performed either dietary at high doses or intraperitoneally but with more frequent injections than made in the above-mentioned studies.

Although many studies have been conducted to elucidate the mechanisms of action of resveratrol, they still remain controversial. It is known that resveratrol acts through some specific effector molecules, such as Sirt1 or AMPK [11, 12]. Sirt1 is a NAD+-dependent deacetylase that plays an important role regulating cell metabolism and has recently been postulated as a neuroprotective element in several neurodegenerative disorders [13]. Sirt1 induces protective effects since it is upstream of multiple effectors that participate in several cell processes, such as inflammation [43], autophagy [45] and mitochondrial function [16, 46], all of them related to ALS physiopathology [5, 56]. In the present work, we found that Sirt1 was overexpressed in spinal MNs of SOD1G93A mice after resveratrol administration. Then, we assessed Sirt1 activity by evaluating the deacetylation degree of one of the most important Sirt1 substrates, p53. Indeed, we found significantly reduced acetylation of p53, evidencing an increased activity of Sirt1.

Autophagy serves multiple physiological functions, such as protein degradation, organelle turnover and response to stress. Dysregulation of autophagy has been reported to contribute to ALS pathology both in human patients and animal models [44, 57]. Li et al. [58] reported a progressive increase of the relative amount of LC3b II from 90 to 140 days of age in SOD1G93A mice, accompanied by accumulation of autophagic vesicles. These findings could be the result of autophagic flux impairment. Since it has been hypothesized that Sirt1 plays its protective role through the modulation of autophagy [45, 59], we evaluated the expression of two of the most typical markers of autophagy, LC3 and Beclin-1. Our results revealed that both Beclin-1 and the LC3bII/LC3bI ratio were significantly increased in SOD1G93A mice compared to wild type littermates, evidencing impairment of the autophagic flux. In contrast, after resveratrol administration, both markers were normalized to wild type values. Though the restoration of the autophagic flux may be a direct effect downstream of resveratrol-induced Sirt1 activation, it is also possible that it could be an indirect consequence derived from the general improvement of the mice condition and, thus, of restoration of MN homeostasis.

On the other hand, recent evidence suggests that the resveratrol-induced Sirt1 activation works through AMPK activation [18]. According to this view, Park et al. [12] recently described that resveratrol promotes AMPK phosphorilation through the inhibition of cAMP phosphodiesterase, thus increasing the amount of cAMP. AMPK then activates Sirt1 indirectly by elevating intracellular levels of its cosubstrate, NAD+[18, 19]. Alternatively, other authors proposed that resveratrol may first activate Sirt1, leading to AMPK activation via deacetylation and activation of the AMPK kinase LKB1 [20, 21]. In any case, resveratrol administration leads to direct or indirect activation of AMPK, as evidenced in our results by the increased pAMPK/totalAMPK ratio in SOD1G93A treated animals.

Numerous studies have highlighted the common role of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases [60]. Although there is no consensus about the exact role of mitochondrial abnormalities [61], it is accepted that mitochondrial dysfunction is an important hallmark of ALS pathogenesis [5, 62, 63]. Several authors have shown deficits in mitochondrial function in the spinal cord and muscles of both human patients [64] and animal models of ALS [65–67]. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and induces biogenesis, although there is some controversy about whether this effect is mediated by AMPK activation [18] or by Sirt1 [16, 68]. Since both Sirt1 and AMPK were found over-activated in SOD1G93A animals treated with resveratrol, we performed a detailed analysis on mitochondria. Contrary to what was expected, we found a significant increase of all the respiratory chain complexes in SOD1G93A mice compared to wild-type littermates, but complete normalization following resveratrol treatment. Then, we found an increased expression of the fission protein Fis-1 in resveratrol treated SOD1G93A mice, evidencing an active process of mitochondrial biogenesis. Our hypothesis is that resveratrol may promote a switch of mitochondrial response to cellular stress from the overexpression of respiratory chain complexes and the consequent increased production of harmful oxidative mediators, to a more adaptive response by increasing mitochondrial biogenesis. It has also been reported that resveratrol administration promotes mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscles [12, 16] through AMPK activation. Further studies are needed to assess whether resveratrol benefits in SOD1G93A mice could be partially explained by its effect on skeletal muscles.

Neuroinflammation is another common pathological hallmark of neurodegenerative disorders [69] and its modulation has been proposed as a potential therapeutic target [70]. In ALS, the inflammatory response is characterized by the activation and proliferation of microglia, and the infiltration of T cells into the spinal cord. Although it is still unknown whether it is a cause or a consequence of the MN degeneration, some evidence suggested that its manipulation could ameliorate the disease progression. Resveratrol has been found to modulate neuroinflammation in both in vivo and in vitro models, specifically targeting activated micloglial cells [71]. Actually, resveratrol suppresses the activation of the NF-kB pathway in LPS-activated microglia by reducing the phosphorylation and consequent degradation of its inhibitor, IkB [72–75]. Our results demonstrate that microglial, but not astroglial reactivity, was significantly diminished with resveratrol administration compared to untreated SOD1G93A mice. Although further studies should be performed to assess the exact effect, resveratrol modulates microglia activity, thus contributing to the neuroprotection observed in resveratrol administered SOD1G93A mice.

The results of this work demonstrate that resveratrol exerts potent therapeutic actions in the SOD1G93A model of ALS. Here, we show for the first time a treatment that combines significant preservation of both lower and upper MN function, translating into significantly delayed disease onset and extended animal survival. These effects were associated with an important preservation of MN and a significant reduction of microglial reactivity in the spinal cord. Molecular analyses revealed that the beneficial effects of reseveratrol were accompanied by an activation of Sirt1 and AMPK. Such pluri-functional targets that combine the inhibition of detrimental processes and the promotion of neuroprotective pathways may provide better translational outcomes than drugs with more restricted targets. These findings strongly suggest that resveratrol may be a promising therapy for motoneuron diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1224 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants PI1001787 and PI111532, TERCEL and CIBERNED funds from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria of Spain, grant SAF2009-12495 from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación of Spain, FEDER funds, and Action COST-B30 of the EC. We thank the technical help of Jessica Jaramillo and Marta Morell. RM is the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Educación of Spain.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Wijesekera LC, Leigh PN. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen DR. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;364:362. doi: 10.1038/364362c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ripps ME, Huntley GW, Hof PR, Morrison JH, Gordon JW. Transgenic mice expressing an altered murine superoxide dismutase gene provide an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:689–693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosco DA, Morfini G, Karabacak NM, Song Y, Gros-Louis F, Pasinelli P, et al. Wild-type and mutant SOD1 share an aberrant conformation and a common pathogenic pathway in ALS. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1396–1403. doi: 10.1038/nn.2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasinelli P, Brown RH. Molecular biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:710–723. doi: 10.1038/nrn1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferraiuolo L, Higginbottom A, Heath PR, Barber SC, Greenald D, Kirby J, et al. Dysregulation of astrocyte-motoneuron cross-talk in mutant superoxide dismutase 1-related amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2011;134:2627–2641. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothstein JD. Of mice and men: reconciling preclinical ALS mouse studies and human clinical trials. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:423–426. doi: 10.1002/ana.10561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benatar M. Lost in translation: treatment trials in the SOD1 mouse and in human ALS. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albani D, Polito L, Signorini A, Forloni G. Neuroprotective properties of resveratrol in different neurodegenerative disorders. BioFactors. 2010;36:370–376. doi: 10.1002/biof.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porquet D, Casadesús G, Bayod S, Vicente A, Canudas AM, Vilaplana J, et al. Dietary resveratrol prevents Alzheimer's markers and increases life span in SAMP8. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:1851–1865. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tennen RI, Michishita-Kioi E, Chua KF. Finding a target for resveratrol. Cell. 2012;148:387–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S-J, Ahmad F, Philp A, Baar K, Williams T, Luo H, et al. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell. 2012;148:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donmez G. The neurobiology of sirtuins and their role in neurodegeneration. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong J-K, Moon M-H, Bae B-C, Lee Y-J, Seol J-W, Kang H-S, et al. Autophagy induced by resveratrol prevents human prion protein-mediated neurotoxicity. Neurosci Res. 2012;73:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong JK, Moon MH, Lee YJ, Seol JW, Park SY. Autophagy induced by the class III histone deacetylase Sirt1 prevents prion peptide neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price NL, Gomes AP, Ling AJY, Duarte FV, Martin-Montalvo A, North BJ, et al. SIRT1 is required for AMPK activation and the beneficial effects of resveratrol on mitochondrial function. Cell Metabolism. 2012;15:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baur JA. Biochemical effects of SIRT1 activators. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1804;2010:1626–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantó C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD + metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulco M, Cen Y, Zhao P, Hoffman EP, McBurney MW, Sauve AA, et al. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev Cell. 2008;14:661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou X, Xu S, Maitland-Toolan KA, Sato K, Jiang B, Ido Y, et al. SIRT1 regulates hepatocyte lipid metabolism through activating AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20015–20026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802187200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan F, Cacicedo JM, Ruderman N, Ido Y. SIRT1 modulation of the acetylation status, cytosolic localization, and activity of LKB1. Possible role in AMP-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27628–27635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805711200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y, Li X, Zhu JX, Xie W, Le W, Fan Z, et al. Resveratrol-activated AMPK/SIRT1/autophagy in cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosignals. 2011;19:163–174. doi: 10.1159/000328516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Shi Z, Fan L, Zhang C, Wang K, Wang B. Resveratrol improves neuron protection and functional recovery in rat model of spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2011;1374:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L-M, Wang Y-J, Cui M, Luo W-J, Wang X-J, Barber PA, et al. A dietary polyphenol resveratrol acts to provide neuroprotection in recurrent stroke models by regulating AMPK and SIRT1 signaling, thereby reducing energy requirements during ischemia. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37:1669–1681. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Zhang Y, Tang L, Zhang N, Fan D. Protective effects of resveratrol through the up-regulation of SIRT1 expression in the mutant hSOD1-G93A-bearing motor neuron-like cell culture model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci Lett. 2011;503:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, Nguyen MD, Dobbin MM, Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Rodgers JT, et al. SIRT1 deacetylase protects against neurodegeneration in models for Alzheimer's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The EMBO Journal. 2007;26:3169–3179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancuso R, Santos-Nogueira E, Osta R, Navarro X. Electrophysiological analysis of a murine model of motoneuron disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:1660–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valero-Cabré A, Navarro X. H reflex restitution and facilitation after different types of peripheral nerve injury and repair. Brain Res. 2001;919:302–312. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)03052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García-Alías G, Verdú E, Forés J, López-Vales R, Navarro X. Functional and electrophysiological characterization of photochemical graded spinal cord injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:501–510. doi: 10.1089/089771503765355568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks SP, Dunnett SB. Tests to assess motor phenotype in mice: a user's guide. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrn2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miana-Mena FJ, Muñoz MJ, Yagüe G, Mendez M, Moreno M, Ciriza J, et al. Optimal methods to characterize the G93A mouse model of ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2005;6:55–62. doi: 10.1080/14660820510026162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mancuso R, Oliván S, Osta R, Navarro X. Evolution of gait abnormalities in SOD1(G93A) transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2011;1406:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mancuso R, Oliván S, Rando A, Casas C, Osta R, Navarro X. Sigma-1R agonist improves motor function and motoneuron survival in ALS mice. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9:814–826. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0140-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penas C, Pascual-Font A, Mancuso R, Forés J, Casas C, Navarro X. Sigma receptor agonist 2-(4-morpholinethyl)1 phenylcyclohexanecarboxylate (Pre084) increases GDNF and BiP expression and promotes neuroprotection after root avulsion injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:831–840. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ralph GS, Radcliffe PA, Day DM, Carthy JM, Leroux MA, Lee DCP, et al. Silencing mutant SOD1 using RNAi protects against neurodegeneration and extends survival in an ALS model. Nat Med. 2005;11:429–433. doi: 10.1038/nm1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer LR, Culver DG, Tennant P, Davis AA, Wang M, Castellano-Sanchez A, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a distal axonopathy: evidence in mice and man. Exp Neurol. 2004;185:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozdinler PH, Benn S, Yamamoto TH, Güzel M, Brown RH, Macklis JD. Corticospinal motor neurons and related subcerebral projection neurons undergo early and specific neurodegeneration in hSOD1G93A transgenic ALS mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4166–4177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4184-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McHanwell S, Biscoe TJ. The localization of motoneurons supplying the hindlimb muscles of the mouse. Philos Trans R Soc Lond, B, Biol Sci. 1981;293:477–508. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haidet-Phillips AM, Hester ME, Miranda CJ, Meyer K, Braun L, Frakes A, et al. Astrocytes from familial and sporadic ALS patients are toxic to motor neurons. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz-Amarilla P, Olivera-Bravo S, Trias E, Cragnolini A, Martinez-Palma L, Cassina P, et al. Phenotypically aberrant astrocytes that promote motoneuron damage in a model of inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18126–18131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110689108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamanaka K, Boillee S, Roberts EA, Garcia ML, McAlonis-Downes M, Mikse OR, et al. Mutant SOD1 in cell types other than motor neurons and oligodendrocytes accelerates onset of disease in ALS mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7594–7599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802556105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanagi T, Nakamura Y, Suzuki E, Uchino S, Aoki M, Warita H, et al. Involvement of activated microglia in increased vulnerability of motoneurons after facial nerve avulsion in presymptomatic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model rats. Glia. 2012;60:782–793. doi: 10.1002/glia.22308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han S-H. Potential role of sirtuin as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. J Clin Neurol. 2009;5:120. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2009.5.3.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song C-Y, Guo J-F, Liu Y, Tang B-S. Autophagy and its comprehensive impact on ALS. Int J Neurosci. 2012;122:695–703. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.714430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Liu J, Bruns NE, et al. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3374–3379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712145105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herskovits AZ, Guarente L. Sirtuin deacetylases in neurodegenerative diseases of aging. Cell Res. 2013;23:746–758. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fonseca-Kelly Z, Nassrallah M, Uribe J, Khan RS, Dine K, Dutt M, et al. Resveratrol neuroprotection in a chronic mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2012;3:84. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nimmagadda VK, Bever CT, Vattikunta NR, Talat S, Ahmad V, Nagalla NK, et al. Overexpression of SIRT1 protein in neurons protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through activation of multiple SIRT1 targets. J Immunol. 2013;190:4595–4607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maher P, Dargusch R, Bodai L, Gerard PE, Purcell JM, Marsh JL. ERK activation by the polyphenols fisetin and resveratrol provides neuroprotection in multiple models of Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;20:261–270. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin F, Wu Q, Lu Y-F, Gong Q-H, Shi J-S. Neuroprotective effect of resveratrol on 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson's disease in rats. Euro J Pharmacol. 2008;600(1-3):78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Araki T, Sasaki Y, Milbrandt J. Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevent axonal degeneration. Science. 2004;305:1010–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.1098014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yáñez M, Galán L, Matías-Guiu J, Vela A, Guerrero A, García AG. CSF from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients produces glutamate independent death of rat motor brain cortical neurons: Protection by resveratrol but not riluzole. Brain Res 2;1423:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Markert CD, Kim E, Gifondorwa DJ, Childers MK, Milligan CE. A single-dose resveratrol treatment in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Med Food. 2010;13:1081–1085. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han S, Choi JR, Shin KS, Kang SJ. Resveratrol upregulated heat shock proteins and extended the survival of G93A-SOD1 mice. Brain Res. 2012;1483:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amri A, Chaumeil JC, Sfar S, Charrueau C. Administration of resveratrol: what formulation solutions to bioavailability limitations? J Control Release. 2012;158:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robberecht W, Philips T. The changing scene of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:248–264. doi: 10.1038/nrn3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen S, Zhang X, Song L, Le W. Autophagy dysregulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Pathology. 2011;22:110–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L, Zhang X, Le W. Altered macroautophagy in the spinal cord of SOD1 mutant mice. Autophagy. 2008;4:290–293. doi: 10.4161/auto.5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morselli E, Maiuri MC, Markaki M, Megalou E, Pasparaki A, Palikaras K, et al. Caloric restriction and resveratrol promote longevity through the Sirtuin-1-dependent induction of autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e10. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boillee S, Vandevelde C, Cleveland D. ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron. 2006;52:39–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi P, Gal J, Kwinter DM, Liu X, Zhu H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1802;2010:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferraiuolo L, Kirby J, Grierson AJ, Sendtner M, Shaw PJ. Molecular pathways of motor neuron injury in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:616–630. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiedemann FR, Winkler K, Kuznetsov AV, Bartels C, Vielhaber S, Feistner H, et al. Impairment of mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1998;156:65–72. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fuchs A, Kutterer S, Mühling T, Duda J, Schütz B, Liss B, et al. Selective mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake deficit in disease endstage vulnerable motoneurons of the SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Physiol (Lond) 2013;591:2723–2745. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.247981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jung C, Higgins CMJ, Xu Z. Mitochondrial electron transport chain complex dysfunction in a transgenic mouse model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2002;83:535–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kong J, Xu Z. Massive mitochondrial degeneration in motor neurons triggers the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice expressing a mutant SOD1. J Neurosci. 1999;18:3241–3250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03241.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell. 2006;127:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khandelwal PJ, Herman AM, Moussa CEH. Inflammation in the early stages of neurodegenerative pathology. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;238:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yong VW, Rivest S. Taking advantage of the systemic immune system to cure brain diseases. Neuron. 2009;64:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang F, Liu J, Shi J-S. Anti-inflammatory activities of resveratrol in the brain: role of resveratrol in microglial activation. Euro J Pharmacol. 2010;636:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bi XL, Yang JY, Dong YX, Wang JM, Cui YH, Ikeshima T, et al. Resveratrol inhibits nitric oxide and TNF-alpha production by lipopolysaccharide-activated microglia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Candelario-Jalil E, de Oliveira A, Gräf S, Bhatia HS, Hüll M, Muñoz E, et al. Resveratrol potently reduces prostaglandin E2 production and free radical formation in lipopolysaccharide-activated primary rat microglia. J Neuroinflamm. 2007;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heynekamp JJ, Weber WM, Hunsaker LA, Gonzales AM, Orlando RA, Deck LM, et al. Substituted trans-stilbenes, including analogues of the natural product resveratrol, inhibit the human tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced activation of transcription factor nuclear factor kappaB. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7182–7189. doi: 10.1021/jm060630x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meng X-L, Yang JY, Chen G-L, Wang L-H, Zhang L-J, Wang S, et al. Effects of resveratrol and its derivatives on lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and their structure-activity relationships. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;174:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1224 kb)