Abstract

The adipocyte-derived hormone leptin plays a critical role in the central transmission of energy balance to modulate reproductive function. However, the neurocircuitry underlying this interaction remains elusive, in part due to incomplete knowledge of first-order leptin-responsive neurons. To address this gap, we explored the contribution of predominantly inhibitory (GABAergic) neurons versus excitatory (glutamatergic) neurons in the female mouse by selective ablation of the leptin receptor in each neuronal population: Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice, respectively. Female Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox but not Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice were obese. Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice had delayed or absent vaginal opening, persistent diestrus, and atrophic reproductive tracts with absent corpora lutea. In contrast, Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox females exhibited reproductive maturation and function comparable to Leprlox/lox control mice. Intracerebroventricular administration of kisspeptin-10 to Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice elicited robust gonadotropin responses, suggesting normal gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal and gonadotrope function. However, adult ovariectomized Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice displayed significantly reduced levels of Kiss1 (but not Tac2) mRNA in the arcuate nucleus, and a reduced compensatory luteinizing hormone increase compared with control animals. Estradiol replacement after ovariectomy inhibited gonadotropin release to a similar extent in both groups. These animals also exhibited a compromised positive feedback response to sex steroids, as shown by significantly lower Kiss1 mRNA levels in the AVPV, compared with Leprlox/lox mice. We conclude that leptin-responsive GABAergic neurons, but not glutamatergic neurons, act as metabolic sensors to regulate fertility, at least in part through modulatory effects on kisspeptin neurons.

Keywords: female, GABA, glutamate, leptin, metabolism, reproduction

Introduction

Reproduction is an essential function in mammalian physiology, with an elevated energy demand that is exquisitely regulated by metabolic cues. Food deprivation can delay, and even prevent, sexual maturation and disrupt fertility across species (Frisch, 1985; Ahima et al., 1996). In humans, starvation is associated with menstrual cycle disruption in females, mediated by a decrease in luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion (Welt et al., 2004) that reflects reduced activity of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons in response to metabolic cues (Mantzoros et al., 2011). Circulating LH levels return to normal once dietary needs are addressed (Schreihofer et al., 1993; Mantzoros et al., 2011).

The hypothalamus is a hub where the metabolic and reproductive systems converge. Among multiple metabolic cues, leptin plays a critical role in the regulation of the reproductive axis and energy homeostasis (Barash et al., 1996). Mice deficient in (ob/ob) or resistant to (db/db) leptin are obese and infertile (Coleman, 1978; Chehab et al., 1996; de Luca et al., 2005). Paradoxically, these animals exhibit a starvation phenotype despite having abundant body fat storage (Chehab, 2000). Treatment with recombinant leptin restores fertility in ob/ob mice, even before significant weight loss (Chehab et al., 1996; Mounzih et al., 1997). Consequently, leptin has been recognized as a metabolic gate to GnRH and gonadotropin secretion, facilitating sexual maturation and fertility (Cheung et al., 1997; Holtkamp et al., 2003).

Despite the ubiquitous expression of leptin receptors, experimental data suggest that leptin action in the brain is sufficient to modulate fertility (Cohen et al., 2001). The neuron-specific restoration of the leptin receptor (Leprb) rescues obesity and infertility in db/db mice (de Luca et al., 2005). This finding confirms previous observations in leptin-deficient female mice, which can achieve pregnancy by gonadotropin-induced ovulation, demonstrating that infertility is linked to central hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction rather than ovarian deficiency (Israel and Chua, 2010). Interestingly, GnRH neurons do not express leptin receptors, indicating an indirect action of leptin through interneurons afferent to GnRH neurons (Quennell et al., 2009). Moreover, only a small subset of neurons that secrete kisspeptin, a potent and direct activator of GnRH secretion, express leptin receptors (Smith et al., 2006; Louis et al., 2011). Furthermore, ablation of leptin receptors in kisspeptin-secreting neurons did not affect fertility or body weight (Donato et al., 2011; Louis et al., 2011), suggesting the presence of unidentified circuits of leptin-responsive neurons involved in the metabolic control of GnRH neuronal activity that modulate the kisspeptinergic tone.

The goal of the present study is to identify the nature of first-order, leptin-responsive neurons mediating the effects of energy homeostasis on reproductive function in the female mouse. To characterize these neurons as predominantly inhibitory (GABAergic) or excitatory (glutamatergic), we selectively ablated the leptin receptor in each of these neuronal populations. We report that the ablation of leptin receptors in GABAergic neurons, but not glutamatergic neurons, recapitulates the ob/ob and db/db infertility phenotype in females (Swerdloff et al., 1978; Batt et al., 1982; de Luca et al., 2005).

Materials and Methods

Animal care.

The animal studies were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on the Use of Animals in Research and Teaching in the Harvard Medical School Center for Animal Resources and Comparative Medicine. The mice were maintained under a 12 h light/dark cycle and provided with standard rodent chow and water ad libitum.

Transgenic mice.

Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox, and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mouse lines were generated by gene targeting as described previously (Vong et al., 2011). In brief, VgatCre/Cre;Leprlox/WT or Vglut2Cre/Cre;Leprlox/lox male mice were mated with Leprlox/lox female mice (Balthasar et al., 2004; McMinn et al., 2004). The VgatCre/+ mice and Vglut2Cre/+ were generated by insertion of an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-Cre recombinase cassette downstream of the stop codon of endogenous genes Vgat (vesicular GABA transporter) and Vglut2 (synaptic vesicular glutamate transporter), respectively (Vong et al., 2011). The Leprlox/+ mice were generated by the insertion of two loxP sites and an frt site flanking the coding exon 17 of the leptin receptor gene (Balthasar et al., 2004; McMinn et al., 2004). This modification (Meyers et al., 1998) permits the conditional ablation of Lepr driven by the IRES-Cre recombinase cassettes described above (Balthasar et al., 2004; McMinn et al., 2004). The mice were genotyped by PCR using the following primers to identify expression of the Cre amplicon (5′-GCC CTG GAA GGG ATT TTT GAA GCA-3′ and 5′-ATG GCT AAT CGC CAT CTT CCA GCA-3′), endogenous ghrelin (Ghrl) as internal amplification control (5′-GGT CAG CCT AAT TAG CTC TGT-3′ and 5′-GAT CTC CAG CTC CTC CTC TGT C-3′), and primers recognizing the loxP site (5′-AAT GAA AAA GTT GTT TTG GGA CGA-3′ and 5′-CAG GCT TGA GAA CAT GAA CAC AAC AAC-3′). Ghrl is used as an internal amplification control when screening for the presence of Cre recombinase during the genotyping of the animals. This control excludes any potential false-negative results when Cre recombinase is not amplified.

Puberty assessment.

The following parameters were monitored in the Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox, Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox, and Leprlox/lox female mice: (1) changes in body weight, (2) progression to vaginal opening, and (3) timing of first estrus. Body weight was measured twice a week from postnatal day (P)25 to P40 followed by once per week from P40 to P60, using six mice from each genotype group. Prepubertal female mice were monitored daily for vaginal opening (as indicated by complete canalization of the vagina) until P45. For this purpose, we monitored six mice for the Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox and Leprlox/lox groups, followed by assessment of vaginal cytology for another 25 d after vaginal opening to identify the timing of first estrus and to evaluate estrous cyclicity. Of note, 12 Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females were monitored to obtain a more accurate determination of the fraction with vaginal opening. Subsequently, we further increased the number of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females monitored to gather a total of six Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females with complete vaginal opening in which to assess first estrus and estrous cyclicity.

Histology.

Ovaries and uteri were collected from six animals for each genotype group, weighed and fixed in Bouin's solution. The Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice were used independent of the vaginal opening status. The tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned (10 μm) for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Harvard Medical School Rodent Pathology Core) and images acquired under 4× magnification. The ovaries were analyzed for presence and type of follicles and for presence of corpora lutea.

Kisspeptin functional assay.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane anesthesia and received an intracerebroventricular injection (Furuta et al., 2001) of 5 μl kisspeptin-10 (Kp10, 1 nmol) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl; Gottsch et al., 2004; Castellano et al., 2005). Blood samples (200 μl) were collected by retro-orbital bleeding (van Herck et al., 1998) 20 min postinjection. The animals were injected with Kp10 or vehicle in a crossover experimental design with an interval of 1 week.

Ovariectomy.

Bilateral removal of ovaries from 6- to 8-week-old naive females was performed with isoflurane anesthesia. Briefly, the ventral skin was shaved and cleaned to perform two small incisions in the skin and abdominal musculature on both sides of the abdomen. Once the gonads were identified and excised, the muscle incisions were sutured and the skin was closed with surgical clips. One week later, the mice were killed by decapitation with anesthesia, trunk blood was collected for measurement of hormone levels, and brains were rapidly removed and frozen for in situ hybridization.

Sex steroid hormone replacement.

Estradiol capsules were prepared as previously described (Gill et al., 2012). In brief, Silastic capsules were filled with 20 μg/ml estradiol dissolved in sesame oil and were equilibrated in saline solution overnight at 37°C. A subgroup of ovariectomized Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (n = 6) and Leprlox/lox mice (n = 6) were implanted with estradiol capsules under anesthesia immediately after the bilateral ovariectomy procedure. The dorsal area of the neck was shaved and cleaned to perform a small incision. A subcutaneous pocket was bluntly dissected with ample space to introduce the estradiol capsule and the wound was closed with surgical clips. The mice were killed after 1 week as described for the ovariectomy procedure.

Hormone assays.

LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels were measured using a Milliplex MAP immunoassay (rat pituitary panel, Millipore) in the Luminex 200 (Singh et al., 2009).

In situ hybridization.

The brains were collected, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until sectioning. The brain sections (20 μm thick, 5 series) were mounted on SuperFrost plus slides (VWR Scientific). The Kiss1 and Tac2 mRNA probes were radiolabeled with 33P-UTP and the slides processed as described previously (Gottsch et al., 2004; Kauffman et al., 2009). The number of cells expressing Kiss1 or Tac2 was determined using ImageJ software (NIH). Kiss1 and Tac2 mRNA expression were assessed in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of ovariectomized animals, whereas Kiss1 mRNA was also analyzed in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus/periventricular nucleus continuum (AVPV/PeN) of ovariectomized females treated for 1 week with estradiol implants (20 μg/ml).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Intact adult (6- to 8-week-old) Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox and Leprlox/lox (in diestrus) females were killed and brains were collected. The hypothalamic tissue was sectioned using a coronal brain matrix (Braintree Scientific) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Briefly, the anteroventral periventricular nucleus/preoptic area (AVPV/POA) was dissected by coronal cuts located caudal to the optic chiasm and rostral to the mammillary bodies followed by two lateral cuts (1 mm thick each side) from the middle line and 2 mm from the dura (Brown et al., 2012). Total RNA from the AVPV/POA and ARC were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) followed by chloroform/isopropanol extraction. RNA was quantified using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and one microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR assays were performed on an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system, and analyzed using ABI Prism 7000 SDS software (Applied Biosystems). The cycling conditions were the following: 2 min incubation at 95°C (hot start), 45 amplification cycles (95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 45 s at 75°C, with fluorescence detection at the end of each cycle), followed by melting curve of the amplified products obtained by ramped increase of the temperature from 55 to 95°C to confirm the presence of single amplification product per reaction. The Kiss1r mRNA (primers: 5′-GGT GCT GGG AGA CTT CAT GT-3′, and 5′-ACA TAC CAG CGG TCC ACA CT-3′) was detected using SYBR green mix (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The data were normalized using cyclophilin (primers: 5′-CGA GCT CTG AGC ACT GGA GA-3′ and 5′-TGG CGT GTA AAG TCA CCA CC-3′) as an internal control, and expressed as fold-change relative to Leprlox/lox control.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 4. Data are shown as mean ± SEM and the significance level was set as p < 0.05. Differences were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t test or an ANOVA test followed by Bonferroni post hoc testing.

Results

Generation of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice

To elucidate the identity of leptin responsive neurons that modulate the activity of the HPG axis, we generated mice with selective deletion of leptin receptor in either GABAergic neurons (Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice) or glutamatergic neurons (Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice), as previously described (Vong et al., 2011). Mice were genotyped and female Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice were selected for reproductive phenotyping compared with Leprlox/lox control littermates (see Materials and Methods for details).

Metabolic and reproductive assessment of female Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice

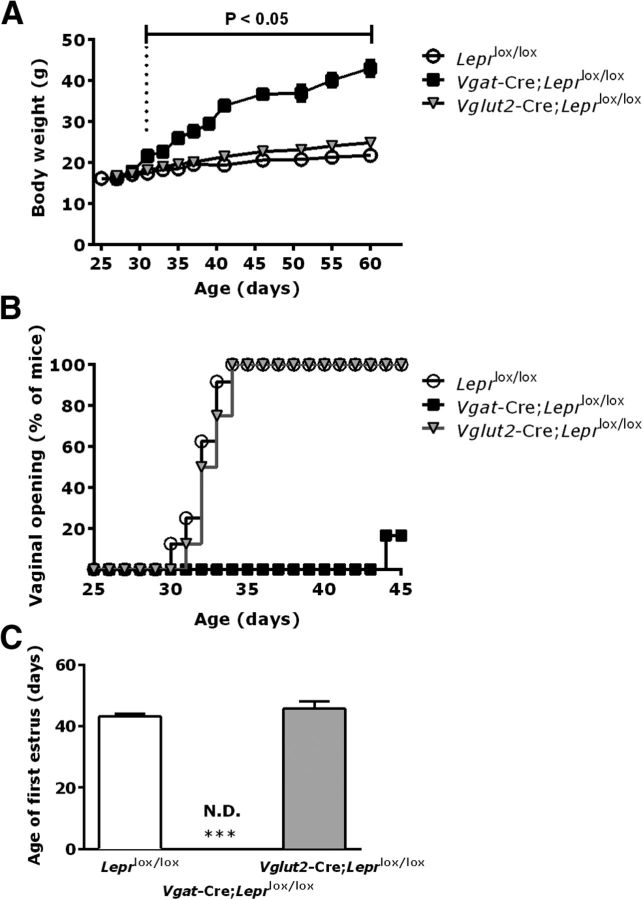

To determine whether the mouse models being studied had the expected metabolic phenotypes, all mice were weighed frequently from age 25–60 d. Female Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice exhibited a significantly greater body weight than Leprlox/lox control littermates beginning at PND30 (Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox 21.3 ± 1.2 g vs Leprlox/lox 17.9 ± 0.6 g; F(55) = 3.16, p = 0.0254; Fig. 1A). This increased body weight persisted and became even greater with increasing age (Fig. 1A). In contrast, female Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice showed a trend toward an increased body weight beginning at age 42 d, but did not reach significance when compared with Leprlox/lox control littermates during the time of the study (Fig. 1A). These findings are consistent with a previous report (Vong et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Leptin receptor deletion in GABAergic neurons impairs the onset of puberty in females. A, Body weight in female Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice (closed squares, n = 6) compared with Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice (gray triangles, n = 6) and respective Leprlox/lox control littermates (open circles, n = 6). Bracket indicates the age at which the body weight increase became statistically significant (p = 0.0254) for Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice. B, Age of VO for Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (n = 12), Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox (n = 6), and Leprlox/lox controls (n = 6), expressed as percentage of total mice for each genotype. C, Age of first estrus (n = 6 for each group). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparisons test. N.D., Not detected.

To assess the reproductive phenotype of these mice, we first monitored the age of vaginal opening (VO), reflecting increased circulating estradiol levels and used as an indirect biomarker of puberty onset. The Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females showed complete absence of VO at PND34 versus 100% of VO in Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox and control mice at the same age (Fig. 1B). After noticing that VO rarely occurred in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females, we increased the number of mutant animals (n = 12) to monitor for VO. Only a small subset (16.6%, 2 of 12) of these Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice displayed complete VO, with a marked delay of >2 weeks compared with control Leprlox/lox mice (47.4 ± 2.5 d vs 31.6 ± 1.0 d, respectively; Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the age of VO for Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox females (32.1 ± 1.0 d) was indistinguishable from their Leprlox/lox littermates (Fig. 1B). In addition, we measured the age of first estrus to determine the time of initiation of ovarian cycles. The mean age of first estrus was comparable in Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox and control Leprlox/lox mice (45.7 ± 2.5 d vs 43.0 ± 2.0 d, respectively, p = not significant) but first estrus was absent in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice (Fig. 1C). Of note, we ultimately screened several cohorts of mice to identify a total of six Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females with VO for assessment of estrous cyclicity.

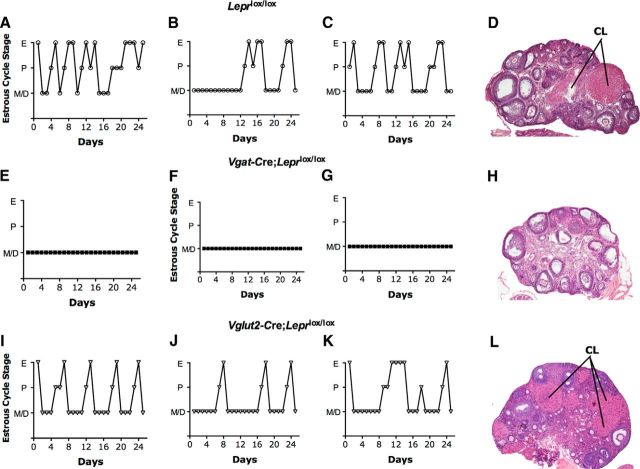

To further explore the integrity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, we monitored vaginal cytology to determine the pattern of estrous cycles for 25 d, beginning at 42 d of age. Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox and control Leprlox/lox mice both had normal estrous cycles, ∼4–5 d in duration (Fig. 2). We monitored vaginal cytology in the six Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females that had achieved complete VO. These females were acyclic, remaining in diestrus throughout the period of monitoring (Fig. 2). Consistent with the presence of regular estrous cycles, the ovarian histology of Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox and control Leprlox/lox mice (killed in diestrus) revealed numerous follicles at different stages of maturation, from primary follicles to antral follicles. In addition, multiple corpora lutea were present, confirming that ovulation had occurred (Fig. 2). In contrast, ovaries from Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox showed follicles at various stages of development (both healthy and atretic) but absent corpora lutea (Fig. 2), consistent with the absence of estrous cyclicity and consequently no ovulation.

Figure 2.

Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females are acyclic. Representative estrous cycle profiles from control Leprlox/lox (A–C), Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (E–G), and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox (I–K) mice. The estrous cycles were evaluated only in the subset of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females that had complete VO. The estrous cycles were divided into three stages as follows: estrus (E), proestrus (P), and metestrus/diestrus (M/D). In addition, representative images of ovarian H&E-stained cross-sections are shown from control Leprlox/lox (D), Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (H), and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox (L) mice. CL, Corpus luteum.

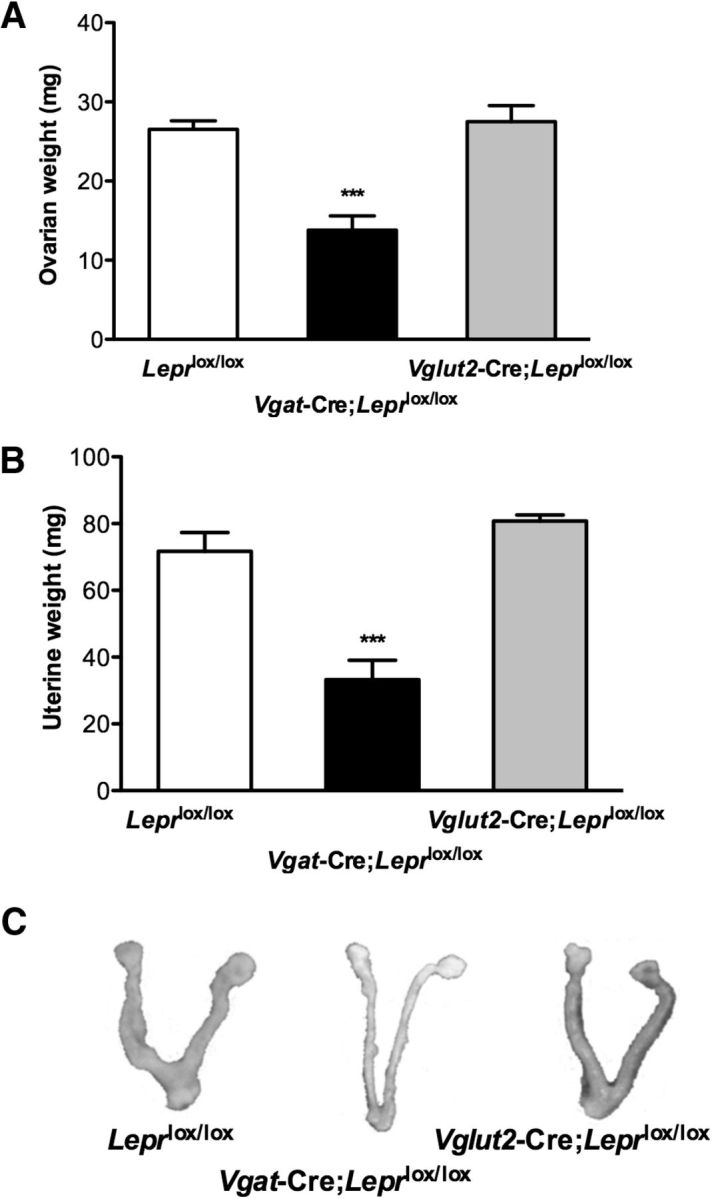

Consistent with the lack of VO in the majority of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice, the reproductive tracts from Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice were atrophic, with markedly decreased uterine (33.2 ± 5.8 mg) and ovarian (13.8 ± 1.8 mg) weights compared with Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox and control Leprlox/lox mice uteri (80.8 ± 1.8 mg and 71.7 ± 5.6 mg, respectively; F(2,17) = 28.81, p < 0.0001) and ovaries (27.5 ± 2.0 mg and 26.5 ± 1.0 mg, respectively: F(2,14) = 19.29, p < 0.0001) in diestrus (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females have reduced ovarian and uterine weights. A, Ovarian and (B) uterine weights of Leprlox/lox control mice (white bar, N = 10), Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice (black bar, N = 6), and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice (gray bar, N = 6). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparisons test. C, Representative pictures of uteri and ovaries from control Leprlox/lox, Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox, and Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice killed during diestrus at age 2 months.

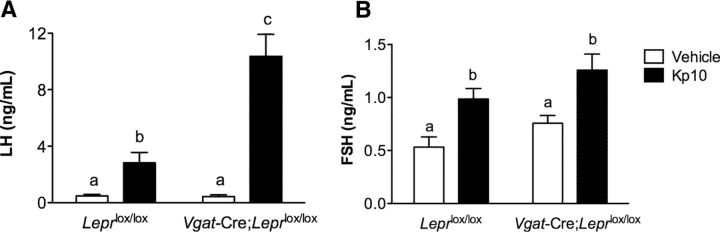

Response to central administration of kisspeptin-10 in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females

Based on the impaired pubertal maturation of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice, combined with their lack of estrous cyclicity and absence of ovarian corpora lutea (Figs. 1–3), we hypothesized that these mice, but not the Vglut2-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice, have impaired central activation of the HPG axis. Prior evidence that leptin acts centrally through impaired hypothalamic-pituitary function to cause reproductive defects provides further support for this hypothesis (Swerdloff et al., 1978; Cohen et al., 2001). The absence of leptin receptors in GnRH neurons (Quennell et al., 2009; Louis et al., 2011) suggests that the effect on the reproductive phenotype in the Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice occurs indirectly, through neurons upstream of the GnRH neurons. To test whether the GnRH system is intact in these animals, we injected 2-month-old Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice and control littermates (Leprlox/lox) centrally (intracerebroventricularly) with 1 nmol Kp10, the most potent activator of GnRH neurons identified to date (Gottsch et al., 2004), or vehicle (saline). Blood samples were collected 20 min postinjection for measurement of serum LH and FSH. As shown in Figure 4, the response of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females to kisspeptin was not only preserved, but was even augmented, with a robust 20-fold increase in serum LH levels (vehicle: 0.4 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs Kp10: 10.0 ± 1.8 ng/ml; t(12) = 6.24, p = 0.0005), and an almost twofold increase in FSH levels (vehicle: 0.7 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs Kp10: 1.3 ± 0.1 ng/ml; t(13) = 2.19, p = 0.0469), whereas the control Leprlox/lox group had only a sixfold increase in LH levels (vehicle: 0.5 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs Kp10: 3.2 ± 0.9 ng/ml; t(12) = 2.73, p = 0.0182), together with a twofold increase in FSH levels (vehicle: 0.5 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs Kp10: 1.0 ± 0.1 ng/ml; t(12) = 3.12, p = 0.0089). Moreover, the magnitude of LH response to Kp10 stimulus was significantly increased in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females compared with Leprlox/lox females (Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox 10.0 ± 1.8 ng/ml vs Leprlox/lox: 3.2 ± 0.9 ng/ml; F(1,23) = 16.63, p = 0.0005), whereas FSH levels remain unaffected (Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox: 1.3 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs Leprlox/lox: 1.0 ± 0.1 ng/ml; F(1,18) = 0.05, p = N.S.). These results confirm that GnRH neuronal and gonadotrope function are intact, and suggest that the defect is upstream of GnRH neurons.

Figure 4.

Increased LH response to central administration of kisspeptin in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females. A, Serum LH and (B) serum FSH levels 20 min after central intracerebroventricular injection of Kp10 (black bars) or vehicle (white bars) using a crossover experimental design with a 1 week interval in Leprlox/lox (n = 6) and Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (n = 6) female mice. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Lowercase letters a–c above the bars indicates statistically significant differences among groups (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by the Student-Newman–Keuls multiple range test).

It is plausible to attribute the augmented response to kisspeptin in the Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females to a compensatory increase in kisspeptin receptor (Kiss1r) levels, as previously described in states of negative energy balance (Castellano et al., 2005). To investigate this premise, we collected hypothalamic tissue from the preoptic area, where GnRH neurons expressing Kiss1r are located, from intact adult females (Leprlox/lox females were killed in diestrus) and quantified the Kiss1r gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR. We found no significant difference in Kiss1r mRNA levels in the preoptic area (p = 0.3014, data not shown), suggesting that other mechanisms were responsible for the augmented kisspeptin response.

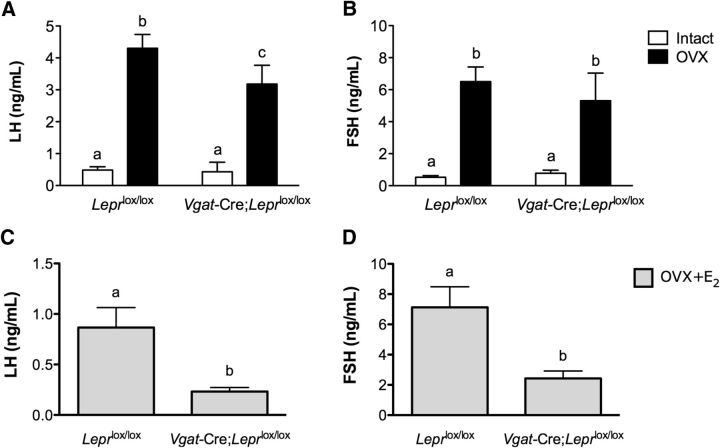

The effects of ovariectomy and of estrogen replacement on serum gonadotropins in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice

To further explore the reproductive role of GABAergic leptin responsive neurons, we investigated the ability of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice to respond to the negative feedback effects of sex steroids. To this end, we ovariectomized (OVX) 6- to 8-week-old Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females and their corresponding control littermates and replaced them with either empty capsules or with capsules filled with estradiol (20 μg/ml). One week after surgery, blood samples were collected and serum LH and FSH levels were measured. Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females were able to respond to ovariectomy with a compensatory rise in serum LH levels (intact 0.4 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs OVX 3.2 ± 0.2 ng/ml; t(12) = 5.08, p = 0.0003), as did control Leprlox/lox females (intact 0.5 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs OVX 4.3 ± 0.4 ng/ml; t(10) = 8.63, p < 0.0001). Similarly, the Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice responded to ovariectomy with an increase in serum FSH levels (intact 0.8 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs OVX 5.3 ± 0.7 ng/ml; t(12) = 7.42, p < 0.0001), as did Leprlox/lox females (intact 0.5 ± 0.1 ng/ml vs OVX 6.5 ± 0.9 ng/ml; t(11) = 7.08, p < 0.0001; Fig. 5A,B). Interestingly, the extent of the LH response to OVX in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females was significantly reduced compared with control Leprlox/lox littermates (Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox 3.2 ± 0.2 ng/ml vs Leprlox/lox 4.3 ± 0.4 ng/ml; F(1,20) = 5.14, p = 0.0346).

Figure 5.

The compensatory increase in gonadotropins in response to bilateral ovariectomy is reduced in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females. A, Serum LH and (B) Serum FSH levels prior (white bars) and 1 week after OVX (black bars) in Leprlox/lox (n = 6) and Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (n = 6) mice. Lowercase letters a–c above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among groups (two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparisons test). C, Serum LH and (D) Serum FSH levels 1 week after OVX and estradiol replacement in Leprlox/lox (n = 6) and Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (n = 6) mice. Lowercase letters a and b above the bars indicate statistically significant differences between groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparisons test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

The previous experiment showed a significantly reduced ability of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox animals to respond to the lack of circulating sex steroids. To expand the characterization of the negative feedback in these mice, an additional set of OVX and estradiol-replaced (OVX + E2) animals was compared. In this experiment, plasma LH and FSH levels were significantly reduced in both Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice and littermate controls (p < 0.0001, data not shown) after estradiol treatment, compared with OVX mice. Importantly, E2-treated Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females had significantly lower LH and FSH levels compared with their corresponding controls (LH: Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox 0.23 ± 0.03 ng/ml vs Leprlox/lox 0.9 ± 0.2 ng/ml, t(8) = 3.84, p = 0.0049; FSH: Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox 2.4 ± 0.5 ng/ml vs Leprlox/lox 7.13 ± 1.3 ng/ml, t(10) = 3.25, p = 0.0086; Fig. 5C,D).

Hypothalamic Kiss1 and Tac2 expression in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females

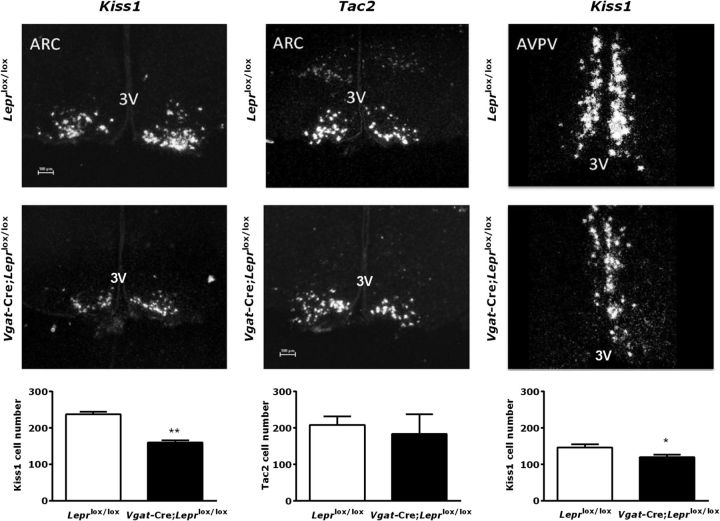

In the previous experiment, Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice had lower serum LH levels after gonadectomy compared with controls (Fig. 5A). Previous reports in food deprived rats and leptin deficient (ob/ob) mice showed a significant reduction in hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA levels in the arcuate nucleus (ARC). These findings correlated with reduced LH secretion under these conditions, implying that leptin may act as an upstream regulator of Kiss1 gene expression (Castellano et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2006; Quennell et al., 2011). To investigate whether the decreased LH response to ovariectomy observed in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice is mediated by an impaired response of kisspeptin neurons to the negative feedback of sex steroids, we analyzed by in situ hybridization the mRNA levels of two key players in the ARC, the hypothalamic area suggested as key to the negative feedback of sex steroids in the control of the tonic GnRH secretion: kisspeptin (Kiss1) and its cotransmitter, neurokinin B (Tac2). The numbers of cells in the ARC expressing Kiss1 and Tac2 were quantified 1 week post-OVX in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox and control Leprlox/lox mice, based on previous reports indicating maximal expression of Kiss1 and Tac2 in the ARC in the absence of circulating estradiol (Smith et al., 2005a; Kauffman et al., 2009). We found a significantly lower number of Kiss1-expressing neurons in the ARC (160.1 ± 6.2 cells; t(4) = 7.90, p = 0.0014) of Vgat-Cre; Leprlox/lox females compared with control Leprlox/lox littermates (237.3 ± 7.5 cells). In contrast, the number of Tac2-expressing cells in the ARC remained unaltered between Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox and control Leprlox/lox mice (183.7 ± 54.6 cells vs 208.3 ± 23.8 cells, respectively; p = n.s.; Fig. 6, left, middle).

Figure 6.

Reduced expression of ARC and AVPV/PeN Kiss1 mRNA, but not ARC Tac2 mRNA, in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice. mRNA levels of Kiss1 (left), along with mRNA expression of Tac2 (middle) in the ARC after 1 week ovariectomy, and Kiss1 (right) in the AVPV/PeN of ovariectomized females treated with 20 μg/ml of estrogen determined by in situ hybridization. A representative microphotograph of control Leprlox/lox (top, n = 4) and Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox (middle, n = 3) mice is shown along with the quantification of positive cell numbers (bottom) for each respective gene. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; *p = 0.0453, **p = 0.0014 by unpaired t test. Scale bar, 100 μm.

In addition, we measured the expression of Kiss1 mRNA in the AVPV/PeN, a suggested mediator of the positive feedback of E2 in the female (Smith et al., 2005a). We performed these measurements in OVX, E2-replaced mice, based on previous reports indicating maximal expression of Kiss1 in the AVPV/PeN following estradiol treatment (Smith et al., 2005a). Of note, Tac2 is not expressed in this nucleus (Navarro et al., 2009), and therefore was not assessed in this experiment. We found that the Kiss1 expression in the AVPV was significantly lower in OVX, E2-replaced Vgat-Cre; Leprlox/lox females than in control Leprlox/lox littermates (120.0 ± 6.3 cells vs 146.0 ± 9.7 cells, respectively; t(8) = 2.37, p = 0.0453; Fig. 6, right).

Discussion

Despite the undeniable influence of leptin signaling in reproduction, the identity of first-order leptin-responsive neurons that regulate reproductive function remains elusive. GnRH neurons do not express leptin receptor (Quennell et al., 2009; Louis et al., 2011), suggesting that leptin acts upstream of GnRH neurons. Moreover, mice with genetic ablation of the leptin receptor in kisspeptin neurons remained fertile (Donato et al., 2011), indicating that the reproductive actions of leptin may also lie upstream of kisspeptin neurons. In this work, we present compelling evidence indicating an essential role of GABAergic, but not glutamatergic, neurons in the reproductive role of leptin in females. We found that female mice lacking functional leptin receptors in GABAergic neurons (Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice) have hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, similar to leptin-deficient (ob/ob) and resistant (db/db) mice (Swerdloff et al., 1978; de Luca et al., 2005; Israel and Chua, 2010; Harno et al., 2013). These mice displayed small, immature ovaries and absent corpora lutea, reflecting ovarian failure and anovulation.

Increasing numbers of reports reveal pitfalls in the Cre-lox technology leading to unintended experimental outcomes (Harno et al., 2013). However, it is unlikely that the Vgat-Cre;leprlox/lox reproductive phenotype is driven by Cre recombinase expression itself, because heterozygous Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/WT females and males are fertile and have a similar body weight to Leprlox/lox mice. Together, these observations suggest that the genetic modification itself is not likely to account for the observed phenotype.

A direct (leptin-independent) effect of obesity on fertility must also be considered (Lane and Dickie, 1958; Pasquali et al., 2007). However, previous studies in leptin deficient rodents and humans have shown that weight loss per se is not sufficient to restore reproduction without exogenous leptin administration (Ahima et al., 1996; Chehab et al., 1996; Mounzih et al., 1997; Gonzalez et al., 1999; Farooqi, 2002). Additionally, in our studies, at the age of puberty onset in control mice, all groups had similar body weights, further excluding body weight as the primary contributing factor for their reproductive incompetence. We cannot exclude a potential contribution of the genetic background to the severity of the infertility phenotype (Elias and Purohit, 2013). The ob/ob mice crossed onto a BALB/cJ background have been shown to have a milder reproductive phenotype despite being obese to a similar extent as ob/ob mice in the C57BL/6 background (Ewart-Toland et al., 1999), further supporting the notion that obesity is not a major contributor to the infertile phenotype in leptin-deficient mice (Qiu et al., 2001).

The central deficiency of gonadotropin secretion resulting from a leptin signaling defect (Swerdloff et al., 1978) would be expected to result in insufficient ovarian stimulation during postnatal development, thereby resulting in failure to undergo sexual maturation, i.e., puberty. This is consistent with the phenotype observed in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox female mice, which exhibit hypogonadism accompanied by a delay or absence of VO and absent estrous cycles, in keeping with the reported permissive action of leptin for puberty onset. This suggests that pubertal maturation is mediated, at least in part, via GABAergic neurons in the female mouse. While this paper was under review, similar findings were reported (Zuure et al., 2013). Together, these findings demonstrate the critical role of leptin-responsive GABAergic neurons in puberty and fertility.

The onset of puberty requires the reactivation of GnRH neurons (whose embryonic and postnatal development is independent of leptin; Elias, 2012) after a prolonged period of quiescence (Terasawa and Fernandez, 2001). Kisspeptin secretion is essential for pubertal progression (de Roux et al., 2003; Seminara et al., 2003), and changes in kisspeptin tone induce changes in the timing of puberty onset in rodents and humans (Navarro et al., 2004; Silveira et al., 2013). Interestingly, we found that the genetic ablation of leptin receptors in GABAergic neurons compromises the expression of ARC and AVPV Kiss1 mRNA in female mice, consistent with previous reports in ob/ob mice (Smith et al., 2006; Quennell et al., 2011), which may contribute to the absence of puberty onset and lack of estrous cyclicity observed. Kisspeptin has been suggested to play an important role as a conduit of metabolic function to GnRH neurons (Pinilla et al., 2012). First, Kiss1 expression is significantly reduced in food-deprived rats (Castellano et al., 2005) and in ob/ob mice (Smith et al., 2006) as well as in Zucker (fa/fa) rats (Navarro et al., 2004). Second, exogenous leptin administration to leptin-deficient rodents increased Kiss1 expression (Smith et al., 2006), suggesting a higher hierarchical level of leptin action. Consistent with these previous studies, kisspeptin administration to Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox females in our experiments resulted in robust stimulation of LH release. The ability of these mice to respond to kisspeptin was not only preserved, but also significantly augmented compared with their controls, indicating that GnRH neurons and gonadotropes are intact and able to respond to the kisspeptin stimulus. This effect is reminiscent of the previously reported actions of kisspeptin in conditions of negative energy balance (Castellano et al., 2005). One possible explanation for the hypersensitivity to kisspeptin in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice is that there is lower constitutive exposure of these animals to kisspeptin, leading to reduced tachyphylaxis of the receptor. Kiss1r expression was similar, but we cannot exclude the possibility that leptin signaling may modify kisspeptin receptors at the protein level, such as by changes in protein synthesis, post-translational modifications, or receptor trafficking.

Kisspeptin neurons mediate sex steroid action upon GnRH release. We observed that Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice still respond to gonadectomy by increasing LH levels and Kiss1 expression in the ARC, although at a significantly lower level than controls. Moreover, estradiol replacement reduced LH release in both groups. Of note, the LH levels of estradiol-treated Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice were significantly lower than controls; however, they started from significantly reduced LH levels (as seen in OVX and sham-replaced animals), indicating an overall equivalent magnitude of the inhibitory action of sex steroids. These findings are consistent with the sensitivity to feedback inhibition observed in ob/ob mice (Swerdloff et al., 1976; Batt et al., 1982). Altogether, these data suggest the presence of circulating sex steroids in these animals that are capable of inducing negative feedback, and that other sex-steroid independent factors contribute to the impaired increase in LH following ovariectomy.

Sex steroids also play a critical role in the female to induce ovulation through positive feedback mechanisms that are believed to occur at the level of AVPV kisspeptin neurons (Smith et al., 2005b). Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice had decreased levels of AVPV Kiss1 expression after estradiol replacement. We hypothesize that these reduced levels reflect compromised positive feedback effects of estradiol, which may suggest impairment in the ovulatory GnRH surges. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of corpora lutea in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice, indicating anovulation. These findings are also consistent with a previous report of impaired AVPV kisspeptin neuronal activation in response to a GnRH surge-inducing protocol in a neuron-specific leptin receptor-deficient mouse model (Quennell et al., 2011).

Despite the colocalization of NKB and kisspeptin in the ARC and the stimulatory effects of both neuropeptides on gonadotropin release (Lehman et al., 2010), we found differences in the regulation of Kiss1 and Tac2 expression in the Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice, not seen in their control littermates. Kiss1, but not Tac2, mRNA expression in the ARC was reduced in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox OVX females. These findings suggest independent regulatory pathways for these cotransmitters, as previously suggested (Gill et al., 2012).

We have presented a series of physiological and pharmacological studies that unveil a pivotal role of GABAergic neurons in the reproductive actions of leptin. Interestingly, we found a parallelism in the reproductive and metabolic phenotypes of Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice, indicating that leptin action via GABAergic networks reduces the inhibitory tone not only in POMC neurons (obesogenic effect; Vong et al., 2011), but also on upstream circuits impinging on GnRH regulation (Zuure et al., 2013). These unexpected findings may appear contradictory to recent studies that identified the ventral premammillary nucleus (PMV), predominantly populated by glutamatergic (excitatory) neurons, as direct reproductive targets of leptin action (Donato et al., 2011). However, it is important to consider developmental adaptations that may result from the removal of leptin-responsive GABAergic neurons to disrupt the balance of excitatory and inhibitory inputs to GnRH neurons (Elias and Purohit, 2013). Further investigation is needed to fully elucidate the contribution of PMV neurons as major integrators of metabolic influence on reproductive function. The GABA-mediated contribution to the permissive role of leptin for reproduction is consistent with previous reports in the monkey suggesting that a prepubertal decrease in GABAergic tone precedes the reawakening of GnRH pulses at the time of puberty onset, mediated at least in part, by kisspeptin neurons (Kurian et al., 2012). The future identification of the leptin-responsive GABAergic neurons will further improve our understanding of the nature of this reproductive/metabolic circuit.

In summary, the present work expands our knowledge of the mechanism of action of leptin to regulate reproductive function. This action is predominantly mediated by GABAergic neurons, possibly as result of decreased inhibitory GABAergic output in response to leptin signaling. In contrast, the role of leptin-responsive glutamatergic neurons (with predominantly stimulatory actions) appears secondary, perhaps involved in fine-tuning control of kisspeptin and/or GnRH release. Our findings strongly suggest that the reduction of the inhibitory tone necessary for the progression to puberty is disrupted in Vgat-Cre;Leprlox/lox mice, and that this effect is mediated, at least in part, through modulatory effects on kisspeptin neurons.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through cooperative agreement U54HD028138 as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research, and by Grants R21HD066495 and R01HD019938 to U.B.K., by R01DK089044, P30DK046200, and P30DK057521 to B.B.L., by K99HD071970 to V.M.N., and by T32DK007529 and R21HD066495-S1 and the Microgrant Program from The Biomedical Research Institute and the Center for Faculty Development and Diversity's Office for Research Careers at the Brigham and Women's Hospital to C.M. We thank Kaiser Laboratory members for helpful discussions, as well as Shuyun Xu and Zongfang Yang for technical support and valuable comments on the development of this work, and Dr Andrew Wolfe for assistance with LH and FSH hormone measurements, and the Harvard Medical School Rodent Pathology Core.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996;382:250–252. doi: 10.1038/382250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua SC, Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2004;42:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash IA, Cheung CC, Weigle DS, Ren H, Kabigting EB, Kuijper JL, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Leptin is a metabolic signal to the reproductive system. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3144–3147. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batt RA, Everard DM, Gillies G, Wilkinson M, Wilson CA, Yeo TA. Investigation into the hypogonadism of the obese mouse (genotype ob/ob) J Reprod Fertil. 1982;64:363–371. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0640363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Wilkinson DA, Imran SA, Caraty A, Wilkinson M. Hypothalamic kiss1 mRNA and kisspeptin immunoreactivity are reduced in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Brain Res. 2012;1467:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano JM, Navarro VM, Fernández-Fernández R, Nogueiras R, Tovar S, Roa J, Vazquez MJ, Vigo E, Casanueva FF, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Dieguez C, Tena-Sempere M. Changes in hypothalamic KiSS-1 system and restoration of pubertal activation of the reproductive axis by kisspeptin in undernutrition. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3917–3925. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab FF. Leptin as a regulator of adipose mass and reproduction. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:309–314. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab FF, Lim ME, Lu R. Correction of the sterility defect in homozygous obese female mice by treatment with the human recombinant leptin. Nat Genet. 1996;12:318–320. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CC, Thornton JE, Kuijper JL, Weigle DS, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Leptin is a metabolic gate for the onset of puberty in the female rat. Endocrinology. 1997;138:855–858. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.2.5054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Zhao C, Cai X, Montez JM, Rohani SC, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Friedman JM. Selective deletion of leptin receptor in neurons leads to obesity. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1113–1121. doi: 10.1172/JCI13914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DL. Obese and diabetes: two mutant genes causing diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetologia. 1978;14:141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00429772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Luca C, Kowalski TJ, Zhang Y, Elmquist JK, Lee C, Kilimann MW, Ludwig T, Liu SM, Chua SC., Jr Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuron-specific LEPR-B transgenes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3484–3493. doi: 10.1172/JCI24059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10972–10976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834399100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato J, Jr, Cravo RM, Frazão R, Gautron L, Scott MM, Lachey J, Castro IA, Margatho LO, Lee S, Lee C, Richardson JA, Friedman J, Chua S, Jr, Coppari R, Zigman JM, Elmquist JK, Elias CF. Leptin's effect on puberty in mice is relayed by the ventral premammillary nucleus and does not require signaling in Kiss1 neurons. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:355–368. doi: 10.1172/JCI45106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias CF. Leptin action in pubertal development: recent advances and unanswered questions. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias CF, Purohit D. Leptin signaling and circuits in puberty and fertility. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:841–862. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart-Toland A, Mounzih K, Qiu J, Chehab FF. Effect of the genetic background on the reproduction of leptin-deficient obese mice. Endocrinology. 1999;140:732–738. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi IS. Leptin and the onset of puberty: insights from rodent and human genetics. Semin Reprod Med. 2002;20:139–144. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch RE. Fatness, menarche, and female fertility. Perspect Biol Med. 1985;28:611–633. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1985.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta M, Funabashi T, Kimura F. Intracerebroventricular administration of ghrelin rapidly suppresses pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in ovariectomized rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:780–785. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill JC, Navarro VM, Kwong C, Noel SD, Martin C, Xu S, Clifton DK, Carroll RS, Steiner RA, Kaiser UB. Increased neurokinin B (Tac2) expression in the mouse arcuate nucleus is an early marker of pubertal onset with differential sensitivity to sex steroid-negative feedback than Kiss1. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4883–4893. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez LC, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M, Aguilar E. Leptin(116–130) stimulates prolactin and luteinizing hormone secretion in fasted adult male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;70:213–220. doi: 10.1159/000054479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottsch ML, Cunningham MJ, Smith JT, Popa SM, Acohido BV, Crowley WF, Seminara S, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. A role for kisspeptins in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4073–4077. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harno E, Cottrell EC, White A. Metabolic pitfalls of CNS Cre-based technology. Cell Metab. 2013;18:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp K, Mika C, Grzella I, Heer M, Pak H, Hebebrand J, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Reproductive function during weight gain in anorexia nervosa: leptin represents a metabolic gate to gonadotropin secretion. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0800-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel D, Chua S., Jr Leptin receptor modulation of adiposity and fertility. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman AS, Navarro VM, Kim J, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Sex differences in the regulation of Kiss1/NKB neurons in juvenile mice: implications for the timing of puberty. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E1212–1221. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00461.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, Keen KL, Guerriero KA, Terasawa E. Tonic control of kisspeptin release in prepubertal monkeys: implications to the mechanism of puberty onset. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3331–3336. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane PW, Dickie MM. The effect of restricted food intake on the life span of genetically obese mice. J Nutr. 1958;64:549–554. doi: 10.1093/jn/64.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL. Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3479–3489. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis GW, Greenwald-Yarnell M, Phillips R, Coolen LM, Lehman MN, Myers MG., Jr Molecular mapping of the neural pathways linking leptin to the neuroendocrine reproductive axis. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2302–2310. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantzoros CS, Magkos F, Brinkoetter M, Sienkiewicz E, Dardeno TA, Kim SY, Hamnvik OP, Koniaris A. Leptin in human physiology and pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E567–E584. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00315.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMinn JE, Liu SM, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P, Ludwig T, Eiden S, Chua SC., Jr An allelic series for the leptin receptor gene generated by CRE and FLP recombinase. Mamm Genome. 2004;15:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR. An Fgf8 mutant allelic series generated by Cre- and Flp-mediated recombination. Nat Genet. 1998;18:136–141. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounzih K, Lu R, Chehab FF. Leptin treatment rescues the sterility of genetically obese ob/ob males. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1190–1193. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Fernández-Fernández R, Castellano JM, Roa J, Mayen A, Barreiro ML, Gaytan F, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Dieguez C, Tena-Sempere M. Advanced vaginal opening and precocious activation of the reproductive axis by KiSS-1 peptide, the endogenous ligand of GPR54. J Physiol. 2004;561:379–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Chavkin C, Okamura H, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion by kisspeptin/dynorphin/neurokinin B neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11859–11866. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali R, Patton L, Gambineri A. Obesity and infertility. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2007;14:482–487. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282f1d6cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla L, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, Millar RP, Tena-Sempere M. Kisspeptins and reproduction: physiological roles and regulatory mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1235–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Ogus S, Mounzih K, Ewart-Toland A, Chehab FF. Leptin-deficient mice backcrossed to the BALB/cJ genetic background have reduced adiposity, enhanced fertility, normal body temperature, and severe diabetes. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3421–3425. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quennell JH, Mulligan AC, Tups A, Liu X, Phipps SJ, Kemp CJ, Herbison AE, Grattan DR, Anderson GM. Leptin indirectly regulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal function. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2805–2812. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quennell JH, Howell CS, Roa J, Augustine RA, Grattan DR, Anderson GM. Leptin deficiency and diet-induced obesity reduce hypothalamic kisspeptin expression in mice. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1541–1550. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer DA, Amico JA, Cameron JL. Reversal of fasting-induced suppression of luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in male rhesus monkeys by intragastric nutrient infusion: evidence for rapid stimulation of LH by nutritional signals. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1890–1897. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.5.8477642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS, Jr, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Kaiser UB, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF, O'Rahilly S, Carlton MB, Crowley WF, Jr, Aparicio SA, Colledge WH. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1614–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira LG, Latronico AC, Seminara SB. Kisspeptin and clinical disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;784:187–199. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6199-9_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Wolfe A, Ng Y, DiVall SA, Buggs C, Levine JE, Wondisford FE, Radovick S. Impaired estrogen feedback and infertility in female mice with pituitary-specific deletion of estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) Biol Reprod. 2009;81:488–496. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Dungan HM, Stoll EA, Gottsch ML, Braun RE, Eacker SM, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Differential regulation of KiSS-1 mRNA expression by sex steroids in the brain of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2005a;146:2976–2984. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Cunningham MJ, Rissman EF, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the female mouse. Endocrinology. 2005b;146:3686–3692. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Acohido BV, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. KiSS-1 neurones are direct targets for leptin in the ob/ob mouse. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdloff RS, Batt RA, Bray GA. Reproductive hormonal function in the genetically obese (ob/ob) mouse. Endocrinology. 1976;98:1359–1364. doi: 10.1210/endo-98-6-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdloff RS, Peterson M, Vera A, Batt RA, Heber D, Bray GA. The hypothalamic-pituitary axis in genetically obese (ob/ob) mice: response to luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1978;103:542–547. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-2-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E, Fernandez DL. Neurobiological mechanisms of the onset of puberty in primates. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:111–151. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.1.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Herck H, Baumans V, Brandt CJ, Hesp AP, Sturkenboom JH, van Lith HA, van Tintelen G, Beynen AC. Orbital sinus blood sampling in rats as performed by different animal technicians: the influence of technique and expertise. Lab Anim. 1998;32:377–386. doi: 10.1258/002367798780599794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vong L, Ye C, Yang Z, Choi B, Chua S, Jr, Lowell BB. Leptin action on GABAergic neurons prevents obesity and reduces inhibitory tone to POMC neurons. Neuron. 2011;71:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welt CK, Chan JL, Bullen J, Murphy R, Smith P, DePaoli AM, Karalis A, Mantzoros CS. Recombinant human leptin in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:987–997. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuure WA, Roberts AL, Quennell JH, Anderson GM. Leptin signaling in GABA neurons, but not glutamate neurons, is required for reproductive function. J Neurosci. 2013;33:17874–17883. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2278-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]