Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a questionnaire used to assess the level of general knowledge about cervical cancer, its primary and secondary prevention, and to identify sources of information about the disease among schoolgirls and female students.

Methods

The questionnaire development process was divided into four phases: generation of issues; construction of a provisional questionnaire; testing of the provisional questionnaire for acceptability and relevance; field-testing, which aimed at ensuring reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Field-testing included 305 respondents of high school female Caucasian students, who filled out the final version of the questionnaire.

Results

After phase 1, a list of 65 issues concerning knowledge about cervical cancer and its prevention was generated. Of 305, 155 were schoolgirls (mean age±SD, 17.8±0.5) and 150 were female students (mean age±SD, 21.7±1.8). The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the whole questionnaire was 0.71 (range for specific questionnaire sections, 0.60 to 0.81). Test-retest reliability ranged from 0.89 to 0.94.

Conclusion

The Cervical-Cancer-Knowledge-Prevention-64 has been successfully developed to measure the level of knowledge about cervical cancer. The results confirm the validity, reliability and applicability of the created questionnaire.

Keywords: Cancer prevention, Cervical cancer, Knowledge, Students, Questionnaire validation

INTRODUCTION

Although cervical cancer is considered to be a preventable health problem, each year nearly 530,000 women worldwide contract the disease. At the same time almost 275,000 women die from cervical cancer [1]. This makes cervical cancer the second most common cancer and third in terms of cancer-caused deaths among women suffering from gynecologic neoplasms worldwide [2]. Cervical cancer, more than any other major cancer, affects mostly women under 50 years of age [3]. Taking into consideration the fact that cervical cancer mortality rate in Poland is one of the highest in Europe [4], it is easy to understand that prophylaxis and early detection play a vital role. However, to implement preventive tools, women must be aware of the seriousness of the problem. Therefore, there is a need to obtain accurate data on the current knowledge of women about cervical cancer. All these efforts are aimed at launching campaigns that would encourage human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and cytological examination.

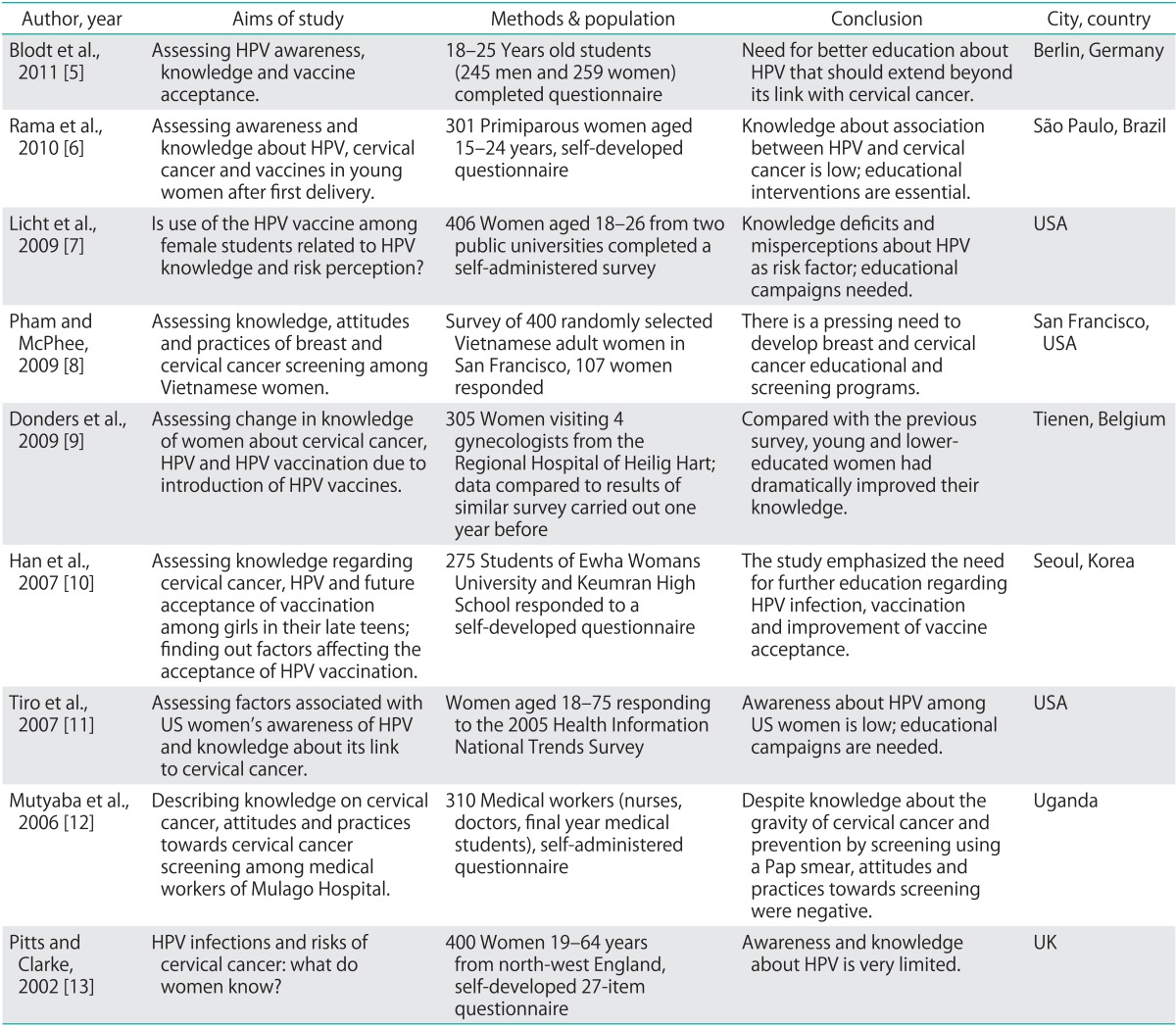

A number of studies trying to assess knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer have already been conducted (Table 1) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Unfortunately, recent studies show that public awareness of the subject of cervical cancer is insufficient [14]. Regardless of country or continent, there is a pressing need for wider and better education on the subject of HPV infection, as well as cervical cancer screening and prevention. Young women with low education and poor economic background should be the first line target for educational campaigns on the above mentioned subjects.

Table 1.

Review of studies concerning knowledge assessment on the subject of cervical cancer

HPV, human papillomavirus.

To the author's best knowledge, there is only one study that presents the development and validation of a questionnaire assessing women's beliefs about cervical cancer and Pap test [15]. The aim of this study was to develop and test a questionnaire that would adequately assess the knowledge about cervical cancer and its prevention among female students and schoolgirls. Our questionnaire focused on the problem of education and social awareness about cervical cancer. In this paper, we report the first three phases of the development of the questionnaire as well as the results of a large field test.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The creation of the questionnaire, Cervical-Cancer-Knowledge-Prevention-64 (CCKP-64), was based on the adapted European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Group guidelines for questionnaire development [16]. In short, the development process was divided into four phases aimed at ensuring reliability and validity. However, there are some important differences between the methodology of the current study and the EORTC guidelines [16]. CCKP-64 questionnaire was primarily targeted at the Polish population using a standardized tool. The EORTC guidelines state that 4 phases of questionnaire construction and testing should include multiple countries to ensure cross-cultural consistency. However, in the case of this study, only after the questionnaire was developed it became obvious that cross-cultural adaptation can make the questionnaire useful in an international setting. The EORTC module development guidelines also state that the initial questionnaire should be developed in English. This was not the case as the initial study population needed the questionnaire in Polish.

The study was approved by the Jagiellonian University Medical College Bioethics Committee (Decision No. KBET/251/B/2011). All participants (female Caucasians) gave their informed consent prior to inclusion into this study.

1. Phase 1: generation of issues

The aim of phase 1 was to generate issues concerning the subject of cervical cancer and its prevention. First, a literature search was conducted on Medline (1966-2011) using the following keywords: cervical cancer, knowledge, prevention, vaccine, HPV. Secondly, interviews with schoolgirls (n=11; age range, 17 to 18 years) and female students (n=11; age range, 19 to 26) were performed. During the interview, the respondents were asked to describe their experience concerning cervical cancer and its prevention and were allowed to provide information freely. Interviews were continued until new issues ceased arising. Thirdly, a list of 119 generated issues was presented to 14 healthcare professionals (HCPs; 6 clinical oncologists, 4 radiation oncologists, 3 gynecologists, and 1 general practitioner), 8 female students (age range, 20 to 22 years) and 8 schoolgirls (age range, 17 to 18 years). The respondents were asked to assess the relevance of each issue on a 4-point Likert scale (1, not relevant; 4, very relevant). They were also asked to select 30-40 issues to be definitely included in the questionnaire.

The following criteria were used to select issues that would form the item list in phase 2: mean score at least 2.5; range of responses at least two points, e.g., 1-3 or 2-4; prevalence ratio at least 30%; at least one-third of patients or health care professionals prioritizing the item. Issues were retained if they met at least two out of three of the above criteria. The scores were considered in conjunction with patient comments made during interviews. The issue list was reviewed for overlap between issues.

2. Phase 2: construction of a provisional questionnaire

The aim of phase 2 was to form a provisional questionnaire based on the issue list generated in phase 1. Out of 119 issues 65 met the above mentioned criteria. These were phrased into questions (items) and formed into sections based on item relevance by the research team. The provisional questionnaire was reviewed by two experts in medical oncology (both professors, PhDs in medical oncology) to ensure breadth of coverage and appropriate wording.

3. Phase 3: testing of the provisional questionnaire for acceptability and relevance

Phase 3 identified problems relating to the wording and clarity of items, and determined the need to add or delete items. The provisional module was tested in additional 10 female students and 10 schoolgirls. Women were asked to complete the provisional questionnaire indicating if they found any questions annoying, confusing, upsetting or intrusive, and if so, they were asked to rephrase the question. Patients were also asked whether any questions were irrelevant or whether there were additional issues that were not included in the module.

Patients' comments (general remarks, difficult wording or language) were taken into consideration when making decisions for retaining or deleting items. Final item wording was achieved after discussion between all co-authors.

4. Phase 4: field-testing

The aim of phase 4 was to determine the acceptability and reliability of the created questionnaire. As the final version consisted of 64 questions (3 concerning demographic data, the number of respondents needed in this phase was calculated to be equal to 305, based on the theory of Tabachnik and Fidell [17], which considers that in order to obtain reliable estimates through multivariate analysis, the number of observations should be 5-10 times the number of variables in the model. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach alpha coefficient, in which estimates of 0.70 or greater were considered acceptable for group comparisons [18]. Test-retest reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using interclass correlations (ICC) between baseline and retest assessments 2 weeks later. A correlation>0.80 was considered acceptable [19]. Respondents who were chosen for the retest group were not informed about the correct answers after completing the questionnaire for the first time.

RESULTS

1. Phase 1: generation of issues

To the authors' best knowledge, there is only one standardized questionnaire assessing women's knowledge on the subject of cervical cancer and its prevention exists [15]. Quantitative analysis (mean scores, range, prevalence, and proportions of priority ratings) of both HCPs and female respondents' interviews resulted in the deletion of 54 issues.

2. Phase 2: construction of a provisional questionnaire

Out of 119 issues generated in phase 1, 65 met the phase 2 criteria. These were phrased into items and formed into sections based on item relevance by the research team. The provisional questionnaire was reviewed and approved by two experts in medical oncology to ensure breadth of coverage and appropriate wording.

3. Phase 3: testing of the provisional questionnaire for acceptability and relevance

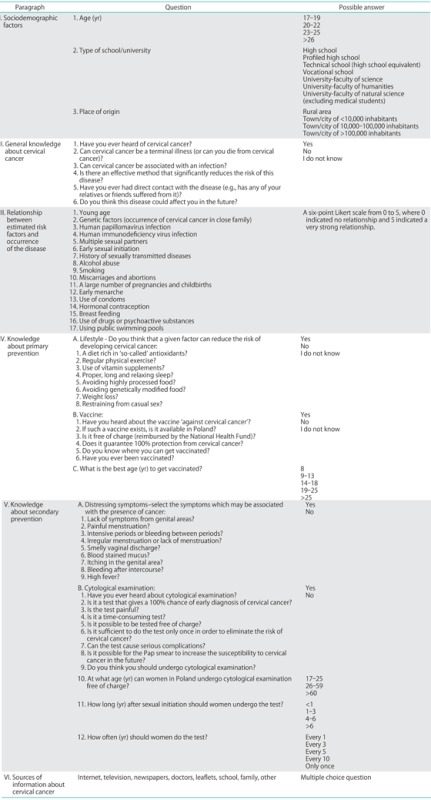

The provisional module was tested in 10 female schoolgirls (age range, 17 to 18 years) and 10 female students (age range, 20 to 23 years). In general, respondents found the questions acceptable and easy to understand. Only a few suggestions were made as to rephrasing the questions. One question from the section "general knowledge about the disease" was frequently regarded as redundant, thus it was agreed to delete it from the final version of the questionnaire. The final version of the questionnaire is presented in Appendix 1.

4. Phase 4: field-testing

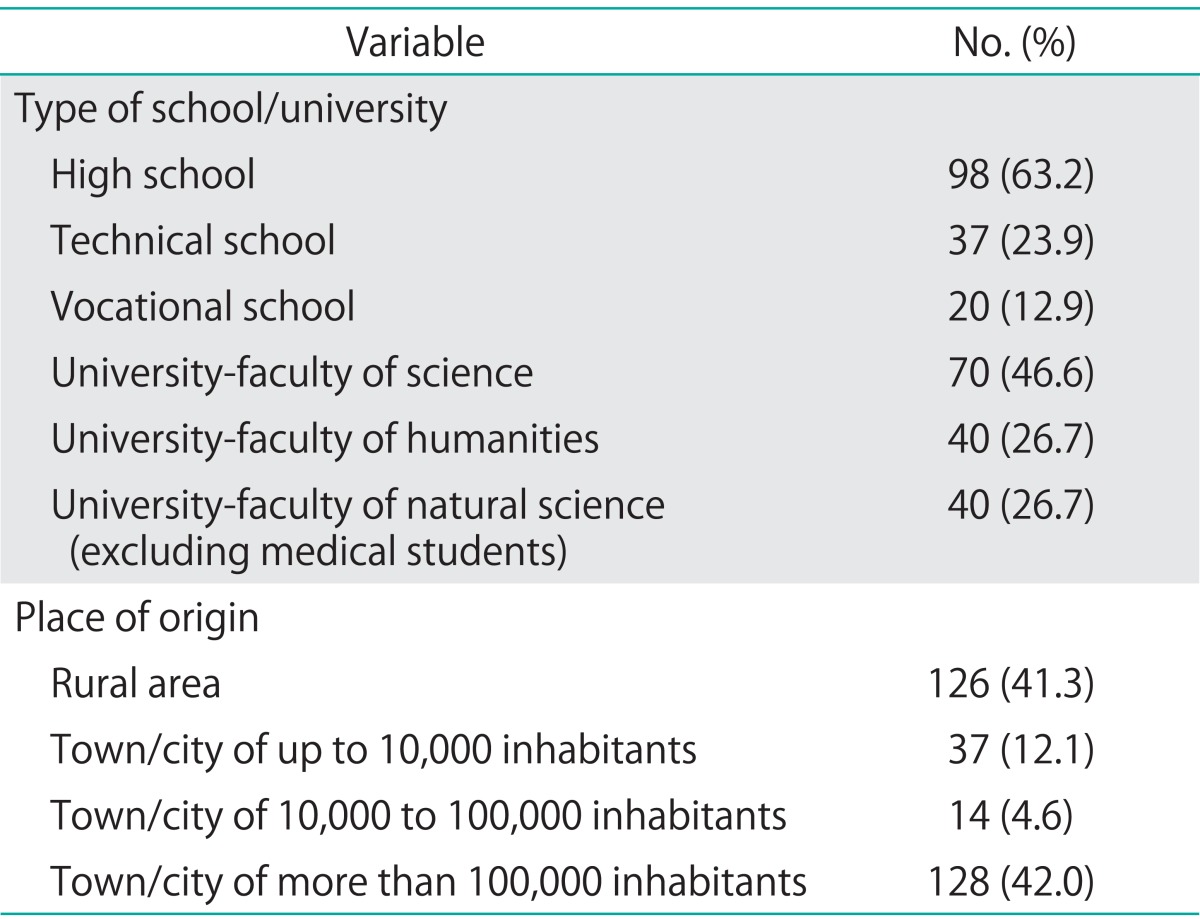

A total of 305 women were enrolled in phase 4 of the study. Of this 155 were schoolgirls (mean age±SD, 17.8±0.5) and 150 were female students (mean age±SD, 21.7±1.8). Sociodemographic data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic data of the phase 4 study group

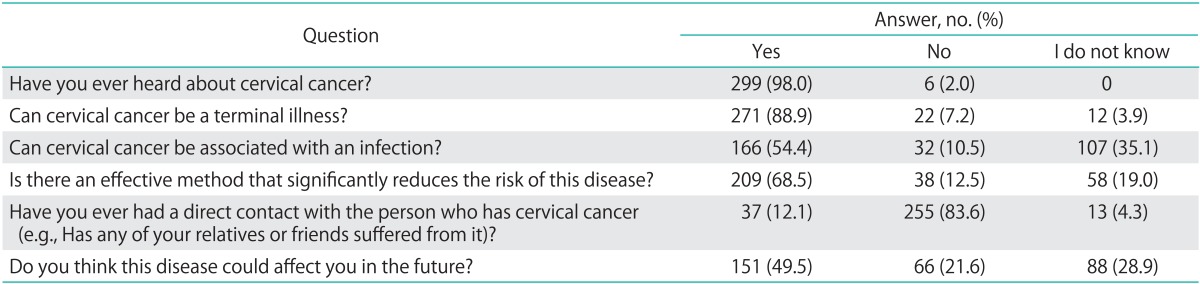

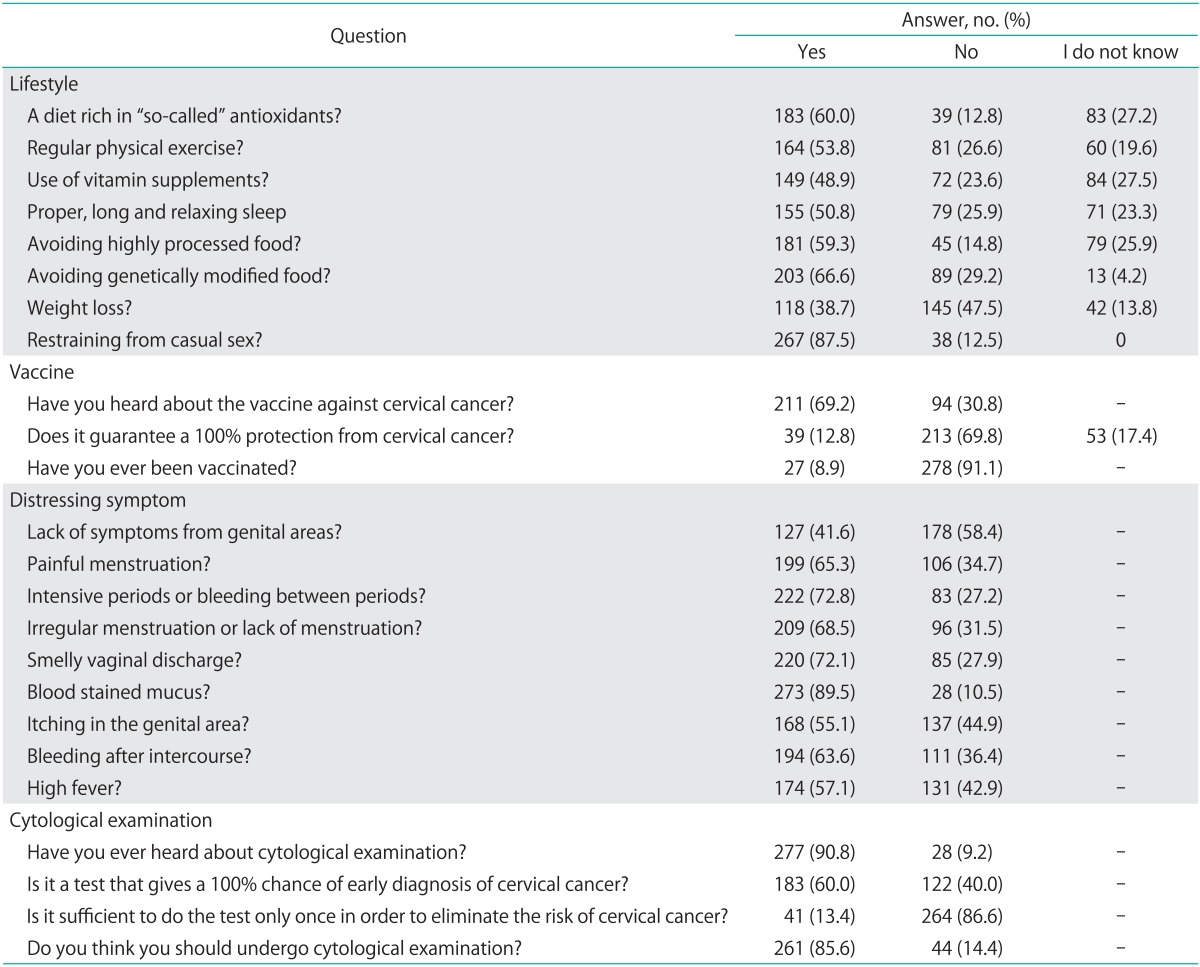

As for construct validity, Cronbach alpha coefficient for the whole questionnaire was 0.71. Cronbach alpha values for specific sections of the questionnaire were as follows: 0.06 for general knowledge about the disease; 0.81 for assessment of risk factors; 0.69 for knowledge about primary prevention; 0.70 for secondary prevention. Test-retest reliability, assessed using ICCs, ranged from 0.89 to 0.94. The statistical data regarding general knowledge, as well as knowledge on the subject of cervical cancer primary and secondary prevention are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

General knowledge about the subject of cervical cancer in the study group

Table 4.

Selected answers regarding primary and secondary cervical cancer prevention

DISCUSSION

CCKP-64 has been successfully developed to measure the level of knowledge on the subject of cervical cancer among young women. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this questionnaire is the second validated tool in this field of interest. A study describing the first such questionnaire was published this year, while our group was finishing the current study. The study by Urrutia and Hall [15] describes a questionnaire that is aimed mainly at attitudes of women towards the Pap test. In contrast, our questionnaire covers a significantly wider spectrum of problems relating to cervical cancer, as we have focused not only on the Pap test, but also on risk factors associated with the disease, as well as ways of primary prevention (HPV vaccination) and sources of information about cervical cancer. Using such an approach, a more comprehensive overview of the level of knowledge is possible to attain. This is of great importance when it comes to planning educational campaigns and looking for ways to reach potential recipients.

If the CCKP-64 is cross-culturally adapted, it would be possible to compare studies conducted in different countries. This would create an opportunity to reveal the scale of the worldwide problem, which is insufficient knowledge about cervical cancer. This might also help to strengthen international ties, and by that improve the way we fight against this terminal disease. Our field test has proven the efficacy of the questionnaire in the Polish population. The results obtained indicate that benefits from spreading CCKP-64 beyond the borders of Poland may be noticeable.

The content of the CCKP-64 questionnaire is the result of extensive literature review, interviews with healthcare providers and most importantly with schoolgirls and female students. Owing to this procedure we were able to generate a comprehensive list of issues concerning knowledge about cervical cancer and its prevention.

Interviewee feedback from the debriefing questionnaire demonstrated that the majority of respondents did not have any difficulties or confusion with the items, and did not find the questionnaire items upsetting. The majority of participants were able to complete the questionnaire within 10 to 20 minutes.

This study touched an important subject of how young Polish women talk about their sexuality. As our questionnaire was anonymous, the respondents did not reject taking part in it. However, if we were to conduct face-to-face interviews, a fairly large number of women could have rejected participating. Sexuality still seems to be tabooed among Poles, with up to 20% of students being reluctant to talk about their sexual life [20], as they are afraid this might compromise their relationship. Older Polish people, especially over 65 years of age, regard questions pertaining to sexuality as "upsetting" [21].

Construct analysis of the CCKP-64 confirmed the presence of 4 distinct sections. Two of those had "good" Cronbach alpha values, and two did not meet our >0.7 criterion for section validity. The "knowledge about primary prevention" displayed a borderline Cronbach alpha value, and as such can be left unchanged. Unfortunately, the "general knowledge about the disease" had a low Cronbach alpha value as well. However, this could have been caused by the low number of response categories in this section. In future versions we will consider to partially modify this section of the questionnaire to improve its internal consistency. Test-retest analysis of the questionnaire revealed good reliability.

It remains to be seen whether the CCKP-64 will be useful in detecting responsiveness to change over time in responders. This is soon going to be tested in our upcoming study which will assess the predicted increase in women's knowledge, following cervical cancer and HPV awareness campaigns.

Research carried out with the use of CCKP-64 among female high school and university students in Krakow Poland showed that general knowledge about cervical cancer is insufficient [14]. HPV infection is not considered to be the major etiological factor of this disease. Vaccination is uncommon, despite the high percentage of women who have heard of this method of prevention. Awareness of cytological examination as a means of secondary prevention is very high, and it is the same as in developed countries. The obtained data show that women often choose the internet and television as their primary sources of information about the disease, rather than professional medical advice. Results presented in other studies are similar and shown in Table 1. In majority, however, they lack data about sources of information that women derive their knowledge from.

It is essential that doctors fill the existing information gaps, and help their patients make an informed choice about HPV vaccination and other available methods of cervical cancer prevention. Independent evidence based patient information (e.g., leaflets) for cervical cancer and its prevention that follow criteria of high methodological quality are of utmost importance, considering the poor state of knowledge on the above mentioned subjects [22]. Doctors should provide patients with appropriately presented information [23] about ways of acquiring the vaccine, safe administration and side effects, price, number of necessary doses and duration of protection. It is worth remembering that evidence based risk information increases informed choices and improves knowledge, with little change in attitudes [24].

One must be aware that our study has certain limitations, the greatest of which was that the questionnaire was not tested in other language versions (especially English), as well as among other cultures or ethnic groups. Without cross-cultural validation, interpretation of data derived from different studies, using the CCKP-64, could lead to results being misinterpreted, and thus be inconsistent with the facts. On the other hand, some of these limitations were minimized as we based our research on results obtained from other studies directed to the same age group from different countries [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In the future we are planning to modify the survey, so that it will meet the needs of questioning women of any age.

We strongly believe that the CCKP-64 questionnaire will be an invaluable assistance and a reasonable starting point for planning social campaigns aimed at increasing awareness about primary and secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Such approach seems to be the only way with proven efficacy that could lead to reducing mortality rates. The questionnaire also gives the opportunity to verify the change in knowledge after educational campaigns. However, the use of CCKP-64 for this purpose must be further tested.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Jagiellonian University Statutory Funds.

Appendix 1

The Cervical-Cancer-Knowledge-Prevention-64 questionnaire

"I do not know" answers were not written among the questionnaire response options. During the short briefing, the students were instructed how to fill out the questionnaire and encouraged not to leave unanswered questions. They were also told that if they did not know an answer to a question, they should write "I do not know" next to it.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Arbyn M, Castellsague X, de Sanjose S, Bruni L, Saraiya M, Bray F, et al. Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2675–2686. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong EP. Prophylaxis of cervical cancer and related cervical disease: a review of the cost-effectiveness of vaccination against oncogenic HPV types. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16:217–230. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.3.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer 2013. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zatonski W. Malignant neoplasms in Poland in 2008. Warszawa: Polish National Cancer Registry; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blödt S, Holmberg C, Müller-Nordhorn J, Rieckmann N. Human papillomavirus awareness, knowledge and vaccine acceptance: a survey among 18-25 year old male and female vocational school students in Berlin, Germany. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:808–813. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rama CH, Villa LL, Pagliusi S, Andreoli MA, Costa MC, Aoki AL, et al. Awareness and knowledge of HPV, cervical cancer, and vaccines in young women after first delivery in São Paulo, Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Licht AS, Murphy JM, Hyland AJ, Fix BV, Hawk LW, Mahoney MC. Is use of the human papillomavirus vaccine among female college students related to human papillomavirus knowledge and risk perception? Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:74–78. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.037705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham CT, McPhee SJ. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of breast and cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese women. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7:305–310. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donders GG, Bellen G, Declerq A, Berger J, Van Den Bosch T, Riphagen I, et al. Change in knowledge of women about cervix cancer, human papilloma virus (HPV) and HPV vaccination due to introduction of HPV vaccines. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:93–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han YJ, Lee SR, Kang EJ, Kim MK, Kim NH, Kim HJ, et al. Knowledge regarding cervical cancer, human papillomavirus and future acceptance of vaccination among girls in their late teens in Korea. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:1090–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiro JA, Meissner HI, Kobrin S, Chollette V. What do women in the U.S know about human papillomavirus and cervical cancer? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:288–294. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutyaba T, Mmiro FA, Weiderpass E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on cervical cancer screening among the medical workers of Mulago Hospital, Uganda. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitts M, Clarke T. Human papillomavirus infections and risks of cervical cancer: what do women know? Health Educ Res. 2002;17:706–714. doi: 10.1093/her/17.6.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamzol W, Jaglarz K, Tomaszewski KA, Puskulluoglu M, Krzemieniecki K. Assessment of knowledge about cervical cancer and its prevention among female students aged 17-26 years. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;166:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urrutia MT, Hall R. Beliefs about cervical cancer and Pap test: a new Chilean questionnaire. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2013;45:126–131. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson C, Aaronson N, Blazeby JM, Bottomley A, Fayers P, Koller M, et al. EORTC quality of life group guidelines for developing questionnaire modules. 4th ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabachnik BJ, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. London: Harper & Row; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomaszewski KA, Puskulluoglu M, Biesiada K, Bochenek J, Nieckula J, Krzemieniecki K. Validation of the polish version of the eortc QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-OG25 for the assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with esophagi-gastric cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013;31:191–203. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.761323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müldner-Nieckowski Ł, Sobanski JA, Klasa K, Dembinska E, Rutkowski K. Medical students' sexuality: beliefs and attitudes. Psychiatr Pol. 2012;46:791–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paradowska D, Tomaszewski KA, Balajewicz-Nowak M, Bereza K, Tomaszewska IM, Paradowski J, et al. Validation of the Polish version of the EORTC QLQ-CX24 module for the assessment of health-related quality of life in women with cervical cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013 Aug 19; doi: 10.1111/ecc.12103. [Epub]. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gigerenzer G, Edwards A. Simple tools for understanding risks: from innumeracy to insight. BMJ. 2003;327:741–744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffrage U, Gigerenzer G. Using natural frequencies to improve diagnostic inferences. Acad Med. 1998;73:538–540. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199805000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steckelberg A, Hulfenhaus C, Haastert B, Muhlhauser I. Effect of evidence based risk information on "informed choice" in colorectal cancer screening: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d3193. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]