Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to assess whether peritoneal cytology has prognostic significance in uterine cervical cancer.

Methods

Peritoneal cytology was obtained in 228 patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] stages IB1-IIB) between October 2002 and August 2010. All patients were negative for intraperitoneal disease at the time of their radical hysterectomy. The pathological features and clinical prognosis of cases of positive peritoneal cytology were examined retrospectively.

Results

Peritoneal cytology was positive in 9 patients (3.9%). Of these patients, 3/139 (2.2%) had squamous cell carcinoma and 6/89 (6.7%) had adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma. One of the 3 patients with squamous cell carcinoma who had positive cytology had a recurrence at the vaginal stump 21 months after radical hysterectomy. All of the 6 patients with adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma had disease recurrence during the follow-up period: 3 with peritoneal dissemination and 2 with lymph node metastases. There were significant differences in recurrence-free survival and overall survival between the peritoneal cytology-negative and cytology-positive groups (log-rank p<0.001). Multivariate analysis of prognosis in cervical cancer revealed that peritoneal cytology (p=0.029) and histological type (p=0.004) were independent prognostic factors.

Conclusion

Positive peritoneal cytology may be associated with a poor prognosis in adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Therefore, the results of peritoneal cytology must be considered in postoperative treatment planning.

Keywords: Peritoneal cytology, Prognosis, Radical hysterectomy, Uterine cervical cancer

INTRODUCTION

Cytologic examination of peritoneal fluid obtained during surgery is commonly performed and a positive result is considered to be a poor prognostic factor in endometrial cancer. In cervical cancer, however, only a few reports have addressed the problem of positive peritoneal cytology. The rate of positivity has been reported to range from 0% to 15% [1,2,3,4,5]. Previous reports regarding this issue have been inconsistent; some studies reported that patients with positive peritoneal cytology have a worse prognosis than those with negative cytology [3,6,7], while other studies reported that positive peritoneal cytology was associated with poor prognosis only in the patients with adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma (ADC), but not in those with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [2]. There was also a study that failed to show any prognostic implications of positive peritoneal cytology in cervical cancer [1]. The present retrospective study was undertaken to clarify the prognostic significance of peritoneal cytology in surgically treated patients with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB-IIB cervical cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 2002 and 2010, 228 patients undergoing radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection for FIGO stage IB-IIB cervical cancer were treated at Shizuoka Cancer Center Hospital. This study included patients who met the following criteria: proven invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix, and FIGO stage IB, IIA, or IIB disease without para-aortic lymph node metastases. Para-aortic lymph nodes were evaluated by computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT. All of the patients underwent radical abdominal hysterectomy. The patients had no macroscopic extrauterine disease disseminating over the surface of the peritoneum or organs in the abdominal cavity at the time of primary surgery. Patients with microscopic peritoneal dissemination in the abdominal cavity that was proven by pathological analysis of the adnexa were excluded. Those who had other simultaneous carcinomas or other epithelial tumors, including endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, and tubal cancer, were also excluded.

Cytopathologic diagnosis was performed according to the following procedure. Cytological specimens were obtained by laparotomy immediately upon entering the peritoneal cavity. Approximately 20 mL of sterile saline was instilled into the pelvis over the uterus and then aspirated with a syringe. The samples were subjected to cytocentrifugation onto slide glasses at 1,500 rpm at room temperature for 60 seconds. After fixation with 95% ethanol, the following stains were applied: Papanicolaou, Alcian blue, Giemsa stain, and immunohistological stains for carcinoembryonic antigen and BER-EP4. Immunohistological staining was used as an ancillary diagnostic tool when the diagnosis was not clear with Papanicolaou, Alcian blue, and Giemsa stains. Two cytologists independently examined all slides.

Our standard surgical procedure for FIGO stage IB-IIB cervical cancer patients is abdominal radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Para-aortic lymph node biopsy was not performed. With respect to adjuvant therapy, patients with pelvic lymph node metastases or parametrial invasion received concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT). Patients with 2 or more of 3 risk factors (lymphovascular space invasion, deep stromal invasion, and bulky tumor) received radiotherapy [8]. Patients with positive peritoneal cytology were treated under the same protocol as those with negative peritoneal cytology.

The associations of positive peritoneal cytology with pathological features were evaluated by Fisher exact test. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the survival curves were compared by the log-rank test. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Factors that were independently associated with survival in cervical cancer were identified by multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model.

RESULTS

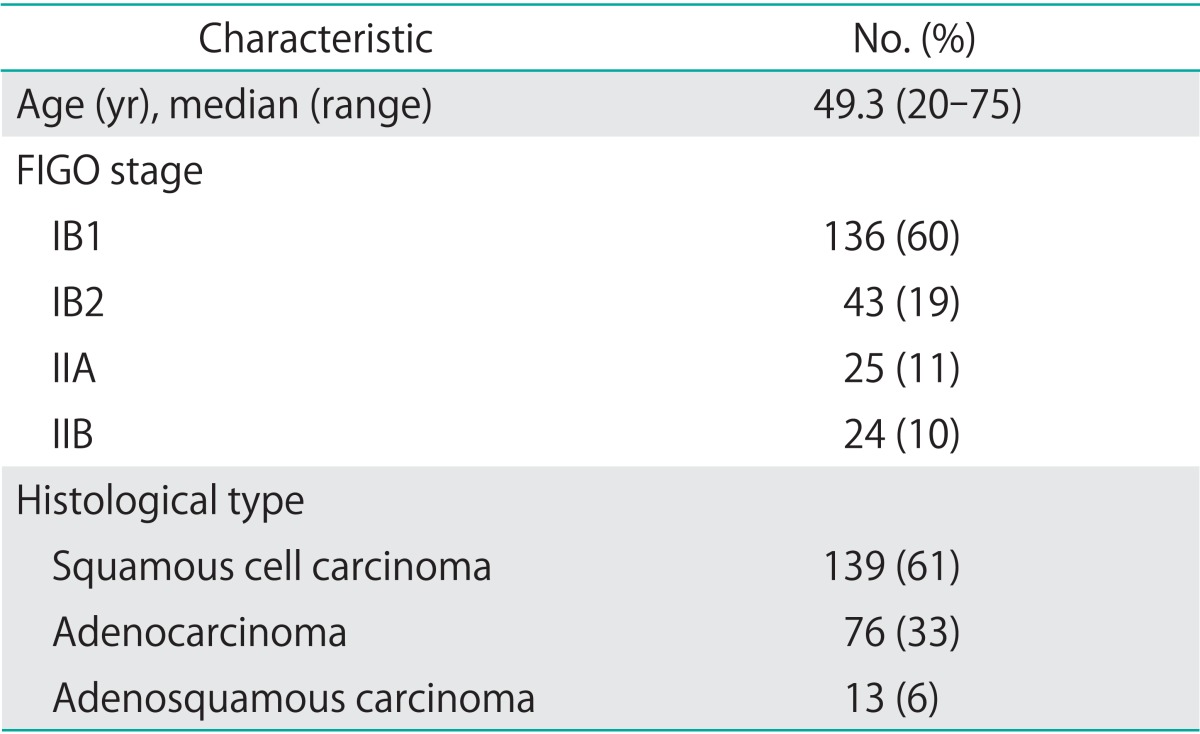

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 228 patients in this study. Of these, 139 had SCC and 89 had ADC. The median follow-up period was 51 months (range, 4 to 115 months). Twenty-eight (23 SCC and 5 ADC) patients received platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. No patients received radiotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy. Peritoneal cytology was positive in 9/228 (3.9%) patients: 3/139 (2.2%) of SCC and 6/89 (6.7%) of ADC cases. Of the patients with positive peritoneal cytology, one received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Among the cases with negative cytology, 27 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Of the ADC cases, one patient was lost to follow-up after 4 months.

Table 1.

The characteristic of 228 patients

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

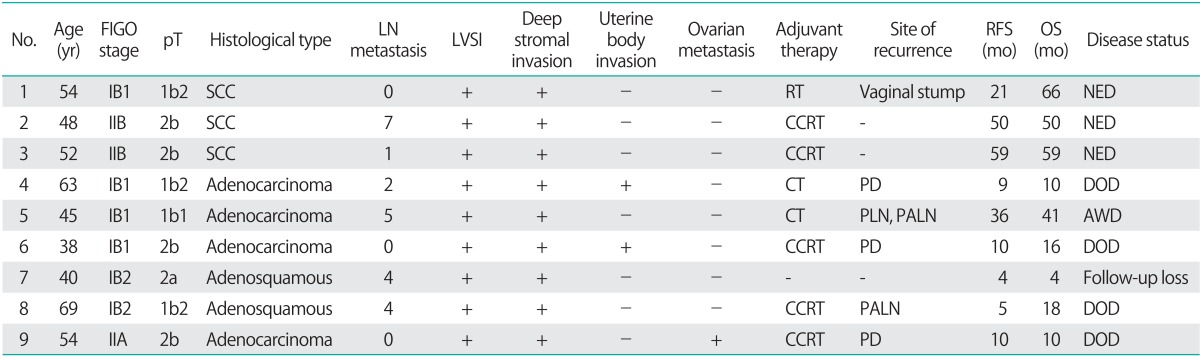

Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients with positive cytology. Of the 3 patients with SCC, 1 had FIGO stage IB1, and 2 had stage IIB cancer. Of the 6 patients with ADC, 3, 2, and 1 had stage IB1, IB2, and IIA cancer, respectively. With regard to histological type, 3 tumors were mucinous adenocarcinomas, 1 was a clear-cell adenocarcinoma, and 2 were adenosquamous carcinomas. After surgery, 5 patients received CCRT as adjuvant therapy: 4 patients received 4 cycles of cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil therapy, and 1 patient received 6 cycles of cisplatin with whole pelvic irradiation. Two patients received chemotherapy alone as adjuvant therapy consisting of 3 to 5 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel. One patient received radiotherapy to her whole pelvis.

Table 2.

The patients with positive cytology (n=9)

Adenosquamous, adenosquamous carcinoma; AWD, alive with disease; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; DOD, dead of disease; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; LN, lymph node; LVSI, lymphovascular space invasion; NED, no evidence of disease; OS, overall survival; PALN, paraaortic lymph node; PD, peritoneal dissemination; PLN, pelvic lymph node; pT, pathologic stage; RFS, recurrence-free survival; RT, radiotherapy; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

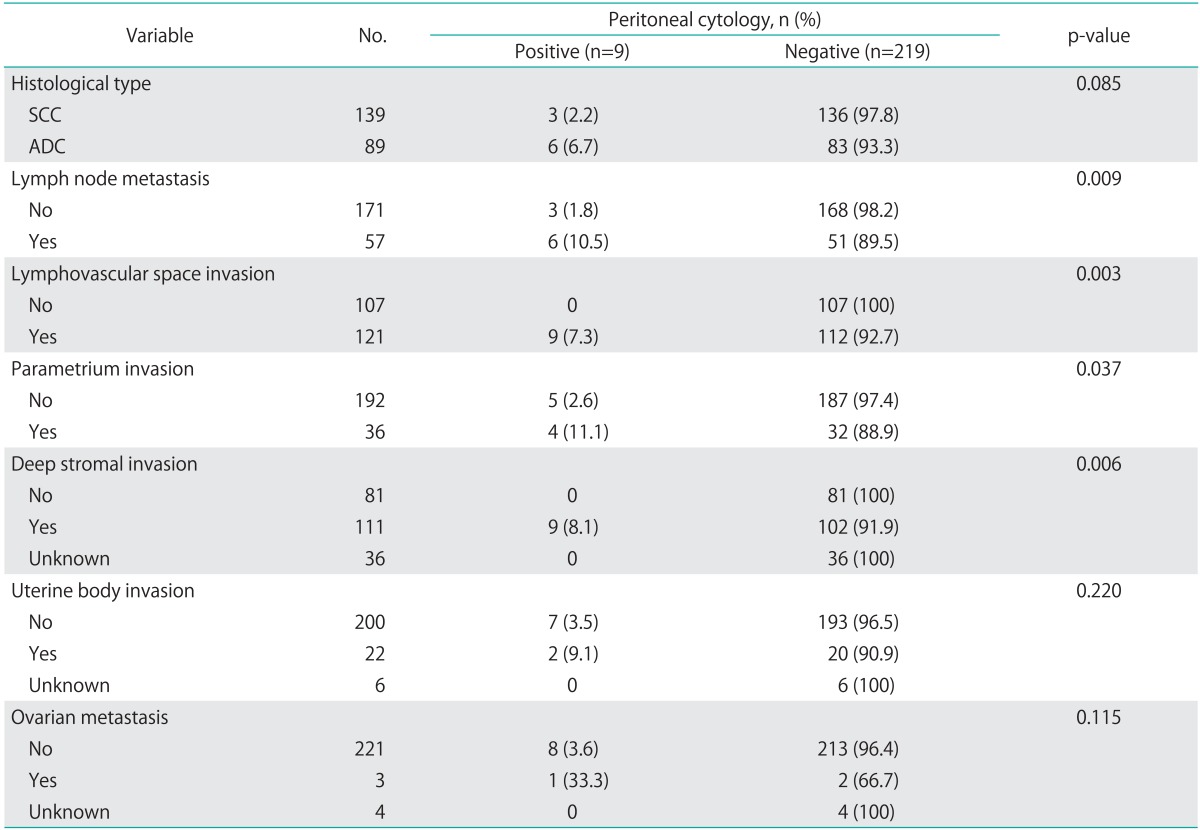

The associations between pathologic parameters and peritoneal cytology status are shown in Table 3. Positive peritoneal cytology was associated with lymph node metastases, lymphovascular space invasion, parametrial invasion, and deep stromal invasion (≥10 mm or ≥1/3).

Table 3.

Pathologic risk factors according toperitoneal cytology status

SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; ADC, adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma.

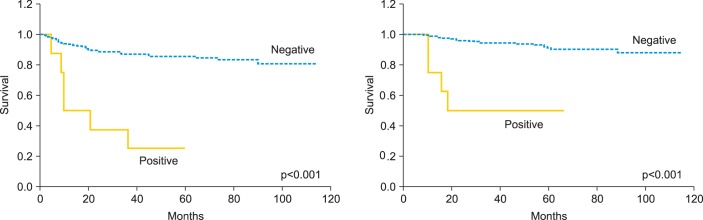

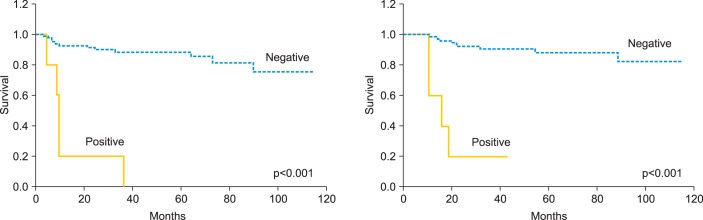

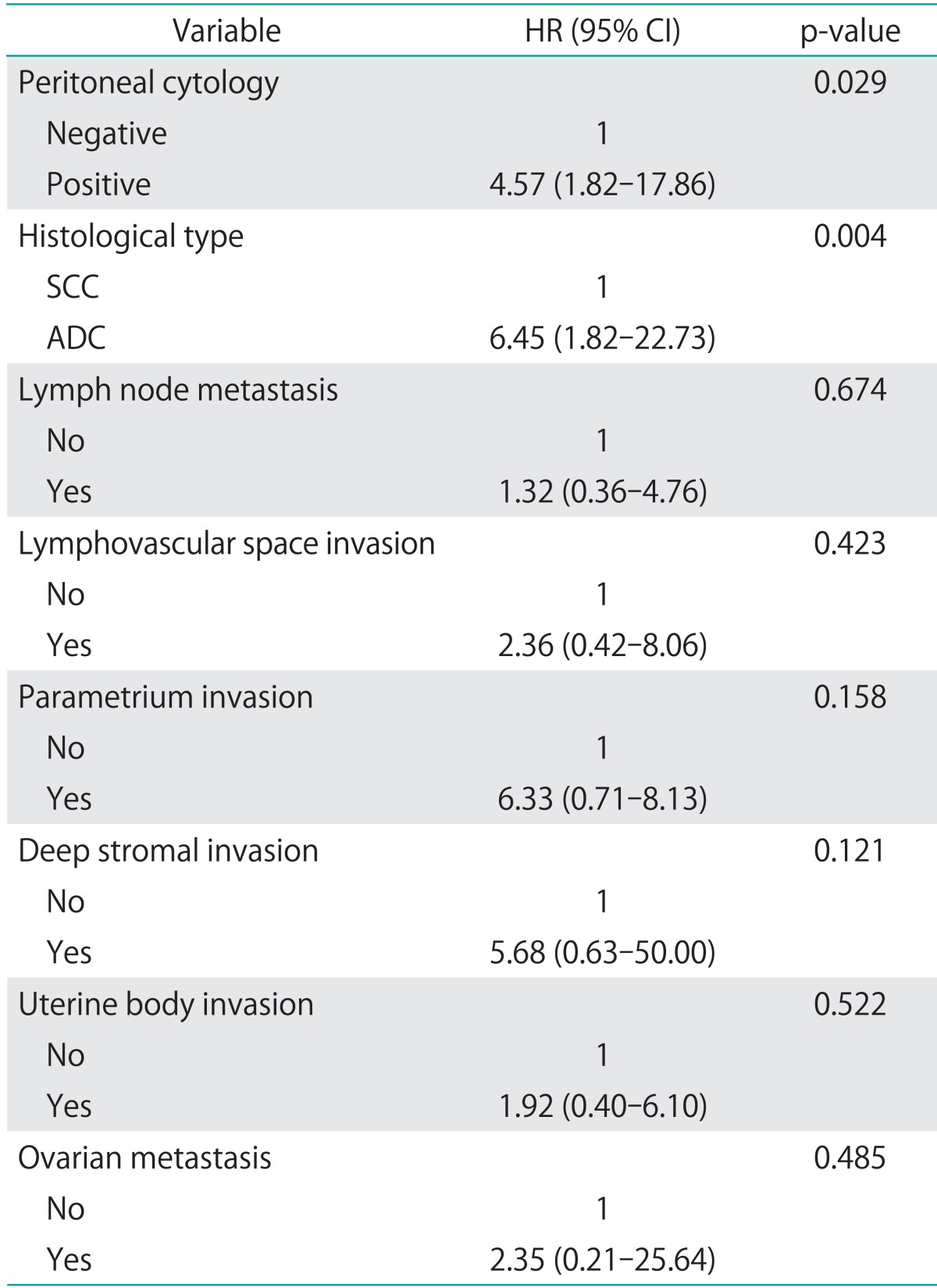

One of the 3 patients with SCC had a recurrence at the vaginal stump 21 months after radical hysterectomy and recovered completely. All 5 patients with ADC (100%) who had positive cytology had recurrence during the 10-month follow-up period: 3 (60%) with peritoneal dissemination and 2 (40%) with lymph node metastases. On the other hand, 11 (13.3%) recurred among the 83 ADC patients with negative cytology and only 1/11 (9.1%) had peritoneal dissemination. Patients with ADC with positive cytology showed a higher incidence of peritoneal dissemination (p=0.063). The 3-year RFS (cytology negative/positive) was 86.7%/37.5%, and OS was 94.4%/50.0%. When restricted to ADC cases, 3-year RFS was 88.1%/20.0%, and OS was 90.8%/20.0%. Significant differences in RFS and OS were found between the peritoneal cytology-negative and cytology-positive groups, both for total cases and when the analysis was limited to ADC cases (p<0.001 for both) (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Recurrence-free survival and overall survival in patients with stage IB to IIB cervical cancer according to the results of peritoneal cytology.

Fig. 2.

Recurrence-free survival and overall survival in patients with stage IB to IIB adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix according to the results of peritoneal cytology.

Table 4 shows the results of the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Peritoneal cytology and histological type were found to be independent prognostic factors (p=0.029 and 0.004, respectively), whereas lymph node metastases, lymphovascular space invasion, parametrial invasion, deep stromal invasion, uterine body invasion and ovarian metastases were not.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of risk factors for OS

ADC, adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

The literature contains very few reports of cases of positive peritoneal cytology in cervical cancer. The rate of positive peritoneal cytology in cervical cancer, however, differs for SCC and ADC. Compared with a rate of 0% to 1.8% for SCC [1,3,4,5,9], it is more common in ADC, with a positive rate of 11% to 15% [1,2,3]. In the present study, the rates of positive peritoneal cytology were 2.2% for SCC and 6.7% for ADC, with no significant histological differences. However, there were previous reports demonstrating that the rate of positive peritoneal cytology was significantly higher in ADC than in SCC.

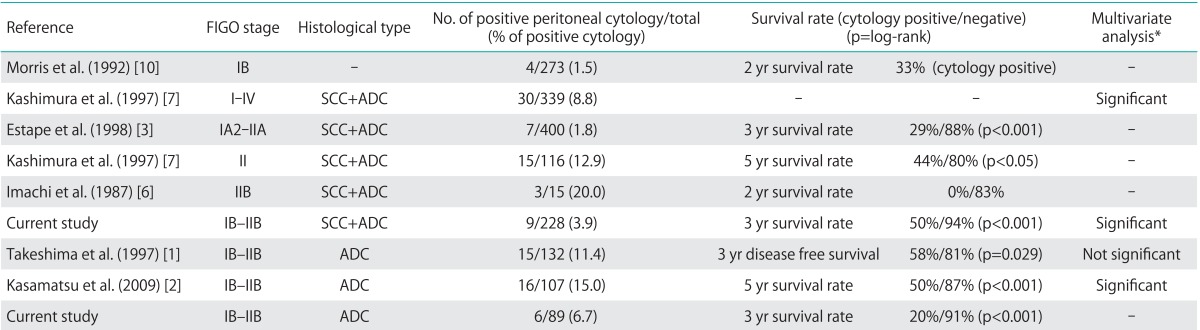

Table 5 shows previous reports of the relationship between positive peritoneal cytology and prognosis. Most previous studies reported that patients with positive cytology had clearly lower survival rates than those with negative cytology. However, positive cytology overlapped with other risk factors. No consensus was reached on whether positive cytology is an independent risk factor. Kashimura et al. [7] reported that peritoneal cytology, pelvic lymph nodes, and para-aortic lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors in stages I-IV, irrespective of the histological type. Kasamatsu et al. [2] found that peritoneal cytology, lymph node metastasis, histological grade, and ovarian metastasis were independent prognostic factors in stage I and II ADC. In the present study, peritoneal cytology and histological type were found to be independent prognostic factors.

Table 5.

Previous studies of peritoneal cytology in cervical cancer

ADC, adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

*These reports showed multivariate analyses with other risk factors in cervical cancer. Studies reporting significance showed that peritoneal cytology was an independent risk factor.

However, Takeshima et al. [1] found that, although muscle layer invasion, lymph node metastases, and cardinal ligament invasion were prognostic factors for stages I and II ADC, peritoneal cytology was not. Morris et al. [10] evaluated stage IB disease and concluded that the prognostic significance of peritoneal cytology was overshadowed by other risk factors.

A power analysis of the prognostic value of peritoneal cytology was performed in the present study, and the power was low. This is due to the small sample size, which was a limitation of this study. Similarly, the log-rank test also revealed low confidence. In other previous reports, a similarly small sample size was used, and different results were obtained.

The site of recurrence in patients with positive peritoneal cytology was inconsistent for the SCC cases in this study, which it is difficult to confirm owing to the small number of cases. Kasamatsu et al. [2] reported that in cases of ADC, 62.5% of recurrences involved peritoneal dissemination, which is significantly higher than that observed in patients with negative peritoneal cytology. In the present study, peritoneal recurrence of ADC among patients with positive peritoneal cytology occurred in 60% of cases; this percentage tended to be higher than that of patients with negative cytology. Takeshima et al. [1] found that peritoneal recurrence occurred in only 28.6% of patients, even for ADC, with no significant difference compared to patients with negative peritoneal cytology.

Although there are 2 conceivable pathways for the migration of cancer cells to the abdominal cavity, either via the fallopian tubes or by hematogenous or lymphatic spread, the detailed mechanism for this migration remains unclear. All patients with positive peritoneal cytology in the present study also had vascular invasion and deep interstitial infiltration. The frequency of lymph node metastases and parametrial invasion was also higher among patients with positive peritoneal cytology. Cervical cancer may therefore possess higher metastatic and invasive potential in patients with positive peritoneal cytology.

We do not currently take peritoneal cytology into account when deciding postoperative adjuvant treatment policies. We perform postoperative CCRT or radiotherapy according to the risk factors. However, all 5 patients with ADC developed recurrence from peritoneal dissemination or para-aortic lymph node metastasis, and they died thereafter. These recurrent sites are not "local." If we conclude that cancer cells appear in the abdominal cavity by hematogenous or lymphatic spread, then positive cytology would indicate systemic disease. Rather than administering adjuvant therapy with the aim of local control, systemic chemotherapy should be the treatment of choice for patients with positive peritoneal cytology, particularly for those with ADC.

In present study, it should be noted that peritoneal cytology in cervical cancer is of value with respect to the prognosis of uterine cervical cancer. This study did not clearly show the significance of peritoneal cytology in cases of SCC. However, patients with ADC frequently have positive peritoneal cytology, and because a positive result indicates a high recurrence rate, it may constitute an important risk factor. Therefore, we suggest that positive peritoneal cytology is also a factor that should be taken into account when making decisions concerning postoperative adjuvant therapy.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Takeshima N, Katase K, Hirai Y, Yamawaki T, Yamauchi K, Hasumi K. Prognostic value of peritoneal cytology in patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;64:136–140. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasamatsu T, Onda T, Sasajima Y, Kato T, Ikeda S, Ishikawa M, et al. Prognostic significance of positive peritoneal cytology in adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estape R, Angioli R, Wagman F, Madrigal M, Janicek M, Ganjei-Azar P, et al. Significance of intraperitoneal cytology in patients undergoing radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;68:169–171. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado G, Bundy BN, Fowler WC, Jr, Stehman FB, Sevin B, Creasman WT, et al. A prospective surgical pathological study of stage I squamous carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:314–320. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilgore LC, Orr JW, Jr, Hatch KD, Shingleton HM, Roberson J. Peritoneal cytology in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1984;19:24–29. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(84)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imachi M, Tsukamoto N, Matsuyama T, Nakano H. Peritoneal cytology in patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1987;26:202–207. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(87)90274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashimura M, Sugihara K, Toki N, Matsuura Y, Kawagoe T, Kamura T, et al. The significance of peritoneal cytology in uterine cervix and endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;67:285–290. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, Lentz SS, Muderspach LI, Zaino RJ. A randomized trial of pelvic radiation therapy versus no further therapy in selected patients with stage IB carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:177–183. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado G, Bundy BN, Fowler WC, Jr, Stehman FB, Sevin B, Creasman WT, et al. A prospective surgical pathological study of stage I squamous carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:314–320. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris PC, Haugen J, Anderson B, Buller R. The significance of peritoneal cytology in stage IB cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:196–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]