Abstract

Obesity in the childbearing population is increasingly common. Obesity is associated with increased risk for a number of maternal and neonatal pregnancy complications. Some of these complications, such as gestational diabetes, are risk factors for long-term disease in both mother and baby. While clinical practice guidelines advocate for healthy weight prior to pregnancy, there is not a clear directive for achieving healthy weight before conception. There are known benefits to even moderate weight loss prior to pregnancy, but there are potential adverse effects of restricted nutrition during the periconceptional period. Epidemiological and animal studies point to differences in offspring conceived during a time of maternal nutritional restriction. These include changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function, body composition, glucose metabolism, and cardiovascular function. The periconceptional period is therefore believed to play an important role in programming offspring physiological function and is sensitive to nutritional insult. This review summarizes the evidence to date for offspring programming as a result of maternal periconception weight loss. Further research is needed in humans to clearly identify benefits and potential risks of losing weight in the months before conceiving. This may then inform us of clinical practice guidelines for optimal approaches to achieving a healthy weight before pregnancy.

1. Introduction

Obesity in pregnancy is increasingly common in developed nations [1–3]. This is a growing concern as maternal obesity is a risk factor for a number of adverse maternal and offspring outcomes [1, 4–12]. Current consensus guidelines advocate for healthy body mass index (BMI) prior to pregnancy [13–15], but there is no agreed-upon strategy for women to achieve healthy weight before conceiving. There is evidence for improved pregnancy outcomes following weight loss between pregnancies [7, 16, 17]. Whether negative energy balance during the periconceptional period has disadvantages must also be considered. Insults to the reproductive milieu are likely to have both immediate and long-term consequences for a developing organism.

There is well-established animal research which focuses on the topic of periconceptional undernutrition that illuminates these potential risks to offspring. Corroborating this are data from cohorts of people conceived in the Dutch Famine during World War II and in seasonal famines in The Gambia suggestive of long-term health consequences. With the exception of these epidemiological studies from the Dutch Famine, human studies examining offspring outcomes following periconceptional undernutrition are lacking. It is important to determine whether benefits of weight loss during this period are in conflict with potential risks to the long-term health of offspring. Clarifying the critical windows of early development may then lead to the development of evidence-based guidelines for safe weight management in the obese obstetric population, with long-term offspring health in mind.

2. Obesity and Pregnancy: Scope of the Problem

Overweight and obesity are increasingly common in the obstetric population, affecting up to one-third of childbearing women in developed countries [2, 3, 13]. Maternal obesity is a major independent risk factor for numerous pregnancy and neonatal complications, some of which predispose the baby to disease in adulthood. From an economic standpoint, maternal obesity is associated with longer hospital stays and therefore greater costs compared to normal weight women [18, 19]. There is therefore growing interest in the management of obesity as a means of preventing these complications through lifestyle modification in the time prior to pregnancy.

3. Obesity and Pregnancy: Adverse Outcomes Associated with Overnutrition

The consequences of obesity for reproductive health range from reduced fertility to increased incidence of gestational disease and adverse neonatal outcomes.

3.1. Maternal Complications

Obesity is associated with reduced fertility [43] and is an independent risk factor for spontaneous pregnancy termination among women using infertility treatment [4, 12]. Well-documented risks of obesity in pregnancy include gestational diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, thromboembolism, perinatal infection, and caesarean section [1, 2, 5, 44–46]. A large population-based study of interpregnancy weight change was the first to provide evidence for a causal relationship between higher BMI and adverse outcomes [11]. Relatively small increases in weight between first and second pregnancies were associated with greater complications [11].

Some pregnancy complications associated with obesity are themselves risk factors for subsequent disease in mothers. Women who have had gestational diabetes incur at least a sevenfold increased risk of type 2 diabetes [47] and preeclampsia is associated with subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease [48].

3.2. Fetal/Neonatal Complications

Neonatal morbidity associated with maternal obesity includes hypoglycemia, respiratory distress, macrosomia, birth defects, and greater rate of admission to neonatal intensive care [2, 5, 49]. Preterm birth, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality are also more frequent [1, 8, 10, 44]. Overweight and obesity are the greatest modifiable risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries [6].

Several of the complications associated with maternal obesity are not only a risk to health at the time of birth but are also risk factors for adult disease in the offspring [50]. Macrosomia and gestational diabetes are both examples of complications that are then risk factors for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus later in life [51].

Mechanisms for how obesity predisposes to adverse outcomes are not yet clearly understood. Developmental pathways likely to be involved include central mechanisms regulating appetite and peripheral mechanisms involving insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular regulation [9]. On the molecular level, oxidative stress, inflammation, and epigenetic modifications may be operating in the propagation of metabolic disease from mother to child [9]. Specifically, altered offspring hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function has been implicated in programming the metabolic syndrome in offspring [52].

4. Obesity and Pregnancy: Current Approach to Management

Given the evidence for poorer pregnancy outcomes associated with obesity, current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) guidelines advocate for a BMI within the normal range prior to falling pregnant [13–15]. The guidelines also call for health professionals to educate patients about associated harms of obesity and pregnancy and to actively counsel or implement weight loss programs using evidence based strategies before their patients conceive [13, 14]. While clinicians and patients may be aware of obesity risks in pregnancy, there is no evidence-based strategy to guide preconception weight loss or the timing of that weight loss. General recommendations include strategies of dietary modification and exercise but do not prescribe a period of intervention or rate of weight loss that is most compatible with reproductive health. As the process of follicle maturation for a given menstrual cycle begins months before ovulation, weight loss may have implications for pregnancy well in advance of conception. It is therefore necessary to determine the potential benefits and risks associated with maternal weight change during this time and the mechanisms by which these occur.

5. Preconception Weight Loss: Current Evidence in Humans

Weight loss as a means for improving health in overweight and obesity has been widely validated, but there are currently no randomized controlled trials evaluating pregnancy outcomes after weight loss prior to pregnancy. A population-based study showed that a moderate reduction (4.5 kg) in prepregnancy weight is associated with lower risk of gestational diabetes [7]. Other studies of interpregnancy weight loss demonstrate reduction in risk for gestational diabetes and preeclampsia [16, 53]. Bariatric surgery has been shown to improve pregnancy outcomes in obese women [54–56]. Weight loss surgery has also been shown to result in lower rates of obesity, greater insulin sensitivity, and an improved lipid profile among children born after weight loss surgery compared to their siblings born before [57, 58]. This improvement in cardiometabolic profile is potentially attributed to differential methylation of a subset of glucoregulatory and inflammatory pathway genes in the after-surgery offspring [59, 60].

The period of maximal weight loss following Roux-en-Y procedures is typically 12–18 months, after which weight plateaus. Retrospective studies have found no difference in rates of obstetrical complications between those who conceive during this period of weight loss and those who conceive after this period [61, 62]. Long-term followup of offspring conceived during this weight loss period is lacking; however, there is an ongoing recommendation to exercise caution if falling pregnant in the early postoperative period, however evidence from long-term follow up of offspring conceived during this weight loss period is lacking.

6. Preconception Weight Loss: Potential Disadvantages

In order to confidently advocate for weight loss prior to pregnancy, the health profession must consider the potential risks associated with this behaviour change. Up to half of pregnancies are unplanned [63] and many women are unaware that they are pregnant for the first several weeks of gestation. For this reason, studies examining nutritional influences on all stages of the periconceptional period, including early gestation, are relevant to women attempting weight loss for pregnancy.

“Periconception” refers to “developmental stages which include some or all of the following early events: oocyte maturation, follicular development, conception, and embryo/blastocyst growth up until implantation” [64]. The periconceptional period is characterised by prolific cell division but has relatively low energy demands. It is therefore important to determine the potential influence of energy restriction during this period and to further elucidate the mechanisms by which dietary restriction may impact the maternal-fetal system. The weeks following implantation, early gestation, also represent an impressionable period in development.

7. Epidemiological Data: The Dutch Famine and Seasonal Undernutrition in Gambia

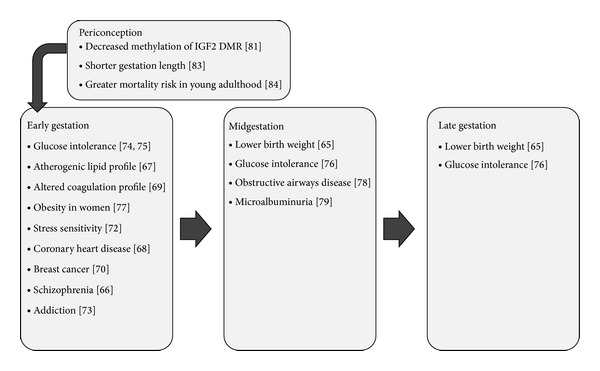

Epidemiological data from the Dutch Famine provide insight into potentially life-long consequences of undernutrition in the periconceptional and early gestational periods (Table 1). This 5-month famine during the Second World War was characterized by severely restricted food rations in The Netherlands, varying between 400 and 800 daily kilocalories at its extreme. Cohorts conceived or in utero during this famine provide evidence for differential effects of the timing of maternal undernutrition. Subjects exposed to the famine around conception or early gestation are more likely to experience a range of adult disease, largely distinct from those exposed at other points of gestation. Higher rates of glucose intolerance, atherogenic lipid profile, altered coagulation profile, obesity in women, altered stress sensitivity and response, coronary heart disease, schizophrenia, addiction, and breast cancer are observed in this cohort [65–77]. Importantly, many of these adult outcomes are independent of size at birth. The cohort exposed to famine in mid and late gestation was smaller at birth and had reduced glucose tolerance and higher rates of obstructive airways disease and microalbuminuria [65, 75, 76, 78, 79]. In addition, there may be a birth weight effect on offspring of people conceived during the Dutch Famine, lending support to epigenetic modification as a potential compensation for undernutrition [80]. Those people exposed to famine specifically during the periconception period demonstrate in adulthood persistent hypomethylation of the IGF gene compared with their unexposed siblings of the same sex [81].

Table 1.

Summary of animal study findings associated with periconception and early gestation maternal weight loss.

| HPA axis development and function | |

| (i) Altered placental 11betaHSD activity and cortisol : cortisone in fetal circulation [20, 21] | |

| (ii) Accelerated activation of fetal HPA axis in late gestation [22–25] | |

| (iii) Preterm birth [23–25] | |

| (iv) Enhanced HPA axis response to CRH stimulation at 2 months [26] | |

| (v) Blunted cortisol response to CRH and AVP stimulation in adult offspring [27] | |

| (vi) Increased adrenal gland size in males and females and greater stress response in adult female offspring accompanied by epigenetic changes to adrenal IGF2/H19 gene [28] | |

|

| |

| Growth, body composition, and energy regulating pathways | |

| (i) Altered relationships between maternal weight and fetoplacental growth in early pregnancy [29] | |

| (ii) Altered fetal growth response to late gestation stressors [30] | |

| (iii) Epigenetic changes in POMC and GR genes in fetal hypothalamus [31] | |

| (iv) Reduced fat mass in offspring of overweight ewes [32] | |

| (v) Greater percent fat mass and smaller relative heart, lungs, and adrenals in male offspring [33] | |

| (vi) Decreased voluntary physical activity in adult offspring [34] | |

|

| |

| Glucose-insulin axis | |

| (i) Impaired pregnancy insulin resistance [35] | |

| (ii) Increased fetal insulin response to glucose in late gestation [36] | |

| (iii) Altered thermogenic, insulin, and fatty acid oxidation signalling in fetal perirenal fat depot [37] | |

| (iv) Altered glucose-insulin metabolism in adult males [38] | |

| (v) Epigenetic modification of hepatic insulin-signalling molecules [39] | |

| (vi) Impaired glucose tolerance in adult offspring [40] | |

|

| |

| Cardiovascular function | |

| (i) Increased late gestation fetal blood pressure [41] | |

| (ii) Enhanced vasoconstriction in adult female coronary arteries and endothelial dysfunction in femoral resistance vessels [42] | |

Interesting patterns relating to maternal undernutrition and gestational length have also been reported from The Gambia [82, 83] (Table 1). Pregnancies conceived in the rainy “hungry” season (from September to November) where maternal weight and fat stores drop significantly are significantly shorter than those that were conceived in the dry season. Individuals born in the rainy season have an overall increased chance of death in young adulthood which may be associated with changes to the development of the immune system [84]. Individuals conceived in the rainy season had higher DNA methylation levels of metastatic epialleles, providing a mechanism through which the effects of maternal nutrition state at conception are conveyed [85]. Patterns of low birth weight, however, mirrored maternal weight, with the highest incidence in the rainy season.

8. Animal Studies

Research on animals, primarily ewes, provides support for many of the findings in epidemiological studies and highlights additional consequences of maternal undernutrition (Figure 1). Some of this research has confirmed advantages to weight loss in obese animals. Feeding obese ewes a moderately restricted diet (30% general caloric restriction), reduces female offspring fat mass typically associated with maternal obesity to control levels in a model where the embryos were transferred to nonobese ewes at six to seven days after conception [32]. There are, however, potential adverse immediate and long-term changes in offspring exposed to periconceptional undernutrition involving endocrine, developmental and cardiovascular systems.

Figure 1.

Conditions found at higher rates among cohorts exposed to maternal undernutrition during different periods of gestation (Dutch Famine and Gambian studies).

8.1. Periconceptional Undernutrition and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

Periconceptional undernutrition is associated with changes in offspring HPA axis function from early gestation to adulthood. The programming and subsequent function of the HPA axis has broad implications for health, as disturbed HPA axis function is associated with obesity and cardiovascular-related mortality [86, 87].

8.1.1. Early HPA Axis Activation and Preterm Birth

Activation of the HPA axis in sheep is essential for initiating parturition [88]. Maternal undernutrition in the periconceptional period is associated with earlier activation of the HPA axis in late gestation [22, 23]. The molecular mechanism by which this occurs is unclear, as measured mediators of steroidogenesis, MC2R and StAR mRNA, are not correlated with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in late gestation in the periconceptional undernutrition offspring [89]. Not surprisingly, periconceptional undernutrition is also associated with preterm birth [24, 25].

8.1.2. Altered Exposure to Maternal Glucocorticoids

Abnormal exposure to maternal glucocorticoids potentially explains altered fetal HPA axis function. In the same study that reported earlier activation of fetal HPA axis following periconceptional undernutrition, maternal ACTH and cortisol levels were suppressed during undernutrition and for several weeks following refeeding [23]. Placental isoforms of hydroxyl-steroid dehydrogenase (HSD) are important gatekeepers in modulating fetal exposure to maternal steroids, as they convert cortisol to cortisone. In midgestation, placental 11-beta-HSD2 isozyme activity is suppressed with an associated fetal elevation in cortisol to cortisone ratio [20]. Suppression of 11-beta-HSD2 allows greater fetal exposure to active stress hormone from maternal circulation. In late gestation, however, placental 11betaHSD activity in periconceptionally undernourished fetuses does not appear to be different from that of controls, and the cortisol : cortisone ratio is significantly lower [21]. The fetal adrenal gland is relatively inactive during midgestation; thus the placenta is likely to be the main mediator of fetal HPA axis activation via controlled exposure to active maternal cortisol [90]. Altered maternal HPA axis function as well as dysfunctional placental modulation may therefore contribute to or work in series with other mechanisms to stimulate the earlier activation of the HPA axis in periconceptionally restricted offspring.

8.1.3. Altered Postnatal HPA Axis Function and the Role of Epigenetics

Functional differences in the HPA axis persist postnatally following exposure to undernutrition around conception and early gestation, despite adequate nutrition throughout the remainder of gestation. There are variable findings reflecting different methods of undernutrition, although there consistently appears to be a difference in HPA axis function from controls. In offspring undernourished from preconception into the first 30 days of gestation, cortisol response is suppressed following arginine vasopressin (AVP) and corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation [27]. Conversely, female offspring restricted from preconception only until the first 7 days of gestation has a greater cortisol response to stress [28]. Elevated basal cortisol and greater cortisol response to stress have been found in offspring following undernutrition strictly in the first 30 days of gestation [26, 91].

Alterations to the growth and function of the HPA axis that persist postnatally following periconceptional undernutrition are potentially mediated by epigenetic modifications to molecules implicated in adrenal growth and steroidogenesis. Specifically, insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2) and its receptor IGF-2R are parentally imprinted genes involved in these processes [92]. Zhang et al. [28] nutritionally restricted normal and overnourished ewes from one month prior to conception until one-week gestation. At this point, embryos were transferred to normal weight “host” ewes that were maintained on a regular diet. Offspring exposed to undernutrition had significantly larger adrenal glands and a greater cortisol response to stress at 4 months of age. These changes were associated with reduced adrenal expression of IGF-2 mRNA, mediated by loss of methylation in the IGF2/H19 differentially methylated region (DMR) [28]. Interestingly, the cohorts exposed to the Dutch Famine during the periconceptional period also exhibit less DNA methylation of IGF2 as adults compared to their unexposed sex-matched siblings [81].

Thus, the periconceptional period is an important stage in which nutrition status may influence programming of the HPA axis.

8.2. Periconceptional Undernutrition and Offspring Growth, Body Composition, and Energy Regulating Pathways

Regulation of fetal growth and postnatal body composition appear to be at least partially programmed by the maternal reproductive environment in very early development.

8.2.1. Disrupted Gestational Growth Patterns

Periconceptional undernutrition alters the normal relationships of early gestational weight gain with placental and fetal growth [29]. Following periconceptional restriction, the growth of the fetoplacental unit is uncoupled from maternal weight gain. Additionally, there is a significant retardation of growth in response to an applied stress in late gestation, with the most pronounced effects in fetuses exposed to undernutrition strictly before conception [30]. Following undernutrition strictly before conception, offspring gain more weight in the first 12 weeks of life than periconceptionally restricted and control offspring [42]. A similar pattern of accelerated postnatal growth compared to controls was found in rat offspring exposed to undernutrition in the preimplantation period only [93]. This is associated with significant changes to blastocyst development during this time. This period is therefore likely to play an important role in determining fetal growth trajectory and the stimuli that alter its course.

8.2.2. Increased Adult Adiposity

In male offspring only, periconceptional undernutrition increases percent fat mass, restricts linear growth, and leads to smaller relative organ weights in adult sheep [33]. This is despite similar birth weight, postnatal growth trajectory, and adult total mass to controls. Corroborating this is a study that found greater proportional fat mass in sheep conceived as twins, but with one terminated early in gestation [94]. It therefore appears that relative adiposity is determined very early in development. This proportional increase in fat has important consequences for adult health. Greater percent fat mass in the context of normal total mass is termed normal weight obesity. In humans, there is a linear relationship between body fat and metabolic syndrome in individuals with normal BMI, and body fat is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular mortality in women [95].

8.2.3. Altered Regulation of Energy Intake and Expenditure

Alterations to the HPA axis following periconceptional undernutrition are not limited to adrenal gland structure and function. The hypothalamus is an important locus of control in energy homeostasis, particularly via feeding and activity drives. Persistent epigenetic modification of the hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) genes in late gestation offspring exposed to periconceptional undernutrition is likely to cause abnormal feeding regulation, as well as energy metabolism and expenditure in later life [31, 96]. Offspring exposed to periconceptional undernutrition has significantly lower voluntary activity levels as adults, with males demonstrating the lowest activity [34]. Thus, the periconceptional programming of adult disease may be mediated by inherent reductions in energy expenditure drives in addition to dysfunctional energy metabolism and storage.

8.3. Periconceptional Undernutrition and the Glucose-Insulin Axis

A potential pathway of altered fetal growth following periconceptional undernutrition is glucose metabolism. While there is evidence for the influence of late gestational nutritional status on later-life glucose metabolism [97], the periconception period also appears to be of importance.

8.3.1. Altered Gestational Glucose Exposure and Metabolism

Insulin resistance is a normal adaptation to pregnancy, allowing for greater availability of glucose to the fetus [98]. Preconception and periconception undernutrition abolish maternal insulin resistance adaptations seen in control pregnancies in ewes [35]. Fetal growth is therefore dictated by an inverse relationship with maternal insulin sensitivity, and this is most pronounced when undernutrition was limited to preconception only [35].

Altered insulin response to glucose is evident in late gestation [36], and at 10 weeks postnatally [38], with greater insulin response following glucose challenge compared to controls [36]. Preimplantation, but not periconceptional undernutrition, results in higher circulating insulin in the late gestation fetus, marking the first few days of gestation as critical in this system [37]. Exaggerated insulin response in early life is believed to be suggestive of early pancreatic maturation or altered pancreatic beta cell function [36, 38].

8.3.2. Impaired Adult Glucose Tolerance

In adult offspring, periconceptional undernutrition in normal weight ewes results in impaired glucose tolerance [40]. This is demonstrated by increased plasma glucose and a blunted insulin response to a glucose tolerance test at 10 months of age. These parameters indicate that reduced glucose clearance as a result of dysfunctional insulin secretion is the underlying mechanism modified by undernutrition. A rat model using isocaloric protein restriction in the periconception period also resulted in higher blood glucose and cholesterol in adult offspring [99].

8.3.3. Epigenetic Modification of Insulin-Signalling Molecules

Epigenetic modification of hepatic insulin-signalling molecules may explain these fetal and postnatal differences in glucose metabolism following periconceptional undernutrition. Nicholas et al. [39] found a reduced subset of these molecules (IRS1, PDK1, and aPKC) in 4-month-old lambs. Low levels of these molecules are likely to result in an impaired hepatic response to insulin in the context of nutrient abundance. Predisposition for later-life insulin resistance is therefore more likely in animals with these changes [39]. There are also epigenetic modifications to visceral fat depots likely to impair thermogenic capacity and insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue in postnatal life [37]. Thus, altered energy metabolism that may be protective in a nutritionally restricted fetal environment predisposes the postnatal offspring to metabolic disease when faced with an energy-abundant environment.

8.4. Cardiovascular Adaptation to Periconceptional Undernutrition

In addition to maladaptive metabolism, adult disease is largely influenced by impaired cardiovascular function. Hypertension is an important component of the metabolic syndrome and is strongly related to cardiovascular disease [100].

Cardiovascular adaptations to periconceptional undernutrition are apparent in late gestation, demonstrated by increased fetal blood pressure [41]. In twins, rate-pressure product is also higher than controls, and blood pressure is positively correlated with ACTH levels [41]. This is an early indication that HPA axis changes may extend to vascular regulation following periconceptional restriction.

Torrens and colleagues [42] found that pre- and periconceptional undernutrition result in vascular reactivity changes in adult offspring that are vascular bed dependent. Both pre- and periconceptional undernutrition are associated with enhanced vasoconstriction of the coronary arteries and endothelial dysfunction in femoral resistance arteries. This is relevant to the Dutch Famine data finding higher rates of coronary artery disease among people exposed to famine in early gestation [68]. Interestingly, vasoconstriction responses are greater in multiple vascular beds in periconception versus preconception undernutrition, identifying the preimplantation period as potentially more important in the programming of vasoconstriction response [42].

While there are well-established links between overtly elevated basal cortisol and hypertension [101], there is also evidence that hypertension can be associated with HPA axis dysfunction in the absence of deranged basal cortisol levels [102]. Human subjects with hypertension have a greater cortisol response to CRH challenge, despite having similar baseline cortisol to controls [103]. It is therefore conceivable that altered HPA axis findings in periconceptionally restricted offspring may help to explain cardiovascular dysfunction.

9. Conclusions, Implications, and Recommendations

Periconceptional undernutrition is associated with a number of differences in fetal and postnatal measures, many of which appear to be related to the HPA axis. Some of these modifications may act as compensation in the immediate period to protect and prepare the offspring for an adverse environment. Further development in an environment with abundant energy availability may then predispose the offspring to metabolic and cardiovascular disease.

Further clarification is required as to which periods of development are most important and therefore most sensitive to undernutrition. With respect to human pregnancy, which is rarely diagnosed until several weeks gestation, it is likely that undernutrition at any point in periconception will have consequences.

The mechanisms by which the nutrition insult results in long-term changes in the offspring are still unclear. Ongoing research into the role of epigenetics will probably contribute to further understanding of programming response to adversity.

Finally, human studies are lacking in the field of weight loss prior to pregnancy. Given the animal data, both the benefits and risks of losing weight prior to conception need to be identified in clinical populations. This is necessary to design evidence-based practice guidelines for managing obesity in the obstetric population.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.David McIntyre H, Gibbons KS, Flenady VJ, Callaway LK. Overweight and obesity in Australian mothers: epidemic or endemic? Medical Journal of Australia. 2012;196(3):184–188. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaway LK, Prins JB, Chang AM, McIntyre HD. The prevalence and impact of overweight and obesity in an Australian obstetrics population. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184(2):56–59. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu SY, Kim SY, Bish CL. Prepregnancy obesity prevalence in the United States, 2004-2005. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13(5):614–620. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellver J, Rossal LP, Bosch E, et al. Obesity and the risk of spontaneous abortion after oocyte donation. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;79(5):1136–1140. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodd JM, Grivell RM, Nguyen A-M, Chan A, Robinson JS. Maternal and perinatal health outcomes by body mass index category. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011;51(2):136–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glazer NL, Hendrickson AF, Schellenbaum GD, Mueller BA. Weight change and the risk of gestational diabetes in obese women. Epidemiology. 2004;15(6):733–737. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000142151.16880.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald SD, Han Z, Mulla S, Beyene J. Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: systematic review and meta-analyses. British Medical Journal. 2010;341:p. c3428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rkhzay-Jaf J, O'Dowd JF, Stocker CJ. Maternal obesity and the fetal origins of the metabolic syndrome. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports. 2012;6(5):487–495. doi: 10.1007/s12170-012-0257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torloni MR, Betrán AP, Daher S, et al. Maternal BMI and preterm birth: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2009;22(11):957–970. doi: 10.3109/14767050903042561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Interpregnancy weight change and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. The Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JX, Davies MJ, Norman RJ. Obesity increases the risk of spontaneous abortion during infertility treatment. Obesity Research. 2002;10(6):551–554. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee opinion no. 549: obesity in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;121(1):213–217. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000425667.10377.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Weight Management Before, During and after Pregnancy (PH27) London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Obesity in Pregnancy (C-Obs 49) 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehrlich SF, Hedderson MM, Feng J, Davenport ER, Gunderson EP, Ferrara A. Change in body mass index between pregnancies and the risk of gestational diabetes in a second pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;117(6):1323–1330. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821aa358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Getahun D, Ananth CV, Oyelese Y, Chavez MR, Kirby RS, Smulian JC. Primary preeclampsia in the second pregnancy: effects of changes in prepregnancy body mass index between pregnancies. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110(6):1319–1325. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000292090.40351.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson M, Howell S, Johnston T, Callaway L, Khor SL, Cornes S. Pre-pregnancy BMI: costs associated with maternal underweight and obesity in Queensland. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2013;53(3):243–249. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu SY, Bachman DJ, Callaghan WM, et al. Association between obesity during pregnancy and increased use of health care. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(14):1444–1453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor KL, Challis JRG, van Zijl P, et al. Do Alterations in placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11βHSD) activities explain differences in fetal hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal (HPA) function following periconceptional undernutrition or twinning in sheep? Reproductive Sciences. 2009;16(12):1201–1212. doi: 10.1177/1933719109345162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMullen S, Osgerby JC, Thurston LM, et al. Alterations in placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β HSD) activities and fetal cortisol:cortisone ratios induced by nutritional restriction prior to conception and at defined stages of gestation in ewes. Reproduction. 2004;127(6):717–725. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards LJ, McMillen IC. Impact of maternal undernutrition during the periconceptional period, fetal number, and fetal sex on the development of the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis in sheep during late gestation. Biology of Reproduction. 2002;66(5):1562–1569. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.5.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Hawkins P, et al. Periconceptional undernutrition in sheep accelerates maturation of the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in late gestation. Endocrinology. 2004;145(9):4278–4285. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumarasamy V, Mitchell MD, Bloomfield FH, et al. Effects of periconceptional undernutrition on the initiation of parturition in sheep. The American Journal of Physiology—Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2005;288(1):R67–R72. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00357.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Hawkins P, et al. A periconceptional nutritional origin for noninfectious preterm birth. Science. 2003;300(5619):p. 606. doi: 10.1126/science.1080803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chadio SE, Kotsampasi B, Papadomichelakis G, et al. Impact of maternal undernutrition in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responsiveness in sheep at different ages postnatal. Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;192(3):495–503. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliver MH, Bloomfield FH, Jaquiery AL, Todd SE, Thorstensen EB, Harding JE. Periconceptional undernutrition suppresses cortisol response to arginine vasopressin and corticotropin-releasing hormone challenge in adult sheep offspring. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 2012;3(1):52–58. doi: 10.1017/S2040174411000626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Rattanatray L, MacLaughlin SM, et al. Periconceptional undernutrition in normal and overweight ewes leads to increased adrenal growth and epigenetic changes in adrenal IGF2/H19 gene in offspring. The FASEB Journal. 2010;24(8):2772–2782. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-154294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLaughlin SM, Walker SK, Roberts CT, Kleemann DO, McMillen IC. Periconceptional nutrition and the relationship between maternal body weight changes in the periconceptional period and feto-placental growth in the sheep. Journal of Physiology. 2005;565(part 1):111–124. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rumball CWH, Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Harding JE. Different periods of periconceptional undernutrition have different effects on growth, metabolic and endocrine status in fetal sheep. Pediatric Research. 2009;66(6):605–613. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181bbde72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens A, Begum G, Cook A, et al. Epigenetic changes in the hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin and glucocorticoid receptor genes in the ovine fetus after periconceptional undernutrition. Endocrinology. 2010;151(8):3652–3664. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rattanatray L, MacLaughlin SM, Kleemann DO, Walker SK, Muhlhausler BS, McMillen IC. Impact of maternal periconceptional overnutrition on fat mass and expression of adipogenic and lipogenic genes in visceral and subcutaneous fat depots in the postnatal lamb. Endocrinology. 2010;151(11):5195–5205. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaquiery AL, Oliver MH, Honeyfield-Ross M, Harding JE, Bloomfield FH. Periconceptional undernutrition in sheep affects adult phenotype only in males. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/123610.123610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donovan EL, Hernandez CE, Matthews LR, Oliver MH, Jaquiery AL, Bloomfield FH, et al. Periconceptional undernutrition in sheep leads to decreased locomotor activity in a natural environment. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 2013;4(4):296–299. doi: 10.1017/S2040174413000214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaquiery AL, Oliver MH, Rumball CWH, Bloomfield FH, Harding JE. Undernutrition before mating in ewes impairs the development of insulin resistance during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;114(4):869–876. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8fb86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliver MH, Hawkins P, Breier BH, van Zijl PL, Sargison SA, Harding JE. Maternal undernutrition during the periconceptual period increases plasma taurine levels and insulin response to glucose but not arginine in the late gestation fetal sheep. Endocrinology. 2001;142(10):4576–4579. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lie S, Morrison JL, Williams-Wyss O, et al. Impact of embryo number and periconceptional undernutrition on factors regulating adipogenesis, lipogenesis and metabolism in adipose tissue in the sheep fetus. The American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;305(8):E931–E941. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00180.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith NA, McAuliffe FM, Quinn K, Lonergan P, Evans ACO. The negative effects of a short period of maternal undernutrition at conception on the glucose-insulin system of offspring in sheep. Animal Reproduction Science. 2010;121(1-2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholas LM, Rattanatray L, MacLaughlin SM, et al. Differential effects of maternal obesity and weight loss in the periconceptional period on the epigenetic regulation of hepatic insulin-signaling pathways in the offspring. The FASEB Journal. 2013;27(9):3786–3796. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-227918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Todd SE, Oliver MH, Jaquiery AL, Bloomfield FH, Harding JE. Periconceptional undernutrition of ewes impairs glucose tolerance in their adult offspring. Pediatric Research. 2009;65(4):409–413. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181975efa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards LJ, McMillen IC. Periconceptional nutrition programs development of the cardiovascular system in the fetal sheep. The American Journal of Physiology—Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2002;283(3):R669–R679. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00736.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torrens C, Snelling TH, Chau R, et al. Effects of pre- and periconceptional undernutrition on arterial function in adult female sheep are vascular bed dependent. Experimental Physiology. 2009;94(9):1024–1033. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallaher BW, Breier BH, Keven CL, Harding JE, Gluckman PD. Fetal programming of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein-3: evidence for an altered response to undernutrition in late gestation following exposure to periconceptual undernutrition in the sheep. Journal of Endocrinology. 1998;159(3):501–508. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1590501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D, et al. Obesity, obstetric complications and cesarean delivery rate—a population-based screening study. The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(4):1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan ES, Wilson E, Watkins T, Gao F, Hunt BJ. Maternal obesity and venous thromboembolism. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2012;21(3):253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson HE, O’Connell CM, Joseph KS, McLeod NL. Maternal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(6):1357–1364. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000188387.88032.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2007;335(7627):974–977. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg TJ, Garbers S, Chavkin W, Chiasson MA. Prepregnancy weight and adverse perinatal outcomes in an ethnically diverse population. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;102(5, part 1):1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McMillen IC, MacLaughlin SM, Muhlhausler BS, Gentili S, Duffield JL, Morrison JL. Developmental origins of adult health and disease: the role of periconceptional and foetal nutrition. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2008;102(2):82–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Lamichhane AP, et al. Association of intrauterine exposure to maternal diabetes and obesity with type 2 diabetes in youth: the SEARCH case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1422–1426. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buckley AJ, Jaquiery AL, Harding JE. Nutritional programming of adult disease. Cell and Tissue Research. 2005;322(1):73–79. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mostello D, Jen Chang J, Allen J, Luehr L, Shyken J, Leet T. Recurrent preeclampsia: the effect of weight change between pregnancies. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116(3):667–672. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ed74ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Birth outcomes in obese women after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(5 I):965–972. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000181821.82022.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bennett WL, Gilson MM, Jamshidi R, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: retrospective analysis of insurance claims data. British Medical Journal. 2010;340(7757):p. c1662. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hezelgrave NL, Oteng-Ntim E. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery: a review. Journal of Obesity. 2011;2011:5 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/501939.501939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith J, Cianflone K, Biron S, et al. Effects of maternal surgical weight loss in mothers on intergenerational transmission of obesity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94(11):4275–4283. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kral JG, Biron S, Simard S, et al. Large maternal weight loss from obesity surgery prevents transmission of obesity to children who were followed for 2 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1644–e1649. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guenard F, Deshaies Y, Cianflone K, Kral JG, Marceau P, Vohl MC. Differential methylation in glucoregulatory genes of offspring born before vs. after maternal gastrointestinal bypass surgery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(28):11439–11444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216959110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guenard F, Tchernof A, Deshaies Y, et al. Methylation and expression of immune and inflammatory genes in the offspring of bariatric bypass surgery patients. Journal of Obesity. 2013;2013:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/492170.492170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wax JR, Cartin A, Wolff R, Lepich S, Pinette MG, Blackstone J. Pregnancy following gastric bypass for morbid obesity: effect of surgery-to-conception interval on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obesity Surgery. 2008;18(12):1517–1521. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9647-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kjaer MM, Nilas L. Timing of pregnancy after gastric bypass-a national register-based cohort study. Obesity Surgery. 2013;23(8):1281–1285. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0903-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.International MS. Real choices, women, contraception and unplanned pregnancy. Websurvery, commisioned by Marie Stopes International, 2008.

- 64.MacLaughlin SM, Mühlhäusler BS, Gentili S, McMillen IC. When in gestation do nutritional alterations exert their effects? A focus on the early origins of adult disease. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2006;13(6):516–522. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roseboom T, de Rooij S, Painter R. The Dutch famine and its long-term consequences for adult health. Early Human Development. 2006;82(8):485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoek HW, Brown AS, Susser E. The Dutch Famine and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33(8):373–379. doi: 10.1007/s001270050068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JHP, Osmond C, Barker DJP, Ravelli ACJ, Bleker OP. Plasma lipid profiles in adults after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;72(5):1101–1106. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JHP, Osmond C, et al. Coronary heart disease after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine, 1944-45. Heart. 2000;84(6):595–598. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.6.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JHP, Ravelli ACJ, Osmond C, Barker DJP, Bleker OP. Plasma fibrinogen and factor VII concentrations in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. British Journal of Haematology. 2000;111(1):112–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Painter RC, de Rooij SR, Bossuyt PMM, et al. A possible link between prenatal exposure to famine and breast cancer: a preliminary study. The American Journal of Human Biology. 2006;18(6):853–856. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Phillips DIW, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in adults who were prenatally exposed to the Dutch famine. European Journal of Endocrinology of the European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2006;155(1):153–160. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Painter RC, de Rooij SR, Bossuyt PM, et al. Blood pressure response to psychological stressors in adults after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine. Journal of Hypertension. 2006;24(9):1771–1778. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000242401.45591.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Franzek EJ, Sprangers N, Janssens ACJW, van Duijn CM, van de Wetering BJM. Prenatal exposure to the 1944-45 Dutch “hunger winter” and addiction later in life. Addiction. 2008;103(3):433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Phillips DIW, et al. Impaired insulin secretion after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1897–1901. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, et al. Glucose tolerance at age 58 and the decline of glucose tolerance in comparison with age 50 in people prenatally exposed to the Dutch famine. Diabetologia. 2006;49(4):637–643. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, Bleker OP. Prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine and disease in later life: an overview. Reproductive Toxicology. 2005;20(3):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ravelli ACJ, van der Meulen JHP, Osmond C, Barker DJP, Bleker OP. Obesity at the age of 50 y in men and women exposed to famine prenatally. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;70(5):811–816. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lopuhaä CE, Roseboom TJ, Osmond C, et al. Atopy, lung function, and obstructive airways disease after prenatal exposure to famine. Thorax. 2000;55(7):555–561. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.7.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, van Montfrans GA, et al. Microalbuminuria in adults after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2005;16(1):189–194. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lumey LH. Decreased birthweights in infants after maternal in utero exposure to the Dutch famine of 1944-1945. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 1992;6(2):240–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1992.tb00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(44):17046–17049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rayco-Solon P, Fulford AJ, Prentice AM. Differential effects of seasonality on preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction in rural Africans. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;81(1):134–139. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rayco-Solon P, Fulford AJ, Prentice AM. Maternal preconceptional weight and gestational length. The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;192(4):1133–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moore SE, Cole TJ, Poskitt EME, et al. Season of birth predicts mortality in rural Gambia. Nature. 1997;388(6641):p. 434. doi: 10.1038/41245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Waterland RA, Kellermayer R, Laritsky E, et al. Season of conception in rural gambia affects DNA methylation at putative human metastable epialleles. PLoS Genetics. 2010;6(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001252.e1001252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rutters F, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Lemmens SGT, Born JM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis functioning in relation to body fat distribution. Clinical Endocrinology. 2010;72(6):738–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kumari M, Shipley M, Stafford M, Kivimaki M. Association of diurnal patterns in salivary cortisol with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: findings from the Whitehall II study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(5):1478–1485. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Challis JRG, Bloomfield FH, Booking AD, et al. Fetal signals and parturition. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2005;31(6):492–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2005.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Edwards LJ, Bryce AE, Coulter CL, McMillen IC. Maternal undernutrition throughout pregnancy increases adrenocorticotrophin receptor and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression in the adrenal gland of twin fetal sheep during late gestation. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2002;196(1-2):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Glickman JA, Challis JRG. The changing response pattern of sheep fetal adrenal cells throughout the course of gestation. Endocrinology. 1980;106(5):1371–1376. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-5-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gardner DS, van Bon BWM, Dandrea J, et al. Effect of periconceptional undernutrition and gender on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in young adult sheep. Journal of Endocrinology. 2006;190(2):203–212. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ross JT, McMillen IC, Lok F, Thiel AG, Owens JA, Coulter CL. Intrafetal insulin-like growth factor-I infusion stimulates adrenal growth but not steroidogenesis in the sheep fetus during late gestation. Endocrinology. 2007;148(11):5424–5432. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kwong WY, Wild AE, Roberts P, Willis AC, Fleming TP. Maternal undernutrition during the preimplantation period of rat development causes blastocyst abnormalities and programming of postnatal hypertension. Development. 2000;127(19):4195–4202. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hancock SN, Oliver MH, Mclean C, Jaquiery AL, Bloomfield FH. Size at birth and adult fat mass in twin sheep are determined in early gestation. Journal of Physiology. 2012;590(part 5):1273–1285. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.220699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. Normal weight obesity: a risk factor for cardiometabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular mortality. European Heart Journal. 2010;31(6):737–746. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Begum G, Davies A, Stevens A, et al. Maternal under nutrition programs tissue-specific epigenetic changes in the glucocorticoid receptor in adult offspring. Endocrinology. 2013;154(12):4560–4569. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gardner DS, Tingey K, van Bon BWM, et al. Programming of glucose-insulin metabolism in adult sheep after maternal undernutrition. The American Journal of Physiology—Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2005;289(4):R947–R954. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00120.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Catalano PM, Tyzbir ED, Wolfe RR, et al. Carbohydrate metabolism during pregnancy in control subjects and women with gestational diabetes. The American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1993;264(1, part 1):E60–E67. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.1.E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Joshi S, Garole V, Daware M, Girigosavi S, Rao S. Maternal protein restriction before pregnancy affects vital organs of offspring in Wistar rats. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2003;52(1):13–18. doi: 10.1053/meta.2003.50010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. The Lancet. 2005;365(9468):1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Whitworth JA, Mangos GJ, Kelly JJ. Cushing, cortisol, and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2000;36(5):912–916. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reynolds RM, Walker BR, Syddall HE, et al. Altered control of cortisol secretion in adult men with low birth weight and cardiovascular risk factors. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(1):245–250. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gold SM, Dziobek I, Rogers K, Bayoumy A, McHugh PF, Convit A. Hypertension and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity affect frontal lobe integrity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90(6):3262–3267. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]