Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects nearly 25% of adults, however an objective diagnosis is rarely established. We hypothesized that patients’ symptoms and response to acid-reducing therapy are poor predictors of the outcome of 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring.

METHODS

A review of 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring studies performed at an ambulatory tertiary care center between 2004 and 2011 was performed. Demographics, type of GERD symptoms, and duration and response to acid-reducing medications prior to referral for pH monitoring were collected. DeMeester score, symptom sensitivity index (SSI), and symptom index (SI) were tabulated and compared to the patients’ symptoms and response to medical therapy.

RESULTS

One hundred patients were included. Of all reported symptoms, only heartburn was more common in patients with positive DeMeester scores, but there were no correlations between any symptoms and SSI or SI scores. Sixty-nine percent of patients with esophageal symptoms had a positive DeMeester score compared to only 29% of patients with extraesophageal symptoms (p<0.01). Esophageal symptoms and endoscopic evidence of GERD significantly increased the likelihood of having a positive DeMeester score, but they had no influence on SSI or SI scores. There was no correlation between response to acid-reducing medications and DeMeester, SSI or SI scores. A total of 536 person-years of acid-reducing medications were prescribed to the study population, of which 151 (28%) were prescribed to patients who had a negative pH study.

CONCLUSION

Extraesophageal symptoms and response to empiric trials of acid-reducing medications are poor predictors of the presence of GERD and the DeMeester score is more likely to identify GERD in patients who met other empiric diagnostic criteria than either SSI or SI. Early referral for 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring may avoid lengthy periods of unnecessary medical therapy.

Keywords: GERD, esophageal pH monitoring, reflux, proton-pump inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects over 25% of the population in the United States and an additional 35% experience occasional symptoms of reflux without being formally diagnosed with GERD [1, 2]. It places an enormous burden on our healthcare system, as GERD-related symptoms and complications prompted 5.5 million outpatient visits and 76,000 inpatient admissions in 2002 and 2005, respectively [3, 4]. In addition, over $10 billion were spent on acid-reducing medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2-receptor antagonists in 2004 – a 220% increase from five years earlier [3, 4].

Despite the frequency with which GERD is encountered in clinical practice, a standard definition and diagnostic algorithm have not been universally adopted. The Montreal consensus group defined GERD as a condition where “reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications,” [5] while the Brazilian consensus definition added a mechanistic explanation, stating that GERD is “related to the retrograde flow of gastroduodenal contents into the esophagus and/or adjacent organs, resulting in a variable spectrum of symptoms, with or without tissue damage.” [6] GERD can present with esophageal syndromes characterized by “typical” symptoms such as reflux esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett’s metaplasia, or extraesophageal syndromes characterized by “atypical” symptoms such as chronic cough, laryngitis, asthma, dental erosions, sinusitis, and pulmonary fibrosis [7–13].

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommends treating patients who present with GERD symptoms with an empiric eight-week trial of twice-daily PPIs without definitively establishing the diagnosis [14–17]. Further diagnostic evaluation with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or esophageal pH monitoring are only recommended after failure of medical therapy or in the presence of “alarm symptoms” such as dysphagia, bleeding, weight loss, epigastric mass, or anemia.

Twenty-four hour ambulatory pH monitoring directly measures the extent and frequency with which acid refluxes into the esophagus and has been shown to be the most sensitive and specific test to objectively diagnose GERD [18–23]. Multiple scoring systems have been proposed to quantify the results of pH monitoring studies; however, no single system has gained general acceptance as the “gold standard” [24]. The DeMeester score utilizes a 6-point composite scoring system which considers the percent and total amount of time the esophageal pH is less than four in the upright and supine positions, total number of reflux episodes, number of reflux episodes lasting greater than five minutes, and the duration of the longest episode [25, 26]. The symptom sensitivity index (SSI) is calculated by dividing the number of symptom-associated reflux episodes by the total number of reflux episodes × 100% [27]. The symptom index (SI) is calculated by dividing the number of reflux-related symptom episodes by the total number of symptom episodes × 100% [28]. The symptom association probability (SAP) is calculated by dividing the study period into consecutive two-minute segments and then using the Fisher’s exact test to determine the statistical association between reflux events and symptoms [29].

We hypothesized that current clinical practice guidelines often result in lengthy courses of acid-reducing medications without objective evidence of GERD, and that the response to empiric trials of medical therapy is a poor predictor of an abnormal pH monitoring study. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate the correlation between signs and symptoms that are commonly used to empirically diagnose GERD and the objective diagnosis of GERD when the DeMeester, SSI, and SI scoring systems are used.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective review was performed of patients who underwent 24-hour two-channel esophageal pH monitoring studies at a single academic institution between 2004 and 2011. Patients who previously underwent anti-reflux surgery or who had insufficient historical data in their medical records were excluded. Information was collected on patients’ age, sex, type of GERD symptoms, results of previous esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD), duration of acid-reducing medication use prior to referral for pH monitoring, and response to prior medical therapy. Esophageal symptoms were defined as regurgitation, heartburn, and dysphagia and all other symptoms were considered extraesophageal. Endoscopic evidence of GERD was defined as the presence of erosive esophagitis, gastroesophageal stricture, Barrett’s metaplasia, or direct observation of reflux of gastric contents. Response to acid-reducing medications was divided into four categories: none, complete, partial, and relapse of symptoms (symptoms recurred at any time following an initial complete response). The Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medical College approved this study.

All patients were evaluated with a Given Imaging Digitrapper® pH Z Monitoring System (Yoqneam, Israel). The probe was placed 5 cm above the proximal boarder of the lower esophageal sphincter established by esophageal manometry. Patients were instructed to eat three regular meals, maintain regular activity, and sleep supine during the study. All probes were placed in the early morning to ensure that breakfast, lunch, and dinner were captured in the study period. Patients were instructed to cease taking PPIs and H2 blockers for two weeks prior to the study and were not allowed to take any medications that alleviated their symptoms or affected esophageal motility or function (including muscle relaxants). During the monitoring period, patients pressed an event button each time they experienced symptoms and kept a diary of these symptoms, their diet, and activities. For each patient, DeMeester, SSI, and SI scores were tabulated. A DeMeester score of ≥14.7, an SSI score of ≥10%, and an SI score of ≥50% were considered positive studies. SAP was not evaluated for this study because it could not be calculated with the monitoring system that was used during the study period.

Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Patients were grouped by type of GERD symptoms (esophageal vs. extraesophageal) and then by response to acid-reducing medications (complete, none, partial and relapse) for analysis. The two primary outcomes were frequency of a positive pH monitoring study and the duration of treatment with acid-reducing therapy prior to referral for pH monitoring. Multivariate logistic regression was then used to determine the influence of esophageal GERD symptoms, endoscopic evidence of GERD, and response to empiric acid-reducing medication trials on the outcome of the pH monitoring study using three difference scoring systems to define a positive study (DeMeester, SSI, and SI scores).

P-values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test, student’s T-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, or Kruskal-Wallace test as appropriate. Variables that followed a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while those that were not normally distributed are presented as median (range). Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 12.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 160 patients were reviewed; 60 patients were excluded due to prior anti-reflux surgery or incomplete medical records, thus leaving 100 patients for analysis. SSI and SI scores could not be calculated for three patients due to incomplete symptom diaries. Patients who had a positive 24-hour pH monitoring study using all three scoring systems were well matched on age and gender to those who tested negative with the exception of SSI in which patients in the negative group were more likely to be female (75% vs. 50%, p=0.02, Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and symptoms

| DeMeester (Threshold ≥14.7) |

Symptom Sensitivity Index (SSI) (Threshold ≥10%) |

Symptom Index (SI) (Threshold ≥50%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (N=38) |

Positive (N=62) |

P-value* | Negative (N=71) |

Positive (N=26) |

P-value* | Negative (N=41) |

Positive (N=56) |

P-value* | |

| Age (mean yr ± SD) | 46.21±16.27 | 49.19±13.71 | 0.33 | 47.97±15.30 | 46.88±13.60 | 0.75 | 49.22±15.80 | 46.55±14.02 | 0.38 |

| Females | 30 (79%) | 39 (63%) | 0.09 | 53 (75%) | 13 (50%) | 0.02 | 31 (76%) | 35 (63%) | 0.17 |

| Endoscopic GERD | 3 (8%) | 22 (35%) | <0.01 | 17 (24%) | 7 (27%) | 0.79 | 7 (18%) | 17 (30%) | 0.15 |

| Symptoms | |||||||||

| Heartburn | 15 (40%) | 39 (63%) | 0.02 | 37 (52%) | 16 (62%) | 0.41 | 19 (46%) | 34 (61%) | 0.16 |

| Regurgitation | 9 (24%) | 18 (29%) | 0.56 | 18 (25%) | 7 (27%) | 0.88 | 8 (20%) | 17 (30%) | 0.23 |

| Dysphagia | 16 (42%) | 20 (32%) | 0.32 | 27 (38%) | 7 (27%) | 0.31 | 16 (39%) | 18 (32%) | 0.48 |

| Sour/Bitter taste | 7 (18%) | 5 (8%) | 0.12 | 9 (13%) | 2 (8%) | 0.49 | 7 (17%) | 4 (7%) | 0.13 |

| Reflux NOS | 8 (21%) | 21 (34%) | 0.17 | 23 (32%) | 5 (19%) | 0.21 | 12 (29%) | 16 (29%) | 0.94 |

| Globus | 1 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 0.59 | 3 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0.93 | 2 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 0.75 |

| Chest pain | 3 (8%) | 3 (5%) | 0.53 | 5 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 0.56 | 3 (7%) | 3 (5%) | 0.69 |

| Epigastric pain | 9 (24%) | 9 (15%) | 0.25 | 13 (18%) | 3 (12%) | 0.43 | 7 (17%) | 9 (16%) | 0.90 |

| Sinusitis | 1 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 0.87 | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.56 | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 0.57 |

| Cough | 7 (18%) | 6 (10%) | 0.21 | 9 (13%) | 3 (12%) | 0.88 | 7 (17%) | 5 (9%) | 0.23 |

| SOB | 4 (11%) | 4 (7%) | 0.47 | 4 (6%) | 3 (12%) | 0.38 | 4 (10%) | 3 (5%) | 0.45 |

| Postnasal drip | 2 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 0.63 | 2 (3%) | 2 (8%) | 0.29 | 2 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 1.00 |

| Hoarseness | 5 (13%) | 6 (10%) | 0.59 | 8 (11%) | 1 (4%) | 0.44 | 3 (7%) | 6 (11%) | 0.57 |

| Asthma | 3 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 1.00 | 8 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0.10 | 5 (12%) | 3 (5%) | 0.28 |

P-values calculated with student’s T-test (age), Pierson’s chi-squared or Fisher‘s exact test (all other dichotomous variables).

SD = standard deviation. NOS = not otherwise specified. SOB = shortness of breath.

Ninety-nine out of 100 patients underwent a diagnostic EGD as part of their initial GERD evaluation prior to 24-hour pH monitoring. Endoscopic evidence of GERD was found in 35% of patients with a positive DeMeester score compared to only 8% of those with a negative DeMeester score (p<0.01, Table 1). No differences in the frequency of endoscopic evidence of GERD were noted between patients with positive SSI or SI scores.

Heartburn was more common among the positive DeMeester patients compared to negative DeMeester patients (63% vs. 40%, p=0.02), however there were no other significant associations between any given symptom and the results of the pH study using any of the three scoring systems (Table 1).

Sixty-nine percent of patients with esophageal GERD symptoms had a positive DeMeester score compared to 29% of patients with extraesophageal symptoms (p<0.01); however, there were no differences in the results of the studies between patients with esophageal versus extraesophageal symptoms when SSI and SI scores were used (Table 2). When patients were grouped by response to acid-reducing medications, there were no differences in the frequency of positive studies using DeMeester, SSI, or SI scores (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring grouped by history of GERD and response to acid-reducing medications

| Symptoms of GERD | Response to Acid-Reducing Medication | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esophageal (n=83) |

Extra- esophageal (n=17) |

P- value* |

Complete (n=6) |

None (n=45) |

Partial (n=38) |

Relapse (n=12) |

P- value* |

|

| Positive DeMeester | 57 (69%) | 5 (29%) | <0.01 | 4 (67%) | 26 (58%) | 25 (66%) | 7 (58%) | 0.92 |

| Positive SSI | 21 (25%) | 5 (29%) | 0.79 | 1 (17%) | 12 (27%) | 8 (21%) | 5 (42%) | 0.42 |

| Positive SI | 48 (58%) | 8 (47%) | 0.33 | 4 (67%) | 21 (47%) | 24 (63%) | 7 (58%) | 0.47 |

P-values calculated with Fisher’s exact test (if <10 per group) or Pierson Chi-squared test (if ≤10 per group).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was then performed to assess the influence of three common clinical parameters on the outcome of the pH monitoring studies. History of esophageal symptoms, endoscopic evidence of GERD, and response to acid-reducing medications were used as the independent variables, and the model was repeated three times using either positive DeMeester score, positive SSI score, or positive SI score as the dependent variable. Esophageal symptoms (OR 6.36, 95% CI 1.80-22.41) and endoscopic evidence of GERD (OR 6.71, 95% CI 1.69-26.58) significantly increased the risk of having a positive DeMeester score (p<0.01); however, this was not observed when SSI and SI scores were used to define a positive study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

| DeMeester ≥14.7 (p<0.01) |

Symptom Sensitivity Index (SSI) ≥10% (p=0.73) |

Symptom Index (SI) ≥50% (p=0.42) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Typical GERD Symptoms | 6.36 (1.80–22.41) | <0.01 | 0.77 (0.23–2.55) | 0.67 | 1.48 (0.49–4.45) | 0.49 |

| Endoscopic GERD | 6.71 (1.69–26.58) | <0.01 | 1.20 (0.42–3.46) | 0.74 | 1.86 (0.67–5.12) | 0.23 |

| Response to Medication | ||||||

| None | Omitted (reference variable) | Omitted (reference variable) | Omitted (reference variable) | |||

| Complete | 1.29 (0.18–9.48 | 0.80 | 0.53 (0.06–5.05) | 0.58 | 2.08 (0.34–12.81) | 0.43 |

| Partial | 0.91 (0.33–2.57) | 0.86 | 0.74 (0.26–2.12) | 0.58 | 1.86 (0.73–4.74) | 0.20 |

| Relapse of symptoms | 0.53 (0.13–2.22) | 0.39 | 2.27 (0.56–9.26) | 0.25 | 1.59 (0.40–6.49) | 0.52 |

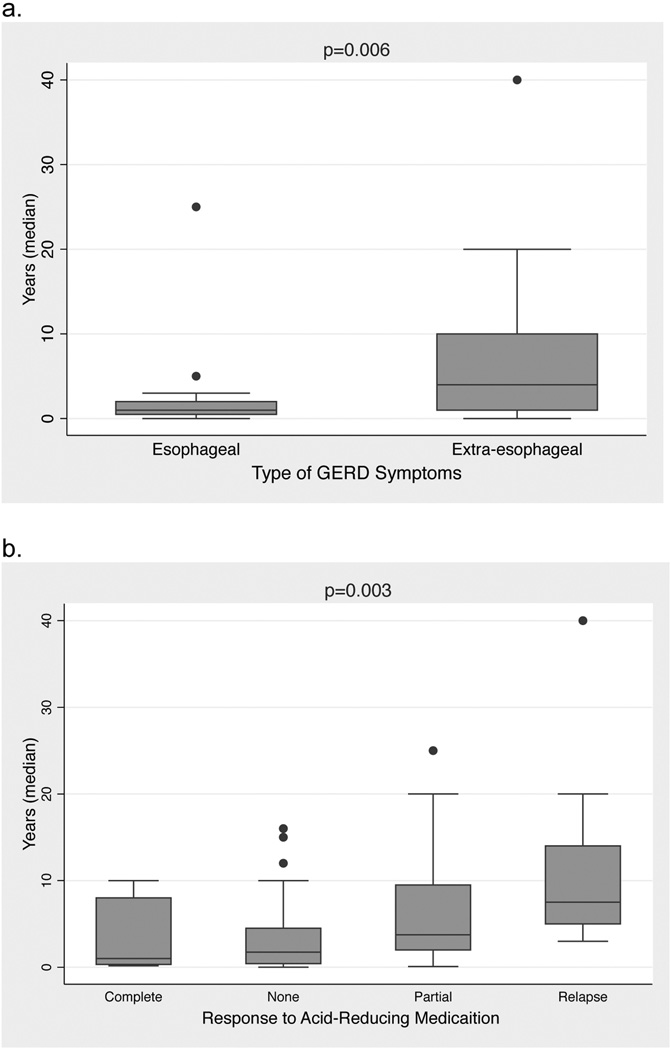

Finally, duration of acid-reducing medication treatment prior to referral for pH monitoring was compared between patients with esophageal vs. extraesophageal symptoms and also by response to acid-reducing medication. Patients with a history of esophageal symptoms were treated significantly longer than those with extraesophageal symptoms (median 4 years, range 0–40 years vs. median 1 year, range 0–25 years, p=0.01, Figure 1a). When grouped by medication response, patients who had a complete response had the shortest duration of treatment prior to testing (median 1.0 year, range 0.2-10.0), followed by no response (median 2.0 years, range 0-16.0), partial response (median 3.80 years, range 0.10 to 25), and finally relapse of symptoms (median 7.50 years, range 3.00-40.00) (p<0.01, Figure 1b). In total, 536 person-years of acid-reducing medication were prescribed prior to pH testing, of which 151 (28%) were prescribed to patients who had a negative DeMeester score.

Figure 1.

Box plots showing median duration of acid-reducing therapy prior to performing 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring with patients grouped by (a) history of GERD (esophageal vs. extra-esophageal symptoms), and (b) response to acid-reducing medications. P-values were calculated with the Wilcoxon rank sum test (a) and the Kruskal-Wallis test (b).

DISCUSSION

GERD is the most common gastrointestinal diagnosis encountered by physicians in outpatient clinics [3], yet due to the myriad of ways the disease can manifest and the variety of other potentially serious conditions that can present with GERD-like symptoms, arriving at an accurate diagnosis can be frustratingly difficult. Twenty-four hour esophageal pH monitoring is an attractive method to objectively diagnose GERD at relatively low cost and good patient tolerability. However, a major limitation of this test is the lack of consensus on which scoring system results in the most accurate diagnosis of GERD. Therefore, in this study we employed three commonly used systems (DeMeester score, SSI, and SI) in a side-by-side fashion to allow for direct comparisons between all three systems.

Our findings suggest that the recommendation to perform pH monitoring only after a failed eight-week empiric trial of twice-daily PPIs and a negative EGD [16, 17] may require reconsideration. We found that the response to empiric trials of acid-reducing medication had no correlation with the results of the pH monitoring studies. Furthermore, patients who failed an empiric trial of medication reported being treated for a period that far exceeds the recommended eight-week course. Finally, we found that nearly one-third of the person-years of acid-reducing medication that were prescribed belonged to patients who ultimately had no evidence of GERD on pH monitoring, thus imposing a substantial costly and potentially hazardous burden on those patients.

The multivariate logistic regression model was included to determine whether the three scoring systems were able to identify patients that met common clinical diagnostic criteria for GERD. In both the univariate and multivariate analyses, we saw that esophageal symptoms and endoscopic evidence of GERD were strongly associated with a positive DeMeester score; however, this was no longer observed when SSI and SI scores were used to define a positive study. One possible explanation for this is that the SSI and SI scores rely on correlation between patients’ symptoms and reflux events. As such, these scoring symptoms may not work as well for patients with extraesophageal symptoms since they are often unaware that their symptoms are associated with reflux. The SAP scoring system can potentially mitigate this issue by accounting for statistical associations between the temporality of symptoms and reflux events and not simply the total numbers of each [30]. Although we were unable to tabulate SAP scores in this report due to limitations of the equipment that was used during the study period, it will be evaluated in future studies.

Several authors have documented the misuse of PPIs among patients who either did not meet established criteria for requiring acid-suppressive therapy or for whom a less powerful agent would have sufficed [31–34]. Gawron et al recently performed a survey of 90 patients who had a negative pH monitoring study and found that 42% of them continued to use PPIs afterwards and only 19% recalled being told to discontinue them [35]. While PPIs are generally well tolerated, they have been linked to several rare but serious side effects such as an increased risk of community-acquired pneumonia, gastric polyps, gastric hyperplasia, hypomagnesemia, iron and B12 deficiencies in the elderly, increased risk of fractures, and a potential interaction with clopidogrel [36–39]. Although many of the early concerns regarding these side effects have not been validated on recent long-term follow-up studies [37, 39], all medications have a risk of side effects and associated costs. Therefore, every effort should be made to avoid prescribing medications unnecessarily.

Several investigators have previously noted a lack of correlation between patients’ symptoms and the presence of GERD. In a review of 336 consecutive patients who filled out the validated gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire (GerdQ) prior to undergoing pH monitoring, Chan et al found that only a history of heartburn, hiatal hernia, and male gender were associated with an abnormal pH study [40]. However, these questions alone were unable to accurately predict the presence of GERD. Similarly, Lacy et al found that only the GerdQ subscale for regurgitation was positively associated with an abnormal pH study [41]. In a review of 397 patients who were diagnosed with a primary esophageal motility disorder (PEMD), Patti et al found that 25% of patients with a PEMD were previously treated with PPIs for what was presumed to be GERD, and they also found that symptoms alone were unable to distinguish GERD from PEMDs [42]. Therefore, all patients with a negative pH monitoring study should be promptly referred to a specialist in esophageal disorders for further workup of their symptoms.

There are several limitations of this study. First, patients were selected from those referred for pH monitoring and not from all patients suffering from GERD symptoms. It is likely that many patients who responded well to acid-reducing medication were never referred for pH monitoring, thus introducing selection bias that skewed the study population towards “difficult” cases whose symptoms were refractory to medical therapy. Thus, it is possible that these findings may be applicable only to more complex cases where the symptoms are non-specific and the diagnosis is less clear. Second, pH monitoring using a traditional 2-channel system only offers 24 hours of observational data and cannot detect non-acid reflux events. Wireless (Bravo) pH monitoring systems enable clinicians to extend the study period from 24 hours to 48 hours, which has been shown to increase the percentage of patients with positive SAP scores from 34% to 48% [43]. Tseng et al also showed that 48-hour wireless studies identified 22% more patients with DeMeester scores greater than 14.7 when compared to a single 24-hour period [44]. However, there are specific drawbacks to the wireless Bravo probe. Iqbal et al discussed the increased incidence of false positive studies due to premature release of the probe from the esophageal wall [45]. Moreover, Ayazi et al showed that the discrepancy in 24-hour versus 48-hour testing is likely associated with the degree of deterioration of the lower esophageal sphincter and their group concluded that fluctuations in pH monitoring may be associated with less severe reflux [46]. Another major drawback to the 48-hour and longer systems is that these implantable devices currently lack the ability to measure non-acid reflux. Impedance monitoring which is currently only available on the 24-hour wired system enables detection of non-acid reflux. Many would argue that acid-reducing medications are unlikely to provide any benefit for patients with non-acid reflux and, in fact, they have been shown to actually increase the frequency of non-acid reflux events [47, 48]. Ultimately, subgroup analysis is warranted to determine the benefits of medical and surgical management for all types of reflux.

These data highlight the limited ability of any single evaluation tool (symptoms, empiric trials of acid-reducing medication, endoscopy, and ambulatory pH monitoring) to accurately diagnose GERD in all patients. Future studies focusing on the use of multiple scoring systems to correlate with both objective and subjective endpoints are needed. Furthermore, it would be interesting to examine how these various preoperative evaluation tools correlate with outcomes of patients who ultimately undergo anti-reflux surgery.

In conclusion, we have shown that extraesophageal GERD symptoms and response to empiric trials of acid-reducing therapy are poor predictors of the presence of GERD as diagnosed by pH monitoring studies. Moreover, DeMeester score and endoscopy performed better than SSI and SI at correctly diagnosing pathologic GERD. Delayed referral for esophageal pH monitoring often results in lengthy periods of unnecessary medical therapy. Patients with normal pH monitoring studies warrant further investigation for alternative causes of their symptoms.

Acknowledgments

GRANT SUPPORT: This investigation was supported in part by grant TL1RR024998 of the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Kleiman, Mr. Sporn, and Drs. Beninato, Metz, Crawford, Fahey and Zarnegar have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, Graham DY, Richardson P, Genta RM, Rabeneck L. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1692–1699. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaheen NJ, Hansen RA, Morgan DR, Gangarosa LM, Ringel Y, Thiny MT, Russo MW, Sandler RS. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases, 2006. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Encinosa W. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Hospitalizations in 1998 and 2005: Statistical Brief #44. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs, Rockville (MD) 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. quiz 1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moraes-Filho J, Cecconello I, Gama-Rodrigues J, Castro L, Henry MA, Meneghelli UG, Quigley E. Brazilian consensus on gastroesophageal reflux disease: proposals for assessment, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mujica VR, Rao SS. Recognizing atypical manifestations of GERD. Asthma, chest pain, and otolaryngologic disorders may be due to reflux. Postgrad Med. 1999;105:53–55. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.01.498. 60, 63-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maceri DR, Zim S. Laryngospasm: an atypical manifestation of severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1976–1979. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200111000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong WM, Fass R. Extraesophageal and atypical manifestations of GERD. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(Suppl 3):S33–S43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiBaise JK, Olusola BF, Huerter JV, Quigley EM. Role of GERD in chronic resistant sinusitis: a prospective, open label, pilot trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mays EE, Dubois JJ, Hamilton GB. Pulmonary fibrosis associated with tracheobronchial aspiration. A study of the frequency of hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux in interstitial pulmonary fibrosis of obscure etiology. Chest. 1976;69:512–515. doi: 10.1378/chest.69.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobin RW, Pope CE, 2nd, Pellegrini CA, Emond MJ, Sillery J, Raghu G. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1804–1808. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9804105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahrilas PJ. Clinical practice. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1700–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qadeer MA, Phillips CO, Lopez AR, Steward DL, Noordzij JP, Wo JM, Suurna M, Havas T, Howden CW, Vaezi MF. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for suspected GERD-related chronic laryngitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2646–2654. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaezi MF, Hicks DM, Abelson TI, Richter JE. Laryngeal signs and symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a critical assessment of cause and effect association. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:333–344. doi: 10.1053/s1542-3565(03)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamal A, Vaezi MF. Diagnosis and initial management of gastroesophageal complications. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:799–820. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1392–1413. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.044. 1413 e1391-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galmiche JP, Scarpignato C. Modern diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1308–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter JE. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring. Am J Med. 1997;103:130S–134S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuchs KH, DeMeester TR, Albertucci M. Specificity and sensitivity of objective diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surgery. 1987;102:575–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behar J, Biancani P, Sheahan DG. Evaluation of esophageal tests in the diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeMeester TR, Johnson LF. The evaluation of objective measurements of gastroesophageal reflux and their contribution to patient management. Surg Clin North Am. 1976;56:39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)40834-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarani B, Gleiber M, Evans SR. Esophageal pH monitoring, indications, and methods. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:200–206. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Smout AJ. Symptom association analysis in ambulatory gastro-oesophageal reflux monitoring. Gut. 2005;54:1810–1817. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.072629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson LF, Demeester TR. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring of the distal esophagus. A quantitative measure of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1974;62:325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Development of the 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring composite scoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8(Suppl 1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198606001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breumelhof R, Smout AJ. The symptom sensitivity index: a valuable additional parameter in 24-hour esophageal pH recording. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward BW, Wu WC, Richter JE, Lui KW, Castell DO. Ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. Technology searching for a clinical application. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8(Suppl 1):59–67. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198606001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weusten BL, Roelofs JM, Akkermans LM, Van Berge-Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. The symptom-association probability: an improved method for symptom analysis of 24-hour esophageal pH data. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1741–1745. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aanen MC, Bredenoord AJ, Numans ME, Samson M, Smout AJ. Reproducibility of symptom association analysis in ambulatory reflux monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2200–2208. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naunton M, Peterson GM, Bleasel MD. Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25:333–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2000.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nardino RJ, Vender RJ, Herbert PN. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3118–3122. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heidelbaugh JJ, Goldberg KL, Inadomi JM. Overutilization of proton pump inhibitors: a review of cost-effectiveness and risk [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 2):S27–S32. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidelbaugh JJ, Goldberg KL, Inadomi JM. Magnitude and economic effect of overuse of antisecretory therapy in the ambulatory care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:e228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gawron AJ, Rothe J, Fought AJ, Fareeduddin A, Toto E, Boris L, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Many patients continue using proton pump inhibitors after negative results from tests for reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali T, Roberts DN, Tierney WM. Long-term safety concerns with proton pump inhibitors. Am J Med. 2009;122:896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Yuan YC, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW. Recent safety concerns with proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:93–114. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182333820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freston JW. Long-term acid control and proton pump inhibitors: interactions and safety issues in perspective. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:51S–55S. discussion 55S-57S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomson AB, Sauve MD, Kassam N, Kamitakahara H. Safety of the long-term use of proton pump inhibitors. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2323–2330. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i19.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan K, Liu G, Miller L, Ma C, Xu W, Schlachta CM, Darling G. Lack of correlation between a self-administered subjective GERD questionnaire and pathologic GERD diagnosed by 24-h esophageal pH monitoring. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:427–436. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lacy BE, Chehade R, Crowell MD. A prospective study to compare a symptom-based reflux disease questionnaire to 48-h wireless pH monitoring for the identification of gastroesophageal reflux (revised 2-26-11) Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1604–1611. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patti MG, Gorodner MV, Galvani C, Tedesco P, Fisichella PM, Ostroff JW, Bagatelos KC, Way LW. Spectrum of esophageal motility disorders: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Arch Surg. 2005;140:442–448. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.5.442. discussion 448-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chander B, Hanley-Williams N, Deng Y, Sheth A. 24 Versus 48-hour bravo pH monitoring. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:197–200. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31822f3c4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tseng D, Rizvi AZ, Fennerty MB, Jobe BA, Diggs BS, Sheppard BC, Gross SC, Swanstrom LL, White NB, Aye RW, Hunter JG. Forty-eight-hour pH monitoring increases sensitivity in detecting abnormal esophageal acid exposure. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.07.011. discussion 1051-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iqbal A, Lee YK, Vitamvas M, Oleynikov D. 48-Hour pH monitoring increases the risk of false positive studies when the capsule is prematurely passed. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:638–641. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0142-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayazi S, Hagen JA, Zehetner J, Banki F, Augustin F, Ayazi A, DeMeester SR, Oh DS, Sohn HJ, Lipham JC, DeMeester TR. Day-to-day discrepancy in Bravo pH monitoring is related to the degree of deterioration of the lower esophageal sphincter and severity of reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2219–2223. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1529-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamhankar AP, Peters JH, Portale G, Hsieh CC, Hagen JA, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Omeprazole does not reduce gastroesophageal reflux: new insights using multichannel intraluminal impedance technology. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.08.001. discussion 897-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blonski W, Vela MF, Castell DO. Comparison of reflux frequency during prolonged multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring on and off acid suppression therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:816–820. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318194592b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]