Abstract

Aims

To provide evidence on the comparative effectiveness of oral diabetes drug combinations.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, observational cohort study of glycosylated hemoglobin change in outpatients newly exposed to dual- or triple-drug oral diabetes treatment.

Results

Adjusted response to a second drug added to metformin ranged from 0.85 to 1.21% glycosylated hemoglobin decline. Response to a third drug was smaller (0.53–0.91%). Higher baseline glycosylated hemoglobin was associated with larger response; sulfonylurea effectiveness declined over time; and thiazolidinediones were more effective in obese patients and women.

Conclusion

Observational data provide results qualitatively consistent with the limited available randomized data on diabetes drug effectiveness, and extend these findings into common clinical scenarios where randomized data are unavailable. Sex and BMI influence the comparative effectiveness of diabetes drug combinations.

Keywords: biomarker, combination therapy, comparative effectiveness, diabetes, HbA1c

The effectiveness of Type 2 diabetes drugs are typically assessed in terms of improvement in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), which reflects a patient’s average blood glucose. Confidence in HbA1c as a biomarker is great enough that diabetes drugs are approved and their efficacy is described based on their ability to lower it, although, there is now growing concern that drug trials need to go further to address adverse events and effects on macrovascular risk [1]. Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that improving HbA1c is an important clinical goal because reducing it by 1 percentage point leads to a 40% lower risk of microvascular complications [2].

Even for HbA1c as a biomarker, data on comparative effectiveness of diabetes medications in combination therapy are scant, especially in extended therapy and in subgroups such as the obese [3,4]. This is in contrast to monotherapy, where such effectiveness questions have been much better studied. The reason for this is that head-to-head pragmatic clinical trials are rare in diabetes and have mainly studied monotherapy [3,5,6]. Since diabetes is a chronic disease in which many patients progress to combination therapy, these are major evidence gaps. Meta-analysis of the existing dual-therapy studies has been limited by low precision of results, high levels of study heterogeneity and limited ability to study differences in effectiveness between patient subgroups or in the long term [7]. The GRADE clinical trial is intended to answer some of these questions, but this 7-year study has only just begun recruitment [8].

There are likely to be clinically important differences between drug combinations. Data from monotherapy trials indicate that sulfonylureas may be more effective than alternatives in the short term, but they may lose their effectiveness after several months [3]; that thiazolidinediones are more effective in obese patients and in women; and, finally, that dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors may be less effective than the other widely used oral agents [6,9]. However, it is unknown whether these claims are true in the clinically important dual- and triple-therapy settings.

The objective of this study was to measure the change in HbA1c following the prescription of combinations of the most popular oral diabetes drugs in an observational cohort to assess their comparative effectiveness in common clinical scenarios where randomized data are limited.

Methods

A longitudinal retrospective cohort study was completed using the Health Information Network database. The goal was to study the comparative effect of diabetes medications on the change in HbA1c.

Data source

The Health Information Network is a general practitioner electronic medical record database in the UK that, at the time of this analysis, consisted of longitudinal healthcare data from 532 general practices. The database includes over 10 million patients, of whom approximately 4 million are currently active. The Health Information Network patients are representative of the UK noninstitutionalized population [10]. General practitioners have a financial incentive to order and record HbA1c values, supporting a high rate of capture of HbA1c data [11].

Exposure definition, eligibility criteria & covariates

Patients were followed from the time of initiation of a drug of interest until death, transfer out of the practice or at the end of the data collection period (defined as 1 January 2012 for this analysis). Exposure was defined as the class of oral diabetes drug used: sulfonylurea, biguanide (specifically metformin), DPP-4 inhibitor or thiazolidinedione.

To be eligible, patients needed a baseline HbA1c measured within 3 months prior or up to 7 days after initiation of a diabetes drug, and at least one follow-up HbA1c measured between 7 days and 1 year after drug initiation. Analysis was restricted to practices that measured on average >1.5 HbA1c assays per patient per year. By 2003, 50% of practices met this standard and by 2007, 90% did. Follow-up period extended from 1 January 2003 (the first date at which sufficient HbA1c data were available for some practices) to 1 January 2012. In sensitivity analyses, the main model was repeated while varying the threshold for including practices from 0 to 2 measurements of HbA1c per patient per year.

Exposure to a drug was defined as creation of a prescription for that drug. Individuals were assumed to be exposed from the date of a prescription until 30 days after it would have run out, assuming complete adherence. The database only included prescribing data, not dispensing data. In sensitivity analysis, patients were considered exposed only if two or more prescriptions for the drug were received.

Further details of eligibility differed slightly for two subcohorts. The first subcohort was dual therapy. In this subcohort, patients had to be on a background drug of interest (metformin or sulfonylurea) for at least 180 days continuously up to cohort entry, and they were required to have no other diabetes drug for 365 days prior. Cohort entry was defined as addition of a second drug to ongoing therapy with the first drug (e.g., a sulfonylurea added to a metformin regimen). Included patients also had to be registered for at least 365 days prior to the start of the first drug to allow full ascertainment of prior therapies.

The second subcohort was defined as triple therapy. This subcohort was defined as described above for dual therapy, except that a second background diabetes drug also was given for at least 180 days prior to addition of the third drug and the start of follow-up.

Baseline covariates were measured in the year prior to entry; for variable quantities, such as BMI and HbA1c, the last value measured within 3 months prior to cohort entry (i.e., closest in time to the start of the follow-up for this study) until 1 week after was used. Analysis was restricted to patients for whom baseline BMI and HbA1c were available. As a result of these restrictions, there were no missing data.

Outcome determination

The primary outcome was the difference between baseline and subsequent HbA1cs. HbA1c in this paper is reported in percentage units and changes in HbA1c are reported as the absolute change in percentage units. A secondary outcome was the percentage of patients with an average HbA1c of 7.5 or less between 6 months and 1 year of follow-up. For the primary analysis, any HbA1c measured more than 7 days after cohort entry contributed to the outcome data. Because HbA1c is measured frequently in clinical practice, monitoring of HbA1c is a quality of outcomes measure in the UK and the cohort was restricted to practices that reported HbA1c regularly, therefore ascertainment bias was expected to be minimal [12,13].

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics assessed distributions for all variables. Next, linear generalized least squares regressions were performed with HbA1c change as the dependent variable. Separate models were considered for each subcohort.

For the descriptive statistics, since the large comparison groups meant that almost all differences would be statistically significant, standardized mean differences were used instead of p-values. This measure expresses the difference between two groups on a given parameter as the difference between groups divided by the pooled standard deviation. Standardized mean differences of >0.1 are conventionally taken to indicate substantial differences [14].

Each model included exposure, age, sex, year of treatment initiation, baseline BMI, baseline HbA1c, gender and date (as a continuous variable) of HbA1c measurement as covariates. All variables were modeled as interactions with date. In addition, the interactions of the exposure category with each baseline characteristic were included in the model BMI (measured as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was defined as a categorical variable (<30 as normal and >30 as obese). BMI was also used as a continuous variable in sensitivity analysis; the categorical variable is used to facilitate interpretation of the model.

The mixed linear model was hierarchical at the level of patients with a random intercept for patients and a random component to variability in the HbA1c trend. The effect of follow-up time was flexibly modeled using a spline, with knots manually set at 3-month intervals. Full model results are provided in Supplementary Materal (see online at www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/cer.13.87); results in the main text are presented as predicted change in HbA1c for a 60-year-old patient with baseline HbA1c 8.5 of specified gender and BMI category.

As secondary analysis, all covariates were included in a simpler linear model, giving adjusted change from baseline HbA1c to average HbA1c measured between 6 and 12 months after treatment initiation. The correlation between average 6–12-month HbA1c and 6–12-month BMI was also calculated for each drug class. In further analysis, the percentage of patients with average HbA1c of 7.5 or less between 6 and 12 months was used as an outcome in logistic regression models with the same covariates as above. This particular cutoff was chosen as it is widely used goal in clinical practice in the UK.

All analyses were performed as intention-to-treat, so participants were not censored by addition of other diabetes drugs after cohort entry. In sensitivity analysis, patients were censored as soon as one of the drugs was stopped or any additional diabetes drug was added. Further sensitivity analysis predicted results for baseline HbA1c 7 and 10. Another sensitivity analysis divided exposure into tertiles of initial dose to assess for dose–response effect.

Data were analyzed using SAS software (SAS Institute, NC, USA) and R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pennsylvania (PA, USA) and Weill Cornell Medical College (NY, USA).

Results

A total of 353,794 individuals in the database were potentially eligible for the study, as they had two or more HbA1c values recorded. A total of 45,178 individuals were eligible based on exposure to dual or triple therapy while meeting the inclusion criteria for duration of baseline treatment and frequency of HbA1c reporting within practices. After application of other inclusion criteria – availability of baseline HbA1c and BMI data and at least one follow-up HbA1c within a year of starting therapy – 28,914 eligible cases remained.

Among these patients, dual-therapy regimens, in which a second drug was added to metformin, most often used sulfonylurea (n = 8807), thiazolidinedione (n = 4422) or a DPP-4 inhibitor (n = 1278). Dual-therapy regimens, in which a drug was added to sulfonylurea, most often used metformin (n = 3922) or thiazolidinedione (n = 462). Four triple-therapy regimens were common: thiazolidinedione added to metformin and sulfonylurea (n = 5853); DPP-4 added to metformin and sulfonylurea (n = 1895); sulfonylurea added to metformin and thiazolidinedione (n = 1816); and DPP-4 added to metformin and thiazolidinedione (n = 459). Regimens including DPP-4 inhibitors were initiated more recently than other combinations (Tables 1–4).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for a second drug added to metformin monotherapy.

| Variable | Sulfonylurea | SD | Thiazolidinedione | SD | SDiff | DPP-4 | SD | SDiff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 8807 | – | 4422 | – | – | 1278 | – | – |

| Year | 2008 | 2 | 2006 | 2 | 0.65 | 2010 | 1 | −0.99 |

| Baseline HbA1c (% units) | 8.64 | 1.41 | 8.46 | 1.30 | 0.13 | 8.46 | 1.26 | 0.13 |

| Baseline HbA1c to cohort entry (days) | 21 | 18 | 21 | 18 | 0.01 | 21 | 17 | 0.02 |

| Age (years) | 62 | 11 | 60 | 11 | 0.22 | 60 | 11 | 0.23 |

| Female sex (%) | 40 | – | 38 | – | 0.03 | 40 | – | −0.01 |

| Baseline creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.98 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.27 | −0.04 | 0.89 | 0.22 | 0.31 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 32.8 | 6.1 | 33.7 | 5.9 | −0.15 | 34.4 | 6.7 | −0.26 |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | 35 | 26 | 43 | 27 | −0.31 | 19 | 11 | 0.65 |

| No new treatment at 1 year (%) | 94 | – | 93 | – | 0.06 | 80 | – | 0.58 |

DDP-4: Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4; HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin; SD: Standard deviation; SDiff: Standardized difference compared with metformin monotherapy.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics for a third drug added to metformin/thiazolidinedione dual therapy.

| Variable | Sulfonlyurea | SD | DPP-4 | SD | SDiff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 1816 | – | 459 | – | – |

| Year | 2008 | 2 | 2010 | 1 | −1.17 |

| Baseline HbA1c (% units) | 8.72 | 1.48 | 8.27 | 1.41 | 0.31 |

| Baseline HbA1c to cohort entry (days) | 22 | 20 | 21 | 18 | 0.09 |

| Age (years) | 59 | 11 | 61 | 10 | −0.13 |

| Female sex (%) | 31 | – | 36 | – | −0.10 |

| Baseline creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.98 | 0.27 | 0.96 | 0.29 | 0.09 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 34.8 | 6.7 | 34.9 | 7.0 | −0.02 |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | 22 | 20 | 11 | 9 | 0.62 |

| No new treatment at 1 year (%) | 92 | – | 79 | – | 0.41 |

DDP-4: Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4; HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin; SD: Standard deviation; SDiff: Standardized difference compared with sulfonylurea added to metformin/thiazolidinedione dual therapy.

As the primary model was intention-to-treat, the duration of follow-up was limited only by death, transfer out of a practice or the end of the time period covered by the database. Under those criteria, average length of follow-up ranged from 9 to 19 months for DPP-4 inhibitors and from 22 to 43 months for the other drugs. Rates of treatment for 1 year without any further change in therapy were 81–94% for non-DPP-4 drugs and 79–85% for DPP-4 inhibitors (Tables 1–4).

Unadjusted change in HbA1c differed considerably, with much of the difference reduced with adjustment by baseline HbA1c (Tables 5–8). Multivariable models revealed that BMI, sex and baseline HbA1c were significant predictors of change in HbA1c. Higher baseline HbA1c was associated with greater absolute response to treatment, with a 1% increase in baseline HbA1c translating to approximately 0.5% greater decrease when treatment was started. There were no clinically significant variations in the strength of this interaction from drug class to drug class (Supplementary Material Sections S1–S2), and in sensitivity analyses, the comparative effectiveness of the drug classes did not change at higher or lower HbA1cs.

Table 5.

Average outcomes at 6–12 months after treatment was added to metformin monotherapy.

| Drug and population stratum |

Unadjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Unadjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfonylurea | ||||

| All patients | −1.03 (−1.05 to −1.00) | – | 56 (55–57) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −1.10 (−1.16 to −1.05) | −1.08 (−1.13 to −1.03) | 61 (59–64) | 63 (61–66) |

| Female BMI <30 | −0.85 (−0.93 to −0.78) | −0.89 (−0.95 to −0.84) | 57 (54–59) | 57 (54–60) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −1.12 (−1.17 to −1.07) | −1.04 (−1.09 to −1.00) | 53 (52–55) | 62 (60–64) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −0.91 (−0.96 to −0.85) | −0.85 (−0.90 to −0.80) | 53 (51–56) | 56 (53–59) |

| Thiazolidinedione | ||||

| All patients | −0.90 (−0.93 to −0.88) | – | 49 (48–50) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.73 (−0.78 to −0.69) | −1.00 (−1.09 to −0.91) | 45 (43–47) | 63 (58–67) |

| Female BMI <30 | −0.80 (−0.87 to −0.73) | −1.08 (−1.18 to −0.98) | 49 (47–52) | 66 (61–71) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −1.00 (−1.05 to −0.96) | −1.13 (−1.21 to −1.05) | 50 (48–52) | 67 (63–71) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −1.04 (−1.10 to −0.99) | −1.21 (−1.29 to −1.12) | 54 (52–56) | 70 (66–74) |

| Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 | ||||

| All patients | −0.82 (−0.87 to −0.78) | – | 46 (44–48) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.85 (−0.94 to −0.77) | −1.03 (−1.17 to −0.90) | 48 (44–51) | 65 (58–72) |

| Female BMI <30 | −0.79 (−0.93 to −0.65) | −0.99 (−1.15 to −0.83) | 49 (43–54) | 62 (53–70) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −0.85 (−0.93 to −0.78) | −1.00 (−1.10 to −0.90) | 46 (43–48) | 64 (58–68) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −0.76 (−0.84 to −0.67) | −0.96 (−1.07 to −0.85) | 45 (42–49) | 60 (54–66) |

HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

Table 8.

Average outcomes at 6–12 months after treatment was added to thiazolidinedione/metformin dual therapy.

| Drug and population stratum |

Unadjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Unadjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfonylurea | ||||

| All patients | −0.87 (−0.93 to −0.80) | – | 48 (46–51) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.80 (−0.94 to −0.67) | −0.84 (−0.96 to −0.72) | 48 (43–53) | 48 (42–54) |

| Female BMI <30 | −0.85 (−1.03 to −0.66) | −0.71 (−0.86 to −0.56) | 48 (40–56) | 46 (39–53) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −0.99 (−1.09 to −0.89) | −0.91 (−1.01 to −0.80) | 50 (46–53) | 54 (49–60) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −0.71 (−0.86 to −0.55) | −0.78 (−0.91 to −0.65) | 48 (43–53) | 52 (45–58) |

| Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 | ||||

| All patients | −0.53 (−0.65 to −0.40) | – | 52 (47–57) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.66 (−0.94 to −0.38) | −0.80 (−1.06 to −0.55) | 58 (45–71) | 54 (41–67) |

| Female BMI <30 | −0.80 (−1.47 to −0.14) | −0.73 (−1.02 to −0.44) | 59 (40–78) | 45 (30–60) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −0.63 (−0.80 to −0.45) | −0.69 (−0.85 to −0.53) | 51 (44–58) | 47 (39–56) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −0.24 (−0.46 to −0.02) | −0.62 (−0.81 to −0.42) | 50 (41–59) | 38 (28–49) |

HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

Interactions with BMI and sex varied considerably between drug classes but were largest for thiazolidinediones, which typically resulted in approximately 0.2% greater reductions in HbA1c for women and 0.2% greater reductions for obese patients; these interactions were independent of one another. Complete descriptions of these interactions are available in supplementary data (Supplementary Material Section S1–S2). Unless otherwise noted, all differences described in the text of the results section are statistically significant with p < 0.001.

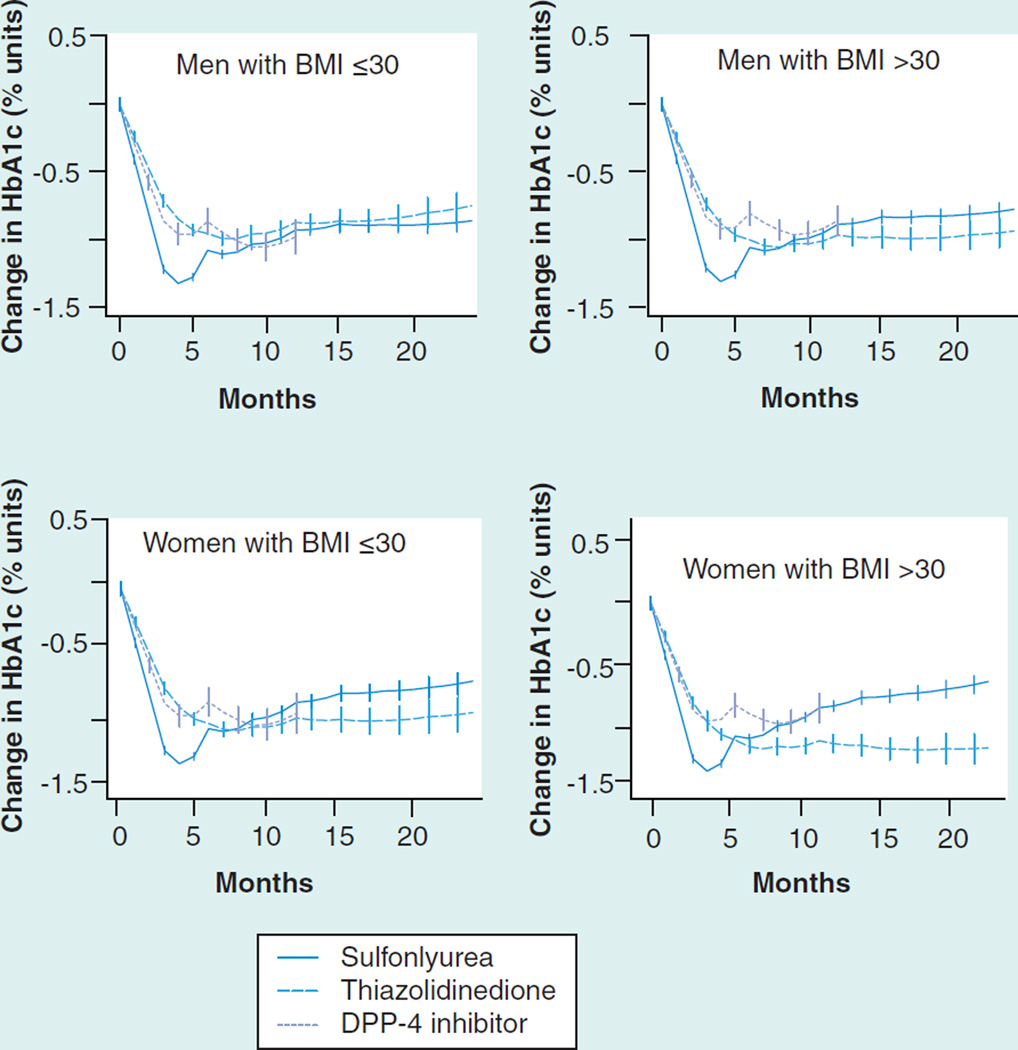

In dual therapy added to metformin, all medications were associated with adjusted decreases in HbA1c between 0.85 and 1.21% after 6 months (Table 5). Sulfonylureas were associated with the largest initial decline in HbA1c but their effect then diminished after 3 months of follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Glycosylated hemoglobin change (absolute % units) after the addition of a second agent to baseline metformin therapy.

DPP-4: Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4; HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

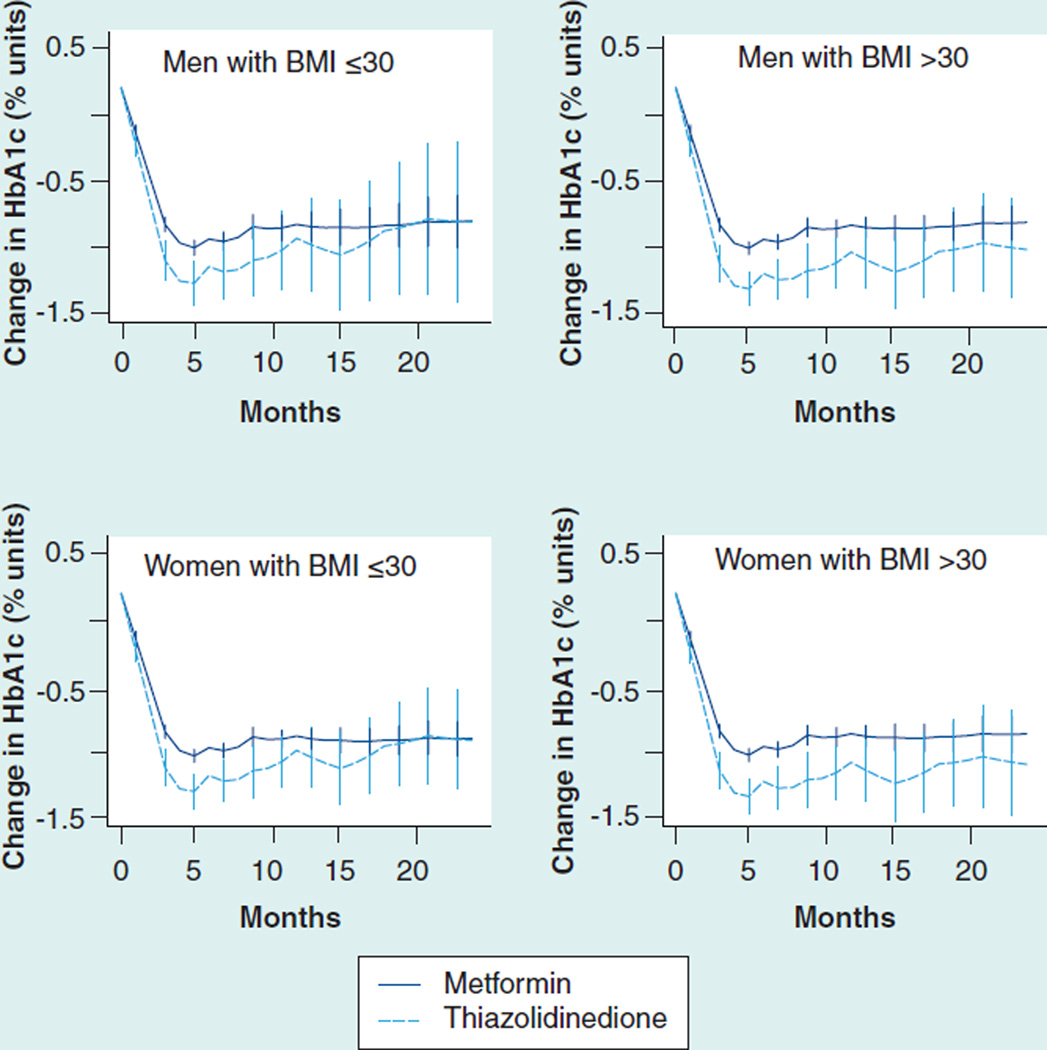

The relative effectiveness of different agents varied based on age and sex. For example, in nonobese men, thiazolidinediones and sulfonylureas resulted in nearly identical average reduction after 6 months, but in obese women thiazolidinediones were associated with a 0.36% greater reduction (Figure 2 & Table 5). Similarly, thiazolidinediones were associated with a 70% adjusted probability for obese women of achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5 after 6 months, compared with 56–60% for the other two drug classes. The increased effectiveness of thiazolidinediones at higher BMI was also seen in dual therapy with sulfonylureas (Figure 2 & Table 6).

Figure 2. Glycosylated hemoglobin change (absolute % units) after the addition of a second agent to baseline sulfonylurea therapy.

HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

Table 6.

Average outcomes at 6–12 months after treatment was added to sulfonylurea monotherapy.

| Drug and population stratum |

Unadjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Unadjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin | ||||

| All patients | −1.01 (−1.05 to −0.96) | – | 54 (53–56) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.99 (−1.06 to −0.93) | −0.79 (−0.88 to −0.70) | 53 (50–55) | 65 (58–72) |

| Female BMI <30 | −1.13 (−1.23 to −1.03) | −0.86 (−0.97 to −0.76) | 61 (57–64) | 59 (54–64) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −0.88 (−1.00 to −0.77) | −0.70 (−0.80 to −0.59) | 51 (47–55) | 51 (46–56) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −1.00 (−1.13 to −0.86) | −0.76 (−0.88 to −0.65) | 52 (46–57) | 56 (51–62) |

| Thiazolidinedione | ||||

| All patients | −1.01 (−1.05 to −0.96) | – | 54 (53–56) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.98 (−1.17 to −0.80) | −0.69 (−1.00 to −0.39) | 45 (38–53) | 55 (40–68) |

| Female BMI <30 | −1.33 (−1.56 to −1.10) | −0.79 (−1.14 to −0.45) | 52 (44–61) | 55 (39–70) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −1.86 (−2.29 to −1.42) | −1.11 (−1.45 to −0.77) | 59 (46–71) | 66 (50–79) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −1.39 (−1.76 to −1.01) | −1.21 (−1.58 to −0.85) | 46 (31–60) | 66 (49–80) |

HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

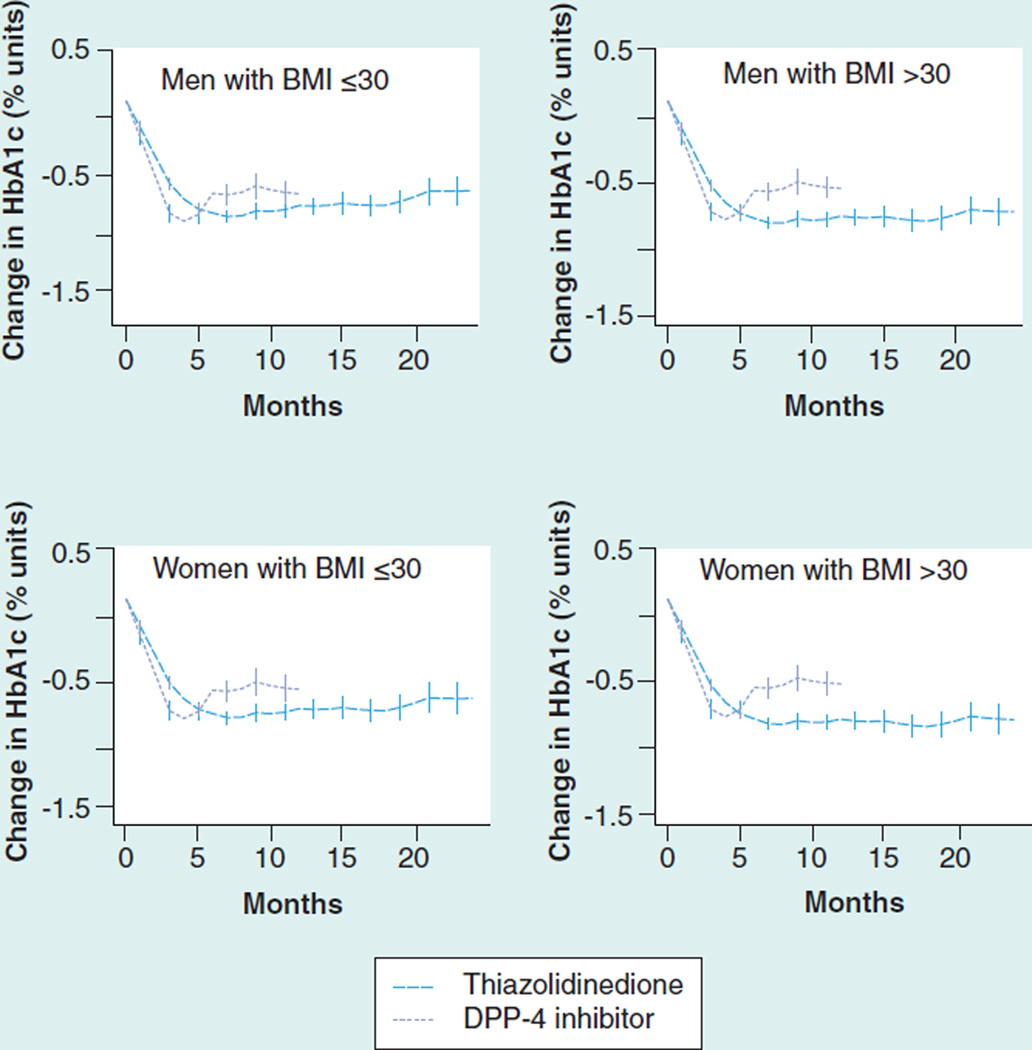

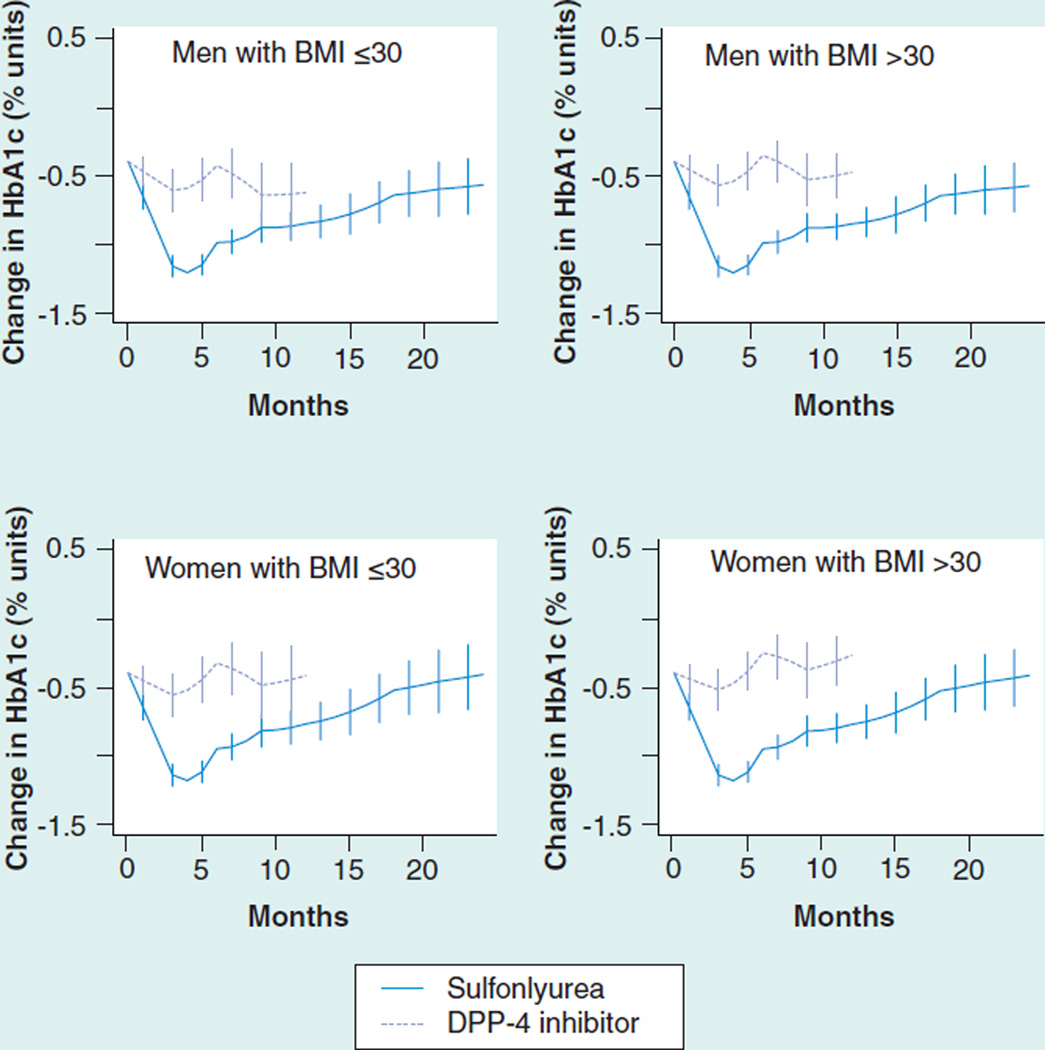

Adjusted response to a third drug ranged from 0.53 to 0.91%. As add-on therapy to a sulfonylurea/ metformin combination, thiazolidinediones were more effective than DPP-4 inhibitors, especially in obese patients and in women (Figure 3 & Table 7). The ability to study add-on therapy to a metformin/thiazolidinedione combination was limited by a small sample size for DPP-4 inhibitors (Figure 4 & Table 8). Metformin and DPP-4 inhibitors were associated with reductions in mean BMI while sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones were associated with increases of 0.37 to 0.52 units (Supplementary Material Figure S5).

Figure 3. HbA1c change (absolute % units) after the addition of a third agent to baseline sulfonylurea/metformin dual therapy.

DPP-4: Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4; HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

Table 7.

Average outcomes at 6–12 months after treatment was added to sulfonylurea/metformin dual therapy.

| Drug and population stratum |

Unadjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage units HbA1c change (95% CI) |

Unadjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

Adjusted percentage achieving goal HbA1c ≤7.5% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiazolidinedione | ||||

| All patients | −0.82 (−0.85 to −0.78) | – | 40 (39–41) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.68 (−0.73 to −0.62) | −0.65 (−0.72 to −0.58) | 37 (34–39) | 41 (38–44) |

| Female BMI <30 | −0.73 (−0.82 to −0.65) | −0.70 (−0.78 to −0.62) | 41 (38–44) | 45 (41–48) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −0.91 (−0.97 to −0.85) | −0.84 (−0.91 to −0.77) | 41 (38–43) | 52 (48–55) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −1.00 (−1.09 to −0.92) | −0.89 (−0.96 to −0.81) | 43 (40–46) | 55 (51–59) |

| Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 | ||||

| All patients | −0.80 (−0.86 to −0.74) | – | 36 (34–39) | – |

| Male BMI <30 | −0.82 (−0.93 to −0.72) | −0.62 (−0.72 to −0.53) | 38 (34–42) | 40 (36–45) |

| Female BMI <30 | −0.82 (−0.99 to −0.65) | −0.55 (−0.67 to −0.43) | 42 (35–48) | 39 (33–44) |

| Male BMI ≥30 | −0.80 (−0.90 to −0.70) | −0.61 (−0.69 to −0.52) | 36 (32–40) | 38 (34–42) |

| Female BMI ≥30 | −0.77 (−0.89 to −0.64) | −0.53 (−0.63 to −0.43) | 31 (27–36) | 36 (32–41) |

HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

Figure 4. Glycosylated hemoglobin change (absolute % units) after the addition of a third agent to baseline thiazolidinedione/metformin dual therapy.

DPP-4: Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4; HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin.

The sensitivity analyses described in the methods did not materially affect these results (Supplementary Material).

Discussion

This observational study yielded several findings that would be expected from the extensive literature on diabetes monotherapy. Sulfonylurea effectiveness declines over time; all drugs are associated with more robust effects when starting HbA1c is higher; and thiazolidinediones are more effective in obese patients and women. These consistent findings support the validity of this approach for evaluating comparative effectiveness. In verifying that these effects are present in combination therapy and quantifying them, this study also yields results of potential clinical significance.

It is already known that, although sulfonylureas are initially potent, their effectiveness declines over time as monotherapy [8,10]. These data extend that finding to common combination-therapy settings, although the decrease in effectiveness is not as great as was seen in monotherapy studies. Rates of advancement to additional therapy in the sulfonylurea–metformin dual-therapy group at 1 year were very low, making it unlikely that this difference is attributable to rescue of failing patients with other drugs. Strictly from an effectiveness standpoint, these data continue to support the utility of sulfonylureas as potent agents in combination therapy. Of note, in patients who were on sulfonylurea and had additional agents added, there was no evidence of ongoing decline in sulfonylurea effectiveness. The median duration of sulfonylurea therapy before the addition of a second agent was 2.5 years, suggesting that the decline of sulfonylurea effectiveness may stabilize in the long term.

Randomized trials have previously shown that thiazolidinediones have greater effectiveness in women and obese patients [6,9]. These data validate and extend that finding to a wide range of combination-therapy scenarios and demonstrate that it has clinically relevant implications for glycemic control. Particularly for obese women, thiazolidinediones are associated with better long-term glycemic control than alternatives.

DPP-4 inhibitors are the newest drugs evaluated here and conclusions about them are limited for two reasons. The first is relatively short duration of exposure, and the second is relatively high rates of addition of other therapies to the DPP-4 regimens, which may exaggerate their apparent effectiveness. Despite these limitations, these data suggest significant utility in dual therapy, without weight gain. However, the contribution of DPP-4 inhibitors in triple therapy may be marginal, particularly if thiazolidinediones are an acceptable alternative.

A larger point to mention is that the initial choice of a second or third agent had persistent effects on patients’ glycemic control over 2 years of follow-up. For example, in obese women the decision to use a thiazolidinedione was consistently associated with 0.3–0.4% greater absolute reductions in HbA1c and an absolute increase of 10–20% in the number of patients achieving a goal HbA1c of 7.5. Those improvements relative to other treatment choices appear to persist over at least 2 years of follow-up.

This study is also able to provide information about weight changes as a secondary outcome. Generally, the expected patterns of weight change were seen (thiazolidinediones and sulfonylureas were associated with weight gain, while DPP-4 inhibitors were associated with weight loss). However, the range of weight changes was very varied and, in practice, there were many patients who lost weight on sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones and gained weight on DPP-4 inhibitors.

A key limitation of this study is that it studies effectiveness only as HbA1c change. While this remains an accepted paradigm in diabetes, it should be acknowledged that data pertaining directly to microvascular outcomes, cardiovascular outcomes and mortality would be of greater value. However, these observational data would not support robust causal inferences about those outcomes.

Concerns regarding confounding and bias in this study are reduced by the fact that findings are qualitatively consistent with published randomized data and by focusing on changes from the baseline within individuals, this reduces the probability of confounding by baseline characteristics. However, as in any observational study, the possibility of confounding cannot be excluded and randomized clinical trials would be needed to definitively address that concern. Crossover to other treatments complicates interpretation of primary analyses, but this concern is alleviated by the consistent results from the on-treatment sensitivity analysis. Although sensitivity analysis incorporating information on starting dose was reassuring, the validity of that analysis may have been limited due to the limited availability of information on daily dose in this database.

Another limitation is that findings must be considered in light of our changing understanding of diabetes drug safety and side effects. DPP-4 inhibitors have the advantage of not causing weight gain, but are under increasing scrutiny for a possible link to pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer [15]. Sulfonylureas cause hypoglycemia and possibly increased mortality. Pioglitazone has established risks of heart failure and fracture and may be linked to bladder cancer [16–20]. However, recent publications have made the argument that the bladder cancer link is unlikely to be borne out by further studies, and that pioglitazone’s other risks are manageable and are potentially outweighed by other benefits from the drug [19]. Recent guidelines draw different conclusions from these risk–benefit profiles [4,21,22]. All drugs studied here continue to be recommended for clinical use.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this observational study yielded results consistent with the available literature from randomized trials [2,3,5–7,9]. It also supported several clinically relevant conclusions that are not clearly evident from the randomized data alone. In combination therapy, sulfonylureas appear to offer acceptable long-term results even though their effectiveness does decline over time. Thiazolidinediones have a pronounced increase in effectiveness in selected patient subgroups, which should influence prescribing decisions. DPP-4 inhibitors may have limited effectiveness compared to alternatives in triple therapy.

Future perspective

Randomized controlled trials are unlikely to ever provide enough information to fully inform decision- making in diabetes treatment. There are too many different drug combinations and specific patient subgroups for a randomized study to be carried out for every treatment decision. While key issues, such as drug safety and the effect of drugs on long-term clinical outcomes, are difficult to assess using observational data, the effect of treatment on a repeated measure, such as HbA1c, is more amenable to observational study. In this specific area of comparative effectiveness, observational studies of drug effects play a significant role in clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics for a second drug added to sulfonylurea monotherapy.

| Variable | Metformin | SD | Thiazolidinedione | SD | SDiff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 3922 | – | 462 | – | – |

| Year | 2006 | 2 | 2005 | 2 | 0.26 |

| Baseline HbA1c (% units) | 8.71 | 1.41 | 9.10 | 1.48 | −0.28 |

| Baseline HbA1c to cohort entry (days) | 21 | 18 | 22 | 20 | −0.09 |

| Age (years) | 67 | 12 | 69 | 11 | −0.16 |

| Female sex (%) | 35 | – | 43 | – | −0.18 |

| Baseline creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.05 | 0.28 | 1.20 | 0.44 | −0.52 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 28.2 | 5.1 | 29.2 | 5.1 | −0.19 |

| Duration of follow-up months) | 46 | 32 | 39 | 30 | 0.19 |

| No new treatment at 1 year (%) | 92 | – | 81 | – | 0.39 |

HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin; SD: Standard deviation; SDiff: Standardized difference compared with metformin added to sulfonylurea monotherapy.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics for a third drug added to metformin/ sulfonylurea dual therapy.

| Variable | Thiazolidinedione | SD | DPP-4 | SD | SDiff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 5853 | – | 1895 | – | – |

| Year | 2007 | 2 | 2010 | 1 | −1.72 |

| Baseline HbA1c (% units) | 8.89 | 1.31 | 8.91 | 1.38 | −0.02 |

| Baseline HbA1c to cohort entry (days) | 22 | 19 | 21 | 19 | 0.03 |

| Age (years) | 63 | 11 | 63 | 11 | 0.00 |

| Female sex (%) | 37 | – | 35 | – | 0.05 |

| Baseline creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.03 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 31.8 | 6.0 | 32.2 | 6.2 | −0.06 |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | 26 | 23 | 15 | 10 | 0.52 |

| No new treatment at 1 year (%) | 86 | – | 85 | – | 0.04 |

DDP-4: Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4; HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin; SD: Standard deviation; SDiff: Standardized difference compared with thiazolidinedione added to metformin/sulfonylurea dual therapy.

Executive summary.

-

▪

Clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of common dual- and triple-therapy diabetes drugs combinations are relatively rare.

-

▪

One meta-analysis that addressed this question suffered from low precision of results, and very limited ability to examine changes in drug effectiveness over time and in subgroups.

-

▪

Glycosylated hemoglobin, as a frequently measured biomarker, can be studied in an observational framework as a repeated measure within individuals.

-

▪

This observational study yielded several findings that generally support the extensive literature on diabetes monotherapy: sulfonylurea effectiveness declines over time; all drugs are associated with more robust effects when starting in patients with higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels; and thiazolidinediones are more effective than other medications in obese patients and in women.

-

▪

The decline in sulfonylurea effectiveness over time is small enough to suggest that sulfonylureas are still effective therapeutic options in the long term.

-

▪

The increased effectiveness of thiazolidinediones in obese patients and in women is great enough to be clinically significant; these baseline characteristics should influence prescribing decisions and be taken into account in future randomized study designs.

-

▪

Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitors may be relatively ineffective when used as a third oral agent.

Acknowledgments

JH Flory and AI Mushlin were supported by a seed funding intramural grant by the Weill-Cornell Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hiatt WR, Kaul S, Smith RJ. The cardiovascular safety of diabetes drugs – insights from the rosiglitazone experience. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369(14):1285–1287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1309610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329(14):977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolen S, Vassy J, Feldman L, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of oral diabetes medications for adults with Type 2 diabetes. Rockville, MD, USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Sweet DE, et al. Oral pharmacologic treatment of Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156(3):218–231. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Bellastella G, Maiorino MI, Giugliano D. Proportion of patients at HbA1c target <7% with eight classes of antidiabetic drugs in Type 2 diabetes: systematic review of 218 randomized controlled trials with 78,945 patients. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012;14(3):228–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355(23):2427–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phung OJ, Scholle JM, Talwar M, Coleman CI. Effect of noninsulin antidiabetic drugs added to metformin therapy on glycemic control, weight gain, and hypoglycemia in Type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2010;303(14):1410–1418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Kahn SE, et al. Rationale and design of the glycemia reduction approaches in diabetes: a comparative effectiveness study (GRADE) Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2254–2261. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones TA, Sautter M, Van Gaal LF, Jones NP. Addition of rosiglitazone to metformin is most effective in obese, insulin-resistant patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2003;5(3):163–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2003.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blak BT, Thompson M, Dattani H, Bourke A. Generalisability of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database: demographics, chronic disease prevalence and mortality rates. Inform. Prim. Care. 2011;19(4):251–255. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v19i4.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall GC, McMahon AD, Dain MP, Home PD. A comparison of duration of first prescribed insulin therapy in uncontrolled Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011;94(3):442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohlfing CL, Wiedmeyer HM, Little RR, England JD, Tennill A, Goldstein DE. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA(1c), analysis of glucose profiles and HbA(1c) in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):275–278. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Type 2 Diabetes: National clinical guideline for management in primary and secondary care (update) London, UK: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat. Med. 2009;28(25):3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey CJ. Interpreting adverse signals in diabetes drug development programs. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2098–2106. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrington WG, Levy JB. Metformin: effective and safe in renal disease? Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2008;40(2):411–417. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cariou B, Charbonnel B, Staels B. Thiazolidinediones and PPARγ agonists: time for a reassessment. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;23(5):205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azoulay L, Yin H, Filion KB, et al. The use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer in people with Type 2 diabetes: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2012;344:e3645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schernthaner G, Currie CJ, Schernthaner GH. Do we still need pioglitazone for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes? A risk-benefit critique in 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl. 2):S155–S161. doi: 10.2337/dcS13-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drucker DJ, Sherman SI, Gorelick FS, Bergenstal RM, Sherwin RS, Buse JB. Incretin-based therapies for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes: evaluation of the risks and benefits. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):428–433. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl. 1):S11–S66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. AACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2013. Endocr. Pract. 2013;19(2):327–336. doi: 10.4158/endp.19.2.a38267720403k242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.