Abstract

Staphylococcus lugdunensis is both a commensal of humans and an opportunistic pathogen. Little is currently known about the molecular mechanisms underpinning the virulence of this bacterium. Here, we demonstrate that in contrast to S. aureus,S. lugdunensis makes neither staphyloferrin A (SA) nor staphyloferrin B (SB) in response to iron deprivation, owing to the absence of the SB gene cluster, and a large deletion in the SA biosynthetic gene cluster. As a result, the species grows poorly in serum-containing media, and this defect was complemented by introduction of the S. aureusSA gene cluster into S. lugdunensis. S. lugdunensis expresses the HtsABC and SirABC transporters for SA and SB, respectively; the latter gene set is found within the isd (heme acquisition) gene cluster. An isd deletion strain was significantly debilitated for iron acquisition from both heme and hemoglobin, and was also incapable of utilizing ferric-SB as an iron source, while an hts mutant could not grow on ferric-SA as an iron source. In iron-restricted coculture experiments, S. aureus significantly enhanced the growth of S. lugdunensis, in a manner dependent on staphyloferrin production by S. aureus, and the expression of the cognate transporters by S. lugdunensis.

Keywords: Heme, hemoglobin, iron acquisition, staphylococci, staphyloferrins.

Introduction

Twenty-five years ago, Staphylococcus lugdunensis was described as a new species of coagulase-negative staphylococcus (CoNS), isolated from a human clinical specimen (Freney et al. 1988). It is now widely considered to be an emerging pathogen with uncharacteristically elevated virulence in comparison with other members of the CoNS (Rosenstein and Götz 2013). In addition to being a skin commensal, S. lugdunensis is responsible for both nosocomial and community-acquired infections that may include skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), pneumonia, meningitis, and endocarditis (Sotutu et al. 2002; Anguera et al. 2005; Arias et al. 2010; Kleiner et al. 2010). While the most common clinical manifestation of S. lugdunensis infection is SSTIs (55.4%), blood infections and those associated with vascular catheterization accounted for a notable 17.4% of diagnoses (Herchline and Ayers 1991). Strikingly, the mortality rate of S. lugdunensis-associated endocarditis may reach up to 50% (Anguera et al. 2005). Despite that S. lugdunensis is gaining notoriety as an atypically virulent CoNS, the true burden of S. lugdunensis infection is likely underestimated. Most S. lugdunensis isolates are hemolytic, and although do not secrete soluble coagulase, do produce a membrane-bound clumping factor (coagulant), therefore, it is possible that many S. lugdunensis infections are misinterpreted as being caused by S. aureus (Frank et al. 2008; Böcher et al. 2009; Szabados et al. 2011). Moreover, nearly half of patients infected with S. lugdunensis appear to have no comorbidities, indicating that this underappreciated pathogen is able to cause infection in the absence of overt susceptibility (Kleiner et al. 2010).

Iron is an essential nutrient for most pathogenic bacteria, including the Staphylococci, and represents a significant growth-limiting nutrient in the host (Ratledge and Dover 2000). Virtually all host iron is bound to glycoproteins such as transferrin, ferritin, and lactoferrin (Gomme et al. 2005), or is in complex with heme in hemoproteins. Hemoglobin iron accounts for up to 75% of total host iron, the vast majority of which is found within circulating erythrocytes (Pishchany and Skaar 2012). To establish infection, pathogens must circumvent host iron sequestration strategies, and therefore, by extension, must possess elaborate iron acquisition mechanisms in order to obtain this limited nutrient. Frequently, these iron uptake strategies involve either the acquisition of heme contained in hemoglobin, or the removal of transferrin-bound iron through the secretion of siderophores (Hood and Skaar 2012). Siderophores are small molecules (commonly less than 1000 Da) capable of binding ferric iron with high affinity, and delivering iron back to the cell via surface localized and membrane-embedded receptor proteins.

Much of our molecular understanding of iron acquisition processes in the staphylococci comes from studies in S. aureus. The iron-regulated surface determinants (Isds) were first discovered in S. aureus (Mazmanian et al. 2002; Mazmanian et al. 2003). The Isd system is now fairly well-characterized, and is constituted by a series of proteins that, together, are capable of extracting heme from hemoglobin at the bacterial cell surface, and relaying heme across the cell wall, through the cytoplasmic membrane, and into the cytoplasm where it is degraded to release iron for use in cellular processes (Skaar and Schneewind 2004; Grigg et al. 2010ac2010c). S. aureus also produces two siderophores, staphyloferrin A (SA) and staphyloferrin B (SB), which are synthesized by gene products encoded from within the sfa and sbn genetic loci, respectively (Beasley and Heinrichs 2010; Hammer and Skaar 2011). S. aureus internalizes ferric-SA and ferric-SB using the ABC-type transporters HtsABC and SirABC, respectively, encoded by genes found adjacent to the cognate biosynthetic loci (Beasley and Heinrichs 2010; Grigg et al. 2010a,b; Beasley et al. 2011a). S. aureus strains mutated for staphyloferrin production are severely restricted for growth in the presence of transferrin or animal serum (Beasley et al. 2009, 2011a,b).

Investigations of the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the virulence of S. lugdunensis are in their infancy. Few mutants have, as of yet, been constructed and characterized, and even fewer tested in animal models. In one recent study, it was demonstrated that in S. lugdunensis, sortase A, responsible for the anchoring of LPXTG-containing proteins to the cell wall, was required for full virulence in a rat endocarditis model (Heilbronner et al. 2013). Interestingly, the genome sequencing of two strains of S. lugdunensis, HKU09-01 and N920143, revealed that this species is unique among the CoNS in that it encodes an Isd system (Tse et al. 2010; Haley et al. 2011; Heilbronner et al. 2011; Zapotoczna et al. 2012) and, moreover, in strain HKU09-01, the isd locus is tandemly duplicated. Work led by T. Foster's group has revealed that the isd system in strain N920143 is functional, contributing to the strain's use of hemoglobin as an iron source (Zapotoczna et al. 2012).

In this study, we investigate iron uptake mechanisms in S. lugdunensis through characterizing the role of the S. lugdunensis strain HKU09-01 isd locus in heme and hemoglobin utilization, as well as characterizing this species for the ability to produce and utilize staphyloferrins. We demonstrate that a mutant lacking isd is severely impaired for growth using heme and hemoglobin as a sole iron source, especially at nanomolar heme and hemoglobin concentrations. Moreover, we show that S. lugdunensis grows poorly in serum and in the presence of transferrin owing to a lack of detectable siderophore production. We further demonstrate that while S. lugdunensis cannot produce staphyloferrins, it encodes the transporters for their uptake and these transporters are functional, leading to the notion that S. lugdunensis may appropriate staphyloferrins from other staphylococcal species to augment its growth. In support of this, we show that growth of iron-restricted S. lugdunensis is significantly enhanced in coculture with staphyloferrin-producing S. aureus, in an hts- and sir-dependent manner.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1. For all routine manipulations, Escherichia coli DH5α was grown in Difco Luria–Bertani broth (LB; BD-Canada, Mississauga, ON, Canada) or on LB agar (LBA). S. lugdunensis and S. aureus strains were cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB; BD Diagnostics) or on TSB agar (TSA). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 100 μg/mL ampicillin for E. coli selection; 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol for S. lugdunensis selection. For subsequent experiments, S. lugdunensis and S. aureus were grown in several different iron-restricted media as detailed: (i) Tris-minimal succinate broth (TMS) (Sebulsky et al. 2004); (ii) TMS treated with Chelex-100 resin (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada) for 24 h at 4°C (C-TMS); (iii) an 80:20 mixture of C-TMS to complement-inactivated horse serum (Sigma Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada); or (iv) RPMI media 1640 (Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada) reconstituted from powder and supplemented with 1% w/v casamino acids (RPMIC) and 1 μmol/L of the iron chelator ethylenediamine-di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid) (EDDHA; LGC Standards GmbH, Teddington, Middlesex, U.K.). All bacteria were cultured at 37°C, shaking at 200 rpm, unless otherwise indicated. All media and solutions were prepared with water purified through a Milli-Q water purification system (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Bacterial strain, plasmid or oligonucleotide | Description1 | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α |

φf80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrAB thi-1 hsdR17(

) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 ) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169

|

Promega |

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis | ||

| HKU09-01 | Human skin infection isolate | Tse et al. (2010) |

| H2710 | HKU09-01 Δisd-sir | This study |

| H2773 | HKU09-01 ΔhtsABC | This study |

| H2774 | HKU09-01 Δisd-sir ΔhtsABC | This study |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| RN4220 | Prophage-cured laboratory strain;

; accepts foreign DNA ; accepts foreign DNA |

Kreiswirth et al. (1983) |

| RN6390 | Prophage-cured laboratory strain | Peng et al. (1988) |

| H1324 | RN6390 Δsbn::Tet; TetR | Beasley et al. (2009) |

| H1661 | RN6390 Δsfa::Km; KmR | Beasley et al. (2009) |

| H1649 | RN6390 Δsbn::Tet Δsfa::Km; TetR KmR | Beasley et al. (2009) |

| H306 | RN6390 ΔsirA::Km; KmR | Beasley et al. (2009) |

| H1448 | RN6390 Δhts::Tet; TetR | Beasley et al. (2009) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKOR1 | E. coli/Staphylococcus shuttle vector allowing allelic replacement in staphylococci | Bae and Schneewind (2006) |

| pKOR1Δisd-sir | pKOR1 plasmid for deletion of duplicated genetic region encompassing isd and sir | This study |

| pKOR1Δhts | pKOR1 plasmid for in-frame deletion of htsABC | This study |

| pRMC2 | E. coli/Staphylococcus shuttle vector: ApR CmR | Corrigan and Foster (2009) |

| pRMC2::sir | pRMC2 derivative for sirABC expression; CmR | This study |

| pRMC2::hts | pRMC2 derivative for htsABC expression; CmR | This study |

| pLI50 | E. coli/Staphylococcus shuttle vector: ApR CmR | Lee and Iandolo (1986) |

| pLI50::sfaABCD (pEV90) | pLI50 derivative containing sfaABCD from S. aureus; CmR | Beasley et al. (2009) |

| Oligonucleotides2,3 purpose | Sequence (5′–3′) |

| Primers for generating upstream and downstream recombinant regions for Δisd Δsir using pKOR1 | (AttB1)-isdUF:GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCT CTACCACTGACAGCAACGGCAAT |

| isdUR: CTCATTGCGATTCCTTCCTTCG | |

| isdDF: Phos/AGCACAGATAGGAGTTCATTTGCATGTA | |

| isdDF: Phos/AGCACAGATAGGAGTTCATTTGCATGTA | |

| (AttB2)-isdDR:GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGT AGATGCGCCTTGGATTTGACAC | |

| Primers for generating upstream and downstream recombinant regions for Δhts using pKOR1 | (AttB1)-htsUF:GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCT ATTCCAGTATGTTGCCAC |

| htsUR: AACAGTAGCCCAATGATAC | |

| htsDF: Phos/AGTAGGTGTCATAATAGC | |

| (AttB2)-htsDR:GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGT TACTGGTAATGAGCACTC | |

| Primers for cloning sirABC into pRMC2 for complementation | XhoI-sirF: GATCCTCGAGTACTGCTCCAAAATCCCC |

| EcoRI-sirR: GATCGAATTCTTTAGCGTGCGGTATGTC | |

| Primers for cloning htsABC into pRMC2 for complementation | KpnI-htsF: GATCGGTACCAAGCACTAACCCAGTCAATG |

| SacI-htsR: GATCGAGCTCCTAAACAATCCCCATAAAGC |

ApR, CmR, KmR, and TetR: resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, and tetracycline, respectively.

Restriction sites for cloning are underlined.

Phos/denotes a 5′ phosphate on the primer.

Generation of Δisd-sir and ΔhtsABC mutants in S. lugdunensis

Primer sequences used for the construction and complementation of S. lugdunensis mutants can be found in Table 1. Allelic replacement was performed as previously described, using the plasmid pKOR1 (Bae and Schneewind 2006). In brief, 500–1000-bp DNA fragments were amplified from the genomic regions upstream and downstream of the tandem-duplicated isd-sir locus (Fig. 1B) using the primers isdUF and isdUR, and isdDF and isdDR, respectively. The amplicons were cloned into pKOR1, generating pKOR1Δisd-sir. Similarly, the plasmid pKOR1Δhts for the in-frame deletion of htsABC (Fig. 1A) was constructed by amplifying 500–1000-bp DNA fragments flanking the start and stop codons of the operon using primers htsUF and htsUR, and htsDF and htsDR. The vectors were passaged through S. aureus RN4220 (a restriction-negative, modification-positive strain) before introduction into S. lugdunensis HKU09-01 by electroporation (Monk et al. 2012). The strains HKU09-01 Δisd-sir (H2710) and HKU09-01 ΔhtsABC (H2773) were generated using the methodology for pKOR1 (Bae and Schneewind 2006; Zapotoczna et al. 2012), and introduction and recombination of pKOR1Δhts with H2710 was used to produce the isd, sir, hts-deficient strain H2774. Chromosomal deletions were confirmed through sequencing of PCR amplicons generated from across the deleted regions.

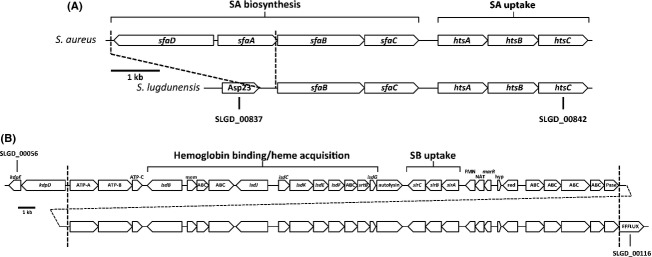

Figure 1.

Physical maps of the sfa-hts and isd loci in Staphylococcus lugdunensis. (A) Staphyloferrin A (SA) biosynthetic and uptake locus. Shown is the homologous locus in S. aureus versus that which is present in all sequenced genomes of S. lugdunensis. Note that the SA biosynthetic locus in S. lugdunensis carries a deletion that eliminates two genes completely (sfaA and sfaD), along with the promoter for the remaining two genes (sfaB and sfaC). The deleted region is indicated between the dashed lines. Asp23, alkaline shock protein 23. (B) Shown is the ∼65-kb region of the S. lugdunensis strain HKU09-01 genome (spanning orfs SLGD_00056 to SLGD_00116) with the tandemly duplicated isd-sir locus. The duplicated region is shown between the dashed vertical lines. Abbreviations are as follows, with predicted or hypothetical functions: ABC, component of an ATP-binding cassette transporter; ATP-A,B,C, K+-ATPase components A, B, and C, respectively; mem, membrane protein; FMN, FMN binding protein; NAT,N-acetyltransferase; marR, MarR-type regulator; hyp, hypothetical; Red, reductase; Pase, phosphatase.

Complementation of sirABC and htsABC mutations

For complementation of the S. lugdunensis sirABC deletion, primers XhoI-SirF and EcoRI-SirR were used to amplify the wild-type sirABC operon, including its native promoter. The fragment was cloned into pRMC2 generating pRMC2::sir. The htsABC complementation vector pRMC2::hts was similarly created using the amplicon generated with oligonucleotides KpnI-HtsF and SacI-HtsR, again including the native promoter for htsABC.

Bacterial growth curves

Single, isolated S. aureus and S. lugdunensis colonies, taken from TSA plates after overnight incubation, were resuspended in 120 μL C-TMS and 100 μL of this suspension was used to inoculate 2 mL C-TMS. These cultures were then incubated at 37°C for at least 4 h until OD600 was ∼1. The cultures were subsequently normalized to an OD600 of 1 and 1 μL was added to 200 μL aliquots of 80:20 C-TMS:horse serum growth media. For iron-replete conditions, 100 μM FeCl3 was included. Chloramphenicol was added for strains harboring pLI50, pRMC2 or their derivatives. Cultures were grown with constant shaking at medium amplitude in a Bioscreen C machine (Growth Curves USA, Piscataway, NJ) at 37°C. OD600 was measured every 15 min, however, for graphical clarity, measurements at 4-h intervals are shown.

Siderophore preparations and plate bioassays

SA and SB were synthesized enzymatically as previously described (Cheung et al. 2009; Grigg et al. 2010b). Alternatively, concentrated culture supernatants enriched for SA and SB were prepared from S. aureus Δsbn and Δsfa mutants, respectively, as previously described (Beasley et al. 2009). Concentrated culture supernatants from S. lugdunensis were similarly prepared. In brief, strains were grown in C-TMS with aeration, for 40 h. Bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation and supernatants were lyophilized overnight and resuspended in methanol (one-fifth the original culture volume). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and the soluble fraction was rotary evaporated. Dried material was resuspended in water (one-tenth the original culture volume). The ability of concentrated culture supernatants to support staphylococcal growth was assessed using the plate bioassay technique as previously described (Sebulsky et al. 2000). To assess growth promotion on S. lugdunensis cells, 1 × 104 cells/mL were incorporated into TMS-agar containing 5 μmol/L EDDHA. Chloramphenicol was incorporated into media with strains harboring pRMC2, pLI50, or vector derivatives. SA and SB were also synthesized enzymatically, using procedures that have been previously described (Cheung et al. 2009; Grigg et al. 2010b). Siderophores/supernatants were applied to sterile paper disks and placed onto the plates. Growth around disks was measured after 24 h.

Chrome azurol S assay

Supernatants of iron-starved staphylococci were concentrated by lyophilization to 1/10 of their original volume and tested for iron-binding compounds using the chrome azurol S shuttle solution (Schwyn and Neilands 1987), as previously described (Cheung et al. 2009).

Analysis of iron-regulated protein expression by Western blotting

Antisera against S. aureus HtsA and SirA used in this study were generated previously (Dale 2004; Beasley et al. 2009). The antisera were used to assess the expression of homologous proteins in S. lugdunensis, as described below.

For analysis of iron-regulated protein expression in whole-cell lysates, cells were grown in C-TMS with or without 50 μmol/L FeCl3 for 24 h, normalized to an OD600 of 1, and lysed. Proteins in lysates were resolved through SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a 12% acrylamide resolving gel. For Western immunoblots, proteins were transferred from gels to a 45-μm nitrocellulose membrane via standard protocols (Sambrook et al. 1989). Detection of transferred proteins was performed after blocking the membrane at 4°C for 12 h in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% w/v skim milk and 20% v/v horse serum. The membrane was washed and the primary antibody was applied at room temperature for 2 h (1:3000 dilution) in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, and 5% horse serum. The membrane was washed again, and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to IRDye 800 (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was used as the secondary antibody, applied at room temperature for 1 h (1:20,000 dilution), in the same buffer as the primary antibody. Fluorescence was analyzed on a Li-Cor Odyssey infrared imager (Li-Cor Biosciences).

Staphylococcal growth in coculture

Staphylococci were grown for 4 h in C-TMS. Cells were washed three times in C-TMS and normalized to an OD600 of 1 (S. lugdunensis) or 0.1 (S. aureus). Staphylococci were inoculated into 2 mL of media (80:20 C-TMS:horse serum) either in monoculture or in coculture. For cocultures, equal volumes of washed cells from each species were added. The 2-mL cultures were in 14-mL round-bottom polypropylene tubes and shaken at 200 rpm. Samples were taken at time 0, 12, and 24 h for dilution and plating on TSA to obtain values for viable colony-forming units (CFUs). TSA plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and subsequently at room temperature for 2 days. Staphylococci were distinguished based on colony color and morphology; S. aureus colonies were visibly larger in diameter and with lighter pigmentation, whereas S. lugdunensis colonies were distinguishably smaller (∼¼–½ the diameter of S. aureus colonies) and dark yellow under these culture conditions.

Preparation of hemin and hemoglobin

A solution of bovine hemin (Sigma Aldrich) was prepared as follows. A stock solution at 5 mmol/L in 0.1 N NaOH is prepared and vigorous vortexing ensures the hemin is solubilized completely. The solution is filtered through 0.2 micron filter. The final concentration of hemin, postfiltration, was determined by making dilutions in 0.1 N NaOH and measuring the UV–Vis spectra, using the molar extinction coefficient for hemin in 0.1 N NaOH of 58,400 cm−1 (mol/L)−1 at 385 nm. Hemin stocks were stored at −20°C. For use in growth assays, hemin stocks are diluted in growth media immediately prior to use.

For hemoglobin purification, 25 mL of fresh, heparinized human blood was centrifuged at 1500g at 4°C for 10 min to pellet the erythrocytes. Erythrocytes were washed three times in three pellet volumes of ice-cold sterile saline and subsequently lysed through resuspension in two pellet volumes of 50 mmol/L Tris pH 8.6, 2 mmol/L EDTA. Erythrocyte lysis was allowed to proceed for 30 min at room temperature, mixing periodically by gentle inversion. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 11000g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and solid NaCl was added (50 mg/mL), with mixing by inversion. The stroma was then precipitated by centrifugation at 11000g for 30 min at 4°C. The hemoglobin-containing supernatant was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 50 mmol/L Tris pH 8.6, 1 mmol/L EDTA (Buffer A). The dialyzed hemoglobin was passed once through a 0.4 μm syringe filter prior to purification via anion exchange on a Mono Q HR 16/10 column (GE Healthcare, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Dialyzed hemoglobin solution was loaded in 4–6 mL batches on the column and a gradient run using 50 mmol/L Tris pH 8.6, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mol/L NaCl as Buffer B; hemoglobin fraction eluted between 50 and 100 mmol/L NaCl. The purified fractions were dialyzed into 50 mmol/L Tris pH 8.0 and sterilized by passage through a 0.4 μm syringe filter. Purity was assessed using UV–Vis spectrometry. Briefly, a spectral scan was run between 200 and 800 nm, where a characteristic Soret peak at 415 nm, as well as distinct α576 nm and β541 nm bands, and a peak at 345 nm, were indicative of intact ferrous oxyhemoglobin. Hemoglobin concentration was determined using published extinction coefficients at 560 and 577 nm (Winterbourn et al. 1976) and was concentrated to 2 mmol/L using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugation units (30 kDa NMWL; Millipore). Small aliquots were flash frozen in a dry ice–ethanol bath and stored at −80°C.

Assessment of hemin and hemoglobin utilization by S. lugdunensis

In assessing hemin/hemoglobin utilization, single, isolated colonies of S. lugdunensis from overnight TSA plates were resuspended in 120 μL RPMIC. 100 μL of this suspension was used to inoculate 2 mL RPMIC with 0.1 μmol/L EDDHA, which was grown for at least 4 h until OD600 was ∼1. Precultures were subcultured 1:400 into 2 mL aliquots of RPMIC with 1 μmol/L EDDHA and either 1–500 nmol/L human hemoglobin, purified as described above, 20–1000 nmol/L hemin, prepared as described above, or 1 μmol/L FeSO4. Cultures were incubated with shaking at 200 rpm, in 14-mL round-bottom polypropylene tubes. OD600 was assessed at 12, 24, and 36 h.

Results

Sequence analysis of key iron acquisition loci in S. lugdunensis

S. aureus contains several key iron acquisition loci that are well-characterized. These include the isd locus that promotes iron acquisition from heme and hemoglobin, the sfa-hts locus for synthesis and reentry of SA and the sbn-sir locus for synthesis and uptake of SB (Beasley and Heinrichs 2010; Hammer and Skaar 2011). The genome sequences of S. lugdunensis strains N920143 and HKU01-09 indicate that these strains possess htsABC genes downstream from an sfa locus (Fig. 1A), with predicted products that are highly similar to the S. aureus HtsABC proteins (Table 2). However, in contrast to S. aureus, the S. lugdunensis sfa locus in both strains contains a deletion of ∼3.3 kb that eliminates the sfaA and sfaD genes, as well as the promoter for the remaining sfaBC genes (Fig. 1A). This suggests that S. lugdunensis does not synthesize SA, yet may be able to utilize it as an iron source, via HtsABC, if SA were provided exogenously. In contrast to S. aureus,S. lugdunensis lacks the sbn operon, which encodes the products responsible for synthesizing SB. Interestingly, S. lugdunensis possesses homologs of the S. aureus sirABC genes (predicted products are highly similar to those from S. aureus, see Table 2), which encode a SB transporter, and these genes are situated immediately downstream of the S. lugdunensis isd locus (Fig. 1B). In comparison to S. lugdunensis N920143, strain HKU01-09 contains an exact, tandem duplication of a large region of DNA encompassing the isd-sir locus (Fig. 1B). Together, the sequence analysis of these loci suggests that S. lugdunensis should not be able to synthesize either SA or SB, in contrast to S. aureus, which synthesizes and secretes both staphyloferrin molecules. On the other hand, we would predict that S. lugdunensis should be able to transport iron via these siderophores, as well as acquire iron from heme/hemoglobin via Isd proteins.

Table 2.

Similarity of iron-regulated proteins between Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

| Protein | Function | % ID/% TS |

|---|---|---|

| HtsA | Lipoprotein; receptor for ferric-staphyloferrin A (Fe-SA) | 70/82 |

| HtsB | Permease; specific for Fe-SA | 60/74 |

| HtsC | Permease; specific for Fe-SA | 71/87 |

| SfaB | Synthetase; completes SA synthesis by addition of citric acid to alpha amine of d-ornithine in citryl-d-ornithine intermediate | 43/68 |

| SfaC | Amino acid racemase; predicted to convert l-ornithine to d-ornithine | 57/79 |

| SirA | Lipoprotein; receptor for ferric-staphyloferrin B (Fe-SB) | 85/92 |

| SirB | Permease; specific for Fe-SB | 84/94 |

| SirC | Permease; specific for Fe-SB | 74/84 |

| IsdC | Wall anchored heme-binding protein | 57/67 |

| IsdE | Lipoprotein; receptor for heme | 75/85 |

| IsdB | Wall-anchored hemoglobin-binding protein | 35/52 |

| IsdA (Sa) vs. IsdJ (Sl) | Wall-anchored heme-binding protein | 19/29 |

| IsdA (Sa) vs. IsdK (Sl) | Wall-anchored heme-binding protein | 14/31 |

ID, identity; TS, total similarity; Sa, S. aureus; Sl, S. lugdunensis.

S. lugdunensis grows poorly in iron-restricted media, owing to a lack of siderophore production

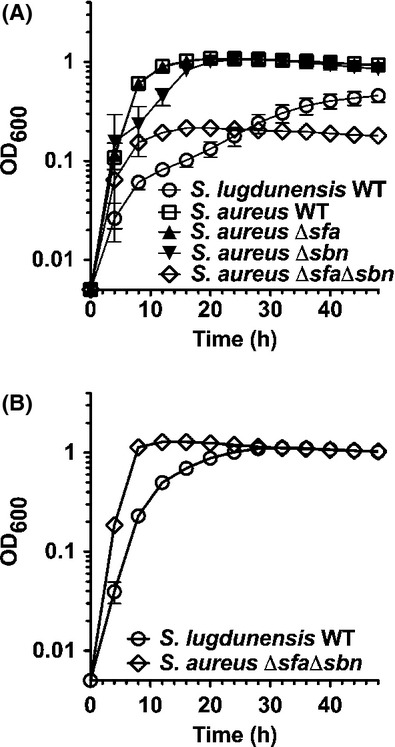

Our previous studies showed that in comparison to wild-type S. aureus, mutants lacking the ability to synthesize the two staphyloferrin siderophores (i.e., sfa sbn) grow poorly in iron-restricted media containing transferrin or serum (as a source of transferrin) (Beasley et al. 2009, 2011b). Given that S. lugdunensis genomic information suggests an inability to produce a staphyloferrin siderophore, we compared the growth of S. lugdunensis to that of S. aureus and its staphyloferrin-deficient mutants in iron-restricted media. In comparison to wild-type S. aureus,S. lugdunensis grew poorly in C-TMS with 20% serum (Fig. 2A) or transferrin (data not shown) and, even after extended incubation periods, never reached a final biomass equivalent to that of S. aureus. Indeed, in these culture conditions, S. lugdunensis HKU01-09 (strain HKU01-09 was used throughout this study) grew at a slower rate than the S. aureus sfa sbn mutant. We demonstrated that the growth deficiency of S. lugdunensis and S. aureus sfa sbn was due to a deficiency in the ability to scavenge trace amounts of iron, as supplementation of the growth medium with 100 μmol/L FeCl3 promoted rapid growth of both (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Staphylococcus lugdunensis grows poorly in iron-restricted growth media. (A) Growth kinetics comparing S. lugdunensis to that of Staphylococcus aureusWT and staphyloferrin A (sfa) and staphyloferrin B (sbn)-deficient mutants in C-TMS with 20% serum. (B) The growth deficiencies of S. lugdunensis and the S. aureus staphyloferrin-deficient mutant in iron-restricted media are complemented with addition of 100 μmol/L FeCl3. All data points represent average values for at least three independent biological replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean.

In further support of the bioinformatics analyses indicating that S. lugdunensis is incapable of staphyloferrin production, the culture supernatants of S. lugdunensis, grown in C-TMS, tested negative in the chrome azurol S assay (Fig. 3A), indicating a lack of secreted iron-binding molecules. This is in contrast to the positive result obtained for S. aureus culture supernatants grown in the same medium and under the same conditions.

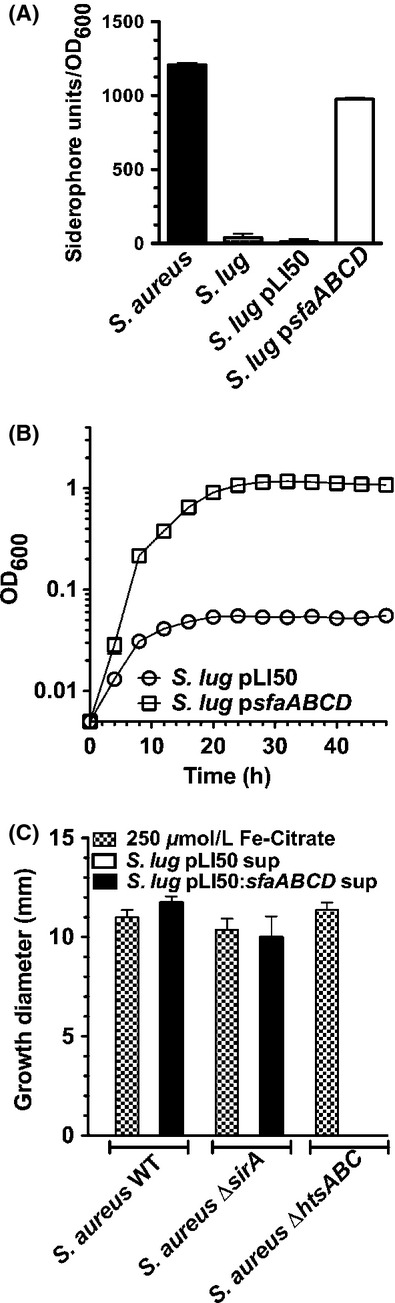

Figure 3.

Introduction of a complete sfa locus from Staphylococcus aureus into Staphylococcus lugdunensis leads to SA production and growth in iron-restricted media. (A) Chrome azurol S (CAS) assay demonstrates that culture supernatants of S. lugdunensis lack siderophore activity, whereas introduction of the plasmid carrying the S. aureus sfaA-D genes into S. lugdunensis allows for the production and secretion of siderophore into culture supernatants. (B) Growth of S. lugdunensisWT strain containing either vehicle (pLI50) or plasmid carrying the staphyloferrin A biosynthetic genes (sfaA-D) in C-TMS plus 20% serum. (C) Agar plate bioassays demonstrating that the culture supernatant of S. lugdunensis does not promote the growth of iron-restricted S. aureus strains, while the supernatant of S. lugdunensis carrying the sfa gene cluster, which generates SA, can promote the growth of iron-restricted S. aureus in an hts (encodes the SA transporter)-dependent manner. Ferric citrate was used as a positive control in the experiment. All data points represent average values for at least three independent biological replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean.

Cotton et al. (2009) have previously demonstrated that the cloned sfa gene cluster allowed heterologous synthesis and secretion of SA in E. coli. Knowing this, we used our plasmid containing the sfaA-D genes, which was previously used to complement the sfa deletion in S. aureus (Beasley et al. 2009), and introduced it into S. lugdunensis. The chrome azurol S assay was used to demonstrate that when we grew the recombinant S. lugdunensis strain in iron-restricted media, we could detect robust siderophore activity compared to wild-type or the strain carrying the vector control (Fig. 3A).

Despite not synthesizing SA, S. lugdunensis has htsABC homologs that, in S. aureus, are required for utilization of ferric-SA complexes. To test the possibility that S. lugdunensis can utilize SA, we demonstrated that the sfa-complemented strain displayed enhanced growth in C-TMS media containing 20% serum, as compared to wild-type S. lugdunensis carrying the empty control plasmid (Fig. 3B). In support of the result that we could not detect iron-binding molecules in the iron-restricted culture supernatant of S. lugdunensis, we demonstrated that concentrated culture supernatants of S. lugdunensis were incapable of enhancing iron-restricted growth of S. aureus (Fig. 3C). Importantly, concentrated culture supernatant from S. lugdunensis containing the S. aureus sfa gene cluster could readily promote growth of wild-type and sirA-deficient S. aureus, but not an htsABC-mutant S. aureus strain. This is in agreement with the notion that S. lugdunensis expressing the S. aureus sfa genes was making SA and using it to promote enhanced growth in iron-restricted media.

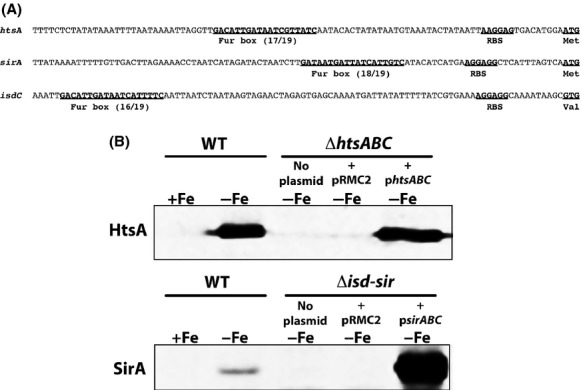

S. lugdunensis HtsABC and SirABC function as transporters for SA and SB, respectively

Promoters containing putative Fur box sequences are found upstream of the htsABC and sirABC operons in S. lugdunensis (Fig. 4A), suggesting that each operon is iron-regulated in a Fur-dependent fashion. Due to high amino acid sequence similarity of the S. lugdunensis HtsA and SirA with the S. aureus homologs (see Table 2), antibodies raised against S. aureus HtsA and SirA were used to successfully demonstrate iron-regulated expression of the S. lugdunensis proteins (Fig. 4B). We next deleted the htsABC genes from the S. lugdunensis genome and complemented the genes in trans by cloning the htsABC genes from S. lugdunensis back into the mutant strain. As shown in Fig. 4B, the ΔhtsABC strain failed to express HtsA while the complemented strain showed restored expression of HtsA.

Figure 4.

Expression of Staphylococcus lugdunensis HtsA and SirA homologues is iron-regulated. (A) Identification of Fur-boxes upstream of the htsA,sirA and isdC genes in S. lugdunensis. Numbers represent the number of identical bases between the 19-bp Fur boxes of S. aureus and S. lugdunensis. (B) Western blots demonstrating iron-regulated expression of HtsA and SirA, and confirmation of mutations and complementation, where pRMC2 is the vehicle control. Cultures were grown in C-TMS with (+Fe) or without (−Fe) addition of FeCl3 (25 μmol/L). Mutant samples were all grown in C-TMS without addition of iron.

To generate a S. lugdunensis mutant lacking both copies of sirABC, we deleted the entire tandemly duplicated region (Fig. 1B) from the genome, a deletion of ∼65 kb; we refer to this mutant strain as Δisd-sir. As expected, the mutant failed to express SirA (Fig. 4B). Complementation of the Δisd-sir strain with the sirABC genes from S. lugdunensis restored expression of SirA (Fig. 4B).

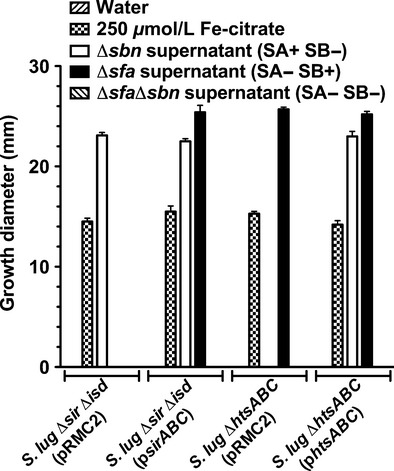

With mutant and complemented strains in hand, we used them to test the ability of the strains to utilize the two staphyloferrin siderophores produced by S. aureus. As shown in Fig. 5, the ability of S. lugdunensis strains to utilize SA and SB, whether provided in concentrated culture supernatants from S. aureus strains, or as enzymatically synthesized and HPLC-purified molecules (data not shown), was absolutely dependent on the expression of htsABC and sirABC, respectively. Moreover, while the growth of S. lugdunensis was enhanced when the intact S. aureus sfa gene locus was introduced on a plasmid (Fig. 3B), the same plasmid was incapable of complementing the iron-restricted growth defect of the S. lugdunensis ΔhtsABC mutant (data not shown). Together, these data prove that both the HtsABC and the SirABC transporters are functional in S. lugdunensis.

Figure 5.

Plate bioassays demonstrate that Staphylococcus lugdunensis HtsABC and SirABC are required for uptake of staphyloferrin A and staphyloferrin B, respectively. Water and ferric citrate were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Supernatant extracts supplied were those of Staphylococcus aureus mutants that secrete SA (sbn mutant), SB (sfa mutant) or neither SA or SB (sfa sbn mutant). All data points represent average values for at least three independent biological replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean.

S. aureus enhances S. lugdunensis growth in a staphyloferrin-dependent manner

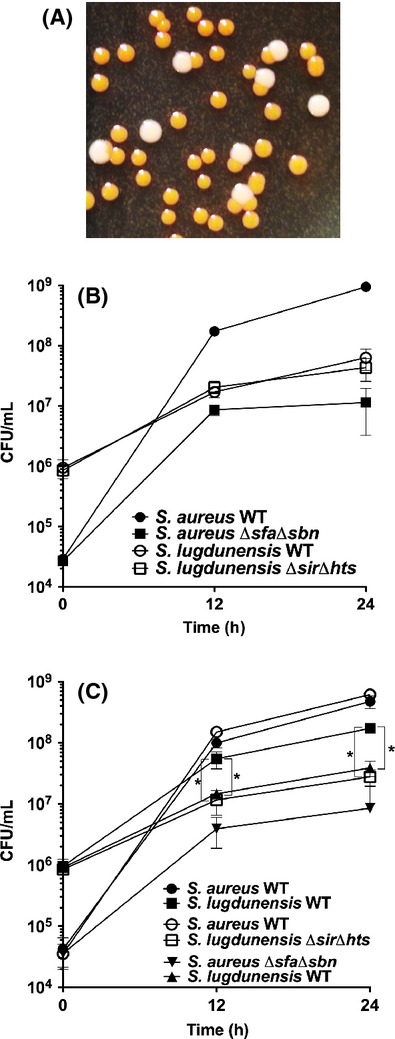

As shown above, we demonstrated that exogenously added staphyloferrins could promote the growth of S. lugdunensis. Knowing this, we next decided to test whether S. aureus, which secretes both SA and SB, could augment the growth of S. lugdunensis if they were cultured together in iron-restricted growth media. We first optimized culture conditions so as to be able to easily discern colonies of S. aureus RN6390 from those of S. lugdunensis HKU09-01 on TSA (Fig. 6A) (see Experimental Procedures for details).

Figure 6.

Coculture experiments demonstrate that Staphylococcus aureus-produced siderophores can enhance the iron-restricted growth of Staphylococcus lugdunensis. (A) Picture of colonies of S. aureus RN6390 (large and white) and S. lugdunensis (smaller and yellow) growing on a TSB plate after 24 h of incubation at 37°C, followed by 48 h of incubation at room temperature. (B) Growth of individual strains in C-TMS + 20% serum was monitored for CFU/mL at 12 and 24 h timepoints. (C) Growth of strains in cocultures with the pairs of strains grouped as indicated. All data points represent average values for at least three independent biological replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. The Student's unpaired t-test was used to define statistical significance for the CFU values between strains as indicated by the brackets. *P < 0.0001.

Figure 6B demonstrates that, when cultured in C-TMS containing 20% serum, wild-type S. aureus consistently grows from 2 × 104 CFU/mL to ∼1 × 109 CFU/mL within 24 h, whereas the isogenic staphyloferrin-deficient mutant grows to a density of only 1 × 107 CFU/mL over the same time frame. S. lugdunensis, on the other hand, inoculated at a higher cell density of 1 × 106 CFU/mL, only reaches a final cell density of less than 1 × 108 CFU/mL in 24 h. The isogenic S. lugdunensis isd-sir hts mutant displays identical growth kinetics in these culture conditions.

For coculture experiments, in pilot studies, we found that we needed to inoculate S. lugdunensis at much higher cell densities than S. aureus because S. aureus grows significantly faster than S. lugdunensis in these culture conditions. Data displayed in Figure 6C demonstrate that when wild-type S. aureus is cocultured with wild-type S. lugdunensis,S. lugdunensis grew to much higher density, ∼2 × 108, than when cultured on its own (c.f. Fig. 6B vs. Fig. 6C). We next demonstrated that this growth enhancement was due to the use of the S. aureus-produced staphyloferrins by S. lugdunensis by use of two complementary experiments (Fig. 6C). First, wild-type S. aureus did not enhance the growth of the S. lugdunensis Δisd-sir ΔhtsABC mutant like it did wild-type S. lugdunensis. Second, staphyloferrin-deficient S. aureus had no effect on the growth of wild-type S. lugdunensis. Together, these data provide convincing evidence that S. aureus, through production of SA and SB, enhances the iron-restricted growth of S. lugdunensis in a HtsABC-and SirABC-dependent manner, respectively.

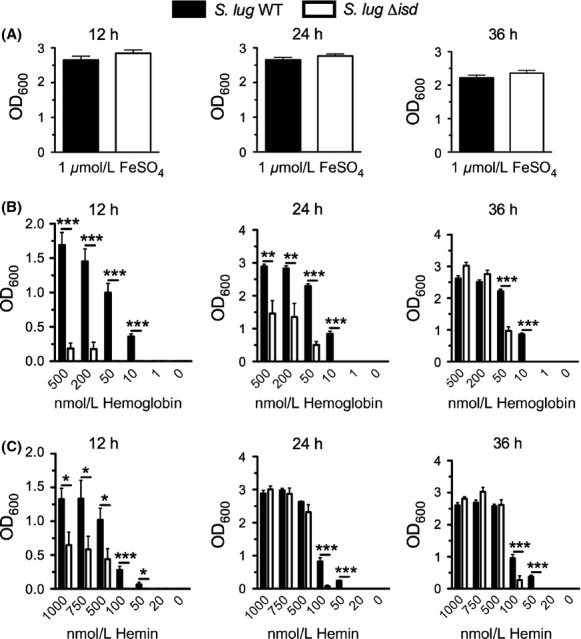

The S. lugdunensis isd-sir mutant is attenuated for utilization of heme and hemoglobin

Having constructed a complete isd locus deletion strain of S. lugdunensis HKU01-09, we were therefore positioned to test the mutant for its ability to utilize heme and hemoglobin as sole sources of iron. Zapotoczna et al. (2012) have also recently generated isdB and isd locus deletion mutants in S. lugdunensis strain N920143 and shown that the mutants were impaired for growth on hemoglobin compared to wild type. These experiments were performed using a single concentration of hemoglobin, and heme as a sole iron source was not tested. We took a more comprehensive approach by examining the growth of the Δisd-sir deletion mutant in iron-starved media containing a range of heme and hemoglobin concentrations, in media that contained enough of the nonmetabolizable iron chelator EDDHA to completely restrict growth unless an iron source was added. As shown in Figure 7A, the Δisd-sir mutant is not debilitated for use of FeSO4 as an iron source. In Figure 7B, it is notable that the Δisd-sir mutant is attenuated for growth at all concentrations of hemoglobin tested (500 nmol/L down to 10 nmol/L; 1 nmol/L hemoglobin is insufficient to promote growth of wild type under these conditions), especially at 12 h but also by the 24 h timepoint. By 36 h, it was apparent that hemoglobin was beginning to promote the growth of the mutant, especially at the higher hemoglobin concentrations. Notably, at the low nM concentrations of hemoglobin (i.e., below 50 nmol/L), the Δisd-sir mutant is significantly attenuated for growth, compared to wild type, even through 36 h of incubation.

Figure 7.

Growth of Staphylococcus lugdunensisWT and its isogenic Δisd mutant using iron, hemoglobin or heme as a sole iron source. Growth of the Δisd-sir mutant was compared to that of WT strain HKU09-01 at 12-, 24-and 36-h timepoints in RPMIC containing FeSO4 (A) varying concentrations of human hemoglobin, (B) or varying concentrations of bovine hemin, (C) as the sole iron source. All data points represent average values for at least three independent biological replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. Statistical significance was determined using the Student's unpaired t-test; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

A similar growth pattern was observed for the Δisd-sir mutant when hemin was used as the sole iron source (Fig. 7C). It is apparent that the isd-sir locus provides a significant growth advantage to S. lugdunensis at early stages of growth at all concentrations tested (up to 1 μmol/L) and continues to provide a significant growth advantage to the cells through 36 h of incubation in the presence of hemin at concentrations below 100 nM (Fig. 7C).

Discussion

S. lugdunensis is a relatively recently recognized bacterium that is both a commensal, and an important human pathogen, capable of causing serious infections such as aggressive native valve infective endocarditis (IE) (Frank et al. 2008). That IE caused by S. lugdunensis can occur independent of indwelling medical devices differentiates S. lugdunensis from other CoNS, and makes it worthy of investigation. Molecular studies of S. lugdunensis are in their infancy and, thus, there is a paucity of information concerning important virulence factors that underpin the potential of this opportunistic pathogen to cause severe and invasive infections. The molecular mechanisms of iron acquisition that are key to the biology and infectivity of this bacterium are essentially unknown. Zapotoczna et al. (2012) examined the role of the iron-regulated surface determinant system in the utilization of hemoglobin and found that, in strain N920143, the Isd-dependent heme/hemoglobin utilization system is functional by demonstrating that an isd deletion mutant and an isdB mutant were both slightly debilitated for growth on hemoglobin as a sole iron source. Moreover, S. lugdunensis IsdG, like its S. aureus counterpart, degrades heme to staphylobilin and free iron (Haley et al. 2011). In this study, we furthered these findings by demonstrating that the tandemly duplicated S. lugdunensis isd locus in strain HKU09-01 was required for promoting early and rapid growth on a wide range of hemoglobin and heme concentrations ranging from 10 to 500 nmol/L and 50–1000 nmol/L, respectively (Fig. 7B and C), eventually leading to increased bacterial biomass that was sustained through 36 h of incubation, especially at the lower concentrations. It is worth noting that these low concentrations of hemoglobin and heme are physiologically relevant, as these molecules are removed from circulation in the liver subsequent to being quickly bound by haptoglobin and hemopexin, respectively.

S. lugdunensis is severely attenuated for growth in iron-restricted media that do not contain a readily utilizable iron source such as heme or hemoglogin. In media containing serum or transferrin, for example, S. lugdunensis is severely compromised for growth compared to S. aureus. We have shown that this growth defect is readily corrected with the introduction of a functional S. aureus SA biosynthetic locus into S. lugdunensis, where the recombinant strain synthesizes and secretes readily detectable amounts of SA into the culture supernatant. Based upon previous studies, it is known that the sfa gene cluster from S. aureus is both necessary, based on the phenotype of sfa mutants (Beasley et al. 2009) and sufficient, based on heterologous cloning in E. coli (Cotton et al. 2009) for SA synthesis.

That the sfa deletion is found in both S. lugdunensis strains where genome sequence is available suggests that this deletion may be common to the species. The deletion (see Fig. 1) removes the promoter for each of the two transcripts sfaD and sfaABC, and also completely removes the sfaA and sfaD genes, encoding the putative SA efflux pump (SfaA) and one of the synthetases that joins a citrate molecule to the δ-amine of d-ornithine to form the first amide intermediate of SA (Cotton et al. 2009). Studies in the early 1990s identified SA in culture supernatants of many species of staphylococci, and that SB was found in supernatants of fewer species (Meiwes et al. 1990; Haag et al.1994). Of the species tested, which did not include a S. lugdunensis representative, only S. sciuri and S. hominis were found incapable of producing either siderophore, but only one strain was tested from each of these species and the result may not reflect the capabilities of the species overall. Based on available genomic data, on the other hand, S. lugdunensis (genome data exist for strains N920143 and HKU09-01) appears to be unique amongst the staphylococci in its inability to synthesize at least one of the two staphyloferrin molecules. This would imply that if other S. lugdunensis strains also lack these loci, the species causes opportunistic infections independent of siderophore production, and would presumably rely on either heme acquisition or uptake of xenosiderophores to satisfy its iron requirements throughout the various stages of colonization and infection. Genomic information identifies that S. lugdunensis has homologs of fhuCBG and sstABCD where predicted products share high levels of similarity with those in S. aureus. This would suggest that S. lugdunensis, like we have previously reported for S. aureus (Sebulsky et al. 2000; Beasley et al. 2011b), is capable of using hydroxamates (via FhuCBG) and catechols/catecholamines (via SstABCD) as a means to acquire iron. The S. lugdunensis FhuC ATPase shares greater than 95% similarity with its S. aureus counterpart and we hypothesize that this ATPase is, like in S. aureus (Speziali et al. 2006), important for providing the energy for not only the uptake of hydroxamate siderophores, but also the staphyloferrins through HtsABC and SirABC.

Interestingly, despite its noted ability to cause serious infection in humans, S. lugdunensis N920143 was reported to cause only very mild infection in a rat model of endocarditis, much milder than that which would be caused by equivalent CFUs of S. aureus (Heilbronner et al. 2013). In pilot experiments, we, too, noted a relative lack of virulence of S. lugdunensis HKU09-01, using the mouse model of hematogenous spread. Mice challenged with up to 1 × 108 CFUs showed no overt signs of illness, and continued to gain weight, despite detectable counts in the kidneys for at least 7 days following bacterial challenge via tail vein. This contrasts from the course of disease that would be caused by a much lower dose of S. aureus. As noted previously (Frank et al. 2008; Tse et al. 2010; Heilbronner et al. 2011, 2013), the S. lugdunensis genome indicates an absence of orthologs of well-centeracterized S. aureus toxin and immune evasion encoding genes, suggestive of a limited capacity to cause severe disease, at least in comparison to S. aureus.

That S. lugdunensis has retained the transport machinery for both SA and SB is interesting, despite an inability to synthesize either siderophore. This may represent a mechanism for scavenging these iron-binding molecules produced by other species of staphylococci, including S. aureus; recall from above that many species of staphylococci produce at least SA. Our data show that coculture of S. aureus with S. lugdunensis in the same iron-limited growth media enhanced the growth of S. lugdunensis by at least one log. This growth enhancement was due to S. lugdunensis’ ability to scavenge the S. aureus staphyloferrins in an Hts-and Sir-dependent manner. We speculate that this is a viable ‘opportunistic’ strategy used by S. lugdunensis in vivo, and the growth-promoting species could be any one of a number of the species of staphylococci that produce at least one of the staphyloferrin molecules. Although S. lugdunensis predominantly inhabits lower parts of the human body (i.e., the perineum) (Böcher et al. 2009) and S. aureus largely inhabits the nares, both species are present to some degree over the entire external surface of the body (Bellamy and Barkham 2002; Bieber and Kahlmeter 2010; Edwards et al. 2012). Indeed, S. lugdunensis is recovered with other bacteria in ∼60% of infections, including co-occurrence with S. aureus and other staphylococci (Herchline and Ayers 1991). It may be that over time S. lugdunensis has evolved to simply steal siderophores produced by other species of bacteria, including S. aureus, and in these situations is more capable of causing opportunistic infections of humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an operating grant to DEH from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The authors would like to thank members of the Heinrichs laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. JRS was supported by a CIHR Frederick Banting & Centerles Best Doctoral Research Award.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding Information

This work was supported by an operating grant to DEH from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

References

- Anguera I, Del Río A, Miró JM, Matínez-Lacasa X, Marco F, Gumá JR. Staphylococcus lugdunensis infective endocarditis: description of 10 cases and analysis of native valve, prosthetic valve, and pacemaker lead endocarditis clinical profiles. Heart. 2005;91:e10. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.040659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias M, Tena D, Apellániz M, Asensio MP, Caballero P, Hernández C. Skin and soft tissue infections caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis: report of 20 cases. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;42:879–884. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.509332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae T, Schneewind O. Allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus with inducible counter-selection. Plasmid. 2006;55:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley FC, Heinrichs DE. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition in the staphylococci. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010;104:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley FC, Vines ED, Grigg JC, Zheng Q, Liu S, Lajoie GA. Centeracterization of staphyloferrin A biosynthetic and transport mutants in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;72:947–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley FC, Cheung J, Heinrichs DE. Mutation of l-2,3-diaminopropionic acid synthase genes blocks staphyloferrin B synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2011a;11:199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley FC, Marolda CL, Cheung J, Buac S, Heinrichs DE. Staphylococcus aureus transporters Hts, Sir, and Sst capture iron liberated from human transferrin by Staphyloferrin A, Staphyloferrin B, and catecholamine stress hormones, respectively, and contribute to virulence. Infect. Immun. 2011b;79:2345–2355. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00117-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy R, Barkham T. Staphylococcus lugdunensis infection sites: predominance of abscesses in the pelvic girdle region. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35:E32–E34. doi: 10.1086/341304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieber L, Kahlmeter G. Staphylococcus lugdunensis in several niches of the normal skin flora. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010;16:385–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böcher S, Tønning B, Skov RL, Prag J. Staphylococcus lugdunensis, a common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in the community. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:946–950. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01024-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J, Beasley FC, Liu S, Lajoie GA, Heinrichs DE. Molecular centeracterization of staphyloferrin B biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;74:594–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan RM, Foster TJ. An improved tetracycline-inducible expression vector for Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid. 2009;61:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton JL, Tao J, Balibar CJ. Identification and centeracterization of the Staphylococcus aureus gene cluster coding for staphyloferrin A. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1025–1035. doi: 10.1021/bi801844c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SE. Involvement of SirABC in iron-siderophore import in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:8356–8362. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8356-8362.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AM, Massey RC, Clarke SR. Molecular mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus nasopharyngeal colonization. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2011.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank KL, Del Pozo JL, Patel R. From clinical microbiology to infection pathogenesis: how daring to be different works for Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:111–133. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freney J, Brun Y, Bes M, Meugnier H, Grimont F, Grimont PAD. Staphylococcus lugdunensis sp. nov. and Staphylococcus schleiferi sp. nov., two species from human clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1988;38:168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gomme PT, McCann KB, Bertolini J. Transferrin: structure, function and potential therapeutic actions. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:267–273. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg JC, Cheung J, Heinrichs DE, Murphy ME. Specificity of staphyloferrin B recognition by the SirA receptor from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 2010a;285:34579–34588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.172924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg JC, Cooper JD, Cheung J, Heinrichs DE, Murphy ME. The Staphylococcus aureus siderophore receptor HtsA undergoes localized conformational changes to enclose staphyloferrin A in an arginine-rich binding pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 2010b;285:11162–11171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.097865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg JC, Ukpabi G, Gaudin CFM, Murphy MEP. Structural biology of heme binding in the Staphylococcus aureus Isd system. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010c;104:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag H, Fiedler H-P, Meiwes J, Drechsel H, Jung G, Zähner H. Isolation and biological centeracterization of staphyloferrin B, a compound with siderophore activity from staphylococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994;115:125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley KP, Janson EM, Heilbronner S, Foster TJ, Skaar EP. Staphylococcus lugdunensis IsdG liberates iron from host heme. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:4749–4757. doi: 10.1128/JB.00436-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer ND, Skaar EP. Molecular mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus iron acquisition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;65:129–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbronner S, Holden MTG, Geoghegan A, van Tonder JA, Foster TJ, Parkhill J. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus lugdunensis N920143 allows identification of putative colonization and virulence factors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011;322:60–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbronner S, Hanses F, Monk IR, Speziale P, Foster TJ. Sortase A promotes virulence in experimental Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis. Microbiology. 2013;159:2141–2152. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.070292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herchline TE, Ayers LW. Occurrence of Staphylococcus lugdunensis in consecutive clinical cultures and relationship of isolation to infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991;29:419–421. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.419-421.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood MI, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:525–537. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner E, Monk AB, Archer GL, Forbes BA. Clinical significance of Staphylococcus lugdunensis isolated from routine cultures. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;51:801–803. doi: 10.1086/656280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiswirth B, Lofdahl S, Bentley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Iandolo JJ. Lysogenic conversion of staphylococcal lipase is caused by insertion of the bacteriophage L54a genome into the lipase structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 1986;166:385–391. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.385-391.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian SK, Ton-That H, Su K, Schneewind O. An iron-regulated sortase anchors a class of surface protein during Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2293–2298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032523999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian SK, Skaar EP, Gaspar AH, Humayun M, Gornicki P, Jelenska J. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;299:906–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1081147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiwes J, Fiedler HP, Haag H, Zahner H, Konetschny-Rapp S, Jung G. Isolation and centeracterization of staphyloferrin A, a compound with siderophore activity from Staphylococcus hyicus DSM 20459. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;55:201–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk IR, Shah IM, Xu M, Tan MW, Foster TJ. Transforming the untransformable: application of direct transformation to manipulate genetically Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. MBio. 2012;3:e00277–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00277-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HL, Novick RP, Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Schlievert P. Cloning, centeracterization, and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4365-4372.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishchany G, Skaar EP. Taste for blood: hemoglobin as a nutrient source for pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002535. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratledge C, Dover LG. Iron metabolism in pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000;54:881–941. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein R, Götz F. What distinguishes highly pathogenic Staphylococci from medium-and non-pathogenic? Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013;358:33–89. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebulsky MT, Hohnstein D, Hunter MD, Heinrichs DE. Identification and centeracterization of a membrane permease involved in iron-hydroxamate transport in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:4394–4400. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4394-4400.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebulsky MT, Speziali CD, Shilton BH, Edgell DR, Heinrichs DE. FhuD1, a ferric hydroxamate-binding lipoprotein in Staphylococcus aureus: a case of gene duplication and lateral transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53152–53159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaar EP, Schneewind O. Iron-regulated surface determinants (Isd) of Staphylococcus aureus: stealing iron from heme. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotutu V, Carapetis J, Wilkinson J, Davis A, Curtis N. The “surreptitious Staphylococcus”: Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis in a child. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2002;21:984–986. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200210000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speziali CG, Dale SE, Henderson JA, Vines ED, Heinrichs DE. Requirement of Staphylococcus aureus ATP-binding cassette ATPase FhuC for iron-restricted growth and evidence that it functions with more than one iron transporter. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2048–2055. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2048-2055.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabados F, Nowotny Y, Marlinghaus L, Korte M, Neumann S, Kaase M. Occurrence of genes of putative fibrinogen binding proteins and hemolysins, as well as of their phenotypic correlates in isolates of S. lugdunensis of different origins. BMC Res. Notes. 2011;4:113. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse H, Tsoi HW, Leung SP, Lau SKP, Woo PCY, Yuen KY. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus lugdunensis strain HKU09-01. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:1471–1472. doi: 10.1128/JB.01627-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC, McGrath BM, Carrell RW. Reactions involving superoxide and normal and unstable haemoglobins. Biochem. J. 1976;155:493–502. doi: 10.1042/bj1550493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapotoczna M, Heilbronner S, Speziale P, Foster TJ. Iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) proteins of Staphylococcus lugdunensis. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:6453–6467. doi: 10.1128/JB.01195-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]