Abstract

Background:

Atrophic acne scars are difficult to treat. The demand for less invasive but highly effective treatment for scars is growing.

Objective:

To assess the efficacy of combination therapy using subcision, microneedling and 15% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) peel in the management of atrophic scars.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty patients with atrophic acne scars were graded using Goodman and Baron Qualitative grading. After subcision, dermaroller and 15% TCA peel were performed alternatively at 2-weeks interval for a total of 6 sessions of each. Grading of acne scar photographs was done pretreatment and 1 month after last procedure. Patients own evaluation of improvement was assessed.

Results:

Out of 16 patients with Grade 4 scars, 10 (62.5%) patients improved to Grade 2 and 6 (37.5%) patients improved to Grade 3 scars. Out of 22 patients with Grade 3 scars, 5 (22.7%) patients were left with no scars, 2 (9.1%) patients improved to Grade 1and 15 (68.2%) patients improved to Grade 2. All 11 (100%) patients with Grade 2 scars were left with no scars. There was high level of patient satisfaction.

Conclusion:

This combination has shown good results in treating not only Grade 2 but also severe Grade 4 and 3 scars.

KEYWORDS: Ablative laser for scars, dermaroller for scars, subcision

INTRODUCTION

Acne is prevalent in over 90% adolescents and it persists into adulthood in approximately 12%-14% of cases with psychological and social implications.[1,2,3] In some patients with acne, the inflammatory response results in permanent, disfiguring scars from either increased tissue formation or due to loss or damage of tissue. Hypertrophic scars and keloids are examples of scars that result from increased tissue formation. Scars with loss or damage of tissue can be classified into icepick, rolling and boxcar scars.[4] There is no standard treatment option for the treatment of acne scars. Medical management of atrophic scars can be done by using topical retinoids. Surgical management can be done using punch excision, elliptical excision, punch elevation, skin grafting and subcision depending on the type of scar. Procedural management includes microdermabrasion, chemical peels, percutaneous collagen induction by microneedling and dermabrasion. Tissue augmentation can be done using xenografts, autografts and homografts. Various ablative and non-ablative lasers and light energies are also available for treatment of atrophic acne scars.[5] Out of these multiple treatment options, treatment has to be tailored to patient's needs, tolerance, and goals along with the physician's assessment, skills and expectation. Patient should be counselled that the ultimate goal of any intervention is to improve the scars and no currently available treatment will attain total cure or perfection.

In 1995, Orentreich and Orentreich described subcision as a method of subcuticular undermining of scars using a tri-beveled hypodermic needle. This results in lifting the scar by releasing the papillary dermis from the binding connections of the deeper tissues and by the formation of connective tissue that results from the course of normal wound healing.[6] It is mainly used for the treatment of rolling type of atrophic scars.[4]

The mechanism hypothesised for action of percutaneous collagen induction using dermaroller is that it creates thousands of microclefts through the epidermis into the papillary dermis. These wounds create a confluent zone of superficial injury which initiates the normal process of wound healing[7] with release of several growth factors. This stimulates the migration and proliferation of fibroblasts resulting in collagen deposition[8] which continues for months after the injury.[9] Another hypotheses states that on penetration of skin with the microneedles, the cells react with a demarcation current which in addition to the needles own electrical potential results in release of various growth factors. This cuts short the healing process and stimulates the healing phase.[10] Dermaroller also opens pores in upper layers of epidermis and allows creams to be absorbed more effectively by the skin.

Fifteen percent tricholoroacetic acid (TCA) peel is superficial peeling agent. It causes exfoliation, improves the skin texture and induces collagen synthesis.[11]

The aim of our study was assessment of combination therapy using subcision, dermaroller and 15% TCA peel for the management of atrophic acne scars. The rationale for combining these three minimally invasive procedures was their additive action on acne scars. Subcision releases the scars from the underlying adhesions which should be the first step for any treatment for acne scars. Microneedling with dermaroller causes collagen induction along with enhancing absorption of tretinoin cream. Fifteen percent TCA peel causes improvement in skin texture as well as collagen induction. Hence by combining these three minimally invasive modalities one can release the scars, enhance collagen induction, increased penetration of topical agents and resurface the skin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

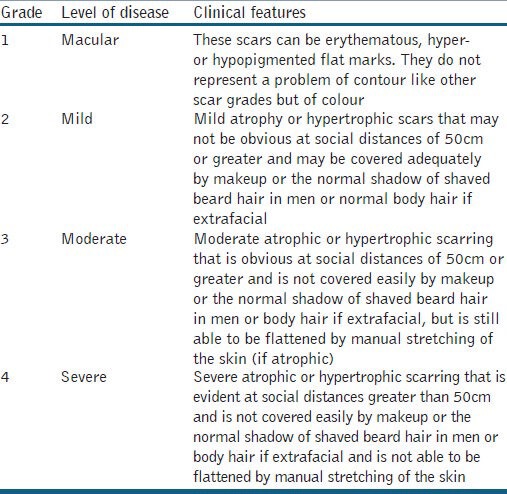

Fifty patients with atrophic acne scars were enrolled in this study. Exclusion criteria were patients with active acne, active herpes labialis, patients on systemic retinoids, evidence or history of keloid scars, pregnancy or lactation, history of any facial surgery or procedure for scars and patients with unrealistic expectations. All the patients were counselled for surgical intervention and written informed consent was taken. The atrophic acne scars were graded by a single non-treating physician using Goodman and Baron Qualitative scar grading system [Table 1].[12]

Table 1.

Goodman and Baron Qualitative scar grading system

Patient's skin was primed using topical tretinoin cream 0.05% at night along with sunscreen with a minimum SPF of 30 during the day for 2 weeks prior to starting the treatment. At the start of treatment, subcision was performed only once using a 24G needle. One day after the subcision, patient was called for the first sitting of microneedling with dermaroller containing 192 needles of needle size 1.5 mm. Eutectic mixture of lignocaine 2% and prilocaine 2% cream was applied under occlusion for 1 hour to the affected areas which was removed using gauze. Thereafter topical tretinoin cream 0.05% was applied to the affected area. Treatment was performed by rolling the dermaroller in vertical, horizontal and diagonal directions in the affected area until appearance of uniform fine pinpoint bleeding. Then the area was wiped with saline soaked gauze and tretinoin cream 0.05% was applied and washed off after 30 minutes. Two weeks after dermaroller, patient was called for 15% TCA peel. Whole face was cleansed using spirit and degreased using acetone. Fifteen percent TCA peel was applied with cotton tipped applicator on full face. Appearance of speckled white frosting was the end point of treatment with peel. After using dermaroller and 15% TCA peel, patient was instructed to apply sunscreen in the morning and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily for 5 days after which sunscreen was continued in the morning with tretinoin cream 0.05% applied at night time. Patient was asked to discontinue topical tretinoin cream application 2 days prior to TCA peel. Thereafter, dermaroller and 15% TCA peel were repeated alternately after every 2 weeks for six sessions of each and this was taken as the end point of our study. In some patients who developed inflammatory lesions of acne during treatment, capsule doxycycline or topical clindamycin cream 1% was given as and when required. Any adverse effects and interference in daily activities post-treatment were noted. Patients were evaluated for results 1 month after the last procedure was performed. Post-treatment scars were graded again by the same physician using Goodman and Baron Scale. Patient graded their response to treatment as poor, good, very good or excellent with 0-24%, 25-49%, 50-74% and 75-100% improvement, respectively, in their acne scars. The patients were followed up for 1 year at two monthly intervals to observe the sustenance of improvement in scars. Digital colour facial photographs were taken before treatment, during each visit of treatment, at 1 month after the last procedure and at 2 monthly intervals for 1 year after the last procedure. Patients were instructed to continue application of topical tretinoin cream 0.05% for 1 year after the last procedure.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation are calculated. Data is presented in frequencies and their respective percentages. Data was entered and analysed using SPSS version 18.

RESULTS

Out of 50 patients, 49 patients completed the treatment. Out of 49 patients 2 patients were treated with capsule doxycycline during the treatment protocol due to active acne eruptions. Out of 49 patients there were 30 females and 19 males with age group between 18-39 years with mean age of 25.6 ± 5.2 yrs. 9 patients (18.4%) had Type III Fitzpatrick skin type, 32 (65.3%) type IV and 8 (16.3%) patients had type V Fitzpatrick skin type. Pre treatment melasma was present in 3 (6%) patients.

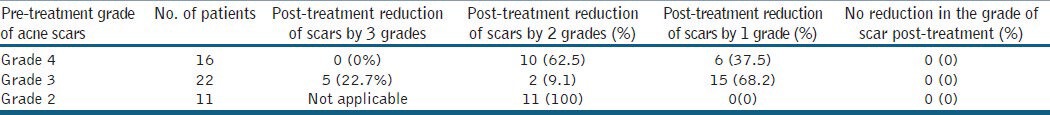

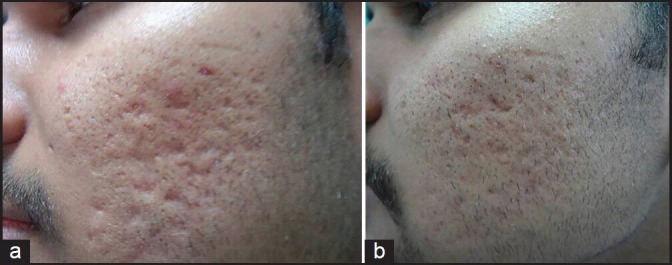

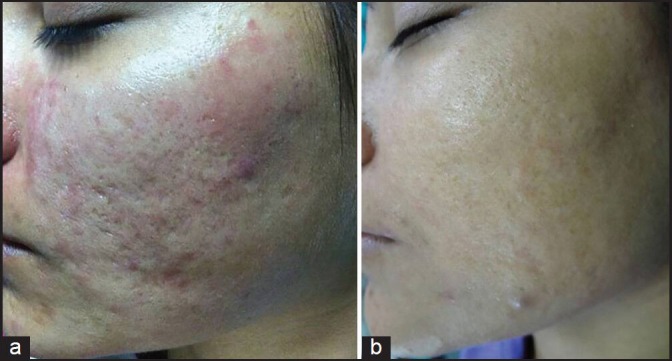

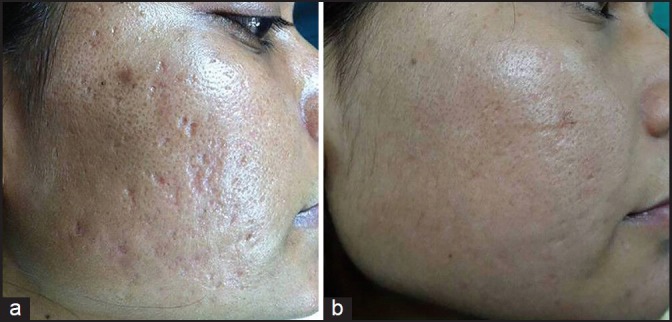

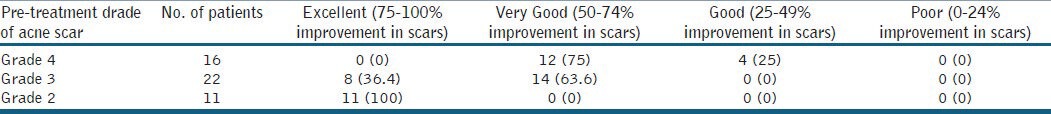

Out of 49 patients who completed the treatment, 16 patients had Grade 4, 22 patients had Grade 3 and 11 patients had Grade 2 scars before treatment. The physician's assessment of response to treatment based on Goodman and Baron Qualitative scar grading system is summarised in Table 2. In patients with Grade 4 scars, 10 patients (62.5%) showed improvement by 2 grades i.e., their scars improved from Grade 4 to Grade 2 of Goodman Baron Scale [Figure 1a and b]. Six patients (37.5%) with Grade 4 scars showed improvement by 1 grade [Figure 2a and b] with scars being obvious at social distances of 50 cm or greater. In 22 patients with Grade 3 scars, 5 patients (22.7%) showed improvement by 3 grades i.e., they were left with no scars at all [Figure 3a and b], Two patients (9.1%) improved by 2 grades and as per Grade 1 they were left with only hyper-pigmented flat marks [Figure 4a and b] and 15 patients (68.2%) showed improvement by 1 grade by moving to Grade 2 [Figure 5a and b] as per Grade 2 their scars were not obvious at social distances of 50cm or greater. All 11 patients (100%) who had Grade 2 scars before treatment showed improvement by 2 grades in their scars and were left with no scars [Figures 6a–b and 7a–b]. Hence all 49 patients (100%) had improvement in their scars by some grade with no failure rate. In patients with Grade 4 scars [Table 3], 12 patients (75%) graded their response to treatment as very good with 50-74% improvement in their acne scars after treatment and 4 patients (25%) had good improvement in their scars with 25-29% improvement. In patients with Grade 3 scars, 8 patients (36.4%) graded their response to treatment as excellent with 75-100% improvement in their scars and 14 patients (63.6%) reported the response as very good with improvement between 50 and 74%. All 11 patients (100%) with Grade 2 scars graded their response after treatment as excellent with improvement between 75 and 100%. Poor response with 0-24% improvement in scars was reported by none of the patients. Improvement in scars was first noted in majority of the patients after completing two sitting of dermaroller and peel. At the end of 1-year of follow-up, it was observed that all the 49 patients sustained the level of improvement in their grade of scars which was attained at the end of the last procedure [Figure 8a–c]. Although improvement in the scars as noticed by the patient and the physician continued in the follow up period of 1 year, there was no further shift in the grade of scars.

Table 2.

Physician's assessment of response to treatment based on Goodman and Baron Qualitative scar grading system

Figure 1.

(a) Grade 4 acne scars; (b) Improvement in acne scars from Grade 4 to Grade 2 after treatment

Figure 2.

(a) Grade 4 acne scars; (b): Improvement in acne scars from Grade 4 to Grade 3 after treatment

Figure 3.

(a) Grade 3 acne scars; (b) Post-treatment patient had no scars

Figure 4.

(a) Grade 3 acne scars; (b) Improvement in acne scars from Grade 3 to Grade 1 after treatment

Figure 5.

(a) Grade 3 acne scars; (b) Improvement in acne scars from Grade 3 to Grade 2 after treatment

Figure 6.

(a) Grade 2 acne scars; (b) Post-treatment patient had no scars

Figure 7.

(a) Grade 2 acne scars; (b) Post-treatment patient had no scars

Table 3.

Patient's assessment of response to treatment

Figure 8.

(a) Grade 4 acne scars; (b) Improvement in acne scars from Grade 4 to Grade 2 after treatment; (c): Sustenance of improvement in acne scars from Grade 4 to Grade 2 at 1 year of follow-up

There was improvement in rolling, boxcar and linear tunnel type of scars with little or no improvement in ice pick scars. All patients tolerated the procedure well. Side effects were mild and transient. Post-dermaroller transient erythema and oedema lasted for 1-4 days with a mean of 2.4 ± 0.7 days. Post-peel exfoliation of skin was present from 2 to 7 days with a mean of 4.4 ± 1 day. Only three patients (6%) developed post-inflammatory hyper-pigmentation (PIH) which was treated with sunscreen in the morning and triple combination of tretinoin, hydroquinone and mometasone at night time. The PIH subsided after 5 months of topical treatment. One patient (2%) developed mildly tender cervical lymphadenopathy each time after dermaroller which lasted for around 3 weeks and subsided on its own. There was no interference in daily activity with no loss of days at work.

DISCUSSION

This study has shown good results in patients with severe Grade 4 and 3 acne scars with 10 (62.5%) patients with Grade 4 scars moving to Grade 2 and 5 (22.7%) patients with Grade 3 scars improving to have no scars at the end of treatment. In Grade 2 scars all the 11 patients (100%) showed improvement by 2 grades and were left with no scars. Hence, all 49 (100%) patients showed improvement in their scars by some grade with no failure rate. The physician's analysis also correlated with the patient's assessment of improvement in scars with 12 (75%) patients with Grade 4 scars reporting improvement as very good, 8 (36.4%) patients with Grade 3 scars as excellent and 11 (100%) patients with Grade 2 scars as excellent with poor response reported by none of the patients. The procedure was well tolerated by all the patients. Post-procedure there was no loss of work days and side effects were mild and transient. In spite of patients being of Type III, IV and V Fitzpatrick skin type, only three patients (6%) developed PIH during the treatment, which subsided within 5 months of topical therapy. It has the advantage of being an office procedure and in being cost-effective. Topical tretinoin 0.05% favours the development of a regenerative lattice-patterned collagen network rather than the parallel deposition of scar collagen found with cicatrisation. Since dermaroller opens pores in the upper layer of epidermis and allows creams to be absorbed more effectively, it is for this reason that topical tretinoin was applied during dermaroller and kept for 30 minutes post-procedure to maximise its absorption in skin. Also the improvement in the grade of scars was sustained in the follow-up period of 1 year.

Although ablative laser resurfacing is generally considered to be the most effective option for scar resurfacing, it is associated with significant damage to the epidermis and basal membrane with associated inflammation which causes erythema, scarring and pigmentation problems.[13,14,15] It also has a long downtime. In comparison, percutaneous collagen induction does not induce post-operative dyspigmentation as the epidermis and basal membrane are left intact.[16]

CONCLUSIONS

As the demand for less invasive, highly effective cosmetic procedures is growing, this combination of treatment for acne scars has shown good results not only in Grade 2 but also in severe Grade 4 and 3 acne scars. The treatment is well tolerated in Fitzpatrick skin types III, IV and V with no failure rates or loss of days at work. There is a high level of patient satisfaction, minimal downtime and the treatment is cost-effective to the patient. To our knowledge, this is the first study using this combination of therapy in the management of atrophic acne scars and the first in which topical tretinoin cream was applied both during and immediately after doing dermaroller.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghodsi SZ, Orawa H, Zouboulis CC. Prevalence, severity, and severity risk factors of acne in high school pupils: A community-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2136–41. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams C, Layton AM. Persistent acne in women: Implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin dermatol. 2006;7:281–90. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capitanio B, Sinagra JL, Bordignon V, Cordiali Fei P, Picardo M, Zouboulis CC. Underestimated clinical features of postadolescent acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:782–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob CI, Dover JS, Kaminer MS. Acne scarring: A classification system and review of treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:109–17. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.113451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivera AE. Acne scarring: A review and current treatment modalities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:659–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:543–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flabella AF, Falanga V. Wound healing. In: Feinkel RK, Woodley DT, editors. The Biology of the Skin. New York: Parethenon; 2001. pp. 281–97. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabbrocini G, Farella N, Monfrecola A, Proietti I, Innocenzi D. Acne scarring treatment using skin needling. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:874–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen KI, Diegelmann RF, Lindbland WJ. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1992. Wound healing; biochemical and clinical aspects. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaffe L. Control of development by steady ionic currents. Fed Proc. 1981;40:125–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse Y. Choosing the correct peel for the appropriate patient. In: Rubin MG, Dover JS, Alam M, editors. Chemical Peels. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc; 2006. pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: A qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy D. Ablative facial resurfacing. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:549–59. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross EV, Naseef GS, McKinlay JR, Barnette DJ, Skrobal M, Grevelink J, et al. Comparision of carbon dioxide laser, erbium: YAG laser, dermabrasion, and dermatome: A study of thermal damage, wound contraction, and wound healing in a live pig model. Implications for skin resurfacing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:92–105. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein LJ, Kauvar AN, Grossman MC, Geronemus RG. The short- and long-term side effects of carbon dioxide laser resurfacing. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:519–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aust MC, Reimers K, Repenning C, Stahl F, Jahn S, Guggenheim M, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction: Minimally invasive skin rejuvenation without risk of hyperpigmentation-fact or fiction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1553–63. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318188245e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]