Abstract

Objective

To estimate the impact of trends in smoking and obesity prevalence on productivity loss among petrochemical employees from 1980 to 2009.

Methods

Smoking and obesity informations were collected during company physical examinations. Productivity loss was calculated as differential workdays lost between smokers and non-smokers, and obese and normal-weight employees.

Results

During 1980–2009, smoking prevalence decreased from 32% to 17%, while obesity prevalence increased from 14% to 42%. In 1982, lost productivity from obesity was an estimated 43 days/100 employees, and for smoking, 65 days/100 employees, but by 1987, workdays lost due to obesity exceeded that attributable to smoking. In 2007, workdays lost from obesity were 3.7 times higher than for smoking.

Conclusions

Owing to the increasing trend in obesity, the productivity impact on employers from obesity will continue to rise without effective measures supporting employee efforts to achieve healthy weight through sustainable lifestyle changes.

Keywords: Occupational & Industrial Medicine, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large study population and followed for more than 30 years.

Clinical assessment of body mass index and smoking status, that is, data were collected during physical examination.

Prevalence rates for smoking and obesity were adjusted by gender and work status.

Unavailability of actual company absence data to use in lost productivity estimates.

Introduction

Smoking and obesity are two major health risk factors facing many populations today. The impact of these factors in the workplace is an issue beyond personal health. Obesity is a major contributor to productivity loss for US business: an estimated $43 billion/year.1 The health hazards of smoking have received the most public attention among major lifestyle risks in the past 40 years due in part to the publicity of the annual US Surgeon General's reports on smoking from the 1960s.2 As a result, smoking prevalence among American adults over the past 40 years has steadily declined from 37.4% in 19703 to 22.5% in 20024 and to 20.6% in 2008.5 Factors contributing to the decrease include smoking bans, media campaigns against smoking, higher cigarette taxes and insurance coverage for smoking cessation programmes.2 6 On the other hand, there has been a large rise in obesity prevalence over the same period. The prevalence of obesity for Americans over the age of 20 years has increased from 14.6% in 1971–19747 to 30% in 20028 and to 34% in 2008.8

Productivity loss attributable to smoking and obesity is important to industry. Several studies have reported that smoking employees have substantially greater absenteeism than non-smoking employees. Based on a survey of cigarette smoking and sick leave at a large petrochemical complex in China, Wang and Dobson reported that on average, smokers missed three additional workdays due to illness each year than non-smokers.9 Tsai et al10 examined employees at several Shell Oil Company facilities and estimated an excess sick leave of approximately 3 days among smokers. Other studies have reported that smokers miss more workdays than non-smokers, ranging from 0.9 to 13.5 days, with an average excess of 2.1 sick days.11–13

A relatively small number of studies have attempted to examine the relationship between obesity and duration of illness absence. Based on a 10-year follow-up study in the USA, obese employees of a petrochemical company missed an average of 3.7 extra workdays per year compared to normal weight persons.14 A study conducted on employees from London Underground Ltd reported that obese persons typically took an extra 4 days of sick leave every year compared to normal weight persons,15 and a prospective study of a Dutch working population reported that obese employees were absent 14 days more per year than normal-weight employees.16 In a recent systematic review, Neovius et al17 reported that obese American workers had approximately one to three additional illness absence days per year, and obese European workers had about 10 additional days compared with their respective normal weight counterparts.

While numerous studies have been conducted on various health and economic impacts of smoking trends,2 studies on the impact of increasing obesity prevalence over time, particularly those related to illness absence in working populations, have been limited. In recent years, comparisons of the long-term effect of obesity and smoking on mortality have been reported18–20; however, the short-term effect of obesity on productivity has rarely been quantified.21 This lack of comparable studies is due in part to the relatively ‘new’ risk status of obesity as compared to the long established risk status of smoking. Similar to smoking, obesity is associated with increasing healthcare costs, productivity loss and risk of various chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, hypertension and osteoarthritis,17 22 23 and even a modest weight reduction can have substantial lifetime health and economic benefits.24

The purpose of this paper was to examine the changing trends in smoking and obesity prevalence during a 30-year period (1980–2009) in a population of petrochemical workers, and to simulate the resulting impact on productivity due to these two risk factors.

Methods

Permission and assurance of confidentiality are required to access the data that is used in the study. Smoking and obesity prevalence data were extracted from physical examination records in the Shell Health Surveillance System (HSS), the data system used in the Company's ongoing monitoring of employee health.25 26 The HSS comprises demographic, work history, illness absence and physical examination (ie, health history, preplacement, periodic examinations) data for all US employees since 1978. The frequency of periodic examinations, as well as participation in the various examination programmes, differed depending on the type of examination and age of the employee. For example, surveillance examinations were generally performed annually, and since they were mandated by the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration, they had participation rates near 100%. Preemployment physical examinations were required prior to placement in certain positions and also had nearly complete participation. Voluntary examinations were offered to all employees every 1–5 years, depending on the age of the employee, that is, older employees were allowed more frequent examinations. Approximately 30% of employees participated in the voluntary examination programme during the study period.

Self-reported smoking data were collected on 65% of physical examinations along with other medical history information. Responses to smoking history questions were used to determine the smoking status of each employee (ie, current smoker, former smoker or never-smoker). A current smoker was defined as a person who currently smoked (ie, responded yes to a question about smoking cigarettes) and who had smoked 100 or more cigarettes during his/her lifetime. This definition is consistent with that used by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the National Health Interview Survey. Height and weight were measured and reported for 75% of physical examinations performed during the study period. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as BMI=weight (kg)/height2 (m2). Normal weight was defined as BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 and obesity as BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

Approximately 6200 employees had BMI data in 1980–1984, 7000 in 1985–1989, 8000 in 1990–1994, 9500 in 1995–1999, 14000 in 2000–2004 and 6500 in 2005–2009. Over 85% of these employees also had smoking data. The substantially reduced number of examinations in 2005–2009 was due to a change in company policy in 2007 which limited the scope of company periodic examinations. The latest examination containing smoking and BMI information during each of six periods (1980–1984, 1985–1989, 1990–1994, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009) was used in the analysis. The value for the mid-year of each of these 5-year time periods, that is, 1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007, represents an average for that period. The total number of employees during the study period ranged from 20 000 to 28 000.

Illness absence data are one of the major components of the HSS. While employee illness absence events were consistently recorded for employees who had absences lasting 5 days or more during the study period, they were incomplete for absences of less than 5 days, especially during the 1980s and 1990s. Therefore, the actual company absence data are not able to fully describe the impact on productivity. As an alternative, and based on our review of the relevant literature described earlier, we used a conservative estimate of two additional sick days per year for smokers and three additional sick days per year for obese persons in the calculation of productivity loss. We used the workdays lost per 100 employees as the outcome measure. We also performed two sensitivity analyses to assess a range of possible values for productivity loss when different assumptions were used for excess days lost due to obesity and smoking. The first used two extra sick days for both smokers and obese persons, and the second used three extra sick days for smokers and two extra sick days for obese persons.

Directly adjusted prevalence rates for smoking and obesity by gender and work status (production/staff) for the six time periods were computed with the distribution of gender and work status of the last time period, that is, 2005–2009, as the standard. This standardisation was necessary because of the varying proportions of men and women, and production and staff employees who took physical examinations over the study period. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS System Software V.8.2.

This study did not involve follow-back investigations, contact with employees or next of kin, or identification of any employee in our results. Data used in our analysis included only information collected in the course of Company physical examinations. Collection and analysis of HSS data is considered to be a routine Health Department activity of which employees are kept informed of results. For these reasons, the study was not reviewed by an ethics committee and no informed consent was requested from employees.

Results

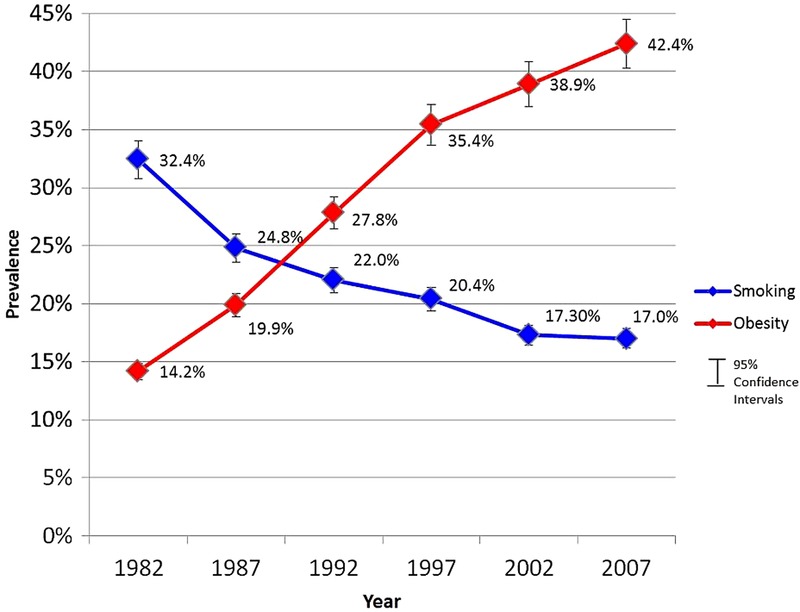

Prevalence of cigarette smoking among Shell employees during the past 30 years has gradually decreased. Approximately one-third (32.4%) of employees smoked in 1982; however, there was a large decline during the subsequent 15 years. Smoking prevalence decreased to 20.4% by 1997 and gradually levelled off to 17% in 2007 (figure 1). Conversely, the proportion of obese employees increased steadily during this period. In the 1980s, the prevalence of obesity was less than 20% (14.2% in 1982 and 19.9% in 1987). However, the rate climbed considerably by the early 2000s, almost doubling to 38.9%. The prevalence of obesity reached the same level as smoking, approximately 24%, around 1990. By 2007, 42% of our employee population was obese.

Figure 1.

Changing trends in prevalence of smoking and obesity in the Shell workforce, 1980–2009.

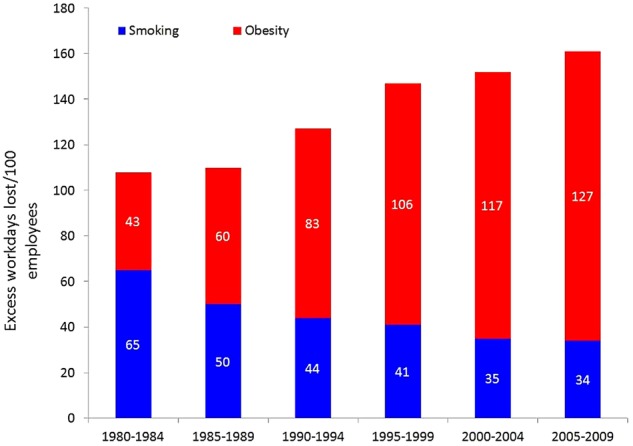

Table 1 shows the changing trends of workdays lost attributable to smoking and obesity, using an average of two excess sick days for smokers and three excess days for obese persons. Productivity loss in terms of excess absenteeism was estimated to be 43 days/100 employees for obesity and 65 days/100 employees for smoking in 1982, with a ratio of 0.66. By 1987, workdays lost due to obesity exceeded those attributable to smoking, with 60 excess workdays lost per 100 employees from obesity and 50 days/100 employees from smoking, and this pattern continued through the duration of the study period. The contribution of obesity to workdays lost increased dramatically beginning in the early 1990s and was 3.7-fold higher than smoking by 2007, with 127 and 34 workdays lost per 100 employees due to obesity and smoking, respectively. It is noteworthy that excess lost workdays from these two risk factors was 50% greater in 2007 than in 1982 (figure 2), as productivity improvements that might have accrued from reduced smoking were more than offset by the steep increase in obesity prevalence. During the 30-year study period, obesity accounted for two-thirds of all excess lost workdays for these two risk factors.

Table 1.

Prevalence of obesity and smoking and their impact on estimated excess workdays lost per 100 Shell Oil Company employees, 1980–2009

| Mid-year of each time period* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 1987 | 1992 | 1997 | 2002 | 2007 | |

| Prevalence (%) | ||||||

| Obesity | 14.2 | 19.9 | 27.8 | 35.4 | 38.9 | 42.4 |

| Smoking | 32.4 | 24.8 | 22.0 | 20.4 | 17.3 | 17.0 |

| Excess workdays lost per 100 employees | ||||||

| Obesity | 43 | 60 | 83 | 106 | 117 | 127 |

| Smoking | 65 | 50 | 44 | 41 | 35 | 34 |

| Ratio | 0.66 | 1.20 | 1.90 | 2.60 | 3.37 | 3.74 |

*Prevalence and excess workday values for the mid-year of each time period (ie, 1980–1984, 1985–1989, 1990–1994, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009) represent an average for that period.

Figure 2.

Excess workdays lost per 100 Shell employees due to obesity and smoking, 1980–2009.

We also conducted two sensitivity analyses using different assumptions for excess days lost for smokers and obese employees by varying the number of additional sick days due to these risk factors to: (1) two extra days for both obesity and smoking and (2) two extra days for obesity and three extra days for smoking. As shown in table 2, the patterns did not change, although productivity loss due to obesity did not exceed that of smoking until the 1990s.

Table 2.

Range of estimated excess workdays lost due to obesity and smoking based on alternative assumptions for differential productivity loss per 100 Shell Oil Company employees, 1980–2009

| Mid-year of each time period* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 1987 | 1992 | 1997 | 2002 | 2007 | |

| Excess workdays lost: obesity (2 days), smoking (2 days) | ||||||

| Obesity | 28 | 40 | 56 | 71 | 78 | 85 |

| Smoking | 65 | 50 | 44 | 41 | 35 | 34 |

| Ratio | 0.44 | 0.80 | 1.26 | 1.74 | 2.25 | 2.50 |

| Excess workdays lost: obesity (2 days), smoking (3 days) | ||||||

| Obesity | 28 | 40 | 56 | 71 | 78 | 85 |

| Smoking | 97 | 74 | 66 | 61 | 52 | 51 |

| Ratio | 0.29 | 0.53 | 0.84 | 1.16 | 1.50 | 1.66 |

*Excess workday values for the mid-year of each time period (ie, 1980–1984, 1985–1989, 1990–1994, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009) represent an average for that period.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the impact of changing trends in smoking and obesity prevalence on productivity in a population of industrial workers. In the early 1980s, workdays lost attributable to obesity was 34% lower than smoking; however, by 2007 it was 3.7 times higher. The negative effect of increasing obesity rates on productivity of this workforce surpassed that of smoking as early as 1987.

At the beginning of the study, the number of lost workdays attributable to obesity was 43/100 employees. During the 30-year study period, workdays lost due to obesity increased to 127/100 employees. The economic impact of this on an employer, in terms of lost productivity, is alarming. Based on an average annual wage of $60 000 ($256/day), the direct costs of obesity can be estimated. At the end of 30 years, and assuming a workforce of 20 000 employees, the potential economic impact due to illness-absence from obesity would be $6.5 million/year.

The changing patterns of obesity and smoking in this population during the study period were similar to those of the US general population.27 Prevalence of obesity among our employees increased from 14% in the early 1980s to 42% in 2007 while prevalence of smoking decreased from 32% to 17%. Factors attributable to the decline in smoking prevalence of this working population have been discussed in an earlier paper.28 However, the reasons for the persistently increasing prevalence of obesity are not immediately clear. It is possible that the decline of smoking has led to an increase in obesity, since smoking is associated with lower body weight and smoking cessation is associated with weight gain.27 29 30 One study has suggested that a reduction in smoking prevalence has been linked to an increase in obesity;29 however, this finding was not confirmed by other researchers investigating the same issue but with different methodology.27 A recent study conducted by Flegal30 of the US National Center for Health Statistics found that decreasing rates of cigarette smoking probably had only a small effect, less than 1%, on increasing rates of obesity in the US population. Therefore, it is unlikely that increased rates of obesity in this workforce were due to decreasing smoking rates.

One limitation of our study was the unavailability of actual company absence data to use in lost productivity estimates. Although absence data were collected throughout the 30-year follow-up period, variability in company absence reporting requirements resulted in only longer absences (6+ days) collected in earlier years and all absences (regardless of length) collected in the latter part of the study period. In addition, divestments and acquisitions of businesses and sites meant that the composition of the study population changed over time. Given these inconsistencies, and length of the study period, we relied on more stable published estimates of incremental days lost in our calculations.

Estimates of lost productivity attributable to obesity and smoking are highly dependent on assumptions regarding differential sick days between obese and normal weight persons and between smokers and non-smokers. In the calculation of workdays lost, we used three additional sick days per year for obese persons and two additional days for smokers, based on the existing literature. These estimates seem reasonable given that compared to smoking, obesity has a much larger contribution to the development of chronic conditions and spending on healthcare and medications.21

Another limitation of this study was our inability to assess potential confounders. Illness absence in a working population is a complex phenomenon including many factors, such as diet, physical activity, personal health risk factors and work-related factors.31–33 However, the strength of the study lies in the large population, followed for more than 30 years, with clinical assessment of BMI and smoking status.

While reducing the prevalence of obesity will clearly lead to a reduction in premature mortality and increased productivity, these will not happen immediately. In our workforce, we have initiated health programmes and interventions aimed at creating a positive and supportive environment for employees attempting to increase their physical activity (ie, exercise rooms and walking trails), and reduce weight (ie, healthy food offerings at work). We have also redesigned company health insurance programmes to promote preventive care and reward wellness activities. These programmes represent the efforts of health and benefits leaders, and are reinforced by onsite and online educational activities, and role-modelling and support by site leadership. The earlier weight management and health promotion programmes are introduced, the sooner employees and employers will reap their benefits. These programmes should be an urgent and joint priority of corporate health leaders and benefits managers to achieve sustainable change in employee health behaviours and to minimise the future impact of obesity on employee productivity.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FAB and SPT developed the aim and scope of the study. SPT and JKW carried out the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretations and to the final manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study did not involve follow-back investigations, contact with employees or next of kin or identification of any employee in our results. Data used in our analysis included only information collected in the course of Company physical examinations. Collection and analysis of Health Surveillance System (HSS) data is considered to be a routine Health Department activity of which employees are kept informed of results. For these reasons, the study was not reviewed by an ethics committee and no informed consent was requested from employees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Finkelstein EA, DiBonaventura MD, Burgess SM, et al. The costs of obesity in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:971–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and tobacco use: history of the surgeon general's report on smoking and health. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/history/index.htm (accessed: 12 Nov 2013).

- 3.Mendez D, Warner K. Adult cigarette smoking prevalence: declining as expected (not as desired). Am J Public Health 2004;94:251–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2000. MMWR 2002;51:642–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation—United States, 2008. MMWR 2009;58:1227–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cokkinides V, Bandi P, McMahon C, et al. Tobacco control in the United States—recent progress and opportunities. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:352–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002;288:1723–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA 2010;303:235–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang WQ, Dobson AJ. Cigarette smoking and sick leave in an industrial population in Shanghai, China. Int J Epidemiol 1992;21:293–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai SP, Gilstrap EL, Colangelo TA, et al. Illness absence at an oil refinery and petrochemical plant. J Occup Environ Med 1997;39:455–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertera RL. The effect of behavioral risks and health-care cost in the workplace. J Occup Med 1991;33:1119–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelloway EK, Barling J, Weber C. Smoking and absence from work—a quantitative review. In: Koslowsky M, Krausz M, eds Voluntary employee withdrawal and inattendance. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2002:167–78 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai SP, Wendt JK, Ahmed FS, et al. Illness absence patterns among employees in a petrochemical facility: impact of selected health risk factors. J Occup Environ Med 2005;47: 838–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai SP, Ahmed FS, Wendt JK, et al. The impact of obesity on illness absence and productivity in an industrial population of petrochemical workers. Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey SB, Glozier N, Carlton O, et al. Obesity and sickness absence: results from the CHAP study. Occup Med (Lond) 2010;60:362–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jans MP, van den Heuvel SG, Hildebrandt VH, et al. Overweight and obesity as predictors of absenteeism in the working population of the Netherlands. J Occup Environ Med 2007;49:975–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neovius K, Johansson K, Kark M, et al. Obesity status and sick leave: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2009;10:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart ST, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Forecasting the effects of obesity and smoking on U.S. life expectancy. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2252–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291:1238–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flegal KM, Grubard BI, Williamson DF, et al. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 2005;293:1861–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sturm R. The effects of obesity, smoking, and drinking on medical problems and costs. Health Aff 2002;21:245–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson D, Edelsberg J, Kinsey KL, et al. Estimated economic costs of obesity to U.S. business. Am J Health Promt 1998;13:120–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orzano AJ, Scott JG. Diagnosis and treatment of obesity in adults: an applied evidence-based review. J Am Board Fam Pract 2004;17:359–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyner RE, Pack PH. The Shell Oil Company's computerized health surveillance system. J Occup Med 1982;24:812–14 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai SP, Dowd CM, Cowles SR, et al. Prospective morbidity surveillance of Shell refinery and petrochemical employees. Br J Ind Med 1991;48:155–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruber J, Frakes M. Does falling smoking lead to rising obesity? J Health Econ 2006;25:183–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai SP, Wendt JK, Hunter RB. Trends in cigarette smoking among refinery and petrochemical plant employees with a discussion of the potential impact on lung cancer. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2001;74:477–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou SY, Grossman M, Saffer H. An economic analysis of adult obesity: results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Health Econ 2004;23:565–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flegal KM. The effect of changes in smoking prevalence on obesity prevalence in the United States. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1510–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alavania SM, van der Berg TIJ, van Duivenbooden C, et al. Impact of work-related factors, lifestyle, and work ability on sickness absence among Dutch construction workers. Scan J Work Environ Health 2009;35:325–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laaksonen M, Piha K, Martikainen P, et al. Health-related behaviours and sickness absence from work. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:840–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labriola M, Lund T, Burr H. Prospective study of physical and psychosocial risk factors for sickness absence. Occup Med 2006;56:469–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.