Abstract

Objective

To determine the potential role of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in screening for and predicting prognosis in heart failure by examining diagnosis and survival of patients with a raised NT-proBNP at screening.

Design

Survival analysis.

Setting

Prospective substudy of the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study (ECHOES) to investigate 10-year survival in participants with an NT-proBNP level at baseline.

Participants

594 participants took part in the substudy. Records of all participants in the ECHOES cohort were flagged during the screening phase which ended on 25 February 1999. All deaths until 25 February 2009 were coded.

Outcome measures

Logistic regression was used to examine whether NT-proBNP is useful in predicting heart failure at screening after adjustment for age, sex and cohort. Kaplan-Meier curves and log rank tests were used to compare survival times of participants according to NT-proBNP level. Cox regression was carried out to assess the prognostic effect of NT-proBNP after allowing for significant covariates and receiver operator curves were used to determine test reliability.

Results

The risk of heart failure increased almost 18-fold when NT-proBNP was 150 pg/mL or above (adjusted OR=17.7, 95% CI 4.9 to 63.5). 10-year survival in the general population cohort was 61% (95% CI 48% to 71%) for those with NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL and 89% (95% CI 84% to 92%) for those below the cut-off at the time of the initial study. After adjustment for age, sex and risk factors for heart failure, NT-proBNP level ≥150 pg/mL was associated with a 58% increase in the risk of death within 10 years (adjusted HR=1.58, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.30).

Conclusions

Raised NT-proBNP levels, when screening the general population, are predictive of a diagnosis of heart failure (at a lower threshold than guidelines for diagnosing symptomatic patients) and also predicted reduced survival at 10 years.

Keywords: Heart failure, Prognosis, Natriuretic peptides, Screening, Diagnosis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study (ECHOES) cohort represents a well-phenotyped group with accurate mortality data.

Not all participants in the ECHOES cohort had an N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide measurement but the characteristics of the subgroup were similar to the whole cohort so are likely to be generalisable.

By definition the study reports a long term follow-up (minimum of 10 years) but over this time both the diagnostic criteria and management of heart failure have changed significantly.

Introduction

Biomarkers can be useful in diagnosis, treatment monitoring and to inform prognosis.1–3 B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) are released by the ventricles of the heart in response to volume and pressure overload. BNP relaxes vascular smooth muscle to reduce ventricular preload and acts on the kidney to increase sodium excretion and induce diuresis.4 NT-proBNP is an inactive fragment of the cleaved pro-BNP molecule. Both peptides have been investigated for use in diagnosis of heart failure (HF) and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD).5 6 NT-proBNP and BNP assays have been found to be equally reliable for diagnostic use.7 Raised natriuretic peptide levels have consistently been associated with increased mortality in patients with HF.8 9 There may also be a role for these assays in determining prognosis in patients with and without HF.10

The Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening (ECHOES) study was a large HF screening study carried out in central England.11 All ECHOES participants underwent a detailed initial clinical assessment to screen for evidence of HF. Diagnosis was determined after blinded adjudication by a panel of three HF specialists using all the clinical and investigation data available from the screening. All deaths were collated from routine mortality data. We previously reported the 10-year prognosis of all patients in the ECHOES study according to presence or absence of HF and LVSD.12 This analysis uses data from ECHOES to examine the role of NT-proBNP in predicting a diagnosis of HF at screening and also the relationship between NT-proBNP and survival in the following decade.

Methods

The original ECHOES study screened a total of 6162 participants from 16 practices in central England. Four practices were randomly selected from each of the four socioeconomic groups defined using the Townsend deprivation score. This resulted in a socioeconomically diverse population, likely to be representative of the broader UK population. ECHOES included four separate cohorts: 3960 patients randomly sampled from the general population over age 45; 782 patients with a previous label of HF recorded in general practitioner (GP) notes; 928 patients on diuretic therapy and 1062 with known risk factors for heart disease (hypertension, diabetes, angina, history of myocardial infarction (MI)). The four cohorts were stipulated prior to the study and searches were carried out to find patients in each of these groups using general practice records. Patients underwent assessment (history, examination, ECG and echocardiography) to screen for evidence of HF.

A substudy involving 594 ECHOES participants was also carried out to investigate the role of NT-proBNP in diagnosis and prognosis of HF. Fuller methods are available in an earlier publication11 but in brief, participants came from four general practices, across the Townsend scale; 309 were sampled from the general population, 103 with a previous label of HF, 88 on diuretic therapy and 134 with risk factors of heart disease with some patients belonging to more than one cohort.

During the ECHOES study, which ran from March 1995 to February 1999, the records of all participants were flagged by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Central Register Office. The ONS has provided details of the date and cause of death for all ECHOES participants since then. The final participant in the original ECHOES cohort was screened on 25 February 1999 and all deaths up to 25 February 2009 had been notified to the research team. This allowed an estimate of 10-year prognosis for patients in ECHOES including those from the NT-proBNP study. All data from the original ECHOES cohort were recorded in a restricted access database. The statistical packages SPSS and Stata V.10 were used to analyse the data.

Analytical methods

Area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) was calculated for each cohort to measure the natriuretic peptide's performance in predicting HF at screening. Multiple logistic regression was then performed, using all cohorts combined, to examine whether BNP was predictive of HF, after adjustment for the sampling structure and other significant predictors. Variables in the final model were selected using the backward elimination method with significance level set at 0.05.

Variables considered in the analysis included NT-proBNP, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, blood pressure, individual risk factors for HF (hypertension, angina, MI, diabetes), symptoms (tiredness, shortness of breath, ankle oedema), prescribed drugs (β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and diuretics) and whether a previous label of HF was recoded. Two-way interactions with natriuretic peptide were also considered. The cohort-related variables were kept in the final model to allow for the sampling structure. To improve the precision of the estimates, bootstrapped CIs for ORs were calculated using 1000 replications.

Survival analysis was carried out by each cohort using Kaplan-Meier curves to demonstrate survival in those with an NT-proBNP level ≥150 pg/mL. Log rank tests were used to compare survival between the different groups. The mean survival times were calculated rather than median since data was censored for more than 50% of cases. Estimation of the mean is limited to the largest survival time if data were censored.

Cox regression was then undertaken, using all 594 participants, to assess the prognostic ability of NT-proBNP after allowing for each cohort and other covariates. Variables entered into the starting model are as described previously with the addition of atrial fibrillation, ejection fraction and significant valve disease. Fractional polynomials were considered when comparing models of best fit for continuous variables of age, BMI and blood pressure. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals.

Results

NT-proBNP levels were measured in 594 participants during the ECHOES study. An HF diagnosis was confirmed for 7 (8%) of those in the general population sample; 36 (35%) of those with a previous label of HF; 15 (17%) of those on diuretics and 9 (7%) of those at high risk. Twenty-three (43%) of all those with an HF diagnosis had an ejection fraction of less than 40% and an additional 10 persons (19%) had ejection fraction of between 40% and 49%.

The baseline characteristics of all participants in the substudy, broken down by cohort and NT-proBNP 150 pg/mL cut-off, are shown in table 1. Those in the upper NT-proBNP category were older, had more cardiovascular risk factors and took more medication than those below 150 pg/mL. They also, with exception of those from the cohort with previous label of HF, had more symptoms of HF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the ECHOES NT-proBNP substudy

| Characteristics | General population (n=309) |

Previous label of HF (n=103) |

On diuretics (n=88) |

High risk (n=134) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT-proBNP <150 pg/mL (n=240) | NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL (n=69) | NT-proBNP <150 pg/mL (n=21) | NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL (n=82) | NT-proBNP <150 pg/mL (n=33) | NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL (n=55) | NT-proBNP <150 pg/mL (n=67) | NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL (n=67) | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age at screening (mean (SD) years) | 59.6 (8.7) | 71.7 (9.7) | 72.2 (9.6) | 74.7 (8.4) | 63.2 (8.8) | 74.1 (9.8) | 63.2 (8.7) | 70.4 (8.2) |

| Gender, male | 130 (54) | 31 (45) | 9 (43) | 47 (57) | 24 (73) | 26 (47) | 43 (64) | 33 (49) |

| Ever smoked | 137 (57) | 37 (54) | 17 (81) | 45 (55) | 21 (64) | 32 (58) | 42 (63) | 48 (72) |

| Body mass index (mean (SD) kg/m2) | 27.0 (4.9) | 25.8 (3.8) | 31.1 (8.5) | 26.6 (4.4) | 27.9 (3.5) | 26.8 (4.5) | 28.4 (4.1) | 27.1 (3.8) |

| Systolic BP (mean (SD) mm/Hg) | 149.3 (20.9) | 156.1 (23.3) | 162.9 (18.3) | 149.2 (26.3) | 161.7 (22.6) | 154.8 (25.2) | 155.2 (18.3) | 158.7 (23.4) |

| Diastolic BP (mean (SD) mm/Hg) | 85.6 (10.9) | 83.6 (9.9) | 84.4 (9.5) | 78.0 (12.6) | 91.7 (10.3) | 82.4 (14.2) | 83.9 (10.1) | 83.6 (11.7) |

| History | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 9 (4) | 6 (9) | 4 (19) | 14 (17) | 3 (9) | 8 (15) | 24 (36) | 12 (18) |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (2) | 7 (10) | 4 (19) | 26 (32) | 2 (6) | 8 (15) | 16 (24) | 36 (54) |

| Angina | 12 (5) | 16 (23) | 7 (33) | 33 (40) | 3 (9) | 14 (25) | 23 (34) | 46 (69) |

| Hypertension | 54 (22) | 24 (35) | 9 (43) | 27 (33) | 29 (88) | 31 (56) | 38 (57) | 39 (58) |

| Medication taken | ||||||||

| Diuretics | 15 (6) | 20 (29) | 16 (76) | 70 (85) | 33 (100) | 55 (100) | 12 (18) | 26 (39) |

| ACE inhibitors | 12 (5) | 5 (7) | 4 (19) | 39 (48) | 10 (30) | 20 (36) | 19 (28) | 18 (27) |

| ARBs | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 7 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| β-blockers | 14 (6) | 19 (28) | 2 (10) | 9 (11) | 5 (15) | 8 (15) | 17 (25) | 21 (31) |

| Symptoms | ||||||||

| Shortness of breath | 48 (20) | 32 (46) | 16 (76) | 61 (74) | 11 (33) | 34 (62) | 17 (25) | 44 (66) |

| Tired | 70 (29) | 33 (48) | 15 (71) | 62 (75) | 12 (36) | 35 (64) | 27 (40) | 42 (63) |

| Ankle swelling | 38 (16) | 22 (32) | 15 (71) | 41 (50) | 10 (30) | 29 (53) | 22 (33) | 22 (33) |

| New York Heart Association class | ||||||||

| 1 | 200 (83) | 39 (57) | 5 (24) | 22 (27) | 23 (70) | 21 (38) | 57 (78) | 28 (42) |

| 2 | 35 (15) | 23 (33) | 11 (52) | 30 (37) | 7 (21) | 21 (38) | 10 (15) | 29 (43) |

| 3 | 4 (2) | 2 (3) | 3 (14) | 15 (18) | 3 (9) | 8 (15) | 1 (1) | 6 (9) |

| 4 | 1 (0.4) | 5 (7) | 2 (10) | 15 (18) | 0 (0) | 5 (9) | 4 (6) | 4 (6) |

| Ejection fraction | ||||||||

| <40% | 1 (0.4) | 4 (6) | 1 (5) | 20 (24) | 1 (3) | 6 (11) | 1 (1) | 9 (13) |

| 40–49% | 2 (0.8) | 3 (4) | 2 (10) | 18 (22) | 1 (3) | 6 (11) | 3 (4) | 6 (9) |

| ≥50% | 237 (98.7) | 62 (90) | 18 (86) | 44 (54) | 31 (94) | 43 (78) | 63 (94) | 52 (78) |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Definite HF | 0 (0) | 7 (10) | 1 (5) | 35 (43) | 1 (3) | 14 (25) | 0 (0) | 9 (13) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 (0) | 7 (10) | 0 (0) | 23 (28) | 0 (0) | 13 (24) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) |

| Significant valve disease | 0 (0) | 5 (7) | 1 (5) | 9 (11) | 0 (0) | 7 (13) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) |

BP, blood pressure; ECHOES, Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study; HF, heart failure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

The distributions of NT-proBNP in each cohort are given in table 2. The general population had the lowest values with more than 75% below 150 pg/mL. Highest levels were observed in the cohort with a previous label of HF.

Table 2.

Distribution of NT-proBNP in each cohort

| Cohort | N | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| General population | 309 | 70.9 (35.3–130.1) |

| Previous label of HF | 103 | 493.6 (204.3–1341) |

| On diuretics | 88 | 200 (76.1–672.8) |

| At high risk | 134 | 160.1 (64.6–386.3) |

HF, heart failure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

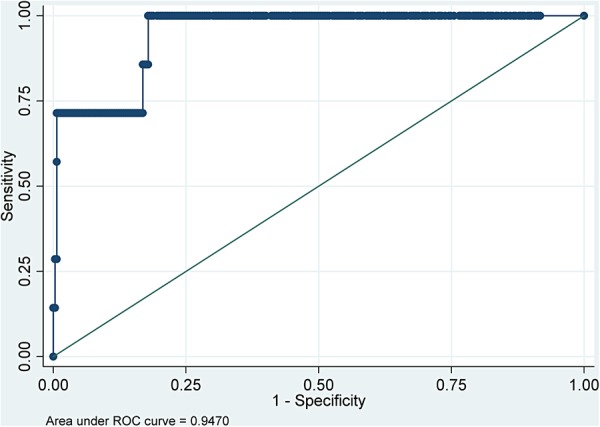

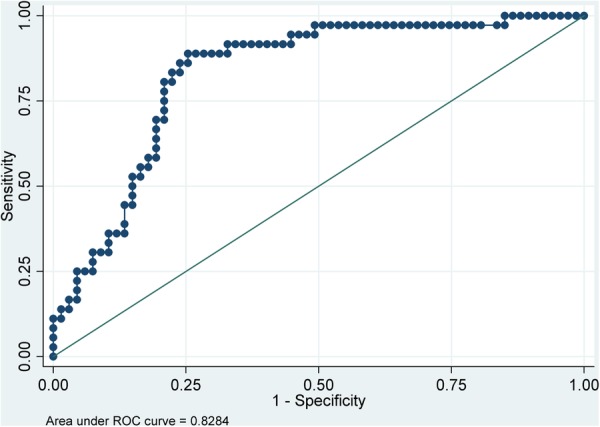

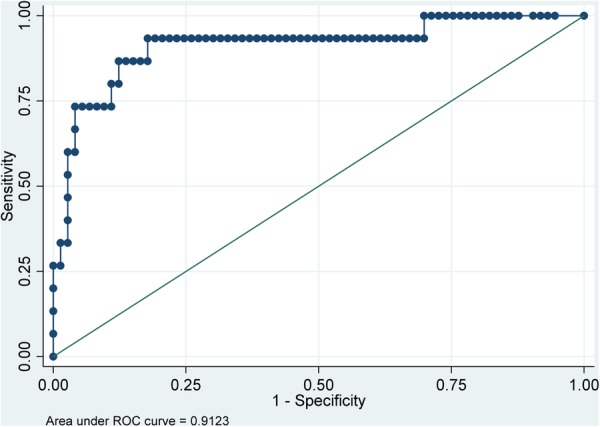

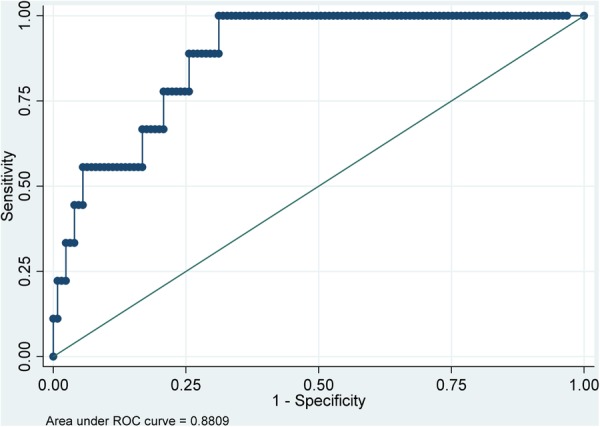

Figures 1–4 show the receiver operating curves for assessing the performance of NT-proBNP in diagnosing HF in each of the cohorts. The AUROC for NT-proBNP levels above 150 pg/mL was 0.95 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.00) for the general population; 0.83 (0.75 to 0.91) for those with previous label of HF; 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) for those on diuretics; and 0.88 (0.80 to 0.97) for those at risk of HF. The cut-off for NT-proBNP at 150 pg/mL had sensitivity of 100% (95% CI 59% to 100%) and specificity of 79.5% (95% CI 74.5% to 83.9%) in identifying HF in the general population sample; 97.2% (85.5% to 99.9%) sensitivity and 29.9% (19.3% to 42.3%) specificity for those with previous label of HF; 93.3% (68.1% to 99.8%) sensitivity and 43.8% (32.2% to 55.9%) specificity for those on diuretics; and 100% (66.4% to 100%) sensitivity and 53.6% (44.5% to 62.6%) specificity for those at high risk. A full summary of performance characteristics, including positive and negative predictive values and accuracy is given in table 3. Other cut-offs were not considered in this analysis due to the high sensitivity and reasonable specificity observed using the chosen cut-off. Overall, a cut-off of 150 pg/mL found 100% of HF cases and 80% of non-HF cases. The percentage of deaths at 10 years with NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL at baseline was 50% in the general population, 86% in HF label group, 71% in the high-risk group and 84% in the diuretics group.

Figure 1 .

Receiver operating characteristic curve to show effectiveness of baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in predicting a diagnosis of heart failure at screening in the general population cohort.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve to show effectiveness of baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in predicting a diagnosis of heart failure at screening in the ‘previous label of heart failure’ cohort.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curve to show effectiveness of baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in predicting a diagnosis of heart failure at screening in the ‘prescribed diuretics’ cohort.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curve to show effectiveness of baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in predicting a diagnosis of heart failure at screening in the ‘high risk’ cohort.

Table 3.

Performance characteristics for NT-proBNP (cut-off 150 pg/mL)

| Cohort | AUROC | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General population | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.00) | 100 (59 to 100) | 79.5 (74.5 to 83.9) | 10.1 (4.2 to 19.8) | 100 (98.5 to 100) | 79.9 (75 to 84.3) |

| Previous label of heart failure | 0.83 (0.75 to 0.91) | 97.2 (85.5 to 99.9) | 29.9 (19.3 to 42.3) | 42.7 (31.8 to 54.1) | 95.2 (76.2 to 99.9) | 53.4 (43.3 to 63.3) |

| On diuretics | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) | 93.3 (68.1 to 99.8) | 43.8 (32.2 to 55.9) | 25.5 (14.7 to 39.0) | 97.0 (84.2 to 99.9) | 52.3 (41.4 to 63.0) |

| High risk | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.97 | 100 (66.4 to 100) | 53.6 (44.5 to 62.6) | 13.4 (6.3 to 24.0) | 100 (94.6 to 100) | 56.7 (47.9 to 65.2) |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating curve; NPV, negative predictive value; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PPV, positive predictive value.

The multiple logistic regression analysis suggests that NT-proBNP≥150 pg/mL is predictive of HF (OR=17.7 (95% CI 4.9 to 63.5)) after allowing for cohort related variables (table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression model to predict HF

| Variable | OR (95% CI*) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Previous label of HF | 3.74 (1.45 to 9.69) | 0.007 |

| On diuretics | 5.26 (1.70 to 16.31) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | 4.91 (1.66 to 14.51) | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 0.39 (0.16 to 0.97) | 0.04 |

| Angina | 1.22 (0.99 to 5.00) | 0.053 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.61 (0.67 to 3.86) | 0.29 |

| NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL | 17.65 (4.91 to 63.48) | <0.001 |

*Bootstrapped estimates.

HF, heart failure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Cause of death

Cardiovascular disease was the main cause of death in each cohort, ranging from 31% (95% CI 20% to 46%) in the general population to 49% (95% CI 37% to 61%) in the high-risk group. The remaining deaths were mainly due to respiratory disease and cancer.

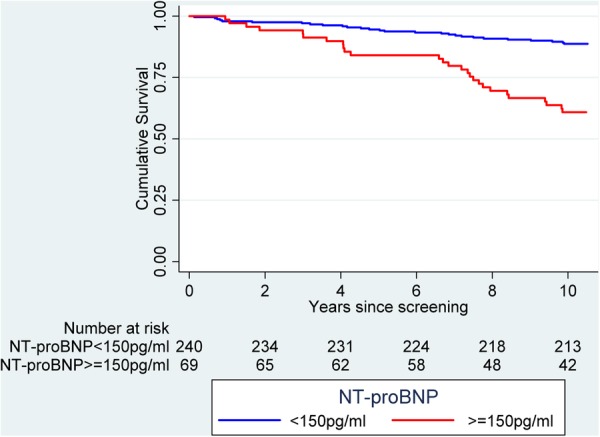

Survival analysis of the general population cohort

There was a statistically significant difference in survival between those who had an NT-proBNP level ≥150 pg/mL and those with an NT-proBNP level <150 pg/mL in the general population sample (log-rank test, χ2=30.4, 1, p<0.0001) as shown in figure 5. Mean survival for those with an NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL was 8.7 years (95% CI 8.0 to 9.4) compared to 9.9 years (95% CI 9.7 to 10.2) for those with an NT-proBNP<150pg/mL. Ten-year survival was 61% (95% CI 48% to 71%) for those with an NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL and 89% (95% CI 84% to 92%) for those with NT-proBNP <150 pg/mL at the time of the initial study.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level and ten year survival for the general population cohort.

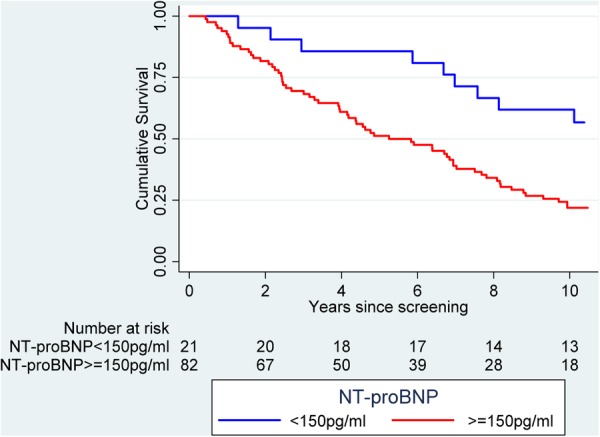

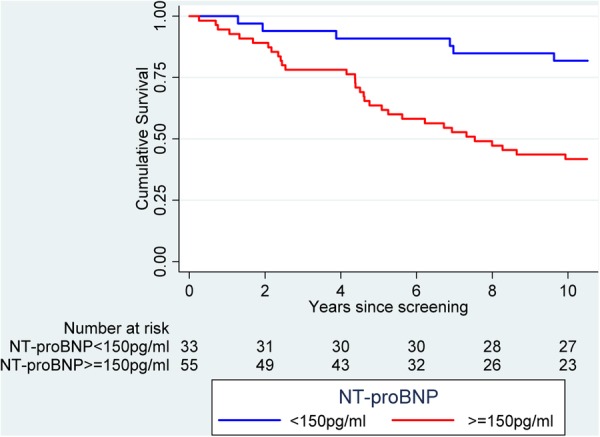

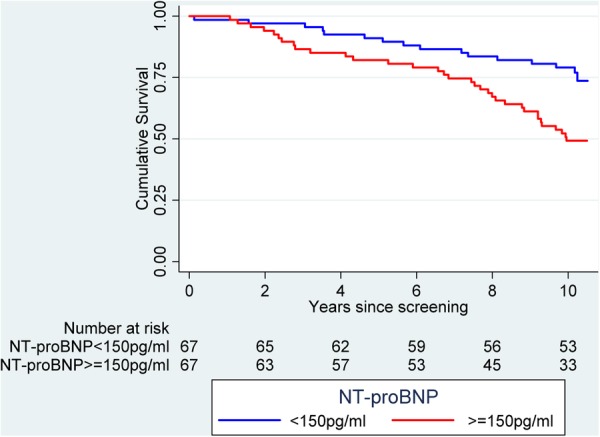

Survival analysis of the other cohorts

Reduced length of survival was also observed for those above the NT-proBNP cut-off when compared with those below the cut-off in each of the other cohorts (p<0.001). Those sampled with a previous label of HF and with NT-proBNP ≥150pg/mL had a mean survival of 5.8 years (95% CI 5.0 to 6.5) compared to 8.4 years (95% CI 7.1 to 9.7) for those below the cut-off (figure 6). The comparative results for those on diuretics (figure 7) were 7.0 years (6.0–7.9) vs 9.5 years (8.7–10.4); and those at high risk (figure 8) 8.3 years (7.6–9.0) versus 9.4 years (8.8–10.0).

Figure 6 .

Kaplan-Meier curve showing N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level and ten year survival for the cohort with a previous label of heart failure.

Figure 7.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level and ten year survival for the diuretic cohort.

Figure 8.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level and 10 year survival for the high risk cohort.

Cox regression analysis of all cohort data

Table 5 shows a cox regression model examining factors associated with mortality using data from all four cohorts. After adjustment for demographic variables and shortness of breath, NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL was found to increase the risk of death by 58% (HR=1.58 (1.09–2.30)).

Table 5.

Cox regression model of factors associated with mortality (including all study cohorts)

| Variable | HR (95% CI*) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.10) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 2.05 (1.43 to 2.95) | <0.001 |

| Previous label of HF | 1.75 (1.17 to 2.57) | 0.007 |

| On diuretics | 0.90 (0.62 to 1.32) | 0.59 |

| Diabetes | 1.08 (0.65 to 1.88) | 0.78 |

| Hypertension | 1.37 (0.99 to 1.90) | 0.06 |

| Angina | 1.04 (0.73 to 1.50) | 0.82 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.18 (0.80 to 1.73) | 0.40 |

| Shortness of breath | 1.64 (1.14 to 2.37) | 0.008 |

| NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL | 1.58 (1.09 to 2.30) | 0.02 |

*Bootstrapped estimates.

HF, heart failure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

In total 594 participants of the ECHOES study took part in the NT-proBNP substudy. Mean survival time for participants from the general population with an NT-proBNP ≥150 pg/mL was over 1 year less than participants with NT-proBNP <150 pg/mL (8.7 vs 9.9 years). The proportion of patients surviving 10 years was significantly lower in the group with an NT-proBNP level ≥150 pg/mL compared to an NT-proBNP level <150pg/mL (61% vs 89%, respectively in the general population). An NT-proBNP level ≥150 pg/mL was strongly predictive of a diagnosis of HF at screening and of death in the next 10 years.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The ECHOES study represents a unique cohort of patients with well phenotyped HF from a community setting. The rigour of clinical assessment means the diagnosis of HF is accurate. All participants’ notes were flagged by ONS to ensure accurate data about date and cause of death, and were sent to the research team. The ONS records reflect the reason for death in the opinion of the attending clinician, as recorded on the death certificate, but the symptoms of HF can be similar to other conditions, particularly respiratory disorders and clinicians can disagree. The study design also did not allow for interim data collection so non-fatal end points, such as hospitalisation, were not explored.

NT-proBNP levels were not recorded in all participants of the ECHOES study however the baseline characteristics of the NT-proBNP substudy were similar to those of the study population as a whole. Only 3% of participants were non-white which may not fully reflect the ethnic diversity of the UK population and NT-proBNP levels may vary depending on ethnicity. Renal function was not recorded in this study therefore we were unable to assess the effect of renal impairment on mortality.13 A cut-off of 150 pg/mL was chosen to represent a raised level of NT-proBNP in the substudy however debate exists around the optimal cut-off level for NT-proBNP.14

The study reports a long-term follow-up of 10 years and over this time the diagnostic criteria and management of HF have changed significantly. The original diagnosis of HF in the ECHOES study was based on the European Society of Cardiology guideline 1995 and this definition has been updated several times since then.15–17 At the time, HF with reduced ejection fraction was the main recognised type of HF and the most common precursor to this was, and remains, ischaemic heart disease. Sixty-nine per cent of the HF-labelled group in this study had a history of angina or MI. In the past 10–15 years, HF with preserved ejection fraction, or HF-PEF, has also been recognised as a distinct clinical and pathological entity. The atrial fibrillation and/or significant valve disease groups (with normal ejection fraction) in the ECHOES study may have partly captured some patients with HFPEF but this group will have largely been excluded. The ECHOES-extension study has rescreened the entire cohort, phenotyping for HF-REF and HF-PEF and will report shortly.

Comparison with existing literature

A study by Wang et al8 investigated the relationship between BNP levels and risk of cardiovascular events or death in 3346 patients from the Framingham cohort who did not have HF at baseline. In total 119 participants died and 79 had a first cardiovascular event during a mean follow-up of 5.2 years. For each 1 SD increment increase in log BNP level, risk of developing HF increased by 77% (p<0.001) and risk of death increased by 27% (p=0.009).

BNP and NT-proBNP levels also increase with HF stage. A study of patients over the age of 45 from the Rochester Epidemiology Study found that mean BNP (rather than NT-proBNP) level was 26 pg/mL in patients without HF, 32 pg/mL in those with risk factors, 53 pg/mL in those asymptomatic participants with structural or functional cardiac abnormalities, 137 pg/mL in participants with HF symptoms and 353 pg/mL for participants with severe HF. Survival declined progressively for each additional stage of disease.18

Another study by Hartmann et al9 investigated the role of baseline NT-proBNP in predicting mortality and hospitalisation in patients with a diagnosis of HF. NT-proBNP levels were recorded in 814 men and 197 women with severe HF defined as breathlessness at rest or on minimal exertion and an ejection fraction of less than 25%. They were followed up for a median time of 159 days (range 1–488 days). A baseline NT-proBNP level above compared to below the median level for the cohort was a strong predictor of all-cause mortality and hospitalisation for HF (relative risk 2.4; 95% CI 1.8 to 3.4; p=0.0001). NT-proBNP has also been found to be an independent predictor of mortality in patients with renal disease.10

Overall, participants labelled with HF in the ECHOES cohort had a better prognosis than some other community-based studies.19 20 This may reflect a lower overall risk in the studied population, the introduction of medication known to improve survival, such as ACE inhibitors or β-blockers, following screening or a referral bias in that patients in the study may have been more likely to be referred for more intensive HF management. A letter was sent to GPs of all study participants with advice on management of participants with a confirmed diagnosis of HF.

Implications for future research and practice

In this substudy, participants with a raised NT-proBNP level were more likely to have a confirmed diagnosis of HF after screening. Natriuretic peptides are already used in clinical practice to determine the likelihood of HF and guide referral for echocardiography however the optimal cut-off level is still unclear.17 21 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline on the management of chronic HF recommends an NT-proBNP of 400 pg/mL is used as the threshold to refer for echocardiography in symptomatic patients, whereas the European Society of Cardiology suggests a threshold level of 125 pg/mL to exclude HF. Fuat et al22 showed that a cut-off of 150 pg/mL had a negative predictive value of 92% in a primary care community HF clinic, again in symptomatic patients. Our data suggest that the current NICE cut-off is too high and that 150 pg/mL is a more reliable threshold for further investigation, especially since our data include asymptomatic as well as symptomatic non-presenting patients.

Importantly, participants in the NT-proBNP substudy with a raised NT-proBNP were also more likely to die sooner than participants with a normal NT-proBNP level. These data confirm the potential for incident NT-proBNP tests to indicate patient prognosis in primary care settings as has been confirmed in hospital settings. Assessment of patients to establish the cause of a raised NT-proBNP level such as HF or renal disease followed by optimal management using evidence-based therapies is crucial to reducing mortality in these high-risk patients.

Finally, these data are the first we are aware of that suggest a possible role for natriuretic peptides in population screening for HF. Given the late diagnosis in many patients and the asymptomatic nature in early stages, this may be an important finding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Michael Davies and Dr Russell Davis for their contribution to the original ECHOES study from which these 10-year follow-up data are derived.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the manuscript. FDRH was the principal investigator and established the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study (ECHOES) cohort. CJT and FDRH designed this study. CJT and AKR undertook statistical analysis. CJT and RI coded the death data.

Funding: The costs for this analysis were partially supported by the NIHR School for Primary Care Research. The National Health Service Research and Development Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke Programme funded the original Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening Study. CT is funded by a Doctoral Research Fellowship from the National Institute for Health Research.

Competing interests: The NT-proBNP assays for the ECHOES study were provided free of charge by Roche Diagnostics, but Roche were not party to the study design, nor any aspect of the analysis, nor to the writeup of this paper. FDRH has received similar indirect research support on other investigator-led heart failure research. FDRH has also received occasional fees or expense reimbursement from Roche in the past.

Ethics approval: The study received full ethical approval from the local research ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The complete database for the ECHOES study is stored securely at the University of Birmingham and available on request. All authors have access to the data.

References

- 1.de Lemos JA, McGuire DK, Drazner MH. B-type natriuretic peptide in cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2003;362:316–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escobar C, Santiago-Ruiz JL, Manzano L. Diagnosis of heart failure in elderly patients: a clinical challenge. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad T, O'Connor C. Therapeutic implications of biomarkers in chronic heart failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013;94:468–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mark DB, Felker GM. B-type natriuretic peptide—a biomarker for all seasons? N Engl J Med 2004;350:718–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowie MR, Struthers AD, Wood DA, et al. Value of natriuretic peptides in assessment of patients with possible new heart failure in primary care. Lancet 1997;350:1347–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mant J, Doust J, Roalfe A, et al. Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of diagnosis of heart failure, with modelling of implications of different diagnostic strategies in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:1–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hobbs FD, Davis RC, Roalfe AK, et al. Reliability of N-terminal proBNP assay in diagnosis of left ventricular systolic dysfunction within representative and high risk populations. Heart 2004;90:866–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med 2004;350:655–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartmann F, Packer M, Coats AJ, et al. Prognostic impact of plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in severe chronic congestive heart failure: a substudy of the Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival (COPERNICUS) trial. Circulation 2004;110:1780–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svensson M, Gorst-Rasmussen A, Schmidt EB, et al. NT-pro-BNP is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin Nephrol 2009;71:380–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies M, Hobbs F, Davis R, et al. Prevalence of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study: a population based study. Lancet 2001;358:439–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor CJ, Roalfe AK, Iles R, et al. Ten-year prognosis of heart failure in the community: follow-up data from the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening (ECHOES) study. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:176–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandimarte F, Vaduganathan M, Mureddu GF, et al. Prognostic implications of renal dysfunction in patients hospitalised with heart failure: data from the last decade of clinical investigations. Heart Fail Rev 2013;18:167–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Januzzi JL, Chen-Tournoux AA, Moe G. Amino-terminal Pro-B-Type natriuretic peptide testing for the diagnosis or exclusion of heart failure in patients with acute symptoms. Am J Cardiol 2008;101(Suppl):29A–38A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guidelines for the diagnosis of heart failure. The task force on heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 1995;16:741–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ; European Society of Cardiology, Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA), European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:933–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ammar KA, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of heart failure stages: application of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association heart failure staging criteria in the community. Circulation 2007;115:1563–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1397–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA 2004;292:344–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic heart failure. Management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. NICE, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuat A, Murphy JJ, Hungin AP, et al. The diagnostic accuracy and utility of a B-type natriuretic peptide test in a community population of patients with suspected heart failure. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:327–33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.