Abstract

Insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) plays an important role as a systemic regulator of metabolism in multicellular organisms. Hyperinsulinemia, a high level of blood insulin, is often associated with impaired physiological conditions such as hypoglycemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes. However, due to the complex pathophysiology of hyperinsulinemia, the causative role of excess insulin/IGF signaling has remained elusive. To investigate the biological effects of a high level of insulin in metabolic homeostasis and physiology, we generated flies overexpressing Drosophila insulin-like peptide 2 (Dilp2), which has the highest potential of promoting tissue growth among the Ilp genes in Drosophila. In this model, a UAS-Dilp2 transgene was overexpressed under control of sd-Gal4 that drives expression predominantly in developing imaginal wing discs. Overexpression of Dilp2 caused semi-lethality, which was partially suppressed by mutations in the insulin receptor (InR) or Akt1, suggesting that dilp2-induced semi-lethality is mediated by the PI3K/Akt1 signaling. We found that dilp2-overexpressing flies exhibited intensive autophagy in fat body cells. Interestingly, the dilp2-induced autophagy as well as the semi-lethality was partially rescued by increasing the protein content relative to glucose in the media. Our results suggest that excess insulin/IGF signaling impairs the physiology of animals, which can be ameliorated by controlling the nutritional balance between proteins and carbohydrates, at least in flies.

Keywords: Drosophila insulin-like peptides, insulin-like growth factor signaling, hyperinsulinemia, growth regulation, autophagy, protein-to-carbohydrate ratio

Introduction

In mammals, the peptide hormone insulin promotes glucose uptake in muscles and adipose tissues, induces cell growth and proliferation, and stimulates glyconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and protein synthesis (Saltiel and Kahn, 2001). The insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signal is evolutionally conserved throughout multicelluar organisms (Skorokhod et al., 1999). In insects, Drosophila has been extensively used as a model system to study insulin signaling, which plays an important role in regulating organ growth and the final size of the organism.

Drosophila possesses eight insulin-like peptides (Dilps), which can activate the Drosophila insulin receptor, InR (Brogiolo et al., 2001). Among the Drosophila insulin-like peptides (Ilps), dilp2 is the most highly expressed and it has the highest potential for promoting tissue growth (Ikeya et al., 2002; Rulifson et al., 2002; Broughton et al., 2005). It has been demonstrated that reduction of dilp2 increases the content of the insect blood sugar, trehalose, in adult flies, suggesting that dilp2 regulates glucose homeostasis in Drosophila as it also does in mammals (Broughton et al., 2008). Furthermore, reduction of dilp2 expression has been shown to increase lifespan, indicating that dilp2 plays an important role in lifespan determination (Broughton et al., 2008).

On the other hand, excess activation of insulin signaling could impair the physiology of organisms. In humans, it has been proposed that increased levels of insulin in the blood is a primary cause of Type 2 diabetes associated with hypertension and cancers (Novosyadlyy and LeRoith, 2010). In fact, hyperinsulinemia, which is an excessive level of insulin in the blood, is often seen in several metabolic diseases, such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus (Samuel and Shulman, 2012). However, the coexistence of hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and other hormonal and metabolic changes in patients with Type 2 diabetes makes it difficult to understand the causative role of excess insulin signaling in the pathophysiology of hyperinsulinemia (Corkey, 2012). Several animal models for hyperinsulinemia have been developed by overexpressing InR or IGFR in some tissues, by the short-time administration of insulin, or by feeding animals a high-sugar diet (Musselman et al., 2011). Although these models have contributed to elucidating the molecular mechanisms that regulate insulin/IGF signaling, how hyperinsulinemia affects animal physiology has remained elusive.

It has been demonstrated that dietary composition also affects physiology and lifespan of individuals. In Drosophila, the balance of protein to carbohydrate intake is one of the critical determinants for lifespan and fecundity (Lee et al., 2008; Skorupa et al., 2008; Lushchak et al., 2012). For example, flies maintained with glucose-rich/protein-poor food generally become obese with age and exhibited a shorten lifespan and vise versa. Although insulin/IGF signaling plays crucial roles in regulation of glucose uptake, how the signal influences the dietary composition-dependent physiological changes is unclear.

To investigate how excess insulin affects insect physiology, we generated transgenic flies with a high level of dilp2 and analyzed their phenotypes. Overexpression of dilp2 increased the body size and caused semi-lethality. These phenotypes were partially suppressed by mutations in the insulin/IGF signaling pathway components, thereby suggesting that hyperactivation of the insulin/IGF signaling is toxic to flies. We found that dilp2-overexpressing flies exhibited intensive autophagy in fat body cells. Interestingly, increasing the protein content relative to glucose in the media partially rescued the dilp2-induced semi-lethality and autophagy. Our results suggest that excess insulin/IGF signaling impairs the physiology of animals, but it can be ameliorated by controlling the nutritional balance between proteins and carbohydrates, at least in flies.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks and media

UAS-dilp2 (Brogiolo et al., 2001), Akt11 (Stocker et al., 2002), and InR304 (Brogiolo et al., 2001) were kindly provided by Dr. E. Hafen. PTENdj189 was a gift from Dr. D. Pan (Gao et al., 2000). TorK17004(Oldham et al., 2000), S6K07064 (Montagne et al., 1999), and M{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH-51D and M{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH-68E (Bischof et al., 2007) were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. Flies were reared at 25°C on a standard cornmeal medium [3.6% neutralized yeast (Asahi Breweries, LTD. Y-4), 8.1% cornmeal, 10% glucose, and 0.7% agar] with propionic acid and n-butyl p-hydroxybenzoate as mold inhibitors, unless otherwise stated. We used different medium for the convenience of preparation. Drosophila Instant Medium (Formula 4-24, Carolina Biological. Supply, Burlington, NC) was used to as a basal medium to prepare media containing different concentration of yeast extracts: 2 g of Drosophila Instant Medium was mixed with 5 ml of Bacto™ Yeast Extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) dissolved in water at four different concentrations (0, 10, 20, and 40 g/L). Standard cornmeal agar medium was used to prepare media containing glucose at four different concentrations (0, 100, 200, and 300 g/L).

Genetic interaction experiments

To facilitate genetic interaction experiments, we generated a stock, sd-Gal4/sd-Gal4; UAS-dilp2/TM6B, tub-Gal80, in which GAL4-dependent expression of dilp2 is repressed by GAL80. The stock is convenient to test the effects of mutations on the phenotype caused by overexpression of dilp2. To make an internal control, we made flies heterozygous for a mutation with a homologous chromosome marked with RFP: second chromosome-linked mutations (TorK17004 and PTENdj189) and third chromosome-linked mutations (Akt11, InR304, and S6K07064) were crossed to M{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH-51D and M{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH-68E, respectively. The F1 progenies (mutations/3xP3-RFP) were crossed to sd-Gal4/sd-Gal4; UAS-dilp2/ TM6B, tub-Gal80 flies. Numbers of resulting progenies (sd-Gal4/+; UAS-dilp2/+ with mutations) and their sibling controls (sd-Gal4/+; UAS-dilp2/+ with 3xP3-RFP) were counted and calculated relative viabilities.

Measurement of body weight and wing size

The adult flies were weighed using an Analytical Semi-Micro Balance (A&D Company, Tokyo, Japan). To measure wing size, the right wings of the adult flies were torn off by using forceps and mounted onto a microscopic slide using a drop of Fly Line Dressing (TIEMCO, Tokyo, Japan), a silicone grease with very low surface tension (Tsuda et al., 2010). The wings were photographed using a MZ APO stereomicroscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a DP50 digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at a constant magnification. The areas of the wings were measured by using ImageJ software (NIH).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from the adult flies was extracted using TRIzol® (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and it was reverse-transcribed using ReverTra Ace® (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Quantitative-PCR reactions were carried out using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan).

Western blot analysis

The adult flies were homogenized in SDS sample buffer (12.5 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.001% bromophenol blue) and boiled for 10 min at 95°C. The samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), the membranes were incubated with a primary antibody in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing Tween-20 (TBST) overnight at 4°C and then with a secondary antibody in TBST for 1 h at 25°C. The signals were detected with an ECL-plus kit (GE Healthcare). As primary antibodies, rabbit anti-phospho-Akt antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), rabbit anti-phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used at dilutions of 1:1000, 1:1000, and 1:5000, respectively. HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology) and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare) were used as secondary antibodies at dilutions of 1:2000 and 1:1000, respectively.

Liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

LC-MS/MS was used to determine the concentrations of glucose, trehalose, glucose metabolites, and free amino acids. Ten female flies were weighted and homogenized with 75% acetonitrile on ice. The homogenates were centrifuged for 10 min at 2400 × g and the supernatant was re-centrifuged for 10 min at 1200 × g. The supernatant was evaporated and dissolved to mobile phase (10 mM DBAA, Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan), in H2O (pH 4.75). After centrifuging at 1200 × g to remove residue, the supernatants were collected and used for metabolome analysis with a Waters LC-QTofMS system composed of LC (Acquity UPLC) and MS (Xevo™ QTofMS) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The metabolites were separated on an Acquity® UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 Å ~ 100 mm, 1.8 μm; Waters). For the carbon metabolites, the columns were equilibrated with 10 mM DBAA (Tokyo Chemical Industry) in H2O (pH 4.75), and the compounds were eluted with an increasing gradient of acetonitrile. The total run time was 20 min. The MS system was equipped with a dual electrospray ionization probe and operated in the negative ion mode with the source temperature at 120°C. For the amino acids, the analytes were separated by a gradient of mobile phase ranging from water containing 0.05% acetic acid to methanol over a 15 min run. The capillary voltage and the cone voltage for electrospray ionization was maintained at 0.7 kV and 15 V for negative mode detection and at 0.7 kV and 13 V for positive mode detection, respectively. The source temperature and the desolvation temperature were set at 120 and 350°C, respectively. Nitrogen was used as both the cone gas (50 l/h) and the desolvation gas (600 l/h) and argon was used as the collision gas. For accurate mass measurement, the mass spectrometer was calibrated with sodium formate solution (range m/z 50–1000) and monitored by the intermittent injection of the lock mass leucine enkephalin ([M + H]+ = 556.2771 m/z and [M − H]− = 554.2615 m/z) in real time. The MS data were analyzed using QuanLynx™ (Waters). The compounds were identified based on their retention time, their m/z ratio, and the MS/MS spectrum of standard reference materials.

Measurement of protein content

The concentration of soluble protein was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. At least three trials were carried out for each genotype.

Triglyceride measurement

Ten adult flies were weighed and homogenized in 1% Triton-X. The homogenates were heated for 10 min at 70°C and stored at −80°C. After thawing on ice, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 14,700 × g at 25°C. The amount of triglycerides (TAG) was determined using a Serum Triglyceride Determination Kit (TR0100; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). All data were normalized with soluble protein contents in homogenates. At least three samples were used to determine the average amount of triglycerides.

Autophagy staining

The fat bodies were dissected from the early third larvae in PBS and incubated with LysoTracker® Red DND-99 (Molecular Probes®, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) at a 1:1000 dilution in PBS for 1 min at room temperature. After a brief wash in PBS, the sample was observed under a Nikon C1 laser scanning confocal microscope.

Results and discussion

Overexpression of dilp2 reduced the egg-to-adult viability of the flies

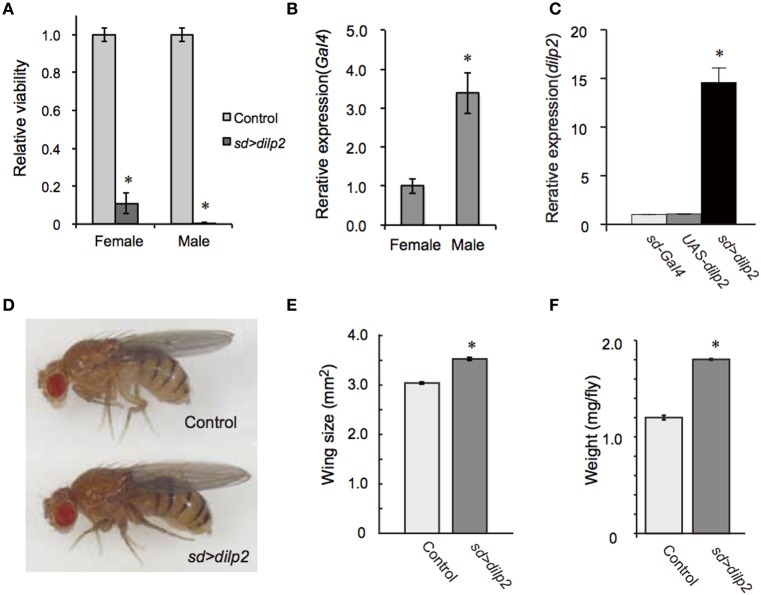

To generate a transgenic fly model of hyperinsulinemia, we overexpressed dilp2 which is known to promote tissue growth in Drosophila. We found that flies show high lethality when dilp2 was overexpressed ubiquitously using actin5c-Gal4, suggesting that high levels of Dilp2 are toxic to flies. However, the reason for this lethality was not understood. An alternative driver, which gives a milder phenotype, would be useful to investigate the developmental toxicity associated with dilp2 overexpression. We tested several Gal4 lines, and found that sd-Gal4, which predominantly expresses Gal4 in developing imaginal wing discs, was an appropriate driver. When sd-Gal4 was crossed with UAS-dilp2, the number of progenies from the cross was significantly less than the number of progenies obtained from the parental lines, thereby suggesting that overexpression of dilp2 was toxic to flies. To more quantitatively determine the viability, the number of progenies were compared between the dilp2-overexpressing flies and their siblings bearing the M{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH-68E chromosome expressing red fluorescence protein (RFP) under the control of an artificial 3xP3 promoter (Bischof et al., 2007). Female flies homozygous for sd-Gal4 were crossed to UAS-dilp2M{{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH-68E heterozygous males and the number of adult flies was counted. In theory, one half of the progeny inherit and express UAS-dilp2 under control of sd-Gal4, and the other half, serving as an internal control, carry an RFP-bearing chromosome. The number of dilp2-overexpressing flies was markedly reduced compared to that of the control flies (Figure 1A). Both sexes are semi-lethal, but the effects were more severe in the males than in the females. This is likely due to the dosage compensation mechanism, since sd-Gal4 is an X-linked transgene, which drives expression of dilp2 two-times higher in males (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Overexpression of dilp2 increases body size and causes semi-lethality. Relative viability of dilp2-overexpressing flies (A). Flies homozygous for sd-Gal4 were crossed with UAS-dilp2/3xP3-RFP males, and the number of flies expressing RFP served as an internal control; those not expressing RFP are expressing dilp2. Expression level of Gal4 in sd-Gal4 male is much higher than that of sd-Gal4 female (B). Overexpression of dilp2 caused semi-lethality for both males and females. The relative expression level of dilp2 mRNA in the dilp2-overexpressing flies (sd > dilp2) and the parental lines (sd-Gal4 and UAS-dilp2) served as controls and was determined by real-time RT-PCR (C). dilp2-overexpressing flies have increased body size (D), increased wing area by 17% (E), and increased weight by 50% (F). Student t-test was performed to analyze statistical significance. *p < 0.01.

Using female flies that survived to adult stage, we determined the expression level of dilp2 in females. Quantitative real-time PCR revealed that the levels of dilp2 mRNA in the adult female increased 16-times higher than that of the control, suggesting that overexpression of dilp2 occurred and is toxic to fly development (Figure 1C).

We also noticed that the body size of the sd > dilp2 flies that survived to the adult stage was larger than that of the control (Figure 1D). To compare the body size more precisely, wing size was measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. The wing size of the sd > dilp2 flies was increased by 17% compared to the wing size of the control flies (Figure 1E). In addition, the body weight of the dilp2-overexpressing flies increased by 50% compared to the control flies (Figure 1F). These results indicated that overexpression of dilp2 caused semi-lethality, but promoted growth for the survivors.

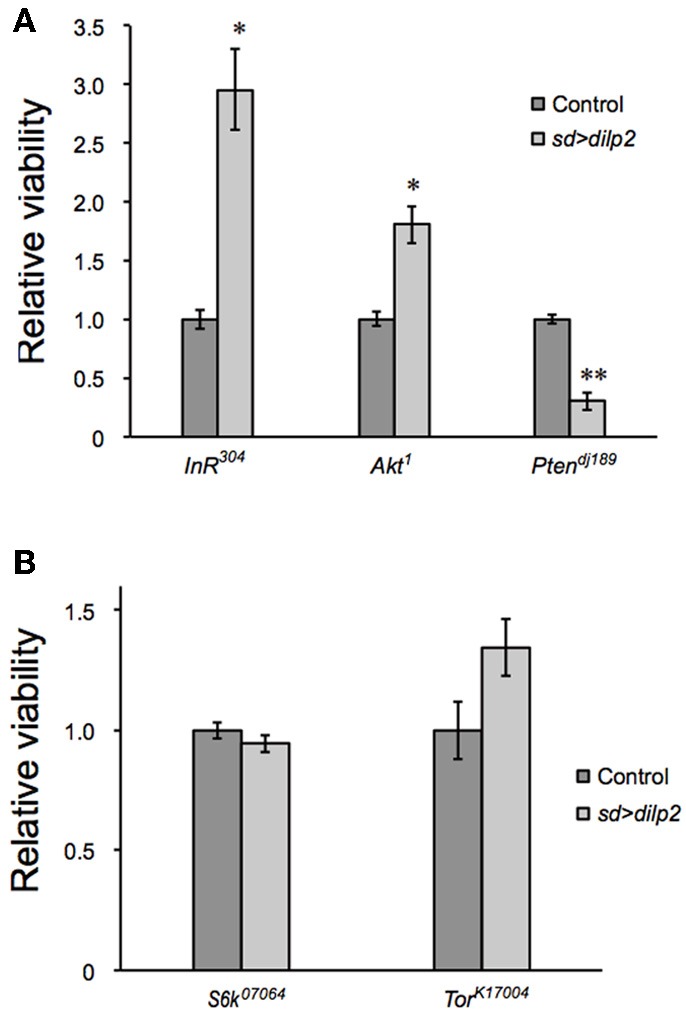

The PI3K/AKt1pathway mediates dilp2-induced semi-lethality

dilp2 stimulates the PI3K/Akt1 pathway through insulin receptor (InR) activation. Western blotting analysis revealed that the active form of Akt1 was significantly increased in the dilp2-overexpressing flies compared to the control, indicating that overexpression of dilp2 indeed activates the PI3K/Akt1 signaling (Figure 2 upper panel). To further confirm this, we investigated whether the mutations in the pathway components had an effect on dilp2-induced semi-lethality. We found that, for both males and females, the heterozygous flies that carry a loss-of-function mutation in InR or Akt1 showed higher levels of viability compared to the control flies (Figure 3A). On the other hand, a loss-of-function mutation in Ptne, a negative regulator of PI3K, further reduced the viability of dilp2-overexpressing flies (Figure 3A). These results suggest that dilp2-induced semi-lethality is mediated by the PI3K/Akt1 signaling. Overexpression of IlpP2 also activated the Tor/S6K signaling, a downstream signal component of the PI3K/Akt1 signaling, since the level of phosphorylated S6K was increased (Figure 2 middle panel). However, interestingly, the loss-of-function mutations in Tor or S6K had no effect on the reduced viability of the dilp2-overexpressing flies, suggesting that the Tor/S6K signaling is irrelevant to the semi-lethality or the single copies of mutations were not sufficient to suppress the dilp2-induced semi-lethality (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

dilp2-overexpression activates Akt1 and S6 kinase (S6K). The amount of phosphorylated Akt1 and S6K were analyzed by western blots. α-tubulin was used as a loading control.

Figure 3.

Genetic manipulation of InR/Akt1/PI3K modifies the dilp2-induced lethality. Relative viability of the sd > dilp2 flies was determined in combination with loss of function mutations in InR, Akt1, or PI3K, which are components of the insulin/IGF signaling pathway. dilp2- induced semi-lethality was markedly improved by reduction of InR or Akt1, but enhanced by reduction of PTEN (A). Relative viability of the sd > dilp2 flies in combination with loss-of-function mutations in Tor and S6K (B). The Tor/S6K pathway may not contribute to mediating the semi- lethality of dilp2-overexpressing flies. Student t-test was performed to analyze statistical significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Glucose and lipid metabolism in dilp2 overexpressing flies

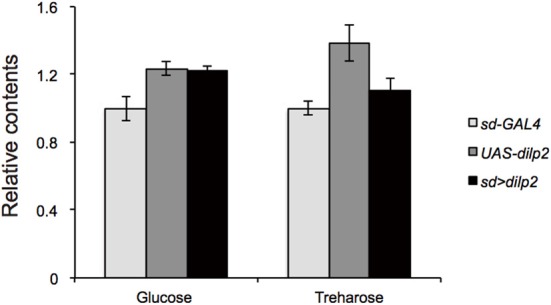

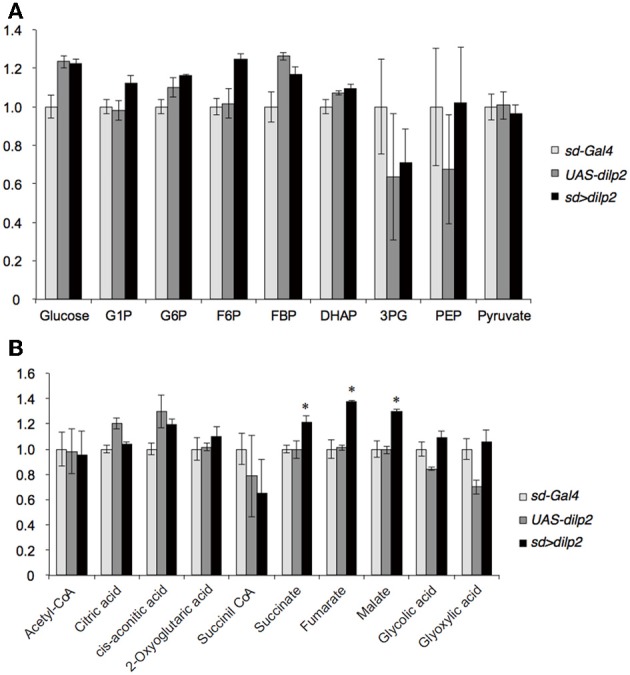

Next, we examined whether overexpression of dilp2 disrupts glucose homeostasis and metabolism. We first measured the concentration of glucose and trehalose, the major blood sugars in insects. There was no significant difference in the concentration of these sugars between the dilp2-overexpressing flies (sd > dilp2) and the parental lines (sd-Gal4 or UAS-dilp2) as the controls (Figure 4). We also measured the amounts of glycolysis and TCA cycle metabolites using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with ion-pair reagents (Figures 5A,B). There was no significant difference in the amounts of glycolytic metabolites between the dilp2-overexpressing flies (sd > dilp2) and the parental lines (sd-Gal4 or UAS-dilp2) as the controls. These results suggest that glucose homeostasis itself was unaffected by overexpression of dilp2. For the TCA cycle metabolites, the amount of succinate, fumarate, and malate was slightly increased in the dilp2-overexpressing flies. Since fumarate and malate have been shown to extend lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans (Edwards et al., 2013), overexpression of dilp2 might have affected the energy metabolism associated with lifespan determination.

Figure 4.

Trehalose and glucose content in dilp2-overexpressing flies. Relative amount of glucose and trehalose in the sd > dilp2 flies was calculated based on the values of a parental line (sd-Gal4) and indicated as the mean ± SE of at least three samples with a minimum of five flies per group. There was no significant difference in the amount of these sugars.

Figure 5.

Glucose metabolism in dilp2-overexpressing flies. Glycolysis (A) and TCA cycle (B) metabolites were analyzed by using LC-MS/MS in negative mode. Relative amounts of metabolites in the sd > dilp2 flies were calculated based on the values of the parental lines (sd- Gal4) and shown as the mean ±S.E of at least three samples with a minimum of five flies per group. G6P: glucose 6-phosphate;F6P: fructose 6-phosphate; F1,6BP: fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; 2/3-PG: 2/3-phophoglycerate; PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate. Student t-test was performed to analyze statistical significance. *p < 0.05

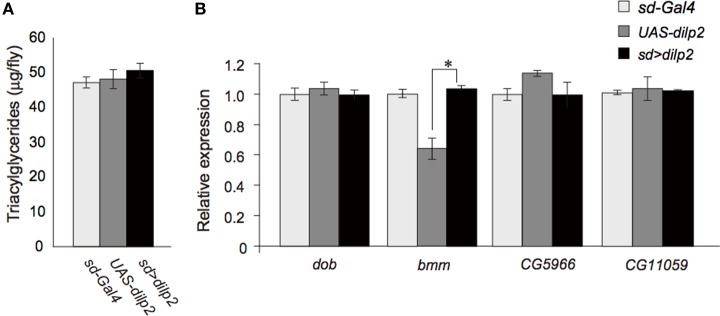

Insulin/IGF signaling might down-regulate lipid catabolism via regulation of lipases (Xu et al., 2012). Thus, we next measured the lipid content in the dilp2-overexpressing flies and the control parental lines. There was no significant difference in the level of triacylglycerol, the most abundant of the storage lipids (Figure 6A). In addition, quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that the expression levels of four major Drosophila lipases, doppelganger von brummer (dob), brummer (bmm), CG5966, and CG11055 (Gronke et al., 2005) were not altered in the dilp2-overexpressing flies (Figure 6B). Expression level of bmm in the parental line, UAS-dilp2 was significantly lower than those of another parental line sd-Gal4 and of their progeny sd > dilp2. There might be unknown mechanisms that downregulate bmm expression in the background of UAS-dilp2 line. We also compared the expression levels of bmm between sd > dilp2 and sd-Gal4, 3xP3-RFP flies, and found that there was no significant change in bmm expression level when dilp2 was overexpressed (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Lipid metabolism in dilp2-overexpressing flies. Comparison of TAG levels between the dilp2-overexpressing flies and the parental lines as controls (A). Relative mRNA levels of four major genes involved in lipid catabolism in Drosophila, doppelganger von brummer (dob), brummer (bmm), CG5966, and CG11055 (B). Results are shown as the mean ± SE of at least three experiments. ANOVA with Tukeys HSD was performed to analyze statistical significance. *p < 0.01.

These results suggested that overexpression of dilp2 does not affect the lipid storage and catabolism in flies.

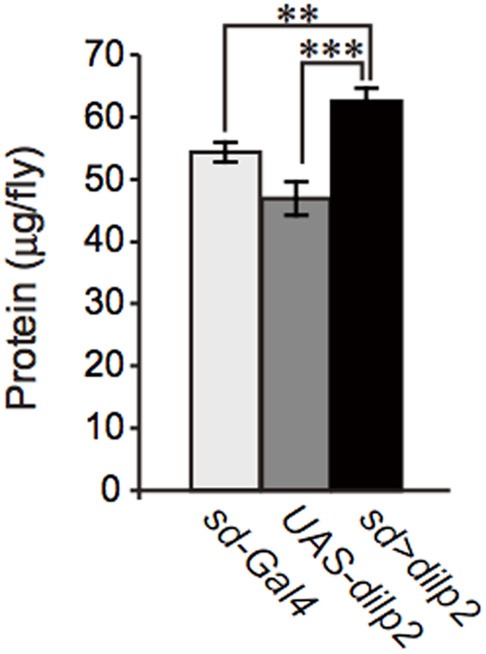

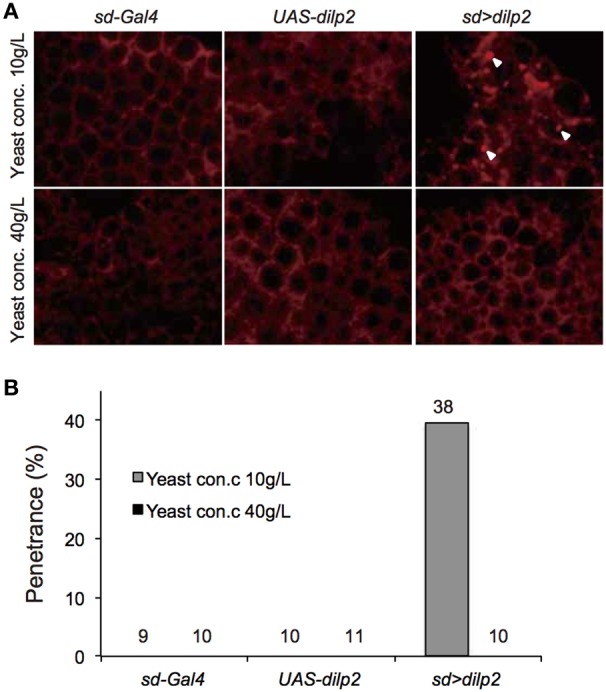

Nutrient dependent effects of dilp2-overexpression

We also examined the protein content per fly and found that the dilp2-overexpressing flies contain more protein than the parental control lines (sd-Gal4 and UAS-dilp2), thereby suggesting that protein synthesis is elevated in sd > dilp2 flies (Figure 7). Interestingly, the viability of the dilp2-overexpressing flies increased depending on the concentration of the yeast extracts in the media (Figure 8A; Spearman's rank correlation coefficient = 0.79, p < 0.0003). The relative viability of the dilp2-overexpressing female flies was only 2% in the medium without yeast extract, whereas it was 16.6% in the medium containing 40 g/L yeast extract. In addition, increasing protein content in the media significantly increased the mean wing area of the dilp2-overexpressing flies, while it did not affect the wing size of the control flies (Figure 9). These results indicated that to support their development the dilp2-overexpressing flies require more protein as a nutrient than the control flies. It is possible that a shortage of protein sources occurs in the dilp2-overexpressing flies. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether autophagy occurs in the fat bodies dissected from the early third instar larvae. A large number of autophagy positive-cells were observed in the fat bodies of the dilp2-overexpressing flies While no autophagy positive-cell was found in the fat bodies of the control flies, (Figure 10). Increasing protein content in the media significantly suppressed the dilp2-mediated autophagy, suggesting that the dilp2-overexpressing flies were suffering from an insufficiency of protein sources. Namely, the shortage of protein sources could be one of the reasons for dilp2-induced semi-lethality.

Figure 7.

Protein content in dilp2-overexpressing flies. The protein content was significantly increased in the dilp2- overexpressing flies (sd > dilp2) compared to the parental lines (sd-Gal4 and UAS-dilp2) as controls. Results are shown as the mean ± SE of at least three experiments. Student t-test was performed to analyze statistical significance. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 8.

Viability of dilp2-overexpressing flies depends on nutritional conditions. Dilp2-overexpressing flies (sd > dilp2) were reared on media supplemented with various concentrations of yeast extract (A) or glucose (B). Relative viability of the dilp2-overexpressing flies (sd > dilp2) for each medium was calculated based on the number of control siblings.

Figure 9.

Effects of protein-rich media on the wing size of dilp2-overexpressing flies. dilp2-overexpressing flies (sd > dilp2) were reared on media supplemented with various concentrations of yeast extract and their wing sizes were compared with those of the internal control flies. Mean wing area was positively correlated with the concentration of yeast extract in the media. Student t-test was performed to analyze statistical significance. *p < 0.05.

Figure 10.

Intensive autophagy in dilp2-overexpressing flies. Fat bodies were dissected from early third instar larvae overexpressing dilp2 (sd > dilp2) and stained with LysoTracker Red DND-99 (A). When the flies were reared on standard media containing 10 g yeast/L, strong punctate signals (arrowheads), corresponding to autophagy were observed in the sd > dilp2 flies (upper right panel) but not in the parental lines (sd-Gal4 or UAS-dilp2) as the controls (upper left and middle panels). Autophagy was not detectable in the sd > dilp2 flies when they were reared on protein-rich media containing 40 g yeast/L (lower panels). The penetrance (frequency) of ectopic autophagy in sd > dilp2 flies (B). Numbers of samples observed were indicated above each bar.

Overexpression of dilp2 might cause chronic deficiency of amino acids. To examine this possibility, we quantified free amino acids in the sd > dilp2 and the sd > RFP flies using an LC-MS/MS. Although the relative amount of threonine and phenylalanine were significantly different between the two groups, all changes were subtle and are unlikely to affect the viability (Figure 11). These results suggested that survivors of the dilp2-overexpressing flies were maintaining normal amino acid homeostasis probably though inducing ectopic autophagy. However, considering the semi-lethality of the animals, those failed to maintain amino acid homeostasis might have died earlier during development.

Figure 11.

Amino acid content in dilp2-overexpressing flies. A free amino acids in the adult flies were quantified by using an LC-MS/MS in positive mode. Relative amounts of each amino acid in sd > dilp2 flies were calculated based on those in the sd > RFP flies as a control, and are shown as the mean ± SE of at least three experiments with a minimum of five flies per group. Student t-test was performed to analyze statistical significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

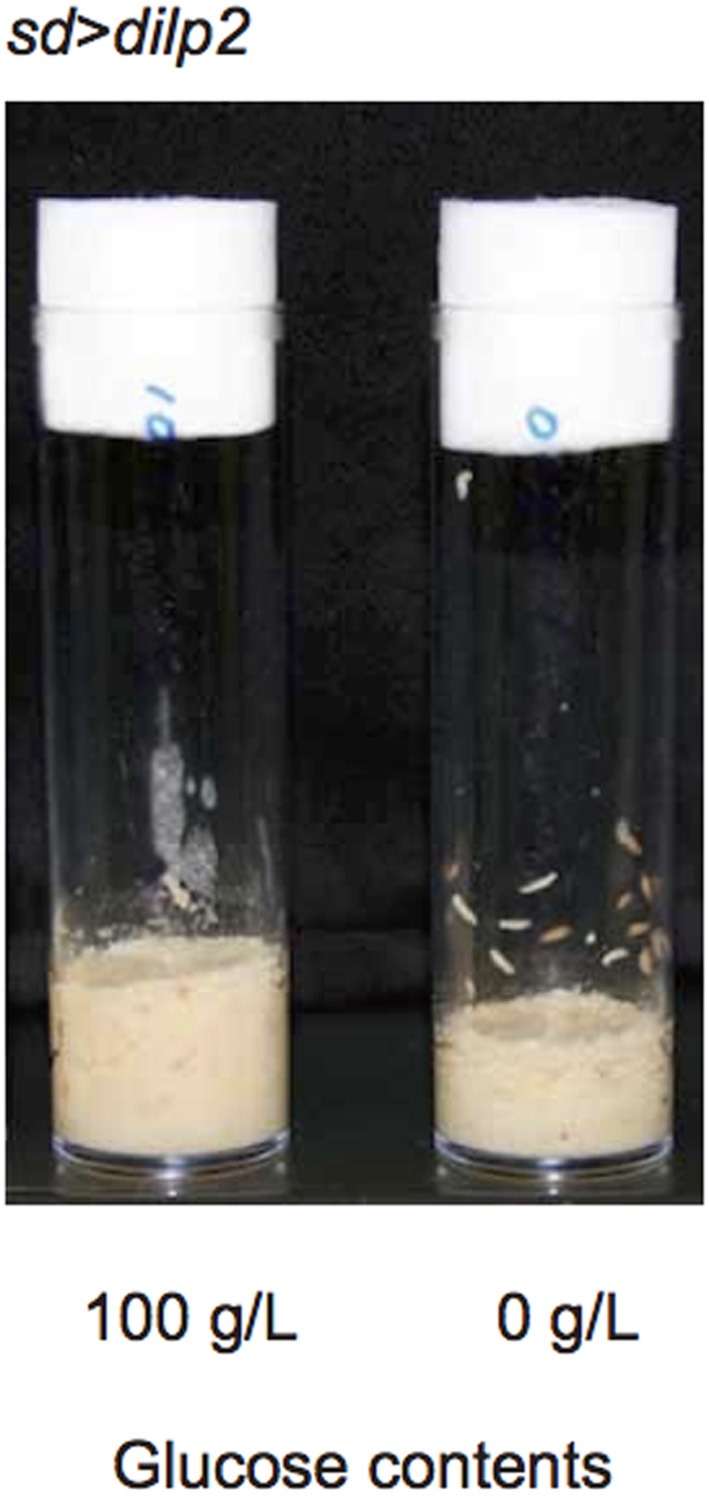

A protein-to-carbohydrate ratio is critical for the survival of dilp2-overexpressing flies

The occurrence of autophagy in dilp2-overexpressing flies suggested that the animals were suffered from the shortage of amino acids. It has been demonstrated that a protein-to-carbohydrate ratio can affect the lifespan and the fecundity of flies (Lee et al., 2008). It is possible that overexpression of dilp2 affected the optimal ratio of these nutrients for the flies' development. Thus, we examined whether the glucose content of the fly food could modify the dilp2-induced semi-lethality. Increasing glucose concentration in the media significantly reduced the viability of the dilp2-overexpressing flies, indicating that overexpression of dilp2 enhances the susceptibility to glucose. On the other hand, decreasing glucose content in the media significantly improved the viability of the dilp2-overexpressing flies (Figure 8B Spearman's rank correlation coefficient = −0.86, p < 0.0001). Interestingly, the dilp2-overexpressing flies kept in a glucose-reduced condition grew significantly faster than those reared on standard media (Figure 12). The mean (±SE) durations of egg-to-early pupa was 106.3 ± 1.3 and 82.6 ± 1.3 h, with control media and glucose-deprived media, respectively (Student t-test: p < 0.001). These results strongly suggested that a high-protein low-carbohydrate diet is optimal for the viability of dilp2-overexpressing flies.

Figure 12.

dilp2-overexpressing flies develop faster in media with reduced glucose. Overexpression of dilp2 retarded development of flies when they were reared on the standard media containing 100 g/L glucose (left). However, flies develop faster when kept in glucose-deprived media (right). The mean (±SE) durations of egg-to-early pupa was 106.3 ± 1.3 and 82.6 ± 1.3 h, with control media and glucose-deprived media, respectively (Student t-test: p < 0.001).

In this study, we demonstrated that overexpression of dilp2 severely decreases the egg-to-adult viability of flies and induced a high frequency of ectopic autophagy in fat bodies of early third instar larvae. As in mammalian cells, nutrient starvation induces autophagy through inhibition of Tor activity in Drosophila (Scott et al., 2004). However, the dilp2-overexpression-dependent autophagy does not seem to be regulated by the down-regulation of Tor, since S6K, a downstream target of Tor, was strongly activated (Figure 2). Activated S6K may execute autophagy, since expression of activated S6K increases starvation-induced autophagy in the absence of Tor in Drosophila (Scott et al., 2004). It is possible that a hyperactivation of S6K in the dilp2-overexpressing flies might contribute to promoting autophagy. In isolated rat hepatocytes, some amino acids inhibit induction of autophagy in an mTor (mammalian Tor) independent manner (Kanazawa et al., 2004). Therefore, a shortage of protein sources may induce autophagy directly. The dilp2-overexpression-dependent autophagy was reverted by a high-protein diet, suggesting that the nutritional condition is critical for survival of dilp2-overexpressing flies. It has been demonstrated that flies cultured on nutrient-rich food contain a significantly high level of secreted dilp2 compared to flies cultured on nutrient-deprived food, indicating that flies can sense the nutrient availability and modulate their insulin secretion accordingly (Geminard et al., 2009). Our results suggest that excess insulin/IGF signaling impairs the physiology of animals, which can be ameliorated by controlling the nutritional balance between proteins and carbohydrates, at least in flies.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, Kyoto, Japan and the Bloomington Stock Center for providing the fly stocks. This work was supported by a special grant from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government to Toshiro Aigaki.

References

- Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K. (2007). An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3312–3317 10.1073/pnas.0611511104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogiolo W., Stocker H., Ikeya T., Rintelen F., Fernandez R., Hafen E. (2001). An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr. Biol. 11, 213–221 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00068-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton S., Alic N., Slack C., Bass T., Ikeya T., Vinti G., et al. (2008). Reduction of DILP2 in Drosophila triages a metabolic phenotype from lifespan revealing redundancy and compensation among DILPs. PLoS ONE 3:e3721 10.1371/journal.pone.0003721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton S. J., Piper M. D., Ikeya T., Bass T. M., Jacobson J., Driege Y., et al. (2005). Longer lifespan, altered metabolism, and stress resistance in Drosophila from ablation of cells making insulin-like ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3105–3110 10.1073/pnas.0405775102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkey B. E. (2012). Banting lecture 2011: hyperinsulinemia: cause or consequence? Diabetes 61, 4–13 10.2337/db11-1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C. B., Copes N., Brito A. G., Canfield J., Bradshaw P. C. (2013). Malate and fumarate extend lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 8:e58345 10.1371/journal.pone.0058345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Neufeld T. P., Pan D. (2000). Drosophila PTEN regulates cell growth and proliferation through PI3K-dependent and -independent pathways. Dev. Biol. 221, 404–418 10.1006/dbio.2000.9680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geminard C., Rulifson E. J., Leopold P. (2009). Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 10, 199–207 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronke S., Mildner A., Fellert S., Tennagels N., Petry S., Muller G., et al. (2005). Brummer lipase is an evolutionary conserved fat storage regulator in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 1, 323–330 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya T., Galic M., Belawat P., Nairz K., Hafen E. (2002). Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 12, 1293–1300 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01043-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa T., Taneike I., Akaishi R., Yoshizawa F., Furuya N., Fujimura S., et al. (2004). Amino acids and insulin control autophagic proteolysis through different signaling pathways in relation to mTOR in isolated rat hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8452–8459 10.1074/jbc.M306337200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. P., Simpson S. J., Clissold F. J., Brooks R., Ballard J. W., Taylor P. W., et al. (2008). Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: new insights from nutritional geometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2498–2503 10.1073/pnas.0710787105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lushchak O. V., Gospodaryov D. V., Rovenko B. M., Glovyak A. D., Yurkevych I. S., Klyuba V. P., et al. (2012). Balance between macronutrients affects life span and functional senescence in fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 67, 118–125 10.1093/gerona/glr184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagne J., Stewart M. J., Stocker H., Hafen E., Kozma S. C., Thomas G. (1999). Drosophila S6 kinase: a regulator of cell size. Science 285, 2126–2129 10.1126/science.285.5436.2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman L. P., Fink J. L., Narzinski K., Ramachandran P. V., Hathiramani S. S., Cagan R. L., et al. (2011). A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Dis. Model. Mech. 4, 842–849 10.1242/dmm.007948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novosyadlyy R., LeRoith D. (2010). Hyperinsulinemia and type 2 diabetes: impact on cancer. Cell Cycle 9, 1449–1450 10.4161/cc.9.8.11512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham S., Montagne J., Radimerski T., Thomas G., Hafen E. (2000). Genetic and biochemical characterization of dTOR, the Drosophila homolog of the target of rapamycin. Genes Dev. 14, 2689–2694 10.1101/gad.845700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulifson E. J., Kim S. K., Nusse R. (2002). Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science 296, 1118–1120 10.1126/science.1070058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel A. R., Kahn C. R. (2001). Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 414, 799–806 10.1038/414799a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel V. T., Shulman G. I. (2012). Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell 148, 852–871 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R. C., Schuldiner O., Neufeld T. P. (2004). Role and regulation of starvation-induced autophagy in the Drosophila fat body. Dev. Cell 7, 167–178 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorokhod A., Gamulin V., Gundacker D., Kavsan V., Muller I. M., Muller W. E. (1999). Origin of insulin receptor-like tyrosine kinases in marine sponges. Biol. Bull. 197, 198–206 10.2307/1542615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorupa D. A., Dervisefendic A., Zwiener J., Pletcher S. D. (2008). Dietary composition specifies consumption, obesity, and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell 7, 478–490 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00400.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker H., Andjelkovic M., Oldham S., Laffargue M., Wymann M. P., Hemmings B. A., et al. (2002). Living with lethal PIP3 levels: viability of flies lacking PTEN restored by a PH domain mutation in Akt/PKB. Science 295, 2088–2091 10.1126/science.1068094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M., Kobayashi T., Matsuo T., Aigaki T. (2010). Insulin-degrading enzyme antagonizes insulin-dependent tissue growth and Abeta-induced neurotoxicity in Drosophila. FEBS Lett. 584, 2916–2920 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Gopalacharyulu P., Seppanen-Laakso T., Ruskeepaa A. L., Aye C. C., Carson B. P., et al. (2012). Insulin signaling regulates fatty acid catabolism at the level of CoA activation. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002478 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]