Abstract

Background Burgeoning global mental health endeavors have renewed debates about cultural applicability of psychiatric categories. This study’s goal is to review strengths and limitations of literature comparing psychiatric categories with cultural concepts of distress (CCD) such as cultural syndromes, culture-bound syndromes, and idioms of distress.

Methods The Systematic Assessment of Quality in Observational Research (SAQOR) was adapted based on cultural psychiatry principles to develop a Cultural Psychiatry Epidemiology version (SAQOR-CPE), which was used to rate quality of quantitative studies comparing CCD and psychiatric categories. A meta-analysis was performed for each psychiatric category.

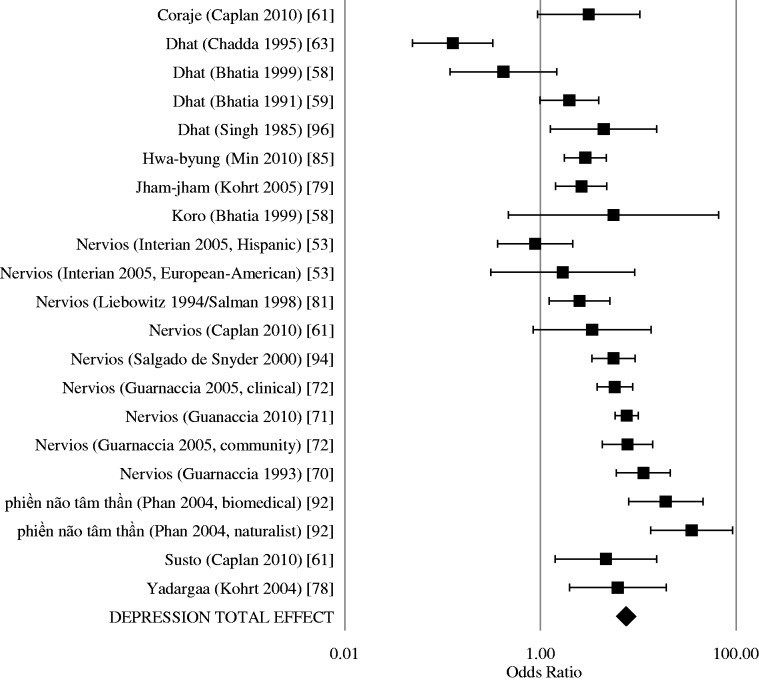

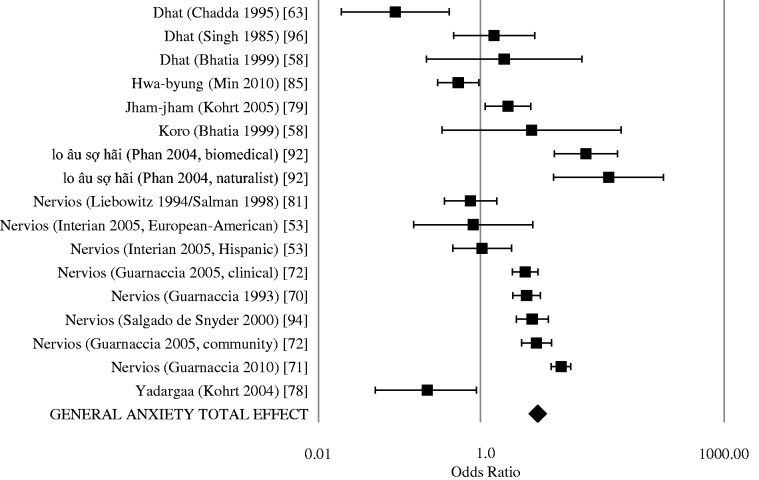

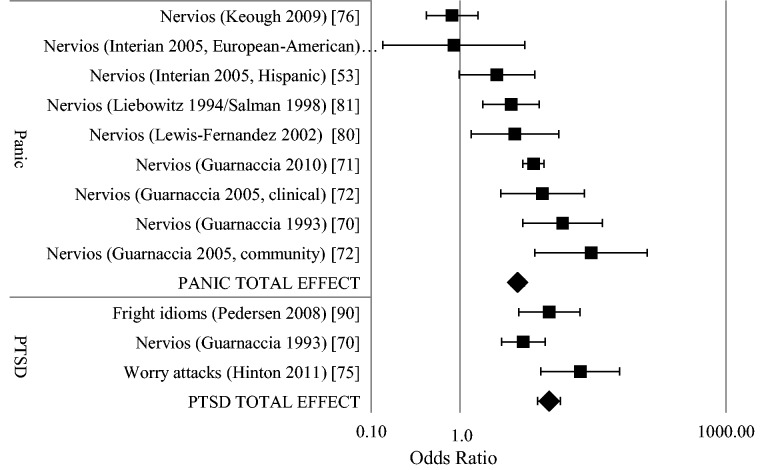

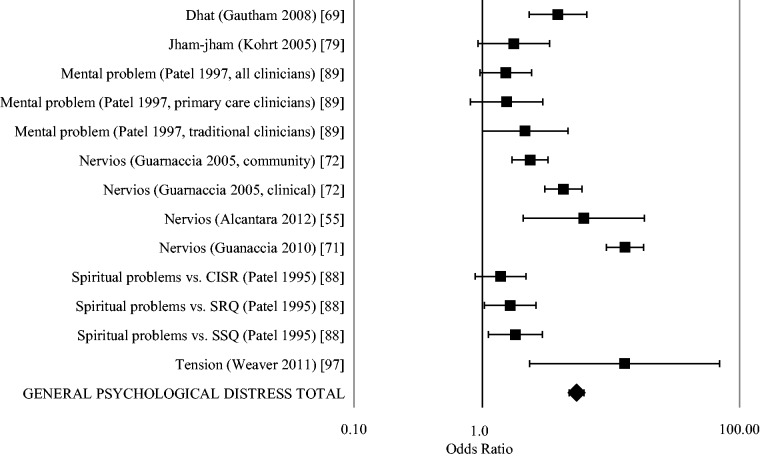

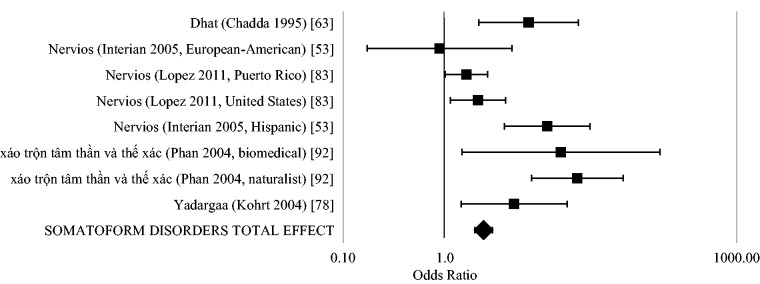

Results Forty-five studies met inclusion criteria, with 18 782 unique participants. Primary objectives of the studies included comparing CCD and psychiatric disorders (51%), assessing risk factors for CCD (18%) and instrument validation (16%). Only 27% of studies met SAQOR-CPE criteria for medium quality, with the remainder low or very low quality. Only 29% of studies employed representative samples, 53% used validated outcome measures, 44% included function assessments and 44% controlled for confounding. Meta-analyses for anxiety, depression, PTSD and somatization revealed high heterogeneity (I2 > 75%). Only general psychological distress had low heterogeneity (I2 = 8%) with a summary effect odds ratio of 5.39 (95% CI 4.71-6.17). Associations between CCD and psychiatric disorders were influenced by methodological issues, such as validation designs (β = 16.27, 95%CI 12.75-19.79) and use of CCD multi-item checklists (β = 6.10, 95%CI 1.89-10.31). Higher quality studies demonstrated weaker associations of CCD and psychiatric disorders.

Conclusions Cultural concepts of distress are not inherently unamenable to epidemiological study. However, poor study quality impedes conceptual advancement and service application. With improved study design and reporting using guidelines such as the SAQOR-CPE, CCD research can enhance detection of mental health problems, reduce cultural biases in diagnostic criteria and increase cultural salience of intervention trial outcomes.

Keywords: Culture, developing countries, epidemiologic methods, global mental health, mental disorders, meta-analysis

Introduction

In 1904 Emile Kraepelin initiated the field of comparative psychiatry (vergleichende Psychiatrie) through investigation of dementia praecox in Java, and he later documented psychiatric presentations among Native Americans, African Americans and Latin Americans.1 A century later, active debate continues regarding the role of culture in mental disorders and the cross-cultural applicability of biomedical psychiatric diagnoses.2 Methodological limitations in cross-cultural psychiatric epidemiology have been cited as a primary reason why cultural differences have not translated into re-evaluating psychiatric concepts and treatment practices.3,4 For example, cultural differences in schizophrenia outcomes, which have been identified in three successive studies,5–10 have done little to alter conceptualizations or treatment of the disorder, and this is in part due to methodological problems in the cross-national studies.3,11–13 These studies, along with World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Surveys,14 are typified by application of Western culturally developed biomedical psychiatric diagnoses that lack inclusion of cultural concepts of distress (CCD). To date there have not been large-scale cross-national global mental health epidemiology studies incorporating CCD. To address this gap in the research, a review of the literature on CCD was undertaken to examine the types of studies conducted, the methodological approaches and the association of CCD with psychiatric disorders. The goal is to identify best practices in cross-cultural psychiatric epidemiology to improve research on CCD and encourage application to mental health services.

The term ‘cultural concept of distress’ is a new addition to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) series with the publication of DSM-5: ‘Cultural Concepts of Distress refers to ways that cultural groups experience, understand, and communicate suffering, behavioral problems, or troubling thoughts and emotions’.15 The term is a recent advance in the history of attempts to categorize psychological distress with demonstrable cultural influence that lacks one-to-one unity with biomedical psychiatric diagnoses (see Box 1 for exemplar CCD.) The attempt to label CCD dates back to Pow Meng Yap’s research in Hong Kong in the 1950–60s.16 Yap employed the term ‘culture-bound depersonalization syndrome’ to describe koro, a ‘state of acute anxiety with partial depersonalization’ associated with fear of the penis retracting into the body. The term ‘culture-bound syndrome’ has been used in cross-cultural psychiatry since and was included in the DSM-IV.17

Box 1. Examples of Cultural Concepts of Distress (CCD).

Nervios-related conditions—In the Americas, nervios (nerves)-related conditions among Latino populations are the most commonly described CCD.126 Nervios starts with ‘a persistent idea that ‘is stuck to one's mind’ (‘idea pegada a la mente’), and these ‘particular idea[s] … invade the mind and accumulate … Affected individuals think so much about the ideas that the ideas ‘get stuck' to the brain’.94 Among Mexicans with nervios, 40% endorsed having an idea stuck to their mind. In nervios, feelings of humiliation lead to the slow deterioration of one’s mind, nerves and spirit and ‘may even cause death, if adequate help is not timely received’.127 The spectrum of nervios follows a gradient of behavioural control.80 One end of the spectrum begins with socially acceptable nervousness: ser una persona nerviosa (being a nervous person). Padecer de los nervios (suffering from nerves) is more serious. Ataques de nervios (attacks of nerves) have greater severity and are characterized by social stressors triggering loss of behavioural control, dissociation, violent acts toward oneself or others, anger and somatic distress.128 Severe nerve illness can lead to loco (madness). Nervios (nerves), padecer de nervios (suffering from nerves) and ataques de nervios (nerve attacks) have been studied in clinical samples in large-scale Latino representative community studies in Puerto Rico and the USA.70,71 Ataques de nervios overlap with some symptoms of panic attacks and panic disorder. However, they are distinct from panic attacks because of the centrality of interpersonal disputes in triggering episodes, dissociative features and an experience of relief among some individuals after an ataque.80,132 These nervios-related conditions are associated with unexplained neurological complaints, physical health problems and functional impairment independent of association with psychiatric disorders.

Dhat—Dhat syndrome has been studied in South Asia and is rooted in Ayurvedic traditions about bodily production of semen as representing an end-product of energy demanding metabolism: 40 meals create 1 drop of blood, 40 drops of blood create 1 drop of semen.43 Dhat is recognized by a whitish discharge in urine assumed to be semen. Although sexually transmitted infections may be a source of such discharge, dhat sufferers do not appear to have greater frequency of STIs.69 Dhat sufferers do appear to have high rates of psychosexual dysfunction including premature ejaculation and erectile dysfunction: 42% of men with dhat had premature ejaculation in one study in India.64 Young males appear to be the most frequent demographic group presenting with dhat. Dhat has corollaries in Chinese medicine and European and American history with accounts of weakness, physical illness and mental illness related to the loss of semen.43,77

Koro—Koro was one of the first cultural concepts discussed in transcultural psychiatry literature.16 Koro epidemics have been reported in South Asia, and case reports have been reported throughout the world. Fear of the penis retracting into the body among men and retraction of breasts among women is a central feature. The majority of reported cases are among men.

Brain fag—Brain fag has been studied for a half-century in Western Africa. The condition is characterized by distress from thinking too much, with students being a vulnerable population.86 The experience includes headaches and an experience of a worm crawling in the head. This is similar to the Nigerian cultural concept of distress, ode ori:84 the disorder ode ori (hunter in the head) affects the brain under the anterior fontanelle where the iye (senses) control mental functions through okun (strings) that project throughout the body and provide direct linkages among the brain, eyes, ears and heart.

Khyal attacks and ‘wind’-related illnesses—The substance qi, (cf chi, chi’i, khí, khii, rlung, khyal) is associated with wind flow and wind balance. Wind-related illnesses are commonly described in East Asian populations including Tibetans, Cambodians, Vietnamese, Chinese and Mongolians.73,77,78,129,130 Shenjing shuairuo (neurological weakness, neurasthenia), studied by Kleinman in the 1970s and 80s, is associated with weakness, fatigue and social distress mediated by an alteration in qi.77 Yadargaa, a nervous fatigue described in Mongolia, is similarly viewed as an alteration in khii flow and balance.78 In the Vietnamese CCD ‘hit by wind’, shifts in ambient temperature, especially gusts of cold air, are associated with a range of physical complaints, traumatic memories, thinking too much, epilepsy and stroke.73 Similarly, in China, nerve weakness is associated with a fear of cold because it worsens nerve weakness.77 Among Cambodians, the wind-like substance khyal can be experienced as an attack associated with palpitations, asphyxia and dizziness.130 Khyal attacks can lead to rupture of blood vessels in the neck and spinning of the brain.

Kufungisisa—The experience of thinking too much (Shona: kufungisisa) is associated with general psychological distress and common mental disorders in Zimbabwe. Thinking too much is considered both a symptom of distress and a cause of other physical and psychological health problems: thinking too much can cause pain and feelings of physical pressure on the heart.54

Hwa-Byung—Heat and fire are important elements in East Asian ethnopsychology. The condition hwa-byung (fire illness resulting from chronic accumulated anger) in Korea occurs when haan (a mixture of sorrow, regret, hatred, revenge and perseverance) builds up to create a pushing sensation in the chest, resulting in the inability to appropriately control one’s anger.85 Hwa-byung affects middle-aged women in Korea who have experienced years of interpersonal conflict, typically in the context of an abusive marital relationship.

However, the term culture-bound syndrome has been associated with numerous limitations: findings of similar patterns of distress in disparate cultural settings, lack of cohesive symptom presentation characterizing a syndrome, and wide diversity in aetiological attributions, vulnerability groups and symptoms that influence cultural labels.18–22 Moreover, the combination of medical anthropology research, which documents the social construction of psychiatric disorders,23 with innovations in gene-by-environment and social neuroscience research, which illustrate that culture and biology are not neatly divisible categories,24–28 demonstrates that all psychological distress is culture bound. To acknowledge this, the DSM-5 includes text that ‘all forms of distress are locally shaped, including the DSM disorders’.15 Due to dissatisfaction with the term culture-bound syndrome, researchers have proposed other labels such as ‘idioms of distress’, ‘popular category of distress’, ‘cultural syndrome’ and ‘explanatory model’.29–33 The term ‘cultural concept of distress’ is an attempt to aggregate these different concepts without implying cultural exclusivity.

There has been a tension in cultural psychiatry about comparing CCD with psychiatric disorders. Because CCD often incorporate culturally salient aetiological models, vulnerability expectations, wide-ranging associated symptoms and a mixture of lay and local professional attributions systems, comparison with psychiatric diagnoses has been criticized as forcing homogeneity onto CCD and losing key aspects of aetiology and vulnerability that are not incorporated in most psychiatric diagnoses.20,21,34 However, there is a growing body of epidemiology literature comparing CCD with psychiatric disorders for a variety of goals, such as validating psychiatric disorders against CCD, identifying vulnerable groups based on CCD status and identifying forms of distress and impairment not captured by psychiatric disorders.

The goal of this review is to explore the methodological approaches of these epidemiological studies of CCD and psychiatric disorders, to identify limitations in the approaches and best practices for future work. We sought to develop specific criteria for evaluating epidemiological studies based on cultural psychiatry principles. With the expansion of global mental health research and scaling up of services,35–38 it is an ideal time to evaluate if and how CCD can be incorporated into community and clinical epidemiology to reduce suffering. Our review is divided into the following sections: identification of studies comparing CCD and psychiatric disorders; description of study objectives and methods including ranking epidemiological quality of these studies; examining summary effect sizes and sources of heterogeneity when comparing CCD and psychiatric disorders; and concluding with recommendations for incorporating CCD in global mental health research and services.

Methods

Informational sources

To identify literature on CCD we searched MEDLINE/PubMed, applying the following keywords: ‘culture-bound’ or ‘culture bound’ or ‘idiom of distress’ or ‘idioms of distress’. To assure inclusion of popularly studied CCD, we combined the above search with a search of CCD listed in the DSM-5 glossary: ‘nervios’ or ‘dhat’ or ‘khyal’ or ‘kufungisisa’ or ‘maladi moun’ or ‘shenjing shuairou’ or ‘susto’ or ‘taijin kyofusho’). We limited psychiatric outcomes to common mental disorders (operationalized here as depression, anxiety-related conditions including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and panic disorder, and somatization-related conditions) because of their significant burden of disease, the breadth of research on CCD and common mental disorders, and feasibility of assessing common mental disorders through self-report. In contrast, psychosis-related conditions have shown poor reliability and low detection through self-report cross-culturally.39,40 In our preliminary searches for substance use disorders, eating disorders and developmental disorders, we identified a limited number of studies precluding synthesis of findings. The psychiatric disorder search terms thus included the following: ‘depression’ or ‘depression, postpartum’ or ‘PTSD’ or ‘stress disorders, post-traumatic’ or ‘fatigue syndrome, chronic’ or ‘fatigue’ or ‘anxiety disorders’ or ‘anxiety’ or ‘panic disorder’ or ‘panic attack’ or ‘somatoform disorders’ or ‘somatic complaints’. Searches were limited to English-language peer-reviewed journal publications. In addition, reference sections of previous reviews on culture-bound syndromes were searched,41–48 and reference sections of articles identified in the search were used to locate additional articles. The initial searches was performed in November 2012 and repeated for new references in March 2013 and September 2013.

Data collection

To extract relevant data, all studies identified through searches were read and evaluated for inclusion by the first author. Inclusion criteria comprised English language, prevalence data for a psychiatric category, prevalence data for a CCD, odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for association of CCD and psychiatric category or data presented in a manner enabling construction of a two-by-two comparison of psychiatric classification and CCD. Exclusion criteria were case studies and articles lacking original quantitative data. Extracted data included world region, country, study population (including current country of residence for refugee and immigrant populations), researcher label for CCD (e.g. idiom of distress, culture-bound syndrome, cultural syndrome, cultural somatic symptom), language of term, English translation of term, research objective of the study, sample size, sample description, sample origin (clinical, community or school), age group of sample, representative vs convenience or other sample, inclusion and description of control or comparison group, symptom/syndrome description, assessment method for CCD (self-labelling with single-item term, labelling based on a multi-item self-report instrument score, labelling by healthcare provider including traditional healers and clinical providers, labelling from key informant in community), symptom severity assessment, type of symptoms (subjective self-report, externally observable or mixed), CCD prevalence (lifetime, current or unclear), age of onset, duration of current episode, psychiatric diagnostic instrument, administration format of psychiatric instrument (e.g. clinician administered, researcher administered, self-report), validation of instrument in study population, assessment of functioning and impairment, aetiology/perceived cause of CCD, vulnerability factors and risk group for CCD, protective factors against CCD, inclusion of follow-up assessment, percentage lost to follow-up, reasons lost to follow-up, current or prior treatment status, description of study treatment, assessment of psychiatric comorbidities, assessment of biological comorbidities and potential confounds.

Quality assessment

To assess quality, we chose the Systematic Assessment of Quality in Observational Research (SAQOR), which has been developed for assessing quality in observational studies49 and has been used to rate global mental health research conducted across cultural settings.50 SAQOR includes six domains: Sample, Control/Comparison Group, Quality of Exposure/Outcome Measurements, Follow-Up, Distorting Influences and Reporting Data. Each domain contains multiple criteria. For this study, the results section describes modification of SAQOR to develop a version for Cultural Psychiatry Epidemiology (SAQOR-CPE).

Meta-analyses

Odds ratios were extracted or calculated from quantitative studies to determine the likelihood of a specific psychiatric category given the presence of a specific CCD. Two-by-two tables were constructed for all quantitative papers that included data for categorical outcomes of CCD (yes vs no) and psychiatric categories (yes vs no). If studies only included mean scores on symptom scales without providing information on categorical cut-offs, these studies were not included in the meta-analysis. In the two-by-two tables, CCD were considered the independent variable and psychiatric categories were considered the dependent variable.

Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for all studies in the meta-analysis. If a study contained an empty field in the two-by-two table, then individual study outcomes (OR, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV) were not calculated; however, the participants were included in the meta-analysis summary calculations. Sensitivity was calculated as the proportion of persons positive for both the CCD and the psychiatric category, among all persons with CCD. Specificity was calculated as the proportion of persons negative for the CCD and negative for the psychiatric category, among all persons negative for the CCD. Positive predictive value was calculated as the proportion of participants positive for both the CCD and psychiatric category, among all participants positive for the psychiatric category. Negative predictive value was calculated as the proportion of participants negative for both the CCD and the psychiatric category, among all persons negative for the psychiatric category.

Heterogeneity for summary effect sizes was calculated with the Q statistic. The statistic was calculated by summing the squared deviations of each study’s effect estimated from the overall effect estimate; each study was weighted by its inverse variance.51 I2 is another measure of heterogeneity calculated by dividing the difference of the Q statistic and its degrees of freedom by the Q statistic and multiplying this by 100.51 Low values (e.g. <25%) suggest low heterogeneity whereas I2 >75% suggests high heterogeneity with study characteristics and methods influencing the associations.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to assess the influence of study design on effect sizes. GEE is one method that can account for the clustering of multiple comparisons within a single study.52 The odds ratio for each study was used as the dependent variable. Independent variables included world region (Americas, Africa, Asia), researcher label (‘culture-bound …’, ‘idiom …’, ‘popular …’, other ‘… syndrome’ and other label), study objective (compare CCD and psychiatric disorder, instrument validation study, assessment of risk factors for psychological distress, and other), sample size (<100, 100–499 and ≥500 participants) recruitment site (clinical, community or school-based settings), representativeness of sample (representative sample vs all other recruitment forms), CCD type (four groups were created based on greatest number of participants: nervios-related studies, 10 820 participants; dhat studies, 863 participants; hwa-byung studies, 3087 participants; and all other cultural concepts of distress, 4012 participants), CCD-self report (participant endorsed CCD vs studies in which the CCD was attributed to the participant by the researcher, a clinician, or a key informant), assessment method for CCD [categorized into four groups: (i) self-report single item binary categorical endorsement (e.g. yes vs no for ‘Have you ever had an ataque de nervios?’); (ii) self-report multi-symptom instrument score (e.g. mean scale above a cut-off for number of symptoms to meet criteria as a proxy for ataques de nervios, such as symptoms of blinding, fainting and paralysis with symptoms beginning after a troubling experience53); (iii) clinical diagnosis (e.g. clinician making a diagnosis of dhat or hwa-byung based on specific clinical guidelines); or (iv) other third party labelling (e.g. binary categorical label of CCD provided by someone other than participant or clinician; this was usually done by key informants in the community or parents)], prevalence of CCD (lifetime, current/point or unclear), psychiatric categories (classified in five groups: general psychological distress, all anxiety disorders, mood disorders, somatoform disorders and other disorders), controlling for comorbidity (control through inclusion/exclusion criteria or through statistical analysis vs no control for comorbidity) and SAQOR-CPE overall ranking score (very low quality, low quality, medium quality, or high quality). Only analyses with OR outcomes were entered into the GEE. This led to inclusion of 79 comparisons drawn from 26 studies because some studies had multiple comparisons.

Results

Study characteristics

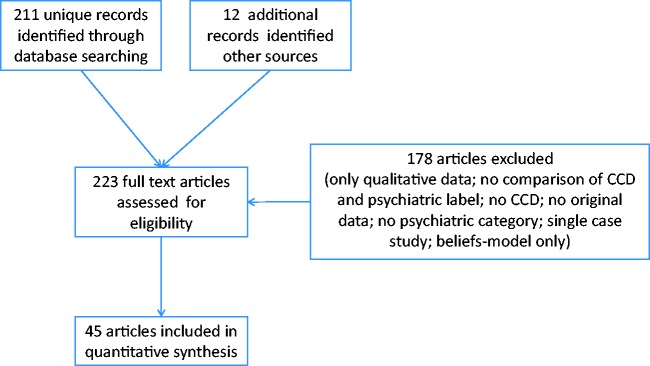

Through the search terms, 211 citations were identified; 12 studies were added from reviews and references lists. Of the total of 223 studies evaluated, 4553–97 included quantitative data on both cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric categories (see Figure 1). Ten studies were conducted in Africa, 18 in the Americas and 17 in Asia (see Table 1a, b, c). The most common CCD were nervios-related conditions, comprising 30% of studies. Nine studies (20%) included children, and the remainder only had adult participants. Studies with participants under 18 years of age were predominantly nervios-related conditions, as well as dhat among adolescent boys. Sixteen (35%) of the studies used the label ‘culture-bound’; nine studies (20%) used ‘idiom of distress’; and 23 studies had comparison of CCD with psychiatric disorders as a primary objective. For eight studies, the primary goal was to evaluate association with a risk factor or vulnerable group. Seven studies had instrument adaptation and validation as the primary goal.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing selection of studies for inclusion in systematic review of cultural concepts of distress (CCD) and psychiatric disorders

Table 1a.

Studies conducted in Africa, meeting inclusion criteria for comparison of cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric categories

| Reference | Rasmussen 201193 | Bass 200856 | Makanjuola 198784 | Ola 201186 | Betancourt 200957 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Chad | Democratic Republic of Congo | Nigeria | Nigeria | Uganda |

| Cultural concept of distress | Hozun (deep sadness), majnun (madness) | Maladi ya souci (syndrome of worry) | Ode-ori (hunter in the head) | Brain fag | Ma lwor (anxiety), kwo maraca (conduct disorder), par (mood disorder), two tam (mood disorder), kumu (‘holding one’s cheek in the hand’—mood disorder) |

| Terminology | Idioms of distress | Local syndrome | Culture-bound disorder | Culture-bound syndrome; indigenous psychopathologies | Local syndrome |

| Research objective | Create a culturally-appropriate measure of distress and evaluate psychometric properties of factor structure and external criterion validity | Determine existence of post-partum depression syndrome; adapt and validate instruments | Identify chief complaints and psychiatric symptoms among patients with a culture-bound syndrome | Factoral validation and reliability of brain fag scale | Evaluating reliability and validity of mental health measure |

| Recruitment | Community | Clinical | Clinical | School | Community |

| Sample | Adult: 848 Darfuris in refugee camp | Adult: 133 women attending maternity clinic identified by key informants | Adult: 30 psychiatric patients | Child: 234 students age 11-20 years | Child: 166 war-affected youth in internal displacement camp in northern Uganda |

| Assessment method | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Single-item key informant and self-report | Traditional healer | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Single-item key informant, parent and self-report |

| Prevalence | Unclear | Unclear | Current | Unclear | Unclear |

| Comparison group | Unclear—no information regarding participants without hozun or majnun, only mean scale scores | Yes—sample included key-informant negative cases and women not endorsing syndrome | No—all patients had ode ori labels | Unclear—no information of participants with no brain fag, only mean BFSS scores provided | Yes —sample included KI-negative, parent-report negative, and self-report negative cases |

| Psychiatric categories | Depression, PTSD | Depression, post-partum depression | All major psychiatric categories | Anxiety | Anxiety, depression, conduct problems |

| Instruments, validation | BSI, PCL-C, not validated | EPDS, HSCL, not validated | PSE, no validation information provided | BFSS, STAI validated in Nigeria | APAI, locally developed scale |

| Functioning | WHO-DAS | Local syndromes | Not reported | Peer relationships | Not reported |

| Reference | Ertl 201068 | Bolton 200460 | Abas 199754 | Patel 199588 | Patel 199789 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Uganda | Uganda | Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe |

| Cultural concept of distress | Spirit possession | Yo'kwekyawa (local depression syndrome) | Kusuwisia (deep sadness); kufungisisa (thinking too much) | Spiritual illness: chivanhu, mudzimu, mamhepo, zvishri | Mental problems |

| Terminology | Indigenous expressions of psychological distress | Local syndrome | Explanatory model | Spiritual distress | Indigenous concept of psychosocial distress |

| Research objective | Validate PTSD Instrument | Assess prevalence of depression using local instruments | Assess prevalence of common mental disorders and elicit explanatory models | Evaluate frequency of spiritual models of illness and association with mental disorders | Evaluate relationship between structured psychiatric diagnosis and primary care (traditional and biomedical) provider identification |

| Recruitment | Community | Community | Community | Clinical | Clinical |

| Sample | Child: 504 war-affected youth in Northern Uganda | Adult: 67 adults identified by key informants and self as suffering from syndrome | Adult: 172 women from townships | Adult: 302 primary care attendees | Adult: 302 primary care attendees |

| Assessment method | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Single-item key informant and self-report | Single-item self-report | Clinician and self-report multi-symptom ratings | Clinician attribution (primary care and traditional healer) |

| Prevalence | Unclear | Unclear | Current | Current | Current |

| Comparison group | Unclear —only SPS mean scores provided | Yes—key informant and self-rating positive and negative cases | No—explanatory models not assessed among PSE negative participants | Yes—half of sample did not endorse spiritual aetiology | Yes—participants not classified by primary care worker or healer as having a mental problem |

| Psychiatric categories | Depression, PTSD | Depression | Psychological distress | General psychological distress | General psychological distress |

| Instruments, validation | HSCL, PDS, SPS, CAPS not validated | Lay interview with DSM-IV MDD criteria, not validated | PSE, SSMD has validation psychometrics | CISR, SSQ, SRQ, transcultural equivalence information provided | SSQ, CISR transcultural equivalence information provided |

| Functioning | Local scale | Local scale | Not reported | Not reported | WHO Quality of Life |

Table 1b.

Studies conducted in the Americas, meeting inclusion criteria for comparison of cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric categories

| Reference | Salgado de Snyder 200094 | Pedersen 200890 | Guarnaccia 199370 | Guarnaccia 200572 | Lopez 201183 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Mexico | Peru | Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico and USA |

| Cultural concept of distress | Nervios (nerves) | Llaki (grief), susto (fright), piensa-mientuwan (worrying memories), tutal piensamientuwan (excess of worrying memories) | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) |

| Terminology | Culturally-interpreted syndrome | Culture-bound trauma-related disorders; local idioms of distress | Popular category of distress | Cultural syndrome | Cultural idiom of distress |

| Research objective | Prevalence, comorbidity with mood and anxiety disorders, and associated symptoms | Map indigenous construction of emotions in response to political violence | Association with disaster and social characteristics | Prevalence and psychiatric correlates among children | Association between ataques and somatic complaints among Puerto Rican youth |

| Recruitment | Community, representative | Community, only persons with high GHQ and HSCL scores | Community, representative | Clinical and community, representative | Community, representative |

| Sample | Adult: 942 community residents | Adult: 144 screened from community | Adult: 912 community sample | Child: 1892 community and 761 clinical | Child: 1138 community sample |

| Assessment method | Single-item self-report (nervios ever vs never) | Single-item self-report (idioms currently yes vs no) | Single-item self-report (ataque de nervios ever vs never) | Single-item parent and self-report (ataque de nervios ever vs never) | Single-item parent and self-report (ataque de nervios ever vs never) |

| Prevalence | Lifetime | Point prevalence | Lifetime | Lifetime | Lifetime |

| Comparison group | Yes—adults not endorsing nervios | Yes—participants denying fright idioms | Yes—participants denying ataque de nervios episodes | Yes—participants denying ataque de nervios episodes | Yes—participants without parent or self-report of ataque de nervios |

| Psychiatric categories | Anxiety, depression | Anxiety, depression, PTSD | All major psychiatric categories | All major psychiatric categories | Somatic complaints (headache) |

| Instruments, validation | CIDI, validated in Spanish | GHQ and HSCL not validated for this population | DIS, validated Puerto Rican version | DISC, validated Puerto Rican version | DISC, validated Puerto Rican version |

| Functioning | Not reported | Not reported | DIS | GAS | Assessed ‘limited activities’ |

| Reference | Guarnaccia 201071 | Interian 20051,31 | Keough 200976 | Lewis-Fernandez 200280 | Lewis-Fernandez 20101,32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | USA | USA | USA | USA |

| Cultural concept of distress | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) |

| Terminology | Idiom of distress | Culturally sanctioned expression of distress | Culture-bound syndrome | Popular syndrome | Cultural idioms of distress |

| Research objective | Evaluate ataque de nervios as marker of social and psychiatric vulnerability | Evaluate the association of unexplained neurological symptoms with ataques | Determine prevalence of ataque-related symptoms across cultural groups | Evaluate phenomenological differences among ataque, panic attacks and panic disorder | To evaluate association among PTSD, dissociation and cultural idioms of distress |

| Recruitment | Community, representative | Clinical | School | Clinical | Clinical |

| Sample | Adult: 2554 Latino Americans | Adult: 95 Hispanic patients and 32 European American patients | Adult: 342 university students (200 Caucasian, 58 African American, 50 Hispanic) | Adult: 60 Hispanic patients presenting to anxiety disorders clinic with self-report of ataque de nervios | Adult: 230 Latina outpatients |

| Assessment method | Single-item self-report (ataque de nervios ever vs never) | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Single-item self-report |

| Prevalence | Lifetime | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Lifetime |

| Comparison group | Yes—participants denying ataque de nervios | Yes—patients not meeting criteria for ataque based on multi-item checklist | Yes—participants scoring below cutoff on ataque de nervios checklist | Yes—all patients self-reported ataque de nervios, but only 32 met 8-symptom criteria | Yes—patients not endorsing ataque de nervios |

| Psychiatric categories | All major psychiatric categories | Anxiety, panic, depression, unexplained neurological complaints | Panic | Panic | PTSD |

| Instruments, validation | CIDI, validated for population | PRIME-MD, Ataque checklist, CIDI validated | PAQ-R, no validation reported | SCID, validated | SCID, validated |

| Functioning | CIDI | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Reference | Liebowitz 199464, Salman 199877 | Caplan 201061 | Livinas 201082 | Alcantara 201255 | Caspi 199862 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | UnSA | USA | USA | USA |

| Cultural concept of distress | Ataque de nervios (attack of nerves) | Coraje (rage), nervios (nerves), susto (fright) | Nervios (nerves) | Padecer de nervios (state of suffering from nerves) | Bebatchet (deep worrying sadness), chkuэt (lost mind) |

| Terminology | Popular illness category | Idioms of distress | Culture-bound syndrome | Culture-bound syndrome | Culturally defined symptoms |

| Research objective | Relationship between ataques and comorbid psychiatric disorders | Detection of distress among Latinos not meeting criteria for depression | Compare performance on Adolescent Nervios Scale between Latinos and non-Latinos | Association with acculturation beyond value of traditional measures of anxiety sensitivity | Association of child loss with mental health and function impairment |

| Recruitment | Clinical | Clinical | School | School | Community |

| Sample | Adult: 156 Hispanic patients presenting to anxiety disorders clinic | Adult: 52 patients in psychiatry OPD | Child: 534 middle school students (307 Latino, 227 Non-Latino) | Adult: 82 mothers of Mexican origin | Adults: 161 parents |

| Assessment method | Single-item self-report | Single-item self-report | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Single-item self-report | Single-item self-report |

| Prevalence | Lifetime | Past month | Unclear | Lifetime | Past week |

| Comparison group | Yes – patients who did not endorse ataque de nervios | Yes – patients with and without self-labeled symptoms | Unclear – participants with no symptoms, only mean scores provided | Yes – mothers who did not have padecer de nervios | Yes – Parents without Bebatchet or chkuэt |

| Psychiatric categories | Anxiety, panic, depression | Depression | Anxiety, depression, anger | Psychological distress | PTSD |

| Instruments, validation | Clinician diagnosis | PHQ-9, validated | BYI-Anxiety, BYI-Depression, BYI-Anger, English language validations | BSI, Spanish BSI validation | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, validation not reported |

| Functioning | Not reported | PHQ-9 function question | School functioning adjustment | Not reported | Select functioning items |

| Reference | Hinton 200373 | Hinton 2011133 | D’Avanzo 199866 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | USA | USA and Europe |

| Cultural concept of distress | Trúng gió (hit by wind) | Worry attacks | Khoucherang (thinking too much) |

| Terminology | Cultural syndrome | None | Culture-bound syndrome |

| Research objective | Phenomenologically characterize ‘hit by the wind'. | Determine role of cultural model of worry in PTSD severity | Evaluate frequency of depression, anxiety and CBS between USA and France for Cambodian refugees |

| Recruitment | Clinical | Clinical | Community |

| Sample | Adult: 60 Vietnamese patients with PTSD | Adult: 130 Cambodian patients (94 with PTSD, 36 without PTSD) | Adult: 155 Cambodian women in France and USA |

| Assessment method | Single-item self-report | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Unclear |

| Prevalence | Prior month | Prior month | Unclear |

| Comparison group | Yes—patients with PTSD and without panic | Yes—patients without PTSD | Unclear |

| Psychiatric categories | Panic, PTSD | PTSD | Depression and anxiety |

| Instruments, validation | Clinical interview with DSM-IV | PCL-C | HSCL, validated in Khmer |

| Functioning | In-depth interviews | Not reported | Not reported |

Table 1c.

Studies conducted in Asia, meeting inclusion criteria for comparison of cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric categories

| Reference | Hinton 201274 | Kleinman 198277 | Bhatia 199159 | Chadda 199064 | Chadda 199563 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Cambodia | China and Taiwan | India | India | India |

| Cultural concept of distress | Cambodian somatic syndromes, khyal attacks (wind attacks), thinking too much | Shenjing shuairuo (neurasthenia, neurological weakness) | Dhat (semen loss in urine) | Dhat (semen loss in urine) | Dhat (semen loss in urine) |

| Terminology | Cultural syndrome and culturally emphasized somatic complaints | Bioculturally patterned illness; somatization | Culture-bound sex neurosis | Culture-bound sex neurosis | Culture-bound neurotic disorder |

| Research objective | Needs assessment of trauma-affected population using culturally-sensitive instrument | Relation of somatization, depression, and neurasthenia with cultural context | Psychiatric diagnosis, presenting symptoms and treatment response among those with Dhat | Psychiatric and STI diagnoses among persons with Dhat | Illness behaviour among persons with Dhat |

| Recruitment | Community | Clinical | Clinical | Clinical | Clinical |

| Sample | Adult: 139 adults identified by human rights group | Adult: 100 Chinese and 51 Taiwanese patients diagnosed with neurasthenia | Adult: 114 men presenting to psychiatry OPD with psychosexual complaints | Adult: 52 men self-presenting to psychiatry OPD with passage of dhat in urine | Adult: 100 patients presenting to psychiatry OPD |

| Assessment method | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Clinician | Clinician | Single-item self-report | Single-item self-report |

| Prevalence | Unclear | Lifetime | Current | Current | Current |

| Comparison group | Unclear—only SPS mean scores provided | No—all patients had neurasthenia diagnoses | Yes—men with sexual complaints without dhat | No—all patients reported dhat | Yes—denial of dhat complaint |

| Psychiatric categories | PTSD | Anxiety, depression, somatization, chronic pain | Depression | Anxiety, depression | Anxiety (GAD, panic, OCD), depression, somatoform disorders |

| Instruments, validation | HTQ, PCL-C, CSSI; PCL-C clinically validated in Khmer | Clinician diagnoses | HAM-D | Clinical interview | Clinical interview with DSM-III-R criteria |

| Functioning | Perceived limitations related to health status | Clinical interview | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Reference | Dhivak 200767 | Gautham 200869 | Perme 200591 | Singh 198596 | Bhatia 199958 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | India | India | India | India | India |

| Cultural concept of distress | Dhat (semen loss in urine) | Dhat (semen loss in urine) | Dhat (semen loss in urine) | Dhat (semen loss in urine) | Dhat (semen loss in urine), koro (genital retraction) |

| Terminology | Culture-bound syndrome | Culture-bound syndrome | Culture-bound syndrome | Commonly recognized clinical entity in defined culture | Culture-bound syndrome |

| Research objective | Prevalence of depression among persons with dhat | Male sexual health concerns evaluated from biomedical, anthropological and psychiatric frameworks | Compare dhat and non-dhat patients on illness beliefs and somatization | Among males with potency disorders, assess cultural illness and psychiatric disorders | Sociodemographics and psychiatric comorbidity among persons with CBS |

| Recruitment | Clinical | Clinical | Clinical | Clinical | Clinical |

| Sample | Adult: 30 patients presenting to psychiatry OPD with complaint of semen loss in urine | Adult: 366 men presenting to OPDs with sexual/genital complaints | Adult: 61 patients presenting to OPD without mood or anxiety disorders | Adult: 50 consecutive patients in psychiatry OPD with sexual dysfunction complaint | Adult: 60 adults presenting to psychiatry OPD with psychosexual complaints |

| Assessment method | Clinician | Single-item self-report | Clinician | Clinician | Single-item self-report |

| Prevalence | Current | Current | Unclear | Current | Unclear |

| Comparison group | No—all patients diagnosed with dhat | Yes—dhat negative men included | Yes—participants not meeting clinical criteria for dhat | Yes—patients not clinically diagnosed with dhat | Yes—patients without dhat or koro |

| Psychiatric categories | Depression | Psychological distress | Somatization, fatigue | Anxiety, depression, fatigue, psychotic depression | Anxiety, depression |

| Instruments, validation | HAM-D | GHQ, validation information not provided | SSI, CFS, validation not reported | ADI, validation not reported | Clinical interview |

| Functioning | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Reference | Weaver 201197 | Kohrt 200478 | Kohrt 200579 | Min 201085 | Park 200187 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | India | Mongolia | Nepal | South Korea | South Korea |

| Cultural Concept of Distress | Tension | Yadargaa (nervous fatigue) | Jham-jham (paraesthesia) | Hwa-byung (‘fire/projection of [accumulated] anger into the body’) | Hwa-byung (‘fire/projection of [accumulated] anger into the body’) |

| Terminology | Idiom used to express stress | Culturally appropriate indicator of distress | Somatization | Culture-bound syndrome | Culture-bound syndrome |

| Research objective | Connection among diabetes, mental health and social roles | Prevalence of yadargaa and its association with socioeconomic changes | To evaluate the role of physical comorbidities in somatic presentation of depression | Compare comorbidity of HB with other psychiatric disorders | Prevalence of HB, identify differentiating symptoms and evaluate associated SES factors |

| Recruitment | Clinical | Community | Community, representative | Clinical | Community |

| Sample | Adult: 33 women with type 2 diabetes | Adult: 193 adults in rural and urban settings | Adult: 316 adults in rural setting | Adult: 280 psychiatric patients | Adult: 2807 women age 41-65 years |

| Assessment method | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Single-item self-report | Single-item self-report | Clinician | Self-report multi-symptom inventory |

| Prevalence | Current (2 weeks) | Current | Current (2 weeks) | Unclear | Unclear |

| Comparison group | Yes—participants scoring below threshold on Tension scale | Yes—participants not endorsing yardargaa | Yes—participants not endorsing jham-jham | Yes—patients not meeting clinician ratings for hwa-byung | Yes—sample not endorsing Hwa-byung symptoms |

| Psychiatric categories | General psychological distress | Anxiety, depression, somatization, chronic fatigue | Anxiety, depression, general psychological distress | Depression, anxiety | Depression |

| Instruments, validation | HSCL, Tension scale, not clinically validated | CDI, SCL-90, not validated | BAI, BDI, GHQ, all instruments validated in Nepali | Hwa-byung Diagnostic Criteria and Hwa-byung scale, Korean SCID | Hwa-byung Symptom Questionnaire, no validation information |

| Functioning | Role fulfilment | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Reference | Choy 200865 | Phan 200492 |

|---|---|---|

| Country | South Korea and USA | Vietnam/Australia |

| Cultural concept of distress | Taijin kyofusho (fear of interpersonal relations—Japanese), taein kong po (fear of interpersonal relations—Korean) | lo âu sợ hãi (anxiety), phiền não tâm thần (depression), xáo trộn tâm thần và thế xác (somatization) |

| Terminology | East Asian syndrome | Indigenous idioms of distress |

| Research objective | Assess specificity of cultural symptoms in a cross-cultural comparison | Develop and validate an ethnographically derived measure of anxiety, depression and somatization |

| Recruitment | Clinical | Clinical |

| Sample | Adult: 64 patients in Korea and 181 patients in USA with SAD and no other diagnoses | Adult: 185 patients from psychiatry OPD and primary care |

| Assessment method | Self-report multi-symptom inventory | Self-report multi-symptom inventory |

| Prevalence | Unclear | Current |

| Comparison group | Yes—patients with SAD and low scores on TKS inventory | Yes—patients scoring below threshold on PVPS |

| Psychiatric categories | Social anxiety disorder | Anxiety, depression, somatization |

| Instruments, validation | TKS Questionnaire, BDI II Korean validation | PVPS, DIS, and naturalist diagnosis, Vietnamese HSCL validated |

| Functioning | Sheehan Disability Scale | Not reported |

ADI, Amritsar Depressive Inventory; APAI, Acholi Psychosocial Assessment Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BFSS, Brain Fag Symptom Scale; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; BYI, Beck Youth Inventory; CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CDI, Chinese Depression Inventory; CFS, Chalder Fatigue Scale; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Inventory; CISR, Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised; CSSI, Cambodian Somatic Symptom and Syndrome Inventory; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; DISC, Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale); HSCL, Hopkins Symptom Checklist; HTQ, Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; KI, Key Informant; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; NLAAS, National Latino Asian American Study; OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder);OPD, Outpatient Department; PAQ-R, Panic Attack Questionnaire-Revised; PCL-C, Posttraumatic Stress Checklist; PDS, Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; PSE, Present State Examination; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; PVPS, Phan Vietnamese Psychiatric Scale; SAD, Social Anxiety Disorder; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; SCL-90, Somatic Checklist-90 item; SPS, Spirit Possession Scale; SRQ, Self-Reporting Questionnaire; SSI, Somatization Screening Index; SSQ, Shona Symptom Questionnaire; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; TKS, Taijin Kyofu Sho.

Quality ratings: SAQOR-CPE

We reviewed the studies to identify types of data commonly reported, and we drew upon broader CCD literature to consider key aspects of CCD relevant to quantitative studies that could influence or confound associations between CCD and psychiatric disorder. These issues were incorporated into the Systematic Assessment of Quality in Observational Research (SAQOR)98 to develop a modified version for Cultural Psychiatry Epidemiology (CPE): the SAQOR-CPE. Table 2 lists the seven categories and their criteria. Table 3 includes the quality scoring for individual studies in the review. Below we describe each category and criterion.

Table 2.

Systematic Assessment of Quality in Observational Research—Cultural Psychiatry Epidemiology (SAQOR-CPE) adaptation and scoring criteria

| SAQOR original Description | Cultural Psychiatry Epidemiology (CPE) modifications | SAQOR-CPE modified evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAMPLE | |||

| Representative | The study sample is representative of the source population | The sample should employ cultural categories (e.g. ethnicity labels) salient to participants and represent the diversity of subgroups potentially affected by CCD | Yes = representative sample with salient cultural groups and inclusion of culturally identified vulnerable groups; No = convenience and other non-representative samples, or categorization is not culturally salient |

| Source | The study must include a clear description of where the sample was drawn from. Study participants may be selected from the target population (all individuals to whom the results of the study could be applied), the source population (a defined subset of the target population from which participants are selected), or from a pool of eligible subjects (a clearly defined and counted group selected from the source population) | The study should clearly state whether persons with CCD were included because of self-labelling, being labelled by a clinician or being labelled by some other key informant. If the source is clinician- or key informant-identified, then the discrepancy between other- and self-labelling should be reported. | Yes = clearly defined group to which generalizations could be drawn (e.g. population, subgroup or patients); for CCD, clearly defined group of self-endorsing idiom or clinician-/key informant-assigned criteria; differences between self- and other-labelling should be reported; No = select or biased group not generalizable beyond research study (e.g. CCD based on research criteria only, such as number of somatic complaints, but not generalizable to application of CCD outside study contexts) |

| Method | The method of participant recruitment/selection must be given | Recruitment processes in clinical or community settings should be reported because public vs private settings may impact on endorsement of CCD. Potential biases related to stigmatizing aspects of CCD should be considered in recruitment method. For key informant-identified participants, potential biases should be addressed such as not wanting to label individuals in positions of power as suffering from CCD, especially if key informants are known to the community | Yes = method of recruitment reported, potential biases in CCD endorsement from recruitment method should be discussed; number of persons approached and number consenting or refusing should be included; No = recruitment method not described or no acknowledgement of recruitment approach and CCD endorsement bias |

| Size | The authors should describe how the sample size was determined and adequacy of sample size to address research question | Sample sizes ideally should be based on power calculations with prevalence estimates. For commonly researched CCD such as nervios-related conditions, dhat and hwa-byung, prevalence estimates in clinical and community settings are available. For novel CCD studies, key informants and primary care clinicians could be used to grossly estimate prevalence in order to determine if CCD are rare or common in the target group | Yes = power calculation for sample size included or ethnographic prevalence estimate based on key informants; No = no rationale given for sample size |

| Inclusion/ exclusion criteria | All inclusion and exclusion criteria should be explicitly described unambiguously and applied equally to all groups | Inclusion/exclusion criteria should be addressed in three domains: cultural group, CCD and psychiatric disorder. If CCD are being investigated in a particular group, then the cultural inclusion/exclusion should be clear, e.g. self-labelling, primary language, location of residence. For CCD, inclusion and exclusion criteria should refer to self-endorsement, current or prior episodes, duration of CCD required for inclusion and comorbidity with other CCD. For psychiatric disorders, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria especially regarding substance use disorders, psychotic disorders and cognitive disorders should be described | Yes = defined criteria, e.g. inclusion age, spoken language, ethnicity etc. CCD current vs ever, duration, etc. Exclusion of psychosis, cognitive impairment, substance misuse; No = unknown criteria for cultural group inclusion, unknown psychiatric or physical comorbidity, unknown prior episodes of CCD |

| CONTROL/COMPARISON GROUP | |||

| Inclusion | Unless it is a descriptive study or case report/series, control group must be included | To draw conclusions about association of CCD with psychiatric disorders, physical health problems, traumatic exposures, socioeconomic vulnerability etc., it is crucial to have a control group which does not endorse the CCD. Then comparisons can be made regarding greater or lesser likelihood among those with CCD | Yes = representative community sample with persons not endorsing CCD or clinical or community sample with matched participants not endorsing CCD; No = lack of comparison group |

| Identifiable | Is there a clear distinction between the groups in the study? Are the same variables considered in the control group as in the exposed group(s)? | Control/comparison groups should be clearly distinguished based on CCD status. Lifetime CCD experience is generally straightforward. However, when only current CCD are assessed, controls may include participants with recent CCD episodes that concluded before the study target period | Yes = control of confounds such as other disorders in cases and controls; clear distinction between lifetime or current CCD; No = comparison groups where confounds or prior CCD are not controlled |

| Source | Control group should be drawn from the same population as the exposed group(s) | The source for controls in the community or clinic should come from comparable populations based on cultural/ethnic/linguistic group, health status, age, residence etc. Recruitment strategies should be the same for controls to minimize impact of recruitment method of biasing endorsement | Yes = cases and controls drawn from comparable social groups andsimilar context (e.g. community or clinic), using the same recruitment method; No = lack of reporting about control source or differences in source that increase risk of bias |

| Matched or randomize | For matched studies, matching criteria are given. For randomized studies, randomization method is described | To identify key features that distinguish persons with CCD from those who do not endorse the CCD, matching and other strategies may be used. If used, the matching criteria and analytic process should be described in detail. Matching criteria should be relevant to the CCD | Yes = matching criteria (e.g. propensity score matching or selection process); No = no matching or randomization procedure used or described |

| Statistical control | Groups selected for comparison are as similar as possible in all characteristics except for their exposure status | Statistical analyses should control for as many potential confounds as possible, with special attention to confounds that could influence CCD endorsement, such as years in a new country for immigrants and refugees, language proficiency, ethnic group and region of residence | Yes = control for confounds or other criteria when comparing between groups;No = bivariate comparisons that do not include potential confounds |

| CULTURAL CONCEPTS OF DISTRESS (CCD) | |||

| CCD categorical | Not applicable | Participants should be classifiable as CCD and non-CCD groups based on current or lifetime prevalence, clinician diagnoses or key informant opinions. Researcher-defined criteria (e.g. symptom cutoff scores) alone are insufficient to capture culturally significant implications of CCD status | Yes = self-report for (current or lifetime) CCD endorsed or denied; No = unable to assess from data whether persons endorse CCD or deny (only proxies used) |

| CCD prevalence | Not applicable | CCD classification time period should be clearly defined. Is lifetime or current prevalence used? If current prevalence, then what is the time period: 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month etc.? | Yes = lifetime or current prevalence is reported, and period of current prevalence is specified; No = unclear prevalence reporting |

| CCD label type | Not applicable | The type of CCD should be described with qualitative information, as well as quantitative information if possible. For example, is CCD attribution based on single objective or subjective symptoms, or co-occurring symptoms, certain types of exposures and presumed causes or specific vulnerability groups? Labels such as symptom-based CCD, syndrome-based CCD, aetiology-based CCD or mixed may be applicable in some studies. When possible, if a CCD is based on a presumed exposure, the type and timing of the exposure should be reported | Yes = qualitative or quantitative information is provided based on how CCD is classified, e.g. symptom, syndrome, aetiology or mixed; No = unclear why participants endorse CCD label |

| CCD severity | Not applicable | Severity information should be provided, e.g. frequency of attacks or episodes, number of symptoms, intensity of episodes or symptoms, or degree of impairment associated with CCD. Severity information allows for comparisons of mildly or severely affected individuals and the association with other variables. | Yes = severity assessed through frequency, severity, number of associated symptoms or functioning; No = unclear how severe; unclear association with impairment |

| CCD course | Not applicable | Information regarding CCD course prevents spurious associations or misinterpretation of findings of psychiatric associations. CCD age of onset, duration of most recent episode and presence of episodic or chronic symptoms should be included. Information regarding timing of psychiatric symptoms should be included to determine whether CCD precedes, co-occurs with, follows or is independent of psychiatric disorders | Yes = age of onset, duration of episode, number of episodes, and timing with psychiatric diagnosis; No = Unclear whether current or prior episode is detected in study, unclear duration, unclear chronic vs episodic course |

| MEASUREMENT QUALITY | |||

| Exposure | How did the authors ascertain that the cases/exposed group had indeed been exposed to the variable of interest? | Most CCDs are associated with a presumed stressful exposure, in the form of chronic or episodic threats. Information should be collected on the types and timing of exposure and temporal relationship of the CCD to the exposure. Exposures should be recorded among both CCD and non-CCD participants. | Yes = information is provided regarding chronic or episodic exposures presumed to associate with CCD; No = no information on exposures reported |

| Outcomes | Tools/methods used to measure the outcome of interest are clearly defined; tools/methods used are sufficient to answer the study question(s); In clinical studies, the outcome assessor was blind to the group exposure status; Medical chart reviews; blood tests; neurological/physical examination; independent assessment by more than one investigator | For cross-cultural research, validity of the psychiatric assessment in the culture of interest should be recorded. If validated in the population of interest, psychometrics such as sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values should be reported. If the instrument is not validated, then transcultural translation108,134 and cross-cultural equivalence determination109 should be described. | Yes = psychiatric instruments validated for use with study population and psychometrics reported; transcultural translation and cross-cultural equivalence reported; No = lack of validated instruments, e.g. only use translation back translation |

| Functional outcomes | Not applicable | Culturally salient assessment of impaired functioning should be reported. It should be determined whether a CCD is associated with impaired functioning or lack of role fulfilment. Without reporting impaired functioning, social performance labels may be incorrectly labelled as CCD | Yes = measure of functioning, ideally with quantitative association with CCD; No = no measure of functioning or impairment reported |

| FOLLOW-UP | |||

| Participants lost to follow-up | Does the study state how many participants were not followed up? | The attrition and follow-up rates should be reported at all time points | Yes = include number; No = not include % lost to follow-up |

| Explanations for lost to follow-up | Was the explanation provided as to why participants could not or would not complete the study? For example, participants moved, gave wrong phone number, did not call back, lost interest in the study etc. | Reason for attrition should be reported if available, e.g. lack of participant transportation, death of participant, dissatisfaction with treatment | Yes = reason included; No = reason not included |

| CCD change | Not applicable | A major limitation in current CCD literature is failure to report change in CCD status at follow-up studies or at post-intervention assessments. All studies with multiple time points should include assessment of CCD at successive assessments. This allows evaluation of whether CCD and psychiatric disorders occur and resolve in comparable or disparate trajectories | Yes = CCD assessed at each time point in the study, including post-intervention if applicable; No = follow-up study or treatment evaluation study that does not include information on CCD status |

| DISTORTING INFLUENCES | |||

| Psychiatric comorbidity | The authors explain how they dealt with depression (or other psychiatric comorbidities) in their analysis of the outcomes: did they take it into account as one of the major confounders? | Comorbidity among psychiatric disorders is high. Studies should account for psychiatric comorbidities when assessing associations between CCDs and psychiatric disorders. This can be done through inclusion/exclusion criteria, statistical controls or both. Studies in which only one psychiatric disorder is investigated do not allow adequate assessment of comorbidity. Commonly neglected comorbidities are substance misuse and psychotic disorders | Yes = control for psychiatric comorbidities through inclusion/exclusion or statistical analysis; No = only one disorder investigated; inclusion/exclusion criteria unclear; only bivariate analyses are used |

| Treatment | The authors explain how they dealt with other psychotropic drugs (and other treatment) participants may have been taking: did they control for them in the analysis of outcomes? | Treatment (both biomedical and traditional) will influence current episodes of CCD. Current or prior psychiatric treatment may impact psychiatric status. Treatment status therefore may confound associations between CCD and psychiatric diagnoses. Current and prior treatment should be included, especially psychiatric care and traditional healing intended to resolve CCD | Yes = treatment status known and controlled in analyses or selection; No = no information provided on current or prior treatment |

| Physical comorbidity | Not applicable | Physical health may be a significant contributor to both CCD and psychiatric disorders. Physical health problems such as micronutrient deficiencies, anaemia, infections and reproductive health problems may underlie CCD and psychiatric complaints. Potential physical health problems that could lead to CCD symptoms should be investigated and controlled for in analyses | Yes = potential physical health confounds addressed and reported through inclusion criteria or statistical analyses; No = no information provided on current or prior physical health |

| Other confounds | The possible presence of confounding factors is one of the principal reasons why observational studies are not more highly rated as a source of evidence. The report of the study should indicate which potential confounders have been considered, and how they have been assessed or allowed for in the analysis | In cross-cultural research, other potential confounds include degree of acculturation for immigrants and refugees, level of language proficiency to engage with different cultural groups, lifetime access or lack of access to healthcare, educational level, degree of exposure to internet and other information technologies etc. | Yes = control for distorting influences in selection or analysis; No = no confounds proposed |

| REPORTING OF DATA | |||

| Missing data | The authors explain how the missing data were addressed and how dealt with during the analysis. Authors indicated numbers of participants with missing data for each variable of interest. For example, the outcomes are provided for some but not all of the participants, or the data are provided for some but not all of the variables | Missing data should be reported in standard epidemiological formats. If approaches are taken to correct missing data (such as imputation), then biases for missing data should be evaluated. For example, if missing data are more common among participants with lower linguistic proficiency, then a common imputation technique could introduce bias by generalization based on high linguistic proficiency respondents | Yes = amount of missing data and how addressed are reported; No = no discussion of missing data |

| Presentation | Data are clearly and accurately presented. Confidence intervals are included where appropriate. All data numbers add up. No cases are counted more than once. There is no confusion in regard to any data presented | Data should be presented to all comparison between CCD participants and non-CCD controls. Dichotomous CCD endorsement (% with lifetime dhat vs those with no lifetime dhat) should be clearly presented | Yes = 95% CI, odds ratios for CCD and variables of interest, sensitivity and specificity for validation or associations are included; No = lack of clear presentation to judge CCD and non-CCD participants |

Table 3.

Systematic Assessment of Quality in Observational Research-Cultural Psychiatry Epidemiology (SAQOR-CPE) ratings

| Abas 199754 | Alcantara 201255 | Bass 200856 | Betancourt 200957 | Bhatia 199159 | Bhatia 199958 | Bolton 200460 | Caplan 201061 | Caspi 199862 | Chadda 199064 | Chadda 199563 | Choy 200865 | D'Avanzo 199866 | Dhikav 200767 | Ertl 201068 | Gautham 200869 | Guarnaccia 199370 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | |||||||||||||||||

| Representative | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| Source | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Method | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Size | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Inclusion/ Exclusion | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Summary | A | A | A | A | A | I | A | A | A | A | A | A | I | I | A | A | A |

| Comparison group | |||||||||||||||||

| Inclusion | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Identifiable | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y |

| Source | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | N | N/A | Y | Y | Y |

| Matched or randomized | N/A | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N/A | N | N/A | N | N/A | N | N | N |

| Statistical control | N/A | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N/A | N | N/A | N | N/A | Y | Y | Y |

| Summary | I | A | A | A | A | I | A | A | A | I | A | I | I | I | A | A | A |

| Cultural Concept of Distress | |||||||||||||||||

| CCD Categorical | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| CCD Prevalence | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| CCD Label Type | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| CCD Severity | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| CCD Course | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y |

| Summary | A | A | A | A | A | I | I | A | A | A | A | I | I | A | I | A | A |

| Measure quality | |||||||||||||||||

| Exposure measure | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Outcome measure | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Functioning | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| Summary | A | A | A | I | A | I | I | A | A | I | I | A | A | I | A | I | A |

| Follow-up | |||||||||||||||||

| Percentage lost | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Reason lost | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Change in CCD | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Summary | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | I | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | I | N/A | N/A | N/A | I | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Distorting influences | |||||||||||||||||

| Psychological comorbidities | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| Physical comorbidities | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Treatment status | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y |

| Other confounds | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Summary | I | I | I | A | A | A | I | A | A | I | I | I | I | I | I | A | A |

| Data | |||||||||||||||||

| Missing data | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Clarity/accuracy of data | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Summary | I | A | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I |

| SAQOR-CPE quality | L | M | L | L | M | VL | VL | M | M | VL | L | VL | VL | VL | L | L | M |

| Guarnaccia 200572 | Guarnaccia 201071 | Hinton 200373 | Hinton 201175 | Hinton 201274 | Interian 200553 | Keough 200976 | Kleinman 198277 | Kohrt 200478 | Kohrt 200579 | Lewis – Fernandez 200280 | Lewis – Fernandez 2010132 | Liebowitz 199481 (Salman 1998) | Livinas 201082 | Lopez 201183 | Makanjuola 198784 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | ||||||||||||||||

| Representative | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Source | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Method | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Power calculation | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Inclusion criteria | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Summary | A | I | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| Comparison group | ||||||||||||||||

| Control inclusion | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Identifiable | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A |

| Source | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A |

| Matched or randomized | N | N | N/A | N | N/A | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N/A |

| Statistical control | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A |

| Summary | A | A | I | A | I | A | A | I | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | I |

| Cultural Concept of Distress | ||||||||||||||||

| CCD Categorical | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| CCD Prevalence | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| CCD Label Type | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| CCD Severity | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| CCD Course | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y |

| Summary | A | A | A | A | I | I | I | A | A | A | A | A | A | I | A | A |

| Measure quality | ||||||||||||||||

| Exposure measure | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| Outcome measure | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Functioning | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Summary | A | A | I | A | A | A | I | A | I | A | A | A | I | A | A | I |

| Follow-up | ||||||||||||||||

| Percentage lost | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y |

| Reason lost | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y |

| Change in CCD | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y |

| Summary | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | A |

| Distorting influences | ||||||||||||||||

| Psychological comorbidities | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| Physical comorbidities | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Treatment status | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | U | N | N | N | N | N |

| Other confounds | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | U | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Summary | I | A | A | I | I | I | I | A | A | A | U | A | I | I | A | I |

| Data | ||||||||||||||||

| Missing data | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Clarity/accuracy of data | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Summary | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I |

| SAQOR-CPE quality | L | L | L | L | L | L | VL | M | L | M | L | M | L | L | M | L |

| Min 201085 | Ola 201186 | Park 200187 | Patel 199588 | Patel 199789 | Pedersen 200890 | Perme 200591 | Phan 200492 | Rasmussen 201193 | Salgado de Snyder 200094 | Singh 198596 | Weaver 201197 | Number (%) of studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | |||||||||||||||||

| Representative | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | 12 (29%) | ||||

| Source | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 44 (98%) | ||||

| Method | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 43 (96%) | ||||

| Power calculation | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 1 (2%) | ||||

| Inclusion criteria | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 42 (93%) | ||||

| Summary | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 41 (91%) | ||||

| Comparison group | |||||||||||||||||

| Control inclusion | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 36 (80%) | ||||

| Identifiable | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | 35 (78%) | ||||

| Source | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | 35 (78%) | ||||

| Matched or randomized | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N/A | N | N | N | N | 0 (0%) | ||||

| Statistical control | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N/A | N | N | N | N | 22 (49%) | ||||

| Summary | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | I | A | A | A | A | 34 (76%) | ||||

| Cultural Concept of Distress | |||||||||||||||||

| CCD Categorical | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | 27 (60%) | ||||

| CCD Prevalence | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 29 (64%) | ||||

| CCD Label Type | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 37 (82%) | ||||

| CCD Severity | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 25 (56%) | ||||

| CCD Course | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | 14 (31%) | ||||

| Summary | I | I | I | A | A | A | I | A | I | I | A | A | 30 (67%) | ||||

| Measure quality | |||||||||||||||||

| Exposure measure | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 32 (71%) | ||||

| Outcome measure | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | 24 (53%) | ||||

| Functioning | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | 20 (44%) | ||||

| Summary | I | A | I | I | A | I | I | A | I | A | I | A | 26 (58%) | ||||

| Follow-up | |||||||||||||||||

| Percentage lost | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 (9%) | ||||

| Reason lost | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 (9%) | ||||