Abstract

Background. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CaUTIs) are the most common hospital-acquired infections worldwide and are frequently polymicrobial. The urease-positive species Proteus mirabilis and Providencia stuartii are two of the leading causes of CaUTIs and commonly co-colonize catheters. These species can also cause urolithiasis and bacteremia. However, the impact of coinfection on these complications has never been addressed experimentally.

Methods. A mouse model of ascending UTI was utilized to determine the impact of coinfection on colonization, urolithiasis, and bacteremia. Mice were infected with P. mirabilis or a urease mutant, P. stuartii, or a combination of these organisms. In vitro experiments were conducted to assess growth dynamics and impact of co-culture on urease activity.

Results. Coinfection resulted in a bacterial load similar to monospecies infection but with increased incidence of urolithiasis and bacteremia. These complications were urease-dependent as they were not observed during coinfection with a P. mirabilis urease mutant. Furthermore, total urease activity was increased during co-culture.

Conclusions. We conclude that P. mirabilis and P. stuartii coinfection promotes urolithiasis and bacteremia in a urease-dependent manner, at least in part through synergistic induction of urease activity. These data provide a possible explanation for the high incidence of bacteremia resulting from polymicrobial CaUTI.

Keywords: Proteus mirabilis, Providencia stuartii, coinfection, urease, UTI, bacteremia, urolithiasis

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CaUTI), the most common health care-associated infection worldwide, accounts for up to 40% of hospital-acquired infections [1]. Data compiled over the last 30 years indicate that up to 86% of CaUTIs are polymicrobial, involving combinations of Proteus mirabilis, Providencia stuartii, Morganella morganii, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae [2–9]. P. mirabilis and P. stuartii are two of the most common causes of CaUTI, and the most consistently found to co-colonize [2, 5, 6, 8–10]. Both species are resistant to numerous antibiotics and have a remarkable ability to persist within the urinary tract despite catheter changes and antibiotic treatment [5, 6, 9].

Potential complications of CaUTI caused by P. mirabilis or P. stuartii include catheter blockage and urolithiasis due to urease activity. P. mirabilis is thought to be the main species responsible for crystalline biofilm formation on catheters and the resulting blockage, and P. stuartii is generally the second most common species isolated from blocked indwelling catheters [6, 10, 11]. Experimentally, a high inoculum of P. mirabilis (2 × 1010 CFU/mL) results in urolithiasis and severe pyelonephritis, while loss of urease activity severely reduces colonization, prevents stone formation, and limits kidney damage, indicating that urease is a major contributing factor to both the severity and persistence of P. mirabilis UTI [12–16]. P. stuartii BE2467 appears to possess two seemingly identical urease enzymes, one plasmid-encoded and one chromosomal [17], although the specific contribution of P. stuartii urease to colonization and severity of infection has yet to be addressed. Notably, urease activity in both of these species is induced by the presence of urea [18–20].

Bacteremia is another complication of P. mirabilis and P. stuartii CaUTI. In long term care facilities, bacteriuria is the source for 45%–55% of bacteremias [1]. Indeed, UTI is a common source of bacteremia for both P. mirabilis and P. stuartii [21–26]. Similar to bacteriuria, bacteremia in patients with long-term catheterization is also frequently polymicrobial [1, 26, 27]. It has been reported that 25% of P. mirabilis bacteremias and up to 51% of P. stuartii bacteremias are polymicrobial [22, 25, 28], suggesting that P. stuartii and P. mirabilis may promote development of bacteremia by other species or are more likely to reach the bloodstream during a polymicrobial infection. This is notable as the mortality rate for polymicrobial bacteremia is increased compared to the already high mortality rate of P. mirabilis or P. stuartii monospecies bacteremia [25, 26].

Despite the staggering data suggesting co-colonization and possible cooperation between P. mirabilis and P. stuartii, the impact of coinfection by these species has yet to be addressed experimentally. In this study, we used a mouse model of ascending UTI to determine the impact of P. mirabilis and P. stuartii coinfection on bacterial persistence, bacteremia, and urolithiasis, as well as the impact of urease on these parameters. The results clearly demonstrate that coinfection increases the incidence of urolithiasis and bacteremia in a urease-dependent manner and indicate synergistic induction of urease activity during co-culture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Proteus mirabilis HI4320 and Providencia stuartii BE2467 were isolated from the urine of catheterized patients in a chronic care facility [8, 29]; ureF::Tn refers to P. mirabilis HI4320 with ureF disrupted by a transposon carrying a kanamycin resistance cassette, resulting in catalytically inactive urease [16, 20]. Bacteria were routinely cultured at 37°C with aeration in 3 mL LB broth (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 0.5 g/L NaCl) or on LB solidified with 1.5% agar. P. mirabilis HI4320 was experimentally determined to be susceptible to <1 µg/mL ampicillin and <5 µg/mL kanamycin while P. stuartii BE2467 was resistant to >50 µg/mL ampicillin and >50 µg/mL kanamycin. Therefore, LB was supplemented with 25 µg/mL kanamycin or 10 µg/mL ampicillin to distinguish between species.

Growth Curves

P. mirabilis, ureF::Tn, and P. stuartii overnight cultures were diluted 1:100, or 1:200 of each species for co-culture, into 3 mL LB or filter-sterilized human urine and incubated at 37°C with aeration for 8 hours. Cultures were sampled every hour for dilution and plating to determine CFU/mL.

Mouse Model of Ascending UTI

Infection studies were carried out as previously described [30] using a modification of the Hagberg protocol [31]. Bacteria were cultured overnight in LB, diluted to an OD600 of approximately 0.2, and CBA/J mice were inoculated transurethrally with 50 µL of 2 × 108 CFU/mL (1 × 107 CFU/mouse). This inoculum is routinely used in the laboratory for monospecies infection with P. mirabilis and generally does not result in urolithiasis. For coinfection experiments, mice were inoculated with 50 µL of a 1:1 mixture of both species containing a total of 2 × 108 CFU/mL (1 × 107 CFU/mouse). Urine was collected 24 hours post-inoculation to ensure that all mice were colonized and on 2, 4, and 7 days post-inoculation as indicated. After 2, 4 or 7 days, mice were euthanized and bladders, kidneys and spleens were harvested into phosphate-buffered saline (0.128 M NaCl, 0.0027 M KCl, pH 7.4). Where indicated, euthanized animals were perfused by making an incision in the right cardiac ventricle and slowly infusing the left ventricle with 20 mL of 0.9% sterile saline prior to organ removal. Gross inspection of bladders and kidneys was performed to assess urolithiasis. Tissues were homogenized using an Omni TH homogenizer (Omni International) and plated using an Autoplate 4000 spiral plater (Spiral Biotech). Colonies were enumerated with a QCount automated plate counter (Spiral Biotech). All animal protocols were compliant with the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) at the University of Michigan Medical School.

As P. mirabilis and P. stuartii colonize the urinary tract to different levels, a coinfection index (COI) was calculated for each organ at each time point by determining the ratio of P. stuartii CFUs to P. mirabilis CFUs recovered from individual coinfected mice and dividing by the ratio of the median CFUs of each species from monospecies infections as follows:

COI = 1 indicates that the ratio of P. stuartii to P. mirabilis from coinfected mice is the same as the ratio when comparing the median CFUs from single species infections. COI > 1 indicates that the ratio favors P. stuartii either because P. stuartii colonized to a higher level during coinfection than single species infection, P. mirabilis colonized at a lower level than during single species infection, or some combination thereof. COI < 1 indicates that the ratio similarly favored P. mirabilis.

Preparation of Crude Protein Cell Free Extracts

Overnight cultures of P. mirabilis, ureF::Tn, and P. stuartii were diluted 1:100 into 30 mL LB, or 1:200 of each species for co-culture, and incubated at 37°C with aeration to an OD600 approximately 0.5. 10 µL were removed for dilution and plating to determine CFU/mL. Cultures were centrifuged (18 000 × g, 10 minutes, 4°C) and pellets were resuspended in filter-sterilized human urine to induce urease expression. After a 30 minute incubation at 37°C with aeration, cultures were centrifuged (18 000 × g, 10 minutes, 4°C), washed twice in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and resuspended in 1 mL sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Bacteria were disrupted by four freeze-thaw cycles, vortexed for 10 seconds after each thaw, sonicated for 10 seconds, and immediately placed on ice. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (16 060 × g, 5 minutes, 4°C) and cell free extracts were used to measure enzyme activity. Protein concentration of the extracts was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific).

Urease Assay

Urease activity was measured as previously described [32]. Reactions were initiated by adding 10 µL of cell free extract to 240 µL of reaction buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.5], 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM EDTA, 300 mM urea) in a 13 × 100 mm test tube and vortexed briefly. Tubes were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes, Berthelot reaction reagents [33] were added, tubes were incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm in a BioSpec UV-1601 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu). Purified Jack Bean urease (Sigma, 15–50 U/mg) was used as a positive control. No-enzyme and no-urea controls were included for each cell free extract tested. A calibration curve was generated with ammonium chloride (0.5–5 mM). 1 unit of urease activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the production of 1 µmol ammonia released per minute. Expected urease activity/mg protein was calculated by determining the urease activity contributed by each species based on their individual activity and their proportion in the co-culture as follows:

|

where ActA and ActB are urease activity/mg protein measured in single cultures of strain A or strain B, CFUA and CFUB are CFUs from strain A or strain B from the co-culture, and CFUtotal are the total CFUs in the co-culture.

Statistical Analysis

Significance was assessed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), nonparametric Mann–Whitney test, Student's t test, Chi-square test, or Wilcoxon signed rank test where appropriate. All P values are two tailed at a 95% confidence interval. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.03.344 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

P. mirabilis and P. stuartii Coexist in LB But Appear to Compete in Urine Due to Urease Activity

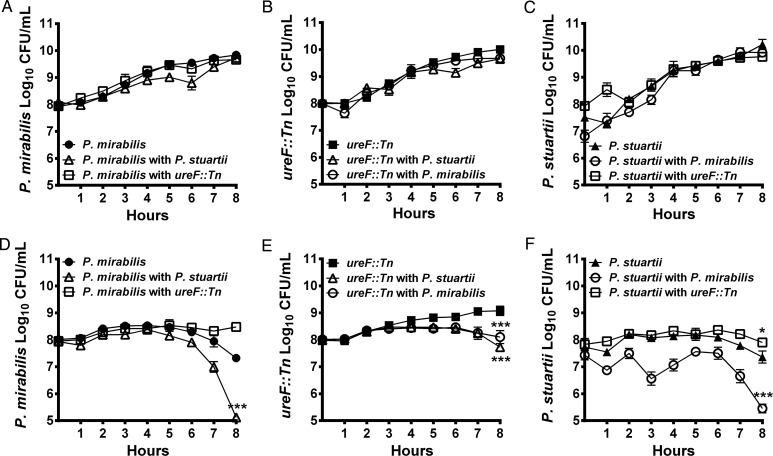

To determine the impact of co-culture on growth, LB broth and human urine were inoculated with P. mirabilis alone, P. stuartii alone, or a 1:1 mixture. Both species grew to similar levels in LB regardless of culture conditions, indicating that P. mirabilis and P. stuartii appear to have a neutral interaction in vitro (Figure 1A–C). When cultured individually in human urine, both species maintained viability for a similar length of time before declining (approximately 5 hours, Figure 1D and 1F). The decline in viability is likely due to urease-mediated alkalinization as both species increased urine pH from approximately 6 to 9 or 10, (data not shown), and no decline was observed for P. mirabilis ureF::Tn (Figure 1E). Interestingly, co-culture in urine resulted in a significant decrease in viability of both P. mirabilis (P = .0001) and P. stuartii (P = .0001) suggestive of competition (Figure 1D and 1F). Conversely, co-culture with ureF::Tn slightly enhanced survival of P. stuartii (P = .0149, Figure 1F). Thus, the apparent competition in urine is likely due to urease activity as co-culture with either P. stuartii or the P. mirabilis parental strain decreased ureF::Tn viability (P = .0001, Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

P. mirabilis and P. stuartii coexist during co-culture. P. mirabilis HI4320, P. mirabilis ureF::Tn, and P. stuartii BE2467 were cultured individually (filled symbols) or co-cultured (open symbols) in LB (A–C) and human urine (D–F). CFU/mL were determined by sampling cultures every hour and plating on plain LB agar and LB containing either 10 µg/mL ampicillin or 25 µg/mL kanamycin to distinguish between species. Error bars represent mean ± SD for 3–8 independent experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .001 by two-way ANOVA.

Coinfection Increases Incidence of Bacteremia and Urolithiasis

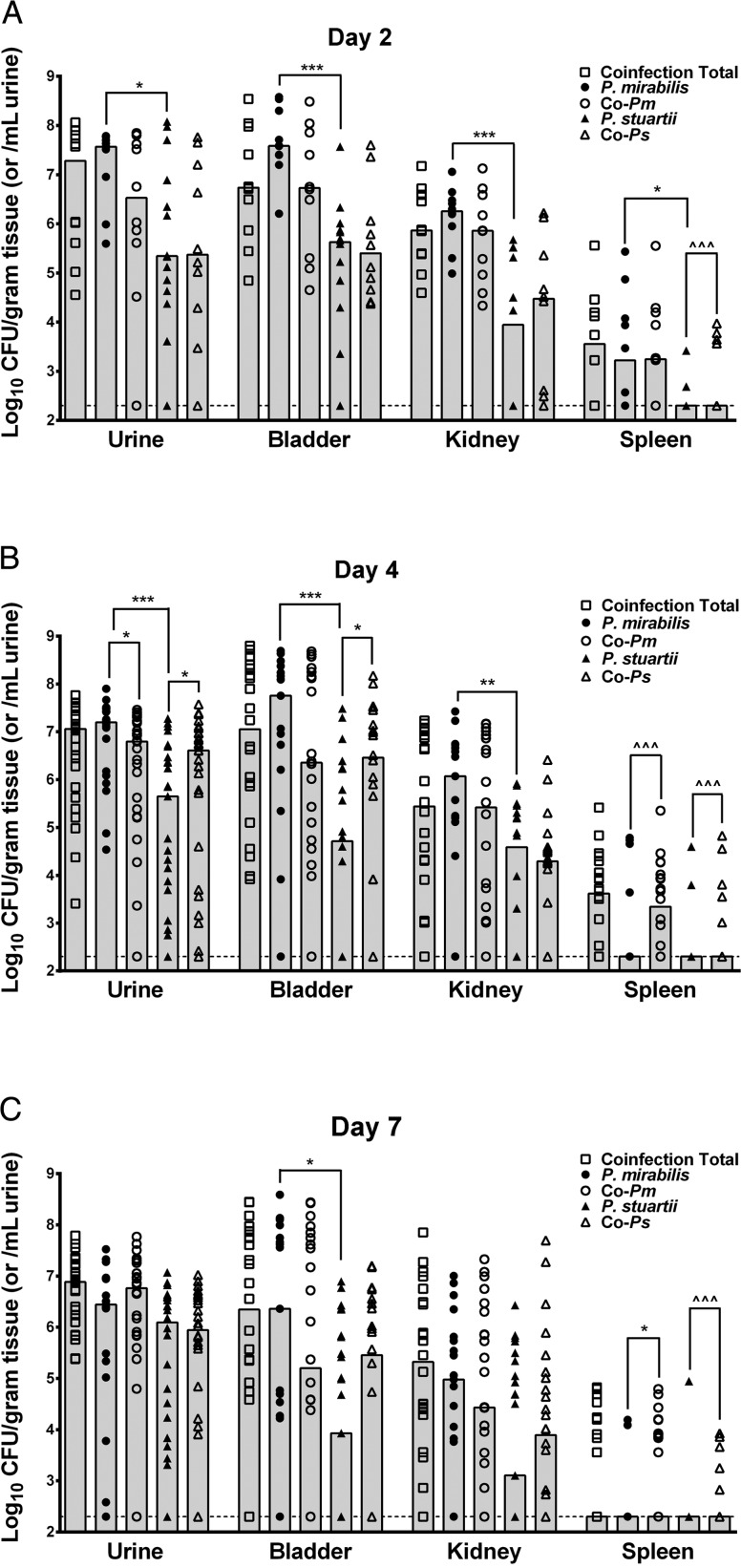

To determine the impact of coinfection on colonization of the urinary tract, mice were infected transurethrally with 1 × 107 CFUs of P. mirabilis, P. stuartii, or a 1:1 mixture containing 5 × 106 CFUs of each species to maintain the same total inoculum. Mice were sacrificed 2, 4, or 7 days post-inoculation to determine bacterial load in the urine, bladder, kidneys, and spleen (Figure 2). Coinfection resulted in a similar total bacterial load as P. mirabilis monospecies infection in all organs at all time points, while P. stuartii generally colonized to a lower level. Despite the nearly identical level of colonization, coinfection resulted in a dramatic increase in the incidence of urolithiasis by gross examination of bladders and kidneys, as well as increased incidence of spleen colonization (Table 1). Urinary tract pathogens are thought to primarily accumulate in the spleen following entry to the bloodstream. Thus, isolation of bacteria from the spleens of coinfected mice indicates increased incidence of bacteremia. To further determine if spleen counts represent blood filtration or tissue colonization, five coinfected mice were perfused prior to organ removal (Supplementary Figure 1). Notably, 2/5 mice retained CFUs in the spleen suggestive of systemic infection.

Figure 2.

Coinfection does not alter total bacterial load but increases colonization by P. stuartii and incidence of bacteremia. CBA/J mice were inoculated by transurethral injection of 50 µL of 2 × 108 CFU/mL (1 × 107 CFU/mouse) of each species or a 1:1 mixture containing the same total CFU/mL. Urine was collected and mice were sacrificed 2 (A), 4 (B), or 7 (C) days post-inoculation. Samples from monospecies infection were plated on plain LB agar to determine CFU/mL urine or gram of tissue of P. mirabilis (filled circles) or P. stuartii (filled triangles). Samples from coinfected animals were plated on plain LB agar to determine total CFUs (open boxes) and LB containing 25 µg/mL kanamycin to distinguish CFU of P. mirabilis (open circles) from P. stuartii (open triangles). Each symbol represents CFU/gram of tissue or ml of urine for one mouse. Gray bars represent the median for a total of 4 independent experiments. Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test, ^^^P < .001 by Chi-square test.

Table 1.

Incidence of Bacteremia and Urolithiasis During Monospecies Infection and Coinfection

| Number of Mice/Total (%) Exhibiting Bacteria in the Spleen or Urolithiasis |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infecting Species | Bacteremia |

Urolithiasisa |

||||||

| Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 7 | Total | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 7 | Total | |

| P. mirabilis | 6/10 (60) | 4/15 (27) | 2/20 (10) | 12/45 (27) | 0/10 (0) | 0/15 (0) | 0/20 (0) | 0/45 (0) |

| P. stuartii | 2/15 (13) | 2/20 (10) | 1/25 (4) | 5/60 (8) | 0/10 (0) | 0/20 (0) | 0/25 (0) | 0/60 (0) |

| ureF::Tn | NDb | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) |

| P. mirabilis + P. stuartii | 6/10 (60) | 14/20 (70) | 12/26 (46) | 26/56 (46) | 0/10 (0) | 4/20 (20) | 2/26 (8) | 6/56 (11) |

| P. mirabilis + ureF::Tn | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) |

| P. stuartii + ureF::Tn | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | 0/10 (0) |

a By gross examination.

b (ND) no data.

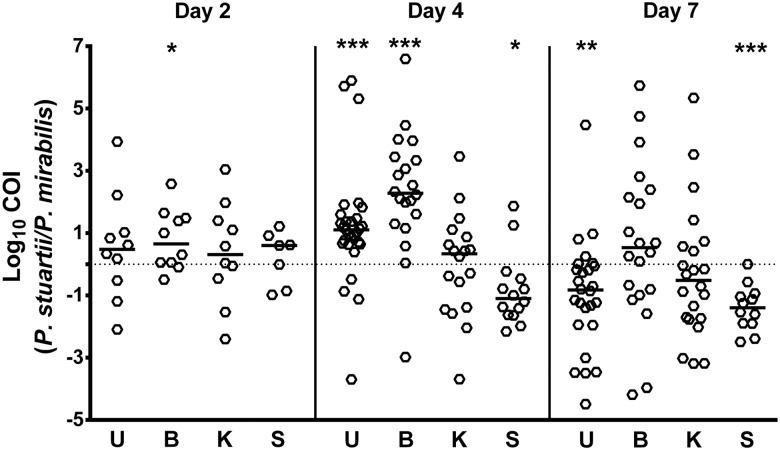

When the proportion of each species from coinfected animals was determined by differential plating, P. mirabilis and P. stuartii generally colonized to similar levels as during monospecies infections (Figure 2). However, coinfection significantly increased the incidence of spleen colonization by P. stuartii at all time points (P = .0001) and enhanced colonization of the urine (P = .0499) and bladder (P = .0322) on day 4. Coinfection also decreased the amount of P. mirabilis in the urine on day 4 (P = .0344) and increased colonization of the spleen on days 4 (P = .0001) and 7 (P = .0129). A modification of the competitive index calculation was used to investigate changes in the ratio of P. stuartii to P. mirabilis from individual coinfected mice compared to single species infection (see Materials and Methods). Using this Coinfection Index (COI), the coinfection provided an advantage to P. stuartii in the bladder on day 2 (P = .0449) and the urine (P = .0001) and bladder (P = .0001) on day 4, while P. mirabilis had the advantage in the spleen on day 4 (0.0353) and the urine (P = .0019) and spleen (P = .0009) on day 7 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Coinfection favors P. stuartii in the bladder and P. mirabilis in the spleen. A coinfection index (COI) was calculated for the urine (U), bladder (B), kidney (K), and spleen (S) at each time point by determining the ratio of P. stuartii to P. mirabilis CFUs recovered from individual coinfected mice divided by the ratio of the median CFUs of each species from monospecies infections. Each symbol represents COI for one mouse. Bars represent the median, dashed line indicates a COI of 1. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 by the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Increased Incidence of Urolithiasis and Bacteremia Requires P. mirabilis Urease

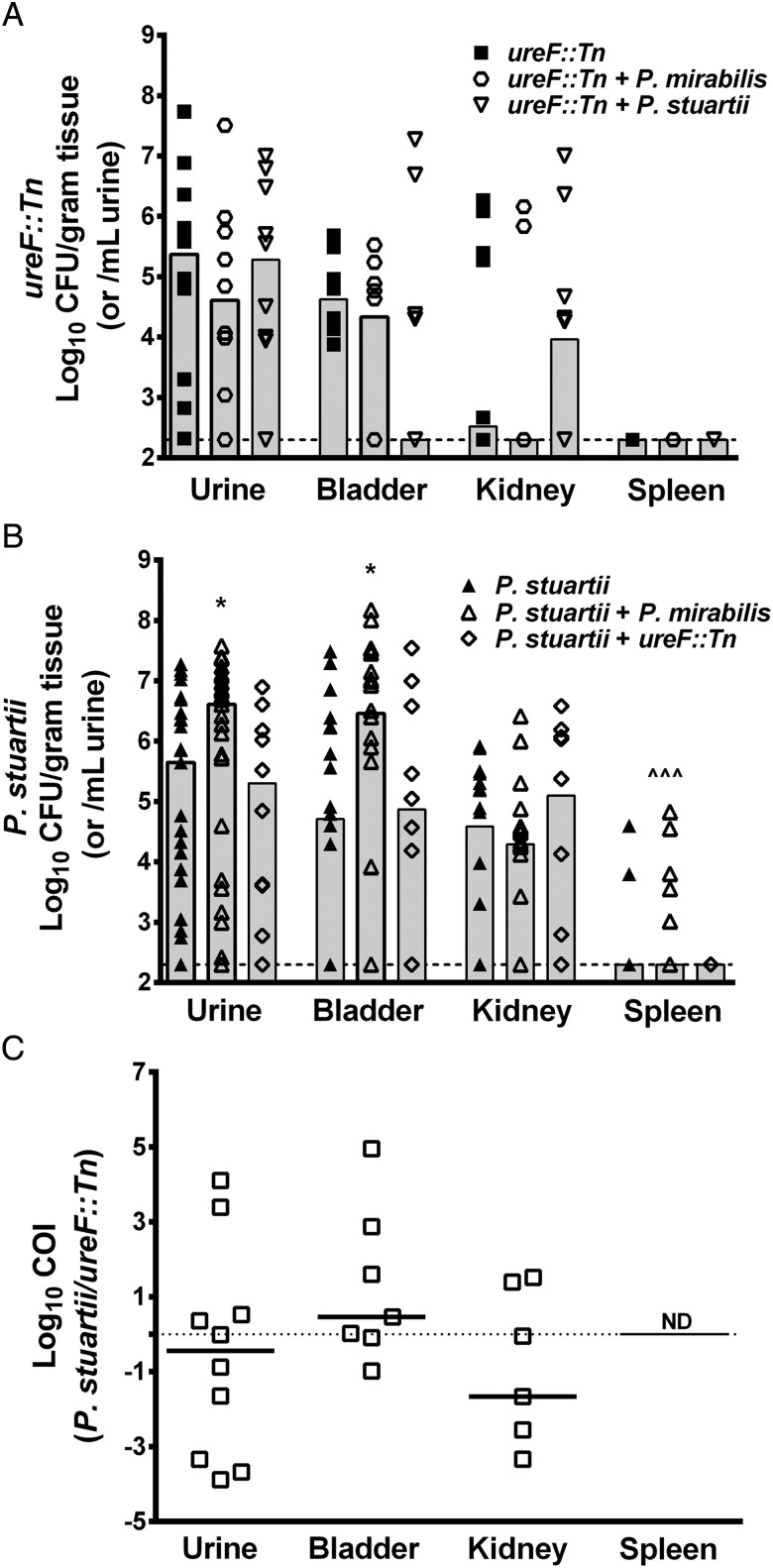

The urease-negative ureF::Tn mutant of P. mirabilis HI4320 was used to determine the impact of combined urease activity during coinfection on development of urolithiasis and bacteremia. Mice were infected with ureF::Tn alone, a 1:1 mix of ureF::Tn and the parental strain of P. mirabilis, or a 1:1 mix of ureF::Tn and P. stuartii. Organs were harvested 4 days post-inoculation as this time point had the highest incidence of urolithiasis and bacteremia for coinfection with wild type P. mirabilis and P. stuartii (Table 1). Consistent with previous studies, ureF::Tn colonized in lower numbers than the parental strain (Figure 4A compared to Figure 2B) [16]. Notably, coinfection with either P. mirabilis or P. stuartii failed to complement the defects of ureF::Tn, and none of these mice developed bacteremia (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Coinfection increases incidence of bacteremia in a urease-dependent manner. CBA/J mice were inoculated by transurethral injection of 50 µL of 2 × 108 CFU/mL (1 × 107 CFU/mouse) of ureF::Tn, a 1:1 mixture of ureF::Tn and the parental strain of P. mirabilis, or a 1:1 mixture of ureF::Tn and P. stuartii. Urine was collected and mice were sacrificed 4 days post-inoculation. A, ureF::Tn CFU/mL urine or gram of tissue from monospecies infection (filled boxes), coinfection with the parental strain of P. mirabilis (open circles), or coinfection with P. stuartii (open triangles). Each symbol represents one mouse. Gray bars represent the median, dashed line indicates limit of detection. Coinfection did not significantly alter ureF::Tn colonization as determined by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test. B, P. stuartii CFU/mL urine or gram of tissue from monospecies infections (filled triangles), coinfection with P. mirabilis (open triangles), or coinfection with ureF::Tn (open diamonds). Each symbol represents one mouse. Gray bars represent the median, dashed line indicates limit of detection. *P < .05 compared to monospecies infection by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test, ^^^P < .001 by Chi-square test. C, COI was calculated for coinfection of P. stuartii and ureF::Tn (open boxes). Bars represent the median, dashed line indicates a COI of 1. COI was not significantly different than 1 for any organ by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. COI in spleen not determined (ND) for P. stuartii and ureF::Tn coinfection as no animals exhibited spleen colonization.

While coinfection with wild type P. mirabilis increased the CFUs of P. stuartii in the urine and bladder and the incidence of bacteremia, coinfection with ureF::Tn failed to increase P. stuartii colonization above that observed for monospecies infection (Figure 4B) and none of the mice developed bacteremia or urolithiasis (Table 1). Comparison of COIs similarly revealed that while coinfection with wild type P. mirabilis provided an advantage to P. stuartii (Figure 3), coinfection with ureF::Tn did not (Figure 4C). These findings indicate that production of urease by P. mirabilis may be critical for the increased colonization and incidence of urolithiasis and bacteremia resulting from coinfection. However, it is important to note that only 5/10 coinfected mice had ureF::Tn in the kidneys at this time point. Therefore, even though none of the mice developed bacteremia or exhibited urolithiasis, a role for other virulence factors in the development of these UTI complications cannot be excluded.

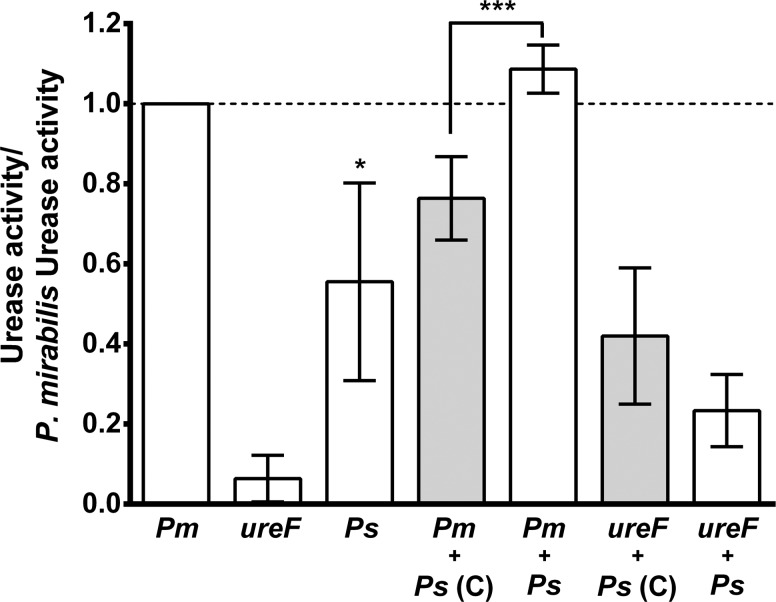

Co-culture Enhances Total Urease Activity

The co-culture experiments and infection studies demonstrated that urease activity contributes to the viability of P. mirabilis and P. stuartii during co-culture in vitro as well as their ability to cause bacteremia during coinfection. We therefore hypothesized that co-culture in urine enhances total urease activity. To test this hypothesis, urease activity was measured in cell free extracts from cultures of P. mirabilis, ureF::Tn, P. stuartii, P. stuartii co-cultured with P. mirabilis, and P. stuartii co-cultured with ureF::Tn following incubation in human urine to induce urease activity (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 1). P. stuartii exhibited a lower level of activity than P. mirabilis when cultured individually (P = .0161), consistent with previous reports [17, 18], and ureF::Tn was negative for urease activity (Figure 5) as were un-induced cultures (data not shown). Interestingly, co-culture of P. mirabilis and P. stuartii resulted in a slightly higher level of urease activity than P. mirabilis alone (P = .0625) and significantly increased activity compared to the expected level based on the proportion of each species in the culture (P = .0003), demonstrating synergistic induction of urease activity. Notably, co-culture of P. stuartii with ureF::Tn resulted in a similar level of urease activity as expected based on the proportion of each species, suggesting that synergistic induction of urease requires active enzyme from both species.

Figure 5.

Co-culture results in synergistic induction of urease activity. P. mirabilis HI4320 (Pm), P. mirabilis ureF::Tn (ureF), and P. stuartii BE2467 (Ps) were cultured individually or co-cultured and incubated in sterile-filtered human urine to induce urease activity. Bars represent mean ± SD urease activity/mg protein normalized to P. mirabilis activity for each of 4–5 independent biological replicates. White bars represent urease activity measured in cell free extracts of each culture. Grey bars represent the expected urease activity as calculated from the activity of single cultures and the proportion of each species in the co-culture (see Materials and Methods). *P < .05 by the Wilcoxon signed rank test, ***P < .001 by Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

Urinary tract infection is the most common cause of sepsis in the elderly population, and the mortality rate for bacteremia originating from a UTI ranges from 25% to 60% and increases with both patient age and catheterization [34–36]. Most knowledge regarding the pathogenesis and complications of UTI, including bacteremia, has been derived from patient data and monospecies infection studies. However, there is a growing appreciation for the prevalence and implications of polymicrobial community-acquired UTI and CaUTI [2–8, 37, 38]. With up to 86% of CaUTI cases involving colonization by multiple species, it is imperative to understand how co-colonization influences persistence and severity of infection. Our results clearly demonstrate that coinfection with P. mirabilis and P. stuartii increases the incidence of bacteremia and urolithiasis. Furthermore, our results underscore the importance of urease in establishment of these complications and indicate a mechanism for synergistic induction of urease activity during coinfection with two urease-positive species.

Interestingly, even though coinfected animals were inoculated with half as many CFUs of each species, P. mirabilis and P. stuartii colonized to the same general level as during monospecies infection. P. mirabilis and P. stuartii may therefore colonize distinct niches within the organs of the urinary tract. If these species do not physically interact within the urinary tract, synergistic induction of urease might occur in response to accumulation of ammonia, depletion of urea, or the overall change in pH. Our results also show that the increased incidence of bacteremia and urolithiasis is not due to an overall increase in bacterial load within the urinary tract but likely relates to urease activity, a specific interaction between the species, or the host response to coinfection. Furthermore, the data indicate that entry to the bloodstream is not a dead end for the infection as the spleens of perfused animals retained bacteria indicative of tissue colonization and systemic infection.

Urease is a known virulence factor for P. mirabilis [13], and urease-mediated alkalinization of urine can cause direct damage to renal tissue [39]. As the increased incidence of urolithiasis and bacteremia were only observed during coinfection with wild type strains and not with the P. mirabilis urease mutant, our data suggest that these UTI complications resulted from synergistic induction of urease activity during coinfection. The increased urease activity observed during co-culture further supports this theory and is in agreement with our growth curve data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report synergistic induction of urease activity.

Enhanced urease activity is the most likely reason for the incidence of urolithiasis in coinfected animals as none of the mice coinfected with ureF::Tn had visible stones. However, urolithiasis was macroscopically assessed by gross examination of bladders and kidneys, so only stones visible without magnification were recorded and smaller stones may have been present but undetected, and only five of the ten mice coinfected with P. stuartii and ureF::Tn exhibited kidney colonization by both species. Therefore, we cannot conclude for certain that P. mirabilis urease is required for urolithiasis based on absence of urinary stones in these five mice, but the lack of synergy during co-culture of P. stuartii and ureF::Tn is in agreement with this hypothesis.

It also remains to be determined if synergistic urease activity is directly responsible for the incidence of bacteremia. Our experimental infection data suggest that P. mirabilis urease must be active for bacteremia resulting from coinfection with the parental strains. There are caveats to working with ureF::Tn as this mutant exhibits a profound colonization defect at seven days post-inoculation [40] and a modest defect at four days post-inoculation in our infection studies. However, four of the ten mice coinfected with P. stuartii and the P. mirabilis ureF mutant exhibited ureF::Tn bladder colonization and five exhibited ureF::Tn kidney colonization. As 70% of mice coinfected with wild type P. mirabilis and P. stuartii displayed systemic infection at this time point, the lack of spleen colonization in these five mice supports a role for P. mirabilis urease in development of systemic infection. Similarly, none of the mice coinfected with P. mirabilis and ureF::Tn exhibited spleen colonization while 27% of mice infected with P. mirabilis alone had CFUs in the spleen four days post-inoculation, suggesting that total urease activity is also critical during monospecies infection.

Other virulence factors are also likely required for development of systemic infection. Based on current understanding of P. mirabilis, there are many ways in which this bacterium may interact with other organisms to influence pathogenicity (see [41] for review). Further investigation will be necessary to better understand how synergistic urease activity contributes to the outcome of coinfection and to identify other factors that promote development of bacteremia with these and other common causes of CaUTI.

P. mirabilis and P. stuartii are both highly antibiotic-resistant organisms, likely contributing to the increased mortality rate observed for polymicrobial bacteremia. Thus, understanding the factors that contribute to increased colonization and systemic infection with these species is of great importance to identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention. CaUTI also commonly involves numerous other urease-positive species which may similarly exhibit synergistic induction of urease activity. It is therefore critical to understand the underlying mechanism responsible for synergistic urease activity and to investigate this phenomenon in other species. Elucidation of the mechanism regulating synergistic induction of urease activity may provide insight into new strategies for prevention of catheter encrustation, urolithiasis, and possibly bacteremia resulting from CaUTI.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We would like to acknowledge Denise Kirschner for her advice in development of the COI calculation and members of the Mobley lab for their helpful comments and critiques.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AI059722 (H.L.T.M.) and F32AI102552 (C.E.A). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, et al. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection in Adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625–63. doi: 10.1086/650482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dedeic-Ljubovic A, Hukic M. Catheter-related urinary tract infection in patients suffering from spinal cord injuries. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2009;9:2–9. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2009.2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronald A. The etiology of urinary tract infection: traditional and emerging pathogens. Dis Mon. 2003;49:71–82. doi: 10.1067/mda.2003.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegman-Igra Y, Kulka T, Schwartz D, Konforti N. Polymicrobial and monomicrobial bacteraemic urinary tract infection. J Hosp Infect. 1994;28:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(94)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahav G, Pinco E, Silbaq F, Bercovier H. Molecular epidemiology of catheter-associated bacteriuria in nursing home patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1031–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1031-1034.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunin CM. Blockage of urinary catheters: Role of microorganisms and constituents of the urine on formation of encrustations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:835–42. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitenbucher RB. Bacterial changes in the urine samples of patients with long-term indwelling catheters. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1585–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mobley HLT, Warren JW. Urease-Positive Bacteriuria and Obstruction of Long-Term Urinary Catheters. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2216–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2216-2217.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren JW, Tenney JH, Hoopes JM, Muncie HL, Anthony WC. A Prospective Microbiologic Study of Bacteriuria in Patients with Chronic Indwelling Urethral Catheters. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:719–23. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macleod SM, Stickler DJ. Species interactions in mixed-community crystalline biofilms on urinary catheters. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1549–57. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stickler DJ, Feneley RC. The encrustation and blockage of long-term indwelling bladder catheters: a way forward in prevention and control. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:784–90. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DE, Russell RG, Lockatell CV, Zulty JC, Warren JW, Mobley HL. Contribution of Proteus mirabilis urease to persistence, urolithiasis, and acute pyelonephritis in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2748–54. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2748-2754.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones BD, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Warren JW, Mobley HL. Construction of a urease-negative mutant of Proteus mirabilis: analysis of virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1120–3. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1120-1123.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dattelbaum JD, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. UreR, the Transcriptional Activator of the Proteus mirabilis Urease Gene Cluster, Is Required for Urease Activity and Virulence in Experimental Urinary Tract Infections. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1026–30. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.1026-1030.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H, Thompson RB, Lockatell V, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. Use of Green Fluorescent Protein To Assess Urease Gene Expression by Uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis during Experimental Ascending Urinary Tract Infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:330–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.330-335.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burall LS, Harro JM, Li X, et al. Proteus mirabilis Genes That Contribute to Pathogenesis of Urinary Tract Infection: Identification of 25 Signature-Tagged Mutants Attenuated at Least 100-Fold. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2922–38. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2922-2938.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones BD, Mobley HL. Genetic and biochemical diversity of ureases of Proteus, Providencia, and Morganella species isolated from urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2198–203. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2198-2203.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones BD, Mobley HL. Proteus mirabilis urease: genetic organization, regulation, and expression of structural genes. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3342–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3342-3349.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholson EB, Concaugh EA, Mobley HL. Proteus mirabilis urease: use of a ureA-lacZ fusion demonstrates that induction is highly specific for urea. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3360–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3360-3365.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Island MD, Mobley HL. Proteus mirabilis urease: operon fusion and linker insertion analysis of ure gene organization, regulation, and function. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5653–60. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5653-5660.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim BN, Kim NJ, Kim MN, Kim YS, Woo JH, Ryu J. Bacteraemia due to tribe Proteeae: a review of 132 cases during a decade (1991–2000) Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:98–103. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000027015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods TD, Watanakunakorn C. Bacteremia due to Providencia stuartii: review of 49 episodes. South Med J. 1996;89:221–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199602000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prentice B, Robinson BL. A review of Providencia bacteremia in a general hospital, with a comment on patterns of antimicrobial sensitivity and use. Can Med Assoc J. 1979;121:745–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warren JW. Providencia stuartii: a common cause of antibiotic-resistant bacteriuria in patients with long-term indwelling catheters. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:61–7. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanakunakorn C, Perni SC. Proteus mirabilis bacteremia: a review of 176 cases during 1980–1992. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:361–7. doi: 10.3109/00365549409008605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudman D, Hontanosas A, Cohen Z, Mattson DE. Clinical correlates of bacteremia in a Veterans Administration extended care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:726–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb07175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melzer M, Welch C. Outcomes in UK patients with hospital-acquired bacteraemia and the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:329–34. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muder RR, Brennen C, Wagener MM, Goetz AM. Bacteremia in a long-term-care facility: a five-year prospective study of 163 consecutive episodes. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:647–54. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.3.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mobley HL, Chippendale GR, Fraiman MH, Tenney JH, Warren JW. Variable phenotypes of Providencia stuartii due to plasmid-encoded traits. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:851–3. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.5.851-853.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson DE, Lockatell CV, Hall-Craigs M, Mobley HL, Warren JW. Uropathogenicity in rats and mice of Providencia stuartii from long-term catheterized patients. J Urol. 1987;138:632–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagberg L, Engberg I, Freter R, Lam J, Olling S, Svanborg Eden C. Ascending, unobstructed urinary tract infection in mice caused by pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli of human origin. Infect Immun. 1983;40:273–83. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.273-283.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senior BW, Bradford NC, Simpson DS. The ureases of Proteus strains in relation to virulence for the urinary tract. J Med Microbiol. 1980;13:507–12. doi: 10.1099/00222615-13-4-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weatherburn MW. Phenol-Hypochlorite Reaction for Determination of Ammonia. Anal Chem. 1967;39:971. &. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tal S, Guller V, Levi S, et al. Profile and prognosis of febrile elderly patients with bacteremic urinary tract infection. J Infect. 2005;50:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ackermann RJ, Monroe PW. Bacteremic urinary tract infection in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:927–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Hasan MN, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Bacteremia complicating gram-negative urinary tract infections: a population-based study. J Infect. 2010;60:278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croxall G, Weston V, Joseph S, Manning G, Cheetham P, McNally A. Increased human pathogenic potential of Escherichia coli from polymicrobial urinary tract infections in comparison to isolates from monomicrobial culture samples. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:102–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.020602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kline KA, Schwartz DJ, Gilbert NM, Hultgren SJ, Lewis AL. Immune modulation by group B Streptococcus influences host susceptibility to urinary tract infection by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2012;80:4186–94. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00684-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musher DM, Griffith DP, Yawn D, Rossen RD. Role of urease in pyelonephritis resulting from urinary tract infection with Proteus. J Infect Dis. 1975;131:177–81. doi: 10.1093/infdis/131.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Himpsl SD, Lockatell CV, Hebel JR, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. Identification of virulence determinants in uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis using signature-tagged mutagenesis. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1068–78. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/002071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armbruster CE, Mobley HLT. Merging mythology and morphology: the multifaceted lifestyle of Proteus mirabilis. Nat Rev Micro. 2012;10:743–54. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.