Abstract

Background

The Lathyrus genus includes 160 species, some of which have economic importance as food, fodder and ornamental crops (mainly L. sativus, L. cicera and L. odoratus, respectively) and are cultivated in >1·5 Mha worldwide. However, in spite of their well-recognized robustness and potential as a source of calories and protein for populations in drought-prone and marginal areas, cultivation is in decline and there is a high risk of genetic erosion.

Scope

In this review, current and past taxonomic treatments of the Lathyrus genus are assessed and its current status is examined together with future prospects for germplasm conservation, characterization and utilization. A particular emphasis is placed on the importance of diversity analysis for breeding of L. sativus and L. cicera.

Conclusions

Efforts for improvement of L. sativus and L. cicera should concentrate on the development of publicly available joint core collections, and on high-resolution genotyping. This will be critical for permitting decentralized phenotyping. Such a co-ordinated international effort should result in more efficient and faster breeding approaches, which are particularly needed for these neglected, underutilized Lathyrus species.

Keywords: Diversity, genetic resources, Lathyrus sativus, L. cicera, Fabaceae, legumes, plant breeding, protein crops

INTRODUCTION

Predictions are that population and income growth will double the global demand for food by 2050, effectively increasing competition for crops as sources of bioenergy and fibre and for other industrial purposes (http://www.fao.org). Compounding the pressure for increased agricultural output are looming threats of water scarcity, constraints on soil fertility, and climate change. The highly resilient Lathyrus species (Fabaceae) can play an important role in these immense agricultural challenges. More sustainable management of renewable soil and water resources, in concert with more efficient utilization of genetic diversity, will be key to achieving the necessary productivity gains (Cobb et al., 2013). Genetic diversity provides the basis for all plant improvement.

In this review, we begin by briefly assessing current and past taxonomic treatments of the Lathyrus genus. We then discuss a survey of interesting variable characters used in characterization of its germplasm collections and examine new approaches for diversity analysis, with a particular emphasis on the importance of diversity analysis for L. sativus and L. cicera breeding.

AGRONOMIC POTENTIAL OF LATHYRUS SPECIES

The Lathyrus genus, which includes some 160 species (Allkin et al., 1986), is distributed throughout temperate regions of the northern hemisphere and extends into tropical East Africa and South America. Its main centre of diversity is in the Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian regions, with smaller centres in North and South America (Kupicha, 1983).

Members of the Lathyrus genus include food and fodder crops, ornamentals, soil nitrifiers, dune stabilizers, important agricultural weeds, and model organisms for genetic and ecological research (Kenicer et al., 2005). Most members of Lathyrus are mesophytes of open woodlands, forest margins and roadside verges, but littoral, alpine and more drought-tolerant species are also represented (Kenicer et al., 2005). Both annual and perennial species of Lathyrus occur, many of which have a climbing habit using simple or branched tendrils. Among the cultivated Lathyrus species, L. sativus (grass pea) is the most important as a food crop and has been central for animal feed or fodder since ancient times. Grass pea cultivation originated around 6000 BC and might have been the first crop domesticated in Europe (Kislev, 1989). Although its cultivation is in regression, it is still grown in 1·5 Mha, mainly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (Kumar et al., 2011; Girma and Korbu, 2012; Hillocks and Maruthi, 2012). Grass pea is considered the most promising underutilized source of calories and protein for populations in drought-prone and marginal areas of Asia and Africa (Hillocks and Maruthi, 2012), with the potential for introduction in Australia (Hanbury et al., 2000), North America (Rao and Northup, 2011; Calderón et al., 2012; Gusmao et al., 2012) and China (Yang and Zhang, 2005).

However, grass pea suffers from a reputation of being toxic, as its overconsumption under certain circumstances has caused neurolathyrism, a neurotoxic disease (Lambein and Kuo, 2009). The disabling effects of prolonged dependence on grass pea due to its content of the neurotoxin β-N-oxalyl-l-α,β-diaminopropionic acid (ODAP) led to the decision that the crop should be abandoned as human food, and seed sales were banned in some countries (Enneking, 2011). However, given the increasing need for resilient food crops, improvement of grass pea is still considered a priority by national and international research centres. Major efforts in grass pea breeding in the last 50 years have been aimed at reducing the ODAP content, resulting in a number of cultivars with low ODAP being released (Kumar et al., 2011). There is also agreement today that ODAP content in itself does not seem to be a problem because grass pea is harmless to humans and animals when consumed as part of a balanced diet (Getahun et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Lambein and Kuo, 2009) and because seeds can be partly detoxified by various processing methods such as fermentation, or pre-soaking in alkaline solutions and cooking (Kuo et al., 2000; Kumar et al., 2011). There is even the hypothesis that nitriles are the causative agents of neurolathyrism rather than ODAP (Llorens et al., 2011). Additionally, we should not neglect any potential pharmacological benefits of ODAP (Lan et al., 2013).

Other economically important species grown commercially are the forage crop chickling vetch (L. cicera) and the ornamental sweet pea (L. odoratus). Lathyrus cicera has been cultivated since ancient times, and was domesticated in Southern France and the Iberian Peninsula soon after the introduction of agriculture into the area (Kislev, 1989). It is used as animal feed (White et al., 2002). Lathyrus odoratus originates from Southern Italy and has become an economically important ornamental plant grown for its cut flowers and for garden decoration. Other species such as L. belinensis, L. chloranthus, L. vernus, L. tingitanus, L. grandiflorus, L. latifolius, L. rotundifolius or even L. sativus also have potential ornamental use (Parsons, 2009). Other species are important for human consumption only in certain countries, such as L. clymenum or L. ochrus in areas of Greece, Cyprus, Italy or Turkey (Sarpaki and Jones, 1990; Jones, 1992).

Lathyrus species such as L. sativus also have potential as sources of variation for closely related important legumes such as pea (Pisum sativum) and, although they are cross-incompatible, there is potential for somatic hybridization (Durieu and Ochatt, 2000). Schaefer et al. (2012) also point out that a group of often overlooked Mediterranean Lathyrus species, L. gloeosperma, L. neurolobus and L. nissola, might be particularly appealing for pea breeding because of this group's close relationship to the Pisum genus. Their beneficial traits include drought tolerance and a perennial life form.

PHYLOGENY AND PHYLOGEOGRAPHY

The Lathyrus genus belongs to the tribe Fabeae (syn. Vicieae) along with Vicia, Lens, Pisum and Vavilovia (reviewed in Smýkal et al., 2010). Recently, Schaefer et al. (2012) concluded that the Fabeae tribe evolved in the Eastern Mediterranean in the middle Miocene, and it spread from there across Eurasia, into Tropical Africa, and at least seven times across the Atlantic and Pacific to the Americas. Long-distance dispersal events seem to be the most probable causes for these Atlantic crossings, with Schaefer et al. (2012) rejecting the hypothesis of ancient steppingstone dispersal via the Atlantic islands. These same authors, using phylogenetic data, suggested that the genus Lathyrus is not monophyletic and that a more natural classification of Fabeae should also include Pisum and Vavilovia. This regrouping is also supported by the currently available whole-plastid genomes of L. sativus and P. sativum (Magee et al., 2010). Furthermore, the genera Pisum and Lathyrus share the phytoalexin pisatin, which is not found in Vicia or Lens (Robeson and Harborne, 1980).

Most Lathyrus species are diploid (2n = 14), with a few natural autopolyploids or allopolyploids, or contain both diploid and autopolyploid forms. Many species show similar chromosome morphology although their nuclear DNA content may vary from 6·9 to 29·2 pg/2C (10·6 and 13·4 pg/2C for L. sativus and L. cicera, respectively) (Ali et al., 2000, and references therein).

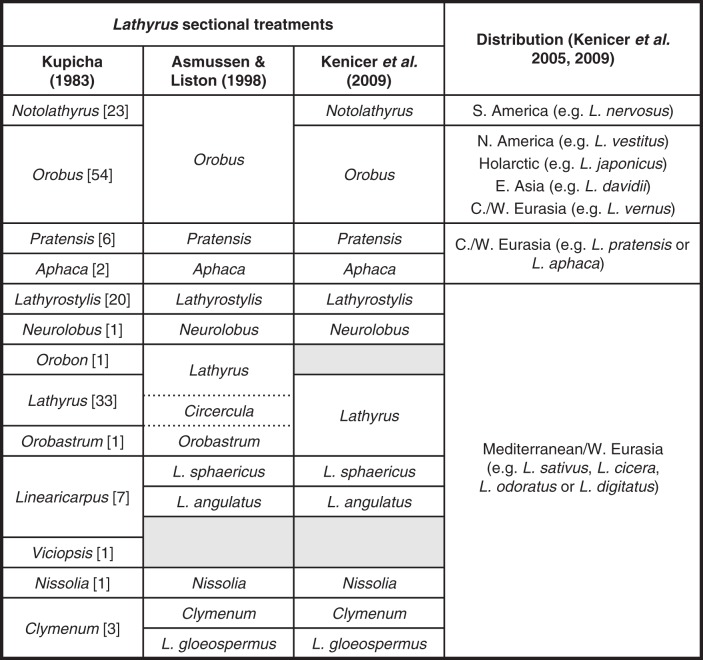

After several historically important treatments of their infrageneric classification, Kupicha (1983) recognized 13 sections within the genus Lathyrus based on morphological studies (Fig. 1). This same author hypothesized the origin of Lathyrus in the Old World at high altitudes, during the Cretaceous or early Tertiary periods, as an inhabitant of the Boreal–Tertiary woodland flora. This primitive ancestral stock must have migrated in Europe to the Mediterranean region and to the North American continent via Greenland or from Asia to Alaska. Later, by the end of the Tertiary period, primitive Lathyrus ancestors migrated from North to South America. Therefore, similarities between South American and Mediterranean/Irano-Turanian Lathyrus sp. would be, according to this author, due to parallel evolution.

Fig. 1.

Sectional treatments and world distribution of Lathyrus. Numbers of species are given in square brackets. Shaded areas represent groups not studied. Adapted from Kenicer et al. (2005, 2009).

Later on, Asmussen and Liston (1998) performed the first phylogenetic study using molecular data on both Eurasian and New World Lathyrus species. These authors used chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) characters [cpDNA-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)] to test the monophyly and relationships of Kupicha's Lathyrus sections, suggesting that some of these sections should be combined in order to form monophyletic groups (Fig. 1). Agreement with Kupicha's classification was otherwise very good (Kenicer et al., 2009). For instance, these cpDNA-RFLP parsimony analyses supported the North American origin of the South American Lathyrus species, earlier suggested by Kupicha (1983).

A later study based on amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (Badr et al., 2002) confirmed the monophyly of the section Lathyrus, but only for the species sampled and, unfortunately, in this study the sections Orobon and Orobastrum were not included. Recent molecular studies using sequence data for the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region and from cpDNA (Kenicer et al., 2005, 2009) support Kupicha's morphological-based classifications and resolved clades that were left unresolved by previous studies (i.e. Lathyrus) (Fig. 1). Nevertheless these analyses also questioned the monophyly of some other clades. For instance, further DNA data from other species are required before any firm systematic decision can be made within the Clymenum and the Linearicarpus sections sensu Kupicha. Kenicer et al. (2005) also suggested that Lathyrus, contrary to what was stated by Kupicha (1983), originated in the eastern Mediterranean region during the mid to late Miocene rather than dispersing into this area from northern Eurasian Eocene or Oligocene lineages. However, Kupicha's proposal that North American taxa derived from a primitive ancestral stock (from Eurasia) is well supported, with the Bering land bridge identified as the main route by which taxa have been exchanged between the two continents (Kenicer et al., 2005). Furthermore, these authors suggested that the relationship between the South American clade and the Eurasian species was not due to parallel evolution, but rather was the result of a long-distance dispersal from Eurasia.

Several other traits were surveyed for potential use in defining closely related Lathyrus species, especially among the cultivated species. Patterns of protein electrophoresis (El-Shanshoury, 1997; Przybylska et al., 1999; Emre, 2009) reflected the profound interspecific hybridization barriers in the genus Lathyrus, although L. sativus and L. cicera seem to be closer phylogenetically (Sáenz de Miera et al., 2008; Emre, 2009). However, compliance with the Kupicha classification was not complete. Different levels of diversity have been detected in the different species, reflecting their different perenniality and breeding systems (Ben Brahim et al., 2002). More recently, analyses of the differential composition of essential amino acids and seed oil fatty acids have proven useful to discriminate among the most closely related Lathyrus species (Pastor-Cavada et al., 2009a, 2011).

DIVERSITY IN THE LATHYRUS GENUS

Breeding efforts in any cultivated plant species rely on the identification and characterization of the germplasm resources of the crop and the study of its evolution (Yunus and Jackson, 1991). Detailed knowledge of its closest relatives and geographic origin (Schaefer et al., 2012) are important steps in this breeding process.

Gene pools

The gene pool concept originally proposed by Harlan and de Wet (1971), based on crossability and ease of gene transfer, was intended to provide a better classification of crop plants and their wild relatives. Exploitation of germplasm resources for the improvement of L. sativus currently concentrates on landrace material (Yunus and Jackson, 1991) by conventional means. The potential for a high level of improvement exists within this material since high variability has been found in the primary gene pool within L. sativus accessions, as will be discussed below. However, there is the potential for exploitation of related species.

Yunus and Jackson (1991) were the first to identify the gene pools of L. sativus, with L. amphicarpos and L. cicera placed in a restricted secondary gene pool and the other Lathyrus species in an extended tertiary gene pool. More recently, Heywood et al. (2007) extended this L. sativus secondary gene pool to include L. chrysanthus, L. gorgoni, L. marmoratus and L. pseudocicera, with which L. sativus can cross and produce ovules, and possible more remotely L. amphicarpos, L. blep-haricarpus, L. chloranthus, L. cicera, L. hierosolymitanus and L. hirsutus, with which L. sativus can cross and with which pods are formed (Table 1). The remaining species of the genus can be considered members of the tertiary gene pool.

Table 1.

Lathyrus sativus gene pools (Heywood et al., 2007)

| Primary gene pool | Secondary gene pool | Tertiary gene pool |

|---|---|---|

| Wild and cultivated L. sativus races | L. cicera | Other Lathyrus sp. |

| L. amphicarpus | ||

| L. chrysanthus | ||

| L. gorgoni | ||

| L. marmoratus | ||

| L. pseudocicera | ||

| L. blepharicarpus | ||

| L. choranthus | ||

| L. hierosolymitanus | ||

| L. hirsutus |

There is also a lot of interest in exploitation of secondary gene pool resources in L. odoratus to obtain new pigmentations and scents. Lathyrus odoratus has been successfully crossed with L. hirsutus, L. chlorantus (Khawaja, 1988) and L. belinensis (Hammet et al., 1994).

Germplasm collections

The most economically important Lathyrus species grown commercially are found in the section Lathyrus, and include L. sativus, L. cicera and L. odoratus. Although there are relatively few efforts being made throughout the world for the genetic improvement of these species compared with other crops, some important programmes exist that aim to improve its yield, quality and adaptability. All these breeding efforts require access to suitable genetic resources. Due to its importance as a survival food for some of the world's poorest people, yet recognizing the dangers that can be caused by excessive consumption, L. sativus was listed among the crops included in the multilateral system of access and benefit sharing under the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) (FAO, 2009). Some significant collections of cultivated and wild Lathyrus species have already been assembled and are maintained ex situ in a number of different institutes throughout the world. The largest collections are maintained by the Conservatoire Botanique National des Pyrénées et de Midi-Pyrénées (BP 70315) in France (4477 accessions) and by ICARDA in Syria (3239 accessions), both comprising about 50 % L. sativus. Details of other important ex situ Lathyrus collections are listed in Table 2. Co-ordinated international efforts to collect and conserve Lathyrus crop species have been initiated during the last decades, with the establishment of a ‘Lathyrus Genetic Resources Network’ (Mathur et al., 1998), and more recently with the development of a grass pea ex situ conservation strategy as part of the Global Crop Diversity Trust (Crop Trust, 2007). Both efforts focused on L. sativus, L. cicera and L. ochrus. Relatively large collections of L. cicera and L. odoratus exist (>800 accessions) in a number of countries due to its agricultural use, with many fewer accessions of other Lathyrus species (de la Rosa and Marcos, 2009; Rubiales et al., 2009; Gurung and Pang, 2011; Parsons and Mikic, 2011; Shehadeh et al., 2013).

Table 2.

Main Lathyrus germplasm collections

| Institute | Location | No. of accessions | W/C* | Ls/Lc† | Contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA) | Syria | 3239 | 45/54 | 53/6 | www.icarda.cgiar.org/ |

| Conservatoire Botanique National des Pyrénées et de Midi-Pyrénées (CBNPMP) | France | 4477 | NA | 53/18 | contact@cbnpmp.fr www.cbnpmp.fr |

| National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (NBPGR) | India | 2619 | 3/85 | 98/0·04 | www.nbpgr.ernet.in/ |

| Plant Genetic Resource Centre (PGRC), Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) | Bangladesh | 1841 | 0/100 | 100 % | www.bari.gov.bd/ |

| Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agraria (INIA) | Chile | 1424 | NA | NA | www.inia.cl/ |

| Ustymivka Experimental Station of Plant Production | Ukraine | 1215 | NA | NA | sluds@kot.poltava.ua |

| N.I. Vavilov All-Russian Scientifc Research Institute of Plant Industry | Russian Federation | 1207 | 43/30 | 74/23 | www.vir.nw.ru |

| Australian Grains Genebank | Australia | 1020 | 28/39 | 60/30 | www2.dpi.qld.gov.au/extra/asp/AusPGRIS/ |

| Plant Gene Resources of Canada (PGRC) | Canada | 840 | 10/90 | 93/0 | pgrc3.agr.gc.ca/ |

| Germplasm Resource Information Network (GRIN) United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) | USA | 505 | NA | 36/5 | www.ars-grin.gov/npgs/ |

| Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research (IPK) | Germany | 515 | 40/NA | 45/47 | www.ipk-gatersleben.de/en/ |

| Centro de Recursos Fitogenéticos (CRF) Instituto nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA) | Spain | 429 | NA | 20/60 | wwwx.inia.es/crf |

*W/C: % wild/% cultivated material.

†Ls/Lc: % Lathyrus sativus/% Lathyrus cicera accessions.

NA, information not available.

As we will describe below, several phenotypic and genotypic germplasm characterization studies have taken place using these collections. These studies are enhancing the use of germplasm collections in crop improvement via plant breeding while also aiding the management of collections themselves through an improved understanding of the relationships between accessions and underlying patterns of diversity (Davenport et al., 2004). However, the large sizes of many of these collections, either individually or collectively, complicate the characterization, evaluation and maintenance of the conserved germplasm, hindering their successful use (Odong et al., 2013).

In addition to the above-mentioned ex situ collections, in situ preservation is recommended. In situ genetic reserve conservation may be defined as ‘the location, designation, management and monitoring of genetic diversity in natural wild populations within defined areas designated for active, long-term conservation’ (Maxted et al., 1997). However, there has been very limited effort to conserve Lathyrus diversity in situ, and native populations are susceptible to genetic erosion or even extinction (Maxted and Bennett, 2001). Gap analysis studies of Lathyrus species to guide future collecting missions and in situ preservation efforts have been proposed (Shehadeh et al., 2013). A multi-genepool approach has been used by Maxted et al. (2012) for several legume genera including Lathyrus. This involved the collation of 61 081 unique geo-referenced Lathyrus records collected between 1884 and 2008.

Besides these co-ordinated conservation efforts, there is an urgent need to establish a global phenotyping and genotyping network for comprehensive and efficient characterization of Lathyrus germplasm for an array of target traits particularly for biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and nutritional and technological quality. Lathyrus descriptors (IPGRI, 2000) have been established as a result of the effort to define a set of common morphological traits, in order to have common tools focusing on the phenotyping of the genus. Those descriptors were mainly based on diversity observed for L. sativus, L. cicera and L. ochrus; however, they are also recommended for use for other Lathyrus species. This is expected to aid in effective identification and use of novel alleles for Lathyrus crop improvement.

Core collections

To unlock the genetic potential of these large collections, a general proposal is to construct smaller core collections to increase the efficiency of characterization and utilization, while preserving as much as possible the genetic diversity of the entire collection (Frankel, 1984; Brown, 1989). Frankel (1984) defined a core collection as a limited set of accessions representing, with minimum repetitiveness, the genetic diversity of a crop species and its wild relatives. These sub-sets have been reported for most legumes and have proven useful in identifying new sources of variation (Upadhyaya et al., 2011).

In this way, and for the time being, an initial representative core collection for grass pea could be developed using passport data, but also employing the existing characterization and evaluation data normally more available on L. sativus, L. cicera and L. amphicarpus. In a second stage, as in the approach proposed by Upadhyaya et al. (2011), the core collection would be evaluated for various detailed morpho-agronomic, genotypic and quality traits to select a sub-set of 10 % of accessions to form a mini-core collection. At both stages, standard clustering procedures would be used to separate groups of similar accessions combined with various statistical tests to identify the best representatives (Upadhyaya et al., 2011). On the other hand, accessions not included in core/mini-core collections would still be maintained as reserve collections for more in-depth study for specific traits and gene variants. Depending on the future progress of Lathyrus genetic engineering technology, other Lathyrus species besides those comprising its primary and secondary gene pool could also be considered as sources of novel genes for breeding.

However, insufficient efforts have been made in Lathyrus so far apart from the attempts of Shehadeh (2011) who compared several core sub-set selection strategies based on eco-geographical information. These authors also proposed the selection of alternative best-bet sets for particular traits (here named specific or thematic collections), through the Focused identification of Germplasm Strategy (FIGS). The FIGS approach is a trait-based and user-driven approach to select potentially useful germplasm for crop improvement. It was conceived to provide indirect evaluation of germplasm for specific traits, using, as a surrogate, the environment based on the hypothesis that the germplasm is likely to reflect the selection pressures of the environment in which it was originally sampled (Mackay et al., 2005). This is especially appealing for improvement of adaptive traits such as abiotic stress (heat and drought) resistance, which can be more directly correlated with the climatic data (maximum temperature and aridity index) from the collecting sites (Endresen et al., 2011).

Germplasm characterization

In order to achieve effective conservation and enhance the use of the germplasm collections, there is a need for detailed characterization of the existing diversity. Information regarding different levels of diversity in Lathyrus germplasm would help to identify sources of broadening improved breeding pools and in seeking genes and alleles that have not been tapped in modern breeding.

Diversity analysis through morphological phenotyping

By studying the morphological variation of a collection of Lathyrus accessions covering the known worldwide geographical distribution, Jackson and Yunus (1984) showed that L. sativus is differentiated into several distinct forms, primarily on the basis of flower colour, seed size, and size of leaves. In this way, they identified a clear distinction between the blue-flowered forms from South-west Asia, Ethiopia and the Indian sub-continent, and the white-and blue-flowered forms with white seeds that have a more western distribution (from the Canary Islands to the western ex-republics of the Soviet Union). This array of variation is undoubtedly the result of geographical separation as well as selection by man.

This grouping, of white-seeded with large seeds, originating mainly from Europe and North Africa, and coloured-seeded with relatively small seeds, originating mainly from Asia and Ethiopia, was also supported by Przybylska et al. (1998, 2000), based on quality analysis, and by Hanbury et al. (1999), based on agronomic testing. Those lines of Mediterranean/European origin were consistently higher yielding, with much larger seeds and later phenology (Hanbury et al., 1999). They also had lower ODAP content (Abd El Moneim et al., 2001). Preference for larger seeds in this area is common to other grain legumes such as lentil (Lens culinaris), chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and faba bean (Vicia faba), and is a product of human selection (Chowdhury and Slinkard, 2000). Similar studies on field evaluation of grass pea landraces, but in a more restricted germplasm study, where high variability in morphological and agronomical traits was detected, were also performed with Chilean (Tay et al., 2000), Ethiopian (Tadesse and Bekele, 2003a, b), Italian (Tavoletti et al., 2005), Indian (Kumari, 2001), Spanish (De la Rosa and Martín, 2001) and Slovak germplasm (Benková and Záková, 2001). In the majority of these studies, diversity among and within populations has been detected for several of the characterized traits (Table 3), indicative of high breeding potential in these materials.

Table 3.

Examples of Lathyrus diversity studies in morphological traits

| Traits | Germplasm | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Flower colour, seed and leaf size | L. sativus, wild sp. (worldwide) | Jackson and Yunus (1984) |

| Plant vigour, time to flowering, to end of flowering and to podding, physiological maturity, seed weight and yield | L. sativus, L. cicera (worldwide) | Hanbury et al. (1999) |

| Seed size, shape and colour, days to flowering | L. sativus (Chile) | Tay et al. (2000) |

| Time to maturity, plant height, first pod height of setting, plant dry weight, pods/plant, seeds/plant, seed weight and yield, lodging resistance | L. sativus (Slovakia) | Benková and Záková (2001) |

| Time to flowering, podding and maturity, pods/plant, seeds/pod, seed weight and yield | L. sativus (India) | Kumari (2001) |

| Phenological, plant, inflorescence and fruit Lathyrus IPGRI descriptors | L. sativus, L. cicera, ten other Lathyrus sp. (Spain) | de la Rosa and Martín (2001) |

| Time to flowering and maturity, pods/plant, plant height, seed weight, harvest index, leaflet and seed size, flower and seed colour | L. sativus (Ethiopia) | Tadesse and Bekele (2003a, b) |

| Stem height, leaflet length and width, pod height, pod length, seeds/pod, seed weight and yield | L. sativus (Italy) | Tavoletti et al. (2005) |

Diversity analysis through biochemical and molecular markers

Biochemical and molecular markers can be used to better document the organization of genetic diversity between possible parental materials of new breeding programmes. The high agronomical and morphological diversity within L. sativus germplasm is also found at the biochemical and molecular level. Considerable genetic diversity, as revealed by isozymes and molecular markers, exists in L. sativus throughout the world (Table 4). These markers are normally very efficient in distinguishing among different L. sativus genotypes. However, it was not always possible to associate genetic diversity with morphological or geographical diversity (Yunus et al., 1991; Tadesse and Bekele, 2001; Belaid et al., 2006; Vaz Patto et al., 2011). The lack of correlation between genetic diversity and the region of origin supports the idea that the natural distribution of L. sativus has been completely obscured by cultivation.

Table 4.

Examples of Lathyrus diversity studies in biochemical and molecular markers

| Marker type | Germplasm | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ODAP | L. sativus, L. cicera (worldwide) | Hanbury et al. (2000) |

| L. sativus (worldwide) | Abd El Moneim et al. (2001) | |

| L. sativus, L. cicera (worldwide) | Granati et al. (2003) | |

| L. sativus (Ethiopia) | Tadesse and Bekele (2003a) | |

| L. cicera (Iberian Peninsula) | Sánchez-Vioque et al. (2009) | |

| L. sativus (worldwide) | Kumar et al. (2011) | |

| L. sativus (central and southern Italy) | Piergiovanni et al. (2011) | |

| L. sativus, L. cicera (European) | Grela et al. (2010, 2012) | |

| Isozymes | L. sativus (worldwide) | Yunus et al. (1991) |

| L. sativus (worldwide) | Chowdhury and Slinkard (1997, 2000) | |

| L. sativus (Ethiopia) | Tadesse and Bekele (2001) | |

| L. sativus (worldwide) | Gutierrez-Marcos et al. (2006) | |

| Seed storage proteins | L. sativus, L. amphicarpos, L. blepharicarpus, L. cicera, L. gorgoni, L. marmoratus, L. pseudocicera, L. stenophyllus (worldwide) | Przybylska et al. (1998, 2000) |

| L. sativus (southern Italy) | Lioi et al. (2011) | |

| RAPD | L. sativus, L. cicera, L. latifolius, L. ochrus (worldwide) | Chtourou-Ghorbel et al. (2001) |

| L. sativus (worldwide) | Barik et al. (2007) | |

| ISSR | L. sativus, L. cicera, L. ochrus (worldwide) | Belaid et al. (2006) |

| AFLP | L. sativus (central Italy) | Tavoletti and Iommarini (2007) |

| L. sativus (southern Italy) | Lioi et al. (2011) | |

| L. sativus (Iberian Peninsula) | Vaz Patto et al. (2011) | |

| L. sativus- and Lotus japonicus-derived EST-SSR | L. sativus (southern Italy) | Lioi et al. (2011) |

| M. truncatula- and L. sativus-derived EST-SSR | L. sativus (Ethiopia) | Shiferaw et al. (2012) |

| Pisum sativum-and Medicago truncatula-derived ITAP and P. sativum-derived gSSR and EST-SSR | L. sativus, L. cicera (Iberian Peninsula) | Almeida et al. (2014) |

Chowdhury and Slinkard (2000), using a wide L. sativus germplasm collection, managed, however, to associate different levels of genetic diversity, measured by isozymes, with the different geographical origins. These authors identified the Near East and North Africa regions as those with the most isozyme variability, suggesting that the centre of diversity for L. sativus was this general area.

Also using a worldwide collection of L. sativus accessions from several different geographical origins, and the seed proteins, albumins (Przybylska et al., 1998) and globulins (Przybylska et al., 2000), it was possible to separate two groups of L. sativus accessions: white-seeded with large seeds, originating mainly from Europe and North Africa, and coloured-seeded with relatively small seeds, originating mainly from Asia and Ethiopia. Nevertheless, in a restricted study using only Southern Italian L. sativus germplasm, seed storage proteins were revealed to be unsuitable for detecting any variability among the studied landraces (Lioi et al., 2011). This may be an indication of the high level of genetic affinity among these landraces collected from a restricted geographical region.

PCR-based molecular markers, such as randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and intersimple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers, have also proven to be efficient in distinguishing between different L. sativus accessions and in assessing the within-species genetic variability (Chtourou-Ghorbel et al., 2001; Belaid et al., 2006; Barik et al., 2007). The presence of considerable intrapopulation variation among the L. sativus accessions, revealed in many of these diversity studies (Chowdhury and Slinkard, 1997; Gutierrez-Marcos et al., 2006), was greater than would have been expected given the predominantly autogamous breeding system of L. sativus. In fact, although L. sativus appears to be autogamous, outcrossing rates as high as 36 % have been recorded (Rahman et al., 1995; Chowdhury and Slinkard, 1997; Gutierrez-Marcos et al., 2006), which have implications in breeding and germplam maintenance.

Tavoletti and Iommarini (2007) evaluated the genetic diversity of a collection of L. sativus populations collected in central Italy using AFLPs. Two main clusters were found: one included large-seeded populations from farms and the second included small-seeded populations, cultivated in market-oriented farms. AFLP markers have also been used more recently in a Southern Italian collection of L. sativus and, even though the detected polymorphism was low, these populations were completely discriminated using 12 AFLP primer combinations (Lioi et al., 2011). The genetic diversity of a collection of Iberian L. sativus germplasm was also studied using AFLPs as a first step towards the selection of appropriate parental lines for the establishment of a disease-resistant cross-breeding scheme (Vaz Patto et al., 2011).

Molecular markers can also be developed using publicly available DNA sequencing data. Expressed sequence tags (ESTs) in public databases and cross-species transferable markers are considered to be a cost-effective means for developing sequence-based markers for less studied species (Ellwood et al., 2008). Both approaches have been applied to Lathyrus sp. with variable achievements. Molecular markers developed for closely related legume species have been shown to be transferable to L. sativus and L. cicera (Almeida et al., 2014). These included genomic and expressed sequence tag microsatellite (gSSR and EST-SSR) and intron-targeted amplified polymorphic (ITAP) markers, and were successfully used to discriminate within L. cicera and L. sativus accessions.

Shiferaw et al. (2012), using information on EST-SSRs derived from Medicago truncatula and also on publicly available (NCBI database) L. sativus EST sequences developed and validated polymorphic markers that were used successfully for exploring the genetic diversity of Ethiopian grass pea accessions. Lioi et al. (2011) developed SSR markers from publicly available (EMBL database) L. sativus and Lotus japonicus cDNA sequences and used them to study Southern Italian L. sativus accessions. In this case accessions were grouped into two clearly distinguishable clusters following a geographical pattern, but not consistent with the morphological data, AFLP- or SSR-based clustering. If we take into account the presence of polymorphism in the studies where this comparison could be performed, it can be concluded that more informative markers for genetic diversity studies were developed directly from L. sativus sequences than were transferable from M. truncatula or Lotus japonicus.

More recently, polymorphic EST-SSRs were developed from L. sativus sequence information available on a public database (NCBI database) (Sun et al., 2012) and from an enriched grass pea genomic library (Lioi and Galasso, 2013), as additional resources for grass pea genetic studies, but they are not yet exploited in diversity analysis.

Diversity on quality traits

Several preliminary studies to establish quality breeding approaches in Lathyrus sp. resulted in characterization of the quality diversity of germplasm collections (e.g. Granati et al., 2003). Lathyrus species are protein-rich legumes, the development of which into important food legumes has been hindered by the presence of ODAP, which, if consumed in large quantities for extended periods, can cause irreversible paralysis (Lambein and Kuo, 2009). The reduction in ODAP levels in L. sativus breeding has been the emphasis for a long time (Kumar et al., 2011; Girma and Korbu, 2012; Hillocks and Maruthi, 2012). No L. sativus or L. cicera accession is ODAP free, although in several lines the ODAP content can be significantly low. This appears to be species related, since the average ODAP content of L. cicera is generally lower than that of L. sativus (Hanbury et al., 2000; Abd El Moneim et al., 2001; Kumar et al., 2011). Variation of ODAP content, in a range from 0·02 to 2·59 %, has been reported in L. sativus (Granati et al., 2003; Tadesse and Bekele, 2003a; Grela et al., 2010, 2012; Piergiovanni et al., 2011) and from 0·09 to 0·49 % in L. cicera seeds (Granati et al., 2003; Sánchez-Vioque et al., 2009).

Selection for high yield and low ODAP can be practised simultaneously for L. sativus improvement. Most of the initial progress in the development of cultivars low in ODAP was by direct selection from landraces and lines with a worldwide origin, and several improved grass pea cultivars have been released as the result of various national and international breeding initiatives (Ali-Bar, Ceora, Gurbuz 1, Wasie, Prateek, Mahateora, Ratan, Bari Khesari 1 and 2, and Bina Khesari 1, all with an ODAP content <0·1 %) (summarized by Abd El Moneim et al., 2001; Kumar et al., 2011). Similarly, improved cultivars with low ODAP have been released, such as Chalus (Hanbury and Siddique, 2000).

This strategy of prioritizing reduction of ODAP content in breeding programmes is under debate today. First, although a number of cultivars with low ODAP have been released, the long-term results of these efforts are frequently questioned because ODAP content is highly influenced by climatic and edaphic conditions, with strong genotype × environment effects (Fikre et al., 2011; Jiao et al., 2011; Girma and Korbu, 2012). Water stress can double the toxin content in the plant (Hanbury et al., 1999) and there are indications that zinc fertilization can reduce the toxin accumulation (Lambein et al., 1994), although the mechanism by which the ODAP content may be reduced by added zinc is not known (Abd El-Moneim et al., 2010).

This long-term breeding priority did not take into consideration that ODAP in itself does not seem to be a problem when grass pea is consumed as part of a balanced diet, in which case grass pea is harmless to both humans and animals (Lambein and Kuo, 2009). Also, risks of overconsumption can be reduced by the fortification of grass pea with cereals rich in sulfur amino acids and condiments rich in antioxidants, such as onion, garlic and ginger (Getahun et al., 2003, 2005). In addition to this, seeds can be partly detoxified by various food processing methods, as reviewed by Kumar et al. (2011). Therefore, it seems clear that the widespread school of thought held 50 years ago of the vital need to reduce the ODAP content in Lathyrus seeds by breeding does not exist today. Even with the possibility of its toxicity, we should not neglect the potential benefits of ODAP. For instance, there is the prospect of using ODAP as a haemostatic agent during surgery (Lan et al., 2013). ODAP is not only produced by several Lathyrus sp. seeds, it is also present in the longevity-promoting ginseng root (Kuo et al., 2003), where, under the name Dencichine, it is known for its haemostatic property to stop bleeding (Lan et al., 2013).

In addition, there is the hypothesis that nitriles are the causative agents of neurolathyrism rather than ODAP (Llorens et al., 2011). However, nitriles too, even though they are toxic, can have some benefits. For instance, β-aminopropionitrile (β-APN) inhibits the cross-linking of collagen and is the cause of osteo-lathyrism, but has a number of pharmacological applications. β-APN has the potential for the control of silicotic pulmonary fibrosis (Levene et al., 1967); for the control of unwanted scar tissue in humans (Harrison et al., 2006); and for diminishing the metastatic colonization potential of circulating breast cancer cells (Bondareva et al., 2009). β-APN is a reagent used as an intermediate in the manufacture of β-alanine and pantothenic acid. Most reports on β-APN refer to L. odoratus. Genetic variation for content in other Lathyrus germplasm has not been explored.

Another recent paradigm shift in the perception of the L. sativus research is its content of homoarginine, which is an alternative substrate for nitric oxide biosynthesis (Rao, 2011). Nitric oxide is well recognized for its role in cardiovascular physiology and general well-being, and thus a daily dietary intake of homoarginine through small quantities of L. sativus may have advantages and deserves to be exploited. The activation of protein kinase C (PKC) by ODAP adds a new dimension for investigating its therapeutic potentials in such areas as Alzheimer's disease, hypoxia and the long-term potentiation of neurons essential for memory (Rao, 2011). Genetic variation for homoarginine content in L. sativus germplasm has been identified (Piergiovanni and Damascelli, 2011). Also, Lathyus spp. have potential for use as functional foods as the antioxidant activity of their polyphenols is higher than that of other legumes such as chickpea, lupin (Lupinus sp.) and soybean (Glycine max) (Pastor-Cavada et al., 2009b). Another potential beneficial application of L. sativus seeds it to ameliorate diabetic symptoms, as they possess glycosylphosphatidylinositol with insulin-mimetic activity (Pañeda et al., 2001).

Diversity in stress resistance

Many more reports exist on the biotic stress resistance evaluation of Lathyrus germplasm collections than on abiotic stress evaluations. Lathyrus sativus and L. cicera accessions of Iberian origin have been screened for resistance against powdery mildew and rust fungi (Vaz Patto et al., 2006a, b, 2007, 2009; Vaz Patto and Rubiales, 2009, 2014) and against the parasitic weed Orobanche crenata (Fernández-Aparicio et al., 2009, 2012; Fernández-Aparicio and Rubiales, 2010), identifying a wide range of levels of resistance. Moderate levels of resistance to powdery mildew in L. sativus have also been reported in India and Syria (Campbell et al., 1994; Robertson and Abd El-Moneim, 1996; Asthana and Dixit, 1998). Powdery mildew is among the major diseases affecting L. sativus (Campbell et al., 1994) and L. odoratus crops (Cook and Fox, 1992), and rusts are important diseases of L. sativus in north-western Ethiopia (Campbell, 1997). However, insufficient information is often available on the identity of the fungus. Powdery mildew that infects Lathyrus is believed to be mainly Erysiphe pisi, but it might be that several other species are able to infect Lathyrus sp., as recently found in pea (Fondevilla et al., 2013). The existence of specialized forms and races is still unclear, but a different ability to infect different plant species has been reported. Cook and Fox (1992) reported that a strain of E. pisi collected on L. odoratus was able to infect faba bean but not pea, whereas a different strain collected on L. latifolius was able to infect pea and faba bean. Similarly, rust in Lathyrus sp. is believed to be caused by both Uromyces pisi and U. viciae-fabae (Barilli et al., 2011, 2012).

Resistance to, or escape from, the parasitic weed O. crenata has also been identified in L. sativus and L. cicera germplasm (Fernández-Aparicio et al., 2009, 2012; Fernández-Aparicio and Rubiales, 2010). High levels of resistance to O. crenata have been reported in the species L. ochrus and L. clymenum (Sillero et al., 2005). Other relevant reports include resistance to Mycosphaerella pinodes (Robertson and Abd El-Moneim, 1996; Gurung et al., 2002), Fusarium oxysporum (Benková and Záková, 2001) and Cercospora pisi-sativae (Mishra et al., 1986) in L. sativus germplasm; to Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae in L. cicera germplasm (Martín-Sanz et al., 2012); and to the northern root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne hapla) in L. latifolius, L. sylvestris and L. hirsutus (Rumbaugh and Griffin, 1992). All these reports are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Examples of Lathyrus diversity studies in biotic stress resistance

| Stress | Germplasm | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cercospora pisi-sativae | L. sativus | Mishra et al. (1986) |

| Meloidogyne hapla (root knot nematode) | L. latifolius, L. sylvestris, L. hirsutus | Rumbaugh and Griffin (1992) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | L. sativus (Slovakia) | Benková and Záková (2001) |

| Mycosphaerella pinodes | L. sativus (worldwide) | Gurung et al. (2002) |

| Erysiphe pisi (powdery mildew) | L. sativus, L. cicera (India, Syria, Iberian Peninsula) | Campbell et al. (1994); Robertson and Abd El-Moneim (1996); Asthana and Dixit, (1998); Vaz Patto et al. (2006a, 2007) |

| Uromyces pisi (rust) | L. sativus, L. cicera (Iberian Peninsula) | Vaz Patto and Rubiales (2009); Vaz Patto et al. (2009) |

| Orobanche crenata (broomrape) | L. sativus, L. cicera, eight other Lathryrus sp. (worldwide) | Sillero et al. (2005); Fernández-Aparicio et al. (2009, 2012); Fernández-Aparicio and Rubiales (2010) |

| Pseudomonas syringae | L. cicera (Iberian Peninsula) | Martín-Sanz et al. (2012) |

In relation to Lathyrus abiotic stress resistance screening, the lack of methodologies to identify resistant genotypes has hampered the proper exploitation in breeding of Lathyrus sp. As a result, knowledge of the mechanisms underlying this resistance to environmental injuries is also missing. The effects of drought and salt stress on different Lathyrus sp. morphological and physiological traits have been studied with the objective of developing the missing efficient discrimination methods applicable to large germplasm screenings. Using a critical salt-induced stress treatment or the chlorophyll a fluorescence transient, several L. sativus salt- and drought-resistant genotypes, respectively, have been identified (Talukdar, 2011; Silvestre et al., 2014).

PROSPECTS FOR LATHYRUS DIVERSITY ANALYSIS AND USE IN BREEDING

Conserved plant genetic resources are essential to meet the current and future needs of crop improvement programmes. However, progress in Lathyrus breeding has been slow due to the dispersal of the few available resources and evaluation efforts among several scattered germplasm collections, plus the modest molecular and biotechnological breeding tools currently in existence. More efficient and faster breeding approaches are needed on this neglected but promising, underutilized species.

Marker development for diversity analysis and for marker-assisted selection

Although there has been encouraging recent growth of available genomic information in the Lathyrus genus, these resources are still modest when compared with other legume crops such as pea. As mentioned before in this review, several neutral DNA marker systems have been applied successfully in Lathyrus diversity studies. However, this success has not been translated into gene discovery or development of trait-associated markers for marker-assisted selection (MAS) in Lathyrus breeding.

There is one report of an L. sativus molecular marker linkage map developed to identify genomic regions linked to agronomically important traits, ascochyta blight resistance (Skiba et al., 2004). Also, there is no subsequent report on the use of the detected associated markers in breeding for resistance in Lathyrus. Moreover, this linkage map was not adequately saturated with markers, presenting numerous gaps and short linkage groups (Vaz Patto et al., 2006b); due to the lack of anchor markers, it could not be aligned and compared with other legume species linkage maps. Earlier studies indicated that extensive genome conservation based on comparative genetic mapping was exhibited by members of the legume Papilionoideae subfamily (such as Pisum, Lens, Vicia or Cicer) (Zhu et al., 2005). There is an urgent need to develop a more comprehensive genetic map for Lathyrus, with localization of useful genes and quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for MAS and with the possibility of alignment with other species in a comparative mapping approach.

The inclusion of cross-amplified anchor markers needs to be addressed to allow comparative mapping with other related legume species, opening the way for using Lathyrus as a source of interesting traits for other related species, and vice versa. Genomic and EST microsatellites were the most commonly attempted cross-species amplification marker systems in Lathyrus, but ITAP, RGA and DR genes have been used on these cross-amplification studies involving Lathyrus sp. (see above). Some of these marker systems, like microsatellites, have an additional advantage for linkage map development, since they are co-dominant markers. The incorporation of co-dominant markers will be very important for a correct estimation of genetic distances among markers in repulsion phase (Vaz Patto et al., 2011).

As previously mentioned above, not only cross-amplifiable markers from other legume species are being used in Lathyrus genetic studies. Lathyrus EST are being made available in public databases, in particular for L. sativus and L. odoratus, and these are now being used to develop molecular markers associated with coding DNA. Very recently, cDNA libraries have also been developed for L. cicera and EST-SSR markers identified (Almeida et al., 2011). This marker system generally has a high degree of sequence conservation and may potentially be more transferable among species, thus facilitating comparative genomic mapping (Vaz Patto et al., 2006b).

With the development of high-throughput and dense genotyping, the assessment of the correlation between phenotype and genotype, needed for the development of MAS approaches, has shifted from focusing on two parental lines differing strongly in phenotype to populations of unrelated individuals. Association mapping panels by sampling more genetic diversity can take advantage of many more generations of recombination and avoid the time-consuming generations of crosses (Morrell et al., 2012). High-throughput genotyping associated with a core collection evaluation will facilitate trait dissection and gene discovery through association mapping as well as characterization of genetic structure (Cobb et al., 2013). That is why it would be so important to concentrate the evaluation efforts on to a core sub-set collection representative of all the existing diversity, but of a manageable size.

Other biotechnological advances

In contrast to the development of, and now initiated use of different molecular markers with breeding objectives, other biotechnological advances conceived particularly for functional studies are not currently used on Lathyrus breeding.

Expression analysis studies were initially performed on L. sativus inoculated with Mycosphaerella pinodes using a limited number of 29 ESTs representing genes coding for enzymes and proteins involved in different levels of defence (Skiba et al., 2005). Some of the Lathyrus EST libraries previously mentioned in this review are now being developed not only for identifying molecular markers useful for the construction of high-density genetic linkage maps, but also for allowing expression analysis studies in order to identify and assess the function of putative genes thought to be involved in plant disease resistance responses. This is the case of rust resistance in L. sativus and L. cicera (Almeida et al., 2012). Next-generation sequencing technologies have also been recently applied to the L. sativus–Ascochyta sp., interaction through SuperSAGE quantitative gene expression profiling (Almeida et al., 2013). With this approach, it was possible to identify >3000 (P < 0·05) overexpressed or 900 (P < 0·05) underexpressed transcripts during the first 24 h after inoculation between infected and control tissue, opening the way to a powerful route of identification of candidate resistance genes and the study of resistance gene networks in L. sativus.

Gurung and Pang (2011) have recently prioritized the future construction of Lathyrus EST libraries from developing pods and seeds to achieve representation of reproductive tissues. In addition, these authors have called attention to the difficulties of proof-of-function studies of putative Lathyrus genes via overexpression, deletion or silencing due to the non-existence of a widely employed transformation system (only one event, reported by Barik et al., 2005) or a broadly applicable virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) reverse genetics approach, until now only reported for L. odoratus (Grønlung et al., 2008). Likewise, the reduced size of the presently available mutant populations does not provide the opportunity to study the effects of gene deletions/silencing through targeting-induced local lesions in genome (TILLING) approaches (Gurung and Pang, 2011).

Mutation breeding has been employed on several occasions to create additional variability in a range of traits, from plant growth habit to ODAP or methionine and lysine content (reviewed in Vaz Patto et al., 2011). Extensive variation was also detected in the course of tissue culture studies in several morphological traits, and has also been exploited in grass pea breeding (Kumar et al., 2011).

Embryo rescue and protoplast fusion protocols meant to increase the range of species in successful interspecific crosses (Ochatt et al., 2007) have unfortunately not been routinely used for grass pea improvement to date due to the difficult regeneration of hybrid plants. There are also survival problems with the recovered confirmed haploid plants that were reported in the haplo-diploidization method established from cultured isolated microspores in L. sativus (Ochatt et al., 2009), hindering its application in breeding. An in vitro protocol for fast production of advanced progeny that drastically shortens generation cycles has been developed in L. sativus (Ochatt et al., 2004). Over three generations per year can be obtained instead of the normal two, allowing a faster progress in L. sativus improvement. However this approach is only applicable when few seeds/plant are intended, as in single-seed descendant breeding schemes.

CONCLUSIONS

Today, due to the deluge of low-cost genomic information, phenotyping is quickly emerging as the major operational bottleneck and funding constraint of genetic analysis (Cobb et al., 2013). Consequently, after overcoming the problem of availability of appropriate germplasm resources to address specific questions through the establishment of a core collection, further emphasis should be placed on overcoming the shortage of high-quality phenotypic information to associate with the high-throughput genotyping information.

We propose that future international efforts on L. sativus and L. cicera improvement should concentrate on the development of publicly available joint core collections, and on its high-resolution genotyping. This will be critical for permitting a decentralized phenotyping, where multiple researchers can interrogate the same genetic materials, phenotyping in environments and with technology and analytical expertise that are uniquely available to different research groups (Cobb et al., 2013). Such co-ordinated international effort is sure to translate into more efficient and faster breeding approaches which are especially needed for such neglected but promising, underutilized species.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge K. P. Colleary, Ed.D., for English revision of the manuscript, and the financial support of Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal, through grants #PEst-OE/EQB/LA0004/2011 and #PTDC/AGR-GPL/103285/2008 and Research Contract by the Ciência 2008 program (to M.C.V.P.). This research was also funded by FP7-ARIMNet-MEDILEG project and by Spanish project AGL2011-22524. Sponsorship by the Annals of Botany to D.R. to give a key lecture at the 1st Legume Conference at Novi Sad, Serbia is also acknowledged.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abd El, Moneim AM, van Dorrestein B, Baum M, Ryan J, Vejiga G. Role of ICARDA in improving the nutritional quality and yield potential of grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.) for subsistence farmers in dry areas. Lathyrus Lathyrism Newsletter. 2001;2:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El, Moneim AM, Nakkoul H, Masri S, Ryan J. Implications of zinc fertilization for ameliorating toxicity (neurotoxin) in grasspea (Lathyrus sativus) Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology. 2010;12:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ali HBM, Meister A, Schubert I. DNA content, rDNA loci, and DAPI bands reflect the phylogenetic distance between Lathyrus species. Genome. 2000;43:1027–1032. doi: 10.1139/g00-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allkin R, Goyder DJ, Bisby FA, White RJ. Names and synonyms of species and subspecies in the Vicieae. Issue 3. Southampton, UK: Vicieae Database Project, Southampton University; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida NF, Leitão ST, Rotter B, Winter P, Rubiales D, Vaz Patto MC. Proceedings of the 9th Plant Genomics European Meeting (Plant GEM) Istanbul, Turkey: 2011. Development of molecular tools for Lathyrus cicera using normalized cDNA libraries; pp. 4–7. May 2011, p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida NF, Leitão ST, Rotter B, Winter P, Rubiales D, Vaz Patto MC. Proceedings of the VI International Conference on Legume Genetics and Genomics (VI ICLGG) Hyderabad, India: 2012. Differential expression in Lathyrus sativus and Lathyrus cicera transcriptomes in response to rust (Uromyces pisi) infection; p. 271. 2–7 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida NF, Leitão ST, Rotter B, Winter P, Rubiales D, Vaz Patto MC. Proceedings of the First Legume Society Conference 2013: A Legume Odyssey. Novi Sad, Serbia, 9–11 May 2013, p: 2013. Transcriptional profiling of grass pea genes differentially regulated in response to infection with Ascochyta pisi; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida NF, Leitão ST, Caminero C, Torres AM, Rubiales D, Vaz Patto MC. Transferability of molecular markers from major legumes to Lathyrus spp. for their application in mapping and diversity studies. Molecular Biology Reports. 2014;41:269–283. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2860-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmussen CB, Liston A. Chloroplast DNA characters, phylogeny, and classification of Lathyrus (Fabaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1998;85:387–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthana AN, Dixit GP. Utilization of genetic resources in Lathyrus. In: Mathur PN, Rao VR, Arora RK, editors. Lathyrus Genetic Resources Network. Proceedings of the IPGRI-ICARDAICAR Regional Working Group Meeting. Vol. 1997. New Delhi, India: 1998. pp. 64–70. 8–10 December. [Google Scholar]

- Badr A, El Shazly H, El Rabey H, Watson LE. Systematic relationships in Lathyrus sect. Lathyrus (Fabaceae) based on amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) data. Canadian Journal of Botany. 2002;80:962–969. [Google Scholar]

- Barik DP, Mohapatra U, Chand PK. Transgenic grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.): factors influencing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and regeneration. Plant Cell Reports. 2005;24:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s00299-005-0957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barik DP, Acharya L, Mukherjee AK, Chand PK. Analysis of genetic diversity among selected grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.) genotypes using RAPD markers. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. 2007;62c:869–874. doi: 10.1515/znc-2007-11-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barilli E, Satovic Z, Sillero JC, Rubiales D, Torres AM. Phylogenetic analysis of Uromyces species infecting grain and forage legumes by sequence analysis of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer region. Journal of Phytopathology. 2011;159:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Barilli E, Moral A, Sillero JC, Rubiales D. Clarification on rust species potentially infecting pea (Pisum sativum L.) crop and host range of Uromyces pisi (Pers.) Wint. Crop Protection. 2012;37:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Belaid Y, Chtourou-Ghorbel N, Marrakchi M, Trifi-Farah N. Genetic diversity within and between populations of Lathyrus genus (Fabaceae) revealed by ISSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2006;53:1413–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Brahim N, Salhi A, Chtourou N, Combes D, Marrakchi M. Isozymic polymorphism and phylogeny of 10 Lathyrus species. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2002;49:427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Benková M, Záková M. Evaluation of selected traits in grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.) genetic resources. Lathyrus Lathyrism Newsletter. 2001;2:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bondareva A, Downey CM, Ayres F, et al. The lysyl oxidase inhibitor, beta-aminopropionitrile, diminishes the metastatic colonization potential of circulating breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005620. e5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AHD. Core collections: a practical approach to genetic resources management. Genome. 1989;31:818–824. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón FJ, Vigil MF, Nielsen DC, Benjamin JG, Poss DJ. Water use and yields of no-till managed dryland grasspea and yellow pea under different planting configurations. Field Crops Research. 2012;125:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CG. Rome, Italy: Gatersleben/International Plant Genetic Resources Institute; 1997. Grass pea. Lathyrus sativus L. Promoting the conservation and use of under-utilized and neglected crops. 18. Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CG, Mehra RB, Agrawal SK, et al. Current status and future strategy in breeding grass pea (Lathyrus sativus) Euphytica. 1994;73:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury MA, Slinkard AE. Natural outcrossing in grasspea. Journal of Heredity. 1997;88:154–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury MA, Slinkard AE. Genetics of isozymes in grasspea. Journal of Heredity. 2000;91:142–145. doi: 10.1093/jhered/91.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chtourou-Ghorbel N, Lauga B, Combes D, Marrakchi M. Comparative genetic diversity studies in the genus Lathyrus using RFLP and RAPD markers. Lathyrus Lathyrism Newsletter. 2001;2:62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb JN, DeClerck G, Greenberg A, Clark R, McCouch S. Next-generation phenotyping: requirements and strategies for enhancing our understanding of genotype–phenotype relationships and its relevance to crop improvement. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2013;126:867–887. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2066-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RTA, Fox RTV. Erysiphe pisi var. pisi on faba beans and other legumes in Britain. Plant Pathology. 1992;41:506–512. [Google Scholar]

- Crop Trust. Global Crop Diversity Trust strategy for the ex stu conservation of Lathyrus (grass pea), with special reference to Lathyrus sativus, L. cicera, L. ochrus: 2007 http://www.croptrust.org/documents/cropstrategies/grasspea.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya BS. Seed morphology as an indicator for low neurotoxin in Lathyrus sativus. Qualitas Plantarum Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 1976;25:391–394. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport G, Ellis N, Ambrose M, Dicks J. Using bioinformatics to analyse germplasm collections. Euphytica. 2004;137:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa L, Marcos T. Genetic resources at the CRF-INIA, Spain: collection, conservation, characterization and documentation in Lathyrus species. Grain Legumes. 2009;54:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa L, Martín I. Morphological characterisation of Spanish genetic resources of Lathyrus sativus L. Lathyrus Lathyrism Newsletter. 2001;2:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Durieu P, Ochatt SJ. Efficient intergeneric fussion of pea (Pisum sativum L.) and grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) protoplasts. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2000;51:1237–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood SR, Phan HTT, Jordan M, et al. Construction of a comparative genetic map in faba bean (Vicia faba L.); conservation of genome structure with Lens culinaris. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:380. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shanshoury A. The use of seed proteins revealed by SDS–PAGE in taxonomy and phylogeny of some Lathyrus species. Biologia Plantarum. 1997;39:553–559. [Google Scholar]

- Emre I. Electrophoretic analysis of some Lathyrus L. species based on seed storage proteins. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2009;56:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Endresen DTF, Street K, Mackay M, Bari A, De Pauw E. Predictive association between biotic stress traits and eco-geographic data for wheat and barley landraces. Crop Science. 2011;51:2036–2055. [Google Scholar]

- Enneking D. The nutritive value of grasspea (Lathyrus sativus) and allied species, their toxicity to animals and the role of malnutrition in neurolathyrism. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49:694–709. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO. International treaty on plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2009. (accessible at ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/011/i0510e/i0510e.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aparicio M, Rubiales D. Characterisation of resistance to crenate broomrape (Orobanche crenata Forsk.) in Lathyrus cicera L. Euphytica. 2010;173:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aparicio M, Flores F, Rubiales D. Field response of Lathyrus cicera germplasm to crenate broomrape (Orobanche crenata) Field Crops Research. 2009;113:321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aparicio M, Flores F, Rubiales D. Escape and true resistance to crenate broomrape (Orabanche crenata Forsk.) in grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) germplasm. Field Crops Research. 2012;125:92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fikre WA, Negwo T, Kuo YH, Lambein R. Climatic, edaphic and altitudinal factors affecting yield and toxicity of Lathyrus sativus grown at five locations in Ethiopia. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondevilla S, Chattopadhyay C, Khare N, Rubiales D. Erysiphe trifolii is able to overcome er1 and Er3, but not er2, resistance genes in pea. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2013;136:557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel OH. Genetic perspective of germplasm conservation. In: Arber W, Limensee K, Peacock WJ, Stralinger P, editors. Genetic manipulations: impact on man and society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Getahun H, Lambein F, Vanhoorne M. Neurolathyrism in Ethiopia: assessment and comparison of knowledge and attitude of health workers and rural inhabitants. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:1513–1524. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun H, Lambein F, Vanhoorne M, Van der Stuyft P. Food-aid cereals to reduce neurolathyrism related to grass-pea preparations during famine. Lancet. 2003;362:1808–1810. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14902-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun H, Lambein F, Vanhoorne M, Van der Stuyft P. Neurolathyrism risk depends on type of grass pea preparation and on mixing with cereals and antioxidants. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2005;10:169–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girma D, Korbu L. Genetic improvement of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus) in Ethiopia: an unfulfilled promise. Plant Breeding. 2012;131:231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Granati E, Bisignano V, Chiaretti D, Crinò P, Polignano GB. Characterization of Italian and exotic Lathyrus germplasm for quality traits. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2003;50:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Grela ER, Rybinski W, Klebaniuk R, Matras J. Morphological characteristics of some accessions of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus) grown in Europe and nutritional traits of their seeds. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2010;57:693–701. [Google Scholar]

- Grela ER, Rybinski W, Matras J, Sobolewska S. Variability of phenotypic and morphological characteristics of some Lathyrus sativus L. and Lathyrus cicera L. accessions and nutritional traits of their seeds. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2012;59:1687–1703. [Google Scholar]

- Grønlund M, Constantin G, Piednoir E, Kovacev J, Johansen IE, Lund OS. Virus-induced gene silencing in Medicago truncatula and Lathyrus odoratus. Virus Research. 2008;135:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung AM, Pang ECK. Lathyrus. In: Kole C, editor. Wild crop relatives: genomic and breeding resources, legume crops and forrages. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung AM, Pang ECK, Taylor PWJ. Examination of Pisum and Lathyrus species as sources of ascochyta blight resistance for field pea (Pisum sativum) Australasian Plant Pathology. 2002;31:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gusmao M, Siddique KHM, Flower K, Nesbitt H, Veneklaas EJ. Water deficit during the reproductive period of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) reduced grain yield but maintained seed size. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science. 2012;198:430–441. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Marcos JF, Vaquero F, Sáenz de Miera LE, Vences FJ. High genetic diversity in a world-wide collection of Lathyrus sativus L. revealed by isozymatic analysis. Plant Genetic Resources. 2006;4:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hammett KRW, Murray BG, Markham KR, Hallett IC. Interspecific hybridization between Lathyrus odoratus and L. belinensis. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 1994;155:763–771. [Google Scholar]

- Hanbury CD, Siddique KHM. Registration of ‘Chalus’ Lathryus cicera L. Crop Science. 2000;40 1199. [Google Scholar]

- Hanbury CD, Siddique KHM, Galwey NW, Cocks PS. Genotype–environment interaction for seed yield and ODAP concentration of Lathyrus sativus L. and L. cicera L. in Mediterranean-type environments. Euphytica. 1999;110:445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hanbury CD, White CL, Mullan BP, Siddique KHM. A review of the potential of Lathyrus sativus L. and L. cicera L. grain for use as animal feed. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2000;87:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JR, de Wet JMJ. Toward a rational classification of cultivated plants. Taxon. 1971;20:509–517. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison CA, Gossiel F, Bullock AJ, Sun T, Blumsohn A, Mac Neil S. Investigation of keratinocyte regulation of collagen I synthesis by dermal fibroblasts in a simple in vitro model. British Journal of Dermatology. 2006;154:401–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heywood V, Casas A, Ford-Lloyd B, Kell S, Maxted N. Conservation and sustainable use of crop wild relatives. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 2007;121:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Hillocks RJ, Maruthi MN. Grass pea (Lathyrus sativus): is there a case for further crop improvement? Euphytica. 2012;186:647–654. [Google Scholar]

- IPGRI. Descriptors for Lathryus spp. Rome: International Plant Genetic Resources Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MT, Yunus AG. Variation in the grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) and wild species. Euphytica. 1984;33:549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao CJ, Jiang JL, Ke LM, et al. Factors affecting β-ODAP content in Lathyrus sativus and their possible physiological mechanisms. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. Ancient and modern cultivation of Lathyrus ochrus (L.) DC. in the Greek islands. The Annual of the British School at Athens. 1992;87:211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kenicer GJ, Kajita T, Pennington RT, Murata J. Systematics and biogeography of Lathyrus (Leguminosae) based on internal transcribed spacer and cpDNA sequence data. American Journal of Botany. 2005;92:1199–1209. doi: 10.3732/ajb.92.7.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenicer G, Nieto-Blásquez EM, Mikić A, Smýkal P. Lathyrus – diversity and phylogeny in the genus. Grain Legumes. 2009;54:16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja HIT. A new interspecific Lathyrus hybrid to introduce the yellow flower character into sweet pea. Euphytica. 1988;37:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kislev ME. Origins of the cultivation of Lathyrus sativus and L. cicera (Fabaceae) Economic Botany. 1989;43:262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Bejiga G, Ahmed S, Nakkoul H, Sarker A. Genetic improvement of grass pea for low neurotoxin (β-ODAP) content. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49:589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V. Field evaluation of grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.) germplasm for its toxicity in the northwestern hills of India. Lathyrus Lathyrism Newsletter. 2001;2:82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YH, Bau HM, Rozan P, Chowdhury B, Lambein F. Reduction efficiency of the neurotoxin beta-ODAP in low-toxin varieties of Lathyrus sativus seeds by solid state fermentation with Aspergillus oryzae and Rhizopus microsporus var chinensis. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2000;80:2209–2215. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YH, Ikegami F, Lambein F. Neuroactive and other free amino acids in seed and young plants of Panax ginseng. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:1087–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00658-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupicha FK. The infrageneric structure of Lathyrus. Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. 1983;41:209–244. [Google Scholar]

- Lan G, Chen P, Sun Q, Fang S. Methods for treating hemorrhagic conditions. 2013 Patent US8362081B2. [Google Scholar]

- Lambein F, Kuo YH. Lathyrism. Grain Legumes. 2009;54:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lambein F, Haque R, Khan JK, Kebede N, Kuo YH. From soil to brain: zinc deficiency increases the neurotoxicity of Lathyrus sativus and may affect the susceptibility for the motorneurone disease neurolathyrism. Toxicon. 1994;32:461–466. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(94)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioi L, Galasso I. Development of genomic simple sequence repeat markers from an enriched genomic library of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) Plant Breeding. 2013;132:649–653. [Google Scholar]

- Lioi L, Sparvoli F, Sonnante G, Laghetti G, Lupo F, Zaccardelli M. Characterization of Italian grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.) germplasm using agronomic traits, biochemical and molecular markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2011;58:425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Levene CI, Bye I, Saffioti U. The effect of β-aminopropionitrile on silicotic pulmonary fibrosis in the rat. British Journal of Experimental Pathology. 1967;49:152–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorens J, Soler-Martín C, Saldaña-Ruíz S, Cutillas B, Ambrosio S, Boadas-Vaello P. A new unifying hypothesis for lathyrism, konzo and tropical ataxic neuropathy: nitriles are the causative agents. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay M, von Bothmer R, Skovmand B. Conservation and utilization of plant genetic resources – future directions. Czech Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding. 2005;41:335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Magee AM, Aspinall S, Rice DW, et al. Localized hypermutation and associated gene losses in legume chloroplast genomes. Genome Research. 2010;20:1700–1710. doi: 10.1101/gr.111955.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Sanz A, Palomo J, Pérez de la Vega M, Caminero C. Characterization of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae isolates associated with bacterial blight in Lathyrus spp. and sources of resistance. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2012;134:205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur PN, Ramanatha Rao V, Arora RK. Lathyrus genetic resources network: Proceedings of a IPGRI-ICARDA-ICAR regional working group meeting. 1998 NBPGR, IPGRI Office for South Asia, New Delhi, India. 8–10 December 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Maxted N, Bennett S. Plant genetic resources of legumes in the Mediterranean. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maxted N, Ford-Lloyd BV, Hawkes JG. Complementary conservation strategies. In: Maxted N, Ford-Lloyd BV, Hawkes JG, editors. Plant genetic conservation: the in situ approach. London: Chapman and Hall; 1997. pp. 20–55. [Google Scholar]

- Maxted N, Hargreaves S, Kell SP, et al. Temperate forage and pulse legume genetic gap analysis. Bocconea. 2012;24:115–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra RP, Kotasthane SR, Khare MN, Gupta OM, Tiwari SP. Screening of germplasm collections of Lathyrus spp. against Cercospora pisi-sativae f. sp. lathyri-sativae Mishra. Indian Journal of Mycology and Plant Pathology. 1986;16 302. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell PL, Buckler ES, Ross-Ibarra J. Crop genomics: advances and applications. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012;13:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrg3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochatt SJ, Sangwan RS, Marget P, Assoumou NY, Rancillac M, Perney P. New approaches towards the shortening of generation cycles for faster breeding of protein legumes. Plant Breeding. 2004;121:436–440. [Google Scholar]

- Ochatt SJ, Abirached-Darmency M, Marget P, Aubert G. The Lathyrus paradox: ‘poor men's diet’ or a remarkable genetic resource for protein legume breeding? In: Ochatt S, Jain SM, editors. Breeding of neglected and under-utilised crops, spices and herbs. Enfield, NH: Science Publishers; 2007. pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ochatt S, Pech C, Grewal R, Conreux C, Lülsdorf M, Jacas L. Abiotic stress enhances androgenesis from isolated microspores of some legume species (Fabaceae) Journal of Plant Physiology. 2009;166:1314–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odong TL, Jansen J, van Eeuwijk FA, van Hintum TJL. Quality of core collections for effective utilization of genetic resources review, discussion and interpretation. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2013;126:289–305. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1971-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]