Abstract

HIV susceptibility is heterogeneous, with some HIV-exposed but seronegative (HESN) individuals remaining uninfected despite repeated exposure. Previous studies in the cervix have shown that reduced HIV susceptibility may be mediated by immune alterations in the genital mucosa. However, immune correlates of HIV-exposure without infection have not been investigated in the foreskin. We collected sub-preputial swabs and foreskin tissue from HESN (n=20) and unexposed control (n=57) men undergoing elective circumcision. Swabs were assayed for HIV-neutralizing IgA, innate antimicrobial peptides, and cytokine levels. Functional T cell subsets from foreskin tissue were assessed by flow cytometry. HESN foreskins had elevated α-defensins (3027 vs. 1795 pg/ml, p=0.011) and HIV-neutralizing IgA (50.0 vs. 13.5% of men, p=0.019). Foreskin tissue from HESN men contained a higher density of CD3 T cells (151.9 vs. 69.9 cells/mm2, p=0.018), but a lower proportion of these were Th17 cells (6.12 vs. 8.04% of CD4 T cells, p=0.007), and fewer produced TNFα (34.3 vs. 41.8% of CD4 T cells, p=0.037; 36.9 vs. 45.7% of CD8 T cells, p=0.004). A decrease in the relative abundance of susceptible CD4 T cells and local TNFα production, in combination with HIV-neutralizing IgA and α-defensins, may represent a protective immune milieu at a site of HIV exposure.

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 (HIV) is primarily transmitted through unprotected sex. Despite the high global prevalence of HIV, transmission of the virus during insertive vaginal sex is both relatively inefficient and heterogeneous, with the estimated per-contact risk of female-to-male transmission ranging from 1/200 to 1/20001. To rationally design new tools to prevent HIV transmission we need to understand the mucosal determinants of transmission. Individuals who are regularly HIV exposed but seronegative (HESN) may provide important insights into the mucosal immune correlates of resistance to HIV infection.

A number of previous studies have examined these immune parameters in HESN individuals exposed to HIV through sero-discordant sexual relationships or commercial sex work (CSW). Mucosal secretions (cervical and salivary) from HESN individuals contain higher levels of several antimicrobial peptides and C-C chemokines that have been shown to have antiviral or HIV-neutralizing capacity in vitro. Upregulated antimicrobial proteins include the cathelicidin LL-372,3, α-defensins (human neutrophil peptides 1–3, HNP1–3)2,3, β-defensins (hBD2) 4,5, protease inhibitors6–8 (SLPI and trappin-2/elafin), and interferon-α (IFNα)9. Upregulated C-C chemokines include macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α)10, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)10, and regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES)9,11. Furthermore, cervico-vaginal secretions and saliva from HESN individuals may contain HIV-neutralizing IgA12,13, which was associated with a reduced risk of HIV acquisition in a prospective study14.

These data suggest that higher mucosal levels of certain innate/adaptive immune molecules may provide protection against HIV acquisition. However, some mucosal immune factors that neutralize HIV in vitro also activate or recruit HIV target cells, thereby negating any protective neutralizing effect of the peptide, or even increasing HIV susceptibility in vivo, as appears to be the case for LL-37 and α-defensins3,15,16. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that reduced immune activation at the site of HIV exposure may correlate with resistance to infection. Cervical secretions from HESN women in Nairobi contain lower levels of C-X-C chemokines and the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1a as compared to new (non-HESN) CSWs6. Furthermore, T cells from the blood and genital tract of HESN women have increased regulatory T cells (Tregs)17,18, lower CD4 T cell expression of the activation markers HLA-DR19,20 and CD3820,21, and reduced production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-17, IL-22, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα 22,23. Taken together, these studies suggest that relative resistance to HIV infection may require a delicate balance between the levels of antimicrobial peptides in genital secretions and of activated/highly susceptible target cells the mucosa.

Randomized trials of male circumcision have demonstrated that the foreskin is the main site of HIV acquisition in heterosexual men24–26, underlining the need to better characterize the immune correlates of HIV susceptibility in this anatomic site. Compared to blood, T cells in the foreskin produce more cytokines, express more CCR5, and are enriched for highly HIV-susceptible Th17 cells27. Additionally, foreskin tissue has been shown to produce several soluble peptides that have in vitro antiviral activity16. Therefore, we performed an investigator- blinded study to define the immune correlates of reduced HIV susceptibility in the foreskins of HESN men from Rakai, Uganda.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Participants were recruited from a longstanding community cohort in Rakai, Uganda28. HESN men (n=20; see Methods for definition) had been in a primary sexual relationship with an HIV-infected woman for a median of 5 years (range, 1–10 years; see Table 1). HESN men reported using condoms either “sometimes” (30%) or “never” (70%), and the median plasma viral load of the HIV-seropositive female partner was 3.74 log10 RNA copies/ml (range 1.62 – 5.22; Table 1). All HESN participants were HIV PCR negative at the time of the study. HESN men and HIV-unexposed control men did not differ in terms of age, condom use or the number of sexual partners in the last year. However, HESN men had a higher HSV-2 seroprevalence than unexposed controls (70 vs. 31.5%, p=0.004) and were more likely to report concurrent sexual relationships (3/20 vs. 0/57, p=0.016); therefore multivariate linear regression was used to control for HSV-2 status and concurrent sexual relationships in all subsequent analyses, and only adjusted p-values are reported. Of note, while concurrent sexual relationships were not associated (p<0.1) with any of the immunological parameters investigated in this study, a larger analysis of the effect of HSV-2 infection on foreskin T cell populations30 (which included a subset of the men described in the present work) previously found that HSV-2 was associated with increased CCR5 expression on foreskin CD4 T cells, but not with any other immune parameters investigated.

Table 1.

Behavioral and demographic characteristics of participants.

| HESN (n=20) | Unexposed (n=57) | sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | man | 33 (23–53) | 34 (22–51) | 0.419 |

| woman | 29 (20–41) | 29 (19–49) | 0.819 | |

| HSV-2 serology | 14/20 (70.0% | 17/54 (31.5%) | 0.004 | |

| Partner viral load (copies/ml) | 5,589 (42–165,288) | n/a | ||

| Partner CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 553 (295–1,592) | 1,152 (492–2,019) | <0.001 | |

| Length of HIV exposure (yrs) | 5 (0.5–15) | n/a | ||

| Condom use (%) | always | 1/20 (5.0%) | 0/57 (0.0%) | 0.114 |

| sometimes | 5/20 (25.0%) | 9/57 (15.8%) | ||

| not using | 14/20 (70.0%) | 48/57 (84.2%) | ||

| Sexual partners in past year |

single | 15/20 (75.0%) | 49/57 (86.0%) | 0.304 |

| multiple | 5/20 (25.0%) | 8/57 (14.0%) | ||

| Concurrent sexual partners (%) | 3/20 (15.0%) | 0/57 (0.0%) | 0.016 | |

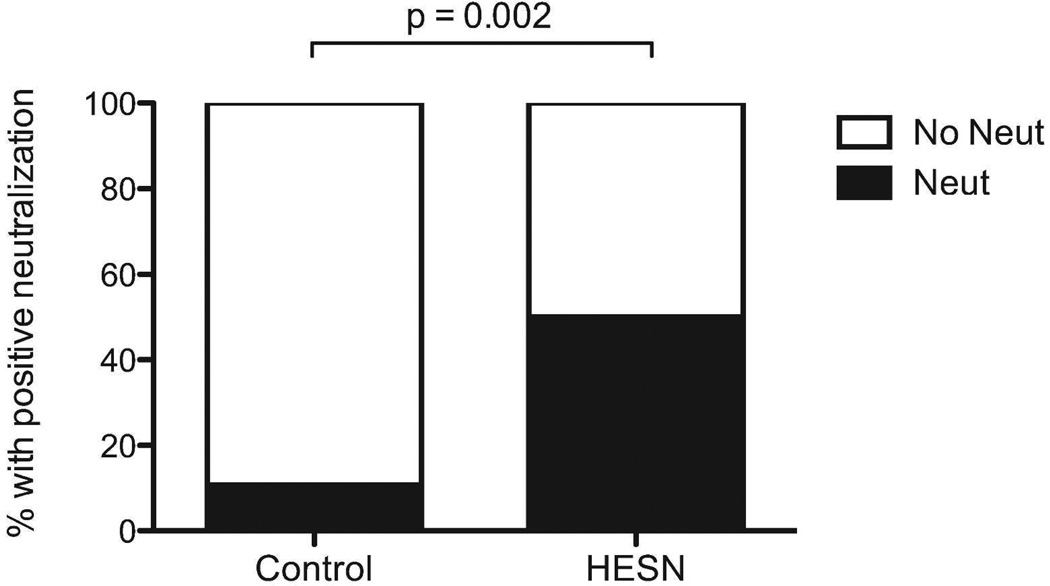

HIV neutralization by foreskin-derived IgA

The ability of purified sub-preputial IgA to neutralize infection of activated PBMCs by a primary clade C HIV isolate was then assessed by research personnel blinded to participant study group. Using a predefined cut-off of ≥67% neutralization compared to the reference sample, IgA purified from sub-preputial swabs of 9/18 (50%) HESN men was able to inhibit HIV infection of activated PBMC, while IgA from only 4/37 (10.8%) unexposed controls had this neutralizing capacity (Figure 2; prevalence risk ratio: 4.63; 95% CI: 3.00–6.26%; Fisher exact p=0.002). The absolute quantity of IgA in HESN samples was similar to that in controls (2146 pg/ml in controls vs. 1649 pg/ml in HESN, p=0.9), and a sensitivity analysis using an increased cut-off of ≥90% neutralization yielded similar results (neutralization seen in 9/18 HESN men vs. 2/37 control men, p<0.001). Within the HESN group, IgA neutralization capacity did not correlate with the quantity of IgA, female partner viral load, length of time of HIV exposure, or the presence of HIV-specific CD8 T cells in his blood or foreskin. Presence of HIV-neutralizing IgA also did not correlate with HSV-2 status or concurrent extramarital relationships (data not shown).

Figure 2. The ability of IgA isolated from the foreskin to neutralize HIV.

IgA was purified from foreskin secretions and incubated with a primary clade C viral isolate, which was subsequently challenged with PBMCs. The ability of IgA-treated virus to infect PBMCs was measured through p24 production. Capacity to neutralization HIV was defined as 67% less p24 production compared to reference sample. The proportion of men in each group with HIV-neutralizing IgA is shown (HESN n=18; Controls n=37).

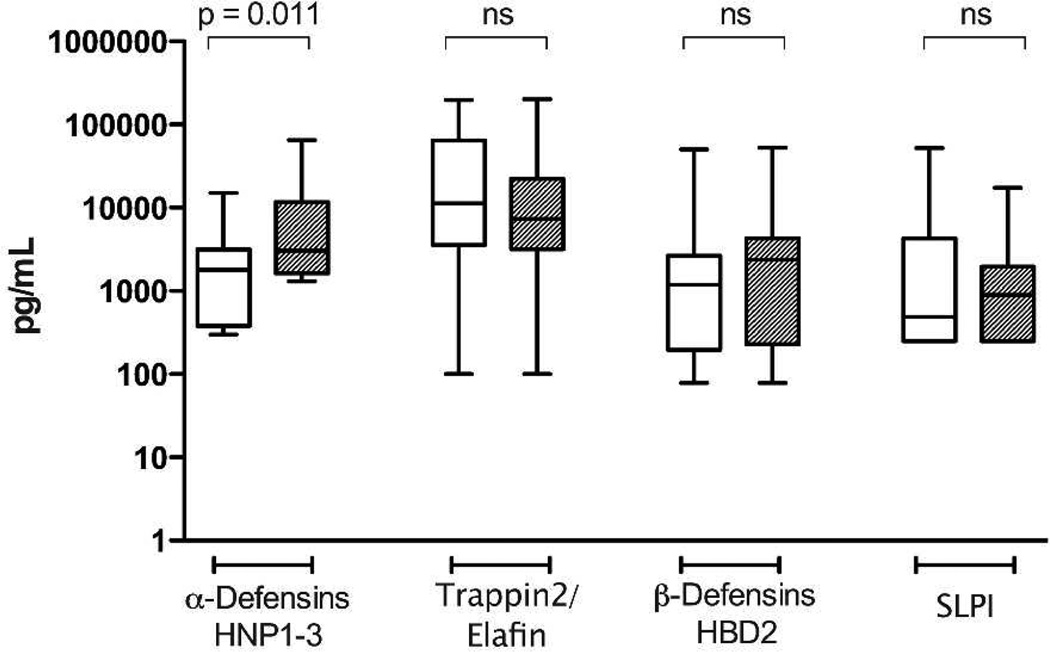

Preputial levels of soluble innate immune factors and cytokines

Levels of innate anti-microbial peptides were quantified in the IgA-depleted fraction of sub-preputial swab eluate. Levels of the innate antimicrobial peptides Trappin2/Elafin, HNP-1–3, HBD-2 and SLPI are shown in Figure 1. The α-defensins HNP 1–3 was present at a significantly higher level in swabs taken from the sub-preputial space of HESN men compared to controls (3027 pg/ml vs. 1795 pg/ml; adjusted p=0.011); which among HESN men correlated with the presence of neutralizing IgA (correlation coefficient 0.503, p=0.033) but not partner viral load or length of HIV exposure. To ensure that IgA neutralization was not a result of HNP-1–3, IgA fractions were also analyzed for presence of HNP-1–3: no HNP-1–3 was detected in any IgA fractions (data not shown). Levels of Trappin2/Elafin, HBD-2 and SLPI were similar between HESN men and unexposed controls.

Figure 1. Levels of soluble innate immune proteins in foreskin secretions.

HESN (hatched bars) and unexposed control men (open bars). Sub-preputial swabs collected before surgery were assayed for levels of soluble innate immune proteins by ELISA. Median concentration (with range) of innate peptide in 1mL collection volume is displayed (HESN n=18; Controls n=37).

Additionally, levels of cytokines and chemokines were assaying in a separate aliquot of undiluted sub-preputial swab samples (Table 2). IL-8 was present at a level that could be quantified in the majority of men; however, the median IL-8 levels did not differ significantly between HESN and control men (33.7 vs. 29.8pg/ml in HESN vs. control men, p=0.40). MCP-1, MIG, and RANTES were present in <50% of HESN men, and therefore the frequency of detection of these cytokines, as opposed to the concentration of analyte, was compared between groups. There were no HESN-associated differences in the frequency of detection of MCP-1, (42.1 vs. 50.9% of HESN vs. control men, p=0.6), MIG (47.4 vs. 54.5%, p=0.6), or RANTES (21.1 vs. 10.5%, p=0.3). IL-1α, MDC and MIP-3α were not detected in sub-preputial swabs. No HSV-2 associated differences in levels of cytokines, chemokines, and soluble innate factors were observed.

Table 2.

Chemokine and cytokine levels in sub-preputial swabs.

| LLOQ (pg/ml) |

HESN (n=19) | Unexposed controls (n=57) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of detection (%) |

Median (pg/ml) |

Frequency of detection (%) |

Median (pg/ml) |

sig.* | ||

| IL-1α | 10.3 | 0 (0.0%) | - | 0 (0.0%) | - | - |

| IL-8 | 1.5 | 18 (94.7%) | 33.73 | 52 (91.2%) | 29.84 | 0.40 |

| MCP-1 | 0.6 | 8 (42.1%) | - | 29 (50.9%) | 0.69 | 0.60 |

| MDC | 1250.0 | 0 (0.0%) | - | 0 (0.0%) | - | - |

| MIG | 0.3 | 9 (47.4%) | - | 31 (54.4%) | 0.34 | 0.61 |

| MIP-3α | 46.2 | 0 (0.0%) | - | 0 (0.0%) | - | - |

| RANTES | 3.0 | 4 (21.1%) | - | 6 (10.5%) | - | 0.26 |

IL-8 medians compared between groups using Mann-Whitney U, else frequency of detection was compared using Fisher’s exact test.

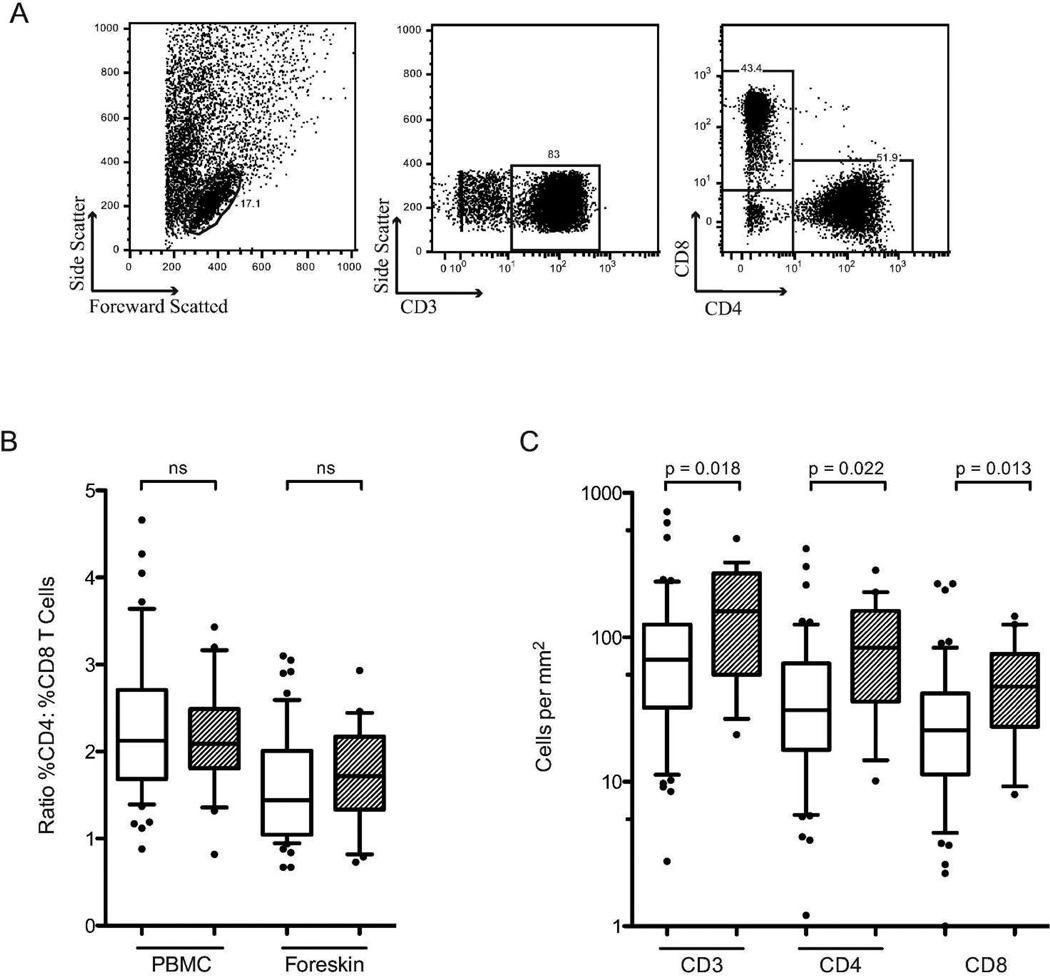

T cell subset density and relative proportions in the foreskin

The proportions of T cell subsets in the blood and foreskin were assessed by flow cytometry, and the average tissue density of foreskin T cell subsets was calculated by combining these proportions with immunohistochemical determination of CD3 T cell density/mm2 of tissue. The proportion of T cells expressing CD4 or CD8 did not differ between HESN men and unexposed controls (54.1 vs. 51.3% and 32.7 vs. 34.8% of T cells, respectively; ns). However, HESN men had a significantly higher density of CD3 T cells/mm2 of tissue after controlling for HSV-2 serostatus (151.9 vs. 69.9 cells/mm2, adjusted p=0.018, Figure 3C), and therefore had higher absolute numbers of both CD4 and CD8 T cells/mm2 of foreskin tissue (84.6 vs. 31.3 cells/mm2, p=0.022; 45.6 vs. 22.7 cells/mm2, p=0.013; Figure 3C). Density of foreskin T cells did not correlate with partner viral load.

Figure 3. T cell subsets in the blood and foreskin.

HESN (hatched bars) and unexposed control men (open bars). The proportion of CD3+ T cells expressing either CD4 or CD8 was measured on PBMCs and foreskin cells using flow cytometry (B); representative flow cytometry plots showing the gating strategy for foreskin cells are shown in A. Proportions of T cells subsets were normalized to the number of CD3 T cells per mm2 of foreskin tissue (obtained using IHC) to obtain absolute numbers of each cell type (C) (HESN n=20, Controls n=57).

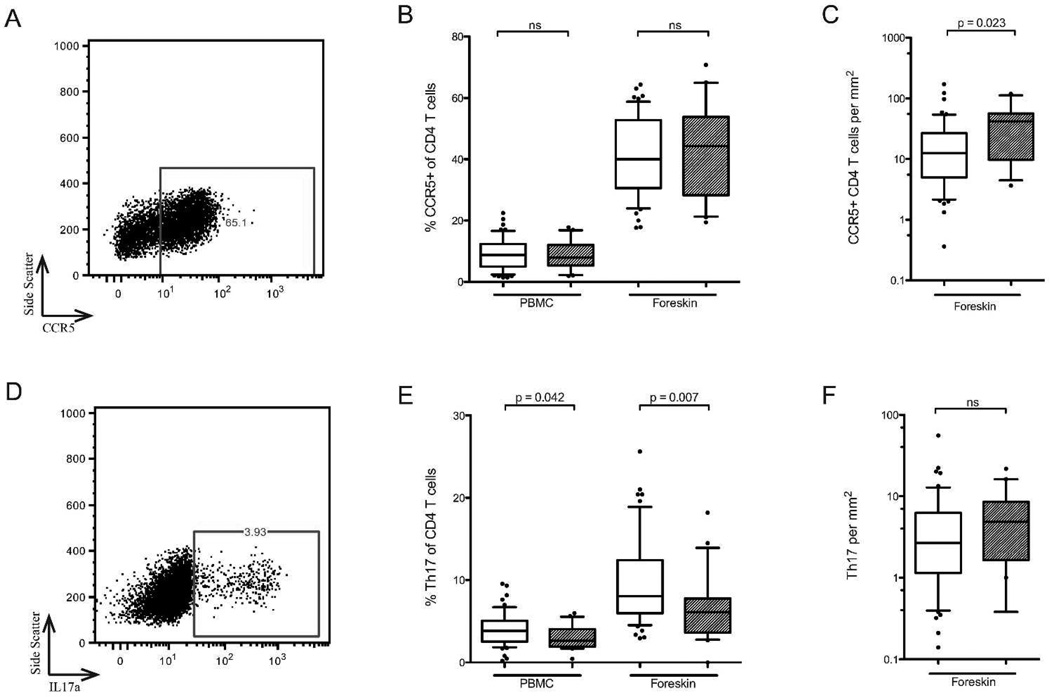

Phenotype and function of foreskin T cell subsets

Flow cytometry was used to further characterize the proportion of CD4 T cells classified as Th17 cells (production of IL-17a upon stimulation), T-regulatory cells (Tregs; co-expression of CD25 and FoxP3), and expressing the HIV co-receptor CCR5 (representative plots of foreskin staining shown in Figure 4A and D). Compared to unexposed controls, HESN men had a decreased proportion of Th17 cells in both the blood and the foreskin (2.6 vs. 3.8% of blood CD4 T cells, p=0.042; 6.1 vs. 8.0% of foreskin CD4 T cells, p=0.007; Figure 4E, but a similar proportion of Tregs (4.1 vs. 3.7% of blood CD4 T cells, ns; 2.9 vs. 3.7% of foreskin CD4 T cells, ns) and of CCR5+ CD4 T cells (7.8 vs. 8.7% of blood CD4 T cells, ns; 44.3 vs. 40.0% of foreskin CD4 T cells, ns; Figure 4B). This decreased relative abundance of Th17 cells did not correlate with partner viral load. Given the higher overall tissue density of T cells in the HESN foreskin, this translated into a similar absolute number of Th17 cells/mm2 in HESN men (4.9 vs. 2.7 cells/mm2, ns; Figure 4F, and an increased absolute number of CCR5+ CD4 T cells/mm2 (41.5 vs. 12.5, p=0.023; Figure 4C).

Figure 4. CD4 T cell subsets in the blood and foreskin.

HESN (hatched bars) and unexposed control men (open bars). CCR5 expression was measured on PBMCs and foreskin CD4 T cells using flow cytometry (representative foreskin plot in A). Th17 cells were identified by production of IL17a by CD4 T cells in response to stimulation with PMA and ionomycin (representative foreskin plot in D). Summary data of the proportion of CCR5+ CD4 T cells and Th17 cells in the blood and foreskin are shown in B and E. Absolute numbers of cells, obtained by IHC of CD3, are shown in C and F (HESN n=20, Controls n=57).

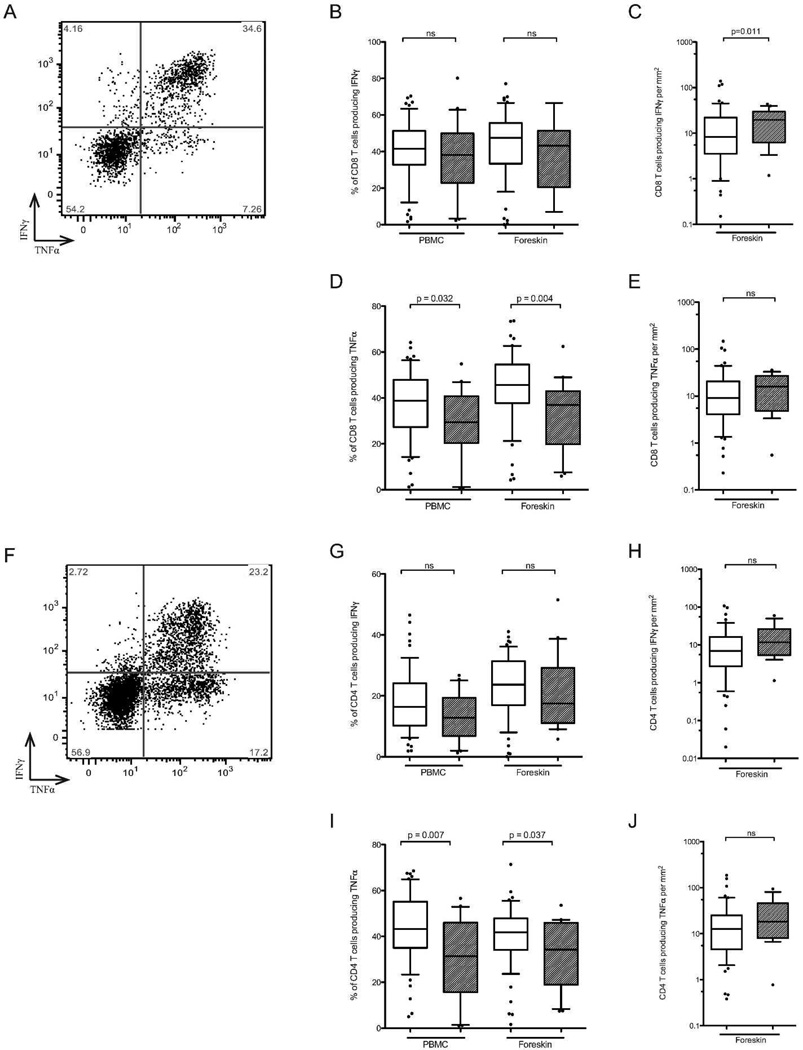

Production of the cytokines IFNγ and TNFα by foreskin and blood T cells after PMA-ionomycin stimulation was assessed by intracellular cytokine production (representative plots of foreskin staining shown in Figure 5A and F), with CD8− T cells used as a proxy for CD4 T cells. A decreased proportion of HESN CD8 and CD4 T cells produced TNFα in both the blood (CD8 T cells, 29.4% vs. 38.8%, p=0.032; CD4 T cells, 31.4% vs. 43.2%, p=0.007) and foreskin (CD8 T cells, 36.9% vs. 45.7%, p=0.004; CD4 T cells, 34.3% vs. 41.8%, p=0.037; Figures 5D and I). This decrease did not correlate with partner viral load. The absolute number of TNFα-producing CD8 or CD4 T cells was not statistically different in HESN and unexposed control foreskin tissue (15.9 vs. 9.1 CD8 T cells/mm2, Figure 5E, ns; 18.3 vs. 12.7, Figure 5J, ns). The proportion of CD8 and CD4 T cells producing IFNγ was similar between groups (38.1 vs. 41.5% PBMC CD8, ns; 43.2vs. 47.6% foreskin CD8, ns, Figure 5B; 12.8 vs. 16.5% PBMC CD4, ns; 17.5 vs. 23.7% foreskin CD4, ns, Figure 5G, ns), and so the increased overall T cell density in the HESN foreskin translated into a higher absolute number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells (19.7 vs. 8.3 cells/mm2, p=0.011; Figure 5C), but not CD4 T cells (11.7 vs. 6.94cells/mm2, ns; Figure 5H).

Figure 5. Inflammatory cytokine production by CD8 (A–E) and CD4 (F–J) T cells.

HESN (hatched bars) and unexposed control men (open bars). T cells isolated from foreskin tissue were challenged with PMA and ionomycin and subsequent TNFα and IFNγ production by either CD8+ T cells or CD8- T cells (a proxy for CD4 T cells) was measured by flow cytometry (representative plots shown for CD8 (A) and CD4 T cells (F). Summary data of the proportion of CD8 T cells producing TNFα or IFNγ shown in B and D, respectively. Absolute numbers of each cell type, obtained through CD3 IHC, are shown in C and E. Similarly, proportions of CD4 T cells producing TNFα or IFNγ shown in G and I, and absolute numbers of each cell type are shown in H and J (HESN n=20, Controls n=57).

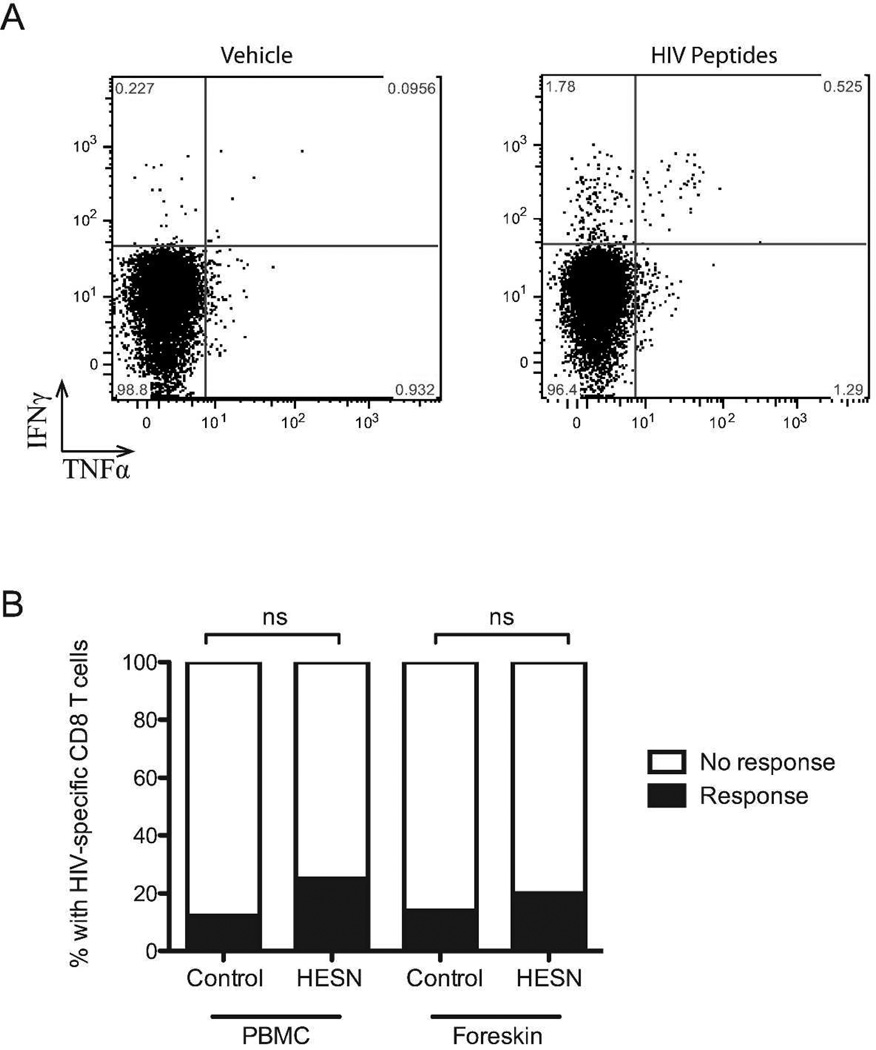

HIV-specific T cell responses in the foreskin

Blood and foreskin cell suspensions were stimulated with a pool of pre-defined, optimized CD8 T cell peptide epitopes (see Methods, above). To be considered a positive HIV-specific response: (1) ≥0.3% of CD8 T cells had to produce either TNFα or IFNγ in response to peptide stimulation (background subtracted), and (2) cytokine production in response to peptides had to exceed background cytokine production by at least threefold. HIV-specific CD8 T cell responses were observed in both the blood and the foreskin of a minority of participants (representative plot, Figure 6A), but there was no significant difference in the frequency of an HIV-specific response between HESN men and unexposed controls (blood, 3/20 (25.0%) vs. 7/57 (12.3%); foreskin, 2/20 (20.0%) vs. 8/57 (14.0%); both p>0.2, Figure 6B). Among participants with an HIV-specific response, the magnitude of that response was also similar in HESN men and controls for both the blood (mean % CD8 T cells producing TNFα amongst responding HESN men = 1.51% vs. 1.47% in unexposed controls, ns; mean % producing IFNγ = 0.71% vs. 0.37%, ns) and the foreskin, where only IFNγ responses were observed (0.37% vs. 1.02%, ns). The presence of HIV-specific responses in HESN men did not correlate with partner viral load or length of time of exposure to HIV, and did not correlate with other immune parameters found to be associated with HESN status (data not shown).

Figure 6. HIV-specific CD8 T cells responses in the foreskin.

CD8 T cells isolated from foreskin tissue were challenged with a pool of cross-clade HIV peptides previously shown to be highly antigenic in an East African population. (A) TNFα and IFNγ production by CD8 T cells was measured by flow cytometry. (B) Frequency of response for HESN and unexposed control men. An HIV-specific response was defined as cytokine production 3 times greater than observed in unstimulated cells and a minimum of 0.3% (HESN n=20, Controls n=57).

DISCUSSION

Natural susceptibility to HIV is heterogeneous, and elucidation of the mucosal immune correlates of reduced HIV susceptibility at sites of sexual exposure may provide important lessons for the HIV vaccine and microbicide fields. We combined epidemiological data collected through the Rakai Community Cohort Study with blinded immune studies of sub-preputial swabs and foreskin tissues to explore the immune correlates of HIV exposure without infection in the foreskin. We found secretions from the HESN foreskin to be enriched for α-defensins and HIV-neutralizing IgA. HESN foreskin tissue had an increased overall density of CD3+ T cells, but these T cells contained disproportionately fewer Th17 cells and produced less of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα. We did not find that HIV-specific T cell responses were associated with the HESN phenotype.

Our observation that HESN men were more likely to have IgA with the capacity to neutralize HIV is consistent with numerous previous reports, including studies in diverse HESN populations examining several mucosal sites12–14,31–35. While the presence of IgA with the ability to neutralize HIV in HESN populations is well established, the specificity of this IgA remains unknown36. Detection of HIV-specific IgA by a binding assay such as an ELISA or Western blot is rare37,38, and it is of note that the presence of HIV-neutralizing IgA did not correlate with foreskin HIV-specific CD8 T cells in this study. It may be that the target of this IgA is not HIV itself, but a host factor involved in HIV binding, such as CCR5, a lectin receptor39, or the integrin α4β740. Determining the target, mechanism of action, and source of this frequently observed neutralizing IgA should be a research priority.

While the sub-preputial space contained significant levels of several innate immune factors and cytokines, only the α-defensins HNP-1–3 were enriched in HESN sub-preputial swabs. Our group previously found that both HNP-1–3 and IgA in female genital secretions of Kenyan sex workers were correlated with in vitro HIV neutralization3. However, while HIV-neutralizing IgA was prospectively associated with HIV protection, increased α-defensins were associated with the presence of other genital co-infections as well as with an unexpected increase in the risk of HIV acquisition3. The latter finding may reflect the T cell chemoattractant properties of some antiviral innate factors and cytokines, as demonstrated by the association of vaginal RANTES levels with increased mucosal CD4+ target cells in vivo11, and emphasizes that ex vivo antiviral activity does not always predict in vivo protection against HIV.

We found that HESN men had an increased density of CD3+ T cells/mm2 in their foreskin tissue, independently of their HSV-2 serostatus. While this was unexpected, increased numbers of cervical T cells have been observed previously in HESN female CSWs11. Despite having an increased overall number of CD3+ T cells/mm2 of foreskin tissue, a smaller proportion of these T cells were Th17 cells or had the capacity to produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα. Studies in an SIV-rhesus macaque model have shown that initial infection in the FGT begins with a small founder population of infected T cells which grows through the recruitment of new, activated target cells driven by local inflammation41. Levels of susceptible target cells and local inflammation may therefore be a determinant in individual susceptibility to HIV. Th17 cells have been shown to be highly HIV-susceptible in vitro42,43 and to be selectively depleted during early HIV infection42, while TNFα increases HIV replication in a paracrine fashion and is produced by activated T cells that are more permissive to HIV infection44 and replication45. TNFα has also been shown to recruit CD4 T cells to foreskin tissue ex vivo46, and to activate dendritic cells, which may pass HIV to susceptible CD4 T cells through viral synapses39,47. Therefore, decreased production of TNFα and decreased proportion of Th17 cells in the HESN foreskin may inhibit the establishment of a founder population of infected cells after HIV exposure.

A decreased relative abundance of highly susceptible cell populations in conjunction with an increased overall number of T cells implies that there is an increased abundance of other T cell subsets. Further elucidation of these T cell populations in the HESN foreskin using multiparameter flow cytometry, as opposed to the 4-colour flow system available at our field site, should be a priority in future studies. This would also allow for characterization of other cell types that have been newly identified as important in HIV susceptibility, such as Th22 cells48 or cells expressing the gp120-binding integrin α4β740. Furthermore, the position of susceptible target cells within the foreskin may also be very relevant to HIV susceptibility, particularly their depth below the epithelial surface and/or proximity to other immune cell subsets. Ideally, future studies should identify exclusive surface markers for relevant T cell subsets, which would permit immunohistochemical analysis of these parameters.

It is important to note that the sexual behaviour of HESN individuals is, by definition, different to that of low risk men. Therefore cross-sectional studies of HESN genital immunology cannot distinguish which unique immune characteristics (if any) are protective against HIV, and which are related to increased sexual risk and may actually enhance susceptibility. Furthermore, while prospective studies of HIV acquisition would seem to be a way to address this issue, a drawback of using tissues obtained during male circumcision is that prospective studies of HIV acquisition in the foreskin then become impossible (as the foreskin is absent in future sexual exposures). Therefore animal models and/or improved ex vivo explant models of foreskin HIV infection may be useful ways to further characterize the direction of causation of the HESN immune associations that we have described.

In summary, we have combined epidemiology and mucosal immunology to define the unique immunological features of foreskins from men from Rakai, Uganda who are regularly exposed to HIV but have remained uninfected. We find that the foreskin of HESN men is characterized by increased overall T cell density in the context of reduced Th17 frequencies and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and by the presence of HIV-neutralizing IgA and elevated α-defensin levels in foreskin secretions. The ability of these immune parameters, either separately or in combination, to protect against HIV acquisition in the foreskin merits investigation in future research studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

Participants consisted of 77 heterosexual couples enrolled in a broader study of foreskin immunology27,30. Participants were recruited from an established community cohort in Rakai, Uganda28, in which the HIV-seronegative male partner had elected to undergo adult male circumcision for HIV prevention. HESN men were HIV-seronegative and in a stable relationship with an ART-naïve, HIV-seropositive female who had a detectable HIV plasma viral load, and reported inconsistent or no condom use with this female partner despite risk-reduction counseling and the provision of free condoms. Unexposed control men were HIV-seronegative and in a monogamous relationship with an HIV-seronegative woman. All participants provided written informed consent, and formal ethical approval was obtained at the University of Toronto, the Uganda Virus Research Institute’s Scientific and Ethical Committee, Karolinska Institutet and Western IRB (Olympia, WA).

Sample collection and diagnostic testing

Each partner within the couple completed a behavioral questionnaire before sample collection/surgery. Women provided 8ml of venous blood. Men underwent a physical examination prior to surgery, and circumcision was deferred until after treatment if urethral discharge or clinically apparent genital ulceration was present; 16ml of whole blood and a swab from the sub-preputial space were then collected prior to surgery. A single sub-preputial swab was collected from each participant immediately prior to surgery using a FLOQswab (COPAN Diagnostics, Murrieta, CA USA) pre-moistened in sterile PBS and rolled once around the coronal sulcus and once down the frenulum. Swabs were collected by the same medical officers throughout the study, and care was taken to collect each swab in a consistent manner. Swabs were then resuspended in 1mL of AMPLICOR® STD Specimen Transport Kit medium (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA) and stored at 4°C until division into two aliquots (one for cytokine detection and one for IgA/innate factor analysis), which were stored at −80°C. Foreskin tissue was processed immediately upon surgical excision in a room adjoining the surgical suite, with two sections snap-frozen into cryomolds in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound (Fisher Scientific, Toronto, Canada) for immunohistochemistry (IHC), and one large section collected for T cell isolation. All foreskin tissues were labeled with a unique identifier and provided to research personnel blinded to participant study group for subsequent processing and immune analysis.

The HIV infection status of both partners was confirmed using two HIV ELISAs (Murex HIV-1.2.O, Abbott, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA; and Vironistika HIV Uni-Form II plus O Mircoelisa System, bioMerieux; Marcy l'Etoile, France). Discordant results were confirmed by Western blot (GS HIV-1 Western Blot, BioRad; Hercules, CA, USA). All participants were also screened for acute HIV infection using real time PCR. RNA was extracted from plasma samples using the Abbott Sample Preparation System, and amplification was performed using the Real Time HIV-1 Amplification Reagent Kit (Abbott) and run on the M2000rt (Abbott) with a lower limit of detection of 40 cps/mL. CD4 counts were performed using Tritest Reagent in combination with Trucount Tubes and were analyzed on a FACSCalibur platform (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). HSV-2 infection status was determined by ELISA (Herpes Simplex Type 2 IgG ELISA, Kalon Biological Ltd., Guildford, UK), as previously validated in Rakai49.

T cell isolation from the foreskin and blood

T cell isolation from foreskin tissues and blood was initiated within 15 minutes of surgery, as previously described27. Briefly, tissue was disrupted by a combination of mechanical and enzymatic digestion with 1.0mL of 500U/mL Collagenase Type I (Gibco, Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 42.5U/mL of DNAse (Invitrogen). The resulting cell suspension was filtered through a 100µm cell strainer (BD Biosciences; Franklin Lakes, NJ USA) to remove any remaining undigested tissue. Filtered cells were allowed to rest under normal growth conditions (37°C, 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere) for 3–7 hours. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque Plus; Amersham Biosciences; Uppsala, Sweden).

Characterization of T cell subsets

Both PBMC and foreskin cell counts were determined by trypan blue exclusion. 1×106 PBMCs and 10–20×106 foreskin cells (depending on yield) were plated in 500µl culture medium and stimulated for 9 hours at 37°C in the presence of 5µg/ml Brefeldin A (GolgiPlug, BD Biosciences), with either: 1ng/ml phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) and 1µg/ml ionomycin (both from Sigma; St. Lousi, MO, USA); or 102µg/ml of a pool of 51 HIV peptide epitopes (9–11 amino acids long, JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany) previously found by our group to be highly antigenic in an East African population50; or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). After stimulation, samples were washed with cold 2% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) in PBS and stained with fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies specific for CD3 (UCHT1), CD4 (RPA-T4), CD8 (SK1), CCR5 (2D7/CCR5), and CD25 (M-A251; all BD Biosciences). Samples for intracellular staining were permeabilized using either the eBioscience fixation/permeabilization solution for Treg identification (eBiosciences; San Diego, CA, USA) or the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) for other assays. Cells were then stained with fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies specific for combinations of the following intracellular cytokines/transcription factors: TNFα (MAb11; BD Biosciences), IFNγ (B27; BD Biosciences), IL17a (eBio64DEC17; eBioscience), IL22 (22URTI; eBioscience), and FoxP3 (PCH101; eBioscience). Samples were acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Systems). Gating was performed as previously described27.

Measuring CD3 density by immunohistochemistry

In order to translate flow-derived cell proportions into an absolute tissue density of foreskin T cells, two sections of foreskin where collected from each participant and immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed. OCT cryopreserved tissues were sectioned to 8µm, fixed in 2% formaldehyde, and frozen for batch staining. For CD3 staining, frozen sections were thawed and air-dried at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase and biotin activities were blocked using 0.3% hydrogen peroxide and avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Labs), respectively, followed by 10% normal goat serum. Sections were then incubated with rabbit anti-human CD3 antibody (DAKO, Vector Labs), followed by biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary and Alkaline Phosphatase Streptavidin Labeling Reagent (all Vector Labs). Colour development was performed with freshly prepared Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate Kit Vector Red (Vector Labs). Finally, sections were counterstained lightly with Mayer’s Hematoxylin, dehydrated in alcohols, cleared in xylene, and mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific). The number of CD3+ T cells per mm2 of tissue for each patient was derived from the average of two tissue sections taken from distal locations on the foreskin. A median of 6.10mm2 of foreskin tissue was analyzed by IHC per patient. Whole sections were scanned at 0.5µm/pixel using the TissueScope 4000 (Huron Technologies, Waterloo, Canada). Image analysis software (Definiens, München, Germany) was used to delineate the apical edge of the epidermis and create fields of view (FOV) of the entire length of each section to a depth of 300µm (excluding artifacts or folds, see supplementary data). CD3 cells in each FOV were manually counted by an investigator blinded to group status. A CD3 positive cell was defined as nuclear hematoxylin staining overlapping with, or directly adjacent to, Vector Red staining.

IgA purification and PBMC neutralization assays

Neutralizing IgA activity was assessed in a subset of samples (18 HESN men and 37 unexposed controls) where samples were available. One aliquot of sub-preputial swab (500µL) was thawed and centrifuged at 1500 rpm (5 min, 4°C) to remove cellular debris. IgA was purified as previously described33. Briefly, 400µL undiluted swab solution was added to 200µL jacalin/agarose beads (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA), mixed for 2 hours at 4°C, and centrifuged to separate the IgA-depleted fraction (stored at −80°C for innate factor analysis). Jacalin/agarose beads were thoroughly washed with PBS pH 7.4, and bound IgA was eluted overnight at room temperature by adding 500µL 0.8 M D-galactose pH 7.5. The supernatant (purified IgA) was collected, diluted 1:2 with RMPI 1640 medium (Invitrogen AB, Lidingö, Sweden) and stored at −80°C. HIV neutralization assays were performed according to a predefined protocol and neutralization cut-off14. R5 tropic primary isolates (clade C: ZA009, obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH) were collected from PBMC stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA-P) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) (both Sigma-Aldrich Sweden AB, Stockholm, Sweden). The TCID50 was determined and supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Since the TCID50 may differ between PBMC donors, three viral dilutions were used in each assay. IgA fractions were diluted 1:2 with RMPI 1640 medium (Invitrogen AB, Lidingö, Sweden) and 75µL of this diluted sample was incubated with 75µL of each virus dilution (in duplicate) for 1 hour at 37°C to allow for viral neutralization. Virus was mixed with 1×105 PHA-P-stimulated mixed PBMCs from 2–3 donors; after 24h incubation at 37°C, PBMCs were washed and cultured for 6 days in 200µL of fresh RMPI 1640 medium supplemented with bovine serum albumin and IL-2, with half the medium replaced on day 3. Supernatants were collected on day 6 for analysis of virus production with a p24 antigen ELISA (Vironostika HIV-1 Antigen; Electra-Box Diagnostica AB, Stockhom, Sweden). Percent neutralization was defined as the reduction in p24 production compared to a reference sample (created by pooling IgA from 5 unexposed control men). However, there is significant inter-assay variability in the quantity of p24 antigen produced as a result of PBMC donor variability. We therefore treated IgA neutralization as a binary outcome, where successful neutralization was defined as a ≥67% percent neutralization. A cut-off of ≥67% provides robust reproducibility of successful neutralization13, has been shown to correlate prospectively with protection from infection14. Positive control samples (HIV IgG positive serum) were included in each assay. Samples that did not have consistent absence/presence of neutralization in all three viral dilutions were re-tested until a consensus was achieved.

Innate factor analysis

Trappin/Elafin, Human Neutrophil Peptides 1–3 (HNP-1–3), human β-defensin 2 (HBD-2) and Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) were quantified in IgA depleted fractions of sub-preputial swabs. Commercial ELISA kits were used according to the manufacturers protocols as follows (additional dilutions in parentheses): Trappin/Elafin (1:10), α-defensins HNP-1–3 (1:10) (all from HyCult Biotechnology, Uden, The Netherlands), β-defensins HBD-2 (1:10–1:100) (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, CA, USA) and SLPI (1:5–1:100) (RD Systems Europe, Abingdon Oxon, UK).

Cytokine and Chemokine analysis of sub-preputial swabs

The second 500µL aliquot of sub-preputial swab was assayed for cytokine levels using an electrochemiluminescent detection system. A custom Human Ultra-Sensitive 7-spot kit from Meso Scale Discovery (Rockville, MD, USA) was utilized to assay the following cytokines and chemokines in the undiluted sub-preputial swabs: IL-1α (interleukin-1α), IL-8, MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1), MDC (macrophage-derived chemokine), MIG (monokine induced by γ-interferron), MIP-3α (Macrophage inflammatory protein-3α) and RANTES (Regulated on Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted). Plates were imaged using the Sector Imager 2400A platform (Meso Scale Discovery). The manufacturer suggests determining the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for each analyte on a per-plate basis. However, due to the large number of samples analyzed in this study multiples were required and as a result of inter-run variability slightly different LLOQ values were obtained. For the purposes of this study, we set an overall study LLOQ at 75th quartile of all plate LLOQs. Sample measurements below the study LLOQ were imputed as the value of the LLOQ: IL-1α= 10.3pg/ml; IL-8= 1.5pg/ml; MCP-1= 0.6pg/ml; MDC= 1250.0pg/ml; MIG= 0.3pg/ml; MIP-3α= 46.2pg/ml; RANTES= 3.0pg/ml. However, due to the low chemokine concentrations in sub-preputial swabs, only levels of IL-8 were quantifiable in >50% of men in both groups, and as a result cytokines other than IL-8 were treated as a binary outcome of either “detectable” or “undetectable”.

Statistical analysis

All immune assays were performed by research personnel blinded to participant study group; immune data files were cleaned and finalized prior to study group linkage. Innate factors, chemokines, cytokines, and T cell populations were compared between HESN and unexposed controls by Mann-Whitney U test. Associations between demographic factors and immunological parameters were tested by Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Demographic variables found to be associated with HESN status (HSV-2 status and concurrent sexual partners) were controlled for by multivariate general linear regression and adjusted p-values are reported. Proportions of men with HIV-specific IgA and CD8 T cell responses were compared by Fisher’s exact test. Statistical tests were run using SPSS v.19.0 for Mac (IBM; New York, NY, USA). Flow cytometry data was analyzed in FlowJo v.9.5.2 (Treestar; Ashland, OR, USA) and Excel (Microsoft; Redmond, WA, USA) prior to statistical testing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge STTARR at the Toronto MaRS Discovery District for assistance with CD3 image analysis and Mariethe Ehnlund at the Karolinska Institute for technical assistance.

Funding was provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, grant number 22006.03, and R01AI087409-01A1, UO1AI51171, and 1UO1AI075115-O1A1 from the National Institutes of Health. The study was supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Rakai Genital Immunology Group Members:

Kighoma Nehemiah

Tumuramye Denis

Mbagiira Emma

Kubaawo John-Bosco

Isabirye Yahaya

Mulema Patrick

Teba James

Atukunda Boru

Mayengo Herbert

Nakafeero Mary

Mugamba Stephen

Nakyeyune Mary

Anyokorit Margaret

Male Deo

Kayiwa Dan

Kalibbala Sarah

Lubyayi Lawrence

Otobi Ouma Joseph

Kakanga Moses

Okech John Baptist

Okello Grace

Aluma Gerald

Ssebugenyi Ivan

Balikudembe Ambrose

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Hladik F, McElrath MJ. Setting the stage: host invasion by HIV. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:447–457. doi: 10.1038/nri2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levinson P, et al. HIV-neutralizing activity of cationic polypeptides in cervicovaginal secretions of women in HIV-serodiscordant relationships. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinson P, et al. Levels of innate immune factors in genital fluids: association of alpha defensins and LL-37 with genital infections and increased HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2009;23:309–317. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321809c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinones-Mateu ME, et al. Human epithelial beta-defensins 2 and 3 inhibit HIV-1 replication. Aids. 2003;17:F39–F48. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zapata W, et al. Increased levels of human beta-defensins mRNA in sexually HIV-1 exposed but uninfected individuals. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:531–538. doi: 10.2174/157016208786501463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lajoie J, et al. A distinct cytokine and chemokine profile at the genital mucosa is associated with HIV-1 protection among HIV-exposed seronegative commercial sex workers. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:277–287. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgener A, et al. Salivary basic proline-rich proteins are elevated in HIV-exposed seronegative men who have sex with men. Aids. 2012;26:1857–1867. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357f79c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iqbal SM, et al. Elevated elafin/trappin-2 in the female genital tract is associated with protection against HIV acquisition. Aids. 2009;23:1669–1677. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832ea643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirbod T, et al. Upregulation of interferon-alpha and RANTES in the cervix of HIV-1-seronegative women with high-risk behavior. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:137–143. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000229016.85192.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirbod T, et al. HIV-1 neutralizing activity is correlated with increased levels of chemokines in saliva of HIV-1-exposed uninfected individuals. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:28–33. doi: 10.2174/157016208783571964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iqbal SM, et al. Elevated T cell counts and RANTES expression in the genital mucosa of HIV-1-resistant Kenyan commercial sex workers. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:728–738. doi: 10.1086/432482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasselrot K, et al. Oral HIV-exposure elicits mucosal HIV-neutralizing antibodies in uninfected men who have sex with men. Aids. 2009;23:329–333. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831f924c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi RY, et al. Cervicovaginal HIV-1 Neutralizing IgA Detected among HIV-1-Exposed Seronegative Female Partners in HIV-1-Discordant Kenyan Couples. Aids. 2012 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359b99b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirbod T, et al. HIV-neutralizing immunoglobulin A and HIV-specific proliferation are independently associated with reduced HIV acquisition in Kenyan sex workers. Aids. 2008;22:727–735. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f56b64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaul R, et al. Genital levels of soluble immune factors with anti-HIV activity may correlate with increased HIV susceptibility. Aids. 2008;22:2049–2051. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328311ac65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Z, et al. HIV-1 efficient entry in inner foreskin is mediated by elevated CCL5/RANTES that recruits T cells and fuels conjugate formation with Langerhans cells. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002100. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Card Catherine M, et al. Decreased Immune Activation in Resistance to HIV −1 Infection Is Associated with an Elevated Frequency of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+Regulatory T Cells. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;199:1318–1322. doi: 10.1086/597801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legrand FA, et al. Strong HIV-1-specific T cell responses in HIV-1-exposed uninfected infants and neonates revealed after regulatory T cell removal. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bégaud E, et al. Reduced CD4 T cell activation and in vitro susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in exposed uninfected Central Africans. Retrovirology. 2006;3:35. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koning FA, et al. Low-Level CD4+ T Cell Activation Is Associated with Low Susceptibility to HIV-1 Infection. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:6117–6122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camara M, et al. Low-level CD4+ T cell activation in HIV-exposed seronegative subjects: influence of gender and condom use. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:835–842. doi: 10.1086/651000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chege D, et al. Blunted IL17/IL22 and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Responses in the Genital Tract and Blood of HIV-Exposed, Seronegative Female Sex Workers in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaren PJ, et al. HIV-exposed seronegative commercial sex workers show a quiescent phenotype in the CD4+ T cell compartment and reduced expression of HIV-dependent host factors. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(Suppl 3):S339–S344. doi: 10.1086/655968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auvert B, et al. Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey R, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2007;369:643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RH, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. The Lancet. 2007;369:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prodger JL, et al. Foreskin T-cell subsets differ substantially from blood with respect to HIV co-receptor expression, inflammatory profile, and memory status. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:121–128. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray RH, et al. Male circumcision and HIV acquisition and transmission: cohort studies in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2000;14:2371–2381. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson KE, et al. Effects of HIV-1 and Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection on Lymphocyte and Dendritic Cell Density in Adult Foreskins from Rakai, Uganda. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;203:602–609. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prodger JL, et al. Impact of asymptomatic Herpes simplex virus-2 infection on T cell phenotype and function in the foreskin. Aids. 2012;26:1319–1322. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328354675c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beyrer C, et al. Epidemiologic and biologic characterization of a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 highly exposed, persistently seronegative female sex workers in northern Thailand. Chiang Mai HEPS Working Group. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:59–67. doi: 10.1086/314556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broliden K, et al. Functional HIV-1 specific IgA antibodies in HIV-1 exposed, persistently IgG seronegative female sex workers. Immunol Lett. 2001;79:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devito C, et al. Mucosal and plasma IgA from HIV-exposed seronegative individuals neutralize a primary HIV-1 isolate. Aids. 2000;14:1917–1920. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaul R, et al. HIV-1-specific mucosal IgA in a cohort of HIV-1-resistant Kenyan sex workers. Aids. 1999;13:23–29. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo Caputo S, et al. Mucosal and systemic HIV-1-specific immunity in HIV-1-exposed but uninfected heterosexual men. Aids. 2003;17:531–539. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirbod T, Broliden K, Kaul R. Genital immunoglobulin A and HIV-1 protection: virus neutralization versus specificity. Aids. 2008;22:2401–2402. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328314e3a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiore JR, et al. Limited secretory-IgA response in cervicovaginal secretions from HIV-1 infected, but not high risk seronegative women: lack of correlation to genital viral shedding. New Microbiol. 2000;23:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horton RE, et al. Cervical HIV-specific IgA in a population of commercial sex workers correlates with repeated exposure but not resistance to HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:83–92. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soderlund J, et al. Plasma and mucosal fluid from HIV type 1-infected patients but not from HIV type 1-exposed uninfected subjects prevent HIV type 1-exposed DC from infecting other target cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:101–106. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cicala C, et al. The integrin α4β7 forms a complex with cell-surface CD4 and defines a T-cell subset that is highly susceptible to infection by HIV-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:20877–20882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911796106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Q, et al. Glycerol monolaurate prevents mucosal SIV transmission. Nature. 2009;458:1034–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature07831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gosselin A, et al. Peripheral blood CCR4+CCR6+ and CXCR3+CCR6+CD4+ T cells are highly permissive to HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 2010;184:1604–1616. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monteiro P, et al. Memory CCR6+CD4+ T cells are preferential targets for productive HIV type 1 infection regardless of their expression of integrin beta7. J Immunol. 2011;186:4618–4630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang ZQ. Roles of substrate availability and infection of resting and activated CD4+ T cells in transmission and acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:5640–5645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308425101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaspan HB, et al. Immune Activation in the Female Genital Tract During HIV Infection Predicts Mucosal CD4 Depletion and HIV Shedding. J Infect Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fahrbach KM, Barry SM, Anderson MR, Hope TJ. Enhanced cellular responses and environmental sampling within inner foreskin explants: implications for the foreskin's role in HIV transmission. Mucosal Immunology. 2010;3:410–418. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganor Y, et al. Within 1-h, HIV-1 uses viral synapses to enter efficiently the inner, but not outer, foreskin mucosa and engages Langerhans–T cell conjugates. Mucosal Immunology. 2010;3:506–522. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim CJ, et al. A role for mucosal IL-22 production and Th22 cells in HIV-associated mucosal immunopathogenesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gamiel JL, et al. Improved Performance of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays and the Effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Coinfection on the Serologic Detection of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 in Rakai, Uganda. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2008;15:888–890. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00453-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaul R, et al. New insights into HIV-1 specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in exposed, persistently seronegative Kenyan sex workers. Immunol Lett. 2001;79:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.