Abstract

Background

Fascioliasis is an important and neglected disease of humans and other mammals, caused by trematodes of the genus Fasciola. Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica are valid species that infect humans and animals, but the specific status of Fasciola sp. (‘intermediate form’) is unclear.

Methods

Single specimens inferred to represent Fasciola sp. (‘intermediate form’; Heilongjiang) and F. gigantica (Guangxi) from China were genetically identified and characterized using PCR-based sequencing of the first and second internal transcribed spacer regions of nuclear ribosomal DNA. The complete mitochondrial (mt) genomes of these representative specimens were then sequenced. The relationships of these specimens with selected members of the Trematoda were assessed by phylogenetic analysis of concatenated amino acid sequence datasets by Bayesian inference (BI).

Results

The complete mt genomes of representatives of Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica were 14,453 bp and 14,478 bp in size, respectively. Both mt genomes contain 12 protein-coding genes, 22 transfer RNA genes and two ribosomal RNA genes, but lack an atp8 gene. All protein-coding genes are transcribed in the same direction, and the gene order in both mt genomes is the same as that published for F. hepatica. Phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated amino acid sequence data for all 12 protein-coding genes showed that the specimen of Fasciola sp. was more closely related to F. gigantica than to F. hepatica.

Conclusions

The mt genomes characterized here provide a rich source of markers, which can be used in combination with nuclear markers and imaging techniques, for future comparative studies of the biology of Fasciola sp. from China and other countries.

Keywords: Liver fluke, Fasciola spp, Mitochondrial genome, Phylogenetic analysis

Background

Food-borne trematodiases are an important group of neglected parasitic diseases. More than 750 million people are at risk of such trematodiases globally [1,2]. Fascioliasis is caused by liver flukes of the genus Fasciola, and has a significant adverse impact on both human and animal health worldwide [3]. Human fascioliasis is caused by the ingestion of freshwater plants or water contaminated with metacercariae of Fasciola[4]. It is estimated that millions of people are infected worldwide, and more than 180 million people are at risk of this disease worldwide [5]. To date, no vaccine is available to prevent fascioliasis. Fortunately, this disease can be treated effectively using triclabendazole [6], but there are indications of resistance developing against this compound [7].

The Fasciolidae is a family of flatworms and includes the genus Fasciola. Both F. hepatica and F. gigantica, which commonly infect livestock animals and humans (as definitive hosts), are recognized as valid species [8]. The accurate identification of species and genetic variants is relevant in relation to studying their biology, epidemiology and ecology, and also has applied implications for the diagnosis of infections. Usually, morphological features, such as body shape and perimeter as well as length/width ratio, are used to identify adult worms of Fasciola[9]. However, such phenotypic criteria are unreliable for specific identification and differentiation, because of considerable variation and/or overlap in measurements between F. hepatica and F. gigantica[10].

Due to these constraints, various molecular methods have been used for the specific identification of Fasciola species and their differentiation [5]. For instance, PCR-based techniques using genetic markers in nuclear ribosomal (r) and mitochondrial (mt) DNAs have been widely used [11-13]. The sequences of the first and second internal transcribed spacers (ITS-1 and ITS-2 = ITS) of nuclear rDNA have been particularly useful for the specific identification of F. hepatica and F. gigantica, based on a consistent level of sequence difference (1.2% in ITS-1 and 1.7% in ITS-2) between them and much less variation within each species [11,14]. Nonetheless, studies in various countries, including China [5], Iran [15], Japan [16], Korea [14], Spain [17] and Tunisia [18], have shown that some adult specimens of Fasciola sp., which are morphologically similar to F. gigantica[10], are characterized by multiple sequence types (or “alleles”) of ITS-1 and/or ITS-2, reflected in a mix between those of F. hepatica and F. gigantica[11,12]. Some authors [19-21] have suggested that such specimens (sometimes called ‘intermediate forms’) represent hybrids of F. hepatica and F. gigantica.

In the present study, we undertook an independent, genetic comparison of Fasciola sp. (i.e. ‘intermediate form’) and F. gigantica with F. hepatica. To do this, we characterized the mt genomes of individual specimens of Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica whose identity was defined based on their ITS-1 and/or ITS-2 sequences, and assessed their relationships by comparison with F. hepatica and various other trematodes using complete, inferred mt amino acid sequence data sets.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Permit code. LVRIAEC2012-006). Adult specimens of Fasciola were collected from bovids, in accordance with the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of the People's Republic of China.

Parasites and isolation of total genomic DNA

Adult specimens of Fasciola sp. were collected from the liver of a dairy cow (Bos taurus) in Heilongjiang province, China. Adult specimens of F. gigantica were collected from the liver of a buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) in Guangxi province, China. The worms were washed extensively in physiological saline, fixed in ethanol and then stored at −20°C until use. Single specimens were identified as Fasciola sp. or F. gigantica based on PCR-based sequencing of the ITS-1 and ITS-2 rDNA regions [11,12].

Long-range PCR-based sequencing of mt DNA

To obtain some mt gene sequence data for primer design, regions (400–500 bp) of the cox1 and nad4 genes were PCR-amplified and sequenced using relatively conserved primers JB3/JB4.5 and ALF/ALR [13,22], respectively. Using BigDye terminator v.3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany), the amplicons were sequenced in both directions in a PRISM 3730 sequencer (ABI, USA). After sequencing regions of the cox1 and nad4 genes of both Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica, two internal pairs of conserved primers were designed (Table 1). These pairs were then used to long PCR-amplify the complete mt genome [23] in two overlapping fragments (cox1-nad4; ~9 kb and, nad4-cox1 = ~6 kb) from a proportion of total genomic DNA (10–20 ng) from one individual of Fasciola sp. and another of F. gigantica. The cycling conditions used were 92°C for 2 min (initial denaturation), then 92°C for 10 s (denaturation), 58–63°C for 30 s (annealing), and 60°C for 5 min (extension) for 5 cycles, followed by 92°C for 2 min, 92°C for 10 s, 58–63°C for 30 s, and 66°C for 5 min for 20 cycles, and a final extension at 66°C for 10 min. Each amplicon, which represented a single band in a 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel, following electrophoresis and ethidium-bromide staining [23], was column-purified and then sequenced using a primer-walking strategy [24].

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used to amplify mt DNA regions from Fasciola spp.

| Primer | Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|

|

F. gigantica |

|

| FGCF1 |

TGTTTACTATTGGTGGGGTTACTGGT |

| FGNR1 |

CAAACCCTACAGAACTATCCCTCCAA |

| FGNF1 |

GTTATGGGATTCAGTCTTGGAGGGAT |

| FGCR1 |

CGTATCCAAAAGAGAAGCAGAAAGCA |

|

Fasciola sp. |

|

| FZCF1 |

GGGTTACTGGTATTATGCTTTCTGCT |

| FZNR1 |

CCCTACAGAACTATCCCTCCAAGACT |

| FZNF1 |

GGTGGTATTATGGGCAGTTATGGGAT |

| FZCR1 | CAGAAAGCATAATACCAGTAACCCCA |

Sequence analyses

Sequences were manually assembled and aligned against each other, and then against the complete mt genome sequences of 11 other trematodes (see section on Phylogenetic analysis) using the program Clustal X 1.83 [25] and manual adjustment, in order to infer gene boundaries. Open-reading frames (ORFs) were established using the program ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html), employing the trematode mt code, and subsequently compared with those of F. hepatica[26]. Translation initiation and termination codons were identified based on comparisons with those of F. hepatica[26]. The secondary structures of 22 tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [27] with manual adjustment [28], and rRNA genes were predicted by comparison with those of F. hepatica[26].

Sliding window analysis of nucleotide variation

To detect variable nucleotide sites, pairwise alignments of the complete genomes, including tRNAs and all intergenic spacers, were performed using Clustal X 1.83. The complete mt genome sequences of Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica were aligned with that published previously for F. hepatica (NC_002546) [26], and sliding window analysis was conducted using DnaSP v.5 [29]. A sliding window of 300 bp (in 10 bp overlapping steps) was used to estimate nucleotide diversity Pi (π) across the alignment. Nucleotide diversity was plotted against mid-point positions of each window, and gene boundaries were identified.

Phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid sequences conceptually translated from individual genes of the mt genomes of each Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica were concatenated. For comparative purposes, amino acid sequences predicted from published mt genomes of selected members of the subclass Digenea, including F. hepatica (NC_002546) [26] [Fasciolidae]; Clonorchis sinensis (GeneBank accession no. FJ381664), Opisthorchis felineus (EU921260) [30] and O. viverrini (JF739555) [31] [family Opisthorchiidae]; Paragonimus westermani (NC_002354) [Paragonimidae]; Trichobilharzia regenti (NC_009680) [32], Orientobilharzia turkestanicum (HQ283100) [33], Schistosoma mansoni (NC_002545) [34], S. japonicum (HM120846) [35], S. mekongi (NC_002529) [34], S. spindale (DQ157223) [36] and S. haematobium (DQ157222) [35] [Schistosomatidae], were also included in the analysis. A sequence representing Gyrodactylus derjavinoides (accession no. NC_010976) was included as an outgroup [37]. All amino acid sequences were aligned using the program MUSCLE [38] and subjected to phylogenetic analysis using Bayesian inference (BI), as described previously [39,40]. Phylograms were displayed using the program Tree View v.1.65 [41]. In addition, all publicly available sequences of NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 gene (nad1) of Fasciola sp.. F. gigantica and F. hepatica were aligned (over a consensus length of 359 bp) using MUSCLE, the alignment was modified manually, and then subjected to phylogenetic analysis by BI, applying the General Time Reversible (GTR) model. Nodal support values for the final phylogram were determined from the final 75% of trees obtained using a sample frequency of 100. The analysis was performed until the potential scale reduction factor approached 1 and the average standard deviation of split frequencies was less than 0.01. An nad1 sequence of Fascioloides magna was used as an outgroup in phylogenetic analysis.

Results

Identity of the two liver flukes, and features of the mt genomes

The ITS-1 and ITS-2 sequences (GenBank accession no. KF543341) of the specimen of Fasciola sp. from Heilongjiang province were the same as that of an ‘intermediate form’ of Fasciola from China (AJ628428, AJ557570 and AJ557571) reported previously [11,12], which is characterized by polymorphic positions at 10 positions in ITS-1 and ITS-2 (Additional file 1: Figure S1; Table 2). Based on these key polymorphic positions (cf. [11,12]), this specimen of Fasciola sp. from China was inferred to be a hybrid between F. gigantica and F. hepatica. The ITS-1 and ITS-2 sequences of the F. gigantica sample (accession no. KF543340) from Guangxi province were consistent with that of the same species from Niger (AM900371) and did not have any polymorphic positions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of nucleotides at variable positions in ITS-1 and ITS-2 rDNA sequences of Fasciola from different geographical locations

| Species | Locations |

Variable positions in ITS-1 and ITS-2 sequences

*

|

Accession nos. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 108 | 202 | 280 | 300 | 791 | 815 | 854 | 860 | 911 | |||

|

F. hepatica |

China |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

JF708026 |

| |

France |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

JF708034 |

| |

Iran |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

JF432072 |

| |

Niger |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

AM850107 |

| |

Spain |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

JF708036 |

|

F. gigantica |

Burkina Faso |

T |

T |

T |

A |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

- |

AJ853848 |

| |

China |

T |

T |

T |

A |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

- |

JF496709 |

| |

Niger |

T |

T |

T |

A |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

- |

AM900371 |

| |

Present study |

T |

T |

T |

A |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

- |

KF543340 |

|

Fasciola sp. |

China |

C/T |

A/T |

C/T |

T/A |

C/T |

T/C |

T/C |

C/T |

C/T |

T/- |

AJ628428, AJ557570, AJ557571 |

| |

China, Japan |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

AB385611, AB010978 |

| Present study | C/T | A/T | C/T | T/A | C/T | T/C | T/C | C/T | C/T | T | KF543341 | |

*Sequence positions were determined by comparison with that of a previous study [11]. Sequences include ITS-1 (polymorphic positions 18, 108, 202, 280, 300), 5.8S rDNA and ITS-2 (polymorphic positions 791, 815, 854, 860, 911).

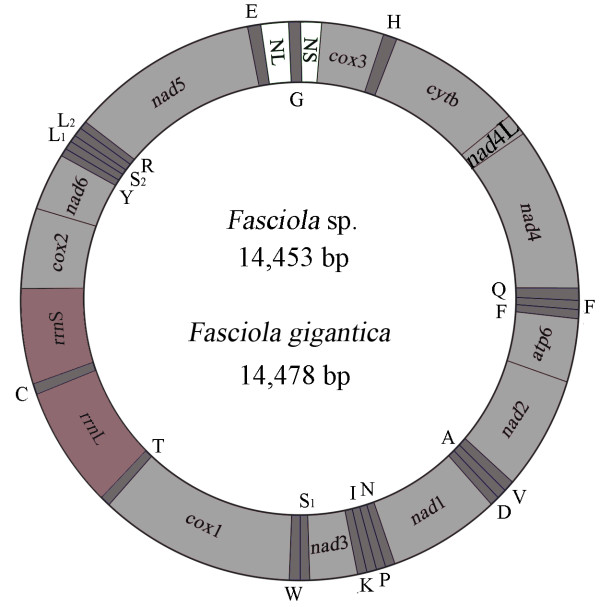

The complete mt genome sequences representing Fasciola sp. (GenBank accession no. KF543343) and F. gigantica (accession no. KF543342) were 14,453 bp and 14,478 bp in size, respectively. Each mt genome contains 12 protein-coding genes (cox1-3, nad1-6, nad4L, cytb and atp6), 22 transfer RNA genes and two ribosomal RNA genes (rrnS and rrnL), but lack an atp8 gene (Figure 1). The mt genome arrangement of the two flukes is the same as that of F. hepatica[26], but as expected, distinct from Schistosoma spp. [36]. All genes are transcribed in the same direction and have a high A + T content (62.7%). The AT-rich regions of both mt genomes are located between tRNA-Glu and tRNA-Gly, and tRNA-Gly and cox3.

Figure 1.

Structure of the mitochondrial genomes of Fasciola sp. and Fasciola gigantica. Genes are designated according to standard nomenclature [26], except for the 22 tRNA genes, which are designated using one-letter amino acid codes, with numerals differentiating each of the two leucine- and serine-specifying tRNAs (L1 and L2 for codon families CUN and UUR, respectively; S1 and S2 for codon families AGN and UCN, respectively). Large non-coding region (NS); small non-coding region (NL).

Annotation

For the two liver flukes, the protein-coding genes were in the following order: nad5 > cox1 > nad4 > cytb > nad1 > nad2 > cox3 > cox2 > atp6 > nad6 > nad3 > nad4L, and the lengths of the all protein-coding genes are the same for Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica (Table 3). The inferred nucleotide and amino acid sequences of each of the 12 mt proteins of two liver flukes were compared. A total of 3,356 amino acids are encoded in the both mt genomes. All protein-coding genes have ATG, TTG or GTG as their initiation codon (Table 3). All protein-coding genes have TAG as their termination codon, except for cox3 and nad3, which have TAA in Fasciola sp. (Table 3). No abbreviated stop codons, such as TA or T, were detected. Twenty-two tRNA genes were predicted from the mt genomes of the two liver flukes, and varied from 55 to 69 bp in size. Of all tRNA genes, 20 can be folded into the conventional four-arm cloverleaf structures. The tRNA-tRNA-Ser(UCN) and tRNA-Ser(AGN) show unorthodox structures; their D-arms are unpaired and replaced by the loops of 8–11 bp.

Table 3.

The organization of the mt genomes of Fasciola sp., Fasciola gigantica and F. hepatica

| Genes |

Positions and nt sequence lengths (bp) |

Ini/Ter codons |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasciola sp. | Fasciola gigantica | Fasciola hepatica | Fasciola sp. | Fasciola gigantica | Fasciola hepatica | |

|

cox3 |

1-642 |

1-642 |

1-642 |

ATG/TAA |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

| tRNA-His |

650 -713 (64) |

650-713 (64) |

650-713 (64) |

|

|

|

|

cytb |

715-1827 |

715-1827 (62) |

715-1827 |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

|

nad4L |

1836-2108 |

1836-2108 |

1836-2108 |

GTG/TAG |

GTG/TAG |

GTG/TAG |

|

nad4 |

2069-3337 |

2069-3337 |

2069-3340 |

GTG/TAG |

GTG/TAG |

GTG/TAA |

| tRNA-Gln |

3339-3404 (66) |

3339-3404 (66) |

3342-3404 (63) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Phe |

3420-3484 (65) |

3417-3481 (65) |

3417-3482 (66) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Met |

3491-3556 (66) |

3488-3553 (66) |

3494-3561 (68) |

|

|

|

|

atp6 |

3557-4075 |

3554-4072 |

3562-4080 |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

|

nad2 |

4088-4954 |

4085-4951 |

4093-4959 |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

| tRNA-Val |

4959-5021 (63) |

4957-5020 (64) |

4965-5027 (63) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Ala |

5035-5099 (65) |

5035-5099 (65) |

5042-5104 (63) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Asp |

5103-5167 (65) |

5103-5167 (65) |

5107-5172 (66) |

|

|

|

|

nad1 |

5171-6073 |

5171-6073 |

5176-6078 |

GTG/TAG |

GTG/TAG |

GTG/TAG |

| tRNA-Asn |

6079-6146 (68) |

6084-6153 (70) |

6089-6158 (70) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Pro |

6152-6220 (69) |

6163-6230 (68) |

6168-6234 (67) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Ile |

6221-6282 (62) |

6231-6292 (62) |

6235-6296 (62) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Lys |

6287-6352 (66) |

6297-6363 (67) |

6301-6367 (67) |

|

|

|

|

nad3 |

6353-6709 |

6364-6720 |

6368-6724 |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

| tRNA-SerUCN |

6714-6768 (55) |

6725-6780 (56) |

6731-6788 (58) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Trp |

6771-6833 (63) |

6790-6852 (63) |

6796-6858 (63) |

|

|

|

|

cox1 |

6837-8378 |

6865-8397 |

6871-8403 |

GTG/TAG |

GTG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

| tRNA-Thr |

8391-8458 (68) |

8419-8486 (68) |

8420-8488 (69) |

|

|

|

|

rrnL |

8460-9445 |

8488-9473 |

8489-9475 |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Cys |

9446-9510 (65) |

9474-9538 (65) |

9476-9538 (63) |

|

|

|

|

rrnS |

9511-10279 |

9539-10309 |

9539-10304 |

|

|

|

|

cox2 |

10280-10882 |

10310-10912 |

10305-10907 |

ATG/TAA |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

|

nad6 |

10929-11381 |

10959-11411 |

10950-11402 |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

ATG/TAG |

| tRNA-Tyr |

11389-11445 (57) |

11419-11475 (57) |

11411-11467 (67) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-LeuCUN |

11456-11520 (65) |

11486-11550 (65) |

11478-11543 (66) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-SerAGN |

11521-11579 (59) |

11551-11607 (57) |

11542-11603 (62) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-LeuUUR |

11588-11651 (64) |

11616-11678 (63) |

11609-11673 (64) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Arg |

11653-11718 (66) |

11680-11745 (66) |

11673-11738 (66) |

|

|

|

|

nad5 |

11720-13282 |

11747-13309 |

11737-13305 |

TTG/TAG |

TTG/TAG |

GTG/TAG |

| tRNA-Glu |

13305-13372 (68) |

13332-13399 (68) |

13327-13395 (69) |

|

|

|

| Short non-coding region |

13373-13548 (176) |

13400-13573 (174) |

13396-13582 (187) |

|

|

|

| tRNA-Gly |

13549-13612 (64) |

13574-13637 (64) |

13583-13645 (63) |

|

|

|

| Long non-coding region | 13613-14453 (841) | 13638-14478 (841) | 13646-14462 (817) | |||

The two ribosomal RNA genes (rrnL and rrnS) of Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica were inferred based on comparisons with sequences from those of F. hepatica. The rrnL of Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica is located between tRNA-Thr and tRNA-Cys, and rrnS is located between tRNA-Cys and cox2. The length of rrnL is 987 bp for both Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica. The size of the rrnS genes is 769 bp and 771 bp for Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica, respectively. The A + T contents of rrnL and rrnS are ~ 62% and ~ 61% for Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica, respectively.

Two AT-rich non-coding regions (NCR) in the mt genomes Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica were inferred. In both mt genomes, the long NCR (841 bp) is located between the tRNA-Gly and cox3 (Figure 1), has an A + T content of ~53% and contains eight perfect, 86 bp tandem repeats (TR1 to TR8). The short NCR is 174–176 bp in length, is located between tRNA-Glu and tRNA-Gly (Figure 1) and has an A + T content of ~ 72%.

Comparative mt genomic analyses of Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica with F. hepatica

The complete mt genome sequences representing Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica are 9 bp shorter and 16 bp longer than F. hepatica (14,462 bp in length) [26], respectively. A comparison of the nucleotide sequences of each mt gene, and the amino acid sequences, conceptually translated from all mt protein-encoding genes of the three flukes, is given in Table 4. Across the entire mt genome, the sequence difference was 2.6% (380 nucleotide substitutions) between Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica, 11.8% (1712 nucleotide substitutions) between Fasciola sp. and F. hepatica, and 11.8% (1714 nucleotide substitutions) between F. gigantica and F. hepatica. The difference across both nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the 12 protein-coding was 11.6% (1167 nucleotide substitutions) and 9.54% (320 amino acid substitutions) between the Fasciola sp. and F. hepatica; 11.6% (1167 nucleotide substitutions) and 9.83% (330 amino acid substitutions) between the F. gigantica and F. hepatica; and 2.8% (281 nucleotide substitutions) and 2.1% (71 amino acid substitutions) between the Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica, respectively.

Table 4.

Nucleotide (nt) and/or predicted amino acid (aa) sequence differences in each mt gene among Fasciola sp. (F), Fasciola gigantica (Fg) and F. hepatica (Fh) upon pairwise comparison

| Gene/region |

Nt sequence length |

Nt difference (%) |

Number of aa |

aa difference (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Fg | Fh | F/Fg | F/Fh | Fg/Fh | F | Fg | Fh | F /Fg | F/Fh | Fg/Fh | |

|

atp6 |

519 |

519 |

519 |

2.89 |

15.22 |

13.87 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

1.74 |

15.12 |

13.95 |

|

nad1 |

903 |

903 |

903 |

3.10 |

8.86 |

8.42 |

300 |

300 |

300 |

2.67 |

7.67 |

8.0 |

|

nad2 |

867 |

867 |

867 |

3.69 |

11.42 |

11.65 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

1.74 |

11.81 |

11.81 |

|

nad3 |

357 |

357 |

357 |

5.60 |

10.64 |

10.64 |

118 |

118 |

118 |

0.85 |

7.63 |

7.63 |

|

nad4 |

1269 |

1269 |

1272 |

3.86 |

13.99 |

13.68 |

422 |

422 |

423 |

3.08 |

11.58 |

11.11 |

|

nad4L |

273 |

273 |

273 |

1.83 |

8.79 |

8.42 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

2.22 |

5.56 |

5.56 |

|

nad5 |

1563 |

1563 |

1569 |

1.86 |

13.58 |

14.02 |

520 |

520 |

522 |

1.35 |

12.45 |

12.45 |

|

nad6 |

453 |

453 |

453 |

3.97 |

13.91 |

16.34 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

7.33 |

8.00 |

14.67 |

|

cox1 |

1542 |

1542 |

1533 |

2.02 |

9.39 |

9.13 |

513 |

513 |

510 |

1.37 |

6.08 |

5.49 |

|

cox2 |

603 |

603 |

603 |

2.16 |

11.11 |

11.61 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

0.50 |

7.00 |

7.50 |

|

cox3 |

642 |

642 |

642 |

2.80 |

13.86 |

13.40 |

213 |

213 |

213 |

2.82 |

14.55 |

14.55 |

|

cytb |

1113 |

1113 |

1113 |

2.07 |

8.36 |

8.36 |

370 |

370 |

370 |

1.89 |

6.22 |

7.03 |

|

rrnS |

769 |

771 |

766 |

1.30 |

11.31 |

11.41 |

|

- |

- |

|

- |

|

|

rrnL |

986 |

986 |

987 |

1.01 |

9.93 |

10.13 |

|

- |

- |

|

- |

|

| 22 tRNAs | 1413 | 1414 | 1420 | 2.26 | 10.28 | 10.63 | ||||||

Nucleotide variability in the mt genome among Fasciola sp., F. gigantica and F. hepatica

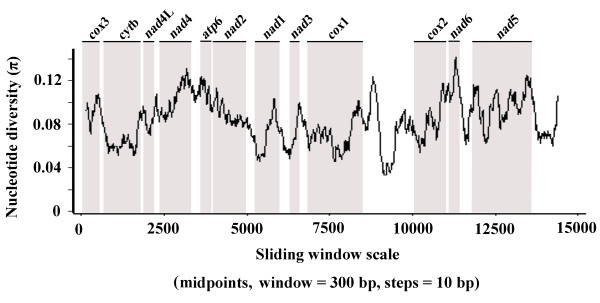

Sliding window analysis across the mt genomes of Fasciola sp., F. gigantica and F. hepatica provided an estimation of nucleotide diversity Pi (π) for individual mt genes (Figure 2). By computing the number of variable positions per unit length of gene, the sliding window indicated that the highest and lowest levels of sequence variability were within the genes nad6 and cytb, respectively. Conserved regions were identified within nad1 and cox1 genes. In this study, the cytb and nad1 genes are the most conserved protein-coding genes, and nad6, nad5 and nad4 are the least conserved.

Figure 2.

Sliding window analysis of complete mt genome sequences of Fasciola sp., Fasciola gigantica and F. hepatica. The black line indicates nucleotide diversity in a window of 300 bp (10 bp-steps). Gene regions (grey) and boundaries are indicated.

Phylogenetic analysis

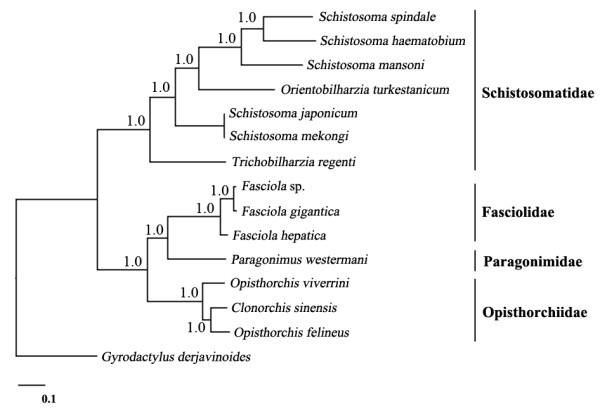

Phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated amino acid sequence data for all 12 mt proteins (Figure 3) showed that the Fasciolidae clustered to the exclusion of representatives of the families Paragonimidae (P. westermani) and Opisthorchiidae (O. viverrini, O. felineus and C. sinensis); the Schistosomatidae clustered separately with strong nodal support (posterior probability (pp) = 1.0). Within the Fasciolidae, Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica clustered together with strong support (pp = 1.0), to the exclusion of F. hepatica, with the former two taxa being more closely related than either was to F. hepatica. In addition, phylogenetic analysis using the nad1 data supports clustering of the Fasciola sp. with aspermic F. gigantica x F. hepatica hybrids characterised previously [42] (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Genetic relationships of Fasciola sp. with Fasciola gigantica and F. hepatica, and other trematodes. Phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated amino acid sequence data representing 12 protein-coding genes was conducted using Bayesian inference (BI), using Gyrodactylus derjavinoides (NC_010976) as an outgroup.

Discussion

The present comparative, genetic investigation of representative specimens of Fasciola sp. (i.e. the ‘intermediate form’), F. gigantica and F. hepatica using whole mt genomic and protein sequence data sets showed that Fasciola sp. and F. gigantica were more closely related than either was to F. hepatica. This finding was also supported by an analysis of nad1 sequence data (cf. Additional file 2: Figure S2). Although this evidence might suggest that Fasciola sp. is a population variant of F. gigantica, previous studies [19-21] have proposed that Fasciola sp. is a hybrid of F. gigantica and F. hepatica. The combined use of mtDNA (if indeed maternally inherited in fasciolids) and nuclear DNA markers [43] should assist in exploring the “hybridization/speciation” hypotheses [44]. Clearly, there is consistent evidence from various studies [11,12,14] of mixed ITS-1 and ITS-2 sequence types, representing both F. gigantica and F. hepatica among the multiple rDNA copies, within individual specimens of Fasciola sp. (i.e., the ‘intermediate form’). Although the number or proportion(s) of different sequence types within individual adults of Fasciola sp. has not yet been estimated using a mutation scanning- or cloning-based sequencing [45], the polymorphic positions in the sequences determined by direct sequencing [11,14] indicate a clear pattern of introgression between the F. gigantica and F. hepatica. Although mt genomic (11.8%) and inferred protein (9.83%) sequence differences between these two species is substantial, the explanation that Fasciola sp. represents a hybrid between these two recognized species seems plausible, given that the karyotypes of both diploid F. hepatica and F. gigantica are the same (2n = 20) [46,47] and that the magnitude of sequence variation (1.7%) in ITS-2 (a species marker) between F. gigantica and F. hepatica is comparable with the highest level (1.3-1.6%) in this rDNA region between some schistosome species for which hybrids (i.e. S. haematobium × S. bovis; S. haematobium × S. guineenis; S. haematobium × S. intercalatum) have been reported [48-50]. While hybridization seems possible, another explanation might be ITS rDNA "lineage sorting and retention of ancestral polymorphism" [51,52], but this is perhaps less likely, given a clear pattern of mixing of ITS sequences seen in Fasciola sp. (cf. Additional file 1: Figure S1).

In addition, polyploidy or diploidy in aspermic Fasciola[20] needs to be considered, and warrants future investigation. Perhaps the aspermic Fasciola specimens described in the literature [53] were infertile hybrids of F. gigantica and F. hepatica (in situations where both species occur in sympatry). Questions that might be addressed directly in relation to Fasciola sp. are: Are eggs from Fasciola sp. fertilized and viable? If miracidia develop and emerge from these eggs, are they infective to snails? If they do infect snails, do the ensuing adult worms (in the definitive host) contain sperm and are these worms fertile, and what is their ploidy? These questions should be addressed, and could be complemented by detailed light and transmission electron microscopic investigations of a relatively large number of adult specimens of Fasciola sp., F. gigantica and F. hepatica (preferably from different countries), which have been unequivocally and individually identified based on their ITS-1 and ITS-2 sequences. Such a study should pay particular attention to the morphology of the reproductive organs, sperm and oocytes, and the karyotypes of worms, and establish whether or not Fasciola sp. from China is polyploid and/or aspermic [20].

Moreover, although challenging, laborious and time-consuming, it would be highly informative to conduct hybridization studies in vivo, whereby individual miracidia from eggs from adults of each Fasciola sp., F. gigantica and F. hepatica would be used to infect (separately) their lymnaeid snail hosts, to raise clonal populations of cercariae and metacercariae of these three taxa, so that mixed infections (in different combinations and with mono-specific controls) could be established in, for example, sheep or goats, to attempt to cross-hybridize the three taxa in a pairwise manner. Using such an experimental design, eggs and adult worms could then be examined in detail at both the electron microscopic, karyotypic and molecular levels. Importantly, in these experiments, ITS-1 and/or ITS-2 could be used to establish the genotypes of subsamples of individuals, and mt markers derived from mt genomes determined here and of F. hepatica could be used to determine haplotypes and mtDNA inheritance if the cross-hybridization studies were successful. Therefore, the present markers could be employed, in combination, to establish the biological relationship of the three taxa through in vivo experiments, but also in the field in sympatric and allopatric populations, if they occur. Combined with the use of markers in nuclear and mt genomes, advanced genomic sequencing, optical mapping and micro-imaging techniques might assist studies of Fasciola sp. in China and other countries.

Conclusion

The findings of this study provide robust genetic evidence that Fasciola sp. is more closely related to F. gigantica than to F. hepatica. The mtDNA datasets reported in the present study should provide useful novel markers for further studies of the taxonomy and systematics of Fasciola from different hosts and geographical regions.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GHL, NY, HQS and LA performed the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted parts of the manuscript. XQZ and RBG revised and edited the manuscript and funded the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Polymorphic positions in the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS-1 and ITS-2) of nuclear ribosomal DNA of Fasciola sp.

Phylogenetic tree of Fasciola spp. inferred from the mitochondrial nad1 sequence data by Bayesian inference (BI). Fascioloides magna was used as an outgroup. Nodal support values were determined from the final 75% of trees using a sampling frequency of 100.

Contributor Information

Guo-Hua Liu, Email: liuguohua5202008@163.com.

Robin B Gasser, Email: robinbg@unimelb.edu.au.

Neil D Young, Email: nyoung@unimelb.edu.au.

Hui-Qun Song, Email: songhuiqun@caas.cn.

Lin Ai, Email: 252120016@qq.com.

Xing-Quan Zhu, Email: xingquanzhu1@hotmail.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (Grant No. 2013DFA31840), the “Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest” (Grant No. 201303037), and the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of Gansu Province (Grant No. 1210RJIA006). RBG’s research is supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC), National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Melbourne Water Corporation (MWC); the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation is also gratefully acknowledged. This study was also supported by a Victorian Life Sciences Computation Initiative (VLSCI) grant number VR0007 on its Peak Computing Facility at the University of Melbourne, an initiative of the Victorian Government. NDY is an NHMRC Early Career Research Fellow.

References

- Fürst T, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Global burden of human food-borne trematodiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:210–221. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripa B. Global burden of food-borne trematodiasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:171–172. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA. Fascioliasis and other plant-borne trematode zoonoses. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1255–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Chen N, Zhang RL, Lin RQ, Zhu XQ. Food-borne parasitic zoonoses in China: perspective for control. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai L, Chen MX, Alasaad S, Elsheikha HM, Li J, Li HL, Lin RQ, Zou FC, Zhu XQ, Chen JX. Genetic characterization, species differentiation and detection of Fasciola spp. by molecular approaches. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:101. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser J, Engels D, Büscher G, Utzinger J. Triclabendazole for the treatment of fascioliasis and paragonimiasis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:1513–1526. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan GP, Fairweather I, Trudgett A, Hoey E, McCoy, McConville M, Meaney M, Robinson M, McFerran N, Ryan L, Lanusse C, Mottier L, Alvarez L, Solana H, Virkel G, Brophy PM. Understanding triclabendazole resistance. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;82:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneberg P. Phylogenetic data suggest the reclassification of Fasciola jacksoni (Digenea: Fasciolidae) as Fascioloides jacksoni comb. nov. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:1679–1689. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PV, Subramanyam S. Chromosome studies in the liver fluke, Fasciola gigantica Cobbold, 1856, from Andra Pradesh. Curr Sci. 1973;42:288–291. [Google Scholar]

- Periago MV, Valero MA, El Sayed M, Ashrafi K, El Wakeel A, Mohamed MY, Desquesnes M, Curtale F, Mas-Coma S. First phenotypic description of Fasciola hepatica/Fasciola gigantica intermediate forms from the human endemic area of the Nile Delta, Egypt. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H, Ai L, Song HQ, Ali S, Lin RQ, Seyni B, Issa G, Zhu XQ. Genetic characterisation of Fasciola samples from different host species and geographical localities revealed the existence of F. hepatica and F. gigantica in Niger. Parasitol Res. 2008;102:1021–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0870-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WY, He B, Wang CR, Zhu XQ. Characterisation of Fasciola species from Mainland China by ITS-2 ribosomal DNA sequence. Vet Parasitol. 2004;120:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai L, Weng YB, Elsheikha HM, Zhao GH, Alasaad S, Chen JX, Li J, Li HL, Wang CR, Chen MX, Lin RQ, Zhu XQ. Genetic diversity and relatedness of Fasciola spp. isolates from different hosts and geographic regions revealed by analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences. Vet Parasitol. 2011;181:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe SE, Kang TG, Kweon CH, Kang SW. Genetic analysis of Fasciola isolates from cattle in Korea based on second internal transcribed spacer (ITS-2) sequence of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:833–839. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor N, Halajian A, Farjallah S, Merella P, Said K, Ben Slimane B. Molecular characterization of Fasciola spp. from the endemic area of northern Iran based on nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Exp Parasitol. 2011;128:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itagaki T, Kikawa M, Sakaguchi K, Shimo J, Terasaki K, Shibahara T, Fukuda K. Genetic characterization of parthenogenic Fasciola sp. in Japan on the basis of the sequences of ribosomal and mitochondrial DNA. Parasitology. 2005;131:679–685. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasaad S, Huang CQ, Li QY, Granados JE, García-Romero C, Pérez JM, Zhu XQ. Characterization of Fasciola samples from different host species and geographical localities in Spain by sequences of internal transcribed spacers of rDNA. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1245–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0628-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farjallah S, Sanna D, Amor N, Ben Mehel B, Piras MC, Merella P, Casu M, Curini-Galletti M, Said K, Garippa G. Genetic characterization of Fasciola hepatica from Tunisia and Algeria based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:1617–1621. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1601-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agatsuma T, Arakawa Y, Iwagami M, Honzako Y, Cahyaningsih U, Kang SY, Hong SJ. Molecular evidence of natural hybridization between Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. Parasitol Int. 2000;49:231–238. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5769(00)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itagaki T, Arakawa Y, Iwagami M, Honzako Y, Cahyaningsih U, Kang SY, Hong SJ. Occurrence of spermic diploid and aspermic triploid forms of Fasciola in Vietnam and their molecular characterization based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TH, De NV, Agatsuma T, Thi Nguyen TG, Nguyen QD, McManus DP, Blair D. Human fascioliasis and the presence of hybrid/introgressed forms of Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica in Vietnam. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:725–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, Blair D, McManus DP. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:165–173. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90109-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GH, Gasser RB, Su A, Nejsum P, Peng L, Lin RQ, Li MW, Xu MJ, Zhu XQ. Clear genetic distinctiveness between human- and pig-derived Trichuris based on analyses of mitochondrial datasets. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Jex AR, Campbell BE, Gasser RB. Long PCR amplification of the entire mitochondrial genome from individual helminths for direct sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2339–2344. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The Clustal X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TH, Blair D, McManus DP. Complete DNA sequence and gene organization of the mitochondrial genome of the liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica L. (Platyhelminthes; Trematoda) Parasitology. 2001;123:609–621. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001008733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Chilton NB, Gasser RB. The mitochondrial genomes of the human hookworms, Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus (Nematoda: Secernentea) Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:145–158. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhovtsov SV, Katokhin AV, Kolchanov NA, Mordvinov VA. The complete mitochondrial genomes of the liver flukes Opisthorchis felineus and Clonorchis sinensis (Trematoda) Parasitol Int. 2010;59:100–103. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai XQ, Liu GH, Song HQ, Wu CY, Zou FC, Yan HK, Yuan ZG, Lin RQ, Zhu XQ. Sequences and gene organization of the mitochondrial genomes of the liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis (Trematoda) Parasitol Res. 2012;110:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster BL, Rudolfová J, Horák P, Littlewood DT. The complete mitochondrial genome of the bird schistosome Trichobilharzia regenti (Platyhelminthes: Digenea), causative agent of cercarial dermatitis. J Parasitol. 2007;93:553–561. doi: 10.1645/GE-1072R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang CR, Zhao GH, Gao JF, Li MW, Zhu XQ. The complete mitochondrial genome of Orientobilharzia turkestanicum supports its affinity with African Schistosoma spp. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:1964–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TH, Blair D, Agatsuma T, Humair PF, Campbell NJ, Iwagami M, Littlewood DT, Peacock B, Johnston DA, Bartley J, Rollinson D, Herniou EA, Zarlenga DS, McManus DP. Phylogenies inferred from mitochondrial gene orders-a cautionary tale from the parasitic flatworms. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1123–1125. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GH, Li J, Song HQ, Li XY, Chen F, Lin RQ, Yuan ZG, Weng YB, Hu M, Zou FC, Zhu XQ. A specific PCR assay for the identification and differentiation of Schistosoma japonicum geographical isolates in mainland China based on analysis of mitochondrial genome sequences. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood DT, Lockyer AE, Webster BL, Johnston DA, Le TH. The complete mitochondrial genomes of Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma spindale and the evolutionary history of mitochondrial genome changes among parasitic flatworms. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;39:452–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyse T, Buchmann K, Littlewood DT. The mitochondrial genome of Gyrodactylus derjavinoides (Platyhelminthes: Monogenea)–a mitogenomic approach for Gyrodactylus species and strain identification. Gene. 2008;417:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GH, Wang SY, Huang WY, Zhao GH, Wei SJ, Song HQ, Xu MJ, Lin RQ, Zhou DH, Zhu XQ. The complete mitochondrial genome of Galba pervia (Gastropoda: Mollusca), an intermediate host snail of Fasciola spp. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RD. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Ichinomiya M, Ohtori M, Ichikawa M, Shibahara T, Itagaki T. Molecular characterization of Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica, and aspermic Fasciola sp. in China based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:809–815. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Coma S, Valero MA, Bargues MD. Chapter 2. Fasciola, lymnaeids and human fascioliasis, with a global overview on disease transmission, epidemiology, evolutionary genetics, molecular epidemiology and control. Adv Parasitol. 2009;69:41–146. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(09)69002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaoka T, Okamoto H, Araki K, Nagoya H, Fujiwara A, Kobayashi T. Identification of the hybrid between Oryzias latipes and Oryzias curvinotus using nuclear genes and mitochondrial gene region. Mar Genomics. 2012;7:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser RB. Mutation scanning methods for the analysis of parasite genes. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:1449–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(97)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reblánová M, Spakulová M, Orosová M, Králová-Hromadová I, Bazsalovicsová E, Rajský D. A comparative study of karyotypes and chromosomal location of rDNA genes in important liver flukes Fasciola hepatica and Fascioloides magna (Trematoda: Fasciolidae) Parasitol Res. 2011;109:1021–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2339-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srimuzipo P, Komalamisra C, Choochote W, Jitpakdi A, Vanichthanakorn P, Keha P, Riyong D, Sukontasan K, Komalamisra N, Sukontasan K, Tippawangkosol P. Comparative morphometry, morphology of egg and adult surface topography under light and scanning electron microscopies, and metaphase karyotype among three size-races of Fasciola gigantica in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:366–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagès JR, Southgate VR, Tchuem Tchuenté LA, Jourdane J. Experimental evidence of hybrid breakdown between the two geographical strains of Schistosoma intercalatum. Parasitology. 2002;124:169–175. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster BL, Diaw OT, Seye MM, Webster JP, Rollinson D. Introgressive hybridization of Schistosoma haematobium group species in Senegal: species barrier break down between ruminant and human schistosomes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moné H, Minguez S, Ibikounlé M, Allienne JF, Massougbodji A, Mouahid G. Natural Interactions between S. haematobium and S. guineensis in the Republic of Benin. Sci World J. 2012;2012:793420. doi: 10.1100/2012/793420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TJ. The dangers of using single locus markers in parasite epidemiology: Ascaris as a case study. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:183–188. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01944-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Yuan K, Zhou X, Hu M, Abs EL-Osta YG, Gasser RB. Molecular epidemiological investigation of Ascaris genotypes in China based on single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of ribosomal DNA. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:2308–2315. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itagaki T, Ichinomiya M, Fukuda K, Fusyuku S, Carmona C. Hybridization experiments indicate incomplete reproductive isolating mechanism between Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica. Parasitology. 2011;138:1278–1284. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Polymorphic positions in the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS-1 and ITS-2) of nuclear ribosomal DNA of Fasciola sp.

Phylogenetic tree of Fasciola spp. inferred from the mitochondrial nad1 sequence data by Bayesian inference (BI). Fascioloides magna was used as an outgroup. Nodal support values were determined from the final 75% of trees using a sampling frequency of 100.