Abstract

The obesity epidemic and associated chronic diseases are often attributed to modern lifestyles. The term “lifestyle” however, ignores broader social, economic, and environmental determinants while inadvertently “blaming the victim.” Seen more eclectically, lifestyle encompasses distal, medial, and proximal determinants. Hence any analysis of causality should include all these levels. The term “anthropogens,” or “…man-made environments, their by-products and/or lifestyles encouraged by these, some of which may be detrimental to human health” provides a monocausal focus for chronic diseases similar to that which the germ theory afforded infectious diseases. Anthropogens have in common an ability to induce a form of chronic, low-level systemic inflammation (“metaflammation”). A review of anthropogens, based on inducers with a metaflammatory association, is conducted here, together with the evidence for each in connection with a number of chronic diseases. This suggests a broader view of lifestyle and a focus on determinants, rather than obesity and lifestyle per se as the specific causes of modern chronic disease. Under such an analysis, obesity is seen more as “a canary in a mineshaft” signaling problems in the broader environment, suggesting that population obesity management should be focused more upstream if chronic diseases are to be better managed.

1. Introduction

Modern western lifestyles are often blamed for the current obesity and associated chronic disease pandemics [1]. This seems plausible as such problems, at a population level, only really began 3-4 decades ago [2]. They are also not usually caused by any microbial agent and have occurred too quickly for genome changes to be a factor [2] (although this does not preclude environmental influences on gene expression). The increased aging of the population is a consideration, but increased risk factors across all age groups limit aging as a sole explanation [3]. Other behaviors [4] and environmental factors [5] have been implicated, but a single causal underpinning is illusive, thus making “lifestyle” an attractive proposition.

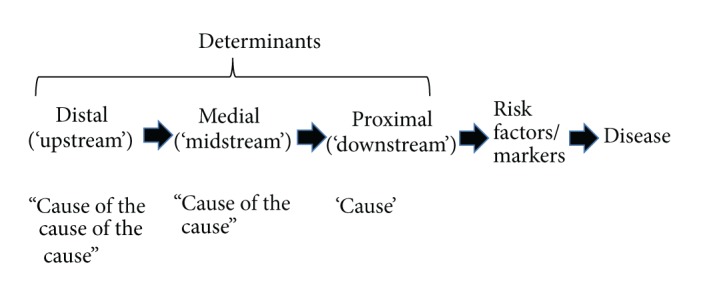

However, lifestyle (“a mode of life chosen by a person or group”-Macquarie Dictionary) infers volitional behavior on the part of an individual. This has a pejorative meaning for some social scientists as it is thought to ignore the deeper social, economic, and environmental determinants of both lifestyle and disease, while focusing on individual responsibility, that is, “victim blaming” [6]. A more holistic view would involve not only looking at the “cause” of a disease, but also, as Rose has pointed out in [7], looking at the “cause of the cause,” and even the “cause of the cause of the cause.” This is particularly relevant for an understanding of the chronic, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) often linked to obesity, in contrast to infectious/communicable diseases that have prevailed historically [8].

Infectious diseases benefited from a monocausal focus [9] provided by the “germ theory,” which culminated in improvements in public health, hygiene, immunization, and the development of antibiotics in the early 20th century [10].

Chronic diseases began to replace the decline in infections in the west in the late 20th century, taking health experts somewhat by surprise. Epidemiologists noted a phase in the development of a country called the “epidemiological transition” [11] when chronic diseases take over from infections as the main disease burden. This occurred in the 1970s and 1980s for many developed economies in North America, Europe, and the Asian-Pacific region and is currently occurring in others, such as Brazil, Russia, India, and China. The double-edged sword of progress, which facilitated control over infectious diseases, instigated an unhealthy trend in chronic diseases. The worldwide rise in obesity has been an accompaniment to this.

2. Causality in Disease

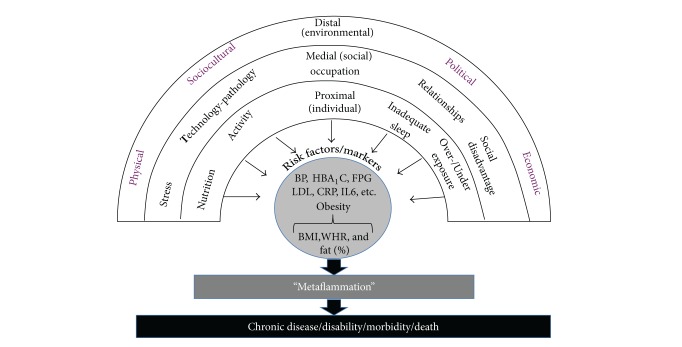

While infectious disease can usually be ascribed to microbial causes, causality in NCDs is more problematic. In most cases the agent of causality is ill-defined, but there are layers of influence. As shown in Figure 1, most immediate to the disease are risk factors, which, in turn, are influenced by drivers or determinants at different levels from proximal or “downstream” (i.e., more immediate to the disease) to medial and then distal or “upstream.” Heart disease for example has proximal determinants of smoking, nutrition, and inactivity, medial determinants of peer pressure and food and exercise environments, and distal determinants of economic and social policies.

Figure 1.

A hierarchy of determinants and risk factors/markers in chronic disease aetiology.

Unlike the germ theory for communicable diseases, there has been no equivalent underlying link between the determinants shown in Figure 1 and chronic diseases. Such a revelation is unlikely to solve the chronic disease problem. However it could help rationalize treatment resources and mitigate the inevitable disabilities and morbidities associated with aging.

The discovery, in the 1990s, of a “new” form of inflammation, which appears to be present in many if not all chronic diseases, offers the prospect of an underlying generic disease marker pointing to determinants beyond the diverse explanations of aging and lifestyle. The term “metaflammation” [12] has been used to define a form of low-grade, chronic, and systemic inflammation, originally ascribed to obesity [13]. Subsequent research has shown that metaflammation is not limited to obesity, but associated with other lifestyle and environmental “inducers” [14], examples of which have been linked, either directly or indirectly to certain chronic diseases and conditions like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, respiratory problems, many forms of cancer, and even depression and dementia [12, 15]. Metaflammation appears to be part of a metabolic cascade, including cellular oxidative stress and insulin resistance, which induces allostatic overload, dysmetabolism, and ultimately chronic disease [16]. This raises the question of whether obesity is a necessary condition for the chronic diseases with which it is associated or just a sufficient condition in some circumstance and whether lifestyle and environmental inducers which may (or may not) lead to obesity can be independent determinants of disease as indicated by metaflammatory processes.

Inducers of metaflammation, which have largely arisen since the industrial revolution [17, 18], have been labeled “anthropogens,” or “…man-made environments, their by-products and/or lifestyles encouraged by these, some of which may be detrimental to human health” [19]. Anthropogens incite a low level, but persistent immune response to a not-immediately life-threatening situation, which can become dysmetabolic when exposure is chronic. Because such a response is undifferentiated, the outcome is systemic rather than localized.

An individual's susceptibility to a range of anthropogens clearly varies with genetic predisposition to chronic diseases carried through the genome including obesity, diabetes, many cancers, and cardiovascular disease. However, during the second half of the 20th century, a revolution in our understanding of environmental influences and lifelong gene expression has emphasized the importance of early environmental influences on the later development of chronic disease. It is now clear that epigenetics, the heritable changes in gene activity not driven by change in the DNA sequence, has a major influence on the susceptibility to chronic disease for both individuals and their offspring. Chronic disease driven by a mismatch between the environment one is programmed for and the environment one is born into is highlighted by the extreme susceptibility of indigenous and developing communities to anthropogens and related chronic diseases.

Obviously, not all anthropogens are unhealthy for all people. The identification of those that have negative health effects however is important for developing a focus on chronic disease aetiology. We consider that a review of anthropogens could focus the attention of health workers and hence provide such a review below. We provide evidence of metaflammatory reactions from either inadequate or excessive exposure to these and evidence for their association with a number of chronic diseases. A list of disease categories is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chronic disease categories with lifestyle/environmental determinants.

| (1) Cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases | |

| (2) Cancers with lifestyle component | |

| (3) Endocrine/metabolic disorders | |

| (4) Gastrointestinal diseases | |

| (5) Kidney disease | |

| (6) Mental/CNS health | |

| (7) Musculoskeletal disorders | |

| (8) Respiratory diseases | |

| (9) Reproductive disorders | |

| (10) Dermatological disorders |

A summary of anthropogens associated with these disease categories, discussed in the text, is given in Table 2 using the acronym NASTIE ODOURS.

Table 2.

Lifestyle and environmental determinants (“anthropogens”) for chronic disease. Numbers refer to chronic disease categories (from Table 1) for which there is supporting evidence referred to in the text.

| Determinants | Decreases risk | Increases risk | Moderators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

Fruit/vegetables Dietary fibre Whole grains Food variety Seafood Healthy eating patterns |

High total energy High energy density Excess processed foods High GI foods Sat./trans fats Sugars Salt Excessive alcohol Sugared soft drinks Processed/red meat |

Binge eating/drinking Social/holiday eating “Restrained” eating Feasting Culture Habits |

|

| |||

|

(In)Activity 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

Aerobic exercise Resistance exercise Stretching Stability Leisure activity Incidental activity |

Sitting/sedentary work Overexercise |

Fear of crime Fatigue/laziness Discomfort/injury/ Early experiences Energy-saving devices Obesity Habits |

|

| |||

| Stress, anxiety, and depression 1, 3, 4, 9 |

Exercise/fitness Healthy nutrition Perceived control Self-efficacy Coping skills Meaning |

Overload “Learned helplessness” Early trauma Boredom Caffeine/drug use |

Peer/social/pressure Uncontrollable thoughts Worry Fear of the unknown Obesity |

|

| |||

| Technology-induced-pathology 7, 10 |

Motor vehicle use Machinery TV/small screens Repetitive actions Noise pollution Processed foods Weapons of war |

Peer/social pressure Legislation/regulation Habits |

|

|

| |||

| Inadequate sleep 1, 3, 6, 10 |

REM sleep Bed-time Hypersomnia Nutrition Exercise/fitness |

Stress Entertainment Sleep disorders Overheating Interactive media Alcohol/drugs |

Activity before sleep Stress Anxiety/depression Obesity habits |

|

| |||

| Environment 2, 3, 6, 9, 10 |

Political/economic structure Recreational space “Green” exposure Infrastructure for walking and cycling Plant-based nutrition |

Passive influences Second-hand smoke Particle pollution Endocrine disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) Home chemicals Drug-immunity (e.g., antibiotics) |

Social proof “Tipping point” Social/peer pressure Cultural influences Habit |

|

| |||

| Occupation 1, 2, 8, 10 |

Social justice Work equality Security of employment |

Work stress Shift-work Hazard exposure Conflict |

Peer pressure Bullying |

|

| |||

| Drugs, smoking, and alcohol 1–10 |

Appropriate medication | Recreational drugs Cigarette smoking Alcohol use Iatrogenesis |

Stress, anxiety, and depression Peer/social pressure Addiction Binge drinking Habit |

|

| |||

| Over- and underexposure 1, 2, 3 |

Sunlight light stimulation |

Sunlight (excess) Sunlight (inadequate) Low humidity/ asbestos Radiation |

Peer/social pressure Cultural influences Habit |

|

| |||

| Relationships 1, 3, 6 |

Companionship Peer support Maternal support in childhood “Love” |

Interpersonal conflict Loneliness Lack of support |

Peer pressure Early experience |

|

| |||

| Social factors 1–10 |

Trust Income security Market regulation SE status Education |

Inequality Poverty Deregulated markets |

Stress Bullying Cognitive processes Peer/social pressure |

3. Identifying “Anthropogens”

In discussions of modern chronic disease etiology, smoking, poor nutrition, excess weight, and alcohol use stand out as the dominant preventable determinants [20]. However recent research has expanded this considerably to take account of social, cultural, occupational, environmental, and other factors (“anthropogens”) in the hierarchical structure (Figure 1). A list of these is described below. The discussion is not meant to be an extensive review of each topic area but rather to cover the main components of each identified here as being associated with chronic disease and with a common metaflammatory base. Each is also considered in its own right an independent determinant in the absence of obesity or weight gain.

Nutrition. The importance of nutrition for the prevention and management of chronic disease is well known [21]. Inadequate or overnutrition has been proposed to account for up to two-thirds of risk for certain chronic problems like type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [22] and a significant proportion of other chronic ailments [23]. Health problems have been related to both specific nutrients [24] and overall meal patterns [25], with inflammatory biomarkers generally accompanying those foods/eating patterns associated with disease risk in the presence and the absence of obesity [17, 26].

Excessive energy intake, particularly of high energy-dense, but low nutrient-dense products, is a major problem of industrialised societies. Still, excessive intake of even healthy foods can increase postprandial (and potentially chronic) metaflammation [27], suggesting negative long-term outcomes. At the other extreme, chronic energy restriction is now well documented as being associated with increased longevity and improved heath [28].

In relation to nutrition quality, studies have reported increased risk and elevated metaflammation from excessive amounts of sugars, salt, alcohol, and (saturated and trans) fats, as well as inadequate levels of fibre, fruit, vegetables, grains, and certain nutrients [17, 26]. Levels of processing have been proposed as a general indication of risk [29], and there appears to be a clear postprandial “metaflammatory” trail from processed versus whole foods, suggesting an evolutionary role in nutritional health [18, 30, 31]. Although individual and genetic factors influence outcomes [32], the worst-case scenario for obesity and chronic disease based on current evidence would be an excessive amount of a modern, western diet made up of highly processed foods [25]. While there may be controversy over an ideal diet (mediterranean, anti-inflammatory, paleo, etc.), Michael Pollan's [33] dictum to “Eat food. Mostly plants. Not too much”, provides a simple, concise, and accurate long-term nutritional goal.

(In)Activity. Inactivity, as well as sedentary activities like sitting, in contrast to insufficient physical activity, is an independent risk factor for disease [34]. It is one of the major unhealthy anthropogens of our times with links to over 35 different diseases [35].

Movement, physical activity, and exercise can be conceived of as gradations along a scale and all have a role, to different degrees, in primary prevention of a range of diseases and, in some cases, treatment and reversal of risks and/or disease entities (namely, type 2 diabetes). This is mainly through the modems of aerobic capacity and/or muscle strength and integrity. Flexibility and balance provide musculoskeletal integrity that can enhance quality of life.

While controversies exist about type, intensity, frequency, and duration of physical activity, there is no dispute about the health value of an optimal physical activity requirement for humans. A generic prescription based on “volume” (intensity × frequency × duration) incorporating both aerobic and resistance training is appropriate in the absence of a more detailed individual-genetic understanding [36]. In the absence of this, recommendations that “…any activity is better than none, and more is better than a little”, and for individuals to “think of movement as an opportunity, not an inconvenience” [37] are appropriate. The relationship between activity and health has been referred to as a U-shaped function, with excessive exercise having diminishing health benefits as reflected in increased metaflammation, similar to that of inactivity [38, 39].

Poor nutrition and inactivity are the best-known inducers of weight gain. Several studies however now show that either poor nutrition or inactivity can independently modify metaflammation without significant changes in weight [40, 41].

Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. The nature of stress has changed in recent times from an acute warning signal to a chronic strain on physiological adaptation. Typically, the body's reaction to a stressor has been “flight” or “fight,” but these options are less viable in the modern environment, leading to chronic effects such as elevated adrenocortical hormone concentrations, activation of the sympathetic nervous system [42], ailments like heart disease [43], and accompanying vascular, metabolic, and inflammatory processes [43, 44]. Of itself, stress is not a health issue, and a certain amount within the coping capacity of the individual [45] is vital for a healthy life. It is the “strain,” resulting from excessive stress, outside the limitations of the stressee to cope, and resulting in anxiety and depression that can lead to allostasis and chronic disease.

Anxiety is a form of “feared helplessness” defined as “…a thin stream of fear trickling through the mind. If encouraged, it cuts a channel into which all other thoughts are drained” [46]. Anxiety occurs while an individual is striving to adapt and the association of this with ill-health is diffuse. However it is when striving ceases that depression or “learned helplessness” [47] can result, with more defined channels into a range of chronic diseases. High levels of depression have been shown to be related to a range of chronic diseases from type 2 diabetes [48] to Alzheimer's [49]. A consistent finding is a link between stress, anxiety, and depression and increased inflammatory markers, which can be associated with [50] or independent of body weight [51].

Technology-Pathology. The association of chronic disease with certain modern forms of technology is often overlooked or disregarded. This can range from death or chronic pain initiated from motor vehicle or machine injuries to auditory problems from amplified music [52]. At the extremes, it can range from mortality and morbidity from firearms and high tech weapons used in warfare to apparently obscure problems like dermatoses [53], other skin disorders [54], impaired vision [55], and repetitive strain injury from excessive computer and small screen use [56].

Other recent problems within this category are acute and chronic problems that occur while focusing on use of social media (e.g., texting and tweeting) whilst carrying out other activities, such as driving [57]. Because of its immediacy, social media bullying and intimidation can also lead to psychological morbidities and even suicide amongst prone youth, although this is not as yet well documented in the medical literature. Other problems such as “facebook depression” [58] are only beginning to emerge. Social contagion [59] effects on disease are amplified through the use of social media as shown in the association between social networks and chronic disease risks like obesity [60] and smoking [61]. Control of technology misuse is traditionally through legislative restrictions (i.e., use of cell phones while driving) but personal controls on behavior are also likely to be necessary.

Inadequate Sleep. Healthy sleep is the anchor for a healthy life, thus interacting with other chronic disease determinants discussed here [62]. Together with inactivity, inadequate sleep is one of the most underrated lifestyle risk factors for chronic disease [63]. Poor sleep is associated with an increase in inflammatory markers [64], as well as more classic risk factors [65] and significant social impacts [63]. The cumulative long-term effects of sleep deprivation and sleep disorders have been associated with a wide range of deleterious health consequences including an increased risk of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, depression, heart attack, and stroke [66]. As many as 80% of people in western countries will suffer from a sleep problem at some stage in their life, 30–50% will have difficulty in sleeping [67]. According to the US National Sleep Foundation, the average of eight to nine hours sleep per night in previous years has now dropped to around seven hours per night, with 37% of young adults getting <7 hours in 2002 compared to less than half that (16%) in 1960 [68].

Modern lifestyles are often in direct competition with sleep so much so that it could be argued that the majority of modern sleep problems have a basis in lifestyle choices. The combination of sufficient sleep with other lifestyle factors (e.g., physical activity, a healthy diet, moderate alcohol consumption, and nonsmoking) has additional value in heart disease prevention than sleep alone [69]. Sleep deprivation can also indirectly affect other disease determinants. Appetitive food mechanisms in the brain for example stimulate a greater desire for “junk” food after sleep deprivation, thus potentially enhancing obesity [70]. Unfortunately chronic disease often interferes with sleep quality and quantity generating a bidirectional vicious cycle, a situation commonly encountered in chronic disease. Inadequate sleep also has a strong relationship with elevated inflammatory markers [71]. On the positive side, sleep can be dramatically improved with a healthy approach to the lifestyle and a structured approach to sleep hygiene [72]. Simple actions like the removal of interactive media from adolescent bedrooms can be a starting point for better sleep [73].

Environment. Aspects of the environment have always been a consideration in public health. However the rise of chronic diseases has led to a more structured approach to this. Swinburn et al. [74], for example, consider four types (physical, economic, policy, and sociocultural) and two sizes (micro and macro) of “obesogenic” [75] environments, which serve to draw attention away from purely biological explanations of obesity and by extension chronic disease.

Small particle pollution from exhaust and industrial fumes [76] as well as a wide range of chemicals in the air, water, soil, and households [77] makes up the natural physical environment. A large group of such pollutants, labeled endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [78], has been attributed to significant physiological and even behavioural changes such as increased hunger, which can lead to obesity [79]. Exposure data (e.g., to bisphenol A) suggests a link between this and obesity in children [80], leading to the suggestion of some chemicals being “obesogens” [81]. Increases in carbon in the atmosphere are an example of a dramatic macroenvironmental change with potential health (as well as climate change) impacts [82]. Many environmental factors have also been shown to lead to increased metaflammation as an intermediatory process with links to chronic disease [78, 83].

Sociocultural influences are reflected, for example, in attitudes to feasting in some cultures which may have been suitable in historical times but are contraindicated with the imposition of a western culture and diets. Political environments make the “rules” that allow, for example, smoking or drinking in the family or unrestricted sales of unhealthy foods and products (e.g., cigarettes) in society. Overarching all of this is the macroeconomic system, including the modern economic growth model which demands consumption that is not necessarily conducive to health [84, 85].

Recent findings relating to the gut microbiome suggest that the inner environment (“in”-vironment in contrast to “en”-vironment) should also be considered within this category [86]. Changes in the gut microbiome not only appear to result from unhealthy activities but also influence outcomes, such as obesity through better energy harvesting through a “leaky gut” [87, 88].

Some protection against unhealthy environments may be provided by positive lifestyle changes [77, 89]. It should be obvious however that significant macroenvironmental reforms through legislative change, some of which may crossover with those required to moderate climate change [90] and other environmental degradation, are necessary.

Occupation. Meaningful work is an important component of good health. Generally however it is the direct effects on health and safety—exposure to machinery, chemicals, injury, and so forth—or the adverse health effects of work hours and shift work [91] and their effects on inflammation [92] that are considered. Recent concern has turned more to social factors. Job insecurity and job strain, for example, have been shown to increase the risk of heart disease (although the effect may be modest and largely explainable by socioeconomic factors [93]). Poor job satisfaction is linked to “burn out,” low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety [94] and excessive work hours to a risk of ill-health and damage to social relationships [95]. In work with the British Civil Service, Marmot and colleagues have reported on the health effects of perceived social justice [96], “burn out” [97], and social standing [98, 99] relating to occupational status. Changes in the nature and security of work in the modern world mean that both the physical and psychological components of occupations need to be considered part of a lifestyle/environmental perspective on health. Hence some forms of occupation can be seen as modern-day, chronic disease promoting anthropogens.

Drugs, Cigarettes, and (Excessive) Alcohol. Drugs, both licit and illicit, are responsible for a significant and increasing degree of morbidity and mortality in modern societies. The stand-out amongst licit products is cigarette smoking and its links with cancers, heart disease, and respiratory problems [100]. Legal medications form another category of drug related mortality and morbidity. Shapiro et al. [101] categorise problematic drug use into hazardous use, substance abuse, or substance dependence. Unfortunately some of the most effective medications for disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, and certain forms of epilepsy increase hunger, weight gain, and cardio-metabolic risk [102]. Illicit drug use (and the accompanying health effects) appears to increase with increased urbanization, economic prosperity, and inequality.

Its more ambiguous outcomes make alcohol a more diverse problem. Some health and social benefits of moderate consumption [103] are difficult to weigh up against the severe health and social disruption of excessive consumption, binge drinking, social and economic costs [104], and other chronic disease outcomes [100]. Overuse of alcohol is also known to have deleterious effects on several forms of disease including cancers, although this literature is not expanded on here. While excessive alcohol intake is inflammatory, moderate intake has an anti-inflammatory effect [105].

Over- and Underexposure. While many lifestyle-related behaviours have a linear association with health (e.g., smoking and sleep), others have a “U” or “tick-shaped” relationship (e.g., physical activity, alcohol, and sleep). Exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) from sunlight is a case in point. UVR is classified as a carcinogen and a major determinant for several forms of skin disorders. The incidence of melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancers, has doubled in recent years [106, 107], although this is less common than other forms of skin cancers and photoaging [108]. Intermittent extreme exposures and sunburn, as well as chronic overexposure can have differing degrees of risk [109]. Overexposure to heat and dryness (low humidity) is also thought to have adverse effects on the skin [110]. Passive smoking is yet another form of overexposure with increased risks of chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes [111].

At the other extremes, underexposure to sunlight can lead to deficiencies in vitamin D, thus increasing risks of heart disease [112], type 2 diabetes [113], and depression [114], as well as more well-known problems such as rickets [115]. Underexposure to daylight can also have unhealthy consequences in seasonal affective disorders (SAD) suffered at extreme latitudes [116].

Relationships. The quality of personal and social relationships is clearly linked to chronic disease outcomes [117] including heart disease [118], stroke [119], some cancers [120], and all-cause mortality [121].

The pathways for this are, as yet, unclear and psychological mediators have not been proven [122], but inflammatory processes have been associated with poor social relations [123] such as spousal ambivalence [124] and isolation [125] and can even stem back to maternal separation in childhood [126]. People who have supportive close relationships have lower levels of systemic inflammation compared to people who have unsatisfactory relationships [127]. Negative and competitive social interactions can even increase proinflammatory cytokine activity on a daily level [128]. In reverse, a Finnish study has shown that social support can alleviate the inflammation associated with childhood adversities [129]. Improving awareness of the importance of social support and assisting in finding such support should be integral to chronic disease management.

Social Disadvantage. Social disadvantage is associated with diseases like type 2 diabetes [130] and cardiovascular disease [131]. Disadvantage exists not only through socioeconomic status [98] and income inequalities [132] but also through economic stress and security, with metaflammation as a possible link [133].

According to the Commission on Social Determinants of Health [134], inequities in power, money, and resources are responsible for much of the inequalities in health within and between countries. While the effects of socioeconomic status on health (and inflammation) are relatively clear [135, 136], the effects of income disparities on health have been more controversial. Wilkinson and Pickett [132] in a descriptive analysis of ratios of rich to poor within and between OECD countries show a linear worsening of a number of health and social problems (obesity, infant mortality, teenage pregnancies, etc.) in countries with greater income gradients.

Much has been made of the mechanisms underlying social disadvantage, socioeconomic status, and inequality. Stringhini et al. [137] show that modifiable health behaviours and obesity could explain around 50% of the incidence in type 2 diabetes. Increases in inflammatory processes are also common with social disadvantage in different forms [138, 139] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The link between “anthropogens” obesity, metaflammation, and chronic disease. While obesity is often a correlate, this does not always imply causality in chronic disease aetiology.

4. Discussion

We have categorized a number of determinants of modern chronic diseases within a hierarchy using the acronym NASTIE ODOURS (Table 2). In doing so, we have extended the concept of lifestyle to include broader aspects of the social, political, and economic environments. Because of their man-made nature (in contrast to the microbial nature of infectious disease determinants), these have been collectively called anthropogens [19]. In addition, we have shown that most of the anthropogens discussed here have a common physiological link through chronic, systemic inflammatory (metaflammation) processes.

An obvious omission from our classification is obesity. There are two reasons for this. In the first place, obesity should be seen as a risk factor, rather than a primary determinant of disease, which is downstream, sometimes, but not always resulting from some of the determinants considered here, like overnutrition, inactivity, stress, social pressure, and so forth. A second reason is the variability of causal links between obesity and disease as exemplified in the “obesity paradox” [140] and metaflammatory associations with disease preceding or in the absence and presence of obesity [15, 17, 18]. Hence obesity is probably more a “canary in a mineshaft,” warning of problems in the broader environment than a universal cause of disease [141, 142].

There are a number of implications stemming from this discussion. Firstly, arguments about the best “diets” for weight loss and chronic disease become less relevant when looking at this big picture pattern of disease [84]. Secondly, the presence of independent upstream determinants means that weight loss should not be the sole focus of chronic disease management. Losses can be expected from changing aspects of the NASTIE ODOURS formula, but weight loss should not be seen as the sole driver of the process. Third, it would be wrong to assume that chronic disease determinants should be managed singly. The interactive nature of these determinants suggests more of a “systems” model approach to managing chronic disease problems than is often considered. Inadequate sleep and resultant fatigue, for example, can lead to a reduction in physical activity and a change in dietary patterns, uptake of technology-based entertainment, increased obesity, and resultant depression, which can continue and/or widen the cycle. The use of a “diet” for treating obesity, when underlying inflammatory processes may be related to all these more obscure determinants, is unlikely to provide optimal health. Finally a concentration on lifestyle through simply proximal and even medial determinants as defined here is unlikely to significantly influence the problem while more dominant upstream determinants remain. Effective management of modern chronic disease thus needs to be broadened to encompass a greater sphere of influence than is often publically perceived or politically popular.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Power ML, Schulkin J. The Evolution of Obesity. Baltimore, Md, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. The Lancet. 2011;377(9765):557–567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King DE, Matheson E, Chirina S, Shankar A, Broman-Fulks J. The status of baby boomers' health in the United States: the healthiest generation? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;173(5):385–386. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oschman JL. Chronic disease: are we missing something? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2011;17(4):283–285. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genuis SJ. What’s out there making us sick? Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012;2012:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/605137.605137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Have MT, van der Heide A, Mackenbach JP, de Beaufort ID. An ethical framework for the prevention of overweight and obesity: a tool for thinking through a programme's ethical aspects. European Journal of Public Health. 2013;23(2):299–305. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose G. The Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris B. Public health, nutrition, and the decline of mortality: the McKeown thesis revisited. Social History of Medicine. 2004;17(3):379–407. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson H. History and philosophy of modern epidemiology. 2011, http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/id/eprint/4159.

- 10.McKeown T. The Origins of Human Disease. New York, NY, USA: Basil Blackwell; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders JW, Fuhrer GS, Johnson MD, Riddle MS. The epidemiological transition: the current status of infectious diseases in the developed world versus the developing world. Science Progress. 2008;91(1):1–38. doi: 10.3184/003685008X284628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-α: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259(5091):87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libby P. Inflammatory mechanisms: the molecular basis of inflammation and disease. Nutrition Reviews. 2007;65(12):S140–S146. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annual Review of Immunology. 2011;29:415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egger G, Dixon J. Inflammatory effects of nutritional stimuli: further support for the need for a big picture approach to tackling obesity and chronic disease. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(2):137–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger G, Dixon J. Non-nutrient causes of low-grade, systemic inflammation: support for a “canary in the mineshaft” view of obesity in chronic disease. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(5):339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger G. In search of a “germ theory” equivalent for chronic disease. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2012;9(11):1–7. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ezzati M, Riboli E. Behavioral and dietary risk factors for non-communicable diseases. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369:954–964. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1203528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Vol. 916. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholas L, Roberts D, Pond D. The role of the general practitioner and the dietitian in patient nutrition management. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;12(1):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Chronic diseases. 2013, http://www.aihw.gov.au/chronic-diseases/

- 24.Galland L. Diet and inflammation. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2010;25:634–664. doi: 10.1177/0884533610385703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbaresko J, Koch M, Schulze MB, Nothlings U. Dietary pattern analysis and biomarkers of low-grade inflammation: a systematic literature review. Nutrition Reviews. 2013;71(8):511–527. doi: 10.1111/nure.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calder PC, Ahluwalia N, Brouns F, et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. British Journal of Nutrition. 2011;106(supplement 3):S75–S78. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511005460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Keefe JH, Gheewala NM, O'Keefe JO. Dietary strategies for improving post-prandial glucose, lipids, inflammation, and cardiovascular health. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51(3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bales CW, Kraus WE. Calorie restriction: implications for human cardiometabolic health. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2013;33(4):201–208. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e318295019e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monteiro CA. Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12(5):729–731. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cordain L. The Paleo Answer. New Jersey, NJ, USA: John Wiley and Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell TC, Campbell TM. The China Study. Dallas, Tex, USA: Bebella Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minich DM, Bland JS. Personalized lifestyle medicine: relevance for nutrition and lifestyle recommendations. The Scientifc World Journal. 2013;2013:14 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/129841.129841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollan M. In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto. New York, NY, USA: Penguin Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunstan D, Howard H, Healy GN, Owen N. Too much sitting—a health hazard. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2012;97(3):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Booth FW, Chakravarthy MV, Gordon SE, Spangenburg EE. Waging war on physical inactivity: using modern molecular ammunition against an ancient enemy. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;93(1):3–30. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00073.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenhaff PL, Hargreaves M. ‘Systems biology’ in human exercise physiology: is it something different from integrative physiology? Journal of Physiology. 2011;589(5):1031–1036. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Health and Medical Research Council. National Physical Activity Guidelines. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government Publishing Services, ACT; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinho RA, Silva LA, Pinho CA, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammatory parameters after an ironman race. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2010;20(4):306–311. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181e413df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise: its role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease control. Essays in Biochemistry. 2006;42:105–117. doi: 10.1042/bse0420105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips MD, Patrizi RM, Cheek DJ, Wooten JS, Barbee JJ, Mitchell JB. Resistance training reduces subclinical inflammation in obese, postmenopausal women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2012;44(11):2099–2110. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182644984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richard C, Couture P, Desroches S, Charest A, Lamarche B. Effect of the Mediterranean diet with and without weight loss on cardiovascular risk factors in men with the metabolic syndrome. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2011;21(9):628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lambert EA, Lambert GW. Stress and its role in sympathetic nervous system activation in hypertension and the metabolic syndrome. Current Hypertension Reports. 2011;13(3):244–248. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0186-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gémes K, Ahnve S, Janszky I. Inflammation a possible link between economical stress and coronary heart disease. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;23(2):95–103. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almadi T, Cathers I, Chow CM. Associations among work-related stress, cortisol, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(9):821–830. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The Psychology of Happiness. London, UK: Rider; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 46. http://thinkexist.com/quotation/anxiety_is_a_thin_stream_of_fear_trickling/221176.html.

- 47.Seligman ME. Helplessness: On Depression, Development and Death. San Francisco, Calif, USA: Freeman; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dixon JB, Browne JL, Lambert GW, et al. Severely obese people with diabetes experience impaired emotional well-being associated with socioeconomic disadvantage: results from diabetes MILES—Australia. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2013;101(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gracia-García P, de-la-Cámara C, Santabárbara J, et al. Depression and incident alzheimer disease: the impact of disease severity. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Inflammation as an intermediate pathway in the association between psychosocial stress and obesity. Physiology and Behavior. 2008;94(4):536–539. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamer M, Molloy GJ, de Oliveira C, Demakakos P. Persistent depressive symptomatology and inflammation: to what extent do health behaviours and weight control mediate this relationship? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23(4):413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henderson E, Testa MA, Hartnick C. Prevalence of noise-induced hearing-threshold shifts and hearing loss among US youths. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e39–e46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghasri P, Feldman SR. Frictional lichenified dermatosis from prolonged use of a computer mouse: case report and review of the literature of computer-related dermatoses. Dermatology Online Journal. 2010;16(12):p. 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wintzen M, van Zuuren EJ. Computer-related skin diseases. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48(5):241–243. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2003.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agarwal S, Goel D, Sharma A. Evaluation of the factors which contribute to the ocular complaints in computer users. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2013;7(2):331–335. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5150.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keller K, Corbett J, Nichols D. Repetitive strain injury in computer keyboard users: pathomechanics and treatment principles in individual and group intervention. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1998;11(1):9–26. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(98)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.'Connor S O, Whitehill J, King K, et al. Compulsive cell phone use and history of motor vehicle crash. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Keefe GS, Clarke-Pearson K. Council on communications and media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Paediatrics. 2011;127(4):800–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Statistics in Medicine. 2013;32(4):556–577. doi: 10.1002/sim.5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(4):370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(21):2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dement WC. The Promise of Sleep. New York, NY, USA: Delacorte Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wells ME, Vaughn BV. Poor sleep challenging the health of a Nation. The Neurodiagnostic Journal. 2012;52(3):233–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M, Akbaraly TN, et al. Associations between change in sleep duration and inflammation: findings on C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 in the Whitehall II study. The American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;178(6):956–961. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alvarez GG, Ayas NT. The impact of daily sleep duration on health: a review of the literature. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;19(2):56–59. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2004.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colten HR, Altevogt BM, editors. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Normal human sleep: an overview. In: Kyger MH, Roth TH, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 5th edition. St. Louis, Mo, USA: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 68.US National Sleep Foundation. International bedroom poll. 2013, http://now.msn.com/trenddetails?q=international+bedroom+poll.

- 69.Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Spijkerman AM, Kromhout D, Verschuren WM. Sufficient sleep duration contributes to lower cardiovascular disease risk in addition to four traditional lifestyle factors: the MORGEN study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2013 doi: 10.1177/2047487313493057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greer SM, Goldstein AN, Walker MP. The impact of sleep deprivation on the human brain. Nature Communications. 2013;2259 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Motivala SJ. Sleep and inflammation: psychoneuroimmunology in the context of cardiovascular disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;42(2):141–152. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nishinoue N, Takano T, Kaku A, et al. Effects of sleep hygiene education and behavioral therapy on sleep quality of white-collar workers: a randomized controlled trial. Industrial Health. 2012;50(2):123–131. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brunborg GS, Mentzoni RA, Molde H, et al. The relationship between media use in the bedroom, sleep habits and symptoms of insomnia. Journal of Sleep Research. 2011;20(4):569–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Preventive Medicine I. 1999;29(6):563–570. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Egger G, Swinburn B. An “ecological” approach to the obesity pandemic. British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7106):477–480. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7106.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laumbach RJ, Kipen HM. Acute effects of motor vehicle traffic-related air pollution exposures on measures of oxidative stress in human airways. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1203:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sears ME, Genuis SJ. Environmental determinants of chronic disease and medical approaches: recognition, avoidance, supportive therapy, and detoxification. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012;2012:15 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/356798.356798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dietert RR. Misregulated inflammation as an outcome of early-life exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Reviews on Environmental Health. 2012;27(2-3):117–131. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2012-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kelishai R, Poursafa P, Jamshidi F. Role of environmental chemicals in obesity: a systematic review on the current evidence. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2013;2013:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/896789.896789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eng DS, Lee JM, Gebremariam A, Meeker JD, Peterson K, Padmanabhan V. Bisphenol A and chronic disease risk factors in US children. Paediatrics. 2013;132(3):e637–e645. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Klimentidis YC, Mark Beasley T, Lin H-Y, et al. Canaries in the coal mine: a cross-species analysis of the plurality of obesity epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2011;278(1712):1626–1632. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hersoug L-G, Sjodin A, Astrup A. A proposed potential role for increasing atmospheric CO2 as a promoter of weight gain and obesity. Nutrition and Diabetes . 2012;5(2, article e31) doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bind M-A, Baccarelli A, Zanobetti A, et al. Air pollution and markers of coagulation, inflammation, and endothelial function: associations and epigene-environment interactions in an elderly cohort. Epidemiology. 2012;23(2):332–340. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824523f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Egger G. Health, “illth” and economic growth: medicine, environment and economics at the cross-roads. The American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Egger G, Swinburn B. Planet Obesity: How We Are Eating Ourselves and the Planet to Death. Sydney, Australia: Allen and Unwin; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bäckhed F. 99th dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: the normal gut microbiota in health and disease. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2010;160(1):80–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cani PD. Gut microbiota and obesity: lessons from the microbiome. Briefings in Functional Genomics. 2013;12(4):381–387. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elt014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tilg H, Kaser A. Gut microbiome, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(6):2126–2132. doi: 10.1172/JCI58109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Genuis SJ, Birkholz D, Rodushkin I, Beesoon S. Blood, urine, and sweat (BUS) study: monitoring and elimination of bioaccumulated toxic elements. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2011;61(2):344–357. doi: 10.1007/s00244-010-9611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Egger G. Dousing our inflammatory environment(s): is personal carbon trading an option for reducing obesity—and climate change? Obesity Reviews. 2008;9(5):456–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Figueiro MG, White RD. Health consequences of shift work and implications for structural design. Journal of Perinatology. 2013;33(supplement 1):S17–S23. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Puttonen S, Viitasalo K, Härmä M. Effect of shiftwork on systemic markers of inflammation. Chronobiology International. 2011;28(6):528–535. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.580869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Virtanen M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, et al. Perceived job insecurity as a risk factor for incident coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2013;347(1):p. f4746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lundberg U, Cooper CL. The Science of Occupational Health: Stress, Psychobiology and the New World of Work. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burke R, Cooper CL, editors. Long Working Hours Culture. London, UK: Emerald Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Elovainio M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Organisational justice and markers of inflammation: the Whitehall II study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010;67(2):78–83. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.044917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Toker S, Shirom A, Shapira I, Berliner S, Melamed S. The association between burnout, depression, anxiety, and inflammation biomarkers: C-reactive protein and fibrinogen in men and women. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;10(4):344–362. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wilkinson RG, Marmot MG. Social Determinants of Health. 2nd edition. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Marmot MG. Status Syndrome: How Your Social Standing Directly Affects Your Health and Life Expectancy. London, UK: Bloomsbury Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rehm J, Taylor B, Room R. Global burden of disease from alcohol, illicit drugs and tobacco. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25(6):503–513. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shapiro B, Coff D, McCance-Katz EF. A primary care approach to substance misuse. The American Family Physician. 2013;88(2):113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hasnain M, Vieweg WV, Hollett B. Weight gain and glucose dysregulation with second-generation antipsychotics and antidepressants: a review for primary care physicians. Postgraduate Medicine. 2012;124(4):154–167. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2012.07.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Poli A, Marangoni F, Avogaro A, et al. Moderate alcohol use and health: a consensus document. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2013;23(6):487–4504. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Huang D, Hunter Z, Francescutti LH. Alcohol, health, and injuries. The American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2013;7(4):232–240. [Google Scholar]

- 105.O'Keefe JH, Bybee KA, Lavie CJ. Alcohol and cardiovascular health. The razor-sharp double-edged sword. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50(11):1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Garibyan L, Fisher DE. How sunlight causes melanoma. Current Oncology Reports. 2010;12(5):319–326. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0119-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tuong W, Cheng LS, Armstrong AW. Melanoma: epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Dermatologic Clinics. 2012;30(1):113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morganroth PA, Lim HW, Burnett CT. Ultra-violet radiation and the skin: an in-depth review. The American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2013;7(3):168–181. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Alexander RL. Skin cancer: causes and groups at risk. Nursing Times. 2012;108(30-31):23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Egger G, Molloy H. Skin Fitness. Sydney, Australia: Allen and Unwin; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang Y, Ji J, Liu YJ, Deng X, He QQ. Passive smoking and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069915.e69915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zittermann A, Koerfer R. Vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2008;11(6):752–757. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328312c33f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mezza T, Muscogiuri G, Sorice GP. Vitamin D deficiency: a new risk factor for type 2 diabetes? Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2012;61(4):337–348. doi: 10.1159/000342771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;202:100–107. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Caruso TJ, Fuzaylov G. Severe vitamin D deficiency—rickets. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369, article 9 doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1205540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Oren DA, Koziorowski M, Desan PH. SAD and the not-so-single photoreceptors. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1403–1412. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13010111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology. 2010;36:139–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72(3):229–238. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stuller KA, Jarrett B, DeVries AC. Stress and social isolation increase vulnerability to stroke. Experimental Neurology. 2012;233(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2010;75(2):122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton B. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316.e1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Uchino BN, Bowen K, Carlisle M, Birmingham W. Psychological pathways linking social support to health outcomes: a visit with the “ghosts” of research past, present, and future. Social Science and Medicine. 2012;74(7):949–957. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin J-P, Hantsoo L. Close relationships, inflammation, and health. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Uchino BN, Bosch JA, Smith TW, et al. Relationships and cardiovascular risk: perceived spousal ambivalence in specific relationship contexts and its links to inflammation. Health Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0033515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yang YC, McClintock MK, Kozloski M, Li T. Social isolation and adult mortality: the role of chronic inflammation and sex differences. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54(2):183–203. doi: 10.1177/0022146513485244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lacey RE, Kumari M, McMunn A. Parental separation in childhood and adult inflammation: the importance of material and psychosocial pathways. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fagundes CP, Bennett JM, Derry HM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Relationships and inflammation across the lifespan: social developmental pathways to disease. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(11):891–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chiang JJ, Eisenberger NI, Seeman TE, Taylor SE. Negative and competitive social interactions are related to heightened proinflammatory cytokine activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(6):1878–1882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120972109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Runsten S, Korkeila K, Koskenvuo M, Rautava P, Vainio O, Korkeila J. Can social support alleviate inflammation associated with childhood adversities? Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;68(2):137–144. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.786133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Stringhini S, Batty GD, Bovet P, et al. Association of lifecourse socioeconomic status with chronic inflammation and Type 2 diabetes risk: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001479.e1001479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Clark C, Ridker P, Ommerborn M, et al. Cardiovascular inflammation in healthy women: multilevel associations with state-level prosperity, productivity and income inequality. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1, article 211) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wilkinson RG, Pickett K. The Spirit Level. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Petersen KL, Marsland AL, Flory E Votruba-Drzal J, Muldoon MF, Manuck SB. Community socioeconomic status is associated with circulating interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(6):646–652. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817b8ee4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.CDSH. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gallo LC, Fortmann AL, de los Monteros KE, et al. Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and inflammation in Mexican American women: what is the role of obesity? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74(5):535–542. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824f5f6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ramsay S, Lowe GDO, Whincup PH, Rumley A, Morris RW, Wannamethee SG. Relationships of inflammatory and haemostatic markers with social class: results from a population-based study of older men. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197(2):654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Stringhini S, Tabak AG, Akbaraly TN, et al. Contribution of modifiable risk factors to social inequalities in type 2 diabetes: prospective Whitehall II cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5452.e5452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Friedman EM, Herd P. Income, education, and inflammation: differential associations in a national probability sample (The MIDUS Study) Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72(3):290–300. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cfe4c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Marmot MG, Shipley MJ, Hemingway H, Head J, Brunner EJ. Biological and behavioural explanations of social inequalities in coronary heart disease: the Whitehall II study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(11):1980–1988. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1144-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Flegal KM, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Perspective: mortality and survival. Obesity. 2013 doi: 10.1002/oby.20588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Egger GJ, Dixon JB. Obesity and global warming: are they similar “canaries” in the same “mineshaft”? Medical Journal of Australia. 2010;193(11-12):635–637. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pagoto SL, Appelhans BM. A call to the end of the diet debate. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310:687–688. [Google Scholar]