Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major clinical challenge mostly due to cigarette smoke (CS) exposure. Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are potent immunoregulatory cells that have a crucial role in inflammation. In the current study, we investigate the role of iNKT cells in COPD pathogenesis. The frequency of activated NKT cells was found to be increased in peripheral blood of COPD patients relative to controls. In mice chronically exposed to CS, activated iNKT cells accumulated in the lungs and strongly contributed to the pathogenesis. The detrimental role of iNKT cells was confirmed in an acute model of oxidative stress, an effect that depended on interleukin (IL)-17. CS extracts directly activated mouse and human dendritic cells (DC) and airway epithelial cells (AECs) to trigger interferonγ and/or IL-17 production by iNKT cells, an effect ablated by the anti-oxidant N-acetylcystein. In mice, this treatment abrogates iNKT-cell accumulation in the lung and abolished the development of COPD. Together, activation of iNKT cells by oxidative stress in DC and AECs participates in the development of experimental COPD, a finding that might be exploited at a therapeutic level.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by not reversible airflow limitation.1 This disease affects more than 200 million people and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.2 Cigarette smoke (CS) exposure is the most important risk factor for COPD.3

Exposure to CS induces a strong burden of reactive oxygen species in the lung leading to imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants.4 An important part of this oxidative stress is related to lipid peroxidation, a phenomenon that can be mimicked by administration of cumen hydroperoxide (CHP).5 CS-induced oxidative stress is involved in COPD development through its role in airway inflammation. Long-term exposure to CS leads to the recruitment of macrophages, neutrophils and CD8+ T cells,6 which amplify the oxidative stress in the lungs.7 Previous findings have provided evidences that cells of the innate immune system, including NK cells, are sufficient to induce inflammation and emphysema after chronic CS exposure.8 Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells comprise a subset of lymphocytes that express features of classical NK and T cells, including restricted TCR consisting of an invariant VαJα-chain (Vα24-Jα18 in humans and Vα14-Jα18 in mice) combined with a more polyclonal Vβ-chain (Vb11 in humans, Vb8.2, 7, and 2 in mice). iNKT cells recognize (glyco)lipid Ag presented by the non polymorphic MHC class I-like protein, CD1d, widely expressed by macrophages, dendritic cells (DC), airway epithelial cells (AECs) and B cells.9 Recognition of CD1d-presented lipids by iNKT cells is highly conserved among different mammalian species, suggesting that iNKT cells have a pivotal role in immunity.9, 10 Activation of iNKT cells results in an innate-like immune response characterized by an important production of cytokines (interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-4, and IL-17),9, 11 and cytotoxic proteins (granzyme B and perforin).12, 13 This rapid response endows iNKT cells with the capacity to critically amplify innate and adaptive immunity. Several studies have defined the impact of iNKT-cell activation on the development of diseases, including infectious diseases and asthma.14, 15, 16

Others and we have shown that iNKT are involved in the control of airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in mice, in models of allergic reaction,17, 18 and after exposure to oxidant pollutants such as ozone.19 Kim et al.20 also showed that iNKT cells are implicated in an experimental model of chronic lung disease induced by Sendai virus infection, with pathology that resembles asthma and COPD. Of interest is the recent observation that patients developing COPD have an increased number of iNKT cells in the blood and the lungs.20, 21, 22, 23 In the current study, we investigated the potential role of iNKT cells in a model of chronic exposure to CS mimicking COPD symptoms, and in an acute model of lipid peroxidation using CHP as the trigger. We demonstrated that exposure of mice to CS and to CHP-induced changes in lung functions that requires the presence of iNKT cells. These effects were dependant on oxidative stress as addition of the anti-oxidant N-acetylcystein (NAC) prevents the activation of iNKT cells and the deleterious effects of CS. We showed that CS-induced oxidative stress in AEC and DC was responsible for iNKT-cell activation both in humans and mice. Targeting iNKT cells may represent an effective therapeutic approach to control COPD in humans.

Results

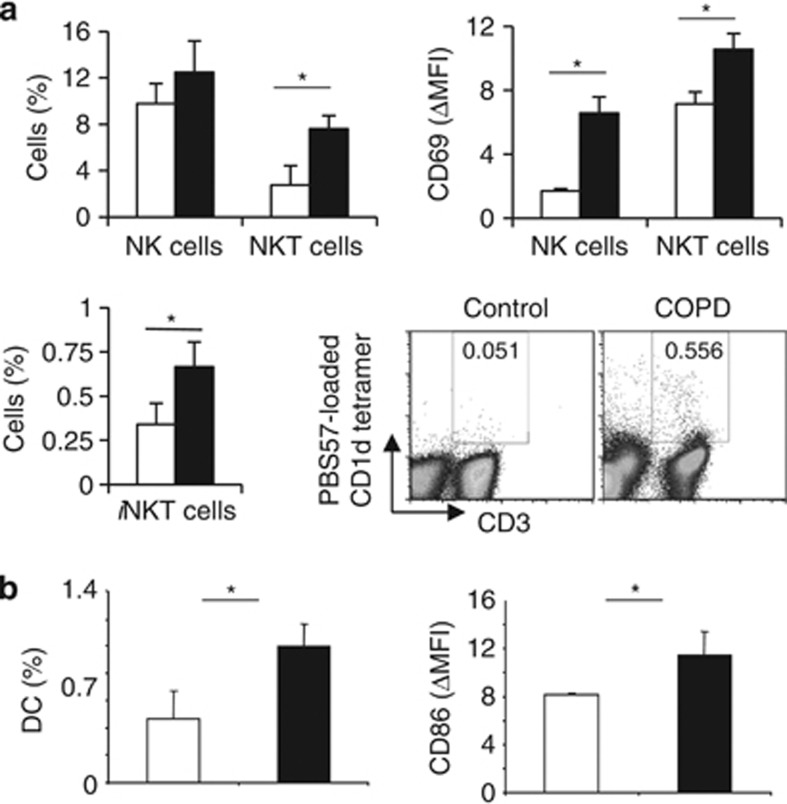

Activated NKT cells in peripheral blood of COPD patients

We first aimed to determine the frequency of (i)NKT cells in COPD patients (Supplementary Table 2 online). Compared with healthy controls, proportions of CD56+ CD3+ NKT cells, and to a lesser extent CD56+ CD3− NK cells, were enhanced in COPD patients. This was associated with an enhanced expression of the activating marker CD69. Compared with healthy donors, COPD patients also exhibited a higher frequency of iNKT cells, identified as CD3+ PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer+ cells (Figure 1a). Increased percentages of circulating DC, and higher expression of CD86 on DC were observed in COPD patients (Figure 1b). Pulmonary inflammation was confirmed by higher levels of CXCL-8 and TNF-α in their sputum, and increased production of IL-22 and IFN-γ by PBMC (Supplementary Figure 2 online). These data suggest that (i)NKT cells could be involved in COPD pathology.

Figure 1.

Characterization of immune cells in human fluids of control donors and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. (a) Percentages of CD3− CD56+ natural killer (NK), CD3+ CD56+ NKT-like and CD3+ PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer+ iNKT cells, and CD11c+ HLA-DR+ myeloid dendritic cell (DC) were evaluated in the peripheral blood of seven healthy controls (white bars) and 28 COPD patients (black bars). The ΔMFI of the activation markers CD69 relative to isotype controls was analyzed on NK, and NKT-like cells. (b) Percentages of CD11c+ HLA-DR+ myeloid DC were evaluated in blood of healthy controls (white bars) and COPD patients (black bars). The ΔMFI of the activation markers CD86 relative to isotype controls was analyzed on DC. Gates were respectively drawn according to isotype controls, or unloaded CD1d tetramer. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05.

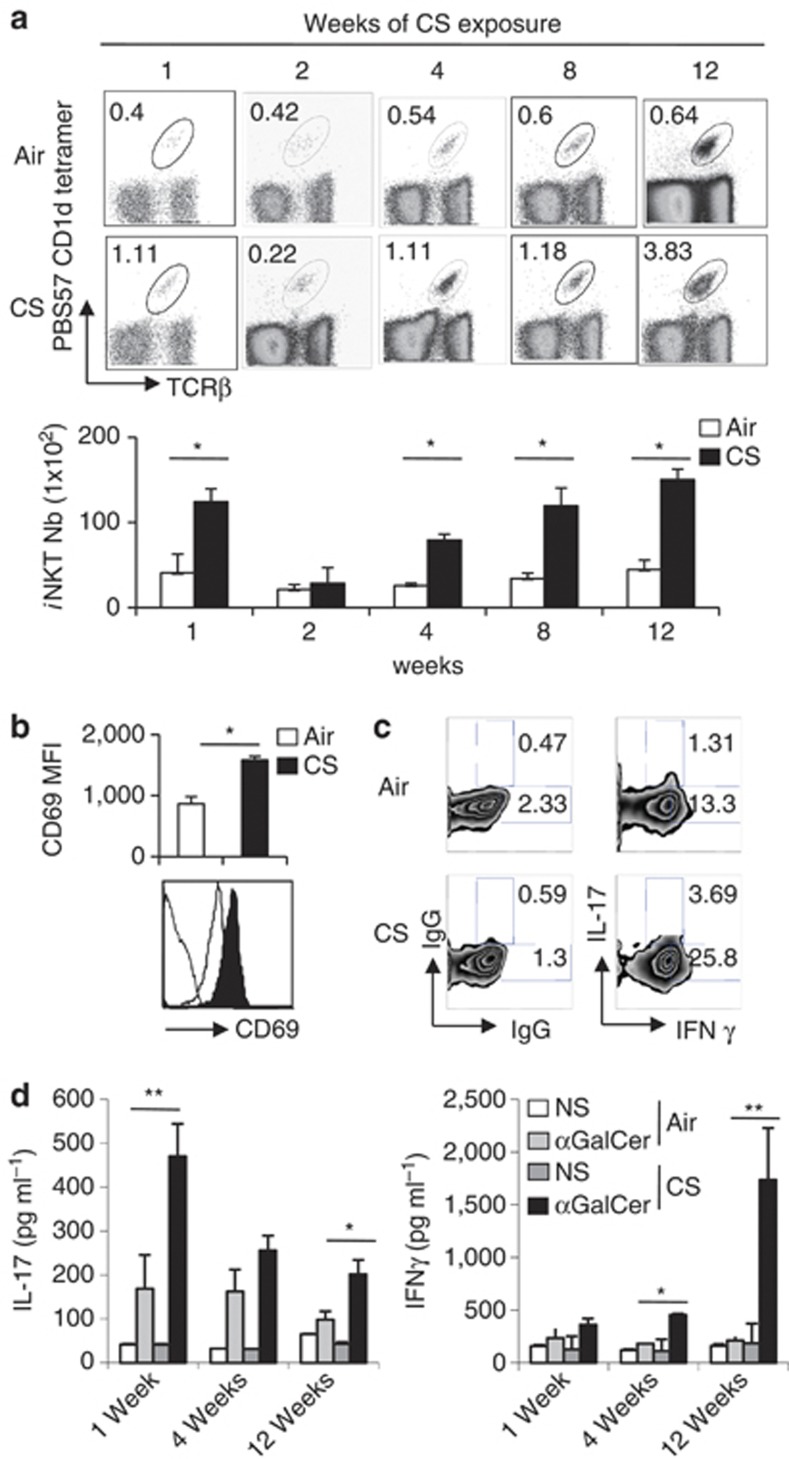

CS exposure triggers the accumulation and the activation of iNKT cells in the lungs

Repeated exposure of C57BL/6 mice to CS induced an inflammatory lung reaction, mimicking COPD, as previously described.8 This was characterized by neutrophil, NK cell and macrophage recruitment (+30–50%) and/or activation after chronic exposure to CS, compared with mice exposed to ambient air (Figure 3c, Figure 5a). The frequency and number of pulmonary iNKT cells was enhanced after CS exposure (Figure 2a); these parameters then returned to basal levels at week 2 post-exposure to again increase at weeks 4, 8, and 12. An increased expression of the activation marker CD69 on iNKT cells persisted all along the experiment (Figure 2b and not shown). Analysis of CD5+ NK1.1+ cells confirmed these data (Supplementary Figure 3A and B, and not shown). In contrast, the proportion, the number, and the activation status of iNKT cells remained unchanged in the spleen of CS-exposed mice (Supplementary Figure 3C-E). PMA/ionomycin stimulation of lung cells resulted in a higher frequency of IL-17+ and IFN-γ+ iNKT cells at 1 week post CS exposure (Figure 2c) and later (not shown). Stimulation of pulmonary cells from CS-exposed mice with the prototypical iNKT-cell activator αGalCer resulted in a higher production of IL-17 at 1 and 12 weeks post-CS exposure. In contrast, a significant enhancement of IFN-γ production was observed only at 12 weeks post-exposure (Figure 2d). No difference in IL-4 levels was observed (not shown). Collectively, CS exposure leads to an increased recruitment or a local expansion of activated iNKT cells in the lungs.

Figure 2.

Cigarette smoke (CS) exposure enhances the number of pulmonary invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells and triggers their activation. (a) Mice were exposed to CS 5 days a week for a period of 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. The frequency (upper panel) and number (lower panel) of iNKT cells (CD45+ TCRβ+ PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer+ cells) in lung tissues were determined. Data are representative of one experiment out of three time courses performed (mean±s.e.m.). (b) Mice were killed after 12 weeks of CS exposure and the expression level of CD69 on lung iNKT cells was determined. (c) Lung mononuclear cells from mice exposed to CS for 1 week were restimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 3 h. Gated iNKT cells were analyzed for intra-cellular interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-17 production. Gates were set based on the relative isotype control. Representative dot plots are shown (n=3). (d) Lung cells from mice exposed to CS for 1, 4, or 12 weeks were treated with αGalCer (100 ng ml−1) or not (NS, non stimulated) for 48 h. The concentrations of IL-17 and IFN-γ were analyzed by ELISA in the supernatants. Values represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=5). *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

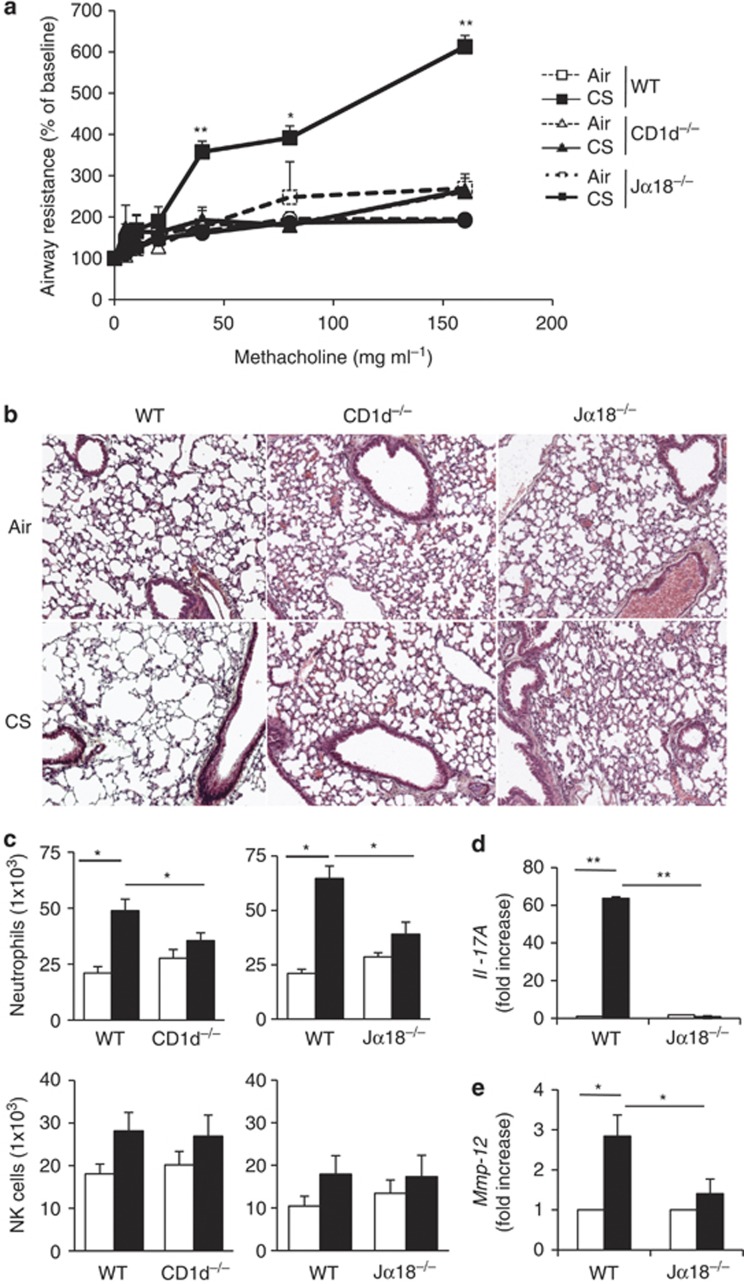

iNKT cells are required in CS-induced airway inflammation and lung alterations

Exposure of WT mice to CS resulted in a severe increase in lung resistance (Figure 3a). Remarkably, both CS-exposed Cd1d−/− mice, which lack iNKT and variant NKT cells, as well as Jα18−/− mice, which are only devoid of iNKT cells, showed no changes in their lung resistance (Figure 3a), dynamic compliance and airway elastance (Supplementary Figure 4A). CS exposure induced a significant weight loss (∼15%) in WT mice, but not in (i)NKT cell-deficient mice (Supplementary Figure 4B). Histological analysis revealed a decreased pathology in (i)NKT cell-deficient animals (Figure 3b). WT mice exposed to CS, but not Cd1d−/− and Jα18−/− mice, had enlarged alveolar spaces (emphysema) and airway remodeling associated to a mild inflammatory infiltrate. Measurements of airspace cord length were also performed to evaluate lung injuries. This was significantly increased in CS-exposed WT mice (49.7 μm±2.1 compared with 32.1 μm±1.1 in air-exposed mice, P<0.001), but not in CS-exposed Jα18−/− mice (40.6 μm±1.7). There is no statistical difference in airspace cord length between air- and CS-exposed Cd1d−/− as well as Jα18−/− mice (P=NS). CS exposure resulted in the infiltration of neutrophils and NK cells in the BAL (not shown) and in the lungs of WT mice (Figure 3c), as previously described.24 No significant recruitment of neutrophils and NK cells was observed after CS exposure in Cd1d−/− and Jα18−/− mice (Figure 3c and not shown). CS exposure induced higher levels of Il-17 and Il-1b mRNA, but this increased expression was not observed in Jα18−/− mice (Figure 3d and Supplementary Figure 4C). Pulmonary Ifn-g expression was not modulated in NKT-deficient mice exposed to CS (not shown). mRNA levels of Mmp12, a key mediator in smoke induced emphysema,25 were markedly induced by CS exposure in WT animals, but not in Jα18−/− mice (Figure 3e). Altogether, this indicated that CS-induced alterations of lung function, inflammation, and emphysema strongly relied on iNKT cells.

Figure 3.

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are essential to promote chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) features in mice. (a) Analysis of lung function decline induced by cigarette smoke (CS) in iNKT-cell-deficient mice. Age-matched wild-type (WT), Jα18−/−, and CD1d−/−mice were exposed to CS, 5 days a week, over a period of 12 weeks. Changes in airway resistance were measured on anesthetized, tracheotomized, intubated, and mechanically ventilated mice, in response to increasing doses of methacholine. Results are expressed as the mean±the s.e.m. Results are representative of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (WT mice vs. iNKT-cell-deficient mice). (b) Histological analysis of lung sections from mice exposed to CS. Lungs were harvested 12 weeks post-air or CS exposure and histopathological analysis was performed on lung sections. Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections (original magnification × 200) are shown. Note that CS exposure induced lung infiltration and destruction of alveolar walls in WT mice, whereas lung structure was not changed in (i)NKT-cell-deficient mice. (c) Absolute numbers of CD45+ CD11c− F4/80− CD11b+ Ly6C+ neutrophils and CD45+ TCRβ− NK1.1+ NK cells were analyzed among lung mononuclear cells of mice exposed to CS for 12 weeks. Values represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=5). (d, e) The lungs were collected 12 weeks post-exposure, interleukin (IL)-17 (d) and Mmp12 (e) mRNA copy numbers were determined by quantitative RT–PCR. Data are normalized to expression of Gapdh and are expressed as fold increased over average gene expression in air-exposed WT mice or Jα18−/− mice, respectively (n=5). *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

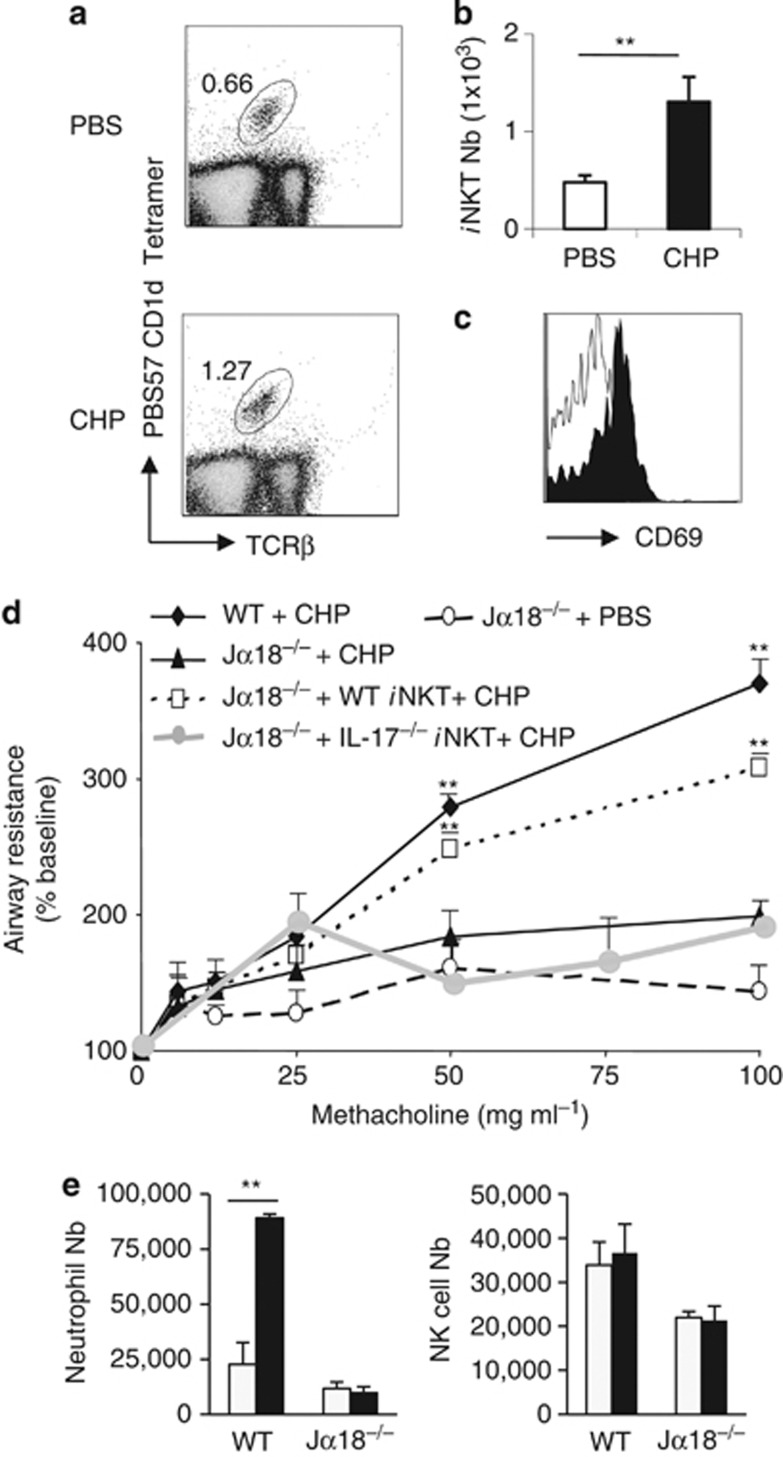

iNKT cells mediate lung damage induced by acute exposure to CHP

To confirm the role of iNKT cells in lung damage induced by oxidant stress, we developed a more acute model based on CHP treatment, a compound that specifically triggers lipid peroxidation.5 Exposure to CHP led to an enhanced frequency and number of pulmonary iNKT cells (Figure 4a and b). CD69 expression was increased on iNKT cells (Figure 4c). Exposure to CHP increased airway resistance (Figure 4d), and neutrophil recruitment into the lungs (Figure 4e). No changes in NK cells were observed (Figure 4e). In sharp contrast, CHP-treated Jα18−/− mice displayed no change in their lung functions, and airway inflammation (Figure 4d and e). Adoptive transfer of WT iNKT cells into Jα18−/− mice before CHP exposure resulted in a significant enhancement of airway resistance reaching levels observed in CHP-exposed WT animals, whereas negative fraction depleted in iNKT cells (data not shown) and Il-17−/− iNKT cells failed to do so (Figure 4d). Thus, IL-17 expressing iNKT cells have a pivotal role in CHP-associated alterations of lung function.

Figure 4.

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells have a deleterious function in lung alteration induced by acute exposure to CHP. (a and b) Wild-type (WT) mice were intranasally exposed three times to cumen hydroperoxide (CHP; 75μg per mouse), and 24 h after the last challenge, lung tissues were harvested and processed. The frequency (a) and number (b) of iNKT cells in lung tissues were determined. Data are representative of one experiment out of three performed (mean±s.e.m., n=4), **P<0.01. (c) Expression of CD69 by lung iNKT cells after CHP exposure. (d) Age-matched WT or Jα18−/− mice, either reconstituted or not with WT or Il-17−/− iNKT cells (1 × 106 WT iNKT cells per mouse, i.v. injection) were exposed to CHP. Twenty-four hours after the last challenge, changes in airway resistance were measured in response to increasing doses of methacholine. Results are expressed as the mean±the s.e.m. (n=4) and are representative of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (e) Absolute numbers of CD45+ CD11c− F4/80− CD11b+ Ly6C+ neutrophils and CD45+ TCRβ− NK1.1+. NK cells were analyzed among lung mononuclear cells of mice exposed to CHP. Values represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=4), **P<0.01.

CSE-stressed APC stimulate iNKT cells

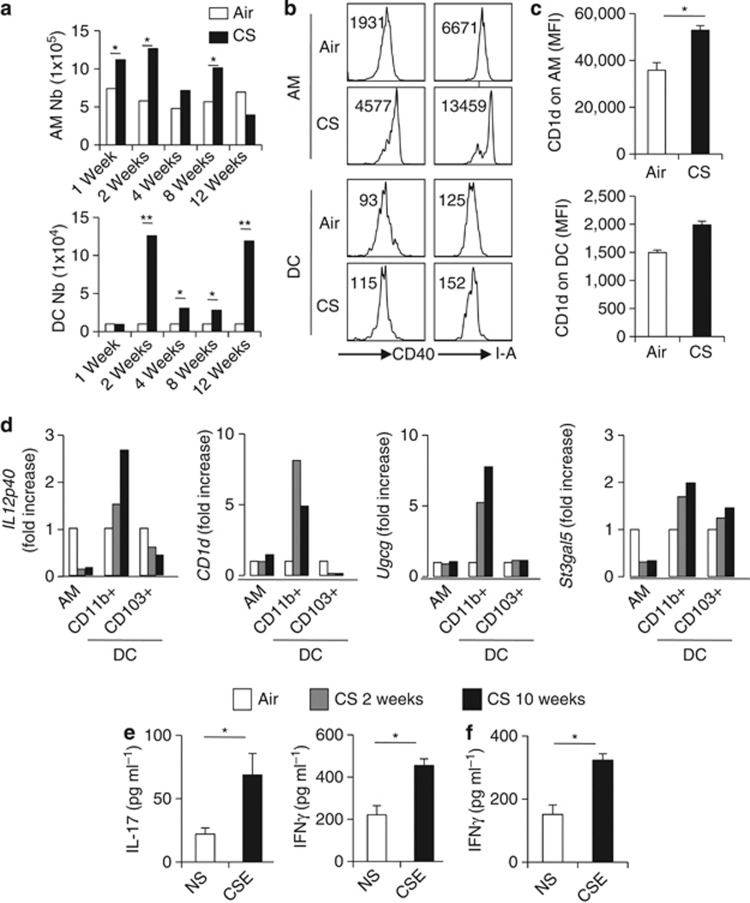

DC and macrophages have a key role in iNKT-cell activation.10, 14 CS exposure induced a pulmonary inflammation, depicted by an increased number of total lung cells (Supplementary Figure 5A), which peaked at 2 weeks post-treatment and slowly decreased. Although the number of alveolar macrophages (AM) shows the same pattern, the number of respiratory DC was enhanced from 2 to 12 weeks post exposure (Figure 5a). CS induced an upregulation of CD40 and MHC class II (I-A) on AM and DC, a phenomenon also observed in Jα18−/− mice (Figure 5b and Supplementary Figure 5C). CD1d expression was enhanced on AM and DC, although not significantly for the latter (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Respiratory antigen presenting cells (APCs) isolated from cigarette smoke (CS)-exposed mice activate invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells. (a) Twelve weeks after CS exposure, the number of alveolar macrophages (AM) (CD45+ CD11c+ F4/80+) and dendritic cell (DC; CD45+ CD11c+ F4/80−) in the lung compartment were determined. Data are representative of one experiment out of three performed (mean±s.e.m., n=6). (b) Activation status of lung DC and AM. Representative histograms of CD40 and I–A on AM and DC are shown. MFI are represented on the dot plots. (c) Expression of CD1d on AM and DC. Data are representative of one experiment out of three performed (mean±s.e.m., n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (d) Pulmonary AM, CD11b+ DC, and CD103+ DC were sorted from air- or CS-exposed mice (2 or 10weeks post-treatment), RNA samples were prepared and IL-12p40, CD1d, glucosylceramide synthase Ugcg, and GM3 synthase St3gal5 mRNA expression were measured by quantitative RT–PCR. Data are normalized to expression of Gapdh and are expressed as fold increased over average gene expression in air-exposed mice. Each group is a pool of cells from 10 mice and is representative of three independent experiments. (e) Bone marrow-dendritic cells (BM-DC) were differenciated and exposed or not to CSE overnight before coculture with sorted iNKT cells. Interleukin (IL)-17 and interferon (IFN)-γ levels were measured by ELISA in the coculture supernatants 48 h later. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05.

To investigate the potential ability of AM and DC to trigger iNKT-cell activation, we sorted AM and the two predominant lung DC subsets, namely CD11b+ CD103− DC (referred to as CD11b+) and CD11b− CD103+ DC (here referred to as CD103+) (Supplementary Figure 1) at 2 and 10 weeks post CS exposure. Of interest, cell-sorted CD11b+ DC, but not CD103+ DC, nor AM, expressed higher levels of Il-12p40 and Cd1d transcripts (Figure 5d), two crucial factors for iNKT-cell activation.14 The expression of Il-23p19 was unchanged in these cells (not shown), whereas it was increased in the total lungs (Supplementary Figure 6A). The transcript level of Ugcg and to a lesser extend St3gal5, both enzymes initiating biosynthesis of glycolipids activators of iNKT cells,26 was enhanced in CD11b+ DC, but not in CD103+ DC or AM (Figure 5d). St3gal5 expression was increased in the lungs of CS-exposed animals (Supplementary Figure 6B).

To assess the possibility that CS directly drives DC to stimulate iNKT cells, BM-DC were exposed to CS extracts (CSE) in vitro and next cocultured with sorted primary iNKT cells. Compared with unstimulated BM-DC, CSE-treated BM-DC triggered IL-17 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells (Figure 5e) although at a lower level compared with α-GalCer (data not shown). Among structural pulmonary cells, AEC are numerous and are directly in contact with aero-pollutants. We therefore investigated the possibility that AEC might be important in iNKT-cell activation. Primary mouse AEC exposed to α-GalCer induced in a CD1d-dependant manner the production of IL-2 by DN32 iNKT hybridoma and mainly IL-4 by sorted splenic iNKT cells (Supplementary Figure 7). In addition, mouse AEC exposed to CSE had the potential to induce IFN-γ, but not IL-17, production by iNKT cells (Figure 5f and not shown). These data showed that CS exposure in mice primed DC and AEC, to activate iNKT cells.

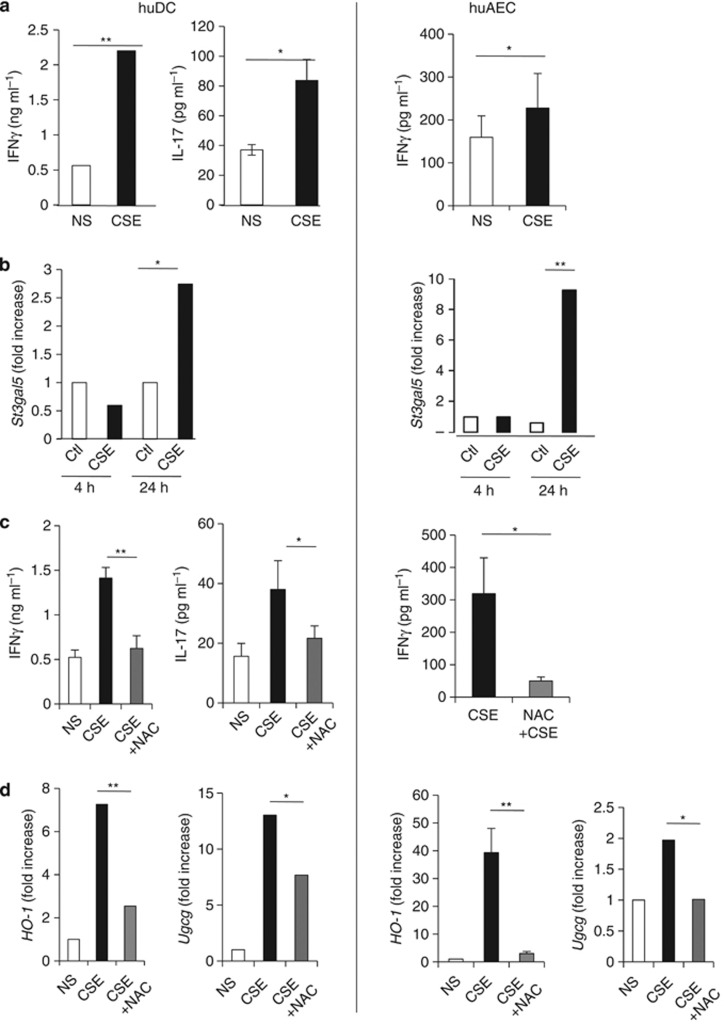

Human CSE-stressed DC and AEC stimulate iNKT cells

We next aimed to validate these results using human cells. Both DC and AEC were exposed to CS and cocultured with iNKT-cell lines. CSE-treated DC induced IFN-γ and IL-17 release by iNKT cells (Figure 6a right). In contrast, CSE-treated AEC only induced IFN-γ production (Figure 6a left).

Figure 6.

Human invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are activated by cigarette smoke (CS)-exposed human dendritic cell (huDC) and human airway epithelial cell (huAEC). (a) Human monocyte-derived DC (left column) or lung epithelial cells (right column) were exposed, or not, to CSE for 24 h. After washes, cells were cocultured with primary CD3+ 6B11+ iNKT cells. Interleukin (IL)-17 and interferon (IFN)-γ were measured by ELISA. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (b) DC and AEC were collected 4 and 24 h after CSE exposure, RNA extracts were prepared, and St3gal5 synthase mRNA copy numbers were measured by quantitative RT–PCR. Data are normalized to expression of β-actin and are expressed as fold increased over average gene expression in air-exposed cells. (c) DC and AEC were pretreated with NAC (0.5 mM) for 1 h prior CSE exposure for 24 h. After washes, cells were cocultured with primary iNKT cells. IL-17 and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (d) DC and AEC were treated with NAC for 1 h, and then exposed to CSE for 24 h. RNA extracts were prepared, and HO-1 and Ugcg mRNA copy numbers were measured by quantitative RT–PCR. Data are normalized to expression of β-actin and are expressed as fold increased over average gene expression in air-exposed cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Exposure to CSE enhanced mRNA expression of UGCG and ST3GAL5, and of the oxidation markers, NADPH deshydrogenase Quinone-1 (NQO-1) and heme-Oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (Figure 6b and Supplementary Figure 8) with a different time course in both DC and AEC. To test the implication of oxidative stress in iNKT-cell activation, APC were pretreated with the anti-oxidant NAC. NAC-pretreatment of CSE-exposed DC and AEC strongly diminished iNKT-cell activation (Figure 6c). This was associated with a strong decrease in levels of HO-1 and UGCG in APC (Figure 6d and Supplementary Figure 8). These data show that human DC and AEC exposed to CS-induced oxidative stress trigger iNKT-cell activation.

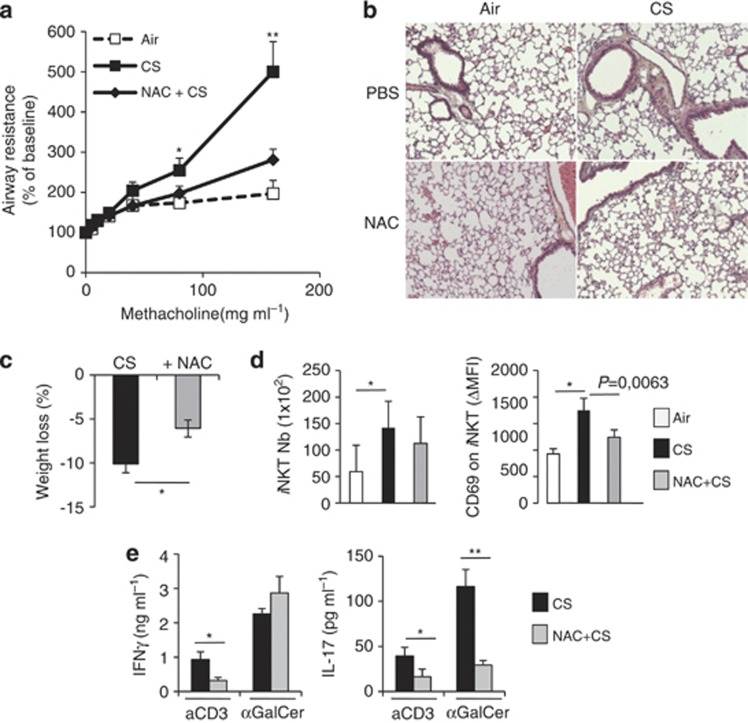

NAC prevents CS-induced decline in lung functions and iNKT-cell activation

To establish a link between oxidative stress, iNKT-cell activation and decreased lung functions, mice were treated with NAC during the course of chronic CS exposure. NAC treatment limited the alteration of lung function (Figure 7a and Supplementary Figure 8). CS-exposed animals treated with NAC displayed less airway remodeling, as depicted by a reduced alveolar enlargement (Figure 7b). NAC treatment significantly reduced the airspace cord length (from 49.7 μm±2.1 in CS-exposed mice to 37.2 μm±1.2 in CS-exposed NAC-treated mice, P<0.001). This was associated with a reduced expression of Mmp12 in the lung (data not shown). Administration of NAC reduced the weight loss due to CS exposure (Figure 7c). NAC treatment also prevented the accumulation and the increased expression of CD69 on pulmonary iNKT cells (Figure 7d). In response to αGalCer, the level of IL-17 in supernatants from lung cells was reduced by 75% in the CS-exposed group receiving NAC, whereas no changes were observed for IFN−γ and IL-4 (Figure 7e). Of note, upon CD3 Ab restimulation, NAC decreased both IFN-γ and IL-17 release in lung cells (Figure 7e). These data showed that the anti-oxidant NAC prevents the mobilization and the activation of iNKT cells in CS-exposed mice, an effect that is associated with improved lung function and decreased pathogenesis.

Figure 7.

N-acetylcystein (NAC) prevents the recruitment/activation of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells and reduced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) features induced by cigarette smoke (CS) exposure. Wild-type (WT) mice treated or not with NAC in the drinking water were exposed to CS and compared with air mice. (a) Changes in airway resistance were measured after 12 weeks in response to increasing doses of methacholine. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (b) Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections (original magnification × 200) are shown. (c) Weight loss percentages of CS- and NAC+CS-exposed mice compared with air mice are shown. *P<0.05. (d) The number of iNKT cells and the expression of CD69 on iNKT cells are depicted. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05. (e) Lung-cell suspensions from mice exposed to CS, with or without NAC treatment, were cultured for 48 h in presence of anti-CD3 Abs or α-GalCer. Cytokine levels were analyzed in supernatants by ELISA. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Discussion

Oxidative stress induced by CS is part of the mainstay of COPD physiopathology. This study for the first time demonstrates that iNKT cells are detrimental in experimental COPD, a phenomenon that can be reversed by abrogating oxidative stress in vivo. We also report that lung damage induced by acute exposure to CHP, another oxidative stress inducer, is dependent on iNKT cells. Finally, we report that DC and AEC are important sensors of oxidative stress mediated by CS and that downstream pathways triggered in these cells lead to iNKT-cell activation.

CS contains a myriad of oxidant compounds inducing the production of deleterious reactive oxygen species causing airway inflammation and loss of lung functions.7, 27, 28 Our COPD model showed an accumulation of iNKT cells in the lungs as early as 1 week post CS exposure. These data are in line with recent studies showing the presence of iNKT cells in the BAL and induced sputum of COPD patients and in blood as shown in the present study.20, 21, 22, 23 In contrast, Chi et al.29 and Vijayanand et al.30 showed that the frequencies of peripheral blood and alveolar CD3+ 6B11+ iNKT cells are significantly lower in patients with stable COPD, a finding that might be explained by the less stringent method used to identify NKT cells.29, 30 The present study highlight the need for a more complete assessment of the innate immune response. To establish a role for NKT cells in COPD, we analyzed NKT cells in the mouse model in combination with human patients. As reported here, iNKT cells displayed an activated phenotype (CD69), both in the blood of COPD patients and during the course of chronic exposure to CS in mice. Furthermore, whenever the time point, iNKT cells from CS-exposed mice produced enhanced levels of cytokines (mainly IL-17) upon stimulation. These results collectively indicate that iNKT cells are recruited, or locally expand, in the lungs and express an activated phenotype (Th17 bias) early during COPD.

The potential role of iNKT cells in COPD was next investigated. The absence of iNKT cells (Cd1d−/− and Jα18−/− mice) abolished most of the features of COPD pathogenesis. The absence of iNKT cells reduced IL-17 production and neutrophil recruitment, the latter being important in the physiopathology of COPD.31, 32 In parallel, iNKT-cell-deficient animals were protected against lung damage caused by acute CHP exposure, a phenotype restored by adoptive transfer of IL-17 competent iNKT cells. As the lack of iNKT cells only reduced IL-17 in the lungs of COPD mice and neutralizing anti-IL-17 antibodies inhibit the development of COPD,32 iNKT-cell-derived IL-17, rather than IFN-γ, might be instrumental in experimental COPD. We hypothesize that iNKT-cell-derived IL-17 may participate in the recruitment of neutrophils and in the generation of deleterious proteases, including MMP12. Moreover, iNKT cells act as upstream activators of NK cells, other innate cells recently described to have part in COPD.33 Pulmonary NKT cells have also an essential role in mediating hypoxic acute lung injury.34 Our previous findings have revealed the deleterious role of iNKT cells in lung functions after ozone exposure, another oxidant,19 a phenomenon due to Th2-type cytokine production, whereas during COPD (and after CHP treatment, not shown) iNKT cells produced IFN-γ and IL-17. We postulate that, according to the type of oxidative stress, different subpopulations and/or pathways can be selected and/or induced in iNKT cells to impair lung functions. A better understanding of the mechanisms by which iNKT cells exert their detrimental effects during COPD is required in the future.

We next sought to decipher the mechanisms of CS-dependent activation of iNKT cells. iNKT cells can be stimulated by the mobilization of their TCR and/or by cytokines produced by stressed APC, particularly IL-1β, IL-12, and IL-23.9, 26 Analysis of lung APC subsets from COPD mice indicated that CD11b+ DC strongly matured and expressed markers associated with iNKT-cell activation, including CD1d, IL-1β, and IL-12. Modulation of expression of some glycosyltransferases involved in lipid metabolism in APC is associated with iNKT-cell activation through the presentation of self glycolipids by CD1d.26, 35, 36 Of interest, the mRNA level of Ugcg, a key enzyme implicated in the generation of endogenous iNKT-cell ligands, was strongly induced in CD11b+ DC during COPD. Importantly, the capacity of CSE-exposed DCs to activate iNKT cells was confirmed in vitro, both in the mouse and human systems. While DC are critical activators of iNKT cells, other lung cells such as AEC can express CD1d,37 although their potential capacity to activate iNKT cells has not yet been examined. We herein showed that both mouse and human AEC sense CSE to trigger iNKT-cell activation. Although DC induced both IFN-γ and IL-17 release, CSE-treated AEC only induced IFN-γ production. The mechanisms responsible for iNKT-cell activation in response to CSE-exposed sentinel cells are still unknown and worth of future investigations. Our preliminary data using transwells and neutralizing anti-CD1d Abs suggest a major role for both membrane-bound molecules and a complementary participation of soluble factors in iNKT-cell activation. The differential expression of activating factors by CSE-stressed DC vs. AEC might explain the different profile of cytokines released by iNKT cells. Whatever the mechanisms, our data clearly show a direct link between oxidative stress and iNKT-cell stimulation, as NAC treatment ablated the capacity of CSE-treated DC and AEC to activate iNKT cells. As NF-κB activation is a hallmark of CS-induced oxidative stress in APC,38 it is possible that NF-κB-mediated expression of cytokines, CD1d, and/or glycosyltransferases is involved in iNKT-cell activation.

In vivo preventive NAC treatment reversed COPD symptoms. This protective effect was associated with a reduced accumulation and activation of iNKT cells, demonstrating the intricate between oxidative stress, iNKT cells, and COPD. These data might explain some of the beneficial effects of anti-oxidant treatment in COPD patients.28 Indeed, NAC affects different signaling pathways, such as NF-κB and MAPK in APC,39 that could in turn alter iNKT-cell cytokine production, and lead to decrease COPD symptoms,

Altogether, our data identified of a new pathogenic mechanism leading to COPD. Elucidating the mechanisms by which oxidative stress activates iNKT cells will be important for the understanding of COPD physiopathology. Direct targeting of APC may provide a potent therapeutic strategy for specifically dampening iNKT-cell activation and controlling lung damage due to COPD.

Methods

Patients with COPD. Peripheral blood and induced or spontaneous sputum were collected in stable COPD patients (n=28) and in non smoker healthy controls (n=7) (CPP 2008-A00690-55) in order to evaluate the phenotype of iNKT-cell and DC as well as cytokine concentrations.

CS exposure. Mice were exposed to CS generated from 5 cigarettes per day, 5 days a week, and up to 12 weeks (Emka, Scireq, Montreal, QC, Canada). The negative-control group was exposed to ambient air. NAC (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) was administrated in the drinking water (300 ng per mouse day), from the beginning of the CS exposure till the day of killing.

Cumen hydroperoxide exposure. Mice were intranasally administered either with 50 μl PBS or 75 μg per 50 μl cumen hydroperoxyde (CHP; Sigma-Aldrich) on days 0, 2, and 4. Mice were killed on day 5 to assess their lung function and inflammation. In adoptive transfer experiments, sorted WT iNKT cells were injected intravenously into Jα18−/− mice 1 day before the first exposure to CHP.

Measurement of lung function. Lung function was assessed by invasive measurement, as previously described.40 Aerosolized methacholine (Sigma, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) was administered in increasing concentrations (from 2.5 to 160 mg ml−1 of methacholine). We computed airway resistance, dynamic compliance, and lung elastance by fitting flow, volume, and pressure to an equation of motion (Flexivent System, Scireq).

NKT purification, expansion and adoptive transfer in mice. iNKT cells were sorted using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences, Le Pont de Claix, France), from the livers of naive animals, on the basis of PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer and TCRβ staining. Freshly sorted iNKT cells were expanded ex vivo and maintained in culture for 1 month in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) containing 30 ng ml−1 IL-15 (Peprotech, Neuilly Sur Seine, France). For adoptive transfer experiments, Jα18−/− recipient mice were inoculated intravenously either with 1 × 106 purified WT or Il-17−/− iNKT cells or with the same volume of medium alone 24 h before exposure to CHP. iNKT-cell purity after sorting was >98%.

Pulmonary APC cell sorting. Pulmonary APC were sorted using a FACSAria on the basis of F4/80, CD11c and CD11b expression. AM CD11b− and CD11b+ DC were sorted. Cell purity after sorting was >98%. Post-sort analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of CD103 on DC subsets. As expected, CD11b− DC subset was CD103+ (97% purity) and CD11b+ DC subset was CD103− (98% purity) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Cytokine quantification. The concentration of human IL-4, IL-17, IFN-γ and TNF-α (R&D systems, Lille, France) in coculture supernatants were determined by ELISA. Mouse IL-2, IL-4, IL-17, and IFN-γ concentrations were measured in supernatants of coculture by ELISA (R&D systems).

Reverse Transcriptase-PCR (RT–PCR) analysis. Quantitative RT–PCR was performed to quantify mRNA of interest (Supplementary Table 1). Results were expressed as mean±s.e.m. of the relative gene expression calculated for each experiment in folds (2−ΔΔCt) using β-actin as a reference, and compared with controls (air).

Statistical analysis. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. The statistical significance of differences between experimental groups was calculated by a one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni post test or an unpaired Student t-test (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The possibility to use these parametric tests was assessed by checking if the population is Gaussian and the variance is equal (Bartlett's test). Results with a P-value <0.05 were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the generous support from the NIAID Tetramer Facility (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) for supplying CD1d tetramers. We gratefully acknowledge Drs T. Nakayama and M. Taniguchi (RIKEN Institute, Yokohama, Japan) for the gift of Jα18−/− C57BL/6 mice, Dr L. Van Kaer (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) for Cd1d−/− mice, and Dr B. Ryffel (Orléans, France) for the IL-17−/− mice. We also thank Eva Vilain and Gwenola Kervoaze for their excellent technical assistance, and Emeric Duruy (MicPal Plateform, Institut Pasteur de Lille, France) for his help on cell sorting on FACS Aria Flow Cytometer. This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Inserm), the CNRS, the University of Lille Nord de France, the Pasteur Institute of Lille, and the Region Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/mi

Supplementary Material

References

- Rabe K.F., et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A.D., Murray C.C. The global burden of disease, 1990-2020. Nat Med. 1998;4:1241–1243. doi: 10.1038/3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino D.M., Buist A.S. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet. 2007;370:765–773. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church D.F., Pryor W.A. Free-radical chemistry of cigarette smoke and its toxicological implications. Environ Health Perspect. 1985;64:111–126. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8564111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R.H., Estabrook R.W. The mechanism of cumene hydroperoxide-dependent lipid peroxidation: the significance of oxygen uptake. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;251:336–347. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosken C.H., Hards J, Gatter K, Hogg J.C. Characterization of the inflammatory reaction in the peripheral airways of cigarette smokers using immunocytochemistry. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:911–917. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.4_Pt_1.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnula V.L. Focus on antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant strategies in smoking related airway diseases. Thorax. 2005;60:693–700. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.037473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Hulst A.,I., et al. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema in scid-mice. Is the acquired immune system required. Respir Res. 2005;6:147. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutkiewicz R.R. CD1d ligands: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J Immunol. 2006;177:769–775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel M.L., et al. Identification of an IL-17-producing NK1.1(neg) iNKT cell population involved in airway neutrophilia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:995–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge G, Hodge S, Li-Liew C, Reynolds P.N., Holmes M. Increased natural killer T-like cells are a major source of pro-inflammatory cytokines and granzymes in lung transplant recipients. Respirology. 2012;17:155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge S, Hodge G, Nairn J, Holmes M, Reynolds P.N. Increased airway granzyme b and perforin in current and ex-smoking COPD subjects. Copd. 2006;3:179–187. doi: 10.1080/15412550600976868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendelac A, Savage P.B., Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J.C., Ragin M.J., August A. Natural killer T cells: rapid responders controlling immunity and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1337–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis E.E., et al. CD1d-dependent macrophage-mediated clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from lung. Nat Med. 2002;8:588–593. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari O., et al. Essential role of NKT cells producing IL-4 and IL-13 in the development of allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2003;9:582–588. doi: 10.1038/nm851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisbonne M., et al. Cutting edge: invariant V alpha 14 NKT cells are required for allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in an experimental asthma model. J Immunol. 2003;171:1637–1641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichavant M., et al. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. J Exp Med. 2008;205:385–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.Y., et al. Persistent activation of an innate immune response translates respiratory viral infection into chronic lung disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:633–640. doi: 10.1038/nm1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge G, Mukaro V, Holmes M, Reynolds P.N., Hodge S. Enhanced cytotoxic function of natural killer and natural killer T-like cells associated with decreased CD94 (Kp43) in the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease airway. Respirology. 2013;18:369–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanowicz R.A., Lamb J.R., Todd I, Corne J.M., Fairclough L.C. Enhanced effector function of cytotoxic cells in the induced sputum of COPD patients. Respir Res. 2010;11:76. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Urbanowicz R.A., Tighe P.J., Todd I, Corne J.M., Fairclough L.C. Differential activation of killer cells in the circulation and the lung: a study of current smoking status and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motz G.T., et al. Chronic cigarette smoke exposure primes NK cell activation in a mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2010;184:4460–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunninghake G.M., et al. MMP12, lung function, and COPD in high-risk populations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2599–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paget C., et al. Activation of invariant NKT cells by toll-like receptor 9-stimulated dendritic cells requires type I interferon and charged glycosphingolipids. Immunity. 2007;27:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I, Adcock I.M. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I, Kilty I. Antioxidant therapeutic targets in COPD. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:707–720. doi: 10.2174/138945006777435254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi S.Y., et al. Invariant natural killer T cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology. 2010;17:486–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayanand P., et al. Invariant natural killer T cells in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1410–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn J.F., Crowe C.R., Kolls. J.K. TH17 cells in asthma and COPD. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:495–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen N, Wang J, Zhao M, Pei F, He. B. Anti-interleukin-17 antibodies attenuate airway inflammation in tobacco-smoke-exposed mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2011;23:212–218. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.559603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusselle G.G., Joos G.F., Bracke K.R. New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60988-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Machen M., et al. Pulmonary NKT cells play an essential role in mediating hyperoxic acute lungInjury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:601–609. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0180OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hercend T., et al. Natural killer-like function of activated T lymphocytes: differential blocking effects of monoclonal antibodies specific for a 90-kDa clonotypic structure. Cell Immunol. 1984;86:381–392. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann J., et al. Differential alteration of lipid antigen presentation to NKT cells due to imbalances in lipid metabolism. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1431–1441. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougan S.K., Kaser A, Blumberg R.S. CD1 expression on antigen-presenting cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;314:113–141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown V, Elborn J.S., Bradley J, Ennis M. Dysregulated apoptosis and NFkappaB expression in COPD subjects. Respir Res. 2009;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosset P, Wallaert B, Tonnel A.B., Fourneau C. Thiol regulation of the production of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-8 by human alveolar macrophages. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:98–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a17.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T.R., Gerard N.P., Galli S.J., Drazen J.M. Pulmonary responses to bronchoconstrictor agonists in the mouse. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2318–2323. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.