Abstract

Background

Refugees experience dietary changes as part of the daily challenges they face resettling in a new country. Sudanese women seek to care and feed their families, but face language barriers in the marketplace, limited access to familiar foods, and forced new food choices. This study aimed to understand the acceptability of a purse-sized nutrition resource, “The Market Guide”, which was developed to help recently immigrated Sudanese refugee women identify and purchase healthy foods and navigate grocery stores.

Methods

Eight women participated in a focus group, four of whom were also observed during accompanied grocery store visits. Individual interviews were conducted with four health care workers at the resettlement center to gather perceptions about the suitability of The Market Guide. Focus groups and interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Data from field notes and transcripts were analyzed using grounded theory for preliminary open codes, followed by selective and theoretical coding.

Results

The Market Guide was of limited use to Sudanese women. Their response to this resource revealed the struggles of women acculturating during their first year in Calgary, Canada. We discovered the basic social process, “Navigating through a strange and complex environment: learning ways to feed your family.” Language, transportation, and an unfamiliar marketplace challenged women and prevented them from exercising their customary role of “knowing” which foods were “safe and good” for their families. The nutrition resource fell short of informing food choices and purchases, and we discovered that “learning to feed your family” is a relational process where trusted persons, family, and friends help navigate dietary acculturation.

Conclusion

Emergent theory based on the basic social process may help health care professionals consider relational learning when planning health promotion and nutrition activities with Sudanese families.

Keywords: nutrition resource, dietary acculturation, Sudanese refugees, grounded theory, health promotion

Introduction

Canada is among the countries that accept and settle refugees, and grant asylum to those seeking safety from war, civil strife, and persecution. Civil wars, long waged in the Sudan, have resulted in the deaths of millions of people, decimation of the Sudanese social infrastructure, and displaced peoples. Approximately 1.25 million internally displaced Sudanese have endured the physical and psychological trauma of war, widespread malnutrition, and a significant disease burden.1–3 Their forced migration has placed them all over the world, including Canada since 1989.3

An estimated 5,000 Sudanese refugees reside in the greater Calgary area, which is believed to be one of the largest Sudanese communities within Canada. Resettlement services offered at the Margaret Chisholm Resettlement Centre provide 10 weeks of accommodation, immediate health services, and links to community services for government-sponsored refugees. New arrivals are diagnosed and treated for infectious and parasitic diseases such as bilharzia, giardia, malaria, post-primary tuberculosis, filarial and fungal infections, hepatitis B, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome/human immunodeficiency virus.4 Malnutrition and micro-nutrient deficiencies, notably of vitamin A, C, D, niacin, and iron, often accompany these diseases.5–9 Anecdotal reports indicated that Sudanese babies were presenting at the local children’s hospital with neonatal rickets, a preventable condition attributable to maternal vitamin D deficiency.9 Although known deficiencies can be corrected by vitamin supplementation, health care workers suggested that this was an unfamiliar practice for Sudanese people, even if supplements were provided.4 These nutritional concerns may be indicative of greater issues faced by Sudanese refugees as they adapt to a new culture, and support the need to further explore how nutrient deficiencies can be treated in a culturally appropriate manner.

Dietary acculturation, part of cultural adaptation, is a multidimensional and nonlinear process that occurs when eating patterns and food choices of the host country are incorporated, adapted, and aligned with traditional practice.10 During resettlement, refugees’ nutritional status may be further compromised when given unfamiliar and sometimes culturally inappropriate foods. Refugees may be challenged to make healthy food choices, given unfamiliar foods offered in a seasonal market among thousands of available products.11 Changes from daily shopping to weekly trips and facing unknown preparation methods for unfamiliar Western type foods are a common experience. Studies from Australia and the USA indicate that African refugees prefer traditional foods, reflecting deep-rooted social and cultural beliefs, but potentially delaying acculturation.12,13 Limited knowledge of available local foods also makes food choices complicated for refugees.14,15 Smartly packaged Western foods in Canada and nutrition labels in French and English challenge consumers from a variety of ethnic backgrounds.

This paper reports a qualitative study that explored the acceptability of a newly developed nutritional resource for recently immigrated Sudanese refugee women, called the “The Market Guide”. Using grounded theory analysis,16,17 we hoped to gain a rich understanding of the experiences of Sudanese refugee women as they made point-of-purchase food choices in unfamiliar marketplaces with an overwhelming array of grocery items. The product of this research was to be the emergence of a relevant theory that might be used to understand the contextual realities of Sudanese women and their thoughts and actions as they undertake the task of feeding their families. It was anticipated that specific interventions to further aid Sudanese refugees and modify The Market Guide would be more likely to emerge through a qualitative approach rather than an empirical, deductive approach.

Materials and methods

Qualitative study

Little is known about how Sudanese women navigate grocery stores in the early days of resettlement. A qualitative inquiry was used to develop a greater understanding of this complex and multifaceted process of dietary acculturation, including choosing and purchasing food. The study design used grounded theory analysis in the tradition of Glaser and Strauss.16 According to Glaser, grounded theory is, “the generation of emergent conceptualizations into integrated patterns, which are denoted by categories and their properties”.17 In this process of conceptualization, each incident is compared with every other data incident as data are acquired. Codes are developed and clustered to form categories, then expanded and developed to form themes that are later linked together to reveal a theoretical process. The interrelationships that occur between categories and amongst their properties create an exemplified theory that becomes more dense and saturated with constant comparison. In essence, the generation of a theory occurs around a core category.18

Development of The Market Guide

In considering the unique needs of recently resettled Sudanese refugees in Calgary, a pilot project was undertaken to develop a new nutritional resource, ie, “The Market Guide: Good Food For You and Your Family”. This portable, washable, pictorial food shopping resource was developed by a nurse-nutritionist (CM) to aid Sudanese refugees with point-of-purchase food choices and to encourage selecting foods rich in iron, calcium, and vitamin D. The Market Guide was a purse-sized flip booklet (see Figure 1) with pictures of fresh and packaged foods on color-banded pages corresponding to the four groups of the Canada Food Guide for Healthy Eating.19 An additional “sometimes foods” group was created to denote high-calorie, nutrient-poor, snack-type foods. The Market Guide was also designed to discourage selecting foods high in fat with low nutrient density. It featured pictures of unlabeled, unpackaged, nutrient-dense foods while opposing pages outlined the number of servings recommended by the Canada Food Guide for Healthy Eating for pregnant/breast-feeding women, children, and adults. A standard grocery store map and a recipe section of traditional Sudanese dishes were also included, with the ingredients color-coded to match the Canada Food Guide for Healthy Eating food groups.

Figure 1.

The Market Guide purse-sized flip booklet.

Participants

Care was taken in approaching refugee women for participation in the study, given that their history of displacement and trauma may have compromised their mental health and physical well-being. Newly resettled Sudanese refugee women were purposively sampled for participation in a focus group and a grocery store visit accompanied by a female research assistant. Sudanese women met the inclusion criteria for the study if they were aged 18 years or older and had lived in Canada for less than one year. Recruitment was conducted by staff from the Margaret Chisholm Resettlement Centre who had knowledge of the participants’ physical and mental health to ensure ethical recruitment. Potential participants were excluded if staff at the center believed study participation would cause unnecessary psychological strain.

Twenty potential participants were identified and invited to: attend an information meeting and receive The Market Guide; participate in a focus group; and have a female research assistant and translator accompany them on a typical grocery store visit. The information session at the Margaret Chisholm Resettlement Centre was facilitated by two research assistants, an Arabic-English speaking translator, and some intake workers. Eight women participated in the focus group, and four went on accompanied grocery store visits with the same research assistants involved in the focus group (see Table 1 for participant characteristics).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Participant 1 | Participant 2 | Participant 3 | Participant 4 | Participant 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29 | 22 | 34 | 29 | 22 |

| Time in Canada | 7 months | 4 months | <1 year | 5 months | 3 months |

| Highest level of education | High school | Grade 4 | Not provided | None | University |

| Rural or urban upbringing | Urban | Rural | Urban | Urban | N/A |

| Marital status | Married | Married | Married | Married | Married |

| Sex (M/F) and age of Children | F, 2 years | M, 2 years M, 5 years |

8 childrenb | F, 3 years F, 6 years |

None |

| Religious background | Christian | Muslim | Muslim | Christian | Muslim |

| Type of grocery stores frequenteda | Supermarket | Supermarket | Supermarket | Supermarket | Supermarket |

| Halal | Halal | Halal | Halal | Halal | |

| Specialty | Specialty | Specialty | Specialty | ||

| Chinese | Chinese | ||||

| Specialty | Specialty | ||||

| Frequency of shopping trips | 14 days | 14 days | 7 days | 7 days | N/A |

| Participated in grocery shopping trip | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Noc |

Notes:

Supermarket denotes a departmentalized, self-service store offering a wide variety of food and household merchandise; Halal specialty denotes a specialty store featuring Halal and Arabic foods; and Chinese specialty denotes a specialty store featuring Asian foods

participant did not specify ages or gender of children

this participant initially agreed to participate in the grocery trips but later refused due to lack of permission from her spouse.

Health care professionals who provided direct services and could have potentially used The Market Guide as a counseling tool with the Sudanese population were invited to participate in semistructured interviews. Two Sudanese Canadian intake workers, a public health nurse, and the center’s current medical director participated in the interviews.

Data generation

Focus group

The 45-minute focus group was held at the resettlement center where lunch, bus tickets, and childcare were provided. The focus group was conducted in Arabic by two trained research assistants in the common room. The interview guide was designed to promote discussion focused on food preferences, eating behavior, and grocery shopping, in addition to perceptions about the content, layout, and use of The Market Guide. The focus group was audiotaped with permission from each participant, from which transcripts were made using three translators and double-verified by a lead translator. Both research assistants provided field notes to capture the ambience and tenor of the discussion. Demographic information included age, time in Canada, rural or urban upbringing in Sudan, marital status, number of children, religious background, and grocery stores used.

Observations during grocery store visits

Four women were accompanied on a grocery shopping trip by two research assistants. A research assistant contacted participants to arrange accompaniment on their next regularly planned grocery shopping trip, and provided taxi transport. Research assistants arranged to meet and transport each participant to their regular grocery store of choice, and noted purchases and fielded questions. One research assistant was a silent observer and the other Arabic-speaking research assistant interacted with the participant. Observation of shopping behaviors included the path taken through the grocery store, selection behaviors including product or price comparisons (if made), and a recording of questions or comments made by the participant. Assistance with grocery shopping decisions was avoided. Field notes were compiled after each visit, with recorded impressions, environmental issues, behavioral mannerisms of the participant, phrases used, and other thoughts that occurred during the time together. These field notes were used later in the analysis process for constant comparison.

Interviews with health care professionals

Open-ended interviews with health care professionals and facilitators at the resettlement center were conducted within the same time frame. Guided questions focused around the interviewee’s experience with the nutritional issues faced by the resident Sudanese refugee population and with The Market Guide. Interviews lasted between 15 and 45 minutes, and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Consistent with the qualitative method grounded theory,16 data analysis was carried out concurrently with data collection until all data were analyzed. Synchronicity of data collection and analysis is a hallmark of grounded theory methodology, with new pieces of data adding depth to the inquiry.16 By using a constant comparative approach in the data gathering and coding stages, we built a theory grounded in the data. Analysis proceeded at the completion of the focus group and as the grocery store visits took place, resulting in identification of categories and themes.

A minimum of two members of the research team read the transcripts and identified possible beginning coding categories (substantive coding), moving from raw verbatim data to abstract ideas and concepts. Atlas TI software (ATLAS.ti GmbH, Cologne, Germany) was used to begin open coding, and then the codes were grouped to identify processes and underlying patterns. Coding occurred at three levels using the Glaser and Strauss16 approach, ie, open, selective, and theoretical. New categories were identified as necessary to cover all relevant data. Refitting and refinement of categories continued until a core variable was identified. The core variable clarifies “what’s going on in the data” and becomes the basis for the generation of the theory.

Rigor

The rigor of this grounded theory study was enhanced using a number of methods.18 The collective backgrounds of the research team, ie, a methodological expert in grounded theory (SRB), a nurse-nutritionist (CM), and three research assistants who had previously worked in Africa with displaced people, strengthened the credibility of findings. Accuracy and completeness of the data were maximized by having two research team members at the focus group and grocery store visits, and by audiotaping and transcription of interviews. Participants’ own words were also used to name the categories and at multiple levels of coding to ensure interpretations were grounded in the data. Field notes and memos were used to articulate the personal views and insights of the research team. A decision trail was kept to enhance auditability, including audio recordings, transcripts, field notes, and memos.

Ethical issues

Ethics approval was granted by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, University of Calgary (E-ID 20132). Limited literacy and low levels of written and spoken English required verbal consent (assent) witnessed by a third party. It was emphasized to the participants that receipt of The Market Guide or continued access to nutritional counseling was not contingent upon participation. In the interest of cultural sensitivity and to facilitate an environment in which participants felt comfortable sharing, only female translators and research assistants interacted with participants.

Results

Perceptions of The Market Guide

Overall, The Market Guide was not well received by the participants, because it embodied many of the barriers women faced daily, ie, a strange language, unknown foods, unfamiliar store layout, and limited knowledge of nutritional recommendations. “These are difficulties we face when we move to a new country. Everything is hard to overcome; the language, the foods, the climate, the culture, everything.” (Participant 2)

One health care professional remarked, “Many of the people aren’t literate in their own languages either, so the fact that it’s pictorial is really, really critical.” While predominantly pictorial, the use of English labels in The Market Guide presented a language barrier. All participants reported that pictures without translated labeling were not helpful. “There are pictures in it but they are written in another language, English, not my language – Arabic or Sudanese. It is not helpful to me at all.” (Participant 2). Traditional recipes included in The Market Guide remained foreign, so were captured in the wrong language.

Intended to facilitate shopping in the grocery store, The Market Guide included a typical grocery store map but it was uncommon knowledge to many that grocery stores followed a layout plan. One health care professional said, “The layout of the grocery store; I had no idea that grocery stores were all laid out … your fresh stuff around the outside, and the non-perishables in the middle.” Health care professionals were not aware of several features included in The Market Guide, and if asked, could not provide guidance to the woman.

Unintentionally, The Market Guide became a forum for revealing the difficulties faced by women during their first year in Calgary. During the focus group and accompanied grocery store visits, women expressed the complexities of navigating the unknown as they attempted to enact their role of feeding their families.

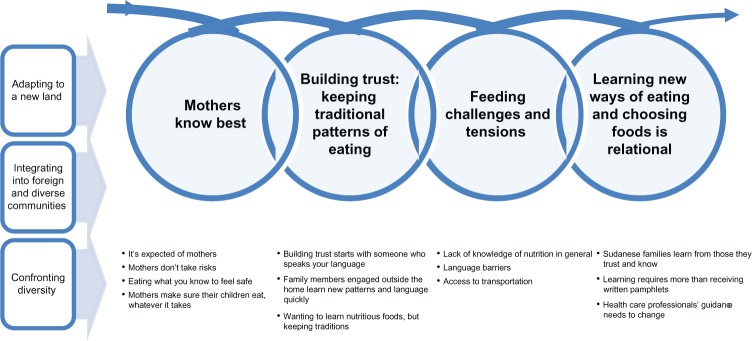

Basic social process

Through the process of constant comparison and conceptualization, the core category “Navigating through a strange and complex environment: Learning ways to feed your family” emerged. The word “navigate” comes from the Latin navigus, meaning “to guide” or to “steer”. Navigating through a strange and complex environment characterized the families’ experience and was a continuing process (Figure 2). Feeding the family is a basic social process that exemplifies the psychosocial and cultural issues recurring throughout the family’s journey in a new culture and country. The perspectives of these Sudanese refugee women revealed that they were engaged in a process of “navigating”, ie, learning how to feed their family in a nutritious but safe manner. Enacting their role as women and mothers, they navigated a new culture and confronted diversity.

Figure 2.

Navigating “Learning How to Feed Your Family in a New Country”.

The psychosocial processes were categorized as: “ mothers know best”, building trust: keeping traditional patterns of eating; feeding challenges and tensions; and learning new ways of eating and choosing foods is relational. Discussion of these categories will illuminate the process of the participants’ journey in feeding their family in a new culture and identifying barriers to eating healthy, safe, traditional, and nontraditional foods.

Women become engaged in activities during acculturation including: assuming the sole role of feeding the family; adapting to a new and diverse people and their communities; adapting to a new environment; seeking places to buy appropriate foods; and going to unfamiliar grocery stores and attempting to learn about new foods. These activities (dimensions) convey that the navigation process is not limited to a particular course. The women face barriers and failures, along with successes in their journey of feeding their families. It is these dynamic dimensions that create tensions and relief along the journey. While the dimensions are presented sequentially for ease of explanation, they were overlapping and iterative.

“Mothers know best”

Accompanying the desire to provide the right foods for their family, women experienced feelings of isolation, and uncertainty. These feelings presented in varying intensities as they sought out ways to feed their families that also met their traditional expectations. As mothers witnessed their families eating the meals they prepared, they became more confident and settled into a period of relative stability. However, later precipitating events, such as the children wanting only Western foods, sent mothers into uncertainty again.

“It’s expected of mothers”

Participants emphasized the importance of feeding their families as part of their role as women and mothers. In their culture, Sudanese women have the traditional role of feeding their families.21 All women indicated that feeding their family was a central responsibility that they took seriously, but in a new culture, many factors affected their ability to carry out this role. One woman said, “I often go with my husband, who reads and understands the labels of the food items more than I do. If he is not with me, I never go grocery shopping. He has to come with me all of the time.” (Participant 5).

“Mothers don’t take risks”

Mothers communicated that selecting nutritious foods was both a priority and a role expectation. Participants noted that mothers do not take risks when feeding their families. “As a mother, you can only give your children the foods that you are knowledgeable and know about. If I don’t know much about other foods, I never give them to my children. It is just not worth the risk.” (Participant 3). They recognize challenges in a new food environment, and without nutritional knowledge or recognizing the food in the store, they are “not willing sacrifice or take the risk” with new foods.

“Eating what you know to feel safe”

Culturally, a Sudanese mother serves “foods that are safe to eat”. Participants mentioned that their lack of knowledge contributed to mistrust of new food products. For example, one participant stated:

Fish and meat products are the most confusing ones for me. I never asked people at the store because I don’t speak good or even bad English. I like to read the dates and where it is made. I never know about these things. That is what I found difficult about grocery shopping in Canada. (Participant 3)

One participant who appeared to be knowledgeable and more confident than others told observers that her family never consumes fast foods or Canadian foods in general because these foods were perceived to be high in fat and cause obesity. She said, “We eat what we know – our food, Sudanese foods.” (Participant 4).

“Mothers make sure their children eat, whatever it takes”

Children’s eating patterns caused great concern and stress for mothers. This stemmed from children’s preference for Western food items, such that there were only certain foods they would eat: “cookies and cereal, candies, drinks and milk.” This compromised their perceived motherly duty to ensure children eat nutritious foods, but the preferences were grudgingly accepted. Another mother offered her observation:

Sometimes they eat and sometimes they don’t. We often have difficulties with their food habits. They prefer cookies and drinks instead. You cannot force them to eat traditional foods. At times, they want to eat the fast food – things you find in Canadian stores and are not interested in eating good foods or nutritious foods. This is what we would like to know about children diets and foods. (Participant 5)

Mothers carefully navigate fluctuating eating patterns of their children. Sometimes, to ensure that their children eat, mothers feed their children “whenever they ask for food … . that is what we are supposed to do as good mothers.” (Participant 3)

Sometimes I get tired of forcing them and I give up on them. My children never eat what I cook for the family … It is very frustrating for a mother when her children refuse to eat what she cooks for her family. These are the difficulties we face when we move to a new country. (Participant 2)

Building trust: keeping traditional patterns of eating

Building trust starts with someone who speaks your language

Feeling comfortable in a new culture begins the journey towards successfully feeding the family. Building trust is possibly an evolving process, starting with someone from one’s culture and later extending to others. The data revealed that many families who come to Canada from Sudan have relatives or established friends in Calgary who share a language. Families learn through relatives, friends, or Sudanese community members who explain new foods, and the availability and location of desired foods; however, newcomers often choose traditional foods over unfamiliar Canadian foods.

Family members engaged outside the home learn new patterns and language quickly. The process of “fitting in” seemed more challenging for adult women who were isolated due to lack of exposure to the community and not part of the workforce, and who were unsure of distances between home and shopping centers. “All I do now is to rely on my husband, which is sometimes too much for both us.” Children and men who were in the community, at school, or at work seemed to “learn or be easily adopted or introduced to new food, depending how conducive the environment might be for them to change.” (Participant 1). This was echoed by one interpreter:

Children also play a role in finding new foods. Children may come and help with the grocery shopping and based on the foods, which they learn about in school, and those which they may try with friends at school, they learn about new foods and will tell the family if it is good or bad for them to try.

Wanting to learn about nutritious foods but keeping traditions

To function as members of society, each mother spoke of the need to understand, socialize, and integrate into the new culture. In the focus group, several participants shared the following belief:

And then, you can make the connection between traditional Sudanese foods and western foods. This is where the whole confusion comes in. We are used to and exposed to different African and Sudanese dishes and diets prior to our resettlement in Canada. But when we come to this country without the basic knowledge needed for effective shopping strategies and familiarizing ourselves with new foods and purchasing techniques here in Canada, one can never escape from the old traditional poor dieting. (Participant 1)

This process of “fitting in” was difficult. These women acknowledged that Sudanese people tend not to integrate easily into the broader community, rather staying within the familiar Sudanese community. Several women shared that “friends or relatives [ship] ingredients to us through the mail” or that they had brought over specific regional spices or ingredients for traditional Sudanese dishes, particularly for Combo (mixed dried fish, vegetables, and spices).

We start from scratch because the ingredients are not cooked and all you need to do is put them together and cook them. You put spices in it and you make it the way you prefer. (Participant 4)

Participants described that adults, rather than children, generally ate three to four meals a day of “Sudanese foods and not Canadian foods”. Meals were comprised of “the type of foods we are familiar with and know how to make and prepare”, including rice with Sudanese ful (beans), meat, fish, or chicken stews, kisra (pita bread made of corn or sorghum flour), mulukhiya (spicy steamed vegetables), salad, and beverages (cola, orange juice).

Challenges and tensions of feeding and eating

General lack of knowledge about nutrition

Sudanese refugee women repeatedly expressed an interest to learn about new nutritious foods. Many tensions challenged them in becoming more knowledgeable about nutrition and the process of feeding their families in a new culture.

I want to learn everything about grocery shopping in Canada. It starts with how to read the food labels and understanding the nutritional importance of foods. I want to learn where to find good foods outside of the Halal meat stores. I mean, in Canadian food stores. I want to learn everything about food. (Participant 5)

Understanding the process of grocery shopping adds another layer of complexity to making nutritious food choices in Canada. Factors that influenced food purchases included how Canadian grocery stores operate, location of grocery store items, and recognizing packaged foods. Several women assumed that if a grocery store makes food available for sale, “… it must be good to eat and good for you.” Consequently, purchasing sweets, crisps, soda, and other foods lacking nutrient density was justifiable.

Language barriers

Lack of English literacy impacted successful food selection. This was often related to inability to read labels. Observers noted that some women never asked questions about the nutritional content of food and showed little interest in foods differing from the Sudanese traditional diet, and selected few foods from The Market Guide. In addressing the language barrier (written and verbal), another participant suggested that, “[…] maybe the stores should hire employees who speak different languages, so that a person like me can get help with shopping.” (Participant 3).

Access to transportation

None of the participants drove and most did not know their address and/or directions home, hindering the use of public transit. Cultural constraints prevented use of taxis because that would place women alone with a male driver, who is a “stranger”. Inaccessible transportation increased the women’s sense of isolation and reliance on their husbands. One health care professional also offered, “It must be a big challenge to get the family all bundled up. Mom and dad, and six kids, go to the grocery store, you try to figure out what is what … . Uh! And you go on the bus and you try to take it all home on the bus or the C-train.”

Learning new ways of eating and choosing foods is relational

Sudanese families learn from those they trust and know

We found that learning new skills is relational. Families seemed to learn primarily through relatives, friends, or the Sudanese community regarding availability of foods, desirable foods, and how to prepare them. Ethnic stores where the likelihood of speaking Arabic was high offered a trustworthy environment. “In the Halal meat stores, even if there are no clear guidelines, you can still be guided by the people at the store.” (Participant 2). Another participant said, “I often have difficulties with picking the right food items. The few things I know, I learned through other Sudanese friends who came to Canada before me and can read English.” (Participant 1).

Learning requires more than receiving a written pamphlet

Although The Market Guide was intended as “a tool that people can use, to hopefully become familiar with the foods”, as one health care professional described, Sudanese women had many questions about the content of the resource that necessitated further intervention. For example, there was unfamiliarity surrounding food items featured in The Market Guide, demonstrated in this interaction during the focus group:

Participant 1: I do recognize some but not many of [the pictures]. Just few basic things like milk and meat. That is all.

Interviewer: Are there any pictures in the guide you don’t recognize?

Participant 1: Yes, some.

Interviewer: Like what? Can you name it?

Participant 1: Like this. What is the name of this?

Interviewer: The name of that is broccoli.

Participant 4: There is another one. This one. I don’t know the name.

Interviewer: It is called cauliflower.

Participant 5: How do you cook it and what is it good for?

Health care professionals need to consider the relational approach through which knowledge is gained by the Sudanese. Beyond a clinical consultation, one health care professional recommended,

It would be useful if, you know, there was someone that could um, you know, go on a grocery store tour with these clients and show them how to use … it right, in the grocery store.

Guidance from health care professionals needs to change

Learning is further complicated by the time constraints of health care professionals (eg, short clinic visits), contributing to less relational interactions with newcomers. Such practices are not found helpful by the Sudanese. Potential exists for The Market Guide to be used in conversation with families, one-on-one to teach use of the guide, and then to accompany families to the grocery store to provide guidance and teaching. A resettlement center interpreter described:

If newcomers are going grocery store shopping with someone who can explain things to them and help them understand, and through this process they gain an understanding of what they need and what they do not need. If they do not have assistance or means of understanding which foods are good to buy and which are not good, many families will just choose whatever: pop, chips, cookies, considered to be good food for kids. This is reinforced when the kids enjoy eating these types of foods.

Reflecting this perspective, numerous American resettlement agencies have started assisting refugees with “how to shop effectively at the grocery store”.22

Discussion

Dietary acculturation influences dietary intake. We found that the women in this study wanted to learn about nutrition and integrate parts of the Canadian diet, while retaining traditional food choices. Foods commonplace in Canadian markets were new and unknown to Sudanese women, thereby restricting their food choices. Rather than a resource such as The Market Guide, family and friends were the key nutrition resource, informing newcomers, “This is good for you; this contains vitamins.” However, in keeping family as the primary translator of information, myths are reinforced, new foods may never be tried, and poor nutritional decisions may become a deeply rooted part of acculturated life.

Grounded theory allowed us to use The Market Guide as a vehicle to understand the behaviors and perceptions of Sudanese women as they tried to enact their traditional role in a strange country with an unshared language. The grounded theory method does not test hypotheses, but stimulates them. Our theoretical model depicts how Sudanese women care for and feed their families, and why The Market Guide was problematic for them. The relevance of this theory lies in understanding that a brochure or booklet will not effectively address issues faced by Sudanese women because trust is paramount to accepting new information and trying new things. As such, food shopping and eating patterns may not change, despite mothers wanting the best for their families.

Current findings support that the process of dietary acculturation is complex and bounded by many tensions. Personal and social contexts affect the timing and ease of adjustment, while exposure to a new culture with new nutrition guidelines can contribute to an “eating culture shock”.22 Participants found dietary acculturation challenging, likely because it was early in their own acculturation process and there were other pressing needs to consider, such as health, housing, and employment.22 Dietary acculturation is facilitated by time in the host country, education, and increased exposure to the host culture via employment or social activities.23 These events are not easily available to new refugee women who are expected to maintain their traditional role. Food selection and purchasing during grocery shopping were complicated by language, transportation, and unfamiliar grocery stores. Sudanese mothers expressed feelings of isolation, unrelieved due to limited exposure outside the home and unfamiliar people such as store employees.

Retention of food practices is rooted within cultural identity and tradition. Lack of food knowledge in Canadian grocery stores and a reluctance to ask questions resulted in inability of the women to assess for perceived food safety. Changes in food choices have signaled a cultural loss, leading to a role shift as women struggle to acculturate.23 Mothers in our study wanted to fulfill their traditional role of feeding the family, but were hindered by language, transportation, and cultural barriers. The women expressed a desire to maintain traditional food choices while also incorporating new nutrition information, but lacked the resources and skills to achieve this alone. Studies of Somali refugees in Australia revealed that mothers viewed traditional eating patterns as an important part of their cultural heritage, and struggled to maintain this under changing family routines and pressure from children to incorporate new foods.22 Two studies addressing dietary acculturation among resettled African refugees in the USA found that children influenced food purchases, and further tension was created by the differing food preferences between their husbands and children.15,23 Our participants experienced similar tensions: mothers wanted to indulge children’s food preferences so they would not go hungry, but were caught between the role-fulfilling task of feeding the family and a desire to feed traditional foods. In their country of origin, considering limited food variety and availability, such tensions may not have existed, and it remains to be determined whether mothers can successfully uphold their traditional role in the new culture.

Participants emphasized that part of their role as mothers was to feed their family “safe” foods, synonymous with “known” foods. Consequently, trust and distrust were central to the process of feeding the family. Two reports exploring dietary changes among Southern Sudanese refugees in Cairo also noted the importance of trust and distrust.12,24 Ainsworth24 found that Sudanese refugees believed milk products, peanuts, and meats were “not safe” in the new country, a distrust which lowered consumption levels of these foods below those reported for life in Sudan. Among resettled Sudanese refugees in Nebraska, distrust and confusion about milk sources was noted by Willis and Buck.15 Milk is an important source of calcium and vitamin D. Sudanese refugees have suspected deficiencies in these nutrients, which will remain unalleviated with decreased milk consumption stemming from distrust. If Canadian foods or grocery shopping provoke a similar response among the Sudanese, distrust poses a unique challenge to nutrition education. This reinforces the importance of learning through relationships founded upon trust.

Trusted foods are traditional and familiar. Similar to other reports, our participants had difficulties identifying appropriate substitutions for familiar food.12,15,22,24,25 Food choices were restricted by decreased availability, affordability, foods considered “not fresh enough”, foods of poor quality, and lack of familiarity with new foods. Similar problems among Sudanese and other refugee groups transitioning to higher income countries have been noted.20,22,23,25 These problems can decrease the variety of foods consumed,24 lowering the nutrient base from which nutrient requirements are met. This can result in nutrient deficiencies. As such, a culturally sensitive means of familiarizing women with nutritious foods must be developed. This may involve trying foods in a relational context, through a respected or long-settled Sudanese refugee.

Although featuring food pictures, The Market Guide was unsuccessful in affecting food choices. Renzaho25 also found Sub-Saharan African immigrants were unlikely to accept information when offered in an unfamiliar language or form. Similar to other work,23 our sample could not use The Market Guide as it was intended because the women lacked the knowledge to purchase, prepare, and cook the new foods featured and/or read the recipes included. Willis and Buck15 noted that few Sudanese refugees had the skills to select nutritious foods from the overwhelming variety available in grocery stores. Our results are supported by other researchers, and suggest that African refugees rely heavily on personal support from other refugees and professional intake workers for advice.23,26

While aware of nutritional deficiencies common to newcomers, health care providers often lack cultural training to specifically address dietary and food choices.27 The US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants28 recently designed a nutrition education resource for service providers accentuating meal planning, purchasing items from a grocery store list, and knowing the layout of the food store. The Market Guide included a grocery list and a grocery store map indicating the location of foods, directed towards shoppers, not health care providers.

Nutrition education programs, given in an atmosphere where trust and respect are cultivated within relationships, overcome several barriers that illiteracy and unfamiliarity pose.29 Relationships are foundational to effective translation of information for Sudanese women in a new culture. The Market Guide failed because it was not relational, with the context being flat, nonverbal, and nonengaging. The Market Guide may have a role in nutrition counseling, but its effectiveness will be limited unless introduced within a trust-based relationship. In this context, The Market Guide could help development effective shopping strategies through food and picture recognition. Improving The Market Guide may include adding headings in those dialects understood by women, ie, Arabic, Nuer, and Dinka. The Market Guide would also have to reflect the updated Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide.30 Participants openly expressed their desire to learn about foods in the Canadian market place, but could not decipher food labels. The Market Guide did not include an explanation of food labels.

While we expected The Market Guide to be more favorably received and have some success, other factors may have contributed to the frustration women experienced using the resource. The research team noted that men often manage family finances and help women with the grocery shopping, including making point-of-purchase decisions. Few women went grocery shopping alone, and generally only when husbands were at work. Given that husbands who work have more exposure to the new language and culture, they may be a critical resource for women in feeding their families. Husbands or other male family members could have been included in the trial and discussion of The Market Guide.

We experienced difficulties in recruiting participants and carrying out the grocery store visits. Our sample came from a temporary accommodation facility where government-assisted refugees destined for Calgary stay until permanent accommodation is secured. Given refugee status and a relocation experience set upon a background of loss and trauma from war and life in refugee camps, both the facility and the ethics board required that potential participants be screened by health care workers for mental health and their ability to partake. This was additional work for the Margaret Chisholm Resettlement Centre staff and increased the recruitment time. We hoped that the invitation to participate in the focus group at the resettlement center, a known location where newcomers remained in contact after their initial stay, would foster a safe environment for participants to share their stories.

Grocery store visits in the community were more complicated. The five women who agreed to the grocery store observations sought permission from their husbands, although permission for one participant to attend was revoked at the time of the visit. Another husband was assured that his wife would be accompanied to and from the grocery store in the taxi so as not to be left unaccompanied in a car with an unknown male. One participant did not know where her home was in relation to the grocery store and did not know the full details of her address. Another participant brought her son to ensure the presence of a close male relative. As women were typically accompanied by family members during shopping, the lack of their presence during the observations may have altered usual behavior and deference to decision-making.

Conclusion

This qualitative study examined how a nutrition resource was perceived and used by recently immigrated Sudanese refugee women while grocery shopping in the Canadian marketplace. Women engaged in a process of “navigating”, learning to feed their family in a nutritious and safe manner. This was a relational process whereby trusted family and friends helped with advice, experience, and support, which are things The Market Guide could not provide. The literature surrounding refugees and dietary acculturation is predominantly from large urban centers in the USA and Australia. Canada’s open immigration policy ensures that more refugees will continue to immigrate, so it is necessary to better understand dietary acculturation within the Canadian context and rural centers, where settling refugees may find fewer resources and decreased food variety. Although we did not address food intake and health outcomes in Sudanese refugees, this is an area of great importance because how women select family food and what they decide to eat determines eating patterns for their families.31

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Margaret Chisholm Resettlement Centre, the Nursing Endowment Fund, University of Calgary, and the former Calgary Health Region. We would like to acknowledge the research field team, included Halima Mohamed and Tamara Swanson, and a special thanks to Valerie Kiss, Dr Caroline Pim, Prissy Wai Wai, and Bol Abouk. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Jill Norris to the final draft of this paper. We are deeply grateful to the new Canadians who took part in the study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Abusharaf RM. Sudanese migration to the New World: socio-economic characteristics. Int Migr. 1997;35(4):513–536. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franco-Paredes C, Dismukes R, Nicholls D, et al. Persistent and untreated tropical infectious diseases among Sudanese refugees in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(4):633–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newbold B. Health status and health care of immigrants in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(2):77–83. doi: 10.1258/1355819053559074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiss V, Pim C, Hemmelgarn BR, Quan H. Building knowledge about health services utilization by refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grover SR, Morley R. Vitamin D deficiency in veiled or dark-skinned pregnant women. Med J Aust. 2001;175(5):251–252. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxwell SM, Salah SM, Bunn JE. Dietary habits of the Somali population in Liverpool, with respect to foods containing calcium and vitamin D: a cause for concern? J Hum Nutr Diet. 2006;19(2):125–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozza JM, Rodda CP. Vitamin D deficiency in mothers of infants with rickets. Med J Aust. 2001;175(5):253–255. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seal AJ, Creeke PI, Mirghani Z, et al. Iron and vitamin A deficiency in long-term African refugees. J Nutr. 2005;135(4):808–813. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw NJ, Mughal MZ. Vitamin D and child health Part 2 (extraskeletal and other aspects) Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(5):368–372. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satia-Abouta J, Patterson R, Neuhouser ML, Elder J. Dietary acculturation: applications to nutrition research and dietetics. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(8):1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varghese S, Moore-Orr R. Dietary acculturation and health-related issues of Indian immigrant families in Newfoundland. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2002;63(2):72–79. doi: 10.3148/63.2.2002.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ainsworth P. Changing Dietary Practices Amongst Southern Sudanese Forced Migrants Living in Cairo. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo, Forced Migration and Refugee Studies Program; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincenzo R, Crotty P, Burns C, Rozman M, Ballinger M, Webster K. Easing the transition: food and nutrition issues of new arrivals. Health Promot J Austr. 2000;10(3):230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruseman M, Barandereka N, Hudelson P, Stalder H. Post-migration dietary changes among African refugees in Geneva: a rapid assessment study to inform nutritional interventions. Soz Praventivmed. 2005;50(3):161–165. doi: 10.1007/s00038-005-4006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis MS, Buck JS. From Sudan to Nebraska: Dinka and Nuer refugee diet dilemmas. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(5):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL, USA: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser BG. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Vol. 2. Mill Valley, CA, USA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiovitti RF, Piran N. Rigour and grounded theory research. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(4):427–435. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Canada . Canada’s Food Guide to Healthy Eating. Ottawa, Canada: Minister of Public Works and Government Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renzaho AMN. Fat, rich and beautiful: changing socio-cultural paradigms associated with obesity risk, nutritional status and refugee children from sub-Saharan Africa. Health Place. 2004;10(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(03)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadley C, Patil CL, Nahayo D. Difficulty in the food environment and the experience of food insecurity among refugees resettled in the United States. Ecol Food Nutr. 2010;49(5):390–407. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2010.507440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burns C. Effect of migration on food habits of Somali women living as refugees in Australia. Ecol Food Nutr. 2004;43(3):213–229. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patil CL, Hadley C, Nahayo PD. Unpacking dietary acculturation among new Americans: results from formative research with African refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(5):342–358. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9120-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ainsworth P. Refugee Diet in a Context of Urban Displacement Part One: Some Notes on the Food Consumption of Southern Sudanese Refugees Living in Cairo. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo, Forced Migration and Refugee Studies Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renzaho AMN, Burns C. Post-migration food habits of sub-Saharan African migrants in Victoria: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Diet. 2006;63(2):91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simich L, Hamilton H, Baya BK. Mental distress, economic hardship and expectations of life in Canada among Sudanese newcomers. Transcult Psychiatry. 2006;43(3):418–444. doi: 10.1177/1363461506066985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laverentz M, Cox C, Jordan M. The Nuer Nutrition Education Program: breaking down cultural barriers. Health Care Women Int. 1999;20(6):593–601. doi: 10.1080/073993399245485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants . Healthy Eating, Healthy Living: A Nutrition Education Flipchart. Washington, DC, USA: US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants Food and Nutrition Outreach for Newly Arrived Refugees; 2006. [Accessed April 10, 2013]. Available from: http://www.uscrirefugees.org/2010Website/5_Resources/5_1_For_Refugees_Immigrants/5_1_1_Health/5_1_1_2_Nutrition/Healthy_Eating_Flip_Chart.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willis M, Nkwocha O. Health and related factors for Sudanese refugees in Nebraska. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(1):19–33. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-6339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Health Canada . Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. Ottawa, Canada: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Health Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hargreaves MK, Schlundt DG, Buchowski MS. Contextual factors influencing the eating behaviours of African American women: a focus group investigation. Ethn Health. 2002;7(3):133–147. doi: 10.1080/1355785022000041980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]