Abstract

Background

Well-differentiated thyroid cancer (WDTC) is a prevalent disease, which is increasing in incidence faster than any other cancer. Substantial direct medical care costs are related to the diagnosis and treatment of newly diagnosed patients as well as the ongoing surveillance of patients who have a long life expectancy. Prior analyses of the aggregate healthcare costs attributable to WDTC in the U.S. have not been reported.

Methods

A stacked cohort cost analysis was performed on the U.S. population from 1985-2013 to estimate the number of WDTC survivors in 2013. Incidence rates, cancer-specific, and overall survival were based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data. We then estimated current and projected direct medical care costs attributable to the care of WDTC patients. Health-care related costs and event probabilities were based on Medicare reimbursement schedules and the literature.

Results

Estimated overall societal cost of WDTC care in 2013 for all U.S. patients diagnosed after 1985 is $1.6 billion. Diagnosis, surgery, and adjuvant therapy for newly diagnosed patients (41%) constitutes the greatest proportion of costs, followed by surveillance of survivors (37%) and non-operative deaths costs attributable to thyroid cancer care (22%). Projected 2030 costs (in 2013 $US) based on current incidence trends exceed $3.5 billion.

Conclusion

Healthcare costs of WDTC are substantial. Unlike other cancers, the majority of the cost is incurred in the initial and continuing phases of care. With the projected increasing incidence, population, and survival trends, costs will continue to escalate.

Keywords: Cost analysis, thyroid cancer, economic analysis, cost of cancer care

Introduction

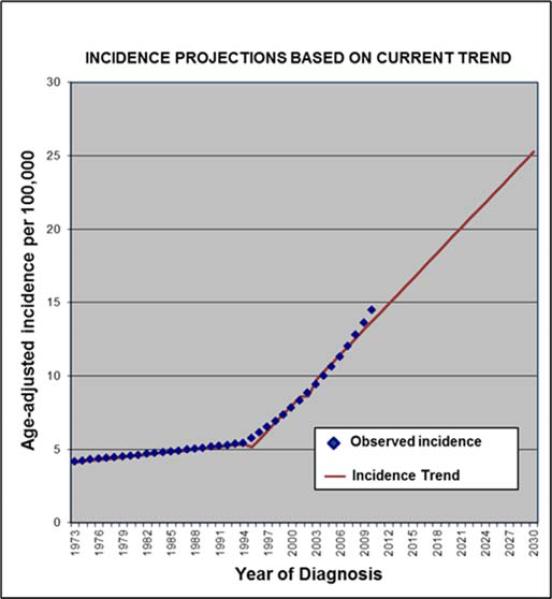

Thyroid cancer is a common disease whose incidence is increasing by 6.6% annually in the U.S., which is more than any other cancer.1, 2 Since 1973, the annual incidence has increased over 500%. It is estimated that 60,220 new cases of thyroid cancer will be diagnosed in 2013 and that it is the fifth most common cancer diagnosed among women.2 There are more than 530,000 thyroid cancer survivors living in the U.S. today.3-8 80% of new thyroid cancer patients are < 65 years of age and the 20-year disease-specific survival is more than 90%. Given these data and the aging trends in the population, it is likely that the prevalence of thyroid cancer will continue to rise.5, 9, 10

The current and projected costs of caring for patients with other cancers in the U.S. are substantial, with overall cancer care costs estimated at $157 billion in 2010.11 Prior research has shown that the majority of these cancer care costs are related to the beginning and end of care, with a relatively lower cost of continuing care.11-13 Given the unique trends in incidence and survival in the majority of patients with thyroid cancer, we hypothesized that thyroid cancer costs would have a different pattern.

Well-differentiated thyroid cancer (papillary thyroid carcinoma, follicular thyroid carcinoma and Hurthle cell thyroid carcinoma) makes up about 95% of all thyroid cancers. Our aim was to determine current and projected health-care related costs attributable to well-differentiated thyroid cancer (WDTC) care. To our knowledge, the aggregate national cost of WDTC care has not been reported. Given resource constraints, costs of thyroid cancer care may have important policy implications. Therefore, understanding these costs is essential for performance of future comparative effectiveness analyses.

Methods

Patient Population

Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) *Stat Version 8.0.4 and observed gender-specific rates for incidence, death from WDTC, and survival with WDTC, we estimated the prevalence of WDTC patients in the U.S. in 2013.2 We excluded patients with anaplastic and medullary thyroid carcinomas given the distinctive natural history, treatment, and costs of these rare more aggressive subtypes of thyroid cancer. We included papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMC, AJCC/UICC TNM T1a), as, in practice, >99% of PTMC reported in SEER undergo surgery for their disease, purporting the same costs as PTC > 1 cm. Moreover, PTMC's do exhibit aggressive behavior and metastasize.14 Next, we used observed all cause survival for included patients - an estimate of the probability of surviving all causes of death from 1985-2010 (survival estimates from SEER assume that the general population dies of competing causes at the same rate as WDTC patients) and cause-specific survival conditional on year of diagnosis to identify the number of WDTC related deaths in 2013.2

Data Sources

WDTC incidence, disease-specific survival, and all-cause mortality were obtained from the SEER registry research data from patients diagnosed from 1985-2010 based on cancer site and histological type, sex, and year of diagnosis. The SEER program is comprised of 18 cancer registries that collect data on approximately 28% of the U.S. population.2 U.S. annual population data were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau.15 SEER annual incidence rates were then multiplied by U.S. Census Bureau estimates to approximate yearly incident cases.

Clinical care practices were based on American Thyroid Association (ATA) guideline recommendations, reported practice patterns within the appropriate literature, and the expert opinion of one of the authors (G.H.D).16-19 For the base-case analysis, patients were assumed to present for an initial consult with an endocrinologist, have a diagnostic fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) under ultrasound guidance, and undergo a total thyroidectomy as per standard of care. Rates of adjuvant radioactive iodine (RAI) as well as the proportion of patients receiving recombinant thyroid stimulating hormone (rTSH) (versus thyroid hormone withdrawal) in preparation for RAI were abstracted from reported clinical practice patterns in the literature (Table 1).17, 20, 21 Data sources used for rates of tumor recurrence, surgical deaths, and surgical complications are outlined in Table 1. Hypoparathyroidism and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury were defined as temporary when symptoms lasted less than six-months following surgery, according to convention (Table 2). Patients were assumed to have two follow-up visits within the first year consisting of serum thyroglobulin and TSH tests and neck ultrasound, and once per year thereafter. Those with a local recurrence were assumed to undergo repeat FNA for confirmation and additional surgery. The cost of surgical deaths from thyroidectomy were estimated from the National Inpatient Sample by Vashishta et al. and converted to an estimated cost using the 2011 cost-to-charge ratio for short stay by Diagnosis Related Group for complicated thyroidectomy.22-24 Costs attributable to WDTC care do not differ significantly by age at diagnosis or current age, but by length of time with the disease and phase of care. A conservative cost of WDTC (non-operative) death was used in the base-case analysis based on lowest cost estimates from other solid tumors and cost of advanced thyroid cancer in the literature.11, 25 For consistency with prior cost of cancer care studies, we also define phases of care as initial (within the first year following diagnosis), continuing, and last year of life.11-13 As the majority of thyroid cancer tumor recurrences occur within five-years of initial diagnosis, when estimating recurrence costs for patients in 2013, we accounted only for tumor-recurrence related costs for patients diagnosed after 2009.26-28

Table 1.

Input parameters and probabilities for base case analysis.

| Input parameters | Data (Sensitivity Analysis Range) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients worked up with diagnostic thyroid scan | 0.05 | G.H.D. |

| Rate of tumor recurrence per year | 0.0211 (0.010-0.033) | 26, 28, 38 |

| Average operative time for thyroidectomy (15 minute intervals) | 8.2 | 39-41 |

| Proportion of patients undergoing repeat FNA | 0.1 | 42, 43 |

| Proportion of patients undergoing PET/CT | 0.025 | 16 |

| Proportion of patients undergoing CT | 0.025 | 16 |

| Proportion of patients receiving RAI | 0.56 (0.27-0.89) | 17 |

| Proportion of patients using recombinant TSH | 0.45 (0.23-0.68) | 20, 21 |

| Probabilities of surgical complications | ||

| Surgical mortality | 0.003 (0.001-0.006) | 24, 44-47 |

| Temporary hypoparathyroidism | 0.147 (0.073-0.220) | 46, 48, 49 |

| Permanent hypoparathyroidism | 0.016 (0.014-0.019) | 46, 48, 49 |

| Neck hematoma (requiring re-exploration) | 0.008 (0.008-0.017) | 24, 46, 47 |

| Unilateral temporary vocal cord injury | 0.038 (0.009-0.069) | 46-48, 50 |

| Unilateral permanent vocal cord injury | 0.015 (0.011-0.035) | 48, 50-52 |

| Bilateral vocal cord paresis/injury | 0.003 (0.001-0.015) | 24, 46, 47, 50, 51 |

FNA – Fine-needle aspiration; RAI - radioactive iodine.

Table 2.

Base case cost estimates.

| Diagnosis & Surgical treatment | HCPCS/DRG/APC | Cost in 2013 US$23 (Sensitivity Analysis Range) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial primary care provider visit | 99214 | $96.96 |

| Diagnostic thyroid scan | 78012; 389 | $197.05 |

| TSH level | 84443 | $23.10 |

| Initial endocrinology consultation | 99204 | $128.48 |

| Neck ultrasound | 76536 | $124.86 |

| FNA (US-guided) | 76942; 10022; 88173 | $465.56 |

| Endocrinology follow-up visit | 99214 | $96.96 |

| Initial surgical consultation | 99204 | $128.48 |

| Thyroidectomy for malignancy (Surgeon) | 60252 | $1,332.00 |

| Thyroidectomy for malignancy (Anesthesia) | 320 | $1,078.68 |

| Hospital | 627 | $4,404.13 |

| Radioactive iodine (I131) treatment (rTSH) | ||

| Endocrinology visits (3) | 99213 | $221.04 |

| Thyrogen injection (Day 1 + Day 2) | J3240 | $2,103.80 |

| TSH levels (pre- and post-treatment) | 84443 | $46.20 |

| Tg + TgAb (pre/unstimulated + post/stimulated) | 84432; 86800 | $87.88 |

| Urine pregnancy test | 81025 | $8.70 |

| Dose of radioactive iodine (per 100mci) | A9530 | $1,123.00 |

| Thyroid scan - whole body | 78018 | $300.09 |

| Radioactive iodine (I131) treatment (thyroid hormone withdrawal) | ||

| Endocrinology visits (3) | 99213 | $221.04 |

| Diagnostic dose of radioactive iodine (2 uCi) | J3240 | $22.46 |

| TSH levels (pre- and post-treatment) | 84443 | $46.20 |

| Tg + TgAb (pre/unstimulated + post/stimulated) | 84432; 86800 | $87.88 |

| Urine pregnancy test | 81025 | $8.70 |

| Therapeutic dose of radioactive iodine (100 uCi) | A9530 | $1,123.00 |

| Thyroid scan - whole body | 78018 | $300.09 |

| Surveillance | ||

| Thyroid scan - whole body | 78018; 406 | $300.09 |

| Tg + TgAb levels | 84432, 86800 | $43.94 |

| TSH level | 84443 | $23.10 |

| Neck ultrasound | 76536 | $124.86 |

| Surgery follow-up visit | 99214 | $96.96 |

| Endocrinology follow-up visit | 99214 | $96.96 |

| Levothyroxine (per year) | Micromedex® REDBOOK® | $100.80 |

| PET/CT Neck & Chest | 308 | $1,149.00 |

| CT Neck & Chest | 8006 | $808.60 |

| Diagnosis & treatment of recurrence | ||

| Surgery follow-up visit | 99215 | $107.85 |

| Endocrinology follow-up visit | 99215 | $107.85 |

| FNA (US-guided) | 76942; 10022; 88173 | $465.56 |

| Neck dissection for malignancy (surgeon) | 38724 | $1,475.24 |

| Neck dissection for malignancy (anesthesia) | 320 | $1,578.55 |

| Hospital | 130 | $6,925.76 |

| Repeat RAI | (see above) | $4,252.25 ($2,126-$6,378) |

| Death from cancer | Mariotto et al11; Berger et al25 | $95,000.00 ($47,500, $142,500) |

| Surgical deaths & complications | ||

| Surgical mortality | 625 | $43,771.00 ($21,886-$65,657) |

| Temporary hypoparathyroidism | 82310; 83970 | $785.16 |

| Permanent hypoparathyroidism | 82310; 83970 | $1,485.22 |

| Hematoma (requiring re-exploration) | 22010; 00300 | $5,790.24 |

| Unilateral, temporary recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | 31571; 00320 | $2,224.24 |

| Unilateral, permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | 31595; 130 | $6,623.08 |

| Bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | 31600; 011 | $27,874.28 |

Physician and facility costs specific for WDTC care were estimated from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), Diagnosis Related Group (DRG), and/or Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) as appropriate using Medicare national reimbursement data for 2012-2013 (Table 2). 23 Anesthesiology fees were based on average anesthesia time (15 minute increments), 2013 HCPCS Anesthesia Base Units, and the 2013 national anesthesia conversion factor (21.9243).23 Average wholesale drug prices were obtained from the RED BOOK® on-line via Mircromedex®2 (Truven Health Analytics, Greenwood Village, Colorado). All costs are measured in 2013 U.S. dollars. The costs attributed to WDTC survivors alive in 2013 and the costs of diagnosis and treatment of newly diagnosed and recurrent WDTC patients in 2013 were analyzed. We assumed patient time costs and productivity loss to be negligible and therefore were not included. Only costs associated with malignancy (i.e., not biopsies for thyroid nodules found to be benign) were included.

Projected WDTC prevalence and cost estimates

WDTC incidence for years beyond available SEER data (2010) was extrapolated by continuing increasing, linear incidence trends based on Joinpoint regression analysis extrapolation (Joinpoint Regression Program v4.0.4.).29, 30 Numbers of incident cases in the U.S. population were estimated by the product of U.S. population forecasts by sex as projected by the U.S. Census Bureau and the projected incidence rates. All-cause death rates by age were estimated using the Berkeley Mortality Database life tables.31, 32 All costs, including projected costs, were estimated for a single year, 2013, and were therefore not discounted. Given the relatively stable survival over the study period, survival was not varied in projected estimates.

Sensitivity analyses

Given variation in clinical practice, we assessed the effect on cost of a broad range of input values. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the stability of results to uncertainty surrounding key parameters, including recurrence rates, surgical complication rates, and costs of surgical and cancer deaths. We assessed reported ranges when available or 0.5 - 1.5 times the base-case estimate when ranges were unavailable (Tables 1 & 2).

Results

WDTC incidence, prevalence, and survival

After accounting for deaths from other causes, there are an estimated 670,687 individuals in the U.S. today who were diagnosed with WDTC from 1985-2013. These individuals continue to require treatment or surveillance for their disease. Of these individuals 76% are women. The observed overall survival is worse for men with WDTC (Table 3).2 In the base-case analysis, we estimate 2,173 women and 1,522 men will die of WDTC in 2013.

Table 3.

Well Differentiated Thyroid Cancer survivors by gender and year of diagnosis.

| Men | Women | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year diagnosed | Incidence | Alive in 2013 | % | Incidence | Alive in 2013 | % | Incidence | Alive in 2013 | % |

| 1985 | 3,573 | 1,815 | 0.51 | 8,651 | 5,931 | 0.69 | 12,224 | 7,746 | 0.63 |

| 1990 | 3,557 | 1,999 | 0.56 | 10,172 | 7,707 | 0.76 | 13,729 | 9,707 | 0.71 |

| 1995 | 4,318 | 3,009 | 0.70 | 12,079 | 9,666 | 0.80 | 16,397 | 12,675 | 0.77 |

| 2000 | 5,556 | 4,450 | 0.80 | 15,917 | 14,027 | 0.88 | 21,473 | 18,477 | 0.86 |

| 2005 | 8,387 | 7,234 | 0.86 | 23,829 | 21,707 | 0.91 | 32,216 | 28,941 | 0.90 |

| 2010 | 11,570 | 10,820 | 0.94 | 36,372 | 35,409 | 0.97 | 47,942 | 46,229 | 0.96 |

| 2013 | 14,911 | 14,911 | 1.00 | 45,310 | 45,310 | 1.00 | 60,221 | 60,221 | 1.00 |

| Prevalence | 158,025 | 512,662 | 670,687 | ||||||

Estimated 2013 health-care related costs associated with treatment of thyroid cancer

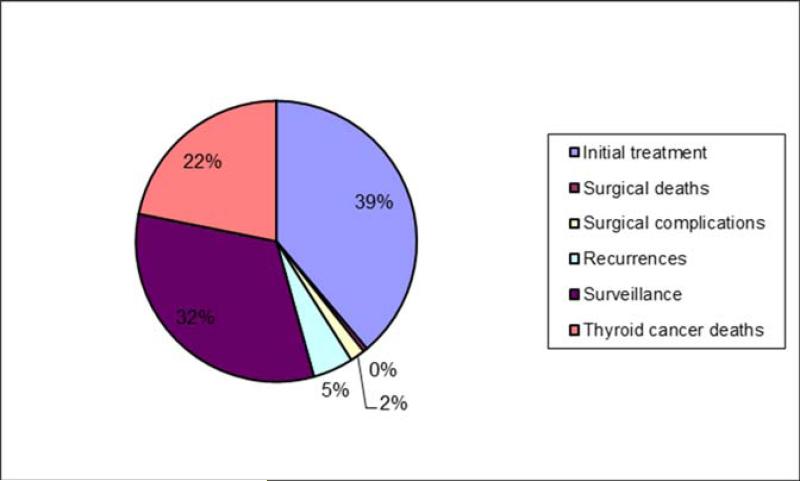

The total estimated 2013 costs associated with WDTC care exceed $1.6 billion. Initial treatment, including work-up, surgery, and adjuvant radioactive iodine (RAI) (proportional to reported practice patterns) ($658 million, 41% of costs) and continuing phases ($595 million, 37% of costs) constituted the great majority of total cost (Table 4, Figure 1). The 3,695 WDTC 2013 deaths are estimated to cost $351 million. Although men comprise 24% of the total WDTC population, 28% of the costs are attributed to their care, perhaps reflecting the lower disease-specific survival in men and increased proportion of costs attributable to thyroid cancer deaths.2

Table 4.

Current cost by phase of care and gender in 2013.

| Cost category | Men | % of cost | Women | % of cost | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial phase | $658,578,574 | ||||

| Initial treatment | $154,348,783 | 25% | $469,019,069 | 75% | $623,367,851 |

| Surgical deaths | $1,958,008 | 12% | $5,949,792 | 38% | $7,907,800 |

| Surgical complications | $6,760,863 | 30% | $20,542,059 | 92% | $27,302,922 |

| Continuing phase | $595,188,730 | ||||

| Recurrences | $17,877,008 | 24% | $56,800,695 | 76% | $74,677,703 |

| Surveillance | $122,112,902 | 23% | $398,398,125 | 77% | $520,511,027 |

| End of life phase | $351,011,185 | ||||

| Thyroid cancer deaths | $144,589,839 | 41% | $206,421,345 | 59% | $351,011,185 |

| $447,647,403 | 28% | $1,157,131,086 | 72% | $1,604,778,489 |

Figure 1.

Proportion of costs by phase of care for both sexes.

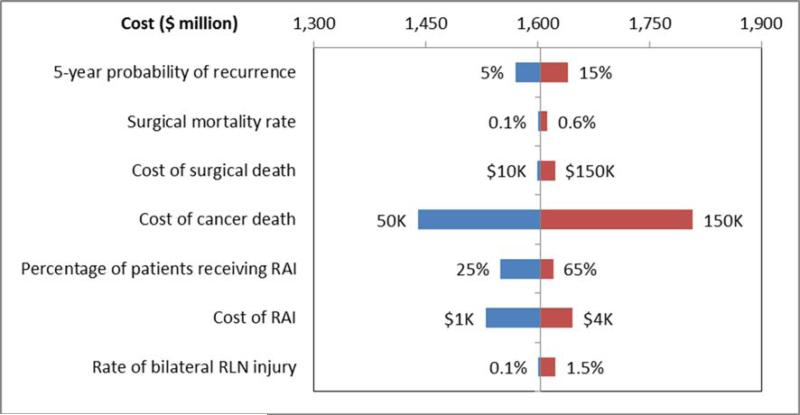

Sensitivity analysis of key input parameters

Overall, estimated costs remained stable across a reasonable range of input values. The tornado plot (Figure 2) illustrates that overall costs do not change significantly when ranges of surgical morbidities and mortality are tested over a broad range of inputs. Given the changing practice patterns and recent evidence that RAI does not benefit survival outcomes in Stage I patients and observance of the risks of RAI, it was important to show the minimal impact on cost of decreasing use of RAI in practice.33 Varying cost of cancer death had the greatest impact on total costs; but as is shown, even with decreasing the cost of cancer death to half of the cost of similar cancer deaths reported in the literature, annual costs still exceed $1.4 billion. Surgical morbidity and mortality had minimal impact on the overall attributable cost over extensive ranges of complication rates.

Figure 2.

Tornado plot assessing changes in cost over ranges of uncertain parameters. RAI – radioactive iodine. RLN – recurrent laryngeal nerve, innervation to vocal folds.

Projected 2030 thyroid cancer incidence and cost

Joinpoint regression analysis indicates a significant change in the rate of increase in annual incidence for patients with WDTC in 1994 (Figure 3). After adjusting for projected all-cause mortality in the population, we estimate a prevalence of 393,730 male and 1,251,705 female thyroid cancer patients in 2030, more than double current survivorship. The total projected 2013 costs, assuming stable thyroid-cancer specific survival and thyroid-cancer related costs, exceeds $3.55 billion (2013 $US). Proportion of costs of attributable to initial treatment is predicted to decrease to 27%; with end-of-life treatment making up a greater relative proportion (34%) (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Joinpoint regression analysis model to estimate projected incident cases through 2030 assuming recent trends.29, 30

Table 5.

Projected cost by phase of care and gender in 2030 (in 2013 $US).

| Cost category | Men | % of cost | Women | % of cost | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial phase | $946,414,420 | ||||

| Initial treatment | $220,478,729 | 0.24 | $687,099,459 | 0.76 | $907,578,188 |

| Surgical deaths | $2,796,907 | 0.24 | $8,736,403 | 0.76 | $11,533,310 |

| Surgical complications | $6,760,863 | 0.25 | $20,542,059 | 0.75 | $27,302,922 |

| Continuing phase | $1,396,858,095 | ||||

| Recurrences | $30,239,942 | 0.24 | $93,636,264 | 0.76 | $123,876,207 |

| Surveillance | $303,299,314 | 0.24 | $969,682,575 | 0.76 | $1,272,981,889 |

| End of life phase | $1,199,778,026 | ||||

| Thyroid cancer deaths | $561,065,237 | 0.47 | $638,712,789 | 0.53 | $1,199,778,026 |

| $1,124,640,992 | 0.32 | $2,418,409,549 | 0.68 | $3,543,050,541 |

Discussion

The incidence of well-differentiated thyroid cancer has increased more than any other cancer over the past four decades while survival has remained relatively unchanged (>90% 20-year survival).2, 34 Over-diagnosis likely accounts for much of this increased incidence, given that smaller papillary thyroid carcinomas account for much of the increased incidence.4, 6 Regardless, the increased rate of diagnosis in addition to an aging population results in an increase in the number of WDTC survivors and their associated cost of care.

In our analysis, we estimate the aggregate national cost of WDTC care in 2013 to be $1.6 billion dollars. This estimate was stable with respect to a wide range of input parameters. Compared to estimates of site-specific costs of cancer care in 2010, this amount is comparable to the cost of other solid tumors such as cervical, gastric, and esophageal cancer.11 The cost of initial diagnosis and treatment comprises the highest percentage of cost in WDTC as it is in most other cancers. However, unlike other reported distributions of costs of cancer care, the “last year of life phase” in thyroid makes up a smaller proportion (22%) of total cost, compared to 60-70% of costs for other cancers.11 This is undoubtedly due to the fact that most WDTC patients die of other, unrelated causes, rather than from their malignancy. The distinct cost distribution is an important consideration in cost-containment and quality improvement strategies. In contrast to the majority of other cancers, assessing the effectiveness of diagnostic, treatment, and surveillance strategies that comprise 78% of annual WDTC costs will be essential. It is important to note that the costs represented in this study include exclusively patients with a definitive diagnosis of cancer – only a portion of patients that undergo diagnostic work-up of thyroid nodules. In a recent meta-analysis of over 25,000 pooled fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies only 5.4% of FNA's were found to be malignant, and of the 25% of patients that went on to have surgery for indeterminate cytology (i.e. requiring surgery for diagnosis) only 34% were malignant on histology.35

Current clinical practice guidelines for WDTC patients are largely based on retrospective data and expert opinion, with few data available from large scale randomized controlled trials. Although there are many potential reasons for the absence of these trials, the net result is that the comparative risks and value of many of our interventions are not well documented. Moreover, the magnitude of over-diagnosis and the consequence and costs of over-treatment of WDTC have not been evaluated but are likely substantial.34 Estimating the cost of care for WDTC is an important initial step before performing comparative effectiveness research to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of our current therapies.

This analysis has a number of limitations. Due to the limited clinical trial data to inform our input parameters, we used simplifying assumptions to model complex disease processes, varying clinical practice preference, and care pathways. Indeed, it has been shown that practice variations exist among physicians treating thyroid cancer patients.18 We addressed this limitation using sensitivity analysis for key input parameters (Figure 2). Estimates of thyroid cancer incidence and prevalence were based on SEER-18 areas and not the entire U.S. population, and geographic variations in costs may exist. We are not able to discern from the SEER database if PTMC were found incidentally during thyroidectomy for benign disease or if the PTMC was indication for surgery and, therefore, may have overestimated the costs of pre-operative cost of cancer diagnosis in this subset of patients. While we did include a conservative cost of thyroid cancer deaths, we did not include the present value of future deaths from other causes. Given that we used observed survival with WDTC (including deaths from other causes) for available time points (i.e. until 2010) and the relatively low mortality from WDTC, we feel that it was reasonable to omit this variable. Lastly, given the inaccuracies in projecting fluctuations, usually increases, in medical care costs above inflation, and/or potentially more effective, but more expensive innovations, we chose to report projected costs in 2013 US dollars by assuming stable treatment technologies and unit costs. While recent reports indicate a deceleration in health-care costs, health-care inflation still exceeds average inflation in the U.S. economy.36, 37 Therefore, our projections are likely an underestimate compared to inflation-adjusted projected costs in 2030.

Given the relatively low disease-specific mortality of WDTC patients, WDTC is frequently not considered a “relevant” cancer. This is underscored by the fact that thyroid cancer has been omitted from cost-of-cancer-care analyses to date. This analysis illustrates that the care of patients with WDTC has significant economic and societal impact. The increasing prevalence and cost make it essential that we identify appropriate and effective strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of WDTC patients. Specifically, we hope that these findings provide the groundwork and focus for future research including improved risk-stratification and comparative-effectiveness research.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Program in Cancer Outcomes Research Training Grant (NCI R25CA092203), Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery, & Massachusetts General Hospital American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . In: Cancer Facts & Figures. Society AC, editor. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/ [accessed April, 2013]

- 3.Cheng SY, Ringel MD. Frontiers in thyroid cancer: December 2009. Thyroid. 2009;19(12):1297–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2164–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thyroid Cancer. Available from URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/thyroid [accessed April 20, 2012.

- 6.Chen AY, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increasing incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States, 1988-2005. Cancer. 2009;115(16):3801–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enewold L, Zhu K, Ron E, et al. Rising thyroid cancer incidence in the United States by demographic and tumor characteristics, 1980-2005. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(3):784–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Cancer Society . In: Cancer Facts & Figures. Society AC, editor. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders LE, Cady B. Differentiated thyroid cancer: reexamination of risk groups and outcome of treatment. Arch Surg. 1998;133(4):419–25. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay ID, Bergstralh EJ, Goellner JR, Ebersold JR, Grant CS. Predicting outcome in papillary thyroid carcinoma: development of a reliable prognostic scoring system in a cohort of 1779 patients surgically treated at one institution during 1940 through 1989. Surgery. 1993;114(6):1050–7. discussion 57-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yabroff KR, Mariotto AB, Feuer E, Brown ML. Projections of the costs associated with colorectal cancer care in the United States, 2000-2020. Health Econ. 2008;17(8):947–59. doi: 10.1002/hec.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown ML, Riley GF, Potosky AL, Etzioni RD. Obtaining long-term disease specific costs of care: application to Medicare enrollees diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1249–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuo EJ, Goffredo P, Sosa JA, Roman SA. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma are associated with extrathyroidal spread and lymph-node metastases: a population-level analysis. Thyroid. 2013;23(10):1305–11. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Commerce USDo . United States Census Bureau; [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167–214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Stewart AK, Koenig RJ, Birkmeyer JD, Griggs JJ. Use of radioactive iodine for thyroid cancer. JAMA. 2011;306(7):721–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, et al. Variation in the management of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2001–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuttle RM, Tala H, Shah J, et al. Estimating risk of recurrence in differentiated thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine remnant ablation: using response to therapy variables to modify the initial risk estimates predicted by the new American Thyroid Association staging system. Thyroid. 2010;20(12):1341–9. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hugo J, Robenshtok E, Grewal R, Larson S, Tuttle RM. Recombinant human thyroid stimulating hormone-assisted radioactive iodine remnant ablation in thyroid cancer patients at intermediate to high risk of recurrence. Thyroid. 2012;22(10):1007–15. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nixon IJ, Patel SG, Palmer FL, et al. Selective use of radioactive iodine in intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(12):1141–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Available from URL: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisover.

- 23.Medicare reimbursement schedule. Available from URL: www.cms.hhs.gov/ [accessed November 15, 2011.

- 24.Vashishta R, Mahalingam-Dhingra A, Lander L, Shin EJ, Shah RK. Thyroidectomy outcomes: a national perspective. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147(6):1027–34. doi: 10.1177/0194599812454401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger AE, Chung J, Ngyuyen K, A, Stepan D, Oster G. Healthcare (HC) utilization and costs in patients (pts) with newly diagnosed metastatic thyroid cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hay ID, Thompson GB, Grant CS, et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma managed at the Mayo Clinic during six decades (1940-1999): temporal trends in initial therapy and long-term outcome in 2444 consecutively treated patients. World J Surg. 2002;26(8):879–85. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HJ, Sohn SY, Jang HW, Kim SW, Chung JH. Multifocality, but not bilaterality, is a predictor of disease recurrence/persistence of papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg. 2013;37(2):376–84. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prescott JD, Sadow PM, Hodin RA, et al. BRAF V600E status adds incremental value to current risk classification systems in predicting papillary thyroid carcinoma recurrence. Surgery. 2012;152(6):984–90. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 4.0.4) Available from URL: http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/

- 30.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Department of Commerce . United States Census Bureau.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell FC, Wade AH, Goss SC. Security S, editor. Life Tables for the United States Social Security Area. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonklaas J, Sarlis NJ, Litofsky D, et al. Outcomes of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma following initial therapy. Thyroid. 2006;16(12):1229–42. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):605–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bongiovanni M, Spitale A, Faquin WC, Mazzucchelli L, Baloch ZW. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: a meta-analysis. Acta Cytol. 2012;56(4):333–9. doi: 10.1159/000339959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medical Cost Trend: Behind the Numbers. 2014 Available from URL: http://www.pwc.com/en_US/us/health-industries/behind-the-numbers/assets/medical-cost-trend-behind-the-numbers-2014.pdf.

- 37.Economic Projections of the Federal Reseve. Available from URL: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130619.pdf 2013]

- 38.Ito Y, Kudo T, Kobayashi K, Miya A, Ichihara K, Miyauchi A. Prognostic factors for recurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma in the lymph nodes, lung, and bone: analysis of 5,768 patients with average 10-year follow-up. World J Surg. 2012;36(6):1274–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldfarb M, Perry Z, R AH, Parangi S. Medical and surgical risks in thyroid surgery: lessons from the NSQIP. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(13):3551–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1938-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim H, Choi SH, Choi YS, Lee JH, Kim NO, Lee JR. Comparison of the antitussive effect of remifentanil during recovery from propofol and sevoflurane anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(7):765–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollei TR, Barrs DM, Hinni ML, Bansberg SF, Walter LC. Operative Time and Cost of Resident Surgical Experience: Effect of Instituting an Otolaryngology Residency Program. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0194599813482291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crowe A, Linder A, Hameed O, et al. The impact of implementation of the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology on the quality of reporting, “risk” of malignancy, surgical rate, and rate of frozen sections requested for thyroid lesions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011;119(5):315–21. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baloch ZW, Cibas ES, Clark DP, et al. The National Cancer Institute Thyroid fine needle aspiration state of the science conference: a summation. Cytojournal. 2008;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta PK, Smith RB, Gupta H, Forse RA, Fang X, Lydiatt WM. Outcomes after thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy. Head Neck. 2012;34(4):477–84. doi: 10.1002/hed.21757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loyo M, Tufano RP, Gourin CG. National trends in thyroid surgery and the effect of volume on short-term outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(8):2056–63. doi: 10.1002/lary.23923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrime MG, Goldstein DP, Seaberg RM, et al. Cost-effective management of low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(12):1245–53. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.12.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhattacharyya N, Fried MP. Assessment of the morbidity and complications of total thyroidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(4):389–92. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shan CX, Zhang W, Jiang DZ, Zheng XM, Liu S, Qiu M. Routine central neck dissection in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(4):797–804. doi: 10.1002/lary.22162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomusch O, Machens A, Sekulla C, Ukkat J, Brauckhoff M, Dralle H. The impact of surgical technique on postoperative hypoparathyroidism in bilateral thyroid surgery: a multivariate analysis of 5846 consecutive patients. Surgery. 2003;133(2):180–5. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barczynski M, Konturek A, Pragacz K, Papier A, Stopa M, Nowak W. Intraoperative Nerve Monitoring Can Reduce Prevalence of Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury in Thyroid Reoperations: Results of a Retrospective Cohort Study. World J Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2260-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Misiolek M, Waler J, Namyslowski G, Kucharzewski M, Podwinski A, Czecior E. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroid cancer surgery: a laryngological and surgical problem. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258(9):460–2. doi: 10.1007/s004050100370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hermann M, Alk G, Roka R, Glaser K, Freissmuth M. Laryngeal recurrent nerve injury in surgery for benign thyroid diseases: effect of nerve dissection and impact of individual surgeon in more than 27,000 nerves at risk. Ann Surg. 2002;235(2):261–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200202000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]