Abstract

Background

Meeting potential sexual/romantic partners for mutual pleasure is one of the main reasons young adults go to bars. However, not all sexual contacts are positive and consensual, and aggression related to sexual advances is a common experience. Sometimes such aggression is related to misperceptions in making and receiving sexual advances while other times aggression reflects intentional harassment or other sexually aggressive acts. The present study uses objective observational research to assess quantitatively gender of initiators and targets and the extent that sexual aggression involves intentional aggression by the initiator, the nature of responses by targets, and the role of third parties and intoxication.

Methods

We analyzed 258 aggressive incidents involving sexual advances observed as part of a larger study on aggression in large capacity bars and clubs, using variables collected as part of the original research (gender, intoxication, intent) and variables coded from narrative descriptions (invasiveness, persistence, targets’ responses, role of third parties). Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) analyses were used to account for nesting on incidents in evening and bars.

Results

90% of incidents involved male initiators and female targets, with almost all incidents involving intentional or probably intentional aggression. Targets mostly responded nonaggressively, usually using evasion to end the incident. Staff rarely intervened; patron third parties intervened in 21% of incidents, usually to help the target but sometimes to encourage the initiator. Initiators’ level of invasiveness was related to intoxication of the targets but not their own intoxication, suggesting intoxicated women were being targeted.

Conclusions

Sexual aggression is a major problem in bars often reflecting intentional sexual invasiveness and unwanted persistence rather than misperceptions in sexual advances. Prevention needs to focus on addressing masculinity norms of male patrons and staff that support sexual aggression and better management of the highly sexualized and sexist environments of most bars.

Keywords: environmental policy, sexual aggression, gender, prevention, barroom

Introduction

Meeting potential sexual/romantic partners for mutual pleasure is one of the main reasons young adults go to licensed premises (Cavan, 1966, Purcell and Graham, 2005). However, not all sexual and romantic contacts are positive and consensual, with aggression relating to sexual advances a common experience in bars. Aggression may be related to misperceptions (Snow et al., 1991)related to: gender differences in perceptions of sexual interest (Abbey et al., 2000); the kinds of sexual advances that are perceived as appropriate (Garlick, 1994, Rotundo et al., 2001); expectations regarding obligations to accept overtures (Ferris, 1997, Parks and Miller, 1997); and ways of communicating refusal (Wade and Critelli, 1998). Plus, how a refusal is made may affect whether aggression arises from an initially nonaggressive social overture or sexual advance. For example, the initiator of a sexual advance may react aggressively to the target’s response if he/she feels embarrassed or rejected (Berk, 1977), especially if the rejection is seen as unfair or is witnessed by the initiator’s peers (Felson, 1978). Conversely, the target may react aggressively in response to perceived inappropriate sexual contact, even when the contact was intended as a genuine overture.

Although misperceptions are one cause of sexual aggression in bars, aggression can also take the form of intentional harassment or unwanted sexual contact, usually done by men toward women, such as grabbing a woman’s breast, rubbing against a stranger on the dance floor and making comments about a woman’s body (deCrespigny et al., 2001, Parks and Miller, 1997). Such aggression may be related to the dominating role of masculine identity in public drinking settings (see Graham and Homel, 2008) related to male group bonding (Wells et al., 2011), to men asserting or defending their social identity (Graham et al., 2013) and to male attitudes toward women who drink in bars (Parks and Scheidt, 2000). Moreover, this culture is often reinforced by security staff (i.e., “bouncers”) who may do little to prevent sexual aggression because security staff culture is one of aggression and machismo (Hobbs et al., 2007) and staff may themselves engage in sexual harassment or refuse to help women because of the way that women are dressed or because they are intoxicated (deCrespigny, 2001).

Patron third parties can also play a role in aggression (Levine et al., 2011), either by escalating the incident (e.g., encouraging aggressor, joining in the conflict or intervening aggressively on the target’s behalf) or de-escalating the aggression by discouraging the aggressor or protecting the target nonaggressively (Wells and Graham, 1999). Research on third party involvement in aggression in bars has mainly been qualitative and focused on male-to-male aggression (Benson and Archer, 2002, Graham and Wells, 2003), with little known about the role of third parties in sexual aggression.

Intoxication is also likely to play a role. Initiators of a sexual advance may be less sensitive to body language and gestures intended to communicate that the overture is unwelcome when intoxicated (Abbey et al., 1998; Norris et al., 2002). Intoxicated target may be less able to communicate in a clear way that the overture is unwanted (Abbey et al., 2002) or recognize risks of sexual assault (Loiselle and Fuqua, 2007). Intoxication may also increase women’s likelihood of being targeted for sexual aggression (Ullman et al., 1999), perhaps partly because more intoxicated women are seen as being more sexually available (George et al., 1988; George et al., 1995). Consistent with this several studies have found that women were more likely to be victims of sexual aggression on occasions when they drank more (Parks et al., 2008) or were more intoxicated (Kelley-Baker et al., 2008). Less is known about the role of intoxication for persons who initiate sexual aggression in bars.

Research Objectives

Little is known about the frequency and nature of sexual aggression in bars and clubs or about how targets respond to sexual advances. Moreover, previous research on sexual aggression almost always reflects only one perspective – that of the female victim (Parks, 2000, Parks and Miller, 1997, Pino and Johnson-Johns, 2009) or that of the male perpetrator (Abbey et al., 1998; Norris et al., 2002; Thompson and Cracco, 2008). In the present analyses, we use objective observational research to assess quantitatively the extent that sexual aggression in bars involved:

male versus female initiators and targets;

intentional harassment or aggression by the initiator (such as rubbing against an unwilling stranger), including invasive contact and unwanted persistence by initiators;

aggressive and nonaggressive responses by targets of sexual advances;

intervention by staff and patron third parties; and

intoxication of initiators and targets.

We expect that most initiators will be male and most targets female. With regard to intoxication, we hypothesized that (i) intoxication of both the initiators and the targets of sexual advances will be associated with greater persistence and invasiveness by the initiator, and (ii) targets will be more likely to respond aggressively if they are intoxicated.

Method

Data were collected as part of a randomized control evaluation of a program to prevent bar violence (Graham et al., 2004), including narrative descriptions and quantitative data for 1057 incidents of aggression observed during 1334 visits to 118 large capacity bars/clubs (>300 people) in the city of Toronto, Canada during 2000–2002. A list of large capacity licensed premises provided by the licensing authority was screened to exclude ineligible premises and site visits were conducted to document line-ups, age and ethnicity of patrons, and other factors relevant to sending observers. Establishments in the study attracted patrons diverse in age (although about 75% were under 30), ethnicity and sexual orientation. About two-thirds were dance clubs while the rest were sports and other types of bars, large pubs and concert venues. Of the observed incidents, 258 (24.4%) included sexual aggression.

Procedures

Observations were conducted unobtrusively by male-female pairs of trained researcher-observers between midnight and 3:00 A.M. on Friday and Saturday nights. Observers were required to have a Bachelor’s degree or equivalent research experience, feel comfortable going to bars and pass a rigorous screening process. The 148 observers (from 250 interviewed) received about 25 hours of training and a written manual (http://publish.uwo.ca/~kgraham/observer_training_manual.doc) developed from previous observational research (Graham et al., 1980; Graham & Wells, 2001; Homel & Clark, 1994) addressing how to observe in bars, procedures for data collection, and ethical, confidentiality and safety issues.

Observers were assigned to different partners and venues each week. Observers met about 30 minutes before the observations. They were instructed to stay together and be as inconspicuous as possible by wearing appropriate clothes, finding a good location for viewing, changing locations during the visit if necessary and avoiding unnecessary contact with other patrons or staff. On-call field coordinators made spot-checks to ensure that observers were at the assigned location and behaving appropriately.

Observers were trained to spot and record possible aggression using a broad general definition of aggression used in previous observational studies (Graham et al., 1980, Homel and Clark, 1994) which included both verbal and physical aggression and took into consideration environmental norms. Observers were permitted to indicate potential aggression to partners and make notes discreetly but could not discuss observed aggression prior to completing forms and narrative descriptions which they completed independently immediately after the bar visit or first thing the next morning. These included detailed step-by-step descriptions of the aggressive incidents, including data on each participant for up to 8 patrons and 6 staff (sex, age, role in incident, level of intoxication, etc.).

Aggressive and coercive acts observed during the study varied from very minor (e.g., mild angry words, aggressive gestures and looks) to severe (e.g., punching, kicking). Incidents were selected for inclusion in the present analyses if they involved: (a) a sexual overture or sexual behavior, and (b) at least one person was judged as having probable or definite intent to harm (see measurement of intent below). Types of aggression related to sexual advances ranged from sexist statements or gestures and refusing to leave a person alone to grabbing a woman’s bum or breast or reaching up a women’s dress to a the target or a third party responding angrily or with physical aggression toward the person making the advance. Additional details about the observation methods and other aspects of the study are provided in previous publications (Graham et al., 2004, 2006).

Measures

In addition to gender, staff/patron status and whether person was initiator, target or third party, variables included: intoxication of initiators and targets, aggressive intent, level of invasiveness and persistence of aggressive sexual advances, and responses by targets. Intoxication was rated by the observers at the time of the data collection and intent to harm was defined and coded as part of previous analyses of these data. All other variables were coded by four male and three female university students who were familiar with the contemporary bar/club scene using observers’ narrative descriptions of incidents. A minimum of three coders (at least one male and one female) coded each person’s behavior with the exception of 39 (15.5%) incidents that were used for training purposes and coded collaboratively by the team. Because multiple coders were used for variables other than intoxication and intent to harm, we estimated inter-rater reliability for continuous measures as the proportion of variance that reflects true scores (the intercept variance, τ, in Hierarchical Linear Modeling analysis) rather than error (the between-coder variance, σ2, divided by the number of raters). This method follows the principles of generalizability theory (Bryk and Raudenbush, 1992, Cronbach et al., 1972) to apply the standard definition of reliability (alpha statistic) to the case of multiple raters. For dichotomous measures, we calculated the average percent agreement across pairs of coders.

Intoxication (coded previously)

The two observers independently rated level of intoxication of each participant in aggressive incidents from (0) totally sober to (9) falling down drunk (based on criteria outlined by Teplin and Lutz, 1985) [Pearson r for inter-observer agreement = .66].

Aggressive intent (coded previously)

Aggression has been defined to include intent as well as harm (Baron and Richardson, 1994). Harms from sexual aggression in bars include making the target feel uncomfortable, annoyed, afraid or violated or affecting their enjoyment by causing them to leave the situation or the premises completely (see Graham et al., 2010). The following categories were used to rate intent to harm for each person involved in incidents of aggression as part of previous analyses of these data (see Graham et al., 2006): (0) no intent (e.g., harm clearly accidental such as accidentally bumping into someone); (1) defensive intent (aggressive act involved no more force than necessary to defend oneself – e.g., pushing someone away); (2) probable intent (the harm appeared intentional but the intent might have been defensive or playful rather than aggressive); (3) definite intent (harm clearly intended and not defensive) [Spearman correlation between raters = .74, Kappa for inter-rater agreement = .58]. A person’s behavior was labeled “aggressive” if intent was rated as probable or definite.

Persistence and invasiveness by the initiator (coded as part of the present study)

Initiators were defined as the person making the initial sexual advance or overture. For initiators whose intent was rated probable or definite, two scales were developed to measure the nature of the initiator’s sexual aggression: invasiveness and persistence. All statistical analyses used the full scales for persistence and invasiveness but categories (i.e., any invasiveness or persistence) were used for describing behaviors in Table 1. The initiator’s sexual invasiveness was rated on an 11-point scale (0 – 10), with the following anchors: 0 - no contact; 1–2 – not sexual (e.g., touched person on arm, hair or other noninvasive body contact); 3–4 – contact on part of body where touch by strangers is generally unacceptable (e.g., arm around shoulder or one hand on waist); 5–6 – somewhat invasive sexual contact (e.g., both hands on waist); 7–8 – definitely invasive sexual contact (e.g., rubbing groin against person, touching crotch, breasts); 9–10 – very invasive, forceful or aggressive contact (e.g., grabbing crotch) [α for inter-rater reliability = .95]. If more than one act was rated for the initiator, the maximum invasiveness rating was used. The initiator’s aggression was defined as including invasiveness if the mean score across raters was greater than or equal to 3 (i.e., any type of contact that is generally considered unacceptable when done by a stranger) or if it was categorized as sexually suggestive or threatening. Acts that were sexually suggestive or threatening or involved harassment but no contact were coded missing on the invasiveness scale rather than zero because although they involved no physical contact, they could be considered psychologically invasive.

Table 1.

Percent of initiators whose sexual aggression involved any persistence and different levels of invasiveness and/or harassment with examples in each category

| Invasiveness/harassment | Persistent (average persistence rating > 2) | Not persistent (average persistence rating <=2) | All cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly invasive touching (average rating > = 7) | 37 (15.9%) | A man and woman were facing each other dancing. The man moved very close and firmly grabbed the woman’s behind with both hands. She immediately pushed both of his hands away. The man looked at his male friend and they both laughed. They continued dancing. About ten seconds later he grabbed her breasts. She pushed his hands away with more force then the first time. Both men laughed again. The woman went to another area of the dance floor. | 29 (12.5%) | A man slapped a woman’s behind and said he liked what he saw. She turned and shoved his chest with both hands and shouted “Don’t you ever touch my fucking ass again.” | 66 (28.4%) |

| Somewhat invasive touching (average rating > = 5 < 7) | 30 (12.9%) | A woman was with her male friends on the dance floor. A man who was not part of the group came up from behind and put his arm around her waist, pressing his body close to hers. She stopped dancing, appeared shocked and moved away from him. He moved in behind her again. She firmly grabbed his hand, pushed it off her and stepped back two steps. He said “Sorry, just needed to get by.” | 14 (6.0%) | A man was staring at each woman who walked by him. He leaned forward so his mouth was touching the hair of one woman (she gave him a dirty look). He placed one hand on the wrist and one on the stomach of another woman. She ignored him and kept walking. | 44 (19.0%) |

| Unacceptable touching (average rating > = 3 < 5) | 16 (6.9%) | A male patron came behind a female server and rested his chin on her shoulder and put his arms around her waist. She pulled away from him. He followed her trying to grab her clothes but she was moving too quickly. | 16 (6.9%) | A man joined a group of four women on the dance floor. He separately tried to put his arm around two of the women who were dancing and each pulled away. | 32 (13.8%) |

| Sexually suggestive or threatening | 23 (9.9%) | The male entertainer who was giving out prizes to women with big boobs made comments to the audience about the size of one female patron’s breasts, including, “Dear Lord! I wanted a woman with big boobs, but not that big! | 18 (7.8%) | A man yelled out, “Hey blondie, come and sit on my lap” to a woman walking by. She continued walking. | 41 (17.7% |

| General sexual harassment with no contact or non-invasive contact and nonthreatening | 26 (11.2%) | A man grabbed a woman’s arm as she was walking by and said something to her. She shook her head no, but he continued to hold her arm and say things, while she continued to shake her head no. She looked directly at the man and pulled her arm away. He finally let her go. | 21 (9.1%) | Three men were sitting at a table hollering at all of the female patrons who were passing by. The women ignored them or gave them dirty looks. | 47 (20.3%) |

| Nonaggressive | NA | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (0.9%) | ||

| Total | 132 (56.9%) | 100 (43.1%) | 232 (100%) | ||

Persistence was rated on a 10-point scale from 1 - stopped right away to 10 - relentless persistence over an extended period of time, stalking, or never gave up [α for inter-rater reliability = .93]. Criteria for persistence included the extent that sexual advances were repeated after refusal by target and the extent the initiator followed the target to different areas of the bar. The initiator’s aggression was defined as including at least some persistence if the mean score across raters was greater than or equal to 2, reflecting that the initiator did not stop when the target refused.

Targets’ responses (coded as part of the present study)

Targets were defined as the person or persons to whom the sexual advance was directed. Raters coded the number of times targets made each of the responses described below and responses were coded dichotomously (i.e., whether response occurred) [average percent agreement (PA) across rater pairs shown in brackets]:

ignored the initiator (if done as a distinct act) [PA = 88.1%]

used evasive maneuvers (e.g., pulled away from the initiator’s grasp) [PA = 79.6%]

-

used facial expressions or body language to indicate to the initiator that their actions were making the target…

annoyed [PA = 84.5%]

disgusted [PA = 90.4%]

uncomfortable or embarrassed [PA = 83.3%]

upset [PA = 78.1%]

angry [PA = 83.6%]

completely moved away from the initiator to another area of the bar or left the bar [PA = 74.5%]

indirect refusal (e.g., held up drink to show not available right now) [PA = 91.4%]

direct refusal (e.g., shook head, said “no thanks”) [PA = 88.3%]

emphatic or angry negative reaction (e.g., yelling, angry words) [PA = 91.4%]

used minor physical force (e.g., pushed initiator away) [PA = 87.5%]

used moderate-severe physical force (e.g., punched/slapped initiator) [PA = 94.1%]

other response (N = 2, shrieked in surprise, glared at the initiator’s girlfriend) [PA = 92.3%]

Ratings of targets’ responses were missing for 26 incidents in which the target’s responses were unknown or the target was unaware of the initiator’s actions (e.g., a man making motions toward a woman’s behind for the entertainment of his friends without the woman being aware that she was the target).

Third party involvement (coded as part of the present study)

Third parties were defined as people who became involved in the incident after the original sexual advance had taken place. Incidents were categorized as to whether third parties were involved, the relationship of third parties to the initiator and target (i.e., friend of initiator, friend of target, friend of both the initiator and the target, other patrons, staff), gender and whether third parties were aggressive.

Analyses

Statistical significance of relationships between variables was assessed using Hierarchical Linear Modeling v. 6.03 (HLM) (Bryk and Raudenbush, 1992) to take into account that incidents of aggression were nested in nights of observation and bars. Because the focus of these analyses was the inter-relationships of behaviors at the incident level, although visit and bar level variables are adjusted for in the present analyses, no visit or bar level variables were included as explanatory variables in these analyses. Visit and bar level variables have been examined in previous analyses of these data (Graham et al., 2006; Purcell & Graham, 2005). The analyses used 3-level HLM, β-coefficients for predictors at level 1 (incident level) were estimated using full maximum likelihood estimation for continuous distribution outcomes (initiator’s persistence, invasiveness and intoxication, and target’s level of intoxication). Odds ratios for predictors of target responses were computed using Bernoulli regression models in 3-level HLM, with predictors (persistence, invasiveness, initiator intoxication and target intoxication) entered at the incident level in bivariate models. Separate HLM models of persistence, invasiveness and intoxication predicting each target behavior were computed. HLM linear regression models were used to examine the association of persistence and invasiveness with intoxication and standardized betas reported as measures of these associations. Almost all incidents involved a single initiator and a single target; therefore, we included only one initiator and one target from each incident in our analyses (the most aggressive person; or the person described first by the observers if aggressors were equally aggressive).

Results

Overall, 89.9% of the 258 aggressive incidents related to sexual overtures or sexual advances involved male initiators and female targets, 3.5% involved female initiators and male targets, 4.3% male-to-male and 2.3% female-to-female. Because most incidents were by men toward women with too few in other gender categories for separate analyses, we limit the remaining analyses to the 232 incidents that involved male-to-female sexual aggression. All initiators and targets were patrons except for 2.2% of initiators who were entertainers employed by the bar and 6.5% of targets (all were serving staff except one entertainer). On average, initiators were rated 4.98 (SD = 2.10, range = 0 – 9.00) on the intoxication scale and targets rated 2.26 (SD = 2.30, range = 0 – 9.00).

Initiators’ behaviors

All but two initiators were defined as aggressive, with 65.1% rated as having probable aggressive intent and 34.1% rated as definite intent. Of aggressive initiators, 61.2% were rated as engaging in invasive contact (i.e., scoring 3 or higher on invasiveness, average rating of 4.81, SD = 2.48, range = 0 – 9.67) and 56.9% engaging in persistent advances following a refusal (i.e., scored two or higher on persistence (average rating of 3.63, SD = 2.30, range = 1 – 9.70). An additional 17.7% made sexually suggestive or threatening acts without physical contact and 9.1% engaged in general sexual harassment such as pestering women as they walked by. Table 1 provides examples for different types of sexual aggression by level of invasiveness and persistence.

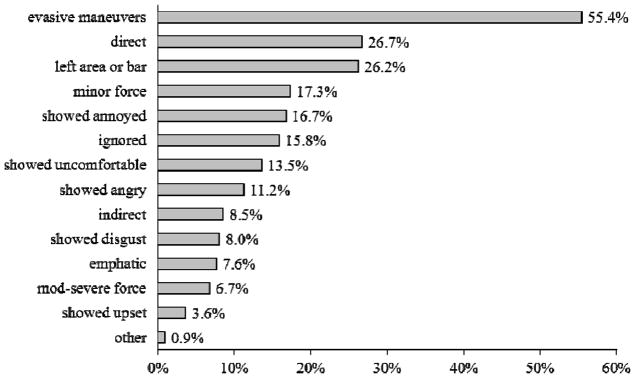

Responses by targets

On average, targets engaged in 3.55 acts (SD = 3.10, range 0 to 23) to indicate to the initiator that the overture was unwanted (including repeating the same action more than once as well as using different responses). As shown in Figure 1, the most frequent response (made by 55.4% of targets) was engaging in an evasive maneuver (e.g., pulling or edging away, stepping back). Direct responses (e.g., saying “no”) were made by 26.7% of targets and about the same proportion left the area entirely (or even the bar) in order to get away from the initiator. Other common responses (made by at least 10%) included minor force (e.g., pushing the initiator away), showing annoyance, ignoring the initiator, showing discomfort and showing anger. Moderate-severe force or aggression was used in 6.7% of cases. Only 15 targets (6.5%) were rated as having probable or definite intent, with most incidents of force or angry words rated as defensive intent (i.e., level of aggression needed to protect self).

Figure 1.

Percent of targets engaging in each type of response

Note: Not mutually exclusive

Role of staff and patron third parties

Ten incidents involved staff as third parties, with only one involving ejection of the initiator for engaging in sexual aggression. Patron third parties participated in 48 (20.8%) incidents (including 4 incidents that also involved staff third parties). Of these 12 incidents involved aggressive third parties. Third parties were friends of the target in 24 incidents (15 incidents involved female friends, 8 male friends, and 1 with both male and female friends), friends of the initiator in eight incidents (all were male friends), and friends of both the initiator and target in eight incidents. Other patrons who were not friends of either the initiator or target also became involved in eight of the 48 incidents. Friends of the target almost always intervened to protect the target by coming between the initiator and the target or by speaking to the initiator to get him to leave the target alone. Of the eight incidents in which friends of the initiator were involved, one friend apologized to the target, two discouraged the initiator, and five encouraged the initiator by joining in or acting as a supportive audience.

Relationships between the behaviors of initiators and targets and of these behaviors with intoxication

Table 2 shows the odds ratio corresponding to the target’s likelihood of engaging in each response depending on the level of persistence and invasiveness of the initiator and the intoxication level of perpetrators and targets, based on separate bivariate HLM analyses of persistence, invasiveness and intoxication predicting each target response. As shown in this table, persistence was significantly and positively associated with most responses except for annoyance, anger, upset, emphatic or angry reaction and use of moderate-severe physical force. Invasiveness was associated with the target leaving the area or the bar and using minor and moderate-severe physical force.

Table 2.

Odds ratios that targets engaged in each response predicted by initiators’ level of persistence, sexual invasiveness and intoxication, and by targets’ level of intoxication1

| Response by target | Initiator’s persistence | Initiator’s invasiveness | Initiator’s intoxication | Target’s intoxication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ignored initiator | 1.31*** | 0.88 | 1.01 | 0.75* |

| Evasive maneuvers | 1.26*** | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.02 |

| Left area or bar | 1.28** | 1.20** | 1.06 | 1.03 |

| Indirect refusal | 1.33** | 1.00 | 1.10 | 0.69** |

| Direct refusal | 1.27** | 0.95 | 1.04 | 0.97 |

| Emphatic or angry reaction | 1.17 | 1.04 | 1.10 | 1.05 |

| Minor physical force | 1.19** | 1.66*** | 1.09 | 1.27** |

| Moderate-severe physical force | 1.02 | 1.99*** | 0.96 | 1.24 |

| Used facial expression or body language to indicate she felt… | ||||

| Annoyed | 1.02 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.84 |

| Disgusted | 0.66** | 0.84 | 1.23 | 0.93 |

| Uncomfortable | 1.28*** | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| Upset | 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.78 | 1.00 |

| Angry | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 1.17* |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Each odds ratio from a separate bivariate HLM model with the score for persistence, invasiveness or intoxication as the explanatory variable predicting each target response and the response by target as the dependent variable.

As shown in Table 2, more intoxicated targets were significantly more likely to show anger and use minor or moderate-severe physical force, while less intoxicated targets were more likely to ignore the initiator and use indirect refusal. None of the responses by the targets were significantly related to the intoxication level of the initiators.

In terms of the relationship between intoxication and the initiators’ persistence and invasiveness, the initiators’ intoxication was not significantly related to their level of invasiveness (β = .12, p = .186) or persistence (β = −.02, p = .747); however, intoxication of targets was significantly related to initiators’ invasiveness (β = .22, p = .013) and approached significance for initiators’ persistence (β = .11, p = .086).

Discussion

As anticipated, about 90% of incidents involved male initiators and female targets. Sexual aggression took the form of uninvited, unwanted and invasive physical contact, persistence in the face of refusal and general sexual harassment such as cat-calling, etc. About one-third of the incidents involved intentional aggression on the part of the male initiator – that is, the initiator engaged in sexual actions that he knew were unwanted, minimally causing the target discomfort but sometimes causing more serious distress including forcing her to leave the area or bar. Aggression by the remaining two-thirds of initiators was rated as probably intentional – that is, initiators probably knew that their actions were unwanted and unwelcome by the target but they may have misperceived the situation, despite the invasiveness of the act or refusals by the target. For example, one man seemed to be genuinely surprised when the female target did not find it humorous when he grabbed her blouse and peeked down it. The predominance of probable intent ratings also reflects the culture of ambiguity that seems to sanction unwanted sexual acts as evident in the lyrics of a popular song asserting that lines are “blurred” and women “want it”2.

The ambiguity and permissiveness of the barroom environment (see Graham and Homel, 2008) also provides an ideal setting for “opportunistic offending.” As described by (Cornish and Clarke, 2003), opportunistic offenders generally conform to normative restrictions regarding appropriate social behavior but will exploit opportunities to engage in low-level offences – in this case sexual aggression, partly because they know they can get away with it. The ambiguity of the situation also allows for a “romanticized interpretation” of the man’s sexual advances (Gardner, 1995) as making an “invitation” rather than intentionally invasive or aggressive, thereby giving harassers an excuse for their behavior. Moreover, the belief that “women are already giving permission simply by dancing provocatively on the dance floor” provides self-justification for sexual aggression by men (Ronen, 2010).

The most frequent response by targets was evasion, consistent with findings from research on workplace harassment (Dansky and Kilpatrick, 1997) and unwanted engagement in sexual dancing at college parties (Ronen, 2010). Targets were rarely aggressive, and when they used force, they almost always did so defensively or toward highly invasive initiators. By contrast, persistence was associated with almost all responses by women, suggesting that although targets used a variety of strategies in response to unwanted persistence (perhaps trying alternative responses when previous ones had not worked), they did not necessarily become aggressive.

Third parties appeared to play a small role in sexual aggression, with staff rarely intervening. When friends of the target became involved, they tended to help the target evade the initiator, as found in previous research on unwanted sexual contact at parties (Ronen, 2010). Friends of the initiator, on the other hand, tended to egg him on, thus reinforcing the climate of “blurred lines.” Because of the small number of third parties who became involved, it was not possible to assess the relationship between type of third party involvement and factors such as intoxication, persistence and invasiveness. This is an important area for future research in order to better understand the social context of sexual aggression.

As hypothesized, initiators were more invasive when targets were more intoxicated and there was a similar pattern for persistence that approached significance; however, initiators’ level of invasiveness and persistence was not significantly related to their own intoxication. These findings support the interpretation that intoxicated women may be targeted for sexual aggression, possibility stemming from a perception by initiators that more intoxicated targets will be less able to resist their advances (Ullman et al., 1999) and be more available (George et al., 1988; George et al., 1995). These findings also suggest that acts of sexual aggression are intentional rather than attributable to the effects of alcohol on the initiator (e.g., alcohol making him less aware of cues from the target that his actions are unwanted). Also, as hypothesized, more forceful and aggressive responses by targets were associated with targets being more intoxicated, suggesting that more sober women choose more subtle responses to unwanted sexual advances and harassment.

Limitations

Ratings were based on observed behavior rather than self-report data. Therefore, it is possible that observers were mistaken in their assessments of whether the initiator’s behavior was unwanted. However, this source of error is likely to be minimal because incidents were identified on the basis of visible negative reactions of the targets. In fact, observations by researcher-observers are more likely to provide objective measurement of sexual aggression that is not biased by the perspective of either the target or the initiator (see Yagil et al., 2006) and so provide a useful and unbiased way of viewing sexual aggression in bars. In addition, some variables such as intoxication and aggressive intent had lower than optimal inter-rater reliability. The less than optimal agreement on intoxication could have been partly due to the environmental conditions (dark, noisy) as well as limited opportunities to observe persons before and after incidents to be able to gauge their intoxication level. The less than optimal reliability for aggressive intent may reflect individual differences in coders in the extent that perpetrators were seen as knowingly engaging in behaviors that caused harm or discomfort to the target.

Conclusions and directions for prevention

While serious efforts have been made to recognize and eliminate workplace harassment, very little has been done to address sexual harassment in drinking establishments, although such harassment remains highly prevalent and largely socially accepted. Routine activity theory provides a useful framework for developing strategies for reducing sexual harassment and aggression in bars (Fox and Sobol, 2000, Graham and Homel, 2008) and for sexual assaults generally (Mustaine and Tewsksbury, 2002). Specifically, routine activity theory proposes that an offence is more likely to occur when then there is a convergence of a likely offender, a suitable victim or target, and a lack of a capable guardian to protect the victim (Cohen and Felson, 1979). This convergence is optimized in bars given that: (1) potential offenders are likely to be attracted by the highly sexualized and permissive context of bars and the essential ambiguity of unwanted sexual overtures; (2) women are likely to be perceived as suitable, possibly even “blameworthy,” targets because they are dressed to attract sexual attention and they are drinking (deCrespigny, 2001, Parks and Scheidt, 2000, Schwartz et al., 2001, Ullman et al., 1999); and (3) staff are unlikely to act as guardians because sexual harassment and sexism are integral to bar culture (Hobbs et al., 2007).

To address the ambiguity of unwanted sexual overtures, changes are needed in cultural and bar norms about the acceptability of sexual harassment and aggression in bars and elsewhere. This can reduce both opportunistic offending as well as the suitability of women as targets. Because barroom norms are also key factors in male-to-male aggression related to male identity, honor and group bonding (Wells et al., 2011), addressing these norms would not only reduce sexual aggression toward women but could have the additional benefit of reducing male-to-male aggression in the bars. It is known that management affects workplace harassment both through formal policies and informal role models (Pryor et al., 1995); therefore, the atmosphere of harassment might be changed in a venue simply by prohibiting the most egregious or obvious forms of sexual aggression (e.g., men “grinding” on unwilling women on the dance floor, groups of men harassing women) and by stopping staff themselves from engaging in or tolerating harassment regardless of the way women are dressed or their level of intoxication. Better management of bars and changes in bar culture can ensure that perceived “blurred lines” are not an excuse for sexual aggression in bars.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (R01AA017663) as was the original research on which the paper is based (RO1 AA11505). We would like to thank Bob Saltz and Richard Felson for helpful discussions related to this paper. In addition, we are grateful to Patrick Gruggen, Michael Holder, Kayla Janes, Eric LeBlanc, Laura Olszowy, Tyler Pirie, Andrew Pulford, Michael Rooyakkers, Stephanie Weldon and Rebecca Wilson who played an important role in clarifying key constructs through their coding, comments and discussions and to Sue Steinback for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Thicke, R. (2013). Blurred Lines. Interscope Records.

Thicke, R. (2013). Blurred Lines. Interscope Records

A version of this paper was presented at the 38th Annual Meeting of the Kettil Bruun Society for Social and Epidemiological Research on Alcohol.

The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA.

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Thomson LR. Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1998;17:167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Testa M, Parks K, Norris J, Martin SE, Livingston JA, McAuslan P, Clinton AM, Kennedy CL, George WH, Cue Davis K, Martell J. How does alcohol contribute to sexual assault? Explanations from laboratory and survey data. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:575–581. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, McAuslan P. Alcohol’s effects on sexual perception. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:688–697. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RA, Richardson DR. Human aggression. 2. Plenum Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Benson D, Archer J. An ethnographic study of sources of conflict between young men in the context of the night out. Psychol Evol Gend. 2002;4:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Berk B. Face-saving at the singles dance. Soc Probl. 1977;24:530–544. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk A, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cavan S. Bar sociability. In: Cavan S, editor. Liquor license: An ethnography of a bar, Liquor license: An ethnography of a bar. Aldine; Chicago: 1966. pp. 49–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LE, Felson M. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. Am Sociol Rev. 1979;44:588–608. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish DB, Clarke RV. Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: A reply to Wortley’s critique of situational crime prevention. In: Smith M, Cornish D, editors. Theory for Practice in Situational Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 16, Theory for Practice in Situational Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Studies. Criminal Justice Press; Monsey, N.Y: 2003. pp. 41–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, Gleser GC, Nanda H, Rajaratnam N. The generalizability of behavioral measurements. Wiley; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Effects of sexual harassment in Sexual harassment. Theory, research, and treatment, Sexual harassment. In: O’Donohue W, editor. Theory, research, and treatment. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 1997. pp. 152–174. [Google Scholar]

- deCrespigny C. In: Young women, pubs and safety, in Alcohol, young persons and violence, Alcohol, young persons and violence. Williams P, editor. Australian Institute of Criminology; Canberra ACT, Australia: 2001. pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Felson RB. Aggression as impression management. Soc Psychol. 1978;41:205–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris J. Courtship, drinking and control: A qualitative analysis of women’s and men’s experiences. Contemp Drug Probl. 1997;24:667–702. [Google Scholar]

- Fox JG, Sobol JJ. Drinking patterns, social interaction, and barroom behavior: A routine activities approach. Deviant Behav. 2000;21:429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner CB. Passing by. Gender and public harassment. University of California Press; Berkley and Los Angeles, Caliifornia: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Garlick R. Male and female responses to ambiguous instructor behaviors. Sex Roles. 1994;30:135–158. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Gournic SJ, McAfee MP. Perceptions of postdrinking female sexuality: Effects of gender, beverage choice, and drink payment. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1988;18:1295–1317. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Lehman GL, Cue KL, Martinez LJ, Lopez PA, Norris J. Postdrinking sexual inferences: Evidence for linear rather than curvilinear dosage effects. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;27:630–649. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Bernards S, Osgood DW, Parks M, Abbey A, Felson RB, Saltz RF, Wells S. Apparent motives for aggression in the social context of the bar. Psych Viol. 2013;3:218–232. doi: 10.1037/a0029677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Homel R. Raising the bar: Preventing aggression in and around bars, pubs and clubs. Routledge Publishing (Taylor & Francis group); Oxford, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, LaRocque L, Yetman R, Ross TJ, Guistra E. Aggression and barroom environments. J Stud Alcohol. 1980;41:277–292. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1980.41.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Osgood DW, Zibrowski E, Purcell J, Gliksman L, Leonard K, Pernanen K, Saltz RF, Toomey TL. The effect of the Safer Bars programme on physical aggression in bars: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;23:31–41. doi: 10.1080/09595230410001645538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Tremblay PF, Wells S, Pernanen K, Purcell J, Jelley J. Harm, intent, and the nature of aggressive behavior. Measuring naturally occurring aggression in barroom settings. Assessment. 2006;13:280–296. doi: 10.1177/1073191106288180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Wells S. “Somebody’s gonna get their head kicked in tonight!” Aggression among young males in bars -- A question of values? Br J Criminol. 2003;43:546–566. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Wells S, Bernards S, Dennison S. “Yes, I do but not with you” - Qualitative analyses of sexual/romantic overture-related aggression in bars and clubs. Contemp Drug Probl. 2010;37:197–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs D, O’Brien K, Westmarland L. Connecting the gendered door: Women, violence and door work. Br J Sociol. 2007;58:21–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homel R, Clark J. The prediction and prevention of violence in pubs and clubs. In: Smith M, Cornish D, editors. Theory for Practice in Situational Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 3, Theory for Practice in Situational Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Studies. Criminal Justice Press; Monsey, N.Y: 1994. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Baker T, Mumford EA, Vishnuvajjala R, Voas RB, Romano E, Johnson M. A night in Tijuana: Female victimization in a high-risk environment. Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education. 2008;52:46–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M, Taylor PJ, Best R. Third parties, violence, and conflict resolution: The role of group size and collective action in the microregulation of violence. Psychol Sci. 2011;22:406–412. doi: 10.1177/0956797611398495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle M, Fuqua WR. Alcohol’s effects on women’s risk detection in a date-rape vignette. J Am Coll Health. 2007;55:261–266. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.5.261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustaine EE, Tewsksbury R. Sexual assault of college women: A feminist interpretation of a routine activities analysis. Crim Justice Rev. 2002;27:89–123. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Davis KC, George WH, Martell J, Heiman JR. Alcohol’s direct and indirect effects on men’s self-reported sexual aggression likelihood. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:688–695. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks K. An event-based analysis of aggression women experience in bars. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000;14:102–110. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh Y-P, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Miller BA. Bar victimization of women. Psychol Women Q. 1997;21:509–525. [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Scheidt DM. Male bar drinkers’ perspective on female bar drinkers. Sex Roles. 2000;43:927–941. [Google Scholar]

- Pino NW, Johnson-Johns AM. College women and the occurrence of unwanted sexual advances in public drinking settings. Soc Sci J. 2009;46:252–267. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor JB, Giedd JL, Williams KB. A social psychological model for predicting sexual harassment. J Soc Issues. 1995;51:69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell J, Graham K. A typology of Toronto nightclubs at the turn of the millennium. Contemp Drug Probl. 2005;32:131–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ronen S. Grinding on the dance floor: Gendered scripts and sexualized dancing at college parties. Gend Soc. 2010;24:355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Rotundo M, Nguyen DH, Sackett PR. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:914–922. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, DeKeseredy WS, Tait D, Alvi S. Male peer support and a feminist routine activities theory: Understanding sexual assault on the college campus. Justice Q. 2001;18:623–649. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DA, Robinson C, McCall PL. “Cooling out” men in singles bars and nightclubs: Observations on the interpersonal survival strategies of women in public places. J Contemp Ethnogr. 1991;19:423–449. [Google Scholar]

- Teplin L, Lutz GW. Measuring alcohol intoxication: The development, reliability and validity of an observational instrument. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46:459–466. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, Jr, Cracco EJ. Sexual aggression in bars: What college men can normalize. J Mens Stud. 2008;16:82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Karabatsos G, Koss MP. Alcohol and sexual aggression in a national sample of college men. Psychol Women Q. 1999;23:673–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wade JC, Critelli JW. Narrative descriptions of sexual aggression: The gender gap. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1998;17:363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Graham K. The frequency of third party involvement in incidents of barroom aggression. Contemp Drug Probl. 1999;26:457–480. [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Neighbors C, Tremblay PF, Graham K. Defending girlfriends, buddies, and oneself: Injunctive norms and male barroom aggression. Addict Behav. 2011;36:416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagil D, Karnieli-Miller O, Eisikovits Z, Enosh G. Is that a “No”? the interpretation of responses to unwanted sexual attention. Sex Roles. 2006;54:251–260. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.