Abstract

Background

Thrombocytopenia is a known consequence of HIV infection, and decreased production of platelets has been previously implicated in the pathogenesis of platelet decline during asymptomatic infection. Thrombopoietin (THPO) drives platelet production by stimulating the maturation of bone marrow megakaryocytes, and can be transcriptionally down-regulated by cytokines that are increased during infection such as TGFβ and pf4.

Design

To determine whether transcriptional down-regulation of THPO contributed to decreased platelet production during asymptomatic infection in the SIV/ macaque model of HIV, we compared hepatic THPO mRNA levels to platelet number and megakaryocyte density. To identify potential inhibitory factors that decrease THPO transcription during asymptomatic infection, we measured TGFβ and pf4 plasma levels. To determine whether cART could correct platelet decline by altering cytokine levels, we measured TGFβ and pf4 in cART-treated SIV-infected macaques and compared these values to untreated SIV-infected macaques.

Results

Hepatic THPO transcription was down-regulated during asymptomatic SIV infection concurrent with platelet decline. Hepatic THPO mRNA levels correlated with bone marrow megakaryocyte density. In contrast, plasma TGFβ levels were inversely correlated with hepatic THPO transcription and bone marrow megakaryocyte density. With cART treatment, plasma TGFβ levels and platelet count returned to values similar to those in uninfected macaques.

Conclusions

TGFβ mediated downregulation of hepatic THPO may lead to decline in platelet number during asymptomatic SIV infection, and cART may prevent platelet decline by normalizing plasma TGFβ levels.

Keywords: HIV, thrombocytopenia, platelet, SIV, thrombopoietin, TGFβ

Introduction

Platelet counts reach thrombocytopenia-defining lows of <100,000 platelets per μL in 5-30% of untreated HIV-infected individuals1, and decreased platelet production has been previously implicated in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated platelet decline2-5. Platelets arise from megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. Thrombopoietin (THPO), a large heavily glycosylated protein produced predominantly by the liver, drives platelet production by influencing the differentiation and maturation of megakaryocytes from CD34+ progenitor cells6. THPO levels are predominantly regulated by platelet mass; binding to its cognate receptor CD110/C-MPL on the platelet removes THPO from circulation, therefore allowing THPO levels to increase in the context of low platelet numbers7. However individuals with asymptomatic HIV infection have lower than expected plasma THPO given their thrombocytopenia8,9. The mechanisms leading to this unexpectedly low concentration of THPO in the face of insufficient numbers of circulating platelets have yet to be explored in detail, but the presentation suggests inappropriate regulation of THPO production. THPO produced by the liver contributes to the majority of platelet production10, and decreased hepatic THPO transcription has been previously associated with thrombocytopenia in the context of liver failure11. Transcriptional up- and down-regulation in response to cytokines has been described in detail for THPO, and the immune response to HIV results in elevated levels of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and platelet factor 4 (pf4) that have the potential to contribute to platelet decline during asymptomatic lentiviral infection12-17.

Thrombocytopenia only occurs in 3.2% of those treated with combined anti-retroviral therapy (cART)18. cART consists of combinations of anti-retroviral drugs that act to inhibit viral replication and also modulate the immune response to infection. Though treatment with cART is generally sufficient to correct low platelet counts in HIV-infected individuals and is recommended as a first line of therapy19, the mechanism through which cART remedies low platelet count in the context of HIV infection has yet to be defined. Megakaryocytes can become infected with HIV20, but direct infection is not necessary to hinder platelet production; HIV-1 gp120 interactions with megakaryocyte CD4 inhibit megakaryocyte maturation and trigger megakaryocyte apoptosis21. cART furthermore serves to dampen the inflammatory response in HIV infection, which includes factors such as TGFβ and pf4 that downregulate THPO transcription, and, in the case of TGFβ, directly block megakaryocyte maturation12,15,16.

To determine whether transcriptional downregulation of THPO could contribute to platelet decline during asymptomatic infection, we used the SIV/macaque model of HIV infection to examine platelet production and thrombopoeitin transcription. Our SIV-infected pigtailed macaque model develops consistent and persistent platelet decline during asymptomatic infection,22 and therefore provides an ideal system in which to investigate the mechanisms underlying decreased platelet counts in asymptomatic HIV infection.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male juvenile pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) were inoculated intravenously with both SIV/17E-Fr and SIV/DeltaB670 as previously described, or with sterile physiologic buffered saline to serve as uninfected controls23. Serology was negative for SIV, simian T-cell leukemia virus, and simian type D retrovirus for all macaques prior to this study. Macaques in the combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) group were given the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) tenofovir (30 mg/kg, Gilead) subcutaneously once daily, the integrase inhibitor L-870812 (10 mg/kg, Merck) orally once daily, and the protease inhibitors (PI) atazanavir (270 mg/kg, Bristol-Myers Squibb) and saquinavir (205 mg/kg, Roche) orally twice daily starting on day 12 post-inoculation.24 For phlebotomy, macaques were sedated with an intramuscular dose of 10 mg/kg ketamine HCl (KetaVed from Vedco Inc, St. Joseph, MO, USA), and prior to terminal sample procurement (bone marrow for megakaryocyte density and liver for THPO qRT-PCR) animals were anesthetized with intravenous 25 mg/mL sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal from Lundbeck Inc, Deerfield, IL, USA) prior to perfusion with saline.

Animals were housed in Johns Hopkins University facilities that are fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAS). Macaques were fed a commercial macaque diet (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA), given water ad libitum, and provided with environmental enrichment daily. All procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and conducted in accordance with guidelines set forth in the Animal Welfare Regulations (USDA) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (OLAW).

Circulating platelet counts and mean platelet volume

Whole blood was collected for platelet counts from 19 untreated SIV-infected, 5 cART-treated SIV-infected, and 12 untreated uninfected control macaques at three pre-inoculation timepoints and on days 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, 42, 56, 70 and 84 post-inoculation. Blood was collected from the femoral vein directly into a syringe containing citrate-dextrose solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 1:5 volume, and 1.0 mL of this blood was then submitted to a commercial hematology laboratory for platelet counts and determination of mean platelet volume (MPV; MPV data for 5 of the 19 untreated SIV-infected and 3 of the 12 untreated uninfected control macaques were not available) (IDEXX, Westbrook, ME, USA).

Plasma TGFβ and pf4 concentration

Citrated whole blood was harvested on day 42 post-inoculation from 19 untreated SIV-infected, 5 cART-treated SIV-infected, and 4 untreated uninfected control macaques and was centrifuged at 2500 g for 15 minutes to obtain plasma. Plasma was stored at −80°C prior to analysis for TGFβ concentration at a 1:8 dilution and pf4 concentration at a 1:400 dilution using commercially available ELISAs (Quantikine Human TGFβ1 or DuoSet CXCL4/Pf4, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Thrombopoietin (THPO) mRNA production in liver

For measurement of hepatic THPO mRNA production, liver tissue was harvested at necropsy on day 42 post-inoculation from 9 untreated SIV-infected and 3 uninfected control macaques. Tissue was immediately frozen by submersion in liquid nitrogen cooled 2-methylbutane, and stored at −80°C. An RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and two sequential digestions with DNase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA and Promega, Madison, WI, USA) were used to extract RNA from banked hepatic tissue. cDNA was made using oligo (dT) 12-18 primers, Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) and the parameters of 5 minutes at 65°C, 1 minute at 4°C, 5 minutes at 25°C, 60 minutes at 50°C and 15 minutes at 70°C on a PTC-200 Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research Inc, St. Bruno, Quebec, Canada). In a similar manner to methods previously described for human THPO,25 qRT-PCR for THPO was achieved through subsequent qPCR amplification of a 152 base pair sequence spanning exons 3 and 4 of THPO labeled by a 5’-Hex/3’-Iowa black FQ-labeled probe 5’-AGTAAACTGCTTCGTGACTCCCATGTCCT-3’ flanked by the forward primer 5’-ATTGCTCCTCGTGGTCATGC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-AAGGGTTAACCTCTGGGCACA-3’(Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA). The Quantitect Multiplex PCR kit without reverse transcriptase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) was used to amplify THPO mRNA over 36 cycles of 15 seconds at 94°C, 15 seconds at 55°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C on a Bio (Bio-Rad iCycler iQ5 PCR Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). C(t) values were normalized to the housekeeping gene 18S (5’-Cy5/3’-BHQ2-labeled probe 5’-AGCAATAACAGGTCTGTGATG-3’ flanked by the forward primer 5’-TAGAGGGACAAGTGGCGTTC-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-CGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGT-3’) to control for variability in RNA loading, and delta C(t) values were normalized to the median THPO expression of uninfected control macaques.

Bone marrow megakaryocyte density

Bone marrow was harvested from the femur at necropsy from 9 SIV-infected macaques on day 42 post-inoculation and from 5 uninfected control macaques. Tissue was fixed for 7 days by immersion in tissue fixative (Streck, Omaha, NE, USA) before being embedded in paraffin, cut into 5μm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. As previously reported,22 megakaryocytes were quantified within a 3.35 mm2 region of interest using Stereo Investigator software on a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a motorized stage and a MBF Bioscience color camera (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT, USA). Megakaryocytes were identified at 200X magnification by their distinctive morphology including large size and complex nuclei. Three sections of bone marrow per slide were chosen for analysis, and megakaryocyte numbers were normalized to the area of bone marrow analyzed to yield megakaryocytes/mm2. Two animals were excluded from analysis because CD68+/CD163+ macrophages and multinucleate giant cells were identified in the bone marrow using immunohistochemistry as previously described.26

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses used nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests to compare mock-inoculated uninfected macaques with SIV-infected macaques on day 42 post-inoculation, and nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by a Dunn's Multiple Comparison test to compare mock-inoculated uninfected macaques, SIV-infected macaques and cART-treated SIV-infected macaques. Correlations employed the nonparametric Spearman correlation. Statistical significance was defined by a P < 0.05. Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to organize data, and Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analyses and to construct all graphs.

Results

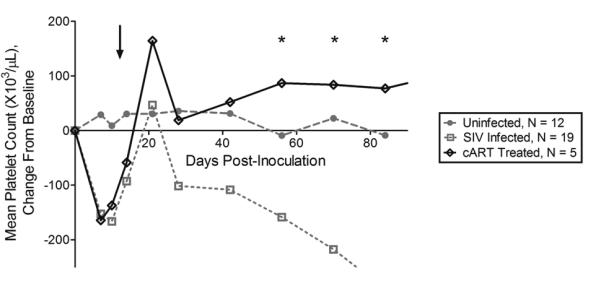

Platelet decline does not occur during asymptomatic SIV infection in cART treated macaques

A persistent platelet decline is common in asymptomatic HIV infection,1 and untreated SIV-infected macaques similarly develop a persistent decrease in platelet numbers during early asymptomatic infection (day 28 post-inoculation) through terminal infection (Fig. 1).22 cART is recommended as the preferred therapy for low platelet counts in HIV infected individuals19. We therefore questioned whether treatment with cART starting early in infection (day 12 post-inoculation) would prevent platelet decline in the SIV/macaque model of HIV infection. Though platelet decline started on day 28 post-inoculation and persisted into terminal infection in untreated SIV-infected macaques, cART-treated macaques demonstrated normal platelet counts during asymptomatic infection after 30 days of treatment. (Fig. 1, day of start of treatment indicated by arrow, Two Way ANOVA P < 0.0001, post-hoc Bonferroni multiple comparisons test P < 0.01 between SIV-infected and cART-treated on days 56, 70 and 84). Day 42 post-inoculation represents the mid-point of asymptomatic infection in our SIV/macaque model and the timepoint at which we begin to see a divergence in platelet number between uninfected and untreated SIV-infected macaques (Fig. 1). We therefore chose day 42 as a representative timepoint for further investigation into the cause of platelet decline during asymptomatic infection.

Fig. 1. SIV-associated platelet decline during asymptomatic infection was prevented by cART.

SIV-infected macaques developed platelet decline during asymptomatic infection. In contrast, platelet counts normalized in cART-treated macaques at days 56, 70 and 84 post-inoculation. cART treatment was started on day 12 post-inoculation (arrow). Lines represent mean value, * indicates statistical significance with P < 0.05.

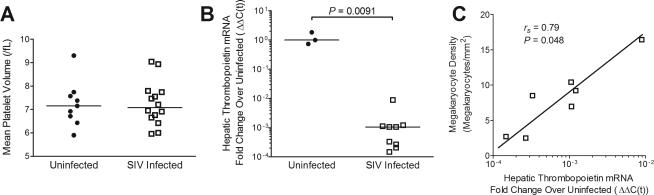

Platelet production is decreased during asymptomatic SIV infection

Platelet decline due to decreased platelet production has been previously reported in HIV-infected humans during asymptomatic infection2. Bone marrow megakaryocytes respond to decreases in circulating platelet number by releasing larger, less mature platelets27. To determine whether decreased platelet production contributed to platelet decline during asymptomatic infection in the untreated SIV/macaque model, we measured mean platelet volume (MPV) as an indicator of platelet production. There was no difference in MPV between SIV-infected and uninfected macaques (Fig. 2a, Mann-Whitney P = 1.00), indicating that bone marrow megakaryocytes did not increase platelet production as a compensatory response to platelet decline during asymptomatic infection in untreated SIV-infected macaques.

Fig. 2. Insufficient platelet production secondary to decreased hepatic THPO transcription contributed to platelet decline during asymptomatic SIV infection.

(A) Mean platelet volume in uninfected and SIV-infected macaques did not differ on day 42 post-inoculation. Bars represent median value. (B) Hepatic THPO mRNA in uninfected and SIV-infected macaques on day 42 post-inoculation. Bars represent median value. (C) Hepatic THPO mRNA compared to bone marrow megakaryocyte density in SIV-infected macaques on day 42 post-inoculation.

Thrombopoietin (THPO) transcription is downregulated, and correlates with megakaryocyte density

Thrombopoietin (THPO) drives platelet production primarily by stimulating bone marrow progenitor cells to differentiate into megakaryocytes6. The majority of platelet production depends upon hepatic THPO10, and decreased transcription of THPO has been associated with thrombocytopenia in children with liver failure11. We investigated whether hepatic THPO mRNA production was altered in SIV infection by measuring hepatic THPO mRNA levels by qRT-PCR. SIV-infected macaques demonstrated a 10,000-fold decrease in hepatic THPO transcription compared with uninfected controls (Fig. 2b, Mann-Whitney, P = 0.0091). This decrease in THPO mRNA was positively correlated with bone marrow megakaryocyte density (Fig. 2c, Spearman rs = 0.79, P = 0.048), consistent with a link between a deficiency of THPO production and a reduction in megakaryocyte number in the bone marrow. Since THPO influences platelet count by driving megakaryocyte differentiation within the bone marrow,6 it was not unexpected that hepatic THPO mRNA did not directly correlate with circulating platelet number (Spearman rs = −0.025, P = 0.95).

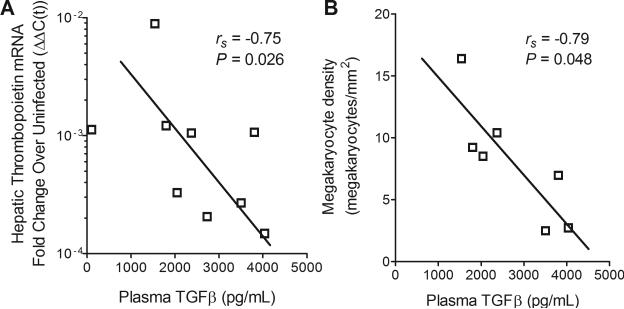

Plasma TGFβ levels influence THPO production and megakaryocyte density

As TGFβ and pf4 are known transcriptional repressors of THPO12, we next measured plasma levels of each during asymptomatic SIV infection. TGFβ was inversely correlated with both hepatic THPO mRNA production (Fig. 3a, Spearman rs = −0.75, P = 0.026) and with bone marrow megakaryocyte density (Fig. 3b, Spearman rs = −0.79, P = 0.048) during asymptomatic infection. In contrast, pf4 was not correlated with hepatic THPO mRNA (Spearman rs = −0.25, p = 0.52) or with megakaryocyte density (Spearman rs = −0.57, p = 0.15).

Fig. 3. Plasma TGFβ levels were inversely correlated with THPO transcription and megakaryocyte density.

(A) Plasma TGFβ compared to hepatic THPO mRNA in untreated SIV-infected macaques on day 42 post-inoculation. (B) Plasma TGFβ compared to bone marrow megakaryocyte density in untreated SIV-infected macaques on day 42 post-inoculation.

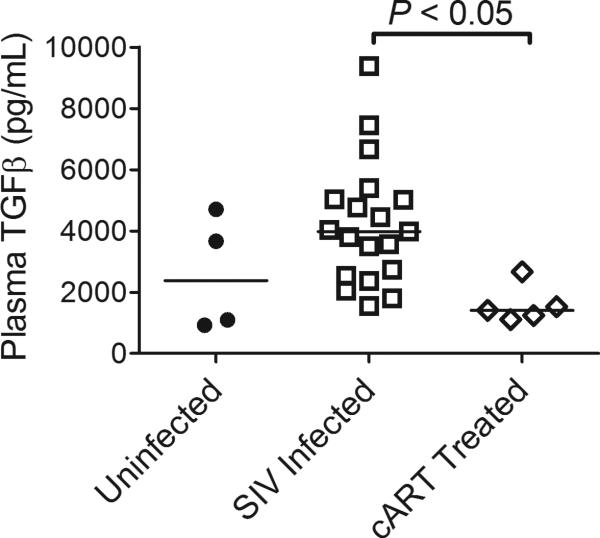

cART treatment corrects plasma TGFβ level

cART inhibits viral replication and modulates the cytokine response in HIV-infected patients. To determine whether cART could prevent platelet decline by countering the inhibitory control of TGFβ on THPO transcription, we compared plasma TGFβ levels in untreated versus cART-treated SIV-infected macaques. Elevated plasma TGFβ levels observed in untreated SIV-infected macaques were significantly reduced in cART treated macaques (Fig. 4, Kruskal-Wallis P = 0.0092, Dunn's Multiple Comparison Test P < 0.05 for SIV infected compared to cART-treated). This implies that correction of TGFβ levels may play a central role in the response of low platelet counts to cART.

Fig. 4. SIV-associated elevated plasma TGFβ was corrected by cART treatment.

Plasma TGFβ in untreated uninfected, untreated SIV-infected, and cART-treated SIV-infected macaques on day 42 post-inoculation. Bars represent median value.

Discussion

This study identified a novel candidate mechanism for thrombocytopenia in asymptomatic HIV infection, in which elevated plasma TGFβ downregulates hepatic THPO transcription. This results in insufficient numbers of bone marrow megakaryocytes with subsequent decreased platelet production and low circulating platelet counts. Both plasma TGFβ and platelet number were maintained at baseline levels in cART-treated SIV-infected macaques, showing that cART may contribute to the resolution of decreased platelet numbers by preventing TGFβ-driven inhibition of THPO transcription. These findings provide insight into the mechanisms underlying decreased platelet production during asymptomatic infection, and provide an explanation for the effectiveness of cART in correcting thrombocytopenia in HIV-infected individuals.

Our finding that hepatic THPO mRNA production was correlated with bone marrow megakaryocyte density in asymptomatic SIV infection concurrent with low circulating platelet numbers is consistent with the paradigm that THPO influences platelet count by driving the differentiation and maturation of megakaryocytes28,29. THPO of hepatic origin accounts for at least 60% of platelet production10, and platelet decline has previously been attributed to decreased hepatic THPO transcription in liver failure in children11. The magnitude of THPO's transcriptional downregulation and its strong correlations with megakaryocyte density imply that decreased platelet production secondary to downregulation of THPO transcription plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of platelet decline during asymptomatic infection. This finding is in contrast to the mechanisms contributing to the transient platelet decline during acute infection, in which platelet production is maintained while platelets are sequestered in platelet-monocyte aggregates.22 Additional study is necessary to determine whether THPO continues to be negatively regulated during terminal infection, or whether other mechanisms drive the continued decline in platelet numbers. Platelet decline during asymptomatic and terminal infection has been associated with the development of neurocognitive decline and increased mortality in HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected macaques.30-32 Thorough characterization of the mechanisms underlying platelet decline throughout infection will provide valuable insight into the pathogenesis of these deleterious consequences of HIV infection.

Marked downregulation of THPO transciption during asymptomatic SIV infection was inversely correlated with plasma TGFβ levels. We examined the plasma levels of TGFβ and pf4, two cytokines that are well-known to down-regulate THPO transcription in vitro12. Plasma TGFβ but not pf4 was inversely correlated with hepatic THPO mRNA levels, identifying TGFβ as a likely candidate for inhibiting THPO transcription in HIV infection. HIV infection stimulates increased production of TGFβ by monocytes33; TGFβ in the circulation may also originate from activated platelets12. The levels of TGFβ that we detected in the plasma of untreated SIV-infected macaques ranged from 1.5 to 9.4 ng/mL, in contrast to concentrations of 50 to 100 ng/mL previously reported to suppress the transcription of THPO in bone marrow stromal cells in culture12. Supplementary production of TGFβ by Kupffer cells in the liver may allow TGFβ to reach local tissue levels in vivo consistent with those reported to inhibit THPO transcription in vitro.12

We also report that plasma TGFβ levels were inversely correlated with megakaryocyte density. This is consistent with reports that TGFβ can directly arrest megakaryocyte maturation13 and supports a dual role for TGFβ in platelet decline during asymptomatic infection, with TGFβ inhibiting megakaryocyte development and therefore decreasing platelet numbers both indirectly by decreasing the production of THPO and directly through TGFβ-mediated maturation arrest in megakaryocytes. Decreased megakaryocyte differentiation/maturation or defective platelet production secondary to direct lentiviral contact or infection may also contribute to decreased production21,34. Other mechanisms, such as platelet destruction secondary to platelet autoantibodies raised versus homologous lentiviral envelope proteins and sequestration of activated platelets in leukocyte-platelet aggregates, also have the potential to contribute to platelet decline22,35,36. The myriad of factors that contribute to decreased platelet numbers during asymptomatic infection contrasts with the mechanism of platelet decline during acute infection, when sequestration of platelets in platelet-monocyte aggregates drives platelet decline while platelet production is maintained22.

cART normalized both plasma TGFβ levels and platelet counts in the SIV/macaque model during asymptomatic infection. Similar elevations in plasma TGFβ level have been previously noted in HIV-infected patients compared with healthy controls, and associated with the progression of disease.37 HIV-1 gp120 or Tat are sufficient to stimulate the production of TGFβ from hematopoietic stem cells or mammary epithelial cells in culture, respectively21,38. cART serves to suppress lentiviral replication and has been previously reported to decrease the level of TGFβ transcription in the lymph nodes of SIV-infected macaques39. Therefore, in untreated HIV infection, high viral loads stimulate TGFβ production, which can then inhibit THPO transcription, resulting in fewer megakaryocytes and in platelet decline. In cART treated patients, however, viral loads are low and do not stimulate TGFβ production, therefore allowing THPO to be produced and platelet numbers to be maintained. Unfortunately, hepatic samples from cART-treated macaques at day 42 post-inoculation were unavailable to test whether THPO transcription was truly restored in the SIV-infected macaque. Additional studies in which appropriate hepatic samples are procured and TGFβ is blocked through targeted pharmacologic or antibody therapy will help to establish the extent to which TGFβ down-regulates THPO transcription. Similarly, future investigations that evaluate thrombopoietin and TGFβ in the context of platelet number and clinical outcome in HIV-infected individuals will help to determine the clinical relevance of these findings. Though cART has proven to be effective therapy for most HIV-associated thrombocytopenia, treatment of thrombocytopenia remains imperfect. Corticosteroids, IVIg therapy and THPO mimetics are therapeutic for some but not all individuals with recurrent thrombocytopenia or thrombocytopenia resistant to cART19,40, and TGFβ inhibitors may prove an effective adjunct therapy in the treatment of these difficult cases.

In summary, we demonstrate that THPO transcription in the liver is down-regulated concurrent with platelet decline during asymptomatic SIV infection. Plasma TGFβ, a known inhibitor of both THPO transcription and megakaryocyte maturation, is inversely correlated with both hepatic THPO mRNA level and bone marrow megakaryocyte density, supporting a role for TGFβ in the pathogenesis of platelet decline during asymptomatic infection. We furthermore report that cART treatment corrects both plasma TGFβ level and platelet count, providing additional evidence for a link between TGFβ and decreased THPO in HIV-associated thrombocytopenia. These findings provide a novel explanation for platelet decline in the context of asymptomatic HIV infection.

Acknowledgements

We thank Phoebe Lewis for sample preparation, Elizabeth Engle for technical assistance, Lucio Gama and Kenneth Witwer for advice on assay development, M. Christine Zink and Janice Clements for collaborative resource sharing, Pat Tarwater for advice on statistics, Eric Hutchinson for editing the manuscript, and Lynn Wachtman for valuable discussion.

Source of Funding: K.A.M.P. and J.L.M. supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R25 MH080661). K.A.M.P. was also supported by the NIH (T32 OD011089). J.L.M. received NIH grant (R01 HL078479) and by the National Center for Research Resources and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) and the NIH (P40 OD013117).

Footnotes

Some of these data were presented in a poster session by K.A.M.P. in June 2012 at the Platelets 2012 International Symposium in Beverly, MA.

Conflicts of Interest

For the remaining authors no conflicts were declared.

References

- 1.Liebman HA, Stasi R. Secondary immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007 Sep;14(5):557–573. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282ab9904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landonio G, Nosari A, Spinelli F, Vigorelli R, Caggese L, Schlacht I. HIV-related thrombocytopenia: four different clinical subsets. Haematologica. 1992 Sep-Oct;77(5):398–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zucker-Franklin D, Termin CS, Cooper MC. Structural changes in the megakaryocytes of patients infected with the human immune deficiency virus (HIV-1). Am J Pathol. 1989 Jun;134(6):1295–1303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenig C, Sidhu GS, Schoentag RA. The platelet volume-number relationship in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991 Oct;96(4):500–503. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/96.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abgrall JF, el Kassar N, Berthou C, et al. HIV-associated thrombocytopenia: in vitro megakaryocyte colony formation in 10 patients. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1992;143(2):104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ragin A, D'Souza G, Reynolds S, et al. Platelet decline as a predictor of brain injury in HIV infection. Journal of neurovirology. 2011;17(5):487–495. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoffel R, Wiestner A, Skoda RC. Thrombopoietin in thrombocytopenic mice: evidence against regulation at the mRNA level and for a direct regulatory role of platelets. Blood. 1996 Jan 15;87(2):567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young G, Loechelt BJ, Rakusan TA, Nichol JL, Luban NL. Thrombopoietin levels in HIV-associated thrombocytopenia in children. J Pediatr. 1998 Dec;133(6):765–769. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatanaga H, Hoshikawa N, Tahara T, Kato T, Oka S. Serum thrombopoietin levels correlate with disease progression of AIDS. AIDS. 1999 Aug 20;13(12):1590–1591. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199908200-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian S, Fu F, Li W, Chen Q, de Sauvage FJ. Primary role of the liver in thrombopoietin production shown by tissue-specific knockout. Blood. 1998 Sep 15;92(6):2189–2191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolber EM, Ganschow R, Burdelski M, Jelkmann W. Hepatic thrombopoietin mRNA levels in acute and chronic liver failure of childhood. Hepatology. 1999 Jun;29(6):1739–1742. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sungaran R, Chisholm OT, Markovic B, Khachigian LM, Tanaka Y, Chong BH. The role of platelet alpha-granular proteins in the regulation of thrombopoietin messenger RNA expression in human bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 2000 May 15;95(10):3094–3101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakamaki S, Hirayama Y, Matsunaga T, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) induces thrombopoietin from bone marrow stromal cells, which stimulates the expression of TGF-beta receptor on megakaryocytes and, in turn, renders them susceptible to suppression by TGF-beta itself with high specificity. Blood. 1999 Sep 15;94(6):1961–1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolber EM, Fandrey J, Frackowski U, Jelkmann W. Hepatic thrombopoietin mRNA is increased in acute inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2001 Dec;86(6):1421–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lotz M, Seth P. TGF beta and HIV infection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993 Jun 23;685:501–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb35912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartzkopff F, Grimm TA, Lankford CS, et al. Platelet factor 4 (CXCL4) facilitates human macrophage infection with HIV-1 and potentiates virus replication. Innate Immun. 2009 Dec;15(6):368–379. doi: 10.1177/1753425909106171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaser A, Brandacher G, Steurer W, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates thrombopoiesis through thrombopoietin: role in inflammatory thrombocytosis. Blood. 2001;98(9):2720–2725. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks KM, Clarke RM, Bussel JB, Talal AH, Glesby MJ. Risk factors for thrombocytopenia in HIV-infected persons in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Dec;52(5):595–599. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b79aff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, Cohen A, Solberg L, Jr., Crowther MA. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. Apr 21;117(16):4190–4207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voulgaropoulou F, Pontow SE, Ratner L. Productive infection of CD34+-cell-derived megakaryocytes by X4 and R5 HIV-1 isolates. Virology. 2000 Mar 30;269(1):78–85. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibellini D, Vitone F, Buzzi M, et al. HIV-1 negatively affects the survival/maturation of cord blood CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells differentiated towards megakaryocytic lineage by HIV-1 gp120/CD4 membrane interaction. J Cell Physiol. 2007 Feb;210(2):315–324. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalf Pate KA, Lyons CE, Dorsey JL, et al. Platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation contribute to platelet decline during acute SIV infection in pigtailed macaques. J Infect Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit278. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clements JE, Mankowski JL, Gama L, Zink MC. The accelerated simian immunodeficiency virus macaque model of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurological disease: from mechanism to treatment. J Neurovirol. 2008 Aug;14(4):309–317. doi: 10.1080/13550280802132832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinoso JB, Rabi SA, Blankson JN, et al. A simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaque model to study viral reservoirs that persist during highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2009 Sep;83(18):9247–9257. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00840-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tacke F, Trautwein C, Zhao S, et al. Quantification of hepatic thrombopoietin mRNA transcripts in patients with chronic liver diseases shows maintained gene expression in different etiologies of liver cirrhosis. Liver. 2002 Jun;22(3):205–212. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2002.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly K, Tarwater P, Karper J, et al. Diastolic dysfunction is associated with myocardial viral load in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. AIDS (London, England) 2012;26(7):815–823. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283518f01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald T, Odell TT, Gosslee DG. Platelet size in relation to platelet age. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1964;115:684–689. doi: 10.3181/00379727-115-29006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Graaf CA, Metcalf D. Thrombopoietin and hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2011 May 15;10(10):1582–1589. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.10.15619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagata Y, Muro Y, Todokoro K. Thrombopoietin-induced polyploidization of bone marrow megakaryocytes is due to a unique regulatory mechanism in late mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1997 Oct 20;139(2):449–457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alcantara S, Reece J, Amarasena T, et al. Thrombocytopenia is strongly associated with simian AIDS in pigtail macaques. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Aug 1;51(4):374–379. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a9cbcf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wachtman LM, Skolasky RL, Tarwater PM, et al. Platelet decline: an avenue for investigation into the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus -associated dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007 Sep;64(9):1264–1272. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wachtman LM, Tarwater PM, Queen SE, Adams RJ, Mankowski JL. Platelet decline: an early predictive hematologic marker of simian immunodeficiency virus central nervous system disease. J Neurovirol. 2006 Feb;12(1):25–33. doi: 10.1080/13550280500516484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kekow J, Wachsman W, McCutchan JA, Cronin M, Carson DA, Lotz M. Transforming growth factor beta and noncytopathic mechanisms of immunodeficiency in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Nov;87(21):8321–8325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costantini A, Giuliodoro S, Mancini S, et al. Impaired in-vitro growth of megakaryocytic colonies derived from CD34 cells of HIV-1-infected patients with active viral replication. AIDS. 2006 Aug 22;20(13):1713–1720. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000242817.88086.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinder HM, Bonan JL, Rinder CS, Ault KA, Smith BR. Dynamics of leukocyte-platelet adhesion in whole blood. Blood. 1991 Oct 1;78(7):1730–1737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metcalf Pate K, Mankowski J. HIV and SIV Associated Thrombocytopenia: An Expanding Role for Platelets in the Pathogenesis of HIV. Drug discovery today. Disease mechanisms. 2011;8(1-2) doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiercińska-Drapalo A, Flisiak R, Jaroszewicz J, Prokopowicz D. Increased plasma transforming growth factor-beta1 is associated with disease progression in HIV-1-infected patients. Viral immunology. 2004;17(1):109–113. doi: 10.1089/088282404322875502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bettaccini AA, Baj A, Accolla RS, Basolo F, Toniolo AQ. Proliferative activity of extracellular HIV-1 Tat protein in human epithelial cells: expression profile of pathogenetically relevant genes. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boasso A, Vaccari M, Fuchs D, et al. Combined effect of antiretroviral therapy and blockade of IDO in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2009 Apr 1;182(7):4313–4320. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montaner JS, Le T, Fanning M, et al. The effect of zidovudine on platelet count in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3(6):565–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]