Abstract

During growth on surfaces, diverse microbial communities display topographies with captivating patterns. The quality and quantity of matrix excreted by resident cells play major roles in determining community architecture. Two current publications indicate that the cellular redox state and respiratory activity are important parameters affecting matrix output in the divergent bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus subtilis. These and related studies have identified regulatory proteins with the potential to respond to changes in redox state and respiratory electron transport and modulate the activity of the signal transduction pathways that control matrix production. These developments hint at the critical mechanistic links between environmental sensing and community behavior, and provide an exciting new context within which to interpret the molecular details of biofilm structure determination.

Introduction

The energy that fuels life is derived from electron transfer (redox) reactions. Changes in electron availability alter the intracellular redox state, affecting protein function and the stability of nucleic acids and lipids. Cells have therefore evolved mechanisms for coping with fluctuations in redox potential. In characterizing these mechanisms, researchers in many fields have traditionally focused on the high metabolic activity or exposure to strong oxidants that can generate toxic, enzyme-damaging species [1,2]. However, homeostatic mechanisms are also important during more subtle variations in redox potential. Redox balance—the relative availability of electron donors and acceptors—has critical implications for metabolism, and is a particularly formative parameter during multicellular growth.

Cells in all multicellular systems face the challenge of substrate limitation due to the effects of diffusion and consumption by cells closer to the system boundary. Oxygen limitation has been a focus of research on the development of multicellular systems due to its importance as a terminal electron acceptor for many organisms. Key examples of the crucial regulatory roles of oxygen gradients include their effects on angiogenesis, fetal development, and tumor development, processes in eukaryotes for which elaborate regulatory pathways have been elucidated [3]. The significance of oxygen limitation in the development of eukaryotic multicellular systems was appreciated long before its relevance for prokaryotic ones. An even more recent event is the recognition that oxygen gradient formation not only affects the metabolism and survival of cells in bacterial communities [4,5], but also their behavior and community morphogenesis. This finding is the focus of two current publications that reveal the influence of redox balance on community structural development for biofilms of two divergent bacteria, the gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the gram-positive Bacillus subtilis [6,7].

Microbial multicellularity

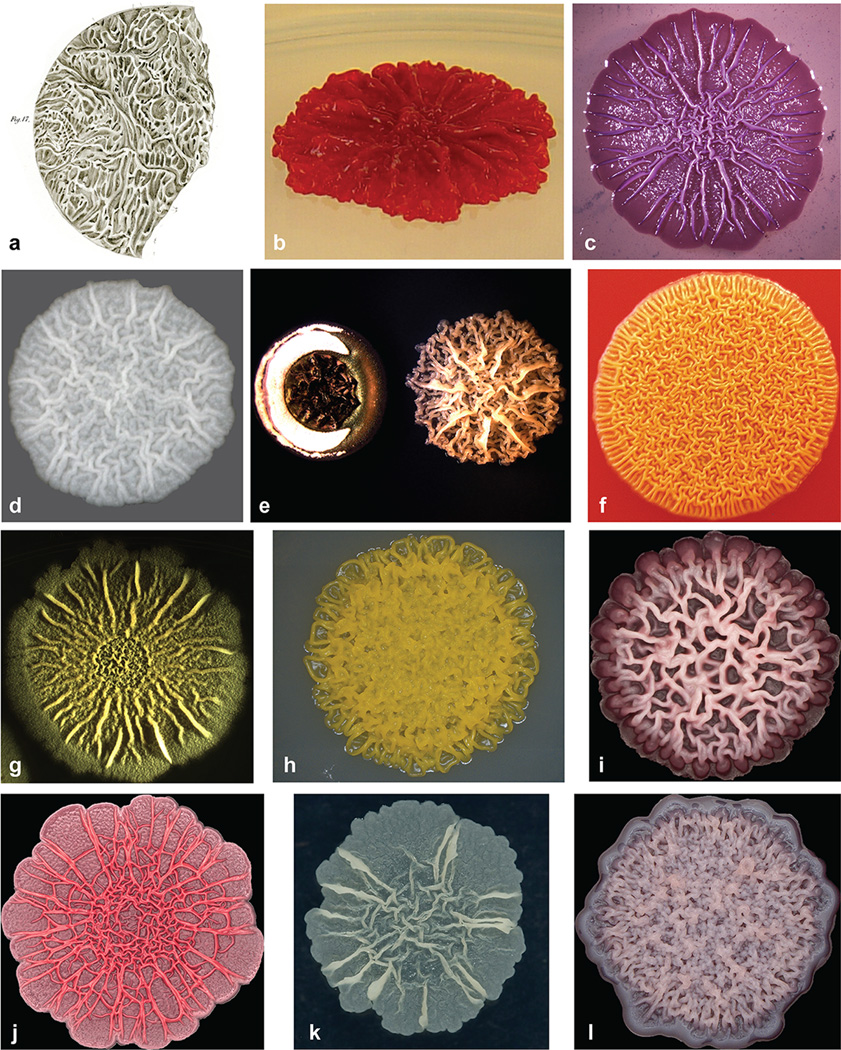

Biofilms—aggregates of microorganisms encased in excreted matrices—can form under diverse conditions in the laboratory and in the wild. In static cultures, biofilms grow at air-gel interfaces, forming colonies, or at air-liquid interfaces, forming pellicles. Probably as long as these culture techniques have been in use, microbiologists have marveled at the elaborate morphologies, visible to the naked eye, that are often formed by such communities [8,9]. The wrinkled structures of rugose colonies and pellicles have strikingly similar appearances in phylogenetically disparate organisms. Wrinkle-forming organisms that have become models for the study of biofilm morphogenesis include representatives from the genera Bacillus [10–14], Candida [15,16], Escherichia [17,18], Pseudomonas [19–21], Rhodospirillum [22], Saccharomyces [23–25], Salmonella [26], Serratia [27], Vibrio [28,29] and members of the phylum Actinobacteria [30,31] (Figure 1). The extent of wrinkling varies widely between isolates, even within the same species, and is condition-dependent. Therefore, although for many of these systems a specific strain and morphotype is often considered more “natural”, representative, or relevant for biofilm formation “in the wild”, we submit that any system in which a community of microbes is growing on a surface encased in a self-produced matrix, regardless of its gross morphology, is still a biofilm that has solved the problem of electron acceptor limitation in some way, with physiological characteristics that are interesting in their own right.

Figure 1.

Wrinkled morphologies are formed by diverse microbial communities at the interface with air. (a) Coccobacteria septica pellicle (T. Billroth, 1874). (b) Cyst-forming Rhodospirillum centenum (J. Berleman and C. Bauer). (c) Escherichia coli K-12 derivative AR3110 (R. Hengge). (d) Saccharomyces cerevisiae SK1 (C. Sison, B. Miller, and L. Dietrich). (e) Streptomyces coelicolor M145 (left) and Amycolatopsis sp. AA4 (right) (M. Traxler and R. Kolter). (f) Serratia marcescens strain CHASM, isolated from a backyard compost heap (R. Shanks). (g) Bacillus subtilis NCIB3610 (M. Cabeen and R. Losick). (h) Pseudomonas oryzihabitans, isolated from a bench in Riverside Park, New York, NY (S. Jordan and L. Dietrich). (i) Candida albicans (D. Morales and D. Hogan). (j) Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 Δphz mutant (D. Murphy and L. Dietrich). (k) Mycobacterium smegmatis (A. Balachandran and G. Hatfull). (l) Vibrio cholerae rugose colony variant (N. Fong, F. Yildiz, and H. Sakhtah).

The molecular details, mechanics, and physiological relevance of structural development have been studied for many models of microbial multicellularity. Large bodies of work describe the signaling cascades that control motility and matrix production and thereby affect biofilm morphogenesis. In B. subtilis biofilms, nonuniform cell death has been observed to precede and proposed to determine wrinkle pattern formation when mechanical forces, arising from colony growth, promote vertical buckling [32]. Results from an additional study in B. subtilis have suggested that wrinkles are actually channels that allow for enhanced liquid transport through the biofilm [33]. Despite these advances, for most models a thorough analysis of the response to environmental cues, and especially to changes in redox potential, have not been conducted. The significance of redox potential in determining biofilm morphology has only become apparent over the last few years with the examination of this relationship in P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis. Results from these studies suggest that colony wrinkling enhances access to oxygen and maintenance of redox homeostasis for bacteria in biofilms.

Structural modulation as a response to redox imbalance and a strategy for accessing oxygen

Electron transfer within hypoxic communities: P. aeruginosa

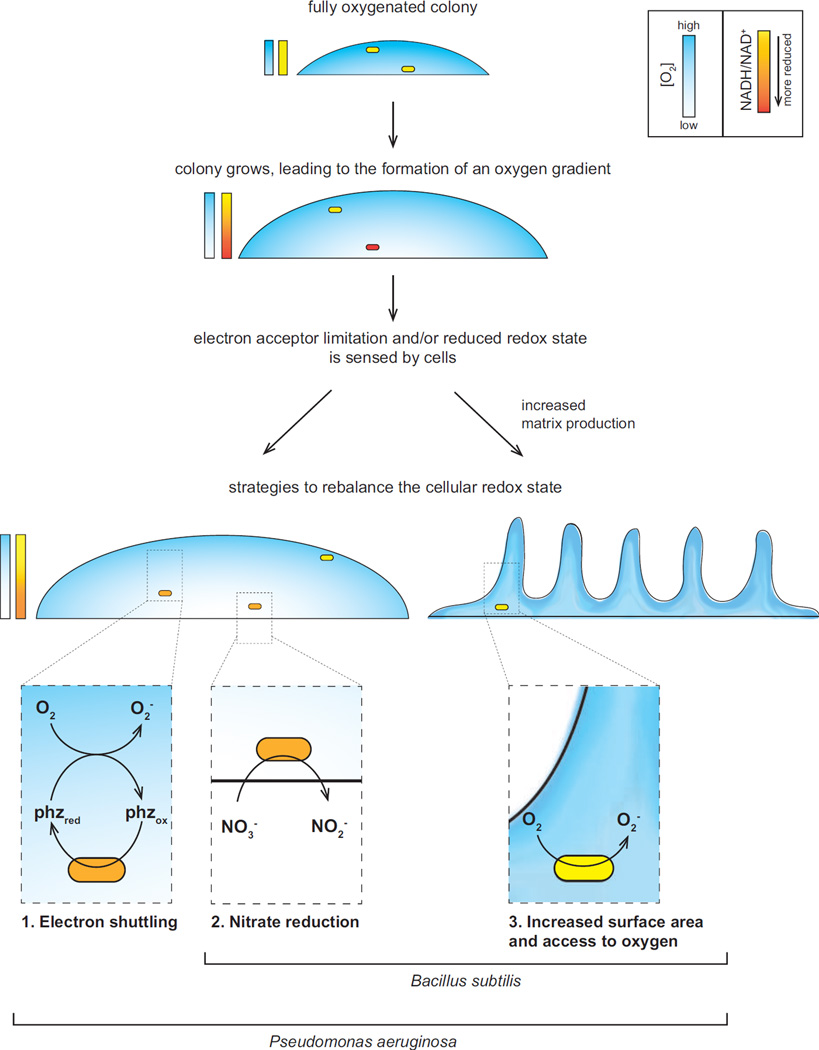

The elaborate wrinkles formed by colonies of some P. aeruginosa mutants became a focus of our work when we discovered the change in morphology--dramatically enhanced rugosity--that occurs when this organism is unable to produce antibiotics called phenazines [34,35]. Phenazines are redox-active and are reduced and excreted by P. aeruginosa [36]. Extracellularly, they react readily with oxidants and can be taken up by the bacteria once again, thus acting as mediators that facilitate extracellular electron transfer [37]. Such phenazine redox cycling can support survival when P. aeruginosa is incubated in suspension with no terminal electron acceptors other than an electrode poised to catalyze phenazine oxidation [38]. Knowing that phenazines could play this physiological role, and upon observing the rugose morphology of a phenazine-null mutant, we postulated that colony wrinkling is an adaptation that supports redox balancing in response to electron acceptor limitation. Through a variety of approaches, we demonstrated that the rugose morphotype increases colony surface area and access to oxygen for resident bacteria when phenazines and other electron acceptors are absent. Consistent with this, the production of phenazines or medium amendment with the alternate electron acceptor nitrate promotes colony smoothness [6]. That the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio increases in the phenazine-null mutant just prior to wrinkling, then decreases as wrinkles develop, further underscores the role of colony wrinkling in increasing access to oxygen and enabling redox balancing (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Electron shuttling, nitrate reduction, and colony wrinkling are strategies that can support redox balancing, indicated by the NADH/NAD+ ratio, for microbes in biofilms. The model presented here is based on findings from two recent publications concerning colony morphogenesis in P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis; whether these strategies are employed in other microbial communities remains to be investigated.

Electron transfer within hypoxic communities: B. subtilis

Whether colony wrinkling is a strategy for accessing oxygen in the diversity of rugose colony models that have been studied is still unknown. However, a recent publication by Kolodkin-Gal et al. indicates that this scenario does hold in the bacterium B. subtilis [7]. B. subtilis does not produce phenazines, but, as we have observed in P. aeruginosa, varying the atmospheric oxygen concentration modulates the extent of colony wrinkling. Furthermore, adding nitrate to the medium also decreases wrinkling. The effects of varying oxygen concentration and adding nitrate on both colony systems are consistent with the model that colony wrinkling is a readout for redox imbalance. Interestingly, different nitrate reductases appear to be involved in the rugose-smooth morphological change that occurs when P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis are grown with nitrate in an aerobic atmosphere. While P. aeruginosa requires the periplasmic nitrate reductase Nap for smooth colony formation on nitrate, B. subtilis requires the membrane-assocated (respiratory), cytoplasmic nitrate reductase Nar. Nevertheless, these results suggest that for both P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis, wrinkling to enhance access to oxygen and utilization of nitrate (when available) are strategies for balancing the intracellular redox state during growth in biofilms (Figure 2). In organisms where additional anaerobic metabolisms, such as fermentation, contribute to redox balancing, utilization of such strategies may support the survival of bacteria in anoxic biofilm regions [18].

Electron shuttling in biofilms: a more general strategy?

Though many additional studies are required to investigate the physiological roles of wrinkling in the diverse microbes that adopt this colony morphology, intriguing findings across phylogeny point to a theme with respect to the roles of mediator compounds. In early work examining respiratory activity in both normal and malignant tissues, biologists observed that compounds such as phenazines increased respiration rates [39,40]. They theorized that such mediators could act as electron acceptors for cells experiencing oxygen limitation within tissues, then diffuse to aerobic zones for re-oxidation. Furthermore, upon observing that such electron acceptors are produced by certain species of bacteria, some authors also suggested that they could act as endogenous respiratory substrates [41]. It was only recently and with the increased appreciation that the biofilm lifestyle is a dominant mode of growth for many microorganisms that it became apparent that mediators could support redox balancing for their producing cells during residence in multicellular structures. Intriguingly, mutants of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) unable to produce the diffusible redox-active antibiotic actinorhodin form more rugose colonies than their wild-type parent, raising the possibility that pigment-dependent electron shuttling occurs in diverse organisms [34]. Microbes that do not produce mediators may be able to utilize diffusible redox-cycling compounds produced by other organisms in the environment to support redox balancing during multicellular growth. In this context it is interesting to note that phenazines induce a rugose-to-smooth morphotypic transformation in colonies of the yeast Candida albicans [16], though whether C. albicans communities can use phenazines for extracellular electron transfer and cellular redox balancing in biofilms is not known.

Mechanisms linking cue/signal sensing to community output

Connecting redox state to morphogenesis in B. subtilis

Production of an extracellular matrix, which can comprise polysaccharides, amyloid proteins, and nucleic acids, is an important defining feature of biofilms [42]. Specific matrix components, which vary between organisms, are required for the formation of certain structures. In P. aeruginosa PA14, the Pel polysaccharide is required for colony wrinkling [19]. Importantly, a double mutant unable to produce Pel polysaccharide or phenazines remains smooth and exhibits a reduced intracellular redox state that persists throughout colony development [6]. This finding suggests that the NADH/NAD+ ratio, or another indicator of the cellular redox potential, is sensed by regulatory pathways that control features such as Pel polysaccharide production that then control colony wrinkling. In B. subtilis, a polysaccharide encoded by the eps genes and the amyloid protein TasA are major components of the matrix that are required for wild-type wrinkling [13]. Kolodkin-Gal et al. found that expression from the promoter controlling the tapA-sipW-tasA or “tapA” operon correlated with wrinkling in the context of varying oxygen and nitrate availability. Decreasing the concentration of FeCl3 in the medium demonstrated a correlation between wrinkling, expression from PtapA, and oxidation of the NAD(H) pool (decreased NADH/NAD+). However, a time course was not conducted, so this study does not examine the possibility of a causative relationship between changes in the NADH/NAD+ ratio and colony wrinkling. Production of the polysaccharide cellulose and curli fimbriae are required for rugosity in E. coli and S. enterica Typhimurium [18,43–45], and a polysaccharide critical for rugosity has also been described for Vibrio cholerae [46,47]. Various stresses have been shown to affect the production of these components, though in most cases it is not clear whether redox imbalance is one of them. Interestingly, studies examining the effects of oxygen limitation on regulatory gene expression, and the abundance of NAD+ in wild-type and matrix-deficient strains, in Salmonella suggest that colony development could both respond to and affect redox homeostasis in this organism [48,49].

If sensing of the internal redox state is directly related to initiation of wrinkling, what signal transduction pathways are mediating this response? In B. subtilis, a regulatory cascade, which proceeds via expression of the anti-repressor SinI, links matrix gene expression to the master regulator Spo0A. The phosphorylation state and activity of Spo0A is determined by a phosphorelay, and the histidine kinases KinA-E contribute phosphoryl groups to this relay [50]. Kolodkin-Gal et al. reported that wild-type colony wrinkling requires KinA-D. When expression from the sinI promoter (expected to correlate with tapA expression and wrinkling) was measured for various KinA-D single and double mutants, a kinA kinB double mutant showed the most dramatic decrease relative to the wild type. The colony phenotype of this double mutant closely resembled that of the wild type grown with 5 µM FeCl3, where no wrinkling occurred during the incubation time used for the experiment. KinB is predicted to bind to the cell membrane. Immunoprecipitation experiments and mutational analyses suggested that KinB interacts with components of the electron transport chain, which may allow KinB to sense respiratory activity and transduce this information into a macroscopic response.

In contrast to KinB, KinA is not predicted to interact with the membrane. KinA contains three tandem PAS domains, motifs that often bind small molecule ligands. In organisms ranging from bacteria to plants and humans, PAS domains have been shown to sense signals and parameters such as redox potential, oxygen availability, and light intensity through conformational changes or phosphorylation events [51]. Associated effector domains on the same protein propagate this signal to downstream targets. The PAS-A and PAS-C domains of KinA were found to be necessary for wild-type levels of PsinI activity and wrinkling. Through HPLC and mass spectrometry of extracts from purified KinA, NAD+ was identified as a potential ligand for the PAS-A domain. This result suggests that KinA contributes to the morphological response to changes in iron levels and oxygen availability by sensing the effects of these environmental cues on the cellular NAD(H) pool [7].

Connecting redox state to morphogenesis in P. aeruginosa

Unpublished work has also indicated a role for PAS domain-containing proteins in P. aeruginosa colony morphogenesis. To find the players involved in sensing and initiating the response to electron acceptor limitation in colonies, we screened a P. aeruginosa PA14 transposon mutant library for hyperwrinkled mutants. Focusing on proteins with predicted sensory and signal transduction roles, we hypothesized that the mutants hyperwrinkled due to an inability to relay accurate information about intracellular redox state; i.e., they wrinkled to alleviate a redox stress that didn’t exist. Several mutants representing PAS domain-containing proteins were found among the hyperwrinklers. Our studies suggest that one of these proteins affects Pel polysaccharide production by modulating levels of the ubiquitous second messenger cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP).

Redox-driven modulation of multicellular structure: themes across phylogeny

C-di-GMP-dependent regulation is a common theme in diverse models of bacterial multicellularity, linking signal transduction cascades to matrix production [47,52–54]. The presence of YciR, a PAS domain-containing protein, in a signaling network that modulates c-di-GMP levels in E. coli suggests that the involvement of PAS domains in these hierarchies is also a common feature [55]. With the identification of redox imbalance as a key signal exerting global control over these mechanisms, the studies in P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis that we have highlighted suggest that, as in complex multicellular eukaryotes, community development responds to and determines the redox state of individual cells in the population. As the role of relative electron donor and acceptor availability in shaping populations is determined for additional and diverse microbial species, the importance of redox chemistry, not just to metabolism but also to morphogenesis, in biology becomes all the more evident.

Highlights.

Microbes form rugose macrocolonies (biofilms) with intricate patterns of wrinkles.

Wrinkling is a response to oxidant limitation that facilitates redox balancing.

Newly identified proteins may sense and regulate the colony response to redox stress.

Redox control of matrix output and structure is an emerging theme in biofilm studies.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the many microbiologists who contributed images of wrinkled colonies for Figure 1. The authors acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (1 R01 AI103369-01A1 to L.E.P.D.). C.O. is a Gilliam Fellow of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Green J, Paget MS. Bacterial redox sensors. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:954–966. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foyer CH, Noctor G. Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1866–1875. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giaccia AJ, Simon MC, Johnson R. The biology of hypoxia: the role of oxygen sensing in development, normal function, and disease. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2183–2194. doi: 10.1101/gad.1243304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu KD, Stewart PS, Xia F, Huang CT, McFeters GA. Spatial physiological heterogeneity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm is determined by oxygen availability. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4035–4039. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.4035-4039.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner E, Roe F, Bugnicourt A, Franklin MJ, Heydorn A, Molin S, Pitts B, Stewart PS. Stratified growth in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6188–6196. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6188-6196.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dietrich LE, Okegbe C, Price-Whelan A, Sakhtah H, Hunter RC, Newman DK. Bacterial community morphogenesis is intimately linked to the intracellular redox state. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:1371–1380. doi: 10.1128/JB.02273-12. ** One of two recent studies that characterized the relationship between electron acceptor availability and bacterial colony morphogenesis. Demonstrated nitrate- and Nap-dependent modulation of colony structure in P. aeruginosa. Showed that the cellular redox state is maximally reduced immediately prior to the onset of wrinkling in the absence of alternate electron acceptors and that matrix-dependent colony wrinkling is required for redox balancing under this condition.

- 7. Kolodkin-Gal I, Elsholz AK, Muth C, Girguis PR, Kolter R, Losick R. Respiration control of multicellularity in Bacillus subtilis by a complex of the cytochrome chain with a membrane-embedded histidine kinase. Genes Dev. 2013;27:887–899. doi: 10.1101/gad.215244.113. ** One of two recent studies that characterized the relationship between electron acceptor availability and bacterial colony morphogenesis. Demonstrated nitrate- and Nar-dependent modulation of colony structure in B. subtilis. Presented evidence that KinA and KinB sense respiratory activity and redox state, respectively, and transduce these cues into regulation of matrix production.

- 8.Billroth T. Untersuchungen über die Vegetationsformen von Coccobacteria septica und den Antheil, welchen sie an der Entstehung und Verbreitung der accidentellen Wundkrankheiten haben. Berlin: G. Reimer; 1874. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohn F. Untersuchungen über Bacterien. II. In: Cohn F, editor. Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen. Drittes Heft. J.U. Kern's Verlag; 1875. pp. 141–207. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branda SS, Gonzalez-Pastor JE, Ben-Yehuda S, Losick R, Kolter R. Fruiting body formation by Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11621–11626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191384198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearns DB, Chu F, Branda SS, Kolter R, Losick R. A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:739–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilar C, Vlamakis H, Guzman A, Losick R, Kolter R. KinD is a checkpoint protein linking spore formation to extracellular-matrix production in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. MBio. 2010;1 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00035-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero D, Aguilar C, Losick R, Kolter R. Amyloid fibers provide structural integrity to Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2230–2234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910560107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branda SS, Gonzalez-Pastor JE, Dervyn E, Ehrlich SD, Losick R, Kolter R. Genes involved in formation of structured multicellular communities by Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3970–3979. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3970-3979.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez JP, Gil ML, Casanova M, Lopez-Ribot JL, Garcia De Lomas J, Sentandreu R. Wall mannoproteins in cells from colonial phenotypic variants of Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2421–2432. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales DK, Grahl N, Okegbe C, Dietrich LE, Jacobs NJ, Hogan DA. Control of Candida albicans metabolism and biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazines. MBio. 2013;4:e00526–e00512. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00526-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DePas WH, Hufnagel DA, Lee JS, Blanco LP, Bernstein HC, Fisher ST, James GA, Stewart PS, Chapman MR. Iron induces bimodal population development by Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2629–2634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218703110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Serra DO, Richter AM, Hengge R. Cellulose as an architectural element in spatially structured Escherichia coli biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JB.00946-13. **Demonstrated the requirement for both a protein component (curli fibers) and a polysaccharide component (cellulose) of the matrix for formation of spreading colonies with radial ridges in a “de-domesticated” derivative of E. coli K-12. Presented beautiful high-resolution images of colony structures and structural elements (cells and matrix).

- 19.Friedman L, Kolter R. Genes involved in matrix formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:675–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueda A, Wood TK. Connecting quorum sensing, c-di-GMP, pel polysaccharide, and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa through tyrosine phosphatase TpbA (PA3885) PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000483. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colvin KM, Irie Y, Tart CS, Urbano R, Whitney JC, Ryder C, Howell PL, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. The Pel and Psl polysaccharides provide Pseudomonas aeruginosa structural redundancy within the biofilm matrix. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:1913–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berleman JE, Hasselbring BM, Bauer CE. Hypercyst mutants in Rhodospirillum centenum identify regulatory loci involved in cyst cell differentiation. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5834–5841. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5834-5841.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Granek JA, Magwene PM. Environmental and genetic determinants of colony morphology in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuthan M, Devaux F, Janderova B, Slaninova I, Jacq C, Palkova Z. Domestication of wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae is accompanied by changes in gene expression and colony morphology. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:745–754. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voordeckers K, De Maeyer D, van der Zande E, Vinces MD, Meert W, Cloots L, Ryan O, Marchal K, Verstrepen KJ. Identification of a complex genetic network underlying Saccharomyces cerevisiae colony morphology. Mol Microbiol. 2012;86:225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romling U, Sierralta WD, Eriksson K, Normark S. Multicellular and aggregative behaviour of Salmonella typhimurium strains is controlled by mutations in the agfD promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:249–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanks RM, Lahr RM, Stella NA, Arena KE, Brothers KM, Kwak DH, Liu X, Kalivoda EJ. A Serratia marcescens PigP homolog controls prodigiosin biosynthesis, swarming motility and hemolysis and is regulated by cAMP-CRP and HexS. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yildiz FH, Schoolnik GK. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: Identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:4028–4033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildiz FH, Visick KL. Vibrio biofilms: so much the same yet so different. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen KT, Willey JM, Nguyen LD, Nguyen LT, Viollier PH, Thompson CJ. A central regulator of morphological differentiation in the multicellular bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:1223–1238. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Traxler MF, Seyedsayamdost MR, Clardy J, Kolter R. Interspecies modulation of bacterial development through iron competition and siderophore piracy. Mol Microbiol. 2012;86:628–644. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Asally M, Kittisopikul M, Rue P, Du Y, Hu Z, Cagatay T, Robinson AB, Lu H, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Suel GM. Localized cell death focuses mechanical forces during 3D patterning in a biofilm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18891–18896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212429109. *Presented a model for the formation of wrinkles in B. subtilis colonies, in which cell division and matrix production generates compressive forces and buckling occurs in areas of localized cell death.

- 33.Wilking JN, Zaburdaev V, De Volder M, Losick R, Brenner MP, Weitz DA. Liquid transport facilitated by channels in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:848–852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216376110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietrich LE, Teal TK, Price-Whelan A, Newman DK. Redox-active antibiotics control gene expression and community behavior in divergent bacteria. Science. 2008;321:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1160619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mavrodi DV, Blankenfeldt W, Thomashow LS. Phenazine compounds in fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. biosynthesis and regulation. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2006;44:417–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.013106.145710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LE, Newman DK. Rethinking 'secondary' metabolism: physiological roles for phenazine antibiotics. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nchembio764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hernandez ME, Newman DK. Extracellular electron transfer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1562–1571. doi: 10.1007/PL00000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Kern SE, Newman DK. Endogenous phenazine antibiotics promote anaerobic survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa via extracellular electron transfer. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:365–369. doi: 10.1128/JB.01188-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barron ES. The catalytic effect of methylene blue on the oxygen consumption of tumors and normal Tissues. J Exp Med. 1930;52:447–456. doi: 10.1084/jem.52.3.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedheim EA. The effect of pyocyanine on the respiration of some normal tissues and tumours. The Biochemical Journal. 1934;28:173–179. doi: 10.1042/bj0280173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swan GA, Felton DGI, Weissberger A. The Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds: Phenazines. Vol. 11. London: Int. Publ.; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mann EE, Wozniak DJ. Pseudomonas biofilm matrix composition and niche biology. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:893–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00322.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serra DO, Richter AM, Klauck G, Mika F, Hengge R. Microanatomy at cellular resolution and spatial order of physiological differentiation in a bacterial biofilm. MBio. 2013;4:e00103–e00113. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00103-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zogaj X, Nimtz M, Rohde M, Bokranz W, Romling U. The multicellular morphotypes of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli produce cellulose as the second component of the extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1452–1463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romling U, Rohde M, Olsen A, Normark S, Reinkoster J. AgfD, the checkpoint of multicellular and aggregative behaviour in Salmonella typhimurium regulates at least two independent pathways. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:10–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yildiz FH, Schoolnik GK. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4028–4033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srivastava D, Hsieh ML, Khataokar A, Neiditch MB, Waters CM. Cyclic di-GMP inhibits Vibrio cholerae motility by repressing induction of transcription and inducing extracellular polysaccharide production. Mol Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/mmi.12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gerstel U, Romling U. Oxygen tension and nutrient starvation are major signals that regulate agfD promoter activity and expression of the multicellular morphotype in Salmonella typhimurium. Environ Microbiol. 2001;3:638–648. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00235.x. *Characterized the activity of the promoter for agfD encoding a transcriptional regulator that controls expression of matrix components, in S. enterica Typhimurium in response to variable oxygen availability. In nutrient-rich medium (with abundant electron donor), promoter activity was maximized under microaerobic conditions.

- 49.White AP, Weljie AM, Apel D, Zhang P, Shaykhutdinov R, Vogel HJ, Surette MG. A global metabolic shift is linked to Salmonella multicellular development. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vlamakis H, Chai Y, Beauregard P, Losick R, Kolter R. Sticking together: building a biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:157–168. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henry JT, Crosson S. Ligand-binding PAS domains in a genomic, cellular, and structural context. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2011;65:261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huangyutitham V, Guvener ZT, Harwood CS. Subcellular clustering of the phosphorylated WspR response regulator protein stimulates its diguanylate cyclase activity. MBio. 2013;4:e00242–e00213. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00242-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmad I, Wigren E, Le Guyon S, Vekkeli S, Blanka A, El Mouali Y, Anwar N, Chuah ML, Lunsdorf H, Frank R, et al. : The EAL-like protein STM1697 regulates virulence phenotypes, motility and biofilm formation in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/mmi.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lindenberg S, Klauck G, Pesavento C, Klauck E, Hengge R. The EAL domain protein YciR acts as a trigger enzyme in a c-di-GMP signalling cascade in E. coli biofilm control. EMBO J. 2013;32:2001–2014. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]