Abstract

Objective

To evaluate prevalence, incidence, remission and persistence of psychiatric and substance use disorders among HIV-infected mothers and identify biopsychosocial correlates.

Methods

HIV-infected mothers (n=1223) of HIV-exposed uninfected children enrolled in a prospective cohort study; HIV-uninfected mothers (n=128) served as a comparison group. Mothers provided socio-demographic and health information and completed the Client Diagnostic Questionnaire (CDQ). Prevalence of any psychiatric or substance use disorder at initial evaluation was compared between the two groups. Incident, remitting and persisting disorders were identified for 689 mothers with HIV who completed follow-up CDQs. We used logistic regression to evaluate adjusted associations of biopsychosocial characteristics with presence, incidence, remission and persistence of disorders.

Results

35% of mothers screened positive for any psychiatric or substance use disorder at initial evaluation, with no difference by maternal HIV status (p=1.00). Among HIV-infected mothers, presence of any disorder was associated with younger age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.09–1.75), single parenthood (aOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.08–1.68), and functional limitations (aOR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.81–2.90). Incident disorders were associated with functional limitations (aOR, 1.92, 95% CI, 1.10–3.30). Among HIV-infected mothers with a disorder at initial evaluation (n= 238), 61% had persistent disorders. Persistent disorders were associated with lower income (aOR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.33–4.76) and functional limitations (aOR, 3.19; 95% CI, 1.87–5.48). Receipt of treatment for any disorder was limited: 4.5 % at study entry, 7% at follow-up, 5.5 % at both entry and follow-up.

Conclusions

Psychiatric and substance use disorders remain significant comorbid conditions among HIV-infected mothers and require accessible evidence-informed treatment.

Keywords: HIV, women, psychiatric disorder, substance use disorders, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

In the current era of combination antiretroviral therapy, women living with HIV (HIV-infected) have opportunities for long-term survival given adequate adherence to treatment and care. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV dramatically declined with use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy.1 Despite these advances, the HIV epidemic in women persists and their offspring are delivered with in utero HIV exposure. 2 While risk for HIV infection is increasingly associated with heterosexual transmission rather than drug use, 3 HIV continues to disproportionately affect women living in low-income, urban communities affected by substance use and violence. In addition, complications and risks associated with HIV remain, including psychiatric and substance use disorders, 4–9 that may prevent women from actualizing the full benefits of current treatment opportunities.

Risks for psychiatric and substance use disorders among HIV-infected women are related to a complex interplay of genetic, biological and psychosocial factors. Neurochemical changes during pregnancy and postpartum and HIV disease complications, including chronically activated inflammatory pathways, confer risk for depression. 10–13 HIV-infected women often have personal histories of trauma, experience acute and chronic stress, and face the challenges of managing HIV-related health problems while raising children in complex environments, often with uncertain resources and inadequate support. 14–18 Psychiatric and substance use disorders, if present, may increase the risk for inconsistent utilization of antiretroviral treatment (ART), poor adherence, inadequate virological suppression, and HIV disease progression. 19–25 Of particular concern are persistent psychiatric or substance use disorders that are undiagnosed or untreated, placing women at heightened risk for role function impairment, morbidity, and mortality. Similarly, their children may be at risk for negative developmental effects and mental health problems related to parental psychiatric illness and its effect on parenting. 26–30

In the era of ART, few studies have longitudinally examined psychiatric functioning and substance use among HIV-infected mothers. Few have focused on mothers of children who are HIV-exposed but uninfected, that is, the majority of children currently born to women living with HIV in the US. Given the ramifications of psychiatric and substance use disorders on health outcomes as well as linkage with HIV transmission behaviors, understanding the mental health needs of women in the current era may be critical for efforts to improve their health and ability to care for children, and reduce transmission to others. The goals of this investigation were to: 1) estimate the prevalence of psychiatric and substance use disorders among HIV-infected mothers of children with perinatal HIV exposure but without HIV infection, and a cohort of HIV-uninfected mothers from the same communities; 2) estimate the incidence, remission and persistence of psychiatric and substance use disorders among a subset of HIV-infected mothers with two psychiatric and substance use evaluations completed one to three years apart; and 3) identify key demographic and biopsychosocial correlates of prevalent, incident, remitted and persistent psychiatric and substance use disorders among HIV-infected mothers. We hypothesized that psychiatric disorders are more prevalent among mothers living with HIV compared to mothers without HIV infection and that disorders are more likely to persist for mothers with health limitations.

METHODS

Study Participants

Eligible participants included HIV-infected birth mothers whose children were enrolled in the Static and Dynamic cohorts of the Surveillance Monitoring for ART Toxicities (SMARTT) study, a longitudinal investigation of the biological and psychosocial effects of perinatal HIV-exposure conducted at 22 sites in the US. Sites were predominantly urban and included hospitals/clinics in Northeastern, Midwestern, Southern, and Western regions of the US and in Puerto Rico. Mothers and children attended study visits coinciding with the children’s birthdays (+/− 3 months) at 1–3, 5, 7, 9, 11 and 13 years of age from 2007–2010 and at ages 1–3, 5, 9 and 13 years of age from 2010 forward. In 2010–2011, funding became available for nine of 22 SMARTT research sites to enroll and evaluate at one study visit a community comparison group of HIV-unexposed children of ages 1, 3, 5 or 9 years and their HIV-uninfected mothers. Children and mothers were evaluated near the time of the child’s birthday.

Birth mothers in both groups completed at least one valid psychiatric and substance use evaluation, the Client Diagnostic Questionnaire (CDQ).31 Institutional review boards at participating sites approved the study; written informed consent was obtained for adult and child participation.

Outcome Measures

Psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders (SUDs) were assessed with the CDQ31, a psychiatric screening tool that was adapted from the PRIME-MD, 32 a well-validated screening tool for assessing psychiatric disorders and SUDs in primary care settings. The CDQ was developed and validated for persons affected by HIV and was administered to mothers by a psychologist, in either English or Spanish, depending on the primary language of the mother. The CDQ-based diagnosis of “any disorder” was the primary focus of this analysis, given the strong association of mental health problems and substance use among persons living with HIV, and has the strongest validity data relative to either psychiatric disorder or SUD alone, or any of the individual disorders. Sensitivity, specificity and overall accuracy of the CDQ were 91%, 78%, and 85%, respectively.31 For both groups of mothers at initial interview, we examined the prevalence of any psychiatric disorder and SUD and each specific disorder. Psychiatric disorders included major depressive disorder, other depressive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and psychosis; SUD included alcohol abuse and drug abuse. We also examined the prevalence of comorbid or co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. For HIV-infected mothers with an initial CDQ and a repeat CDQ one to three years later, we identified incident, remitting or persisting psychiatric disorders and SUDs.

Maternal health characteristics, including functional limitations (e.g. fatigue, difficulty with mobility or difficulty with work-related tasks), psychosocial information, and demographic factors of interest were collected at study entry and during follow-up through maternal interview. Maternal cognitive functioning was measured with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; 1999) 33, which provides a Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ). The WASI and CDQ were administered according to standardized procedures.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic and maternal characteristics were summarized by HIV status. CDQ and WASI evaluations were reviewed and those considered invalid were excluded from the analyses. Estimates of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and SUDs among HIV-infected mothers at each time of measurement (initial [Time 1] and follow-up at one-, two-, or three-year visits [Time 2]) and among HIV-uninfected mothers at their one interview were identified. Fisher’s exact tests and two sample t-tests were conducted as appropriate to compare prevalence of disorders between HIV-infected and uninfected mothers, using the initial CDQs completed by both groups.

HIV-infected mothers who completed CDQs at Times 1 and 2 were included in the analysis of incidence, remission and persistence of psychiatric disorders and SUDs. Summary statistics were obtained for the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and SUDs in the following categories: 1) no disorders at Time 1 or Time 2; 2) any disorder at Time 1 but none at Time 2 (remitted); 3) no disorder at Time 1 but any disorder at Time 2 (incident); and 4) any disorder at Time 1 and Time 2 (persistent). For the last category the specific disorder at each time point could differ. Using Fisher’s exact tests, two comparisons of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and SUDs were made to examine the representativeness of the sample: one with HIV-infected mothers who were ineligible for the longitudinal cohort (because they were not due for a follow-up CDQ) and one with mothers who missed their follow-up CDQ.

All valid CDQ evaluations completed by HIV-infected mothers were included to identify biopsychosocial characteristics associated with the presence of any psychiatric disorder and SUD. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were constructed to account for correlations between responses for each mother. To identify correlates of persistent and incident of psychiatric disorders and SUDs, we compared mothers with any disorder at both Time 1 and Time 2 and mothers without a disorder at Time 1 and any disorder at Time 2 to mothers with no disorder at either evaluation. Ordinary logistic regression models were fit to evaluate the associations of persistent and incident disorders with demographic and biopsychosocial correlates. To better understand correlates associated with remission and persistence of disorders, we conducted additional analyses comparing those with persistent and remitted disorders. Sensitivity analyses adjusting for site effects were conducted for all outcome analyses.

Our primary analyses were conducted using combined psychiatric disorders and SUDs as the outcome. Univariable analyses were first conducted to evaluate the unadjusted associations between the outcome and each demographic and biopsychosocial covariate. Covariates with p < 0.1 from the univariable analyses were retained in the final multivariable model to estimate the adjusted associations with psychiatric disorders and SUDs. In the multivariable models, the time interval (in months) between two CDQs was included as an a priori decision, regardless of the significance in univariable analyses. For multivariable models, missing indicators were created for covariates with > 5% missing data. Adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values were obtained from the multivariable models. Results with p<0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were based on data submitted as of January 1, 2012.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted using only psychiatric disorder (without SUD) as the outcome. Additionally, sensitivity analyses adjusting for site effect were conducted to account for potential differences in CDQ results across research site regions. The 22 research sites were grouped into four geographic regions (Puerto Rico, Northeastern/Midwestern states, Southern states, Western states) and this variable was added to the multivariable models fitted in the primary analyses. The adjusted associations of psychiatric disorder and SUD with all characteristics, after adjusting for site effect, were compared with the associations in the primary analyses.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

As of January 1, 2012, a total of 1350 HIV-infected mothers were expected to complete a CDQ. Among them, 1230 (91%) completed one or more CDQs. Reasons for missed evaluations were identified for 101 of 120 mothers and included lack of time or non-English or non-Spanish primary language and unavailable translation. Of the 1230 completed CDQs, 7 (<1%) were considered invalid, largely due to poor comprehension of questions. Thus 1223 of 1230 HIV-infected mothers (91%) were included in the analyses of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and SUDs. In addition, completed CDQs were available from 128 HIV-uninfected mothers.

Among the 1223 HIV-infected mothers with an initial CDQ, 775 were expected to complete one or more additional CDQs. Among these 775 mothers, 689 (89%) mothers completed a second CDQ within one to three years of the first interview and were included in analyses of persistence, incidence and remission of psychiatric disorders and SUD. Reasons for exclusion (n=86) included a missed follow-up CDQ (n= 52), primarily due to lack of time), or CDQ completion outside of the one-to- three year window (n=34). As compared to mothers in the longitudinal cohort for determination of incident, remitted and persistent disorders (n=689), mothers who were not eligible for the longitudinal cohort (second CDQ not expected, missed the second CDQ or completed the CDQ outside of the one-to-three year retest interval specified for these analyses; n=534) were more likely to screen positive for drug abuse disorder at study entry (p=0.02) while mothers who were expected to complete but missed the second CDQ (n=52) more often screened positive at entry for depressive disorder (p=0.03) and drug abuse disorder (p=0.03).

HIV-infected mothers were more likely to be older, of Hispanic ethnicity, and have annual household income ≤ $20,000 compared to HIV-uninfected mothers. HIV-infected mothers more often reported use of tobacco and illicit drugs during pregnancy, had more functional limitations and health problems, and had lower FSIQ scores. They were less likely to be high school graduates or currently employed than HIV-uninfected mothers (Table 1).

Prevalence of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders

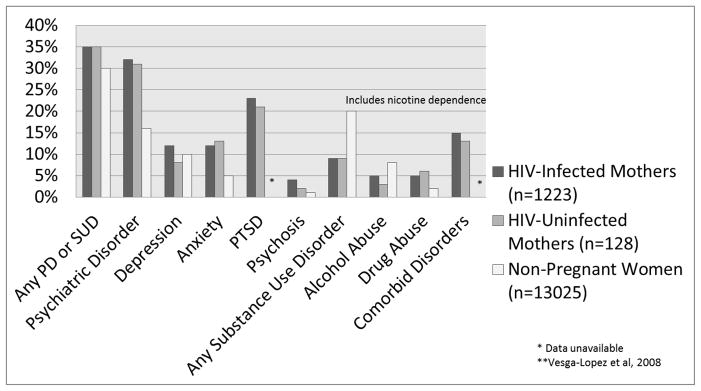

Figure 1 summarizes the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and SUDs among both groups of mothers at their initial CDQ. Thirty-five percent of both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected mothers had any disorder, including psychiatric disorder and/or SUD. Psychiatric disorders were identified among 32% of HIV-infected mothers and 31% of HIV-uninfected mothers; SUDs were identified among 9% of both groups. After adjusting for socio-demographic variables, no significant differences were observed between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected mothers for prevalence of any individual psychiatric disorder or SUD. Co-morbid psychiatric disorders and/or SUD were reported by 15% of HIV-infected mothers and 13% of HIV-uninfected mothers. Among HIV-infected mothers with SUD, 64% of mothers reported co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders (PD) and Substance Use Disorders (SUD) Among HIV-Infected Mothers, HIV-Uninfected Mothers and Non-Pregnant Women.

For HIV-infected mothers and HIV-uninfected mothers, psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders were measured by the Client Diagnostic Questionnaire,31 with primary focus on Any Disorders. Disorders evaluated by the CDQ include major depression, other depression, panic disorder, general anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis, alcohol abuse and drug abuse.

For non-pregnant women of childbearing age, all diagnoses, except psychotic disorder, were made according to the DSM-IV criteria using the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV).35 Past year diagnoses depicted in Figure 1 for non-pregnant women include Any Disorder and major depressive disorder, dysthymia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and substance use disorders, including any alcohol use disorder, any drug use disorder, and nicotine dependence. Prevalence of PTSD and comorbidity were not evaluated. See full reference for additional available diagnoses.

PTSD was the most prevalent disorder in both groups, with 23% of HIV-infected mothers and 21% of HIV-uninfected mothers meeting screening criteria at the initial CDQ. Witnessing violence (combat experience, saw people in family harming one another, saw someone assaulted/seriously injured/killed) was the most frequently reported traumatic event by both groups of mothers (SDC Table 2). HIV-infected mothers reported witnessing violence less often than HIV-uninfected mothers (44% vs. 55% p≤0.01). HIV-infected mothers had more direct personal experience with violence as they more often reported experiencing physical abuse during childhood (24% versus 14%, p =0.01) and sexual assault during adulthood (14% versus 6%, p=0.01).

Pattern of Changes in Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders Among Mothers with HIV

Table 3 shows the distribution of the pattern of changes in psychiatric disorders and SUDs among HIV-infected mothers who completed initial and follow-up CDQs. The mean interval between evaluations was 18 months. Nearly half (48%) of mothers screened positive for any psychiatric disorder or SUD at either evaluation time (Incident disorder + Remitting disorder + Persisting disorder/689). Among HIV-infected mothers with no disorder at the initial evaluation (No disorder + Incident disorder = 451), 21% (93/451) had an incident disorder during follow-up. Among mothers with disorders at their initial evaluation (Remitting disorder + Persisting disorder = 238), 61% (145/238) had persistent disorders and 39% (93/238) had remitted disorders at follow-up. Comorbid psychiatric disorders and/or SUD were reported by 23% of mothers with incident disorders and 20% with remitted disorders. Among mothers with persistent disorders, comorbid disorders were reported by 57% at Time 1 and 48% at Time 2. Seventeen percent of HIV-infected mothers reported receiving mental health treatment (medication and/or therapy) for psychiatric and/or SUD either at the time of evaluation or within the past six months: 4.5% at Time 1, 7% at Time 2, and 5.5% at both time points.

Factors Associated with Presence, Incidence and Persistence of Psychiatric Disorders and SUD among HIV-Infected Mothers

Table 4 presents the univariable and multivariable associations of demographic and biopsychosocial characteristics of interest with the presence of any current psychiatric disorder or SUD among HIV-infected mothers. In the multivariable model, mothers who were younger than 35 years, single parents, and those who had one or more functional limitations had higher odds of screening positive for any disorder, compared to mothers without those characteristics. Not surprisingly, mothers who self-reported alcohol or illicit substance use during pregnancy also had higher odds of screening positive for any current psychiatric disorder or SUD. However, sensitivity analyses conducted to identify factors associated with the presence of psychiatric disorders only (excluding SUD) among women with HIV infection at study entry (n=1223) revealed that the use of illicit substance during pregnancy (p=0.04) was significantly associated with the presence of any current psychiatric disorder.

As shown in SDC Table 5, mothers who reported 1–2 functional limitations as compared to no limitations had higher odds of incident disorders (vs. no disorders at either time point). Lower annual household income and one or more functional limitations were associated with higher odds of persistent disorders (vs. no disorders at either time point), as were alcohol or illicit substance use during pregnancy. When comparing mothers with persistent and remitted disorders, no significant associations were observed with demographic or psychosocial characteristics, although the presence of multiple functional limitations, lower income and illicit substance use during pregnancy were marginally associated with persistent disorders (data not shown).

Sensitivity analyses to identify correlates of persistent psychiatric disorders only (excluding SUD) in the longitudinal analyses revealed that using alcohol during pregnancy (p=0.01) was associated with higher odds of persistent psychiatric disorders. Additionally, mothers with one or two functional limitations at the time of the initial evaluation more often developed a new psychiatric disorder than mothers who had no functional limitation. Including research site in the adjusted models had no effect on the findings observed in the primary analyses.

DISCUSSION

Psychiatric and substance use disorders among mothers with HIV infection are of great concern due to their impact on mothers’ own health and quality of life, as well as the health and psychological well-being of their children. In our investigation, psychiatric and substance use disorders among HIV-infected mothers were more prevalent than among adults in general and non-pregnant women in large scale US population surveys 34,35, but rates were similar to those observed among our comparison group of HIV-uninfected mothers recruited from the same medical centers. Among all diagnostic categories assessed in this study, PTSD was the most prevalent disorder for both HIV-infected (23%) and HIV-uninfected mothers (21%), with notably higher rates than those observed in the general adult population (9.7%) 34 but similar to estimates in previous studies of US HIV-infected women. 16

Our results indicate that almost half of mothers living with HIV in this longitudinal sample had a psychiatric or substance use disorder at some time during the period of study. Further, psychiatric or substance use disorders persist among many mothers; 61% of mothers with disorders at the initial evaluation presented with a disorder at both time points, although the specific disorder may have changed. More than half of mothers with persistent disorders had comorbid disorders at their initial evaluation, especially PTSD, anxiety and depression, in varying combinations, which may adversely affect adherence and retention in HIV care and contribute to the persistence of disorders. Of additional concern, among mothers with no disorders at their initial evaluation, 21% experienced an incident disorder, which underscores the dynamic nature of psychiatric conditions and the need for ongoing screening and evaluation and provision of easily accessible services.

A number of biopsychosocial characteristics were associated with prevalent, incident and persistent psychiatric and substance use disorders in mothers with HIV infection. Mothers who were younger or single parents were more likely to have a disorder and mothers with lower family income were more likely to have persistent disorders compared to those with no disorder. Functional limitations, such as fatigue and difficulty with mobility or work-related tasks, were also strongly associated with prevalent, persistent and incident disorders, regardless of whether psychiatric disorders were examined independently or in conjunction with substance use disorders. Although we were unable to ascertain whether functional limitations were due to complications of HIV, the debilitating effects of either psychiatric and/or substance abuse disorders, or their interaction, prior research suggests that functional limitations predict negative affect, 17 possibly due to individuals’ difficulty meeting home and occupational demands and other associated stressors. The presence of functional limitations was the single factor that distinguished mothers with incident disorders from those who had no disorders during follow-up; similarly, the presence of functional limitations was marginally related to the presence of persistent disorders versus remitted disorders during follow-up.

Mothers in our cohort experienced high rates of trauma. Compared to HIV-uninfected mothers, mothers with HIV infection were more likely to report physical abuse during childhood and sexual assault during adulthood, while those without HIV were more likely to have witnessed violence. Although type of trauma was not the primary outcome of interest in this study, these significant differences are noteworthy. Both sexual trauma (which is interpersonal and deeply intimate by nature) and childhood physical abuse (which is often perpetrated by a parent or family member who is simultaneously considered a source of safety or a primary attachment figure) may be more likely to affect victims’ self-esteem, emotional regulation and ability to form healthy relationships.36 Physical abuse in early childhood may also alter brain responses to mild or high stress in adulthood 37 and may predispose adults with this history to mental health problems as well as elevated adult sexual risk behavior. Similarly, in the context of multiple risk factors and chronic illness among mothers with HIV infection, the experience of sexual assault in adulthood may further compromise self-care, health management, and health outcomes. 16, 38 Trauma recovery services may be particularly helpful to women with such histories to prevent recurrence of victimization and reduce the risk of intergenerational trauma in their family systems. 39,40

Maternal histories of alcohol or illicit substance use during pregnancy were relatively infrequent (10%) but not absent in this study. While previous analyses of a smaller cohort of HIV-infected mothers from this cohort 41 suggested that self-report of substance use in pregnancy was fairly reliable, it remains possible that some mothers underreported substance use, due to social desirability bias or mothers’ concerns about reports to child protective services. Still, this finding suggests that maternal report of alcohol or illicit substance use during pregnancy may have value in predicting SUD prevalence and persistence, and, if this finding is confirmed by future studies, have clinical value in identifying women who are at particularly high risk and need additional or more intensive mental health follow-up.

In spite of high rates of disorders observed in this study, we found low utilization of mental health services and substance use treatment for those in need, even among mothers with persistent disorders. Psychiatric and substance use disorders, if left untreated, may exacerbate mothers’ health problems and prevent adequate health-promoting behavior while treatment or recovery may provoke parallel improvement in specific indicators of immunity.20 Referrals for appropriate intervention were standard of care at all study sites. In light of limited reported treatment, however, we speculate that stigma associated with HIV and/or mental health and substance use treatment, as well as practical and structural barriers (e.g., cost, lack of transportation or childcare, inflexible work hours) or cultural factors (e.g., language differences and level of acculturation) may be critical limitations to utilization of appropriate mental health services or substance use treatment. More research is needed to understand the low rates of service use among women of childbearing age and among women living with HIV specifically and to develop interventions and policies to promote participation. Moreover, multiple studies have now recommended integrated HIV, mental health and substance use treatment, as women living with HIV may be more likely to initiate and maintain mental health services and/or substance abuse treatment if these services were included in their routine medical care. 6, 42, 43

This investigation is one of the largest studies to date to examine longitudinal data on mothers with HIV in the era of ART. It is, however, not without limitations. Although the demographic characteristics of our study cohort were representative of the US population of mothers with HIV, the fact that both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected mothers were from convenience samples introduces enrollment bias, which potentially limits our ability to generalize the findings to all mothers with HIV. Our comparison group of HIV-uninfected mothers was evaluated only once, due to funding limitations, precluding identification of incident, remitted and persistent disorders and thus the potential impact of HIV on women’s psychological health. Given the primary focus of SMARTT on child outcomes, detailed information on the past psychiatric and HIV disease histories of the mothers was unavailable and thus we could not evaluate potential confounding factors, such as maternal nadir CD4 count or treatment history. Finally, although the CDQ is validated for identifying psychiatric and substance use disorders in primary care settings and among those affected by HIV, it is a screening instrument and insufficient for definitive clinical diagnoses, including diagnosis of bipolar disorder or anti-social personality disorder, which sometimes co-occur with substance use disorders.

Nonetheless, the results of this study have important implications for programs and policy. Systematic screening, diagnosis and early treatment of psychiatric and substance use disorders should be key components of comprehensive HIV care for women, with periodic re-assessment for those at highest risk, such as younger mothers, those with limited resources and those with functional limitations. Access to evidence-informed treatment for psychiatric and substance use disorders, as well as trauma recovery might be essential to preempt the development or escalation of mental illness and its consequences for mothers and their families. The psychological, societal, cultural and institutional barriers to access mental health care must be identified and eliminated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING:

The Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with co-funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Office of AIDS Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard University School of Public Health (HD052102, 3 U01 HD052102-05S1, 3 U01 HD052102-06S3) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (HD052104, 3U01HD052104-06S1). This project was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health.

We thank the children and families for their participation in PHACS, and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of PHACS. The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with co-funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Office of AIDS Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard University School of Public Health (HD052102, 3 U01 HD052102-05S1, 3 U01 HD052102-06S3) (Principal Investigator: George Seage; Project Director: Julie Alperen) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (HD052104, 3U01HD052104-06S1) (Principal Investigator: Russell Van Dyke; Co-Principal Investigator: Kenneth Rich; Project Director: Patrick Davis). Data management services were provided by Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation (PI: Suzanne Siminski), and regulatory services and logistical support were provided by Westat, Inc (PI: Julie Davidson).

The following institutions, clinical site investigators and staff participated in conducting PHACS SMARTT in 2012, in alphabetical order: Baylor College of Medicine: William Shearer, Mary Paul, Norma Cooper, Lynette Harris; Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center: Murli Purswani, Emma Stuard, Anna Cintron; Children’s Diagnostic & Treatment Center: Ana Puga, Dia Cooley, Patricia Garvie, Deyana Leon; Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago: Ram Yogev, Margaret Ann Sanders, Kathleen Malee, Scott Hunter; New York University School of Medicine: William Borkowsky, Sandra Deygoo, Helen Rozelman; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital: Katherine Knapp, Kim Allison, Megan Wilkins; San Juan Hospital/Department of Pediatrics: Midnela Acevedo-Flores, Lourdes Angeli-Nieves, Vivian Olivera; SUNY Downstate Medical Center: Hermann Mendez, Ava Dennie, Susan Bewley; Tulane University Health Sciences Center: Russell Van Dyke, Karen Craig, Patricia Sirois; University of Alabama, Birmingham: Marilyn Crain, Newana Beatty, Dan Marullo; University of California, San Diego: Stephen Spector, Jean Manning, Sharon Nichols; University of Colorado Denver Health Sciences Center: Elizabeth McFarland, Emily Barr, Robin McEvoy; University of Florida/Jacksonville: Mobeen Rathore, Kristi Stowers, Ann Usitalo; University of Illinois, Chicago: Kenneth Rich, Lourdes Richardson, Delmyra Turpin, Renee Smith; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey: Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica, Susan Adubato; University of Miami: Gwendolyn Scott, Claudia Florez, Elizabeth Willen; University of Southern California: Toinette Frederick, Mariam Davtyan, Maribel Mejia; University of Puerto Rico Medical Center: Zoe Rodriguez, Ibet Heyer, Nydia Scalley Trifilio.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 3rd International Conference on HIV & Women, 2013, Toronto, Canada, Session 2, Abstract O_06.

Note: The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J of Med. 1994;331:1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411033311801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitmore S, Zhang X, Taylor AW, et al. Estimated number of infants born to HIV-infected women in the United States and five dependent areas, 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:218–222. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182167dec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2012. 2012 Dec;17(4) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/#supplemental. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellins CA, Ehrhardt AA, Grant WF. Psychiatric symptomatology and psychological functioning in HIV-infected mothers. AIDS Behav. 1997;1(4):233–245. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellins CA, Ehrhardt AA, Rapkin B, Havens J. Psychosocial factors associated with adaptation in HIV-infected mothers. AIDS Behav. 2000;4(4):317–328. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellins CA, Kang E, Leu CS, et al. Longitudinal study of mental health and psychosocial predictors of medical treatment adherence in mothers with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17:407–416. doi: 10.1089/108729103322277420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapetanovic S, Christensen S, Karim R, et al. Correlates of perinatal depression in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(2):101–108. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Ten Have T, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor ER, Amodei N, Mangos R. The presence of psychiatric disorders in HIV-infected women. Journal Counseling Dev. 1996;74:345–351. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(2):153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depression and immune function: Central pathways to morbidity and mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):873–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longone P, Rupprecht R, Manieri GA, et al. The complex roles of neurosteroids in depression and anxiety disorders. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyer TP, Stein JA, Rice E, et al. Predicting depression in mothers with and without HIV: The role of social support and family dynamics. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2198–2208. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0149-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leenerts MH. The disconnected self: Consequences of abuse in a cohort of low-income white women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Care Women Int. 1999;20(4):381–400. doi: 10.1080/073993399245674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machtinger EL, Wilson TC, Haberer JE, et al. Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: A meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2091–2100. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIntosh RC, Rosselli M. Stress and coping in women living with HIV: A meta-analytic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2144–2159. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Loeb TB. Women, trauma and HIV: An overview. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(4):401–403. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chander G, Himelhoch S, Moore RD. Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in HIV-positive patients: Epidemiology and impact on antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2006;66:769–789. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruess DG, Douglas SD, Petitto JM, et al. Association of resolution of major depression with increased natural killer cell activity among HIV-seropositive women. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2125–2130. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neblett RC, Hutton HE, Lau B, et al. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected women: Impact on time to antiretroviral therapy and survival. J Womens Health. 2011;20:279–286. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pence BW. The impact of mental health and traumatic life experiences on antiretroviral treatment outcomes for people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:636–640. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petry N. Alcohol use in HIV patients: What we don’t know may hurt us. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10:561–570. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. The impact of DSM-IV mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2119–2143. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0212-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001;285(11):1466–1474. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Havens JF, Mellins CA. Psychiatric aspects of HIVAIDS in childhood and adolescence. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry. 5. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2008. p. 945. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonard NR, Gwadza MV, Clelanda CM, et al. Maternal substance use and HIV status: Adolescent risk and resilience. J Adolescence. 2008;31:389–405. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malee KM, Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, et al. Mental health functioning among children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection and perinatal HIV exposure. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1533–1544. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.575120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, et al. Mental health of early adolescents from high-risk neighborhoods: The role of maternal HIV and other contextual, self-regulation, and family factors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33 (10):1065–1075. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staroselsky A, Fantus E, Sussman R, et al. Both parental psychopathology and prenatal maternal alcohol dependency can predict the behavioral phenotype in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11 (1):22–25. doi: 10.2165/0148581-200911010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aidala A, Havens J, Mellins CA, et al. Development and validation of the Client Diagnostic Questionnaire (CDQ): A mental health screening tool for use in HIV/AIDS service settings. Psychol Health Med. 2004;9:362–380. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282 (18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity and comorbidity of 12 month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen JG. Traumatic relationships and serious mental disorders. Chichester/New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banihashemi L, Sheu LK, Gianaros PJ. Childhood physical abuse correlates with adulthood hypothalamic and limbic forebrain activity and connectivity in response to psychological stress. Presented at: Society for Neuroscience; 2012; New Orleans. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leserman J, Pence BW, Whetten K, et al. Relation of lifetime trauma and depressive symptoms to mortality in HIV. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1707–1713. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hien DA, Campbell AN, Killeen T, et al. The impact of trauma-focused group therapy upon HIV sexual risk behaviors in the NIDA clinical trials network “women and trauma” multi-site study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):421–430. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9573-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyatt GE, Longshore D, Chin D, et al. The efficacy of an integrated risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive women with child sexual abuse histories. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(4):453–462. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tassiopoulos K, Read J, Brogly S, et al. Substance use in HIV-infected women during pregnancy: Self-report versus meconium analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14 (6):1269–1278. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9705-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dillard D, Bincsik A, Zebley C, et al. Integrated nested services: Delaware’s experience treating minority substance abusers at risk for HIV or HIV positive. J Evid-Based Soc Work. 2010;7(1–2):130–143. doi: 10.1080/15433710903176021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Long-Term-Services-and-Support/Integrating-Care/Health-Homes/Health-Homes.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.