Abstract

Background

Recent randomised controlled trials have examined the issue of when to start antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis (TB). There is, however, little information on the effect of timing of antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation on outcomes in real-life, non-clinical trial, rural settings in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

We conducted an observational cohort study of all HIV-infected TB patients presenting to a rural hospital in Kenya between 2005 and 2009. We analysed the association between timing of initiation of ART and mortality, using a Cox regression survival analysis, adjusted for measured confounders.

Results

404 antiretroviral-naïve HIV/TB co-infected patients were included in the study. Initiation of ART during the first 8 weeks of TB treatment (early group) was not associated with changes in mortality at one year compared to those who initiated ART after 8 weeks (late group) [Hazard Ratio (HR) = 0.74 (Confidence Interval (CI) 0.33 – 1.64, p=0.46]. In those with baseline CD4 counts ≤50 cells/μl, there was a significant reduction in mortality in the early group compared to the late group (HR= 0.20, 95% CI 0.042 - 0.99, p=0.049). In patients with a CD4 count >50 cells/μl there was no significant difference between early and late groups (HR 1.79 95% CI 0.64- 5.03, P=0.27)

Conclusions

We found that in HIV/TB co-infected patients in rural Kenya, early ART initiation (within 8 weeks) was associated with reduced mortality in those with CD4 counts ≤50 cells/μl. In patients with CD4 counts >50 cells/μl there was no association seen between timing of ART and mortality.

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has had a devastating effect on the tuberculosis (TB) epidemic, fuelling its transmission and causing higher rates of morbidity and mortality. (Lawn and Churchyard 2009; World Health Organisation 2010b) TB is the most common opportunistic infection and cause of death in people infected with HIV in this setting. (Cohen and Meintjes 2010; Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2006; Kyeyune et al. 2010) Kenya is one of the 22 high-burden countries in the world for tuberculosis, with an annual incidence of 305 per 100,000 population per year. (World Health Organisation 2010a) Forty-four percent of TB patients in Kenya were estimated to be infected with HIV in 2010. (World Health Organisation 2010a)

The optimal time to initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART) in patients with HIV-associated tuberculosis has been a subject of intense debate. Concerns about early initiation of ART include a high pill burden, pharmacological interactions, overlapping toxicities and the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Conversely, delayed initiation of ART may be associated with HIV disease progression and death. (Lawn and Churchyard 2009) Previous retrospective studies (Manosuthi et al. 2006; Velasco et al. 2009) and a randomised trial showed that delaying ART initiation until after completion of TB therapy was associated with increased mortality. (S. S. Abdool Karim et al. 2010) More recently, three randomised controlled trials (RCT) have demonstrated a survival benefit of early initiation of ART (two to four weeks into TB therapy) in patients with a baseline CD4 count less than 50 cells/μl, compared with delayed initiation. (S. S. Abdool Karim et al. 2011; Blanc et al. 2011; Havlir et al. 2011) A fourth RCT conducted in patients with HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis, showed no evidence of benefit of early ART initiation. (M Estee Török et al. 2011)

Both trials that included patients from sub-Saharan Africa were based in well-resourced teaching hospitals in urban centres. The majority of HIV-infected TB patients reside in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa where laboratory diagnostic facilities are limited, and TB diagnosis is clinical. The aim of this study was therefore to explore the relationship between the timing of ART initiation and outcome in HIV-infected TB patients in a typical rural sub-Saharan Africa setting.

Methods

Study setting and participants

We performed an observational cohort study based on data from the registers of the Tuberculosis Clinic and the HIV clinic managed by AIDS Relief at PCEA Chogoria Hospital, a rural mission hospital in Eastern Province, Kenya. TB treatment clinic data were recorded in a standardised Kenyan Ministry of Health TB treatment register and HIV clinic data were recorded electronically in a computerised database at each patient visit. Data were collected for the period between 1 January 2005 and 31 October 2009. Patients were included if they had completed tuberculosis treatment by the end date of the study (31 October 2009) or had an alternative outcome, such as death or loss to follow-up, recorded.

Clinical procedures

Patients with TB were diagnosed and treated free of charge through the programme of the Kenya Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Other Lung Diseases. (Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2009) At least two sputum samples from spontaneous expectoration were tested for acid-fast bacilli using Ziehl-Nielsen staining and microscopy. Mycobacterial culture and drug susceptibility testing were not available, apart from in re-treatment cases whose sputum samples were sent to the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory. The majority of patients underwent chest radiography and the decision to start TB treatment was at the discretion of the hospital doctors, based on national guidelines. (Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2009) The diagnosis of sputum smear-negative pulmonary TB was based on a history of cough of two weeks or longer, fever or weight loss and compatible radiological features. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis was diagnosed on the basis of a history of weight loss, night sweats or persistent fever with pleural or pericardial effusion, miliary appearance on radiographs, lymphadenopathy, chronic lymphocytic meningitis, ascites or radiographic bone abnormalities. Access to mycobacterial culture was extremely limited and did not influence the decision to treat. In most cases treatment was empirical and based upon clinical suspicion without diagnostic confirmation.

The treatment regimen was rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for 2 months (intensive phase) followed by rifampicin and isoniazid for 4 months (continuation phase) in accordance with national TB treatment guidelines.

HIV infection status was determined using a rapid diagnostic test and positive results were confirmed using a second test, in accordance with national HIV guidelines. From 2006, the Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Other Lung Diseases in Kenya advised that all patients attending clinics which administer TB chemotherapy should be tested for HIV infection using an opt-out approach. (Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2006)

The HIV clinic provided co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and multivitamins free-of-charge to all HIV-infected patients enrolled into the programme, regardless of CD4 count. ART was also provided free-of-charge to all patients who met the immunological and psychological criteria for initiation. Immunological criteria included World Health Organization HIV stage 3 or 4 disease, or stage 1 or 2 disease if the CD4 count was <250 cells/μl. Psychological criteria included demonstration of sufficient understanding, psychological preparedness, and capacity for adherence. The ART regimen was stavudine or zidovudine plus lamivudine and efavirenz. CD4 counts were monitored 6-monthly and plasma HIV viral load testing was not available during the course of the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 17 (2008). Categorical variables were tested using the Fisher exact test, and continuous variables using the independent samples Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate, to determine differences in patient demographics based on HIV testing status, outcomes, the decision to start ART or timing of ART initiation.

Survival times were evaluated using a proportional hazards regression model adjusted for measured covariates using the Cox regression survival function. Outcomes were restricted to a period of one year from commencement of TB treatment. Patients were divided into three groups according to timing of initiation of ART in relation to TB treatment: “early” meaning starting ART within 8 weeks of commencing TB treatment, “late” meaning starting ART later than 8 weeks but within one year and “not started” meaning ART was not started within one year of starting TB treatment. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to adjust for seven variables: date of initiation of TB treatment; age; gender; baseline CD4 count; type of TB (smear-positive or smear-negative, pulmonary or extra-pulmonary); type of patient (new, retreatment or transfer in); and ART timing treatment group (as described above). Patients were analysed in two subgroups according to their baseline CD4 count at the start of TB treatment: ≤50 cells/μl or >50 cells/μl.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Hospital Administration Team of Presbyterian Church of East Africa Chogoria Hospital which is the ethical review board for the hospital. The study was conducted as service evaluation of the TB clinic and individual patient consent for participation in the study was therefore not required.

Results

Between 1 January 2005 and 31 October 2009, 1,729 patients were treated for tuberculosis at the hospital clinic. HIV testing was performed in 1,247 patients (72.1%), of whom 849 (49.1% of total, 68.1% of those tested) were HIV-infected.

The proportion of patients tested for HIV infection rose significantly during the study period from 362/688 (52.6%, 95% CI 48.8% - 56.4%) in 2005 to 192/204 (94.1%, 95% CI 90.0% - 96.9%, p<0.001) in 2009, whilst the proportion of those tested who were HIV positive fell from 307/362 (84.8%, 95% CI 80.7% - 88.3%) to 91/192 (47.4%, 95% CI 40.2% - 54.7%, p<0.001). Females were more likely to be tested for HIV infection (618/788, 78.4%) compared to males (627/939, 66.8%) relative risk (RR) = 1.18 (95% CI 1.11 - 1.25, p<0.001).

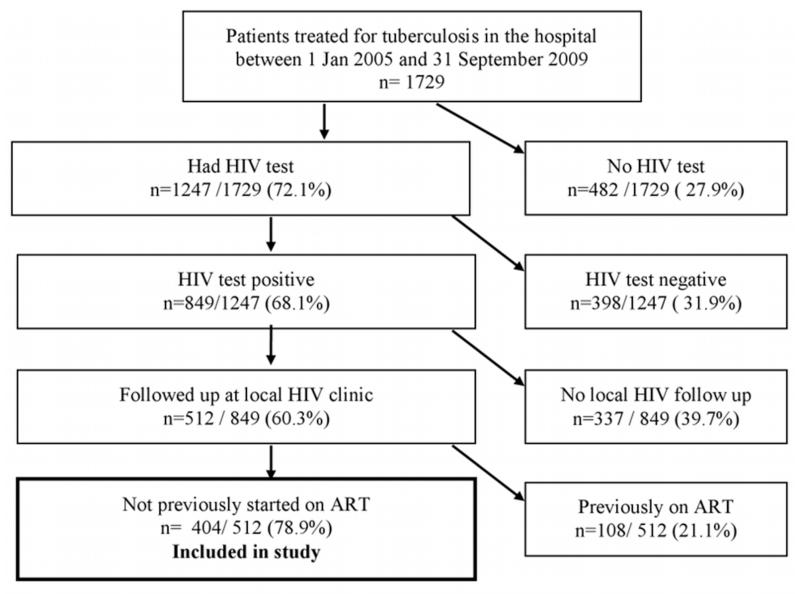

The flow of patients through the study is shown in Figure 1. 849 patients were identified as HIV/TB co-infected. 404 antiretroviral-naïve HIV/TB co-infected patients were followed up at the local HIV clinic and included in the study.

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients included in study according to inclusion criteria.

The baseline characteristics of the 404 participants and association with ART are shown in Table 1. During the study follow-up period, 314 (77.7%) patients were treated with ART and 90 patients did not receive ART. ART was significantly associated with CD4 count at the start of TB treatment: median 111 cells/μl (IQR 42 - 261 cells/μl) in those treated with ART versus 203 cells/μl (IQR 30 – 538 cells/μl) in those not treated (p=0.023). There was no significant association between ART and age, gender, type of TB, or type of patient (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and association with antiretroviral therapy in included patients.

| n (%) | Treated with ART: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early (<8 weeks) | Late (>8 weeks) | Not started (at one year) | p-value | ||

| Total | 404 | 122 | 156 | 126 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median age (Interquartile range) | 32.0 (24.0 – 39.8) | 34.5 (28.0 – 41.3) | 31.0 (23.0 – 40.0) | 30.0 (20.0- 36.0) | 0.003 |

| <18 18-30 31-50 >50 |

77 (19.1) 110 (27.2) 181 (44.8) 36 ( 8.9) |

17 ( 13.9) 24 (19.7) 70 (57.4) 11 (9.0) |

31 (19.9) 46 (29.5) 67 (42.9) 12 (7.7) |

29 (23.0) 40 (31.7) 54 (42.9) 3 (2.4) |

0.395 |

| CD4 count at start of TB treatment † | |||||

| Median CD4 (Interquartile range) | 122 (41- 295) | 92 (30 – 172) | 130 (48-277) | 241 (41 – 476)) | <0.001 |

| <= 50 51-200 201-350 > 350 |

107 (29.6) 122 (33.7) 59 (16.3) 74 (20.4) |

42 (35.9) 52 (44.4) 16 (13.7) 7 (6.0) |

38 (26.4) 50 (24.7) 30 (20.8) 26 (18.1) |

27 (26.7) 20 (19.8) 13 (12.9) 41 (40.6) |

<0.001 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male Female |

192 (47.5) 212 (52.5) |

60 (49.2) 62 (50.8) |

73 (46.8) 83 (53.2) |

59 (46.8) 67 (53.2) |

0.92 |

| Type of TB | |||||

| Smear positive pulmonary Smear negative pulmonary Extrapulmonary |

83 (20.5) 285 (70.5) 36 ( 8.9) |

20 (16.4) 93 (76.2) 10 (7.4) |

31 (19.9) 108 (69.2) 17 (10.9) |

32 (25.4) 84 (66.7) 10 (7.9) |

0.281 |

| Type of Patient ‡ | |||||

| New patient Retreatment Transfer in |

338 (83.7) 54 (13.4) 10 ( 2.5) |

101 (82.8) 15 (12.3) 5 (4.1) |

128 (82.1) 24 (15.4) 4 (2.6) |

109 (86.5) 15 (11.9) 1 (0.8) |

0.490 |

not recorded for 42 patients

not recorded for 2 patients

Outcomes were significantly worse in those who did not receive ART; mortality was three times greater at one and three years, and there was a significantly greater loss to follow-up (Table 2). In a univariate analysis, mortality was associated with smear positivity (mortality at three years 34.3% for smear-positive disease versus 19.3% for smear-negative, p=0.013) and CD4 count at ART initiation (mortality at three years 26.2% for CD4 count ≤50 cells/μl versus 12.2% for CD4 count >50 cells/μl, p=0.002). There was no association with age, gender, or proportion of re-treatment cases.

Table 2. Relationship between antiretroviral therapy and treatment outcomes in HIV-infected TB patients.

| Time since starting TB treatment | Outcomes (%) | Treated with ART? | Patients treated with ART vs. patients not treated with ART | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Total | 314 | 90 | |||

| One year |

Outcome known† Remaining under follow up‡ Died Transferred out Lost to follow up Stopped ART |

297 (95.2) 247 (83.2) 30 (10.1) 13 ( 4.4) 5 ( 1.7) 2 ( 0.7) |

86 (95.6) 41 (47.7) 29 (33.7) 13 (15.1) 3 ( 3.5) - |

0.57 ( 0.46 – 0.72) 3.34 ( 2.13 – 5.24) 3.45 ( 1.66 – 7.17) 2.07 ( 0.51 – 8.50) - |

<0.001 <0.001 0.001 0.386 |

| Two years |

Outcome known† Remaining under follow up‡ Died Transferred out Lost to follow up Stopped ART |

276 (87.9) 208 (75.4) 36 (13.0) 19 ( 6.9) 11 ( 4.0) 2 ( 0.7) |

79 (87.8) 22 (27.8) 30 (38.0) 18 (22.8) 9 (11.4) - |

0.37 ( 0.26 – 0.53) 2.91 ( 1.92 – 4.41) 3.31 ( 1.83 – 6.00) 2.86 ( 1.23 – 6.65) - |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.023 |

| Three years |

Outcome known† Remaining under follow up‡ Died Transferred out Lost to follow up Stopped ART |

241 (76.8) 159 (66.0) 40 (16.6) 24 ( 10.0) 13 ( 5.4) 5 ( 2.1) |

75 (83.3) 15 (20.0) 31 (41.3) 19 ( 25.3) 10 ( 13.3) - |

0.30 ( 0.19 – 0.48) 2.49 ( 1.69 – 3.68) 2.54 ( 1.48 – 4.38) 2.47 ( 1.13 – 5.41) - |

<0.001 <0.001 0.002 0.038 |

Outcome known = Number of patients at the given time period for whom the outcome is known according to duration of follow up. Follow up ranged from 6 months to five years, depending on time of entry to study.

Remaining under follow up= Continuing to attend regular HIV clinics

The 404 patients were divided into three categories: the early group [n = 122, median time to ART initiation = 42 days (IQR 25 - 55 days)]; the late group [n = 156, median time to ART initiation = 116 days (IQR 81 - 210 days)]; and the not started group.

Earlier initiation of ART was associated with increased age: early group median age 34.5 (IQR= 28.0 – 41.3) years; late group median age 31.0 (IQR = 23.0 – 40.0) years, p=0.023. Patients who started ART earlier also had significantly lower CD4 counts at the start of TB treatment: early group median CD4 count 92 cells/μl (IQR 30 - 172 cells/μl); late group median CD4 count 130 cells/μl (IQR 48 - 277 cells/μl) , p=0.006. There was no association with year, gender, type of TB, or type of patient as seen in Table 1.

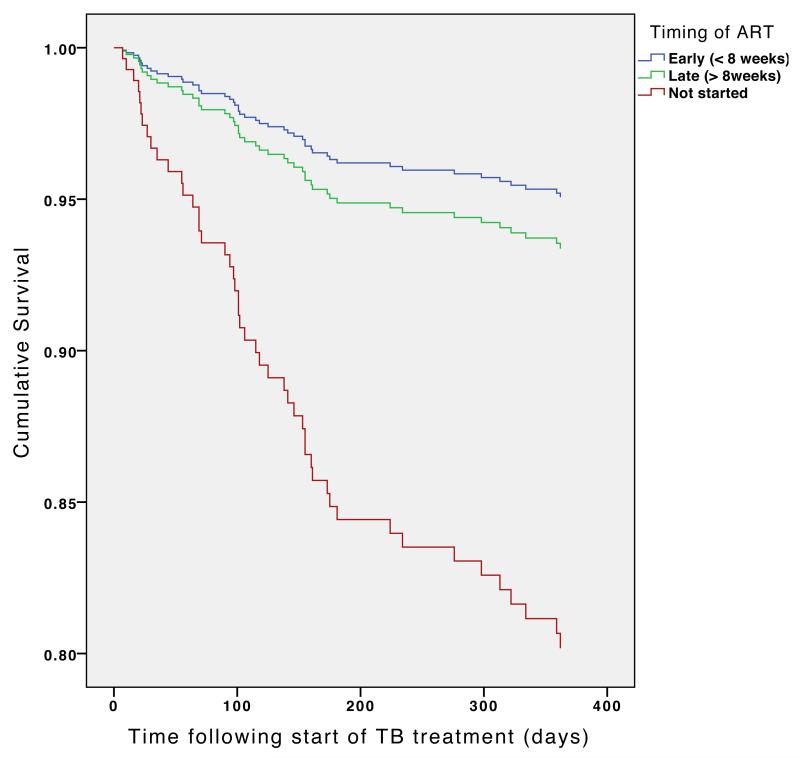

In a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, there was no difference in mortality at one year between the early and late groups, Hazard Ratio (HR) 0.74 (95% CI 0.33 – 1.64, p=0.46) (Figure 2). However, mortality at one year was significantly lower in patients who received ART compared to those who did not (HR = 0.14, 95% CI 0.078-0.26 , p<0.001).

Figure 2. Cox regression survival curve: timing of antiretroviral therapy in relation to TB treatment.

Curves are adjusted for date of commencing TB treatment, age, gender, type of TB (pulmonary smear positive or smear negative or extrapulmonary), type of patient (new, retreatment or transfer in) and baseline CD4 count.

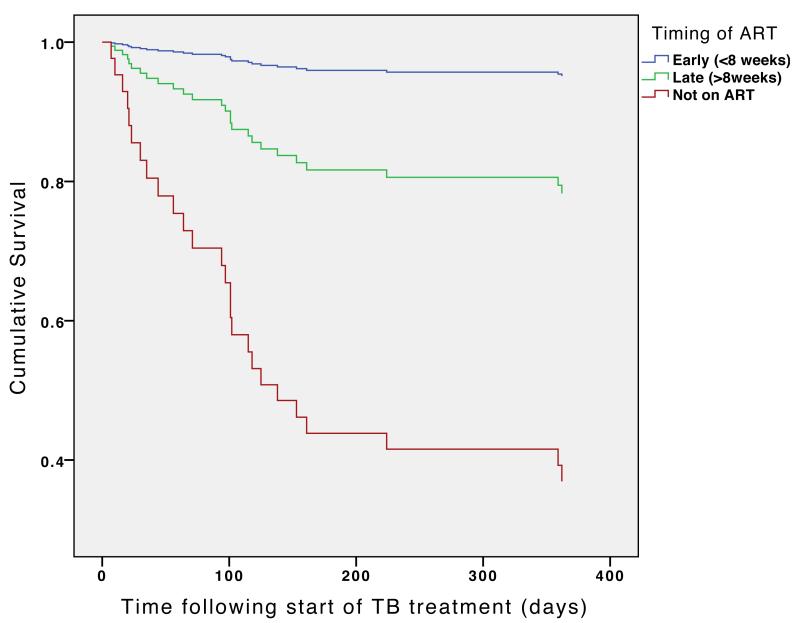

In patients with a baseline CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mm3, there was a significant reduction in mortality in the early group compared to the late group (HR=0.20, 95% CI 0.042 - 0.99, p=0.049). Those who received ART in the early group had a 95% absolute reduction in mortality compared to those who did not receive ART within one year. (HR 0.050, 95% CI 0.011 – 0.22, P<0.0001), (Figure 3A).

Figure 3A. Cox regression survival curve: timing of antiretroviral therapy in relation to TB treatment according to CD4 count at baseline.

Patients with baseline CD4 count ≤50 cells/ul

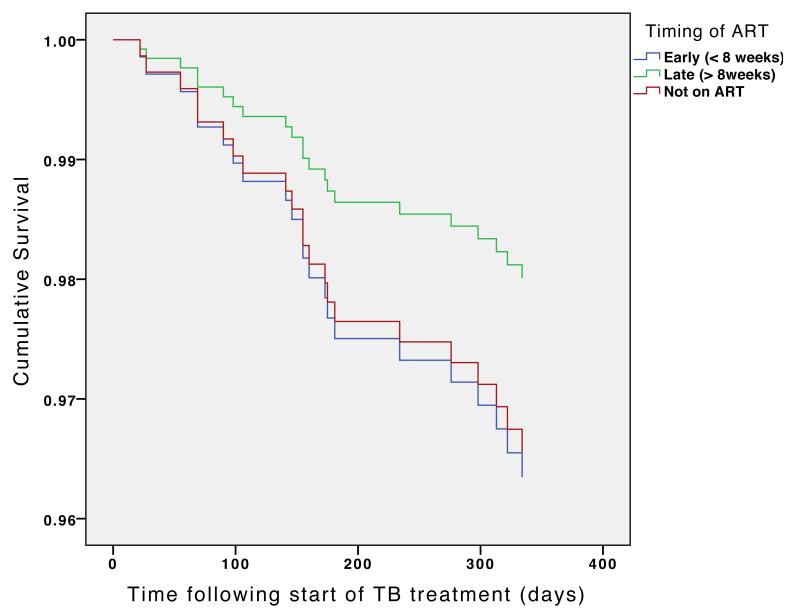

Figure 3B. Cox regression survival curve: timing of antiretroviral therapy in relation to TB treatment according to CD4 count at baseline.

Patients with baseline CD4 count >50 cells/ul

Curves are adjusted for date of commencing TB treatment, age, gender, type of TB (pulmonary smear positive or smear negative or extrapulmonary), type of patient (new, retreatment or transfer in) and baseline CD4 count.

† P values in figures refer to the difference between the early and late groups

In patients with a baseline CD4 count of over 50 cells/mm3, there was no significant difference between the early and late groups (HR 1.79 95% CI 0.64- 5.03, P=0.27) nor between early and not started groups (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.33 - 3.38, P=0.92)

Discussion

Four randomised controlled trials have examined the question of the optimal timing of antiretroviral therapy in HIV/TB co-infected patients. In 2010, the SAPIT trial from South Africa reported preliminary data showing a relative reduction of mortality of 56% (HR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.25 – 0.79, p=0.003) in patients starting ART during TB treatment (integrated therapy arm) compared to patients starting within 4 weeks of completion of TB treatment (sequential therapy arm). (S. S. Abdool Karim et al. 2010) This accords with previous observational data from Spain (Velasco et al. 2009) and Thailand (Manosuthi et al. 2006) that reported increased mortality in people deferring ART until the completion of TB treatment, and an observational study in children from South Africa suggesting increased mortality in those who started ART later than two months in TB treatment. (Yotebieng et al. 2010) The final analysis of the SAPIT trial demonstrated no overall difference in the primary endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death between the early integrated therapy arm (ART commenced <4 weeks of TB treatment) and late integrated therapy arm (ART commenced <4 weeks after completing intensive TB treatment). (S. S. Abdool Karim et al. 2011)

A second international multicentre RCT, the ACTG 5221 study, reported that immediate ART (<2 weeks) did not reduce the primary endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death compared with early ART (8 to 12 weeks). (Havlir et al. 2011) However, both studies found that in patients with baseline CD4 counts <50 cells/μl, early ART initiation was associated with a significant reduction in AIDS or death.

A third RCT, the CAMELIA trial conducted in Cambodia reported improved survival in predominantly pulmonary TB patients initiating ART at 2 weeks compared with 8 weeks. (Blanc et al. 2011) The median CD4 count was 25 cells/μl (IQR 10 - 56 cells/μl), which significantly lower than the other two studies, and may account for these findings.

In contrast, a Vietnamese RCT of immediate (within 7 days of TB treatment) versus deferred (after 8 weeks TB treatment) ART initiation in patients with HIV-associated TB meningitis showed no survival benefit, and an increase in severe adverse events, in the immediate ART arm. (M Estee Török et al. 2011) Collectively the results of these four trials suggest that ART should be started early in HIV/TB co-infected patients with advanced immunosuppression, apart from those with TB meningitis. (M Estée Török and Jeremy J Farrar 2011)

Our study validates these RCT findings in a non-experimental setting in rural sub-Saharan Africa, the setting where the majority of patients with HIV-TB co-infection live and are managed. Overall, we found no mortality difference between starting ART early (within 8 weeks of commencing TB treatment) and deferring ART until later. However, in those with a baseline CD4 count ≤50 cells/μl there was five-fold increase in survival in those starting ART in the first eight weeks compared to those that started ART later that was of borderline significance.

We found that deferring ART in patients with baseline CD4 counts >50 cells/μl until after 8 weeks was associated with no difference in mortality. Early commencement of ART was noted to cause TB-IRIS two to five times more frequently in three of the RCTs. The diagnosis and treatment of TB-IRIS may not be as readily feasible outside a clinical trial setting in a rural sub-Saharan African hospital. (Colebunders et al. 2006; Leone et al. 2010)

Our study provides further evidence that CD4 count is the best indicator of when to start ART in patients with TB. This has important implications as CD4 count measurement is still not widely available in many low- and middle-income countries. The potential to guide timing of ART and greatly reduce mortality in the huge number of TB co-infected patients, should act as further impetus to broaden access to this vital technology.

The strength of this study is that it is a validation of evidence from RCTs conducted in a resource-limited setting where cross-sectional imaging, mycobacterial culture, HIV viral load measurements and other diagnostics are not available. Such a setting is typical of where the majority of HIV/TB co-infected patients reside and present to healthcare facilities. The main limitation of our study is that it is observational in nature, relying on routinely collected data, and there may be unmeasured confounders accounting for mortality that influenced the physician’s decision of when to start ART. In Figure 2 it can be seen that the not treated group had a high initial mortality in the first 180 days, while those who deferred ART until after 180 days did not share the same initial high mortality. This suggests that the not treated group may have been more unwell with more advanced TB, other opportunistic infections or co-morbidities, or poor adherence to treatment. We did not have sufficient data to identify the reasons why patients who fulfilled criteria for ART initiation were not treated, whether patients interrupted ART, whether patients had concomitant opportunistic infections, whether patients developed TB-IRIS, or what were the causes of death. Such information may have helped us to further characterise subgroups in which the timing of ART was important.

Another potential limitation is that TB is diagnosed clinically in rural settings. In contrast to the RCTs mentioned previously, the diagnosis of TB was only confirmed by sputum smear in about 30% of the cohort, which means that TB may have been over-diagnosed. Although TB is epidemiologically the most likely cause of chronic respiratory symptoms, other opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis jirovecii and Cryptococcus neoformans may present in a similar fashion. Furthermore, some of the smear-positive cases may have been due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria which account for up to 3.6% of cases of acute or chronic cough in Kenya. (Githui et al. 1992; Scott et al. 2000) Nevertheless, we believe that this study provides important information from a rural sub-Saharan African setting where TB is common and frequently diagnosed and treated on the basis of clinical criteria.

It was encouraging to see that over the five-year period, the rate of HIV testing increased from just over half to 94%. HIV testing of TB patients is important both on a public health level to reduce HIV transmission and for the individual patient as it enables delivery of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and ART, with the potential to greatly increase survival. The recommendation of opt-out testing for TB patients could be of great benefit. (Pope et al. 2008)

This study also highlights the need to integrate HIV and TB clinical services. Only 60% of patients receiving tuberculosis treatment at our hospital were followed up in the local HIV clinic. It is not clear whether these patients received follow-up from an alternative facility, refused treatment or defaulted HIV clinic follow-up. The integration of HIV and TB services in a single clinic would enable better co-ordination of HIV and TB treatment, initiation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, management of complications and reduce loss to follow-up. Indeed evidence from Western Kenya has shown that combining the HIV and TB outpatient clinics into one combined clinic significantly increased the uptake of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and ART and significantly reduced mortality rates. (Huerga et al. 2010)

In conclusion, we have found that in HIV/TB co-infected patients with baseline CD4 counts <50 cells/μl in rural Kenya, ART had a significant reduction in mortality when started during the intensive phase of the first 8 weeks of TB treatment compared to starting after 8 weeks. We also found that only 60% of TB patients who tested positive for HIV were followed up in the local HIV clinic thus highlighting the urgent need to integrate HIV and TB services in rural settings so that patients can benefit from life-saving treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Clinical Officers and Nursing staff of the TB and HIV Clinics at PCEA Chogoria Hospital for their hard work and assistance in conducting this study. AS and JN were responsible for study design, data collection, analysis and discussion. MET contributed to the data interpretation, discussion and literature review. BF and DL helped with study design, statistical analysis and discussion. AS wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. MET acknowledges the support of the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Funding This study did not have any financial support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest All authors have no conflicts of interest

References

- Karim Abdool, Salim S, et al. [Retrieved December 6, 2011];Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 365(16):1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim Abdool, Salim S, et al. [Retrieved September 20, 2011];Timing of Initiation of Antiretroviral Drugs during Tuberculosis Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010 362:697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc François-Xavier, et al. [Retrieved December 6, 2011];Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 365(16):1471–1481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Karen, Meintjes Graeme. [Retrieved September 20, 2011];Management of individuals requiring antiretroviral therapy and TB treatment. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2010 5(1):61–69. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283339309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebunders R, et al. [Retrieved October 7, 2011];Tuberculosis immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in countries with limited resources. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2006 10(9):946–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Lung Disease . Guidelines for Implementing TB-HIV Collaborative Activities in Kenya: What Health Care workers’ need to know. Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation; Nairobi: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Division of Leprosy, Tuberculosis and Lung Disease . Guidelines on management of leprosy and tuberculosis. Kenyan Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation; Nairobi: [Retrieved July 18, 2012]. 2009. http://www.nltp.co.ke/docs/DLTLD_Treatment_Guidelines.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Githui W, et al. [Retrieved July 5, 2012];Cohort study of HIV-positive and HIV-negative tuberculosis, Nairobi, Kenya: comparison of bacteriological results. Tubercle and lung disease: the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 1992 73(4):203–209. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90087-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlir Diane V, et al. [Retrieved December 6, 2011];Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and tuberculosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 365(16):1482–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerga H, Spillane H, Guerrero W, Odongo A, Varaine F. [Retrieved October 7, 2011];Impact of introducing human immunodeficiency virus testing, treatment and care in a tuberculosis clinic in rural Kenya. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2010 14(5):611–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyeyune Rachel, et al. [Retrieved September 20, 2011];Causes of early mortality in HIV-infected TB suspects in an East African referral hospital. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2010 55(4):446–450. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181eb611a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn Stephen D, Churchyard Gavin. [Retrieved September 20, 2011];Epidemiology of HIV-associated tuberculosis. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2009 4(4):325–333. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c7d61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone Sebastiano, et al. [Retrieved October 7, 2011];Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: a systematic review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010 14(4):e283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manosuthi Weerawat, Chottanapand Suthat, Thongyen Supeda, Chaovavanich Achara, Sungkanuparph Somnuek. [Retrieved September 20, 2011];Survival rate and risk factors of mortality among HIV/tuberculosis-coinfected patients with and without antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2006 43(1):42–46. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230521.86964.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope Diana S, et al. [Retrieved October 7, 2011];A cluster-randomized trial of provider-initiated (opt-out) HIV counseling and testing of tuberculosis patients in South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2008 48(2):190–195. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181775926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JA, et al. [Retrieved July 5, 2012];Aetiology, outcome, and risk factors for mortality among adults with acute pneumonia in Kenya. Lancet. 2000 355(9211):1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Török M Estee, et al. [Retrieved November 21, 2011];Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)--associated tuberculous meningitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 52(11):1374–1383. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Török M Estée, Farrar Jeremy J. [Retrieved November 21, 2011];When to start antiretroviral therapy in HIV-associated tuberculosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 365(16):1538–1540. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1109546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco Maria, et al. [Retrieved September 20, 2011];Effect of simultaneous use of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival of HIV patients with tuberculosis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2009 50(2):148–152. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819367e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . Global tuberculosis control: WHO 2010 report. World Health Organisation Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . Transforming the Fight: Towards Elimination of Tuberculosis. World Health Organisation Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010b. The Global Plan to Stop TB 2011-2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yotebieng Marcel, et al. [Retrieved October 11, 2011];Effect on mortality and virological response of delaying antiretroviral therapy initiation in children receiving tuberculosis treatment. AIDS (London, England) 2010 24(9):1341–1349. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339e576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]