Abstract

Survey results regarding primary care physicians' likelihood of recommending a new vaccine were compared before and after the vaccine was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration for three new vaccines: herpes zoster (HZ), human papillomavirus (HPV) and rotavirus (RV), using physician networks representative of United States physicians. The main purpose of this study was to determine (a) how accurately physicians predict their eventual vaccine recommendations and the barriers they will experience in delivering the new vaccine and (b) whether physicians shift towards more or less strongly recommending a new vaccine from pre- to post-licensure. Responses from 284, 152 and 184 physicians were analyzed for the three vaccines, respectively. For all vaccines, there was a significant association between physicians' pre- and post-licensure recommendations (p<0.05). When responses changed from pre- to post-licensure, physicians tended to recommend a given vaccine more strongly than they had anticipated pre-licensure. Before vaccine availability, physicians tended to predict greater barriers to vaccine delivery than they eventually experienced. Surveys are useful for predicting physician practices, but may provide a slightly pessimistic view of physician adoption of new vaccines. Such data can be helpful in devising strategies to encourage vaccine delivery by physicians.

Abstract

Les résultats de sondages sur la probabilité que les médecins de première ligne recommandent un nouveau vaccin ont été comparés avant et après l'homologation de trois nouveaux vaccins par le Secrétariat américain aux produits alimentaires et pharmaceutiques (Food and Drug Administration) – herpès zoster (HZ), papillomavirus humain (PVH) et rotavirus (RV) –, en utilisant des réseaux représentatifs des médecins aux États-Unis. L'objectif principal de cette étude était de déterminer (a) à quel point les médecins peuvent prévoir leur éventuelle recommandation du vaccin ainsi que les obstacles qu'ils rencontreront pour son administration et (b) si les médecins recommandent plus ou moins fortement un nouveau vaccin avant et après son homologation. Les réponses de 284, 152 et 184 médecins ont été analysées pour les trois vaccins, respectivement. Pour tous les vaccins, il y a un lien significatif entre les recommandations avant et après l'homologation (p<0.05). Quand il y a changement de réponse avant et après l'homologation, les médecins sont plus enclins à fortement recommander un vaccin donné qu'ils ne l'avaient pensé avant l'homologation. Avant la disponibilité d'un vaccin, les médecins ont tendance à prévoir des obstacles plus grands dans l'administration du vaccin que ce qu'ils constatent éventuellement. Les sondages sont utiles pour prédire la pratique des médecins, mais peuvent donner un point de vue légèrement pessimiste sur l'adoption de nouveaux vaccins par les médecins. De telles données peuvent servir à concevoir des stratégies pour favoriser l'administration de vaccins par les médecins.

While social science literature is rich with studies examining the relationship between intentions for behaviour and actual behaviour, relatively little research has examined how well physicians' self-reported behavioural intentions predict their behaviours with respect to clinical care. This is an important question because numerous physician surveys are conducted each year and are utilized to devise strategies for improving patient care through such approaches as clinical guidelines. If physicians accurately predict their likely clinical practices in the future, then the results of surveys have value for planning strategies to influence physician behaviours. On the other hand, if physicians' intentions for practice are not sufficiently related to their actual practice, then using survey results to aid in the planning of programs would be ineffective. Literature searches uncovered only two prior studies that used pretest–posttest survey designs to examine this issue, but neither studied attitudes towards vaccine adoption (Millstein 1996; Maue et al. 2004). Because of the potential usefulness of such data to help in the planning and implementation of vaccination recommendations, we were particularly interested in how well primary care physicians' survey responses are able to predict their eventual vaccine delivery behaviour once a vaccine becomes licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.

In 2005 and 2006, three new vaccines were licensed for use in the United States. These three vaccines varied greatly in terms of targeted patient population, disease and mechanism of vaccine administration. The US Advisory Committee on Immunization practices (ACIP) recommended herpes zoster (HZ) vaccine (Zostavax®, Merck; CDC 2008) for routine use by a single intramuscular injection in immunocompetent adults ≥60 years old; human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for females 11–26 years old through intramuscular injection in a three-dose series (Gardasil™, Merck; CDC 2007); and rotavirus (RV) vaccine for routine use in infants and administered orally in a three-dose series (RotaTeq®, Merck; CDC 2006).

Our group administered both pre-licensure and post-licensure surveys for all three new vaccines to primary care physicians (Daley et al. 2006, 2010; Hurley et al. 2008, 2010; Kempe et al. 2007, 2009). These surveys were conducted without plans for the present analysis, with the aim to understand physicians' perceptions of a given vaccine at a particular moment. However, after collecting pre- and post-licensure survey data, the question of whether physicians' pre-licensure responses accurately predicted their eventual post-licensure recommendations for each vaccine became evident.

Therefore, our objectives for this analysis were to assess whether pre-licensure surveys were an effective tool for determining (a) whether physicians' vaccine recommendation intentions are predictive of their eventual vaccine recommendation practices, (b) whether physicians' responses pre- to post-licensure shifted towards more or less strongly recommending the vaccine, (c) whether perceived barriers before the vaccine was licensed were similar to perceived barriers after the vaccine was licensed and (d) whether physicians perceived barriers as more or less important after the vaccine was licensed.

Methods

Study setting

Pre-licensure surveys were administered from August 2005 to February 2006, and post-licensure surveys were administered from August 2007 to September 2008, resulting in a total of six surveys. These surveys were administered to national networks of primary care physicians in general internal medicine (GIM), family medicine (FM) and paediatrics (Peds). The human subjects review board at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus approved this study, and written informed consent was not required.

Population

The national networks of primary care physicians were developed as part of the Vaccine Policy Collaborative Initiative, a program designed collaboratively with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to conduct rapid-response surveys assessing physician attitudes about vaccine issues. GIM, FM and Peds physicians were recruited from the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Pediatrics, respectively. Quota sampling was performed to ensure that network physicians were similar to their respective memberships with regard to region of country, urban versus rural location and practice type. As described in detail elsewhere (Crane et al. 2008), demographic characteristics, practice attributes and reported attitudes about a range of vaccination issues were similar when network physicians were compared with physicians randomly sampled from the American Medical Association (AMA) master physician listing, which includes all physicians licensed in the United States.

ELIGIBILITY

To be eligible for this analysis, physicians had to receive both pre- and post-licensure surveys for a given vaccine. Owing to planned turnover in the three networks, approximately 50% of the network members were invited to complete both surveys for a given vaccine. For the HZ analysis, participants from both the GIM and FM network were eligible (n=333). The eligible Peds network was the same for both the RV (n=213) and HPV analyses (n=213).

Survey administration

Depending on each physician's preference, the survey was administered via mail or Internet. The Internet surveys were administered using web-based companies (Zoomerang MarketTools; Websurveyer Corp., Hernodon, VA; or Vovici Corp., Dulles, VA). Specific administration information for each survey has been previously published (Daley et al. 2006, 2010; Hurley et al. 2008, 2010; Kempe et al. 2007, 2009).

Survey design

Pre-licensure surveys examined physician perceptions of the disease for which the vaccine was developed, intentions for vaccination recommendations and anticipated barriers to administering the vaccines. Physicians were also provided information describing the purpose and effectiveness of the vaccine. The physicians were then asked how likely they were to recommend the vaccine based on that information in conjunction with hypothetical Food and Drug Administration approval and routine use recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (Appendix A). Post-licensure surveys assessed physicians' current vaccination practices and experienced barriers to vaccination. All responses were offered in 4-point Likert-type scales.

Reconciliation of survey items between pre-licensure and post-licensure surveys

Surveys were not designed a priori for this analysis, and consequently survey items were not always identical between pre- and post-licensure surveys. Therefore, some items were adapted to make questions and response categories comparable for analysis (see Table 1, available online at longwoods.com/content/23377 and sections below).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of pre-licensure and post-licensure survey questions

| Pre–Licensure Question and Responses | Post–Licensure Question and Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Herpes zoster (Recommendation) | How likely would you be to recommend HZ vaccine to adults 60–79 years of age? – Verylikely – Somewhat likely – Somewhat unlikely/Very unlikelyRemoved: Don't know/Not sure (4% of respondents) |

Regardless of whether you currently administer the vaccine in your office, please tell us about the strength of your recommendation for HZ vaccine to eligiblepatients. – I strongly recommend the vaccine – I recommend the vaccine, but not strongly – I recommend against the vaccineRemoved: I do not recommend for or against the vaccine (13% of respondents) |

| Human papillomavirus (Recommendation) | If FDA approved and recommended for routine use, how likely would you be to recommend for 10- to 12-year-old female patients? – Very likely – Somewhat likely – Somewhat unlikely/Very unlikelyRemoved: Don't know/Not sure (7%–14% of respondents) |

What is your current practice regarding recommending for 9- to 10-year-old female patients? – Strongly recommend – Recommend, but not strongly – Do not recommend |

| Rotavirus (Recommendation) | If this new rotavirus vaccine is FDA approved and if the ACIP and the AAP recommend the vaccine for routine use in all infants, which statement below best describes what you would be likely to do? – Strongly recommend the vaccine – Recommend the vaccine, but not strongly – Inform parents about the vaccine, but make no recommendation – Recommend against the vaccine |

What is your current practice with respect to recommending rotavirus vaccination for infants? – I strongly recommend the vaccine for all eligible infants of the appropriate age – I recommend the vaccine, but not strongly – I inform parents about the vaccine, but make no recommendation – I recommend against the vaccine |

| To what degree do you think the following will be barriers: | Whether or not you administer in your practice, how much of a barrier are the following: | |

| Herpes zoster (Barriers)* | The upfront costs for your practice to purchase the vaccine, regardless of reimbursement later – A major barrier – Somewhat of a barrier – A minor barrier – Not a barrier |

The upfront costs for your practice of purchasing the vaccine – A major barrier – Somewhat of a barrier – A minor barrier – Not a barrier |

| Human papillomavirus (Barriers)* | Lack of adequate reimbursement for vaccination – Definitely a barrier – Somewhat of a barrier – Minor barrier – Not a barrier |

Lack of adequate reimbursement for vaccination – Definitely a barrier – Somewhat of a barrier – Minor barrier – Not a barrier |

| Rotavirus (Barriers)* | Lack of adequate reimbursement for vaccination – Definitely a barrier – Somewhat of a barrier – A minor barrier – Not a barrier at all |

Lack of adequate reimbursement for vaccination – Definitely a barrier – Somewhat of a barrier – A minor barrier – Not a barrier at all |

As we are providing only examples for general clarification about comparisons between surveys, a single example of a barrier question from each set of surveys is presented.

INTENTIONS VERSUS PRACTICE PAIRING

In order to examine whether physicians' intentions towards vaccination predicted their eventual practice, pre-licensure recommendations were compared to post-licensure recommendations as shown in Table 1. Some response and question categories were combined to make them more comparable to a response category in the parallel survey. For example, for HZ and HPV, the pre-licensure response categories “Somewhat unlikely” and “Very unlikely” were combined and compared to the post-licensure response category of “I recommend against the vaccine” for HZ and “Do not recommend” for HPV. Also, for HPV, the pre-licensure question asking how likely physicians were to recommend the vaccine for 10- to 12-year-old female patients was compared to two post-licensure questions asking how physicians recommend the vaccine to 9- to 10-year-old patients and 11- to 12-year-old patients, because the pre-licensure question included characteristics of the two post-licensure questions. For RV, pre- and post-licensure questions and categories were the same, so no groupings were necessary (see Table 1).

For two surveys (HZ pre-licensure and HPV pre-licensure), “Don't know/Not sure” options were offered. Because these responses were non-informative for predicting behaviour, these respondents were removed from the relevant analyses. Additionally, for one survey (HZ post-licensure), “I don't recommend for or against the vaccine” was offered as a response. Because this answer did not match any response category offered pre-licensure, these respondents were removed from the analysis. This resulted in 4%–14% of respondents being removed from the relevant analyses.

BARRIER PAIRINGS

To determine whether physicians were able to accurately predict the impact of barriers to vaccine administration, we compared perceptions of a given barrier pre-licensure to perceptions of the same barrier post-licensure. For HZ and HPV, we compared two barrier questions between the pre- and post-licensure surveys. For RV, 12 questions matched between the pre- and post-licensure surveys. The response categories were the same for all three vaccines (see Table 1).

Analytic methods

For this analysis we aimed to compare physicians' pre-licensure responses to their post-licensure responses. Namely, we were first interested in whether a physician's pre-licensure response matched his or her post-licensure response. Then, if it changed, we sought to examine the direction of the shift. However, as previously mentioned, these surveys were not designed a priori for this analysis, so in some cases pre-licensure responses were aggregated and compared to aggregated post-licensure responses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

To examine whether physicians' intentions were related to their reported vaccine recommendation practices and to compare physicians' perceptions of a barrier between pre- and post-licensure, we used Kendall's tau-b (τ). This test was selected over another possible approach, repeated measures analysis, because for HZ and HPV identical language was not used between the pre-licensure and post-licensure survey questions and response categories were also not identical, a necessary condition for repeated measures analysis (see Table 1). The interpretation of Kendall's tau-b is similar to a Spearman's correlation coefficient (Field 2005). Therefore, using Kendall's tau-b, a maximum statistical score of +1 indicates that all the data pairs were 100% positively associated, and a minimum statistical score of –1 signifies that all the data pairs were 100% negatively associated (Noether 2010). A p-value <0.05 for this test indicates that a pre-licensure response was statistically significantly related to its post-licensure response. To display results, aggregate data are presented using proportions of responses in each ordinal category in Figures 1–3; however, all statistical tests were computed using the individual as the unit of analysis.

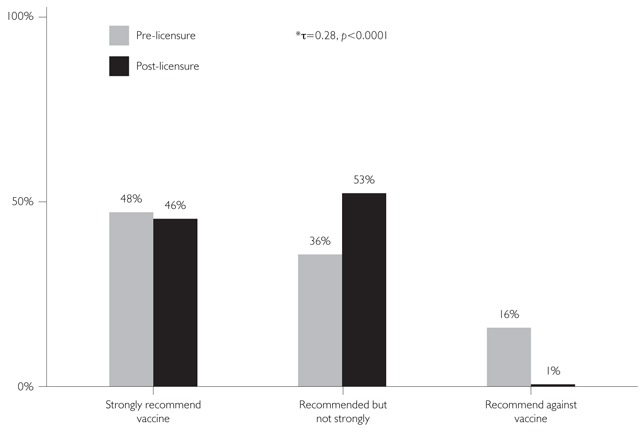

FIGURE 1.

Pre-licensure recommendations vs. post-licensure recommendations: Zoster

* τ = Kendall's tau test statistic

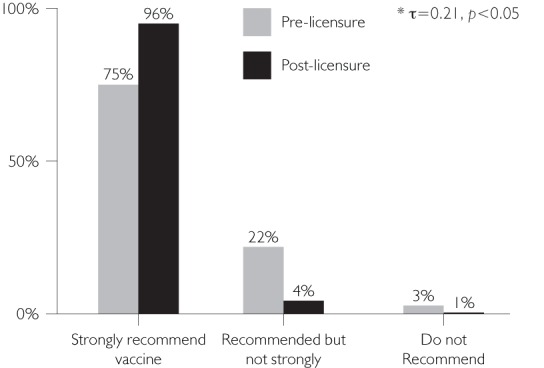

FIGURE 3.

Pre-licensure recommendations vs. post-licensure recommendations: Rotavirus

Unlike the vaccine recommendation questions for HZ and HPV, all of the barrier questions and response categories used identical wording in the paired pre- and post-licensure surveys. Therefore, Bhapkar's test was used to determine how physicians' responses regarding barriers shifted if they were not the same as their pre-licensure responses (i.e., if the response changed, did it shift towards perceiving a barrier as more or less important?). Bhapkar's test is an extension of McNemar's test, and both tests have been used for matched-pairs data for repeated measurement of subjects (Sun and Yang 2008). However, McNemar's test allows for only two outcome categories, and we often had four; therefore, Bhapkar's test was more appropriate. A p-value <0.05 for Bhapkar's test means the observed shift in the data is statistically significant.

Importantly, Kendall's tau-b and Bhapkar's test assess different aspects of the pre- and post-licensure relationship. When Kendall's tau-b is significant, indicating an association between responses pre- and post-licensure, Bhapkar's test could be non-significant (no shift) or significant (indicating a shift in responses in a consistent direction). Bhapkar's test can also be significant (indicating a shift) when Kendall's tau-b is non-significant (indicating no relationship). For example, if physicians believed strongly that they would not recommend a vaccine but then decided to recommend it strongly once it was licensed, the Kendall's tau-b would not be significant, but Bhapkar's test would be highly significant.

Results

Survey response rate and characteristics of respondents

For HZ, of the 333 GIM and FM physicians who were surveyed both pre- and post-licensure, 254 (76%) completed both surveys. GIM and FM results were combined for the analysis, as responses to questions were very similar for these specialties. For HPV, 152 of the 213 (71%) physicians completed both surveys, and for RV, 184 of 213 (86%) physicians completed both surveys.

Table 2 compares the networks used in the present analysis to the sentinel networks from which they were drawn. For the RV and HPV surveys, eligible physicians were very similar to the sentinel Peds network from which they were drawn. For the HZ survey, in general, the eligible physicians were very similar to the original networks. Physicians from the south were somewhat underrepresented in the FM and GIM respondents when compared to the networks. For GIM, rural physicians and physicians practising in community health centres or hospital settings were somewhat underrepresented among the eligible physicians when compared with the sentinel GIM network.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of original sentinel networks to eligible physicians

| RV and HPV | HZ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Sentinel Peds (n=429) | Eligible Peds (n=213) | Sentinel FM (n=411) | Eligible FM (n=155) | Sentinel GIM (n=417) | Eligible GIM (n=178) |

| Male, % (n) | 54 | 57 | NA | NA | 59 | 59 |

| Region of country, % | ||||||

| Midwest | 20 | 18 | 30 | 30 | 21 | 23 |

| Northeast | 28 | 26 | 15 | 16 | 25 | 29 |

| South | 34 | 38 | 32 | 23 | 33 | 25 |

| West | 18 | 19 | 24 | 30 | 20 | 23 |

| Location of practice, % | ||||||

| Urban, inner-city | 44 | 45 | 27 | 28 | 43 | 46 |

| Urban, not inner-city/suburban | 44 | 44 | 45 | 44 | 43 | 46 |

| Rural | 12 | 12 | 28 | 28 | 13 | 8 |

| Type of practice, % | ||||||

| Private practice | 86 | 90 | 80 | 79 | 76 | 83 |

| Community- or hospital-based | 12 | 9 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 14 |

| Managed care organization | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

Peds = Paediatric medicine; FM = Family medicine; GIM = General internal medicine; NA= Not available

Pre-licensure recommendations vs. post-licensure recommendations

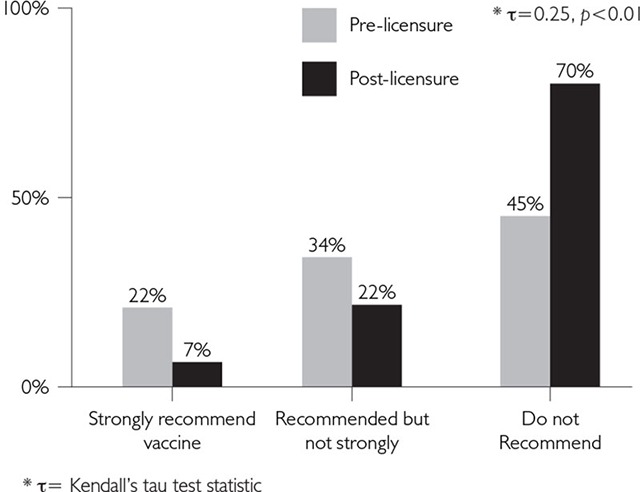

For HZ (adults), HPV among 9- to 10-year-olds, HPV among 16- to 18-year-olds and RV (infants), there was a significant association between physicians' pre- and post-licensure recommendations [τ range=0.21–0.37, (p<0.05)] (Figures 1–3). Notably, in contrast to all other vaccine recommendations, which grew in strength between pre- and post-licensure, the strong positive association for the 9- to 10-year-old female HPV recommendation was due to physicians' pre-licensure responses indicating that they did not intend to recommend this vaccine to this age group and their post-licensure consistency in not recommending the vaccine (Figure 2a).

FIGURE 2A.

Pre-licensure recommendations vs. post-licensure recommendations: HPV Ages 9–10

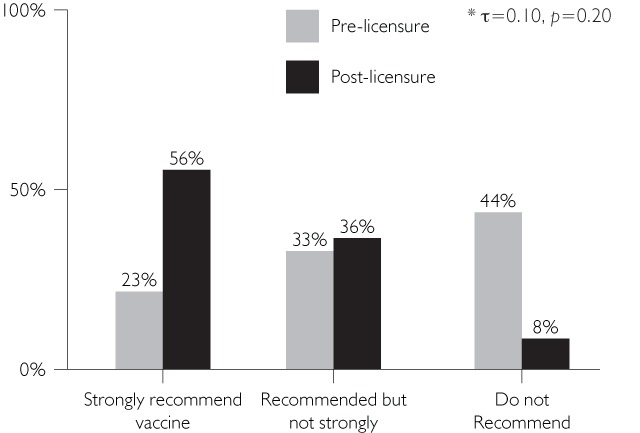

There were two comparisons that did not demonstrate an association pre- to post-licensure, namely, HPV vaccine recommendations for the 11- to 12-year-old and 13- to 15-year-old female age groups (τ=0.10 [p=0.20] and τ=0.13 [p=0.12], respectively).

Pre-licensure, physicians tended to believe that they would not recommend the vaccine as strongly as they reported recommending it post-licensure (Figures 2b and 2c).

FIGURE 2B.

Pre-licensure recommendations vs. post-licensure recommendations: HPV Ages 11–12

FIGURE 2C.

Pre-licensure recommendations vs. post-licensure recommendations: HPV Ages 13–15

In general, Figures 1–3 suggest that post-licensure, respondents were inclined to recommend a given vaccine more strongly than they had originally planned when asked pre-licensure. (This interpretation must be made with caution because the response categories were not the same pre- and post-licensure, and a shift could be due to differences in the response categories.) There were two exceptions to this statement. For the HZ recommendations, 48% of physicians reported that they were very likely to recommend the vaccine pre-licensure, and a similar proportion (46%) reported strongly recommending the vaccine post-licensure. However, 36% had reported being somewhat likely to recommend the HZ vaccine pre-licensure and 53% reported that they recommended the vaccine, but not strongly, post-licensure. Therefore, 84% of physicians reported that they were very or somewhat likely to recommend the vaccine pre-licensure and 99% were recommending the vaccine at some level post-licensure (Figure 1). The other exception was seen for the 9- to 10-year-old age group for HPV, where 45% of physicians said pre-licensure that they were not likely to recommend the vaccine and post-licensure, this figure grew to 70% who reported that they did not recommend the vaccine (Figure 2a).

Perceived barriers pre-licensure to post-licensure

For 15 out of the 16 barrier questions from all three vaccine surveys combined, physicians' perceptions of a given barrier from pre- to post-licensure were positively and significantly associated (τ range=0.24–0.46, [p-value<0.001]). The only barrier for which there was not a significant association was seen in the RV barrier of “Difficulty obtaining adequate vaccine supplies” (τ=0.10 [p=0.14]). In this case, physicians thought this would be much more of a barrier pre-licensure than they reported post-licensure (see Appendix B).

Using Bhapkar's test, when perceptions of barriers shifted from the pre- to post-licensure responses, the shift was towards reporting that a given barrier was less important for 13 out of 16 barrier questions (p<0.05). For the RV barriers of “My belief that rotavirus is not a severe disease that requires a vaccination” and “General administrative burden of rotavirus vaccine to my practice,” responses were very similar pre- and post-licensure, and therefore, Bhapkar's test was not significant. The only barrier where there was a significant shift towards reporting the barrier as more important was for the HZ barrier of “The need to store the vaccine in a freezer in a separate sealed compartment” (p<0.001) (see Appendix B).

Discussion and Conclusion

This post hoc analysis examined whether primary care physicians' pre-licensure intentions to recommend a new vaccine were related to their eventual vaccination practices post-licensure and, if their responses changed, whether they shifted towards more or less strongly recommending the vaccine from pre- to post-licensure. The issue of intention–behaviour consistency among physicians has previously been studied, and the results of studies that utilized surveys as their measurement method have been mixed. One demonstrated that surveys were effective predictors of physician-reported behaviours (Millstein 1996), while another did not find a significant relationship (Maue et al. 2004). This mix of results may be dependent on physicians' specialties and the specific behaviour being studied.

FIGURE 2D.

Pre-licensure recommendations vs. post-licensure recommendations: HPV Ages 16–18

The present study determined that primary care physicians' pre-licensure recommendations were generally associated with their post-licensure recommendations, demonstrating that providers are good predictors of their eventual behaviour related to vaccine delivery. An important implication of this finding is that survey results are likely to provide useful information for guiding vaccine implementation policies and strategies, and are relatively accurate in predicting physician reactions to vaccine delivery recommendations disseminated by government agencies and organizations.

Our data also suggest that the recommendations of the US ACIP have a strong influence on physician practices in that country (CDC 2006, 2007, 2008). This conclusion is demonstrated in our results for the HPV vaccine recommendations. Though the ACIP stated that the vaccine could be used in females as young as 9 to 10 years old, they did not recommend routine use in this group (CDC 2007). Seventy per cent of the physicians said they did not recommend the vaccine to this age group after publication of ACIP recommendations versus only 45% of physicians reporting that they were not likely to recommend the vaccine to this age group prior to ACIP recommendations. Conversely, for females 11 to 12 years old, the group for which the vaccine was recommended for routine use by the ACIP (CDC 2007), only 8% stated that they would not recommend the vaccine for this age group after licensure and subsequent recommendation by the ACIP, versus 44% of physicians who stated pre-licensure that they would recommend it. Another example of ACIP influence on physician vaccine recommendation practices was reported in the pre-licensure survey on RV. When physicians were asked how they would recommend the vaccine if it were recommended for permissive use instead of routine use, 33% of physicians reported they would recommend the vaccine strongly if it were permissive versus 50% who would strongly recommend the vaccine if it were routinely recommended (Kempe et al. 2007).

Additionally, physicians' perceptions of a given barrier pre- and post-licensure were positively and significantly associated, and physicians were also more likely to overestimate the effect of a given barrier pre-licensure. More specifically, concerns about finances (e.g., upfront costs of the vaccine and reimbursement by insurance companies), vaccine safety and parents' acceptance of the vaccine lessened after licensure. This finding suggests a bit of a pessimistic bias towards the feasibility of delivering a new vaccine before one has experience with it. The finding may also reflect willingness to overcome potential barriers once a vaccine is available and has been endorsed by the ACIP.

Interestingly, physician recommendations seem to have varying correlations with national estimates of vaccine uptake in the United States. For example, the post-licensure survey on RV saw 72% of physicians strongly recommending the vaccine (Kempe et al. 2010), a figure that corresponded to an Immunization Information System (IIS) electronic registry estimate of 71% uptake in eight US states for receipt of more than a single dose in infants older than five months of age (CDC 2010). However, for HPV, 37% of girls 13–17 years of age had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, and only 18% had completed the three-dose series (CDC 2009), whereas approximately 93% of physicians surveyed post-licensure reported strongly recommending the vaccine for these ages (Daley et al. 2010). For HZ, approximately 7% of adults aged ≥60 had received the vaccine in the year this survey was conducted (Schiller and Euler 2009), compared to 46% of physicians surveyed post-licensure who reported they strongly recommended the vaccine (Hurley et al. 2010).

The information cited above suggests that vaccine uptake faces many different obstacles. For example, the new rotavirus vaccine has met relatively little resistance from parents and physicians. However, the HPV vaccine has received much resistance from a variety of parental groups, and even some physician groups, who believe the vaccine is associated with seizures and intellectual disability, and the suggestion that it may encourage female promiscuity (Intlekofer et al. 2012). The HPV vaccine was even part of the US Republican primary debates in 2011 (Gabriel and Grady 2011).

An issue we could not directly assess is the effect of pharmaceutical advertising. Advertising surely has an effect on physician vaccine recommendation practices, but the larger effect is most likely to be seen on patient behaviour, as has been shown with other pharmaceutical product advertising (Khanfar et al. 2007). Furthermore, for all three vaccines, the top two perceived barriers both pre- and post-licensure were financial concerns related to upfront vaccine purchase by the practice and insurance reimbursement, both of which varied greatly among the three vaccines (Daley et al. 2006, 2010; Hurley et al. 2008, 2010; Kempe et al. 2007, 2009).

Considering how very different these vaccines are in terms of the diseases that they help prevent, the patient populations targeted, clinical efficacy, route of vaccine administration and the different physician specialties that are charged with delivering the vaccines (i.e., paediatricians, family physicians and internists), our finding that the physicians surveyed were generally accurate predictors of their eventual reported vaccination practices across all three vaccines suggests that the results are generalizable to vaccines that will be introduced in the future, and possibly to the delivery of other types of medical care. This interpretation also argues that surveys are valuable tools for understanding physicians' attitudes and behaviours. Furthermore, we believe that our results are generalizable to US primary care physicians, as the physicians who were eligible for this analysis were similar to those in the original sentinel networks.

This study has limitations. First, because we did not design the surveys with the present analysis in mind, recommendation questions and their response categories were not worded identically from pre- to post-licensure surveys, with the exception of the RV surveys. However, after data collection it became clear that our data could help answer the question of whether physicians' survey responses are accurate predictors of behaviour at a later time. In a few instances, this conclusion resulted in a need to drop a small proportion of individuals from the analysis because of their selection of “Don't know” responses or responses that could not be matched across surveys. Also, our post-licensure surveys were designed to assess practices in relation to ACIP recommendations, which had not been made at the time of the pre-licensure surveys. Therefore, wording was changed post-licensure to ensure that survey results could be interpreted in the most current environment. Additionally, with the exception of RV, only a subset of the barriers matched between the pre- and post-licensure HZ and HPV surveys (only 2/17 and 2/12 possible barriers for HZ and HPV matched, respectively). Another limitation was that although our sample of physicians appeared to be representative, there were differences between physicians who received both surveys of a pair and those who received individual surveys; further, physicians who agreed to be surveyed may have held different views on vaccine-related issues than those who were not surveyed. Finally, our findings are based on self-reports and statistical comparisons rather than actual observation of physicians' behaviours.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess whether pre-licensure survey responses about intentions towards administering a new vaccine accurately predict primary care physicians' reported behaviours after the vaccine is licensed. We found that pre-licensure survey responses were generally valid predictors for what a physician reports doing in terms of recommending new vaccines. Furthermore, we found that physicians tend to overestimate the impact of barriers to vaccine delivery prior to their experience of delivering the vaccine. Therefore, our results argue that physicians and policy makers should have confidence in survey results assessing what physicians predict their future practices will be, and that surveys can consequently be useful tools to assist in the development of vaccine implementation policies. Finally, our data also suggest that the recommendations of the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices have a strong influence on physician vaccination practices.

Acknowledgements

Other authors of this paper include Jennifer Barrow, MSPH; Christine Babbel, MSPH; L. Miriam Dickinson, PhD; and Allison Kempe, MPH, MD, all of the Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO.

The authors wish to thank Lynn Olson, PhD and Karen O'Connor, Department of Research, American Academy of Pediatrics; Herbert Young, MD and Bellinda Schoof, MHA, American Academy of Family Practice; Vincenza Snow, MD and Wayne Bylsma, PhD, American College of Physicians; and the leaderships of all these institutions for collaborating in the establishment of the Sentinel Networks in Pediatrics, Family Medicine and General Internal Medicine. We also want to thank Diane Fairclough from the Colorado Health Outcomes Program for her assistance in helping to select appropriate statistical tests. Finally, we thank all paediatricians, family medicine physicians and general internists in the Networks for participating and responding to these surveys.

This investigation was funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SIP (5 U48 DP000054-03) through the Rocky Mountain Prevention Research Center, Denver, CO. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Appendix A Pre-licensure vaccine information given to physicians

Herpes Zoster

Results were recently published from a large randomized controlled trial of a vaccine against herpes zoster, which included 39,000 men and women aged 60 years and over. Persons with immunosuppressive conditions were excluded. Also excluded were persons with life-threatening disease likely to limit survival to less than 5 years, bed-ridden or homebound patients, and persons who could not effectively participate in the study, such as those with dementia.

-

•

The vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine, similar to the varicella (chickenpox) vaccine developed for children, but is more potent.

-

•

The vaccine proved efficacious in reducing the burden of disease (measured by a score derived from duration and intensity of pain) for herpes zoster illness by 61.1% and incidence of post-herpetic neuralgia (defined in the study as persistence of pain for more than 90 days after the onset of zoster rash) by 66.5%. The vaccine reduced the overall incidence of herpes zoster by 51.4% (from 662/18,357 among placebo recipients to 322/18,359 among vaccine recipients).

-

•

There are no data about efficacy of the vaccine more than 3 years after vaccination.

-

•

There were no specific safety concerns that arose during the vaccine trial.

-

•

The vaccine will require storage in physician offices at freezer temperatures.

-

•

The herpes zoster vaccine is expected to be licensed by the FDA in early 2006 for older adults without underlying immunosuppressive conditions (e.g., malignancy, HIV infection, corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive/cytotoxic therapy).

-

•

Patients will most likely be eligible for the vaccine if they know they have had primary varicella or if they have lived in the US for at least 30 years.

-

•

The study was not large enough to assess the issue of transmission of live varicella zoster vaccine strain virus from vaccinated persons to immunosuppressed household contacts. However, based on years of experience pre- and post-licensure with the varicella vaccine, this would appear to be extremely unlikely.

HPV

While several HPV vaccines are under development, one candidate vaccine (Gardasil™, developed by Merck) may be licensed by the FDA within the next 1 to 2 years. This vaccine is quadrivalent, protecting against two HPV types that cause cervical cancer and two HPV types that cause genital warts in females and males. The vaccine contains non-infectious virus proteins and has been found to be highly effective at preventing persistent HPV infections and cervical cancer precursors. This vaccine will require 3 doses, given at day 1, 2 months and 6 months.

Rotavirus

A new rotavirus vaccine has been developed and is expected to be licensed in the US within the next year.

-

•

It is an oral, live attenuated vaccine, developed using a different rotavirus strain than was used to develop the previously licensed vaccine (bovine rather than rhesus).

-

•

The randomized controlled trial of the new vaccine involved more than 70,000 infants (compared with approximately 10,000 infants in the pre-licensure study of the previous Rotashield vaccine), in order to assess any possible connection with intussusception.

-

•

In the new trial, the vaccine had lower rates of associated fever and gastrointestinal symptoms than the previous vaccine, and the risk of intussusception was no higher in infants who received rotavirus vaccine compared to those who received a placebo.

-

•

The new vaccine has an efficacy of 74% at preventing any gastroenteritis caused by the rotavirus strains included in the vaccine, and an efficacy of 98% at preventing severe gastroenteritis.

-

•

Soon after licensure, the ACIP is expected to recommend routine vaccination at 2, 4 and 6 months of age.

Appendix B

Summary of barrier results

| Question stem for all: Please tell us how much the following factors are barriers to your giving the new___________vaccine in your practice | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Kendall's Tau | Bhapkar's Test | ||||

| Pre (%) | Post (%) | τ | p-value | p-value | ||

| Herpes Zoster | ||||||

| The need to store the vaccine in a freezer in a separate sealed compartment | Definitely a barrier | 11 | 17 | 0.24 | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 14 | 22 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 28 | 22 | ||||

| Not a barrier | 47 | 38 | ||||

| The upfront costs for my practice of purchasing the vaccine | Definitely a barrier | 44 | 29 | 0.31 | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 26 | 34 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 15 | 23 | ||||

| Not a barrier | 15 | 14 | ||||

| HPV | ||||||

| Lack of adequate reimbursement for HPV vaccination | Definitely a barrier | 49 | 21 | 0.26 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 30 | 22 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 15 | 21 | ||||

| Not a barrier | 6 | 35 | ||||

| The upfront costs for my practice to purchase HPV vaccine | Definitely a barrier | 24 | 14 | 0.27 | <0.0001 | <0.01 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 24 | 23 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 31 | 25 | ||||

| Not a barrier | 21 | 37 | ||||

| Rotavirus | ||||||

| My concerns about the safety of the rotavirus vaccine | Definitely a barrier | 22 | 8 | 0.40 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 21 | 17 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 39 | 30 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 18 | 45 | ||||

| Parents' reluctance to have their child vaccinated because of the withdrawal of the previous rotavirus vaccine | Definitely a barrier | 26 | 1 | 0.26 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 42 | 20 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 27 | 39 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 5 | 40 | ||||

| Parents' concerns about vaccine safety in general | Definitely a barrier | 15 | 5 | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 37 | 29 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 43 | 50 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 5 | 15 | ||||

| Parents' not thinking that a rotavirus vaccine is necessary | Definitely a barrier | 11 | 4 | 0.30 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 38 | 19 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 42 | 41 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 9 | 35 | ||||

| My belief that rotavirus is not a severe disease that requires a vaccination | Definitely a barrier | 4 | 3 | 0.45 | <0.0001 | 0.22 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 12 | 9 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 16 | 12 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 68 | 75 | ||||

| The time it takes me to discuss rotavirus vaccine safety with parents | Definitely a barrier | 4 | 1 | 0.37 | <0.0001 | <0.01 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 11 | 8 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 37 | 30 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 48 | 61 | ||||

| Difficulty obtaining adequate vaccine supplies | Definitely a barrier | 16 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.14 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 32 | 9 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 41 | 24 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 12 | 66 | ||||

| Lack of adequate reimbursement for vaccination | Definitely a barrier | 46 | 17 | 0.37 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 30 | 15 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 13 | 31 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 10 | 37 | ||||

| The upfront costs for my practice to purchase the vaccine | Definitely a barrier | 22 | 18 | 0.46 | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 26 | 15 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 25 | 27 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 27 | 40 | ||||

| Failure of some insurance companies to cover rotavirus vaccination | Definitely a barrier | 54 | 22 | 0.35 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 26 | 22 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 10 | 28 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 9 | 28 | ||||

| General administrative burden of rotavirus vaccine to my practice | Definitely a barrier | 2 | 5 | 0.37 | <0.0001 | 0.20 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 15 | 14 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 40 | 34 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 43 | 48 | ||||

| My concern about adding another vaccine to an already overloaded vaccine schedule | Definitely a barrier | 7 | 7 | 0.42 | <0.0001 | <0.05 |

| Somewhat of a barrier | 16 | 14 | ||||

| A minor barrier | 38 | 31 | ||||

| Not a barrier at all | 39 | 49 | ||||

Contributor Information

Laura Seewald, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO.

Laura Hurley, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Division of General Internal Medicine, Denver Health, Denver, CO.

Lori A. Crane, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Community and Behavioral Health, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

Fran Dong, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Colorado Health Outcomes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

Shannon Stokley, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

Matthew F. Daley, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

Jennifer Barrow, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO.

Christine Babbel, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO.

L. Miriam Dickinson, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO.

Allison Kempe, Children's Outcomes Research Program, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2006. “Prevention of Rotavirus gastroenteritis among Infants and Children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 55: 1–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2007. “Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 56: 1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2008. “Prevention of Herpes zoster: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 57: 1–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2009. “National, State and Local Area Vaccination Coverage among Adolescents Aged 13-17 Years – United States, 2008.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 18: 997–1001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2010. “Rotavirus Vaccination Coverage among Infants Aged 5 months – Immunization Information System Sentinel Sites, United States, June 2006 – June 2009.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports 59: 521–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L.A., Daley M.F., Barrow J., Babbel C., Beaty B.L., Steiner J.F., et al. 2008. “Sentinel Physician Networks as a Technique for Rapid Immunization Policy Surveys.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 31: 43–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M.F., Crane L.A., Markowitz L.E., Black S., Beaty S., B., Barrow J., et al. 2010. “Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Practices: A Survey of US Physicians 18 Months Post-Licensure.” Pediatrics 126: 425–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M.F., Liddon N., Crane L.A., Beaty B.L., Barrow J., Babbel C., et al. 2006. “A National Survey of Pediatrician Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Human Papillomavirus Vaccination.” Pediatrics 118: 2280–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. 2005. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel T., Grady D. 2011. “In Republican Race, a Heated Battle over the HPV Vaccine.” The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2013 <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/14/us/politics/republican-candidates-battle-over-hpv-vaccine.html?_r=0#>. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley L.P., Harpaz R., Daley M.F., Crane L.A., Beaty B.L., Barrow J., et al. 2008. “National Survey of Primary Care Physicians Regarding Herpes zoster and the Herpes zoster Vaccine.” Journal of Infectious Disease 197 (Suppl. 2), S216-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley L.P., Lindley M.C., Harpaz R., Stokely S., Daley M.F., Crane L.A., et al. 2010. “Barriers to the use of Herpes zoster Vaccine.” Annals of Internal Medicine 152: 555–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intlekofer K.A., Cunningham M.J., Caplan A.L. 2012. “The HPV Vaccine Controversy.” Virtual Mentor 14: 39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe A., Daley M.F., Parashar U.D., Crane L.A., Beaty B.L., Stokley S., et al. 2007. “Will Pediatricians Adopt the New Rotavirus Vaccine?” Pediatrics 119: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe A., Patel M.M., Daley M.F., Crane L.A., Beaty B.L., Stokley S., et al. 2009. “Adoption of Rotavirus Vaccination by Pediatricians and Family Medicine Physicians in the United States.” Pediatrics 124: 809–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanfar N., Loudon D., Sircar-Ramsewak F. 2007. “FDA Direct-to-Consumer Advertising for Prescription Drugs: What Are Consumer Preferences and Response Tendencies?” Health Market Quarterly 24: 77–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maue S.K., Segal R., Kimberlin C.L., Lipowski E.E. 2004. “Predicting Physician Guideline Compliance: An Assessment of Motivators and Perceived Barriers.” American Journal of Managed Care 10: 383–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein S.G. 1996. “Utility of the Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior for Predicting Physician Behavior: A Prospective Analysis.” Health Psychology 15: 398–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noether G.E. 2010. “Why Kendall Tau?” Retrieved April 3, 2013 <http://www.rsscse-edu.org.uk/tsj/bts/noether/text.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J., Euler G.L. 2009. “Vaccination Coverage Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey: United States, 2008.” National Centre for Health Statistics. Retrieved April 3, 2013 <http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/vaccine_coverage/vaccine_coverage.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Yang Z. 2008. “Generalized McNemar's Test for Homogeneity of the Marginal Distributions.” In SAS Global Forum 2008. Cary, NC: SAS Institute [Google Scholar]