Abstract

Strong primary care is a fundamental underpinning of high-performing health systems. Sadly, primary care infrastructure and performance in Canada lag behind many of our international peers. Although substantial reforms have been implemented over the past decade, progress has been uneven, and no province has all the essential system elements in place. Continued investment is both needed and affordable. However, whether those investments – and others necessary to strengthen medicare – are made will be determined largely by the ongoing clash between communitarian and libertarian values.

Abstract

La force des soins de santé primaires constitue un pilier fondamental pour le rendement optimal des systèmes de santé. Malheureusement, l'infrastructure et le rendement des soins primaires au Canada accusent un retard par rapport à plusieurs de nos pairs internationaux. Bien que d'importantes réformes aient été mises en œuvre au cours des derniers dix ans, la progression reste inégale et aucune province n'a encore en place tous les éléments essentiels du système. Il est nécessaire de poursuivre les investissements, et nous avons les moyens de le faire. Cependant, la réalisation de ces investissements – ainsi que celle des investissements nécessaires pour renforcer l'assurance santé – dépendra grandement du conflit constant entre les valeurs communautariennes et les valeurs libertariennes.

Unfinished Business

The medicare we have today is not the entire program envisioned by Tommy Douglas and Emmett Hall. In 1961, Douglas said: “This [the proposed Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance plan] … will prove to be the forerunner of a national medical care insurance plan. It will become the nucleus around which Canada will ultimately build a comprehensive health insurance program which will cover all health services – not just hospitalization and medical care – but eventually … all other services which people receive.” Featured prominently in the Hall Commission Report (Royal Commission 1964) was a “Health Charter for Canadians” calling for a comprehensive, universal health service program “includ[ing] all health services, preventive, diagnostic, curative and rehabilitative, that modern medical and other sciences can provide.” The Commission made specific recommendations for coverage of vision care, dental care and pharmaceuticals. This vision has yet to be realized.

Nevertheless, Professor Ted Marmor at Yale University has referred to Canadian medicare as a public policy miracle. Perhaps what is truly miraculous is that in an inherently unequal capitalist society, where access to almost all other goods and services depends on ability to pay, the majority of Canadians supported, and continue to support, a program that rests on the fundamental principle that access to care should be determined solely by medical need. Many of us take pride and delight in this anomaly, while brushing aside unsettling questions about the limits of medicare. But if the principle of care based on need deserves our support in relation to hospital and physicians' services, why should it stop there? What about other beneficial health services such as pharmaceuticals, vision care, dental care, home care, chiropractic services and rehabilitation therapies? We have few principled answers.

Primary Considerations: A Roadmap

Here, however, I narrow the focus to primary care. I hope to make the following points:

A strong primary care sector is vital to health system performance and outcomes.

Canada's primary care performance lags behind that of many of our peer countries.

Governments at the federal and provincial/territorial levels in Canada have made substantial investments in strengthening primary care since 2000.

Progress has been uneven across the country, and no province2 has all the essential elements in place.

Nevertheless, the reforms are starting to bear fruit.

Because the process of primary care renewal is incomplete, substantial further investments are required.

Government spending on primary care remains modest.

Increased government or total spending on healthcare is unlikely to threaten economic performance and need not crowd out public spending on other social priorities, such as education.

And finally, although facts and evidence can inform policy discussions, a clash between libertarian and communitarian values underlies ongoing conflict about the future of medicare.

A Consensus of Evidence

There is now a compelling body of evidence, much of it produced or summarized by Barbara Starfield, demonstrating the association between strong primary care systems and superior and more equitable health outcomes (although not necessarily lower costs) (Kringos et al. 2013; Macinko et al. 2003; Starfield 2012; Starfield and Shi 2002).

Canadian policy makers and commentators are increasingly recognizing the fundamental importance of primary care. Fred Horne, Alberta's Minister of Health and Wellness, has referred to putting “primary health care where it rightfully belongs, at the centre of the health system” (Horne 2012). The Drummond Commission on the Reform of Ontario's Public Services recommended that the government “[m]ake primary care a focal point of a new integrated health model” (Commission 2012). The federal Minister of Health, Leona Aglukkaq, recently stated that “Community-based primary health care is at the heart of our health care system” (CIHR 2013).

Not Even the Bronze for Canada

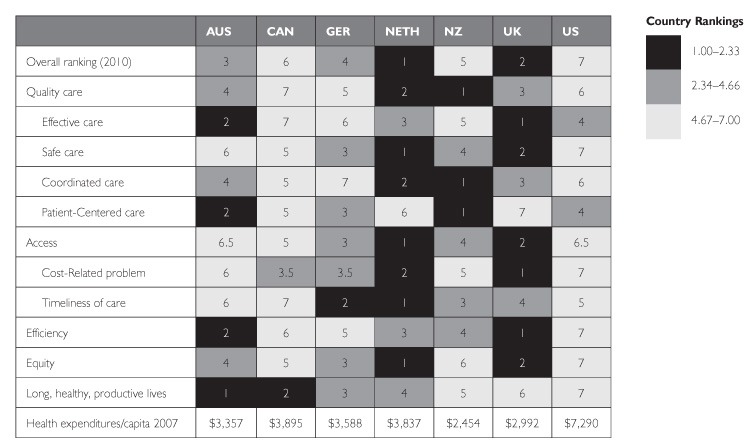

But Canada has far to go. Figure 1 summarizes the Commonwealth Fund's 2010 assessment of the comparative performance of the healthcare systems of seven high-income countries (Davis et al. 2010). The performance rankings were based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) health data and international surveys of patients and primary care physicians conducted by the Fund. Underlying this picture are some potential policy lessons about primary care.

FIGURE 1.

Health system rankings, Commonwealth Fund 2010

Source: Commonwealth Fund

Two countries stand out in overall performance: the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Although they differ substantially regarding healthcare financing and the role of private insurance, their primary care policy and system characteristics have much in common. Both have invested heavily over the last two decades in strengthening primary care. Both primary care systems feature mandatory patient registration with a provider, no user charges, local governance, gate-keeping, capitation-based blended payment for physicians, interdisciplinary teams, and major investments in quality improvement initiatives and electronic medical records (EMRs). The relationship between overall health system performance and investment in primary care, and the commonalities between the primary care systems of the highest-performing countries, is unlikely to be pure coincidence. Their policies and system features deserve serious consideration in Canada.

Legacy of a Lost Decade

Many high-income countries focused on primary care during the 1990s. Canada barely managed to tread water. We have yet to catch up; our performance continues to lag, particularly in timely access to care and in primary care infrastructure. The Commonwealth Fund surveys highlight opportunities for improvement in Canadian performance in primary care.

Whether from the perspective of the general population, of people with chronic or recent serious health problems, or of primary care physicians, measures of access to primary care lag well behind our peers. For example, Canada tied for last among 11 countries in the percentage of adults who report having an appointment with a doctor or nurse the same or next day when last sick (Commonwealth Fund 2010). Canada ranked last in the proportion of sicker adults who found it easy or very easy to get medical care outside regular practice hours without going to the emergency room, and second last in primary care physicians who reported having an arrangement for patients to be seen by a doctor or nurse when the practice is closed (Commonwealth Fund 2011a, 2012; Schoen et al. 2012).

Canada's performance on measures of patient-centredness and engagement is relatively good as seen by patients (Commonwealth Fund 2010, 2011a), but Canada ranks last in the percentage of primary care physicians who report using patient-friendly technologies for requesting appointments or referrals online or e-mailing about medical concerns (Commonwealth Fund 2012).

Canada is among the best performers on most measures of quality of care (though coming in seventh of 11 in the proportion of diabetic patients whose feet were examined in the past year) (Commonwealth Fund 2010, 2011a). However, primary care practices in all countries perform poorly on helping coordinate or arrange care for patients with serious or chronic illnesses.

Canada is solidly back in the bottom half of surveyed countries, however, with respect to human resources and infrastructure such as including at least one FTE non-physician provider in the practice or the use of EMRs (Commonwealth Fund 2012). Infrastructure for performance measurement, feedback and quality improvement is grossly underdeveloped relative to most comparator countries (Commonwealth Fund 2012).

Responses to these patient surveys are stratified by income, providing an opportunity to examine differences in responses from sicker patients in above- and below-average income groups (Commonwealth Fund 2011b). In some cases – availability of a regular source of care, for example, or help with arranging or coordinating care – differences were minimal or non-existent. But other measures, such as the accessibility of same- or next-day appointments, and help with treatment planning, were associated with higher income.

A New Century: Reforms, But Diverse and Uneven

After two decades of stagnation, many provinces began in the early 2000s to invest in strengthening primary care. An improved fiscal climate and growing public and professional dissatisfaction underpinned the Romanow and Kirby reports, both of which highlighted the centrality of primary care for health system performance (Commission 2002; Standing Senate Committee 2002). Importantly, the federal Primary Health Care Transition Fund in 2000 and the Health Reform Fund in 2003 channelled new money into primary care reform.

Several provincial initiatives have been implemented to improve primary care. They include practice networks, interprofessional teams, patient enrolment with a provider, blended physician payment schemes and targeted financial incentives, local or regional governance, expansion of the pool of providers (both physicians and other health professionals), implementation of EMRs and quality improvement training and support.

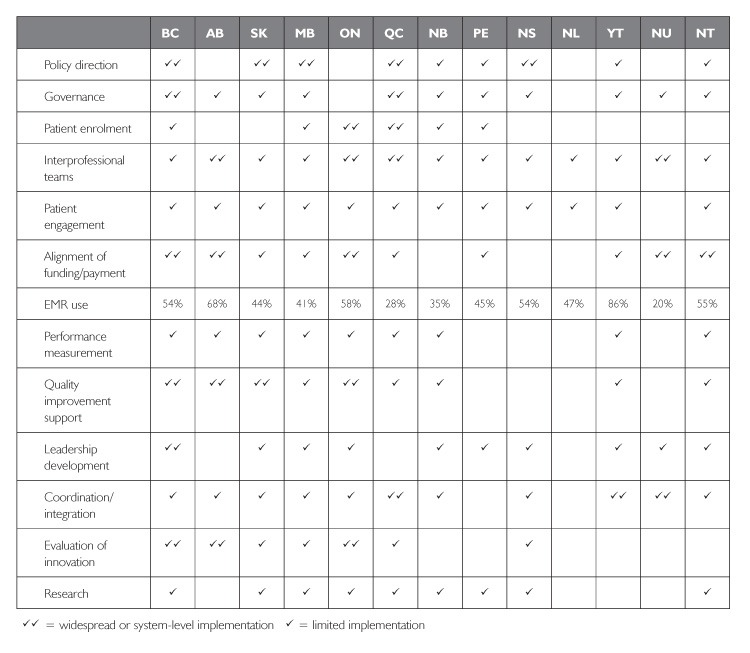

The content and pace of reform have been highly variable among the provinces, as illustrated in Figure 2 (Aggarwal and Hutchison 2012). The figure lists features of primary care systems that enable high levels of performance. Cells containing a double check mark indicate (as of a year ago) widespread or system-level implementation of these features; cells with a single check mark indicate limited implementation and empty cells indicate no implementation.

FIGURE 2.

Enablers of high-performing primary care

Most of these features have been implemented widely in one or more provinces. As William Gibson (1999) has famously said: “The future is already out there, it's just very unevenly distributed.” There are, however, three exceptions – features not broadly implemented anywhere in Canada. These are (a) patient engagement as partners both in their own care and in the design of primary care services; (b) systematic, ongoing measurement of primary care performance; and (c) appropriate investment in primary care research, research training and research application.

Are We There Yet? Still Lagging, But Signs of Progress

How these reforms have affected healthcare processes and outcomes has become a burning question for many policy makers, especially in provinces that have invested most heavily in reform. Although understandable, the question is in some respects problematic. First, it ignores the inevitability of time lag. How soon can the impacts of structural reforms be expected to manifest? Delayed effects must be expected for most reforms introduced over the last decade, especially for complex interventions such as interprofessional teams, which require a realignment of primary care culture. Second, impacts need to be measured to be observed – and no province has a performance measurement system in place that tracks change over time across an appropriate set of measures.

Nevertheless, serial administrations of the Commonwealth Fund patient and provider surveys show slow but steady improvement on some measures over the last decade (Commonwealth Fund 1998, 2000, 2001, 2004–2012). Canada remains, however, an international laggard.

Canadians' confidence in the health system has increased steadily during the 2000s. In 2010, 40% believed it was working well, and only 10% thought it needed a complete overhaul. These numbers compare well with 20% and 25% in 1998, but they still fall far short of 55% and 5% in 1988. The collapse in confidence associated with funding constraints during the 1990s has yet to be fully rebuilt. Canadians' rating of their regular source of care has risen sharply, and access to care has become more timely, even though the proportion reporting a regular source of care has fallen somewhat and emergency room use is up. Use of EMRs is increasing, but still comparatively very low.

The last decade has seen profound changes in the funding and organization of primary care in most provinces. As Figure 2 shows, however, progress has been uneven and no province has all the system elements in place to match the best-performing systems internationally. These features need to be spread widely.

The biggest improvements in performance will, I believe, come from the following: creation and support of inclusive primary care governance at the local and regional levels; interprofessional teams; patient enrolment with a provider; comprehensive performance measurement systems that can support decision-making, quality improvement and accountability at every administrative level; quality improvement training and support; and expanded use and functionality of EMRs.

Stay the Course: Primary Care Is Not Breaking the Budget

Primary care reform is unfinished business in every province – and barely begun in some. Substantial additional investments are required – and there's the rub. In Ontario, for example, many policy makers feel that “we've done primary care; we've spent a lot and have little to show for it, so let's move on to something else.” In his 2011 report, the Auditor General of Ontario drew attention to the 32% increase in provincial expenditures on primary care between 2006/7 and 2009/10 (Office of the Auditor General of Ontario 2011: 150). He did not, however, note that overall government healthcare expenditures rose by 23%. The primary care share thus rose only from 7.5% to 8.1% – hardly a massive impact on the overall budget. In 2009/10, provincial government primary care expenditures were barely equal to the combined budgets of the nine largest Toronto hospitals.

“We Can't Afford“ Medicare – New Singers, Same Old Song

The plea for continuing investment in primary care – or, indeed, any other health sector – is frequently countered by concerns about the rising share of health spending in provincial government budgets, and more generally about rising total public and private health expenditures as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP). Often the two are lumped together as a concern about medicare's alleged “unsustainability,” though the linkage is faulty and confused (or deliberately deceptive). Those who allege unsustainability are in fact arguing for an expanded role for private financing, user payment with or without private insurance.

These issues feature prominently in Jeffrey Simpson's book, Chronic Condition: Why Canada's Health Care System Needs to be Dragged into the 21st Century (Simpson 2012). Simpson worries, understandably, about healthcare “crowding out” other provincial spending such as education. His metaphors, however – healthcare “devouring budgets” and “money … shoveled into health care” – are calculated to conjure up images of massive profligacy and waste – mindless spending, even gluttony. Not only is medicare economically unsustainable, it does not deserve our support. The “glutton” imagery may be hard for patients and providers to recognize, but the core of the “unsustainability” claim lies elsewhere. The central assumption is that taxes cannot or will not – or, clearly visible between the lines, should not – rise to support increased government spending on health. If more money is needed, make the patients pay.

The Low-Tax Agenda: Social Costs, No Economic Benefit

Although not widely advertised as such, Canada is in fact a low-tax country. In 2010,3 total tax revenue amounted to 31% of GDP, below the 34% average of the 34 OECD countries and lower than 22 of them. Eight countries had tax revenues above 42% of GDP (OECD 2012).

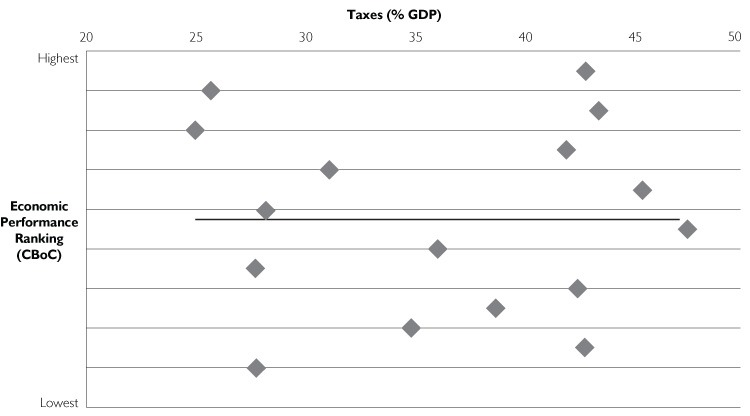

Proclamations about the necessity of maintaining low taxes as a stimulus to economic growth routinely issue from editorials, op-eds, business leaders and politicians. Yet, there is no basis for these claims. In April, the Conference Board of Canada issued a report ranking the performance of 17 high-income countries in seven categories, including economic performance and social quality of life (Conference Board of Canada 2013b). Figure 3 shows the (lack of) correlation between the Conference Board rankings of economic performance and the OECD ranking of tax revenues. Could it be that low taxes are not essential to economic success after all?4

FIGURE 3.

Economic performance ranking vs. tax revenue in 16 wealthy OECD countries

Sources: OECD 2012; Conference Board of Canada 2013b

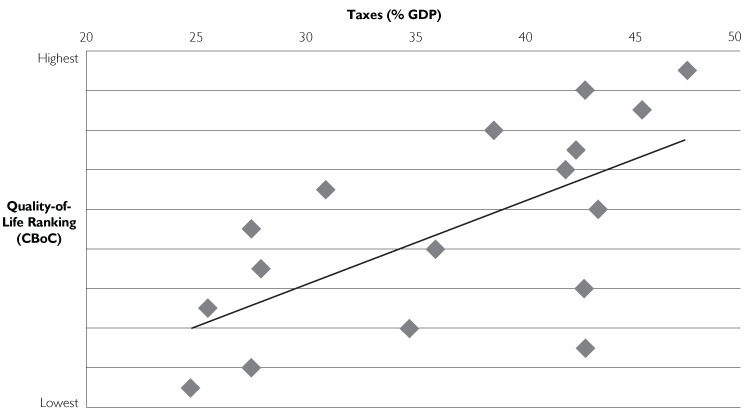

Figure 4 shows the relationship between tax revenues and rankings of social quality of life based on 16 measures.5 The correlation between the two, 0.642, is highly significant (p=0.005). It appears that low taxes may incur a large social cost without an economic benefit – the worst of both worlds. But they do benefit the already well-off.

FIGURE 4.

Quality-of-life ranking vs. tax revenue in 17 wealthy OECD countries

Sources: OECD 2012; Conference Board of Canada 2013b

Health Spending: Economic Drag or Economic Engine?

Simpson views healthcare as a drag on the economy, observing with alarm its increasing share of national income. “[T]oday it eats up 11.7% of GDP” – again, the glutton metaphor – up from 7% when medicare began. But why is that necessarily a bad thing? Medicine has changed dramatically in scale and scope over the past half century, as every patient and practitioner knows. Would Simpson have us believe that there are no commensurate benefits?

Another recent report from the Conference Board of Canada (2013a) turns the “economic drag” claim on its head, describing the health sector as “an important driver of economic growth”: “Health care spending in Canada contributed (my emphasis) 10.1 per cent of the national GDP in 2011 and supported 2.1 million jobs.”

Ironically, the main “solutions” proposed by Simpson and his ilk to the alleged unsustainability of medicare – a parallel private system of delivery and finance – would actually raise healthcare costs. Those with private insurance or deep pockets would obtain faster or better service outside the public system, while providers who served them would obtain higher fees and other payments. Private health insurance magnifies the cost inflation. The OECD, typically “private sector friendly,” reports: “Whatever [its] role …, private health insurance has added to total health expenditures …” (OECD 2004).

The OECD (2004) also points out that in some countries “private health insurance has enhanced access to care. But such access is often inequitable, largely because private health insurance is typically purchased by high-income groups … [who obtain] shorter wait times for elective surgery. But there is no clear evidence that waiting times are also reduced in the public sector … .”

Expanding private payment would have the additional perverse effect of exacerbating income inequality, the most potent social determinant of health. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI 2013) concludes, consistent with earlier Canadian and international research, that publicly financed healthcare redistributes income from richer to poorer Canadians.

To sum up, continued investments are needed to strengthen primary care as the foundation of a high-performing healthcare system. Moreover, there is room, if need be, to increase taxes to make those investments. But facts and evidence are not the main determinants of public policy. When all is said and done, the struggles over medicare are about conflicting interests and values.

Forget the Evidence! Where You Stand Depends on Where You Sit

Simpson, and presumably those he represents, calls for replacing “ideologies, inspired by vacuous slogans” with “a more functional framework of what works best at lower cost for Canadians.” Few would disagree.

But proposals to introduce a parallel system of private delivery and payment would drag Canadian healthcare not into the 21st century, but back towards the early 20th. The notion that the system would be “fixed” by measures that would increase costs, improve access only for those able to pay and shift cost burdens from taxpayers (generally wealthier) to patients (generally less so) is more than a little bizarre. That would certainly benefit some Canadians – the same narrowly based but strategically placed interest groups that opposed medicare in the first place and still do. Simpson speaks for them. But behind the obvious economic interests of the privatizers, there is also a real clash of values. When Simpson contrasts the “ideology” of medicare's supporters with the supposed pragmatism of its attackers – people like himself – he just has it wrong. The clash is between competing sets of values: libertarian on the one side and communitarian on the other. The libertarian perspective in its most extreme form is captured in Margaret Thatcher's famous statement, “There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families.” Or, as Lily Tomlin has said with tongue in cheek: “Remember, we're all in this alone.”

Libertarian values include personal responsibility, unfettered autonomy and choice, small government, low taxes, personal as opposed to public spending and unconstrained opportunities for increasing individual income and wealth.

Communitarian values include shared responsibility, equality, fairness, collective rather than individual solutions to social problems, redistribution of wealth and income, and a sense of community.

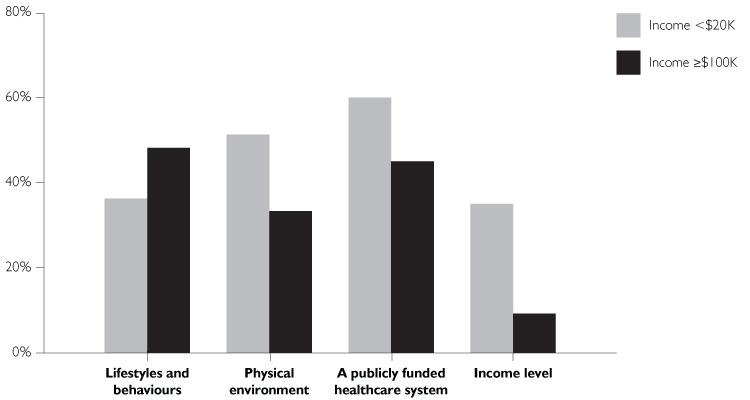

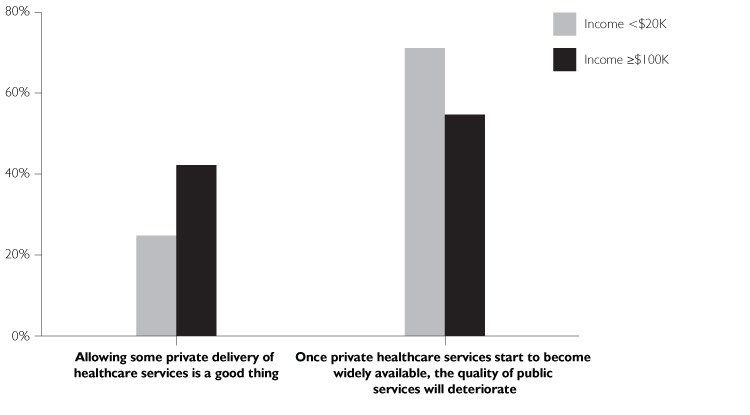

But values and beliefs are not randomly distributed in the population. As shown in Figures 5 and 6, which summarize data from a 2012 EKOS poll (Conference Board of Canada 2012), they vary systematically with income. Figure 5 shows the percentage of high- and low-income Canadians who see lifestyle, the physical environment, publicly funded healthcare and income level as “extremely important” determinants of Canadians' health. Ironically, the Canadians who benefit the most from income as a determinant of health are the least likely to recognize its importance. As seen in Figure 6, they are also most likely to support private delivery of health services and least likely to see parallel private healthcare as a threat to the public system.

FIGURE 5.

Determinants of Canadians' health (% rating as “extremely important”)

Source: Conference Board of Canada (EKOS Poll) 2012

FIGURE 6.

Private healthcare delivery

Source: Conference Board of Canada (EKOS Poll) 2012

The relationship between values and income means that the struggle to maintain, improve and expand medicare as a program that embodies the core value articulated by Douglas and Hall – healthcare access and quality based solely on need – will continue to face opposition from individuals and organizations whose economic and political influence is disproportionate to their numbers. However, the line-up today is essentially the same as it was when medicare was being debated in the 1960s. We won then, and we can win again.

This column is based on the 2013 Emmett Hall Memorial Lecture delivered on May 29, 2013 at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research. The lecture is available at http://www.hallfoundation.ca/?page_id=599 and http://www.youtube.com/CAHSPR.

Read “province[s]” to include territories.

The last year for which international comparative data are available.

Correlation is not causality, but lack of correlation isn't either.

These include income inequality; poverty among children, working age adults and the elderly; unemployment; the gender income gap; social supports; life satisfaction; and suicides, homicides and burglaries.

Footnotes

✓✓ = widespread or system-level implementation ✓ = limited implementation

Source: Aggarwal and Hutchison 2012

References

- Aggarwal M., Hutchison B. 2012. Toward a Primary Care Strategy for Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement; Retrieved July 9, 2013. English: <http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/Libraries/Reports/Primary-Care-Strategy-EN.sflb.ashx>; French: <http://www.fcass-cfhi.ca/Libraries/Reports/Primary-Care-Strategy-FR.sflb.ashx>. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). 2013. (May). Lifetime Distributional Effects of Publicly Financed Health Care in Canada. Ottawa: Author [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). 2013. (June 26). “Harper Government Supports Community-Based Primary Health Care.” Press release. Canada Newswire. Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.newswire.ca/en/story/1190729/harper-government-supports-community-based-primary-health-care>.

- Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (Romanow Commission). 2002. Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada – Final Report. Ottawa: Author [Google Scholar]

- Commission on the Reform of Ontario's Public Services (Drummond Commission). 2012. Public Services for Ontarians: A Path to Sustainability and Excellence. Toronto: Queen's Printer for Ontario [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 1998. 1998 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/1998/1998-International-Health-Policy-Survey.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2000. 2000 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Physicians. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2000/2000–International-Health-Policy-Survey-of-Physicians.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2001. 2001 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2001/2001-International-Health-Policy-Survey.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2004. 2004 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Adults' Experiences with Primary Care. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2004/2004-Commonwealth-Fund-International-Health-Policy-Survey-of-Adults-Experiences-with-Primary-Care.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2005. 2005 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Sicker Adults. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2005/2005-Commonwealth-Fund-International-Health-Policy-Survey-of-Sicker-Adults.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2006. 2006 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2006/2006-International-Health-Policy-Survey-of-Primary-Care-Physicians.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2007. 2007 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey in Seven Countries. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2007/2007-International-Health-Policy-Survey-in-Seven-Countries.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2008. 2008 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Sicker Adults. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2008/2008-Commonwealth-Fund-International-Health-Policy-Survey-of-Sicker-Adults.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2009. 2009 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2009/Nov/2009-Commonwealth-Fund-International-Health-Policy-Survey.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2010. 2010 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2010/Nov/2010-International-Survey.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2011a. 2011 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2011/Nov/2011-International-Survey.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2011b. 2011 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey data extract. Health Quality Ontario, personal communication, February 25, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund. 2012. 2012 Commonwealth Fund International Survey of Primary Care Doctors. New York: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2012/Nov/2012-International-Survey.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- Conference Board of Canada. 2012. Canadian Views on Health and the Health Care System: Results of an EKOS Survey. Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.conferenceboard.ca/documents/ekos_surveyresults_2012.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Conference Board of Canada. 2013a. (January). Health Care in Canada: An Economic Growth Engine. Ottawa: Author [Google Scholar]

- Conference Board of Canada. 2013b. (April). How Canada Performs: A Report Card on Canada. Ottawa: Author [Google Scholar]

- Davis K., Schoen C., Stremikis K. 2010. “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall. How the Performance of the US Health Care System Compares Internationally – 2010 Update.” New York: The Commonwealth Fund; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/Files/Publications/Fund%20Report/2010/Jun/1400_Davis_Mirror_Mirror_on_the_wall_2010.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas T.C. 1961. (April 13). Statement in the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson W. 1999. (November 30). “The Science in Science Fiction,” on Talk of the Nation, National Public Radio. Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1067220>.

- Horne F. (Alberta Minister of Health and Wellness). 2012. (November 18). Opening remarks to the Conference on Accelerating Primary Care, Banff, Alberta. Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://vimeo.com/54834853>.

- Kringos D.S., Boerma W., van der Zee J., Groenewegen P. 2013. “Europe's Strong Primary Care Systems are Linked to Better Population Health But Also to Higher Health Spending.” Health Affairs 32: 686–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macinko J., Starfield B., Shi L. 2003. “The Contribution of Primary Care Systems to Health Outcomes within Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Countries, 1970–1998.” Health Services Research 38(3): 831–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. 2011. 2011 Annual Report. Toronto: Queen's Printer for Ontario [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2004. “Private Health Insurance in OECD Countries: A Policy Brief.” Paris: Author; Retrieved July 9, 2013. <http://www.oecd.org/publications/Pol_brief>. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2012. Tax Policy Analysis: Revenue Statistics Tax Ratios Changes between 2007 and Provisional 2011 Data. Paris: Author; <http://www.oecd.org/ctp/tax-policy/revenuestatisticstaxratioschangesbetween2007and2011.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission on Health Services (Hall Commission). 1964. Report. Ottawa: The Queen's Printer [Google Scholar]

- Schoen C., Osborn R., Squires D., Doty M., Rasmussen P., Pierson R., et al. 2012. “A Survey of Primary Care Doctors in Ten Countries Shows Progress in Use of Health Information Technology, Less in Other Areas.” Health Affairs 31: 2805–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. 2012. Chronic Condition: Why Canada's Health Care System Needs to be Dragged into the 21st Century. Toronto: Allen Lane [Google Scholar]

- Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology (Kirby Committee). 2002. The Health of Canadians – The Federal Role. Final Report on the State of the Health Care System in Canada. Volume Six: Recommendations for Reform. Ottawa: Author [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B. 2012. “Primary Care: An Increasingly Important Contributor to Effectiveness, Equity and Efficiency of Health Services. SESPAS Report 2012.” Gaceta Sanitaria 26 (Suppl.) 1: 20–26. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B., Shi L. 2002. “Policy Relevant Determinants of Health: An International Perspective.” Health Policy 60(3): 201–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]