Abstract

Background:

Burning of biomass is widely used by the rural poor for energy generation. Long term exposure to biomass smoke is believed to affect lung function and cause respiratory symptoms.

Materials and Methods:

Women with long term occupational exposure to burning firewood were recruited from a rural fishing community in Nigeria. A questionnaire was used to obtain information on symptoms of chronic bronchitis and spirometery was performed to measure lung function. Data obtained from the subjects was compared with that from healthy controls.

Results:

Six hundred and eighty six women were recruited for this study made up of 342 subjects and 346 controls. Sixty eight (19.9%) of the subjects had chronic bronchitis compared with eight (2.3%) of the controls (χ2 = 54.0, P < 0.001). The subjects had lower values for the lung function as well as the percentage predicted values (P < 0.05). Fish smoking and chronic bronchitis were significantly associated with predicted lung volumes.

Conclusion:

Chronic exposure to biomass smoke is associated with chronic bronchitis and reduced lung functions in women engaged in fish smoking.

KEY WORDS: Biomass smoke, indoor air pollution, lung function

INTRODUCTION

Approximately, 50% of the world population and up to 90% of the population in developing countries rely on biomass fuels for everyday household energy needs.[1] Biomass is any material derived from living or recently living material that may be used as fuel to be burned in a stove. Often, the stoves being used have poor combustion capacity and can utilize only a fraction of available fuel energy.[2] The resulting incomplete combustion generates heavy smoke and release a number of harmful pollutants the most important of these include; particulate matter, carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, sulfur oxide, formaldehyde and polycyclic organic matter.[3]

The use of biomass for cooking and heating usually takes place indoors and these homes are usually poorly ventilated.[4] The low efficiency of this fuel source will require that fires have to be kept going for many hours a day thus exposing these people to years of daily smoke.[5] The pollution level in such homes have been documented by previous studies[6,7] and they may be hundreds of times above the U.S. Environmental protection agency regulations for outdoor air pollutants.[8,9] The pollution level alone does not fully determine the health related consequences of indoor air pollution. More important than the level of pollution is the level of exposure, i.e., the time people spend breathing the polluted air.[10,11] Thus, indoor air pollution from biomass fuels combustion predominantly affects poor rural and urban communities in the developing countries who are at the lowest end of the energy ladder.[12] The reliance on biomass fuel has emerged as one of the most important threats to public health. In 2000, indoor air pollution was responsible for more than 1.5 million deaths and 2.7% of the global burden of disease. In developing countries, it accounted for 3.7% of the burden of disease, making it the most important risk factor after malnutrition, the human immunodeficiency virus infection infection and lack of safe water.[13]

Exposure to indoor air pollution has been linked to a number of respiratory illnesses including acute respiratory infection,[14,15] chronic bronchitis,[16,17] asthma,[18] tuberculosis,[19,20] lung cancer,[21,22] impaired lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[23,24,25] The precise mechanism involved in the development of impaired lung function from biomass smoke exposure is still open to debate. Experimental studies in animals support the view that the high content of volatile elements from biomass combustion may account for the increased risk of respiratory diseases. Lin et al. reported that wood smoke inhalation causes airway and parenchymal injury.[26] It has also been shown that chronic exposure to wood smoke increases macrophage matrix metalloproteinase expression and activity, which might produce lung damage similar to what ensues with tobacco smoking.[27]

Nigeria has a large rural population and they rely on burning biomass for energy. A few studies in Nigeria have looked at the association of long-term exposure to indoor air pollution and respiratory functions.[11,28] Some other studies have evaluated the association between occupational exposure to biomass smoke and acute respiratory symptoms.[29,30] The present study was carried out to evaluate the association between long-term biomass smoke exposure and lung function among women who smoke fish in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

A rural fishing community; Ibaka was randomly selected for this study. It is a poor coastal fishing settlement in Mbo Local Government Area in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria with no electricity and no pipe borne water. The community has a population of 176,680 people as estimated by the 2006 national population census.[31] It is located to the South-West of Calabar on the coastal plain and it is accessible by sea and road. The major industry here is fishing and as such most of the inhabitants are engaged in fishing and the processing of the marine products.

Subjects

For this survey, 342 women who are engaged in smoking of fish were recruited. The fish smoking process is usually carried out indoors in drying huts. These huts are constructed with dried mud bricks and sticks with a thatch roof. An average drying hut will measure 7 by 4 m with a door and one or two windows. The drying area is constructed by pacing a wire mesh or sticks on four wooden supports at a height of about 1.3 m above the ground. Firewood derived from the local trees and shrubs is burnt beneath the net to produce heat and smoke while the fish and other marine products are placed on the net over the fire. Crop residues and chemicals are not added to the flames. The women usually stay close by and regularly attend to the fire [Figure 1]. The drying process usually takes a week to complete.

Figure 1.

Fish smoking in progress

There were over 2500 houses spread out in eight clusters. Each cluster contained about 300 houses. About 60 women were selected from each cluster of houses. A subject was selected from every fourth house by simple ballot and the first house was selected by the same process. For this study, 346 women were randomly selected as control subjects. The control subjects were women who were mainly engaged in fishing. They were selected from the same community, but were not involved in smoking of fish.

Domestic cooking is an activity largely reserved for women in the study area and burning of fire wood is the main source of energy for this. Domestic cooking is practiced by both test and control subjects with only a few of the women in either group using kerosene occasionally. Animals are not domesticated by these riverine folk as such they do not use dung and liquefied petroleum gas is generally too expensive for them. Therefore, we considered the use of any other form of fuel for cooking other than firewood to be insignificant in either group.

Other sources of indoor air pollution such as environmental tobacco smoke and pesticides were not recorded for the participants.

Interview

A questionnaire was designed to collect data from the subjects. It was made up of two parts: The first part consisted of questions related to demography while the second part consisted of the British Medical Research Council respiratory disease questionnaire.[32] The questionnaire was translated into the local language and back translated to ensure consistency. Chronic bronchitis was defined as productive cough on most days for 3 months in two consecutive years. The questionnaire was administered on the subjects by trained interviewers. Other chronic respiratory disorders such as asthma, tuberculosis and bronchiectasis were not inquired for in the questionnaire.

Lung function measurements

A Vitalograph spirometer model R (Vitalograph limited, Germany) was used to measure the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and the forced vital capacity (FVC). The volume accuracy of the spirometer was checked regularly after every tenth subject with a single discharge of a 2-L calibration syringe. The accuracy of the mechanical recorder time scale was checked regularly by comparing the speed against a stop watch after every tenth subject. At least three trials per subject were taken with at least three curves that meet the American Thoracic Society criteria.[33] A Mini-Wright peak flow meter was used to measure the peak expiratory flow (PEF) of the subjects. Cumulative exposure to biomass smoke among the test subjects was determined as the product of the estimated hours spent near the fire each day and the years spent drying fish (hour-years) as used in a previous studies.[17]

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from all subjects was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.0 computer software (IBM SPSS, Inc. Chicago, Illinois). Qualitative data was given as frequency distribution and cross-tabulation while quantitative data was given as mean and standard deviation. Independent t-test was used to compare means between unpaired samples while Chi-square test was used to test for strength of association between categorical variables. Lung function of all study participants was given as the volume measured and as a percentage of the predicted value. The predicted volumes were derived from a previous study of lung function of healthy women in this environment.[34] Multiple regression analysis was used to determine the ability of some variables to predict lung function. A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

General characteristics

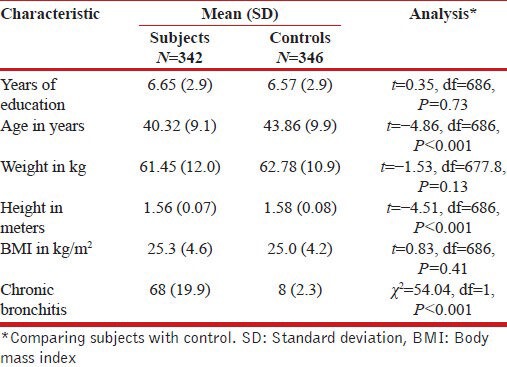

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study population. The 686 women were recruited made up of 342 women who are engaged in smoking fish (subjects) and 346 women who do not smoke fish (controls). The controls were older and taller than the subjects, but there was no difference in the years of education, weight as well as in their body mass index. None of the women in either group smoked cigarette. Sixty-eight (19.9%) of the subjects had chronic bronchitis compared with 8 (2.3%) of the controls (χ2 = 54.0, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

General characteristics of study population

Lung function parameters

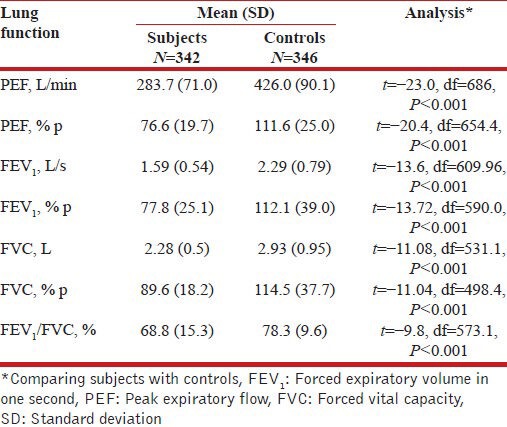

The lung function measurements of the subjects were compared [Table 2]. The subjects had lower values for all the measured parameters as well as the percentage predicted values.

Table 2.

Average lung function of study population

Correlates for lung function

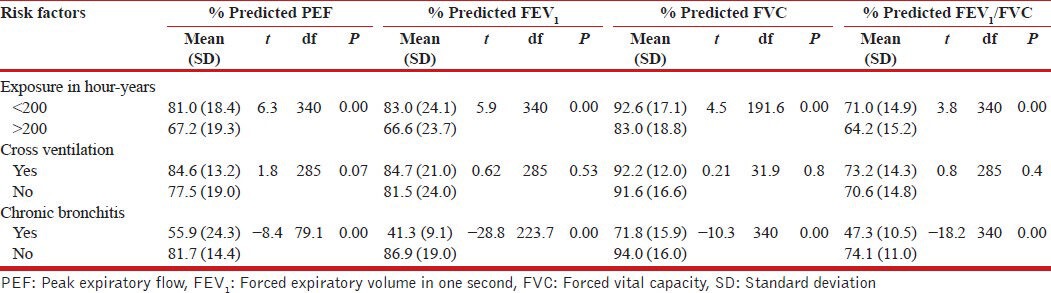

Student's t-test for independent samples was used to compare the predicted lung function parameters of the subjects [Table 3]. Women with exposure >200 h-years had lower values for lung function compared with women with exposure <200 h-years. The presence of cross ventilation did not significantly affect lung function and women with chronic bronchitis had lower predicted lung function compared with subjects without chronic bronchitis.

Table 3.

Comparison of average lung volumes of subjects based on some risk factors for pulmonary dysfunction

Predictors of lung function

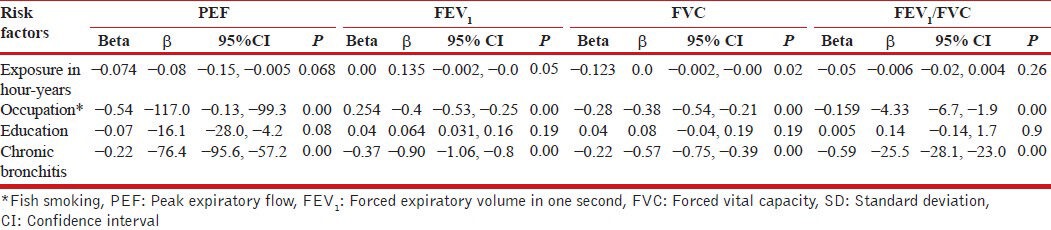

Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the ability of some variables; smoking of fish, chronic bronchitis, level of exposure in hour-years and years of education to determine the predicted lung volumes after controlling for the effects of age, weight and height [Table 4]. Fish smoking and chronic bronchitis made significant unique contributions to all the percentage predicted lung volumes. Years of education were only significant in PEF measurements. While the level of exposure made a significant contribution to FEV1 and FVC. Fish drying had the highest beta values for percentage predicted PEF and FVC while chronic bronchitis had the highest beta values for percentage predicted FEV1 and FEV1 /FVC ratio.

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regression analysis to evaluate the ability of occupation, level of exposure and education to predict lung function after controlling for the effects of age, weight and height

DISCUSSION

Our study documents lower lung function among women who engage in fish smoking and thus are exposed to high-levels of firewood smoke compared with women who do not smoke fish. This association persists after controlling for the effects of the level of exposure, education and chronic bronchitis. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that examined the relationship between biomass smoke exposure and lung function. Desalu et al. in a study to evaluate the effects of biomass smoke on lung function among women in South-West Nigeria demonstrated a reduction in lung function among women who predominantly used biomass fuels for cooking.[28] Kurmi et al. in a community survey in Nepal to assess the effects of biomass smoke exposure and lung function, compared lung function of rural dwellers who predominantly use biomass fuel for energy generation with that of semi urban dwellers who predominantly use liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) for cooking. In that study, the authors documented a significant reduction in FEV1, FVC, FEV1 /FVC ratio and forced expiratory flow 25-75 among subjects who utilize biomass fuels compared to those who utilize LPG.[35] Other investigators have documented similar findings.[36,37,38]

Reduction in lung function has not been consistently documented by all investigators. Rinne et al. in a study to determine the effects of different cooking fuels on the lung function of women and children in Santa Ana in Ecuador observed that children in homes where cooking was done predominantly with biomass fuels reported significantly lower FEV1 and FVC values when compared with other fuel types. However, there was no difference in lung function among the different fuel types among the women. This unexpected observation was attributed by the authors to the recent conversion from biomass fuels to more modern fuels by those women who utilized kerosene and LPG.[39]

Poor ventilation of the cooking area is known to concentrate pollutants thus aggravating the adverse effects of biomass smoke on lung function.[3] A previous study by Reddy et al. found that cooking with biomass was not associated with excess lung function decline if there was improved ventilation of the kitchen.[40] This observation stands in contrast to our study findings where the presence of cross ventilation was not associated with better lung function. This may be explained by the fact that fish drying generates much more smoke than domestic cooking and that during the long rainy season (about 8 months each year) the windows are usually closed thus eliminating the improved air quality that may be derived from cross ventilation.

Our study documented a significant association between chronic bronchitis and impaired lung function. This association persists after controlling for the level of exposure, occupational and the level of education. Previous studies have documented similar results; Díaz et al. in a study to determine the effects of biomass smoke on lung function and symptoms reported that women with chronic cough and phlegm, i.e., chronic bronchitis had lower FEV1 and FVC values after controlling for age, height and occupation.[41]

There are several limitations of this study. First of all, we did not document exposure to biomass smoke from cooking. We expected that as women in a rural African community, biomass smoke exposure from domestic cooking will not be selective and will therefore not introduce bias. Secondly, we did not measure directly the level of air pollution resulting from burning firewood. This would have given us the pollution levels at a particular point in time, but because the outcome of interest is as a result of long-term exposure we were of the opinion that the cumulative exposure represented by the product of the estimated average number of hours spent smoking fish and the duration in years of smoking fish (hour-years) was more appropriate for this. Finally, the study design was unable to elucidate the impact of poverty on respiratory symptoms and lung function of our subject.

CONCLUSIONS

Long-term occupational exposure to biomass smoke causes much morbidity and it has important socio-economic implications. Our study has demonstrated an increase in chronic bronchitis and a reduction in lung function as important consequences of exposure to biomass smoke. Impaired lung function is significantly associated with chronic bronchitis and level of exposure but not with ventilation of the room.

Recently, there has been increased interest in reducing indoor air pollution by providing more efficient stoves with lower potential for air pollution. The use of an improved biomass stove has been associated with a reduction in several adverse health outcomes, such as respiratory symptoms, sore eyes and headache among women in Guatemala, even after a brief follow-up.[42] In Mexico, a reduced decline in FEV1 among improved stove users of 31 ml compared with 62 ml among open fire users was observed after 1 year of follow-up.[43]

The use of biomass fuels in our environment is likely to remain stable or even increase in the near future as few rural women can afford cleaner fuels.[44] Interventional studies to evaluate the utility of improved drying stoves, capable of producing less smoke and requiring reduced attention, and improved design of the drying huts for facilitating better ventilation shall need to be undertaken in near future.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.WRI; 2000. [Accessed on 2012 Nov 02]. United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Environment Programme, World Bank, World Resources Institute. World Resources 2000-2001: People and ecosystems: The fraying web of life. Available from: http://www.wri.org/publication/world-resources-2000-2001-people-and-ecosystems-fraying-web-life . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith KR. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: Recommendations for research. Indoor Air. 2002;12:198–207. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2002.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: A major environmental and public health challenge. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1078–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezzati M, Kammen DM. The health impacts of exposure to indoor air pollution from solid fuels in developing countries: Knowledge, gaps, and data needs. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1057–68. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manuel J. The quest for fire: Hazards of a daily struggle. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:A28–33. doi: 10.1289/ehp.111-a28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehfuess E, Mehta S, Prüss-Ustün A. Assessing household solid fuel use: Multiple implications for the millennium development goals. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:373–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith KR, Uma R, Kishore VV, Zhang J, Joshi V, Khalil MA. Greenhouse implications of household stoves: An analysis for India. Annu Rev Energy Environ. 2000;25:741–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards R, Smith KR, Zhang J, Ma Y. Implications of changes in household stoves and fuel use in China. Energy Policy. 2004;32:395–411. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Accessed on 2011 Sep 22]. WHO. Global Indoor Air Pollution Database. Available from: http://www.who.int/indoorair/health_impacts/databases_iap . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J. Carbon monoxide from cook stoves in developing countries: 2 potential chronic exposures. Chemosphere Glob Chang Sci. 1999;1:367–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oguntoke O, Opeolu BO, Babatunde N. Indoor air pollution and health risks among rural dwellers in Odeda Area South-Western Nigeria. Ethiop J Environ Stud Manage. 2010;3:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta S, Shahpar C. The health benefits of interventions to reduce indoor air pollution from solid fuel use: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Energy Sustain Dev. 2004;8:53–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Accessed on 2009 Jan 19]. WHO. Death and DALY estimates for 2002 by cause for WHO member states. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/bod/en/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ezzati M, Kammen DM. Quantifying the effects of exposure to indoor air pollution from biomass combustion on acute respiratory infections in developing countries. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:481–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra V. Indoor air pollution from biomass combustion and acute respiratory illness in preschool age children in Zimbabwe. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:847–53. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekici A, Ekici M, Kurtipek E, Akin A, Arslan M, Kara T, et al. Obstructive airway diseases in women exposed to biomass smoke. Environ Res. 2005;99:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regalado J, Pérez-Padilla R, Sansores R, Páramo Ramirez JI, Brauer M, Paré P, et al. The effect of biomass burning on respiratory symptoms and lung function in rural Mexican women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:901–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-479OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra V. Effect of indoor air pollution from biomass combustion on prevalence of asthma in the elderly. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:71–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez-Padilla R, Pérez-Guzmán C, Báez-Saldaña R, Torres-Cruz A. Cooking with biomass stoves and tuberculosis: A case control study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:441–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin HH, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution and tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behera D, Balamugesh T. Indoor air pollution as a risk factor for lung cancer in women. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:190–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y, Wang S, Aunan K, Seip HM, Hao J. Air pollution and lung cancer risks in China – A meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2006;366:500–13. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erhabor GE, Kolawole OA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A ten-year review of clinical features in O.A.U.T.H.C., Ile-Ife. Niger J Med. 2002;11:101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ezzati M. Indoor air pollution and health in developing countries. Lancet. 2005;366:104–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66845-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orozco-Levi M, Garcia-Aymerich J, Villar J, Ramírez-Sarmiento A, Antó JM, Gea J. Wood smoke exposure and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:542–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00052705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin YS, Ho CY, Tang GJ, Kou YR. Alleviation of wood smoke-induced lung injury by tachykinin receptor antagonist and hydroxyl radical scavenger in guinea pigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;425:141–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montaño M, Beccerril C, Ruiz V, Ramos C, Sansores RH, González-Avila G. Matrix metalloproteinases activity in COPD associated with wood smoke. Chest. 2004;125:466–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desalu OO, Adekoya AO, Ampitan BA. Increased risk of respiratory symptoms and chronic bronchitis in women using biomass fuels in Nigeria. J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36:441–6. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132010000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akani AB, Dienye PO, Okokon IB. Respiratory symptoms amongst females in a fishing settlement in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2011. p. 3. Available from: http://www.phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/152/203 .

- 30.Peters EJ, Esin RA, Immananagha KK, Siziya S, Osim EE. Lung function status of some Nigerian men and women chronically exposed to fish drying using burning firewood. Cent Afr J Med. 1999;45:119–24. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v45i5.8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Population Commission. Nigeria demographic and health survey 2008. [Accessed on 2011 Nov 28]. Available from: http://www.pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADQ923.pdf .

- 32.British Medical Research Council (BMRC). Standardized questionnaire on respiratory symptoms. Br Med J. 1960;2:1665. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nku CO, Peters EJ, Eshiet AI, Bisong SA, Osim EE. Prediction formulae for lung function parameters in females of South Eastern Nigeria. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2006;21:43–7. doi: 10.4314/njps.v21i1-2.53955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurmi OP, Devereux GS, Smith WC, Semple S, Steiner MF, Simkhada P, et al. Reduced lung function due to biomass smoke exposure in young adults in rural Nepal. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:25–30. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00220511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.da Silva LF, Saldiva SR, Saldiva PH, Dolhnikoff M. Bandeira Científica Project. Impaired lung function in individuals chronically exposed to biomass combustion. Environ Res. 2012;112:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sümer H, Turaçlar UT, Onarlioğlu T, Ozdemir L, Zwahlen M. The association of biomass fuel combustion on pulmonary function tests in the adult population of Mid-Anatolia. Soz Praventivmed. 2004;49:247–53. doi: 10.1007/s00038-004-3038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith-Sivertsen T, Díaz E, Pope D, Lie RT, Díaz A, McCracken J, et al. Effect of reducing indoor air pollution on women's respiratory symptoms and lung function: The RESPIRE randomized trial, Guatemala. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:211–20. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rinne ST, Rodas EJ, Bender BS, Rinne ML, Simpson JM, Galer-Unti R, et al. Relationship of pulmonary function among women and children to indoor air pollution from biomass use in rural Ecuador. Respir Med. 2006;100:1208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy TS, Guleria R, Sinha S, Sharma SK, Pande JN. Domestic cooking fuel and lung functions in healthy non-smoking women. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2004;46:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Díaz E, Bruce N, Pope D, Lie RT, Díaz A, Arana B, et al. Lung function and symptoms among indigenous Mayan women exposed to high levels of indoor air pollution. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1372–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Díaz E, Smith-Sivertsen T, Pope D, Lie RT, Díaz A, McCracken J, et al. Eye discomfort, headache and back pain among Mayan Guatemalan women taking part in a randomised stove intervention trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:74–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.043133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romieu I, Riojas-Rodríguez H, Marrón-Mares AT, Schilmann A, Perez-Padilla R, Masera O. Improved biomass stove intervention in rural Mexico: Impact on the respiratory health of women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:649–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1556OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez-Padilla R, Schilmann A, Riojas-Rodriguez H. Respiratory health effects of indoor air pollution. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:1079–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]